Byllesby Dam is one of the hydroelectric facilities operated by American Electric Power on the New River

Byllesby Dam is one of the hydroelectric facilities operated by American Electric Power on the New River

Moving water has been used to supply energy to process food, for transportation, to power mills/iron furnaces/mills/other industrial facilities, and to generate electricity.

Native Americans used the power of moving water in streams to leach the tannins out of acorns. The harsh bitterness of the tannins is a natural deterrent created by oak trees so more acorns would survive intact and produce new trees, rather than feed wildlife. The first human residents in Virginia cracked open acorns and placed them in a small riffle or below where water flowed over a rock, converting the acorns into an edible source of protein.

Native Americans and early European colonists took advantage of river currents to move canoes and sailing ships downstream. Unless there was some urgency, trips were timed to take advantage of the twice-daily tides, moving ships upstream with less effort. Though water has facilitated food production and transportation for thousands of years, "hydropower" normally refers to the use of the use of the energy of falling water to turn a wheel, lift a saw, squeeze a bellows, or spin a turbine.

A dozen years after arriving at Jamestown, the English colonists stated building an ironworks at Falling Creek. The mechanical energy of the water dropping over the Fall Line was sufficient to power the bellows at the first iron blast furnace in North America. The first hydropower plant in Virginia was part of an industrial operation to smelt iron.1

Other colonists on the Coastal Plain used falling water to power mills that ground wheat/corn into flour. Dams across streams trapped water, which was then directed from the pond through a ditch (mill race) to the water wheel. The water dropped from the end of the mill race and spun wheels. Mills designed with undershot wheels directed the water flow at the bottom of the wheel. At the more-common overshot wheels, water dropped into buckets on the top of the wheel.

overshot water wheels required topographic relief, with water transferring energy as it dropped from a height

Source: Library of Congress, Valentine's Mill, Louisa County, Virginia (by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1935)

A 10-foot high overshot wheels required a 12-foot difference in elevation, so the spin of the wheel would not be hindered by obstructions. The mill race was located a foot above the top of the wheel, and the bottom of the wheel was a foot above the stream.

Using water to grind grain was not a new technique; it had been used by the Greeks 2,000 years ago.2

abandoned Shenandoah Valley gristmill with inoperable water wheel, in 1941

Source: Library of Congress, Scenes of the northern Shenandoah Valley, including the Resettlement Administration's Shenandoah Homesteads (by Ben Shahn, 1941)

Waterpower also powered sawmills. Gears and belts transferred the energy of the falling water to move metal saws up and down, cutting logs into lumber.

When settlement extended upstream across the Fall Line, the greater topographical relief offered far more opportunities to generate energy. Water-powered mills were common, including private mills that met the needs of just one landowner/family and large merchant mills that serviced the local community.

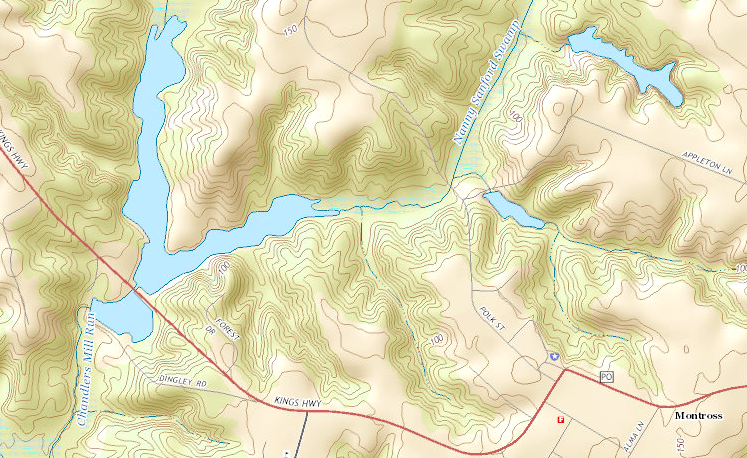

Few mills have survived on the Coastal Plain, but many of the old millponds remain. For example, colonial settlers dammed Cat Point Creek to create Chandler's Millpond in 1670. The dam was maintained until September 1993, when a heavy rainstorm caused the dam to break. When it was rebuilt, a fish ladder was included to allow anadromous fish to get past the barrier and spawn.3

Chandler's Mill Pond, near Montross in Westmoreland County, was first built in 1670

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Manchester Cotton and Wool Manufacturing Company constructed a mill powered by water in 1837-1840 on the Fall Line in Richmond. Standard Paper Company converted it into a paper mill in 1901, and added brick additions afterwards. The structure ended as a warehouse, and stood next to Mayo's Bridge until being demolished in 1983.

