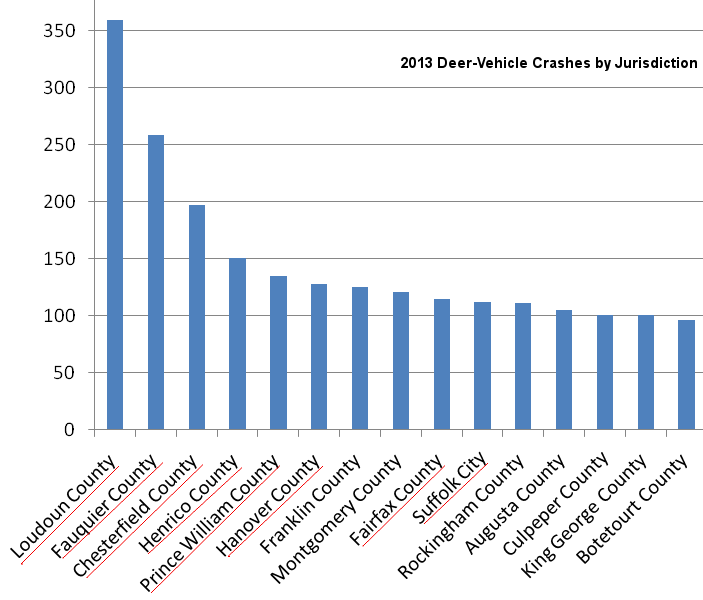

most deer-vehicle crashes occur in suburban areas of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads

Source: InsideNOVA, By the numbers: Deer-related crashes in Virginia (2014)

most deer-vehicle crashes occur in suburban areas of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads

Source: InsideNOVA, By the numbers: Deer-related crashes in Virginia (2014)

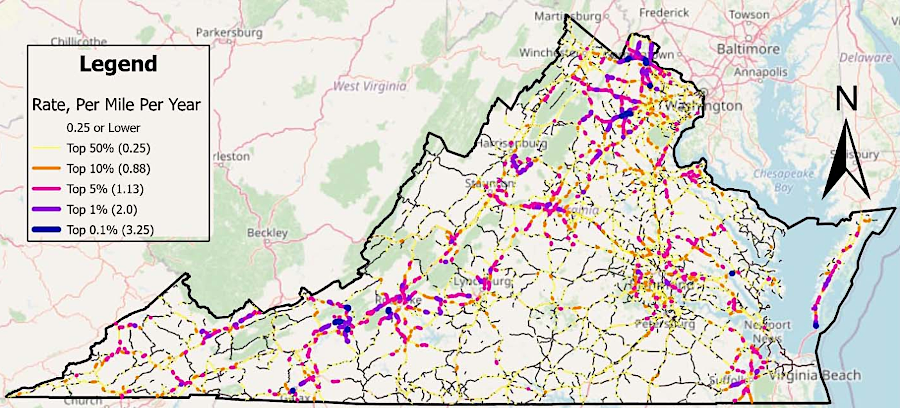

Vehicle accidents involving deer are common throughout Virginia, in urban as well as rural areas. The State Farm insurance company calculated that there were 61,000 animal-vehicle crashes in 2016, compared to less than 8,000 alcohol-related crashes. That number climbed to 81,694 animal-vehicle collisions in 2022.

Over 15% of all collisions in Virginia involved deer, and that number put Virginia in the top 10 of states with a deer-vehicle collision problem. Nationwide, the average cost of a deer-car collision was estimated in 2023 at approximately $20,000.

