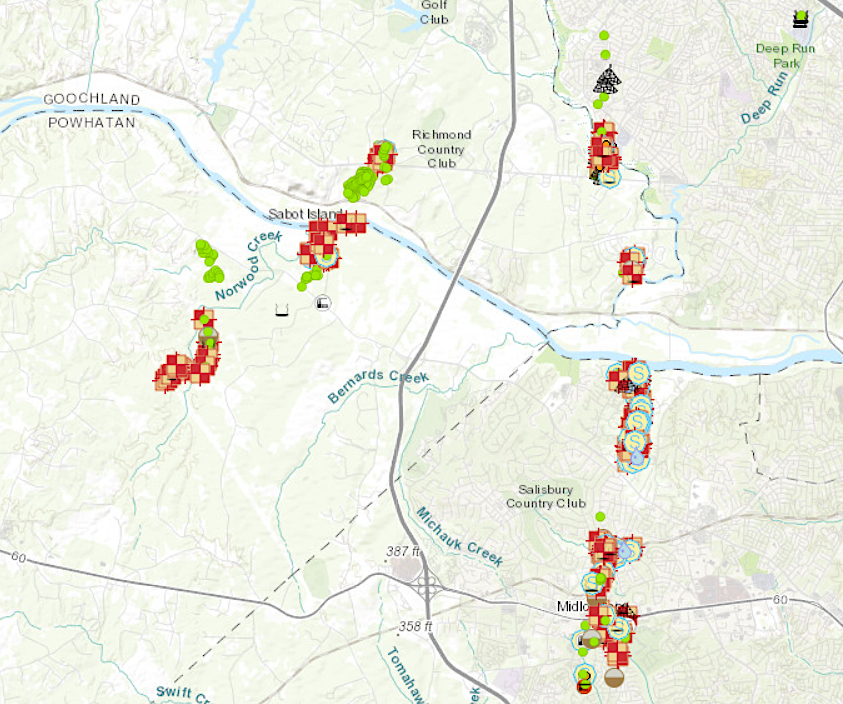

multiple coal mine sites west of Richmond are now in the Abandoned Mine Lands inventory

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Virginia Abandoned Coal Mine Feature Inventory

multiple coal mine sites west of Richmond are now in the Abandoned Mine Lands inventory

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Virginia Abandoned Coal Mine Feature Inventory

Miners have extracted mineral ore and coal in Virginia for three centuries. For most of that time, based on the fundamental concept of private property rights, there were no requirements to reclaim the land after mining ceased so it could be restored to some productive use. Land was abandoned once the valuable minerals were no longer profitable to extract.

Over time, sites of iron mining were covered again by forests. Pyrite, gold, and other "hard rock" mines also revegetated naturally, except where sulfur was exposed and the soil was too acidic for trees.