Water in the Haxalls Canal in Richmond powered massive flour mills in Richmond. moving grain within the mills and spinning the grindstones and rollers that converted wheat/corn into flour. Those mills also depended upon water in canals built for transportation by diverting water from the turning basin of the James River and Kanawha Canal to the mills.

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond used water from the James River and Kanawha Canal to turn the turbines at the industrial complex. The energy was transmitted by leather belts throughout the factory to shape metal to manufacture iron rails, locomotives, equipment for sugar mills in the Caribbean, and cannon for the Confederacy.4

the Standard Paper Company expanded the wool and cotton mill on Richmond's Fall Line, to utilize the waterpower available next to Mayo's Bridge

Source: Library of Virginia, Standard Paper Company building extension (July 21, 1961)

In Fredericksburg, the Fredericksburg Water Power Company re-purposed the unprofitable canal system constructed by the Rappahannock Navigation Company. The system generated 5,000 horsepower prior to the Civil War. After building the Embrey Dam in 1909, the power company could supply 8,000 horsepower to customers.5

mill races carried water from the James River and Kanawha Canal to power equipment at the Tredegar Iron Works

Source: Library of Congress, Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, VA (1877)

The first hydropower operation to generate electricity powered a single light bulb in England in 1878. The first hydroelectric power plant used the Fox River in in Appleton, Wisconsin to start producing power for a paper mill on September 30, 1882.

The Ames hydro plant at Telluride, Colorado opened in 1891 and still operates there today, using much of the original equipment. The construction of a e 3.5-megawatt power plant was justified by the need to supply energy to the Gold King mine at 12,000 feet in elevation. Transmitting electricity by wire was more cost-effective than hauling coal up the mountain on the backs of burros.

That project helped George Westinghouse win the "war of the currents" with electricity distributed via alternating rather than direct current, and led to the Niagara Falls hydropower project. Another alternating current facility opened in 1893 at the Redlands Power Plant in California.

Construction of hydroelectric dams still continues. In 2015, there were plans to build 3,700 more major dams to increase worldwide production of hydroelectric power by over 70%. "Major" dams were those with the capacity to generate at least 1 MW of electricity.6

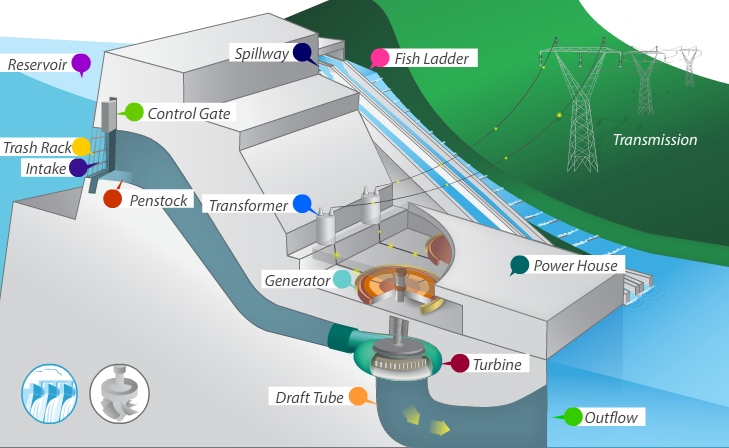

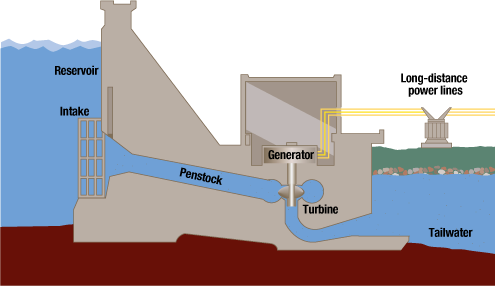

Electricity is generated at dams by converting the mechanical energy in falling water by spinning magnets inside a turbine lined with copper cables. Unlike electricity generated at facilities fueled by coal or natural gas, hydropower is "renewable." Rain falling in the watershed upstream will provide a new supply of water to spin the magnets.

