Waste Management in Virginia

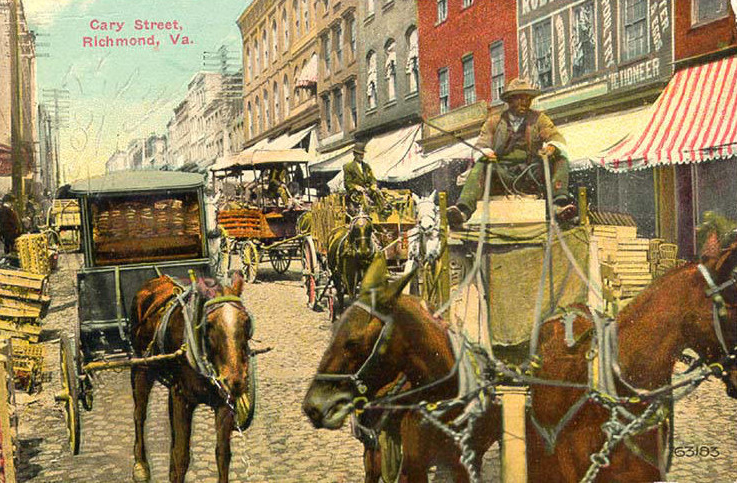

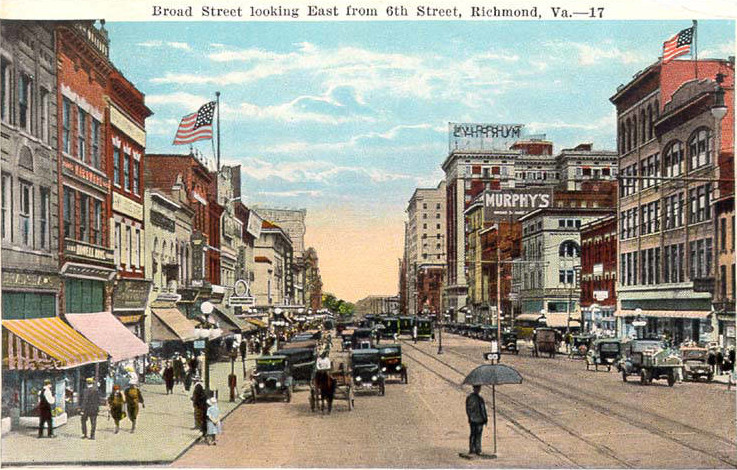

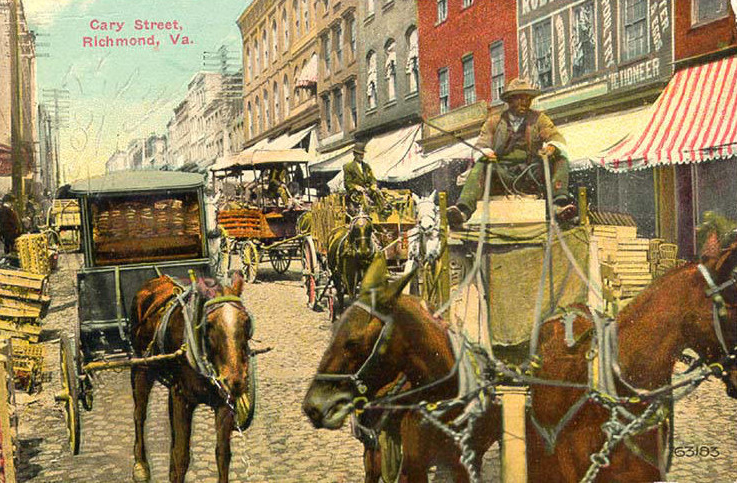

horse manure was ubiquitous on Richmond's cobblestone streets as electricity distribution lines were being constructed in 1911, but cars created the waste by 1927

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), Cary Street, Richmond, Va (1911) and Broad Street looking East from 6th Street, Richmond, Va. (1927)

Waste, by definition, is stuff that is not wanted. Since the first human tossed away plant stems and hair/bone from a meal site, we have been creating waste. In the stratosphere, concentrations of lithium, aluminum, copper and lead are increasing as satellites fall out of orbit and metal materials are vaporized during re-entry through the upper atmosphere.