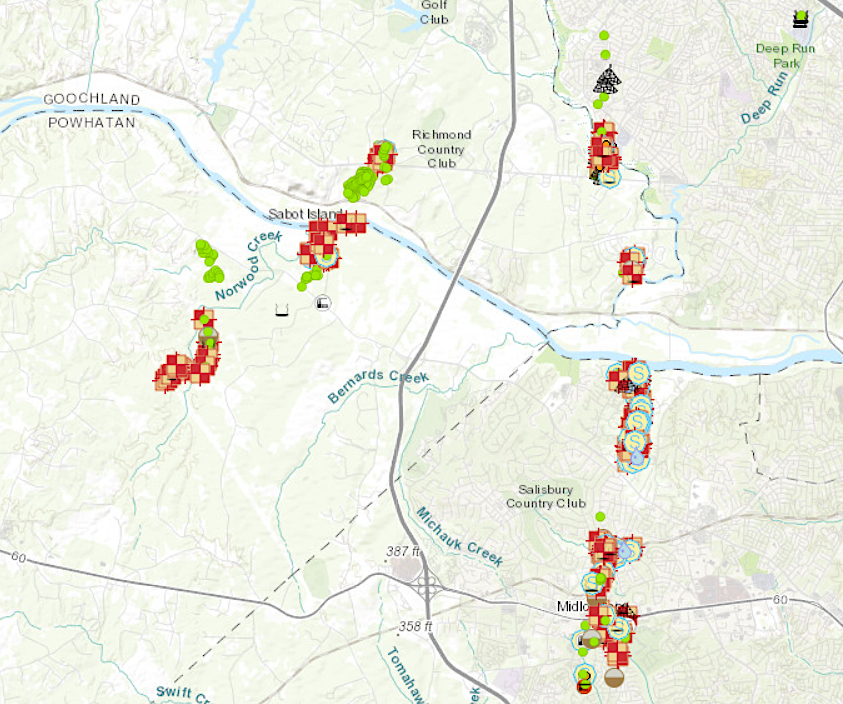

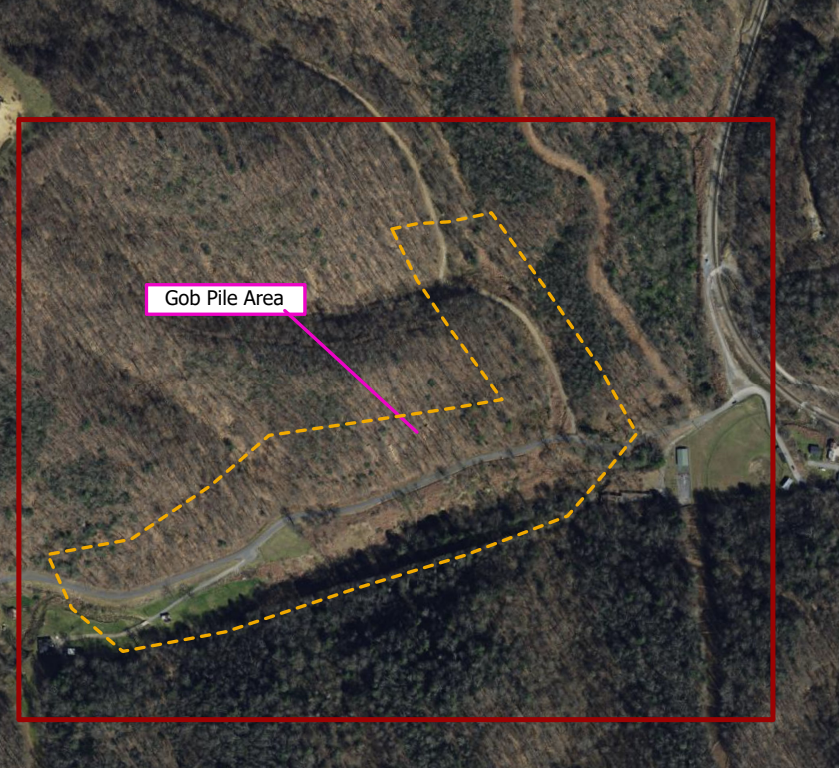

Surface impacts of underground coal mines were relatively minor, except gob piles of discarded waste rock and unprofitable coal accumulated at each tipple near the mine mouth. Strip mining of the surface, in contrast, created highly-visible scars. In addition to dramatic transformation of the surface during mountaintop removal, large impoundments were built on mountain streams to store waste rock where coal was washed before loading onto rail cars or trucks.

In 1972, a dam bust on Buffalo Creek in West Virginia. The resulting flood killed 125 people and generated a nationwide focus on the social and environmental impacts of coal mining. That led to passage by the US Congress in 1977 of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) and creation of what is now the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation (OSMRE) in the US Department of the Interior. It regulates coal mines only under the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Program; the Federal agency has no responsibility for other types of mines (such as abandoned gold mines).1

Taxes on new coal mining funded the Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund, created under Title IV of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. The funding has been used in Virginia to reclaim land with gob piles, abandoned shafts, and subsiding surfaces above underground tunnels. Landslides from waste piles, hazardous structures, dangerous highwalls, and acid mine drainage have also been corrected through Mined Land Repurposing projects using the Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund and Abandoned Mine Land Economic Revitalization Program (AMLER) funding.

In 2024, the Virginia Department of Energy awarded two AMLER grants. The town of Big Stone Gap received $2 million to upgrade recreational opportunities at the Big Cherry Reservoir. The town had decided to remove the gate and encourage visitors to enjoy the 250-acre artificial lake on Powell Mountain, which was the town's source of drinking water. Plans included opening the lake to swimming in hopes of stimulating economic development based on tourism. Big Stone Gap required another $1.4 million to complete the project, so in addition to the AMLER funding it sought grants from the Virginia Tobacco Commission and the Virginia Outdoor Foundation.

