Manassas Gap Railroad

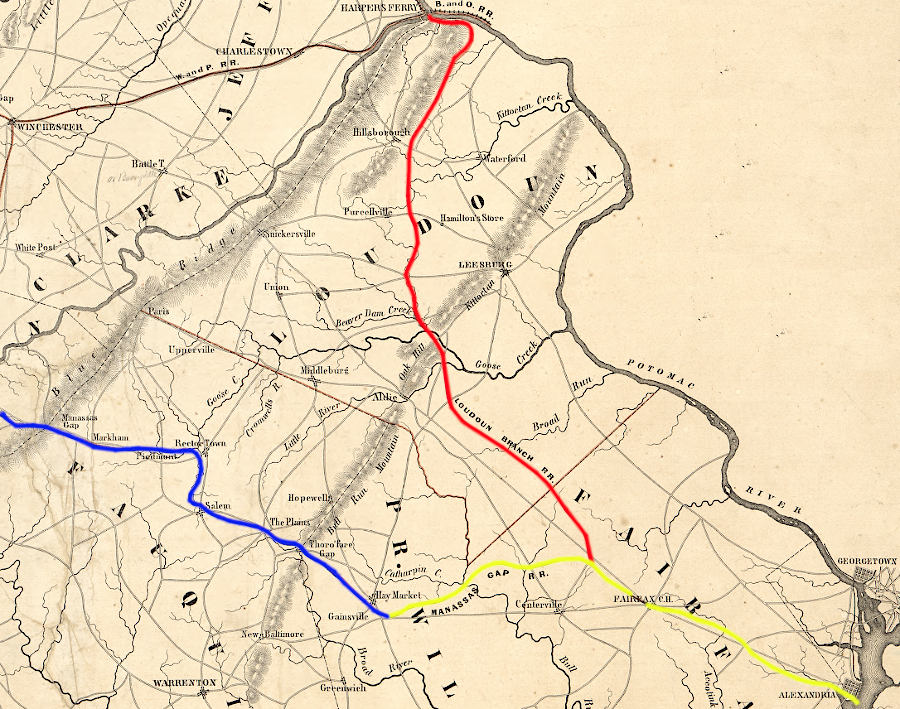

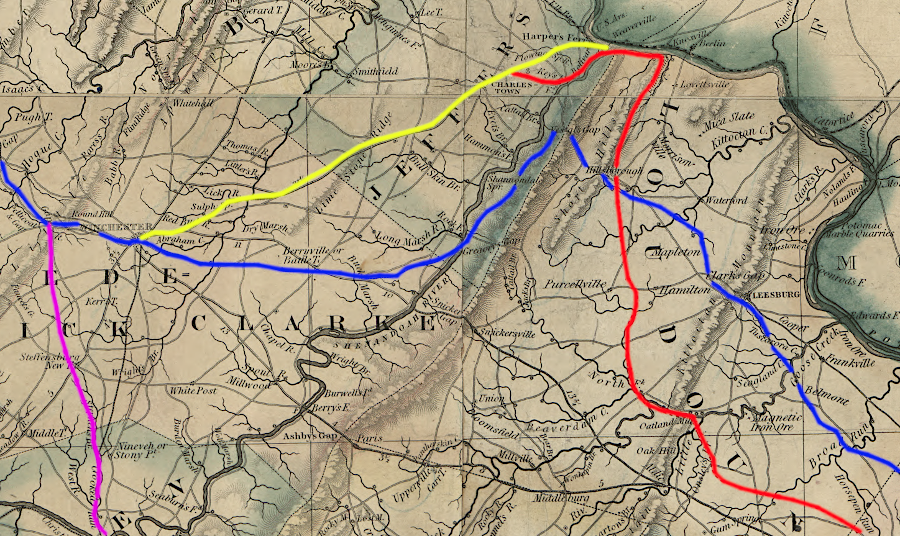

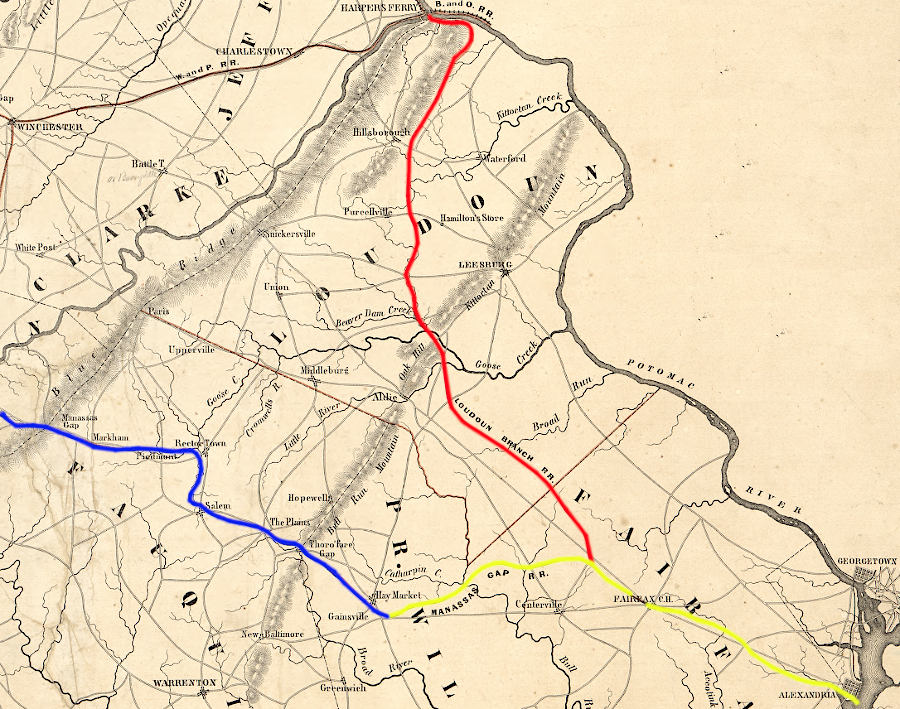

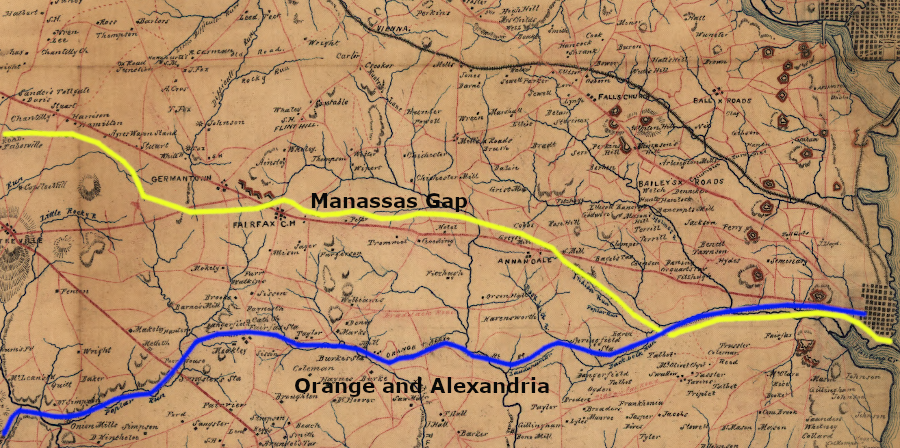

the Manassas Gap Railroad built track as planned west of Haymarket (blue), but planned track from Alexandria (yellow) with a branch to Harpers Ferry (red) was never completed

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Manassas Gap Railroad and its extensions (1855)

