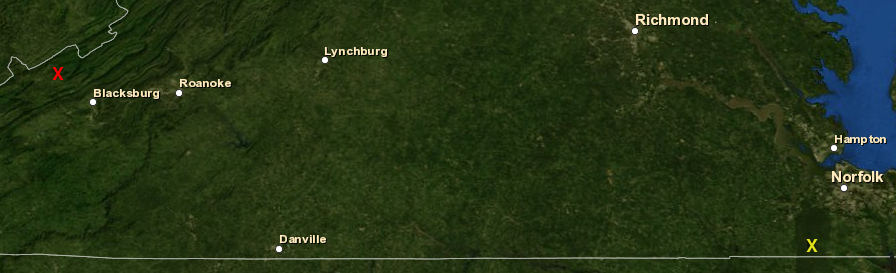

Mountain Lake (red X) is in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, while Lake Drummond (yellow X) is in the Coastal Plain

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (2013)

Mountain Lake (red X) is in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province, while Lake Drummond (yellow X) is in the Coastal Plain

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (2013)

There are only two natural lakes in Virginia, Lake Drummond (in Great Dismal Swamp) and Mountain Lake (in southwestern Virginia). Of the 50 states, only Maryland has no natural lakes.1

In the past, there were more lakes in Virginia. Roughly 300 million years of steady erosion has provided enough time for streams to etch their way into every Virginia valley. The streams have drained whatever lakes may have formed long ago in the last major orogeny, when the Appalachian Mountains were lifted up and topography transformed.

Since the last uplift when Africa and North America collided, climate has been wetter and new lakes may have formed. Sea levels have also been higher, flooding over the Coastal Plain all the way inland to roughly modern I-95. However, such lakes were short timers; erosion has carved new outlets to the Atlantic Ocean or Gulf of Mexico and those lakes are now meadows or bogs.

During that last Ice Age over the most recent 100,000 years, glaciers transformed the landscape and created the Great Lakes; Minnesota is the Land of Ten Thousand Lakes thanks to the glaciers. No ice sheets reached Virginia, however, and no new lakes were scoured out by the ice sheets south of Pennsylvania.

The two natural lakes present today appear to have been created by recent events. All other "lakes" in Virginia, including small ones such as Burke Lake in Fairfax County and large ones such as Smith Mountain Lake near Roanoke, are human-made reservoirs created by building dams and flooding valleys. Some watersheds - for example, the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, the Powell River, the Piankatank River, and the Blackwater River - have low volumes of impounded water today, but in the last 400 years dams have been constructed on nearly every Virginia stream.

Mill dams were built in the colonial era to power gristmills, grind limestone into plaster, and to saw wood. Most of the dams built for small gristmills have decayed and been washed away by storms. Almost all large lakes now visible in Virginia were made by humans damming streams to create reservoirs for hydropower, drinking water, flood control, or cooling water for power plants.

the first drinking water reservoir on the Occoquan River was created by Alexandria Water's 30' low dam in 1950

Source: Historic Prince William, Lower Occoquan Dam - #93

the 70' high dam was built by Alexandria Water in 1957 to enlarge its drinking water reservoir on the Occoquan River

Source: Historic Prince William, Upper Occoquan Dam - #88

Impoundments made for transportation, industrial, hydropower, or municipal drinking water purposes are not natural lakes. The canal system for the Rappahannock River envisioned converting the river upstream to Kelly's Ford into a series of slackwater pools, allowing boats to transport agricultural products to Fredericksburg. Dams along the James and Potomac rivers were also built, where it was cost-effective to increase water depth in the main river channel rather than build a canal parallel to the river.

