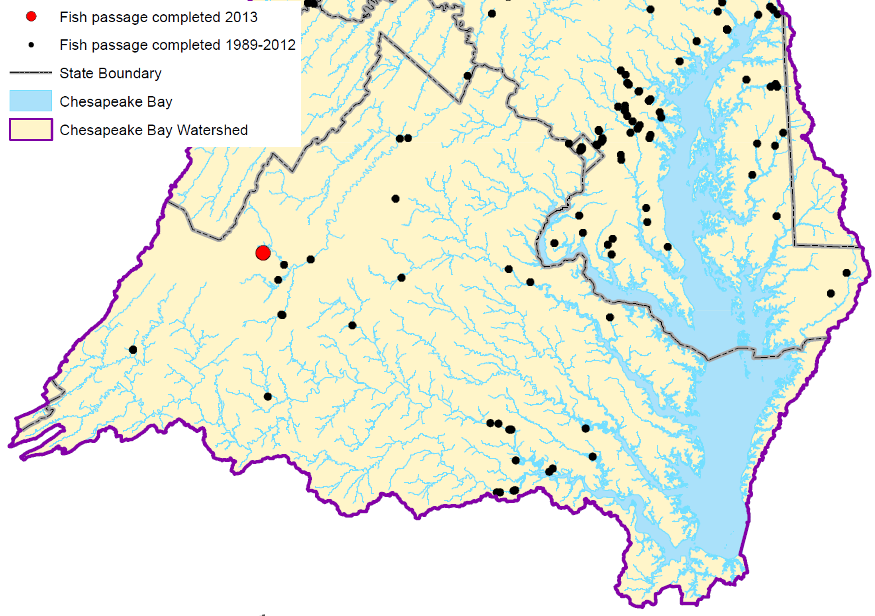

efforts to restore the Chesapeake Bay include fish passage projects on many tributaries

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Fish Passage Progress (2013)

efforts to restore the Chesapeake Bay include fish passage projects on many tributaries

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Fish Passage Progress (2013)

Virginia's rivers are connected to the Atlantic Ocean, and fish have evolved to take advantage of both saltwater and freshwater habitat. The American shad (Alosa sapidissima), hickory shad (Alosa mediocris), alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis), Atlantic sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrhynchus), striped bass (Morone saxatilis), and American eel (Anguilla rostrata) spend part of their life in freshwater Virginia rivers and the brackish Chesapeake Bay, and part of their life in the saltwater of the Atlantic Ocean.

The anadromous fish spawn in freshwater and spend their adult lives in the ocean. The catadromous eels operate in reverse; they spawn in the Sargasso Sea part of the Atlantic Ocean and spend their adult lives in freshwater. Eels can slither upstream over natural and human-built hazards more successfully than anadromous fish.

Native Americans took advantage of the migrating fish. Sturgeon, as much as 14' long, provided enough food to the earliest Virginia colonists that archeologists refer to the species as "the fish that saved Jamestown." John Smith reported "We had more Sturgeon, then could be devoured by Dog and Man," but the seasonal migration left the colonists without that food source during the Starving Time in the winter of 1609-10.1

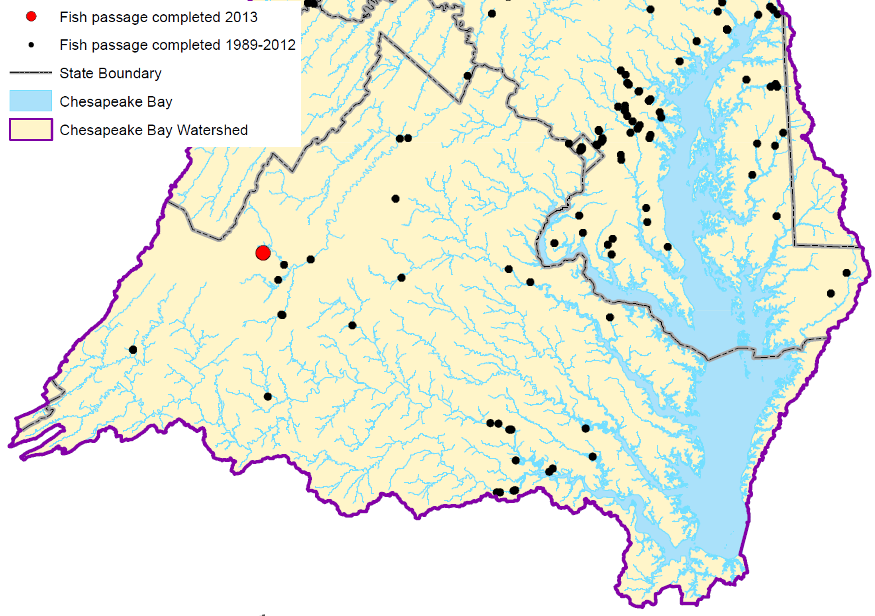

Shad move upstream when the water temperature reaches 65°, which typically occurs in Virginia during April. In 1778, George Washington's army at Valley Forge was starving and the British downstream were astute enough to block the springtime shad run - but the rebellious Americans managed to catch fish migrating up the Potomac and other rivers, and ship adequate protein to restore the army. Washington was knowledgeable regarding herring and shad migration; he had operated a commercial fishery at Mount Vernon since 1772.2

American shad spend their first summer in freshwater, then migrate to the Atlantic Ocean for three-six year before returning to spawn

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, American shad by Duane Raver

In the early 1800's, dams on the Fall Line were built to harness the waterpower for Virginia's mills and factories. Richmond became a major exporter of flour, after grinding the wheat with the energy of falling water. Complex systems of pulleys and cables stretched through multi-storied buildings to transfer the mechanical energy from the river to the millstones for grain, saws for lumber, and other equipment.

