fuel assemblies from four commercial nuclear power reactors generate most of the high-level radioactive waste in Virginia

Source: Department of Energy, Yucca Mountain

fuel assemblies from four commercial nuclear power reactors generate most of the high-level radioactive waste in Virginia

Source: Department of Energy, Yucca Mountain

Virginia produces two types of nuclear waste, low-level and high-level radioactive waste. None of Virginia's radioactive waste is recycled or reprocessed; all of it is intended to be isolated for thousands of years at special disposal sites.

Low-level radioactive waste includes radioactively contaminated protective clothing, tools, filters, and rags from nuclear power plant maintenance and operations, plus some medical facility wastes and a few other items. Low-level waste is categorized into three classes.

Class A wastes have the lowest concentration of radioactive materials, mostly materials with half-lives of less than five years. Class B wastes have longer half-lives than Class A materials, while Class C wastes have longer half-lives than Class B materials.

Mill tailings, yet another form of radioactive waste, could be produced if Virginia ever permitted mining of the rich uranium deposit at Coles Hill in Pittsylvania County.

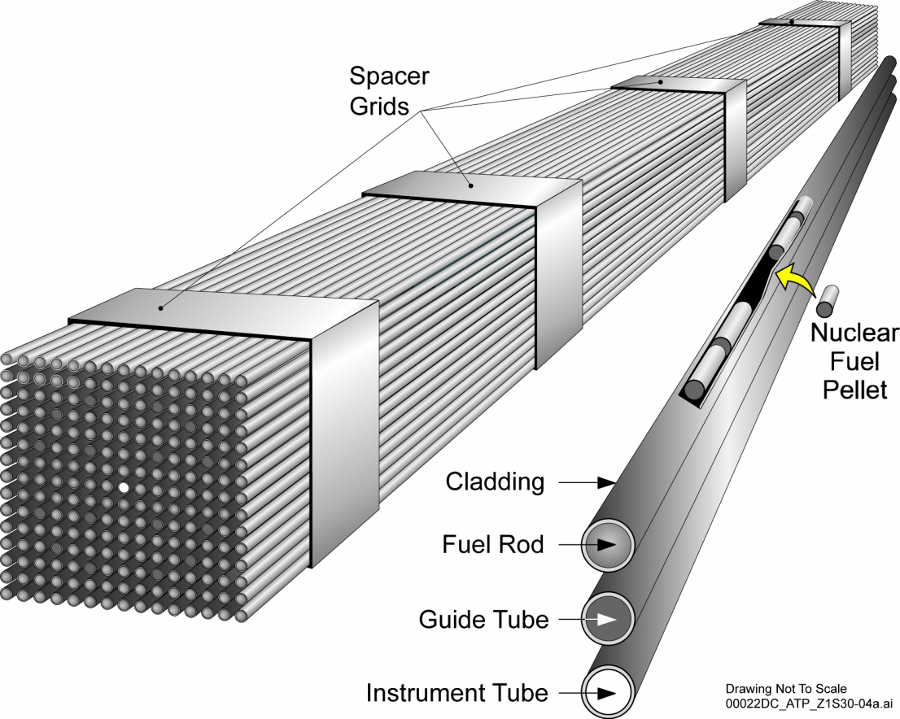

States have created compacts for sharing the responsibilities of nuclear waste disposal. The theory was that each compact would identify a location for storing low-level nuclear waste. Members would negotiate which state would allow such a site, and how other states would compensate the host state for its willingness to accept material that was feared by the general public because it was labelled "radioactive."

The multi-state compacts have evolved over time. South Carolina originally accepted radioactive wastes from Virginia, but the terms of the compact changed.

