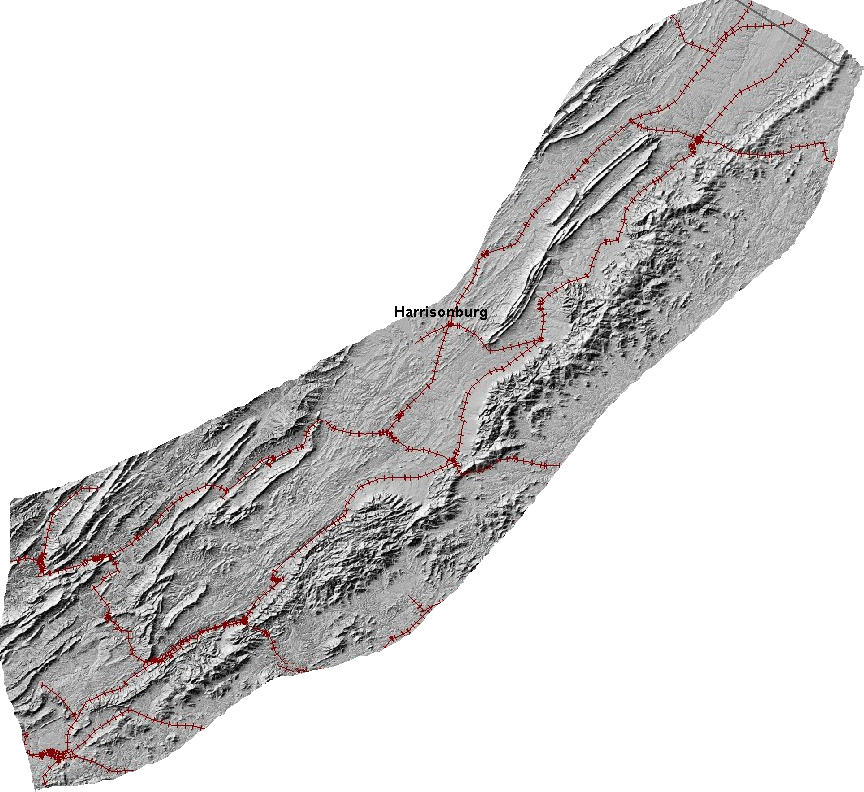

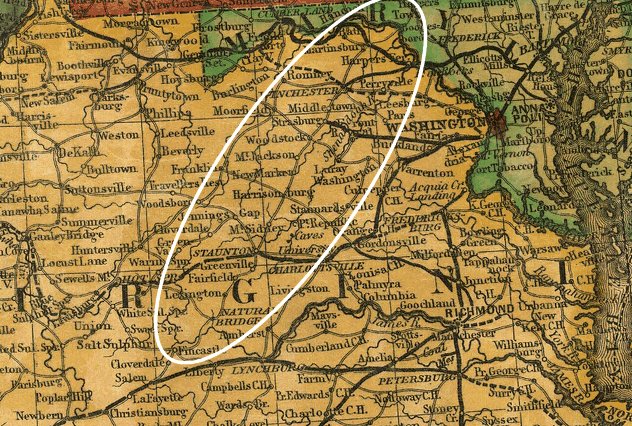

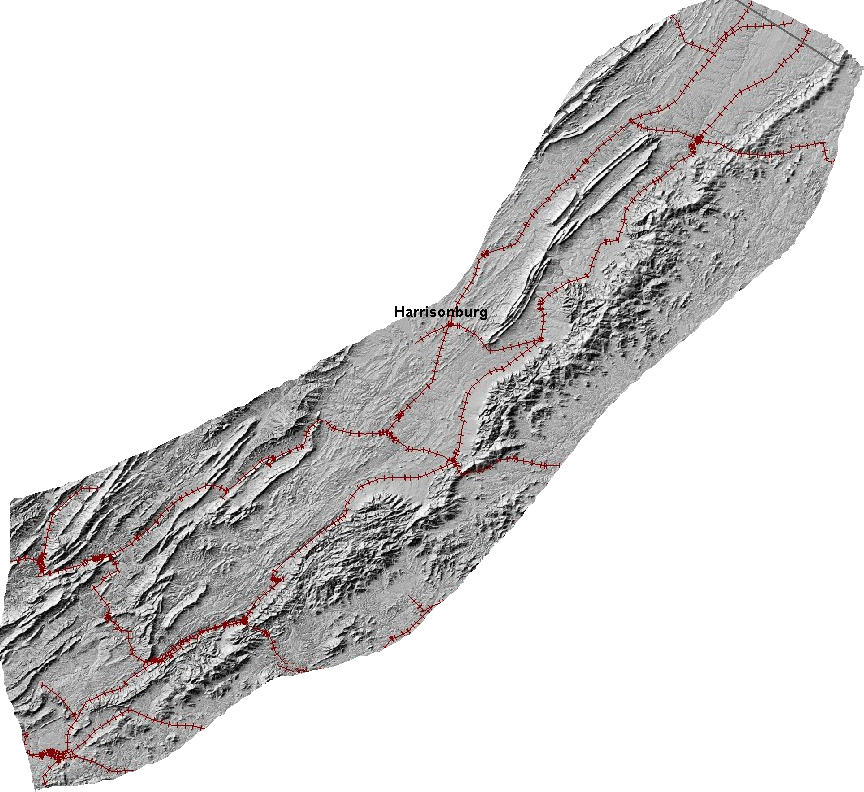

Railroads of the Shenandoah Valley - and Why Isn't Harrisonburg on the Main Line?

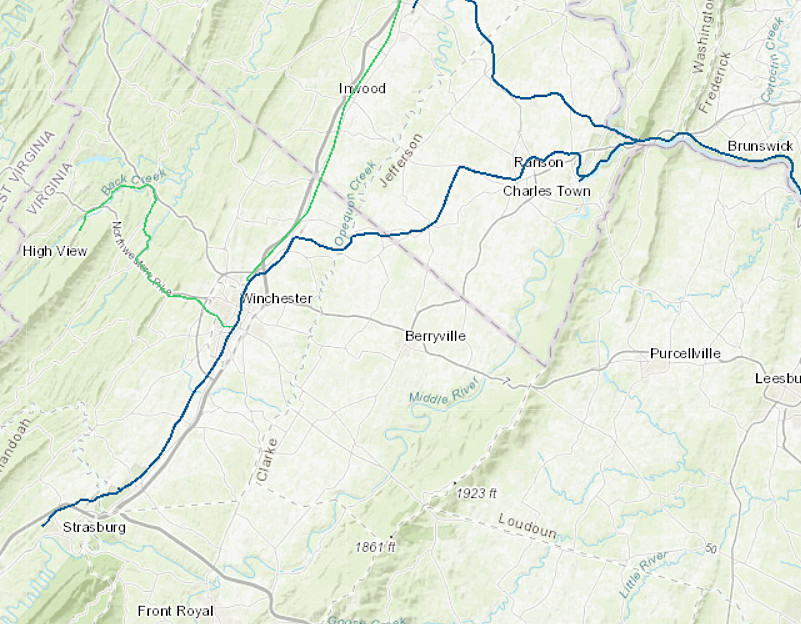

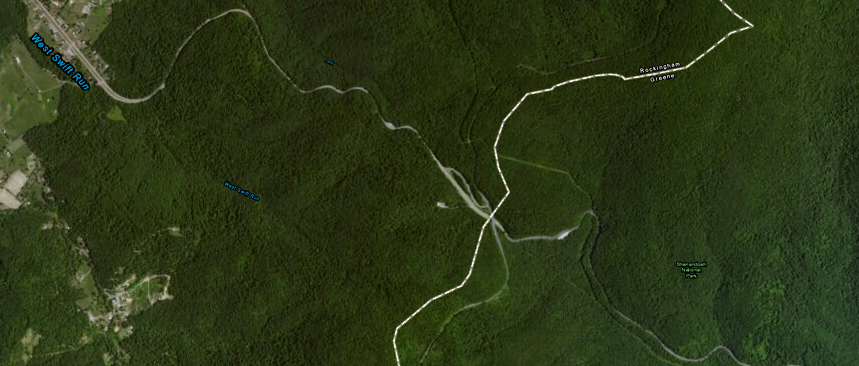

the Norfolk Southern track in the Shenandoah Valley is located east of Massanutten Mountain, linking Front Royal with Waynesboro - not on the western side of Massanutten through Harrisonburg - because iron furnaces in the Page Valley were expected to provide business for the original Shenandoah Valley Railroad

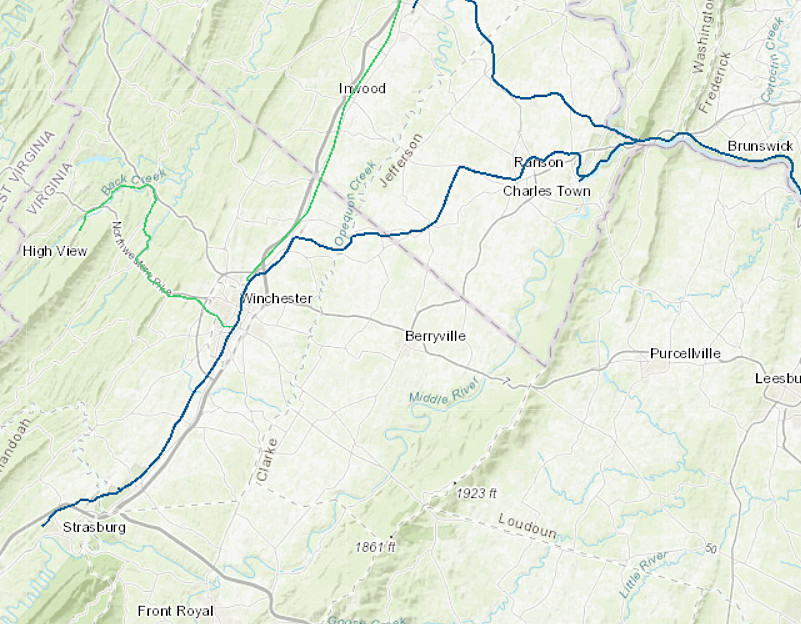

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map

Three factors shaped the routes of railroads across the Blue Ridge and through the Shenandoah Valley - funding, topography, and a source of enough freight traffic to justify the funding required to conquer the topography.