American shad were harvested by nets during their annual migrations upstream

Source: Harper's Monthly, The Shad and the Alewife (Volume LX, 1879-1880, p.853)

Five different major dams were built on the James River in Richmond, as the water dropped 100 feet in its 7-mile journey through the Fall "Zone." Additional dams were built throughout the Piedmont, where falling water offered energy to power wheels that spun grindstones to grind wheat/corn into flour.

One price for economic progress was the sacrifice of fish habitat. As an unintended side effect of gristmill construction, dams blocked anadromous fish from their upstream spawning habitat. Alewife, herring, shad, and eels were particularly affected, since they spawned in small tributaries up to the headwaters of streams draining into the Chesapeake Bay and Pamlico Sound.

The impact of building mill dams and blocking fish migration was no secret to colonial Virginians. Dr. Thomas Walker from Albemarle County recorded his frustration with mill dams in his 1750 journal of his initial trip through Cumberland Gap:3

removing the Power Dam restored habitat for a fish that anglers could not catch - the Roanoke logperch, a Federally-listed endangered species

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, an endangered Roanoke logperch

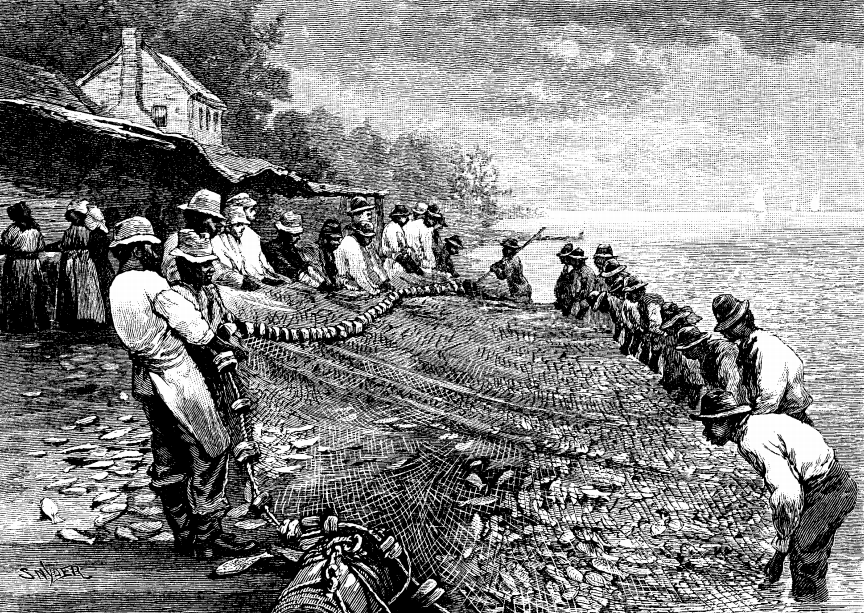

Construction of a fish ladder at Great Falls started in 1885 and the McDonald Fishway was finished in 1892. It was designed by Marshall McDonald, formerly the Fish Commissioner of Virginia. Construction of the water supply dam at Little Falls around 1900 blocked large fish from reaching Great Falls until a new fishway was completed at Little Falls. Some fish manage to get upstream and use the remains of the ladder at Olmstead Island.

However, some of the best fish ladders still block 70% of the fish from getting upstream past an obstruction.4

the McDonald Fishway, completed in 1892 at Great Falls, was intended to help fish expand into upstream habitat

Source: Smithsonian Institution, McDonald Fishway and McDonald Fishway

By the end of the 20th Century, Virginia was actively studying how to mitigate the impacts of development on the fish populations and the natural ecology of the Chesapeake tributaries in Virginia, and on the Roanoke River. Plans to restore the Chesapeake Bay included restoring the anadromous fish populations in the bay. Atlantic sturgeon did not migrate past the Fall Line, so recovery of that species depends upon a ban on harvest, protection of natural spawning beds from dredging, and creation of new spawning sites by dumping rock onto the bottom of the James River.

sturgeon populations have been dramatically reduced by overfishing, plus dredging and excessive siltation on spawning beds

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Habitat and Life Cycle of the Atlantic Sturgeon

Similarly, striped bass spawn downstream of the Fall Line, in the freshwater sections of Tidewater rivers (upstream of the salt wedge). Successful recovery of striped bass occurred in the 1990's, after Maryland, Virginia, and other states banned commercial and recreational fishing for the species within state waters and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration closed the Exclusive Economic Zone to any striped bass harvest. Populations recovered, helped in part by stocking of striped bass produced in hatcheries.

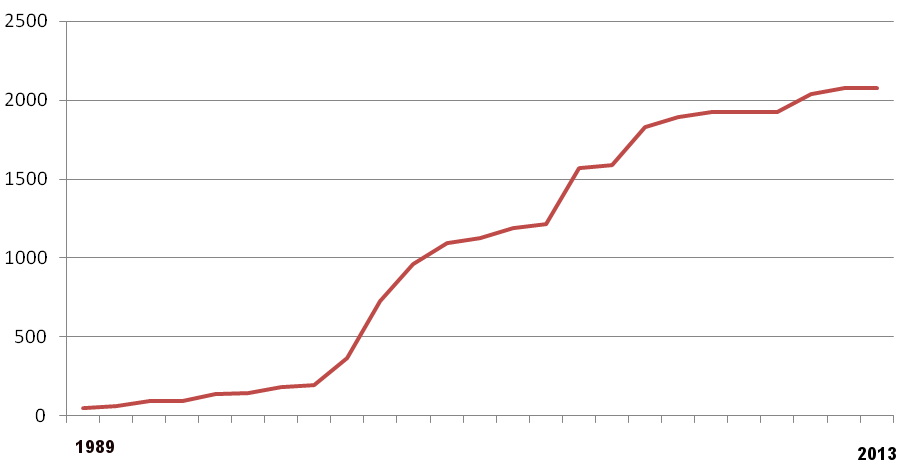

Restoration of other anadromous species required expanding the number of river miles available for spawning, by removing dams or providing fishways that allowed fish to swim past human-constructed barriers. The Fish Passage Work Group set a goal in 1987 to open up 1,357 miles of river, then doubled that goal to 2,807 total miles.