dams raise water levels, increasing the potential energy before water flows through a turbine to generate electricity

Source: Department of Energy, How Hydropower Works

A "run of the river" turbine can be used to generate hydropower without a dam. A rural home might get enough electricity from a Pelton wheel in a stream, but during droughts and winter freezes the supply would be interrupted. Utilities have built dams across rivers to create reservoirs that stockpile water, just as millers built dams to ensure they had the water to operate flour mills when desired. Dams raise the water level and increase the potential energy to be derived from falling water, and reservoirs store that potential energy the way batteries store chemical energy.

hydropower facilities generate electricity by using the energy of falling water to spin a turbine, which then spins a magnet inside coils of copper wires at a generator

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, 2014 Virginia Energy Plan (Figure 4-5, originally from Tennessee Valley Authority)

In the 1800's and early 1900's, industries built dams to power textile mills and other facilities. Turbines to generate electricity were added to several of those industrial dams, especially on the Shenandoah River and New River.

In 1906, the Niagara Dam on the Roanoke River began to produce electricity. It is the smallest of the hydroelectric plants still operated by American Electric Power, but useful enough to be reconditioned in 1997. Today, the two turbines each generate 1.2MW (megawatts) of electricity.7

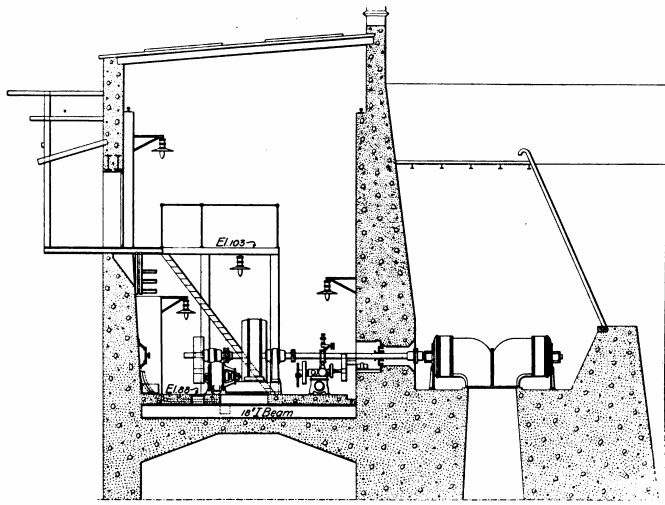

In 1908, the 700-foot long, 43-foot high concrete Emporia Dam was built across the Meherrin River by the Greenville Water Power Company. It was located just upstream of the town of Emporia, and provided both water and hydropower for the town. The powerhouse as constructed as a part of the dam, with a 3-foot thick floor designed less to support the machinery and more to resist uplift from the water.

the Emporia Dam powerhouse was built as part of the dam in 1910

Source: The Engineering Record, Building Record and Sanitary Engineer, The Hydroelectric Development at Emporia, Virginia (p.620)

By 1934, silt had filled most of the basin behind the dam, but flow through the turbines still generated electricity until 1966. By 1978 the hydropower facilities had been abandoned.

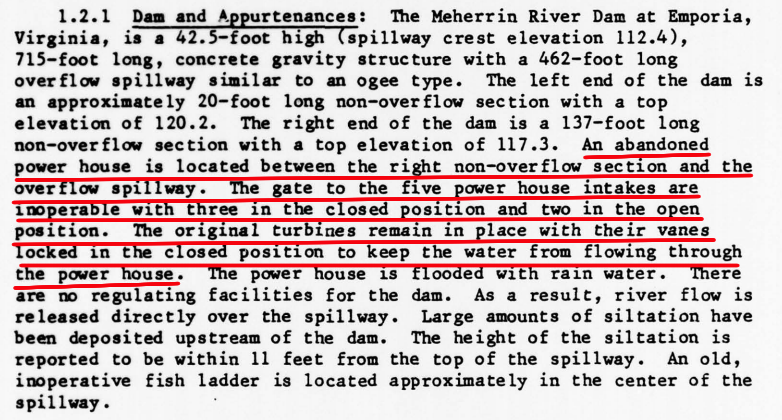

the hydropower facilities at Emporia Dam powerhouse were not functional in 1978

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Phase I Inspection Report, National Dam Safety Program, Meherrin River Dam At Emporia (p.4)

