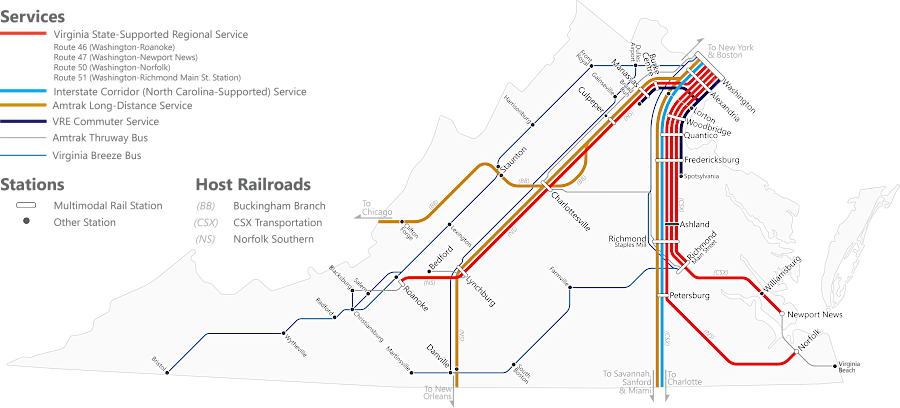

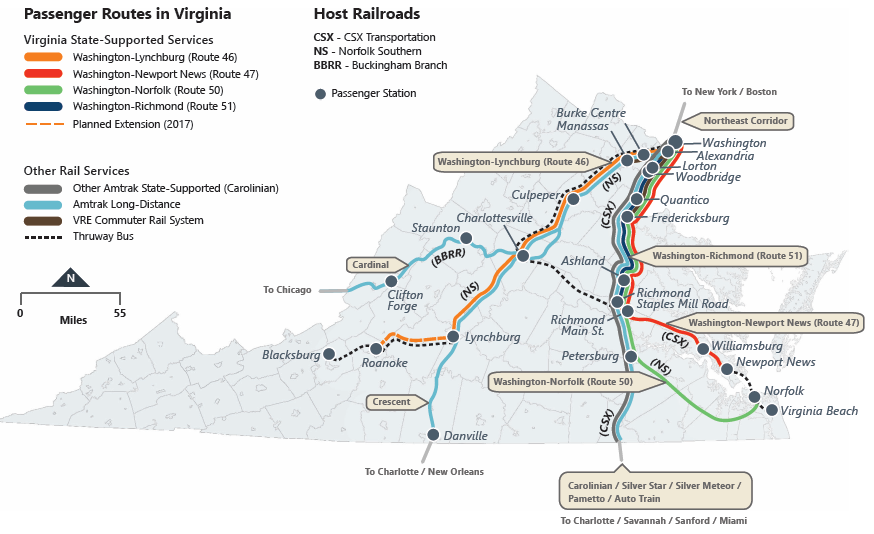

in 2022, passenger rail service between Norfolk-Roanoke required taking a train through Alexandria

Source: Draft 2022 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan

in 2022, passenger rail service between Norfolk-Roanoke required taking a train through Alexandria

Source: Draft 2022 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan

Once Europeans colonized Virginia, the transportation network developed as a farm-to-market system, expanding beyond the trails initially created by Native Americans. For 250 years after Jamestown was settled in 1607, the primary transportation requirement of Virginia's residents was the need to move bulky, heavy tobacco from farm fields to Europe.

Large plantations and small farms produced a surplus of that one staple crop. People do not eat tobacco, and the supply vastly exceeded local demand for smoking/chewing, so Virginians had to ship tobacco to customers.

The need to export tobacco across the Atlantic Ocean caused settlement to be concentrated along Tidewater rivers during the 1600's and 1700's. Every plantation in Tidewater developed a wharf to ship tobacco directly to England - hauling 1,000-pound hogsheads of tobacco along muddy roads from tobacco barns just to a wharf was hard enough.

Roads were developed so people could walk or ride from farms to churches and the county courthouse, but until settlement began to move upstream past the Fall Line in the 1720's, there was little investment in building land-based transportation. Once Virginians moved into the Piedmont, agricultural freight was hauled in wagons on dirt roads to Tidewater ports. Turnpikes were chartered, starting with the Little River Turnpike in 1795. Stockholders funded road improvements/bridges and ensured regular maintenance, in exchange for tolls. The Manchester Pike was coated with gravel in 1808, becoming the first paved road in Virginia.1Shipping farm products in bulk via dirt roads was expensive, so new technology was explored to improve farm-to-market transportation. Virginia politicians such as George Washington tried to create artificial waterways, with both economic and political objectives. Canals crossing the Appalachians would steer business to Atlantic Ocean ports (rather than down the Mississippi River to New Orleans), and economic ties would ensure the western settlers retained their allegiance to the United States (rather than consider allying with Spain, which controlled New Orleans until the Louisiana Purchase).

Canals built along the Potomac River and the James River were expected to reach the Ohio River, in hopes of mimicking the success of the Erie Canal. However, the canal builders had competition.

Starting in the 1830's, the new technology of wood-burning locomotives and iron rails stimulated cities on the Fall Line to build low-cost railroad connections to inland "backcountry" or "hinterland" areas, far away from navigable rivers. From the beginning, rail construction in North America showed how one port city could use new transportation technology to intercept the trade of another port. The first large-scale use of steam-powered locomotives in North America was the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company, built to connect Charleston to the Fall Line of the Savannah River at Augusta, Georgia.

the South Carolina State Museum exhibits a reconstruction of the "Best Friend of Charleston," the first wood-burning locomotive in the United States

The railroad enabled Charleston to "steal" business from Savannah. The primary commodity shipped in the region was cotton, grown in the South Carolina/Georgia Piedmont. Farmers had been carrying cotton in wagons to the Fall Line to Augusta, Georgia. There, the bales were loaded on ships that could sail up to the falls on the Savannah River. After construction of the railroad, farmers found it more profitable to ship their cotton to Charleston by rail, shifting their business from Georgia to South Carolina. The rail line provided benefits to one port city and one state, at the expense of another.

Despite the clear success of the South Carolina railroad, Virginia politicians continued to debate the relative merits of canals vs. railroads. The Virginia State Engineer, Claudius Crozet, recommended shifting public investment from canals to railroads in 1830, but the General Assembly then forced his resignation. Crozet was later re-hired, but political support for canals (especially the James River and Kanawha Canal) led the General Assembly to eliminate his pesky advice by abolishing the office of chief engineer in 1843.2

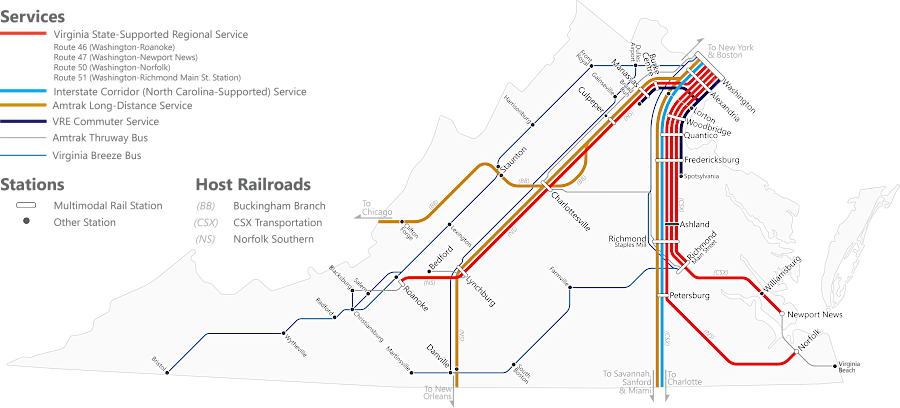

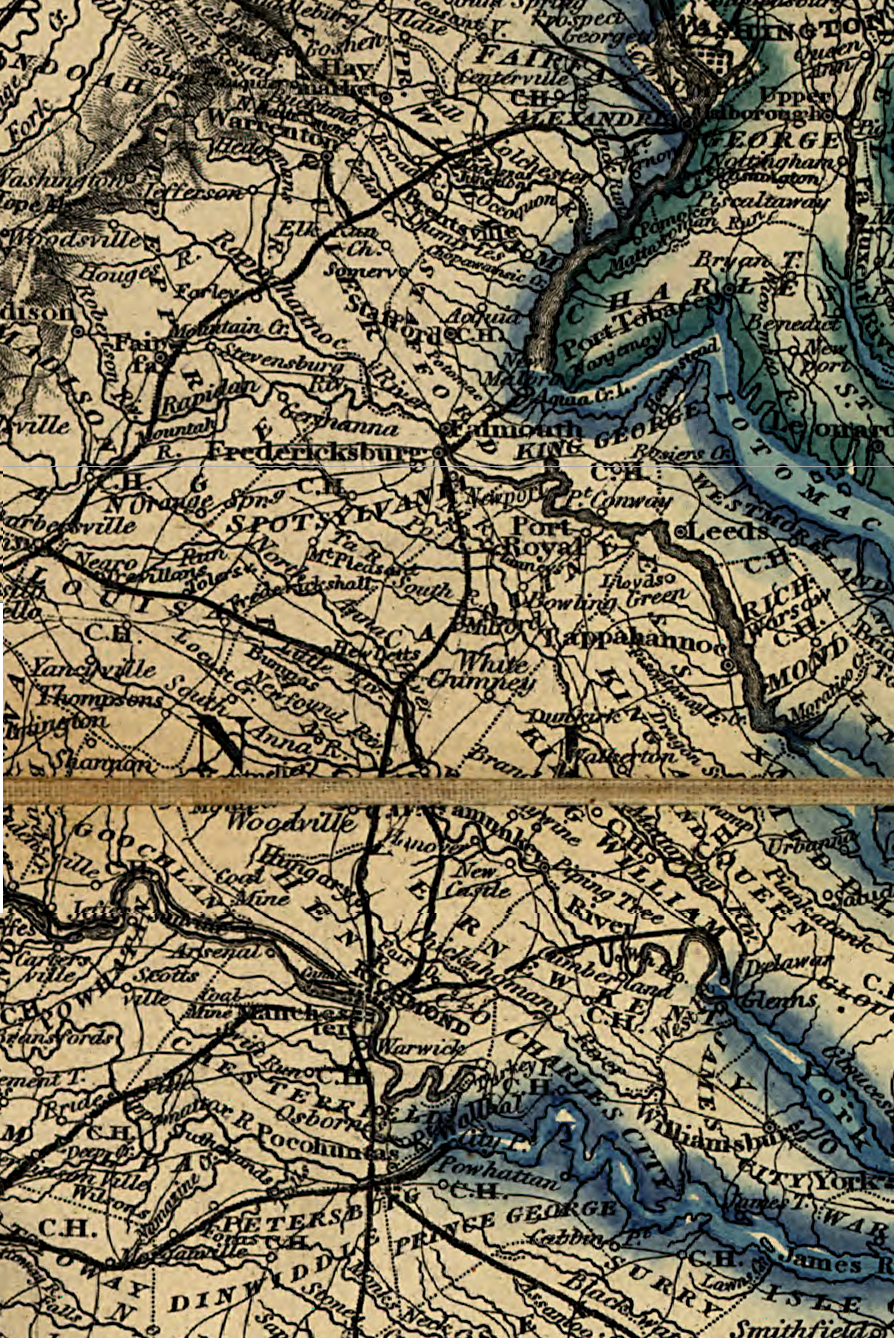

Between 1850-1950 railroads were the focus for expanding transportation capacity in Virginia. However, prior to the Civil War, Virginia's railroads were not designed to create a logical transportation network linking all major cities in the state.

railroads in 1848 hauled coal from Chesterfield County mines, using wood-burning locomotives

Source: Library of Congress, Railroads in Virginia and part of North Carolina, drawn and engraved for Doggett's Railroad Guide & Gazetteer

Virginia's railroads were designed originally to transport farm products to specific ports, mimicking the farm-to-market pattern of turnpikes. Local stockholders constructed competing rail lines to develop trade to competing Virginia cities. The General Assembly subsidized the competition by purchasing 40-60% of the stock without requiring companies to cooperate.

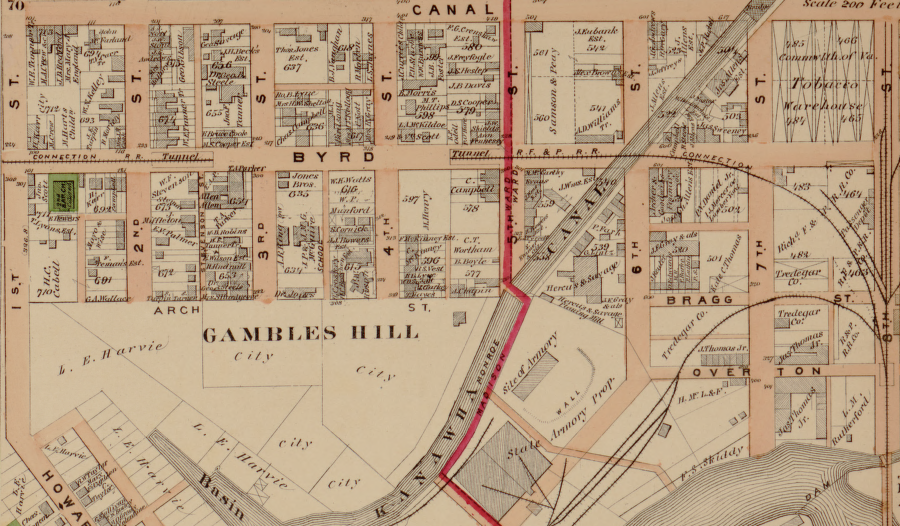

Even in Virginia cities served by two or more railroads, the separate tracks were not connected with each other. Each railroad built its terminal in a separate location, demonstrating its intent to send trade to a specific city. If the railroad lines had been designed to provide transportation through the city for a more-distant destination, tracks would have been joined and a common gauge would have been adopted. Instead, some Virginia railroads built tracks with a "broad" 5-foot distance between the rails while others used the "standard" gauge of 4 feet, 8-1/2 inches.

