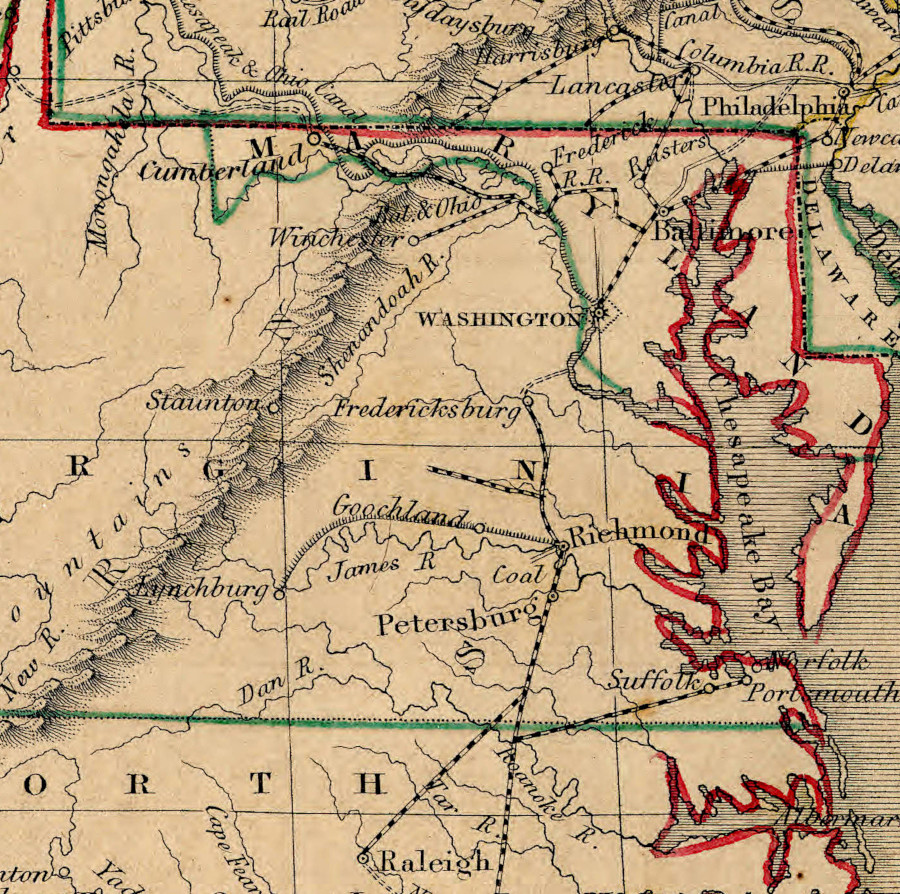

in 1842, only a handful of Virginia cities had a railroad

Source: University of North Carolina, United States, exhibiting the railroad & canals (by Thomas G. Bradford, c.1842)

in 1842, only a handful of Virginia cities had a railroad

Source: University of North Carolina, United States, exhibiting the railroad & canals (by Thomas G. Bradford, c.1842)

Starting with the Chesterfield Railroad in 1828, the Virginia General Assembly has chartered multiple railroads. However, Virginia's first railroad was built without a charter.

In 1810 or 1811, Falling Creek Railroad was built in Chesterfield County. It connected a mill producing gunpowder on Falling Creek with the magazine where the product was stored, a mile away.

The Falling Creek Railroad used wood, not iron, for the pair of rails and for the wheels of the single cart used to transport gunpowder. There was no locomotive. The loaded cart relied upon gravity to move down the track to the dock. A manually-operated lever served as the brake to manage the speed and keep the cart from jumping the track. The empty cart was pulled back up the track using a rope attached to the cart.

No charter was issued by the General Assembly for the Falling Creek Railroad. It was part of the Brown, Page and Burr gunpowder mill operation. It was not a "common carrier" willing to haul material for other corporations or individuals.1

The second railroad to be chartered by the state legislature was the Petersburg and Potomac Railroad. It was authorized in 1830 to build track connecting the Appomattox and Roanoke Rivers. That railroad was designed to compete with water transport, and to draw business to the port at Petersburg which otherwise would go to Portsmouth or Norfolk. The business and political leaders in Hampton Roads sought to block the charter, in one of the first of many bitter rivalries between towns that saw new, cheaper rail transportation as a threat to existing business patterns.