By 2013, 92% of the increased goal for the bay watershed had been achieved, by providing migrating fish a special channel to bypass dams or by completely removing dams. The 2014 revision of the Chesapeake Bay Agreement proposed adding an additional 1,000 river miles. That goal was achieved by 2016, so the partners agreed to open an additional 132 stream miles every two years. When the Chesapeake Bay Agreement was being updated in 2025, the draft proposed a new target of opening 150 miles every two years.

By 2023, the Chesapeake Bay Program claimed that 31,000 miles of stream habitat had been opened to fish passage since 1988.5

by 2013, over 90% of fish passage goals were achieved

Source: Chesapeake Bay Program, Reopening Fish Passage

Efforts to open fishways around the major dams on the James River at Richmond have been completed. Manchester and Brown's Island Dam, Belle Isle Dam, and Williams Island Dam no longer block passage.

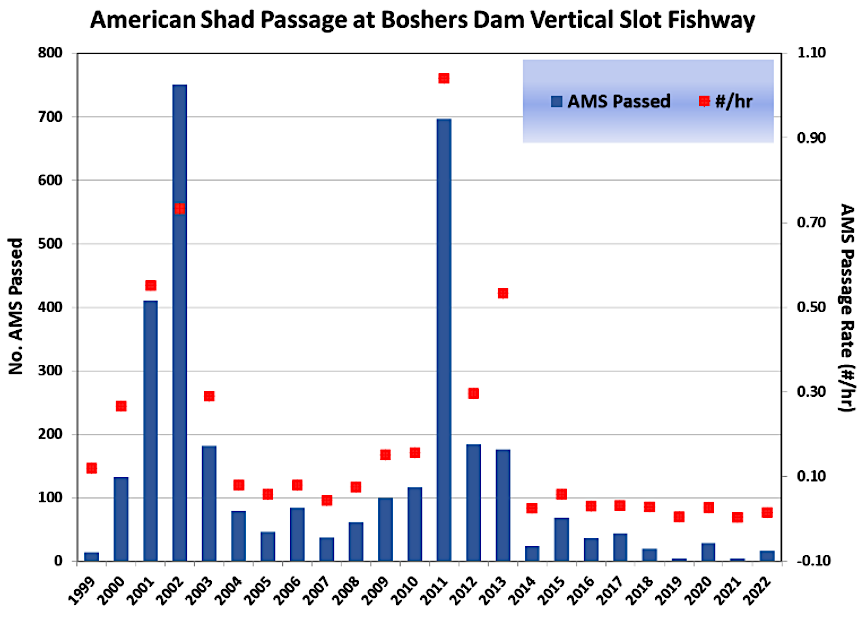

The last major dam on the James River near the Fall Line to get a fish bypass was Boshers Dam, at the I-295 bridge west of Richmond. The Boshers Dam Vertical Slot Fishway opened on March 1, 1999, It provided access to 137 miles of the James River upstream, plus 168 miles of tributaries, for the first time since 1823.

Earlier efforts since 1989 had breached fish-blocking barriers downstream at Manchester, Brown’s Island, Belle Isle, and Williams dams. The 10' high Bosher's Dam required a more complex solution, a fishway with smooth flowing water that fish would recognize as the route to use:6

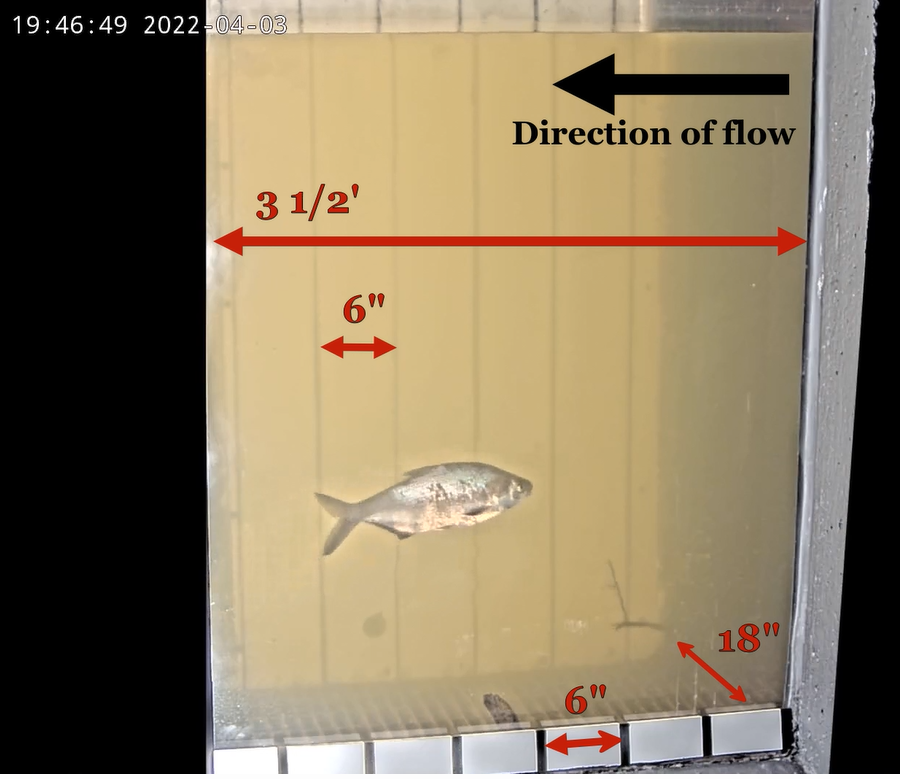

The state designed the fishway and its "attraction flow" to allow 500,000 shad to pass upstream annually. A window with 5" thick glass in the side of the fishway permits counting the migrating fish, and lights at night permit counting nocturnal migrants such as the American lamprey. A seasonal "fish cam" is operated, so people on the Internet also can watch the migration.

