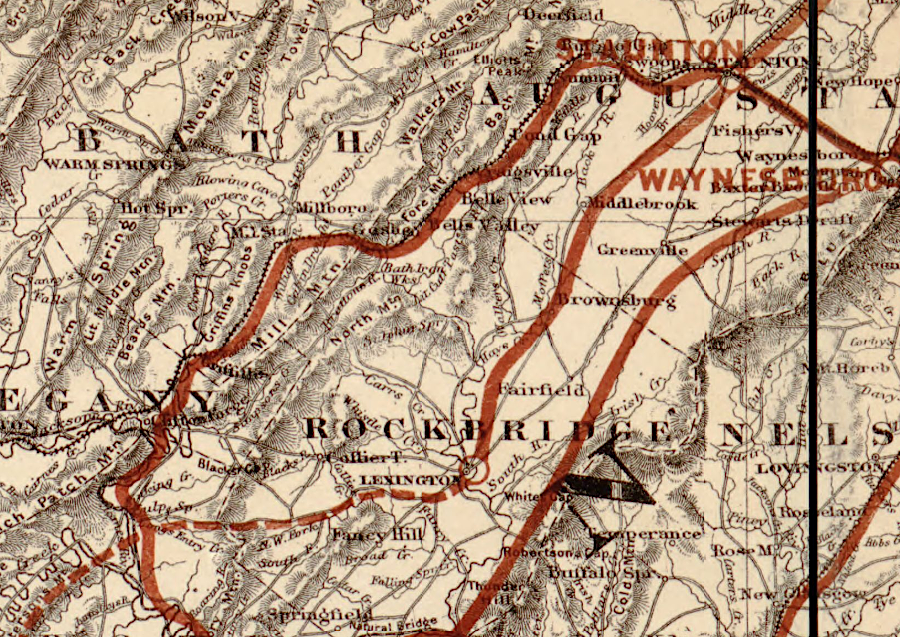

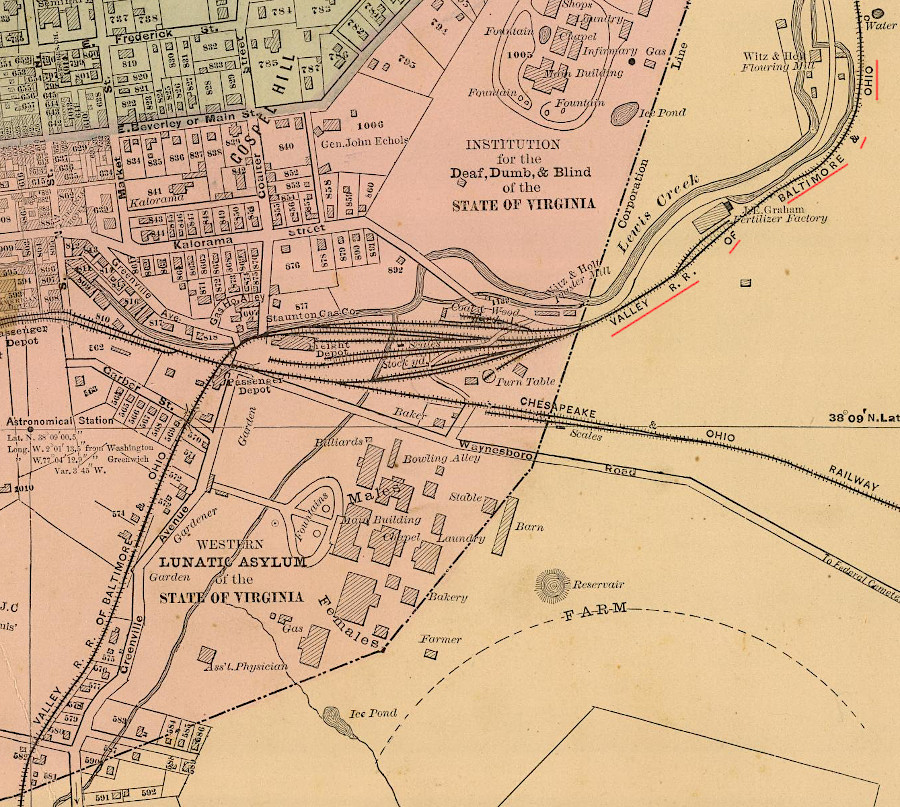

the Valley Railroad planned to build south of Lexington

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio Railroad connecting the railroads of Virginia with the railroads of Kentucky (1881)

the Valley Railroad planned to build south of Lexington

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio Railroad connecting the railroads of Virginia with the railroads of Kentucky (1881)

The General Assembly issued a charter for the Valley Railroad on February 23, 1866.1

The Valley Railroad was built west of Massanutten Mountain, and it competed with the already-built Shenandoah Valley Railroad located east of the mountain. Construction of two north-south railroads through the Shenandoah Valley was financed after the Civil War by competing groups of investors in Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Both wanted to build south to the Atlantic Mississippi & Ohio Railroad, which ran from Lynchburgto Bristol. That railroad provided a link to the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad Company. A railroad connection would allow freight from the Deep South states to be brought north to the port of Baltimore.