Big Stone Gap used a 2024 Abandoned Mine Land Economic Revitalization Program (AMLER) grant to upgrade recreation opportunities at Big Cherry Reservoir

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A plastics manufacturing plant in Clintwood received a $520,000 AMLER grant to expand its manufacturing capacity. As described by a member of the House of Delegates:2

Virginia seeks to return old coal waste dumps, such as the West Dante Gob Pile, to productive uses

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, West Dante Gob Pile

At the Route 23/58 intersection near Norton, mine reclamation led to the 180-acre Project Intersection development with space for four development sites. Local jurisdictions partnered to create the Lonesome Pine Regional Industrial Facilities Authority. They agreed that whatever jurisdiction in which a project was built would share the economic benefits among Dickenson, Lee, Scott, and Wise counties and the City of Norton.

Multiple funding sources were tapped to convert an old strip mine with a highwall into an industrial park. Earthlink moved into a new call center there in 2024, bringing jobs for 280 people.3

Project Intersection demonstrates how abandoned mine lands can be repurposed

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

A single company, Energy Transfer with its local Penn Virginia Operating Company, manages 675,000 acres of land in Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana. Its Powell River Project started in 1980 on 1,000 acres in Wise County at the Powell River Project Research and Education Center, with Virginia Tech as a research partner.

Source: VCE Wise County, Virtual Tour of the Powell River Project

Studies at the Powell River Project have shaped government regulations and private sector practices for mined land reclamation and post-mining management practices, including reforestation techniques. Because mining disrupted the soil, the successional sequence leading to a mixed hardwood forest would take up to one hundred or more years if left entirely to nature. Government regulators would not require a mining company to maintain a bond for that many years to ensure post-mining reclamation, so researchers are identifying fertilization and silvicultural practices that would be realistic to require as part of a bond.

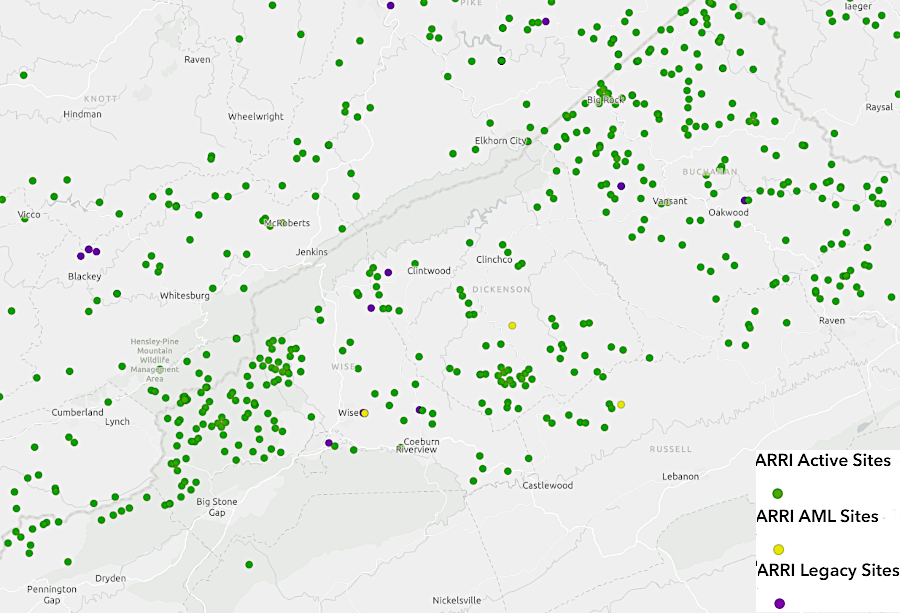

The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative champions the Forest Reclamation Approach (FRA). States have released their bonds on mining sites, declaring restoration was sufficient, but ended up with one million acres of unforested territory. The post-reclamation reforestation effort involves planting million of trees, but creating a new climax forest with a closed canopy is not the goal for all of that acreage.

there are Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative (ARRI) sites throughout Virginia's coal country

Source: Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation (OSMRE), ARRI FRA Sites

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources chose to reintroduce elk in Buchanan County because the old coal mining lands provided good habitat. Grass and forbs were readily available for food as disturbed areas slowly revegetated, creating a field-forest mosaic.