The General Assembly chartered two railroads for the Shenandoah Valley in 1831. The Staunton and Potomac Railroad planned to build from Staunton to connect to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The Winchester and Potomac Railroad had similar plans, though with Winchester as the southern endpoint of the railroad.

Representatives in the Kanawha Valley sought to amend the charter to authorize building west all the way to the Ohio River. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had not fixed its route west of Harpers Ferry. There was the potential for the mainline to go south from the Potomac River through the Shenandoah Valley and west from Staunton.

If built, much of Virginia's agricultural trade would be diverted to Baltimore. Expanding the charter rights in 1831 for the Staunton and Potomac Railroad would eliminate the restriction in the 1827 charter for the Winchester and Potomac Railroad, which restricted the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to just northwestern Virginia. The General Assembly also declared all the rights in the charter would be voided if the Staunton and Potomac Railroad received Federal aid, and refused to increase funding for internal improvements that might be used by the Staunton and Potomac Railroad.

With such constraints, the Staunton and Potomac Railroad was not a viable proposition. Only the Winchester and Potomac Railroad was able to sell enough stock to go into business.

In 1837, the state legislature adopted standard provisions for railroad charters. They included appointing commissioners to collect subscriptions for sale of stock priced at $100/share, election of a president and five directors by stockholders, and submission of an annual report to the Board of Public Works.2

Construction of the initial framework of railroads in the state was completed as a series of public-private partnerships. Nearly all railroads chartered prior to the Civil War were partially financed by the state; the Bureau of Public Works purchased 40%-60% of the railroad's bonds.

The capital-intensive railroads depended upon investors to make loans or purchase bonds. The initial capital was used to construct the first tracks, and new capital was often required for upgrading infrastructure and equipment. Reorganizations were common as railroads went through bankruptcy after failing to repay debt, or as railroads merged and/or acquired other companies in order to expand their network.

A change in a railroad's name to a "railway" indicates a revision in ownership and corporate structure. For example, the Norfolk and Western Railroad, formed in 1881, became the Norfolk and Western Railway when reorganized in 1896 in order to emerge from bankruptcy.3

The Blue Ridge Railroad was the one project funded 100% by the state, because no private company could afford the risks of constructing the first set of tunnels between Mechums River and the South Fork of the Shenandoah River through Virginia's Blue Ridge. The four tunnels were completed and operations began in 1858. The Virginia Central leased the track and, after the Civil War, acquired the company outright.

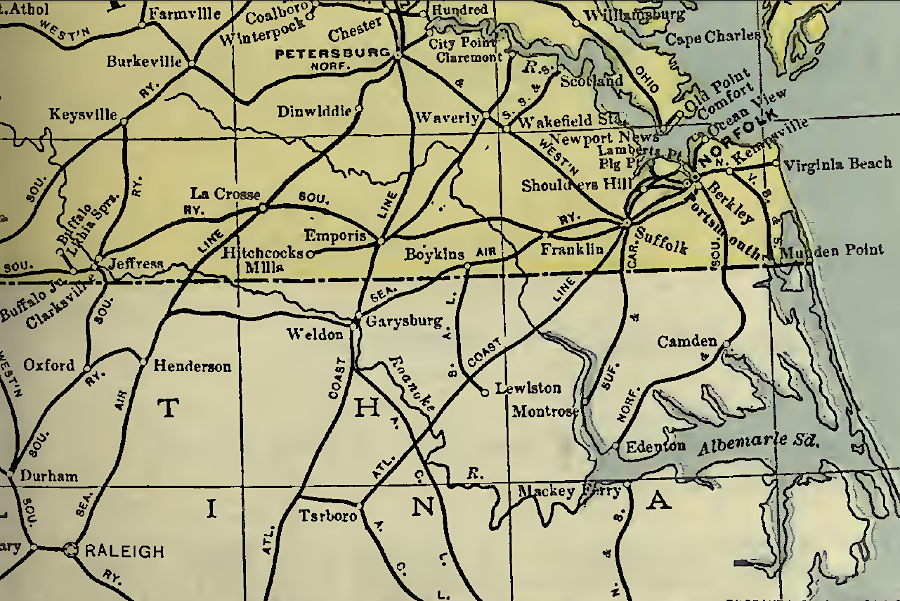

By 1858, before the Civil War, North Carolina managed to build a railroad network that connected all sections of the state east of the Blue Ridge to the port cities of Wilmington and Beaufort. Key interconnections were at Goldsboro on the Neuse River and Weldon on the Roanoke River, at the head of navigation similar to Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River.4

Virginia failed to link the northern part of the state to ports at Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg, Portsmouth, and Norfolk until the completion of the Fredericksburg-Alexandria link in 1872. Sectional rivalry between Alexandria and Richmond was an effective barrier to building an efficient transportation system.