The majority of the traffic on the Valley Railroad was expected to be freight and passengers that started and ended their trips outside of Virginia, rather than originated within the state. Both the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad expected their lines through the Valley and Ridge province to become trunk lines carrying southern cotton and other agricultural products north, and bringing manufactured goods south from factories in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York.

In the end, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad won the race to build the railroad link to the Deep South. It built track on the eastern side of the Shenandoah Valley south to Staunton and Lexington. Further extension south to Big Lick (soon renamed Roanoke) connected it to the Atlantic Mississippi & Ohio Railroad at Big Lick. After making the connection, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad and the Atlantic Mississippi & Ohio Railroad were combined and renamed the Norfolk and Western Railroad.

The Valley Railroad, which lost the race, ended up building track to Lexington but no further south.

The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad financed construction of the Valley Railroad. It planned to extend its system south from Alexandria through the county seats west of Massanutten Mountain, and to build north to connect to its line at Winchester. The B&O was in competition with the Pennsylvania Railroad, which funded the rival Shenandoah Valley Railroad. The Shenandoah Valley Railroad chose to build on the eastern side of Massanutten Mountain, and the priority of its initial leadership was to create an alternative to shipping the iron and manganese there by boat down the Shenamdoah River.

The concept of building trunk lines through the Shenandoah Valley to carry freight that did not originate in the valley was a significantly different approach from the vision of pre-Civil War railroads. With the exception of the Winchester and Potomac Railroad and the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad, Virginia financiers planned for all of their pre-Civil War railroads to be routes from a western "hinterland" to an eastern Virginia port. Each railroad would designed to capture traffic from territory it crossed, ending it to a port city from which ships could sail through the Chesapeake Bay to foreign customers.

Business leaders in the port cities funded the railroads, recognizing that the traffic would be essential for economic development. Growth was limited in the one Virginia city on the Fall Line that failed to build a railroad connection to the Piedmont and Valley and Ridge, Fredericksburg.

The owners of the Manassas Gap Railroad consciously sought to increase business just at Alexandria. They had no intention of sending traffic from the Shenandoah Valley to Baltimore, Richmond, or any other port city. The Virginia Central directed its traffic to Richmond. The Virginia and Tennessee delivered freight and passengers to the port of Petersburg. For years, those railroads had sufficient influence over the Virginia General Assembly to block any authorizations ("charter") for connections between them or for new rivals crossing the Blue Ridge. Norfolk struggled to get a railroad connection to the Fall Line in Virginia, since businessmen and politicians focused on Richmond and Petersburg recognized that Norfolk would drain traffic away from those ports.

The concept of capturing a hinterland was also behind the first railroad to be constructed west of the mountains. The financiers were from Maryland and the destination port was Baltimore, not any Virginia city.

The Winchester and Potomac Railroad was built to Harpers Ferry in 1836, 18 years before the Manassas Gap Railroad reached Strasburg. At Harpers Ferry, railcars could be carried by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to Baltimore. After realizing how sending businbess to the primary port city in Maryland affected trade in Virginia, the Virginia General Assembly authorized no other railroad to connect to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad prior to the Civil War.

Control of access to the hinterland by competing port cities collapsed after the Civil War. After 1865, only Northern investors had the capital required to build the track needed to complete Virginia's raiload system. Investors in the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad raced to extend their systems south, taking advantage of the depressed economy and inability of bankrupt southern railroads to block railroad projects which would send traffic to rival Baltimore and Philadelphia.

The goal of the Valley Railroad investors was to create track south from the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to the town of Salem, south of the James River. At Salem, the Valley Railroad would connect with the Atlantic Mississippi & Ohio Railroad (known before the Civil War as the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad). Freight and passengers coming from the south through Tennessee would be steered towards Baltimore, boosting the city where the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was headquartered.

In 1881, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad and the Atlantic Mississippi & Ohio Railroad merged to become the Norfolk and Western Railroad, and a junction was completed at Big Lick (now Roanoke) in 1882.

