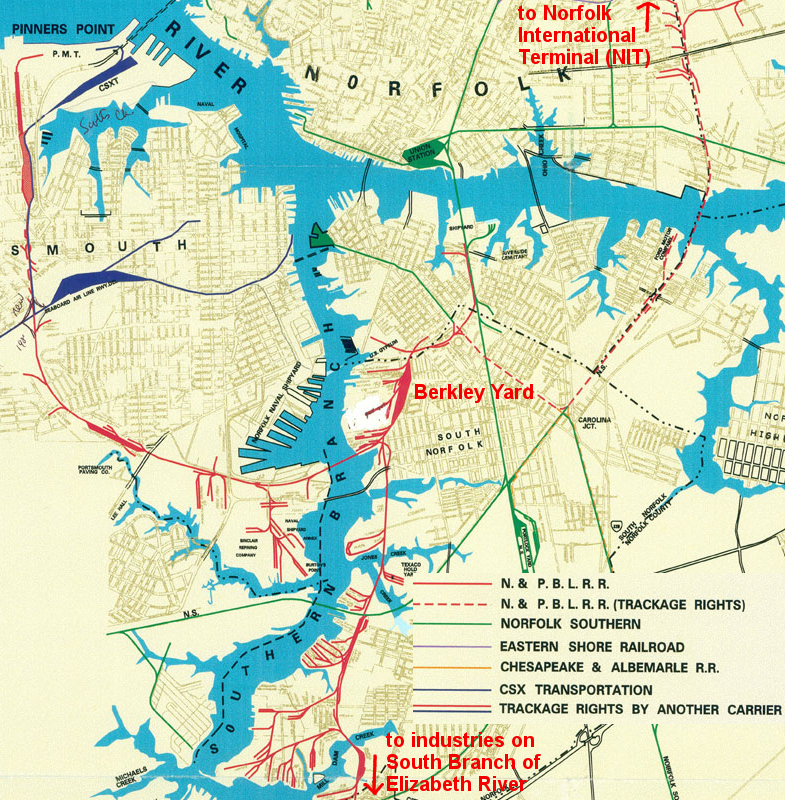

the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line services industries along the South Branch of the Elizabeth River, as well as two shipping terminals owned by the Virginia Port Authority

Source: Norfolk & Portsmouth Belt Line Railroad Co., System Map (Figure 2)

the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line services industries along the South Branch of the Elizabeth River, as well as two shipping terminals owned by the Virginia Port Authority

Source: Norfolk & Portsmouth Belt Line Railroad Co., System Map (Figure 2)

The Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line was chartered initially in 1896 as the Southeastern and Atlantic Railroad. Its name was changed in 1898, when the railroads in Hampton Roads were able to complete negotiations for using it as a "neutral" vehicle for switching cars between the different lines. As described by the Port of Virginia:1

The original eight railroads were the New York, Philadelphia & Norfolk Railroad; Norfolk & Western Railroad; Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad; Southern Railway Company; Atlantic & Danville Railroad; Atlantic Coast Line; the original Norfolk Southern Railroad; and Seaboard Air Line Railroad.2

Today, the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line has two stockholders. The Norfolk Southern owns 57% and CSX owns 43% of the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line.