the Reusens hydropower facility dams the James River, upstream of Lynchburg

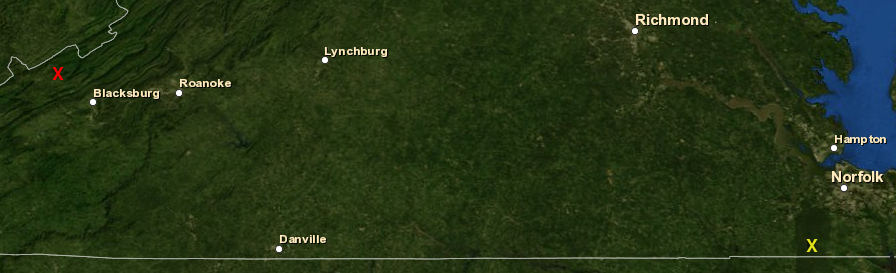

Some of Virginia's largest lakes were built for flood control and energy production, rather than for transportation. Lake Anna was constructed to provide cooling water for nuclear power plant reactors, though the two nuclear reactors in Surry County are cooled by water pulled directly from the James River.

In the Roanoke River watershed, Lake Gaston, Kerr Reservoir/Buggs Island Lake, Philpott Lake, and the combination of Smith Mountain Lake/Leesville Lake were created for hydropower. The largest lake in Virginia on the New River, Claytor Lake, was also built to generate electricity. There are tiny hydropower lakes as well. The tiny Little River, just downstream from Claytor Dam, also was blocked to generate one megawatt of electricity for the City of Radford.

Claytor Dam under construction around 1939

Source: Library of Virginia, A close-up view of a section of the new Claytor hydro electric power development, near Pulaski

There are thousands of small impoundments created as farm ponds for watering cattle/horses, but Virginia has few large lakes for irrigation. Virginia has a wet climate, unlike the Western United States. No Virginia dam projects were designed to provide irrigation for agriculture, so there are no dams built by the US Department of Reclamation such as Hoover Dam (which created Lake Mead near Las Vegas, Nevada). All Federal dams in Virginia were constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers, justified primarily for flood control or hydropower.

Lake Moomaw, behind Gathright Dam on the Jackson River, was built in part to mitigate the pollution coming from the Westvaco paper mill at Covington. The philosophy was that "dilution is the solution to pollution," and water stored behind the dam could be released during low-flow periods in the summer to mitigate the waste being put into the river downstream. A series of dams proposed on the Potomac River and its tributaries was justified as a means of diluting the sewage dumped into the river at Washington, DC. Those Potomac River dams were never constructed, and the Clean Water Act has forced polluters to reduce the waste dumped into the river rather than to rely upon dilution.

Lake Anna was built to cool a nuclear power plant (in circle)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online (2013)

Dams convert segments of free-flowing rivers into flatwater lakes. That changes the habitat, affecting what aquatic species will remain and which new species will occupy the altered niches. Dans block anadromous species, such as shad and eels, from reaching their former breeding grounds.

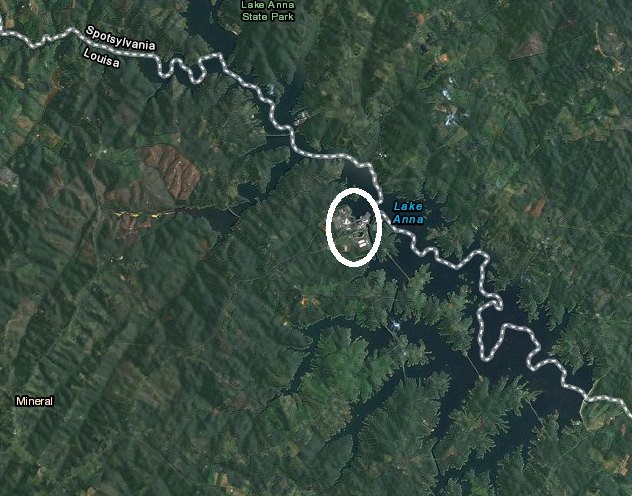

Dams also isolate fish populations. The Candy Darter (Etheostoma osburni) is listed as a Federally endangered species in the Kanawha River in West Virginia and its tributaries, including the New River in Virginia.

