South Atlantic and Ohio Railway/Virginia and Southwestern Railroad

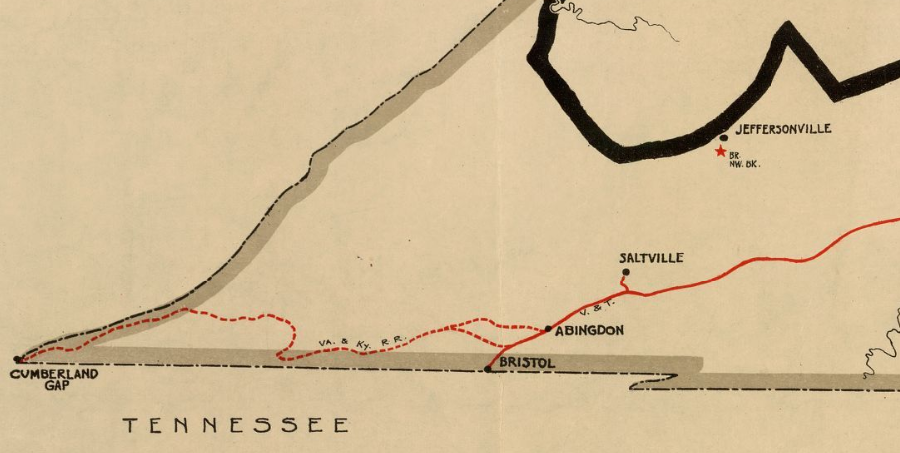

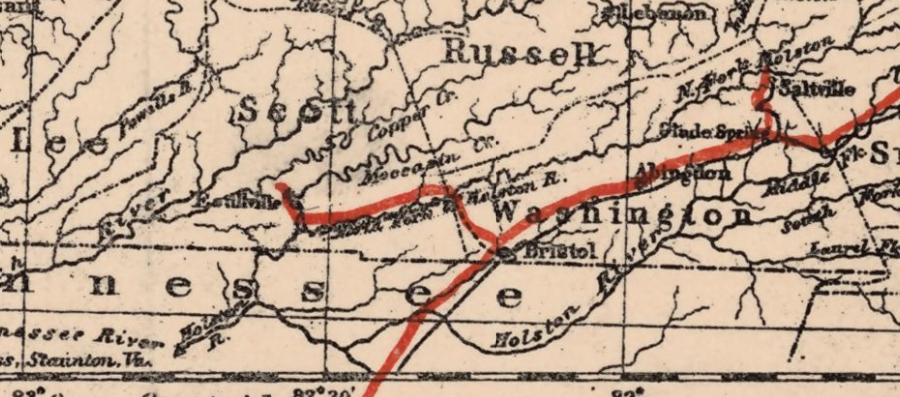

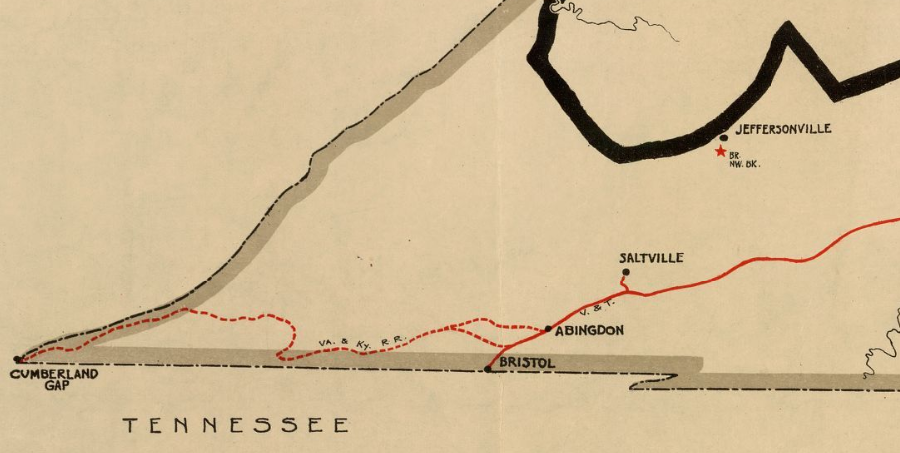

In 1852, the General Assembly authorized both the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad and the Virginia and Kentucky Railroad to build track between the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, west of Abingdon, to Cumberland Gap. The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad Company focused on its existing track between Bristol and Lynchburg, but the Virginia and Kentucky Railroad made some progress preparing a route before the Civil War. It started to connect Bristol (rather than Abingdon) to Cumberland Gap.

the Virginia and Kentucky Railroad had the option of starting from either Abingdon or Bristol

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the location of railroads, canals, navigation projects and public institutions in which the Commonwealth of Virginia had invested money as of date January 1st. 1861

The Virginia and Kentucky Railroad failed to find new financing in the depressed economic conditions after the Civil War. The Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad had the rights to build west to Cumberland Gap between 1870-1874, but could not find the financing required.

When the state legislature chartered the Bristol Coal and Iron Narrow Gauge Railroad in 1876, it transferred to the new company the authorization previously granted to the Virginia and Kentucky Railroad to connect the valley of the Holston River to the far southwestern tip of Virginia.

Two brothers from Southwest Virginia (H. C. Woods and M. B. Woods) tried to finance and build the Bristol Coal and Iron Narrow Gauge Railroad after the Civil War. Their goal was to lay track from the existing railroad at Bristol to Cumberland Gap, then north through that gap into Kentucky. 1

