when you flush, where will it go?

when you flush, where will it go?

There was little need for any sewage treatment facility before Virginians clustered into densely-populated cities, starting in the 1700's. For perhaps 20,000 years, the Native Americans did not have outhouses or toilets; they used the woods. Few people concentrated at any one location for very long; even long-term town locations shifted slightly each few years, as the Native American structures were moved/replaced.

What may be the oldest sewers discovered so far were built in Babylon about 4,000 BCE (Before Common Era). In some of the first town settlements, ditches and clay pipes carried excreta from houses to central cesspits.

The Neolithic residents at Skara Brae and the Barnhouse Settlement in the Orkney Islands created what may be a drainage system to remove human waste around 3,500 BCE. A stream was re-routed to flow beneath the latrines within houses, which were built into mounds of pre-existing rubbish and connected by tunnels.

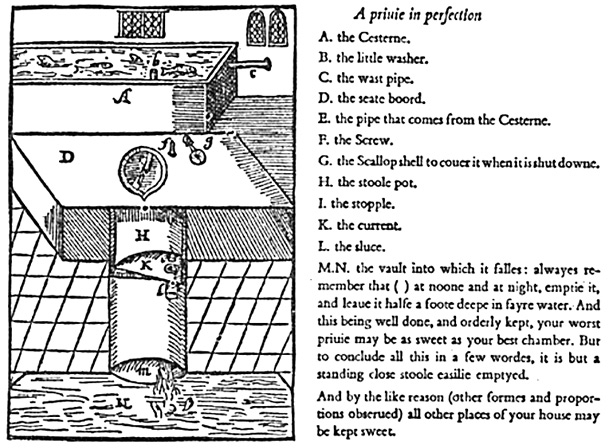

The flush toilet was invented in 1596 by Sir John Harington. His design collected waste in a pipe which had a brass gate. Twice a day, the gate was to be opened and the cylinder holding the waste flushed with water. Effective control of odors did not become common until Alexander Cumming developed the "S" curve in the pipe connecting the toilet bowl to the cesspool/sewer. That 1775 invention was popularized by Thomas Crapper, whose toilets dominated the English market in the late 1800's.1

the first flush toilet, developed in 1596, lacked the "S" curve in the pipe to minimize odors

Source: Sir John Harington, A New Discourse of a Stale Subject, called the Metamorphosis of Ajax (1596)

In 1607, the first colonists at Jamestown discovered the impact of poor sanitation. When the Native Americans were hostile, travel outside the walls of the fort to go to the bathroom could be hazardous. When the English did go to the bathroom in the woods, they may have stocked the local swamps with dysentery and typhoid microorganisms. Between the departure of Captain Christopher Newport on June 22, 1607 and his return with the First Supply at the end of December, almost 2/3 of the colonists died.

As a gentry developed in the mid-1600's, some wealthy Virginians built large houses. There, they would use chamber pots to "do their business" indoors, and the contents would be thrown into the back yard. Later, as towns developed, waste was tossed into the streets to decompose or be washed away in the rainstorms. Privies or outhouses were also built in back yards, and were common in early Williamsburg and other cities.

Though Virginia celebrates its history almost to excess, the evolution of wastewater management is rarely acknowledged. A few mansion houses, such as Mount Vernon or Monticello, have restored the "necessaries" or outhouses away from the main house. Historic house tours across Virginia exhibit old chamber pots as pristinely clean artifacts, providing little context for their normal use. Recreated historic sites, such as Williamsburg and Civil War battlefields, rarely include the volume of horse manure, flies, and odors that would provide a truly authentic experience.

Colonial Williamsburg recreates fancy bedchambers in places such as the Wythe House - and includes chamber pots

Armies during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War could create concentrations of waste. The soldiers dispersed into the woods while moving between places, and dug trenches for privies when in camps.

On the march, regiments often avoided using the exact same campsite as units who had walked that route in front of them just a day earlier. The first unit picked the obviously-best location for water, forage, firewood, etc. Regiments who arrived on the second day could smell what the earlier soldiers had left behind; it was often better to move several hundred yards away to a less-ideal location in order to find a cleaner campsite.

Prior to the automobile, the most obvious waste problem in urban areas was horse manure on city streets. When vehicles using internal combustion engines replaced horses a century ago, the new technology quickly reduced solid waste pollution on urban streets while gradually increasing air pollution.

