Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

PFAS were a component of aqueous film-forming foams used to fight liquid fuel fires

Source: National Archives, US Air Force (USAF) Fire fighters with the 167th Air Wing (AW), West Virginia Air National Guard (WVANG), quench a simulated aircraft fire during a training session

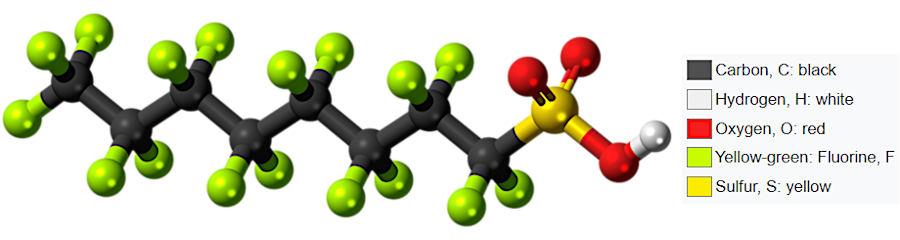

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are called "forever chemicals" because the molecules are so tightly bonded that natural degradation occurs very slowly. There are 12,000 chemicals in the PFAS group.

Destroying the carbon-fluorine bond is possible through a number of expensive processes. Supercritical water oxidation requires carefully heating and pressurizing water to specific points. Sound waves passing through a liquid can create bubbles that, when they collapse, generate high temperatures and pressure sufficient to pull carbon and fluorine atoms apart.

The hydrothermal alkaline treatment (HALT) involves adding sodium hydroxide to superheated liquid water, creating a "pressure cooker on steroids." Ultraviolet light and even high-energy plasma can be used to break the bonds. Other techniques using sodium hydroxide may be sufficient at lower temperatures, reducing the cost to destroy PFAS and similar chemicals.

PFAS were used in manufacture of stain and water repellent material, food packaging and other consumer products, plus fire-fighting foam. A detectable level of PFAS is estimated to be present in 45% of drinking water supplies in the United States, ranging from 8% in rural area served by wells to 70% in urban areas drawing water from lakes and rivers.1

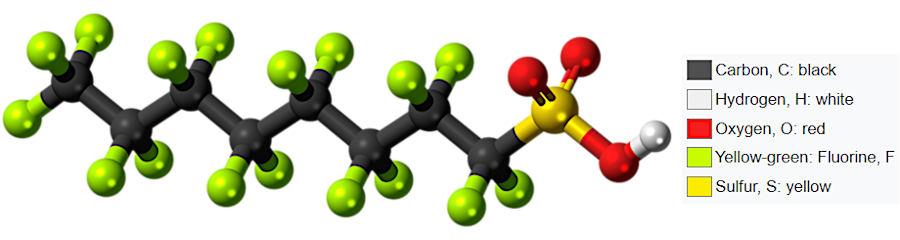

PFAS molecules form "forever chemicals" because bonds between atoms are especially strong and thus slow to break apart

Source: Wikipedia, Sustancias perfluoroalquiladas

By 2015, at last one of 32 types of PFAS were found in the blood of 95% of Americans. The health effects were not fully understood, but researchers were targeting cancers, delayed development of children, and fertility impacts. At last 75% of tap water tested in urban areas had a last one form of PFAS. In rural areas, 25% of drinking water systems were contaminated.2

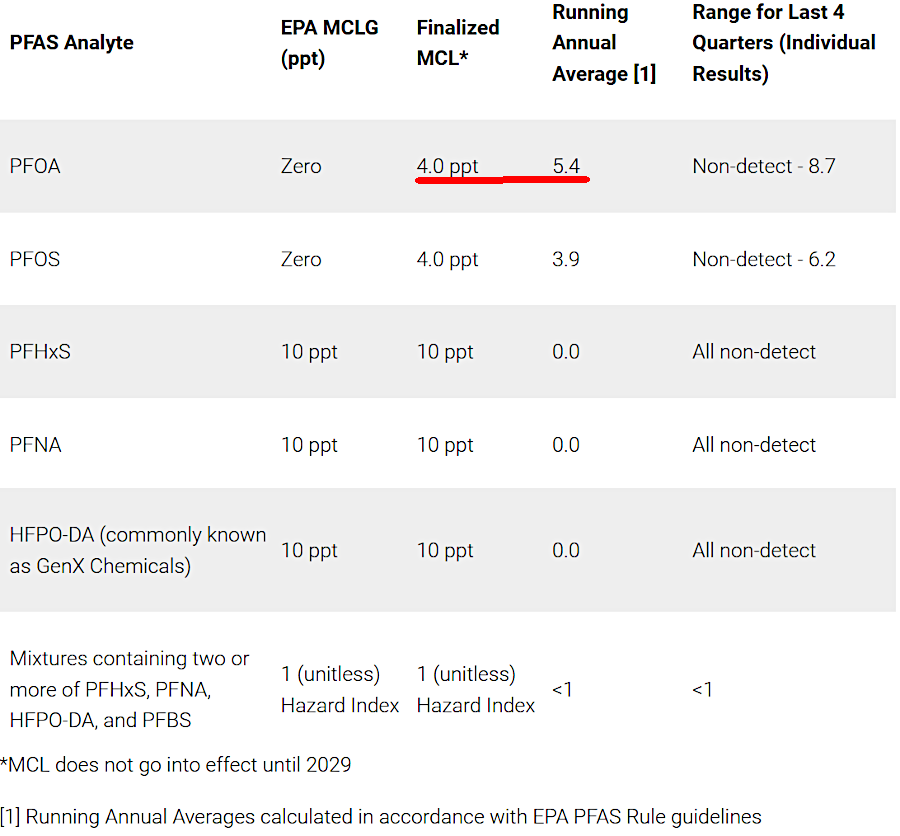

In 2023, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed drinking water standards to limit PFAs to no more than 4 parts per trillion:3

- On March 14, 2023, EPA announced the proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for six PFAS including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA, commonly known as GenX Chemicals), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS)...

