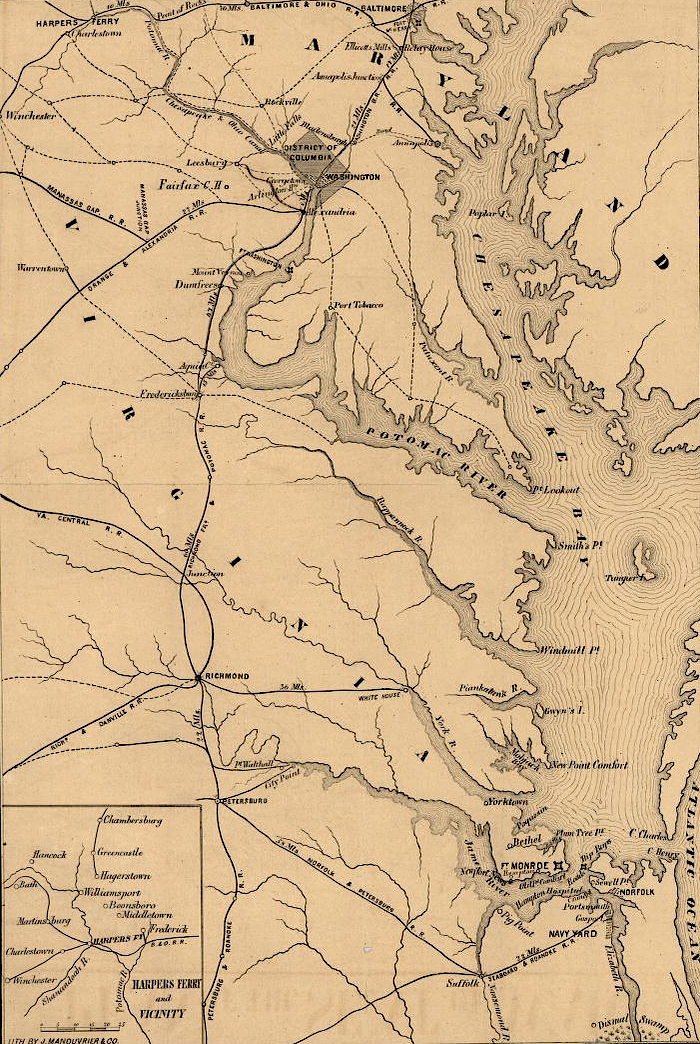

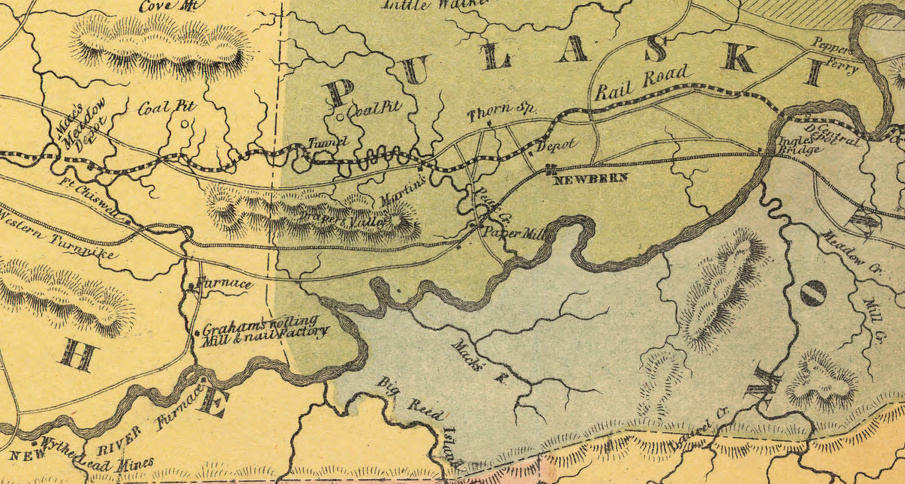

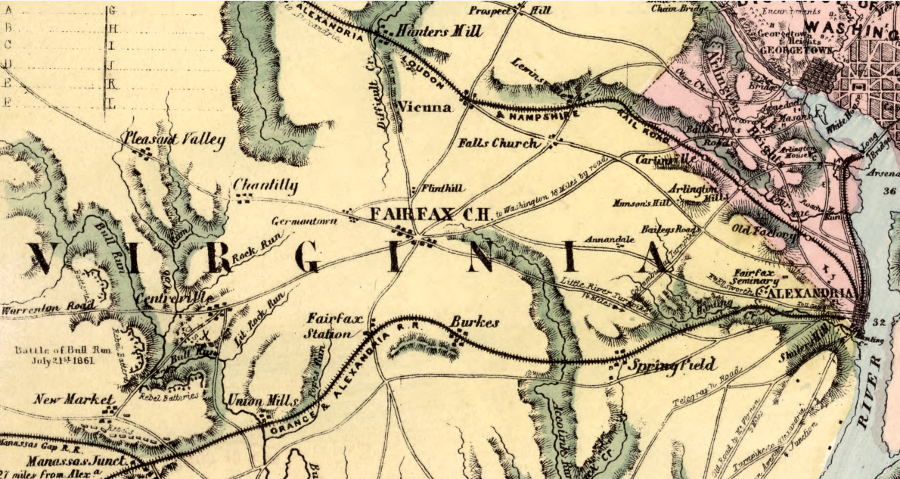

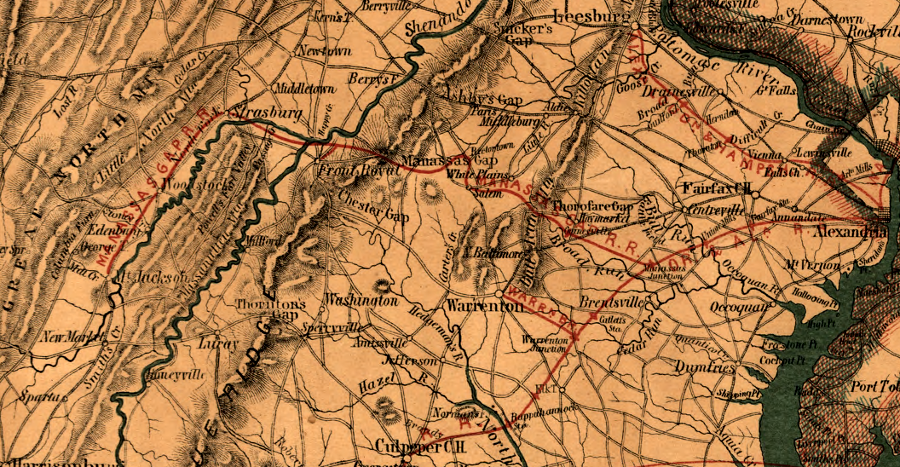

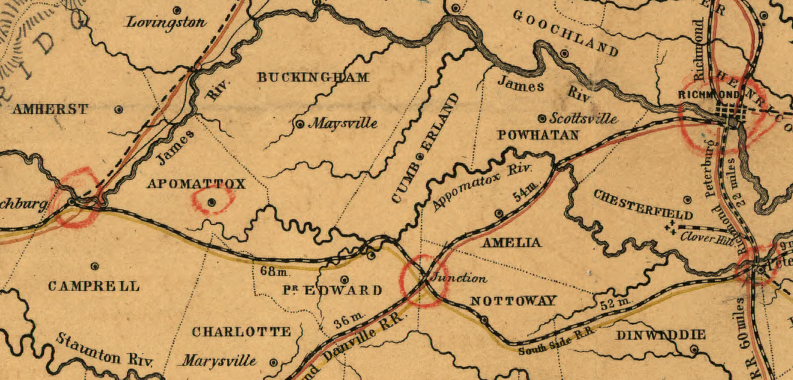

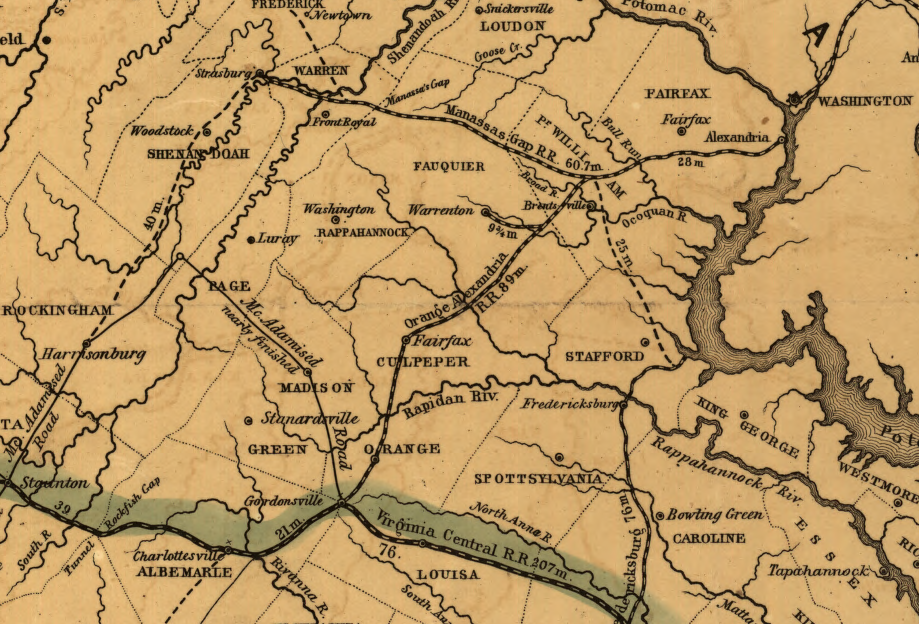

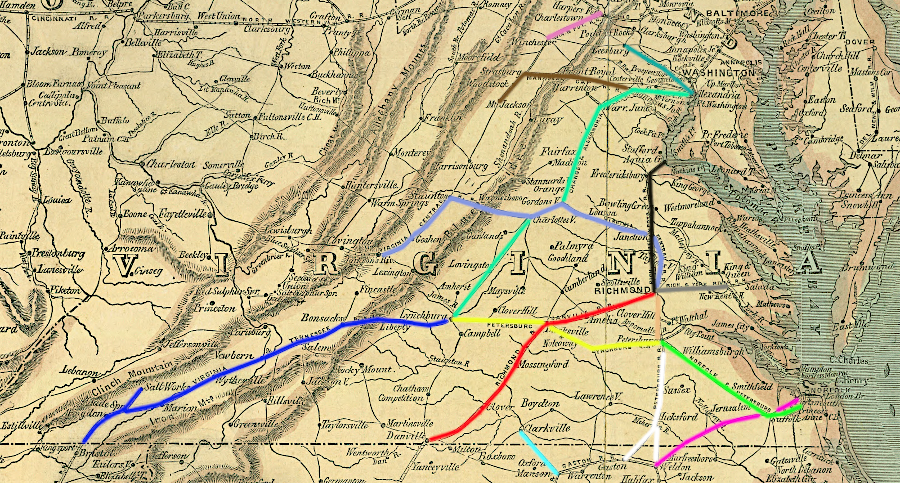

railroads in Virginia, 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the seat of war (1861)

railroads in Virginia, 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the seat of war (1861)

Railroads were essential for supplying large armies as they moved across Virginia. Soldiers need food in order to march and fight. Horses need food in order to haul wagons loaded with ammunition and to pull cannon into position for artillery batteries. According to one estimate:1

General McClellan used the Richmond and York River Railroad to haul supplies at the start of the Peninsula Campaign

Source: Library of Congress, Savage Station, Va., June 27, 1862

The overt fighting in the Civil War started in 1861, but the foundations for Union victory were laid in the preceding decade. If the war had started in 1850, the ability to provide the necessary supplies that enabled the Union Army to overwhelm the Confederates would have been far more difficult.