What was once waste can become "wanted." Old newspapers become new paper. Glass is crushed to become aggregate used to cover landfills, or melted to become new glass. Recycled plastic water bottles are turned into park benches. Asphalt scraped off of highways is reprocessed to become new asphalt used for repaving other roads. Sawdust at lumber operations and furniture factories can be repurposed into pressed wood products.

litter on the James River, just below the Reusens hydropower facility near Lynchburg

Recycled paper ends up as cereal boxes, newspapers, even toilet paper. The short fibers in recycled paper produce a rough texture, so trees are pulped and processed directly into the soft, plush rolls purchased for most American homes. Customers using public restrooms, such as sports stadiums, can't make a choice of toilet paper and may notice the different "feel" of the recycled fibers in the toilet tissue.1

Sawmills across Virginia used to burn sawdust as a waste product, creating towers of smoke from wigwam-shaped burners. When air quality controls forced the sawmill operators to find an alternative disposal technique, a market developed for pressed wood. Many kitchen counters today consist of a thin layer of Formica, on top of sawdust which has been pressed and glued into a layer of wood that is strong enough to support all the things we put on top of kitchen counters. Larger pieces of wood waste is now glued into sheets of "oriented strand board" (OSB) that competes with plywood.

The next "opportunity" to convert a waste product into something with value: carbon dioxide. Today, it is released into the atmosphere from industrial operations and power plants burning fossil fuels, such as coal. Political pressure to address global warming concerns is likely to classify CO2 as a regulated pollutant in the future - and that may trigger new ways to use the carbon dioxide to create a product that has value, rather than a cost for disposal as waste.

old wigwam burner, for sawdust

Where do Virginians send the stuff they don't want? We recycle some of it, but we put the rest into the air, ground, or water. The only other choice: blast waste into space. That's not an option we use now, not even for highly-radioactive nuclear wastes.

a "bandalong" traps litter near the mouth of Neabsco Creek in Prince Wiliam County that volunteers then haul away (photos courtesy of Neil Nelson)

Humans are already cluttering up the area available for satellites in Low Earth Orbit. In 2004, the Federal Communications Commission assumed responsibility for regulating orbital debris, but the risk of collisions has increased regularly since then.

Starting with Sputnik in 1957, rockets launched 50,000 tons of material into space; 10,000 tons have remained in orbit. The successful privatization of space launches by 2020, particularly for creation of the Starlink communications system by SpaceX, triggered a rapid increase in the number of satellites and associated residue in orbit.

Each year the increase in the number of even small particles, each traveling at 17,500 miles per hour, increased the probability for catastrophic collisions. The worst case scenario, known as the Kessler syndrome, was that space debris would make it unrealistic to place new satellites into low earth orbits.

The European Space Agency announced the Zero Debris Charter initiative in 2023 and noted then:2

- ...130 million pieces of space debris larger than a millimetre orbit Earth, threatening satellites now and in the future. Once a week, a satellite or rocket body reenters uncontrolled through our atmosphere. Behaviours in space have to change.

waste management is a problem in outer space, where satellites are threatened by collisions with particles of orbiting debris

Source: European Space Agency, World-first Zero Debris Charter goes live

Waste produced by Virginians may go out of sight and out of mind, but waste does not go away. All waste ends up being re-used, or ends up as pollution in the air, ground, or water.

- When Arlington County/Alexandria burns their solid waste in an incinerator, it minimizes water and ground pollution...but some percentage of gases escape the filters on the smokestacks and pollute the air.

- When Manassas sends its solid waste to a modern sanitary landfill, some gases and liquids escape the "cell" and must be processed. Methane in landfill gas is so common, both Fairfax and Prince William burn it to generate a small amount of electricity... and then exhaust the carbon dioxide and other combustion remnants into the atmosphere.

- When Fairfax County processes the sewage flushed downstream from the Fairfax Campus of George Mason University (at the Cole Wastewater Treatment Plant in Lorton), most "poop" is decomposed by bacteria and the nitrogen in the water is released as N2 molecules into the atmosphere. Solids that do not decompose as the sewage moves through the plant, mostly sludge from the bottom of the bacteria-filled decomposing tanks, are burned in an incinerator - generating lots of gases that go into the air, and a small amount of ash that goes into a landfill.