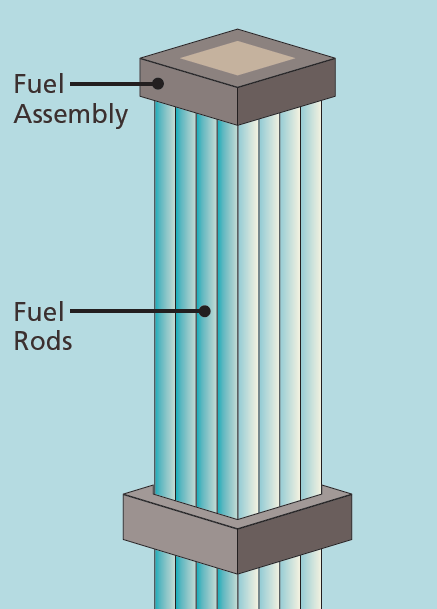

Until 2008, Virginia companies could ship low-level radioactive waste to Barnwell, South Carolina for disposal. Since 2008, Virginia's low-level Class A radioactive waste has been transported to Clive, Utah. Since 2012, a facility in Andrews, Texas has been willing to accept Class A, B, and C waste.

states have compacts for radioactive waste disposal, but four disposal sites have become dominant

Source: U.S. Department of Energy, Waste from Nuclear Power Plants

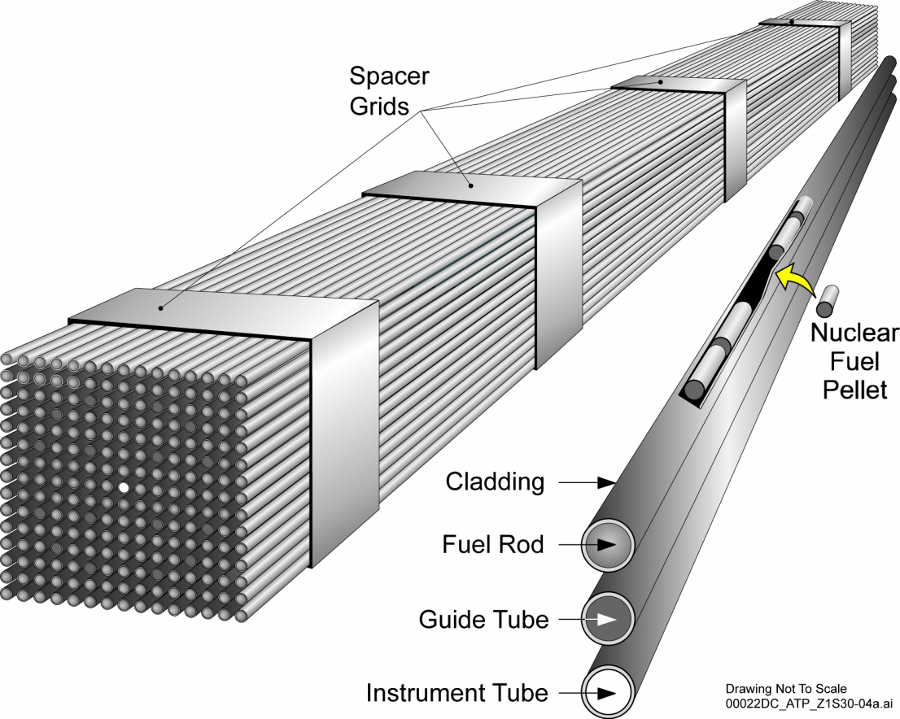

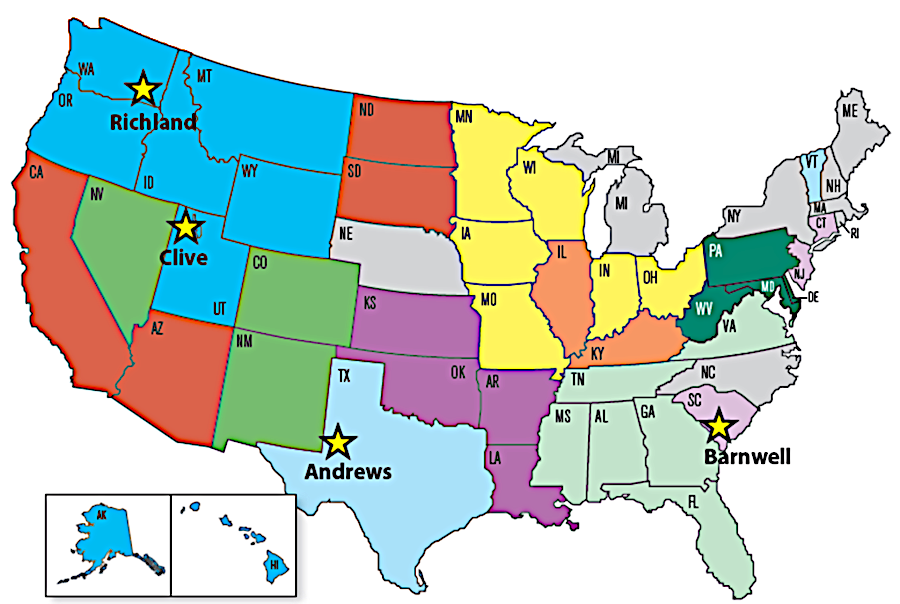

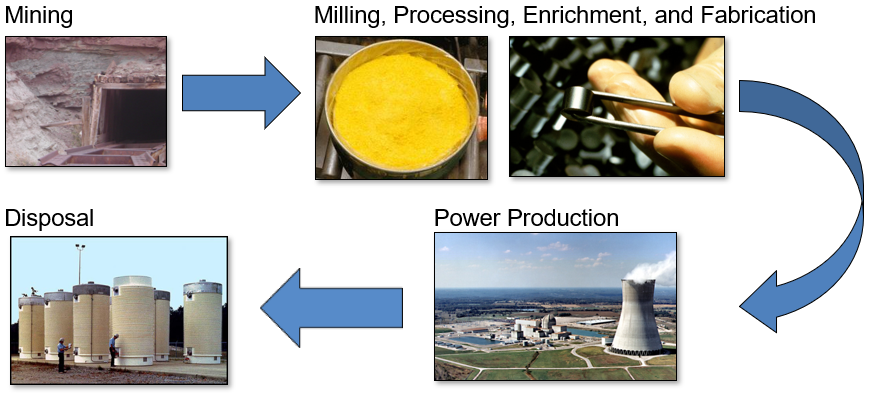

"High-level" radioactive wastes, with half-lives that exceed those of Class C wastes, is classified as Greater Than Class C (GTCC). In Virginia, most high-level radioactive waste comes from nuclear power plants. Virginia's four civilian reactors "burn" uranium pellets that were placed in fuel rods, and carefully aligned in fuel assemblies, to produce electricity. When a certain percentage of the uranium has decayed, the spent fuel assemblies are removed from the power plant reactors and replaced. The removed fuel assemblies are treated as high-level radioactive waste.1

radioactive pellets are loaded into fuel rods, and multiple rods are aligned together to create a single fuel assembly

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Safety of Spent Fuel Storage (p.1)

In addition to the residual radioactivity of the U-235 in reactor fuel pellets, the metal in the assemblies has been "activated" by neutrons and has also become radioactive. The iron-55, cobalt-60, nickel-63, carbon-14, and caesium-137 isotopes are the radioactive elements:

Irradiated fuel assemblies emit dangerous gamma rays, especially for the first 50 years after removal from a reactor. To intercept the radiation and disperse heat, spent fuel assemblies are typically stored underwater. After normal radioactive decay, the assemblies may be moved from the "wet storage" pools and transferred into "dry casks." Those are concrete cylinders that may be stored on land, freeing up space in the pool for hotter fuel assemblies.2

the nuclear fuel cycle ends with highly radioactive waste stored temporarily at two sites in Virginia

Source: U.S. Department of Energy, Waste from Nuclear Power Plants

The AREVA and BWXT facilities in Lynchburg have fabricated fuel assemblies used in commercial and US Navy nuclear power reactors. Those assemblies are radioactive, but when first produced they are valuable products rather than "waste."

The production of fuel assemblies, with pellets of highly enriched uranium, does generate low-level radioactive waste that must be handled differently from standard municipal solid waste. No high-level or transuranic waste is generated in the initial production of the fuel assemblies, but BWXT generates other high-level waste in Lynchburg from its research on reactors used by the US Navy.

Nuclear reactors provide power for new aircraft carriers and submarines built at Newport News. Fuel assemblies are installed in the reactors when a ship is built. Later, when aircraft carriers go through Refueling and Complex Overhauls, spent fuel assemblies are removed and fresh ones (with more U-235) are installed. Between 1964-2016, refueling involved moving assemblies from nuclear-powered cruisers and aircraft carriers into a specialized Surface Ship Support Barge (SSSB), which the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company made from a converted World War II tanker.