By 2015 only 200 shad were moving past Bosher's Dam each year. Other fish, including blueback herring, were crossing the dam, so biologists have considered the possibility that the design of the fishway is appropriate but most shad are being eating by blue catfish downstream or just not reaching Bosher's Dam for other reasons.

the fish passageway at Boshers Dam had limited success in getting American Shad upstream after 2011, perhaps because so few fish made it to the dam

Source: Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), A Framework for the Recovery of American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) in the James River, Virginia – November 2023 (Figure 9)

Biologists recognized that the shad population had collapsed, and the decline was the result of "death by a thousand cuts." In 2020 a fish survey found only six shad in the James River. As one observer noted:7

the viewing window at the Boshers Dam fish ladder is used to count fish and lamprey that swim upstream, and estimate their size

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Shad Cam: Through the Viewing Window

On James River tributaries, dams have been removed on the Tye River and the Rivanna River. The Quinn Dam on the Tye River, at the boundary between Amherst and Nelson county next to US 29, was removed in 2007. The Woolen Mills Dam was removed from the Rivanna River a week later.

Woolen Mills Dam on the Rivanna River, before removal in 2007

Source: Rivanna Conservation Alliance, Woolen Mills Dam Removal Designs, July 2004

Planning for the Quinn Dam removal required two years; negotiations took seven years before final removal of the Woolen Mills Dam. The structure on the Rivanna River had been in place for 178 years, and qualified for listing on the State and National Registers of Historic Sites. Eliminating those two dams opened up 37 miles of river habitat for migrating shad, herring, and eels.

Quinn Dam on Tye River in 2007, before removal

Source: Google Earth Pro

site of former Quinn Dam on Tye River in 2018

Source: Google Earth

Also on the Rivanna River, the Moores Creek Dam was removed in 2017. A year earlier, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, City of Charlottesville, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Rivanna Conservation Alliance, and landowners had all partnered to remove bridge abutments which blocked streamflow and created debris dams in the creekbed.

Moores Creek Dam on the Rivanna River

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Stream Restoration and Dam Removal on Moores Creek in Charlottesville, Virginia

Moores Creek on the Rivanna River, after dam removal in 2017

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Stream Restoration and Dam Removal on Moores Creek in Charlottesville, Virginia

Two hydropower dams at Lynchburg continue to block passage to historical spawning grounds that stretched as far as Eagle Rock. That habitat remains inaccessible due to Scotts Mill Dam, a 15-foot high barrier located at the downstream end of Daniel Island (upstream of Fifth Street Bridge).

Less than four miles further upstream is Reusens Dam, built in the 1830's as part of the James River and Kanawha Canal. Over the next 30 miles, there are five more dams, making a total of seven barriers in the 30 miles ending at Cushaw Dam below Glasgow.8

Scotts Mill Dam, upstream of Fifth Street Bridge in Lynchburg, is a 15-foot high barrier that blocks migrating fish

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Reusens Dam is one of the seven dams on 30 miles of the James River between Lynchburg and Snowden, Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the Tidewater portion of the James River, a "fishway" was constructed so herring could swim upstream despite a 10' high dam on Herring Creek that creates Lake Harrison for the Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery. Fishways and fish lifts have also been built or upgraded on the Chickahominy River and the Appomattox River.

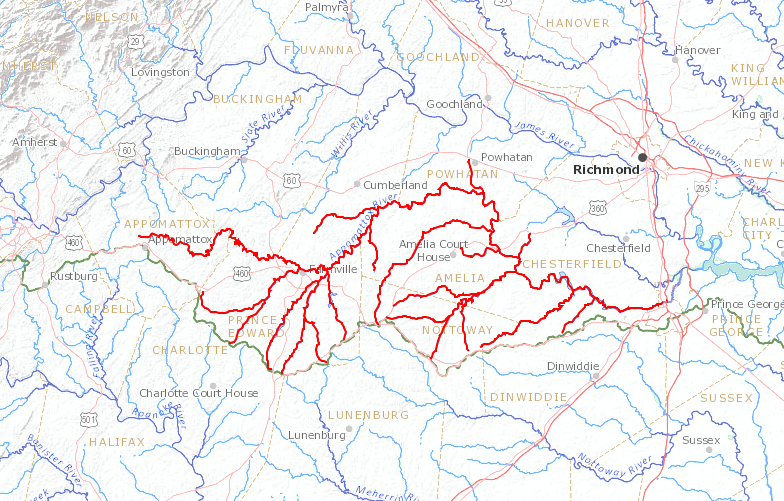

In 2014, the Harvell Dam on the Appomattox River was removed. That allowed anadromous fish to access another 127 miles of river upstream.

from Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries

before removal in 2014, Harvell Dam was a barrier to fish trying to swim upstream

Source: City of Colonial Heights, Harvell Dam

removing Harvell Dam opened 127 miles of habitat on the Appomattox River in Central Virginia

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

In 2010, Virginia Commonwealth University's Rice Rivers Center removed 25% of a 9-foot high, 800-foot long earthen dam built by a hunt club in 1927 to create Lake Charles. The dam improved habitat for waterfowl, but blocked fish passage up Kimages Creek. Storms partially breached the dam in 2007. After removal, bay anchovy, blueback herring and American eel migrated again into the creek.9

Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) removed the dam across Kimages Creek creating Lake Charles in 2010

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), Lake Charles Restoration Project- Timelapse

the former lakebed of Lake Charles in 2025

Source: Public Broadcasting System (PBS), Wetlands Restoration

Further upstream on the James River, another dam built in the 1960's still blocks the mouth of Curles Creek.

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) claimed it owned the submerged bottom of Curles Creek, while the riparian landowner asserted a Kings Grant claim and argued that the state had no authority to require a permit for use of the submerged land. In 2013, after a controversial debate, VMRC issued a permit that included stipulations for fish passage, the riparian landowner retained exclusive access to Curles Creek, and both sides avoided a lawsuit that might have affected state ownership of much submerged land in Tidewater.