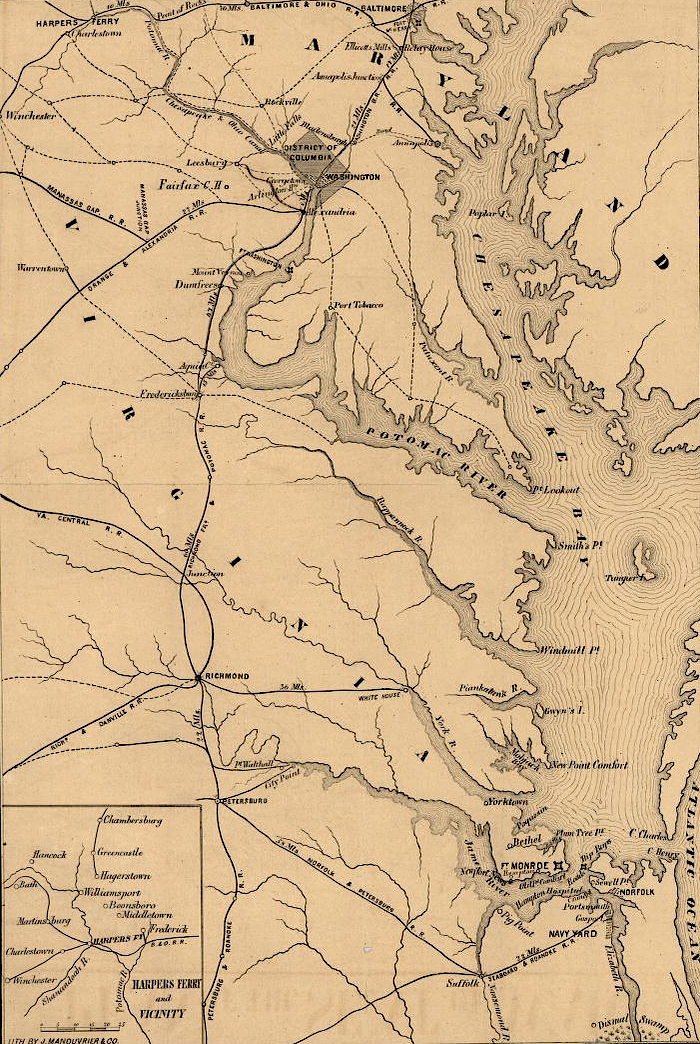

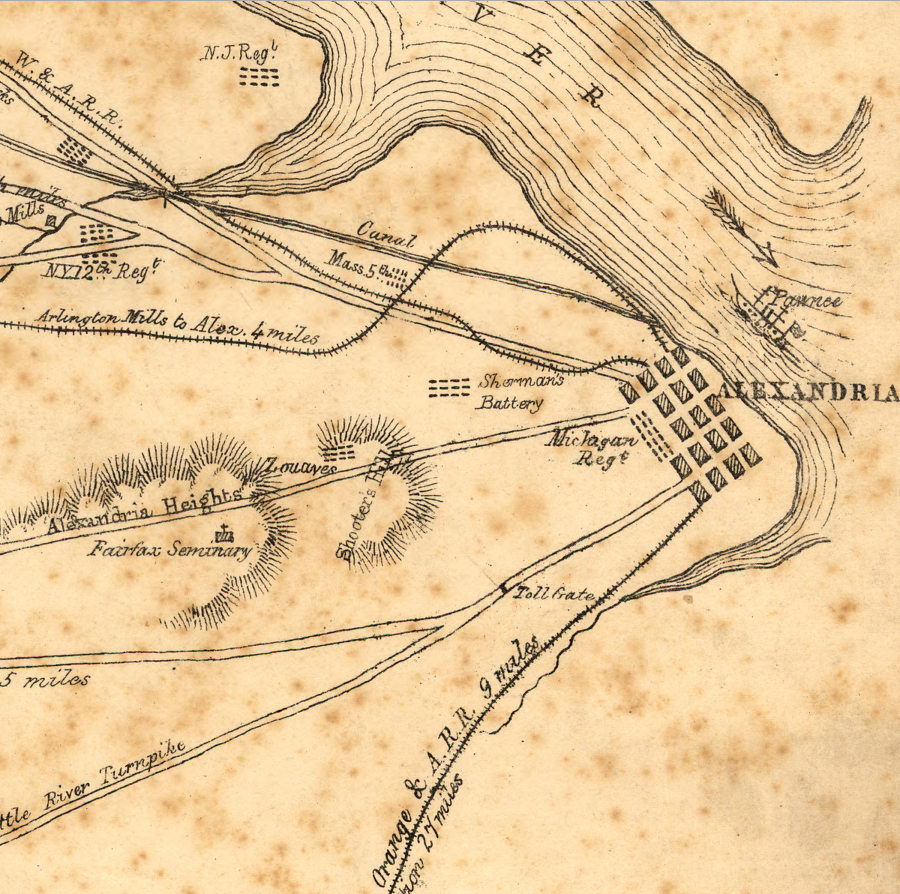

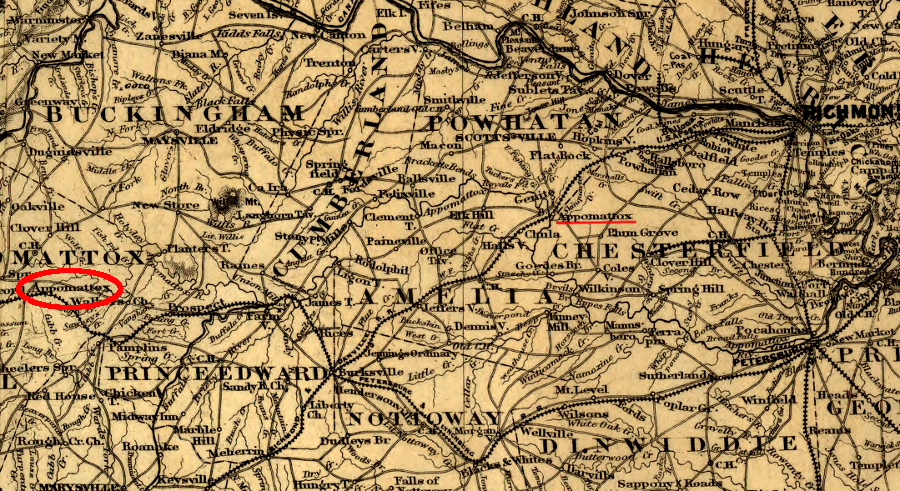

Virginia's railroad network in 1859, prior to the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Railroad map of the eastern, western and northern states, and Canada (1859)

One of the key changes between 1850-1860 was completion of four separate railroad links between the Ohio River/Great Lakes and the northern states. Without the railroads crossing the Appalachians, farmers in the "Northwest" of the 1850's (especially Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio) would have relied upon the Mississippi River to carry crops to market in New Orleans. Development of the steamboat in the 1850's, allowing a two-way trip to haul products back upstream, strengthened the business connections between the southern port and towns up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.

investors built rail lines to connect agricultural regions in the Piedmont and valleys west of the Blue Ridge to port cities in Virginia, so during the Civil War there were few north-south rail lines for the Union army to support armies marching to Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the southern states of North America with the forts, harbours & military positions (1862)

As slavery expanded in the southern states, driven by the economics of cotton agriculture and excused by various moral justifications, New Orleans emerged as the largest city in the south and as the key slave market in North America. Farmers in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio may not have bought their own slaves in order to grow corn/wheat, and social and family bonds to the eastern states would have remained strong - but if those farmers depended upon New Orleans for their living, then the people living in the Northwestern states may have been unwilling to fight and die in a civil war just to maintain a union with marginally-relevant states on the Atlantic coast.2

Those railroads, along with the Erie Canal, created economic ties that shaped the loyalty of the states north of the Ohio River. After 1861, political leaders known as Copperheads tried to get those states to secede, but economic links to the northern states shaped loyalties thanks to the four rail corridors:3

because wood-burning locomotives could transport far more supplies than hay-eating horses, key Civil War campaigns in Virginia were designed to control (or block use of) rail lines

Source: Library of Congress, City Point, Va. Another locomotive at the same point

As described by George Edgar Turner in Victory Rode the Rails, the boundaries of the Union vs. the Confederacy was determined a decade before the war started:4

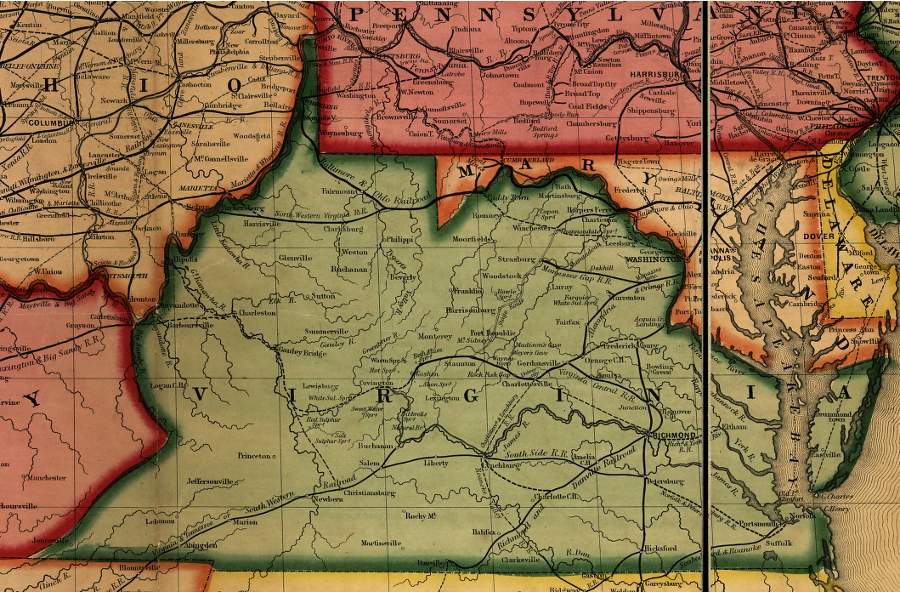

at the start of the Civil War, none of the three railroads in Alexandria had tracks connecting with another railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Sketch of the seat of war in Alexandria & Fairfax Cos. (by V. P. Corbett, 1861)

after 1854, railroads linked the New River/Tennessee River valleys with port cities on the Fall Line of the James River