During the Civil War, the Union Army seized railroad lines and equipment for military advantage. All or part of some lines were rehabilitated and used by the US Military Rail Road to support Union armies. The seized railroads were returned to their owners between 1864-66.5

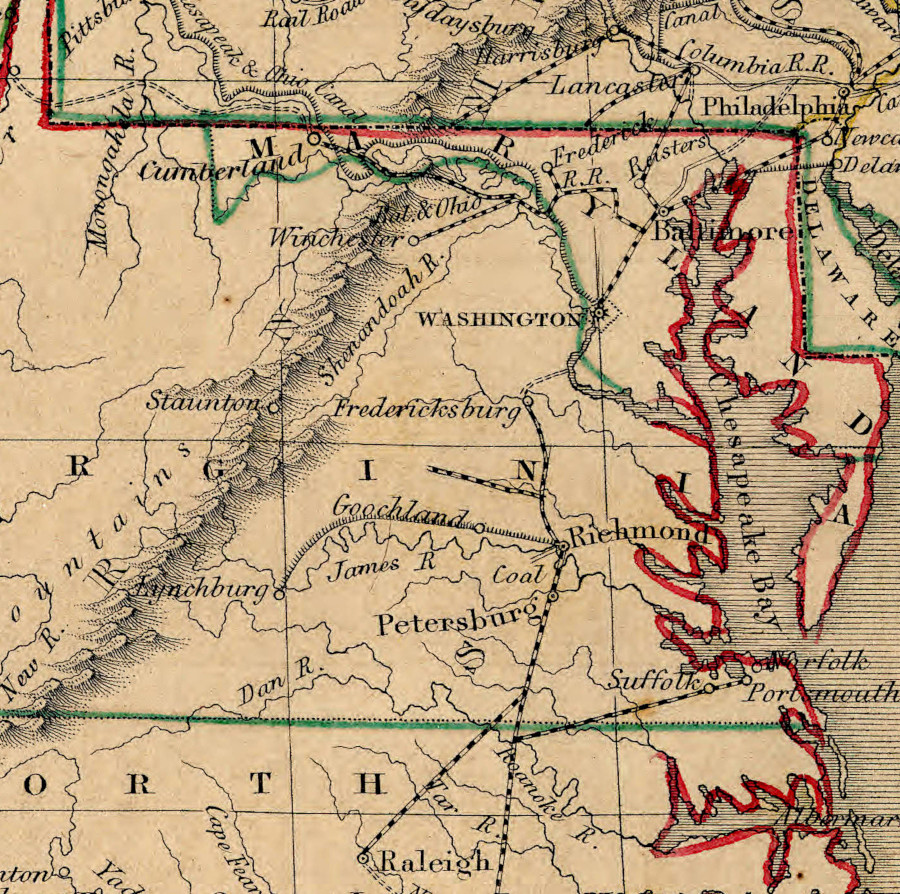

the Union Army seized Virginia railroads for military purposes in the Civil War, and returned the last one to its private owners in January 1866

Source: Library of Congress, Report of the Select Committee on Southern Railroads (February 7, 1868)

After the Civil War, northern investors took control of Virginia's railroads and focused on making them profitable. Once local investors lost control, construction of track that might carry cargo/passengers to a rival port city became more of a business decision made by Northern investors and less of a political decision made by Virginia residents.

after the Civil War, financing to restore the railroad system in Virginia came from Northern capitalists who linked competing lines together into interstate systems

Source: National Archives, Ruins of P.R.R.R. Bridge at Richmond, Virginia

The routing of railroads had an enormous impact on the development of communities. After the Norfolk and Western Railroad united two lines at Big Lick in Roanoke County, the junction became known as "Magic City" as it grew rapidly into the city of Roanoke. When the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad built its track through the swamps between Petersburg and Suffolk, small towns developed at the spots where locomotives took on water and firewood for the boilers. The Atlantic and Danville spurred the growth of Lawrenceville when it located its shops there in 1890.

Some modern railroads still follow the original routes, while other stretches of track have been abandoned. Right-of-way ownership reverted to the adjacent property owners, was used for a road, or in some cases was repurposed to become a hiking/biking trail.