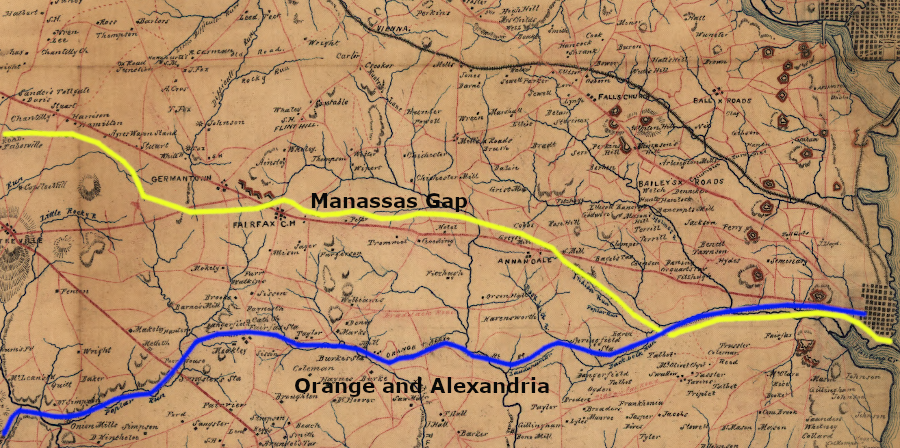

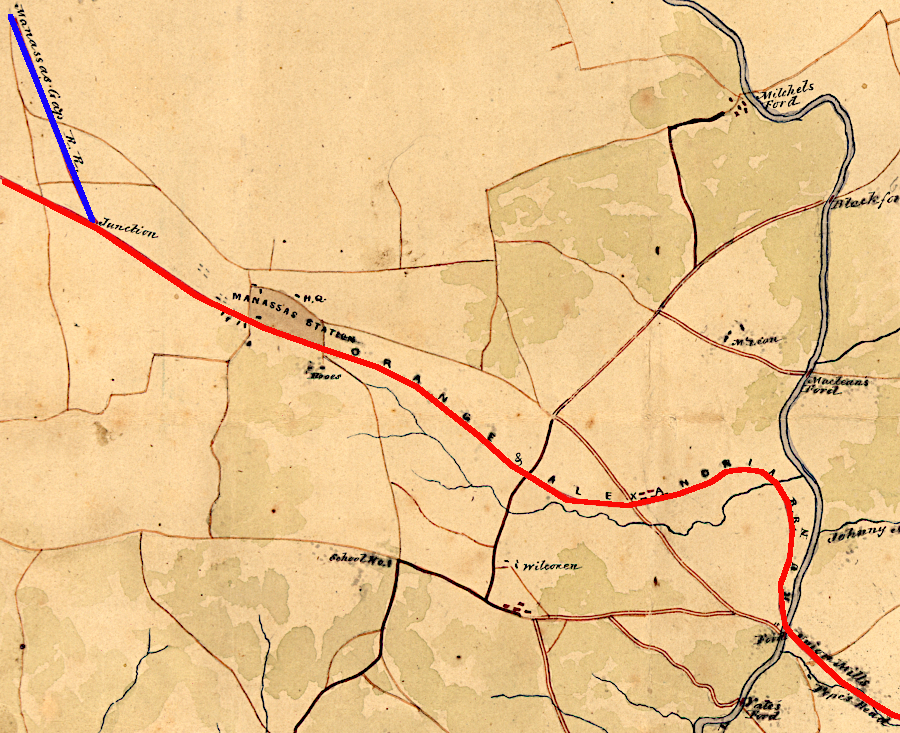

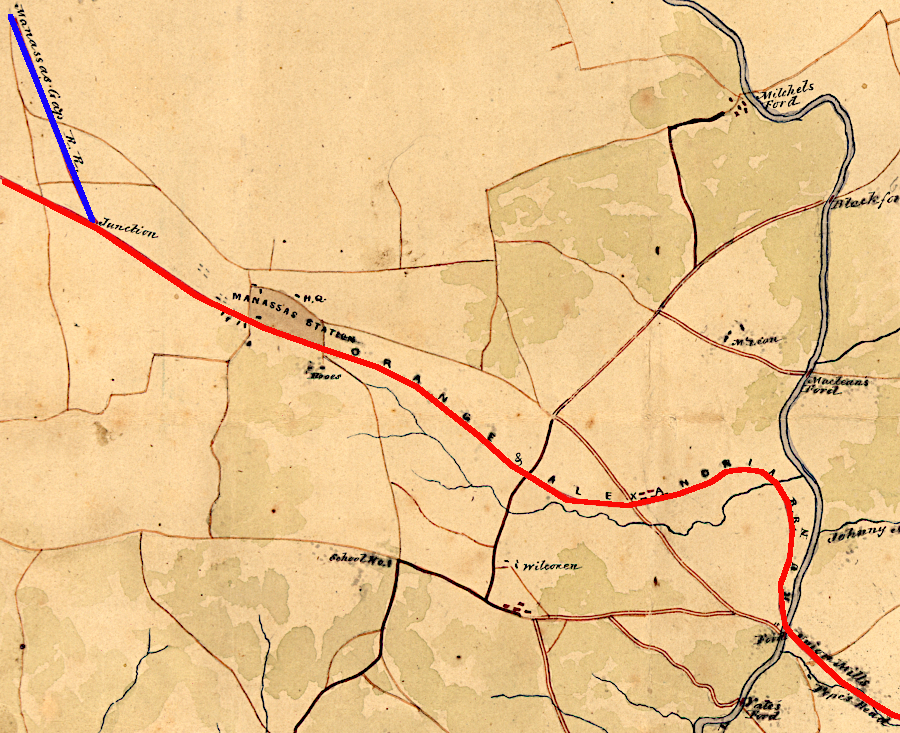

the Manassas Gap Railroad created Manassas Junction and paid the Orange and Alexandria Railroad to use the track to Alexandria

Source: Library of Congress, Map and profile of the Orange and Alexandria Rail Road with its Warrenton Branch and a portion of the Manasses [sic] Gap Rail Road, to show its point of connection (August Faul, 1854?)

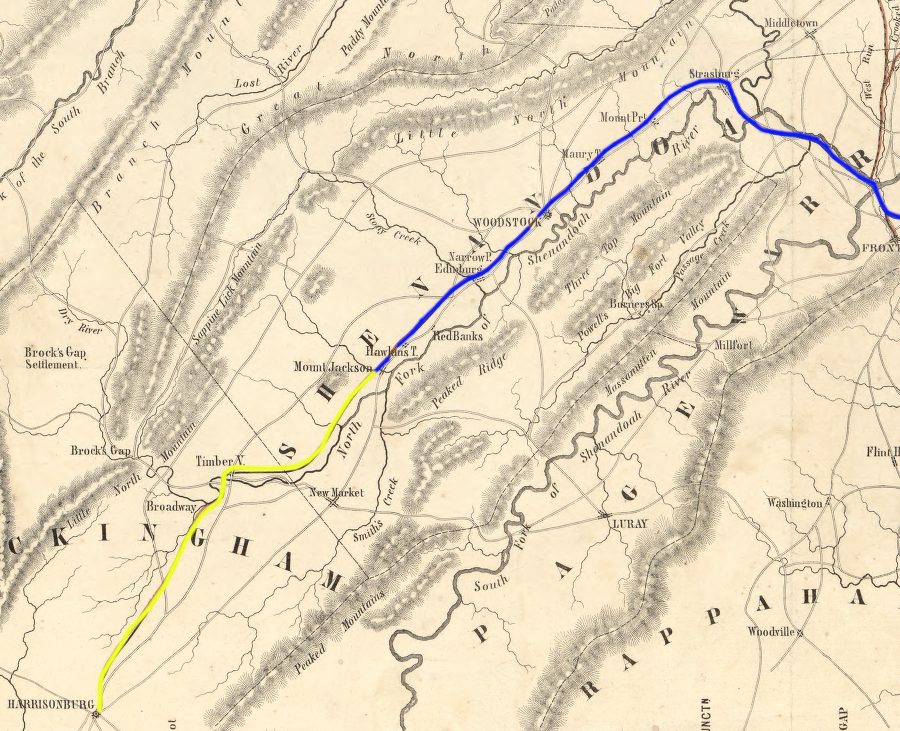

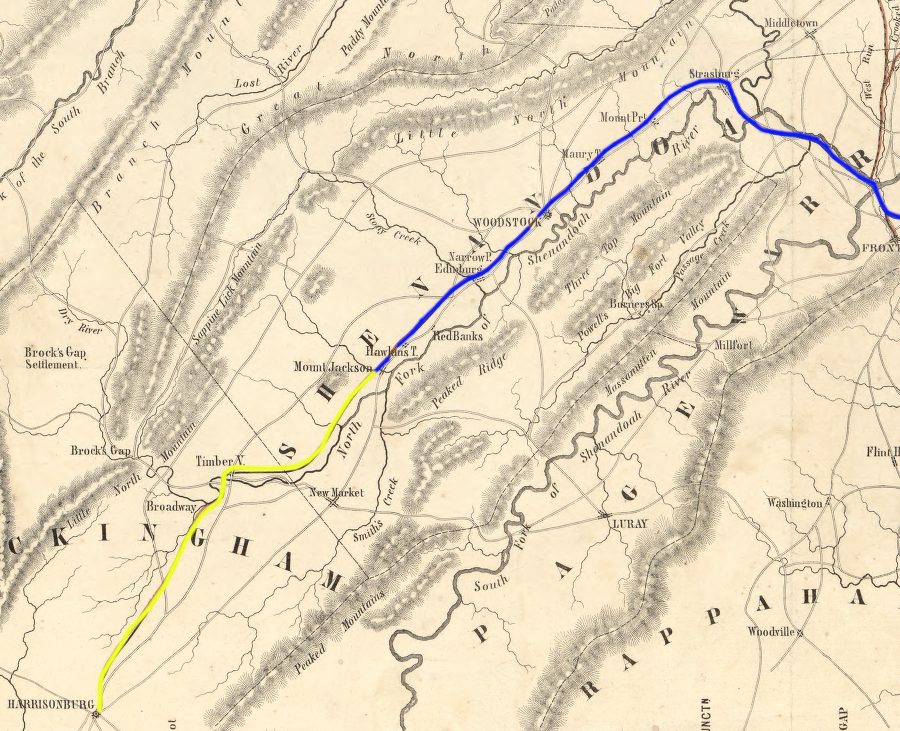

the planned track between Mount Jackson-Harrisonburg was not completed until after the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map and profile of the Orange and Alexandria Rail Road with its Warrenton Branch and a portion of the Manasses [sic] Gap Rail Road, to show its point of connection (August Faul, 1854?)