In the days before union stations, local draymen earned a good living hauling freight by horse and wagon from one railroad's terminal to another. Passengers with luggage had to pay for local carriages to get between terminals, usually just several blocks away. Through-travel was difficult. Local hotels benefited from inconsistent train schedules that required passengers to wait overnight, before catching a train on a separate line the next day.

until the 1850's, there was no railroad line linking Richmond with points north of Fredericksburg

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Railroads in Operation, 1840 (Plate 138L) digitized by University of Richmond

Though state taxpayers financed 40-60% of the cost for most Virginia railroads, the lines were located to serve as tools for local economic development and not for the entire state. Refusing to link rail lines was inefficient, but each railroad was independent. Individual cities benefited from carting and warehousing the freight, and from passengers who bought meals or stayed overnight.

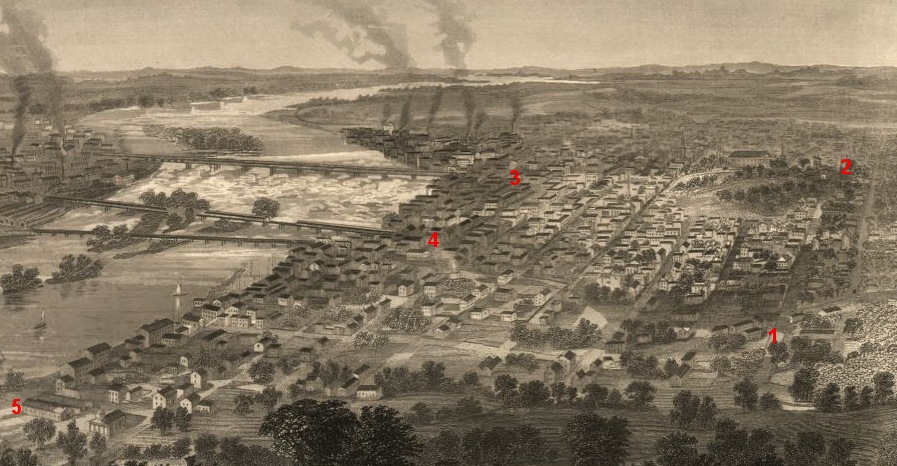

before the Civil War, railroad freight stations in Richmond - the Virginia Central (1), RF&P; (2), Richmond and Petersburg (3), Richmond and Danville (4), and Richmond and York River (5) - were not connected by rail

Source: Library of Congress, Richmond, Va. and its vicinity (1863)

Political decisions on what railroads to authorize - or block - affected the land use, population growth, and wealth of competing communities. Different cities financed different railroads to bring farm products, timber, and iron to a specific port on the Fall Line, and to ship manufactured goods (especially imports from Northern manufacturing centers and overseas) back to rural areas. Railroad managers often struggled to fill their boxcars with cargo headed back to the hinterland.

Sectional competition in railroad construction mirrored the competition in canal construction. The most intense conflicts for state charters and funding were between cities on the Potomac vs. James rivers, steering traffic from the Piedmont/Shenandoah Valley to ports on the Fall Line.

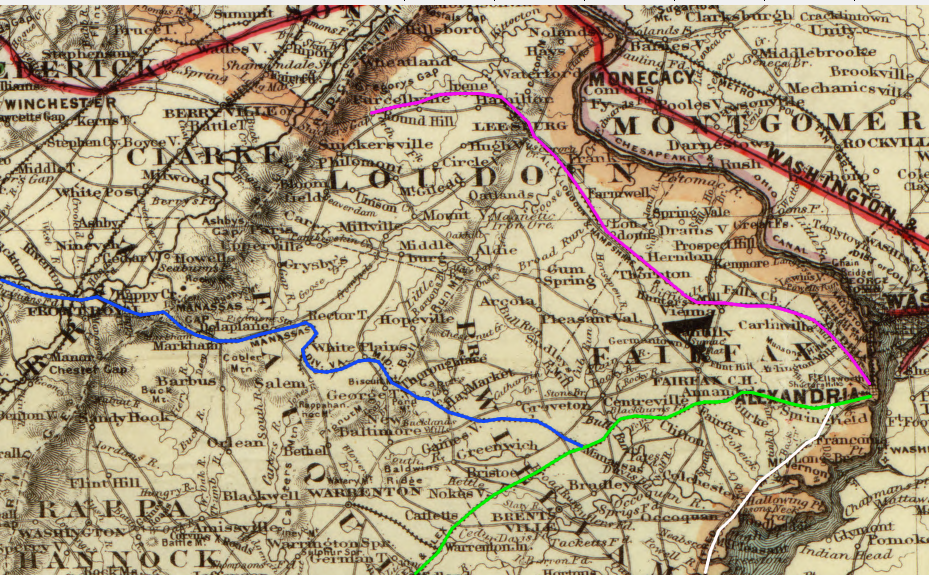

Alexandria was a shipping port that incentivized farmers to trade in Alexandria by building the Orange and Alexandria, the Manassas Gap, and the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire railroads.

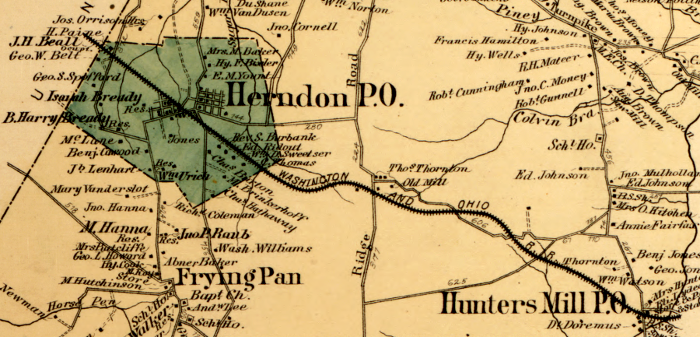

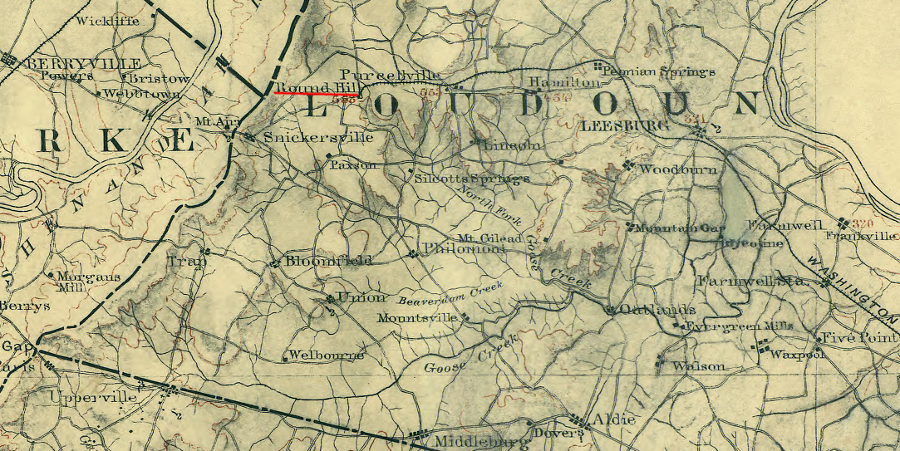

Alexandria investors built the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad to steer business to Alexandria from Loudoun County and (ideally) the Shenandoah Valley and the coal fields of Hampshire County

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins)

Richmond-oriented investors built the Virginia Central and other lines to draw business to their port, particularly in competition with Norfolk. Petersburg investors funded the South Side Railroad, which drew trade away from Richmond. Completion of that railroad to Lynchburg forced the James River and Kanawha Canal to reduce its tolls.3

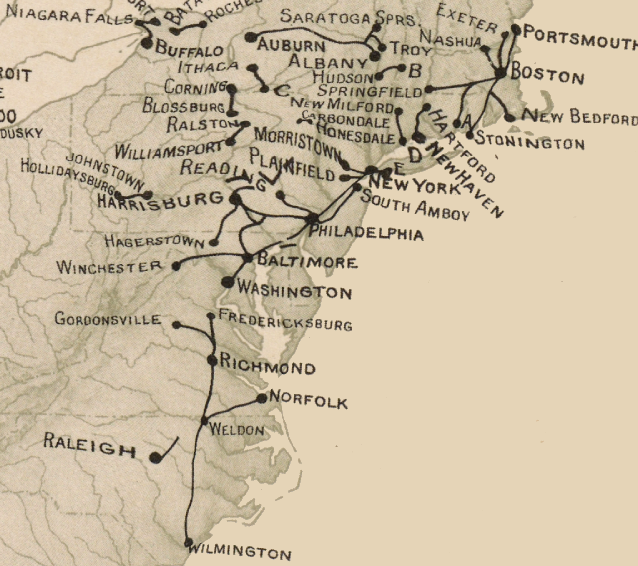

One exception: the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac (RF&P) ran north from Richmond to Fredericksburg, and then to docks on the Potomac River at Aquia Creek. Unlike most other Virginia railroads, the RF&P; expected to make most of its income from north-south traffic, transporting people rather than west-to-east freight.

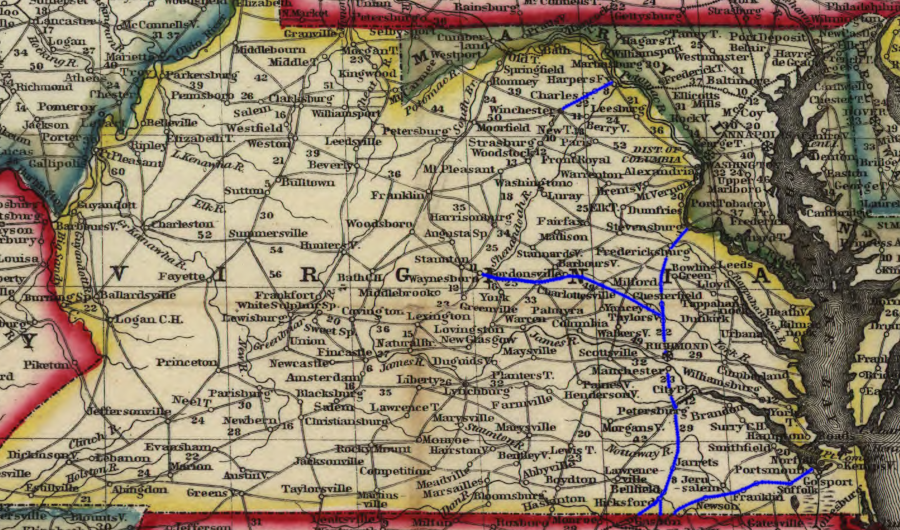

except for the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac (RF&P), railroads transported goods from the hinterland to port cities

Source: Library of Congress, Phelps's national map of the United States (1852)

The concept of an interstate trade network, or even regional rather than local service, would require the consolidation of separate railroad companies. That finally occurred through a series of mergers and hostile takeovers after the Civil War, when the General Assembly sold its stock in railroads to northern investors and control of railroads shifted to non-Virginian capitalists.

Prior to 1861, the General Assembly authorized railroad lines that would steer trade from the Piedmont/Valley and Ridge provinces to a favored Fall Line port - and blocked most proposed railroad extensions that would have directed Shenandoah Valley trade to an out-of-state port. Multiple rail lines were authorized to cross the Blue Ridge and link Alexandria/Richmond with the Shenandoah Valley, but the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O;) railroad was blocked from building south from Harpers Ferry, except for a short extension to Winchester.

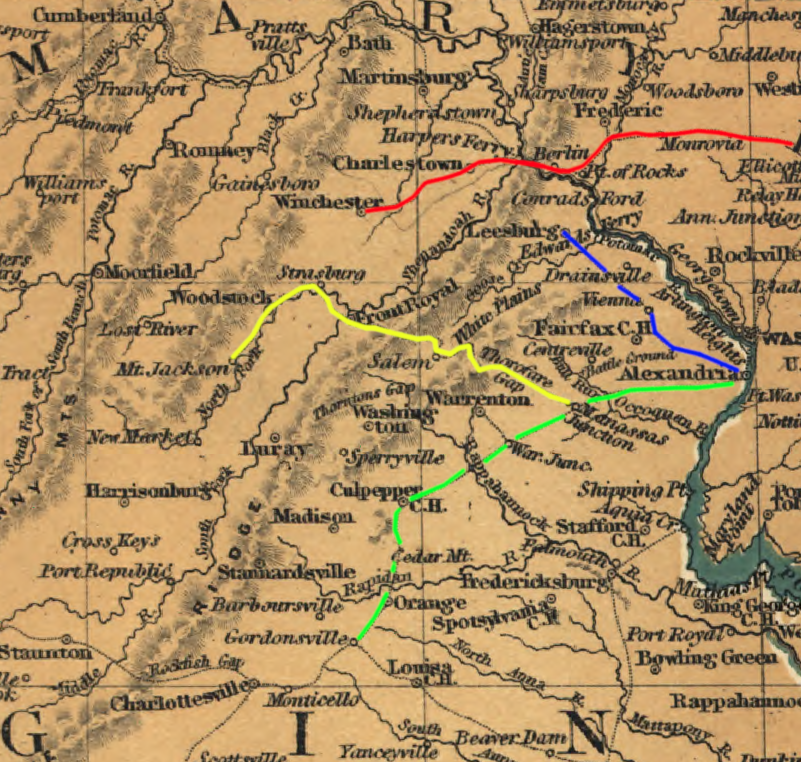

Winchester got a rail connection to Baltimore (red), while much of Northern Virginia could only ship to Alexandria

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and part of Pennsylvania (by Jacob Wells, 1863)

At Harpers Ferry, trains went over a 900-foot long viaduct above the Potomac River, then used the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O;) railroad to carry Virginia-grown farm products to market at Baltimore. The Winchester and Potomac railroad found few manufactured items or other goods to load at Harpers Ferry for the back haul, so it agreed to carry "plaster" (lime fertilizer) for free. The plaster was used to increase fertility of wheat fields in the Shenandoah Valley, ultimately generating more flour/wheat for the railroad to haul to Harpers Ferry, but the railroad depended upon one-way travel from farm to market.4

Up to 1881, Staunton could ship directly to Richmond and Front Royal could ship directly to Alexandria - but those cities had no rail connection to Winchester.

