a dead 30-foot humpback whale was found near the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel on February 2, 2017, and taken to Craney Island for disposal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 170203-A-BJ794-026

a dead 30-foot humpback whale was found near the Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel on February 2, 2017, and taken to Craney Island for disposal

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 170203-A-BJ794-026

There are 14 distinct populations of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the different oceans. Each year, whales in the West Indies population swim north from their wintering grounds north of the Dominican Republic to the Gulf of Maine, and even up to Newfoundland. They prefer warmer, calmer waters in the Caribbean to calve or breed, then migrate to cold, productive waters in the summer.

Most whales live and die without ever ending up on land as a disposal challenge. Sharks kill whales in the ocean, and also feed on carcasses of marine mammals who die from various causes. In 2018, fishermen observed two great white sharks feeding on a floating 50-foot long dead whale. That rare moment demonstrated how the bodies of most dead whales disappear from natural causes, without ever being seen by a human.1

great white shark feeding on a whale carcass off the coast of Virginia Beach

Source: The Virginian-Pilot, Hungry great white sharks feast on dead whale off Virginia Beach (photo provided by Capt. Jonathan Carter)

The whales that die far out in the ocean decompose and sink to the ocean floor. Whales that get stranded on beaches, or wash up on them, decompose on the shoreline. The strandings may be related to intense solar storms which disrupt the Earth's magnetic field, disorienting the whales as they navigate along the shoreline.

The mouth of the Chesapeake Bay is attractive because of the fish. In February, 2017, a pod of young male humpback whales paused near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay to feed on schools of menhaden there. At least one entered the bay, breaching off the Fort Monroe fishing pier in Hampton.

Whales become habituated to the ships going to Norfolk, Newport News, and Baltimore and do not recognize the danger. A whale in the shipping channel will not hear a massive container ship moving towards it. Whales on the sides, bottom and rear of the ship will recognize there is a vessel moving, but in front of the ship there is no noise or vibration until just before a collision.

North Atlantic right whales are protected under both the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. To minimize ship strikes, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has designated a North Atlantic Right Whale Management Area at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

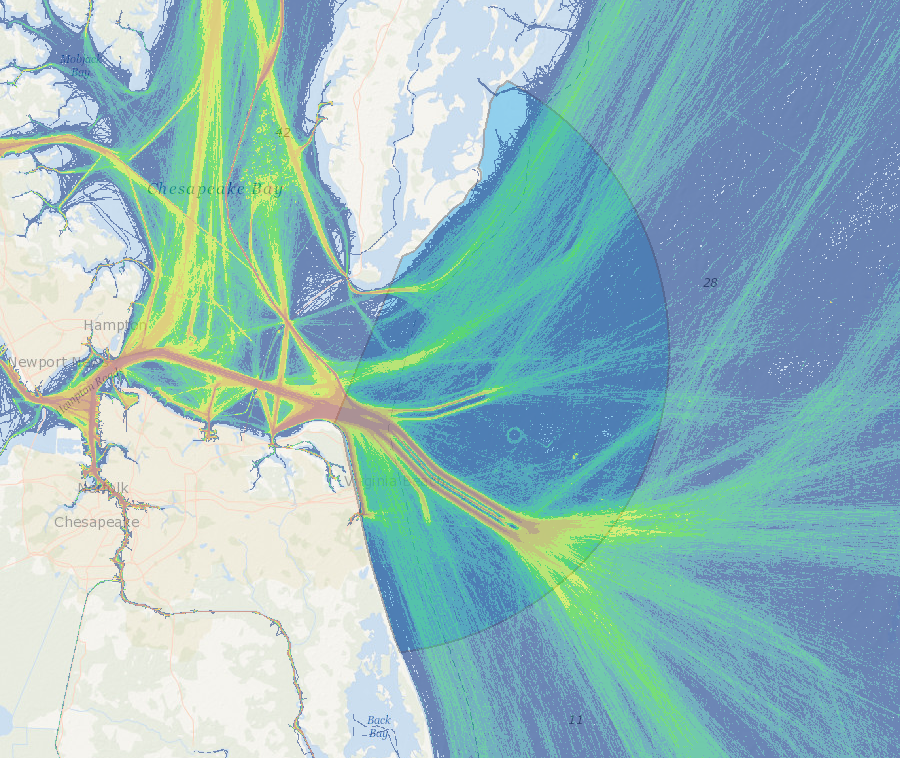

North Atlantic Right Whale Management Area at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay (darker blue) and ship traffic patterns

Source: Mid-Atlantic Ocean Data Portal

By 2022, there were less than 340 North Atlantic right whales left in the world. That year, a robotic buoy was installed in the Atlantic Ocean with acoustic recorders that could identify when a whale was nearby and alert shipping immediately. The alerts also facilitated designation of right whale "slow zones" that required ships to go no faster than 10 knots, thus reducing the risk of a whale strike.

robotic buoys that identify when North Atlantic right whales are nearby now facilitate designation of "slow zones" that minimize risk of a whale strike

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries, Help Endangered Whales: Slow Down in Slow Zones

Ships do not see whales before collisions, or do not have the ability to maneuver to avoid a strike. The narrow shipping channels at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay funnel fish, whales, and ships into the same space. Evidence of blunt force trauma and propeller wounds is commonly found during whale necropsies.