They were refurbished, and today the two turbines can generate 2.3MW of electricity for Kruger Energy. The company sells the electricity to Dominion.8

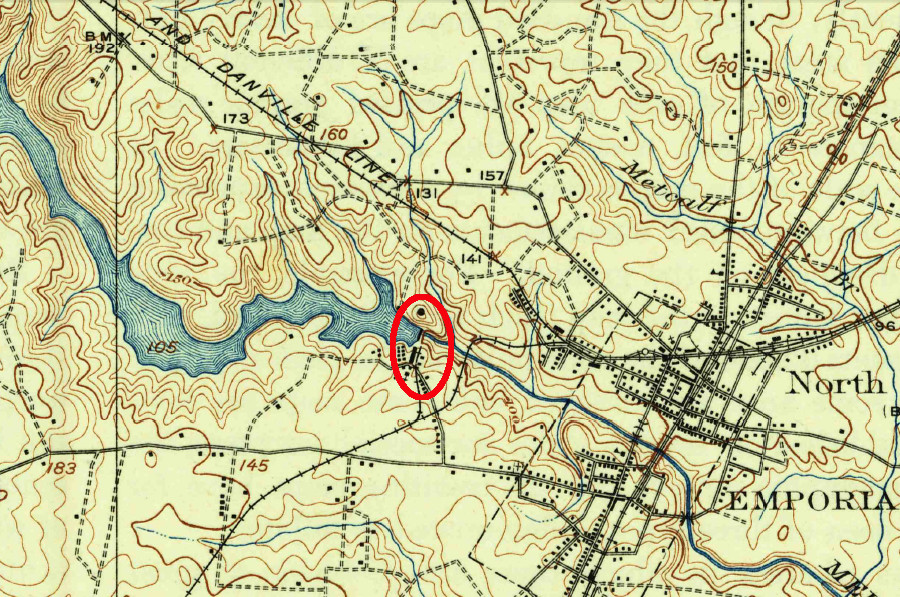

the Emporia Dam hydropower project was built on the Meherrin River in 1910

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Emporia VA 1:62,500 quadrangle map (1919)

After the Great Depression, investor-owned utilities and the US Army Corps of Engineers built major new dams designed to generate electricity.

In 1939 American Electric Power completed the dam that created Claytor Lake on the New River. In 1966, the same private utility created Smith Mountain Lake on the Roanoke River, creating the second-largest reservoir in Virginia.

Dominion Energy, then known as Virginia Electric and Power Company, built Lake Gaston in 1963. The four generators there were capable of producing a total of 220MW (megawatts).9

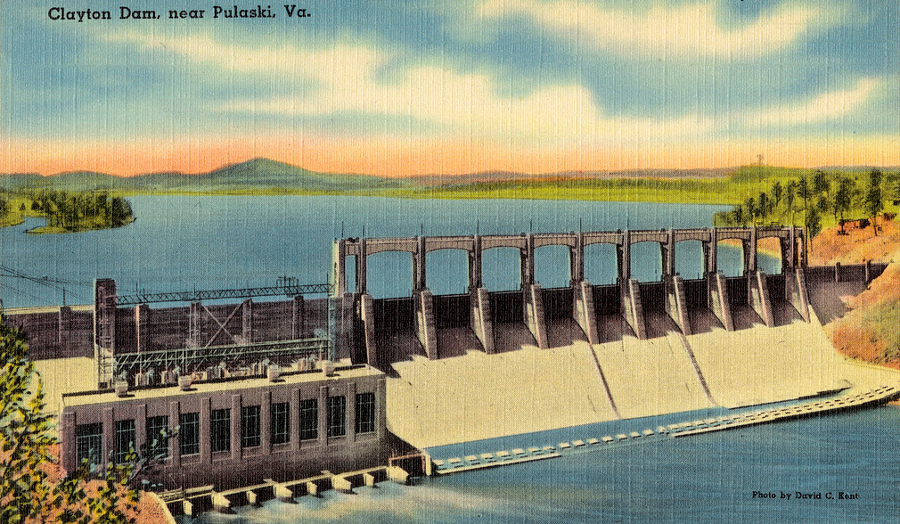

the availability of electricity from Claytor Dam on the New River helped shape the decision to locate an arsenal at Radford before World War II

