at the "working face" of a sanitary landfill, municipal solid waste is dumped from trucks, compacted, and covered with dirt or fabric every night

at the "working face" of a sanitary landfill, municipal solid waste is dumped from trucks, compacted, and covered with dirt or fabric every night

Landfills today are designed for receiving Construction and Demolition Debris (CDD) or Municipal Solid Waste (MSW). Construction and Demolition Debris is waste from old structures when torn down, or leftover materials from new construction. Concrete, dirt, tree stumps, drywall, and other materials are hauled to a landfill. Metal and other items which are economical to recycle are sorted out, and the remainder is compacted to create an artificial hill. Because liquid waste is not accepted at such landfills, the risk of the contents migrating offsite is minimized.

Municipal solid waste landfills receive trash from houses and commercial operations, such as office buildings. Organic material, including yard waste and spoiled food items, is included in the contents trucked to such landfills. The organic material decomposes over time, and the resulting gases and fluids have the potential to migrate offsite.

Landfills storing municipal solid waste are high-tech operations compared to old "dumps." It is no longer acceptable to find an isolated tract of land near an urban area, dig a pit, then build a mountain of garbage. Similarly, old quarries are no longer suitable for use as landfills just because they are a hole in the ground into which debris can be dumped.

Modern landfills receiving municipal solid waste are engineered and built as a series of cells, designed to isolate the contents of the cells from groundwater. The cells include liners of plastic membranes and watertight clay on the bottom. At the end of each day, earth covers the trash deposited in the cell, to keep animals away. Bristol, Virginia opened a new landfill in an old limestone quarry in 1998, but used plastic membranes and watertight clay for separate cells.

When a cell is full, a thick cap of watertight clay is added at the top of each cell. This impervious clay blocks rainwater from seeping into the garbage and then into adjacent groundwater. Intricate plumbing systems are installed at different levels, to capture and release gases from decomposing waste before pressure builds up and cracks the clay covering.

The plumbing threaded through the landfill also collects the juices ("leachate") that are squeezed out of the garbage, plus groundwater/rainwater that manages to seep into the landfill and become contaminated. At some landfills, pipes carry the leachate to wastewater treatment facilities where the contaminants are separated from the water. At other landfills, leachate is collected in ponds and trucked to the treatment facility.

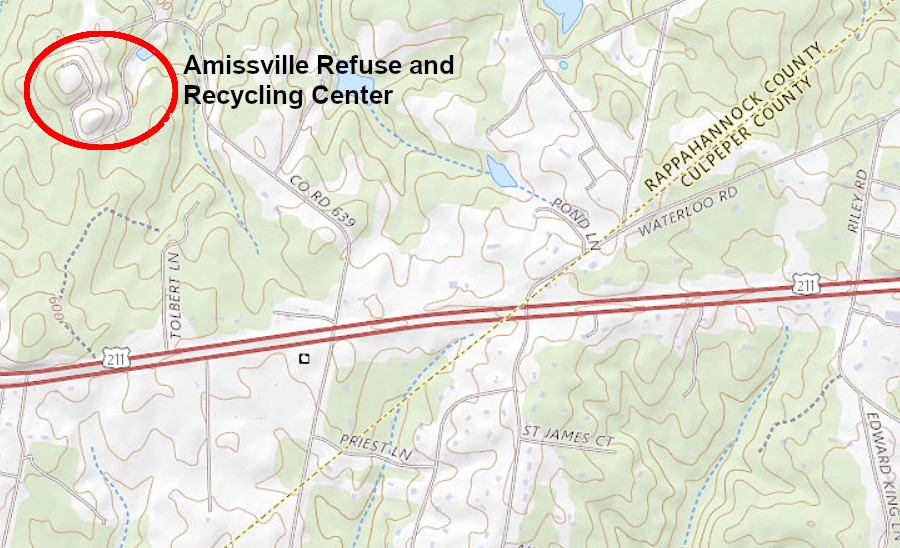

Rappahannock County was spending $80,000 per year to transport leachate, collected at its closed Amissville landfill, to Lynchburg for treatment. Much of the liquid pumped from the pond into trucks was just rainwater. The county built two underground storage tanks and redirected the leachate pipes, after calculating that it would recover the cost of the construction within just a year. The initial $88,000 cost saved $80,000 annually in hauling costs.1

replacing the leachate pond at Rappahannock County's Amissville landfill with an underground tank reduced the volume of leachate that had to be transported

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Sometimes the contaminants from the leachate are incinerated, and ash is buried in a specialized landfill for that product. In other cases, concentrated sludge from the water treatment plant is carried back to the landfill and buried there. Once a landfill is officially closed and sealed with clay at the top, the waste is isolated from the surrounding environment - at least in theory.

"white goods" (appliances) lined up for metal recycling at Prince William County landfill, with closed cell covered by clay cap in background

After World War II, municipal "dumps" were overflowing with ordinary, household-generated solid waste thanks to new packaging for consumer goods and increased consumption after the post-war baby boom. Between 1950-1960, the amount of municipal solid waste generated by the average person increased 60%.

The US Congress passed the Solid Waste Disposal Act of 1965, but it defined only minimum safety requirements for local landfills. In 1976, Congress passed a stronger waste management law, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA, pronounced "rick-ra").

Part C defined standards for handling hazardous wastes generated by commercial and research operations. Part D of RCRA added minimum requirements for locating and designing landfills that received municipal solid waste, including liner, leachate collection, and run-off controls. Part D also added Federal requirements for closure of landfills and post-closure care.

Garbage gradually compacts and chemically changes. Decomposition of organic material is slowed in the anaerobic (oxygen-deprived) environment, but is not stopped completely. Anecdotal stories tell of landfills being opened after decades, and newspapers had hardly turned yellow. Hot dogs with mustard looked just as good as the day they were tossed in the trash. Decomposition takes time, but all that material will gradually degrade.

Landfills create methane and other types of gas that bubble up to the surface and can crack the cap from below, if the pressure is not released. In addition to leachate pipes, modern landfills have internal plumbing for gas collection. For years drivers on I-66 near Fair Oaks Parkway could see the flare used to burn the methane coming from the now-closed landfill adjacent to the interstate.

After several decades of decay, bacterial decomposition of waste becomes minimal. Until then, surface inspections can ensure if the clay cap has settled or cracked. Monitoring wells can measure if the membranes, clay, and leachate collection processes actually prevent plumes of pollution from contaminating groundwater.

Gas trapped by a tire in a landfill can force it to the top and crack the clay cap, so modern landfills do not accept tires. According to the Federal Highway Administration:2

Virginia issued new solid waste regulations in 1988, updating 1971 regulations. Landfills that continued to accept waste after December 21, 1988 were required to install ground water monitoring wells. All new cells, at existing or new landfills, had to meet state-mandated requirements for liners, clay caps, gas release systems, and monitoring.

methane gas, generated naturally at landfills as organic materials decompose, is collected by a network of pipes and burned

Many non-compliant landfills stopped accepting waste in order to avoid the increased costs. In 1990, new mega-landfills opened in Charles City and Amelia counties to compete for the waste generated in Richmond and other communities in central Virginia. Atlantic Waste Disposal opened its mega-landfill near Waverly in Sussex County in 1993.

Increased tax revenue from the new landfills convinced local officials in those rural counties to be supportive, even though the solid waste disposal sites were a locally undesirable land use ("LULU") with impacts from traffic, noise, and odors. The landfills have been revenue-positive businesses, requiring few county services while paying millions of dollars to the host counties.