("Central Depot" at the New River crossing is now the city of Radford)

Source: Library of Congress, Map & profile of the Virginia & Tennessee Rail Road (1856)

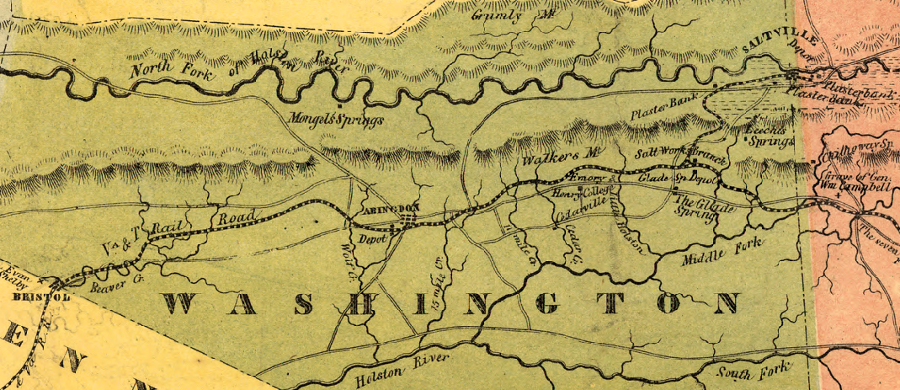

Southwestern Virginia

The loyalty of the counties in southwestern Virginia was affected by the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Until the railroad arrived, the counties in the upper Tennessee River watershed floated most of their crops downriver to market.

Much of the salt from Saltville went down the Holston River to Kingsport and then to Chattanooga, because hauling salt by wagon over the Blue Ridge to the markets at Lynchburg and Petersburg was too expensive. For the same reason, farmers had customers in just a limited area for their wheat or corn, unless the grain was converted into higher-value-for-each-pound-of-weight whiskey. There was little reason to grow tobacco in southwestern Virginia, since all the profits would be consumed by the transportation costs.

once the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad arrived, salt from the Holston River valley could be shipped at much ower coast to customers in the Piedmont and Tidewater

Source: Library of Congress, Map & profile of the Virginia & Tennessee Rail Road (1856)

A Lynchburg and Tennessee Railroad was chartered in 1836, but a recession ("panic") in 1837 stopped it cold. A new charter was approved by the General Assembly in 1847, but state funding for the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was not approved by the General Assembly until 1849, during a time when sectional divisions in the United States were high. Southern politicians in Congress were strongly opposing the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed to limit slavery throughout territory acquired during the war with Mexico that started in 1846.

Fear of national anti-slavery legislation helped Virginia and Tennessee Railroad advocates overcome resistance from rivals who preferred other routes, or wanted to steer all funding to the James River and Kanawha Canal. After all, a new rail link from Lynchburg headed west across the Blue Ridge, connecting at Bristol to another railroad leading to Chattanooga, could serve as a military resource for defense of southern states in case they seceded from the Union.5

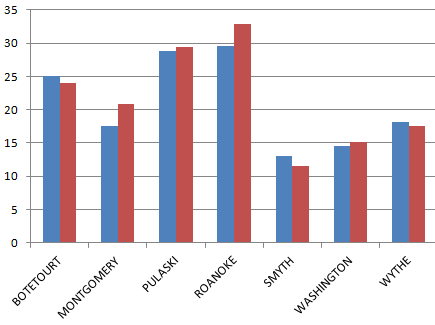

When the railroad reached Bristol, the economy of Southwestern Virginia changed. Farmers in the headwaters of the Tennessee River could shift to staple crops and sell to consumers in Piedmont and Tidewater Virginia. In 1850, Southwest Virginia counties raised only 2 million pounds of tobacco, but in 1860 those same counties grew 124 million pounds - an increase of more than 2,000%. Wheat increased from 1 million to 13 million bushels in that decade. Crops grown in the New River valley could be shipped to Lynchburg at low cost, in boxcars pulled by locomotives over iron rails rather than in two-horsepower wagons on muddy roads.

There was minimal change between 1850-1860 in the percentage of slaves living in the southwestern counties traversed by the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, but the total number of slaves grew substantially in order to grow the tobacco that was exported east across the Blue Ridge. Staple agriculture in the 1850's, in contrast to the 1840's required especially cheap labor.

percentage of slaves in Southwestern Virginia counties did not change significantly between 1850 (blue) vs. 1860 (red), after arrival of railroad

Source: University of Virginia, Historical Census Browser

In the southwestern counties, the bond with slave-dependent eastern Virginia, the philosophical and economic commitment to slavery, increased together with economic dependence upon the "peculiar institution." In contrast, in the 1850's throughout the old agricultural areas of Virginia, where soil fertility had been exhausted by lack of fertilization, slavery declined in the 1850's and many slaveowners sold slaves to meet the growing demand in the cotton-producing states.6

The railroad integrated Southwestern Virginia and Tidewater by creating business ties between the elites who controlled the economic and political decisions in each region. Similarly, the B&O integrated the economy and political perspectives in Virginia's northwestern counties with Pennsylvania, Maryland, and the northern states. As Kenneth W. Noe put it in Southwest Virginia's Railroad: Modernization and the Sectional Crisis:7

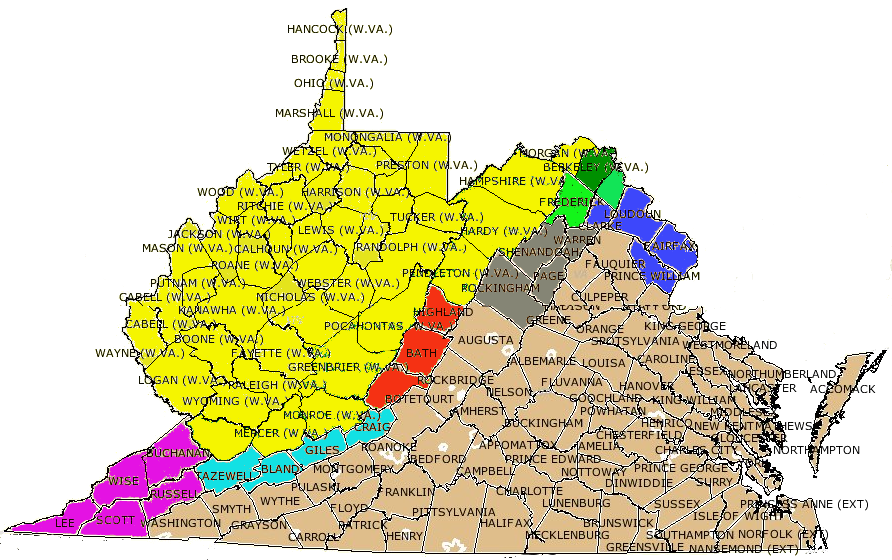

the Restored Government of Virginia legislature authorized several districts to vote for annexation to the new state on May 28, 1863, but no vote was held in Southwestern Virginia

Map Source: Newberry Library, Virginia Historical Counties

When Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, the northwestern counties of the state organized the "Restored Government of Virginia" and ultimately the new state of West Virginia. Debates over the new state's borders included proposals to include the southwestern counties into West Virginia. The counties through which the railroad passed were excluded, because their economic integration with Virginia's eastern counties and public support for slavery was too great.

Because the Southwest Virginia counties stayed in Virginia and the Confederacy, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad became part of the rail corridor linking the eastern and western theaters during the Civil War. The railroad shipped supplies from Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee to the Confederate armies fighting in Virginia, until Knoxville was captured by the Union in 1863. Union initiatives tried to cut that rail line in Virginia several times. In 1864, after the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain, the railroad bridge at Central Depot (now Radford) was burned. When Union cavalry destroyed the track in Wytheville in 1865, there were few resources in Southwestern Virginia to transport to the Confederate army entrenched at Petersburg.

in 1861, the only rail link leading south from Alexandria was via Manassas

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of Virginia between Washington and Manassas Junction (1861?)

Confederate and state officials prioritized production of munitions and ironclad warships, at the expense of producing rail and locomotives to support transportation of supplies. Heavy use of lines in 1861-1865 required replacing equipment and repairing track, but the railroads lacked the needed material and equipment required to provide efficient operations.

The president of the Petersburg Railroad noted in 1863 that locomotives and cars of that line had been transferred to other lines and, in some cases, destroyed or captured by Union forces. He reported in 1863 that the Petersburg Railroad's locomotives could pull only 2/3 the number of cars prior to the war, and:8

General Robert E. Lee asked the Secretary of War to help repair the Virginia Central Railroad in 1863, to enhance delivery of supplies to the Army of Northern Virginia. He was told in the reply letter:9

In 1863, before the Union Army managed to seize or destroy a significant percentage of track outside of the Manassas/Alexandria area, no Virginia railroad was operating more than two trains a day in each direction:10

|

Richmond & Danville Railroad Passenger trains (daily, each way) - 1.5 Freight trains (daily, each way) - 1 Tons of freight (daily, each way) - 100 tons |

South Side Railroad Passenger trains (daily, each way) - 1 Freight trains (daily, each way) - 1 Tons of freight (daily, each way) - 125 tons |

Virginia & Tennessee Railroad Passenger trains (daily, each way) - 1 Freight trains (daily, each way) - 2 Tons of freight (daily, each way) - 240 tons |