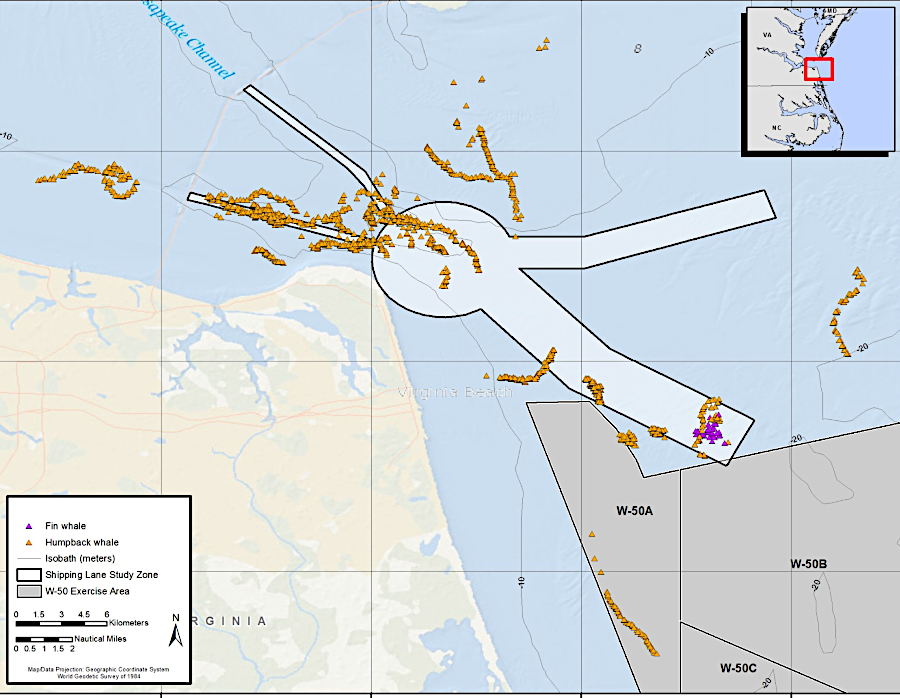

whales tracked between January 2015-May 2016 were often in the shipping channels

Source: US Navy, Mid-Atlantic Humpback Whale Monitoring, Virginia Beach, Virginia: 2015/16 Annual Progress Report (Figure 6)

In 2017, three humpback whales were killed in collisions with ships within a 10-day period. The first was hauled to Craney Island, where a necropsy there revealed evidence of a propeller strike. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has responsibility for managing marine mammals, and has authorized the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center to deal with stranded animals.

Scientists believed the other two also died after colliding with ships, though entanglement in fishing gear is also a cause of whale deaths. Whatever the cause of death, Federal regulations prohibit collecting souvenirs from the bodies.2

Dragging a dead whale to Craney Island or another spot where it can rot in peace is not a new idea. In 2009, a dead 25-foot long humpback whale weighing 10 tons was towed off the Gloucester County shoreline. It was taken to the other side of the York River near the Goodwin Islands, where the remains decomposed naturally. The carcass was:3

a dead humpback whale was dragged onto the Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area in 2017

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, IMG_9572_BJ794 and IMG_9582_BJ794

Dragging a dead whale to an isolated shoreline is feasible only if the carcass is fresh. A whale in an advanced stage of decomposition would fall apart while being towed. An old carcass has to be cut up and buried deep in the sand, using heavy equipment. Burial is also a suitable disposition process for small fin whales that wash ashore.

In 2018, a 30-foot long whale was found dead in the ocean just off Sandbridge. The body was towed to shore and examined; the necropsy determined that entanglement in fishing gear probably caused the whale to die. The following month, another whale stranded and died at Chincoteague. Both were buried, but a humpback that washed up on an Easter Shore barrier island near Oyster in 2019 was simply left in place to decompose naturally.

a dead humpback whale was left to decompose on a barrier island near Oyster in 2019

Source: R&C Seafood, April 23, 2019 Facebook post

Because the whales migrate past Virginia's coastline in January-February, burying a carcass deep in the sand will not affect recreational use of a beach later in the summer. Finding a carcass in the winter is not uncommon.