one remaining population of the Candy Darter is isolated from all others by Claytor Dam

Source: National Park Service, Protecting Our Native Candy Darter

Isolation has a significant impact on freshwater mussels which rely upon fish to transport their glochidia, the larval stage, as a short-term parasite. If fish can not swim past a dam, then upstream beds of freshwater mussels are not refreshed and gradually disappear.2

The change in the public's environmental consciousness in the 1960-70's has altered plans for new dams in Virginia. Transforming free-flowing rivers into flat-water reservoirs is no longer acceptable; the environmental impacts are now perceived as too significant. The Salem Church Dam, upstream from Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River, was the last proposal to block a major stretch of free-floating river and create a new lake.

The Corps proposed a dam on the Rappahannock River in 1933, and spent forty years advocating for a project at proposed site. The 196' high dam would have created a 23,000-acre reservoir, twice the size of Lake Anna, and would also have drowned the Rappahannock River up to Kelly's Ford. In 1974, the Corps of Engineers finally abandoned plans for the Salem Church Dam. Cancellation of that project, together with rejection of the dams on the Potomac, ended a 50-year period when large artificial lakes were built in Virginia.3

In the future, there will be no more Occoquan Reservoirs; no new drinking water reservoirs will be constructed on the main stem of rivers. Even drowning small creeks can become so controversial that the project must be abandoned, as demonstrated by the failure of the King William Reservoir project. The wetlands and historic resources along Cohoke Creek in King William County will not be drowned to supply drinking water to Newport News.

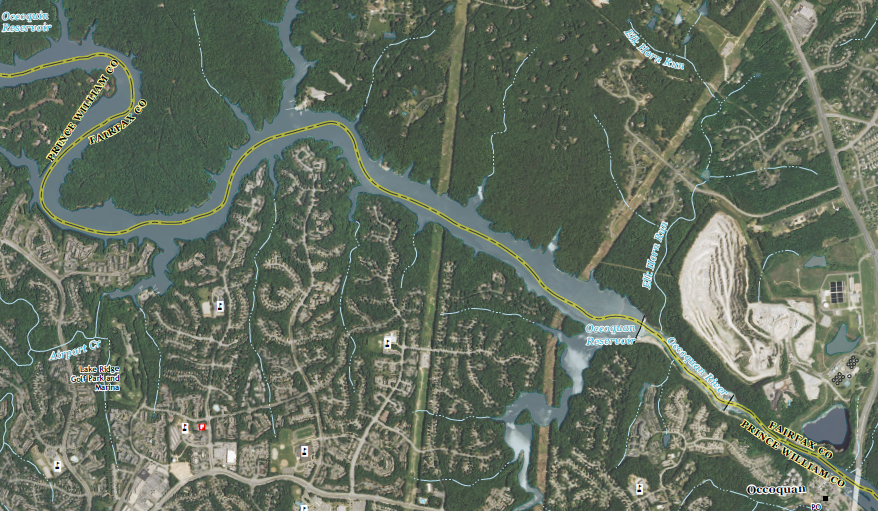

two dams on the Occoquan river create a drinking water reservoir for Northern Virginia, but also block anadromous shad and herring from their natural spawning habitat upstream

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Occoquan 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

The new model for urban areas seeking a reliable source of surface water (as opposed to drilling wells for groundwater) is to dam a small tributary. A dam on Motts Run created a small reservoir of drinking water for Fredericksburg, and Henrico County is building a dam across Cobbs Creek to supply its urbanizing suburbs.

Such small tributaries may lack adequate runoff to fill the reservoir regularly, but excess water can be pumped out of nearby rivers during winter runoff as an annual recharge source. Loudoun County has created the most dramatic example of how such runoff can be stored without creating a large lake, with plans to pump Potomac River water into old basalt quarries.