After the Civil War, there was little capital in Virginia which could be invested in new railroads. Farm fences and livestock had been destroyed, along with much of the state's transportation and manufacturing infrastructure. Wealth invested by Virginia's richest people in Confederate bonds had evaporated, and the end of slavery had also eliminated much of what the slaveowners had considered to be "property." Northern funding was welcomed by farmers living west of the Blue Riadge to rebuild and expand the railroad network, providing access to new markets. Business leaders in Virginia's port cities no longer had the capacity to block competition.

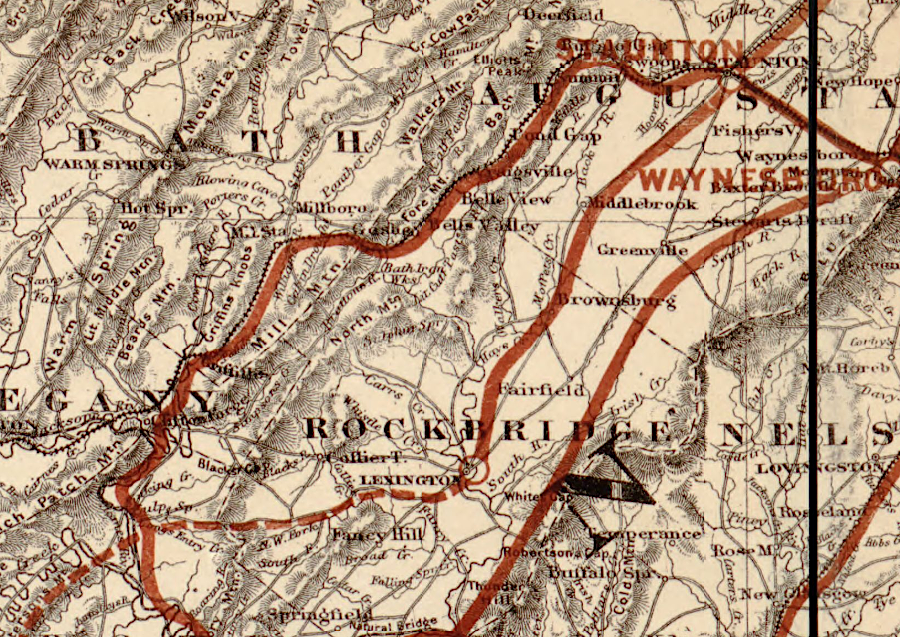

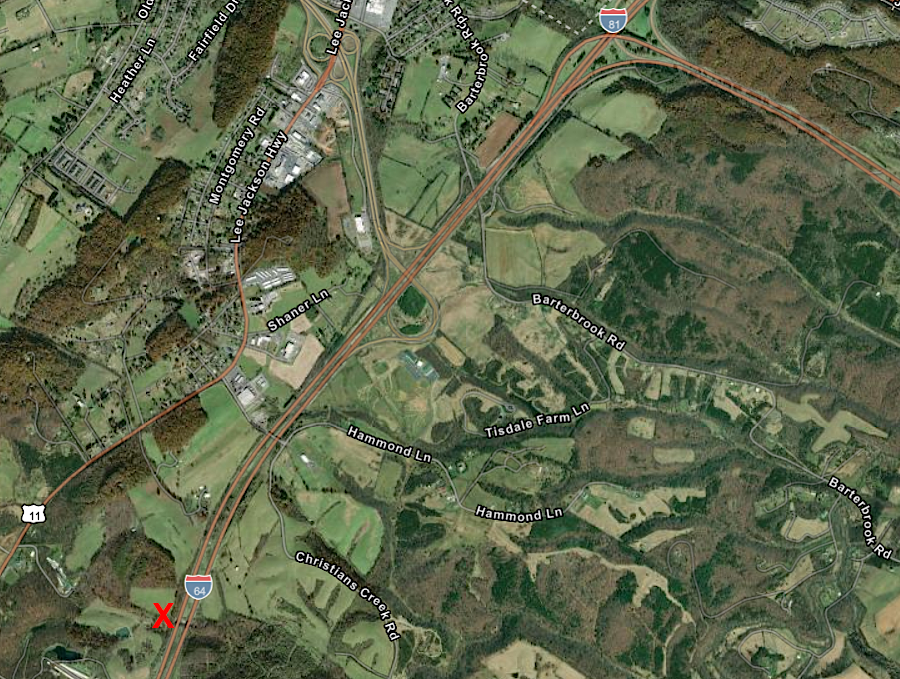

in 1878, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had not completed track south of Staunton