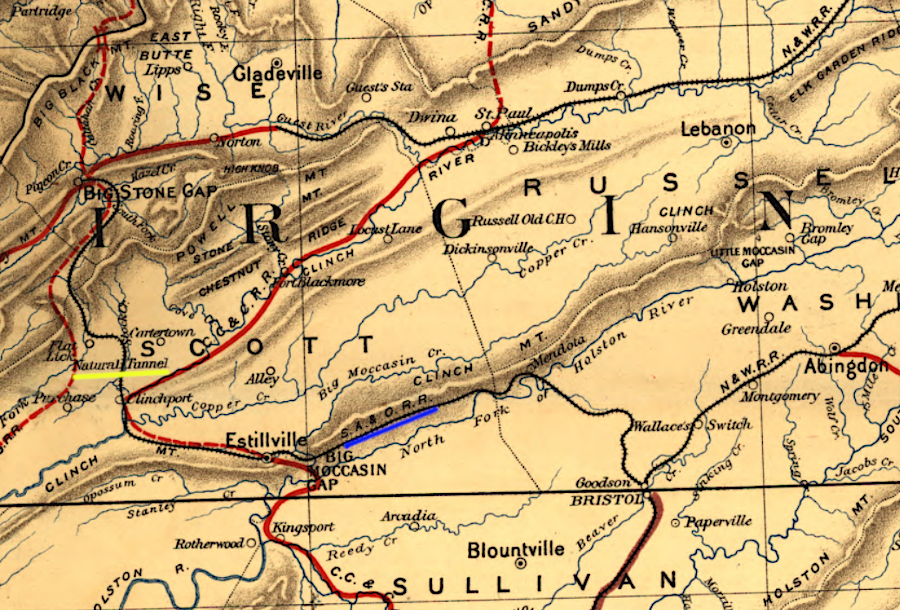

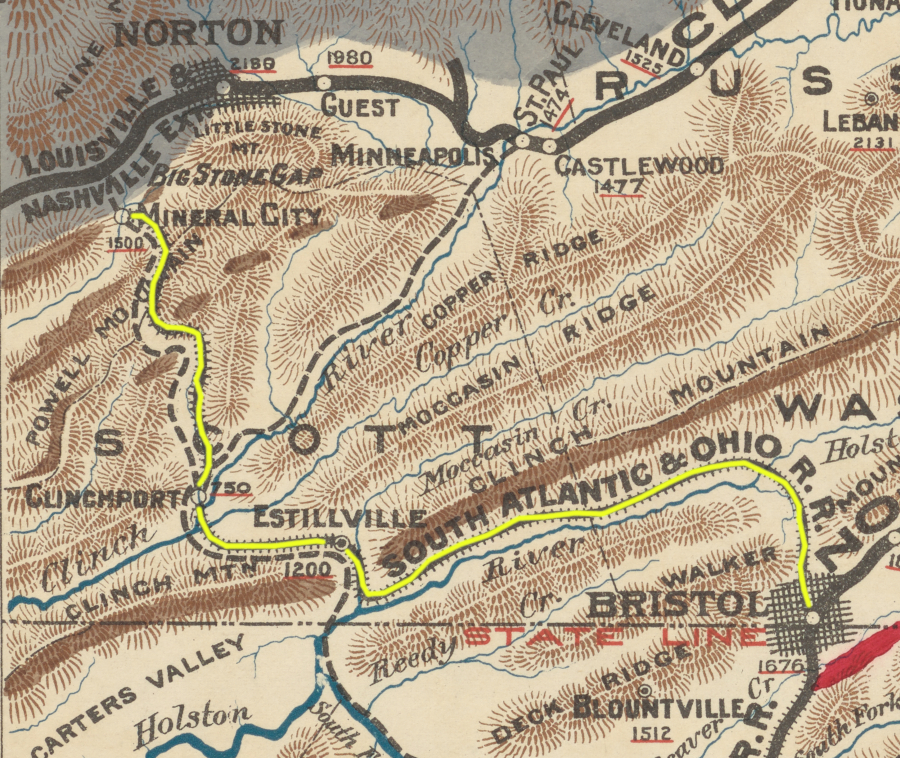

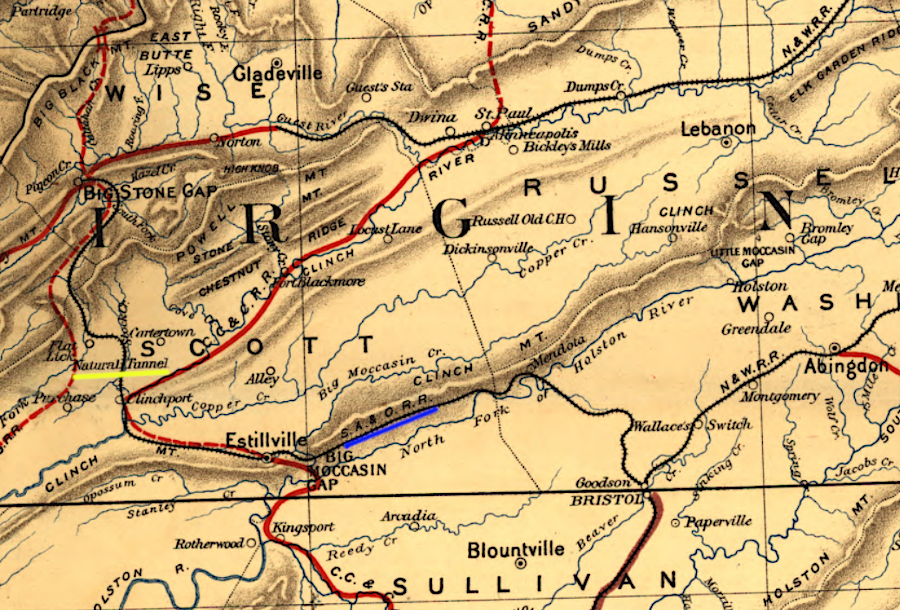

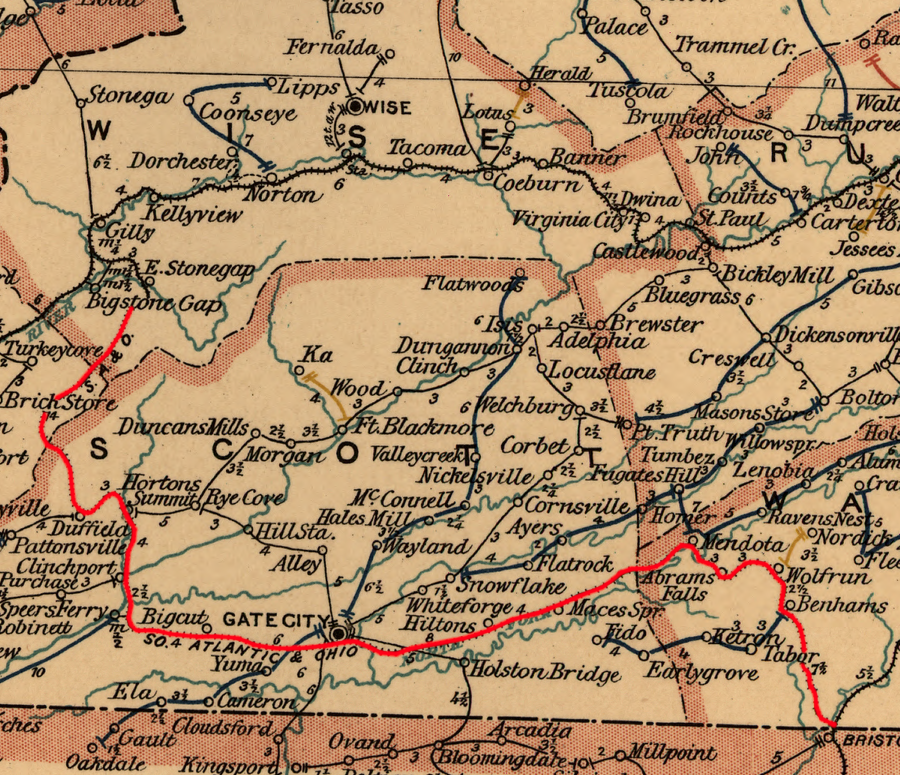

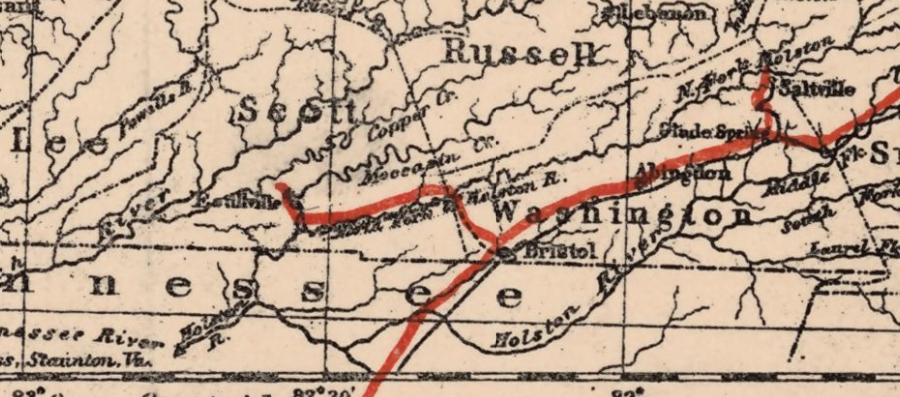

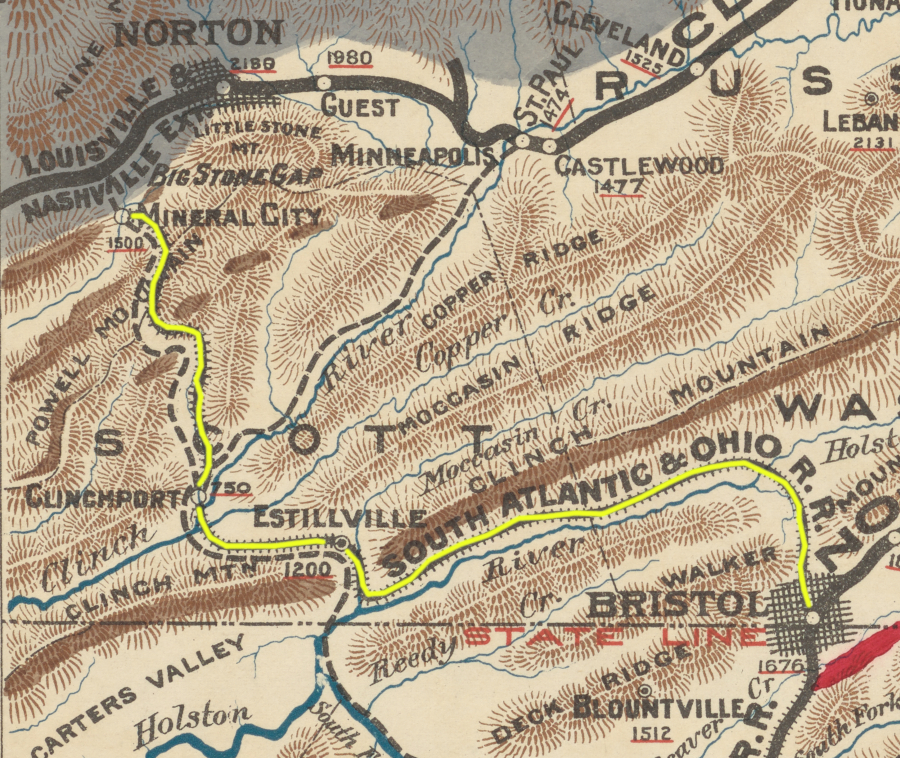

the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway connected Bristol to Big Stone Gap via Natural Tunnel in 1890, before it was incorporated into the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Preliminary map of Kentucky 1891