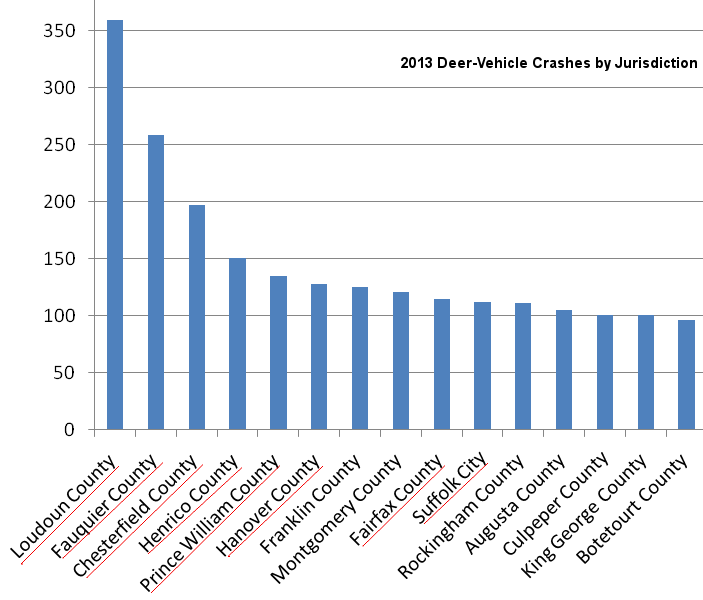

The crash reports under-represent the number of collisions. Deer carcass removal records indicated there were more than eight times more collisions than police reports. The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) responds to 20,000 calls for road-killed animals annually, primarily deer. Collisions with black bears also caused damage to vehicles.1

Virginia Department of Transportation maps in some districts where contract maintenance staff remove carcasses from interstates

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), VDOT Wildlife Carcass Removal Tracking PV

Multiple factors determine the number of deer-vehicle crashes in different Virginia jurisdictions, including the size of the county/city, the density of the deer population in each jurisdiction, and especially the number of drivers on the road. Eight of the top ten deer-vehicle crashes occur in suburban areas of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads.

Suburban counties have a combination of many deer and many drivers commuting to work at dawn and dusk, during the times when deer are most active. Fairfax County alone has 4,000-5,000 deer-vehicle collisions annually, with 55% occurring in October-December. Statewide, 50%-66% of vehicle-deer collisions occur during that rut season, when deer have other things on their mind besides avoiding traffic.

Deer seem not to learn to avoid cars and trucks on highways. Rather than flee, they freeze in the middle of the road as vehicles approach. "Deer in the headlights" can quickly become "deer in the grill of the car." It is also common to have deer run across the road, as they follow the alpha female, and smash into the side of a car going 55 miles per hour.

A deer management specialist for the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries has noted:2

Bucks wander individually in the Fall, looking for a doe who has gone into estrus and is ready to breed. The does travel in groups led by an alpha female, followed by her children and grandchildren. She decides if the group should cross a road, and the others follow. Experienced drivers know that if they see one deer on the road, then they need to look for others. A deer biologist explained how the decisionmaking authority of the alpha female exacerbates the risk of car-vehicle collisions:3

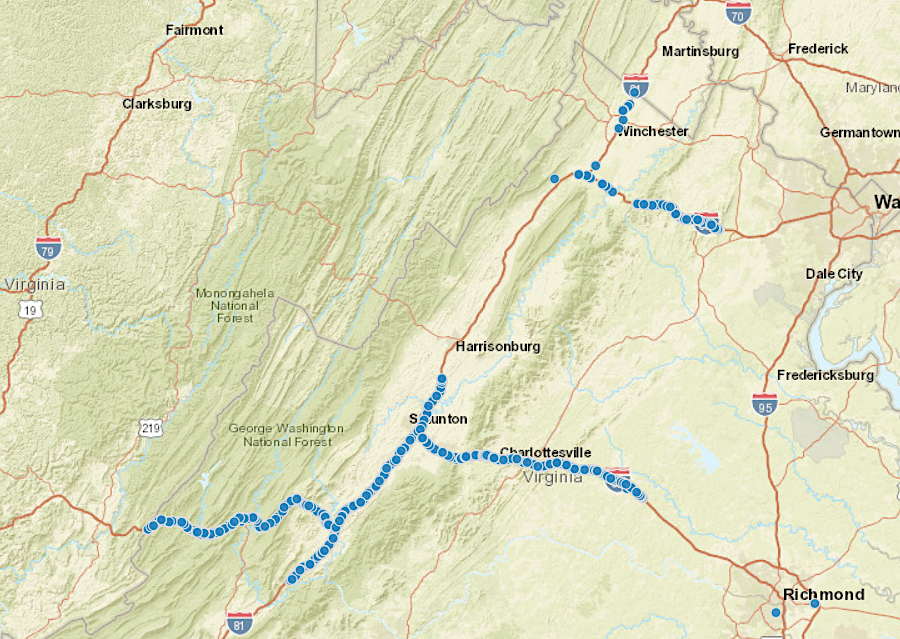

deer-related accidents in Prince William County occur in developed suburbs and even on I-95, not in just the rural areas