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road with its branches and connections (1878)

The Valley Railroad became known as the Valley Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, reflected how officials in Baltimore had control over the railroad in the Shenandoah Valley.

the Valley Railroad became the Valley Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Luray VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1893)

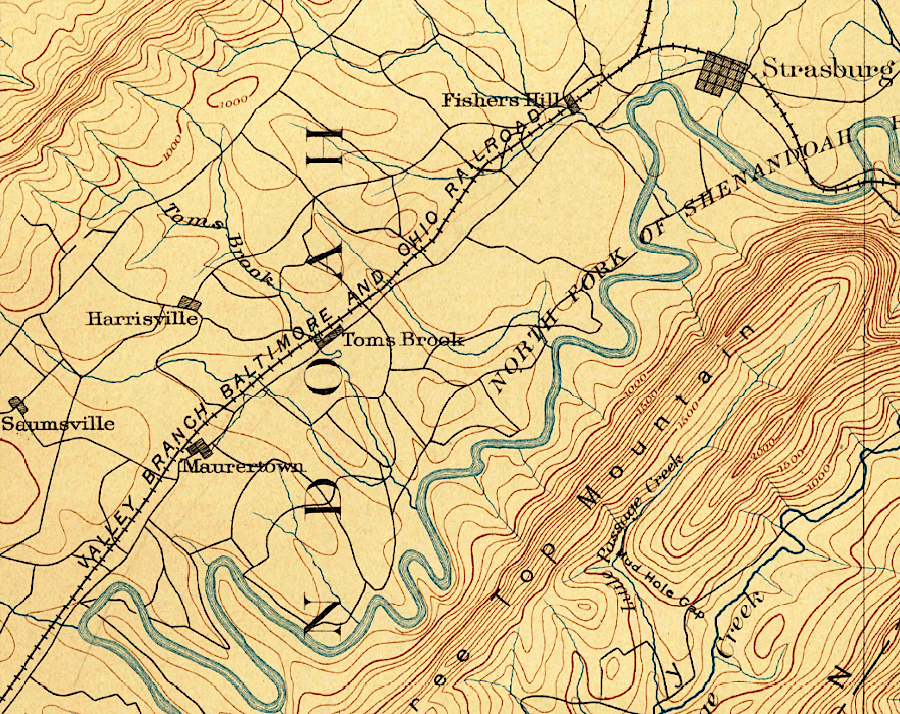

the Valley Railroad passed north-south through Staunton, while the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad passed east-west

Source: David Rumsey Map Collection, Staunton (by Jed Hotchkiss, 1885)