The Manassas Gap Railroad was chartered on March 9, 1850 by the Virginia General Assembly, three years after Alexandria was retroceded from the District of Columbia back to Virginia by the US Congress. The Board of Public Works bought 40% of the stock, creating another public-private partnership where the state subsidized "internal improvements" to reduce transportation costs to port cities. In 1853, the state percentage was increased to 60%.1

The Manassas Gap Railroad was authorized to build:2

- ...from some convenient point on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, through Manassas Gap, passing near the town of Strasburg, to the town of Harrisonburg...

Fauquier County landowners were the primary drivers for construction of the Manassas Gap Railroad. The first track was built west from a new junction with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad south of Bull Run, near a plantation know as Tudor Hall. The state charter required Manassas Gap trains to use the Orange and Alexandria Railroad - and pay fees for the trackage rights - in order to reach Alexandria.

In addition to Fauquier County landowners, the Manassas Gap Railroad was backed by those Alexandria merchants who wanted to attract trade from the Shenandoah Valley to their port on the Potomac River. Traffic was already coming to the city from the Shenandoah Valley, via the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal and the Alexandria Canal's extension to it. The canal connection was completed in 1843 when Alexandria was still part of the District of Columbia, and by 1850 it was clear that railroads were more competitive. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had been diverting traffic from Cumberland to Baltimore since 1842.

Building the Manassas Gap Railroad accelerated Alexandria's expansion of its transportation network across the Blue Ridge, to capture traffic that was moving via the Shenandoah River and Valley Turnpike to Winchester and Harpers Ferry. However, business and political leaders in Alexandria had alternative investment opportunities besides the Manassas Gap Railroad. In 1850, businessmen in Alexandria with capital were focused on funding construction of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad through the Piedmont to Gordonsville. They were also exploring financing the Alexandria and Harpers Ferry Railroad west to Winchester, a project that later became the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad.

The Virginia legislature authorized the Manassas Gap Railroad to build track from Manassas Gap to the west, but defined Harrisonburg as the endpoint.

in the Shenandoah Valley, Harrisonburg was the western destination of the Manassas Gap Railroad

Source: Library of Virginia, A map of the rail roads of Virginia (1858)

The 1850 charter blocked creation of a direct link to Winchester, where the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had gained control over the Winchester and Potomac Railroad and was sending trade to the rival port of Baltimore. Leaving a gap between Strasburg-Winchester with no rail service would prevent the Manassas Gap Railroad from intercepting trade from the northern part of the valley, around Winchester and Harpers Ferry.