Sectional competition between Virginia's major port cities at Alexandria, Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg, and Norfolk/Portsmouth shaped construction of Virginia's transportation network. Through the Board of Public Works, the state would subsidize 40-60% of the cost of constructing new turnpikes, canals, and railroads.

Before the Civil War, the funding and initiative to build the Orange and Alexandria, Virginia Central, Norfolk and Petersburg, Petersburg, Portsmouth and Roanoke, and other railroads was locality-based. Rivalry between the cities was reflected in the routes of the lines, which typically carried freight from the Piedmont and valleys west of the Blue Ridge to just one port.

There were few connections between railroads. Maximizing traffic on the lines to make the railroad corporation profitable was not the priority. Maximizing traffic to a particular port, and stimulating business and profits in that port city, was the primary objective.

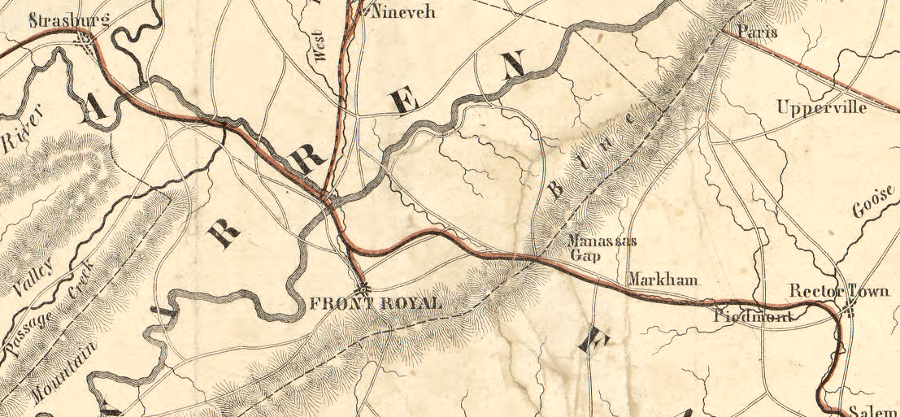

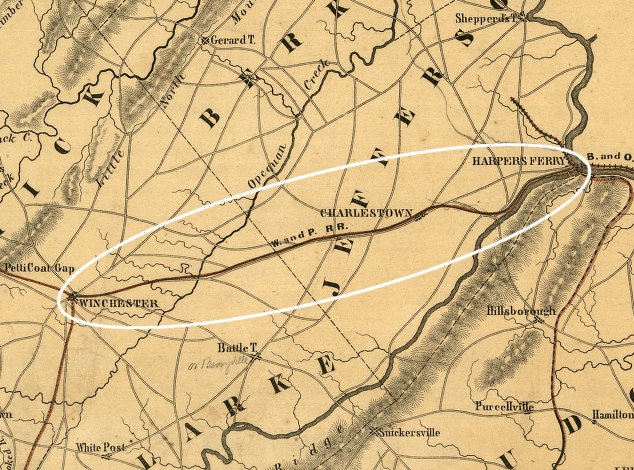

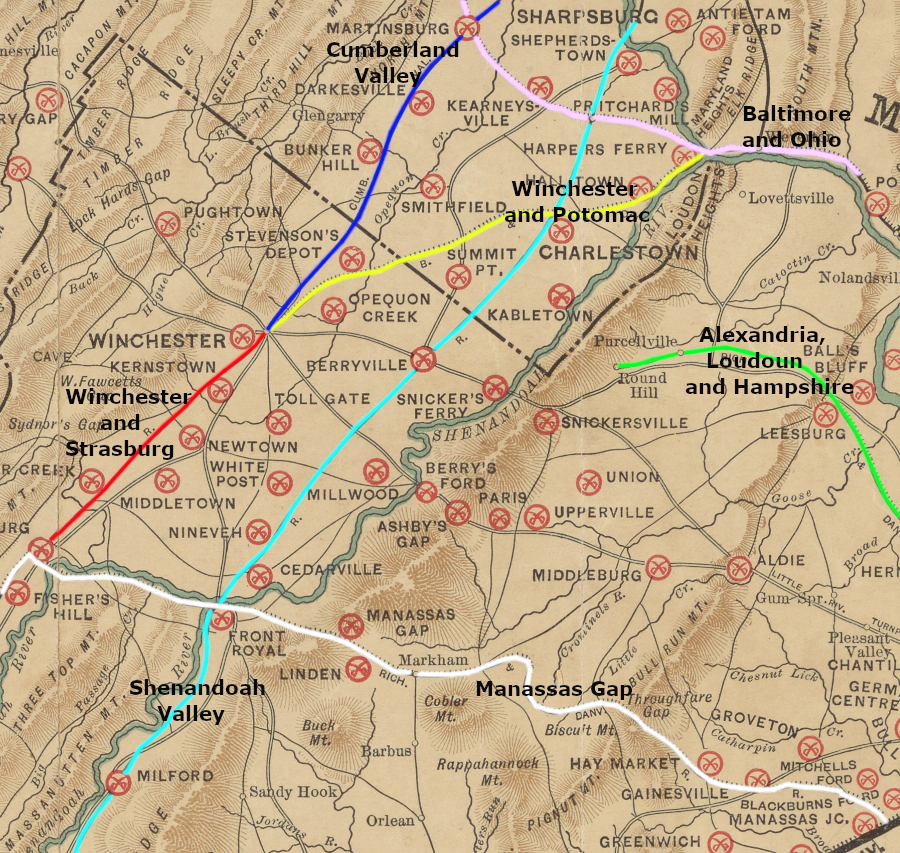

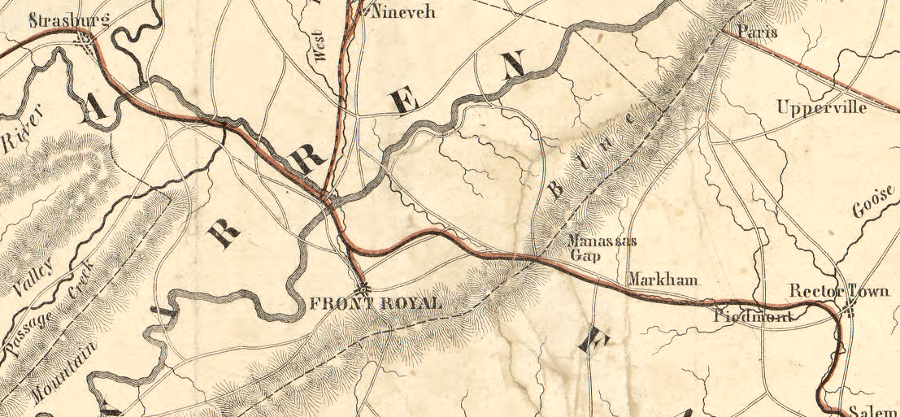

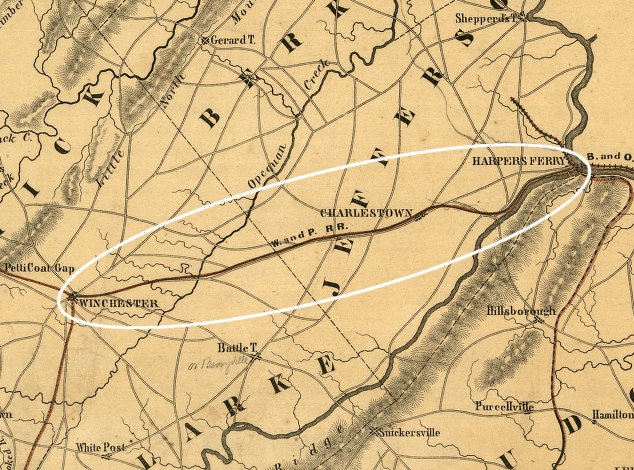

The local investors in railroads expected to ship agricultural products east to the port city, and send manufactured goods west on the return trip. The Manassas Gap Railroad was built into the Shenandoah Valley at Front Royal to carry wheat and other crops to Alexandria. The Winchester and Potomac Railroad was built further north by the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad, to carry farm products from the lower valley to the competing port at Baltimore.