- Emissions from tailpipes of cars rise up into the atmosphere as gases, but then air-born particles from the tailpipes are absorbed by raindrops and re-deposited back on the ground. Much of the mercury pollution in our waterways comes from coal-fired power plants, where the traces of mercury in the coal are gasified during combustion, transferred across Virginia by air currents, then rained back into the creeks and the Chesapeake Bay. The atoms and molecules of mercury never "go away;" they just get transformed and transferred by our processing.

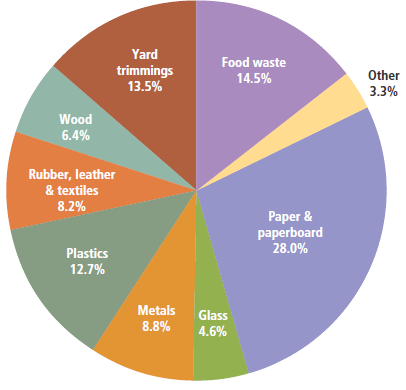

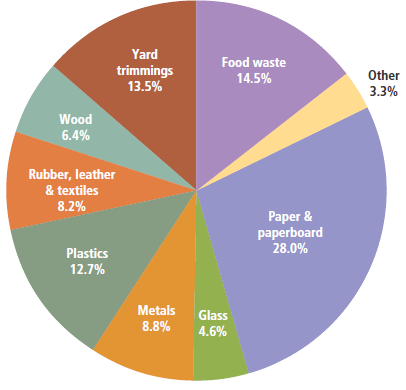

250 Million Tons of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) generated in 2011, measured by weight before recycling (over 50% of waste came from paper and paperboard, food scraps, and yard trimmings)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Municipal Solid Waste in The United States: 2011 Facts and Figures (Figure 5)

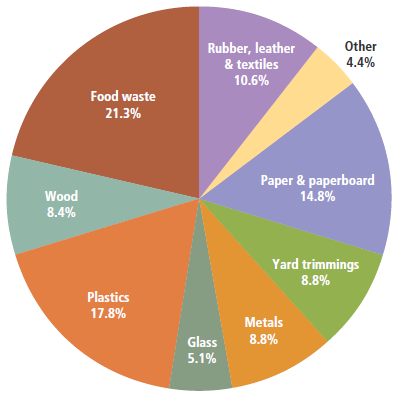

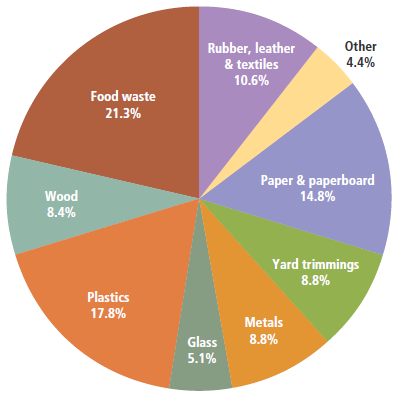

164 million tons of Municipal Solid Waste after recycling and composting in 2011 (a high percentage of paper/paperboard and yard waste are recycled, but most food waste remains... waste)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Municipal Solid Waste in The United States: 2011 Facts and Figures (Figure 7)

We can shift waste from disposal in water to dissemination in air. We can build better scrubbers that minimize air pollution, but leave us more residue in "baghouse" filters that must be disposed of in the ground (in landfills). We can avoid putting solid waste into landfills by incinerating it, but that creates more air pollution.

We can reduce/reuse/recycle to minimize pollution. The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) has found a way to recycle the 50,000 animals killed annually on the state's highways. Traditionally, animals were hauled to the nearest landfill, which charged $60-100 per deer mixed in with the municipal solid waste. Starting in 2012 near Salem and Halifax, VDOT built composting bins with forced air jets (and occasional additions of moisture) to help bacteria naturally decompose the carcasses. Thanks to microbial activity, temperatures can reach 160 degrees in the bins, killing most pathogens and eliminating most odors. For some VDOT offices, the savings will equal the initial cost within five years.3

What we can not do: we can not eliminate "waste." We can only manage where we put it, and in what form. Putting waste underground, or dissolving it into the water, or converting into gas, may disguise the existence of a waste product but does not make waste "go away."

where does soil that washes off a construction site end up? (Answer: the nearest stream...)