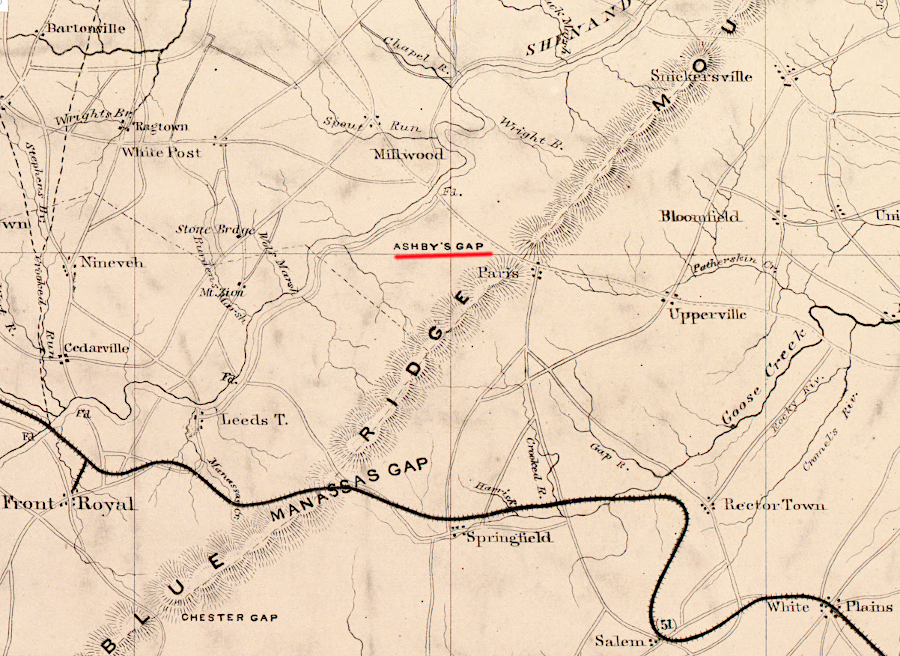

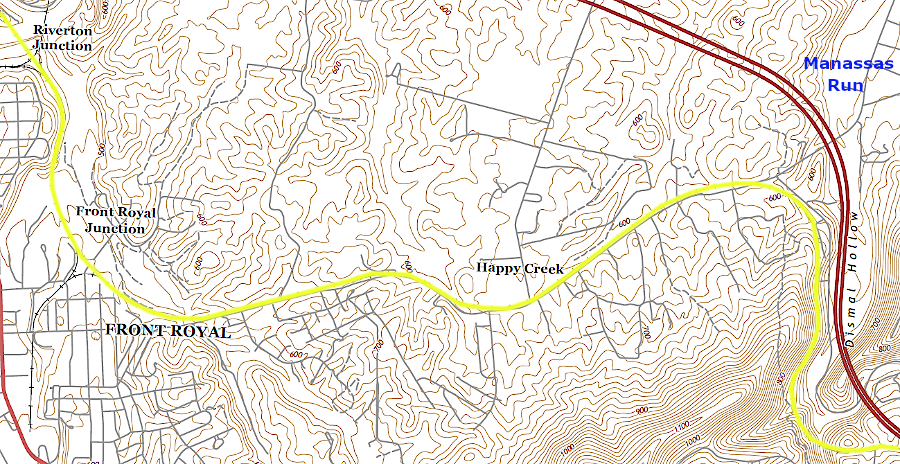

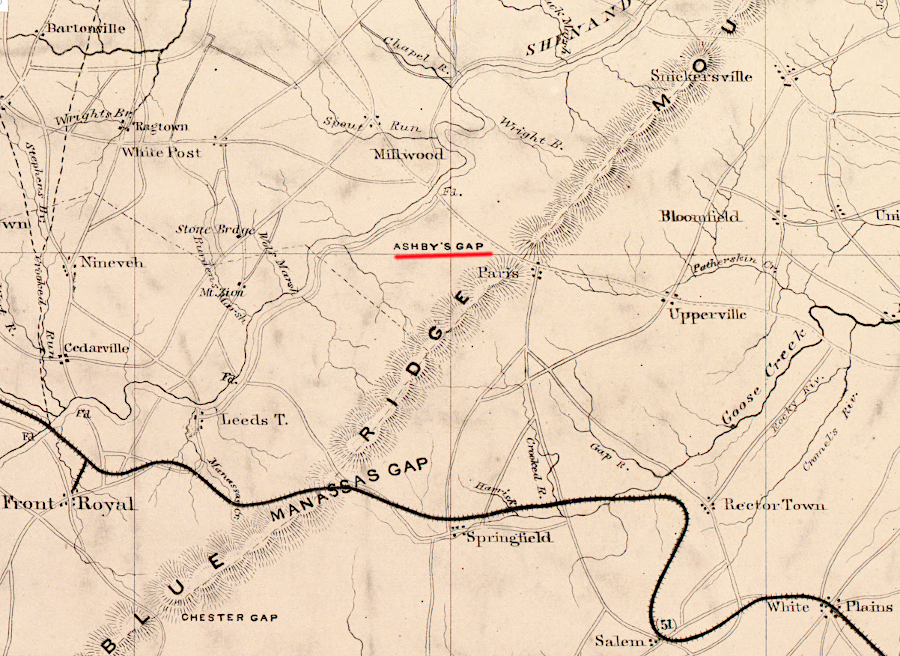

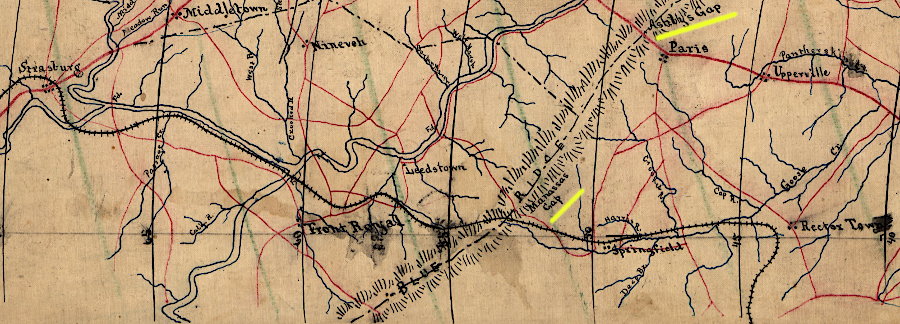

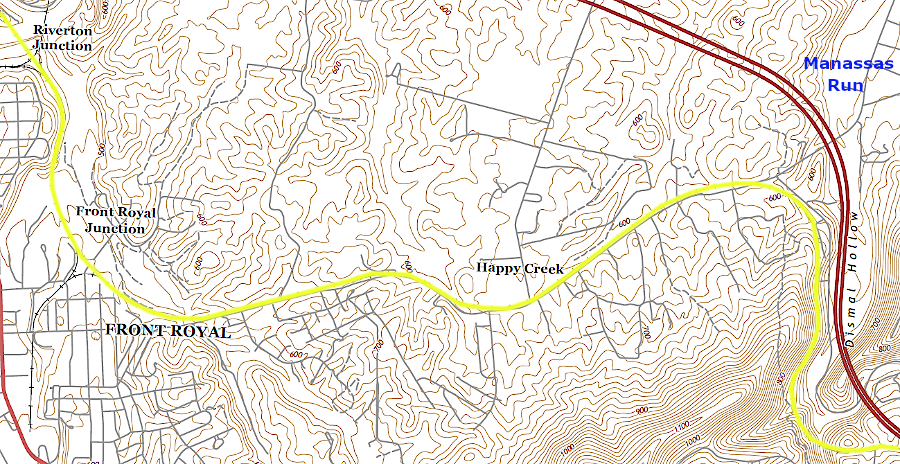

The charter specified a route through Manassas Gap, which was 937 feet high vs. 1,031 feet high Ashby Gap to the north. That route required track up Goose Creek to the border of Fauquier and Warren counties, then a drop from the watershed divide down Manassas Run to Riverton at the confluence of the North Fork and South Fork of the Shenandoah River.3

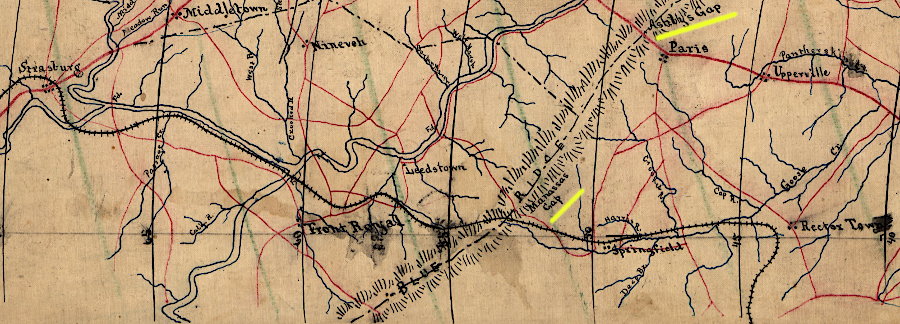

the Manassas Gap Railroad followed Goose Creek to Manassas Gap, rather than build through the higher-elevation Ashby Gap

Source: Library of Congress, Map of part of Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland

If the charter had authorized building through Ashby Gap where US 50 crosses the Blue Ridge today, then the Manassas Gap Railroad would have had the potential to capture more traffic moving north via the Shenandoah Valley to the Potomac River. However, building through a pass 94 feet higher would have been significantly more expensive.

There was enough business waiting where the South Fork and the North Fork of the Shenandoah River joined near Front Royal. Boatmen were floating freight from farms, mines, and iron furnaces past that point to Harpers Ferry. Even more trade could be captured for Alexandria by the new railroad at Strasburg, where wagons were carting wheat and other agricultural products on the Valley Pike towards Winchester and, from there, to Baltimore and Philadelphia.

the Manassas Gap Railroad built through Manassas Gap, which was 94 feet lower in elevation than Ashby Gap to the north

Source: Library of Congress, Map of portions of Virginia and Maryland, extending from Baltimore to Strasburg (186__)

at about 630 feet in elevation, the Manassas Gap Railroad turned west out of the Manassas Run valley towards Front Royal

Source: US Geological Survey, Map of portions of Virginia and Maryland, extending from Baltimore to Strasburg

Construction of the Manassas Gap Railroad started at Tudor Hall in Prince William County, an otherwise insignificant point on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad directly east of Manassas Gap. The investors funded construction of the railbed from Alexandria west, parallel to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, but a temporary connection at Tudor Hall would generate revenue from Shenandoah Valley traffic. The Manassas Gap Railroad had to pay for use of the Orange and Alexandria track between Alexandria and Tudor Hall, but that was expected to be a short-term expense until the Independent Line was completed. The Alexandria-based investors in the two railroads were business partners as well as competitors, so the temporary payments were seen as an acceptable expense.

the Manassas Gap Railroad did not plan a permanent connection to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, but did start construction using a temporary junction at Tudor Hall (red X)

Source: Library of Virginia, A map of the rail roads of Virginia (1858)

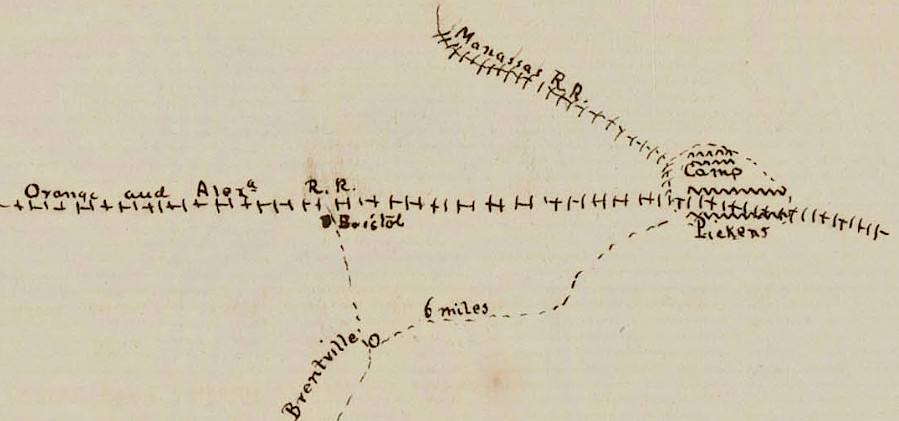

The railroad junction at Tudor Hall attracted development. The site evolved into Manassas Junction, and later became the focal point for the first major battle of the Civil War in 1861.

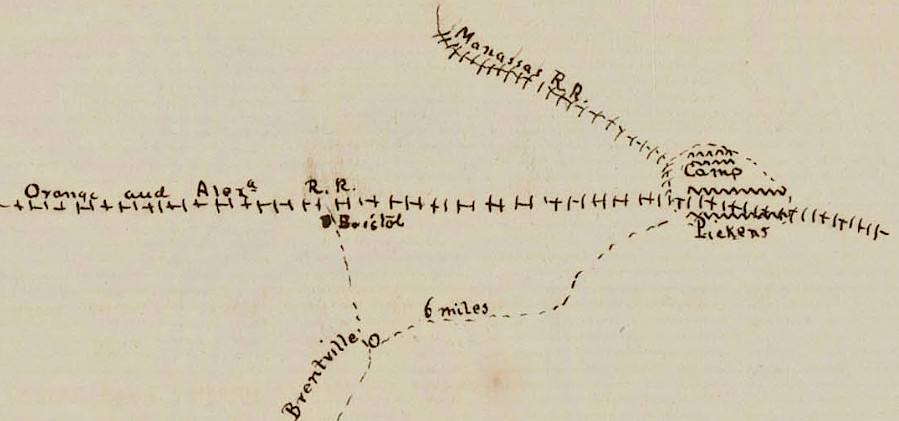

the Orange and Alexandria Railroad junction with the Manassas Gap Railroad made it a Union Army target in 1861

Source: National Archives, Rough Sketch of the Vicinity of Quantico, Virginia

The Manassas Gap Railroad started operating trains from Manassas Junction to Strasburg in 1854. The son of Chief Justice John Marshall, Edward Carrington Marshall, was the president at the time. Noting the different geology on either side of the Blue Ridge, he commented on the start of service:4

- The iron horse of Manassa this day takes its first drink of limestone water.