Waste management remained decentralized for several centuries. Once towns built the infrastructure to supply fresh water for firefighting and domestic use, however, the flush toilet became an option. At that point, the population concentrated in a town needed a sewer system to carry human waste from flush toilets to a nearby river.

The first sewer systems in Virginia were just for transport; no wastewater treatment facilities were built. Pipes carried raw sewage to the riverbanks, and the rivers were used as open sewers to carry the waste away.

Water in the rivers diluted the human waste transported by sewer pipes, as well as the animal manure that washed over the roads and fields. After exposure to sunlight, oxygen, and bacteria, waste would decompose and be dispersed within the river. At some distance downstream, water in a river was clean enough to drink again.

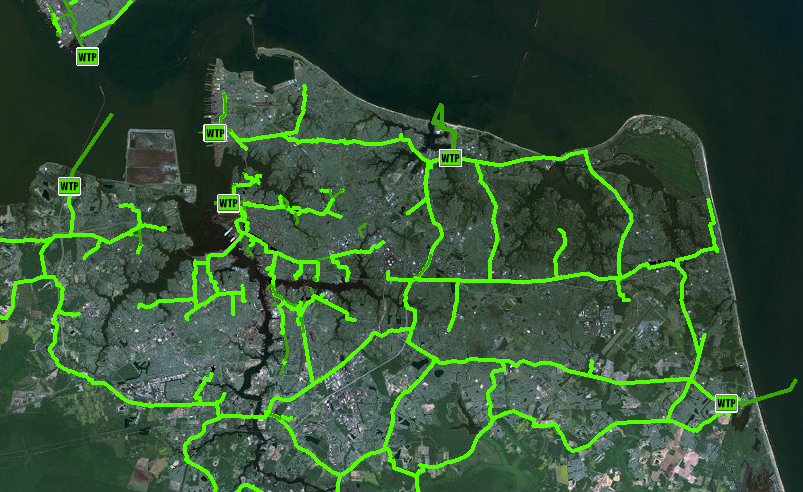

green lines show large sewer interceptor pipes in Hampton Roads, leading to wastewater treatment plants (WTP)

Source: Hampton Roads Sanitation District, Public GIS Viewer

Most wastewater treatment facilities in Virginia were built after World War Two. For example, Alexandria put its wastewater treatment plant into operation in 1956. Prior to that, raw sewage was discharged to Four Mile Run.2

Today, we take the sanitary wastewater system for granted. If you live in the country, your waste probably goes into a septic tank near the house. There are an estimated 1.1 million septic systems in Virginia, in which there are 3.5 million housing units.3

If you live in the city, it probably goes into a sewer pipe. Almost everyone uses a ceramic toilet 5-10 times a day, and the waste goes quickly out of sight and out of mind. Only a few primitive campers hiking the Appalachian Trail or seeking a wilderness experience still use the woods, and have to think about where to go. (Today, when you flush, do you know where it goes? Does everything you flush just... disappear?)

Since 1992, new toilets have been "low flow," using no more than 1.6 gallons per flush. Earlier toilets used 3-7 gallons per flush, so reducing the water in each flush has reduced the volume of water that is transported to wastewater treatment plants. What does get to the treatment plant is slightly more concentrated, but the low flow toilets minimize the construction costs to process the volume of waste.

Sanitary engineers in urban areas have created an underground artificial river system, hidden from view, to connect houses/businesses to wastewater treatment plants. Sewer pipe have been engineered and installed so a slow flow gradually washes everything downhill by gravity. Most fluid in the sewer pipes comes from washing machines, showers, and kitchen sinks.

Sewer pipes are typically filled mostly with air. The massive number of bathroom breaks at halftime of the Super Bowl might create a short-term increase in flow, however. Unless there is a blockage, flow occurs 24 hours/day, 7 days a week.

the H. L. Mooney Advanced Water Reclamation Facility on Neabsco Creek processes sewage from eastern Prince William County, except Dale City

Source: Historic Prince William, Neabsco Boardwalk, part of Rippon Lodge Park - #132

Wastewater from industrial facilities may be treated onsite at those facilities and then discharged under a Virginia Pollution Discharge Elimination System permit, or pre-treated onsite and then transported by the local sewer system to a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Pre-treatment is required to reduce the specific chemicals or other pollutants used at the industrial facility that are not normally in municipal sewage, to ensure the wastewater is average in quality and the standard treatment process can handle whatever the industrial site delivers.