- EPA is proposing a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) to establish legally enforceable levels, called Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs), for six PFAS in drinking water. PFOA and PFOS as individual contaminants, and PFHxS, PFNA, PFBS, and HFPO-DA (commonly referred to as GenX Chemicals) as a PFAS mixture. EPA is also proposing health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) for these six PFAS.

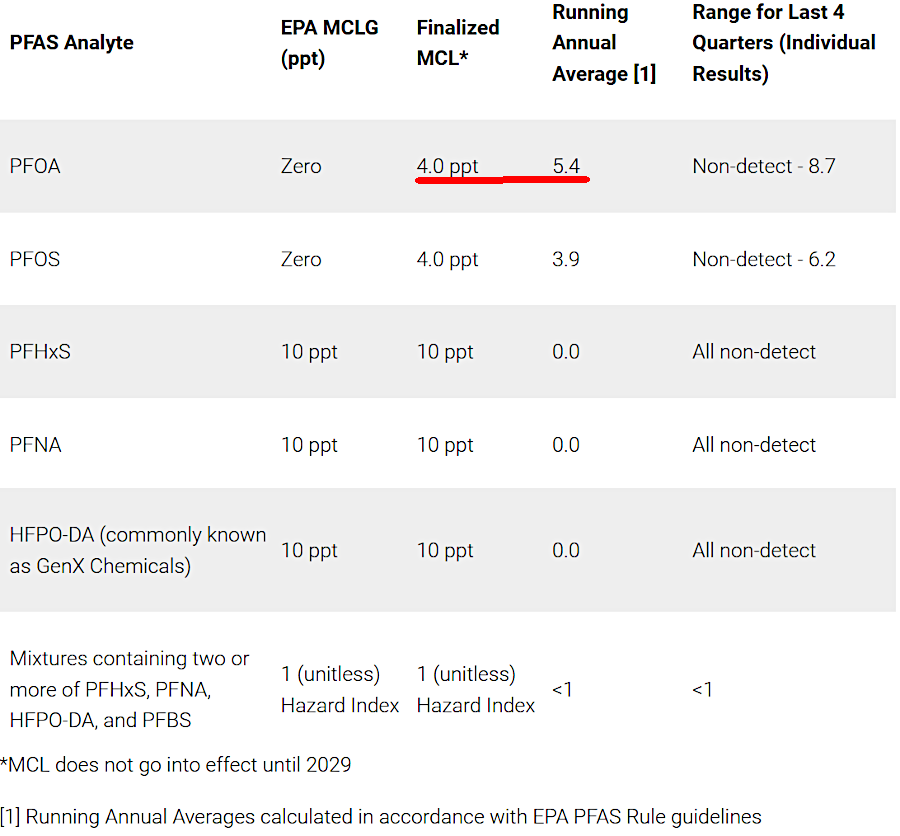

in 2024, finished drinking water sold to customers from Fairfax Water's Griffith Treatment Plant exceeded new EPA standards for PFOA starting in 2029

Source: Fairfax Water, Facts About PFAS

Also in 2023, DuPont de Nemours Inc., the Chemours Company and Corteva Inc., settled a class action lawsuit and agreed to pay $1.2 billion for PFAS contamination in some drinking water systems. Separately, 3M agreed to pay $10.3 billion to provide funding for public water suppliers to test for PFAS and remove the chemicals.4