Source: TREDS (Traffic Records Electronic Data System) (2016 data)

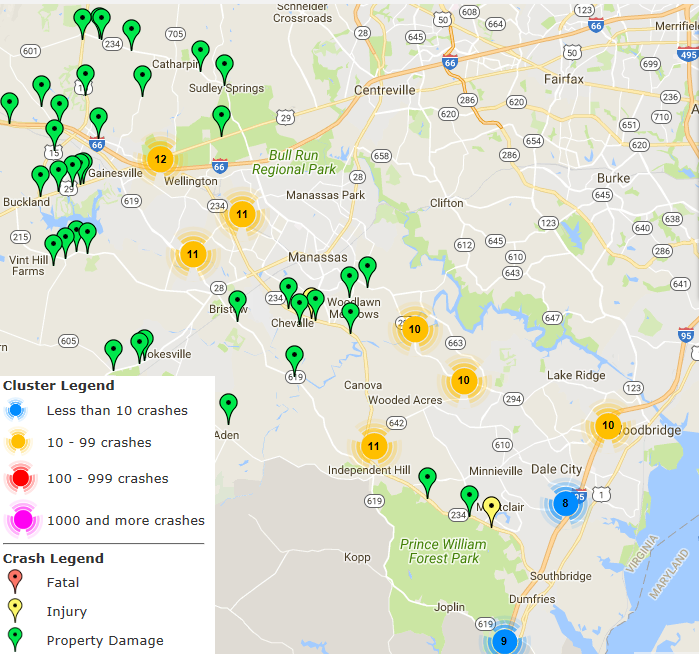

Bears are also at risk as they cross highways. The Virginia Safe Wildlife Corridors Collaborative is a group of researchers and advocates for reducing deer-vehicle and bear-vehicle collisions, established to create a multidisciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach. Reducing wildlife-vehicle collisions requires understanding animal and human behavior, evaluating a wide range of technological options, and finding solutions hat are consistent with the different management goals of multiple agencies.

multiple organizations are collaborating to identify how to reduce collisions between deer and cars

Source: Virginia Safe Wildlife Corridors Collaborative

One technical possibility is a buried cable animal detection system, powered by a solar panel. It can can trigger illumination of a "Deer Crossing" warning sign on the highway. That sign affects human drivers, not animal behavior. In a 2017-2018 test on Route 8 near Christiansburg:4

a deer detection system can trigger warning signs on a highway and get drivers to slow down

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, Implementation and Evaluation of a Buried Cable Roadside Animal Detection System and Deer Warning Sign (Figure 15)

Another way to reduce animal-vehicle collisions is to provide wildlife corridors which allow animals to cross large highways via underpasses and bridges. New highways can be designed with stream crossings wide enough for animal use, and on older highways some narrow crossings can be modified to encourage use.

In San Antonio, Texas, a bridge opened in 2020 to connect parkland divided by a six-lane highway and reduce car-animal collisions. At the time, the bridge was the as the largest wildlife crossing in the United States.

To minimize deer-vehicle collisions on Interstate 64, the Virginia Department of Transportation installed a mile of eight-foot high fencing near a box culvert just east of the Ivy exit and near the Mechums River bridge. Deer and even bear have been deterred by the fence until they reach the box culvert and river channel, which they use to safely to cross underneath I-64.

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Deer Fence

In 2019, an assessment found that the fencing had reduced deer collisions by 98%. There would be long-term benefits, because does were teaching their fawns to use the safe crossings:5

