Chesterfield Railroad

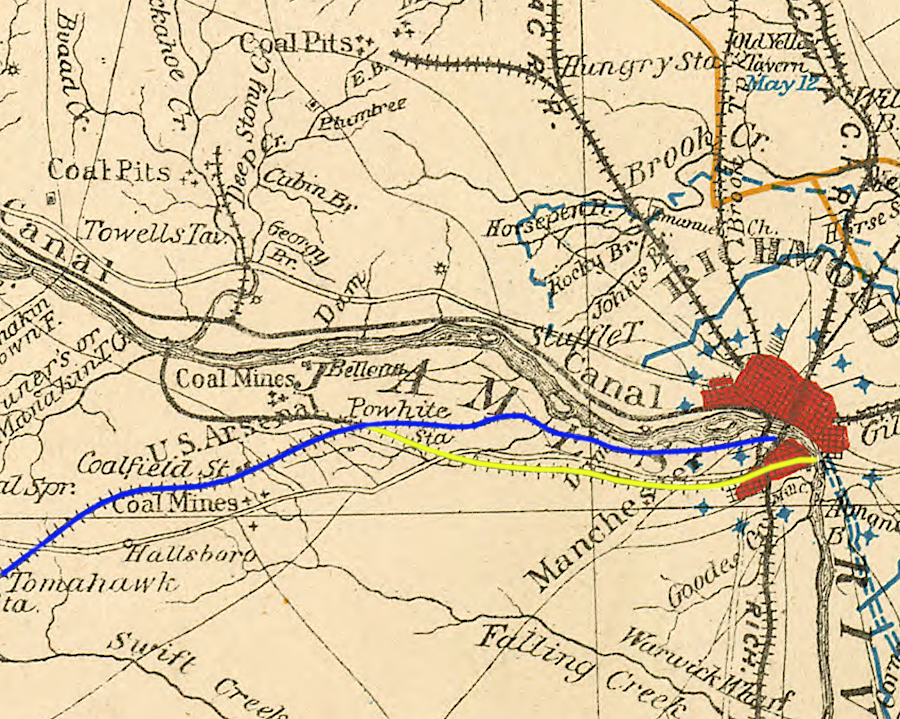

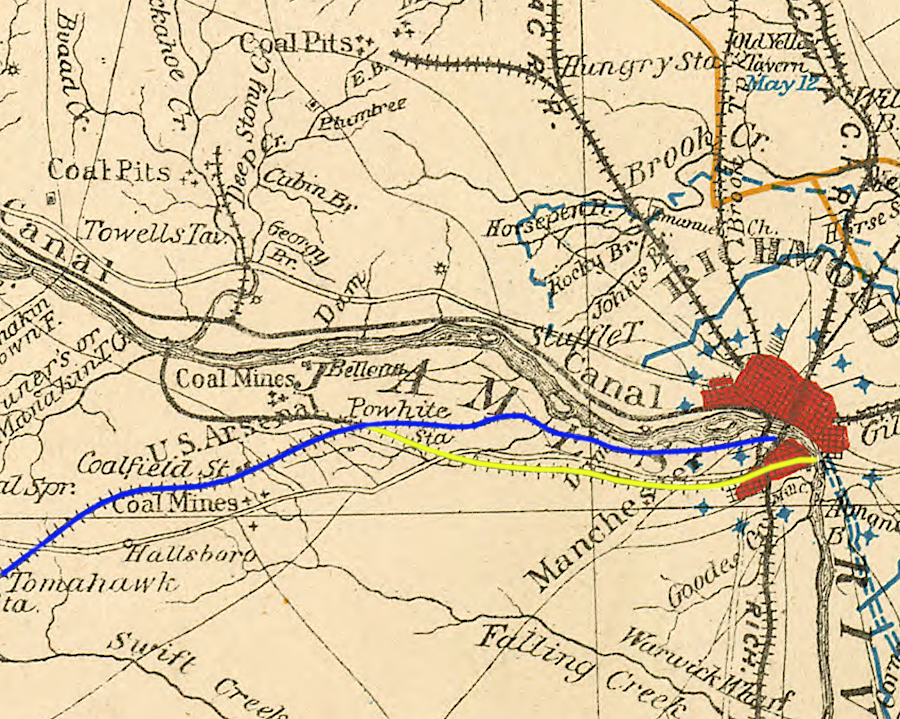

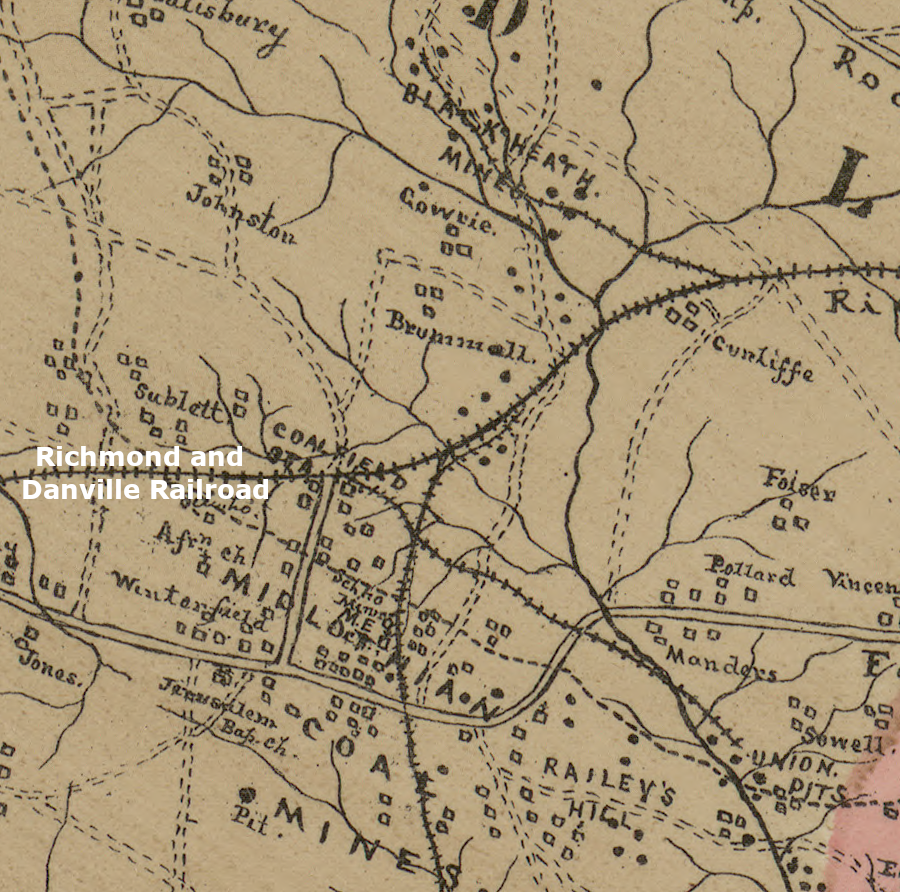

the Richmond and Danville Railroad (blue) reached Coalfield Station (now Midlothian) in 1850, and put the Chesterfield Railroad (yellow) out of business

Source: Library of Congress, Central Virginia: showing Lieut. Gen'l. U.S. Grant's campaign and marches of the armies under his command in 1864-5 (US War Department. Engineer Bureau, between 1864 and 1869)

The Chesterfield Railroad was the second to be built in Chesterfield County. The Falling Creek Railroad had begun hauling gunpowder for one mile in 1810 or 1811. Though the Falling Creek Railroad was the first railroad in Virginia, it was built without a charter.

The Chesterfield Railroad was the first chartered railroad in Virginia. The General Assembly authorized the Chesterfield Railroad in 1828, and construction was completed in 1831. Like the Falling Creek Railroad, the Chesterfield Railroad also operated without using a locomotive.1

The General Assembly could have rejected the charter in 1828, but the legislators considered the Chesterfield Railroad to be a feasible project. The railroad simply expanded upon tramways used at coal mines to move the mineral to the surface, with horses or mules pulling wagons whose wheels were guided by tracks.