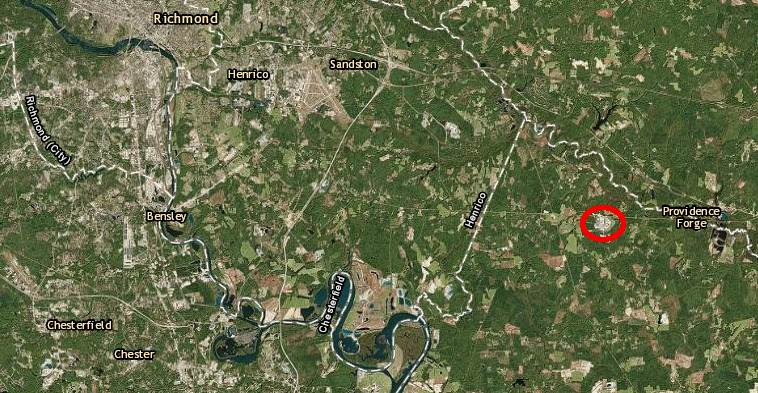

The Charles City Landfill was built where the cost of land was low, clay was available to meet the 1988 standards, and political officials were supportive. Transporting solid waste by truck is a major expense, so the site of the Charles City Landfill was attractive because it was close to Richmond. It was also close enough to the James River to import waste by barge from outside Virginia.

the Charles City Landfill was built close to Richmond to minimize the cost of transporting solid waste via truck

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Recycling reduced the volume of solid waste going to the landfill, and in 2015 the county modified its contract with the landfill operator to reduce the minimum amount of waste subject to payment by 25%. In 2020, however, the landfill operator applied for state and Federal permits to expand the facility and add 16 new cells.3

an expansion to add 16 new cells at the Charles City Landfill was proposed in 2020

Source: Virginia Marine Resources Commission, Habitat Management Permit Tracking System

adding cells at the Charles City Landfill increased the amount of solid waste it could hold in perpetuity

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (2022)

By 2020, Virginia had 45 solid waste landfills still in operation. There were 134 separate counties and cities in 2020, so obviously solid waste management was now a regional operation.

Public agencies and private landfill owners closed landfills that no longer met state regulations, or had reached capacity and further expansion was cost-effective. Fauquier County closed Landfill 149 at Corral Farm near Lord Fairfax Community College twice, once in 1996 and again in 2020. The facility lacked a liner at the bottom, allowing leachate to escape into groundwater. Federal regulations issued in 1993 required liners, so Fauquier County put a cap of soil on top of Landfill 149 in 1996 and opened up Landfill 575 for disposal of municipal solid waste.

The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality allowed the county to reopen Landfill 149 in 2001 for disposal of construction and demolition debris (CDD). After adding one million cubic yards of construction and demolition debris, recycling of that debris extended the life of the landfill. By 2020, however, there was no more room.

Closing down the Landfill 149 in 2001 in 2020 included adding a geomembrane cap to prevent rainwater from seeping into the solid waste. Adding the cap on top of the waste reduced the generation of leachate, but decomposition of material within the pile of waste and groundwater infiltration continued to produce fluids. Fauquier County had to continue to pump leachate and haul it to a wastewater treatment plant even after closure.

Landfill 575 also neared capacity after accepting over 300,000 tons of waste. Fauquier County started to ship its waste to Richmond in 2017, leaving a capacity of 1,450 more tons in Landfill 575. That delayed closing, so Fauquier County could pay finish paying for closure of Landfill 149 before starting to pay for closure of Landfill 575.

Because no waste was being accepted, in 2020 the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality listed the "Corral Farm Waste Management Facility" as the landfill in Virginia with the longest remaining life expectancy, estimated at 157 years. The Maplewood Recycling and Waste Disposal was next, with a life expectancy of 126 years.

Seven landfills were expected to reach capacity in less than 10 years - Botetourt County Landfill (1 year), Disposal and Recycling Services of Lunenburg (5.4 years), Louisa County Sanitary Landfill (9 years), one of the Prince Edward County Sanitary Landfills (4.6 years), Region 2000 Regional Landfill - Livestock Road Facility (7.1 years), Spotsylvania County Livingston Sanitary Landfill (2.5 years), and Tazewell County Landfill (3 years).

Average life expectancy for all Virginia landfills was 21.3 years. In 2020, the 45 permitted landfills still receiving waste had accepted a total of about 12 million tons of waste. Those landfills had available capacity to receive almost 250 more tons. The Atlantic Waste Disposal facility in Waverly had the greatest remaining capacity, with space for almost 44 million more tons.4

Fauquier County now ships municipal solid waste to Richmond for disposal

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

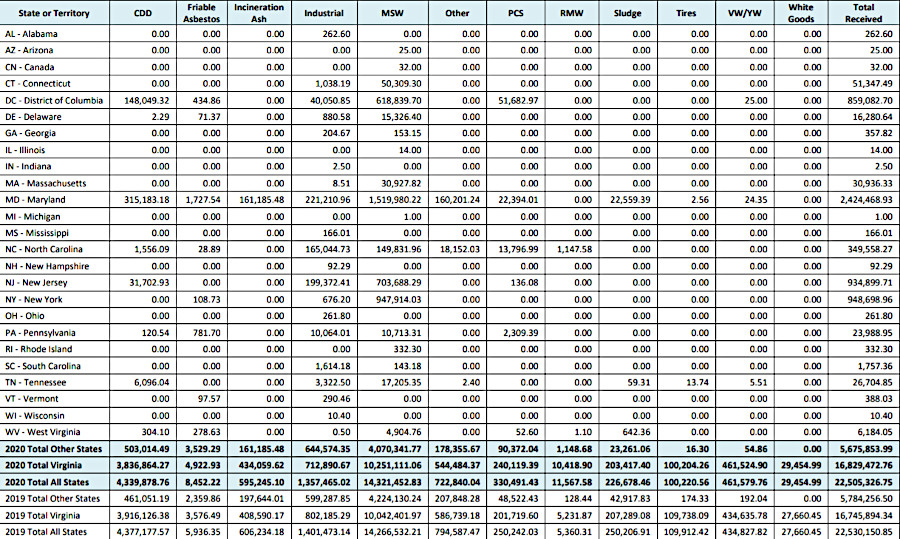

Waste is a commodity transported across state lines, and privately-owned landfills are competitive businesses. Some mega-landfill operators generate revenue by contracting with jurisdictions in other states.

Jurisdiction of Origin of Waste Received in Tons – 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2021 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2020 (Table 2)

In 1993, the General Assembly mandated in a law known as "HB 1205" that existing landfills that did not need new requirements must be closed. Old landfills would be permitted to continue accepting waste until their existing facilities were filled, but no horizontal expansion of old landfills would be permitted.

Old-fashioned dumping is occasionally practiced at old landfills, in violation of solid waste regulations issued by the Virginia Department on Environmental Quality (DEQ). In 2015, the Town of Pulaski was caught dumping untreated sewage waste in its former landfill on Draper Mountain.

The landfill had closed in 1988, after which the town used the site to dispose of dirt and construction debris. According to a town employee, town crews cleaned the filter at the town's main sewage pump station, loaded the grit into an 1,800-gallon tank truck, then carried the raw sewage to the old landfill:5

Old landfills must still be managed. The Catlett Mountain Landfill used by Front Royal and Warren County closed in the 1970's. Four decades later, excessive amounts of rainwater seeped through the clay cap and into nearby creeks. Those two jurisdictions spent nearly $200,000 to build a rainwater diversion system, even though that investment allowed no extra waste to be deposited at the old landfill.6

A 1999 proposal in the General Assembly would have created new fees to compensate those affected by the more-stringent environmental mandates. The cost to close a landfill is relatively clear, compared to the social cost (especially in human health) if an unsafe site is permitted to continue operating, but the one-time expenses to close a landfill can be steep. Asking a small rural county to absorb those costs directly was not the original plan of the General Assembly, but Governor Gilmore effectively blocked imposition of new fees that he perceived as new taxes.