The Strasburg-Winchester rail gap, maintained by a General Assembly unwilling to charter a railroad link until after the Civil War, ensured most of the valley did not have a railroad connection to Baltimore or Philadelphia. Rail lines were constructed to connect all major population centers only after Virginia came close to bankruptcy during Reconstruction, and northern capitalists gained sufficient economic/political control to re-shape the pattern of railroads in Virginia.

gap in railroad lines between Winchester and Strasburg, in Shenandoah Valley (1861)

Source: Library of Congress, Lloyd's official map of the state of Virginia from actual surveys by order of the Executive 1828 & 1859

Prior to the Civil War, Alexandria built the Orange and Alexandria (O&A;) railroad to connect to the farms in the upper Rappahannock River watershed in the Piedmont. Alexandria intercepted the trade in wheat and other products that might have gone down the Rappahannock River to Fredericksburg.

To capture even more business that might go to Maryland or Pennsylvania, Alexandria also built the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H;) railroad into Loudoun County. The intent, evident in the name of the railroad, was to reach the coal fields of Hampshire County. Extension across the Blue Ridge and Shenandoah Valley would have offered an alternative route for companies that were shipping coal via the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O;) Canal to Georgetown. The railroad would carry coal directly to Alexandria, so the city's merchants would not have to count on the Alexandria Canal to profit from that trade.

after the Civil War, the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H;) railroad reached only to Round Hill

Source: Library of Congress, Map of northern Virginia (1894)

Alexandria investors built a third line, the Manassas Gap Railroad through the Blue Ridge at Manassas Gap. The Manassas Gap Railroad expanded Alexandria's connections into the Shenandoah Valley, attracting trade away from Baltimore and Georgetown.

At Front Royal, rafts and boats bringing iron "pigs," lumber, and farm products on the Shenandoah River could shift their goods to the Manassas Gap railroad. The railroad was more cost-effective than the old approach, floating further downstream to Harpers Ferry, the C&O; Canal, and ultimately Georgetown.

the Manassas Gap Railroad was constructed in the 1850's through the low points in the Blue Ridge (Thoroughfare Gap in the east near Haymarket, then across Fauquier County to Manassas Gap in the west near Front Royal) to link Alexandria with the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents

The recession or "financial panic" in 1857 forced Alexandria merchants to truncate plans to build a more-expensive Manassas Gap line. The original design was to build an independent, second track roughly parallel to the Orange and Alexandria (O&A;) from Alexandria to Manassas, before turning west to cross the Blue Ridge.

Without the financing after the recession, the Manassas Gap rail line was joined to the Orange and Alexandria at an insignificant location. That rail junction, known as Manassas, became the focal point of the Union Army in 1861. Union generals planned to use the rail line to haul hay and other supplies for the army, as it marched "On to Richmond" in the first major military campaign of the Civil War.

Alexandria railroad network: AL&H; in purple, O&A; in green, Manassas Gap in blue, and RF&P; in white

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the route of the Washington and Atlantic Railroad and its connections (1883)

Notable, Alexandria merchants did not seek to build a railroad directly south to link up with the rail connection to the state capital at Richmond. The farm trade in Tidewater could use the Potomac River, and Alexandria did not seek to become a gateway for through freight traffic... so why build south? Alexandria had no direct railroad line to Fredericksburg until after the Civil War, when the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac (RF&P;) was extended north to eliminate the inefficient transfer or cargo/passengers to steamships on the Potomac River.

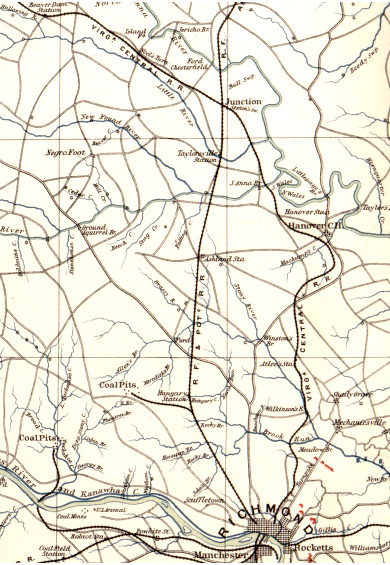

Richmond built a number of rail lines radiating in all directions. Even before the wood-burning locomotive was developed, rails (with cars pulled by mules) connected the coal fields of Chesterfield County with Richmond.

Richmond business leaders financed the Virginia Central Railroad (originally chartered as the Louisa Railroad) to draw business from the Rivanna River watershed in the Piedmont, and especially from farms located along the upper reaches of the North Anna and South Anna rivers (which had the option of trading at Ashland or Fredericksburg). The Virginia Central was originally aimed at Harrisonburg in the Shenandoah Valley, but the Blue Ridge was too high a barrier.

The route was curved south from Gordonsville to Rockfish Gap, after Charlottesville-area investors purchased sufficient stock in the railroad to affect the decision. To ensure the Virginia Central would connect with the Shenandoah Valley, the state spent 100% of the money required to carve tunnels through the Blue Ridge where I-64 now crosses Afton Mountain. The rail line stretched past Staunton before construction was interrupted by the Civil War.

Virginia Central in 1852

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant

The Richmond and Danville Railroad was built to attract trade to the James River from as far away as Halifax and Pittsylvania counties on the North Carolina border.

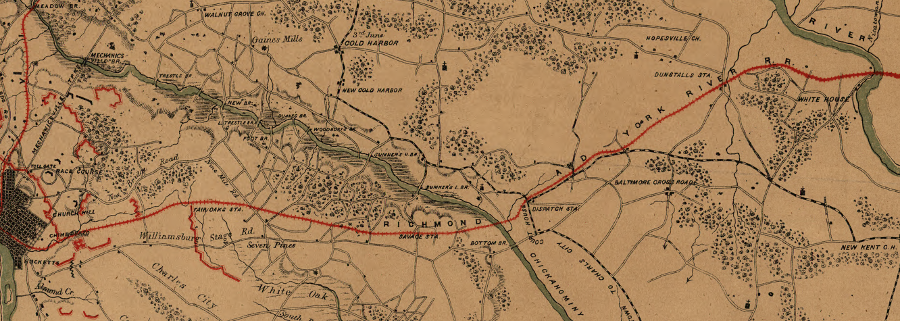

Richmond also built a rail line in the opposite direction. The Richmond and York River Railroad ran east to West Point. At West Point, at the confluence of the Pamunkey and Mattaponi rivers and thus the headwaters of the York River, the river channel was deeper. Richmond was competing with Norfolk and its naturally-deep harbor in hopes of controlling the trade in coal, wheat, and tobacco from the Appalachian Plateau/Shenandoah Valley/Piedmont.

the Richmond and York River Railroad crossed the shallow Chickahominy River and the Pamunkey River to reach deeper water at West Point (headwaters of the York River)

Source: Library of Congress, Military topographical map of eastern Virginia

West Point was considered as the terminus for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, before the line was extended from Richmond to Newport News

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the state of Virginia: showing the advantages of the harbor of West Point as an entrepot for emmigration and the shipment of the products of the southern and western states

Petersburg developed as the southern gateway to Richmond, via the RF&P.; The South Side Railroad connected Petersburg to the farms in the Appomattox River watershed, while the Petersburg and Roanoke railroad captured business from cargo shipped by batteaux and canal boats down the Roanoke River. After the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad was completed in 1858, Piedmont farmers shipping goods east via the South Side Railroad (and other customers west of Lynchburg, all the way to Bristol) had the opportunity to bypass the Appomattox River port at Petersburg and send goods directly to Hampton Roads.

Two cities in Virginia exist solely because of railroad junctions. Roanoke and Manassas grew from the start as towns where two railroads connected. Not every railroad intersection developed into a town - Doswell, for example, has remained a tiny crossroads community for 175 years.

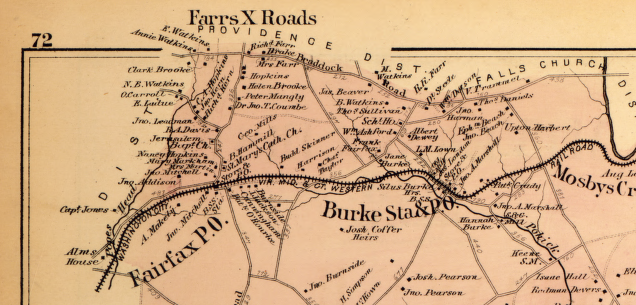

When railroads were constructed, physical geography normally trumped political geography. Some towns with county courthouses were completely bypassed, leaving a few centrally-located communities to stagnate. For example, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad followed the flattest path south and bypassed the court houses built on the tops of hills - Fairfax Court House (Fairfax), Brentsville (Prince William County), and Warrenton (Fauquier). The town of Fairfax coped by developing Fairfax Station, and Warrenton later managed to get a spur line connecting it to the railroad.

Fairfax Station (Fairfax P. O.) developed after the rail line bypassed Fairfax Court House (Farrs X Roads), to avoid climbing the hill

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins) (1878)

In Prince William County, however, Brentsville remained isolated from the population growth that the railroad stimulated. After several hotly-contested elections, Manassas was able to get the county voters to move the courthouse to combine the government center with the county's commercial center. After the move, Brentsville essentially disappeared off the map for 100 years, until local officials decided to restore the old courthouse as a historic site.

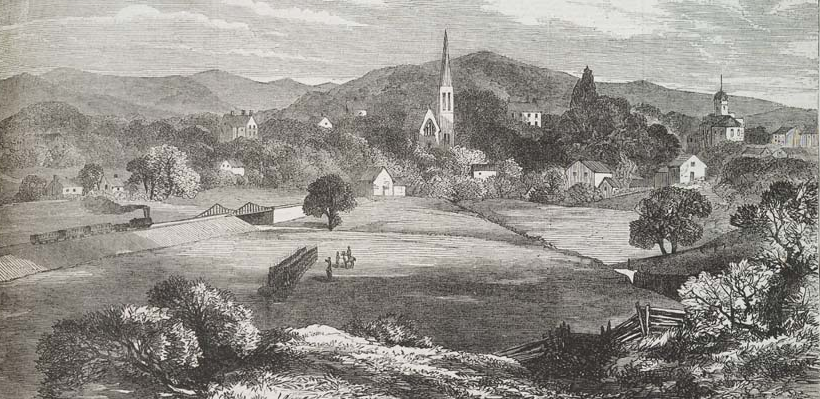

in 1852 the Orange and Alexandria Railroad built the Warrenton Branch, a spur from its mainline to the county seat of Fauquier County (Warrenton)

Source: Illustrated London News, The War in America: Warrenton, Virginia (May 30, 1863)

During the Civil War, the Confederacy was quick to utilize railroads, bringing troops from the Shenandoah Valley to Manassas in July 1861 and building the first military railroad between Manassas and the front lines at Centreville in early 1862.

In 1861, Robert E. Lee warned that the failure to connect the lines of the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad with the tracks of the Orange and Alexandria would be costly. When the Union invaded Alexandria in May, 1861, two locomotives were stranded on the AL&H. The Confederacy had to haul them overland across the hills of Fauquier county to Piedmont Station (today known as Delaplane) on the Manassas Gap Railroad.5

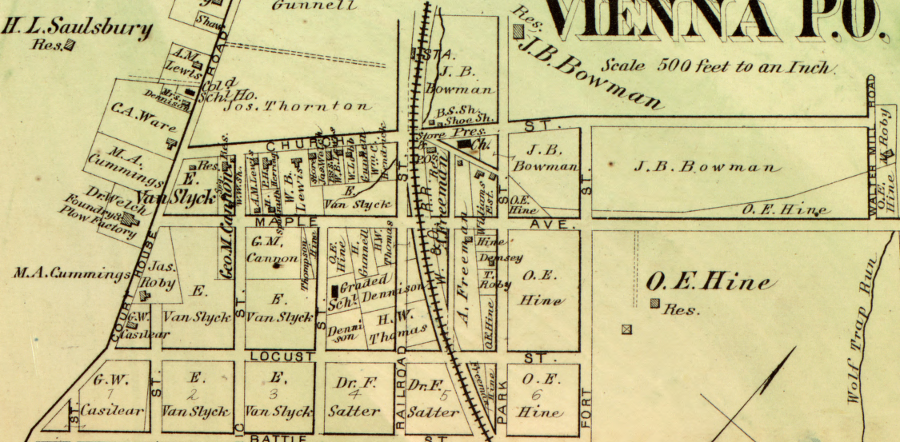

the rail line in Vienna was scene of an early Civil War skirmish in 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington (by G. M. Hopkins

The Confederacy had only one complete rail connection between the Mississippi River to Richmond. The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad linked Memphis to the Confederacy's capital, via Chattanooga. A second route from Vicksburg linked to other lines though Savannah, and then north to Richmond. However, that longer route had significant gaps, and boats had to be used to get people/material across Mobile Bay.6

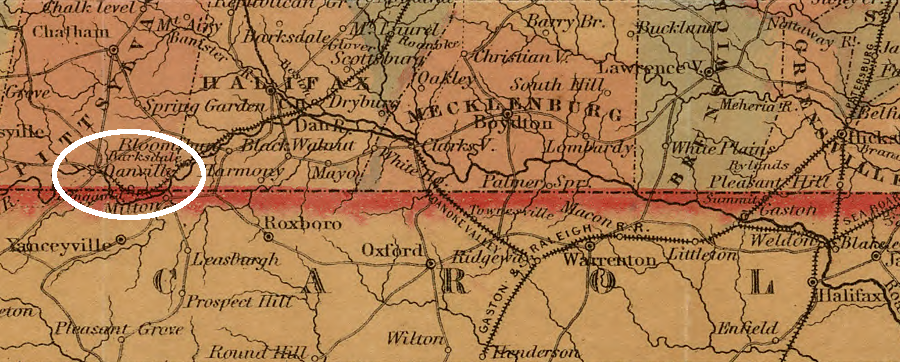

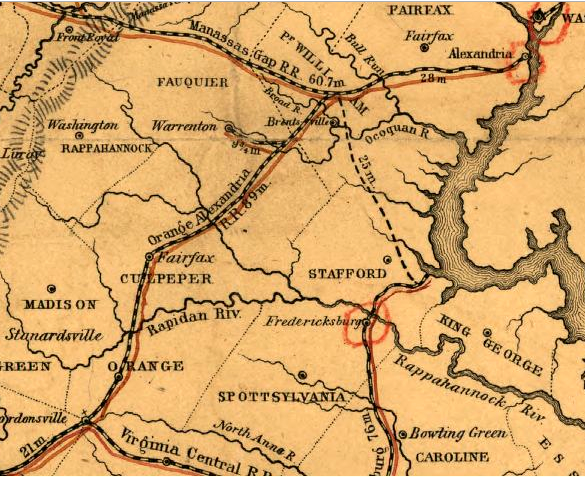

The obvious solution was to link the Richmond and Danville Railroad, which terminated at Danville, to the North Carolina Railroad at Greensboro. North Carolina strongly resisted the decision by Confederate officials to construct the Piedmont Railroad as a national project for military purposes. North Carolina wanted the trade from its Piedmont to go through Wilmington, rather than to any Virginia port.