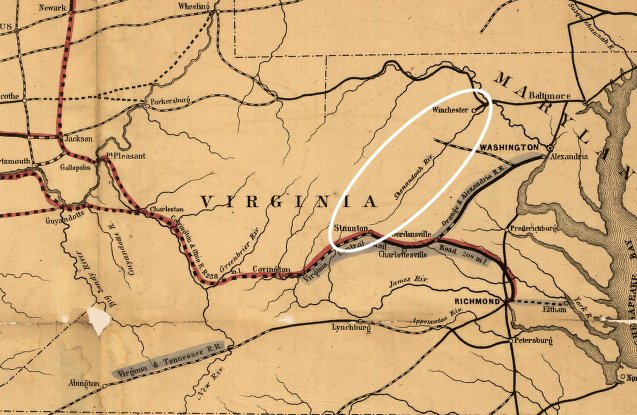

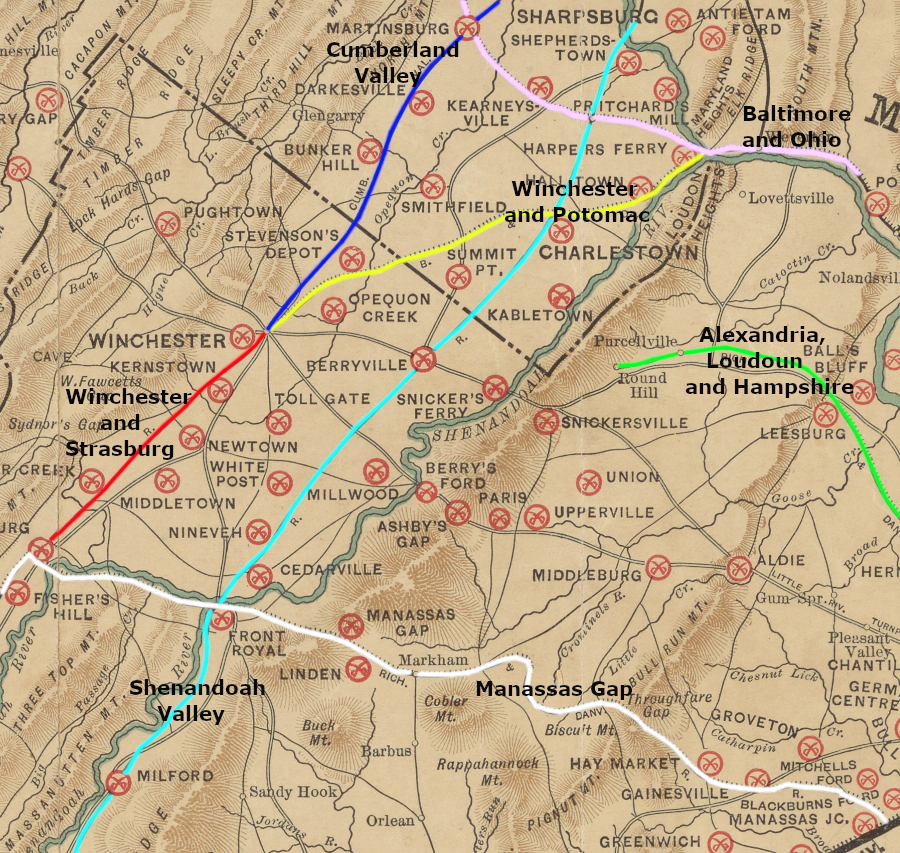

in 1851, there were three railroads into the Shenandoah Valley

Source: Library of Congress, General map of the Orange & Alexandria Rail Road and its connections north, south, and west. (1851)

Before 1861, the only major source of mineral products in Virginia that justified building a railroad for transport was the coal in Chesterfield County. After the Civil War, coal and iron ore became dominant factors in expanding the railroad network.

The location of iron ore in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, and the location of coal fields on the Appalachian Plateau, became key factors in planning new tracks near Harrisonburg. The location of iron ore determined the route of the Shenandoah Valley Railroad (later the Norfolk and Western) through the Shenandoah Valley.

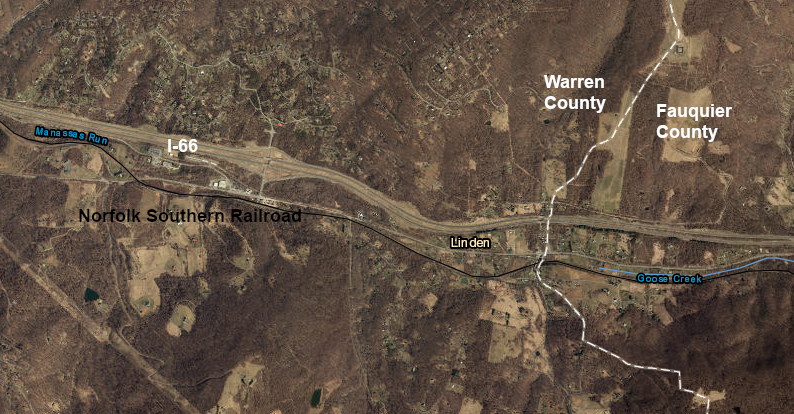

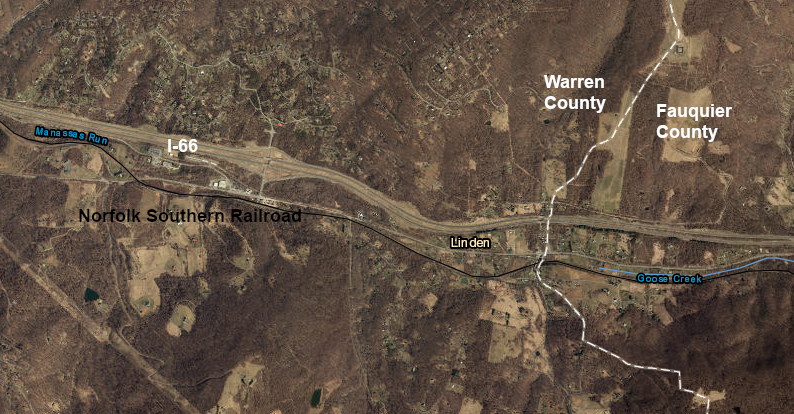

The Manassas Gap and the Winchester and Potomac railroads minimized construction costs by passing through natural gaps in the Blue Ridge. The Winchester and Potomac Railroad linked to the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad at Harpers Ferry. The Baltimore and Ohio took advantage of the water gap carved by the Potomac River, though a tunnel in Maryland was required to get through the Blue Ridge. The Manassas Gap Railroad relied upon the "wind gap" eroded by Manassas Run and Goose Creek.

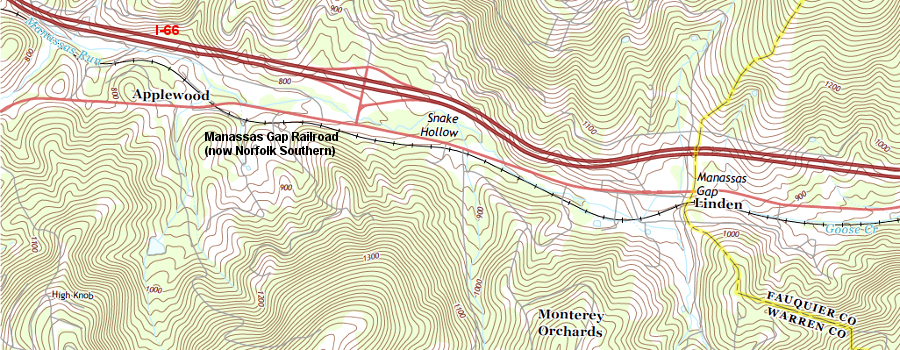

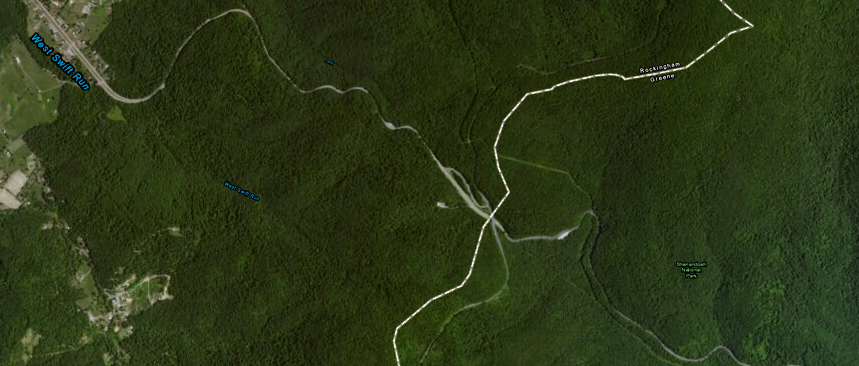

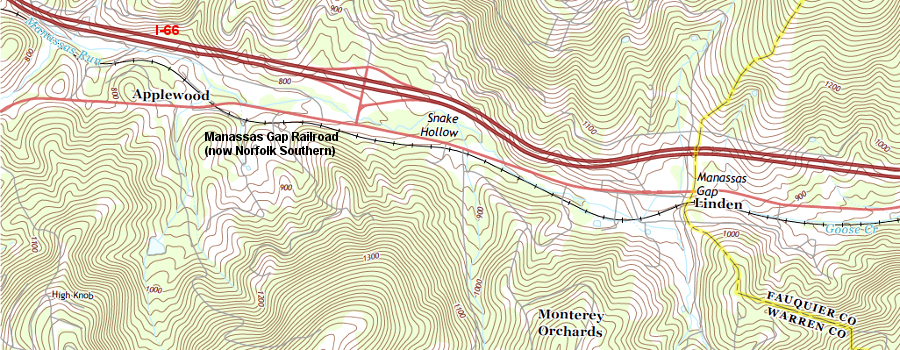

the Manassas Gap railroad route took advantage of a wind gap in the Blue Ridge carved by Manassas Run and Goose Creek