Richmond & Petersburg Railroad Passenger trains (daily, each way) - 2 Freight trains (daily, each way) - 2 Tons of freight (daily, each way) - 225 tons |

|

Petersburg Railroad |

Orange & Alexandria Railroad |

Virginia Central Railroad |

Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad |

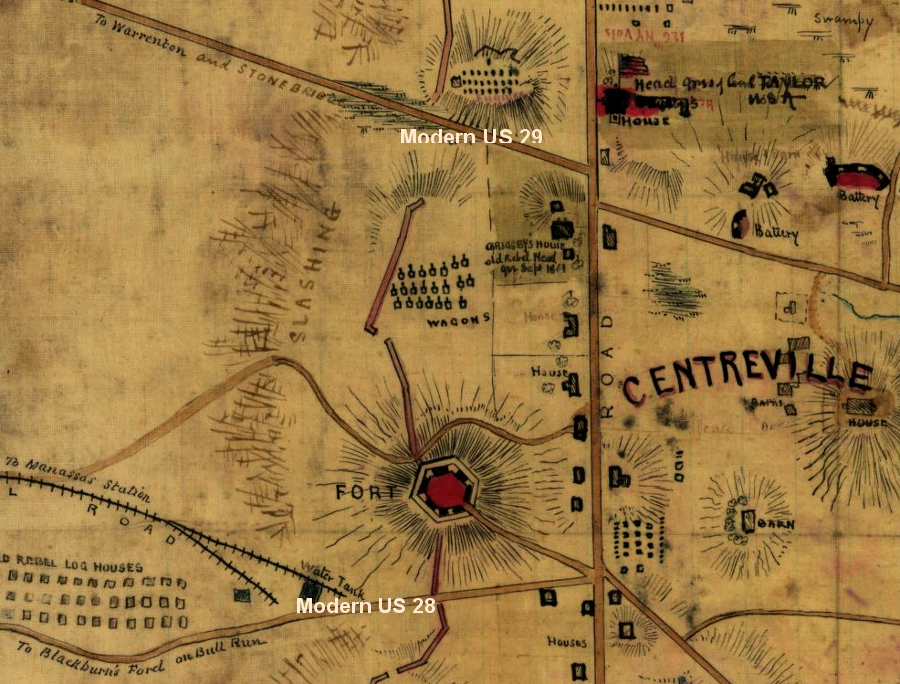

Manassas

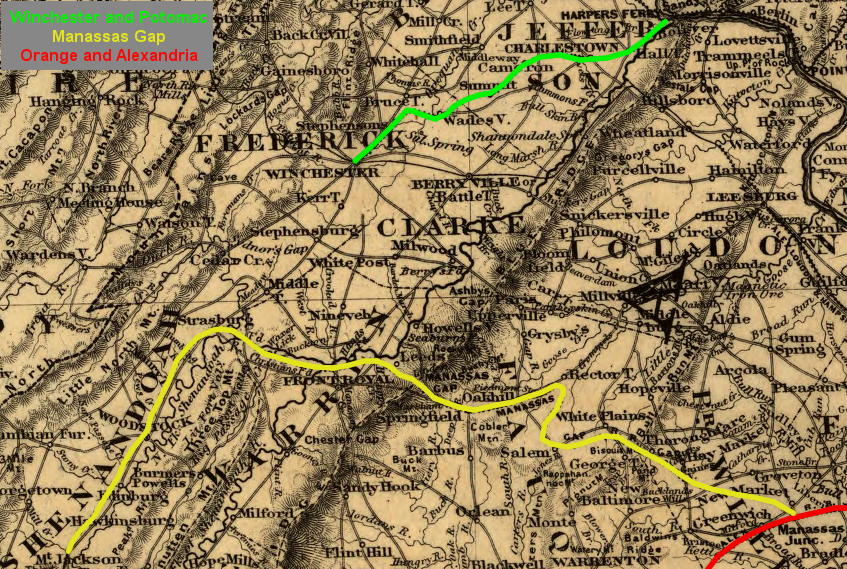

The Civil War is often described as the first railroad war, starting with the Confederate decision to fortify Manassas and the Union decision to march "on to Richmond" through Manassas (rather than marching due south from Washington DC down the modern I-95 corridor). The Confederates established their line of defense in northern Virginia at Manassas. The Orange and Alexandria (O&A) railroad could bring supplies and troops to that point from the Deep South via Lynchburg, or from Richmond via the connection with the Virginia Central railroad at Gordonsville.

In addition, the Manassas Gap Railroad connected through the Blue Ridge, via Thoroughfare Gap and Manassas Gap, to the Shenandoah Valley. The railroad allowed the forces concentrated at Manassas to provide reinforcements if the Union moved south in the Shenandoah Valley.

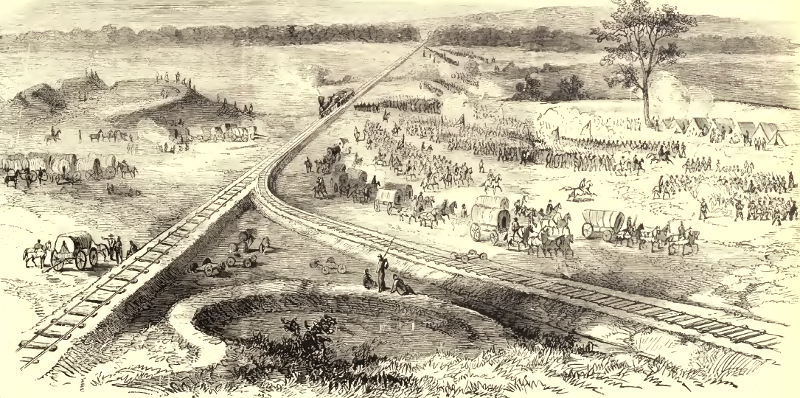

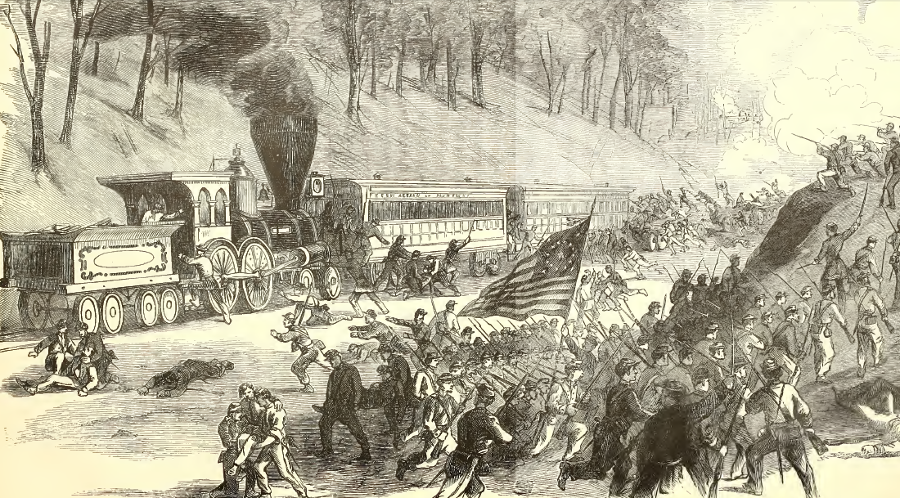

General Hooker's army marches past Manassas Junction, June 1863

Source: Frank Leslie's Illustrated History of the Civil War (p.471)

In the end, Confederate reinforcements went the other direction in July, 1861. Confederates fooled Union General Patterson into thinking nothing was happening near Winchester, then marched across the Blue Ridge at Ashby Gap (modern Route 50). Trains carried General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of the Shenandoah infantry from Piedmont Station (modern Delaplane in Fauquier County) to Manassas, where the reinforcements played a decisive role in the Confederate victory.11

The region around Manassas could not provide enough food for the Confederate troops concentrated there. The Orange and Alexandria connected at Gordonsville to the Virginia Central, which ran to Richmond. Supplies from south of the James River came to Manassas via those two railroads.

The Manassas Gap railroad allowed Confederates to ship supplies from the Shenandoah Valley, which became the "Breadbasket of the Confederacy" due to the high productivity of its wheat farms. The railroad shipped so much beef to supply the army at Manassas that a later historian labelled it the "Meat Line of the Confederacy."12

the Manassas Gap Railroad crossed the Blue Ridge, from Thoroughfare Gap on the eastern flank (shown here) to Manassas Gap on the western edge

Source: Frank Leslie's Illustrated History of the Civil War (p.283)

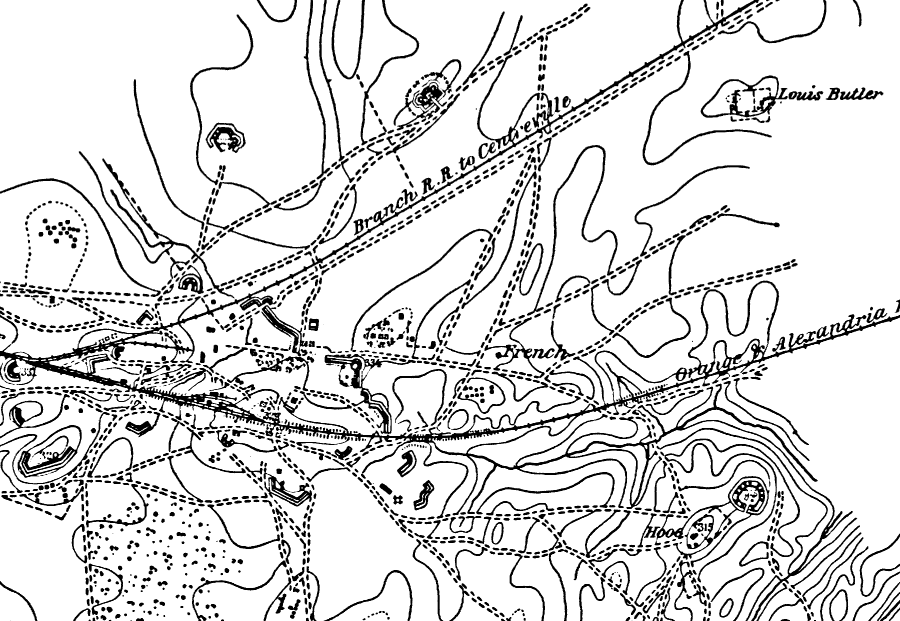

The Confederate army's 1861-62 winter encampment was at Centreville. The Centreville Military Railroad was built from Manassas, across Bull Run, to get supplies to the troops stationed in the front line fortifications.

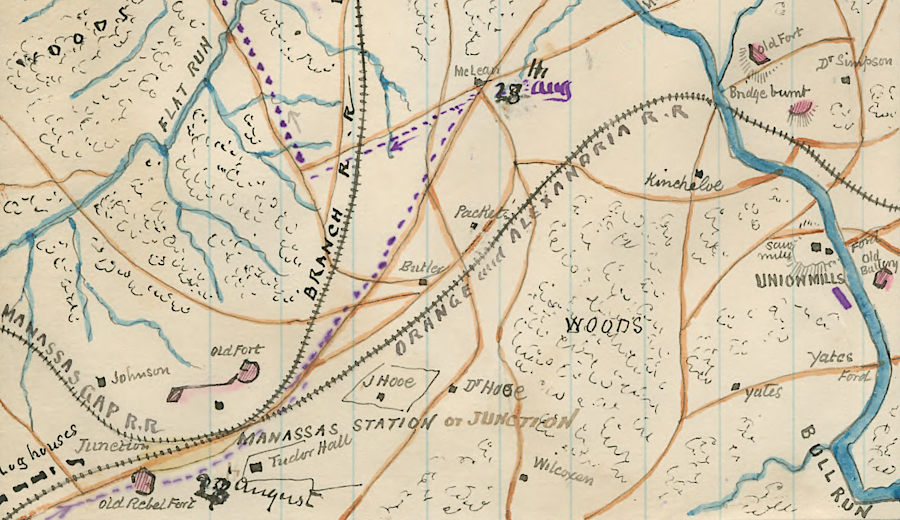

in 1861, Manassas Junction emerged as the major railroad depot for supplying the Confederate Army in Northern Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Route from Manassas to Centreville, August 28th to 31st (by Robert Knox Sneden, 1862-1865)

After the Confederates withdrew from their defense line at Manassas in March, 1862, the massive meat storage depot at Thoroughfare Gap was burned. The Union army repaired the railroad line and supplied troops that occupied the area throughout the summer, especially forces based on the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers. After the Peninsula Campaign, General Lee moved the Confederate army westward past the Union army, passing through Thoroughfare Gap and burning the supply depot at Manassas.