The investors in the two railroads were well acquainted with each other. The wealthy men in Fauquier who could afford to purchase stock viewed their railroad investment through a different lens than the Alexandria investors. Though initially allied with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, the Fauquier investors planned to become a competitor.

In 1853, the General Assembly authorized construction of a Manassas Gap Railroad branch through Loudoun County.

one proposal for routing the Loudoun Branch was to pass through Hogback Mountain north of Aldie, using the gap carved by Goose Creek

Source: Library of Congress, Loudoun County, Virginia [186-?]

The state legislature also authorized construction of an "Independent Line" going north from Gainesville to Alexandria, parallel to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Before the Independent Line was completed, the Manassas Gap Railroad had to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad to use the existing track between Manassas-Alexandria. Once the Independent Line was built, the Manassas Gap Railroad could stop making expensive payments to the other railroad for trackage rights.

the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad was meant to parallel only the far eastern portion of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, A map of Fairfax County, and parts of Loudoun and Prince William Counties, Va., and the District of Columbia

The far eastern portion of the two railroads, near Alexandria, would run close to each other going up the Cameron Run Valley past Holmes Run. At Indian Run, the Independent Line diverged north to Annandale. The business opportunity on that route included capturing trade from the Little River Turnpike, especially that portion which is now Route 236 from Annandale to Fair Oaks and US 50 west to Chantilly.

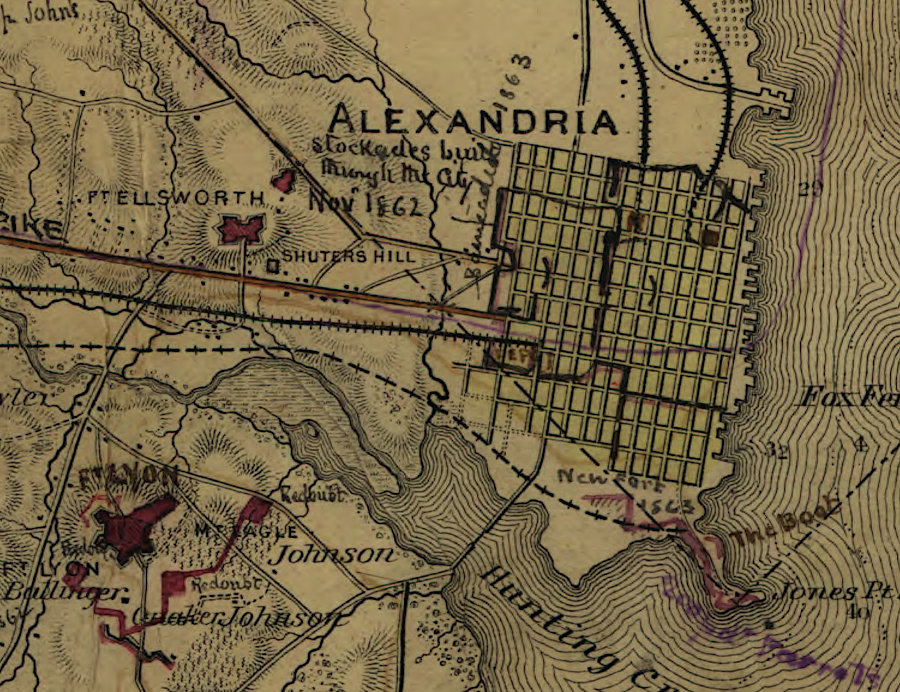

the planned Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad diverged from the route of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad at Indian Run

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of Washington, D.C., and vicinity. Showing the Union forts and defences built 1861-3. (Robert Knox Sneden, 1861-65)

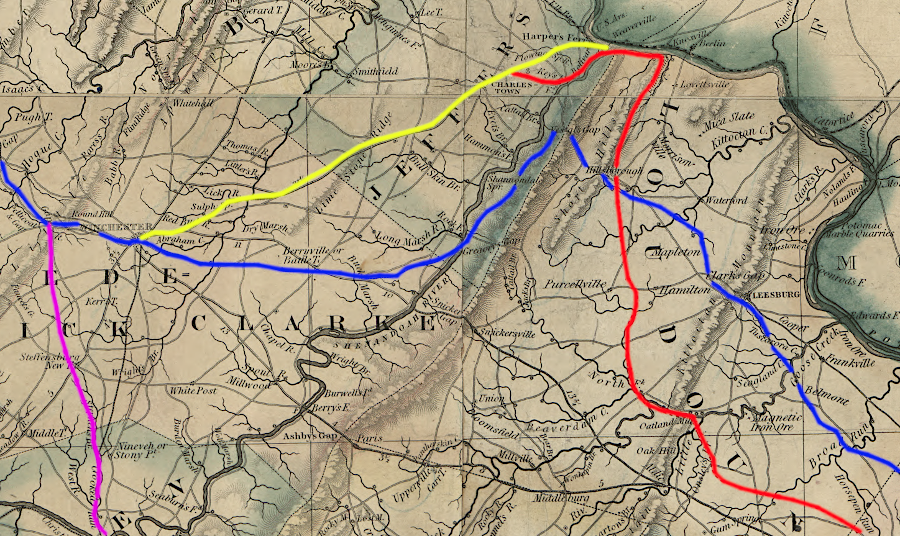

The Loudoun Branch, running from near Centreville past Leesburg to Vestal's (Keye's) Gap, was intended to capture traffic from the Piedmont in Loudoun County as well as connect to the intersect with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at Harpers Ferry. That stretch of track would compete for a market that other Alexandria investors were targeting with the proposed Alexandria and Harpers Ferry Railroad, which ended up being constructed as the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad.

the Manassas Gap Railroad anticipated connections to Leesburg and Winchester

Source: Library of Virginia, A map of the rail roads of Virginia (1858)

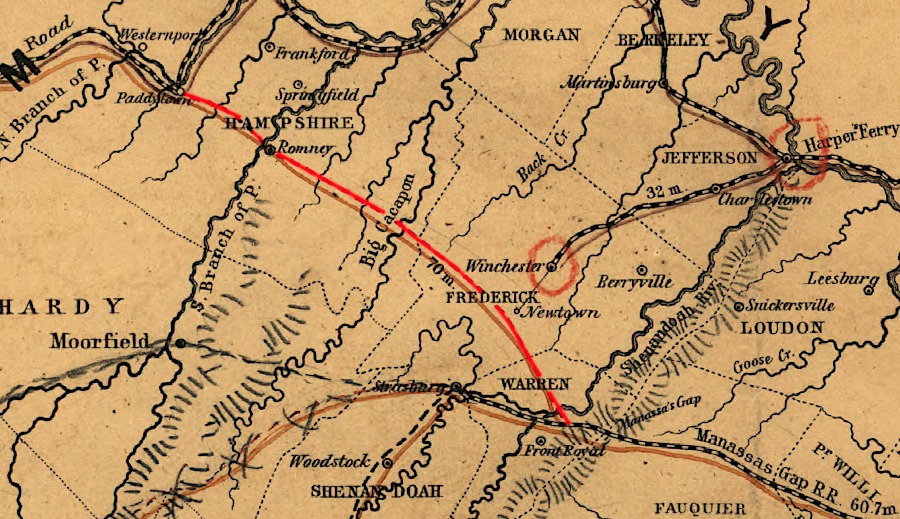

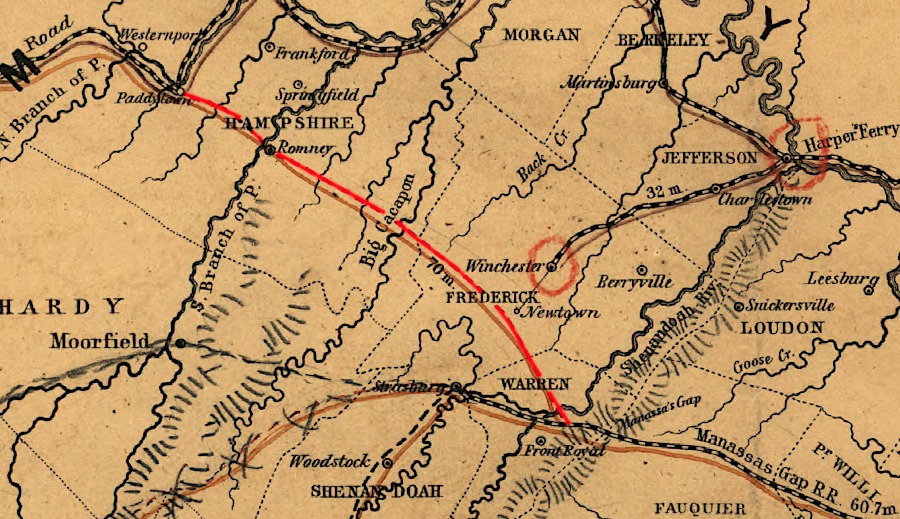

the Manassas Gap Railroad planned to build west from Winchester to capture coal and timber traffic from Westernport, Maryland (red X)