In a rare incident, Fairfax County sued the Krispy Kreme bakery in Lorton because that facility was discharging too much "doughnut grease and slime" from cooking 83 million doughnuts a year. The company settled the lawsuit in 2009, then closed the bakery and moved operations to Baltimore several months later.4

In contrast, the City of Hopewell chose to subsidize treatment of nitrogen-rich waste produced by Honeywell and other industrial plants. The city spent 20 years studying how to reduce nitrogen discharged from the regional wastewater treatment plant, before constructing a $76 million nutrient removal system. Though 85% of the wastewater came from industrial facilities, those facilities paid just 1/3 of the total cost. State grants and city taxpayers funded the remainder.5

To ensure smooth flow, fast food restaurants such as McDonalds are not allowed to empty their fryers directly down the drain. Instead, waste fats, oils, and grease are collected in special containers and hauled away by a contractor, such as Valley Proteins based in Winchester, Virginia. The cooking oil waste is recycled to produce biodiesel and animal feed. The hamburger customers eat tomorrow may come from a cow that was fed old French fry cooking oil last month.

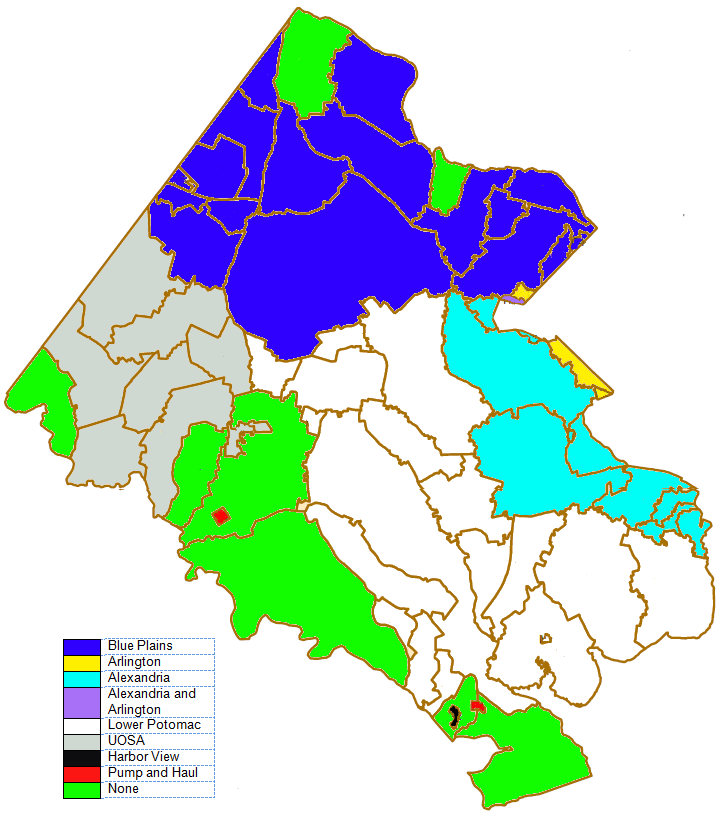

wastewater treatment is regional;"sewersheds" in Fairfax County are serviced by different wastewater treatment plants (except for selected areas shown in green, which rely upon septic systems)

Source: Fairfax County, Demographic Reports (2011)

Though gravity is the primary mechanism to move solid waste from the houses/businesses through the sewers to a sewage treatment plant, pumping stations may be constructed along the way to ensure a steady flow. Engineers often take advantage of natural contours and lay pipes parallel to streams. Recreationists who hike/bike on paved trails in the stream valleys of Arlington, Fairfax, Richmond, Roanoke, and other areas may not recognize that a sewer line is underneath them, unless they notice the number of manholes along the trail. Manholes provide ventilation for the pipes, plus access for maintenance.

sanitary sewer pipes at George Mason University - Fairfax campus

Source: Fairfax County Map Viewer

Typically, the greatest need for sewer pipe maintenance is to remove blockages caused by tree roots. Trees gradually push their roots through the junctions of the pipes, seeking water and nutrients. A mass of tree roots can be sliced away by modern robotic technology, where maintenance personnel insert self-propelled machines into the pipe with TV cameras for spotting obstructions and sharp blades for removing them.

Sewer pipes built in the 1950's and 1960's, as Virginia suburbs grew during the baby boom, were designed to last 50 years. As soil settles and tree roots push against the pipe junctions, cracks can form in sewer lines. Because sewer lines are often located below the local water table, leaks often involve groundwater infiltrating into the system rather than sewer waste leaking outside the pipes.