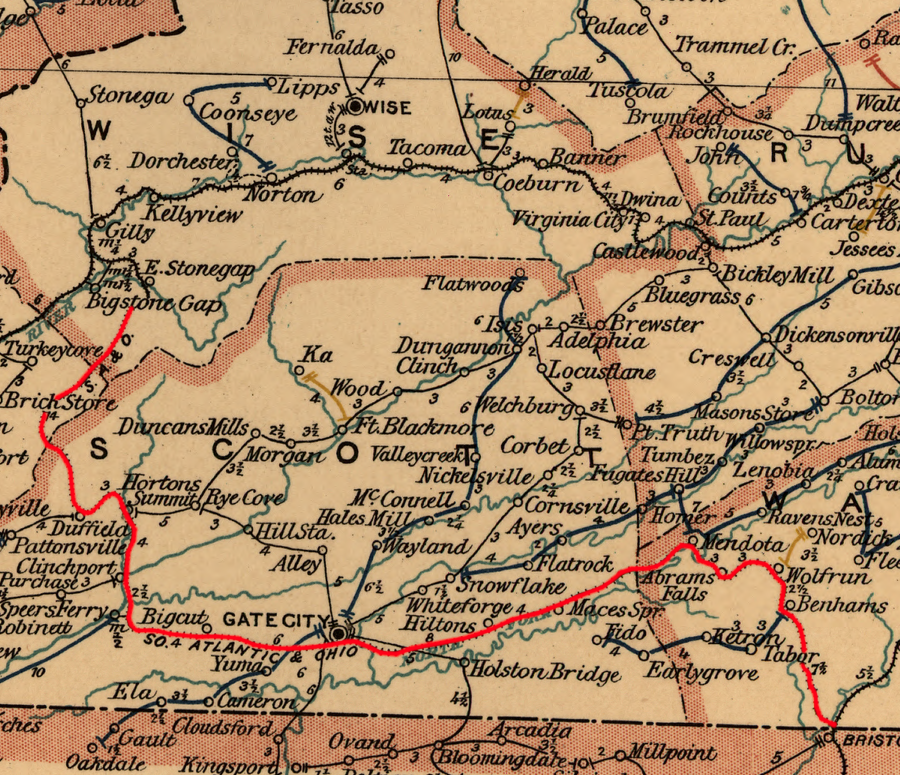

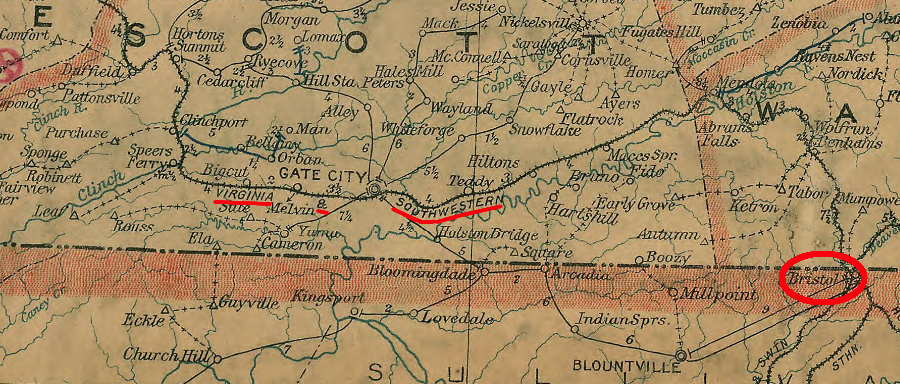

the South Atlantic and Ohio Railway in 1896

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the state of Virginia and West Virginia (1896)

The Bristol Coal and Iron Narrow Gauge Railroad was undercapitalized. Despite using free convict labor obtained from the state of Virginia, costs exceeded the funding available to complete the project. It was re-chartered as the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railroad in 1882.2