The General Assembly did refuse the initial request for a charter for the proposed Potomac and Staunton Railroad in 1830. Backers of that proposal planned to build track 350 miles from Staunton to the Potomac River, and then to the Ohio River. The legislators considered it too grandiose to endorse with a charter.2

The Chesterfield Railroad transported coal from the mines ("pits") in Midlothian to the docks at Manchester, on the south bank of the James River. The demand for coal from local residents was low; they had plenty of wood for heating. Foundries (such as the Westham Foundry near modern-day Huguenot Bridge) and emerging industries in northern states were the primary customers of coal to be used for fuel.

Some municipalities bought coal for production of "coal gas" (methane). It was piped to buildings and used for lighting, as an alternative to wax candles and whale oil.

The price of coal delivered to a dock below the Fall Line was increased enough to justify building first the Midlothian Turnpike in 1802, and then a railroad two decades later. The railroad lowered transportation costs by one-third.

The State Engineer, Claudius Crozet, and Moncure Robinson designed and engineered the Chesterfield Railroad to operate primarily by gravity. At the time, steam-powered locomotives were an unproven technology, so the railroad did not rely upon them.

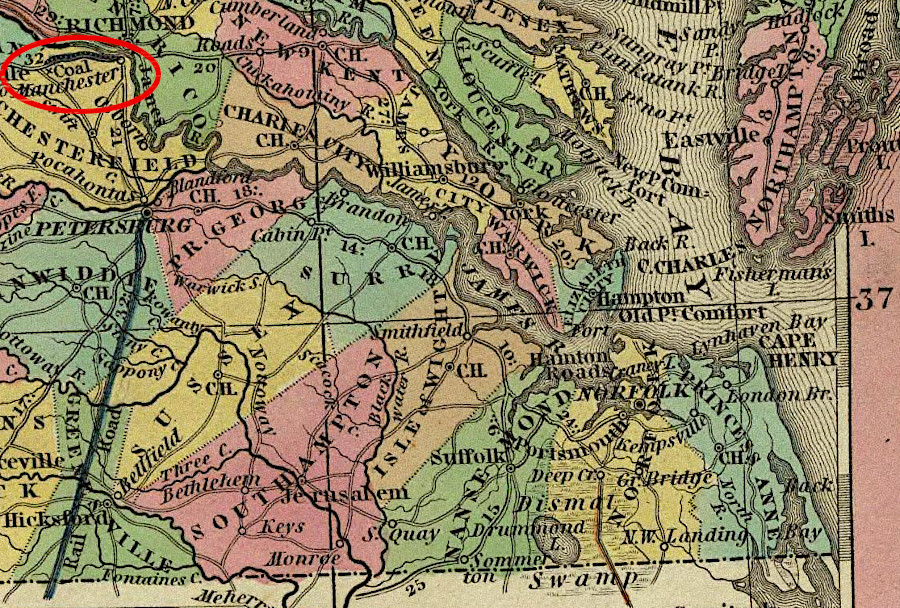

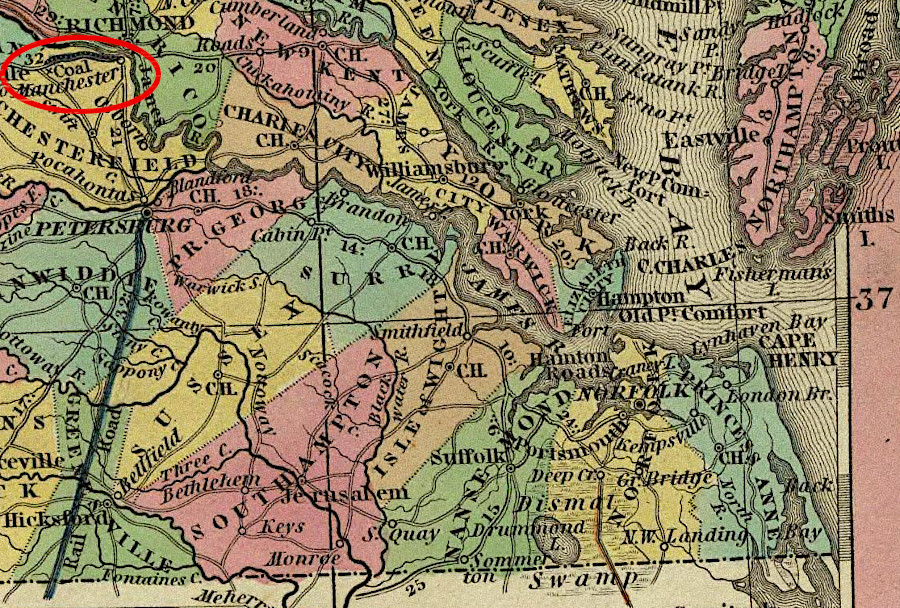

the Chesterfield Railroad brought coal to Manchester, while the Peterburg Railroad brought all sorts of traffic north from the Roanoke River

Source: David Rumsey Map Collection, New Map Of Virginia (by Henry S. Tanner, 1836)

The Chesterfield Railroad was designed so cars loaded with coal could be pulled downhill by horses and mules from the Midlothian mines to the James River. At the time, it was common to pull carts on rails with horses and mules at coal mine tramways, while steam-powered locomotives were an unproven technology:3

- During a three-hour eastbound trip, a single horse pulled down to tidewater two cars each carrying three tons of coal, and a pair of mules pulled three such cars.

At least as early as 1811, the Falling Creek Railroad in Chesterfield County had already demonstrated the feasibility of using a wooden car with wooden wheels on wooden rails. On the Chesterfield Railroad, wheels followed a rail that consisted of a 0.5-inch thick iron strap on top of wooden stringers. The 4'6" gauge was consistent with the width of wagons on Virginia's dirt roads.4

- The coal cars were simple boxes on wheels. Coal was placed in all but the last one. Mules or horses were put into the last car. When the brakes were released the train moved down hill to Manchester. It was unloaded and the mules hitched up to pull the empty cars back to the mines.