Instead of building new dams, public agencies are focused now on removing outdated dams that block fish migration, or are safety risks. Most of the small gristmill dams have been washed away by floods, and many small dams built before World War II have been breached.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries are removing larger dams (including Embrey Dam at Fredericksburg), or installing fishways to allow anadromous/catadromous fish to cross artificial barriers. Hollywood and Pipeline rapids on the James River in downtown Richmond are spicier because of old dams, but Riverton dam on the North Fork of the Shenandoah River and McGaheysville Dam on the South Fork of the Shenandoah River were life-threatening hazards before removal.

between 2011-2016, 10 dam removal projects increase access to fish habitat

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Fish Passage

Dam removal can be controversial. The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation revised dam safety requirements in 2012, and owners of many dams discovered that relicensing would require upgrading spillways or making other expensive repairs.

In 2012, the Lake Jackson Dam on the Occoquan River started to leak. That occurred a year after a 5.2 magnitude earthquake in Louisa County create enough motion to damage the Washington Monument, and the quake may have weakened the dam. Prince William County could have removed the 28' high dam completely, eliminating safety risks and restoring the natural flow of the river. However, eliminating Lake Jackson would have altered the character of the community surrounding it.

Local residents made clear that they preferred the recreational benefits associated with the lake, rather than a narrow stream. The county chose to spend close to $1 million to repair the dam, plus annual costs to maintain it - but declined to fund any dredging of the reservoir in order to improve boating and water skiing.4

in 2013, Prince William County committed roughly $1 million to repair the old hydropower dam at Lake Jackson, to preserve the lake amenity for adjacent homeowners

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Occoquan 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation is responsible for dam regulation. The primary concern is dam safety - if a dam breaks during storm event, how great is the risk to people or structures downstream.

In 2021, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation was aware of 3,662 dams in the state, and 2,663 were regulated by the agency. A dam is exempt if it:5

Smith Mountain Lake is an artificial reservoir created by a dam which blocks the natural flow of the Roanoke River

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridges and Culverts

In Lynchburg, Liberty University discovered that the donation of Ivy Lake in 2008 provided not only a 112-acre recreational site for students, but also a financial burden for dam repair. The spillway was not large enough to dispose of excess water if the area experienced the "probable maximum potential" rainfall. In that rare circumstance, water would flow over the top of the dam itself and erode the structure, leading to catastrophic failure and a flood downstream.

The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation classified the dam at Ivy Lake as high hazard, with 1,000 residents downstream at risk if the dam failed during a major storm. The engineer hired by Liberty University reported:6

in 2013, Liberty University decided to transfer ownership of Ivy Lake to adjacent homeowners rather than drain the lake or accept responsibility for perpetual dam maintenance

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Boonsboro 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

The university considered removing the dam, rather than paying up to $3 million for repairs. An alternative was for nearby homeowners in Bedford County to contribute $1 million, half the cost of repair, since they benefitted from the recreational opportunities of the lake and the water views/access added value to their private property.

There was little support from the homeowners for that option, or for simply breaching the dam and letting Ivy Creek flow without interruption. The road on the dam is the only way to drive to 129 houses, and the waterline for that neighborhood runs alongside the road.

In 2013, Liberty's engineers developed a lower-cost solution. The school agreed to pay $1 million to complete dam repairs as required by the state and then transfer ownership of the lake to nearby property owners. Those property owners would absorb responsibility for future dam maintenance, while university students would get access to use the lake through a permit/lease with a homeowners association. This would alter the situation since the 2008 donation, where the school paid all the costs for Ivy Lake while homeowners received substantial benefits for free.

Liberty University implemented a short-term dam safety measure in early 2014 and lowered the lake level by 20 feet. That limited recreational use and affected the local aesthetics; shoreline property owners had to remove their boats. Lowering the water level increased capacity to store runoff before water would low over the dam, reducing the potential for any breach.

Three different groups of homeowners ended up discussing different proposals with Liberty University, including some that would exclude university students from the lake. Liberty University's final offer was to loan $1 million for repairs, with repayment over the next 20 years.