In storm events, excessive amounts of infiltration can dramatically increase the volume of water reaching the treatment plant. Since sewage treatment facilities are located at low spots in local topography and often adjacent to rivers, flooding is also a serious threat.

the Roanoke wastewater treatment plant is protected by 0.4 mile of earthen dike and 0.2 mile of floodwall

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, National Levee Database

A similar problem to infiltration is inflow, when stormwater is introduced into the supposedly-separate sanitary sewer system. If sump pumps in basements, gutter downspouts, and other stormwater pipes are hooked up to wastewater pipes, "nor'easter" storms and hurricanes can pour too much rainwater into the sewer pipes.

The City of Manassas estimated that 15% of the sewage it sent to the Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) wastewater treatment plant was inflow. Because the city was already using 95% of its share of the treatment capacity, it faced an expensive burden to purchase more capacity from another jurisdiction. That made it cost-effective to implement an aggressive inflow and infiltration sanitary sewer line rehabilitation program. sealing the pipes to block infiltration and identifying sites where stormwater inflow could be blocked.6

Inflow and Infiltration (I&I) are problems because, once all storage ponds and tanks are filled, sewage treatment plants receiving too much flow through the intake pipes will be forced to dump partially-processed or untreated sewage directly into streams. Such dumping may be in violation of the Virginia Pollution Discharge Elimination System (VPDES) permit issued by the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) for the facility... but there is no other option.

One way to keep sewer pipes sealed and intact is to reline them. High tech machines move through the pipes and spray sealant, or install liners that create a new fiberglass tube inside the old pipe. Relining sewer pipes reduces their diameter slightly, but is a cost-effective way of extending the useful life of the infrastructure. Relining can reduce infiltration, but inflow can be corrected only when inappropriate connections are re-plumbed so stormwater does not flow into the wastewater pipes.

Front Royal faced a choice in 2018, when its wastewater treatment plant experienced substantially higher rates on input than the facility could process. The town signed a consent order in 2012 with the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality to study infiltration into the sewer pipes. Front Royal upgraded its sewage treatment, but reduced costs by postponing an expensive "Phase II" to expand capacity.

If daily flow exceeds the plants 5.3 million gallon capacity for three consecutive months, the town will be forced to start planning for expansion. It's only alternative is to replace clay pipes installed in the 1940's and 1950's that allow water into the sewer system. Digging up the streets disrupts local businesses and traffic. Replacing pipes is also expensive, but may be more cost-effective in the long run than allowing infiltration to continue.7

the Front Royal wastewater treatment plant is authorized to discharge 5.3 million gallons daily into Happy Creek

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In Richmond's West End neighborhoods, separate sewer lines were installed in many small watersheds and slanted downhill at a gentle slope until reaching the James River. There, the small sewer lines now connect to a large "interceptor" sewer pipe. Waste flows down the interceptor to the wastewater treatment plant on the south side of the James River in Manchester.

If the interceptor is unable to follow the contours directly, then pump stations will lift the waste up across a watershed divide. Small pump stations and short sections of pressurized sewer pipe (to overcome gravity) are a common but often-ignored item in many stream valleys in urban and suburban areas of Virginia.

At the end of the sewer line is Richmond's wastewater treatment plant. The waste goes through a multiple-stage process there - solids settle out, organic material is decomposed, and bacteria/viruses that were originally deposited into toilets (such as E. coli) are killed. In the Chesapeake Bay watershed, nitrogen/phosphorous is reduced through additional processing known as Biological Nutrient Removal (BNR) or Enhanced Nutrient Removal (ENR).

Noman Cole Wastewater Treatment Plant at Lorton in Fairfax County (click on images for larger photos)

Wastewater treatment plants are designed to process liquids, and not to treat solid waste. At the entrance to a wastewater treatment plant, a grate will intercept any cigarette filters, popsicle sticks, coins, and other solid objects that were flushed down toilets and traveled through the pipes.

The items caught on the grate are deposited in a bin and hauled to the solid waste landfill. Occasionally a plant worker will see currency drop from the screen into the bin, and debate whether it is worth the effort to retrieve the money.

solid objects that flowed through the sewer pipes are screened out at the head gate before wastewater is treated

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Richmond Wastewater Treatment Plant in Richmond, Virginia

In the primary stage of treatment, wastewater that passes through the grate enters a tank. There, the speed of flow is slowed down. Solids settle to the bottom, while lighter grease rises to the top. The scum at the top and the solids on the bottom of the tank are scraped off mechanically, and the partially-processed water then flows to secondary treatment.

the Fauquier County Sewer Plant at Remington treats sewage before discharge into the Rappahannock River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

During secondary treatment, bacteria eat the organic materials in the wastewater and reduce the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD). Before wastewater treatment plants were built, sewage dumped directly into streams could "suck up" all the oxygen in the water as the waste degraded, creating dead zones in Virginia's rivers.