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Finding a location to cross the Blue Ridge anywhere besides through a natural water/wind gap was a major engineering challenge. Locomotives can pull massive amounts of weight on the slick rails, but they lose most of their power when the rails are tilted uphill and have great difficulty stopping on downhill grades. On a 0.5 % grade, railroad tracks rise the height of an average stairway step (6 inches) over the distance of 1/3 of a football field (100 feet). Even a modern locomotive that can pull 1,000 tons on a flat grade can pull only 200 tons on a 0.5% grade.1

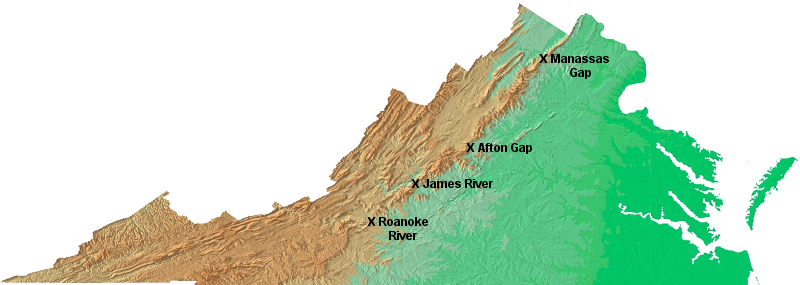

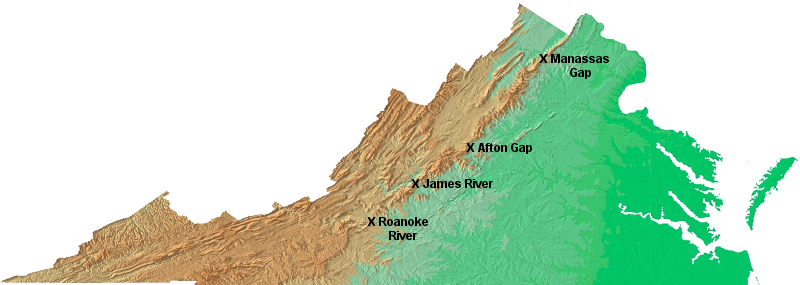

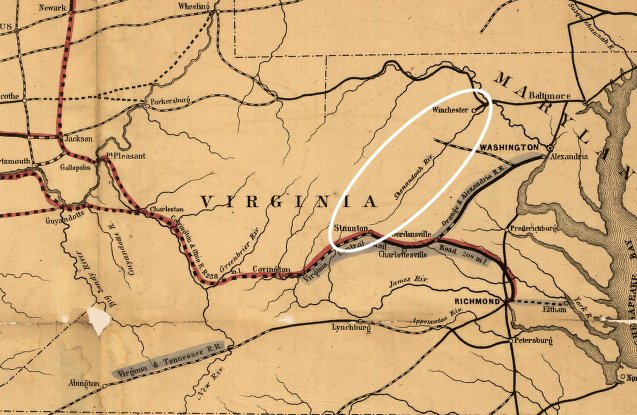

As a result of the mountain topography and sectional competition, the Blue Ridge was pierced by railroads in only four places in Virginia. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Manassas Gap (where modern I-66 crosses), Rockfish Gap (where modern I-64 crosses), the James River, and the Roanoke River.

railroads were built across the Blue Ridge in only four locations

Source: USGS Open-File Report 99-11, Color Shaded Relief Map of the Conterminous United States

Almost all railroad mileage built in Virginia before the Civil War was located east of the Blue Ridge, much to the frustration of those living west of the mountains. Rail routes were designed primarily to connect the farms in the Piedmont to Alexandria, Richmond, or Petersburg in eastern Virginia. Norfolk/Portsmouth struggled against Petersburg/Richmond to pull trade from the Roanoke River watershed to the docks in Hampton Roads.

West of the Blue Ridge, the only railroad not shaped by the rivalry of Virginia's Tidewater ports was one small spur line at the northern tip of the Shenandoah Valley. The Winchester and Potomac provided a link from Winchester through Harper's Ferry to the competing port city of Baltimore, providing business to the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad rather than a railroad controlled by Virginians.

Topography limited the ability of port cities to build rail lines beyond the Blue Ridge that would increase traffic from the Shenandoah Valley. The Baltimore & Ohio built its line through the water gap carved by the Potomac River. Much further south, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad constructed a line between Lynchburg-Bristol through the water gap carved by the Roanoke River. In 1750, Dr. Thomas Walker crossed through the Roanoke River gap on his journey that also took him through Cumberland Gap, and reported:2

- After wards we crossed the Blue Ridge. The Ascent and Descent is so easie, that a Stranger would not know, when he crossed the Ridge.

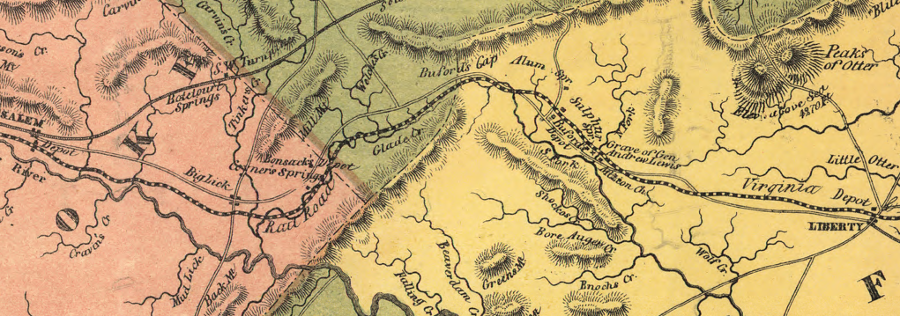

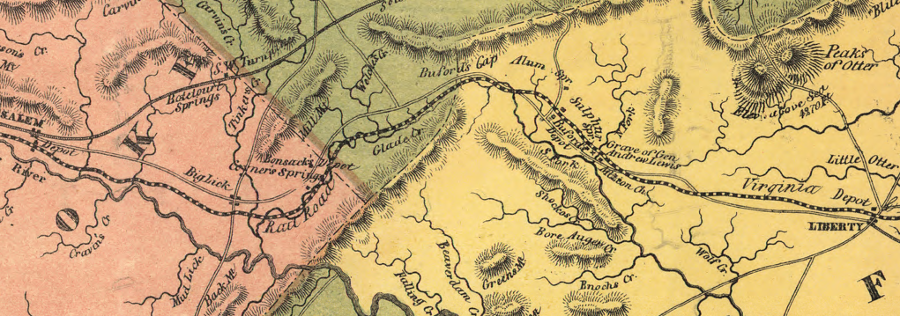

the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad pierced the Blue Ridge at the Roanoke River water gap ("Big Lick" later became the City of Roanoke)

Source: Library of Congress, Map & profile of the Virginia & Tennessee Rail Road (1856)

The Manassas Gap Railroad used the low spot already created by natural erosion at the headwaters of Goose Creek and Manassas Run. The railroad climbed 650 feet from the junction with the Orange and Alexandria Railroad (now the City of Manassas), crossed the Manassas Gap "wind gap," then dropped nearly 400 feet to Front Royal.

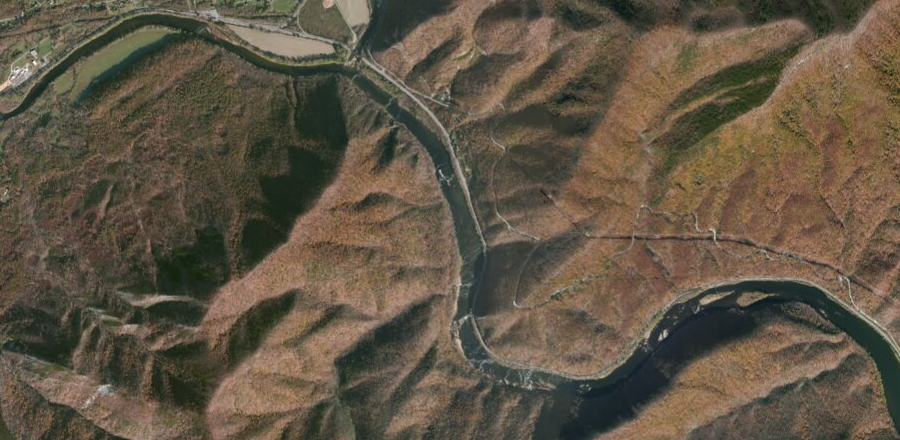

Manassas Run and Goose Creek eroded a gap through the Blue Ridge, and the Manassas Gap Railroad took advantage of that topographic low point

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Linden 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

the Manassas Gap Railroad was completed to Mount Jackson prior to the Civil War, providing lower costs for Shenandoah Valley farmers to send products to the port at Alexandria and more opportunities for Alexandria merchants to sell imported goods to customers west of the Blue Ridge

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Manassas Gap Railroad and its extensions; September, 1855

The James River and Kanawha Canal controlled the last natural gap, gap carved by the James River. That canal blocked any opportunity for a competing railroad to use that route during the peak of construction in the 1840's and 1850's.

After the Civil War, the bankrupt canal company was acquired by the Richmond and Allegheny Railroad. It built a rail line on the old towpath and offered a "water level route" by rail through the mountains. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad soon acquired that line, and today the trains going through the James River gap are pulled by blue-and-yellow CSX locomotives.

the James River carved a gap through the Blue Ridge at Balcony Falls, which provided a path for the James River and Kanawha Canal and - after the Civil War - the Richmond and Allegheny Railroad (now the CSX)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Manassas Gap Railroad was completed to Mount Jackson prior to the Civil War. That provided lower costs for Shenandoah Valley farmers, even those further south at Harrisonburg, to send products to the port at Alexandria. A rail line to Mount Jackson created more opportunities for Alexandria merchants to sell manufactured goods to customers west of the Blue Ridge, just as the Orange and Alexandria Railroad provided cheaper transportation costs to the Piedmont east of the mountain ridge.