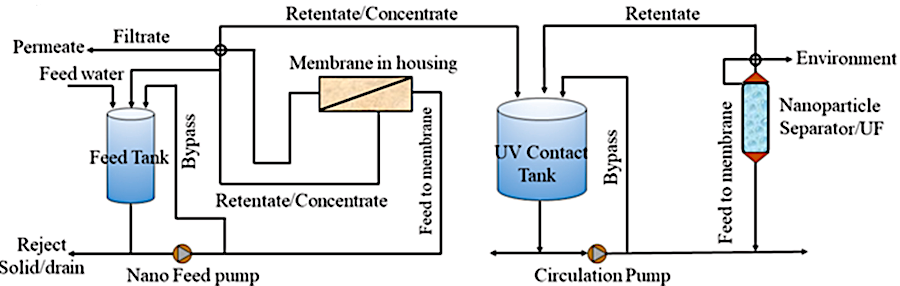

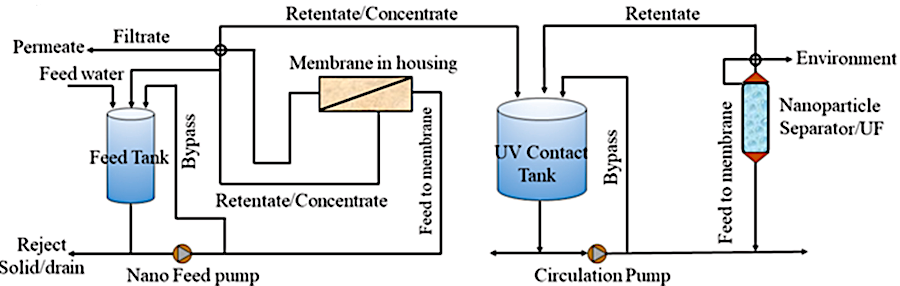

The technologies to remove PFAS from drinking water were still in early development stages. Options included activated carbon adsorption, ion exchange resins, and high-pressure membranes. Without a clear understanding of the investment required, 4,100–6,700 suppliers of public drinking water with high levels of PFAS had to speculate on the future costs to meet the proposed 4 parts per trillion standard.

The cost was justified by increasing protection of human health. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA):5

- - PFAS exposure over a long period of time can cause cancer and other illnesses that decrease quality of life or result in death

- - PFAS exposure during critical life stages such as pregnancy or early childhood can also result in adverse health impacts

PFAS molecules can be removed through hybrid membrane filtration and photocatalysis

Source: Journal of Hazardous Materials, PFAS and their substitutes in groundwater: Occurrence, transformation and remediation (June 15, 2021)

Drinking water is just one avenue for humans to ingest PFAS. In 2024, manufacturers of food packaging agreed voluntarily to stop using PFAS, which made hamburger wrappers and salad containers more oil-resistant. One university professor noted that the action by the manufacturers was significant in part because it limited PFAS exposure where consumers were unlikely to take action, because:6

- Nobody reads the wrapper of their hamburger to see if it has PFAS or not.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized its proposed rule for limiting per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances on April 10, 2024. It was the first rule to deal with a new drinking water contaminant since 1996.

The Federal agency estimated the lower limits would reduce PFAS exposure for approximately 100 million people. The new rule forced drinking water suppliers, including public utilities, to clean up waste that others had put into waterways. Federal action was directed towards reducing the risks to drinking water customers rather than eliminating the discharge of PFAS, or the cleanup of sies leaking "forever chemicals" into water supplies.

The Environmental Protection Agency did announced the availability of $1 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to fund implementation by the 6-10% of the 66,000 public drinking water systems that would have to take action. Technologies to reduce PFAS in drinking water included granular activated carbon, reverse osmosis, or ion exchange systems.7

In April 2024, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) were designated by the Environmental Protection Agency as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). That designation made major chemical manufacturers and users as potentially responsible for the costs of removing the two chemicals in Superfund cleanup projects.

Also included in the new determination of Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for "forever chemicals" was hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA), one of the GenX chemicals used to create non-stick coatings. The threshold was set at 10ppt in the final rule issued by the Environmental Protection Agency on April 10, 2024.