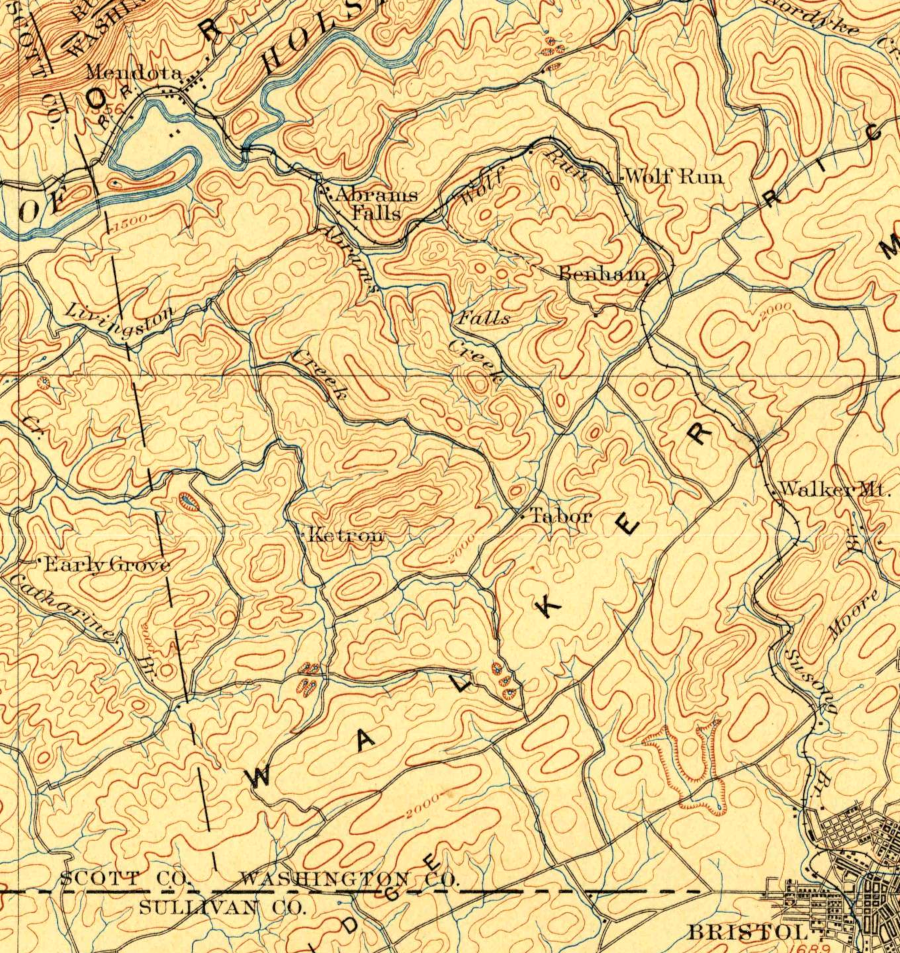

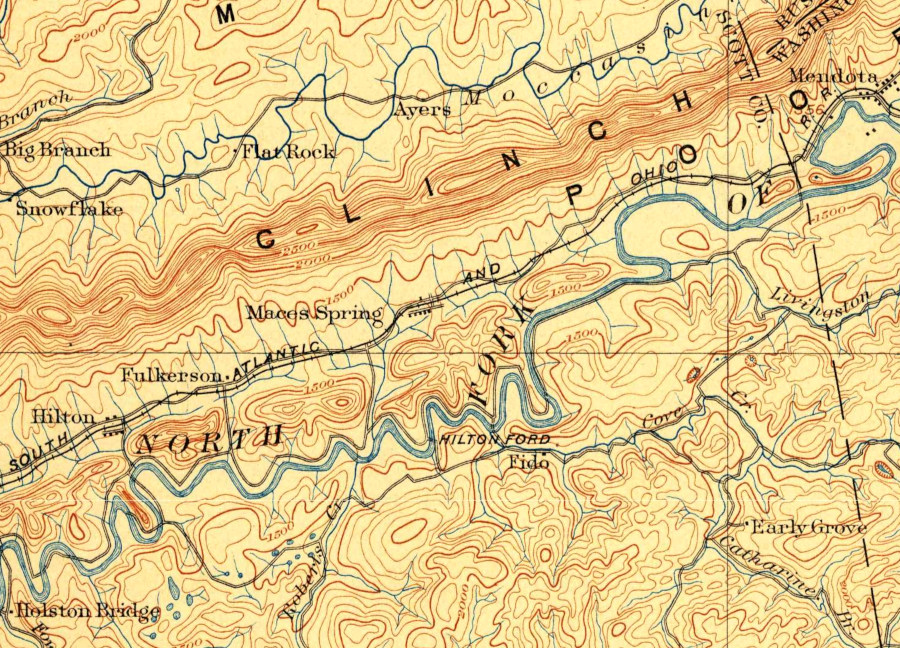

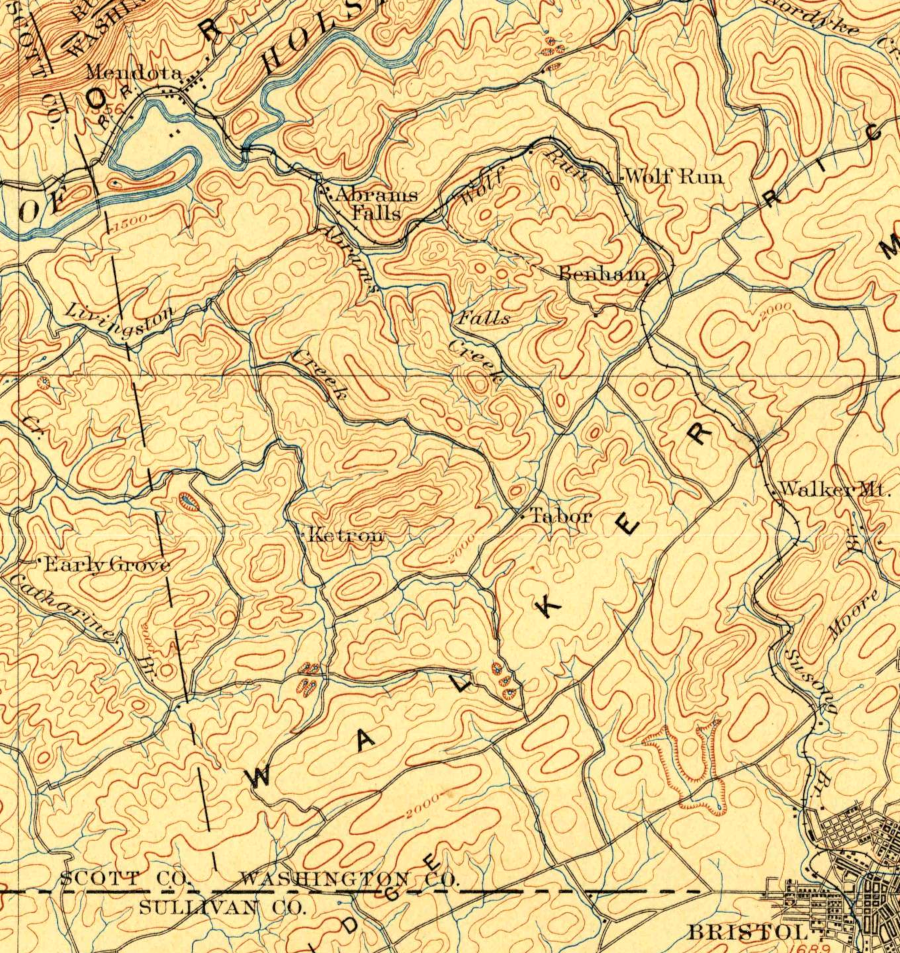

between Bristol and Mendota, the Bristol Coal and Iron Narrow Gauge Railroad crossed Walker Mountain

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bristol VA 1:125,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1902)

In 1880, coal speculators from Pennsylvania, working with former Confederate General John D. Imboden, purchased the railroad. They organized the Tinsalia Company and acquired substantial acreage with iron and coal potential, including the Kane-Oliver Grant and the Hagan Grant in Wise County.

The Tinsalia Company's hopes for quick profits evaporated. The Norfolk and Western Railroad absorbed the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad and chose to build track to the Pocahontas coal field, rather than join with General Imboden's investors and build track west from Bristol to develop the coal fields around Big Stone Gap. The Norfolk and Western Railroad based its decision on geography; the Pocahontas seam of coal in Tazewell County was 100 miles closer to Norfolk than the Wise County coal near Big Stone Gap.

The Pennsylvania speculators reorganized. After finding different investors, the Tinsalia Company was replaced by the Virginia Coal and Iron Company (VC&I). As the Pocahontas field expanded in the 1880's, the mineral-rich lands further southwest still had no railroad to ship coal or iron. While no mines developed, the potential was clear - if there was a way to transport coal and ore to market.

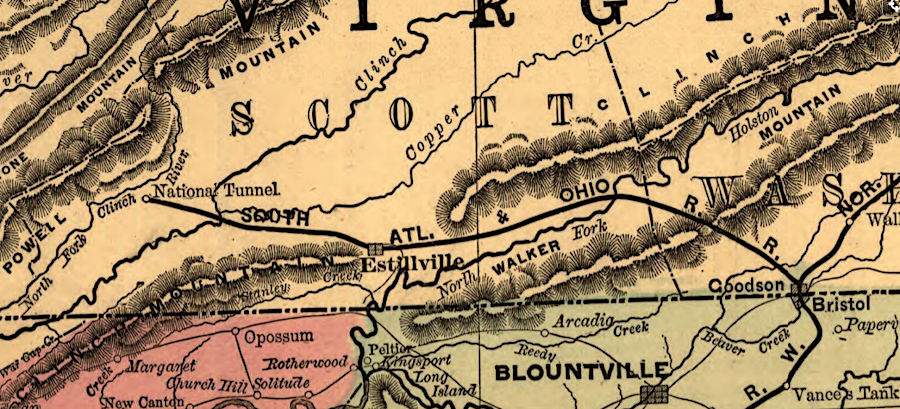

In an economic squeeze, the new Pennsylvania investors were forced to sell their coal rights in Pennsylvania to a competitor in that state, Henry C. Frick. That left them with just the speculative investment in Virginia, so the Virginia Coal and Iron Company (VC&I) focused on developing their property around Big Stone Gap. They renamed the Bristol Coal and Iron Narrow Gauge Railroad as the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway, and made it the first railroad to reach Big Stone Gap. It reached Gate City in 1888, and finished construction at Appalachia in 1890.3

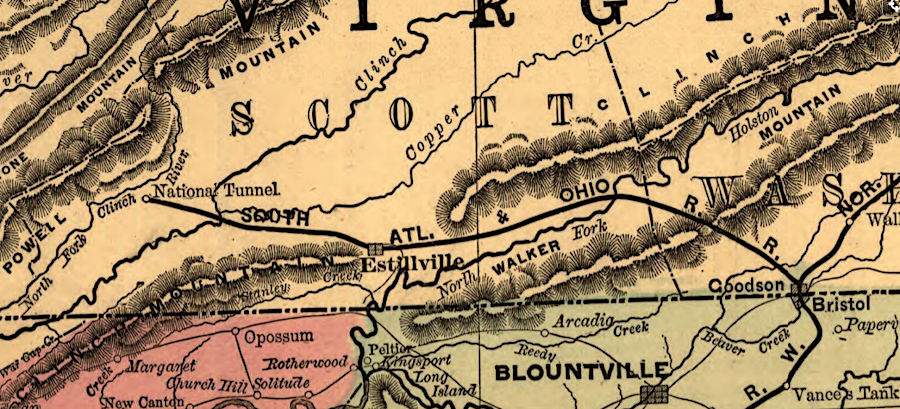

the South Atlantic and Ohio was built west from Bristol through Moccasin Gap near Estillville (Gate City)

Source: Library of Congress, Railway map of Virginia and West Virginia (by Jedediah Hotchkiss, 1887)

The undeveloped coal fields triggered multiple railroads to plan connections to Wise County at the end of the 1880's.

