Newport News proposed to build a reservoir in King William County to increase water supply for municipal (drinking water) and industrial use

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Newport News proposed to build a reservoir in King William County to increase water supply for municipal (drinking water) and industrial use

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Once Virginia Beach and Chesapeake solved their water supply problems with the Lake Gaston project, the most vigorous proponents for a new dam and water supply reservoir in southeastern Virginia were the community leaders in the Newport News area on the north side of the James River.

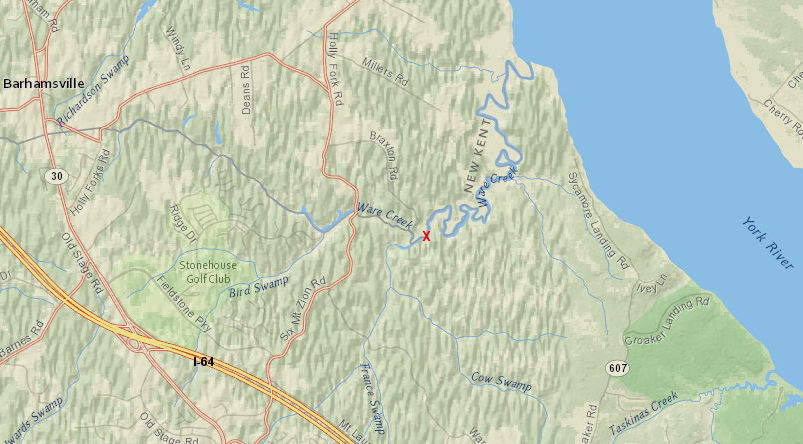

Different jurisdictions in the northern side of Hampton Roads initially proposed separate solutions. James City County sought to build a 48-foot high dam across Ware Creek to capture surface runoff and expand its water supply beyond existing groundwater wells, creating a 1,217-acre water supply reservoir to supply 10 million gallons/day. The reservoir would be on the border with New Kent County, and that county would be entitled to 30% of the new water supply.

The US Army Corps of Engineers twice issued a Section 404 permit to allow dredging and filling in the waters of the United States to create the Ware Creek Reservoir. Each time the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used its veto authority in the Clean Water Act to block the project because it would damage 425 acres of wetlands in James City and New Kent counties, eliminate a great blue heron rookery in France Swamp, reduce wintering habitat for black ducks, and alter the flow of nutrients into the York River.

Federal courts ruled that EPA had the authority to block the reservoir, even if no alternative water supply existed for James City County.1

the dam proposed by James City County on Ware Creek (red X) would have created a reservoir that flooded France Swamp and Bird Swamp beyond I-64

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

EPA made clear that a regional project would receive more support, because one consolidated reservoir would create fewer environmental impacts. In 1987, during the legal disputes over the Ware Creek Reservoir, representatives of James City County, York County, Williamsburg, and Newport News formed a Regional Raw Water Study Group.