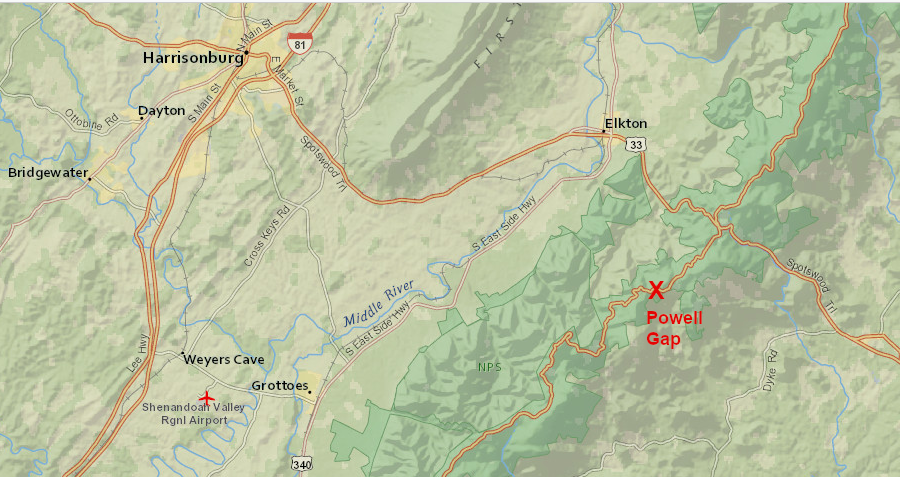

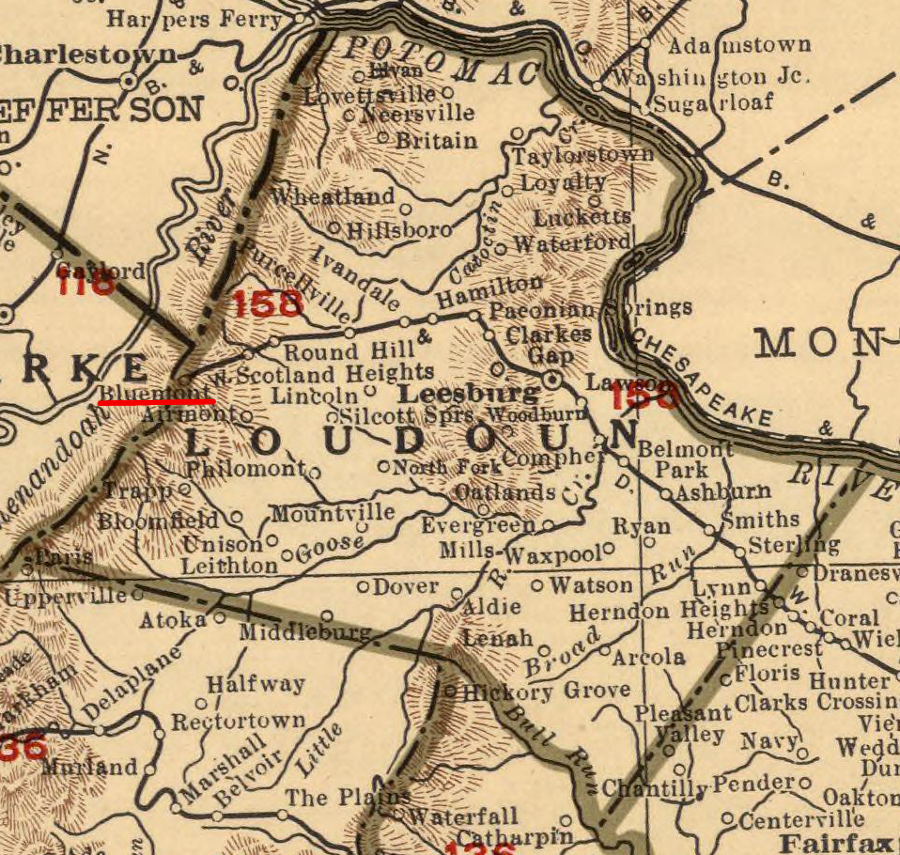

The Manassas Gap Railroad was the only one railroad that ever managed to cross the Blue Ridge between Rockfish Gap and the Potomac River. Two others had plans, however. The Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H) Railroad planned to cross where Route 7 goes through the mountains today, and the Chesapeake Western Railway planned to cross at Powell Gap east of Elkton.

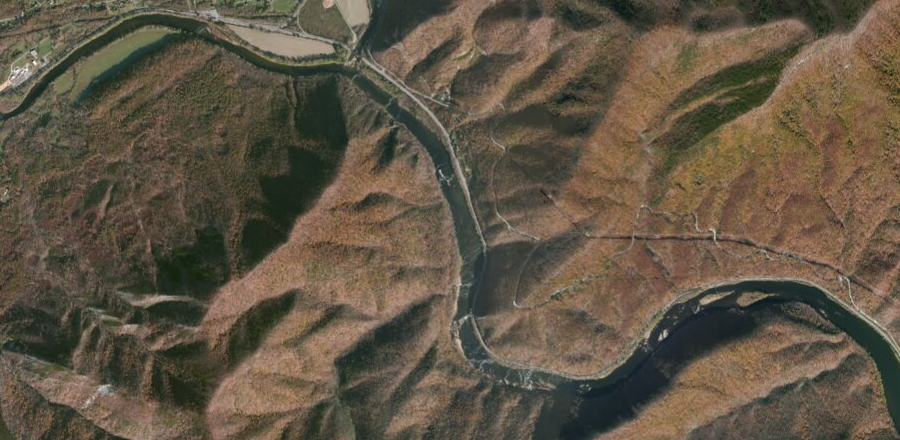

the Chesapeake Western Railway planned to cross the Blue Ridge at Powell Gap

(NOTE: "Middle River" is the South Fork of the Shenandoah River)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

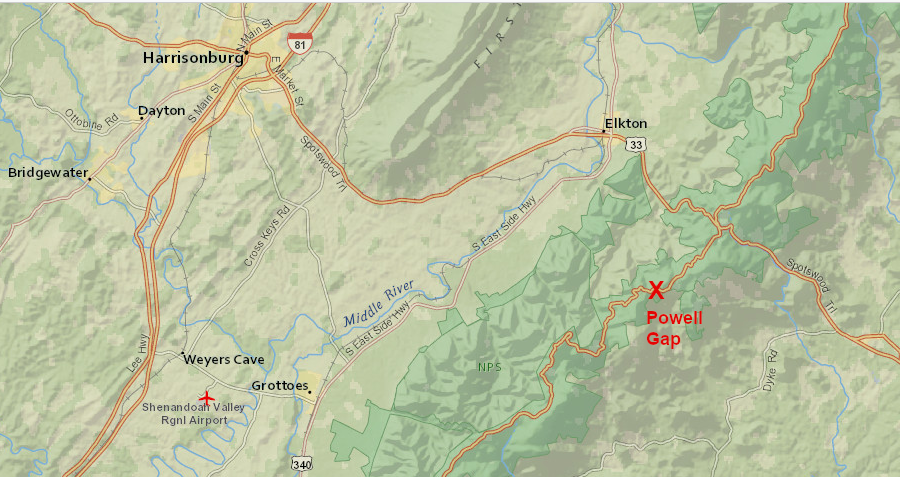

The Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire (AL&H) Railroad planned during several corporate incarnations to link Alexandria/Leesburg with Winchester and the coal fields in Hampshire County. The railroad would cross the Blue Ridge near Snickers Gap.

Ultimately a railroad line was extended west of Purcellville to Bluemont to serve tourists going to mountain resorts. Topography, and the limited opportunity to compete with the Winchester and Potomac Railroad already hauling freight from the Shenandoah Valley to Baltimore, made it too expensive to go further westward.

in 1900 the Southern Railway extended the old Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire Railroad to Snickersville and the town was renamed Bluemont to encourage tourism, but railroad tracks were never pushed west across the Blue Ridge to Winchester (much less Hampshire County)

Source: David Rumsey Map Library, Rand McNally Atlas Virginia (1924)

At only one place was a set of tunnels constructed through the Blue Ridge so trains could avoid much of the climb in elevation. Those tunnels were excavated at Afton Gap (where I-64 crosses today) between 1850-1858.