Source: Library of Virginia, A map of the rail roads of Virginia (1858)

Legislation in 1853 also permitted the Manassas Gap Railroad to continue the Loudoun Branch west of the Shenandoah Valley to Westernport, Maryland. Endpoint of the branch line could be the coal fields in Hampshire County, which ended up becoming the intended destination of the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad.5

the Manassas Gap Railroad envisioned building to the coal fields at Paddytown (now Keyser, WV)

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the proposed line of Rail Road connection between tide water Virginia and the Ohio River at Guyandotte, Parkersburg and Wheeling (1852)

the Manassas Gap planned an Independent Line (red) to connect to the Winchester and Potomac (yellow) and envisioned a line north of Strasburg (purple), while the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire (blue) planned to build to Paddytown (now Keyser, WV)

Source: Library of Congress, A map of the state of Virginia (by Lewis Von Buchholtz, L. V., Herman Böÿe, Benjamin Tanner, 1859)

The Manassas Gap Railroad reached Strasburg in 1854, and Woodstock in 1856. Construction on the Loudoun Branch reportedly included a partial tunnel at Mount Gilead near Oatlands in Loudoun County.

Most of the railbed for the Independent Line was completed by 1857, but an economic recession ("panic") made it impossible for the investors to continue to fund all the planned mileage. Rails were never placed on the Independent Line or on the Loudoun Branch.

the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad was planned to run to Fairfax Courthouse, then westward north of Centreville

Source: Library of Congress, A map of Fairfax County, and parts of Loudoun and Prince William Counties, Va., and the District of Columbia

Despite the Panic of 1857, track was extended in the Shenandoah Valley to Mount Jackson in 1859. Construction of the remaining 25 miles to Harrisonburg continued, but no rails had been placed on that roadbed when the Civil War froze all expansion in 1861.6

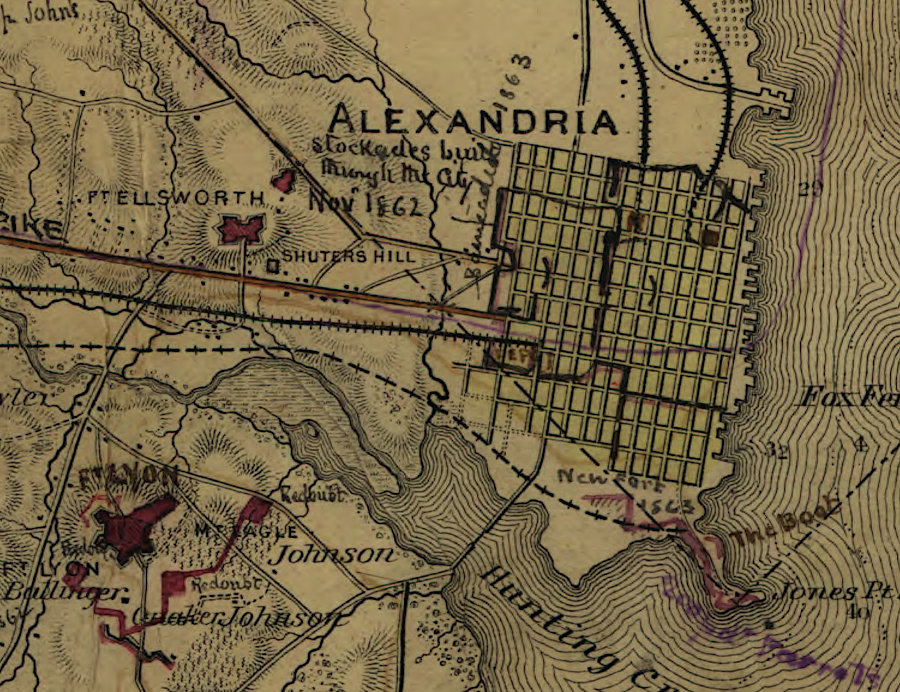

the eastern end of the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad was planned to be at Jones Point

Source: Library of Congress, Topographical map of Washington, D.C., and vicinity. Showing the Union forts and defences built 1861-3. (Robert Knox Sneden, 1861-65)

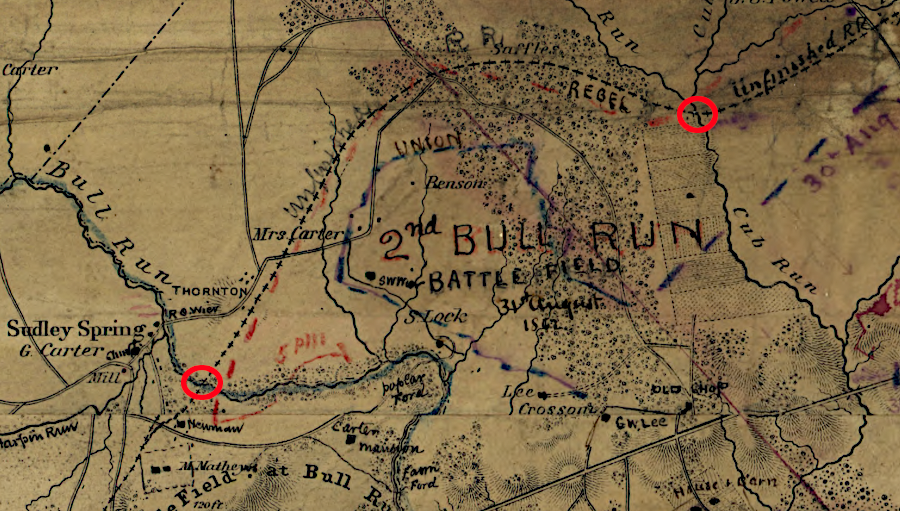

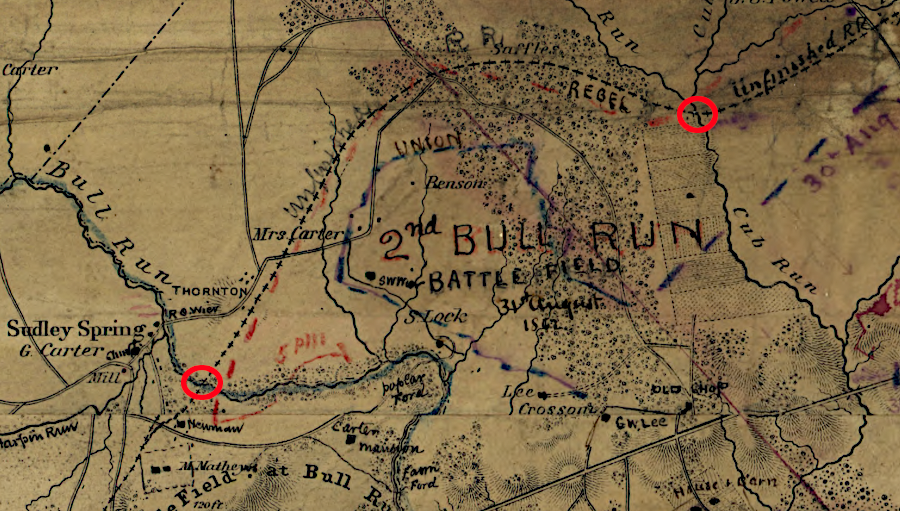

Only a flat roadbed had been constructed on the Independent Line, without trestles, crossties or rails, before the Second Battle of Manassas in August, 1862. General Stonewall Jackson's corps used the unfinished railroad to align regiments that blunted the Union attack.

bridge abutments on Cub Run and Bull Run were completed for the unfinished line of the Manassas Gap Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Map of 1st and 2nd Bull Run battles. Official map from the Topographical Bureau, Washington, D.C.