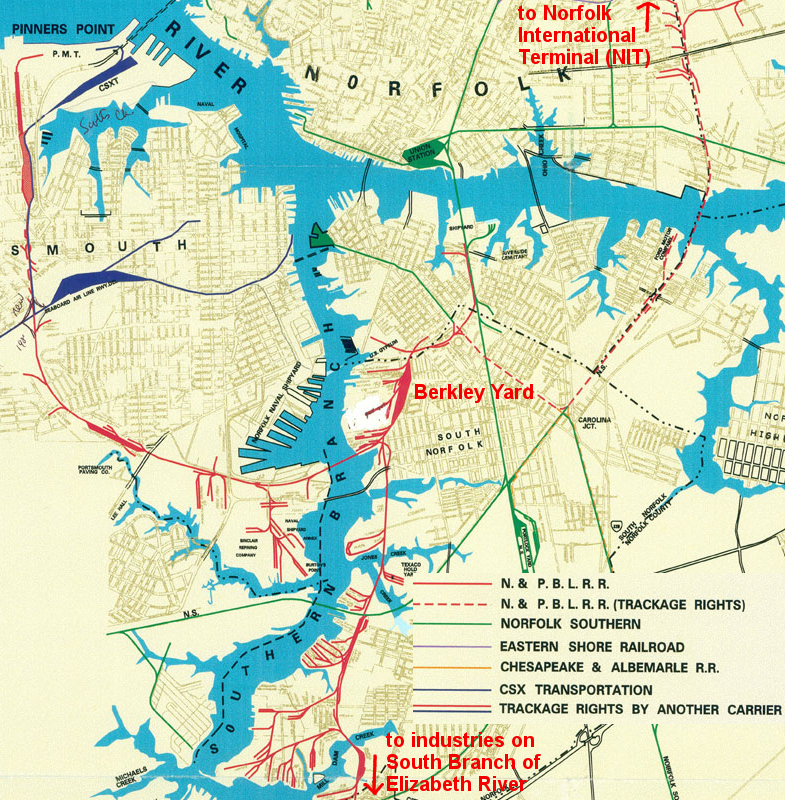

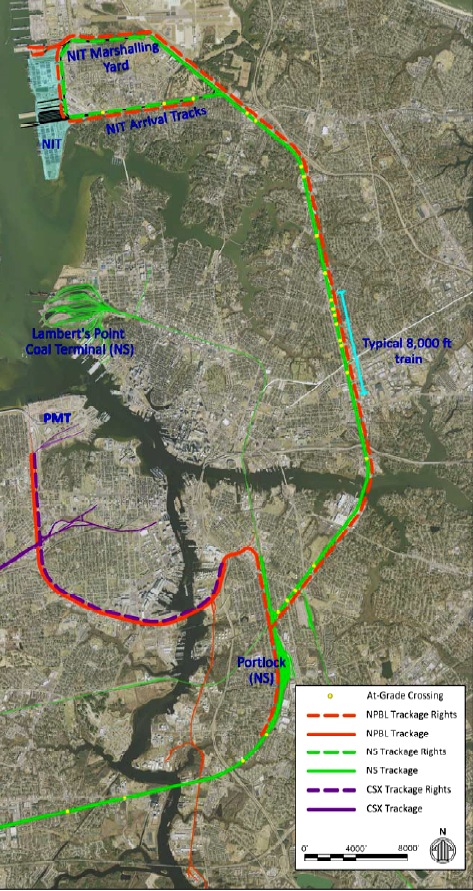

the Norfolk Southern and the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line both transport cargo from the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT)

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 15)

The railroad owns 36 miles of track connecting directly to Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), and also has 27 miles of "trackage" rights across the Norfolk Southern line to connect to the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) from the City of Chesapeake and the short-line railroad's yard at Berkely.

It switches rail cars loaded with cargo from both terminals and various industrial sites in Norfolk and Portsmouth to either Class I railroad. It also handles interchanges with the Chesapeake and Albemarle Railroad and Bay Coast Railroad at the Portlock Yard of Norfolk Southern. In 2025, it offered rail services to 24 industries located along its track.3