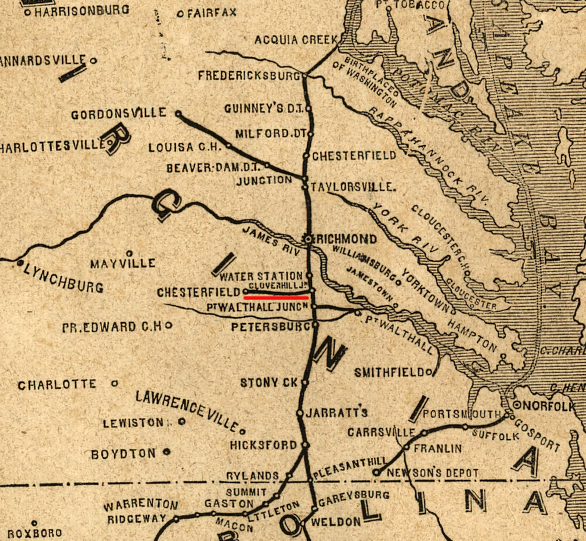

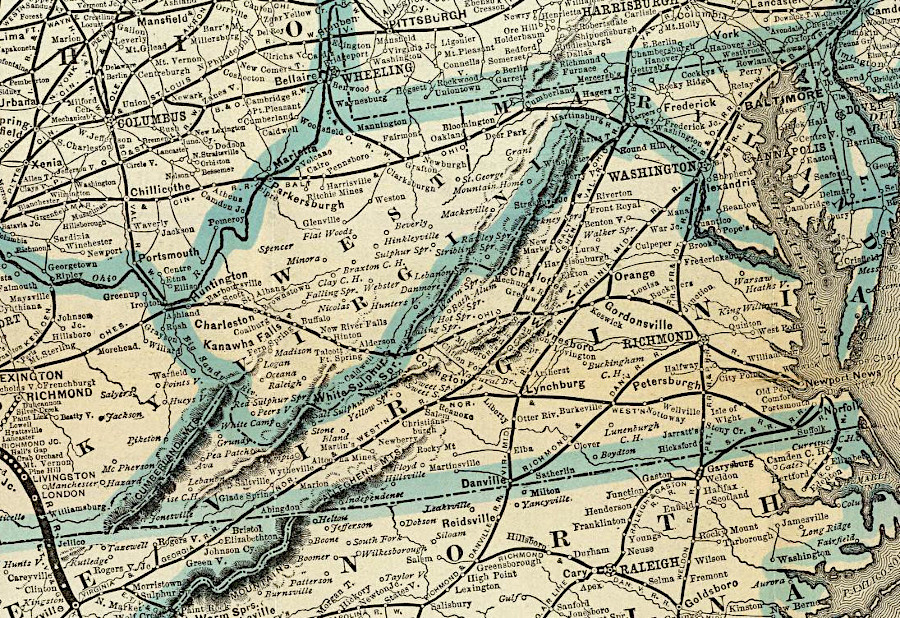

in 1855, Virginia rail lines connected Petersburg to eastern North Carolina, but the Richmond and Danville Railroad did not extend south from Danville

Source: Library of Congress, Colton's Virginia (by J. H. Colton, 1855)

The Confederate government ultimately rejected the state's rights concerns of North Carolina and forced construction of the Piedmont Railroad as a military necessity. As feared by North Carolina officials, after the Civil War farmers on the North Carolina Piedmont shipped cargo and bought goods from Petersburg and Richmond, costing North Carolina businesses some economic opportunities.7

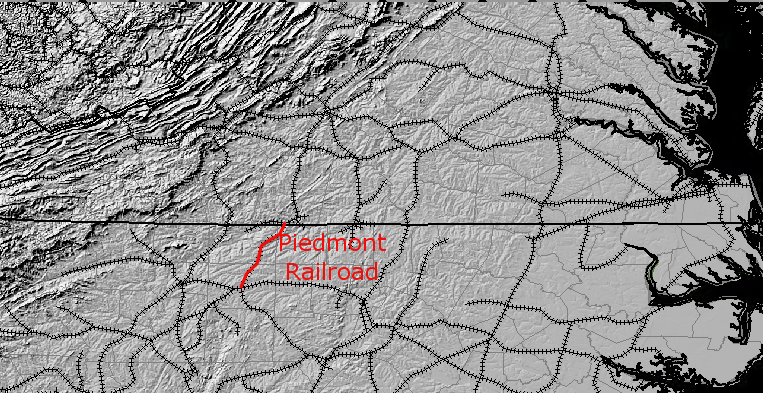

Piedmont Railroad, built during Civil War to connect Greensboro NC and Danville, VA

Source: The National Map, Seamless Server Viewer

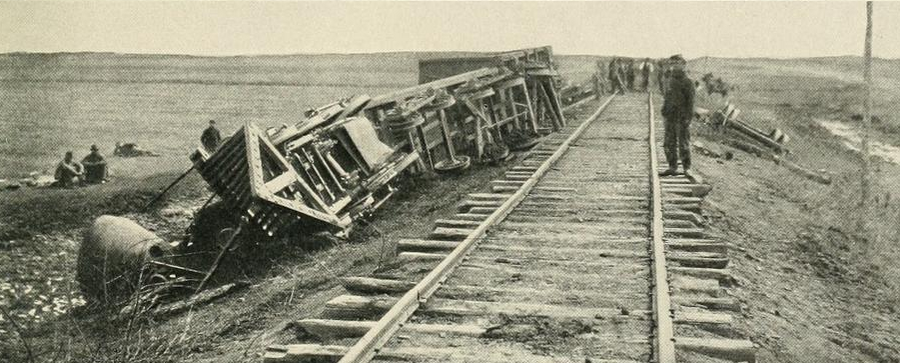

During the Civil War, Union forces targeted the rail network of the Confederacy, and converted some lines to use by the US Military Railroad to supply various armies trying to march "On to Richmond." Both sides destroyed railroad bridges to block the use of rail lines by the other side. The destruction of the Petersburg and Richmond Railroad bridge across the James River in Richmond was caused by the Confederate forces when they abandoned the capital in April, 1865.

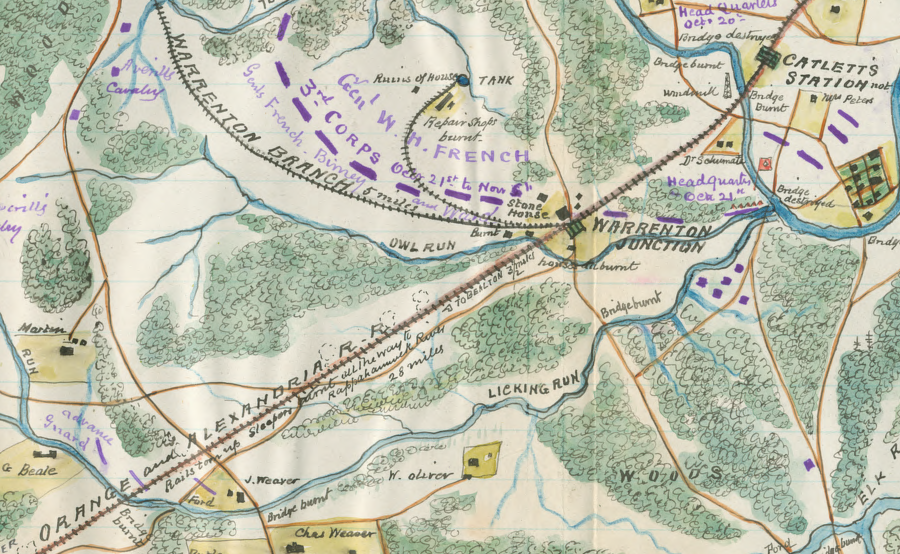

by 1863, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad stations and railroad ties near Warrenton had been burned, and the rails pulled up and twisted so they were unusable

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Warrenton Junction, Orange and Alexandria R.R., Virginia shewing destruction of R.R. by enemy, October 1863

most of the railroad infrastructure in Virginia was destroyed during the Civil War

Source: The Photographic History of the Civil War, After a Raid on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad (p.131)

after the Civil War, financing to restore the railroad system in Virginia came from Northern capitalists who linked competing lines together into interstate systems

Source: National Archives, Ruins of P.R.R.R. Bridge at Richmond, Virginia

After the Civil War, competing railroads finally built connections so freight and people did not need to be unloaded, "drayed" to a competing railroad's station several blocks to a mile away, then reloaded onto a different train. Railroads, when interchanging freight, finally built massive "yards" such as the old Potomac Yard in Alexandria. When interchanging passengers, union stations were built.

railroad gap in 1852 - no direct link

between Fredericksburg/Alexandria before Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the proposed line of Rail Road connection between

tide water Virginia and the Ohio River at Guyandotte, Parkersburg and Wheeling

After the Civil War, competing railroads finally built connections so freight and people did not need to be unloaded, "drayed" to a competing railroad's station several blocks to a mile away, then reloaded onto a different train. Railroads, when interchanging freight, finally built massive "yards" such as the old Potomac Yard in Alexandria. When interchanging passengers, union stations were built.

With the post-war shift in railroad ownership to non-Virginians, connections were built to move people and freight seamlessly across the state rather than just to feed traffic into the selected port cities of Alexandria, Richmond, Petersburg, and Portsmouth/Norfolk. In 1886, over the course of two days, all rail lines were converted to the Pennsylvania Railroad's 4 feet 9 inch gauge, and later standardized to 4 feet 8.5 inches.9

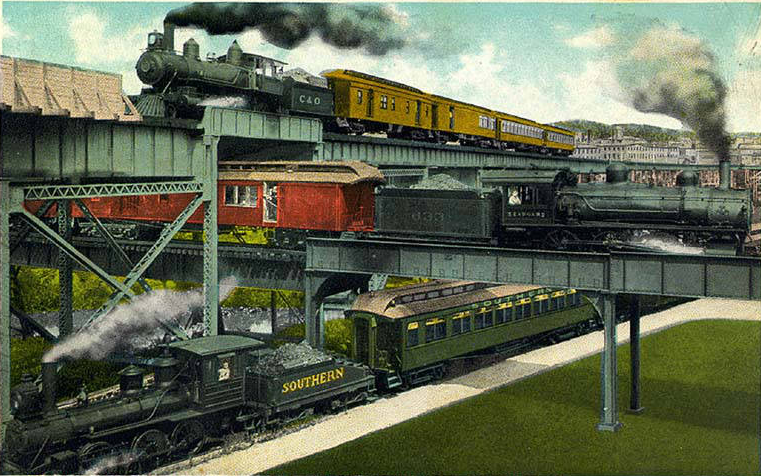

the Triple Crossing in Richmond is reportedly the only location in the world where three rail lines crossed at one location

Source: "Rarely Seen Richmond," Virginia Commonwealth University James Branch Cabell Library Special Collections and Archives, 'Is Two over one Railroad Fare?' (Sixteenth and Dock), Richmond, Va.

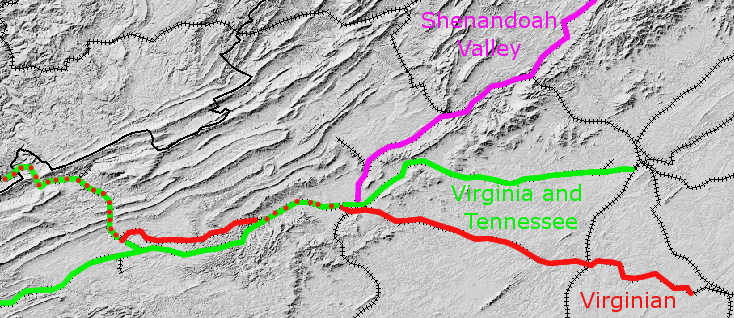

The Shenandoah Valley Railroad was the first railroad to go entirely through the entire Shenandoah Valley, from north to south. It was financed by Pennsylvania investors after the Civil War. Virginia was desperate for economic development, even if it involved a connection to the Pennsylvania Railroad and Virginia-based traffic could end up boosting business at Philadelphia.