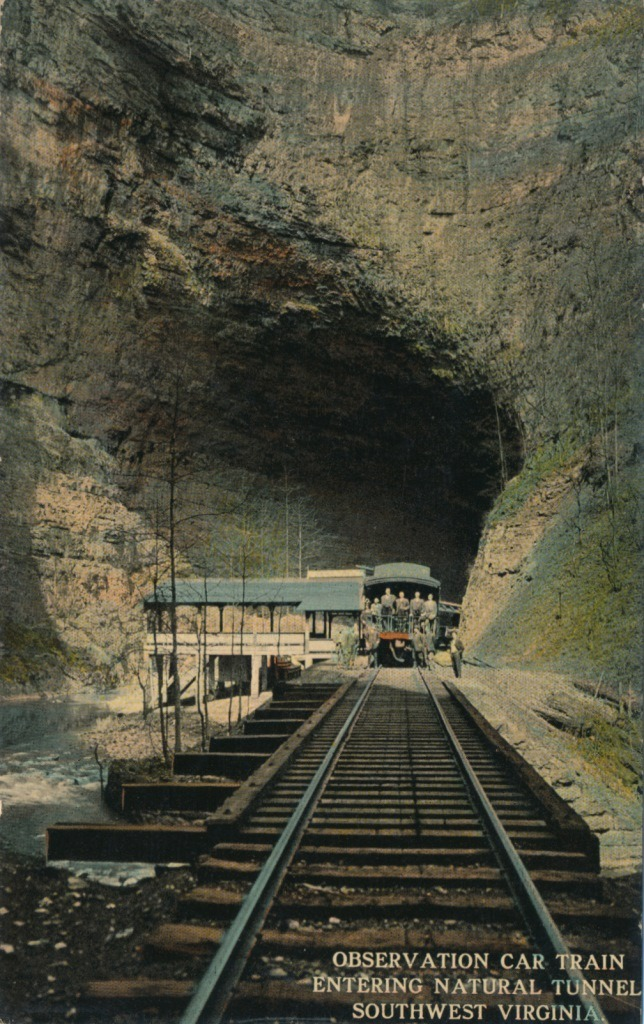

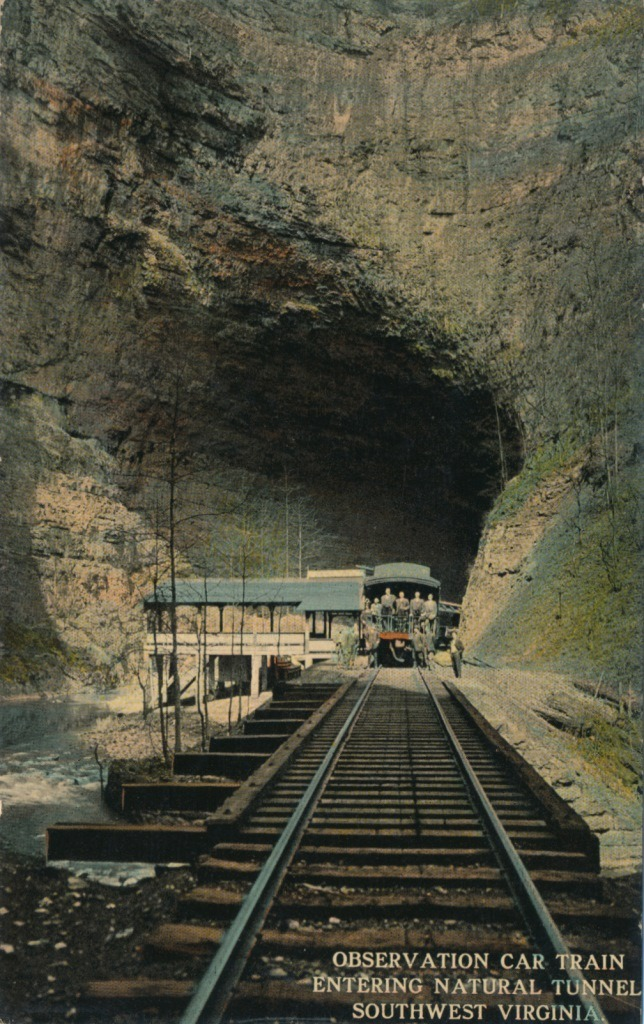

The South Atlantic and Ohio Railway used a route through natural gaps in the mountains, particularly Moccasin Gap through Clinch Mountain near Gate City. From Moccasin Gap to Clinchport, it utilized the trackbed prepared originally for the unfinished Charleston, Cincinnati and Chicago Railroad (the "3-C" line). North of Clinchport, the railroad cut through Purchase Ridge using the Natural Tunnel.

Natural ("National") Tunnel was used by the South Atlantic and Ohio Railway north of Clinchport

Source: Library of Congress, New enlarged scale railroad and county map of Tennessee showing every railroad station and post office in the state, 1888

the Norfolk Southern still runs trains through Natural Tunnel

Heading into the coalfields north of Gate City, the South Atlantic and Ohio Railway minimized the need for locomotives to haul cars up or down grade by taking advantage of Natural Tunnel on Stock Creek. The "Natural Tunnel line" is still in use today, with Norfolk Southern and CSX sharing trackage rights.

Th South Atlantic and Ohio Railway reached Big Stone Gap almost a year sooner than the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad, which finally got there in 1891. The two railroads did not connect in Big Stone Gap; a third railroad connected their depots in that town.

The short railroad in Big Stone Gap was formally known as the Big Stone Gap and Powells Valley Railway. Informally, it was called the Dummy Line. It used small locomotives called "dummies" to transfer freight and passengers back and forth between the South Atlantic and Ohio and the Louisville and Nashville railroads within Big Stone Gap. The Dummy Line finally closed in 1916, once automobiles and trucks were readily available in town.

the South Atlantic and Ohio Railway in 1890

Source: New York Public Library, Mineral territory tributary to Norfolk and Western Railroad (1890)

In 1889, the Louisville and Nashville and the South Atlantic and Ohio railroads planned to build a common track from Big Stone Gap up the Powell River, connecting Big Stone Gap to what later evolved as the city of Norton.

Plans changed when the South Atlantic and Ohio Railway ran out of money, in part due to the costs of building a tunnel. The South Atlantic and Ohio Railway managed to build through the gap between Stone Mountain and Little Stone Mountain to the confluence of Callahan Creek and the Powell River. The distance from Bristol to that site, which incorporated in 1906 as the town of Appalachia, was 71 miles. It also built up Looney Creek to its Inman mine, but the Louisville and Nashville Railroad gained control of access to many coal mines that the South Atlantic and Ohio Railway had planned to serve.

In the competition to access the coal fields of southwestern Virginia, the Louisville and Nashville extended past Appalachia to Princes Flat, 12 miles northeast of Big Stone Gap, in 1891. It renamed the site known after early settler William Prince, who had built a house there in 1787. A century later, the railroad gave it the name "Norton," after the president of the railroad Eckstein Norton. After the Norfolk and Western (N&W) Railroad extended its line from Bluefield to Norton, the two lines interchanged freight cars and both lines earned profits from the long-distance traffic.

the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway built up Looney Creek to its Inman mine

Source: Poors Manual of Railroads 1901, Railroad Map of the United States - Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia (after p.128)

The Virginia Coal and Iron Company had opened its first mine (Lower Osaka) further up Callahan Creek on Mudlick Creek, but financial constraints on the South Atlantic and Ohio enabled the Louisville and Nashville to control access to that mine and most others in the region.

The Louisville and Nashville even considered extending its track up further west, all the way up Callahan Creek into Kentucky. That would have required building the Interstate Tunnel through Black Mountain into the Cumberland River watershed, then crossing Pine Mountain to access the coal in eastern Kentucky. Further planning showed that the project would be too expensive; the Interstate Tunnel was never built.

Due to inadequate funding, the Virginia Coal & Iron Company failed to connect to its mines up Callahan Creek via the railroad it controlled. It lost control of the South Atlantic and Ohio through bankruptcy in 1892.

After the economic depression in 1893 ameliorated, the Virginia Coal & Iron Company tried to negotiate deals with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad to haul coke to Ohio River markets via the Cumberland Gap. It also bargained with the now-separate South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad to haul coal to textile mills and other customers in the southeastern United States. The investors in the Virginia Coal & Iron Company wanted assurances that transportation costs would be reasonable, before opening the Stonega mine and others on the lands the company owned in Wise County.

Negotiations were not fully successful; loss of control over the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad constrained the options of the mine owners. To control transportation costs, the Virginia Coal & Iron Company organized the Interstate Railroad in 1896. That company-controlled railroad loaded coke and coal at the mines not already being served by the Louisville and Nashville or the South Atlantic and Ohio railroads.