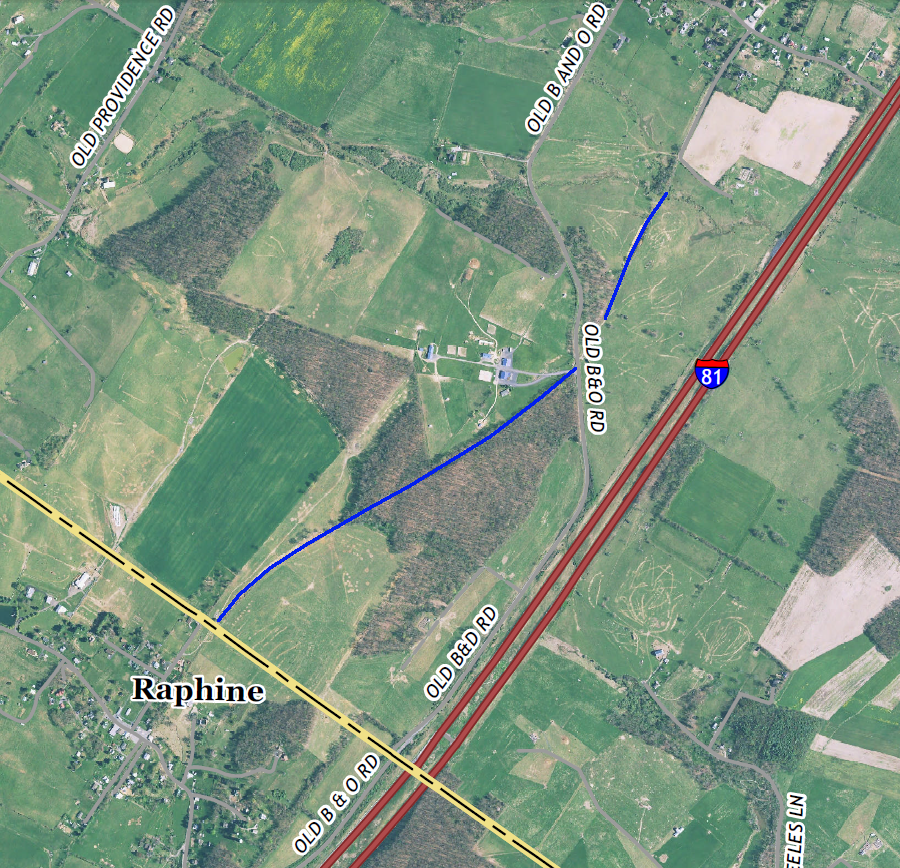

The extension to Lexington required bridging Folly Mills Creek south of Staunton. The four-arch limestone bridge was no longer need after the railroad ceeased operations to Lexington in 1942, but the bridge has remained in good condition.

The bridge was acquired by the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) when I-81 was constructed. That interstate highway used part of the railroad's route across the divide separating the Shenandoah and James rivers. The bridge is highly visible for drivers in the southbound lanes of I-81, and may be the most obvious feature of the former Valley Railroad. The is no public access to see the bridge from another angle, but the historic structure is maintained by the Virginia Department of Transportation as a landscape element.2

the Valley Railroad bridge acrosss Folly Mills Creek in Augusta County was completed in 1874

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.111)

the Folly Mills Creek Viaduct of the Valley Railroad is visible today from I-81 south of Staunton

Source: Kipp Teague, Valley Railroad Stone Bridge; ESRI, ArcGIS Online

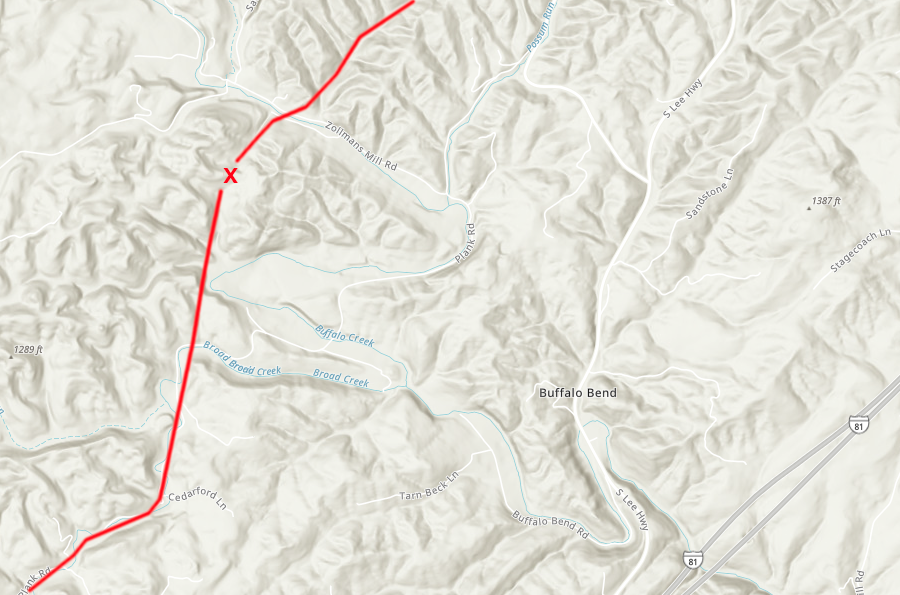

The Valley Railroad planned to build one tunnel, 400 feet long, south of Buffalo Creek. Initial excavation was begun and the north portal exposed, but no significant drilling and blasting occurred before all construction stopped in late 1874.3

a tunnel (red X) 400 feet long was planned on the Valley Railroad

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

traces of the Valley Railroad between Staunton- Lexington are still obvious on the landscape

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Versuvius, VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2019)

the Valley Railroad bridge over the North River at Mount Crawford used Bollman deck trusses

Source: Smithsonian Institution, The Engineering Contributions of Wendel Bollman (US National Museum Bulletin 240)