The trip from the mine to Manchester was not a simple one-way joyride for the animals, requiring no work on their part. The initial descent from Midlothian followed the watershed of Falling Creek, but Manchester was across the watershed divide rather than at the mouth of the creek. Animal power plus an inclined plane were used to pull loaded cars eastward and uphill across the watershed divide, and to drag the empty cars westward back to the mine.

A horse could pull two cars each loaded with three tons of coal east to Manchester, taking three hours to make the 13.5 mile trip. Two mules could pull three loaded cars. Pulling extra cars required 4-horse and 6-horse teams to get up the eastern side of the Falling Creek watershed, on the way to the docks at Manchester. The railroad kept 50-60 animals busy. Some trips stopped two miles short of Manchester, if coal was being transferred from an overpass there into cars on the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad.

The valley floor of Falling Creek was 80' below the western ridge of the watershed divide. An 1,100' long inclined plane was built to use the force of gravity to get the empties up the western side of the valley and back to the mine. The system required building two parallel tracks so cars could pass each other in opposite directions, and timing shipments of 80 cars/day so loaded cars headed to Manchester arrived at the ridgetop when there were empty cars 80' lower down in the valley.

The steep uphill grades were on the return trip. Horses and mules pulled empty cars on the gradual uphill climb from the docks to the eastern side of the Falling Creek Valley. There, coal-carrying cars lowered down the steep western slope of Falling Creek Valley pulled two empty cars up the slope.

Cars loaded with coal going eastward, at the top of the ridge and headed down to Falling Creek, would be connected by rope to cars at the bottom of the valley that needed to move up the steep hill. As the loaded cars then moved downhill, the mechanical energy would be used to overcome gravity and pull empty cars uphill:5

At the top of the watershed divide, the animals may have been loaded into an empty car and allowed to glide downhill with rest of the empty cars. A scenario that involves less risk of harm to the high-value horses and mules is that they were unhitched from the cars at the top, the empties were then allowed to roll downhill into the Falling Creek valley by gravity, while the animals were walked downhill.

- ...an ingenious drum and rope device raised two empty coal cars 80 feet within a distance of 1,000 feet up the western slope of the Falling Creek Valley. Ropes that led from a large drum were attached to ascending and descending cars; as one rope wound, the other unwound, enabling two loaded cars to descend while two empty ones ascended.