Based on the recommendations in the Prioritization and Closure Schedule for HB 1205 Landfills report (issued July, 2000), the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) could force the two Virginia counties on the Eastern Shore out of the landfill business by the year 2020. Northampton County closed its landfill near the community of Oyster by the end of 2012, and began to convert the site into Seaside Park for recreational use.

the Northampton County landfill developed in two parts, on the north side of Brockenberry Creek and with Old Cannery (OC) landfill on the southern bank

Source: The GIS Spatial Data Server at Radford University, USGS Digital Raster Graphics (DRG) for Cheriton quad

before it was closed, the Northampton County landfill expanded to fill in a part of Brockenberry Creek

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Cheriton 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

Accomack County also closed one of its two landfills in 2012. According to DEQ's initial plans, the unlined cells at the South Landfill should have closed in 2005. The South Landfill finally closed at the end of 2012, and was replaced by a transfer station to transport waste to the North Landfill 40 miles away until it closes (or is expanded) in 2017. Accomack County budgeted over $4 million to cover the one-time closure costs of the South Landfill, and additional funds for monitoring will be required for 30 years.7

The two Eastern Shore counties could have built new landfill facilities to replace the ones being forced to close. However, there are great economies of scale in landfill construction and operations. It is inefficient to build small facilities, and two rural counties could not afford to borrow the necessary funds for a large high-tech facility that would always require taxes for an operating subsidy.

there are economies of scale in landfill operations, and larger landfills have lower costs/ton of waste to compact and cover material each night

The experience in Page County offers a lesson. The county leased its Battle Creek landfill, and then permitted the operator to grossly exceed the 250 ton/day limit in order to generate greater volume and thus more fees. DEQ ultimately revoked the permit for that landfill, and Page County will struggle to repay the costs for decades to come.

the location of landfills make some more competitive than others due to transportation costs, but landfills also compete for business by charging lower "tipping fees" for each truckload

On the Eastern Shore, the greatest waste management challenge is disposal of chicken manure (and dead chickens), not municipal solid waste.

Similar to Page County, there is not enough population or industry on the peninsula east of the Chesapeake Bay to generate large amounts of waste. Low volume/day makes a large landfill on the Eastern Shore an unattractive investment.

The Eastern Shore counties have been unable to recruit neighboring jurisdictions in Maryland to share the cost of a regional, interstate facility. The Hampton Roads communities already have a regional disposal authority. Because of cost, they have been unwilling to ship garbage across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel to supply a second regional landfill on the Eastern Shore. That has forced Northampton County to absorb the cost of shipping its waste to a landfill west of the Chesapeake Bay.

In 2009, Northampton County completed a $2 million transfer station, a facility where local garbage collection trucks deposit waste at a temporary collection point. The solid waste is trucked from the transfer station to a sanitary landfill far away in King and Queen County.

That two-stage transfer process, transferring waste at the transfer station into large trucks, is more cost-effective than having gas-guzzling local garbage trucks drive all the way to the landfill in King and Queen County. To reduce transfer costs, brush is burned at the transfer station and valuable scrap metal is recycled there, rather than shipped to the landfill.8

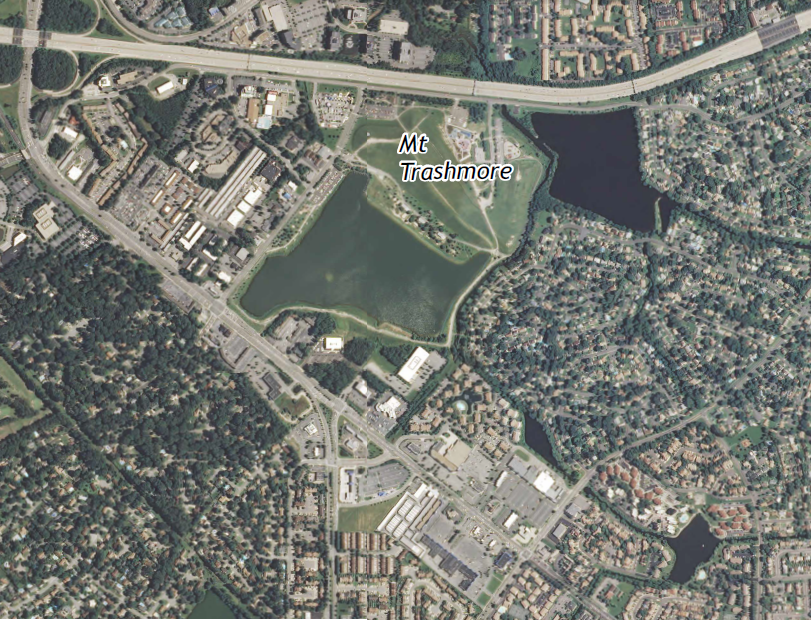

Virginia Beach used a creative process to close its landfill. It compacted and piled solid waste into Mount Trashmore, building the cells vertically over 60 feet high. After closing the landfill and capping it with clay, Virginia Beach had created the tallest spot of land in the city. It made the site into a public park, with vents in select locations to dispose of methane generated by the waste decomposing within the "mountain."

The garbage continues to decay slowly underneath the clay cap. It burps gases out the vent pipes regularly, but the city succeeded in converting a waste site into a valued recreational asset. After closing the landfill, the city began shipping its solid waste to the Southeastern Public Service Authority (SPSA) waste-to-energy plant in Portsmouth and the SPSA's landfill in Suffolk.

Mount Trashmore, south of I-264, is now a recreational asset for nearby homes and offices

Source: US Geological Survey, Princess Anne and Kempsville 7.5x7.5 topographic quads (2013)

Grass is planted on the clay cover above closed cells of landfills to reduce erosion. Trees are not planted, because their roots might penetrate the clay cap. That would allow rainwater to enter the cells, become polluted, and then to leak out.

The City of Portsmouth bought goats, figuring they would keep the grass cut at its landfill on the southern edge of Craney Island. After discovering their goats were finicky eaters, city officials bought sheep as well - and the urban managers also bought a book on how to raise sheep.

After a year, Portsmouth officials realized that using farm animals to cut grass was not the easy solution originally imagined. Costs to manage the animals and ensure their heath were higher than the costs of traditional lawn care. The final solution: Portsmouth acquired two lawn mowers to cut most of the grass on the landfill.9

The same city official who initiated the goat project later proposed creating a mulching operation at the Craney Island landfill. Supervisors rejected the proposal, but he purchased $500,000 of equipment without approval. He resigned in 2015 just before he would have been fired. He learned that "just do it and ask for forgiveness later" innovation was not acceptable, when the costs exceeded benefits.10

goats were used (unsuccessfully) to cut the grass on the Portsmouth landfill west of the Craney Island Fuel Depot

Source: US Geological Survey, Norfolk North 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

In the 1980's, Arlington and Alexandria realized they were running out of landfill space for disposal of solid waste, and the costs to meet the new state regulations was going to be high. Arlington and Alexandria chose to abandon disposal in landfills and joined together to build a joint waste-to-energy facility, implementing a new technology to solve an old problem.