Bacteria also strip the nitrogen out of the water during secondary treatment, in a two-stage process, both anaerobic (without oxygen) and aerobic (oxygen-loving) bacteria convert the nitrogen in the wastewater into nitrites (NO2), nitrates (NO3), and ultimately nitrogen gas (N2) molecules.

Through a carefully managed flow of water, in tanks with baffles and air jets ("biological reactors"), ammonia (NH3) and ammonium molecules (NH4) in wastewater are nitrified (converted to NO3) by aerobic bacteria. In a second stage, the nitrates are then denitrified (converted to N2 molecules) by anaerobic bacteria.

This biological nutrient removal process was developed at the Virginia Initiative Plant in Hampton Roads.8

in the secondary treatment tanks, aerobic and anaerobic bacteria digest the solids dissolved in wastewater

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Richmond Wastewater Treatment Plant in Richmond, Virginia

Biological reactors are designed to use gravity as much as possible to move the wastewater between aerobic, anoxic (no oxygen), and anaerobic zones. In each zone, different bacteria consume organic carbon and convert the nitrogen in stages, until the nitrogen ends up as N2 molecules and escapes as a gas into the atmosphere. N2 already composes 78% of the atmosphere, so wastewater treatment plants are not creating air pollution when they emit nitrogen gas.

The nitrogen gas escapes into the air, and the living bacteria form a layer of activated sludge on the bottom of the tank. Water, air, and sludge are mixed carefully in the secondary treatment process to maximize the effect of treatment. Some activated sludge is pumped back to the front of the tank while most is removed from the bottom. The sludge removed during the secondary treatment process is added to the solids/scum removed during primary treatment, for final disposal. Solids may be incinerated, placed in a landfill, or recycled as biosolids spread on farm fields and in forests.

wastewater is treated by Upper Occoquan Service Authority and released into Bull Run, then recycled downstream into drinking water by Fairfax Water

Source: Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA), Drone Flyover of UOSA

At the end of secondary treatment, there may be a third step - tertiary treatment, commonly required in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Tertiary treatment may include the introduction of chemicals to remove phosphorous, or use of membranes. Both phosphorous and nitrogen are nutrients that stimulate excessive algae growth and lead to eutrophication of the bay.

Tertiary treatment can create an additional layer of sludge. That sludge must be handled, along with the solids extracted from wastewater during primary and secondary treatment. In 2010, the Nansemond Treatment Plant in Suffolk, part of the Hampton Roads Sanitation District, implemented a nutrient recovery technology to convert sludge into commercial fertilizer.9

Once stripped of nutrients, wastewater goes through a final polishing process. Chlorine is added to kill bacteria/viruses, and then the water is dechlorinated - otherwise, the treated wastewater dumped into a stream would kill the fish. A final step involves trickling the water through a sand or charcoal filter to remove any remaining particles before sending the treated water through a ditch or pipe ("outfall") and into a stream ("receiving water").

fully-treated wastewater is returned to the stream at an outfall

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Richmond Wastewater Treatment Plant in Richmond, Virginia