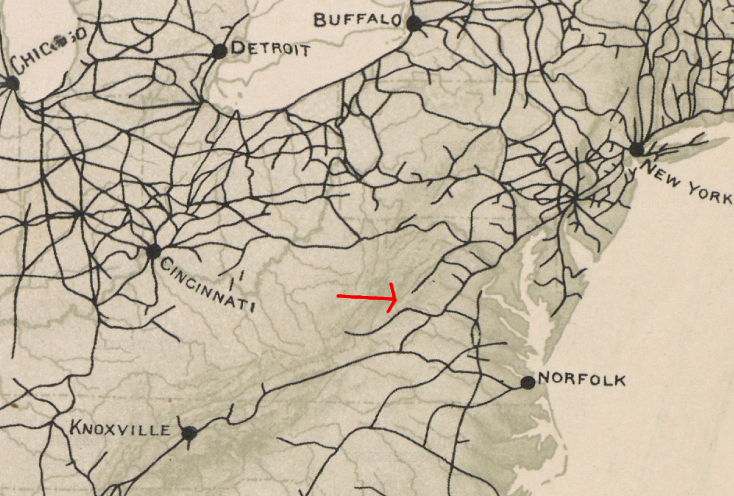

in 1870, Alexandria was connect to Bristol on the east side of the Blue Ridge by railroad - but on the west side of the mountains, there was still no rail line connection through the Shenandoah Valley linking Winchester to Staunton, or connecting Staunton to Tennessee

Source: Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, Railroads in Operation, 1870 (Plate 140a, digitized by University of Richmond)

After northern capitalists gained control of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad was built to connect it to the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Pennsylvania-based investors constructed a new rail line through the entire Shenandoah Valley, without needing to raise capital from Virginians interested primarily in steering traffic to a particular port. The new line ran on the eastern side of Massanutten Mountain. Traffic to Harrisonburg and other towns on the west side of Massanutten Mountain was projected to be less profitable than freight business from the iron furnaces/forges at Shenandoah, Glasgow, Vesuvius, and other locations near the Blue Ridge.

The Pennsylvania investors were willing to let local investors determine the southern terminus of the railroad, the junction where the Shenandoah Valley Railroad would unite with the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Big Lick property owners contributed right-of-way and funds, with John C. Moomaw delivering commitments to railroad officials in Lexington after a dramatic horseback ride. The consolidated Shenandoah Valley/Virginia and Tennessee railroads, renamed the Norfolk and Western (N&W), located its machine shops at the junction, which grew so quickly that the new city of Roanoke was called the "Magic City."10

the hamlet of Big Lick did not grow significantly when the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was built through the Blue Ridge, but boomed into the "magic city" of Roanoke when the Shenandoah Valley Railroad chose that site for its junction with the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad

Source: Library of Virginia, Lynchburg Tennessee Line Rail Road, Bureau of Public Works collection, BPW 538 (5)

Because railroads won the competition with canals, railroads were the key factor in determining where population would grow in Virginia until the rail network was completed around 1900. The success of railroads shaped the development of several urban areas in Virginia, especially Alexandria, Danville, and Roanoke, while the failure of railroads stunted population growth in the Shenandoah Valley.

railroads in Virginia, 1855 (note that Roanoke did not exist before the war)

Source: Library of Congress - Williams' commercial map of the United States and Canada with railroads, routes, and distances (1855)

The Norfolk and Western railroad quickly expanded into the coal fields of the Appalachian Plateau. It built westward, down the New River valley, into West Virginia to gain access to the coal mines. The Virginia Central, which had morphed into the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) after the Civil War, did the same and built west from Staunton into the coal fields. The N&W hauled its coal across Virginia to Norfolk, while the C&O built a new port at Newport News.

Until construction of the coal railroads into the Appalachian Plateau the 1880's, Virginia railroads were mostly farm-to-market transportation corridors, local connections linking the farms and small towns in the western part of the state to Fall Line ports and Norfolk in the east. Curiously, the coal business converted both the N&W and the C&O into rail lines dominated by one-way traffic to competing Virginia ports, echoing the original design of Virginia's freight railroads.

the Virginia railroad network in 1886, when all rail lines were converted to the Pennsylvania Railroad's 4 feet 9 inch gauge

Source: David Rumsey Map Collection, Map of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and its connections

only a few sections of Virginia (Appalachian Plateau, Northern Neck, Eastern Shore) are not expected to receive state funding for rail infrastructure upgrades

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, DRAFT 2013 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan Overview (p.25)

Many logging railroads were constructed as temporary lines. Costs to construct the roadbed was minimized by building narrow-gauge railroads, and by placing track directly on the ground or on wooden supports rather than bringing in a rock ballast. After commercially-valuable trees were cut and transported to the sawmill, the rails was removed and the area abandoned.

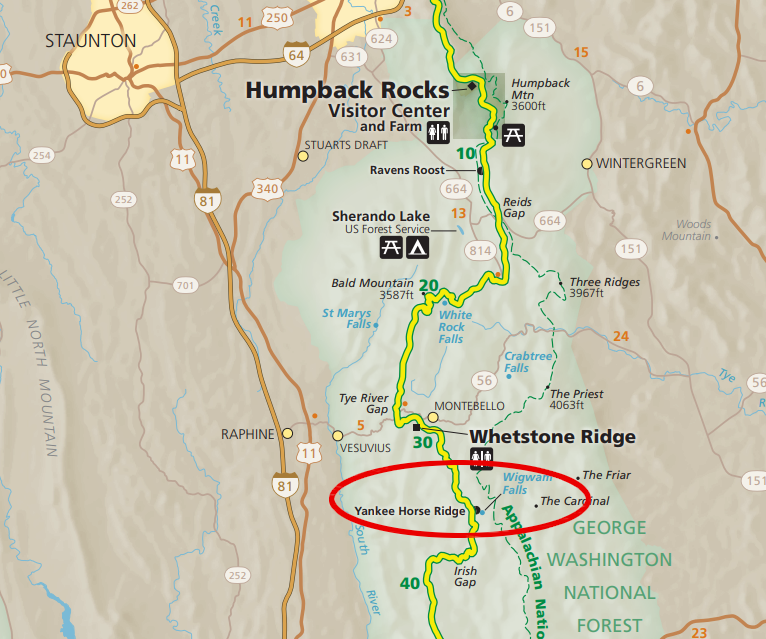

Today, the Blue Ridge Parkway commemorates the Irish Creek Railway built in 1919-1920. The Yankee Horse Ridge Trail includes a reconstructed 0.2 mile section of track, which was just a tiny part of the original 50 miles constructed by the South River Lumber Company.11

logging railroad heritage is interpreted at Yankee Horse Ridge Trail on the Blue Ridge Parkway

Source: National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway map

the Irish Creek Railway once ran for 50 miles

Source: Kipp Teague, old logging railroad exhibit, Blue Ridge Parkway

Since World War II, trucking and airline companies have successfully competed to peel away both freight and passengers from railroads. Railroads largely abandoned the business of transporting time-sensitive material, including perishable goods, to trucks traveling on free highways built with government funding.

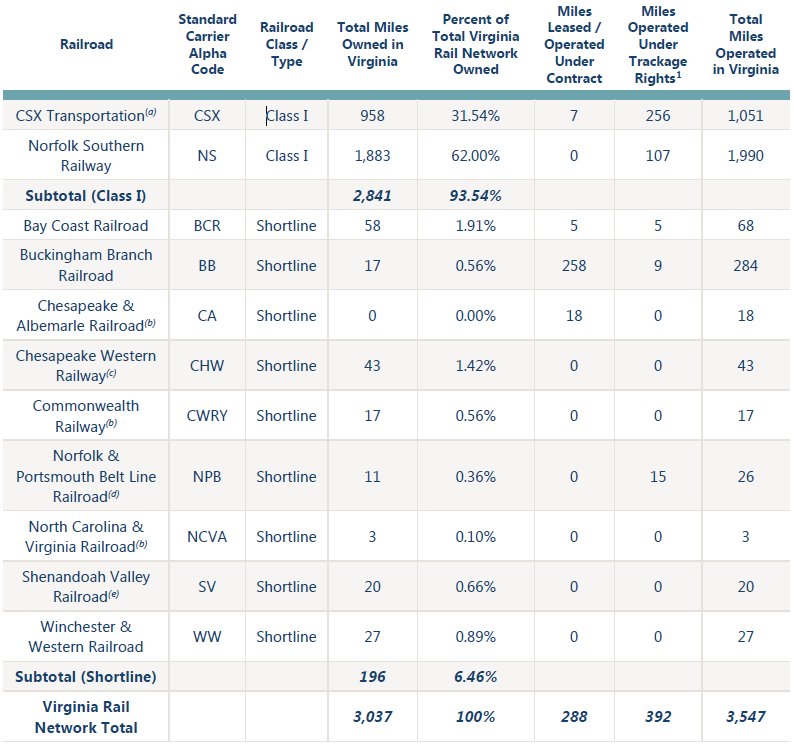

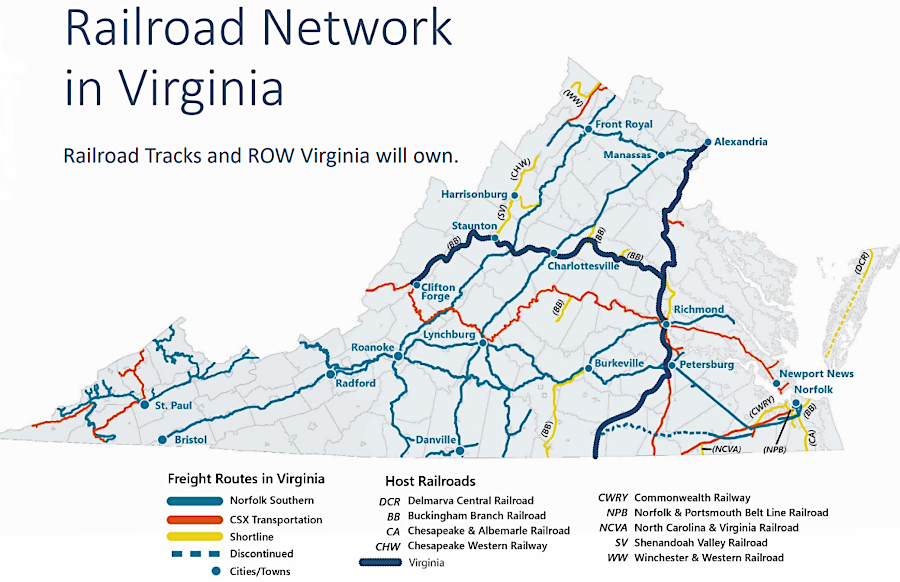

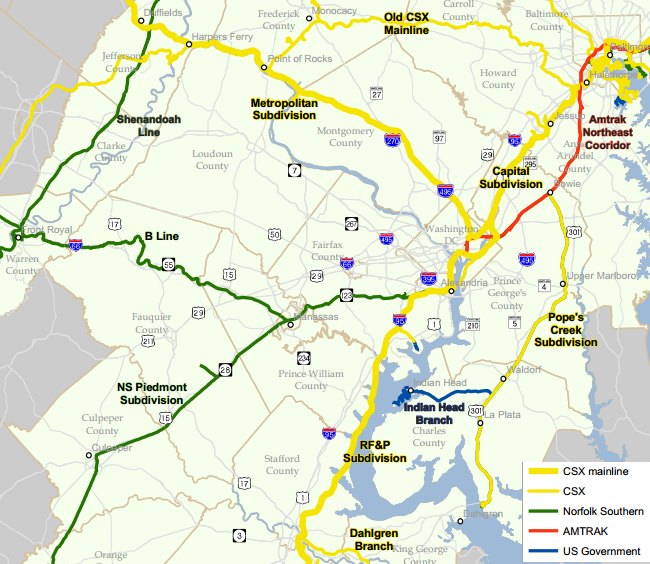

Today, Virginia has just two remaining Class 1 freight railroads, CSX and Northern Southern. Class 1 railroads carry 90% of freight, while shorter Class II and Class III railroads bring freight from isolated customers to the railyards of the Class 1 railroads for long-distance travel.