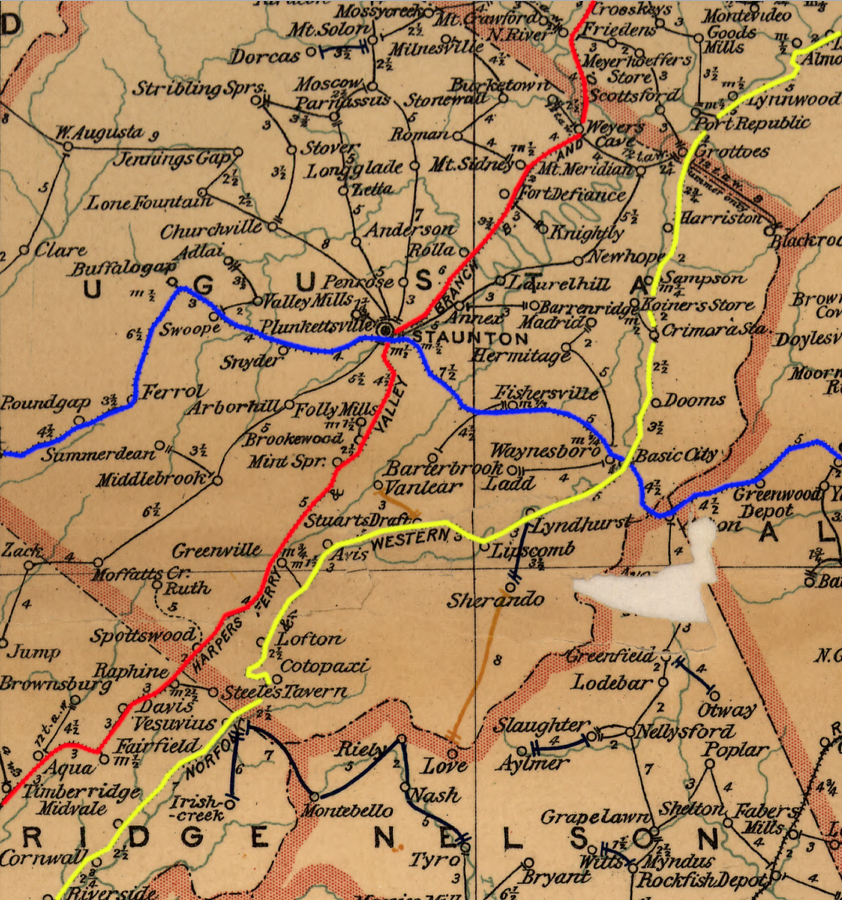

three railroads serviced the Shenanoah Valley in 1896 - Baltimore and Ohio (red), Norfolk and Western (yellow), and Chesapeake and Ohio (blue)

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the state of Virginia and West Virginia (1896)

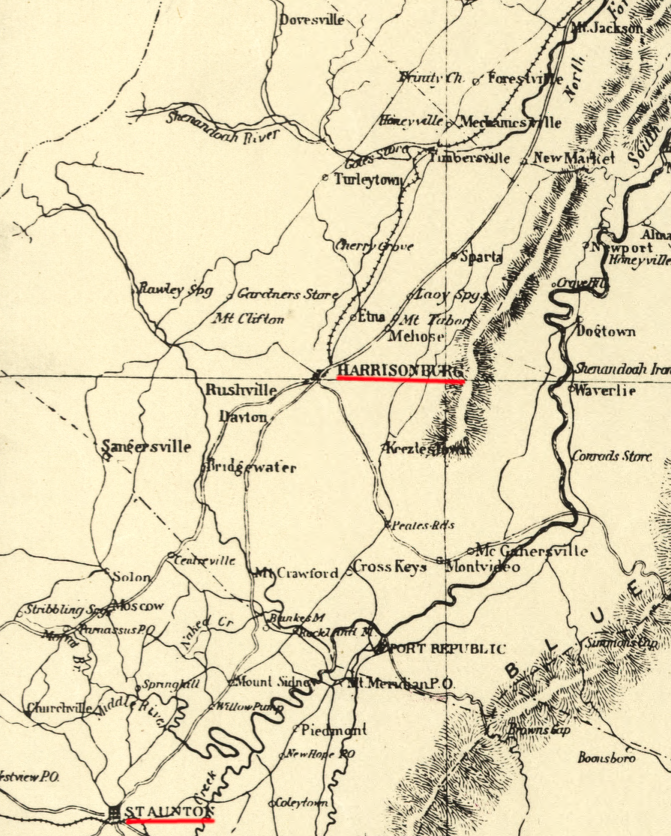

the Valley Railroad started at Harrisonburg, and headed south past Staunton to Salem

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the region between Gettysburg, Pa. and Appomattox court house, Va. (by Nathaniel Michler, 186_)