Source: Boston Public Library, Clayton Dam, near Pulaski, Va

The Federal government completed two major hydropower projects in Virginia in 1953. The Corps of Engineers built John H. Kerr Dam on the Roanoke River, including seven generators that can produce 227MW of electricity. Counting the acreage in North Carolina, the reservoir (known in Virginia as Buggs Island Lake) is the state's largest.10

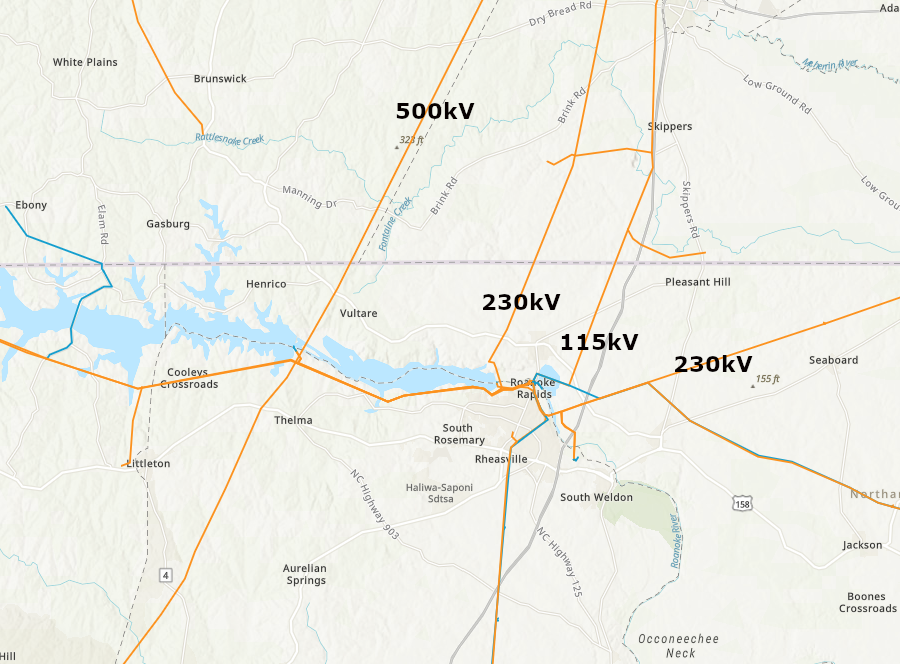

electricity generated in North Carolina by water from Virginia is carried to Virginia customers by transmission lines with different voltages

Source: Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data (HIFLD), Electric Power Transmission Lines

Though the Corps completed Philpott Dam on the Smith River in 1951, the powerhouse became operational only in 1953. The primary justifications for Philpott Dam were expected benefits from flood control and recreation, but the three generators produce 1.4MW of electricity.11

Those two Corps of Engineers projects were justified in large part by their flood control benefits. The last attempt by the Corps of Engineers to build a major dam in Virginia, the Salem Church Dam on the Rappahannock River five miles upstream of Fredericksburg, included no plans for hydropower. In the benefit/cost calculations, all benefits were based on supposed enhancements for recreation, dilution of pollution to improve water quality, management of freshwater flows to increase oyster production downstream, and flood control.12

The Corps completed the John W. Flannagan Dam on the Pound River in 1964, and the Gathright Dam on the Jackson River in 1979. Both projects were justified primarily by flood control benefits. Though production of electricity was an authorized use at Gathright Dam, no facilities were constructed there by the Federal government.