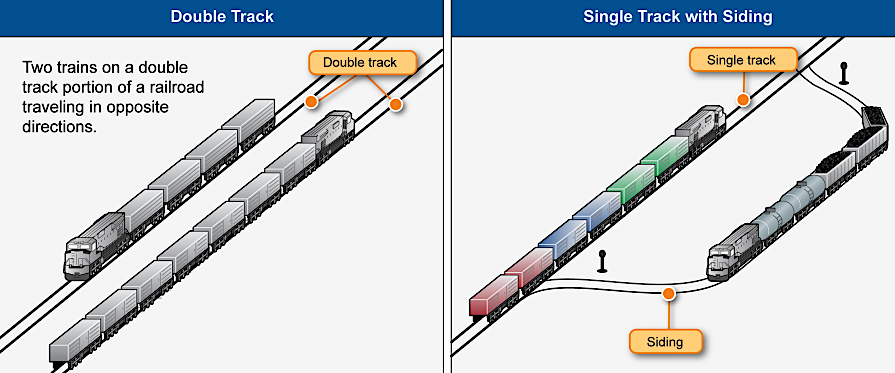

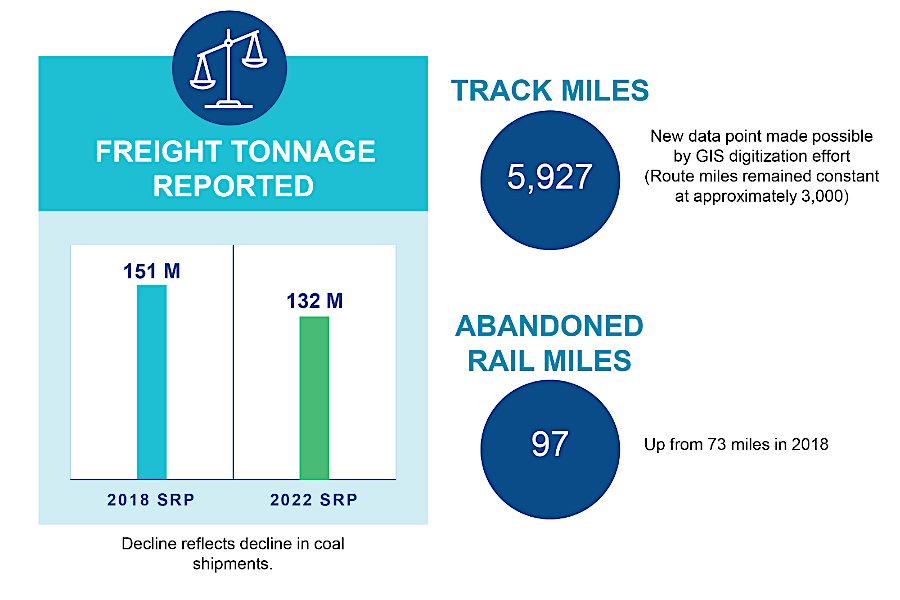

At its peak in the 1920's, Virginia had 4,703 miles of track. Since then, 1,600 miles have been abandoned to reduce maintenance and property tax costs, leaving just enough main line and sidings for trains to go past each other.

railroad mileage in Virginia, 2022

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), 2022 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan (Chapter 2)

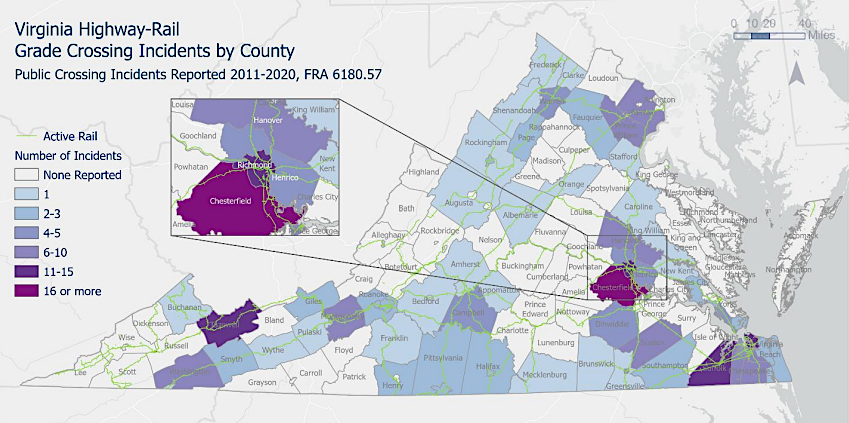

In 2022, there were 9,409 highway-rail crossings on the 3,037 miles of remaining track. Most (2,574) were private, serving just one landowner. Some had crossing gates to prevent train-car collisions, but 1,852 were public at-grade crossings where drivers had to stop, look, and listen in order to avoid being hit by a train. Between 2010-2023, 12 people died as a result of train-car collisions in Virginia.

State policy is to reduce the number of at-grade crossings. The shift to longer trains (over 8,000 feet) increased the time that a crossing was blocked, potentially limiting emergency medical personnel from getting to the other side of a track. However, longer trains also reduced the number of times that a train passed through a crossing and could potentially hit a vehicle.

Wise County has three times the number of highway-rail crossings that than suburban Chesterfield County, but less highway traffic and fewer incidents

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Virginia Grade Crossing State Action Plan (Figure 4) [data from Federal Railroad Administration, Highway-Rail Crossing Database Files and Reports]

Major segments no longer in use include the main line of the Virginian Railway between Abilene and Portsmouth, the Winchester & Western Railroad from Winchester to Wardensville (West Virginia), the Chesapeake Western Railway north of Mount Jackson, the Atlantic and Danville Railway, and the Seaboard Air Line between Petersburg and Ridgeway (North Carolina).

Some former track has been converted into hiking/biking trails. The Norfolk and Western Railway's Abington Branch is now a popular recreational destination, the Virginia Creper trail.12

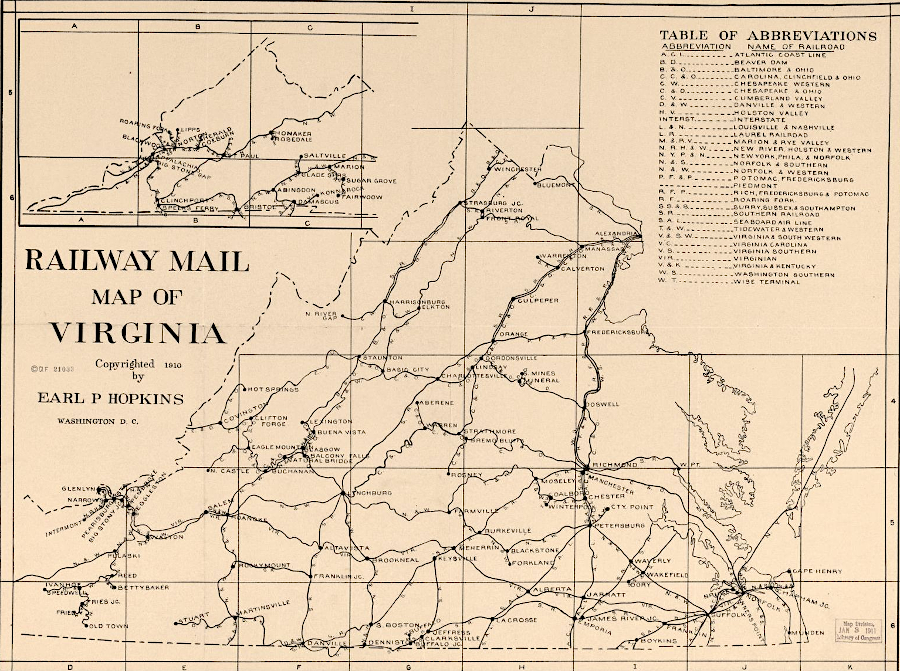

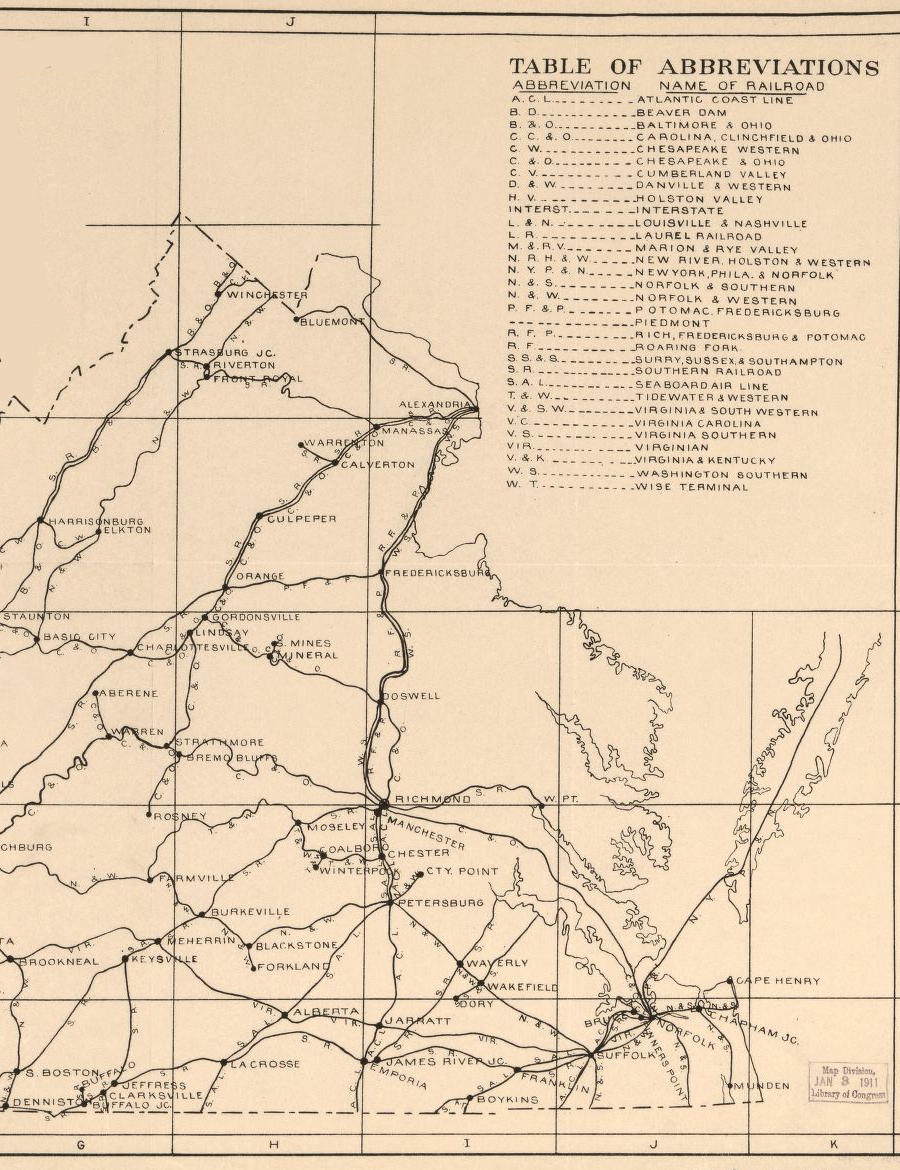

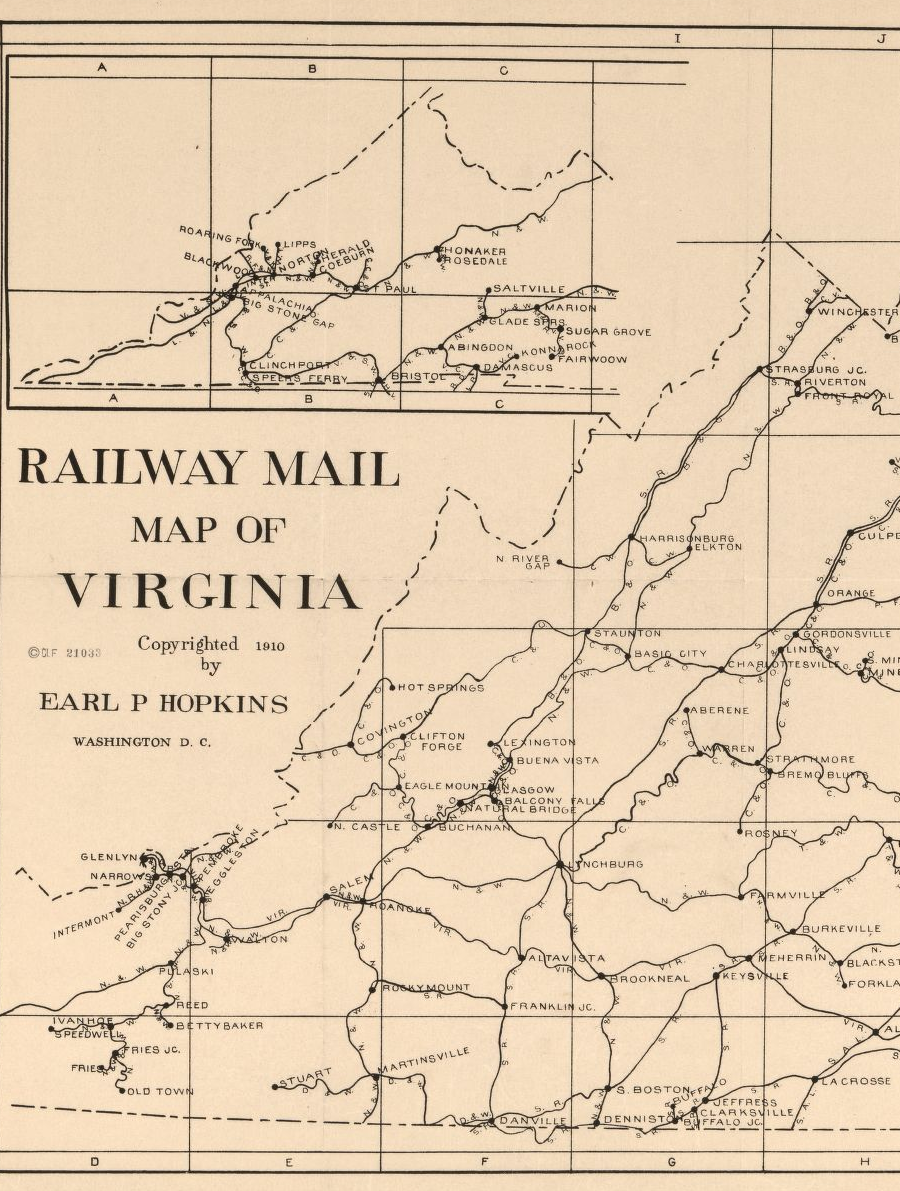

railroads in Virginia, 1909

Source: Library of Virginia, Railway mail map of Virginia

railroads in Virginia, 2013

Source: Draft 2013 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan

Several "short lines" such as the Buckingham Branch Railroad now carry local freight on lightly-used track sold off by the major railroads. The short line running freight trains on the Eastern Shore closed abruptly in 2019. A new short line agreed to provide service on the northern 15 miles of track, but it was unprofitable to maintain operations on the rest of the line to Cape Charles. The right-of-way, like so many abandoned stretches of track in Virginia, was suitable for just a rail-to-trail project.13

Railroads became more efficient by adopting Precision Scheduled Railroading operating model. Service had been inconsistent and unpredictable, because railroads traditionally waited until sufficient tonnage was assembled into a train before moving freight cars out of railyards towards customers. The alternative, frequent and regularly scheduled service, was viewed as too expensive.