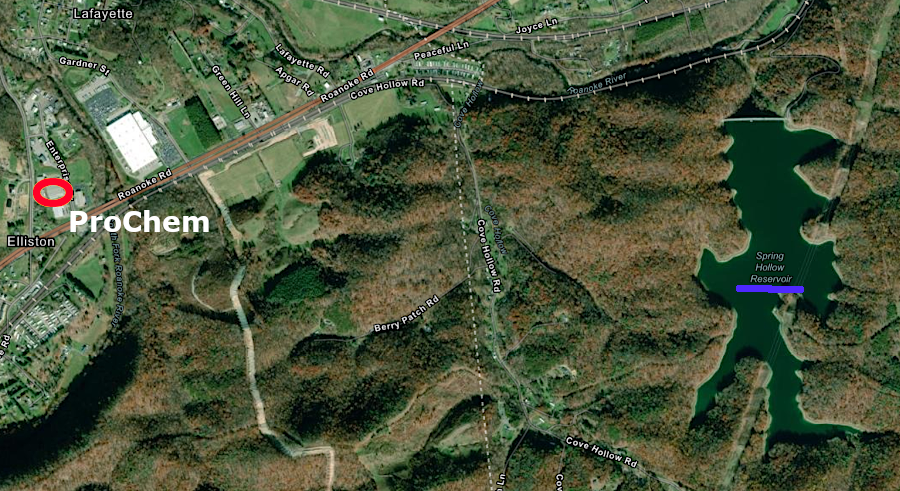

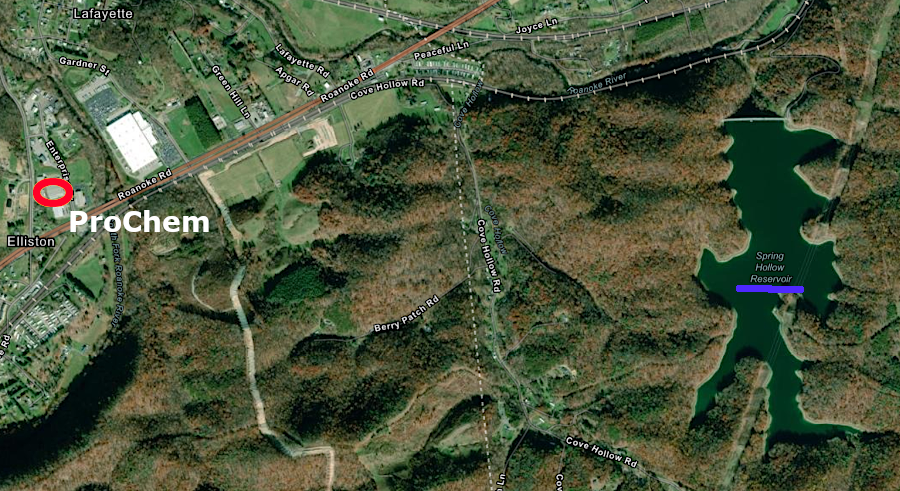

In 2020, a test of water from Spring Hollow Reservoir revealed 62ppt (parts per trillion) of GenX chemicals. That reservoir was a source of drinking water supplied by the Western Virginia Water Authority to several jurisdictions in the Roanoke Valley. The source was a ProChem plant in Elliston. It was cleaning industrial equipment from West Virginia, shipped to Elliston by Chemours. Wastewater from the facility was discharged into the South Fork of the Roanoke River. ProChem was not aware of the GenX chemicals, and the treatment process did not strip them out of the wastewater.

Once the contamination was identified, ProChem stopped processing the industrial equipment. To reduce the contamination in drinking water, the Western Virginia Water Authority implemented an activated carbon treatment process funded by Chemours. By January 2024, the level of GenX chemicals in the reservoir had dropped to 28 parts per trillion. By October 2024, the level was just 10 parts per trillion - which was the Maximum Contaminant Level finally set by the Environmental Protection Agency for hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA).8

water pumped into the Spring Hollow Reservoir from the South Fork of the Roanoke River included GenX chemicals from industrial cleaning at a plant in Elliston

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

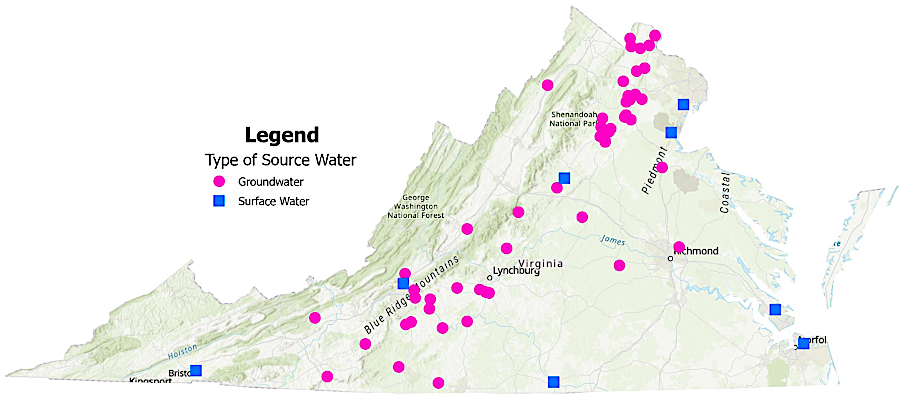

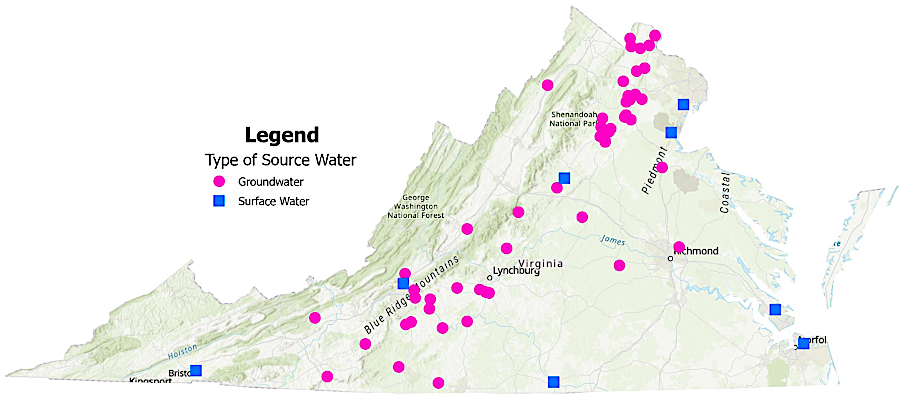

When the Virginia Department of Health tested a sample of the 2,860 public water systems in the state, over 6% (18 out of 274) exceeded the 4 parts per trillion threshold for PFAS.9

Costs to remove PFAS chemicals from drinking water supplies will be significant. Fairfax Water estimated it would have to spend $400 million to meet the Federal standards for PFAS.

The Fauquier County Water and Sanitation Authority calculated that PFAS levels exceeded the new Environmental Protection Agency thresholds in 35% of the 46 public drinking water wells. The wells producing the most water had the greatest contamination, so 50% of the county's public drinking water exceeded the threshold.

The authority, which had $14 million in annual revenue from water and sewer fees, estimated that PFAS removal costs would require a capital investment cost of over $40 million. The chair of the Board of Supervisors said:10

- Forty-four million dollars to treat an operation that only has $14 million in revenue over the course of a year? This is going to get political fast... I think there's going to be a lot of pressure on doing something here.