In 2012, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission approved proposals by private companies to add modules to both dams that would generate electricity. At Gathright Dam, a turbine located at the discharge outlet, and designed to be moved when the dam released pulses of water to simulate natural high water flows. That turbine was projected to generate 3.7MW of electricity.

In 2014, the US Department of Agriculture provided a $1,125,000 loan for the developer of the 3MW Flannagan Dam hydroelectric capability, as part of the Rural Energy for America Program.

Access to Federal subsidies, including a production tax credit, led a private developer to purchase the Reusens Dam from Appalachian Power in 2017. In 2011 the large utility had stopped using the 12.5MW hydroelectric facility on the James River, built originally in 1903.13

the Reusens hydropower facility, on the James River upstream of Lynchburg

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the 1960's, sensitivity towards the environment changed. Passage of the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) in 1970 required assessments of the impacts from damming free-flowing rivers, and the remaining sites for big projects had low or negative benefit-cost ratios once cultural and environmental impacts were considered.

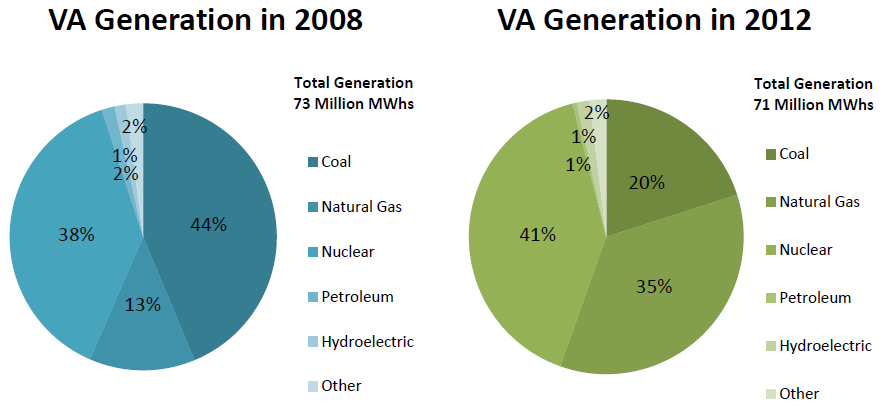

in contrast to coal and natural gas, the percentage of electricity generated in Virginia by hydropower did not change after 2008

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy, Virginia Energy Plan (2014)

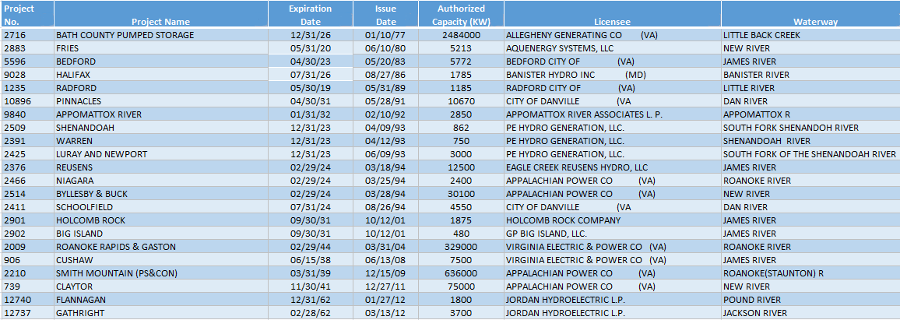

What is now the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) licenses hydropower dams owned by non-Federal organizations, including municipal governments such as the City of Radford. The smallest three of the licensed projects can produce less than 1MW (1,000 kilowatts), while the largest three can generate over 100MW:14

in 2017, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission managed 22 active licenses for non-Federal hydropower projects in Virginia

Source: Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Diagram of a Pumped Storage Project

Hydropower is a renewable energy source in Virginia, which receives over 40" of rain annually to resupply reservoirs. Because it is no longer feasible to build large hydropower projects in Virginia or other states, the opportunities to expand that source of renewable energy are limited.