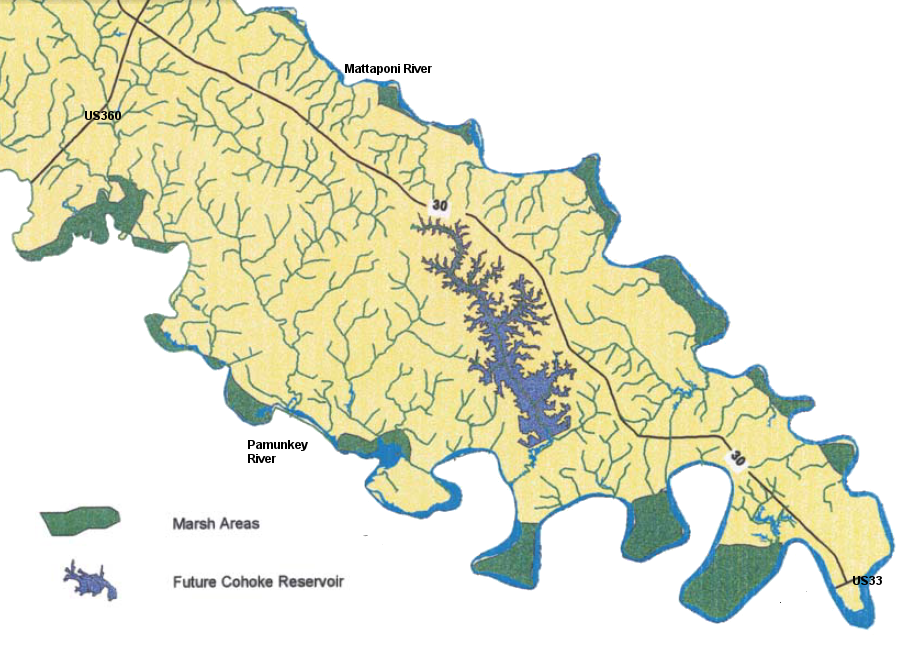

That multi-jurisdictional group examined over 30 alternatives, determined that groundwater supplies would not be adequate, and proposed a new dam and surface water reservoir on Cohoke Creek to meet the water supply needs on the Peninsula. They chose a location on the north side of the Pamunkey River because groundwater supplies within the boundaries of Newport News are saline, due to the disruption of aquifers by the Chesapeake Bay bolide 35 million years ago

The urban areas obtained support from officials in rural King William County, which had little need for the water, to reduce potential lawsuits and increase the potential for state and Federal approval of the proposed King William Reservoir on Cohoke Creek. As the Regional Raw Water Study Group described it:2

King William Reservoir Project

Source: Implementation Assessment

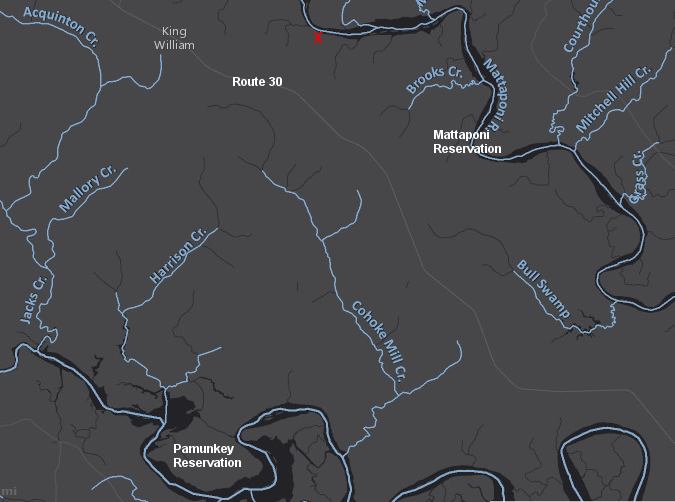

Newport News and its partners planned to build a dam on Cohoke Creek in King William County. Cohoke Creek alone did not have sufficient waterflow to fill and maintain the reservoir, so Newport News Waterworks planned to draw up to 75 million gallons/day from the Mattaponi River. The intake would be at Scotland Landing, upstream from the Mattaponi Indian Reservation. A pipeline over one mile long was planned to carry the river's water over the watershed divide (marked by State Highway 30) into the Cohoke drainage.

The King William Reservoir proposal was adopted by the Regional Raw Water Study Group as the proposed alternative in 1993. After getting comments, Newport News moved the original dam site almost two miles up Cohoke Creek. That change reduced the water supply in the reservoir by over 40% from 21 to 12 billion gallons, but also eliminated impacts to 216 acres of wetlands. The final version of the proposed reservoir would have covered 1,526 acres.

Dam Site IV (red X), the final proposed location for the King William Reservoir dam, was 3.5 miles upstream from the Cohoke Mill Pond dam

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The reservoir would be located in King William County, but the demand for treated water was in Newport News and James City County. A 12-mile long mile pipeline was planned to carry water from the proposed reservoir to Beaverdam Creek, crossing underneath the Pamunkey River. Up to 50 million gallons/day would be pumped through that pipeline into the existing Diascund Creek Reservoir, and the water would be treated by the Newport News Waterworks plant.3

Major objections came from environmentalists (the project would have flooded over 400 acres of wetlands, threatened fisheries in the Mattaponi River, and potentially facilitated more urban sprawl) and the two Native American tribes near Cohoke Creek, the Mattaponi and the Pamunkey. The pumps on the Mattaponi River would have been in fresh water, upstream from the line where saltwater intrudes from the Chesapeake Bay. Since the Mattaponi River's average flow is 500 million gallons/day at that site, the city felt the environmental impact would be acceptable.