The Surface Ship Support Barge provided a spent fuel pool comparable to what is built at commercial nuclear power plants. Since 2016, spent fuel modules have been moved directly from US Navy ships into shipping containers for transport to disposal sites. The Surface Ship Support Barge was towed to the Alabama Shipyard and dismantled in 2023.

The used fuel assemblies, with highly-radioactive activated metal now emitting gamma rays, are shipped to the Naval Reactors Facility at the Department of Energy's Idaho National Laboratory. Used assemblies are examined there, then stored in the Expended Core Facility/Dry Storage Facility managed by the Department of Energy. Between 1986-2023, 142 reactor compartment packages from nuclear-powered submarines and cruisers were been processed for disposal.

The US Navy has not sent a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier through the disposal process, yet. The decommissioned aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CVN-65) stayed at the Newport News Shipyard after its reactors were removed in 2013. For submarines, after removing the radioactive fuel assemblies the hull has been towed to Bremerton. There the section of the ship containing the propulsion plant's reactor, which was still radioactive even without fuel, was cut out and shipped to US government disposal sites.

The US Navy preferred towing the hull of the USS Enterprise to a commercial shipyard rather than Bremerton for partial dismantling. The commercial shipyard would expected to send large sections, with the still-radioactive compartments that once surrounded the reactors, to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. The radioactive pieces dismantled there would be transported to Hanford, Washington, for permanent burial at the Department of Energy storage site. Breaking up the USS Enterprise at a commercial shipyard was expected to cost less and to be completed in five years, compared to 15 years at a US Navy shipyard.

The US Navy studied the option of having a commercial shipyard totally dismantle the old USS Enterprise rather than remove compartments that once surrounded the reactors at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. That option was not pursued because the Hanford site would not accept radioactive waste from a non-government facility.3

Multiple ships with nuclear reactors are based at Naval Station Norfolk. Low-level waste is created during standard maintenance operations there. That low-level radioactive waste is transported, about once each month, to commercial disposal sites in Texas or Utah.

When the SM-1 reactor at Fort Belvoir was decommissioned, the old Reactor Pressure Vessel was shipped in November 2023 to the site in Andrews County, Texas managed by Waste Control Specialists (WCS). The vessel was buried in the Federal Waste Cell as Class B low-level radioactive waste.4

decommissioning of the SM-1 reactor at Fort Belvoir involved shipping the Reactor Pressure Vessel to Texas for permanent disposal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, SM1 Stakeholder Update: November 2023

Virginia faces fewer challenges with nuclear waste disposal than some other states. There has never been nuclear weapons production or plutonium production in Virginia. The state has never had a site used for reprocessing spent fuel assemblies.

In the 1950's, depleted and normal U238 uranium was used at what is now Naval Support Facility Dahlgren to develop a lightweight case for carrying nuclear weapons on US Navy aircraft. As part of Project ELSIE, barbettes (tubes of thick steel cut from old battleships) became slightly radioactive. One was left untouched at Dahlgren for years, since the history of how it became radioactive had been lost and the risks of moving the barbette were not clear. By chance, a retired worker revealed how the barbette had been used, which led to its final removal.5

In the United States, most transuranic waste was generated from the production of plutonium at the Hanford Nuclear Site in the state of Washington during World War II and the Cold War. The US Government faces a massive challenge now in stabilizing wastes in tanks filled with liquid and crystallized material, plus sludge. Different tanks have complex chemistries, and some have leaked. In addition, spent reactors from nuclear-powered warships (but not spent fuel facilities) are buried at the Hanford Nuclear Site. Hanford may be the most toxic place in America.

Transuranic wastes produced by the Department of Defense and its contractors - but not from commercial nuclear power plants - have been stockpiled at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, and at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas. The Pantex site is the US Department of Energy's primary facility for assembly, dismantlement and maintenance of nuclear weapons. The Savannah River Site was intended to be the home of the Mixed Oxide (MOX) Fuel Fabrication Facility, where plutonium would be reprocessed for use in power plants.