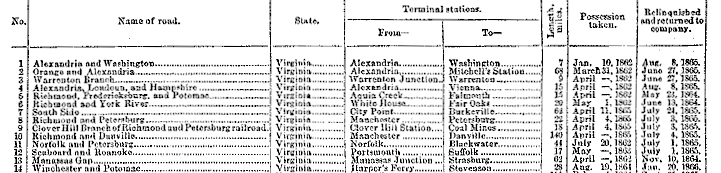

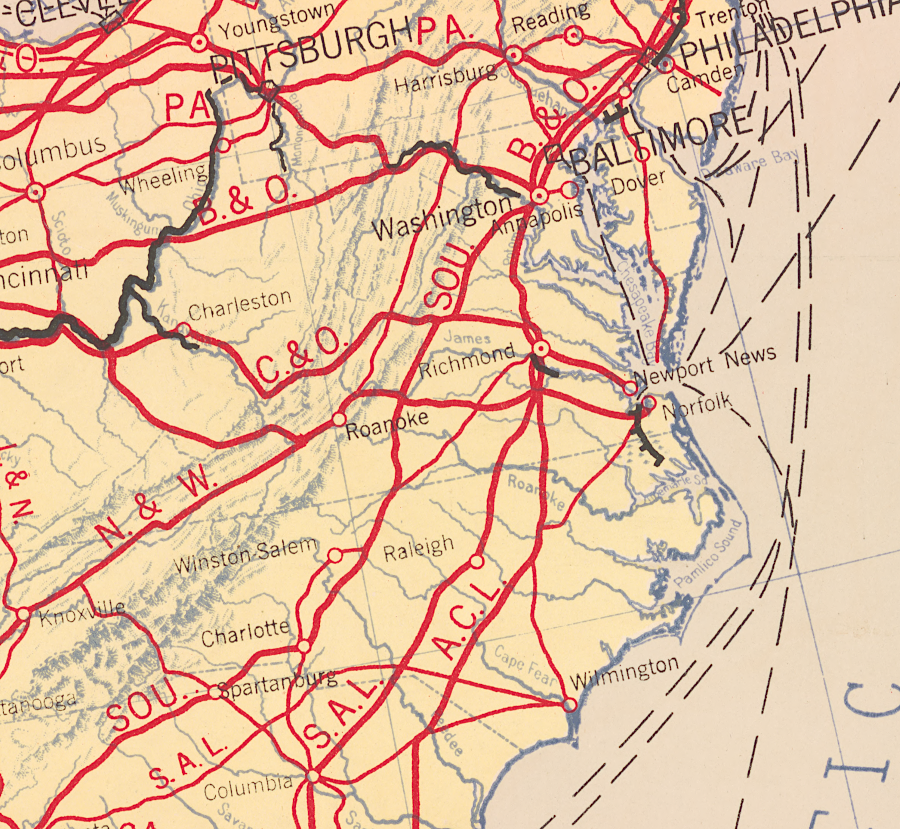

in 1901, the Seaboard Air Line and Atlantic Coast Line competed with the Norfolk and Western Railroad for the Hampton Roads traffic going inland beyond the Fall Line

Source: Poors Manual of Railroads 1901, Railroad Map of the United States - Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia (after p.128)