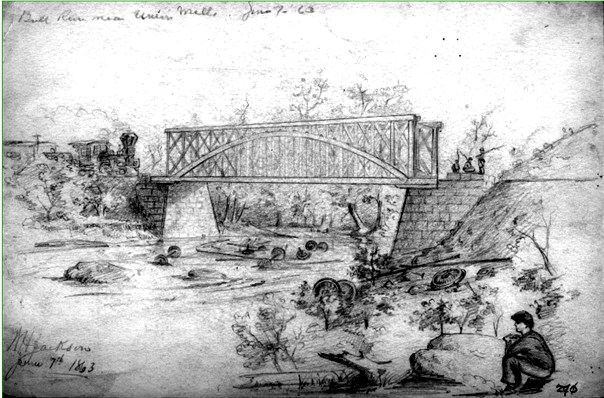

the Orange and Alexandria Railroad bridge across Bull Run was rebuilt by the Union

Source: Bull Run Civil War Round Table, The Sketch Artist of the McLean's Ford Redoubt (August/September, 2017)

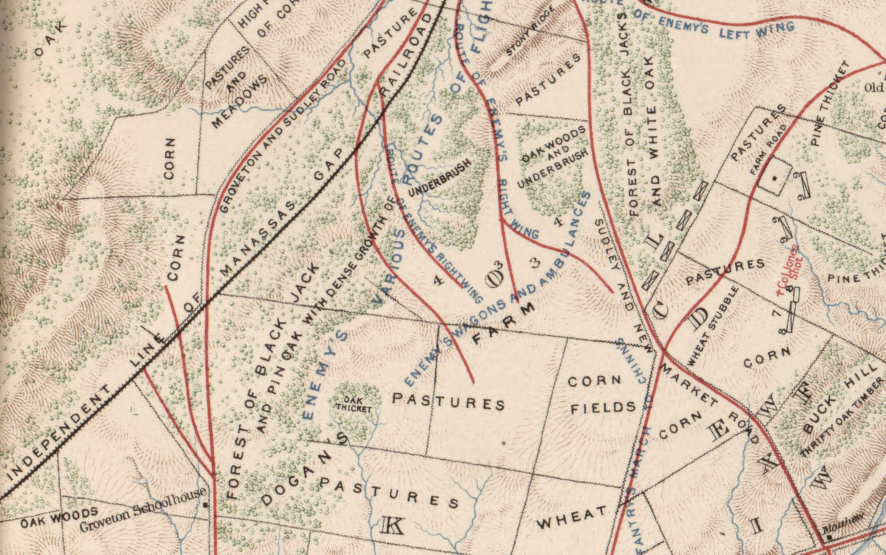

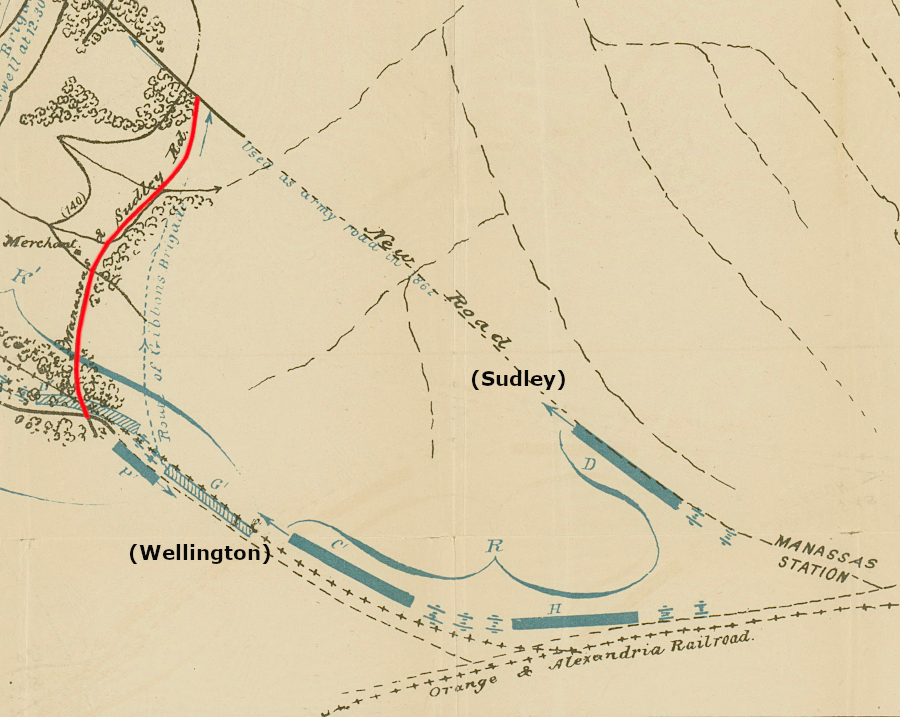

The Second Battle of Manassas soon followed. Troop movements by railroad were not a significant element in that fight, but the unfinished line of the Manassas Gap railroad became a focal point of the battle. Stonewall Jackson's troops held the line there, and used the raised bed at Deep Cut for protection. Jackson's resistance along the "Independent Line" of the railroad provided time for General Longstreet to organize his army south of the Alexandria-Warrenton Turnpike, then attack and win a major Confederate victory on August 30, 1862.

the unfinished line of the Manassas Gap railroad was a key topographical feature used by Stonewall Jackson's forces to align troops and fight off Union attacks during the Second Battle of Manassas on September 29-30, 1862

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, Battle fields of Bull Run and Manassas, Va. (1892)

The Orange and Alexandria became a key transportation tool for Union armies that were based in Fauquier and Culpeper counties during the winters on 1862-63 and 1863-64, but the Manassas Gap railroad was of minimal military value to either side until October 1864.

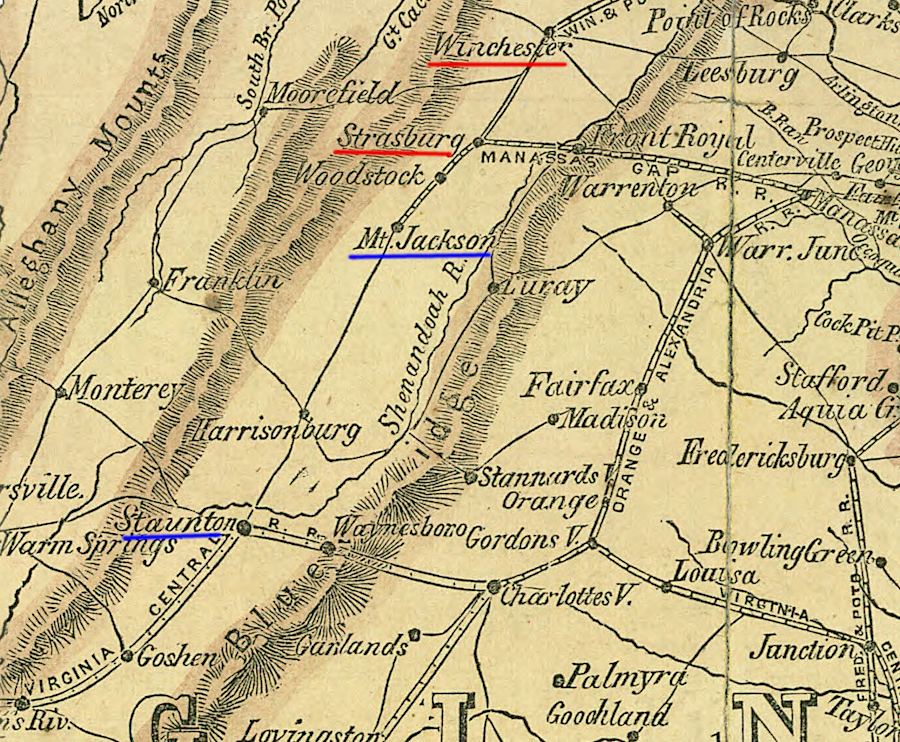

the gap in railroad connections between Winchester-Strasburg, and partisan raids on the Manassas Gap and Orange and Alexandria railroads, blocked the Union from occupying most of the Shenandoah Valley except for short periods of time

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road of Virginia (1869)

Civil War soldiers blocked rail transport by ripping up rails, then using ties and trees to heat and bend the rails to block quick reinstallation

Source: Library of Congress, Tracks of the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, destroyed by the Confederates between Bristow Station and the Rappahannock (1863)

the Confederates built a military railroad in 1861 from Manassas to Centreville

Source: National Park Service, Manassas Junction and Vicinity

in August, 1862, Union forces marched via what is now Rixlew Lane (red line) between modern Wellington and Sudley roads to the Second Manassas battle

Source: National Archives, Map of the Battlegrounds in the Vicinity of Groveton near Manassas

Shenandoah Valley

in 2018, the Manassas Gap Railroad (part of Norfolk Southern) ran parallel to Interstate 66 towards Thoroughfare Gap

Source: Historic Prince William, I-66 west of Haymarket - #279

During the Civil War, there was no railroad line running through the entire Shenandoah Valley. The Winchester and Potomac Railroad linked Harpers Ferry-Winchester, but there was a gap between Winchester-Strasburg. The Manassas Gap Railroad connected Front Royal-Mount Jackson, but there was no line south of there until reaching the Virginia Central at Staunton. No track connected the Virginia Central to the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad west of the Blue Ridge.

The Confederates in the southern half of the Shenandoah Valley had to be supplied by local resources, or by carting supplies in wagons north from Lexington and Staunton. Union forces had to rely upon wagon trains to bring supplies south of Winchester, and Confederate partisans under John Singleton Mosby raided the supply line often enough to affect Union strategy. The Union considered using the Orange and Alexandria Railroad to carry supplies to Manassas and then the Manassas Gap Railroad to get across the Blue Ridge, but that supply line ran through the heart of Mosby's territory.

In September 1864, as part of the Union campaign to block Shenandoah Valley supplies from reaching the Army of Northern Virginia entrenched at Petersburg, General Philip Sheridan raided "up" the Shenandoah Valley to Staunton. Though Sheridan burned many barns and mills in the 1864 Valley Campaign, the Union Army did not destroy the Virginia Central Railroad at Staunton or cross the Blue Ridge and block the railroad at Gordonsville until 1865.