The reservoir project partners spent over $50 million before environmental objections from the US Army Corps of Engineers prevented issuance of a Section 404 permit, as required under the Clean Water Act. Newport News finally cancelled plans in September 2009.

water would be removed from the Mattaponi River at Scotland Landing (red X) and pumped over State Route 30 into the Cohoke Creek watershed to create the King William Reservoir

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Scotland Landing - proposed site of pumping station on Mattaponi River and pipeline to reservoir

Source: Mattaponi pump station & pipeline (Map 1), King Willam Reservoir Project

The Cohoke Creek and the surrounding forest is not unique in the area, but two "threatened" species (the sensitive joint-vetch and the small whorled pogonia, small plants rarely noticed by non-botanists) may be present. Converting the creek valley to a flatwater lake would not destroy critical habitat, and the $31 million wetland mitigation plan would have reduced the environmental impact.

Nonetheless, it would have dramatically changed the local landscape, and perhaps the local culture, and there was steady and intense opposition. The Mattaponi tribe revealed in 1999 that a secret sacred site would be destroyed by the reservoir. Newport News Waterworks managers were unable to provide sufficient mitigation to reduce the tribe's concerns and gain their support.

The recreational impact of the new flatwater reservoir on the local economy would not have been significant, in contrast to the impact of Lake Gaston and Smith Mountain Lake on the rural communities surrounding those reservoirs. Lake Gaston and Smith Mountain Lake are located far from the coast, but there are large cabin cruisers in back yards of Bedford, Franklin, Brunswick, and Mecklenburg counties because those lakes are large enough to support recreation in large boats.

The proposed reservoir in King William County would have been much smaller, and would have been located close to existing marinas that already offer opportunities for cruising on the Chesapeake Bay. King William Reservoir would support picnics, small boats, and swimming, but it was difficult to picture a major recreational boom associated with a reservoir which would have a "bathtub ring" of mudflats on the edge during later summer months when water was withdrawn.

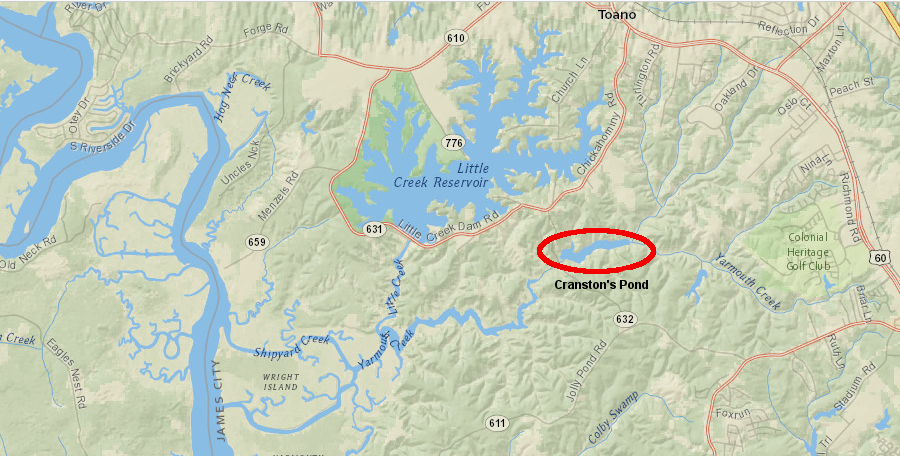

mitigation proposed to offset environmental impacts of the King William Reservoir included removal of the dam creating Cranston's Pond, re-connecting all of Yarmouth Creek to the James River, and purchase of various tracts in the watershed surrounding Cranston's Pond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The first barrier to building the reservoir was the Army Corps of Engineers; only later did local and regional environmentalists organize, object, and use the courts to block various approvals. In 1999, the District Engineer in Norfolk rejected the request for a Section 404 permit, which was required under the Clean Water Act to destroy Federally-protected wetlands in order to construct the dam and reservoir.