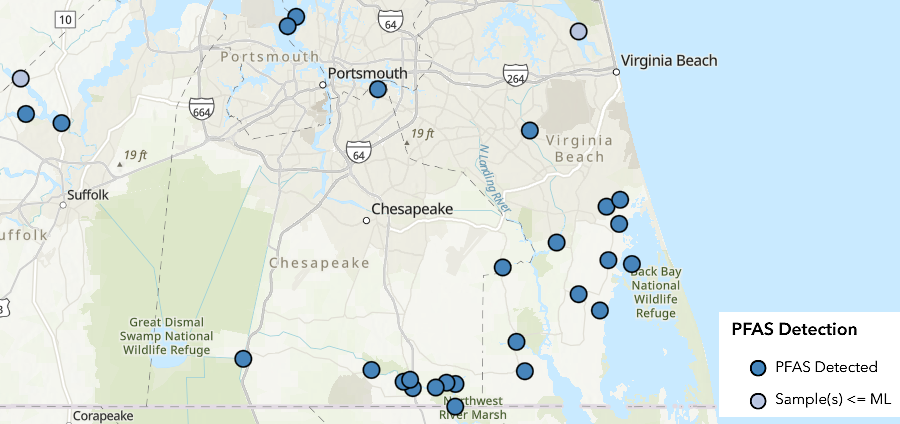

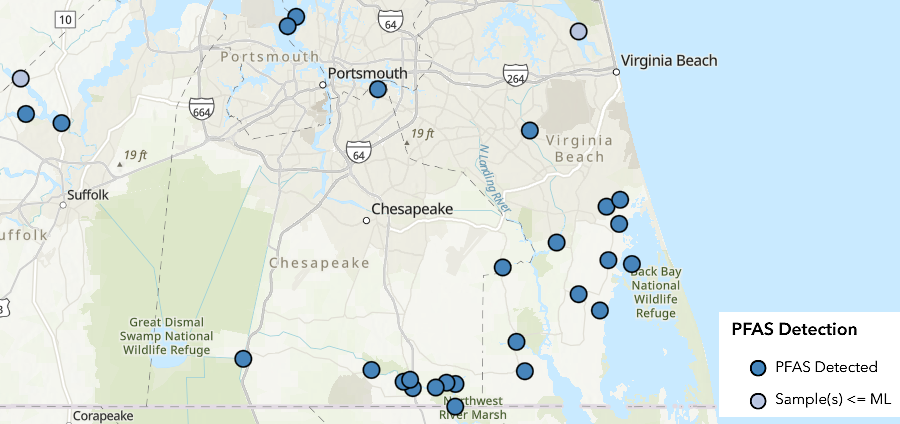

sampling in southeastern Virginia, with multiple military bases, detected PFAS in multiple locations

Source: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Statewide PFAS Sampling Results

The Virginia Department of Health (VDH) identified PFAS in drinking water samples. A separate state agency, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), had responsibility for managing the waste that leaves drinking water and wastewater treatment plants.

As the larger wastewater treatment systems began to test for PFAS in the treated effluent, nearly all (20 out of 21) found PFAS in the water they discharged into streams. All eight wastewater treatment plants that tested their sludge found some level of PFAS.

A 2025 study identified PFAS in 100% of well water samples. About 20% of Virginia residents rely upon groundwater for their drinking water.

By 2018, biosolids were being used to fertilize soils on 20% of agricultural lands across the United States. In 2022, Maine prohibited farmers from using sewage sludge on agricultural land in order to limit the potential of PFAS and other residues from entering the food chain. In Virginia, the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) chose to wait for Federal regulations.

In 2024, groups including the Potomac Riverkeeper and Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) filed a lawsuit to force the Environmental Protection Agency to limit PFAS levels in sewage sludge used as biosolids on farm fields. Watermen and oyster agricultural operations worried that the runoff from fields was contaminating seafood in local waters. EPA was requested to take action beyond simply identifying sludge reuse as a potential problem.

As one oyster grower commented:11

- There is no farm field that doesn't drain into our waterways.

After Maryland restricted use of sewage sludge from 22 wastewater treatment plants on farmland, Synagro planned to transport more of its biosolids from Maryland wastewater treatment plans across the Potomac River to apply on the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula in Virginia. As described in a New York Times article:12

- Virginia finds itself at the receiving end of a pattern that is emerging across the country as states scramble to address a growing farmland contamination crisis: States with weaker regulations are at risk of becoming dumping grounds for contaminated sludge.