After construction of the MOX plant in South Carolina was cancelled, the US Department of Energy adopted a different strategy for disposal of most defense-related plutonium.

Current proposals are to "downblend" the high-level waste by mixing most of it with other material, then ship the waste in casks to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico. The New Mexico facility has been designated as the national repository for such material, a 2,000-foot-thick salt bed at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in Carlsbad, New Mexico. In addition, one metric ton of plutonium from the South Carolina site will end up as Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, where new cores for plutonium weapons could be produced.6

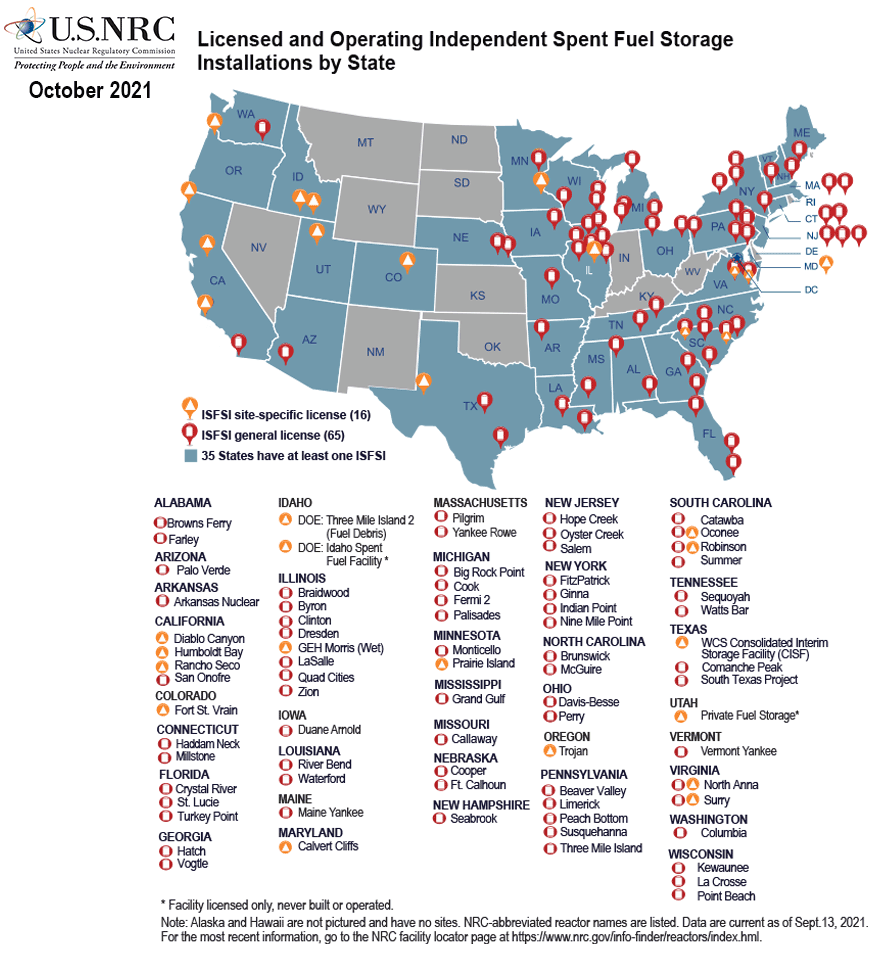

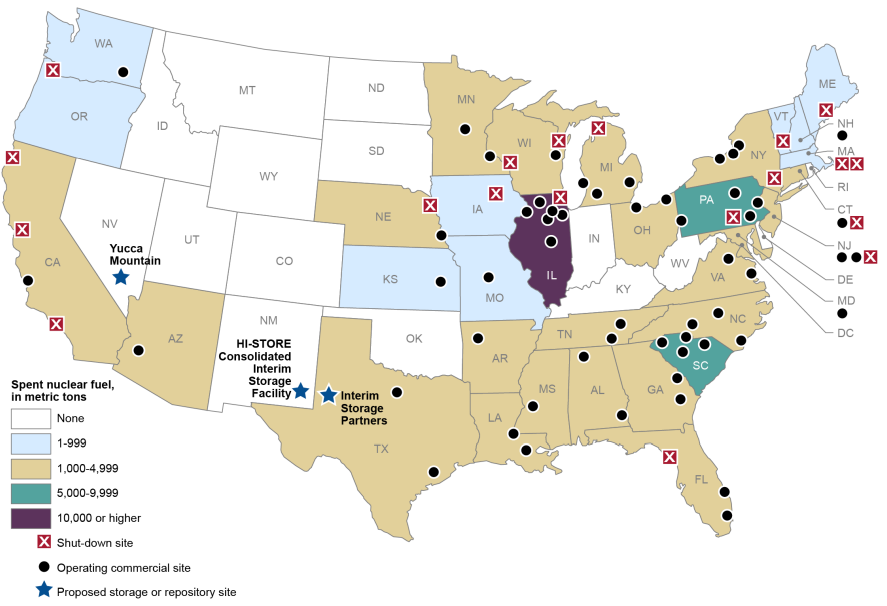

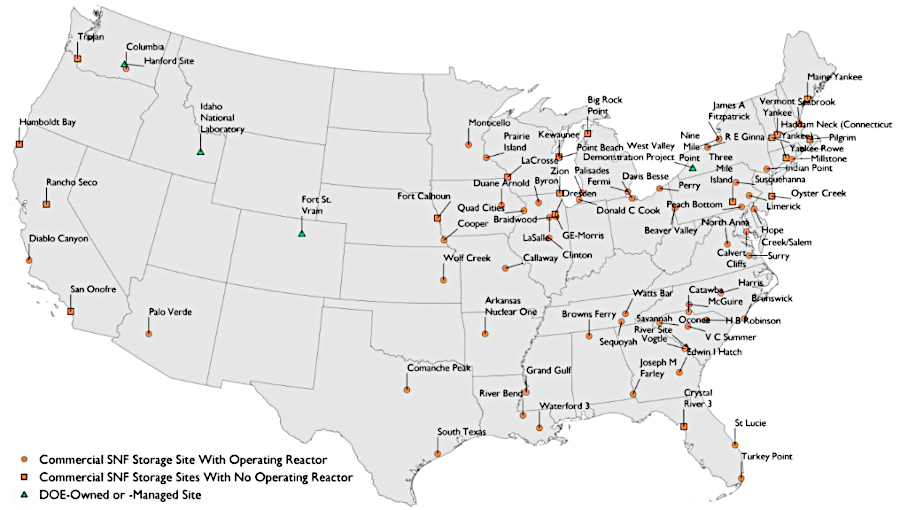

Virginia has high-level nuclear wastes, primarily spent fuel assemblies from commercial nuclear power plants. At the end of 2019, spent fuel assemblies were stored at 75 operating or shut-down commercial nuclear power plants in 33 states. There were 86,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel which had been produced by commercial power plants in the United States.

A 2024 report by the US Department of Energy identified three categories of waste storage sites:

By the end of 2022, nuclear waste was stored at over 100 sites in 39 states:

Commercial Nuclear Power Reactor (NPRs) and/or Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installation (ISFSIs) had generated waste totaling 90,963 metric tons of heavy metal (MTHM). That waste was kept in 3,862 nuclear fuel canisters/casks in dry storage.

An additional 2,479 MTHM of spent nuclear fuel was in storage at Department of Energy sites, and 1 MTHM was stored at other research sites (universities, other government agencies, and commercial research centers).7

At the end of 2019 there were 1,562 metric tons stored outside within dry casks at North Anna and another 1,562 metric tons at the Surry nuclear power plant, for a total of 3,124 metric tons stored in Virginia. The 2024 report indicated there were 28 canisters with 896 assemblies at North Anna. At Surry, there were 55 canisters with 1,470 assemblies.

BWX Technology (BWXT) in Lynchburg had 44 kilograms of spent nuclear fuel, used for its research projects.

once loaded with spent fuel assemblies, dry casks are moved to an outdoor pad for temporary storage at Surry Power Station

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Safety of Spent Fuel Storage (p.7)

By the time all current nuclear power plants close at the end of their life cycle, the Government Accountability Office estimates there will be a total of 140,179 metric tons of waste in the United States needing a place for permanent storage. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) estimated in 2016 that there were 260,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel in interim storage across the world. Of that total, 70% was kept cool in wet storage ponds. Most of the remaining 30% was decaying within dry casks.