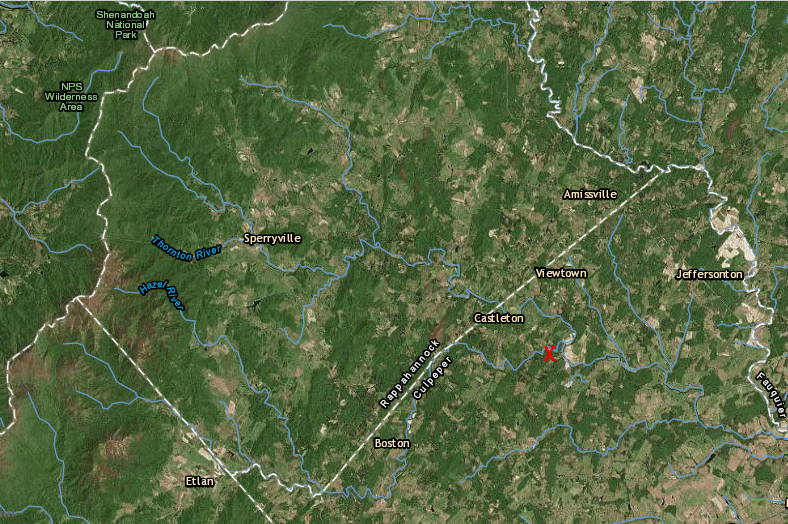

In 2012, a similar Kings Grant claim delayed removal of Monumental Mills Dam on the Hazel River, which is a tributary of the Rappahannock River. The dam was built in 1928 to provide hydroelectric power, but was no longer used for that purpose after a 1946 flood.

The US Army Corps of Engineers noted that removing that eight-foot high barrier would provide access to over 18 miles of habitat for "diadromous fish migration," meaning catadromous eels could swim out to the ocean to spawn while anadromous shad could swim upstream into fresh water tributaries for reproduction.

To resolve the ownership question, the Culpeper County Board of Supervisors supported the acquisition of the dam by the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. That occurred finally in 2016, and the state immediately planned the removal of the Monumental Mills Dam during the normal low-water period in October.10

over 18 miles of the Hazel River was blocked by Monumental Mills Dam, keeping catadromous eels from going out to sea to spawn and stopping anadromous shad from going upstream into fresh water

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

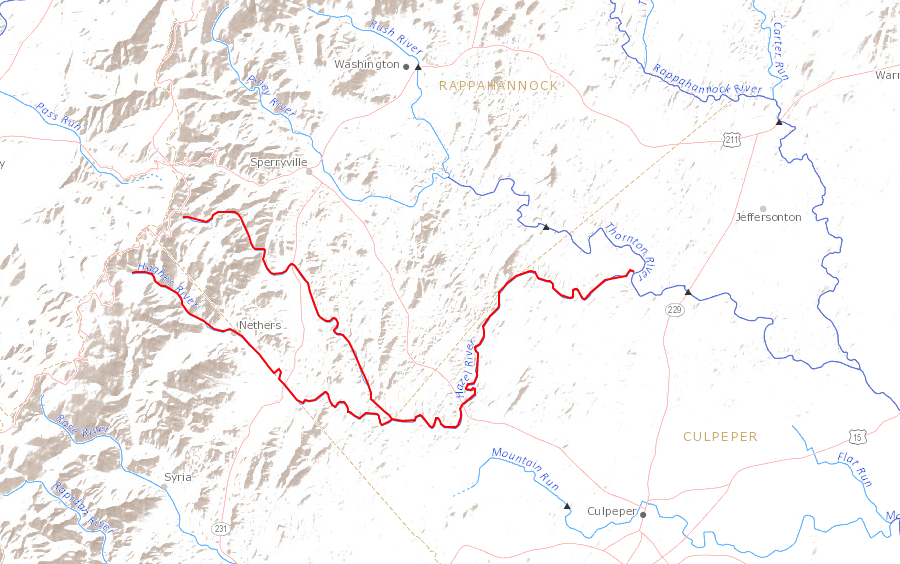

removing Monumental Mills Dam opened habitat on the Hazel River westward to the Blue Ridge

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

Monumental Mills Dam, before and after

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Let The Rivers Flow

Fish and eels could reach the Hazel River, at the base of the Blue Ridge, only because Embrey Dam at Fredericksburg was removed in 2004-2005. Embrey Dam had blocked the migration of shad and other anadromous fish upstream since 1910, but the US Army Corps of Engineers blew up the dam as a training exercise. Removal opened up 71 miles of spawning habitat on the mainstem Rappahannock River and 35 miles on the Rapidan River. Downstream of Fredericksburg, a 2005 reconstruction of a culvert under Route 601 in Stafford County removed barriers to fish passage on White Oak Run.11

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, American Rivers, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Friends of the Rappahannock, and the Piedmont Environmental Council partnered to create the Rapidan Fish Passage Project. It proposed to alter the 11-foot high, 200-foot long Rapidan Mill Dam at the town of Rapidan, perhaps with a fish ladder rather than removal of the dam.

The non-profit Center for Natural Capital acquired the dam and Rapidan Mill in 2019. The mill was the third at the site. A structure built in the mid-1700's was burned during the Civil War, and its replacement burned in 1950. The mill stored local grain in 10 concrete silos, each four stories tall, until it closed in the 1970's.

The barrier was the last significant stream-passage barrier remaining in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay watershed. Allowing fish passage beyond the dam would open 541 miles of upstream habitat, the "the last barrier in the Rappahannock River watershed to migratory fish attempting to reach their ancestral spawning grounds near the Blue Ridge Mountains."

In 2024, by which time the entity which owned the dam was called American Climate Partners (ACP), the dam removal project received a $7.9 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. After a year of planning, including hydrologic, geomorphic, and sediment analysis, actual removal of the Rapidan Mill Dam by 2027 was expected to cost $6.4 million.