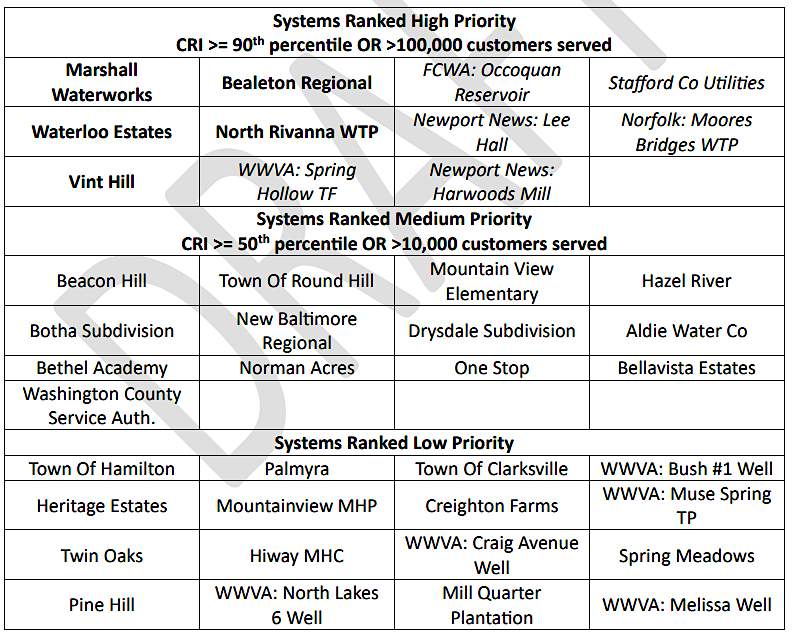

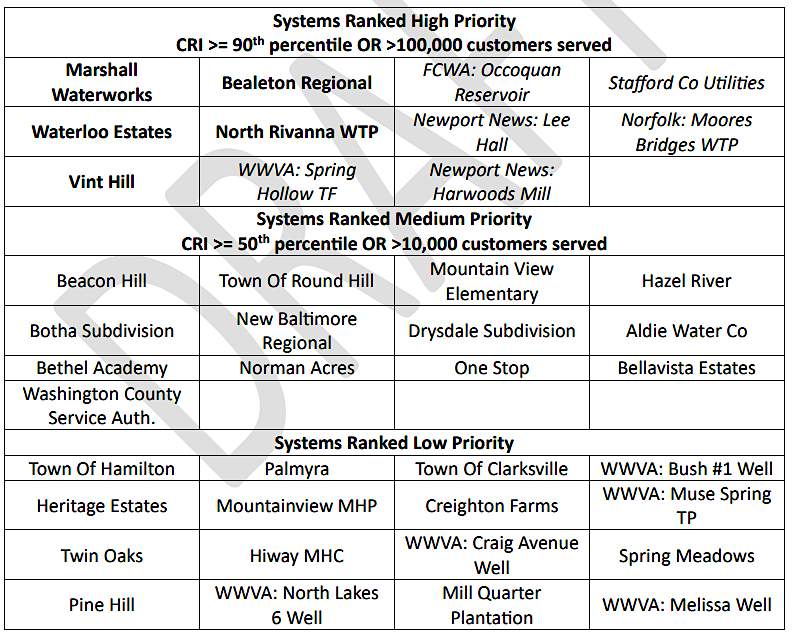

The General Assembly created the PFAS Expert Advisory Committee in its 2024 session. It was led by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), in consultation with the Virginia Department of Health (VDH). At its December 16, 2024 meeting the PFAS Expert Advisory Committee reviewed data from 274 waterworks that had been tested for PFAS from 2021-2023 and determined which systems would be priorities for completing 10-12 source assessments per year. Two factors shaped the prioritization, a Cumulative Risk Index and the number of customers drawing from the water systems.13

priorities for assessing the PFAS source were established in 2024 by the PFAS Expert Advisory Committee

Source: Virginia Town Hall, PFAS Expert Advisory Committee (PEAC) Meeting Minutes