Fairfax also built a waste-to-energy facility at Lorton. In Fairfax County, trucks haul solid waste between waste transfer stations (including one at the old I-66 landfill) and the waste-to-energy facility (incinerator) at Lorton or the Prince William County landfill. The trailers of those trucks are a distinctive tan color.

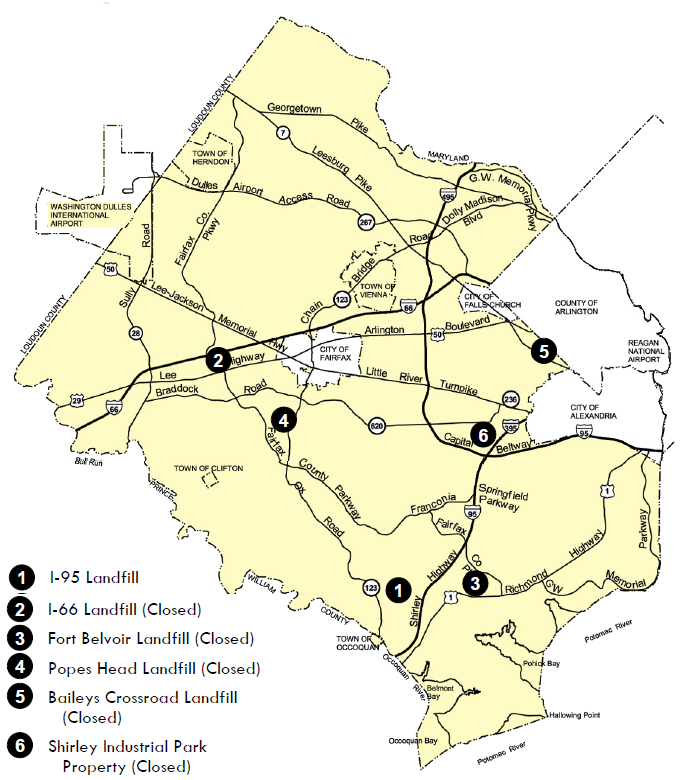

Fairfax County has closed all municipal solid waste landfills except one, the I-95 Landfill near Lorton

Source: Fairfax County Solid Waste Management Plan, Appendix D - Solid Waste Facilities in Fairfax County

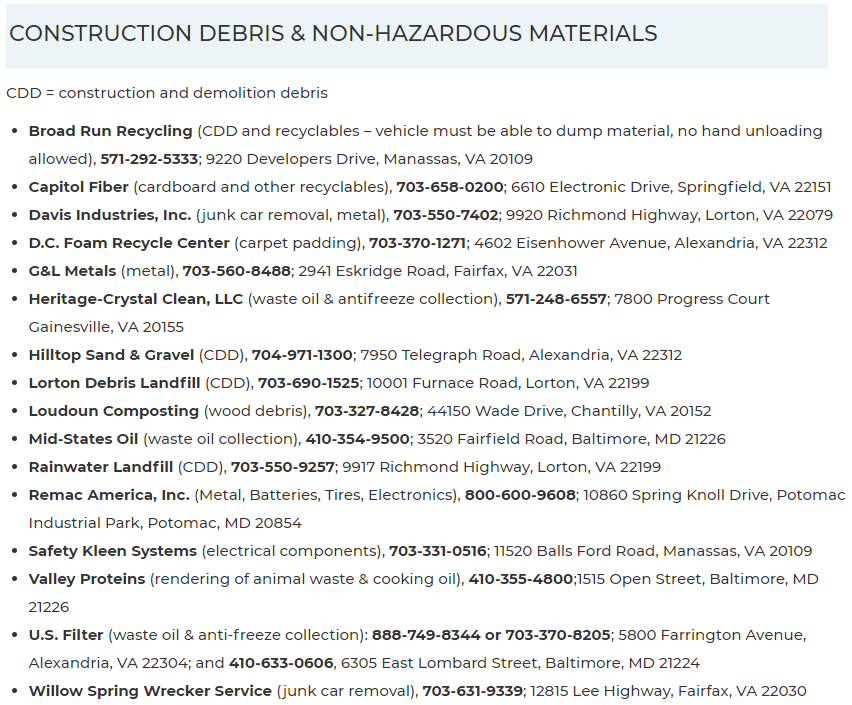

Fairfax County has closed all of its municipal solid waste landfills; municipal solid waste is directed to the incinerator at Lorton. Citizens may bring pickup trucks and small trailers with stone/gravel/rock, concrete/cement, brick/block, and asphalt/tar to the I-95 Landfill for disposal. The Rainwater Construction and Demolition Debris (CDD) landfill remains open, but commercial builders in Fairfax must truck much of their cleared vegetation, demolished buildings, and dirt scraped from construction sites to other jurisdictions.

options for disposal of waste in southern Fairfax County have been constrained by landfill closures

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Fairfax County advertises landfill disposal sites and recycling companies located in Maryland, Alexandria, and Prince William County

Source: Fairfax County, Disposal Companies for Specialized or Hazardous Waste

The major CDD landfill at Lorton next to the I-95 Landfill closed in 2018. EnviroSolutions had tried to keep that 250-acre facility open, extending a deal negotiated by with nearby residents in 2006. That deal had authorized a short-term expansion, followed by conversion of the landfill into a public park.

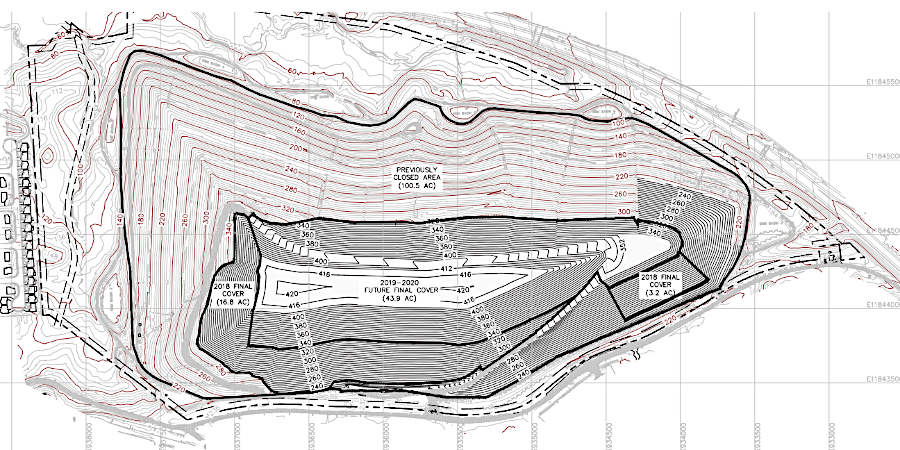

the Construction and Demolition Debris (CDD) landfill at Lorton did not reach its maximum permitted height (412') before the facility closed in 2018

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Fort Belvoir 7.5x7.5 topographic quadrangle (2013)