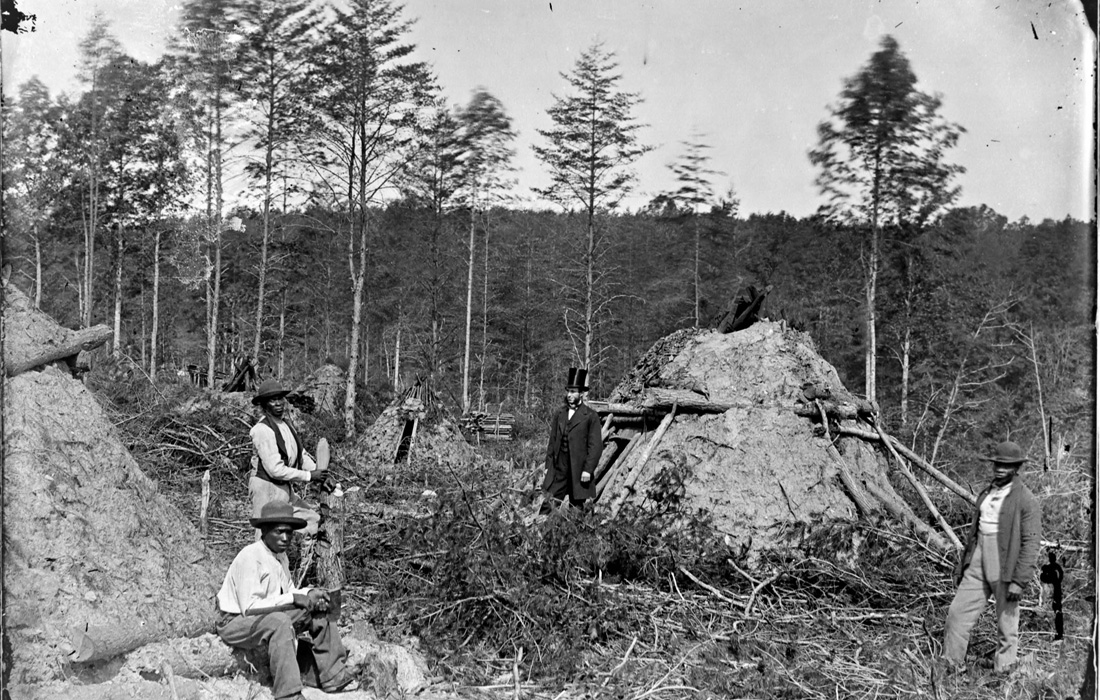

Locomotives in Virginia were fueled by wood until coal was adopted after the Civil War. A train might leave the station with a full load of wood in the tender, but need to be resupplied during the trip. Landowners would cut and stack firewood alongside the tracks, and locomotives would stop and the crew load more wood as needed. Railroads would contract with landowners for firewood to be supplied that met a specific standard, such as the length of the logs in the stack.

woodcutters lived in primitive huts along the railroad tracks, far less comfortable than the houses of the landowners who contracted with the railroads to supply fuel

Source: University of Nebraska, African American wood choppers' hut on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad

The technological change in the 1950's from steam engines fueled by coal to diesel locomotives led to a dramatic drop in railroad employment. Steam engines required a crew in each locomotive, but multiple diesel engines pulling rail cars could operate with just one crew in the lead emgine. Railroads were eventually able to eliminate the fireman from the three-person crew in the locomotives and replace cabooses with end-of-train devices, reducing the total number of people on a train to just the engineer and conductor.

Adoption of Precision Scheduled Railroading after 2015 led to another reduction in labor. Railroads operated with greater efficiency, creating trains 25% longer since 2008 to haul more cars. Using radio-controlled distributed power (DP) locomotives provided addition power without additional workers on the longer trains. Schedules were restructured to minimize the number of times trains had to stop, allowing one crew in a locomotive to go greater distances.6

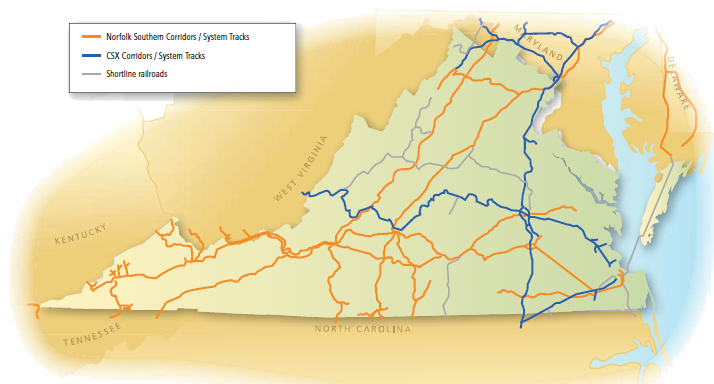

Today just two major (Class I) lines, CSX and Norfolk Southern, own most of the track in Virginia today and they focus on carrying freight. Operating freight rail systems today, including Class III "short lines," are:

railroad network in Virginia in 1878, highlighting the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road with its branches and connections (1878)

Privately-owned railroads in Virginia stopped offering passenger service in 1979, when the Southern Railway transferred its the Southern Crescent operation to Amtrak. Since then, tourist trips have been offered by the Virginia Museum of Transportation using the Norfolk & Western Class J No. 611 steam passenger locomotive. In 2023, the steam locomotive operated over the tracks of the Buckingham Branch Railroad, which were also used by the Virginia Scenic Railway. The Virginia Scenic Railway scheduled those trips, and offered the only scheduled sightseeing railroad excursion service in Virginia.7

Amtrak and Virginia Railway Express lease the right to carry passengers over tracks owned by other railroads. In addition, Metrorail in Northern Virginia and The Tide in Hampton Roads are transit rail systems that control their own track. None of the many rail-based trolley systems that once operated in Virginia have survived.