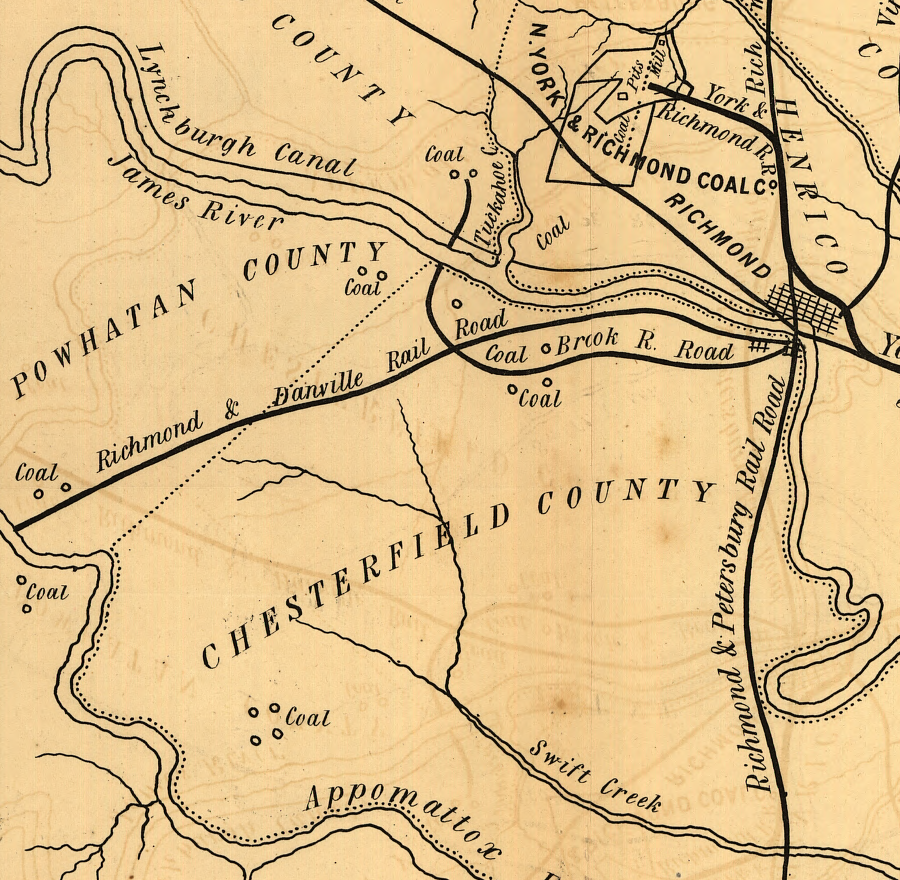

Though Harry Heth was one of the key leaders for development of the Chesterfield Railroad, some of his coal mines in Chesterfield County were not close to it. He build another set of tracks from his Black Heath mine, past other pits, to the James River opposite Tuckahoe Creek. His coal had to be loaded from rail cars into boats, and then moved on the north bank of the river into boats that were pulled by mules down the James River and Kanawha Canal to Richmond.