Precision Scheduled Railroading reduced the time freight sat idle by assembling general-purpose trains, with different types of cargo, that were cost-effective to run more often. Departures were scheduled so the railroad network was balanced, with an equal number of trains going in opposite directions each day. That reduced the need to maintain extra equipment.

Train makeup was modified to "distribute power," placing locomotives in the middle and at the end of a train. so one crew in the lead engine could transport more cars. Labor costs were reduced by scheduling fewer trains, and by requiring crews to be available on short notice so trains would not be delayed if and engineer, fireman, or other member was ill.

railroads abandoned 1,600 miles of track in Virginia, but retained double tracked segments and sidings for trains to pass one another

Source: Government Accountability Office (GAO), Freight Trains Are Getting Longer, and Additional Information Is Needed to Assess

Their Impact (May 2019, Figure 1)

CSX was the first Virginia railroad to implement Precision Scheduled Railroading, in 2017. Thanks in large part to lower costs, railroad profits soared. However, worker frustration also soared due to the tight scheduling and lack of guaranteed time off, even for medical visits. A nationwide rail strike was averted only at the last minute in 2022.

Streamlining operations also included reducing the number of trailer-on-flat-car (TOFC) shipments. Trains loaded with double-stacked 53-foot containers could transport more freight, though the trucks at either end of a trip had to supply their own chassis. The strongest demand to retain trailer-on-flat-car service came from FedEx and UPS:14

Virginia still has passenger rail, via Amtrak and one commuter rail system in Northern Virginia (Virginia Railway Express). There is one heavy rail transit system in the state: Metrorail is operated by Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, with Blue, Yellow, Orange, and Silver lines in Northern Virginia. One light rail system, The Tide, carries passengers for 7.4 miles in Norfolk.

because pipeline capacity is limited, CSX trains have carried Bakken crude oil to the storage facility at the site of the former refinery in Yorktown

Source: US Department of Transportation, Crude oil

Freight lines are private corporations owned by stockholders. Today, all passenger rail operations are handled by public agencies such as Amtrak and Virginia Rail Express (VRE). The Virginia Department of Highways has morphed into the Virginia Department of Transportation, and the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation is a separate organization. Public funds are being invested to upgrade the privately-owned rail lines in order to increase passenger rail capacity.

Public funding for private railroads is also designed to increase business at the Port of Virginia, and to reduce highway truck traffic by diverting cargo containers. Railroads move people and cargo from Point A to Point B, increasing economic activity along their corridors and at their terminals.

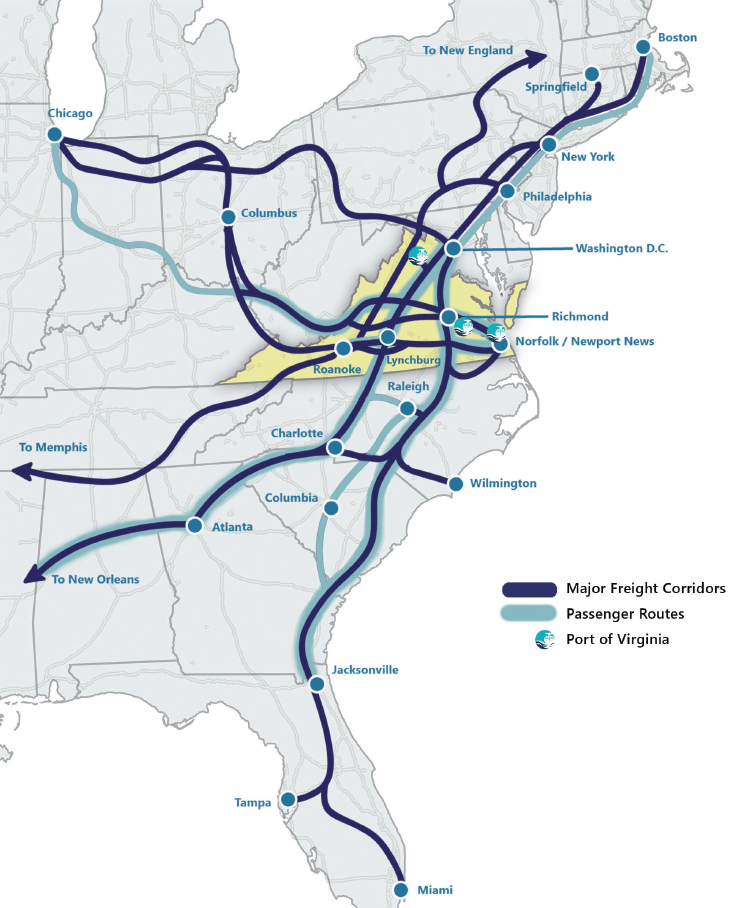

the Port of Virginia is located in the center of the rail network on the East Coast

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Virginia's Rail Network (2020)

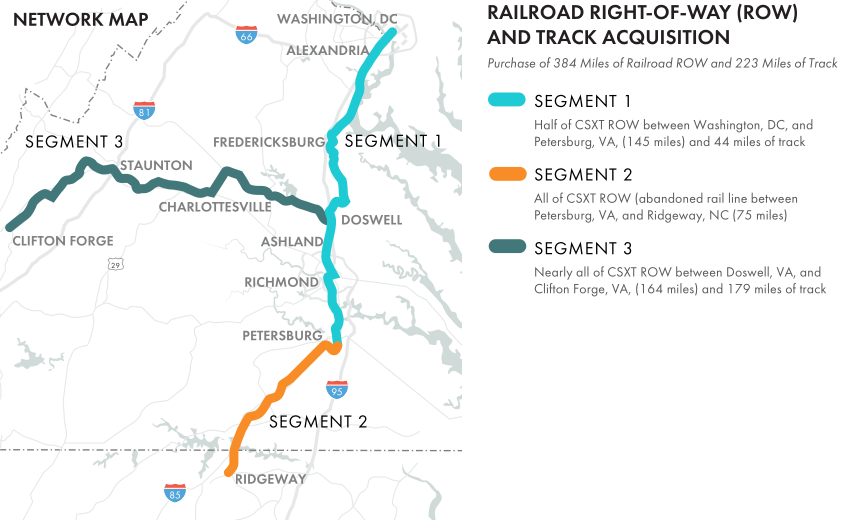

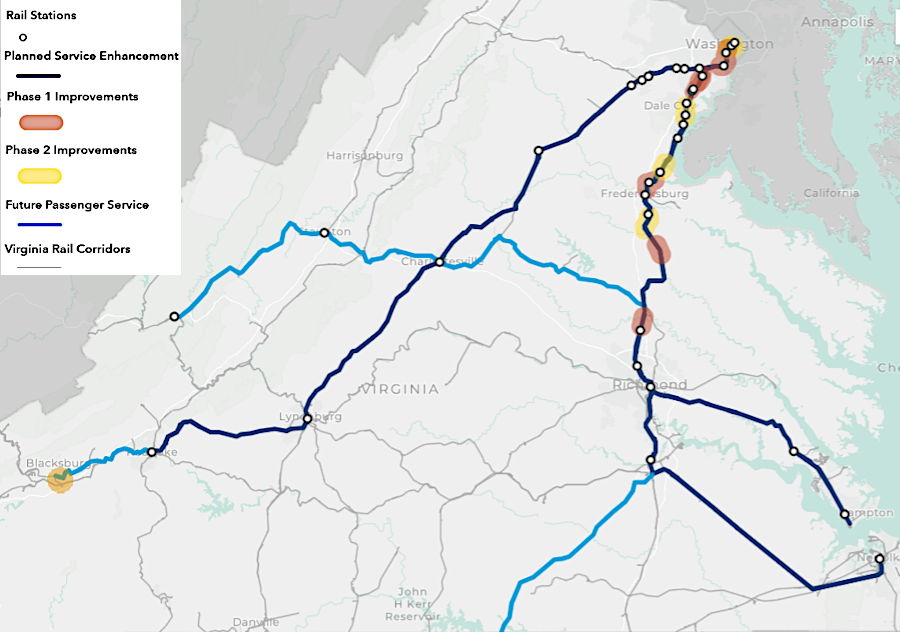

The most significant state investment in railroads since the Civil War was announced on December 19, 2019. Governor Northam revealed plans for the state to spend $3.7 billion to enhance passenger rail service. Virginia eventually agreed to purchase 384 miles of right-of-way and 223 miles of track owned by CSX, and planned to double Amtrak state-supported and Virginia Railway Express (VRE) Fredericksburg Line service by 2030. Weekend service by VRE was also planned on the Fredericksburg Line.

the "Transforming Rail in Virginia" initiative announced in 2019 eventually included plans for purchase of 384 miles of right-of-way and 223 miles of track from CSX

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Transforming Rail in Virginia

the Commonwealth of Virginia agreed to purchase 384 miles of right-of-way and 223 miles of track owned by CSX in the $3.7 billion Transforming Rail in Virginia initiative

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Transforming Rail in Virginia

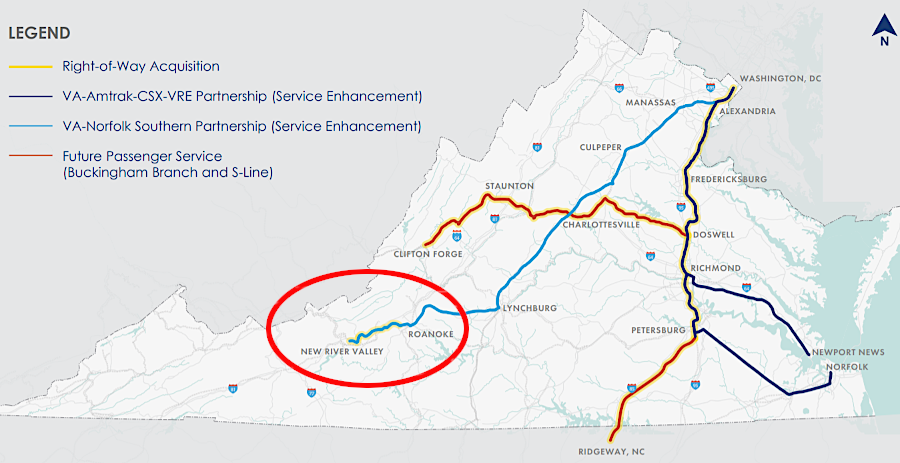

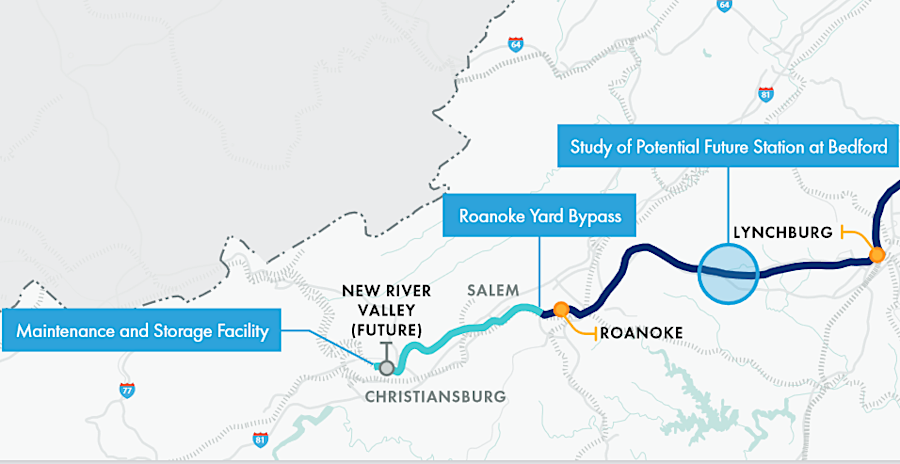

extending Amtrak service to Christiansburg was part of the statewide $3.7 billion Transforming Rail in Virginia initiative

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Transforming Rail in Virginia

The purchase of right-of-way between Petersburg and the North Carolina border enhanced the long-term potential to offer high-speed rail service to Raleigh, North Carolina. Acquisition of the CSX tracks between Doswell and Covington opened up the potential to add east-west passenger rail service, linking Richmond and Staunton.15

passenger rail service now links Roanoke and Norfolk to Washington DC, but east-west travel requires using a bus

Source: Library of Congress, I-81 Corridor Improvement Plan (Figure 18)

"transformation" was planned to occur in stages

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Transforming Rail in Virginia Web Application

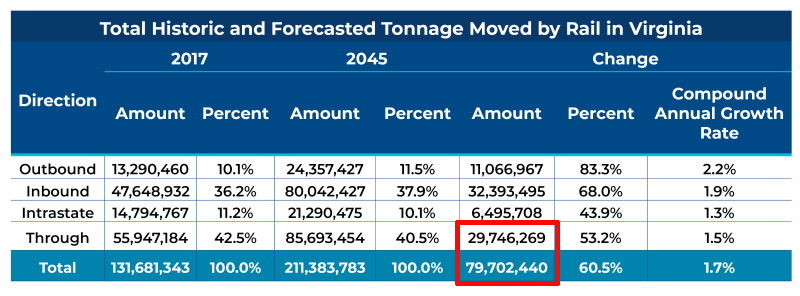

The 2022 Statewide Rail Plan anticipated that the tonnage of freight carried by rail would increase by 60% between 2017-2045, even as demand for thermal coal declined.

by 2045, state officials projected that over one-third of freight on trains would travel through the state without being loaded/unloaded in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Draft 2022 State Rail Plan (Chapter 1)

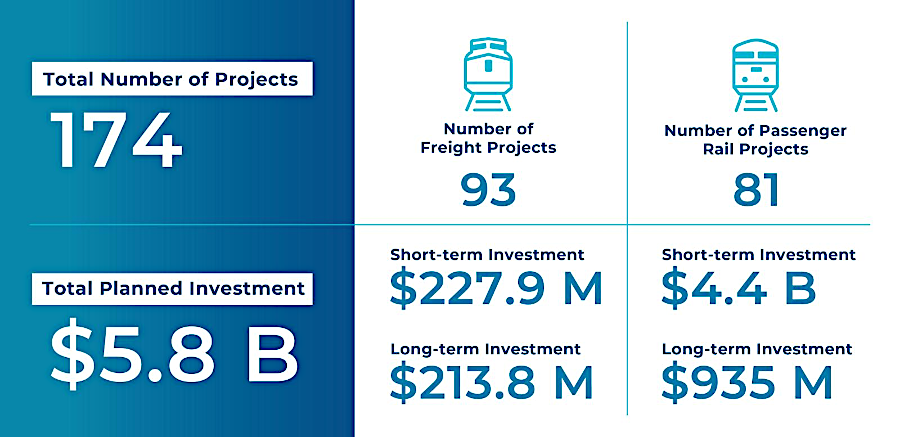

The plan proposed that Virginia invest nearly $6 billion to complete 174 rail projects. About half the projects would freight operations, but about 90% of the funding was directed towards passenger rail improvements. The Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) calculated that there were nearly 6,000 miles of track in Virginia. Some was in rail yards, some on routes that were double-tracked or with sidings. Altogether, there were 3,000 "route miles" traveled by trains across the state.