Because there were few farms on that part of the Appalachian Plateau, elk would not raid hayfields and cause conflicts with local residents. Instead, elk offered an opportunity to stimulate tourism-based business as the coal-based businesses disappeared.

The elk needed open grasslands for grazing and wooded areas for shelter. A homogenous, mature forest such as the vegetation at Shenandoah National Park was suitable for deer that browse on low branches, but would not support a population of elk. The Department of Wildlife Resources advertised elk reintroduction as a "two for one restoration:"4

"two for one restoration:" reclaimed coal mines in Buchanan County now support reintroduced elk

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In addition to restoring old coal lands for recreation opportunities, Virginia officials have proposed increasing the tax base in Southwest Virginia by locating major energy projects there. The Discovery, Education, Learning & Technology Accelerator (DELTA) Lab has sought to attract data centers, plus wind, solar, nuclear, battery and pumped storage, hydrogen and other emerging energy projects.

Abundant cheap land was a major incentive offered to draw energy-related developers to build on mined areas in Southwest Virginia. Governor Younkin promised that the first small modular reactor to be built in Virginia would be located in Southwest Virginia, until Dominion Energy revealed in 2024 that it preferred the North Anna Nuclear Power Plant site in Louisa County.

The Secretary of Commerce and Trade was clear in 2024 about the state's desire to use mined lands for energy-intensive data centers and new energy generation projects:5

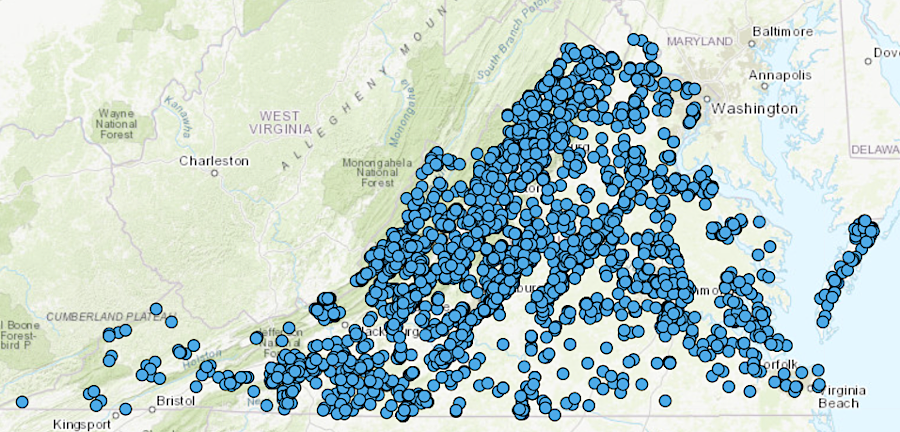

State and local government agencies and private landowners must fund reclamation of old gold mines, sand and gravel pits, and other abandoned mineral mined lands that could not tap into the coal-funded programs of the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation (OSMRE). The Virginia Department of Energy's non-coal orphaned land reclamation program is funded by the Mineral Reclamation Fund, which receives the interest on reclamation bonds held by the state. The Virginia Department of Energy issues permits and licenses for all commercial mineral mining operations in the state.

There are approximately 4,000 orphan mineral mines in Virginia. The first reclamation project was completed in 1981. By 2024, the state's Mineral Reclamation Fund had financed restoration of 160 acres of old mineral mines costing nearly $4 million.6