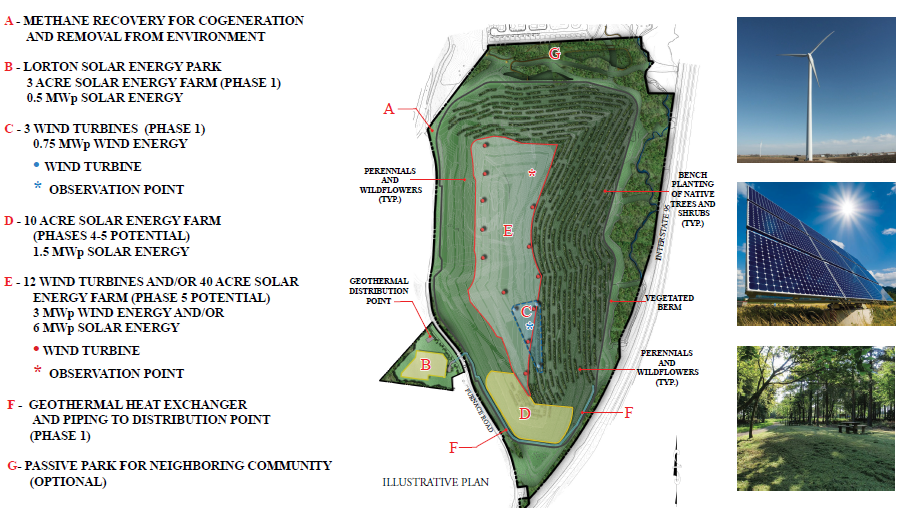

In 2014, EnviroSolutions proposed keeping the landfill open until 2040. The 2008 recession had slowed construction projects dramatically, and the company was not receiving construction and demolition debris fast enough to reach the maximum authorized height of 412 feet (roughly 50' higher than its elevation in 2014) in 2018. In exchange for the 22-year extension of time to reach maximum utilization of the site, EnviroSolutions proposed to add solar cells, geothermal energy, and wind turbines to create a green energy park.11

County staff supported changing the commitments made in 2006, recognizing that redevelopment (especially in Tyson's) created debris and a nearby disposal site would incentivize further redevelopment. Local opposition was strong, in part because the company had already changed its commitment to build the public park in order to minimize long-term liability insurance costs.

In 2014 the Board of County Supervisors in Fairfax finally rejected the last compromise proposal, which would keep the landfill open until 2025, in a close 6-4 vote. The landfill operator made clear it would simply shift operations to a nine-acre parcel that it owned next to the landfill, using it as a transfer station before shipping the construction and demolition debris to another site. The company warned that the amount of construction truck traffic in the neighborhood will not drop once the landfill closes.12

the owner of the private construction and demolition debris (C&DD) landfill at Lorton proposed a green energy park, if Fairfax County would authorize a longer lifespan

Source: EnviroSolutions, Fairfax Green Energy Triangle

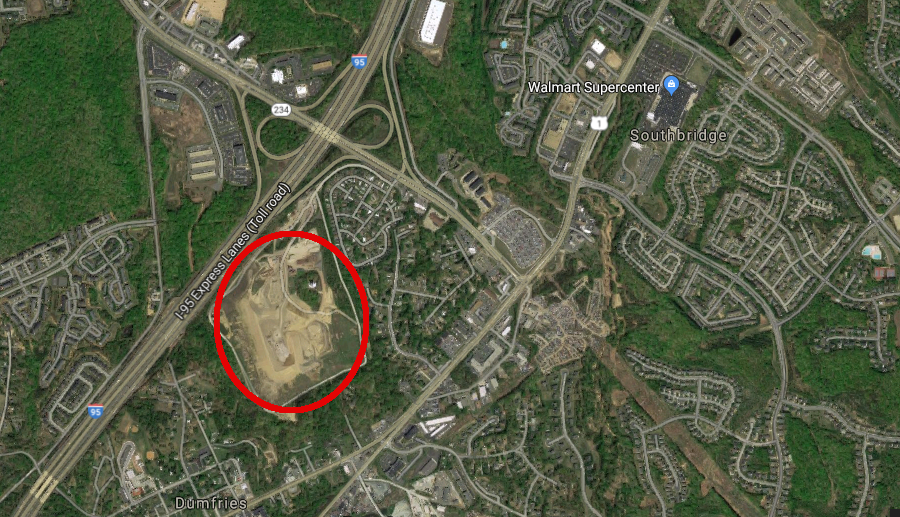

The Fairfax County decision led to a final resolution of the fate of the nearby Potomac Landfill, which had opened in 1984 at the I-95/Route 234 intersection in Dumfries.

In 2005, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) tried to force the Potomac Landfill to close by 2010 because of the persistent odors it generated. Instead of closing, the landfill managed to find ways to continue accepting debris and processing it for recycling materials. Neighbors continued to complain about noise and odor, plus leachate and even rats coming out of the site.

the Potomac Landfill on I-95 at Dumfries became the primary site for disposal of local construction and demolition debris, after Fairfax County forced its competitor in Lorton to close

Source: Google Maps

In 2012, the state agency ordered Potomac Landfill to lower the height of the debris mound. It had reached 220 feet, exceeding the level of 195 feet authorized in the state's solid waste permit. The landfill was also fined $50,000, after discovery that excessive amounts of leachate had ponded at the base of the debris pile. Instead of being processed correctly, untreated liquid was being pumped back to the top of the mound to trickle through the debris again. Some was being pumped into the county sewer system without authorization.

Despite the site's problems, the Fairfax County decision in 2014 to block expansion of the Lorton landfill made Potomac Landfill the primary location for disposal of construction material in that part of fast-growing Northern Virginia. That significantly increased the potential value of the 100-acre Dumfries site.

In 2016, the owner settled a lawsuit with the Town of Dumfries and resolved the conflict with the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. The landfill agreed to pay a "host fee" that could total $4 million. In exchange, it got authorization to reach a 250-foot height and to stay open until 2032.

After closure, the landfill owner anticipated that the mound of debris might host recreational ballfields, while land at the base could be developed for housing and commercial uses. Reclaiming the land for beneficial use was in contrast to a 2012 proposal to get authorization to pile debris up to 310 feet high and closing the landfill 15 years earlier. The landfill owner later commented:13

after planned closure in 2032, the site of the Potomac Landfill could be reused for recreation, housing, and commercial development

Source: Town of Dumfries, Potomac Landfill Expansion and End Use Proposal

The Potomac Landfill closed in 2022, ten years earlier than planned. It was purchased by a gaming company that owned the Colonial Downs horse track and had opened an off-track betting facility, Rosie's Gaming Emporium, in Dumfries. The town endorsed quickly approved plans for "The Rose," with buildings planned on 12 acres at the base of the landfill and 79 acres of park on the clay cap of the landfill.

The Rose was designed to be a $400 million resort booking top-quality musicians for a 1,500-seat theater, attracting tourists to stay in a six-story high-quality hotel. The initial gaming would be restricted to off-track betting, but the site was well positioned to become a full-scale casino with table games and traditional slot machines if the General Assembly authorized a Northern Virginia license at a later date.14

The Rose gaming resort ended dumping of debris at the Potomac Landfill in 2022, after 38 years of landfill operations

Source: Rose Gaming Resort

Landfills are rich in organic material, so they attract rats, other mammals, and birds. Covering the discarded waste every night with a thin layer of clay or dirt reduces the problem in the evening, but during the day other techniques are required.

The 900 tons/day discarded at Prince William County's landfill attracted 25,000 seagulls and other birds daily. The annual Christmas Bird Count in the county found more eagles at that inland location than along the Potomac River waterfront; the seagulls fed on the waste, and the eagles fed on the seagulls.

While the eagles were welcomed, the mass of other birds created their own solid waste problem. The county abandoned recreational ballfields at the landfill to avoid the excessive bird droppings, and paint on nearby vehicles and buildings were damaged by the steady rain of fecal material.