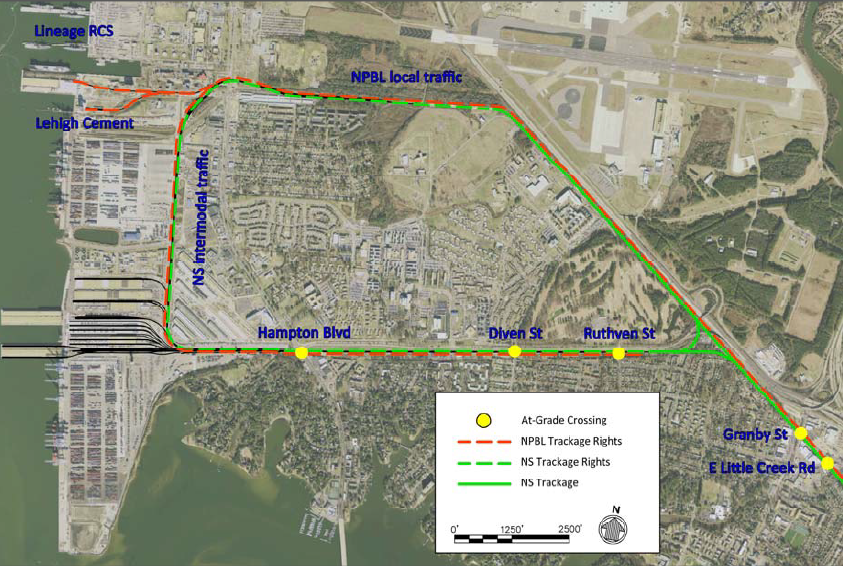

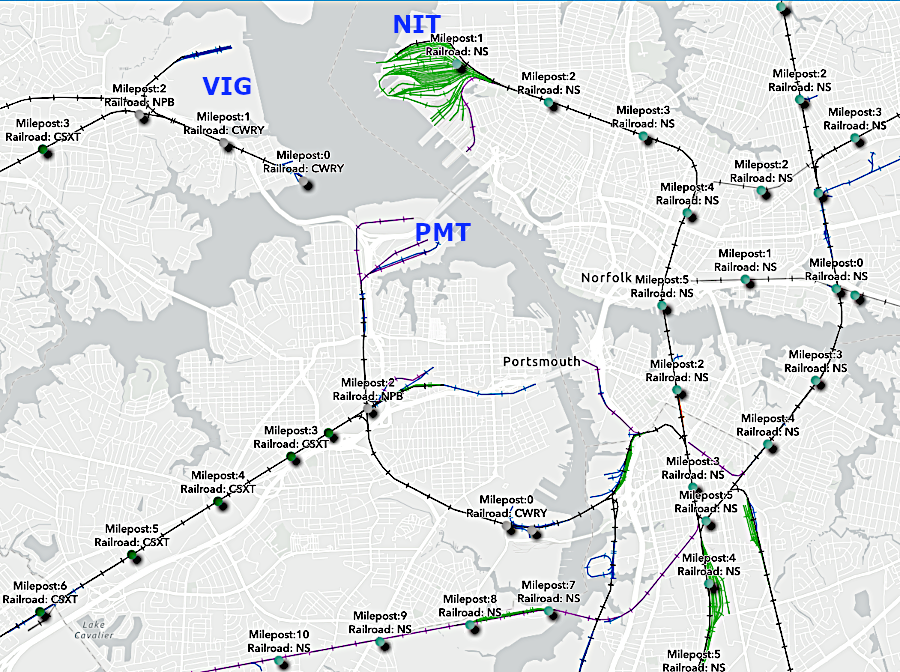

Norfolk Southern's Portlock Yard provides an interchange site for all short-line railroads in Hampton Roads except for the Commonwealth Railway

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line does not connect to the Virginia International Gateway (VIG). The separate Commonwealth Railway provides "neutral" rail access to that terminal, creating competition between the Norfolk Southern and CSX for long-distance hauls of cargo. The Commonwealth Railway and the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line have no physical connections with each other and are separate companies, but all the shippers in the Hampton Roads must interact with each other as they deal with capacity planning, local/state agencies, and customers.