In January 2016, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared an "Unusual Mortality Event" situation for humpback whales along the Atlantic Ocean coastline. The high mortality appeared to reflect both an increasing population and an increasing number of ship-whale collisions. By May 2019, there had been 95 documented humpback fatalities along the coast, 19 of them in Virginia.4

In California, a carcass of a beached whale was cut up and hauled to a landfill in 2016. Those who butchered the carcass, to reduce it to chunks that could be loaded on trucks, had to get their scalpels and flensing knives sharpened throughout the day. The truck drivers who hauled the chunks to the landfill reported that the smell was as bad as chicken manure.5

The classic example of how not to remove a carcass was demonstrated by the Oregon State Highway Department in 1970. An eight-ton whale washed up on a beach, which in Oregon is considered a public highway. A KATU reporter described the plan for removal:6

The effort to remove the "stinking whale of a problem" went wrong, in a spectacular way. The engineers miscalculated how much dynamite was needed and how the carcass would explode. After the dynamite exploded, bits of rotten-smelling whale blubber and flesh flew up in the air and then dropped right back down again.

Whale parts covered the 75 spectators and reporters at the site. One large chunk fell over a quarter of a mile away, destroying a car. That evening, the highway department ended up burying in the sand one large portion of the whale that did not disintegrate.

Video of the "Oregon's Exploding Whale" has been viewed over three million times on YouTube. The light-hearted commentary from the KATU reporter at the time included:7

When a whale dies in the ocean, its carcass falls to the bottom. The organic material after a "whale fall" is equivalent to about 200 years of normal sediment deposit, and the carcass stimulates a sudden bloom of life. A University of Hawaii professor, Craig Smith, described the phases in which a whale carcass in the Pacific Ocean normally disappears:8

Oregon's attempt to dynamite a dead whale in 1970 "blasted blubber beyond all believable bounds"

Source: KATU, Oregon's infamous whale explosion occurred on this day 49 years ago

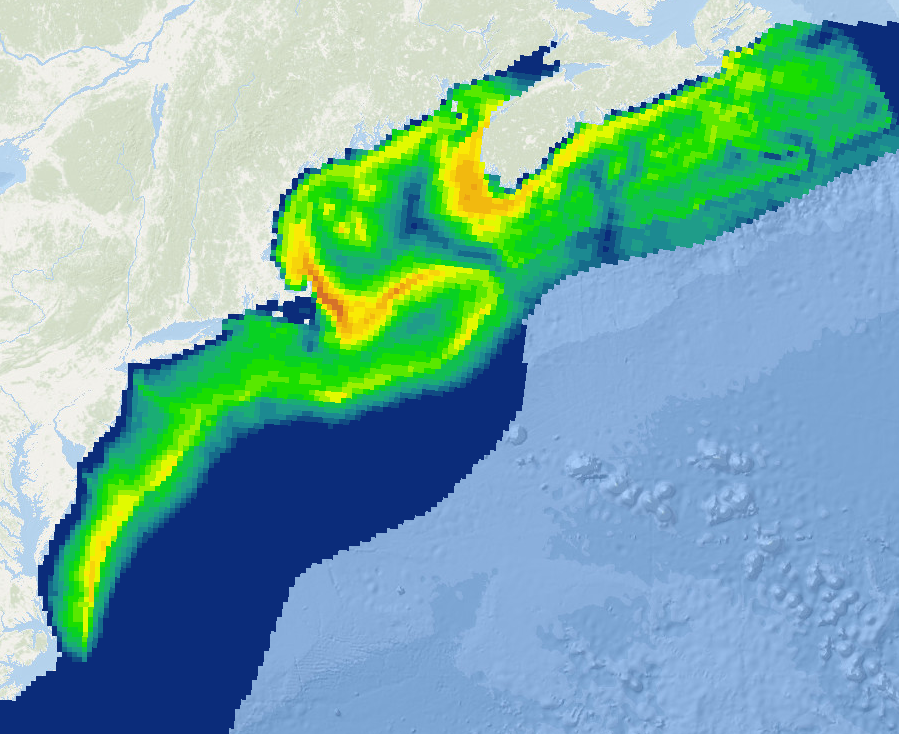

humpback whale density (animals/100 km2) in May show their migration past Virginia to the Gulf of Maine

Source: Mapping Tool for Cetacean Density for the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico

in 2014, the Virginia Aquarium conducted a necropsy on a 45-foot long sei whale that died in the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, 140822-A-OI229-008 and 140822-A-OI229-006