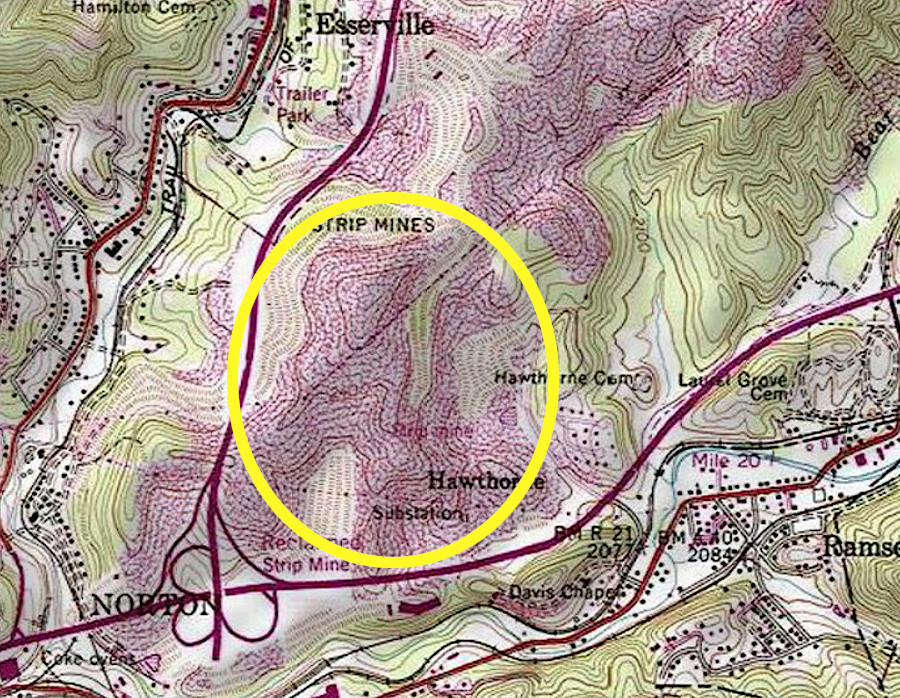

mineral (non-coal) mines, including quarries, are scattered across the state

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Mineral Mining

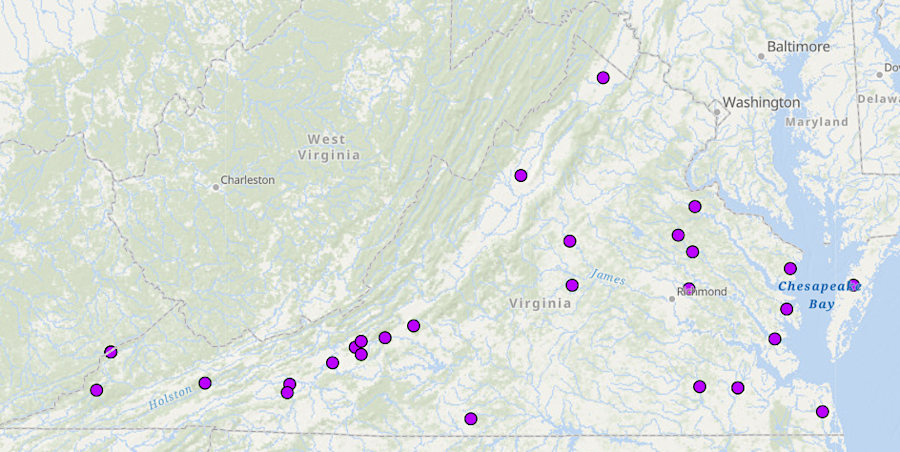

bonds are occasionally revoked when reclamation is not completed as planned

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Mineral Mining

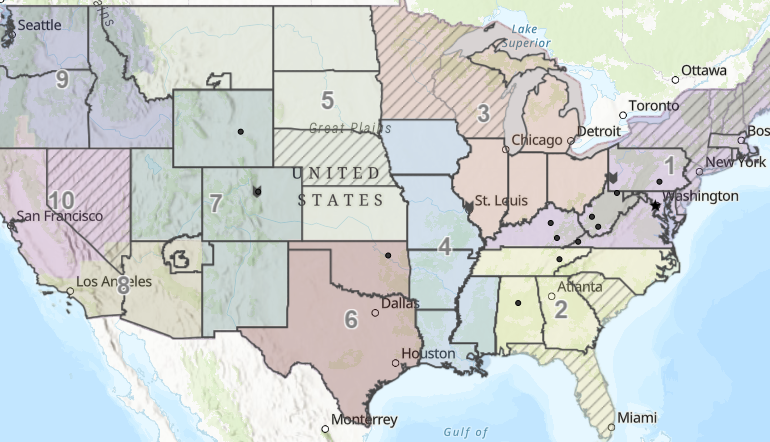

Virginia is in Region 1 of the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation, which is headquartered in Pennsylvania

Source: Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation (OSMRE), OSMRE Map

Source: Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation, 45 Years of SMCRA