The volume of space required for storing that amount of high-level radioactive waste is small, though the material must be spread out to allow heat to dissipate. In 2022, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute (without accounting for the need to space out the waste):8

Nuclear waste is stockpiled at sites where, ideally, nothing ever happens. As described by the manager of one Independent Spent Fuel Storage Facility:9

Virginia is one of 35 states where spent fuel facilities are stored at sites of operating/decommissioned nuclear power plants

Source: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Licensed and Operating Independent Spent Fuel Storage Facilities By State

High-level nuclear waste generated in Virginia was supposed to be shipped out of state for permanent storage. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a license in 2006 to Private Fuel Storage for temporary storage at the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Reservation in Utah, but the facility was never built. Federal plans for a permanent high-level nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada were cancelled in 2010.

Since dropping plans for Yucca Mountain, the Federal government has not defined any alternative location. Dominion Virginia Power has been forced to store all of its high-level waste, including waste classified as Greater Than Class C (GTCC), on-site at the Surry and North Anna power plants.

Failure to open a permanent storage facility not only imposed a burden on utilities managing high-level nuclear waste at power plants; it also increased costs to the Federal government, which had to compensate the utilities. Decentralized storage, with scattered guards and fences, increased the risk of a terrorist attack as well.

In 2021 the Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved a new temporary storage facility proposed by Interim Storage Partners. It was located adjacent to the low-level radioactive waste disposal site in Andrews, Texas operated by Waste Control Specialists since 2012. The company planned to accept 40,000 metric tons of fuel. Waste would be stored on or near the surface in canisters and casks for up to 40 years until transfer to a Federally-operated permanent facility, where 0anisters and casks would presumably be buried at least 1,000 feet underground.

a proposed temporary high-level nuclear waste storage facility would have been located next to an existng low-level waste facility operating since 2012 in Andrews, Texas

Source: Waste Control Specialists, Texas Compact Waste Facility (CWF)

Oil and gas companies and the State of Texas objected to the project, which was located in the Permian Basin. Any release of radioactivity could create a public perception that the oil and gas was contaminated. In addition, even a partial solution to the nuclear waste problem could increase public support for building new nuclear power plants which would not rely upon fossil fuels to generate electricity.

In 2023, a Federal court invalidated the license. The court determined that the agency did not have the legal authority under the Atomic Energy Act to issue a license for a private spent nuclear fuel storage facility not at sites of nuclear reactors.

The court decision and other legal issues delayed opening another facility that had obtained a Nuclear Regulatory Commission license for temporary storage. The HI-STORE CISF (Consolidated Interim Storage Facility), proposed by Holtec International, was in New Mexico and also in the Permian Basin. It could hold 170,000 metric tons of used fuel, twice the amount of all the high-level waste currently stored at nuclear power plants.

The company claimed:10

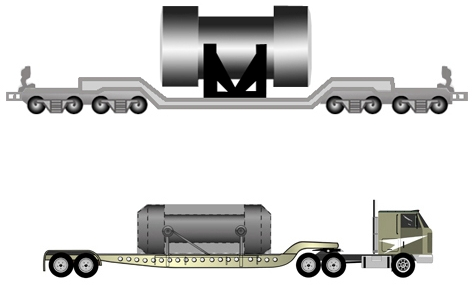

placards identify radioactive shipments

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation, Radioactive Material Regulations Review

Idaho officials have worried that nuclear materials sent for research at the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory (now the Idaho National Laboratory) and the Naval Reactors Facility could lead to the state becoming a de facto storage site. In 1995, the U.S. Department of Energy signed an agreement to end lawsuits. It required shipping most transuranic waste at the laboratory to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico, limited the amount of nuclear waste that the Department of Energy could keep in Idaho, and blocked shipments of shipments of used fuel from commercial nuclear power plants.