Some local residents opposed the proposed dam removal and suggested alternatives such as adding a fish ladder, removing only a part of the dam, or restoring it. Nearby landowners expressed concerns at a 2025 meeting that public access to the dam site would spur trespass on private land.12

by 2024, the Rapidan Mill Dam was the last major barrier to fish passage on the Rapidan River

Source: Kip Teague, Rapidan Mill, Rapidan, Virginia

The Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries had anticipated a solution to the Rapidan Mill Dam barrier in 2013. The state agency, now called the Virginia Department of Wildlife, required that reconstruction of a 4-foot high dam at the town of Orange must include a fishway. As the Rapidan Fish Passage Project explored options at Rapidan Dam, a separate partnership of four organizations prepared to replace an old bridge further upstream on a tributary of the Rapidan River. That bridge, in Madison County, had two fish-blocking culverts. The Friends of the Rappahannock, Trout Unlimited, Ecosystem Services LLC, and the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources planned to open up 2.7 miles of habitat for brook trout by creating a "fish friendly crossing."13

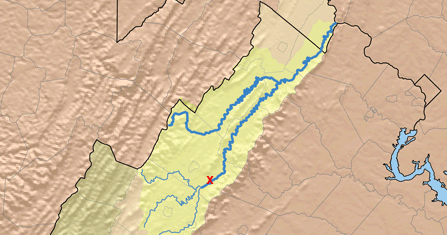

The Potomac River and its tributaries also provide spawning habitat to anadromous fish in the Chesapeake Bay. Allegheny Energy built eel passages at all of its hydroelectric dams on the Shenandoah River when they were relicensed. On the South Fork of the Shenandoah River, McGaheysville Dam was eliminated in 2004, and dams upstream of that location were also removed on the Middle and North rivers. Catadromous eels can swim all the way upstream to Staunton now.

removal of McGaheysville Dam (red X), plus Knightly Dam and Rockland Dam upstream, helps to open up the headwaters of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River to anadromous fish

Source: Karl Musser (on Wikipedia), Shenandoah River Watershed

Funding for fish passage financed the demolition of Riverton Dam in 2010, on the North Fork of the Shenandoah River at Front Royal. The dam had not been used to direct water to a hydropower plant since 1930, but the town approved demolition only after realizing that repairs to meet state safety mandates would cost $500-$1,000,000 and after a 9-year old was trapped behind the dam and drowned in an accident.14

Dams have been removed to improve habitat for local fish populations, not just for anadromous/catadromous species. To benefit local trout, in 2013 a 9-foot high dam was eliminated near Natural Chimneys. It blocked Mossy Creek, a tributary of the North River (which then flows into the South Fork of the Shenandoah River).

Mossy Creek had cut a bypass channel, which created excessive sediment in one of Virginia's best spring-fed trout streams. In addition to removing the dam, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and Trout Unlimited also modified the streambanks to minimize new erosion in the realigned stream channel.

a derelict dam at Mossy Creek limited trout movement, until it was removed in 2013

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Mossy Creek Dam Removal and Restoration, Augusta County, Virginia: Project Summary and Design Report (Figure 2)

Dam removal has had a positive impact; the anadromous fish populations are recovering. However, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission considers only the Potomac River to have a "sustainable" population of shad.

Starting in 2003, the US Fish and Wildlife Service raised shad fry at Harrison Lake National Fish Hatchery and released them in the released in the upper Rappahannock River. Eggs and milt for artificial rearing at the hatchery were collected from adult shad that had been caught in the Potomac River. Ideally, adults which had been imprinted to return to the Rappahannock River would have been the source, but there were too few above Embrey Dam to collect.

Monitoring since removal of the Embrey Dam in 2004 showed a steady increase in the number of fish returning each year to spawn, so artificial stocking in the Rappahannock River was stopped after 2014.15

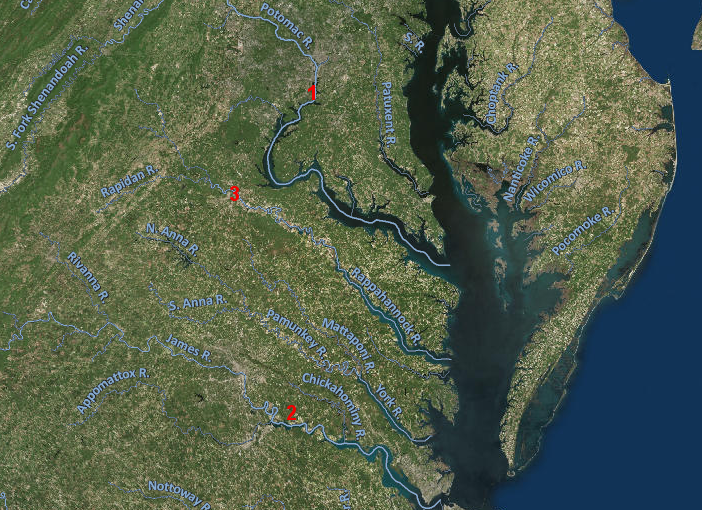

between 2003-14, adult shad were caught on the Potomac River (#1 on map), their fry were raised in a hatchery in the James River watershed (#2), and the young fish were used to restore the population on the Rappahannock River (#3)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Dam removals are intended to benefit more than just anadromous/catadromous species, and fish passage initiatives are not limited to just the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Two dams have been removed on the Pigg River, a tributary to the Roanoke River than flows into Leesville Lake.

Veterans Memorial Park Dam on Pigg River, before removal in 2013 to help restore Roanoke logperch

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Power Dam

The 25-foot high Power Dam blocked movement by smallmouth bass and the Roanoke logperch (an endangered species) on the Pigg River between 1915-2016. The dam had been abandoned but not removed in the 1950's.

removing the Power Dam on Pigg River

A wedge of sediment and logs accumulated behind it, and the Pigg River started to cut new channels around the embankments. There was the risk that in a hurricane or other large storm event, flooding could damage a road and the Rocky Mount Wastewater Treatment Plant below the dam. The dam was upstream of Leesville Lake, so the removal of the dam opened up a 70-mile stretch of habitat but did not alter the ability of fish to move beyond Leesville Dam.