The Interstate Railroad was the mine owners' replacement for the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad, which had to be sold during economic hard times. The Interstate Railroad was a short line built to provide connections to the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, the Norfolk and Western Railway, and the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) Railway. Despite the name, 100% of the track owned by the Interstate Railroad was within Virginia.

The Interstate Railroad gave the mine owners needed leverage to bargain with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. As an independent railroad, it could chose where to deliver its loaded cars for transport by another line. The flexibility created the opportunity for rate bidding, substituting somewhat for the opportunity lost when the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad was unable to extend its network to mines beyond Looney Creek.4

The financially-stressed South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad was managed by receivers appointed by the bankruptcy court between 1892-1898, when George L. Carter acquired it at auction. He also purchased the Bristol, Elizabethton, and North Carolina Railroad, which he extended 36 miles to Mountain City, Tennessee in 1900 to transport timber products.

Carter combined the railroads and renamed them as the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad, as he developed his ambitious larger plans for the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) Railway.

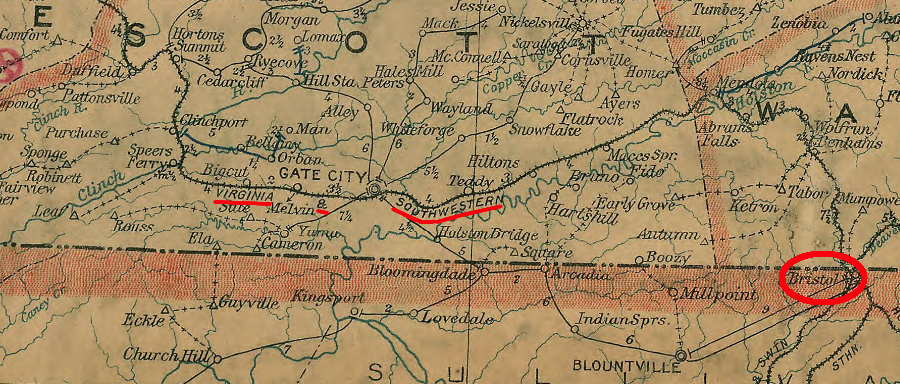

In addition to acquiring a few spur railroads, the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad made two significant acquisitions in 1908. Purchasing the Holston River Railroad, while it was still under construction, connected the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad at Moccasin Gap with the Southern Railway at Persia Junction, near Rogersville, Tennessee.

The Virginia and Southwestern Railroad also acquired the Black Mountain Railway. Its 21 miles of track extended west of Imboden to St. Charles, providing access to a larger number of mines in the coal fields of Wise and Lee counties.5

That connection provided an essential choice. Prior to the connection with the Southern Railway in Tennessee, the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad could interchange cars only with the Norfolk and Western (N&W) Railroad at Bristol. With the connection to the Southern Railway, the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad had an alternative outlet, giving the company more leverage in negotiating interchange rates .

the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad carried all cars to Bristol, until it acquired a connection south of Gate City to the Southern Railway

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the states of Virginia and West Virginia (Postmaster General, 1906)

The Virginia and Southwestern Railroad was a part of the Virginia Iron, Coal, and Coke (VIC&C) Company. When the coal company went into bankruptcy in 1906, the Southern Railway purchased it to ensure continued access to the Virginia coal traffic.

If the Louisville and Nashville Railroad had bought the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad in 1906, the coal might have been shipped to Ohio River customers or mines might have closed temporarily because railroad shipment rates would have been too high for profitable operations. If the Louisville and Nashville had chosen to interchange cars with the Southern Railway, at a minimum the Southern would have carried the coal a shorter distance and its profits would been reduced.

The Louisville and Nashville had been successful at blocking the Interstate from building a direct connection with the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad at Appalachia. As a result, when the Interstate brought cars from Norton to Appalachia, it had to pay fees to the Louisville and Nashville in order to get those cars onto the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad's track. By forcing higher costs on the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad's delivery of coal to the Southern Railway's mainline, the Louisville and Nashville gained competitive advantage.

For eight years after 1909, the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad partnered with the Interstate Railroad and created the Appalachian Terminal Association. That arrangement allowed the two railroads to share equipment and crews and reduce operating costs, which was needed to force the dominant Louisville and Nashville Railroad to lower its rates.

In 1916, a decade after the 1906 purchase, the Southern Railway converted the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad into just a subsidiary company. With loss of its corporate status, the Virginia and Southwestern Railroad became a "fallen flag" railroad in 1916.

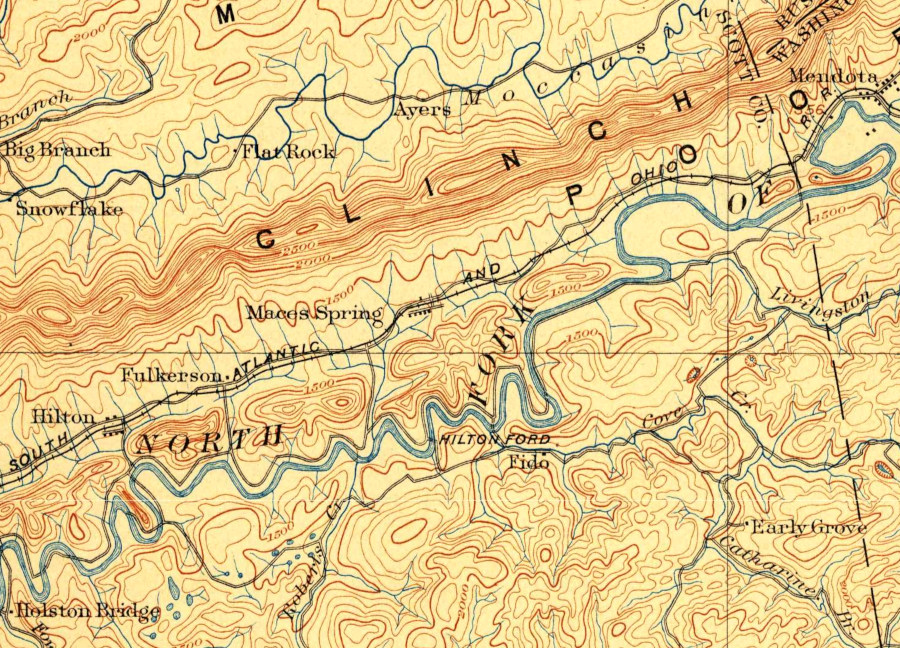

the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) followed the North Fork of the Holston River from Mendota down to Moccasin Gap, where it crossed Clinch Mountain

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bristol VA 1:125,000 scale topographic quadrangle (1902)

When the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) had needed to cross Clinch Mountain almost 20 years after the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway, it chose to cut a major tunnel though the sandstone ridge of Clinch Mountain. The alternative was to go 10 miles east to Moccasin Gap, the route used by the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway. However, the Clinchfield was a north-south line hauling coal to South Carolina. It had no reason to go east towards Moccasin Gap because, unlike the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway, it had no need to connect to the Norfolk and Western Railroad at Bristol.

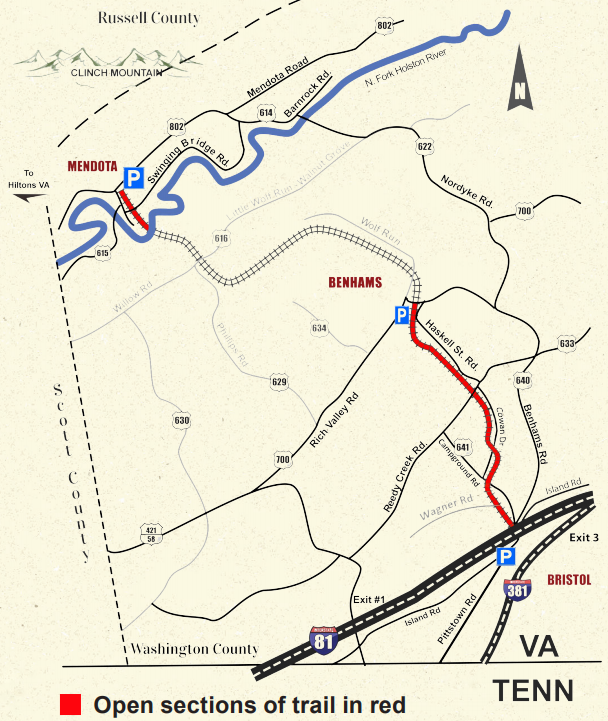

The Southern Railway abandoned the Bristol-Big Stone Gap line in 1972. That led to an effort to create the Lonesome Pine Special Trail, named after a passenger train that once steamed between Bristol and Cincinnati.