The rejection showed that the environmental sensitivity in the Army Corps of Engineers changed after the Norfolk District had issued approvals for the Ware Creek Reservoir. The Federal official's rationale in 1999 echoed the debates about increasing the water supplies for Los Angeles, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and other growing urban areas in the western United States. The District Engineer rejected the requested permit for the King William Reservoir and suggested the Peninsula communities had a better alternative - conservation.

Conservation to reduce water demand vs. build new dams to increase water supply is a common debate west of the 100th Meridian. The tradeoff was rarely an issue in Virginia, which gets over 40 inches of rain annually. The District Engineer estimated the water deficit for Newport News and its partners at 17 million gallons/day, and considered a proposal to build a reservoir to provide 40 million gallons/day to be excessive. Only after Newport News and its partners in the proposal had reduced demand would the Corps consider a project to increase the supply to be "needed."

Other alternatives besides the King William Reservoir that were considered in the Environmental Impact Statement were:

much of the Cohoke Creek watershed was planned to be converted into the King William Reservoir

Source: King William County, 2003 Comprehensive Plan Update

At the city's request, Governor Gilmore appealed the adverse decision from the District Engineer. After reviewing the appeal, the Norfolk District office was over-ruled by officials in the Corp's North Atlantic Division in New York. A Section 404 permit under the Clean Water Act was issued by the Corps in 2005.

EPA chose to accept rather than object to the Corp's permit, even though environmental impacts had not been mitigated further. In contrast, in the 1980's and 1990's EPA had twice vetoed Corps approval of a similar dam/reservoir project on Ware Creek in James City County. EPA had advocated for a regional solution then, and accepted the King William Reservoir as the appropriate response to its objections regarding the Ware Creek project.

The Federal permit from the Corps of Engineers was not the only major hurdle for the King William Reservoir. In May, 2003 the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (a state agency) denied an essential permit to build the intake pipe in the Mattaponi River, in order to protect the spawning and nursery area for shad in the Mattaponi River near the proposed intake. As described by the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay:5

In response, Newport News sued the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. After a rehearing (and reportedly some behind-the-scenes pressure by state politicians), the Virginia Marine Resources Commission issued the required state permit for the water intake on August 12, 2004.

American Shad

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service

The other state agency involved was the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). It issued a Virginia Water Protection Permit in 1997, and affirmed it again in 2002. DEQ ruled on December 27, 2004 that the reservoir complied with Virginia's Coastal Resources Management Program. On November 4, 2005, the Virginia Supreme Court affirmed that the State Water Control Board permit was legal.

In mid-November, 2005, the Corps of Engineers issued the final Section 404 permit to permit destruction of 403 acres wetlands in the valley of Cohoke Creek, and replace them with 806 acres of restored or newly-created wetlands elsewhere. That left two remaining potential barriers to construction: a court's interpretation that the 1677 treaty between the colony of Virginia and the Mattaponi Indian tribe would require tribal approval of the project, or a court decision overturning the Corp's 2005 approval.

The lawsuit by The Alliance to Save the Mattaponi River, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, the Sierra Club, and the Southern Environmental Law Center ended up killing the project. On March 31, 2009, a Federal District judged rejected the Corp's 2005 approval of the Section 404 permit, saying:6

On April 30, 2009, the Corps of Engineers directed Newport News to stop work on "all activities previously authorized by the permit." In addition to the costs of additional studies required by the Corps, the project managers identified a high risk that the state DEQ and Virginia Marine Resources Commission permits would expire and that the Corps of Engineers would not issue a new Section 404 permit.7

Newport News finally abandoned efforts to build the King William Reservoir on September 22, 2009. Instead, the city announced it would:8