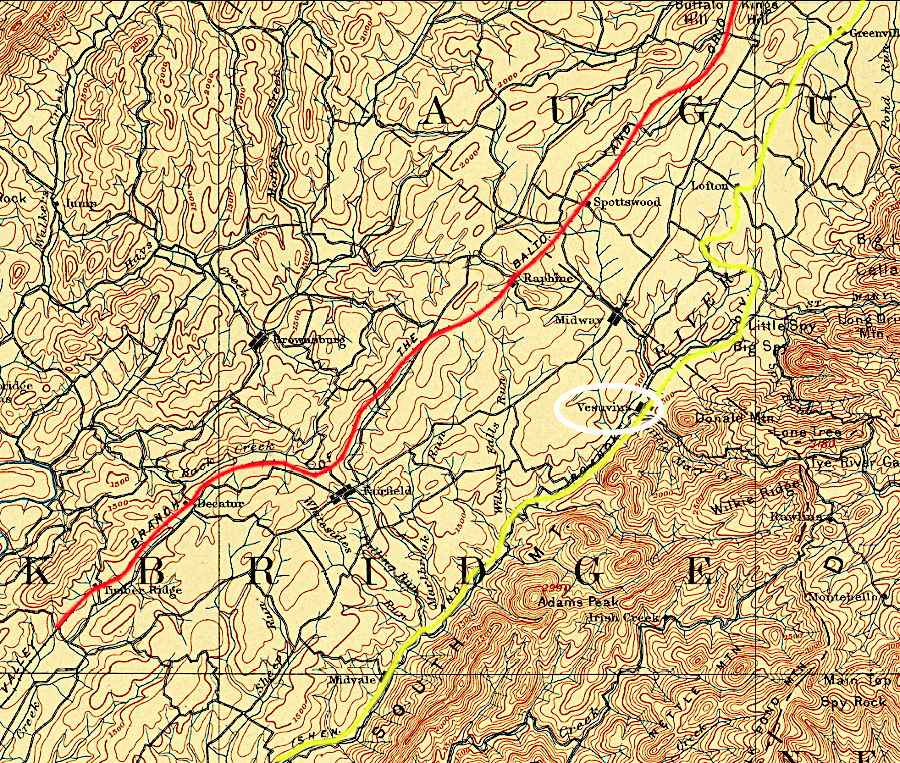

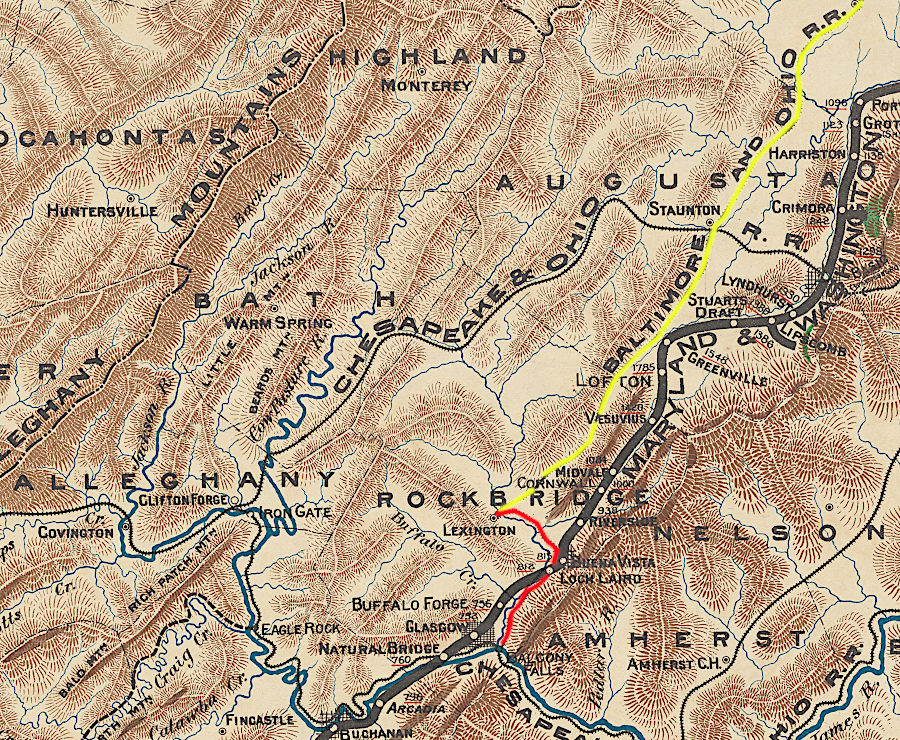

the Shenandoah Valley Railroad (yellow) built on the western edge of the Blue Ridge past the iron furnace at Vesuvius, while the Valley Railroad (red) built further west through the towns in the center of the valleys

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lexington, VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1894)