from the December 16, 2024 Meeting

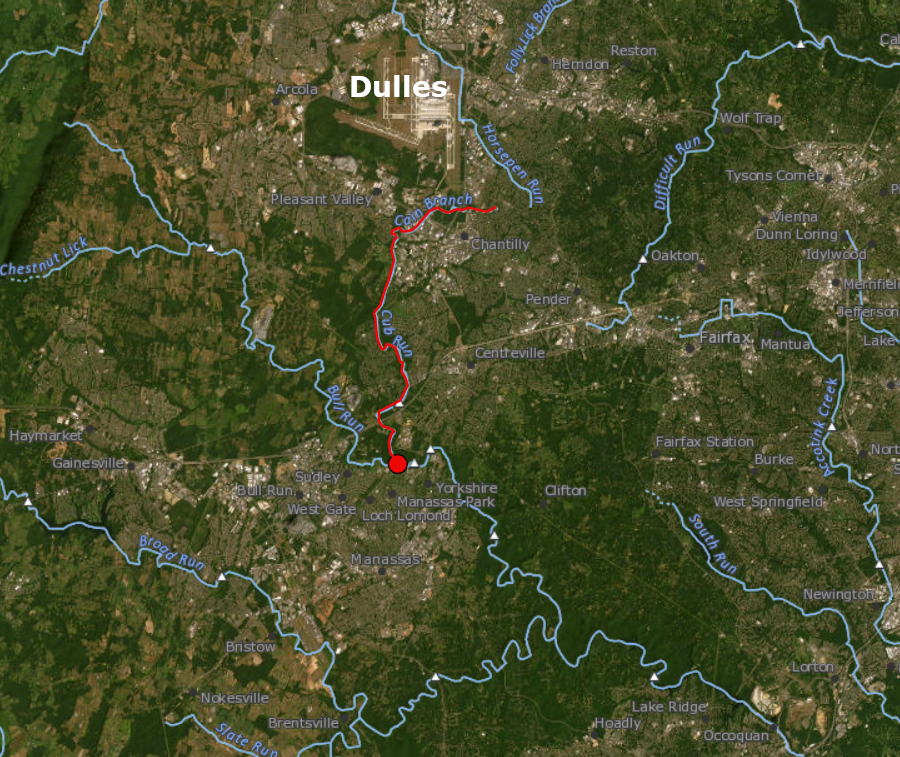

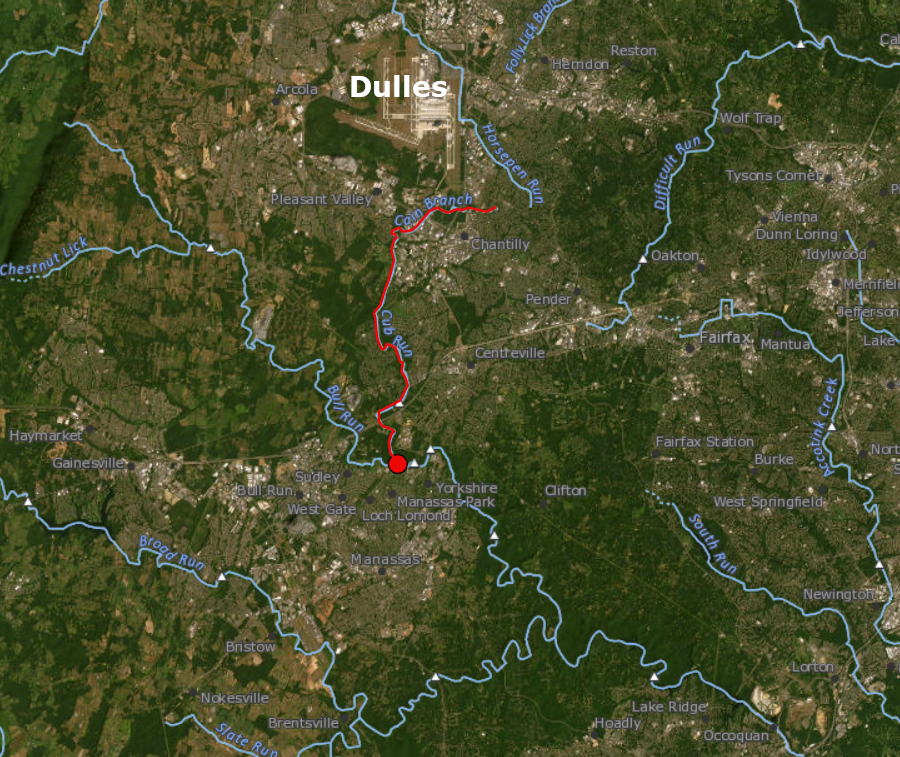

The 2025 General Assembly passed and Governor Youngkin signed HB2050. The bill required that the two major producers of PFAS sent downstream to the Occoquan Reservoir must keep their discharges below the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) threshold established by the Environmental Protection Agency, under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Unless the Federal government changes the Maximum Contaminant Level, the Micron computer chip manufacturing plant in Manassas will have to pretreat its wastewater discharge so the PFAS level is no higher than 4 parts per trillion. To retain its Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4) permit, HB2050 required that Dulles International Airport find a way to reduce PFAS to the same level in stormwater runoff flowing into Cub Run and then to the Occoquan Reservoir.

In 2025 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced plans to maintain the 4 parts per trillion limit for PFOA and PFOS, but to delay the deadline for two years from 2029 to 2031. The Trump Administration chose to drop the Biden Administration's regulation of a 10 parts per trillion limit for GenX, PFHxS, PFNA, and PFBS and start a new rule-making process.14

PFAS flows from Dulles International Airport to the Occoquan Reservoir via Cub Run

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

Links

- American Water Works Association (AWWA)

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Fairfax Water

- US Geological Survey (USGS)

- Virginia Conservation Network (VCN)

- Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ)

- Virginia Department of Health

drinking water systems with PFAS exceedances through July 2025

Source: Virginia Department of Health, PFAS Expert Advisory Committee Meeting VDH ODW PFAS Updates (August 18, 2025)

References

1. "Firefighting Foams: PFAS vs. Fluorine-Free Foams," US Fire Administration, May 25, 2023, https://www.usfa.fema.gov/blog/firefighting-foams-pfas-vs-fluorine-free-foams/; "Toxic 'forever chemicals' taint nearly half of U.S. tap water, study estimates," Washington Post, July 6, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/07/06/tap-water-forever-chemicals-pfas/; "Tap Water Study Detects PFAS 'Forever Chemicals' Across the US," US Geological Survey, July 5, 2023, https://www.usgs.gov/news/national-news-release/tap-water-study-detects-pfas-forever-chemicals-across-us; Kelly L. Smalling et al., "Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in United States tapwater: Comparison of underserved private-well and public-supply exposures and associated health implications," Environment International, Volume 178 (August 2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108033; "The most promising ways to destroy 'forever chemicals'," Washington Post, May 14, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2025/05/13/pfas-forever-chemicals-destroy-technology/ (last checked May 15, 2025)