The county contracted with US Department of Agriculture - Wildlife Services to reduce the bird concentration through non-lethal techniques (bird repellents, pyrotechnics, shooting with paintball guns) and also through lethal means. Since the birds were protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, killing or disturbing their nests/eggs required approval of the Federal government. In the first winter of control measures (2013-14), the bird population at the landfill was reduced by 70% to just 7,500/day.15

Source: Prince William County, The Prince William County Landfill

In 1993, Virginia was the first state to gain authorization from EPA to manage the RCRA program. The Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issues permits for landfills, and ensures compliance when landfill operators fail to meet standards. For example, starting in 2014 neighbors noticed odors coming from the active landfill in Sussex County that had been constructed initially by Atlantic Waste Disposal, a subsidiary of Waste Management Inc., in 1993. Chemical interactions within the buried municipal solid waste generated heat that "cooked" the trash, creating 15-foot wide sinkholes and triggering release of gases.

Atlantic Waste Disposal spent nearly $16 million to stop the odors, but that same landfill then released leachate in 2016. The liquid had been generated from within the decomposing waste, or was stormwater that had infiltrated into the cell and flowed through the waste. Flow increased, and holding ponds did not capture all of the leachate. Some leaked offsite into adjacent swamps and ultimately to the Nottoway River.

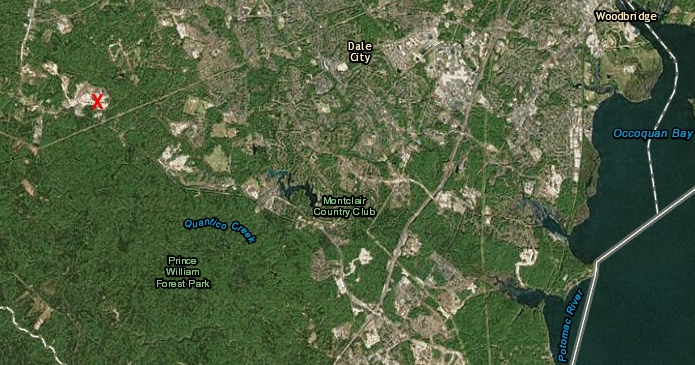

seagulls - and bald eagles - find it easier to feed at the Prince William County landfill (red X) than on the Potomac River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia DEQ negotiated a settlement agreement with Atlantic Waste Disposal. It included a token $99,000 fine, plus a schedule to removing the accumulated leachate from the holding ponds by trucking it to a terminal in Chesapeake and shipping it to New Jersey for disposal. That settlement required the landfill operator to spend a substantial amount of money to correct the problem, but did not impose a substantial penalty for failure to meet the initial permit requirements.16

Atlantic Waste Disposal, a subsidiary of Waste Management Inc., used holding ponds to capture the excessive flow of leachate from its large commercial landfill in Sussex County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

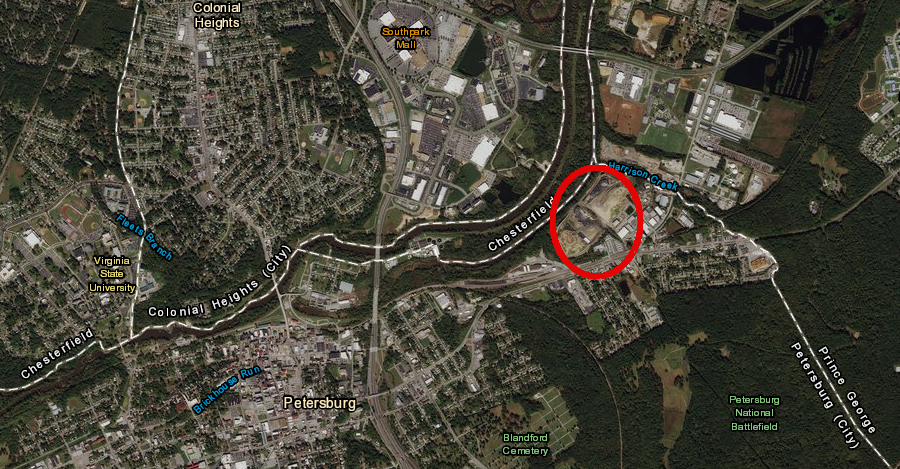

In 2018, the Department of Environmental Quality proposed a far more significant action in response to continuing problems with odors, stormwater runoff, and uncovered trash at the Tri-City Regional Landfill.

In addition to fines of $32,500 per day for the violations, the state agency proposed revoking the permit that had been issued to CFS Group Disposal and Recycling Services. Revoking the permit would force closure of the facility on Puddledock Road.17

the Department of Environmental Quality proposed closing the Tri-Cities landfill used by Petersburg, Colonial Heights, and Hopewell

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A site used for a modern landfill will be dedicated to that use for decades and perhaps centuries, long after the cells are filled and a clay cap installed as a permanent cover. Grass may grow on a former landfill, but trees that grow bigger roots which could penetrate the clay cap must be cleared off regularly.

Unlike Mount Trashmore in Virginia Beach, most former landfills are not repurposed. Building any structure on a landfill cell creates risk. As waste slowly decomposes, the clay cap sealing the top will gradually sink and move anything on the surface out of alignment.

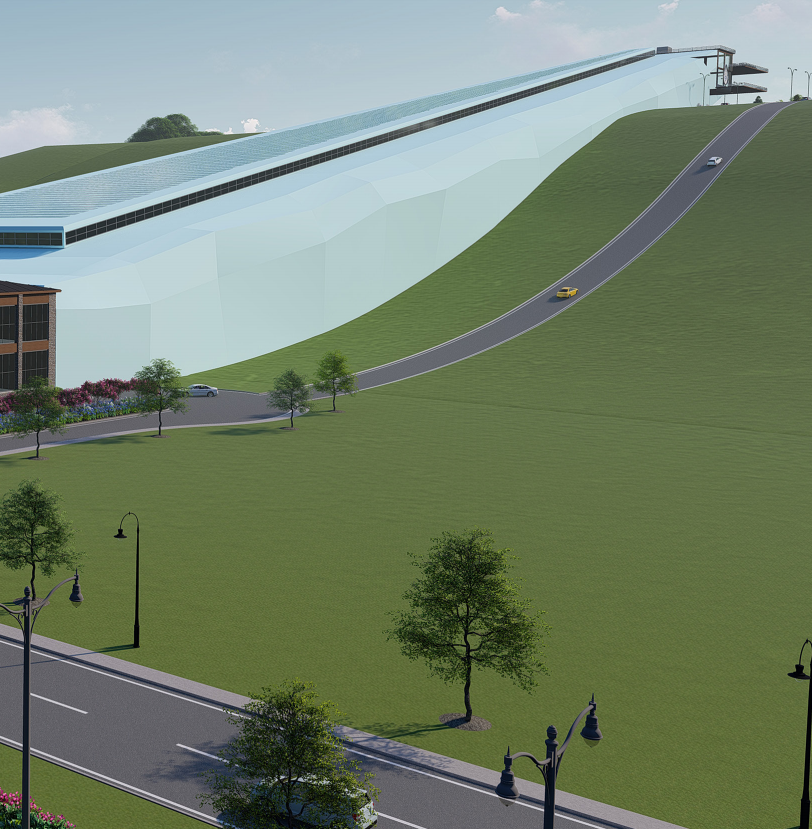

In 2020 Fairfax County committed to support creation of an indoor ski slope, "Fairfax Peak," at the old I-95 Lorton Landfill. That landfill was no longer being used for deposition of municipal solid waste, though it was still receiving ash from the adjacent waste-to-energy facility owned by Covanta.