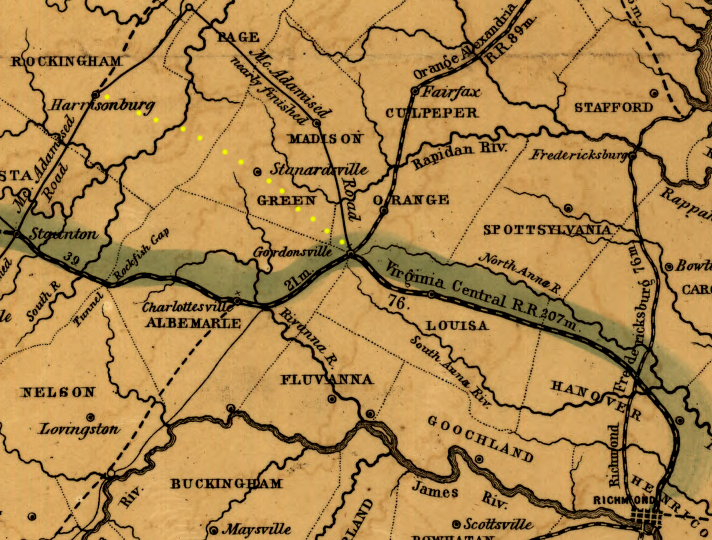

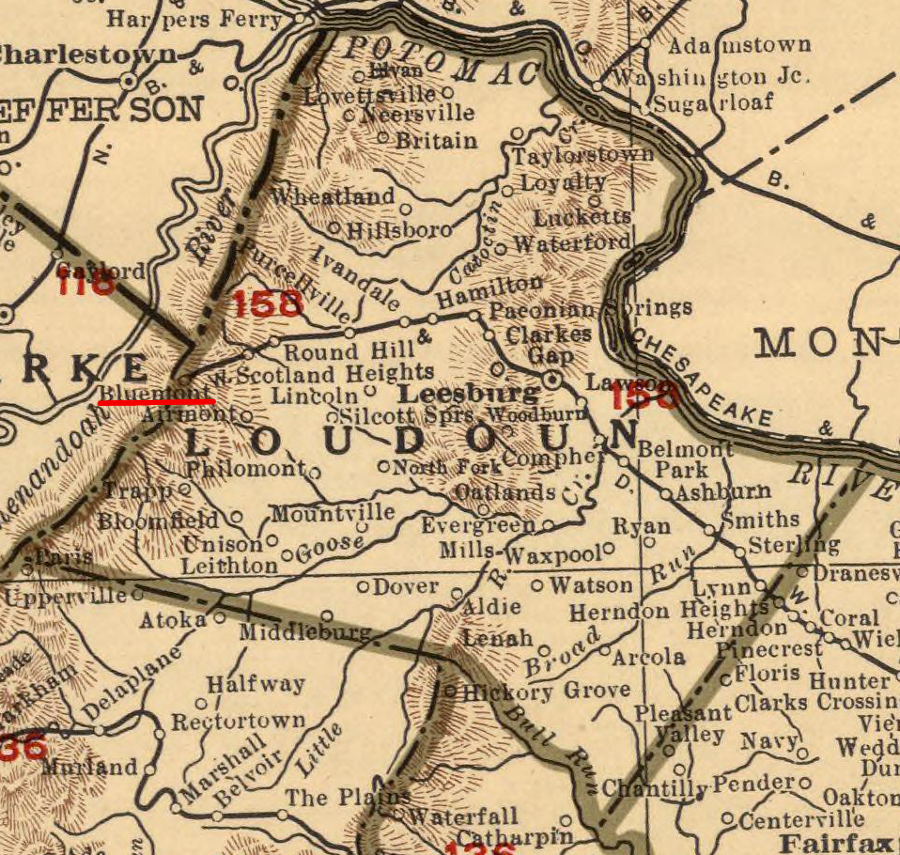

Not everyone expected the railroad to cut through the Blue Ridge so far south. The Louisa Railroad had been chartered in 1836 as a direct Richmond-Harrisonburg route. Engineers proposed to cross the Blue Ridge at Swift Run Gap (where US 33 crosses today). The line was renamed the Virginia Central in 1850, after it had been extended to Gordonsville.

From that location, the company skillfully maneuvered investors to purchase stock by pitting Charlottesville against Harrisonburg, and Harrisonburg lost the contest. The Virginia Central altered its route, built its line south to Charlottesville, and crossed the Blue Ridge at Afton Gap. A quick look at a map will show that if Albemarle County had been the planned destination, the Virginia Central should parallel the historic Three Chopt Road and modern I-64 from Richmond to Charlottesville, rather than swerve north to Gordonsville first.3

the planned Virginia Central path to Harrisonburg through Swift Run Gap (yellow dots) was not built - the railroad was routed through Charlottesville, crossed the Blue Ridge at Rockfish Gap, and went to Staunton instead

Source: Library of Congress, "Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant

a highway (modern US 33) was built through Swift Run Gap connecting Stanardsville to Elkton, but no railroad ever crossed the Blue Ridge there

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

As a result of the Virginia Central's shift in its planned route, Charlottesville and Staunton got rail connections to Richmond before the Civil War. Harrisonburg had to wait for a railroad until 1868, when the Orange, Alexandria, & Manassas Railroad extended the old Manassas Gap line south from Mt. Jackson.

There was no low gap already carved by a river for the Virginia Central to cross the Blue Ridge. To provide an acceptably-flat route for the iron wheels of locomotives to retain traction on iron rails, engineers determined that the railroad had to drill tunnels somewhere through the hard igneous rock of the mountain.

The cost and risk of such an effort in the 1850's, using hand labor with black powder as the primary explosive, exceeded the capacity of the Virginia Central investors. To ensure the railroad would connect Richmond with the Shenandoah Valley, the Commonwealth of Virginia created the Blue Ridge Railroad and funded the construction of four tunnels at Afton Gap.

The state assumed the risk and hired Claudius Crozet to build the necessary tunnels through the Blue Ridge. After the tunnels were completed, the Virginia Central then leased the 17-mile long Blue Ridge Railroad (including tunnels) from the state.

During the four years of tunnel construction, the Mountain Top Track was built as a temporary line to haul cargo and passengers over the mountain crest. Locomotives slowly hauled three or four cars, carrying up to 50 tons total, up and down grades exceeding 5% until the four tunnels through the Blue Ridge were completed. Three tunnels were short, but the Crozet Tunnel was 4,281 feet long and required eight years to complete. Progress was slow; on some days, digging extended the tunnel just one foot on each end. 4

in 1944 the C&O Railroad completed the tunnel on the left and closed the Crozet Tunnel, through which trains had passed under Afton Gap since 1858

Source: Library of Congress, General View Of Entrance To Blue Ridge Tunnel (Left) From Southeast. Original Blue Ridge R.R. (Crozet) Tunnel Is Visible At Right

Alexandria merchants and taxpayers financed transportation links that sent business from the rural "hinterland" to their port on the Potomac River. Richmond financed competing links westward, across the Blue Ridge, if those links would funnel business to that competing port on the James River.

Richmond and Alexandria competed intensely with each other for state support of rival canals, turnpikes and railroads, but neither city saw any benefit in building rail connections from the Shenandoah Valley to Baltimore or Philadelphia. The economic driver for railroad construction in the Shenandoah Valley was linking farms to Tidewater ports

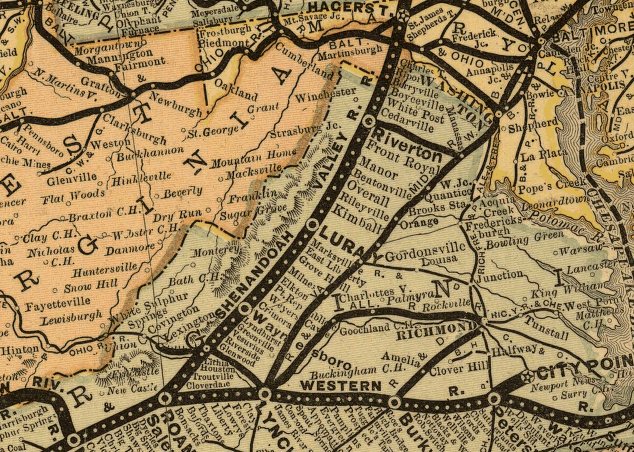

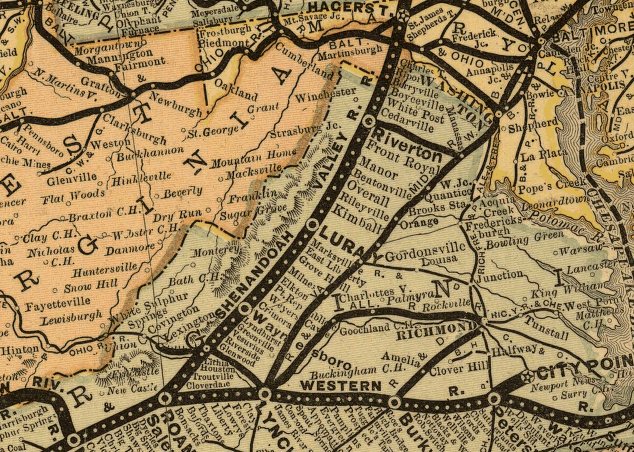

Only after the Civil War, when Virginia was economically distressed, was a railroad constructed north-south through the entire Shenandoah Valley. In 1883, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad (renamed the Norfolk and Western Railroad) finally connected the entire Valley and Ridge province to Baltimore and Pennsylvania.

the "lower" valley, prior to the Manassas Gap Railroad reaching Strasburg (click for larger image)

Source: Library of Congress, "The tourist's guide through the states of Maryland, Delaware and part of

Pennysylvania & Virginia with the routes to their springs &c. / engraved by J. Yeager, Philadelphia." (1836)

The lower Shenandoah Valley got its first railroad connection in 1834 when the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) reached Harpers Ferry. Farmers near the Potomac River could haul their crops to Harpers Ferry, reducing transportation costs to reach Alexandria by wagon via Ashby Gap (modern Route 50), Snickers Gap (modern Route 7), and Keyes Gap (modern Route 9).