The homeowners would end up owning the dam and lake, with responsibility for all future repairs. The university would retain rights to use the lake for recreational and boating use. The loan would be repaid by requiring all landowners to contribute an extra fee for 20 years. Property owners in the community who used Ivy Lake Road crossing the dam would pay about $300/year, those with property on the lake's shoreline would pay about $700 annually, and those who had lakefront access and also used the road would pay about $1,000/year.

Only 1/3 of the approximately 400 property owners living near Ivy Lake agreed to that deal. Liberty University then sued the landowners in 2016, asking a judge in Bedford County Circuit Court to force creation of a homeowners association and to impose the sale of the dam and lake. The university claimed that while it owned the lake and dam, it was a community amenity that made houses more valuable. The neighbors were:7

A university spokesperson justified the lawsuit, stating:8

Liberty University filed suit in 2016 to force property owners who used Ivy Lake Road, crossing the dam, to pay approximately $300/year for 20 years to cover dam repair costs - and for property owners with lakefront access to pay an additional $700/year

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

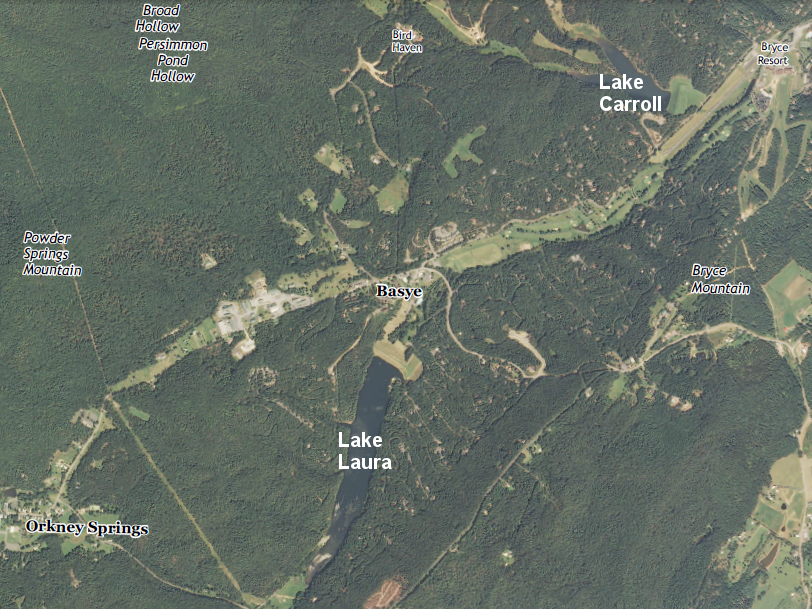

In 2014, homeowners near the Bryce Resort at Bayse took advantage of the draining of Lake Laura, which was required as part of the dam repair, to enhance water quality. The lake had excessive nutrients, and experienced algae blooms regularly.

With the support of the Friends of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, the Orkney Springs wastewater treatment plant upstream of the lake was closed, and a new pipe carried sewage to the Stoney Creek Sanitary District treatment plant downstream. The lake was dredged to remove much of the sediment that had accumulated since 1971. As a result, Lake Laura will present less risk to property owners downstream and will be a more-attractive amenity to the community.9

Lake Laura became a popular asset for residents near Bayse (Shenandoah County), and dam repair created an opportunity to reduce nutrients and to dredge sediments that had accumulated for the past 40 years

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Orkney Springs 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

One of the most unusual lakes in Virginia, Lake Tecumseh (also known as Brinsons Inlet Lake), was created when a 1789 hurricane created a new barrier of sand that altered the Atlantic Ocean shoreline. An open bay was quickly converted into a salt-water lake, which over time evolved into a 2-foot deep freshwater lake surrounded by wetlands. Because the lake was so shallow, its water was often turbid from bottom sediments stirred up by winds.