Alpine-X and SnowWorld USA made an unsolicited proposal in 2018 to create a flagship indoor ski facility, Peak Fairfax, on the county's closed landfill cells:18

SnowWorld USA proposed to operate an indoor ski slope, using the I-95 Lorton landfill to create a 20 degree slope

Source: Alpine-X LLC, PPEA Proposal - Fairfax Peak, Sports Entertainment and Active Lifestyle Community (p.59)

Fairfax Peak would resemble the SnowWorld facility at Landgraaf, in the Netherlands

Source: Alpine-X LLC, PPEA Proposal - Fairfax Peak, Sports Entertainment and Active Lifestyle Community (p.38)

The developers was unable to find private sector funding for the Peak Fairfax proposal. Their exclusive option to develop a ski park on the I-95 Lorton Landfill expired at the end of 2024, when costs were estimated at $400 million.

Still viable were proposals received by the county in 2022 to build a municipal solid waste sorting and/or an advanced recycling facility on 16 acres of the 489-acre landfill, separate from the proposed ski park. The proposed facility, sponsored by the Fairfax County Department of Public Works and Environmental Services (DPWES) after receiving an unsolicited proposal, would reclaim organics, fiber, and metals from 650,000 tons of solid waste per year.19

16 acres at the I-95 Lorton Landfill could be used for a municipal solid waste sorting and/or an advanced recycling facility

Source: Fairfax County, Advanced Recycling Facility Project Area - Recommended Area for Request for Competing Proposals

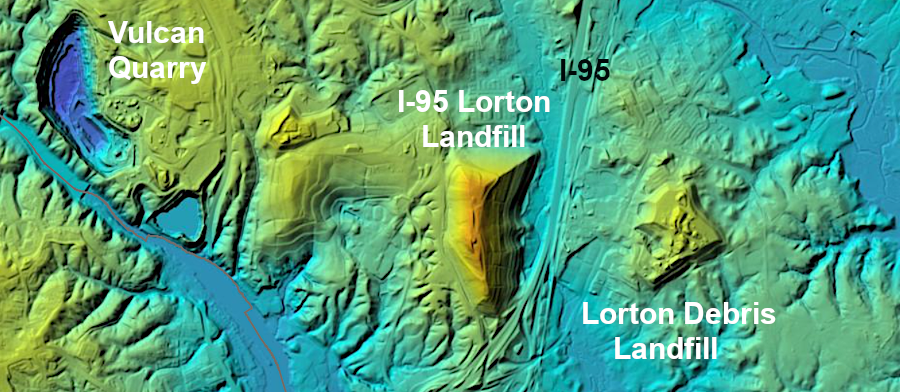

Just to the east of the I-95 Lorton Landfill owned by Fairfax County was the Lorton Debris Landfill, a privately-owned construction and demolition debris landfill.

the I-95 Lorton Landfill is west of I-95, and the Lorton Debris Landfill is east of the interstate highway

Source: Fairfax County, LiDAR Elevation Viewer

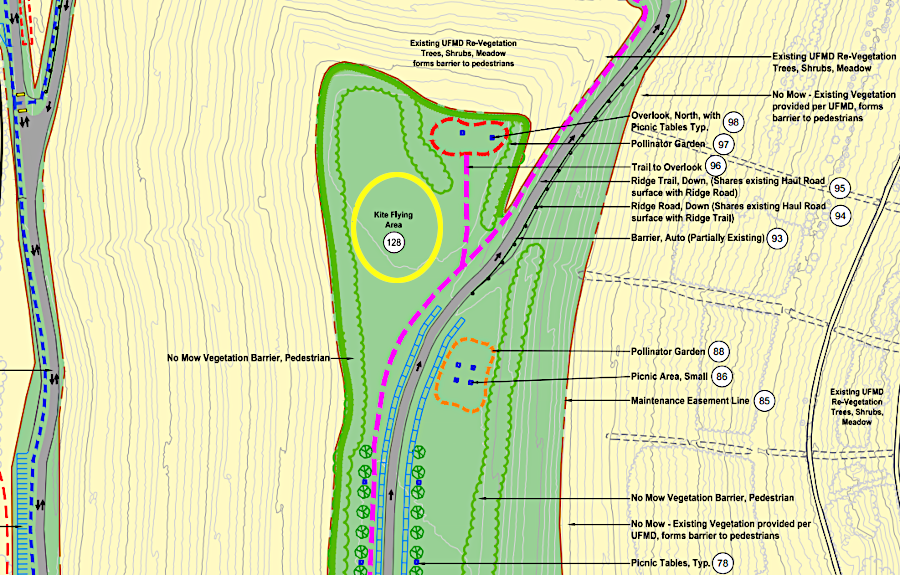

The Lorton Debris Landfill stopped accepting new waste in 2018, and the county planned for converting it into Overlook Ridge Park by 2025. The local county supervisor announced:20

piling up construction and demolition debris at the Lorton Debris Landfill created the tallest spot in Fairfax County

Source: Fairfax County, Record 2232-2022-MV-00001: Overlook Ridge Park (Overlook Ridge Photographic Log - Photo 6 looking south)

closure of the Lorton Debris Landfill required two years to cap the construction and demolition debris and prepare for repurposing the site as a public park

Source: Fairfax County, Lorton Closure and Post Closure Plan

plans for Overlook Ridge Park on the highest spot in Fairfax County included an area for flying kites

Source: Fairfax County, Record 2232-2022-MV-00001: Overlook Ridge Park (Attachment 4: Site Plan Conceptual plan)

An even greater risk is a cracked cap, which could be caused by tree roots underground, a structure on the surface, or a buried tire "floating" upwards after trapping landfill gas or biogas (mostly methane and carbon dioxide). Cracks would allow rainwater to enter a landfill cell and emerge with pollutants. As a result, landfill operators prevent trees from growing on old landfills and avoid building structures on them, and tires are kept out of landfills.

Caps are exposed to full sun, but are a poor location for solar panels. They typically require posts/foundations that could penetrate into the clay cap, and the weight/stresses of panels during a windstorm could shift a landfill's clay coating enough to cause cracks.21

In contrast, the clay cap on a coal ash pond does not sink. Coal ash is not organic, so it does not decompose and lose volume over time. Bacteria affects municipal solid waste but not coal ash, so a closed coal ash landfill has more potential for beneficial reuse. Dominion Virginia Power even arranged for Battlefield Golf Club to be constructed immediately on top of coal ash deposited in the city of Chesapeake.

Long-term limitations on reuse of landfill sites could last for centuries. A key conclusion from research is that:22

In the 1990's, the Environmental Protection Agency began to fund Project XL to explore speeding up the decomposition process. The Federal agency and landfill operators studied how adding leachate from the landfill, or water from external sources, could convert landfill cells into managed "bioreactors." The process required waivers from Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulations that restricted disposal of wet items, such as sludge from wastewater treatment plants, within solid waste landfills.

With supplemental water, bacteria decomposes waste faster. Faster decomposition creates biogases more rapidly, and they must be released. A greater volume of methane would make it more cost-effective to install generators to produce electricity until much of the decomposition is completed.

In Virginia, Waste Management and EPA proposed to test recirculation of leachate (the fluid that accumulates in the landfill during decomposition) at the Maplewood (Amelia) Landfill. In a parallel test, additional streams of liquid would be added at the King George County landfill to stimulate faster bioreactor operations. If decomposition could be accelerated, landfill monitoring could end sooner (reducing costs) and the site could be reutilized sooner.23

Leachate was pumped out of four phases (constructed cells) of the landfill and stored in a tank. Until 2008, the leachate was injected into Phases 1 and 2 of Maplewood Landfill. Those phases were operated as bioreactors, while Phases 3 and 4 were operated as control landfill cells with no leachate recirculation.