Waste management is not a new issue. The first sanitation law in Virginia was issued in 1610, as part of the "Lawes Devine, Morall, and Martiall" to control pollution in the three-year old colonial settlement at Jamestown:4

- There shall no man or woman, Launderer or Launderesse, dare to wash any vncleane Linnen, driue bucks, or throw out the water or suds of fowle cloathes, in the open streete, within the Pallizadoes, or within forty foote of the same, nor rench, and make cleane, any kettle, pot, or pan, or such like vessell within twenty foote of the olde well, or new Pumpe: nor shall any one aforesaid, within lesse then a quarter of one mile from the Pallizadoes, dare to doe the necessities of nature, since by these vnmanly, slothfull, and loathsome immodesties, the whole Fort may bee choaked, and poinsoned with ill aires, and so corrept (as in all reason cannot but much infect the same) and this shall they take notice of, as shall be thought meete, by the censure of a martiall Court.

Mining debris, such as tailings piles, are rare in Virginia. You can still find a tiny residue of slag and iron ore left over from iron furnaces that operated in the 1700's and 1800's. Contrary Creek (a tributary of Lake Anna) and Quantico Creek (in Prince William County) were damaged by acid mine drainage triggered by mines that extracted pyrite for its sulfur. It was not until the advent of strip mining for coal that waste material from mining would dominate a substantial part of the landscape of Virginia.

In the early 1900's, a Virginia state legislator reportedly said "The rivers of Virginia are the God-given sewers of the State." His assumption was that the solution to pollution was dilution in the river, and the capacity of the river to spread the pollution downstream where waste would "disappear."5

As the population of Virginia has increased, the amount of pollution we put into the waterways has increased. We have exceeded the natural capacity of streams to dilute pollution or to carry it away. Instead, streams (and even the Chesapeake Bay itself) are dying, because we have overloaded the waterways with excessive amounts of nitrogen, phosphorous, sediment, and occasionally a specific waste product from a manufacturing operation. (After discovering the dangers of the residue from manufacturing the pesticide Kepone in Hopewell, fishing was banned in the James River for 98 miles between Richmond and the Chesapeake Bay from 1975-1989.)

Especially since the 1960's, Federal and state laws and regulations have been increasingly strict on controlling how waste is managed. As a result, backyard dumps, "straight pipes" from toilets and manufacturing plants to rivers, and inefficient treatment facilities have been replaced by relatively-expensive treatment plants. At the same time, we are still spreading waste (biosolids) on agricultural fields as a soil conditioner.

outfall of clean water at Loudoun County's Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility

In 2012, Virginia had 206 permitted solid waste management facilities in operation, up from 195 in 2007.6

Few communities welcome the development or expansion of waste management facilities nearby. Those who object to facilities being built in their neighborhood may be driven by self-interest, but who is that surprising? There are numerous acronyms for those who object to locating LULU's (Locally Unwanted Land Uses) such as dumps, incinerators, sewage treatment plants, etc. in a particular area. NIMBY stands for "Not in My Back Yard," CAVE stands for "Citizens Against Virtually Everything," BANANA stands for "Build Absolutely Nothing Near Anyone" - and NOPE stands for "Not on Planet Earth."

One political issue is the claim that unwelcome public facilities are concentrated in areas with high concentrations of poor and minority residents. "Environmental justice" advocates contend that the placement of public facilities reflects underlying racism, while others debate the claim or suggest that low land acquisition costs are the primary determinant (not racism) for locating such facilities.

There are cases where the LULU's are closer to the rich than the poor. For example, the upper-class Montclair community in Prince William County is located downstream from the county landfill. Powells Creek drains the landfill area before it flows into Lake Montclair. Houses with lakefront property have a higher value, and the development has a popular beach where kids swim in the lake... and in the lake will be any leachate that flowed downstream from the landfill.