General Jubal Early's Confederate Army in the Shenandoah Valley was defeated at Cedar Creek in October, 1864,and then withdrew south to Staunton. The Union Army considered setting up a base in Front Royal to support an occupying force during the winter of 1864-65. The initial plan was to keep steady pressure on the Shenandoah Valley and the Piedmont east of the Blue Ridge, using the Manassas Gap Railroad to ship supplies and troops across the mountains as needed.

However, John Singleton Mosby's partisan rangers were effective in attacking US Military Railroad shipments in Northern Virginia. General Sheridan could not ensure a steady source of hay for horses or supplies for troops. Even burning all houses within five miles of the Manassas Gap Railroad was not sufficient to make use of that railroad reliable, so the Union shifted military strategy and sent Sheridan and his cavalry to Petersburg. The Winchester and Potomac Railroad, which had been rebuilt for six miles to Halltown before the burning, was rebuilt almost all the way to Winchester in November, 1864 to support the occupation forces during the winter.13

during the Civil War, the railroad network in Northern Virginia connected Alexandria to Mt. Jackson, and the route to Richmond required going through Manassas

Source: Library of Congress, Map of eastern Virginia (1862)

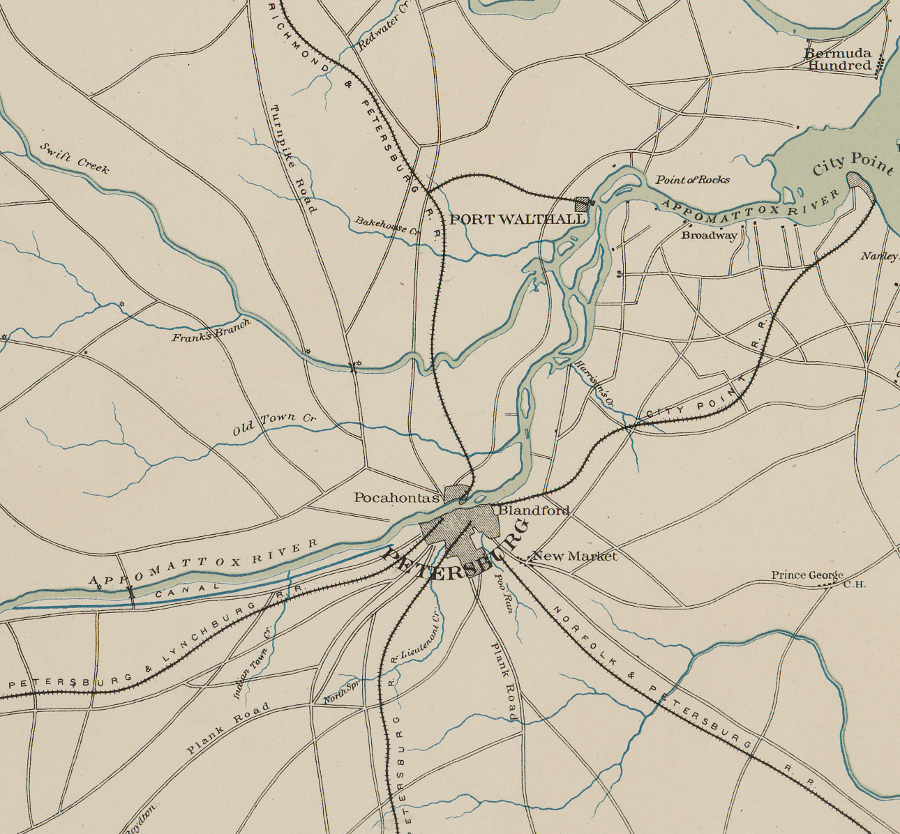

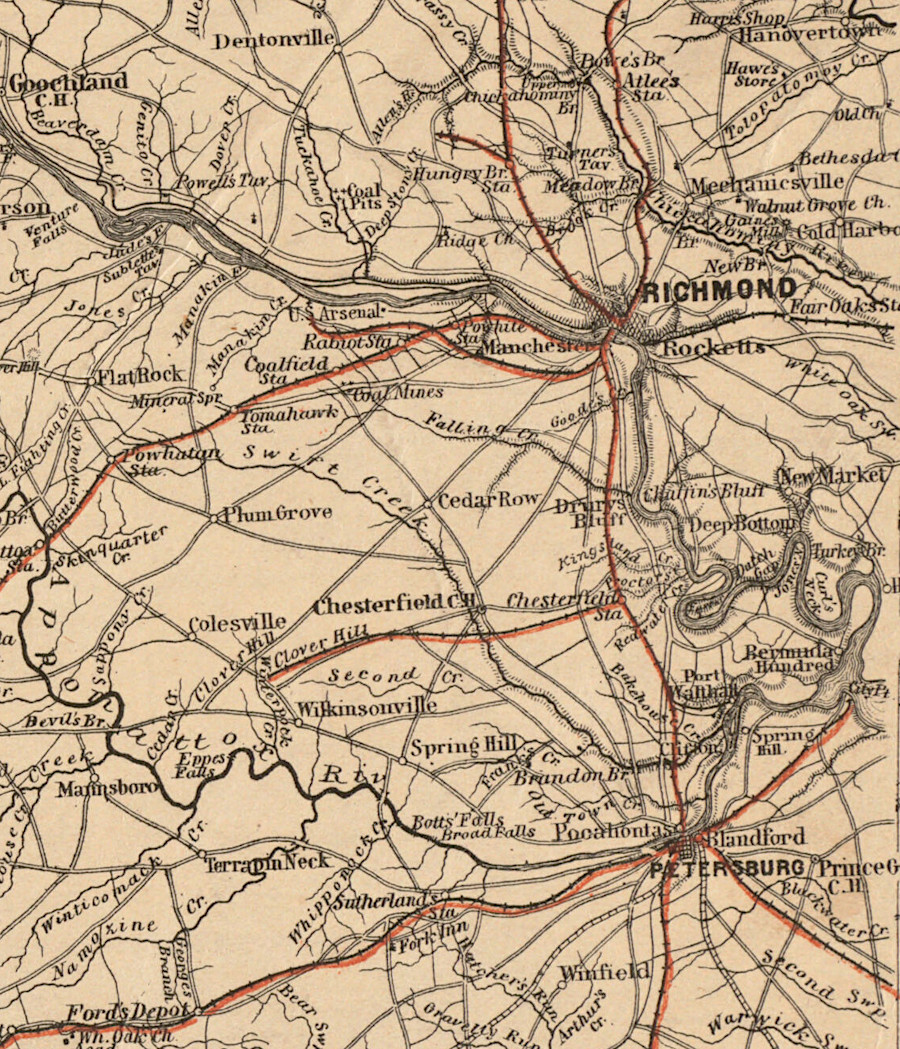

Petersburg

five railroads connected with Petersburg prior to the Civil War

Source: US War Department, Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Southeastern Virginia and Fort Monroe Showing the Approaches to Richmond and Petersburg (1862)

Only three major Union campaigns were conducted without relying upon railroads to supply the northern armies. Gen. George McClellan relied upon shipping to supply his Peninsula campaign in 1862. In 1864, Gen. William T. Sherman abandoned his long supply line and marched from Atlanta to Savannah without rail support. Also in 1864, Federal resources were finally sufficient for General Ulysses S. Grant to conduct his Overland Campaign, from the Rappahannock to the James rivers, without rail support. In contrast to 1861, Grant's "On to Richmond" march in 1864 did not require use of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad to Gordonsville and the Virginia Central Railroad south of that point to Richmond.

Grant's campaign in 1864 stalled outside of Richmond, and he spent nine months trying to capture... Petersburg.

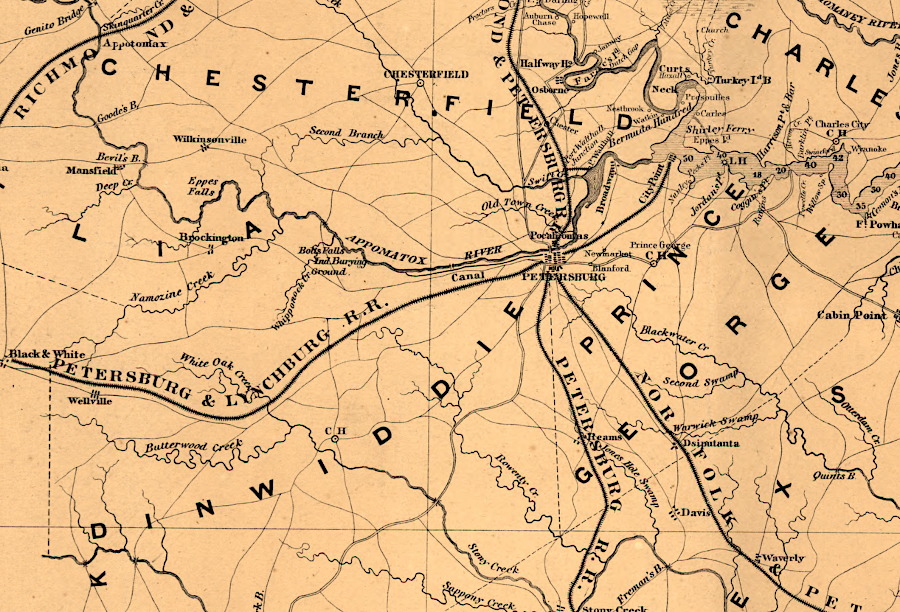

Why Petersburg, instead of the capital of the Confederacy at Richmond? Petersburg was the railroad hub of Central Virginia. Essential supplies and reinforcements reached Richmond from the south through Petersburg. Without supplies shipped via railroad through Petersburg, the Confederate government could not survive in Richmond.