Virginia had nearly 6,000 miles of steel rails in 2022

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Draft 2022 State Rail Plan (SRP) (Executive Summary)

A particular focus was to increase the amount of cargo going to and from the terminals of the Port of Virginia via rail. That was expected to minimize the number of trucks on the highway and also minimize greenhouse gas emissions.

The 2022 plan reflected the costs and benefits of the Transforming Rail in Virginia initiative, in which the state acquired 193 miles of existing track and 220 miles of right-of-way to build new lines. The 2018 version of the plan had anticipated public investment of $3,9 billion in upgrading the railroads, but the 2022 plan proposed a $5.8 billion investment.16

the 2022 State Rail Plan proposed spending nearly $6 billion in state funds to upgrade rail infrastructure

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Draft 2022 State Rail Plan (Section 5.4)

The proposed investment in passenger rail service did include funding to construct a passenger station in Christiansburg/Blacksburg, but did not include the $535 million required to extend Amtrak to Bristol. The Draft 2022 State Rail Plan made clear that Virginia was waiting for Tennessee to plan for continuing Amtrak service from Bristol to Knoxville and Chattanooga, leading ultimately to a connection to Atlanta.17

the 2022 State Rail Plan did not include the additional $535 million required to extend passenger rail service from the New River Valley to Bristol

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), Program Highlights Between Manassas and the New River Valley

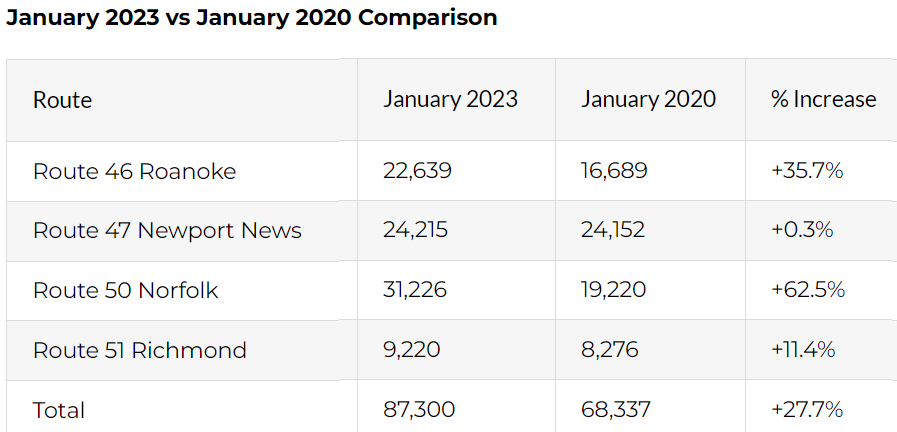

Rail passenger traffic climbed between 2020-2023, overcoming the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic.18

Virginia launched state-supported service in September, 2009, and passenger travel reached a peak in January 2023 despite COVID-19 disruptions

Source: Virginia Passenger Rail Authority, Ridership on Virginia's State-Supported Trains Continues to Set Records (March 10, 2023)

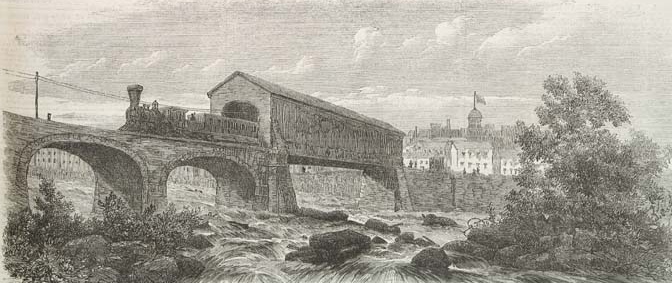

the wooden infrastructure of major railway bridges was protected from rainfall by roofs

Source: Illustrated London News, Railway Bridge Over the Rapids of James River (May 31, 1862)

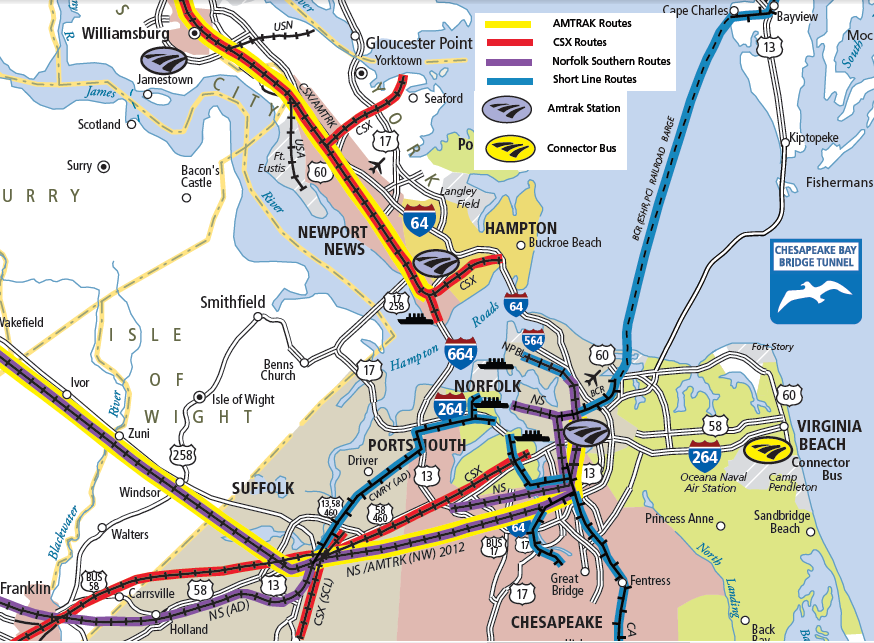

railroads in southeastern Virginia include both Class 1 rail lines (CSX and Norfolk Southern), plus four of the nine Class 2 "shortlines" in Virginia (Delmarva Central Railroad, Chesapeake and Albemarle, Norfolk and Portsmouth Beltline, and Commonwealth Railway)

Source: Virginia State Rail Map (2012)

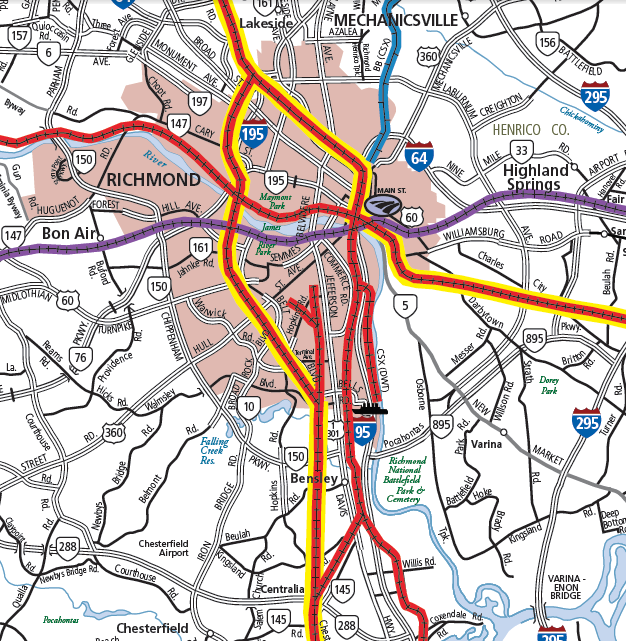

the only two railroads in Richmond today are the CSX and Norfolk Southern (with Amtrak for passenger service)

Source: Virginia State Rail Map (2012)

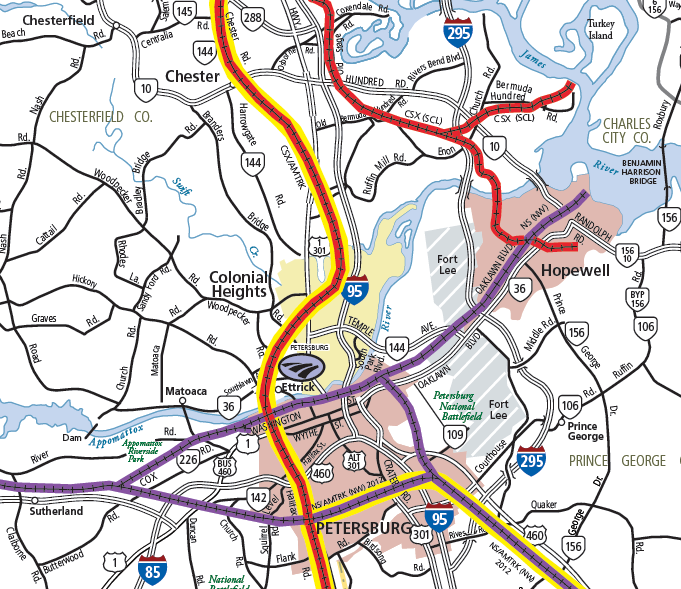

railroads in Petersburg

Source: Virginia State Rail Map (2012)

in addition to two Class 1 major rail lines, nine Class 2 rail shortlines provide last-mile service to selected customers and isolated regions in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, DRAFT 2013 Virginia Statewide Rail Plan Overview (p.36)

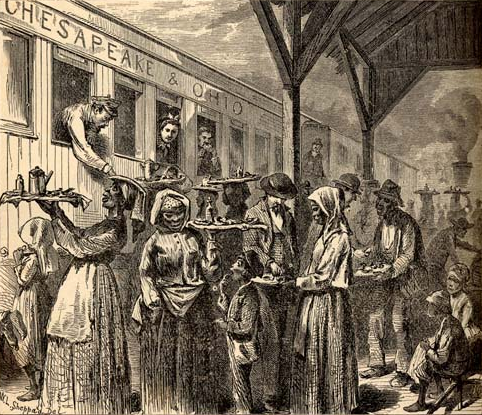

after the Civil War, the train station in Gordonsville was a mixing ground for both whites and blacks in the area

Source: University of North Carolina, The Great South; A Record of Journeys in Louisiana, Texas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland (1875)

Northern Virginia rail connections to the north

Source: National Capital Planning Commission, Freight Railroad Realignment Study (Figure 2-1)

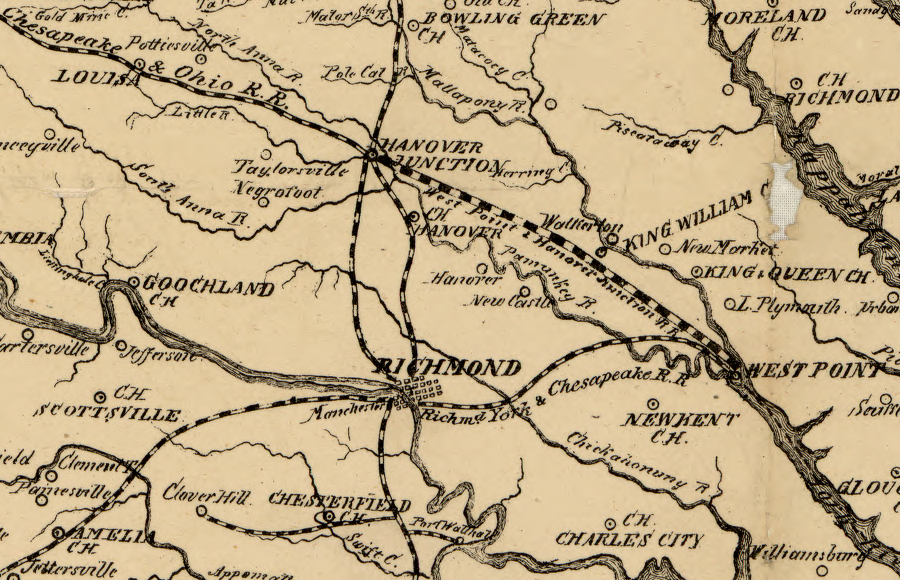

the Virginia Central Railroad build a line between Richmond-Hanover Junction (modern Doswell) in the 1850's, allowing it to compete more effectively with the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Atlas of the War of the Rebellion, Southeastern Virginia and Fort Monroe, Va. (1892)

the RF&P railroad was linked with the Richmond and Petersburg railroad in 1867 by constructing a tunnel under Byrd Street, to climb the hill next to the state penitentiary

Source: Library of Congress, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, Va. (Section Q, 1877)

major railroads of Roanoke

Source: US Geological Survey, Geo Science Eye Toolkit

historic Virginia Central/RF&P rail interchange at Doswell (Hanover County)

the Union Army sought to control key rail junctions in eastern Virginia during the Civil War, and the Confederate capital at Richmond was evacuated only after the capture of the rail hub of Petersburg

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the southern states of North America with the forts, harbours & military positions (1862)

railroad network in eastern Virginia, 1910

Source: Library of Congress, Railway mail map of Virginia (Earl P. Hopkins, 1910)

railroad network in western Virginia, 1910

Source: Library of Congress, Railway mail map of Virginia (Earl P. Hopkins, 1910)