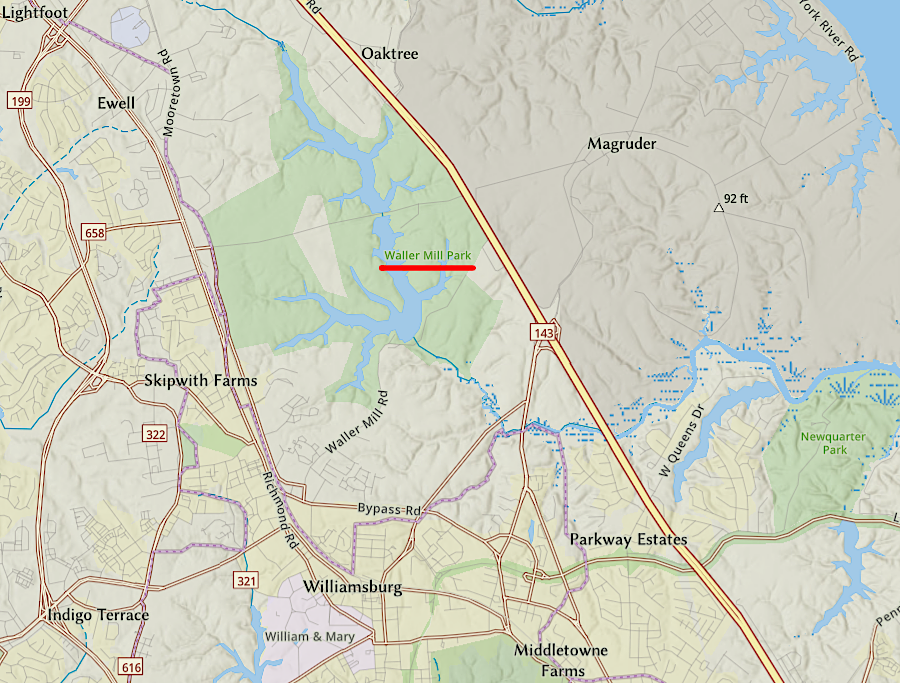

The only other jurisdiction on the Peninsula with control over a drinking water reservoir is the City of Williamsburg. It acquired Waller Mill Reservoir in 1944, after the Federal government dammed Queens Creek to create a water supply for Camp Peary.

Cancellation of the King William Reservoir will limit the ability of Newport News to shape and benefit from new development outside of the city's boundaries. Because the King William Reservoir was not built, Newport News can not maintain a dominant position in future water supply systems for neighboring jurisdictions.

the City of Williamsburg owns Waller Mill Reservoir, ensuring it controls the city's water supply

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Of the nearly $50 million spent on the failed project, Newport News used $8.3 million to buy land for the planned 1,500-acre reservoir. The city retained ownership of the land it purchased in King William County until 2022, when it began to sell off parcels.

King William County had owned much of the 1,462 acres purchased by Newport News Waterworks. The county had the option to re-acquire the land by returning the sale money, but realized that the value of the land was far below the price which had been paid. As reported in The Virginian-Pilot:9