Leachate Testing ended in 2008, when leachate added to the recirculation trenches stopped draining into the landfill. In both the bioreactors and the control cells, the percentage of methane remained consistent at 50-60% of total volume. The conclusion when testing ended in 2010 suggested there were no extra benefits, but the settlement of the clay cap was different:24

At the King George Landfill, Cell 3 was altered to serve as a bioreactor while Cells 1, 2, and 4 were used as controls with no recirculated leachate or other liquids. The last report from the test project noted:25

After two years, infiltration rate of the trenches decreased significantly and testing stopped. At that time, the composition of the landfill gas was not significantly different between the bioreactor test cell and the control cells; additional methane was not being generated by faster decomposition.

The last report concluded:26

Sanitary Landfills and Incinerators (2008) and Out-of-State Waste Accepted at Private Sanitary Landfills (2007)

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Figure 2

The Rappahannock County landfill, after closure in 2000, was replaced with the Flatwood Refuse and Recycling Center. Customers dropped waste into an open pit with a mechanical roof for cover at night, and a Culpeper County contractor hauled the waste on a weekly basis to the Clifton Clark landfill. Around the county were green dumpster boxes, and people from surrounding counties found those more convenient than using their own jurisdiction's solid waste collection facilities.

The Amissville Refuse and Recycling Center in Rappahannock County was only one mile from the Culpeper County border. Half of the users dumping municipal solid waste at Rappahannock County's Amissville facility were Culpeper County residents.

Landfill costs per user were calculated by Rappahannock County in 2023, triggering a proposal to allow only county residents to use the county landfill. That caused concern in northern Culpeper County, because that county's solid waste facilities were far away. The Laurel Valley Solid Waste Transfer Station was 15 miles south of the northern edge of Culpeper County, and the Lignum Convenience Center was 20 miles away.

in 2023, Rappahannock County authorized Culpeper County residents to pay $28/month to use the Amissville Refuse and Recycling Center)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Rappahannock and Culpeper counties negotiated an arrangement which allowed Culpeper County residents to use Rappahannock County landfills, after buying a decal that cost $28/month. The cost was based on the average amount of waste created per household, as estimated by the Environmental Protection Agency, plus the costs for Rappahannock County to provide the space for waste and to manage the waste transfer station.

Culpeper County residents could still dump waste at their own county facilities for free, up to 500 pounds/month. Rappahannock County residents also had free use of that county's solid waste facilities, since local taxes covered costs of the waste management program.27

Fairfax County installed the first solar array on a closed landfill in Virginia. A solar project developer, Madison Energy Infrastructure, partnered with the county to cover 37 acres of the closed I-95 landfill and generate credits from Dominion Energy for the electricity generated by the solar panels. Fairfax County anticipated the 5MW project, going into service in 2026, would save $12 million on energy costs over 30 years.28

Source: Fairfax County, Fairfax County Breaks Ground on Largest Solar Project at I-95 Landfill

In 2025, the 40 active landfills in Virginia were an average of 42 years old. A lawyer advocating for a new private mega-landfill in Cumberland County stated that no new private landfills had been created in Virginia for the last 25 years, and said:29

In Russell County, local officials were considering a new private landfill on the site of the Moss No. 3 mine and coal preparation plant, owned by Russell County Reclamation. Almmost 120 million tons of coal waste were located there in a shallow valley between two coal refuse dams. Some "gob coal" was being processed for sale to the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in St. Paul.

About 30 acres of the 1,200-acre site would be used for the landfill cells. The county was paying Waste Management to truck solid waste to a facility in Blountville, Tennessee, after the City of Bristol closed its landfill in September 2022. It estimated that creating a public landfill would cost up to $15 million. A private landfill paying a host fee could be an economic development project, providing at least $750,000 annually to the county.

Opponents of covering the Moss No. 3 site included the United Mine Workers of America. They considered the mine to be a key historic site associated with the Pittston Coal strike in 1989-90; strikers had formed a human shield around the plant as part of a four-day takeover. A Sierra Club opponent said:30

In June 2024, Russell County supervisors ended negotiations with Russell County Reclamation for development of the private landfill. For the last six months opponents had spoken out at Board of Supervisor meetings, picketed events which attracted state officials (including Governor Youngkin) to Southwest Virginia, and installed roadside signs saying "Do You Smell That? Well, You May Soon." A petition to recall one of the supervisors was also widely circulated.31

in 2024, Russell County officials stopped negotiating for development of a private landfill at the site of Moss Mine No. 3

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

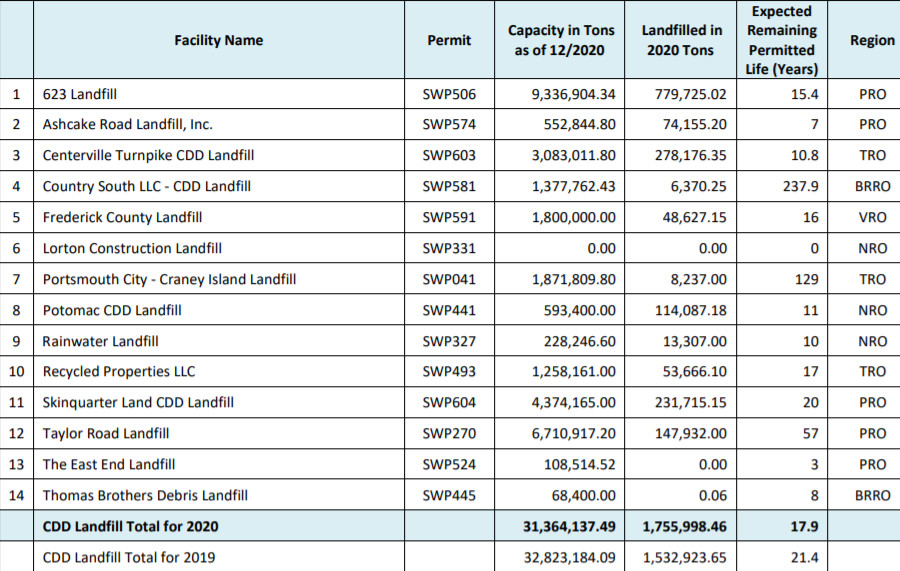

Capacity and Remaining Life for Construction and Demolition Debris (CDD) Landfills – 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2021 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2020 (Table 6)

incinerators reduced the volume of waste, but incinerator ash also required landfill space

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2021 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2020

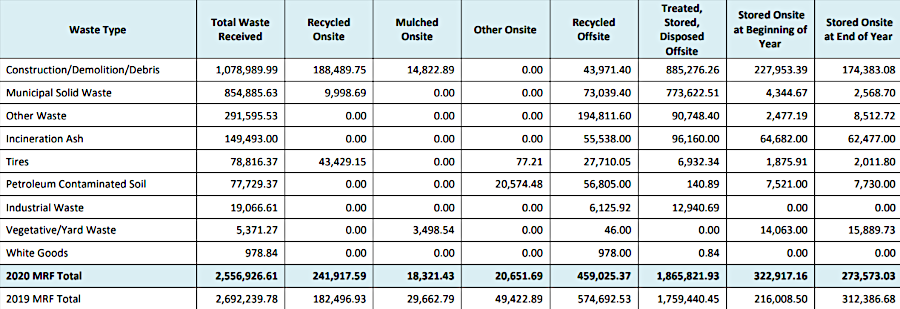

Solid Waste Managed by Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) in Tons – 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), 2021 Annual Solid Waste Report for CY2020 (Table 13)

external sources of waste imported into Virginia in 2008

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Waste Reduction Efforts

in Virginia (Commission Briefing - September 8, 2008)