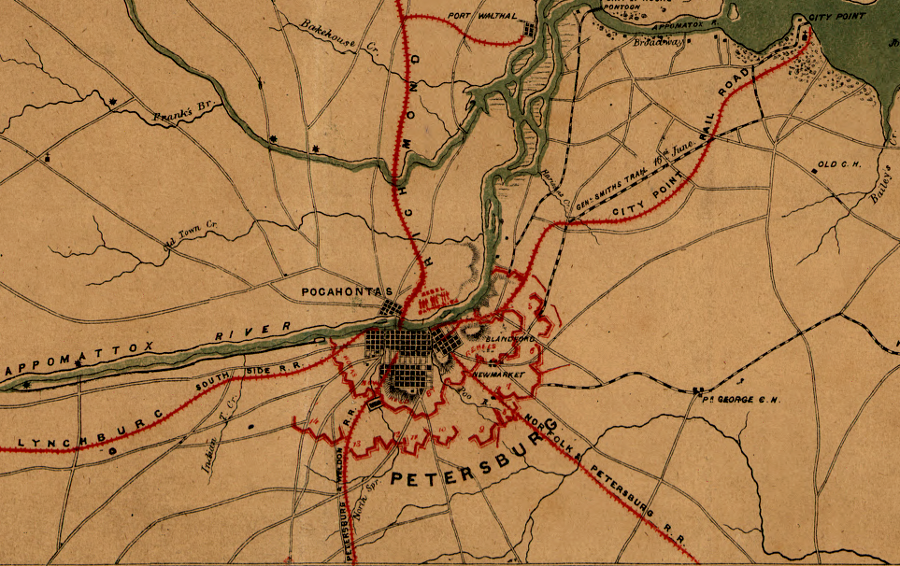

five railroads converged on Petersburg, and blocking supplies flowing through Petersburg ultimately forced the Confederates to evacuate Richmond in April 1865

Source: Library of Congress, Military topographical map of eastern Virginia

General Lee fought for months to defend his supply line. During the siege of Petersburg, General Grant used his superior resources to gradually extend his lines south and west to encircle Petersburg. He first cut the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad, then the Petersburg and Roanoke Railroad to block the Confederates from receiving supplies by rail from the supply depot at Weldon, North Carolina.

Grant's forces gradually moved to encircle Petersburg, and finally seized control of the South Side Railroad in the battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865. At that point, with no remaining railroad connection, Lee abandoned Petersburg and the Confederate government abandoned Richmond.

The Union Army's direct frontal attacks on Richmond failed in 1862 and 1864, but succeeded when General Grant swung south of the James River and cut off the capital's supplies brought via Petersburg's railroad network. Jefferson Davis, with the Confederate gold, fled south on the Richmond and Danville Railroad. He took the last trains to leave the Richmond station before the Union cavalry cut that line as well.

the 1864-65 Siege of Petersburg was designed to cut the transfer of supplies via railroad

Source: Library of Congress, E. & G. W. Blunt's corrected map of the seat of war near Richmond, July 10th, 1862

The Richmond and Danville Railroad tracks and locomotives were so worn out that Jefferson Davis's train averaged only 9mph in its 140-mile, Sunday night flight to Danville.14

On the way, at Burkeville Junction it passed two trains loaded with supplies for Lee's Army at Petersburg. The trains withdrew to Farmville, reducing the risk of Union capture but leaving the Confederate Army short of rations.15

in 1865, the South Side railroad linked Petersburg with Lynchburg and intersected the Richmond and Danville Railroad at Burkeville ("Junction")

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the proposed line of Rail Road connection between tide water Virginia and the Ohio River at Guyandotte, Parkersburg and Wheeling

this 1869 map includes a second Appomattox station, but the famous one was on the South Side railroad and not the Richmond and Danville Railroad in 1865

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Rail Road of Virginia

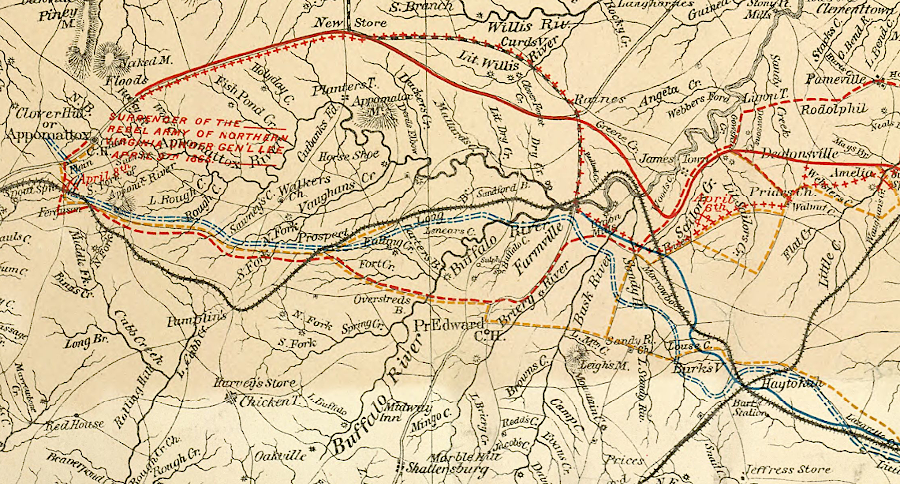

Appomattox

When General Robert E. Lee ordered the Confederate Army to abandon Petersburg, he tried to march southwest in order to join the remnant of the Confederate Army of Tennessee in North Carolina under General Joseph E. Johnston.

Lee was unable to follow the South Side Railroad due west towards Burkeville Junction, before turning south on the Richmond and Danville Railroad Lynchburg. The Union cavalry and infantry units controlled the rail corridor at Sutherland Station on April 2, 1865, after the Battle of Five Forks. Instead, Lee chose to retreat from Petersburg on the opposite (north) side of the Appomattox River, moving west through Chesterfield rather than Dinwiddie county.

Using the Appomattox River as a barrier and moving on dirt roads in Chesterfield County left Lee with limited supply capacity. Lee's wagon train trailed behind the infantry with supplies, but Union cavalry destroyed much of it.

To feed his army, Lee aimed for Amelia Courthouse, He expected to receive reinforcements and food from Richmond via the railroad corridor. His retreating army crossed to the south side of the river into Amelia County at Goodes Bridge (modern Route 360) and near the Genito Bridge upstream, though the bridge itself had been destroyed by high water. To Lee's disappointment, he found ordinance for further fighting at Amelia Court House, but no food for the hungry, tired troops.16

Worse, Lee discovered the Union troops had blocked his route south on the Richmond and Danville Railroad corridor, by building fortifications across the rail line at Jetersville. Lee set off again cross-country, heading west towards Lynchburg and seeking a supply train somewhere on the South Side Railroad. He got to Rice's Depot on the South Side Railroad, though 20% of his army was captured or dissolved on the way at Sailor's Creek and in other engagements.17

Lee then headed west to Farmville, crossing the Appomattox River on High Bridge. Union attacks forced him to move west from Farmville, with Lee paralleling the South Side Railroad until he lost the race to the trainloads of supplies waiting for him at Appomattox Station.

The South Side Railroad had bypassed the county seat in Appomattox County, just as the main line of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad in Northern Virginia bypassed the county seats of Fairfax, Prince William, and Fauquier counties. Key steps that led to Lee's final surrender was the Union capture of the Confederate supply trains at Appomattox Station and blocking his path towards the railroad further west. General Lee recognized he could not feed his troops, abandoned his "not yet" response, and surrendered to General Grant.

the capture of Confederate supply trains at Appomattox Station, a mile from the county courthouse, determined that Lee would have to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Appomattox Court House (1865 Michler map)

the Union Army captured the supplies on the South Side Railroad, then surrounded the Army of Northern Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Central Virginia: showing Lieut. Gen'l. U.S. Grant's campaign and marches of the armies under his command in 1864-5 (US War Department. Engineer Bureau, between 1864 and 1869)

At the end of the Civil War, the US Military Rail Road continued to operate on lines it had seized in order to supply troops still in the field. The US Army gave the Virginia Bureau of Public Works responsibility for managing Virginia railroads, and that board quickly gave each railroad's superintendent the responsibility for repair and restoration of operations.18

Richmond and Petersburg were able to receive troops and supplies through railroads connecting to the rest of the state

Source: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library, Middle Virginia and North Carolina (1864)

a month before the First Battle of Manassas, Confederates ambushed an Alexandria, Loudon and Hampshire Railroad train loaded with Federal soldiers at Vienna

Source: Frank Leslie's Illustrated History of the Civil War, General Schenk, With Four Companies of the First Ohio Regiment, Surprised and Fired Into By a Confederate Masked Battery Near Vienna, VA June 17th 1861 (p.29)

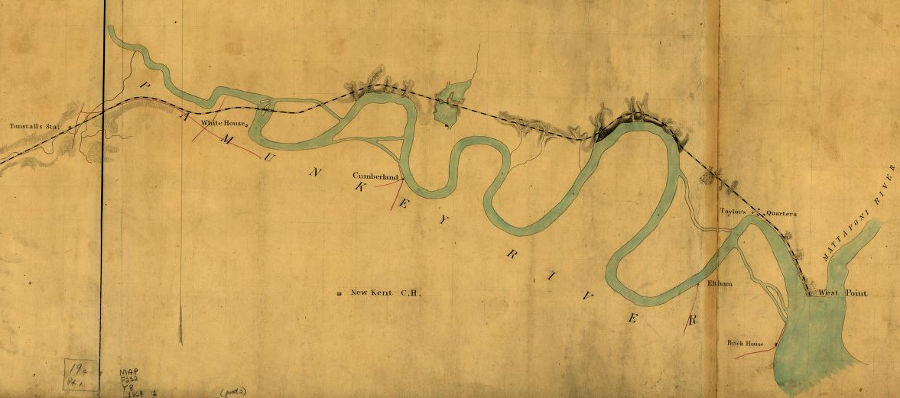

during the Peninsula Campaign, Union forces relied upon the Richmond and York River Railroad to carry supplies from White House Landing to the front and return wounded soldiers, until agressive attacks by General Lee caused General McClellan to change his supply base to the James River and abandon the railroad

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, A Vain Ride to Safety (p.324)

the Richmond and York River Railroad connected Richmond to the deepwater port at West Point, and crossed the Pamunkey River at White House Landing

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond and York River Railroad (1864)

horses had greater flexibility than locomotives to pull wagons on different terrains, including quick bridge replacements

Source: Library of Congress, Wagon train crossing pontoon bridge, Rappahannock River, below Fredericksburg, Va (1864)

1. Bert Dunkerly, "Civil War Railroads: An Overview," Emerging Civil War, October 20, 2018, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/10/20/civil-war-railroads-an-overview/ (last checked December 11, 2023)

2. George Edgar Turner, Victory Rode the Rails, University of Nebraska Press, 1992, pp.21-23, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/FpINOwAACAAJ (last checked December 11, 2023)

3. George Edgar Turner, Victory Rode the Rails, pp.24-28, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/FpINOwAACAAJ (last checked December 11, 2023)

4. George Edgar Turner, Victory Rode the Rails, p.27, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/FpINOwAACAAJ (last checked December 11, 2023)

5. Kenneth W. Noe, Southwest Virginia's Railroad: Modernization and the Sectional Crisis, University of Illinois Press, 1994, pp.17-24

6. Kenneth W. Noe, "'A Source of Great Economy?' The Railroad and Slavery's Expansion in Southwest Virginia 1850-1860," in Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation, John C. Insco (editor), University Press of Kentucky, 2005, p.103, http://books.google.com/books?id=hea586e-L0QC (last checked August 17, 2013)

7. Kenneth W. Noe, Southwest Virginia's Railroad: Modernization and the Sectional Crisis, pp.7-8

8. letter to Wm. T. Joyner Esq. (Petersburg Railroad president), April 4 1863, in Confederate Railroads, http://www.csa-railroads.com/Essays/Orignial%20Docs/NA/NA,_SWR_4-4-63.htm (last checked August 19, 2020)