Operating passenger rail systems today include:

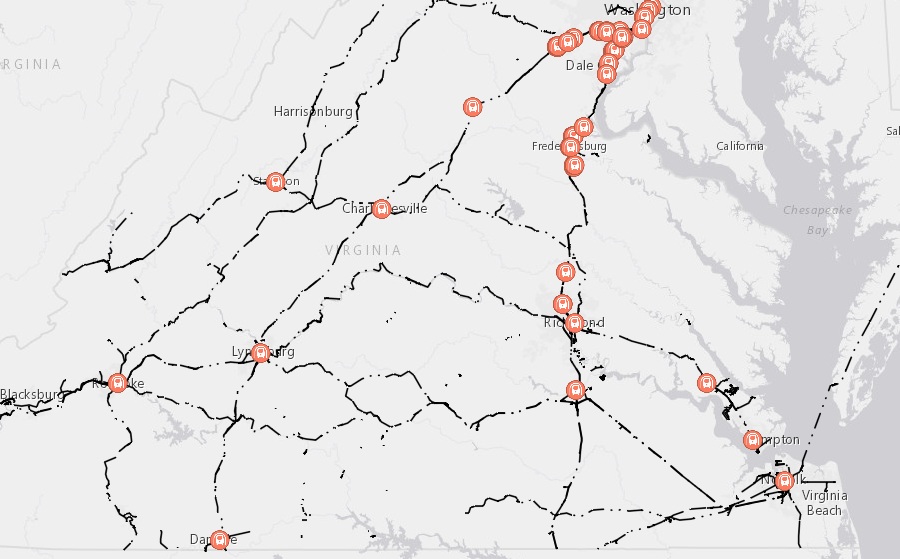

in 2019, there were no passenger rail stations west of Roanoke

Source: Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, InteractVTrans

As railroads went through financial stress and reorganized, they often changed their name from "railroad" to "railway" or vice-versa. Former railroads no longer operating, with reporting marks assigned by the Association of American Railroads that are no longer in active use, are termed "fallen flag" lines.8

locomotive of Conrail, a fallen flag railroad, at Manassas train station

Virginia railroads that are now shut down or incorporated into the remaining operating lines include:

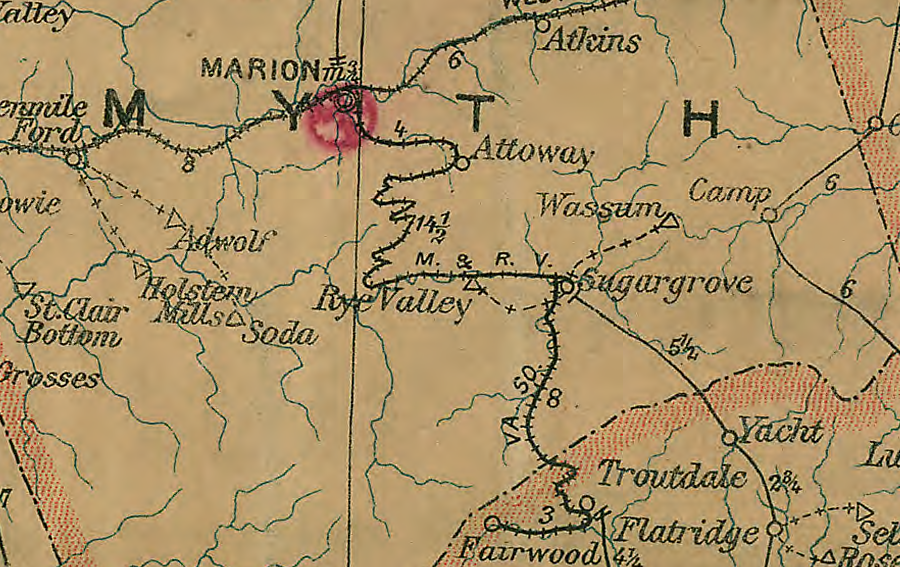

there are almost no signs today of the Marion and Rye Valley or the "Virginia Southern" logging railroads, with their junction at Sugar Grove in Smyth County

Source: National Archives, Post route map of the states of Virginia and West Virginia