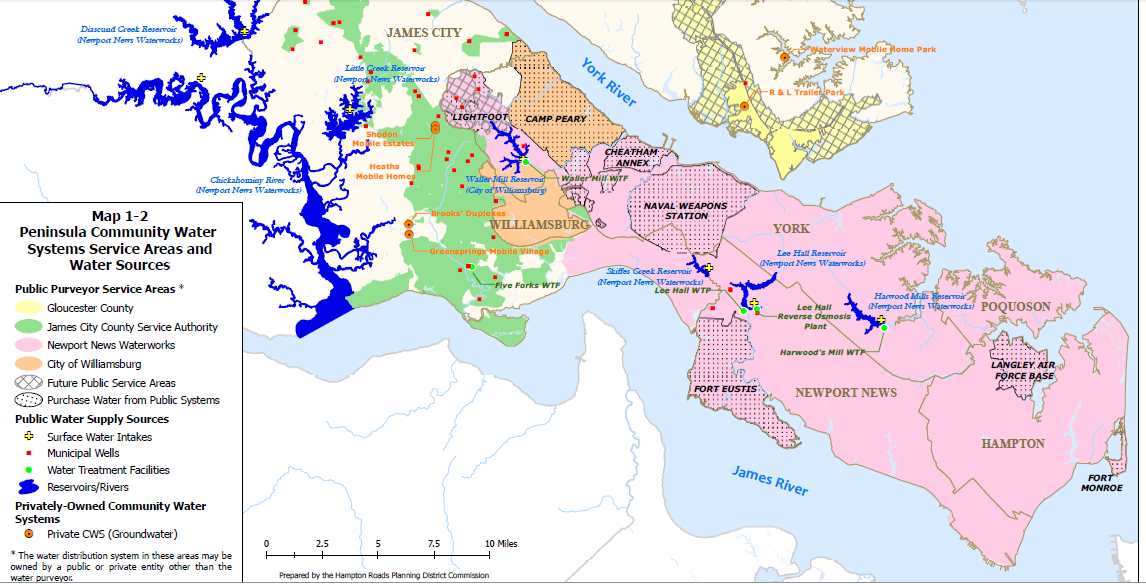

existing municipal water supply sources on the Peninsula (without King William Reservoir)

Source: Source: Hampton Roads Regional Water Supply Plan, Map 1-2: Peninsula Community Water Systems Service Areas and Water Sources

The decision to block the King William Reservoir, because it was not the least-environmentally damaging practicable alternative, set a precedent for a later issue: widening US 460. The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) planned to create a new road parallel to current US 460, in order to improve the ability of the Port of Virginia to attract container traffic.

The proposed $1.4 billion, limited-access toll road between Suffolk-Petersburg was designed for trucks to carry cargo faster between terminals in south Hampton Roads and I-95. The "Heartland Corridor" rail improvements had been completed in 2010, allowing trains to bypass road crossings in Hampton Roads and expanding tunnels in the mountains of Virginia/West Virginia to permit double-stacked container traffic.

The new US 460 was intended to help truckers compete for the traffic, lowering transportation prices and attracting more shipping companies to the Port of Virginia.

The new highway would have impacted far more acres of wetlands, affecting up to 480 acres by VDOT's estimate in October 2013. King William Reservoir would have affected 403 acres. According to the Southern Environmental Law Center:10

A "404 permit" to dredge and fill the wetlands, as proposed, was not issued by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The state of Virginia finally acknowledged the Federal government would not bend to the state's will, and in 2016 the Virginia Department of Transportation approved a different alternative with far less impact on wetlands.11

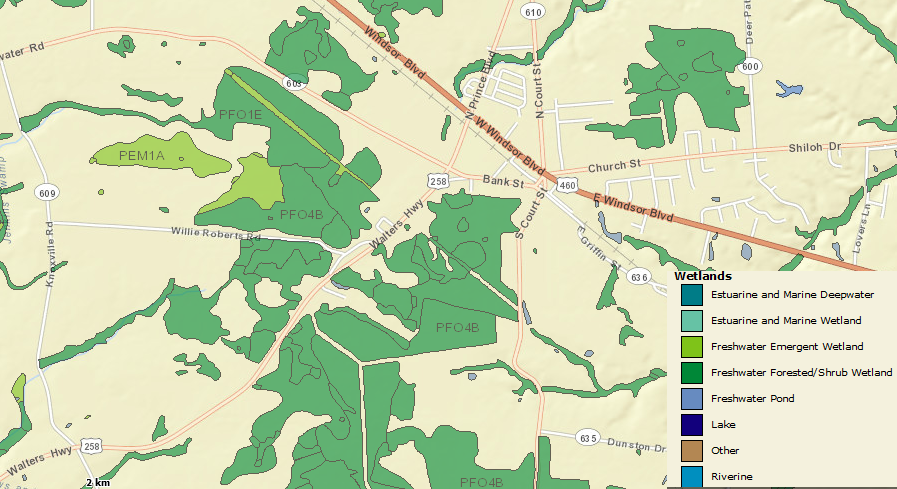

Freshwater Forested/Shrub Wetlands southwest of Windsor would have been affected by the new US 460

Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Cohoke Creek in King William County, at the time of the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, Map of King William County, VA (by Benjamin Lewis Blackford, 1865)