9. Letter from James A. Seddon to General R. E. Lee, April 1, 1863, in Confederate Railroads, http://www.csa-railroads.com/Essays/Orignial%20Docs/OR/OR%20Series%201,%20Vol.%2051,%20Part%202,%20Page%20690.htm (last checked August 19, 2020)

10. Letter from William M. Wadley to James A. Seddon, April 15, 1863, in Confederate Railroads, http://www.csa-railroads.com/Essays/Orignial%20Docs/OR/OR%20Series%204,%20Vol.%202,%20Page%20487.htm (last checked August 19, 2020)

11. Joseph Mills Hanson, Bull Run Remembers, National Capitol Publishers, 1957, p.27

12. Michael P. Gray, "Manassas Gap Railroad During the Civil War," Encyclopedia Virginia, 2011, http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Manassas_Gap_Railroad_During_the_Civil_War (last checked August 17, 2013)

13. Virgil Carrington Jones, Gray Ghosts and Rebel Raiders, EPM Publications, 1984, pp.295-302; Daniel C. McCallum, "United States Military Railroads Report," Government Printing Office, 1866, p.6, p.9, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL24992627M/Reports_of_Bvt._Brig._Gen._D._C._McCallum_Director_and_General_Manager_of_the_Military_Railroads_of_ (last checked April 11, 2020)

14. James C. Clark, Last Train South: The Flight of the Confederate Government from Richmond, McFarland & Company, 1985, p.25, http://books.google.com/books?id=mYe9tOESL0kC (last checked August 27, 2013)

15. William Marvel, Lee's Last Retreat: The Flight to Appomattox, University of North Carolina Press, 2002, p.522, http://uncpress.unc.edu/browse/page/522 (last checked August 27, 2013)

16. "Powhatan and the Civil War," Powhatan County website, http://www.powhatanva.com/civilwar/train.htm (last checked August 27, 2013)

17. "Southside Virginia & Lee's Retreat: Radio Message Scripts," Civil War Traveler, http://www.civilwartraveler.com/EAST/VA/va-southside/LR-RadioScripts.html (last checked August 27, 2013)

18. Charles W. Turner, "The Virginia Southwestern Railroad System At War, 1861-1865," The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, Number 71 (November 1947), p.75, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23515299 (last checked May 15, 2020)

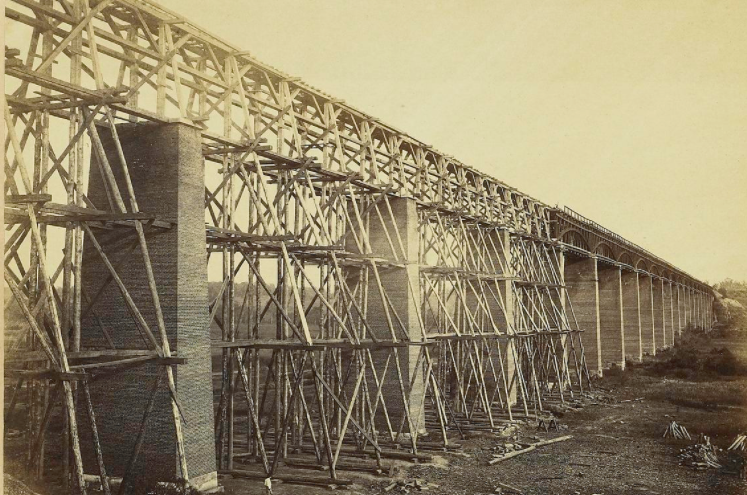

Federal troops burned the York River Railroad bridge across the Pamunkey River in 1862, during the "change of base" from White House Landing in New Kent County to Harrison's Landing at Berkeley Plantation

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, the Waste of War (p.316)

in the winter of 1861-62, Confederates built a military railroad to support the camp at Centreville

Source: Library of Congress, New defenses erected at Centreville, Virginia (1863) by Robert Knox Sneden

railroads in Northern Virginia, 1852

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant

railroad depots as well as tracks had to be rebuilt after the Civil War, while new locomotives, cars, and maintenance equipment had to be purchased

Source: Library of Congress, Canal and ruins of Richmond and Danville Railroad Depot, Richmond, Va., April, 1865

the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad bridge over the James River was burned by Confederates on the evening of April 3, 1865 after Richmond was evacuated

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Plate 88. Ruins of Richmond and Petersburg Railroad, Across the James (Gardner's Photographic Sketchbook of the War, Vol. II)

the South Side Railroad crossed the Appomattox River on the High Bridge

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Plate 98. High Bridge, across the Appomattox (Gardner's Photographic Sketchbook of the War, Vol. II)

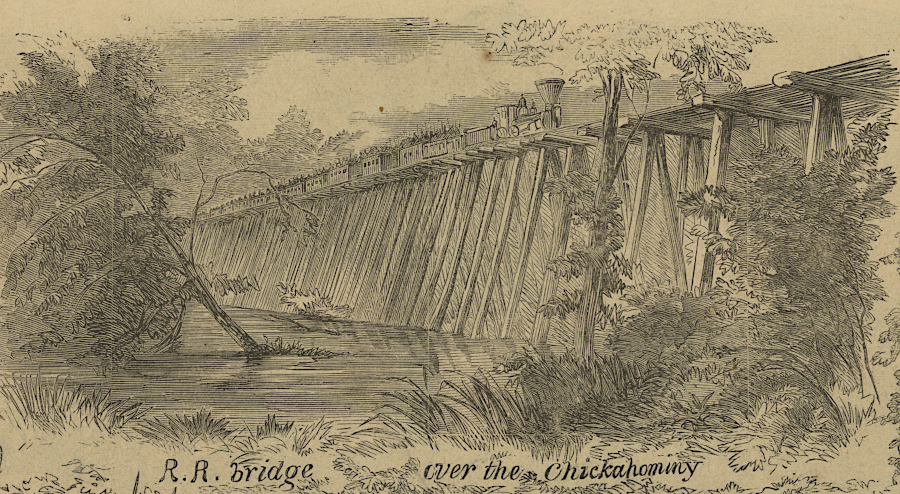

York River Railroad bridge over the Chickahominy River in March 1862

Source: Library of Congress, Scenes in and about the Army of the Potomac

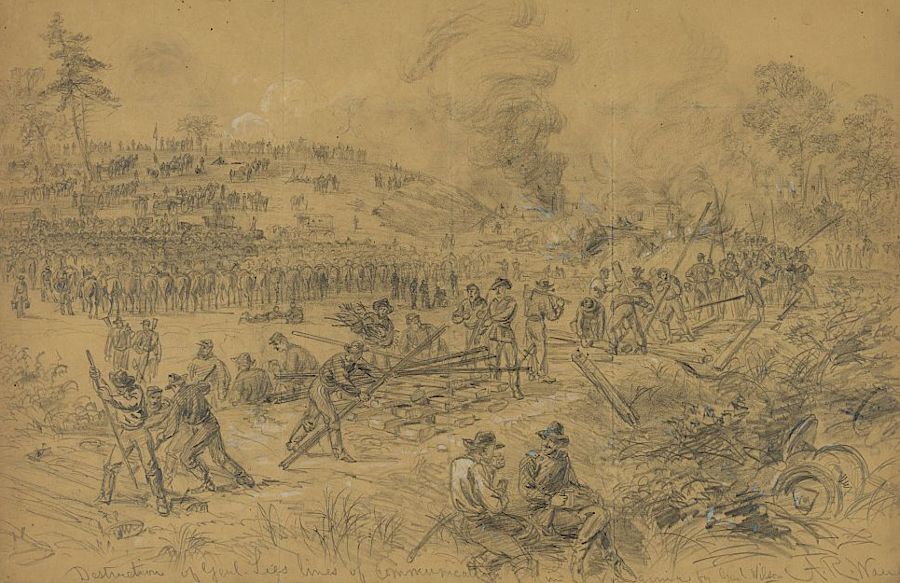

Union cavalry destroyed tracks leading into Petersburg in 1864

Source: Library of Congress, Destruction of Genl. Lees lines of Communication in Virginia by Genl. Wilson (by Alfred R. Waud, 1864)

wooden buildings used by the railroads were easy to destroy during the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Destruction of Water Ta[nk]s & Engines & engine houses for pumping water into them at Jarrets Station (by Alfred R. Waud, 1864)

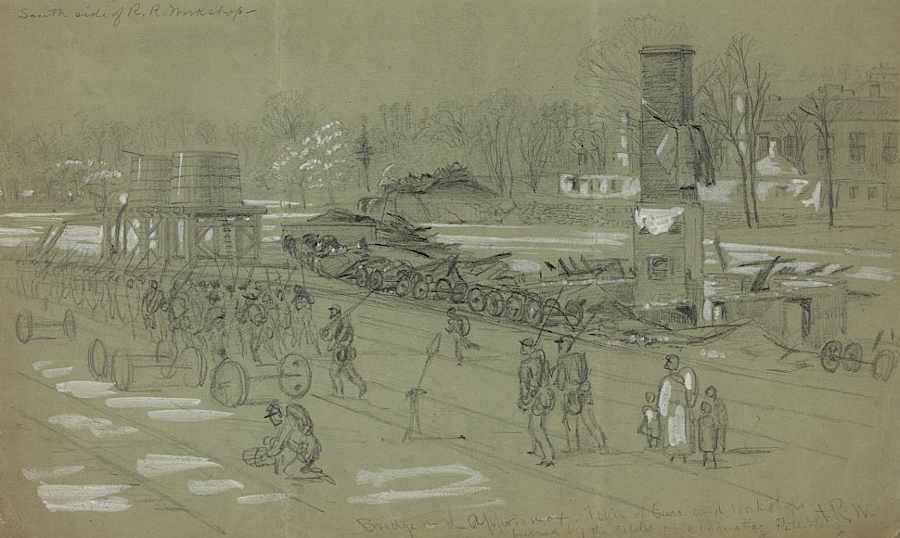

in the last days of the Civil War, Confederates destroyed railroad equipment at Petersburg that would be needed during Reconstruction

Source: Library of Congress, Bridge on the Appotomax [sic]--Train of Cars and workshops burned by the rebels on evacuating Petersburg (by Alfred R. Waud, 1865)

away from railroads, Civil War armies had to dedicate wagons to carry "fuel" for the horses, making it harder to supply the soldiers

Source: Harpers Weekly, The Army of Virginia (August 9, 1862, p.501)

1861 railroad network in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the southern states, including rail roads (Harpers Weekly, 1861)

in 1861, there were gaps in Shenandoah Valely railroad connections between Winchester-Strasburg and Mount Jackson-Staunton

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the southern states, including rail roads (Harpers Weekly, 1861)