Norfolk Southern and CSX are the only Class 1 railroads that remain in Virginia

Source: 2008 Virginia State Rail Plan

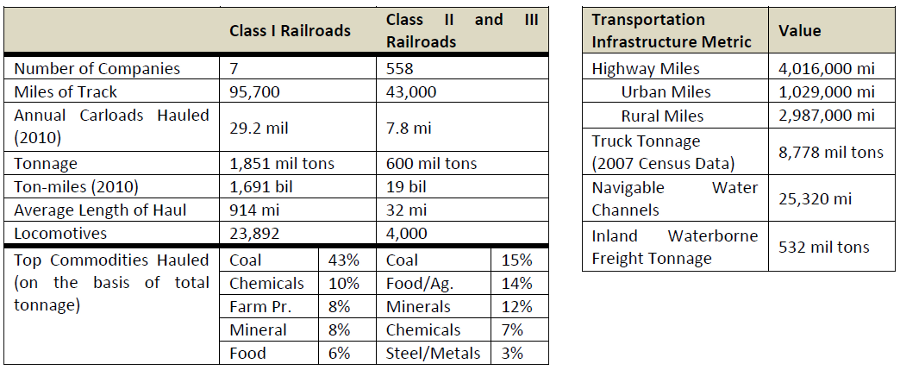

U.S. Transportation Infrastructure and Tonnage Hauled, 2010

Source: United Soybean Board, Maintaining A Track Record Of Success: Expanding Rail Infrastructure To Accommodate Growth In Agriculture And Other Sectors (Table 1)

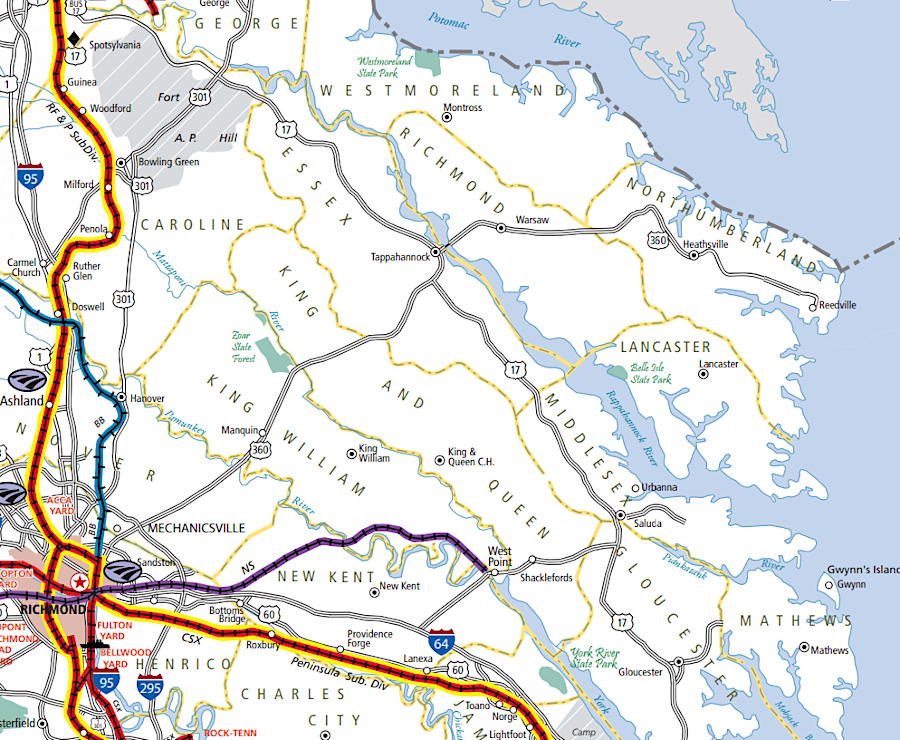

railroads were not built in the Coastal Plain north of the port of West Point

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Virginia Rail Map (2019)

Virginia railroads bought their rails and most of their locomotives from manufacturers in northern states or Great Britain

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia. Locomotive on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad (Timothy H. O'Sullivan, 1862)