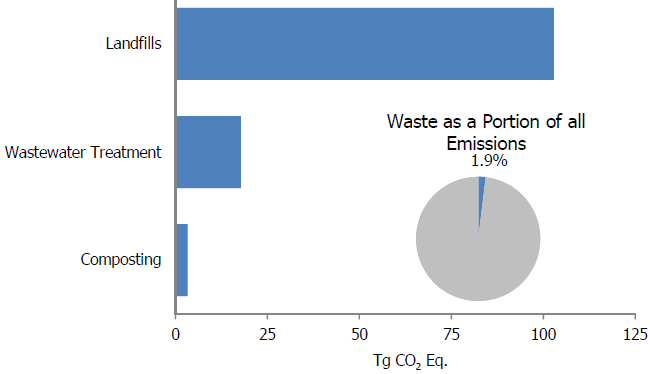

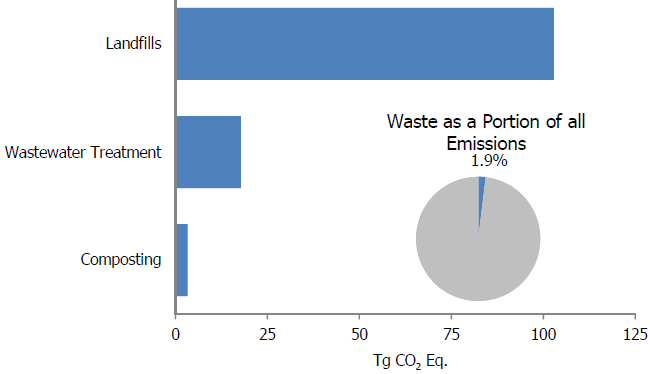

landfills, wastewater treatment plants, and composting generate less than 2% of the greenhouse gases in the United States

(measured in teragrams - million metric tons - of carbon dioxide equivalent)

Source: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data - Waste (Figure 8-1)

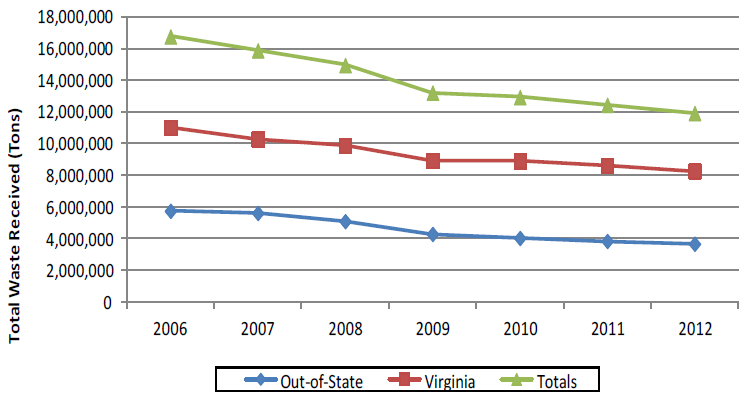

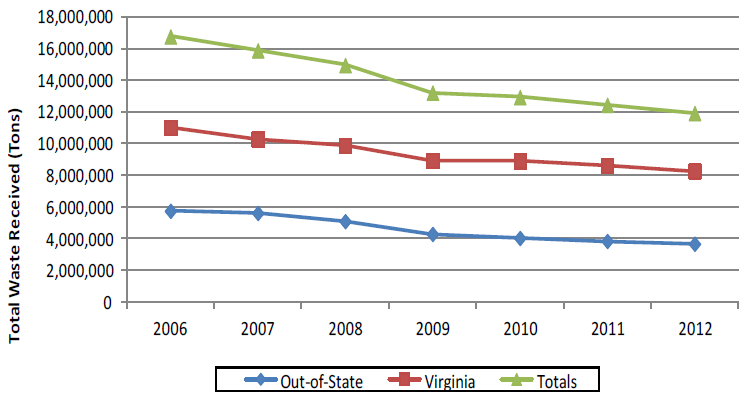

Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) received in Virginia, 2006-2012

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Solid Waste Managed in Virginia During Calendar Year 2012