Adjacent property owners claimed the right-of-way reverted to them. Numerous lawsuits blocked efforts to convert the abandoned line into a hiking/biking trail. After 16 years and spending $600,000 on the project, in 2016 the City of Bristol transferred its rights to the old railroad to a non-government organization, Mountain Heritage.

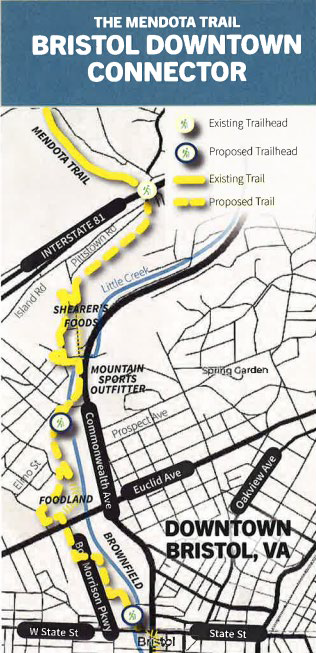

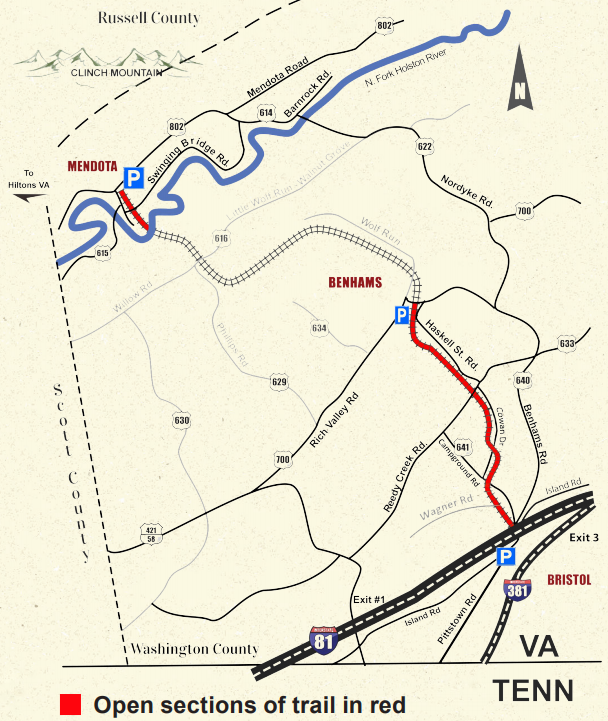

efforts to create the Lonesome Pine Special Trail were blocked by disputes over ownership of the abandoned right-of-way

Source: Mountain Heritage, Inc., Mendota Trail

A Circuit Court judge finally "quieted title" (settled ownership of the land) in a 2007 ruling:7

- ...the court finds the deed states if the railroad is built then the possibility of reversion is extinguished. The railroad was built. Therefore, the condition of reversion was satisfied and the railroad and its assigns owned a fee simple interest in the property conveyed