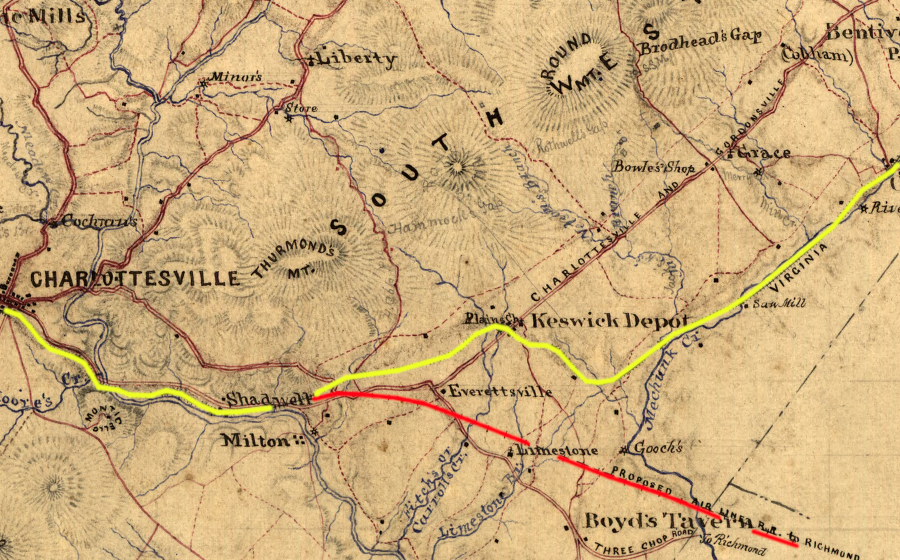

a Richmond-Charlottesville railroad (red), like many other proposals, was never built

Source: Library of Congress, Albemarle County, Virginia (by Jedediah Hotchkiss, 1867)

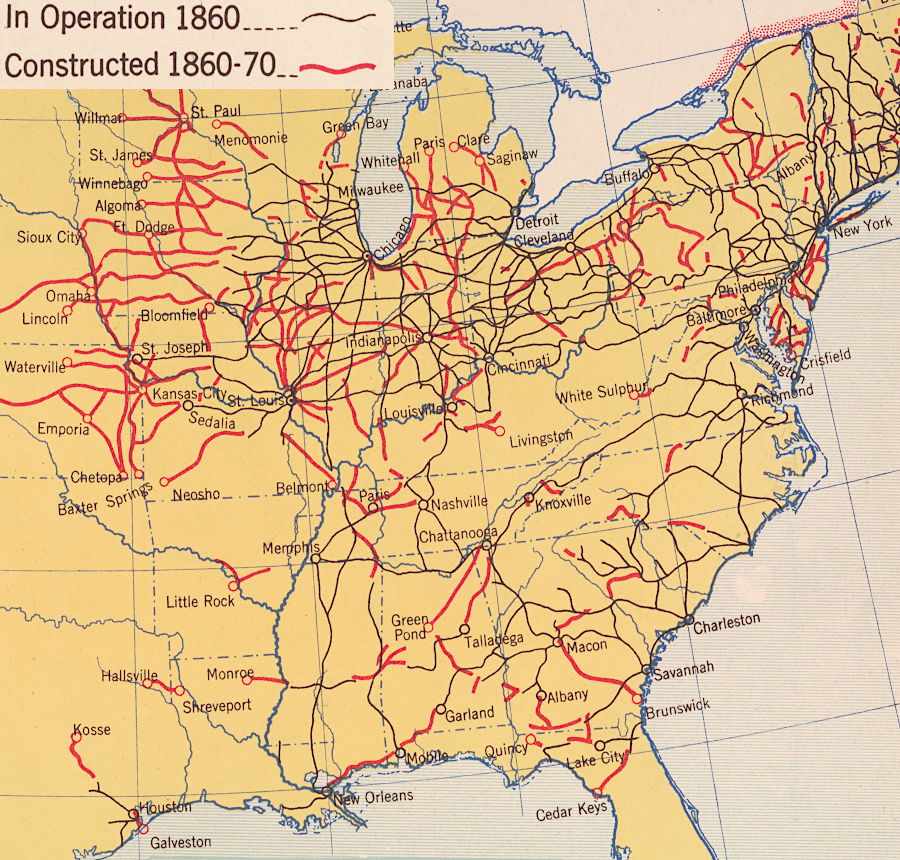

in 1870, the railroad network in Virginia connected to few destinations outside the state

Source: Library of Congress, Transportation at various periods (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1919)

in 1918, the Seaboard Air Line (SAL) and Atlantic Coast Line (ACL) railroads were competing for traffic in southeastern Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Lines of transportation, 1918 (Hart-Bolton American history maps, 1919)

major rail lines in Virginia, 2013

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map