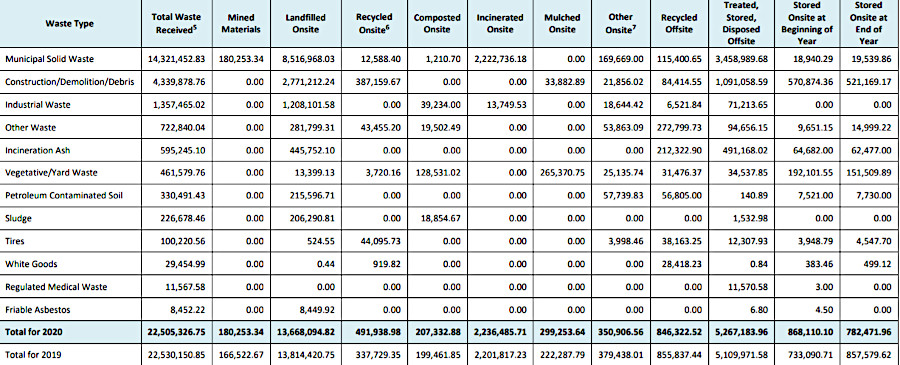

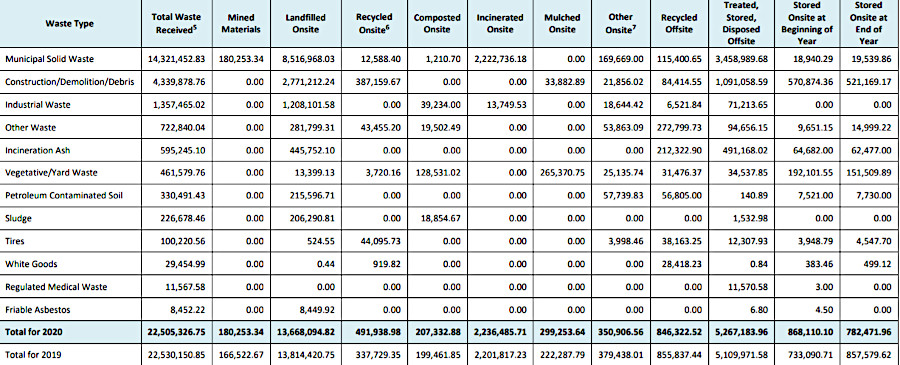

types of solid waste managed in Virginia in 2020 (in tons)

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2021 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2020 (Table 1)

Links

References

1. "Mr. Whipple Left It Out: Soft Is Rough on Forests," The New York Times, February 25, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/26/science/earth/26charmin.html; "Burned-up space junk pollutes Earth's upper atmosphere, NASA planes find," Space, October 19, 2023, https://www.space.com/air-pollution-reentering-space-junk-detected (last checked November 5, 2023)

2. "The FCC's authority in regulating orbital debris," The Space Review, November 6, 2023, https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4687/1; "The Zero Debris Charter," European Space Agency, https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2023/06/The_Zero_Debris_Charter; "World-first Zero Debris Charter goes live," June 11, 2023, https://vision.esa.int/world-first-zero-debris-charter-goes-live/ (last checked November 9, 2023)

3. "Composters transform roadkill into landscape," The Roanoke Times, October 12, 2013, http://www.roanoke.com/news/2290647-12/composters-transform-roadkill-into-landscape.html (last checked October 12, 2013)

4. Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, Article 1-22, http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/jamestown-browse?id=J1056 (last checked November 6, 2009)

5. "An Environmental History," Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, http://www.deq.virginia.gov/history/earlydays.html (last checked November 6, 2009)

6. "Solid Waste Managed in Virginia During Calendar Year 2012," Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, June 2013, http://www.deq.virginia.gov/Portals/0/DEQ/Land/SolidWaste/2013_Annual_Solid_Waste_Report.pdf; "Waste Reduction Efforts in Virginia," Senate Document No. 14, 2008 by Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, p.ii, http://jlarc.virginia.gov/reports/Rpt376.pdf (last checked October 12, 2013)

emissions stack at Possum Point power plant, on Potomac River at Dumfries (Prince William County)

Economics of Virginia

Virginia Places