The short-line Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line specializes in moving rail cars from industrial sidings with one switching engine. Car movements require going just a few miles at slow speeds to railyards where large trains are assembled. The railroad moved 22,700 rail cars in 2013, primarily loaded with grain.4

In that same year, Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) moved approximately 280,000 containers by rail. Norfolk Southern had direct access to that terminal, and assembled its arriving and departing trains each day without using the short-line.5

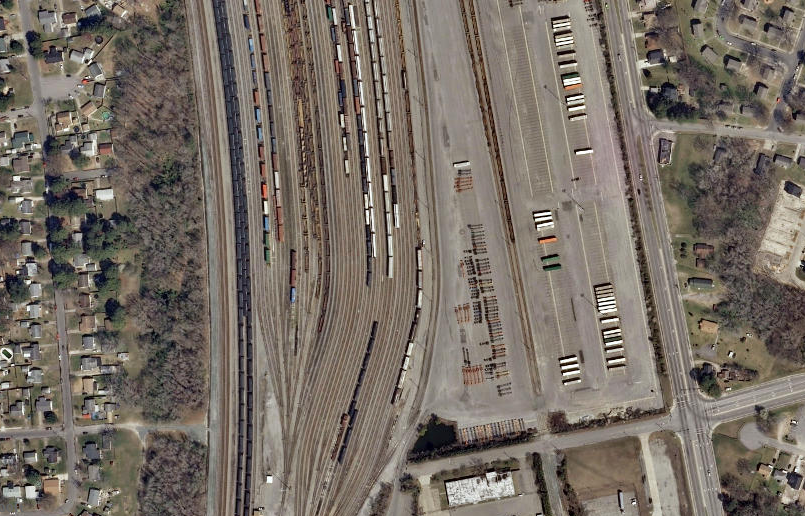

the Norfolk Southern owns track (Sewell's Point Line) that connects directly to the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), so it has little need for the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line to transport containers from that terminal

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 12)

The major railroads operate trains with multiple locomotives move the long trains (with over 100 cars, stretching over a mile) for long distances. As described by the railroad's vice-president, handling rail cars for the "first and last mile" of the journey with switching at many different sites is a different business:6

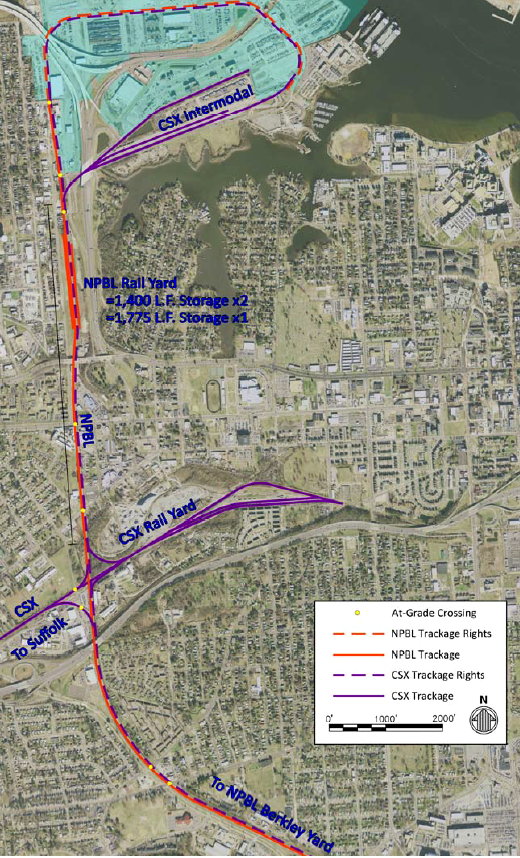

CSX has no track to the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), but the "neutral" Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line has rights to use the Norfolk Southern tracks and deliver containers to CSX

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 2)

Ensuring fair competition was the reason the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad triggered formation of the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line in 1898. After building its rail line south through the Eastern Shore, constructing the new town of Cape Charles for a car float operation that barged loaded rail cars across the water to Norfolk, the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad struggled to get other railroads to share traffic. The Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line was formed to serve as a "neutral" carrier, owned by the competing railroads but interchanging cars fairly with each of them.7

Until 1917, all train crews got on board the steam locomotives at the Port Norfolk Yard in Portsmouth, where all equipment was also maintained. Starting in 1917, a second rail yard was created at Sewells Point.