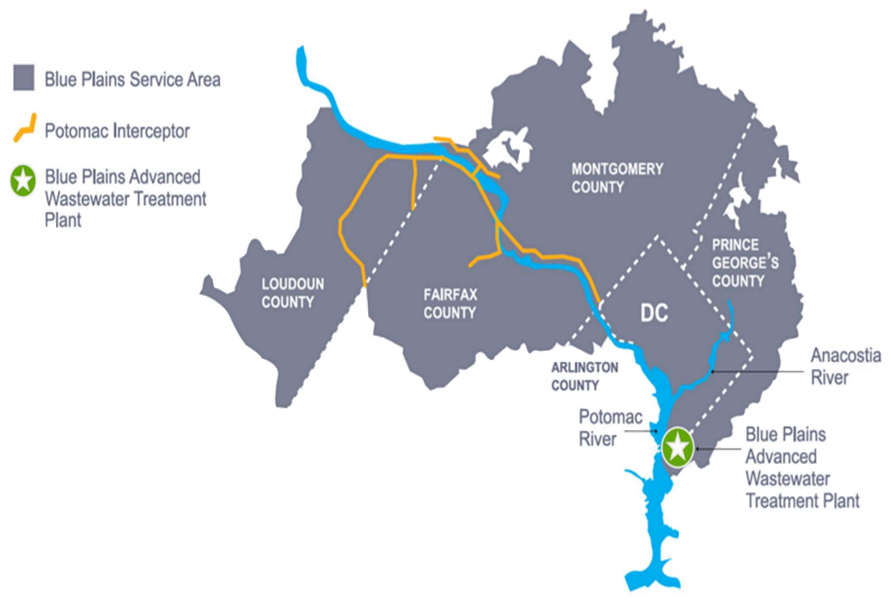

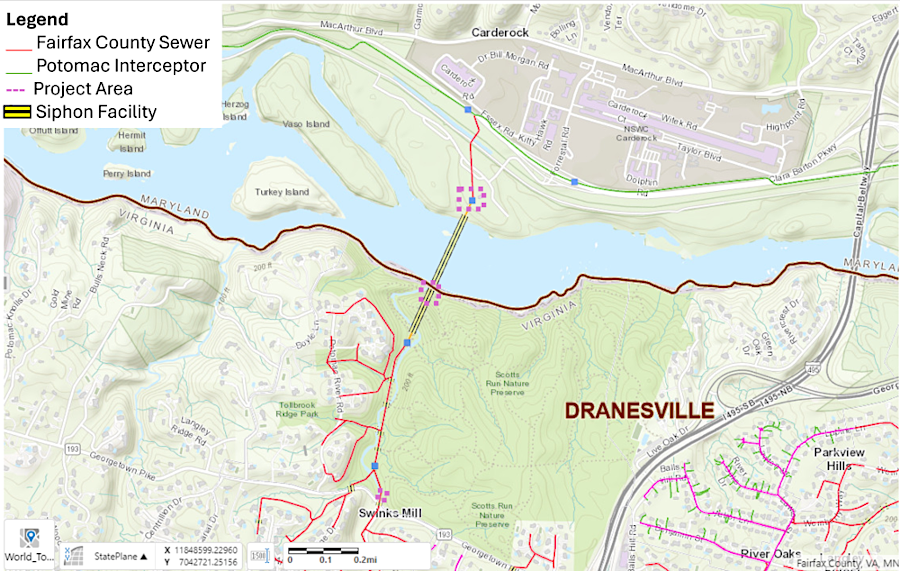

The wastewater generated at Dulles International Airport is carried underneath the Potomac River at the Scotts Run Nature Preserve. It then flows through the 54-mile long set of Potomac Interceptor pipes downstream to Blue Plains, where treated effluent is released into the river downstream of any water intake.

There are two Potomac Interceptor pipes drilled into the bedrock underneath the Potomac River. The upstream pipe at Great Falls is 78" in diameter and carries 60 million gallons/day of wastewater from Maryland to the pine in Virginia. In 2025 DC Water conducted a drilling operation into the bedrock there as it planned a replacement pipe. Helicopters transported a drill rig and workers into the middle of the river, so the drill could obtain samples of the rock and plan to install a new underground pipe.

the Potomac Interceptor includes pipes crossing underneath the Potomac River at two locations

Source: DC Water, Potomac Interceptor Project

At the downstream crossing, three pipes carry wastewater beneath the Potomac River to the northern shore of the river in Maryland. In 2024 Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services discovered that two of the pipes were completely blocked by silt; emergency work was needed. If the third pipe became clogged, the Potomac Interceptor would have dumped raw sewage into the Potomac River.10

three pipes carry wastewater from Fairfax County underneath the Potmac River to the Potomac Interceptor and then Blue Plains

Source: Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services, Scott's Run Siphon Emergency

Downstream of Little Falls on the Potomac River, no community uses the Potomac River for drinking water. In contrast, treated wastewater for every community above the Fall Line will reach an intake pipe for another community's drinking water system.

The wastewater of Waynesboro and Staunton flows to the main stem of the Shenandoah River, from which Winchester extracts water for its use. Land use planning professionals all know the phrase "everyone lives downstream."

In one case, living downstream from a wastewater treatment plant increases water quality. Wastewater from the Upper Occoquan Service Authority (UOSA) plant near Centreville is released into Bull Run. That treated wastewater flows to the Occoquan Reservoir, and is pumped out of the reservoir into the Griffith Water Treatment Plant operated by the Fairfax County Water Authority. The effluent leaving the UOSA plant is cleaner than the water that naturally flows in Bull Run.

The Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility in Loudoun County must comply with the Dulles Watershed policy, because the discharged waste will enter the Potomac River just upstream of drinking water intake pipes for Fairfax and the District of Columbia. In 1975, the State Water Control Board had established a 15-mile minimum distance between wastewater treatment plant outfalls and existing drinking water intake pipes in the Dulles area, but then modified the distance later. Reducing the distance to 10 miles allowed Leesburg to build a sewage plant that discharged into the Potomac River, and for Loudoun County to build a wastewater treatment plant on Broad Run.11

Water conservation, including low flow toilets requiring just 1.6 gallons per flush, has reduced total flow to wastewater treatment plants. Jurisdictions that invested in lining sewer pipes to reduce inflow and infiltration (I&I) have blocked groundwater from entering the pipes, reducing the need to expand water treatment plants. Lynchburg, Richmond, and Alexandria have revised their Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) systems, separating stormwater and sanitary sewer systems. Blocking stormwater from entering the sewer pipes by various means has reduced the total flow getting to the end of sewer lines.

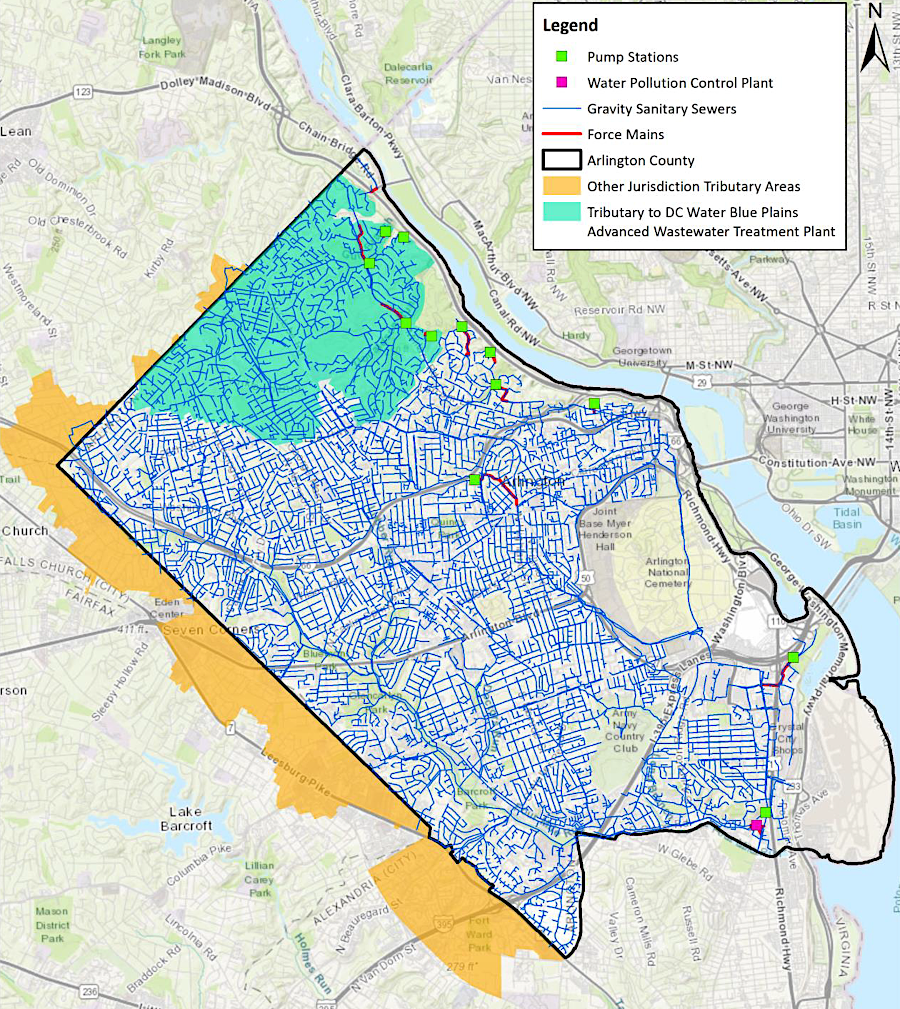

Arlington County updated its 2002 Sanitary Sewer Collection System Plan in 2024. In the previous two decades, population had grown nearly 25%. At the same time, water conservation by residents had reduced use to a level consistent with the 1960's:12