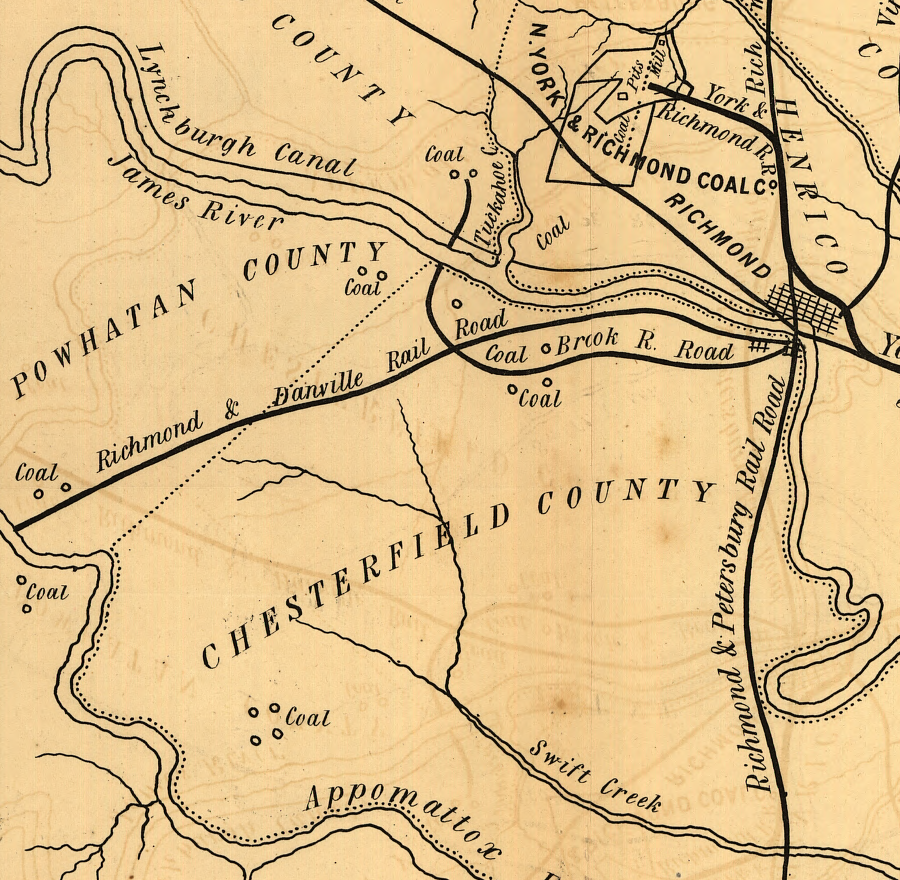

coal in Chesterfield County was transported to market by wagon, canal boat, and railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Springfield & Deep Run estates on the Coal Lands of the N. York & Richmond Coal Co, in Henrico Co. Virginia (by S. Herries Debow, 1856)

Not using the Chesterfield Railroad involved higher costs, and delays when water levels was too high for safe ferrying across the James River or two low for floating down the canal. Though some mine owners continued to ship by wagon down the Midlothian Turnpike, the railroad reduced such traffic by 90%.6