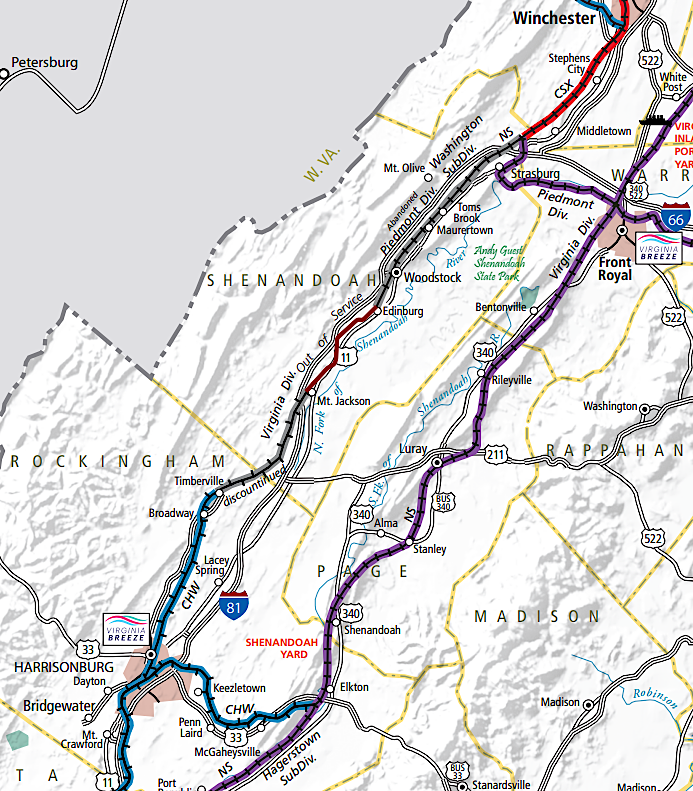

a portion of the former Valley Railroad between Strasburg-Harrisonburg is no longer in use

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Virginia Rail Map (2019)

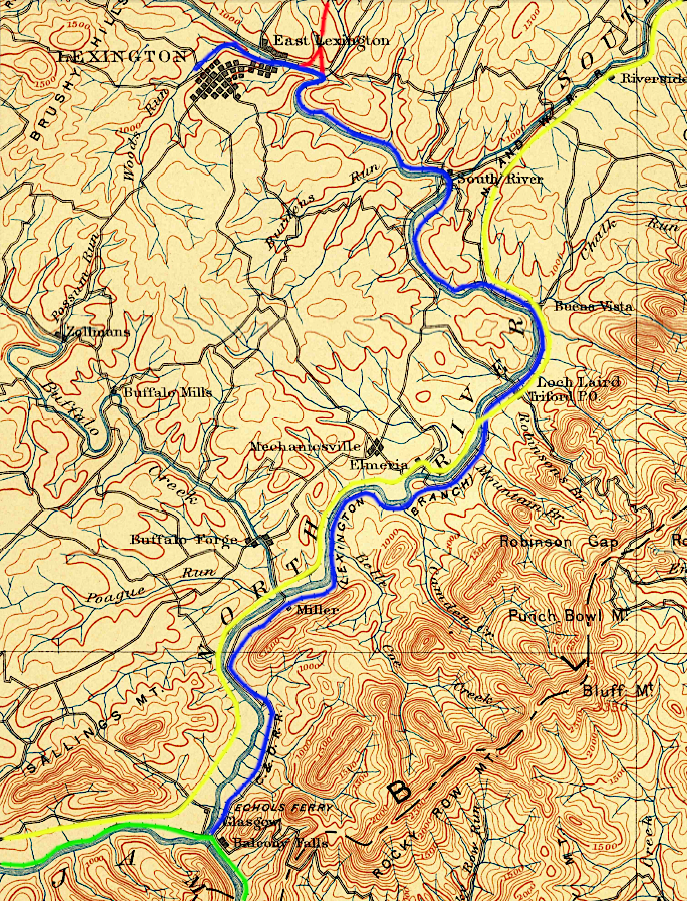

the Shenandoah Valley Railroad (yellow) connected with the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad (green) in 1882, while the Valley Railroad (red) joined the Lexington Branch of the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad (blue) only in 1883

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lexington, VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1894)

the Valley Railroad depot in Pleasant Valley, south of Harrisonburg

Source: Kipp Teague, former Valley Railroad depot, Pleasant Valley, Virginia; ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Valley Railroad only got to Lexington (yellow line), where it connected to a branch of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (red)

Source: New York Public Library, Mineral territory tributary to Norfolk and Western Railroad (1890)

Poor House Tunnel underneath Valley Railroad (Rockbridge County)