Further upstream, all the way to Port Republic in Rockingham County, farmers and iron manufacturers could load their goods on "gundalows" and float downstream to the markets at Harpers Ferry. Because the Shenandoah River was only marginally navigable, the boats were sold for lumber and boatmen walked back home. Much trade was in just one direction - downhill.5

The Winchester & Potomac Railroad connected Winchester to the B&O in 1836, expanding the reach of Baltimore merchants into the valley and improving the farming economy in the lower valley. A connection further south ("up the valley") was not built until after the Civil War. In 1867, the Winchester & Strasburg Railroad finally connected Harpers Ferry to Front Royal, providing the B&O Railroad more access to business in Virginia.

Winchester and Potomac Railroad (parallel to the Valley Pike, most of the way...)

Source: Library of Congress, "Map of the Manassas Gap Railroad and its extensions; September, 1855"

Why the delay, when the heavy traffic along the Valley Pike clearly justified further extension of the railroad south of Winchester to Strasburg? Merchants in Alexandria and Richmond benefitted from Shenandoah Valley trade, and were able to deter construction of a transportation system that would hurt their economic interests.

The Virginia General Assembly, which had the sole authority to issue railroad charters in the state, did not want more Shenandoah Valley products to be shipped by the B&O to Baltimore. The Board of Public Works - a government body funded by Virginia taxpayers to purchase up to 60% of the stock of new railroads, canals, and turnpikes - was reluctant to invest in new railroads unless they would benefit Virginia port cities.

Farmers in the Shenandoah Valley and northwestern counties sought state support for rail connections to urban markets, which would increase profits from farming and raise land values. However, Eastern Virginia was politically dominant. Until the Civil War, Tidewater politicians were able to restrict the economic channels for most of the Shenandoah Valley to just Virginia outlets - but the Commonwealth of Virginia was willing to invest in railroads that connected the Shenandoah Valley to Virginia ports on the Fall Line.

Shenandoah Valley, without north-south railroads in 1852

Source: Library of Congress, "Map of the Virginia Central R.R. and its proposed connections (1852)

Virginia Central, from Rockfish Gap to Staunton (1852)

Source: Library of Congress, "Map of the Virginia Central Rail Road showing the connection between tide water Virginia, and the Ohio River at Big Sandy, Guyandotte and Point Pleasant

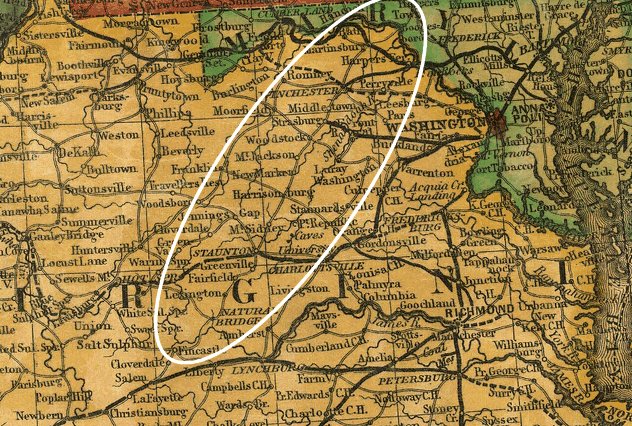

railroads in Shenandoah Valley, 1855 (note the gap between Winchester and Strasburg)

Source: Library of Congress - Williams' commercial map of the United States and Canada with railroads, routes, and distances (1855)

By the start of the Civil War, the Virginia Central railroad had connected the upper valley (near Staunton) to Richmond, and the Manassas Gap Railroad connected the middle of the Shenandoah Valley to Alexandria. Gundalows that once floated down the Shenandoah River to Harpers Ferry then stopped at Front Royal and transferred their products to the Manassas Gap Railroad, benefitting Alexandria merchants rather than Baltimore businesses.

Neither railroad crossing the Blue Ridge connected to the Winchester and Potomac; few Shenandoah Valley goods could reach Baltimore by rail. The result was an inefficient transportation system for the farmers and iron furnaces in the Shenandoah Valley, limiting competition, but the economic benefits of trade were concentrated in Virginia and "leakage" of profits to Maryland and Pennsylvania was limited.

The concept of an interstate trade network, or even regional rather than local service, would require the consolidation of separate railroad companies. That finally occurred through a series of mergers and hostile takeovers after the Civil War, when control of railroads shifted to non-Virginian capitalists. After the war, the General Assembly sold its stock in railroads to northern investors.

With the change in ownership, the focus on building railroads just to draw traffic to Tidewater ports shifted. Connections were built to move people and freight seamlessly across the state, rather than just to feed traffic into the selected port cities of Alexandria, Richmond, Petersburg, and Portsmouth/Norfolk. Northern companies were able to get railroad charters, and ultimately one built a railroad line through the valley.

The Shenandoah Valley Railroad was built to connect the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad to the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Shenandoah Valley Railroad was the first railroad to go entirely through the entire Shenandoah Valley from north to south. The Pennsylvania-based investors constructed a new rail line through the entire Shenandoah Valley, without raising capital from Virginians interested primarily in steering traffic to a particular port. After the Civil War, Virginia was desperate for economic development, even if it involved a connection to the Pennsylvania Railroad and Virginia-based traffic could end up boosting business at Philadelphia.

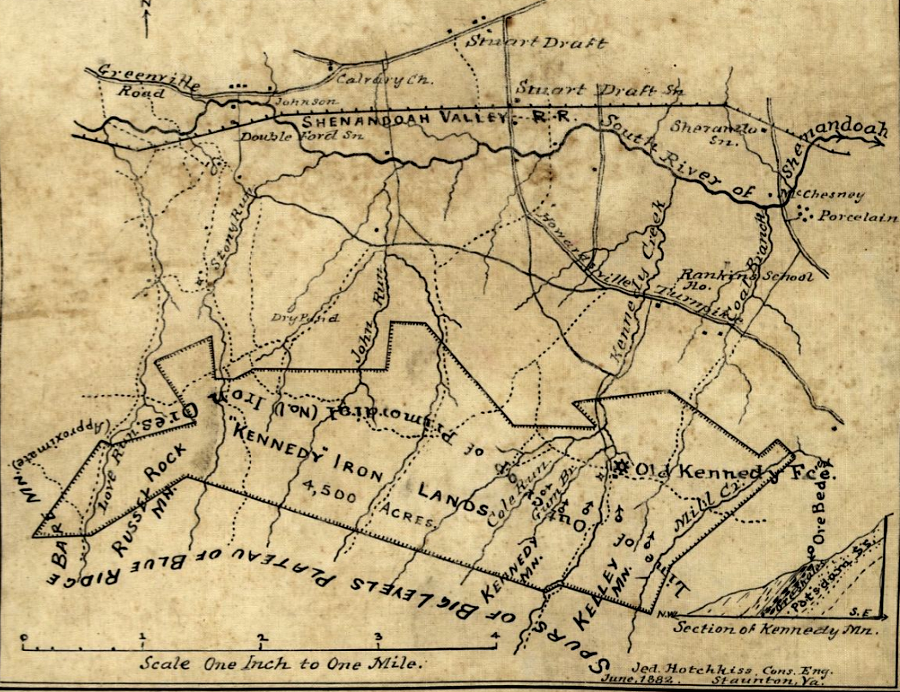

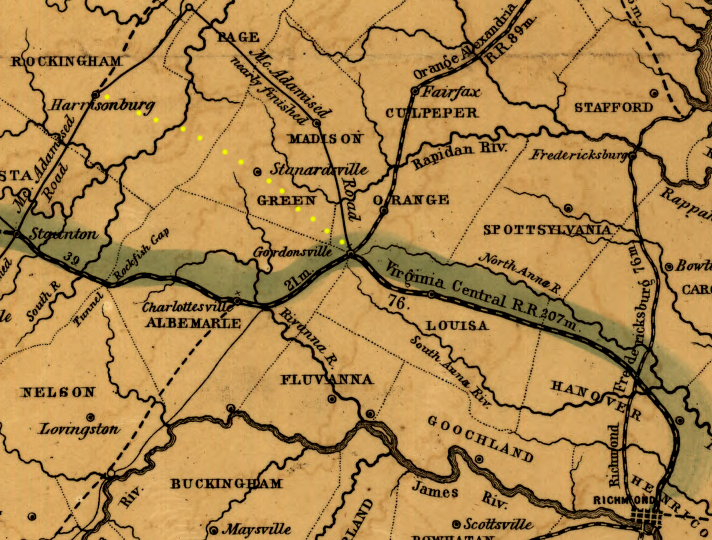

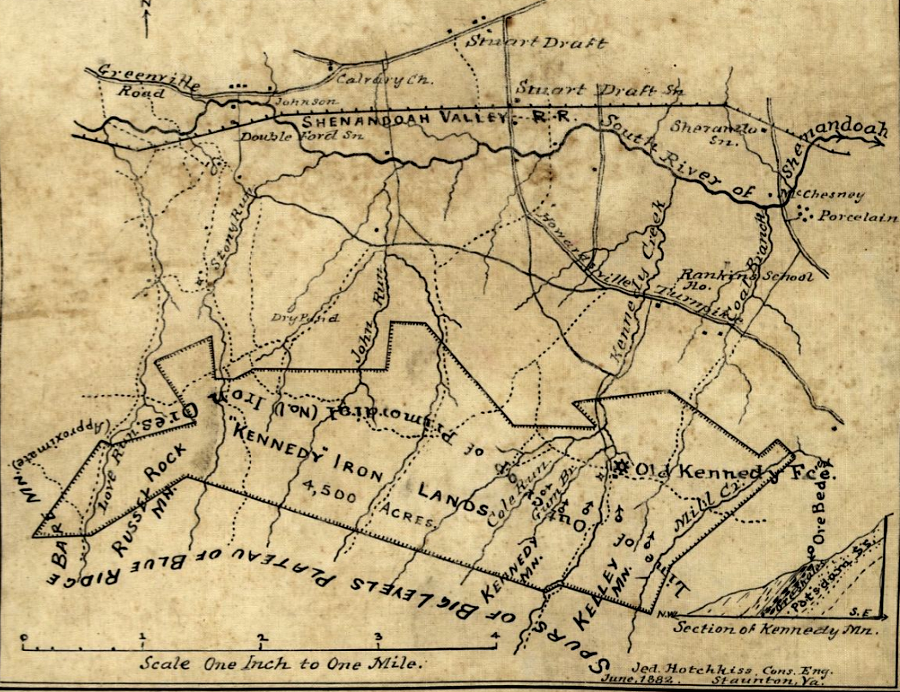

in 1882, Jedediah Hotchkiss mapped one of the tracts rich in iron ore on the western slope of the Blue Ridge that helped determine the railroad would run through Page Valley