In one famous incident, Confederate soldiers on one side of the trackbed who ran out of ammunition used stones excavated at Deep Cut by the Irish and enslaved laborers. The Confederates, sheltering from rifle and artillery fire on the western side of the unfinished railroad, hurled the stones at the Union soldiers pressed close to the other side.7

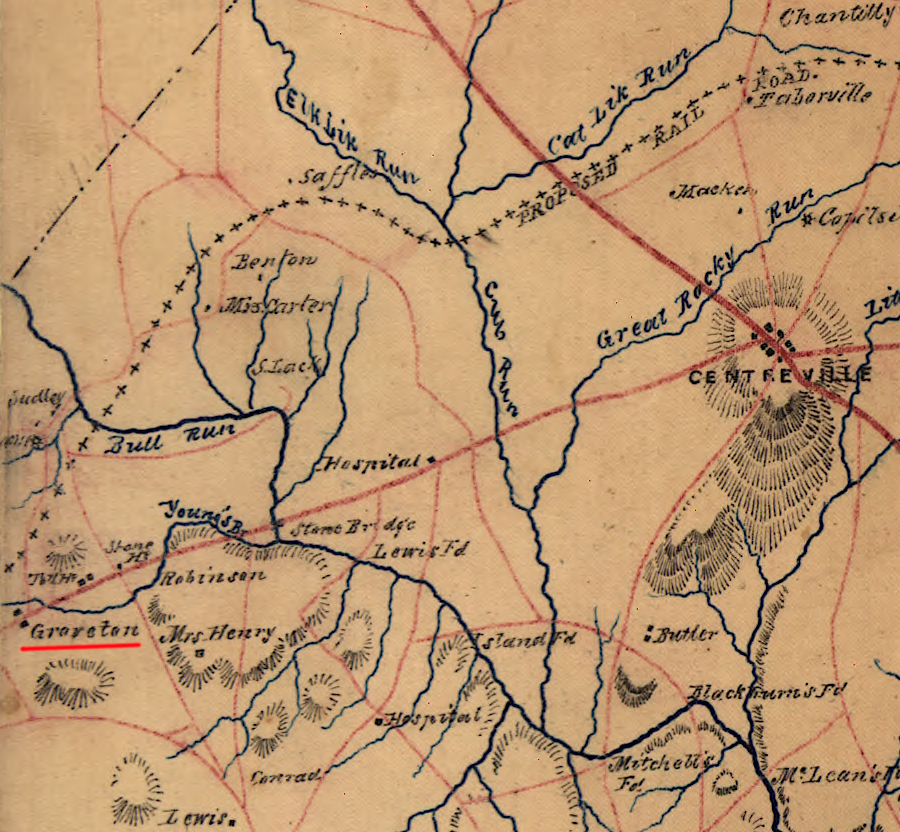

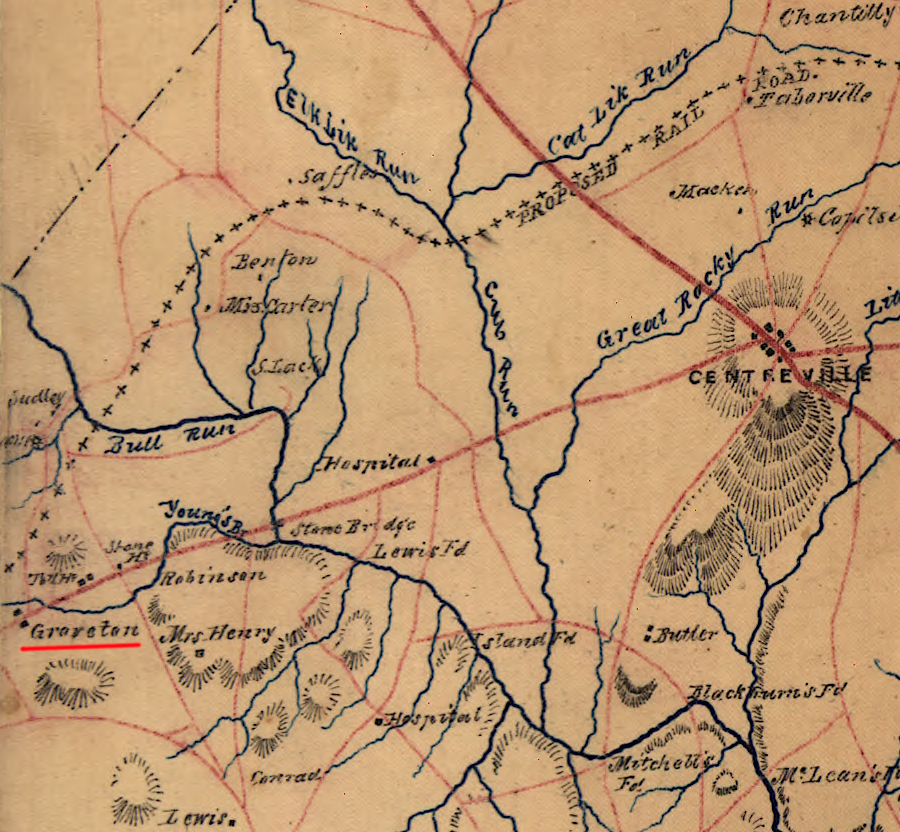

the unfinished portion (black X's) of the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad near Groveton was a key feature in the Second Battle of Manassas in 1862

Source: Library of Congress, A map of Fairfax County, and parts of Loudoun and Prince William Counties, Va., and the District of Columbia