In 2025, the state and Federal agency approved a waiver of the agreement that authorized shipping a "high burnup" nuclear fuel cask from North Anna to the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory. Research on the condition of the cask, to be transported from North Anna by train in 2027, would assess the capacity of casks to continue storing used fuel assemblies at 54 nuclear power plants in 28 states until the Federal government established a national repository.11

Radioactive leaks in Virginia could create waste material, but such leaks are rare. In 1982, a fire in a storage building at the Surry nuclear power plant burned waste with low levels of radioactivity. Smoke and water from the building exceeded the thresholds set by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission by a tiny level, no more than .02 percent higher than the acceptable level.

In 2000, a leak was discovered in a pool at the BWXT site in Lynchburg where irradiated reactor equipment and spent fuel rods were being stored. The amount of radioactivity released by the escape of 250 gallons per day next to the James River was slightly higher than legally permitted.12

Fears of radioactivity shape public policy regarding waste disposal and transport, as well as production of electricity at nuclear power plants and even mining of uranium.

Communities downstream of the Coles Hill uranium deposit have been strongly opposed to developing that site. Virginia Beach gets some of its drinking water from the Roanoke River, and tourism is a major part of its economy. City officials were outspoken regarding concerns that structures containing mill tailings might be breached in a storm like 1969's Hurricane Camille, and radioactive particles could be flushed downstream into Lake Gaston. Though the amount of radiation reaching customers in Virginia Beach might be minimal, the possibility that tourists would react with fear and avoid trips to Virginia Beach alarmed city officials.13

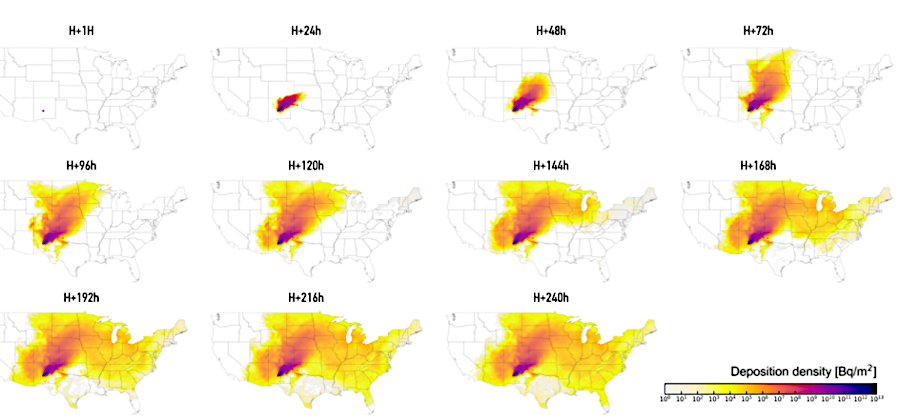

Radioactive fallout was deposited in Virginia from 101 atmospheric nuclear weapon tests conducted between 1945-1962. Fallout arrived a week after the very first test, when Trinity was detonated in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. Deposition varied due to weapons yield and weather conditions, but exceeded background levels of natural radiation. In Rochester, New York, photographic film was fogged by the fallout from the Trinity test.

As a result, Virginians are "downwinders." However, the levels of deposition do not make residents eligible for compensation under the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA).14

Fuel assemblies are taken out of reactors and replaced after five years. By 2025, the remaining 54 commercial nuclear plants with 94 reactors still in operation across the United States were adding 2,000 metric tons a year to storage.

Demand for electricity to power the expansion of data centers was expected to stimulate production of small modular reactors. More reactors would create more waste. However, until designs were finalized and facilities constructed, it was unclear if small modular reactors would generate more waste per megawatt of electricity generated compared to standard water-cooled reactors.15

within a week, radioactive fallout from the July 16, 1945 Trinity test was deposited in Virginia

Source: Fallout from U.S. atmospheric nuclear tests in New Mexico and Nevada (1945-1962)

radioactive waste in casks can be transported by truck or rail

Source: Department of Energy, Yucca Mountain

stored commercial spent nuclear fuel amounts (through 2019) and locations (as of June 2021)

Source: Government Accountability Office (GAO), Commercial Spent Nuclear Fuel: Congressional Action Needed to Break Impasse and Develop a Permanent Disposal Solution (Figure 1)

radioactive waste from generating electricity is stored at sites with active commercial reactors and at other "stranded" locations

Source: Congressional Research Service, Nuclear Waste Storage Sites in the United States (Figure 1)