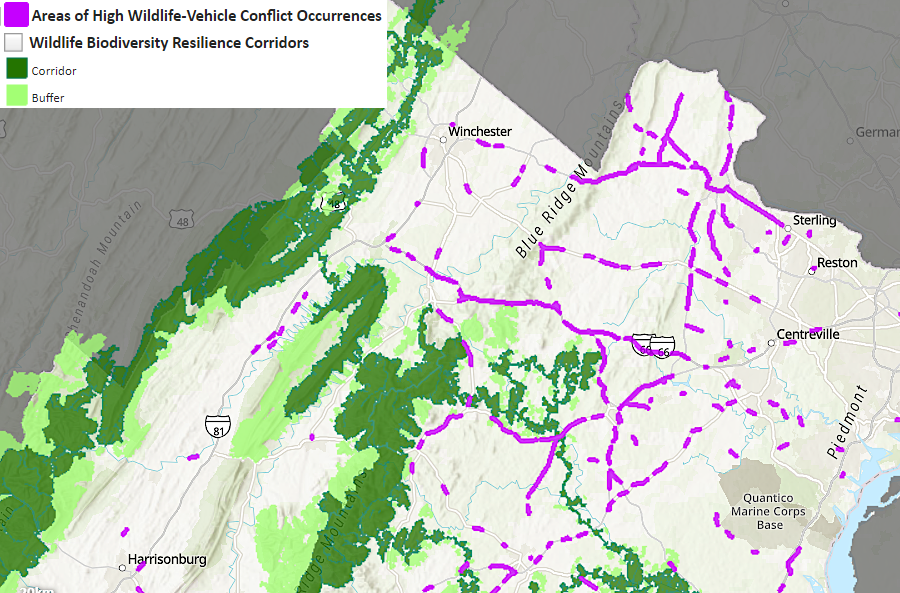

In 2020, after the wildlife overpasses near Charlottesville demonstrated success at reducing wildlife-car accidents, the General Assembly directed the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Department of Transportation, and the Department of Conservation and Recreation to prepare a Wildlife Corridor Action Plan. The three state agencies were given two years to identify areas with a high risk of wildlife-vehicle collisions and suggested techniques to create safe wildlife crossings in those areas, including fences and overpasses/underpasses.

In 2021, the General Assembly passed additional legislation requiring state agencies to incorporate recommendations from the Wildlife Corridor Action Plan into their management actions. In particular, the Commonwealth Transportation Board was directed to include planning for wildlife corridors in future updates of the Statewide Transportation Plan.

The 2023 Wildlife Corridor Action Plan, prepared by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Virginia Department of Transportation, and the Virginia Department of Forestry, estimated that deer-vehicle collisions cost Virginians over $500 million annually.

The General Assembly provided no additional funding when it directed completion of the plan in 2020. To implement any of the actions proposed in the plan, the four state agencies had to redirect existing funding or obtain Federal funding.

In 2023, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) received a $600,000 grant from the US Department of Transportation's new Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program. The Federal funding will allow the state agency to identify specific sites with the highest risk of vehicles colliding with deer, bear and elk.

Elk were a new risk, after successful reintroduction in Buchanan County in 2012-2014. Within six weeks after a portion of Corridor Q was completed in December 2023, four elk were hit and killed by vehicles on that highway. The Virginia Department of Transportation planned to install new driver warning and animal detection systems there, even though the 2024 General Assembly had failed to provide any funding to address wildlife-vehicle collisions in the high risk corridors identified in the 2020 Wildlife Corridor Action Plan.

One model was in the Netherlands. It recognized roads and railroads were fragmenting habitats and blocking natural migration patterns within the Netherlands Nature Network, and altering/creating crossings could reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions by 80%. in response, that country implemented a Multi-Year Defragmentation Program (MJPO) to reduce wildlife-vehicle conflicts:6

animal-vehicle collisions (purple) were common in the Northern Virginia suburbs whre Wildlife Biodiversity Resilience Corridors (green) were not identified

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), Virginia's Wildlife Corridor Action Plan

After an accident, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) removes animal carcasses from the roadway to eliminate the traffic hazard. Carcasses have been buried if there was a suitable location in a nearby VDOT right-of-way and equipment for digging a hole was available.

Dead deer are not just dragged off of the pavement to the nearest ditch; that would attract vultures and other animals and potentially cause more animal-vehicle collisions. In many areas the deer remains have been hauled away to landfills, but decaying carcasses ultimately create gases and pockets in which garbage can slump down and crack landfill caps. By 2011, landfill disposal was costing VDOT $4 million a year in transportation and landfill fees.