Source: Library of Congress, "Kennedy" iron lands, 4,500 acres

The new line ran on the eastern side of Massanutten Mountain, through the Page Valley, because the iron furnaces were concentrated there.

Traffic to Harrisonburg and other towns on the west side of Massanutten Mountain was projected to be less profitable than freight business from the iron furnaces/forges at Shenandoah, Glasgow, Vesuvius, and other locations near the Blue Ridge. The Shenandoah Valley Railroad finally provided Harrisonburg and farmers/industrialists throughout the valley access to Philadelphia via a connection with the Pennsylvania Railroad at Hagerstown.

Competition between Baltimore and Philadelphia shaped the post-war expansion of railroad lines in the Shenandoah Valley. Initially, the Valley Rail Road was controlled by the B&O, while the Shenandoah Valley Railroad was controlled by the Pennsylvania Railroad.

While the Shenandoah Rail Road was being completed, the Valley Rail Road was built on the west side of the valley. Modern I-81 parallels that route today, and south of Staunton one of the stone bridges is still visible.

a bridge of the abandoned Valley Rail Road is visible from I-81 south of Staunton

Source: Abandoned in Virginia, "Facebook post (December 12, 2025)

The Valley Rail Road was designed to provide a connection to Baltimore via the B&O, starting from Staunton and heading north. That rail line linked Staunton to Harrisonburg, and Harrisonburg to Front Royal. At Front Royal, all Shenandoah Valley rail traffic crossed the Blue Ridge on the old Manassas Gap Railroad and moved north across the Potomac River via Alexandria.

The B&O focused its efforts on extending its line south from Winchester to Lexington. It financed the various projects that paralleled the Valley Pike on the west side of Massanutten Mountain, providing Harrisonburg its rail connection to Baltimore. After the financial recession of 1872, however, the B&O retrenched and was unable to extend the Valley Rail Road south of Lexington. The Valley Rail Road never started an extension from Harrisonburg north to Winchester, to establish a direct link to the B&O.

The rival Pennsylvania Railroad financed construction of the Shenandoah Valley Railroad on the east side of Massanutten Mountain, through Page Valley south of Front Royal to Waynesboro. That rail line follows the route of modern-day US 340, rather than Interstate 81. The route benefitted William Milnes, who owned the Shenandoah Iron Works at Milnes. (The town was renamed "Shenandoah" in 1890. Waynesboro is shown as "Basic City" on early maps, and Roanoke is shown as "Big Lick.")

Just as the B&O was affected by the financial recession in President Grant's second term, the Pennsylvania Railroad had to abandon some of its efforts to extend its rail system into the southern states after the Civil War. Philadelphia investors took over the Shenandoah Valley Railroad project, and the bankers were associated with William Milnes. The investors built their line east of Massanutten Mountain. Connecting with iron furnaces and forges at the base of the Blue Ridge generated more profitable traffic than the route through Harrisonburg, which was already controlled by the Valley Rail Road. Milnes built the Big Gem furnace on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River in 1882, once the railroad reduced transportation costs. After the Shenandoah Valley Railroad joined the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, the two lines were renamed the Norfolk and Western.

the Shenandoah Valley Rail Road bypassed Harrisonburg in favor of traffic from iron furnaces/forges east of Massanutten Mountain (and to avoid competition with the Valley Rail Road financed by the B&O)

Source: Library of Congress, "The Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia Air Line; the Shenandoah Valley R.R.; Norfolk & Western R.R.; East Tennessee, Virginia, & Georgia R.R. (its leased lines,) and their connections (1882)

Harrisonburg's last opportunity for a direct line across the Blue Ridge came at the end of the 19th Century, when a new railroad was built to haul coal from Rockingham County mines. A rail connection, ultimately named the Chesapeake Western Railway, was completed around the southern edge of Massanutten Mountain to the Norfolk and Western line at Elkton, but the cost of tunneling through the Blue Ridge blocked further expansion to the east.

Today, Harrisonburg's rail connections have withered. The old Valley Rail Road remained a cul-de-sac, and never grew into a main line of the Southern Railroad. Harrisonburg no longer has a direct railroad link south to Staunton or north to Front Royal.

The former Chesapeake Western Railway (locally known as the "Crooked & Weedy"), now part of the Norfolk Southern, connect with the mainline at Elkton. Poultry plants and other industries in the Harrisonburg area still have rail service.

Another shortline, recycling the name Shenandoah Valley Railroad, also offers rail service from Pleasant Valley (south of Harrisonburg) to Staunton. The Shenandoah Valley Railroad could exchange rail cars at Pleasant Valley so the Norfolk Southern would finish a haul to Harrisonburg, but that business is minimal. Most Norfolk Southern traffic to Harrisonburg comes by way of Elkton.

Instead, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad interchanges at Staunton with another shortline railroad, the Buckingham Branch. The Buckingham Branch shortline has leased the old Virginia Central (later Chesapeake and Ohio) tracks from Clifton Forge, through the Blue Ridge Tunnel, to Richmond. It is still possible for rail cars to come north from Staunton to Harrisonburg, using the old route of the Valley Railroad.

in 1879, the Shenandoah Valley had rail connections north to Baltimore and west to the Ohio River, while two railroads crossed the Blue Ridge to Alexandria and Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Rand, McNally & Co.'s Virginia and West Virginia (Rand, McNally and Company's business atlas, 1878-79)

CSX still maintains a connection to Strasburg in the Shenandoah Valley

Source: CSX, "CSX System Map

Links

- Abandoned Rails

- U S v. WINCHESTER & P R CO, 163 U.S. 244 (1896 Supreme Court case ruling that the Winchester & Potomac Railroad Company had no valid claim to the rails removed from the railroad in 1862 and sold by the Federal government in 1865)

- Library of Congress

- Map of the Manassas Gap Railroad and its extensions; September, 1855

- Map of the routes examined and surveyed for the Winchester and Potomac Rail Road, State of Virginia, under the direction of Capt. J. D. Graham, U.S. Top. Eng., 1831 and 1832; surveyed by Lts. A. D. Mackay and E. French, 1st Arty., assistants in 1831, and Lts. E. French and J. F. Izard, assistants in 1832; drawn from the original plot by Lt. Humphreys, 2d Artillery.

- A map of the Virginia Central Railroad, west of the Blue Ridge, and the preliminary surveys, with a profile of the grades.

- Rail Solution (rail alternative to adding four truck-only lanes to I-81)

the Norfolk and Western Railroad ran east of Massanutten Mountain, while the Baltimore and Ohio-controlled Valley Railroad was on the west side

Source: Library of Congress, Railway mail map of Virginia (Earl P. Hopkins, 1910)

original names of railroads in the lower Shenandoah Valley in 1891

Source: New York Public Library, Map showing the location of battle fields of Virginia (1891)

References

1. King, Ed, "Getting Them Up the Grade the Norfolk and Western Way," Trains Magazine, April 2004, p. 67

2. "Doctor Thomas Walker's Journal 1750," from Envisaging the West: Thomas Jefferson and the Roots of Lewis and Clark archive, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and University of Virginia Center for Digital History, http://jeffersonswest.unl.edu/archive/view_doc.php?id=jef.00073 (last checked January 21, 22015)

3. John Majewski, A House Dividing: Economic Development in Pennsylvania and Virginia Before the Civil War, Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp.61-63, http://books.google.com/books?id=RtvARIjfeP4C (last checked September 1, 2013)

4. Charles Ellett, "Railroad Across the Blue Ridge Mountains, Virginia US", Civil Engineer and Architects Journal, Volume XX, 1857, pp.190-191, http://books.google.com/books?id=gcNAAAAAcAAJ; "Ain't no mountain wide enough: To keep Crozet from tunneling a new attraction," The Hook, November 21, 2002, http://www.readthehook.com/92754/cover-story-aint-no-mountain-wide-enough-keep-crozet-tunneling-new-attraction (last checked January 21, 2015)

5. "A Brief History of Port Republic, Virginia," The Society of Port Republic Preservationists, http://www.portrepublicmuseum.org/history.html (last checked September 1, 2013)

railroads of the Shenandoah Valley before segments were abandoned north and south of Harrisonburg (click on image for larger view)

Source: USGS Seamless Data Viewer

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places