Lake Tecumseh in Virginia Beach

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Virginia Beach 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2013)

In the 1960's, the isolated lake was connected to Back Bay by a canal. That provided boat access to anglers and other recreationists, but the canal allowed sediment-rich water from Lake Tecumseh to degrade the quality of the northern portion of Back Bay. The lake would drain completely in the winter, and at other times when wind blew the water down the canal.

To block sediment from reaching Back Bay, in 2011 the US Fish and Wildlife Service built two low dams (weirs) where the Asheville Bridge Canal connected to Lake Tecumseh. For much of the year, the weirs now keep the water and its suspended sediment in the lake. At high water, the weirs are submerged and water flows freely between the lake and Back Bay. To maintain recreational access, the Federal agency built a boat trolley on rails, and provided a solar-powered winch to lift boats across the barrier. Lake Tecumseh is now a lake during low water, and an extension of Back Bay at high water.10

a solar-powered winch helps to portage boats across the weir at Lake Tecumseh, north of Sandbridge and Back Bay in Virginia Beach

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online; Will Smith, Lake Tecumseh Weir Project presentation at 2012 Back Bay Forum

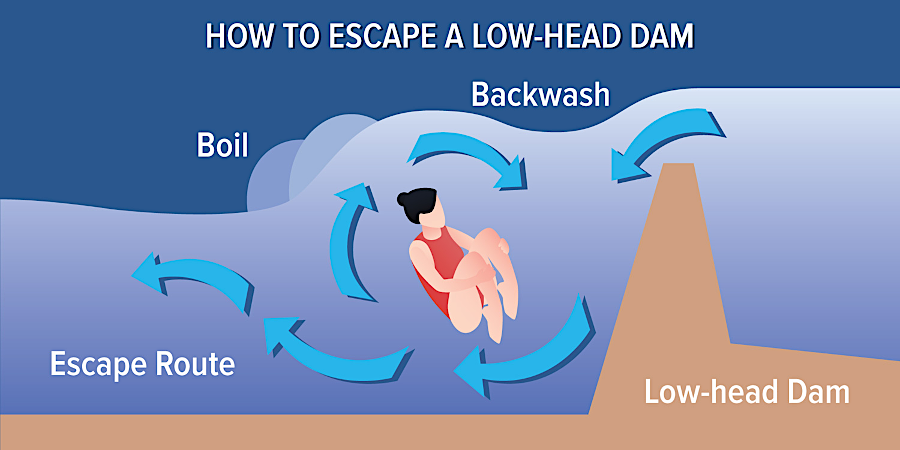

On the Dan River, the Brantley Steam Plant dam was removed in 2011 after a child drowned there in 2010. A canoeist drowned after going over the Long Mill dam at White Mill in 2020. That dam was 5 feet high and 1,144 feet long.

The Danville City Council debated the costs and benefits of removing the dam into 2022. That dam had been constructed in 1894 to provide water power for the textile mills. The city ended up as the owner, and in 2016 Danville Public Works recommended removal.

Long Mill Dam on the Dan River is 5-feet high and 1,144-feet long

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

a "hydraulic" current of recircling water downstream of dams can trap a person until they drown

Source: Indiana Department of Homeland Security, Low-Head Dams

The Long Mill dam created a section of flatwater on the Dan River than provided a scenic view. Local residents expressed various concerns, including whether the river's width would be reduced, coal ash behind the dam would wash downstream, and if the river channel would become just shallow rocks unsuitable for kayaking. One alternative to dam removal was to create a "rock ramp" on the downstream side of the dam, eliminating the hydraulic recirculation.

a rock ramp downstream of a low-head dam can eliminate the safety risk of the hydraulic current

Source: City of Danville, Long Mill Dam - Addressing the Concerns

Advocates for dam removal proposed creating a riverfront part with a pier into the river, and noted that maintenance costs would be eliminated and safety risks reduced by removal. In 2022, the Danville City Council finally decided in a 6-3 vote to remove the Long Mill Dam.11

Warren County supevisors were surprised to discover in 2022 that their predecessors had financed repairs to two private dams owned by the Shenandoah Acres subdivision, a community with 7,000 homes. The Property Owners of Shenandoah County Inc. repaired the dams that created two private lakes, Spring Lake and Lake of Clouds in 2007, raising the height and adding an emergency spillway at one dam. Funding came from a $600,000 loan from the county, which could borrow at a lower interest rate, and each year the Property Owners of Shenandoah County reimbursed the county for annual payment of principal and interest.