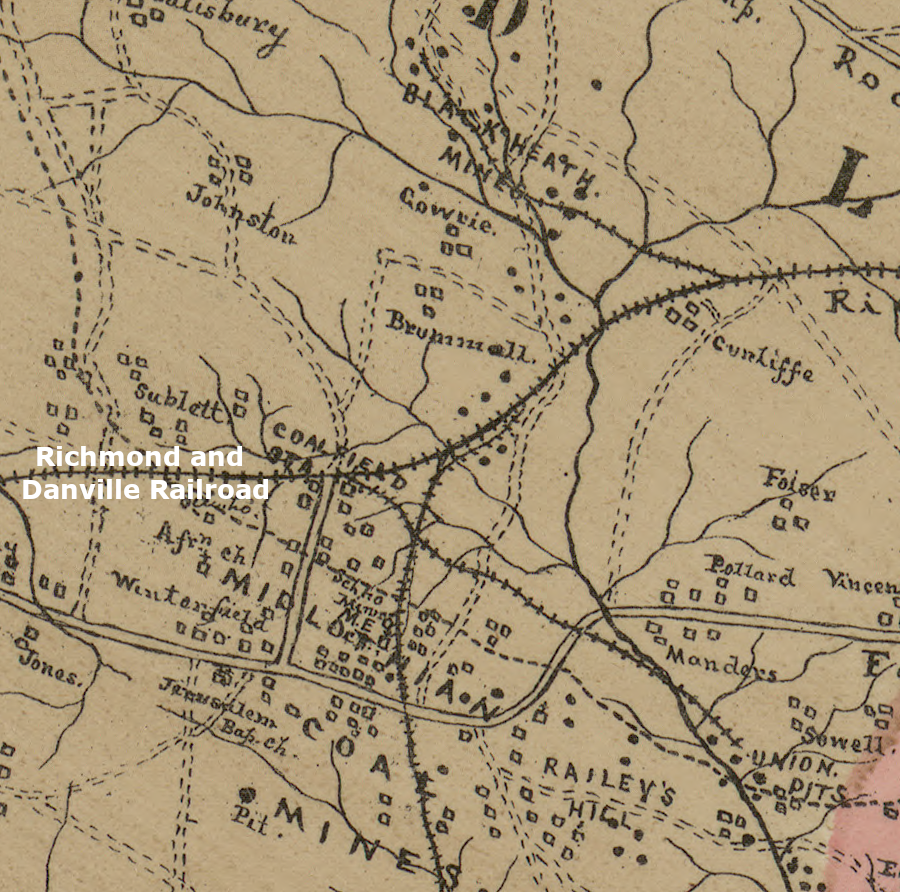

The Chesterfield Railroad was driven out of business by a competing railroad. In 1847, the General Assembly chartered the Richmond and Danville Railroad. In 1848, the legislature authorized the new railroad to acquire the Chesterfield Railroad. When the Richmond and Danville Railroad track reached Coalfield Station in 1850, its locomotives could haul coal at less cost to the docks at Richmond.

The Chesterfield Railroad claimed it had a monopoly on delivering coal to wharfs on the south bank of the James River, opposite Rocketts. The Richmond and Danville Railroad could purchase the Chesterfield Railroad and eliminate the competition, but initially the stockholders demanded too high a price. The Richmond and Danville Railroad won a court case and built a spur track to deliver coal there in 1851, and at that time operations ceased on the Chesterfield Railroad.

In 1854, the Richmond and Danville Railroad ran a spur to the Black Heath and Grove Shaft mines to haul their coal to Manchester.

the Richmond and Danville Railroad out-competed the Chesterfield Railroad and transported the Midlothian coal at lower cost

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Chesterfield County, Va (by Joseph Edgar LaPrade, 1888)

In 1858, the Richmond and Danville Railroad acquired the property of the Chesterfield Railroad located between Manchester and the coal-loading wharf on the south bank of the James River. After payment for that real estate, the Chesterfield Railroad stock was worthless.