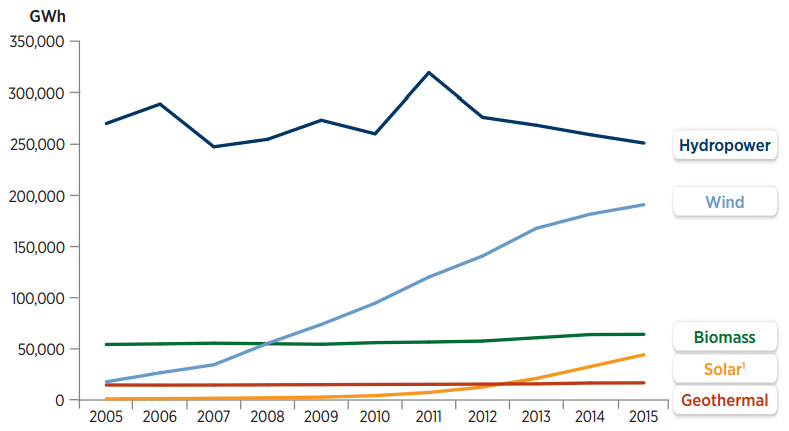

new wind and solar facilities are generating more electricity nationwide, but generation at hydropower plants is not increasing because no new dams are being constructed

Source: US Department of Energy, 2015 Renewable Energy Data Book (U.S. Renewable Electricity Generation by Technology)

The Federal government operates two hydropower dams in Virginia. The US Army Corps of Engineers built both John H. Kerr and Philpott dams. The Gathright Dam, also built by the Corps, was not designed to generate electricity.

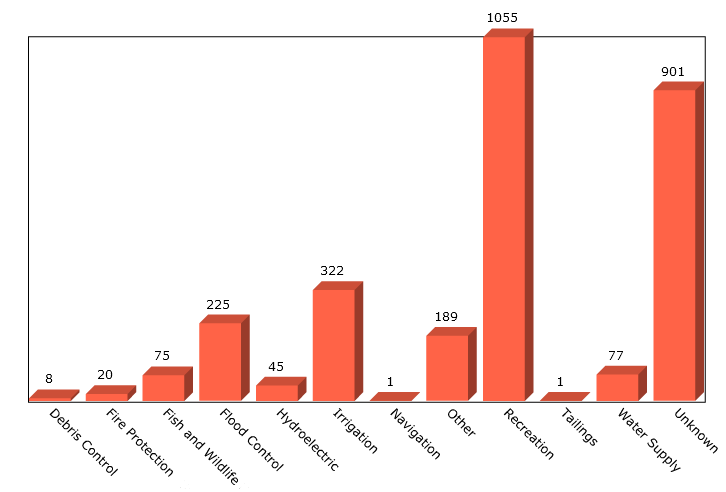

The National Inventory of Dams says there are 2919 dams in Virginia, and the primary purpose of 45 of those is hydropower. Many of those dams, such as the Fairfax Water dam on the Occoquan River, no longer generate electricity.15

According to the 2014 Virginia Energy Plan:16

The greatest potential is to create another pumped storage facility, similar to the projects in Bath County and at Smith Mountain. Pumped storage projects consume more electricity than they generate, but are massive batteries able to provide power at times of peak demand. The General Assembly passed legislation in 2017 to incentivize utilities to build a pumped storage project in the coalfields region of Virginia, and Dominion Energy selected two sites for further study later that year.17

hydropower is the primary purpose of very few dams in Virginia

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, National Inventory of Dams

Some hydropower dams divert water from the stream, pipe it through a turbine, and then return the water to the stream at some point further downstream. Directly below the diversion dam, the water flow is reduced. The Virginia Department of Water Quality issues permits for withdrawals from tidal waters and for withdrawals that exceed 10,000 gallons per day from non-tidal waters, if the withdrawal started or increased after 1989. There are multiple exemptions to the requirement to obtain a permit, including:18