2. "Toxic 'forever chemicals' taint nearly half of U.S. tap water, study estimates," Washington Post, July 6, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/07/06/tap-water-forever-chemicals-pfas/ (last checked February 27, 2024)

3. "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) - Proposed PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation," Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas (last checked February 27, 2024)

4. "Chemical giants reach $1.2B settlement over 'forever chemicals' in water," Washington Post, June 3, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/06/03/forever-chemicals-water-pfas-settlement/; "3M to pay $10.3 billion to settle lawsuits over 'forever chemicals' in drinking water," Washington Post, June 23, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/06/23/3m-forever-chemicals-lawsuit-settlement/ (last checked February 27, 2024)

5. "Reducing PFAS in Drinking Water with Treatment Technologies," Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), https://www.epa.gov/sciencematters/reducing-pfas-drinking-water-treatment-technologies; "Getting PFAS out of drinking water," Chemical and Engineering News, July 1, 2024, https://cen.acs.org/environment/persistent-pollutants/Getting-PFAS-drinking-water/102/i20; "Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation," Environmental Protection Agency, April 2024, https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/general-overview-webinar-presentation-final-pfas-ndpwr.pdf; "Getting PFAS out of drinking water," Chemical and Engineering News, July 1, 2024, https://cen.acs.org/environment/persistent-pollutants/Getting-PFAS-drinking-water/102/i20 (last checked September 29, 2024)

6. "PFAS chemicals to be phased out of food packaging. Here's how to avoid them," Washington Post, February 28, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2024/02/28/pfas-water-food-forever-chemicals-fda/ (last checked February 29, 2024)

7. "Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes First-Ever National Drinking Water Standard to Protect 100M People from PFAS Pollution," Environmental Protection Agency,. April 10, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/biden-harris-administration-finalizes-first-ever-national-drinking-water-standard; "In a first, EPA sets limit for 'forever chemicals' in drinking water," Washington Post, April 10, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2024/04/10/pfas-drinking-water-epa-safety/ (last checked September 29, 2024)

8. "For the first time, U.S. may force polluters to clean up these 'forever chemicals'," Washington Post, April 19, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2024/04/19/epa-rule-pfas-hazardous-water-contamination/; "Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Critical Rule to Clean up PFAS Contamination to Protect Public Health," Environmental Protection Agency, April 19, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/biden-harris-administration-finalizes-critical-rule-clean-pfas-contamination-protect; "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) - Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation," Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas; "Levels of 'forever chemical' decline in Spring Hollow reservoir," The Roanoke Times, November 3, 2024, https://roanoke.com/news/local/levels-of-forever-chemical-decline-in-spring-hollow-reservoir/article_48cad07c-97d5-11ef-8bdb-e7eae667fd3c.html (last checked November 26, 2024)

9. "PFAS clean up could cost Virginia public water systems millions for years to come," Virginia Mercury, January 9, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/01/09/pfas-clean-up-could-cost-virginia-public-water-systems-millions-for-years-to-come/ (last checked May 15, 2024)

10. "Forever chemical cleanup could cost Fauquier County $44 million," Fauquier Times, May 14, 2024, https://www.fauquier.com/news/forever-chemical-cleanup-could-cost-fauquier-county-44-million/article_7492b7f8-11cd-11ef-9c9a-af842e34e5b9.html; "Fairfax Water faces huge bill to comply with new EPA chemical removal mandate," FFXNOW, October 31, 2024, https://www.ffxnow.com/2024/10/31/fairfax-water-faces-huge-bill-to-comply-with-new-epa-chemical-removal-mandate/ (last checked November 11, 2024)

11. "Is sewage sludge laced with 'forever chemicals' contaminating Va. farmland? No one's testing it," Virginia Mercury, September 26, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/09/26/is-sewage-sludge-laced-with-forever-chemicals-contaminating-va-farmland-no-ones-testing-it/; "Sewage Sludge Fertilizer From Maryland? Virginians Say No Thanks," New York Times,

May 8, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/08/climate/sewage-sludge-fertilizer-virginia-maryland-pfas-forever-chemicals.html; "Most well water in Virginia likely has PFAS, researchers find," WVTF, December 16, 2025, https://www.wvtf.org/news/2025-12-16/most-well-water-in-virginia-likely-has-pfas-researchers-find (last checked December 17, 2025)

12. "Sewage Sludge Fertilizer From Maryland? Virginians Say No Thanks," New York Times,

May 8, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/08/climate/sewage-sludge-fertilizer-virginia-maryland-pfas-forever-chemicals.html (last checked May 9, 2025)

13. "PFAS Expert Advisory Committee (PEAC) Meeting Minutes from the December 16, 2024 Meeting" Virginia Town Hall, https://townhall.virginia.gov/l/GetFile.cfm?File=meeting\53\40905\Minutes_DEQ_40905_v1.pdf (last checked December 20, 2024)

14. "HB2050 - Occoquan Reservoir PFAS Reduction Program; established," Virginia General Assembly, 2025 General Session, https://lis.virginia.gov/bill-details/20251/HB2050; "Trump Administration to Uphold Some PFAS Limits but Eliminate Others," New York Times, May 14, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/14/climate/pfas-zeldin-trump-administration.html (last checked May 14, 2025)

Waste Management in Virginia

Virginia Places