Because less wastewater was flowing to the sewage treatment plant per person, the county projected that continued population growth to 2045 would not require expanding the 459 miles of pipes or other wastewater infrastructure. The county planned to continue lining pipes to minimize groundwater infiltration (GWI):13

wastewater plants operate with a steady volume by using equalization basins to store higher daytime flows and supplement low nightime flows

Source: Prince William Water, H.L. Mooney Advanced Water

Reclamation Facility (AWRF) Construction Update (June 12, 2025)

Enhanced Nutrient Removal (ENR) tank at Noman Cole facility, showing baffles to create anaerobic/anoxic zones during secondary treatment

Source: Environmental Protection Agency 910-R-07-002, Advanced Wastewater Treatment to Achieve Low Concentration of Phosphorus

membrane used at Broad Run Water Reclamation Facility (click on images for larger photos)

H. L. Mooney Advanced Water Reclamation Facility and its water quality testing lab in Prince William County

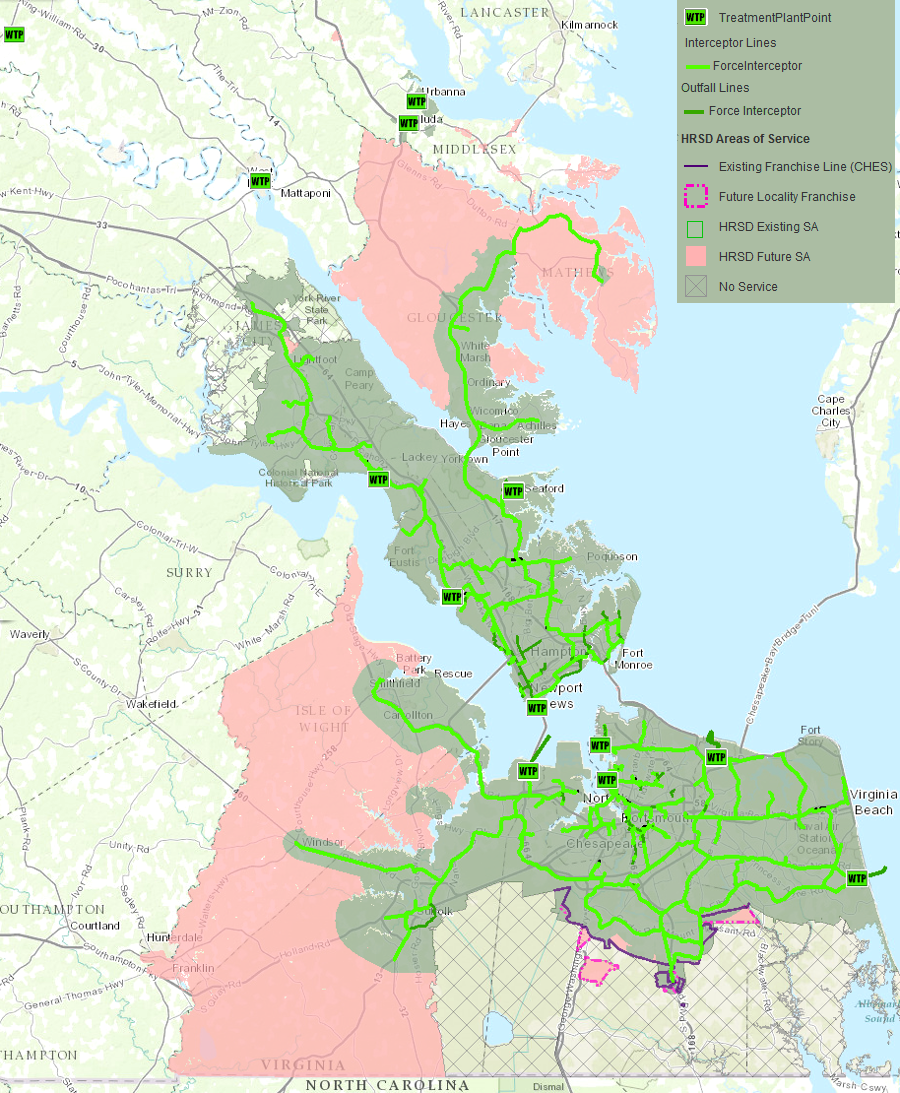

the Hampton Roads Sanitation District plans to expand west beyond the Blackwater River (to service the City of Franklin) and north to the Rappahannock River

Source: HRSD GIS Public Viewer

the wastewater collection system in Arlington County

Source: Arlington County, Update to the Sanitary Sewer Collection System Plan, an Element of Arlington County's Comprehensive Plan