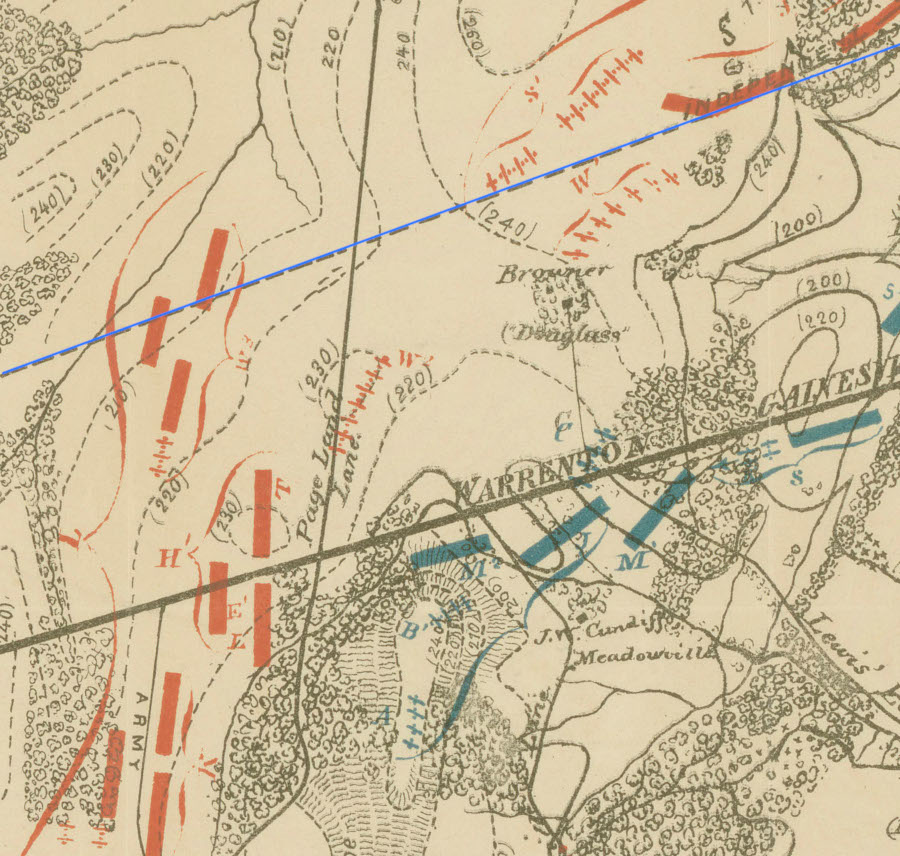

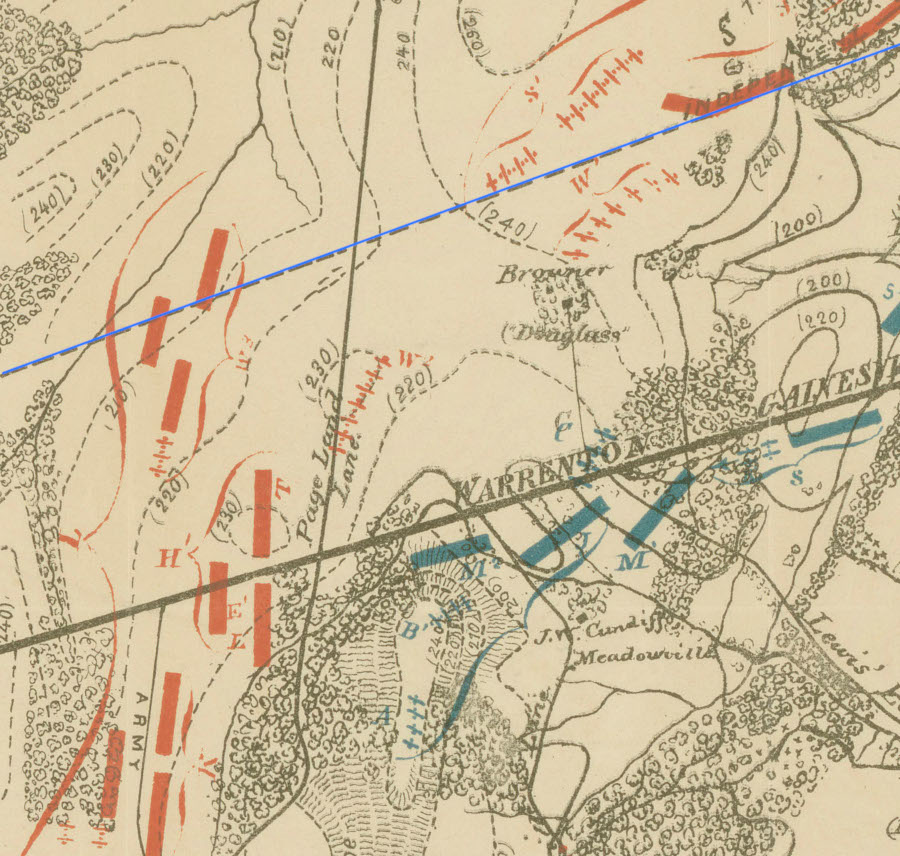

Confederate (red) and Union (blue) forces fought along the unfinished portion (blue line) of the Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad in August, 1862

Source: National Archives, Map of the Battlegrounds in the Vicinity of Groveton near Manassas

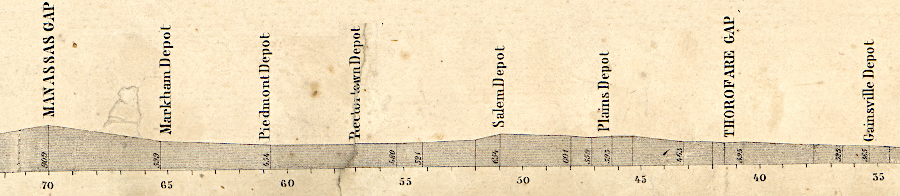

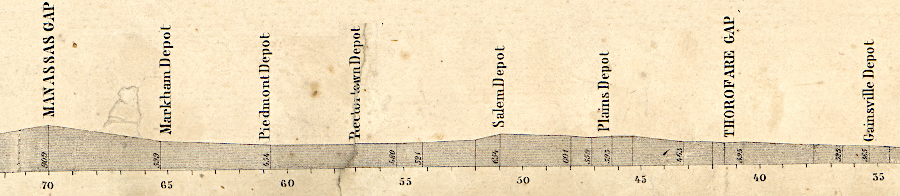

the Manassas Gap Railroad engineered its route through the Blue Ridge to minimize steep grades

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Manassas Gap Railroad and its extensions; September, 1855

After the Civil War, there was too little speculative investment capital available in war-ravaged Virginia to restart construction of the Independent Line, and too little business to justify building the Loudoun Branch to Leesburg and compete with the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad. To obtain the funding required to rebuild the Manassas Gap Railroad, it was merged with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad in 1867 to create the Orange, Alexandria and Manassas Railroad.

the unfinished line would have passed west of modern Fair Oaks Mall

Source: Library of Congress, Map of 1st and 2nd Bull Run battles. Official map from the Topographical Bureau, Washington, D.C.

The Manassas Gap Railroad was judged to have little value beyond its legal authorization to operate between Manassas Junction and Harrisonburg. Stockholders of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad made an almost-token payment to the investors in the Manassas Gap Railroad, and placed two members of that corporation on the board of the new Orange, Alexandria and Manassas Railroad.8

Since 1867, the route of the Manassas Gap Railroad has been used by multiple corporations. The Orange, Alexandria and Manassas Railroad operated on the track between 1867-1873.

The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad controlled the route between 1873-1886, first by leasing the Washington City, Virginia Midland & Great Southern Railroad. After the Washington City, Virginia Midland & Great Southern Railroad went through bankruptcy in 1881, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad retained control by leasing the successor corporation, the Virginia Midland Railway.

The Strasburg-Harrisonburg section was a key link in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's plan to control track from Harpers Ferry to Salem. However, the construction costs to build that line were higher than the estimated profits. After the competing Shenandoah Valley (Norfolk and Western) Railroad was completed to Roanoke, financing for extending the Valley Railroad further south from Harrisonburg dried up.

Construction of the Valley Railroad stopped at Lexington. Though the track of the original Manassas Gap Railroad was extended to a connection with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad at Staunton and at Lexington, it never became a major trunk line. The Norfolk and Western Railroad, running east of Massanutten Mountain through the Page Valley, captured the traffic going north from Tennessee to Maryland.

In 1886, the expanding Richmond and Danville Railroad took control of the route of the original Manassas Gap Railroad. That corporation was reorganized into the Southern Railway in 1894. It merged with the Norfolk and Western Railroad in 1982 to create the Norfolk Southern.

In 2025, the Norfolk Southern asked for approval by the Surface Transportation Board to discontinue service on an 11-mile stretch of track between Front Royal and Strasburg. No traffic had used one of the two tracks for two years.9

Links

- Confederate Railroads

- Encyclopedia Virginia

Manassas Gap (blue) and Orange and Alexandria (red) railroads in 1860

Source: Library of Congress, Fords on Occoquan and Bull Run (by Col. Harrston, 1860)

References

1. "Virginia Midland Railroad Company," Annual Report, Virginia. Railroad Commissioner, 1898, p.327, https://books.google.com/books?id=mCUaAQAAIAAJ; J. Randolph Kean, "The Development of the 'Valley Line' of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 60, Number 4 (October, 1952), p.541, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4245875; Charles Minor Blackford, Legal History of the Virginia Midland Railway Co., and of the Companies which Built Its Lines of Road, J.P. Bell, 1881, pp.20, https://books.google.com/books?id=vV4EAAAAMAAJ (last checked June 20, 2020)

2. Charles Minor Blackford, Legal History of the Virginia Midland Railway Co., and of the Companies which Built Its Lines of Road, J.P. Bell, 1881, p.17, https://books.google.com/books?id=vV4EAAAAMAAJ (last checked June 20, 2020)

3. "Spot Elevation Tool," National Map, US Geological Survey (USGS), https://viewer.nationalmap.gov/theme/elevation/ (last checked April 18, 2020)

4. "Delaplane Historic District," National Register of Historic Places nomination form, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, December 23, 2003, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/030-0002/ (last checked June 10, 2020)

5. Herbert H. Harwood Jr., Rails to the Blue Ridge: The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, 1847-1968, Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority, 2000, pp.11-12, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/2GvQAAAACAAJ; Charles Minor Blackford, Legal History of the Virginia Midland Railway Co., and of the Companies which Built Its Lines of Road, J.P. Bell, 1881, p.15, https://books.google.com/books?id=vV4EAAAAMAAJ (last checked June 20, 2020)

6."'The Unfinished Railroad' in Lincoln," LoudounNOW, September 9, 2016, https://www.loudounnow.com/archives/the-unfinished-railroad-in-lincoln/article_0cdb8319-f7ac-5e64-a50f-c0878f738c0d.html; "Manassas Gap Railroad Bed," Lincoln Preservation Foundation, https://www.lincolnpreservation.org/manassas-gap-railroad-bed (last checked January 3, 2025)

7. "Moments in Time: The Battle of Second Manassas - The Railroad Cut, Part 3," American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/moments-time-battle-second-manassas-railroad-cut-part-3 (last checked November 25, 2023)

8. Charles Minor Blackford, Legal History of the Virginia Midland Railway Co., and of the Companies which Built Its Lines of Road, J.P. Bell, 1881, pp.25-27, https://books.google.com/books?id=vV4EAAAAMAAJ (last checked June 20, 2020)

9. "Norfolk Southern Files to Abandon 11-Mile Virginia Line," RailFanning.org, July 26, 2025, https://railfanning.org/2025/07/norfolk-southern-files-to-abandon-11-mile-virginia-line/ (last checked July 29, 2025)

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places