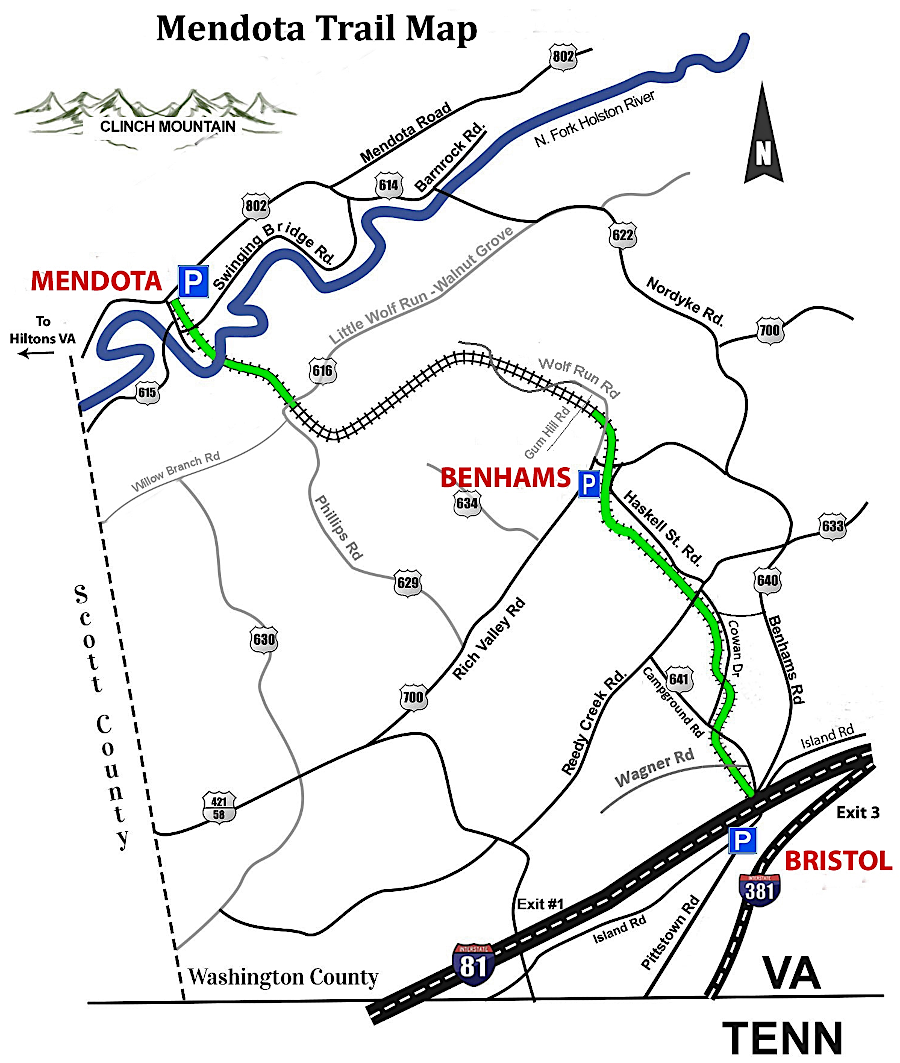

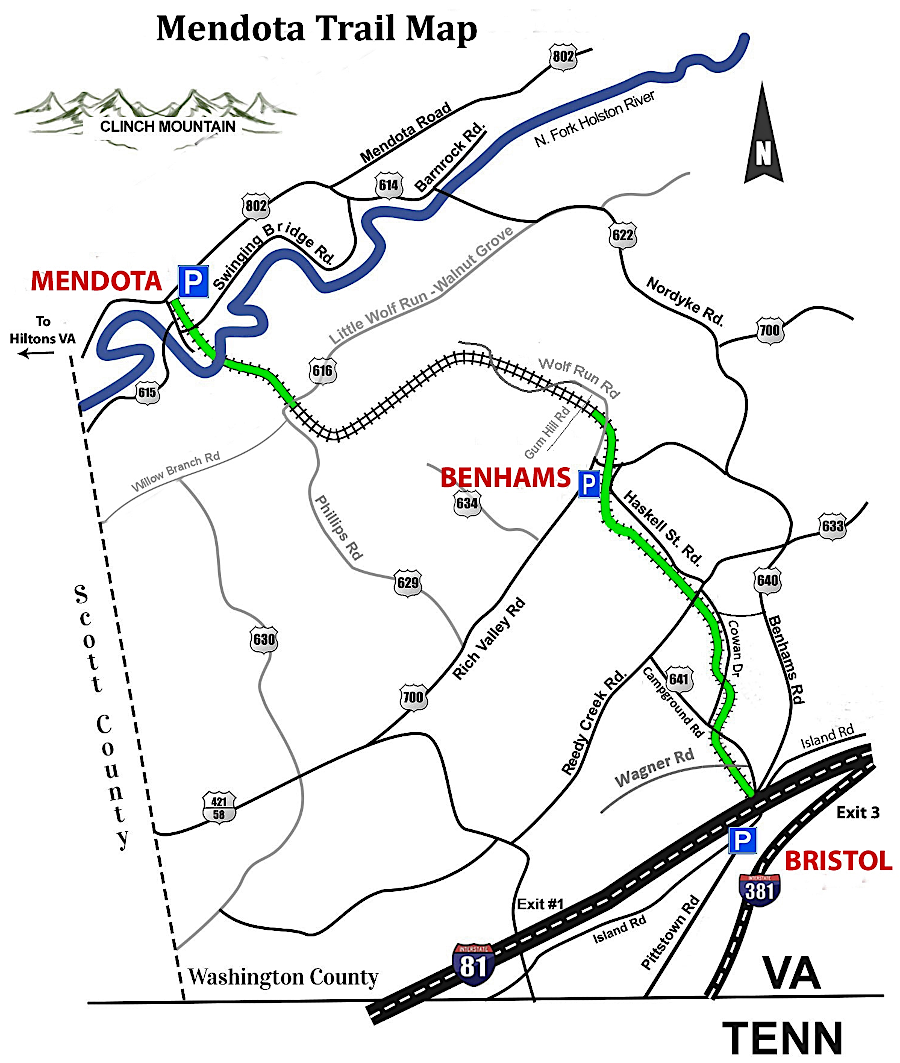

Mountain Heritage planned to build the Mendota Trail from Bristol to Mendota, 12.5 miles away. The first mile opened in 2017. In 2018 a 3.1 mile segment linked Island Road at the western edge of Bristol to Reedy Creek Road in Washington County. A 2.1 mile segment opened in 2020 extended the trail west to Benhams. That section included Trestle No. 3, almost 200 feet long above Abrams Creek.

the first segment of the Mendota Trail went one mile east from Civil Drive and Mendota Road (red X) to the swinging bridge parallel to the old North Fork trestle

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Also in 2020, Mendota Trail Conservancy assumed ownership of the trail. Another mile, with three additional trestles, was opened in 2021.

12.5 miles of the former Virginia and Southwestern Railroad route were scheduled for conversion into the Mendota Trail

Source: Mountain Heritage, Inc., Mendota Trail

In 2022, Governor Glenn Youngkin cut the ribbon to open another segment with five new trestles in the Wolf Run Gorge. At that point, only one mile was left to be completed on the original proposal for the Mendota Trail, and funding had been provided for that segment.

by the start of 2022, there was clear progress in building more mileage of the Mendota Trail

Source: Mountain Heritage, Inc., Mendota Trail

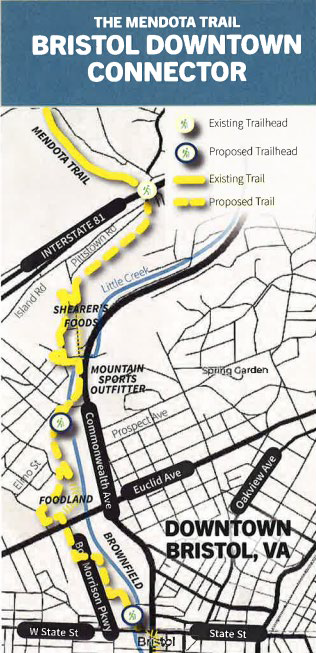

The 2021 master plan included the possibility of extending the trail east into downtown Bristol. The most ambitious planning included the Mendota Trail as a part of the Beaches to Bluegrass Trail, identified in 2014 as a connection between Cumberland Gap and the Atlantic Ocean.8

Bristol City Council selected a contractor in 2025 to design a connection of the city's downtown with the Mendota Trail

Source: Bristol City Council, Feasibility Study/Pre-Engineering Plan Mendota Trail to Downtown Bristol Connector (January 13, 2025)

Links

the Mendota Trail underneath and west of I-81 is paved

References

1. "South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad Company," Annual Report, Virginia, Railroad Commissioner, 1898, p.285, https://books.google.com/books?id=mCUaAQAAIAAJ; Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. Valuation reports, Volume 37, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932, p.819, https://books.google.com/books?id=Kp8FAAAAIAAJ (last checked July 14, 2020)

2. Ed Wolfe, The Interstate Railroad: History of an Appalachian Coal Road, Old Line Graphics, 1994, p.8; Robert M. Addington, History of Scott County, Virginia, The Overmountain Press, 1992, p.194, https://books.google.com/books?id=n2pWQWkA1cUC; Victor N. Phillips, Bristol, Tennessee/Virginia: A History, 1852-1900, The Overmountain Press, 1992, p.186, https://books.google.com/books?id=4ia8w11q6yAC; Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. Valuation reports, Volume 37, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932, p.819, https://books.google.com/books?id=Kp8FAAAAIAAJ (last checked July 14, 2020)

3. Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. Valuation reports, Volume 37, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932, p.801, https://books.google.com/books?id=Kp8FAAAAIAAJ (last checked July 14, 2020)

4. Ed Wolfe, The Interstate Railroad: History of an Appalachian Coal Road, Old Line Graphics, 1994, pp.8-23; James A. Goforth, Building the Clinchfield: A Construction History of America's Most Unusual Railroad, The Overmountain Press, 1989, p.15, https://books.google.com/books?id=IJogvQseFS4C; "Norton History" City of Norton, http://www.nortonva.org/446/City-History; Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. Valuation reports, Volume 37, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932, p.817, https://books.google.com/books?id=Kp8FAAAAIAAJ (last checked July 14, 2020)

5. Robert M. Addington, History of Scott County, Virginia, The Overmountain Press, 1992, pp.194-195, https://books.google.com/books?id=n2pWQWkA1cUC; "The Railway Age," Railroad Gazette, Volume 45 (May 1, 1908), p.645, https://books.google.com/books?id=hqA9AQAAMAAJ; Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States. Valuation reports, Volume 37, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1932, p.802, p.810, pp.821-823, https://books.google.com/books?id=Kp8FAAAAIAAJ (last checked July 14, 2020)

6. Tony Scales, Natural Tunnel: Nature's Marvel in Stone, The Overmountain Press, 2004, p.50, https://books.google.com/books?id=_vj4eDwXmQwC (last checked May 14, 2018)

7. "Mendota Trail History," http://kba.tripod.com/mendota/history.htm; Lonesome Pine Special brochure, http://kba.tripod.com/mendota/LonesomePineSpecialTrail.pdf; "The Mendota Trail makes a comeback," Southwest Virginia Today, October 4, 2017, https://swvatoday.com/news/article_d993072d-fe56-52ef-a43d-beb4acc945db.html (last checked March 1, 2021)

8. Mendota Trail Newsletter, Mountain Heritage, Inc., Volume 1 (Fall, 2017), http://mendotatrail.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MendotaTrailNewsletterV1.pdf; "The Mendota Trail makes a comeback," Southwest Virginia Today, October 4, 2017, https://swvatoday.com/news/article_d993072d-fe56-52ef-a43d-beb4acc945db.html; "Mendota Trail may connect to downtown Bristol," Southwest Virginia Today, February 24, 2021, https://swvatoday.com/news/article_1f6fef76-758f-11eb-b16b-1f23d84eeaa1.html; "Watch Now: New section to be opened on the Mendota Trail," Bristol Herald-Courier, November 9, 2020, https://heraldcourier.com/news/local/watch-now-new-section-to-be-opened-on-the-mendota-trail/article_923c9eb8-9e78-524f-b542-05c1ce03d42f.html; "Mendota Trail to open three Trestles and extend more trail," Johnson City Press, October 9, 2021, https://www.johnsoncitypress.com/living/outdoors/mendota-trail-to-open-three-trestles-and-extend-more-trail/article_b162123a-2613-11ec-8edf-b3eda5be8071.html; "Youngkin helps open new section of Mendota Trail," Kingsport TimesNews, October 14, 2022, https://www.timesnews.net/news/local-news/youngkin-helps-open-new-section-of-mendota-trail/article_55d91f1c-4bd3-11ed-a70b-5fd97ddf2f08.html; "Agenda Bristol: City to discuss hiring a firm to study connecting Mendota Trail to downtown," Cardinal News, April 21, 2025, https://cardinalnews.org/2025/04/21/agenda-bristol-hiring-a-firm-to-study-connecting-mendota-trail-to-bristols-downtown-on-the-agenda-for-tuesdays-city-council-meeting/ (last checked April 21, 2025)

Natural Tunnel cuts through Purchase Ridge near Duffield in Scott County

Source: Library of Virginia, Infrastructure Week: 1870s Edition

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places