It was common for an economic development authority in a Virginia jurisdiction to arrange loans in order to attract a private corporation to locate in the jurisdiction. The Warren County loan to a homeowners association helped maintain property values and generated higher real estate tax revenue for the county. Supervisors who suggested the county should take ownership of the dams, since public money was used to repair them, were warned by county staff that the liability risks should be the responsibility of the private landowners.12

In 2025, the dam failed that was holding back Gardy's Millpond, at the headwaters of the Yeocomico River near the Westmoreland and Northumberland county border. That 450' long, 10' high dam had been built after 1985 Hurricane Bob breached the previous dam built for a gristmill, which had stopped grinding grain in 1948. The 75-acre pond was just four feet deep, with lily pads along the shoreline. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources managed a boat ramp and the pond as a recreational fishing resource.

The emergency spillway began eroding after heavy rains and the state agency declared the dam was at risk of "imminent failure." It was designated as a low hazard dam, so the greatest risk was to traffic on Route 617. That road passed over the dam, so the highway was closed.13

the dam at Gardy's Millpond failed in 2025

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Warren County financed dam repairs at Spring Lake and Lake of the Clouds, using public money for two private lakes

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

spillway at Beaverdam Reservoir under construction (Loudoun County)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

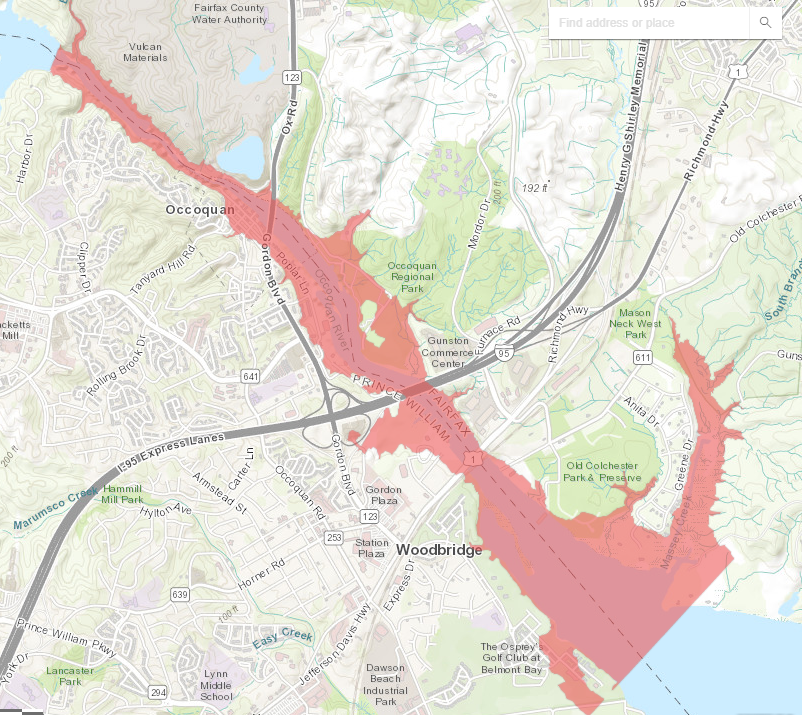

Fairfax County has defined the area which would be flooded after hypothetical collapse of the utility's two dams on the Occoquan River

Source: Fairfax Water, Occoquan Dam Siren