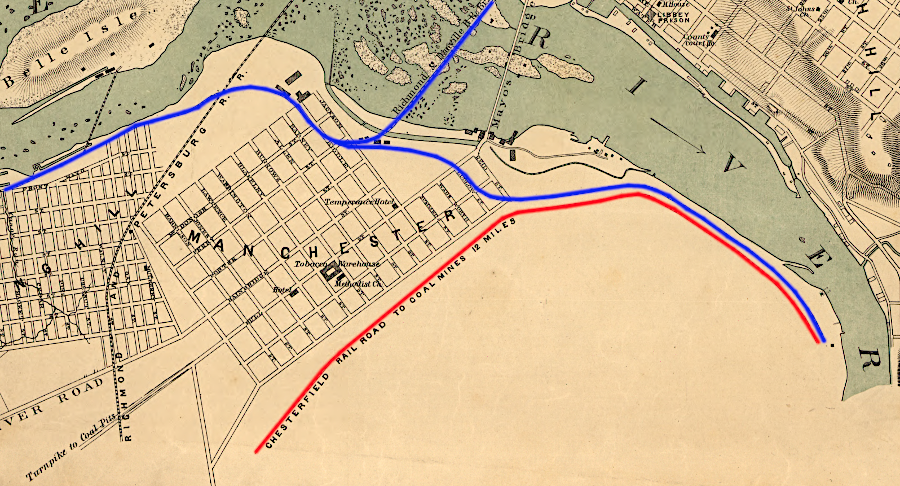

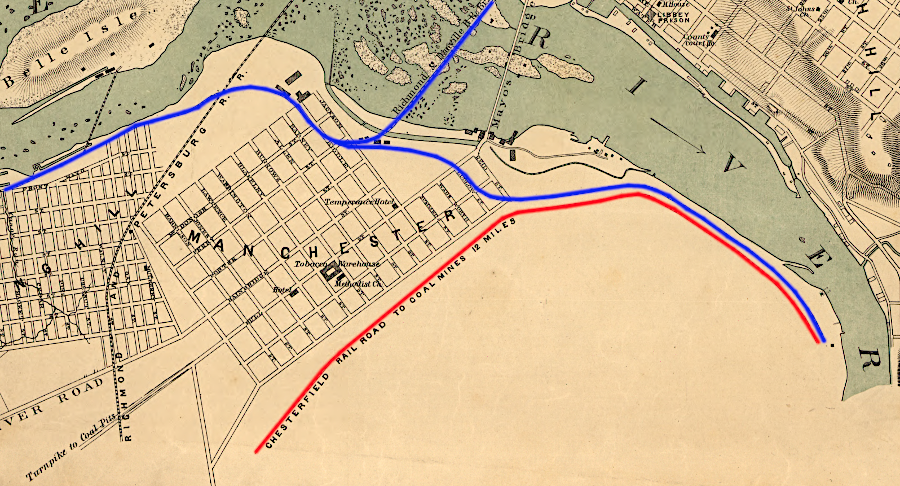

the Richmond and Danville Railroad (blue) purchased real estate from the Chesterfeld Railroad (red) between Manchester and the James River wharves

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Richmond, Virgini (by US Coast Survey, 1864)

The infrastructure built by the Chesterfield Railroad was not immediately demolished. During the Civil War, the demand for coal at Tredegar and other operations in Richmond was great enough to justify operating both steam-powered trains on the Richmond and Danville Railroad and also the old incline rail system of the Chesterfield Railroad. Delivery was interrupted when Federal cavalry managed to burn the Coalfield Station and rip up track of the Richmond and Danville Railroad in May, 1864.7

Links

References

1. Frederick C. Gamst, Marilou Gamst, "Virginia's First Railroad, on Falling Creek, about 1810," Railroad History, Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, No. 168 (Spring 1993), https://www.jstor.org/stable/43521633; "Chesterfield Railroad Timeline: 1824 to 1851," Mid-Lothian Mines Park, https://www.midlomines.org/chesterfield-railroad.html (last checked November 15, 2020)

2. Charles W. Turner, Charles F. Turner, "The Early Railroad Movement in Virginia," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 55, Number 4 (October 1947), pp.354-355, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4245511 (last checked October 10, 2021)

3. Frederick C. Gamst, Marilou Gamst, "Virginia's First Railroad, on Falling Creek, about 1810," Railroad History, Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, No. 168 (Spring 1993), p.8, p.13, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43521633 (last checked October 10, 2021)

4. Barbara Irene Burtchet, "A history of the village of Midlothian, Virginia, emphasizing the period 1835-1935," University of Richmond Masters thesis, May 1983, pp.8-9, pp.14-16, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1491&context=masters-theses; Frederick C. Gamst, Marilou Gamst, "Virginia's First Railroad, on Falling Creek, about 1810," Railroad History, Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, No. 168 (Spring 1993), p.8, p.13, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43521633 (last checked November 15, 2020)

5. Martha W. McCartney, "Historical Overview Of The Midlothian Coal Mining Company Tract - Chesterfield County, Virginia," December, 1989, https://www.midlomines.org/historic-overview.html; "Chesterfield Railroad Timeline: 1824 to 1851," Mid-Lothian Mines Park, Chesterfield County, https://www.midlomines.org/chesterfield-railroad.html; "An Act Authorizing the Chesterfield Railroad Company to Trasfer Their Road to the Richmond and Danville Railroad Company," Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Commonwealth of Virginia, 1848, p.184, https://books.google.com/books?id=NAVAAAAAYAAJ; Frederick C. Gamst, Marilou Gamst, "Virginia's First Railroad, on Falling Creek, about 1810," Railroad History, Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, No. 168 (Spring 1993), p.13, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43521633 (last checked November 15, 2020)

6. Barbara Irene Burtchet, "A history of the village of Midlothian, Virginia, emphasizing the period 1835-1935," University of Richmond Masters thesis, May 1983, p.18, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1491&context=masters-theses (last checked June 22, 2020)

7. Barbara Irene Burtchet, "A history of the village of Midlothian, Virginia, emphasizing the period 1835-1935," University of Richmond Masters thesis, May 1983, pp.44-46, p.57, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1491&context=masters-theses; Fairfax Harrison, A History of the Legal Development of the Railroad System of Southern Railway Company, 1901, pp.80-82, https://books.google.com/books?id=0IkjAQAAMAAJ (last checked June 22, 2020)

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places