Deer hit by a car (roadkill) or hunted illegally (poached, and butchered for the meat)

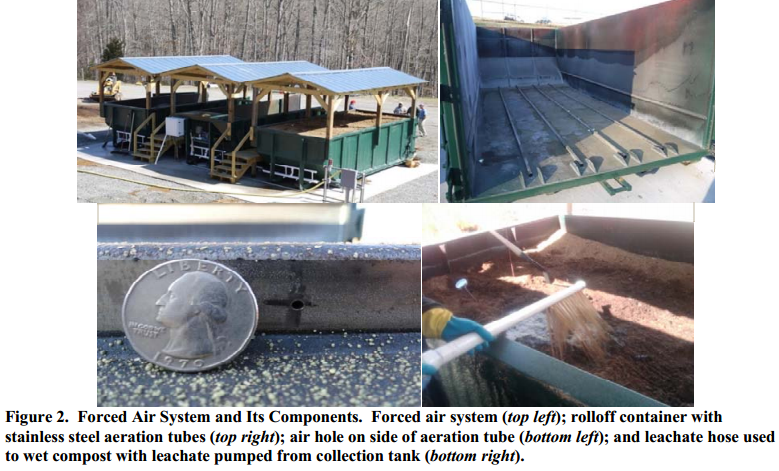

To reduce those costs, VDOT started to mimic a practice used on large farms and began composting animal carcasses. In one research test, dead deer were mixed in with woodchips and placed in static compost windrows ("passively aerated stationary piles") aligned on the ground surface. High temperatures within the piles of decomposing wood chips killed pathogens and roundworms in the carcasses within three months. In contrast to burying deer in the right-of-way, composting minimized the potential of bacteria reaching nearby streams and degrading local water quality. However, the windrows used up substantial space at VDOT's equipment centers.

To solve the problem in less space, the state transportation agency also experimented with a rotating drum composting system filled with sawdust and carcasses. A third technique was to place wood chips and carcasses in a rectangular metal bin, with a forced-air system. The fans recycled leachate droplets created as layers of carcasses rotted, and controlled odors by blowing the vapor back into the bin.

The rotating drum system had equipment problems and had difficulty maintaining desired the temperature and moisture, so VDOT decided to build forced air composting systems at multiple locations across the state. Those composting facilities cost $140,000 each, but costs were offset within five years by the reduced expenses for transporting and disposing of deer carcasses at landfills.7

VDOT has adopted a combination of the windrow and metal bin procedures. At a VDOT facility in Lynchburg, concrete bins 10 feet wide and 18 feet deep are loaded with carcasses of deer, dogs, and other large animals removed from the roads. Each carcass is covered with sawdust until the bin is full. Plastic pipes at the bottom of the pin force air though the piles.

It might take a month to fill a bin, and then another month for decomposition to be completed. Inside the compost pile, temperatures reach 140 degrees. There is no smell so long as the balance of carcasses and woodchips is correct. At the end of the process, the sawdust is dark, with still-intact bones and antlers.8

In Virginia, cities rather than VDOT maintain most highways. The cities of Suffolk, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach chose to use diesel-fueled incinerators, rather than compost deer killed in collisions with vehicles. The incinerators eliminated problems with any odor and leachate from decay. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality had to issue air quality permits for new incinerators burning diesel oil, but Suffolk failed to get its emissions permit in time. In 2015, the General Assembly had to pass a special bill to give Suffolk additional time to meet state air quality standards.9

VDOT selected a forced air composting system for disposal of deer carcasses

Source: Virginia Center for Transportation Innovation and Research, Composting Animal Mortality Removed From Roads: A Pilot Study of Rotary Drum and Forced Aeration Compost Vessels

Disposal of other animal carcasses besides deer can also be challenging. The Valley Proteins rendering plant in Frederick County stopped processing euthanized animals in 2019. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) notified Valley Proteins that it had found pentobarbital as a contaminant in final animal fat products from the Winchester plant, and the drug was an unapproved adulterant.

The company concluded that the pentobarbital had entered the food chain when a few euthanized horses had been processed. The decision to stop processing the carcasses of euthanized horses, cattle, and other animals forced local farmers to find another disposal option, such as to burying that "dead stock" on their farms.10

Valley Proteins highlights the benefits of rendering animal carcasses (but stopped processing euthanized animals in 2019)

Source: Valley Proteins, Rendering Is Recycling

VSWCC Intro

Source: Wild Things Media