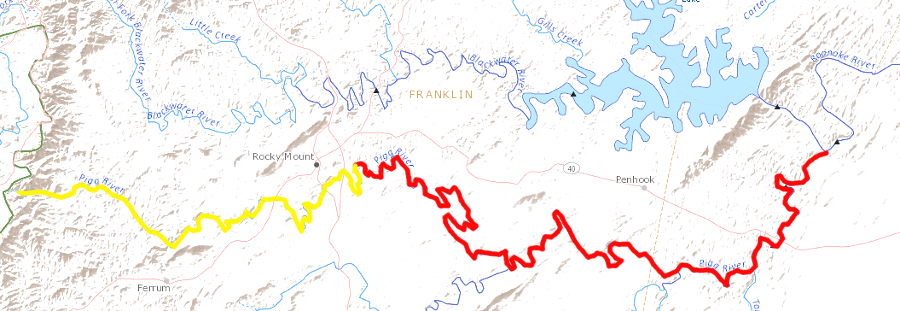

removing the Power Dam allowed fish to fully utilize 70 miles of the Pigg River, upstream from the old dam site to the Blue Ridge (yellow) and downstream to Leesville Lake (red)

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Streamer

The utility company that owned the dam transferred the structure to the non-profit Friends of the Rivers of Virginia and helped fund the removal. Disposing of the hazard minimized potential future costs from storm damages.

One the dam was removed, the wedge of sediment behind the dam was allowed to erode naturally. The result was a series of braided channels and new wetlands, but over time the river was expected to establish a new channel to carry most of its flow.16

removing the Power Dam in Franklin County, with unused powerhouse on the edge

Source: Friends of the Rivers of Virginia, Pigg River Restoration Project

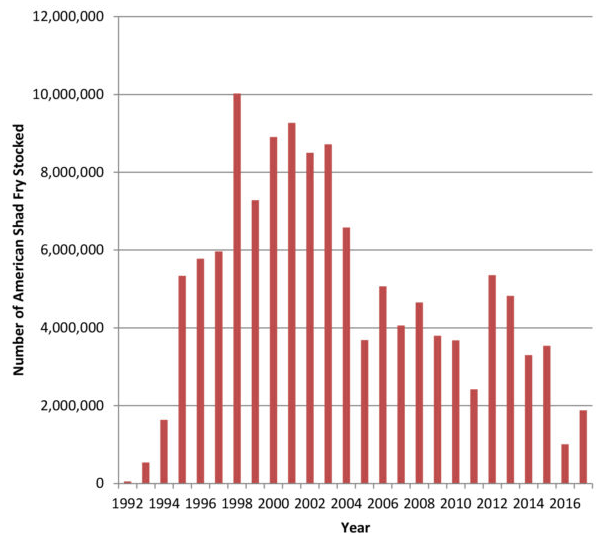

Despite the construction of the "fishway" at Bosher's Dam, removal of other dams, and a restocking of shad in the James River watershed since 1992, the population failed to recover. In 2017, the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) announced that it would stop restocking shad in the watershed. The state agency also abandoned restocking of the Rappahannock River in 2014, after a decade of effort to rebuild that population.

Shad had been raised at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Harrison Lake Fish Hatchery from eggs extracted from mature adults on the Pamunkey and Potomac rivers. The decline in returning adults, and the loss of funding from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission since 2008, had limited the ability to raise enough shad to meet restocking goals. The state concluded that fishing pressure in the Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay was having an impact too great to offset by continued investment in raising and releasing young shad:17

in 2017, after 25 years, state wildlife officials abandoned efforts to restock shad in the James River

Source: Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, On the Road to Recovery: American Shad Restoration

In 2022, a partnership of Trout Unlimited, Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, and US Forest Service removed the dam blocking Wilson Creek at Douthat State Park in Bath County. The dam had been built originally to provide water to cabins at the park. The park later drilled wells, and a flood in 1985 ended the use of the dam for supplying surface water to nearby residences.

The no-longer-needed dam continued to block trout from migrating in the creek. The stream channel was altered as well. Upstream, gravel accumulated above the dam. Below it, the sediment-free water flowing over the dam had enough energy to scour a deeper channel and remove the gravels needed for spawning.

Wilson Creek was on the list of "priority waters" which Trout Unlimited identified in Virginia. Removal of the dam was completed within the stream channel, but on the ends portions of the structure were left as histocic remnants.18

Wilson Creek Dam at Douthat State Park was removed in 2022

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Let The Rivers Flow

By 2023, over 31,000 miles of fish passage had been opened in the Chesapeake Bay watershed since 1988. However, populations of American shad, striped bass, and herring were still below target levels.19

In 2024, Ashland Mill Dam on the South Anna River became the first fish-blocking dam to be removed in order to obtain mitigation credits used to offset the environmental impacts of other projects. Davey Mitigation funded the removal in anticipation of selling credits to mitigate stream damage and create ecological benefits by other construction projects in the York River basin.

At the time of removal, the Nature Conservancy ranked removal of the Ashland Mill Dam as the best opportunity to improve fish passage in the Chesapeake Bay region. Wooden dams built at the site in the 1800's had been replaced in 1913 by the 210-foot long, 13-foot high concrete dam that blocked upstream passage of shad, herring, striped bass and sea lamprey. The project manager for Davey Mitigation commented on the unique funding for the project:20

Source: Randolph-Macon College, Removing Ashland Mill Dam: Randolph-Macon College Environmental Studies research

the Ashland Mill Dam, 13' high, blocked the South Anna River until 2024

Source: Randolph-Macon College, Removing Ashland Mill Dam: Randolph-Macon College Environmental Studies research; ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Baber's Mill Dam on Rock Island Creek in Buckingham County was removed in 2025. That ix-foot high dam, which provided waterpower for a saw and grist mill, had been blocking fish passage since 1827. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources had stocked James spinymussel above the dam before discovering it; the dam had not been recorded in various databases. Biologists found shells of dead spinymussels in the pool behind the dam, showing that the dam was a death trap for that endangered species.