In 1956, the railroad switched to diesel locomotives. It built the Berkley Yard in South Norfolk as the central point for train crews to report for duty and for maintenance. The Sewells Point yard was sold to the Virginia Port Authority in 2010, and now serves as the port's marshalling yard for assembling trains.8

To go between the Berkley Yard and the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line used trackage rights over tracks owned by Norfolk Southern. The rights were granted through a 99-year lease signed in 1918, but the Virginia Port Authority assumed they would be renewed.

Those trackage rights are essential for the rival railroad, CSX, to transport cargo over Norfolk Southern's tracks and through the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT). Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line trains must stop at Norfolk Southern's Portlock Yard and switch locomotives to the other end of the train, and CSX must interchange at Berkley Yard. The delays/costs associated with extra train movements limit the competitiveness of intermodal rail at Norfolk International Terminal (NIT). As a result, most CSX traffic through Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) consists of non-containerized cargo such as large electrical transformers.

The Virginia Port Authority considered providing dual access to the terminal by constructing a new rail line for CSX. That option was quickly dropped, because:9

The port could upgrade Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line capacity, or support cross harbor barge service to Portsmouth Marine Terminal where CSX has direct access, but the investment required to provide competitive direct rail access is low-priority. Norfolk Southern will retain an advantage in lower-cost rail transport at Norfolk International Terminal (NIT), while many customers who ship containers via CSX have the option to use the Virginia International Gateway (VIG) terminal.

Rail access at the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) is the reverse of the situation at the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT). CSX trains have direct access to the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) via trackage rights on the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line, and has leased the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line marshalling yard adjacent to the Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT). In contrast, cargo to be carried to final destinations by the Norfolk Southern must interchange with the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line at the Portlock Yard.10

Norfolk Southern, owner of 57% of the stock, appointed four of the six directors on the board of the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line. All the railroad's managers were formerly employed by Norfolk Southern.

In 2018, CSX sued both the Norfolk Southern and the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line railroads. CSX claimed that they conspired to limit its access to cargo at Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) by setting an excessively high rate for moving containers. Only CSX had to use the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line to deliver freight to that shipping terminal; Norfolk Southern used its own tracks to reach it.

CSX, the Class 1 railroad component of CSX Transportation (CSXT), claimed illegal constraint of trade:11

CSX has direct access to Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT) and Norfolk Southern does not, but most container traffic has been moved to Virginia International Gateway (VIG)

Source: Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment, Master Rail Plan for the Port of Virginia (Figure 17)

In 2025 the US Supreme Court rejected the CSX claim that Norfolk Southern had violated antitrust law. The "switch rate" of $210 per train car had been set in 2009, and judges at the Fourth Circuit Court and the US Supreme Court ruled that the statute of limitations had expired before CSX filed suit in 2018.

CSX continued to seek redress through review by the Surface Transportation Board. Norfolk Southern needed approval from that Federal agency; its acquisition of majority ownership through mergers had not been followed by obtaining a required permit to take formal control over the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line.12

One advocate for CSX wrote in 2025:13

CSX enlisted former govern Jim Gilmore to support their position. He wrote in an opinion piece that the $200 fee imposed on CSX to move each railcar to the Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) was excessive, and:14

Commonwealth Railway serves Virginia International Gateway (VIG), CSX serves Portsmouth Marine Terminal (PMT), and both Norfolk Southern and Norfolk and the Portsmouth Belt Line serve Norfolk International Terminal (NIT)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Norfolk Southern respond that the charges reflected the actual costs to operate the Norfolk and Portsmouth Belt Line. Norfolk Southern claimed that CSX was seeking a below-cost rate to ship containers to the terminal in Norfolk, and that its competitor railroad was unfairly subsidized to move containers to a Portsmouth terminal:15