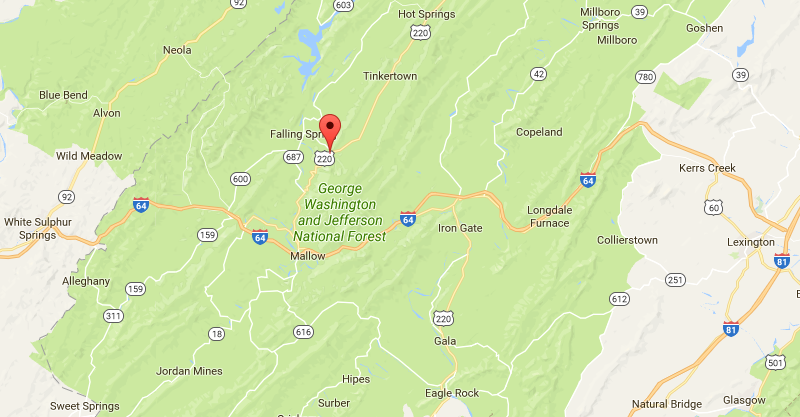

The state agency reacted in 2017, when a hydroelectric power generating facility on Falling Springs Creek withdrew all of the water from the stream. The facility used twin 24-inch pipes to transport water to a power generation house over one mile downstream and 390 feet in elevation below the withdrawal intake, producing about 500kw of electricity.

The hydropower plant, downstream from the waterfall that gives Falling Springs Creek its name, dated back to 1910. Between 2007-2012, a culvert had been removed and other changes made to increase the amount of water diverted from the stream. In 2016 the Virginia Department of Water Quality offered conditional authority to Hydro-FS LLC to operate while the facility obtained a permit, but the owners chose not to sign the Letter of Authorization.

After receiving a citizen complaint in 2017, the state agency discovered that so much water was being diverted that the streambed was dry below the dam and fish were being killed. The Virginia Department of Water Quality issued a Notice of Violation, to protect the state's aquatic resources.

The owners of the hydropower facility agreed to cease operations, welding plates on the heads of the 24-inch pipes to prevent water diversion. A company official commented:19

Hydro-FS LLC diverted too much water from Falling Springs Creek in Alleghany County, killing aquatic life and violating its permit from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality

Source: Google Maps

Today Virginia has 25 hydroelectric facilities. There are also two pumped storage plants, at Smith Mountain and in Bath County.

In 2021, the US Congress passed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act). It included over $500 million for non-Federal owners of qualified hydroelectric facilities to make dame safety and environmental improvements, and to enhance grid resiliency. The US Department of Energy distributed the funds via the "Maintaining and Enhancing Hydroelectricity Incentive" program.

In 2024, $2.1 million was awarded to Appalachian Power to replace a turbine-generator unit at the Byllesby hydroelectric plant on the New River in Carroll County. An additional $5 million was awarded to replace two units at Claytor Dam further downstream. Federal funding helped Appalachian Power generate more carbon-free electricity at those two facilities.20

in 2024, Appalachian Power received $5 million from the US Department of Energy to replace two turbine-generator units at Claytor Dam in order to generate more carbon-free hydropower

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

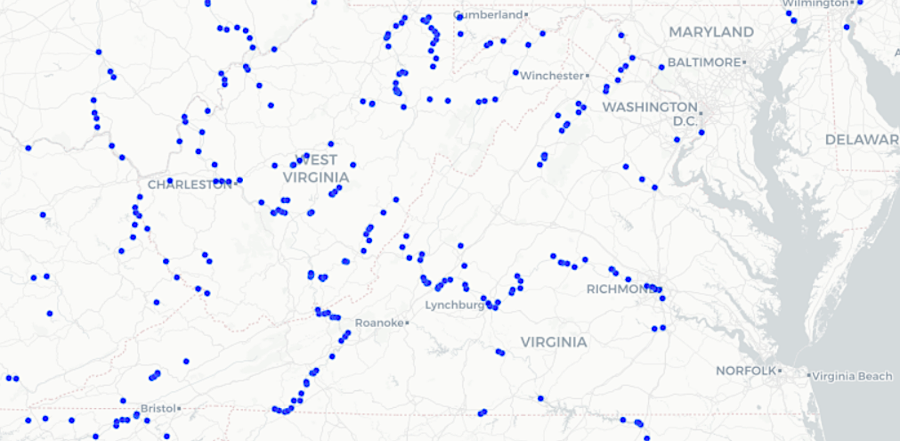

Virginia has multiple sites with theoretical potential for small hydropower projects

Source: US Department of Energy, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Renewable Energy Atlas

water from the Little River reservoir spins the turbine, then is discharged back into the Little River at the City of Radford's 1MW hydroelectric plant