Weyerhaeuser, the timber company which owned the Baber's Mill Dam, partnered with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, and a private foundation to document and then remove the historic dam in 2024. As described by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources:21

Source: Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, Unlocking the Waters: Baber's Mill Dam Removal Benefits Fish, Mussels, and More!

Even small barriers to fish passage are being removed. Until 2022, a culvert on the abandoned Nobles Road in Prince George's County blocked fish from migrating up Flowerdew Hundred Creek. The culvert had, in the past, become clogged with debris and blocked two miles of river herring spawning habitat. The fish passage coordinator for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources identified the benefit of such a small ($50,000) project:22

drainage culverts at road crossings can be as effective as dams in blocking aquatic species passage

Source: Wikipedia, Culvert

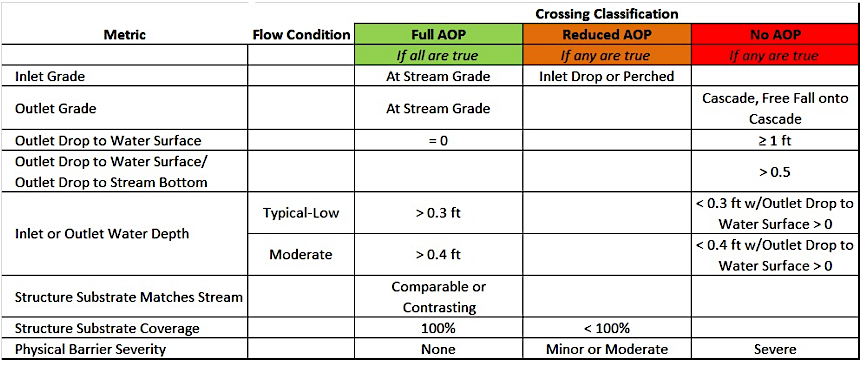

A 2016 assessment identified 3,000 culverts on roads crossing anadromous fish spawning tributaries in the lower James River Watershed. Of the total, 319 sites that appeared to limit access to suitable habitat were prioritized for closer review and assigned individual culvert scores using the North Atlantic Aquatic Connectivity Collaborative (NAACC) as offering Full AOP (Aquatic Organism Passage), Partial AOP, and No AOP.

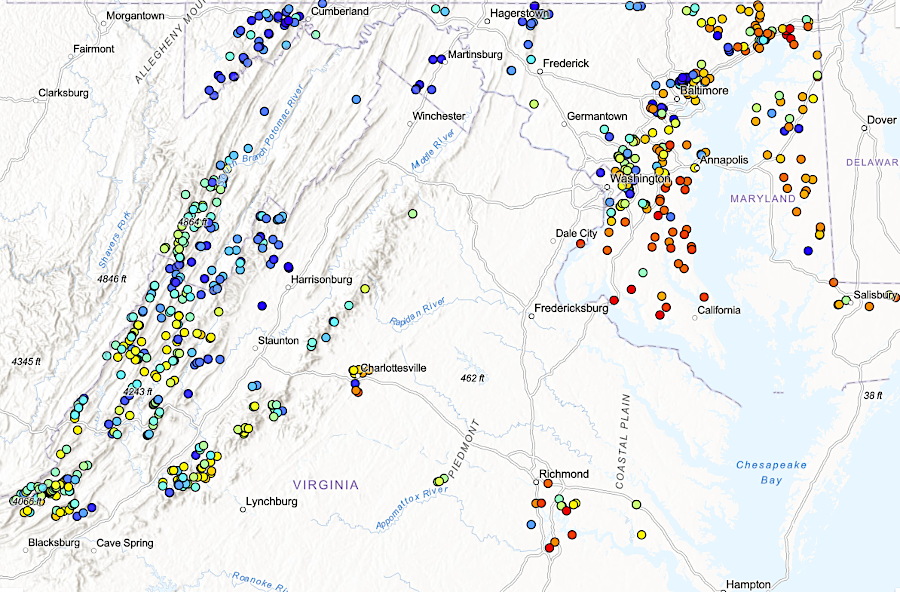

culverts blocking diadromous fish passage in the Chesapeake Bay watershed (2025)

Source: The Nature Conservancy, Chesapeake Fish Passage Prioritization

The Aquatic Organism Passage scoring process uses 13 variables, including width of the crossing compared to the width of the stream and the height of the drop from pipe/outlet to the stream downstream of the crossing. The 2016 report determined that in the area, there were 50 road stream crossings that blocked fish passage, and 100 more that limited access to the habitat upstream of the culvert. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act create a Culvert Removal, Replacement, and Restoration Grant Program and a Wildlife Crossing Pilot Program in the U.S. Department of Transportation, opening up the possibility of substantial new funding for projects to expand aquatic species passage from a new source.23

thousands of stream crossings can be assessed for their impact on fish passage, so funding can be prioritized for projects offering the greatest benefit/cost ratio

Source: North Atlantic Aquatic Connectivity Collaborative (NAACC), Scoring Road‐Stream Crossings as Part of the North Atlantic Aquatic Connectivity Collaborative (NAACC)

American eels are the only catadromous species in North America, breeding in the ocean and spending adult lives in freshwater rivers

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service/Duane Raver, American Eel

Riverton Dam on the North Fork of the Shenandoah River at Front Royal before removal

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Habitat Restoration Highlights - 2013 Projects

removing Baber's Mill Dam on Rock Island Creek in Buckingham County in 2024 removed a death trap for the endangered James River spinymussel

Source: Animalia, James River spinymussel