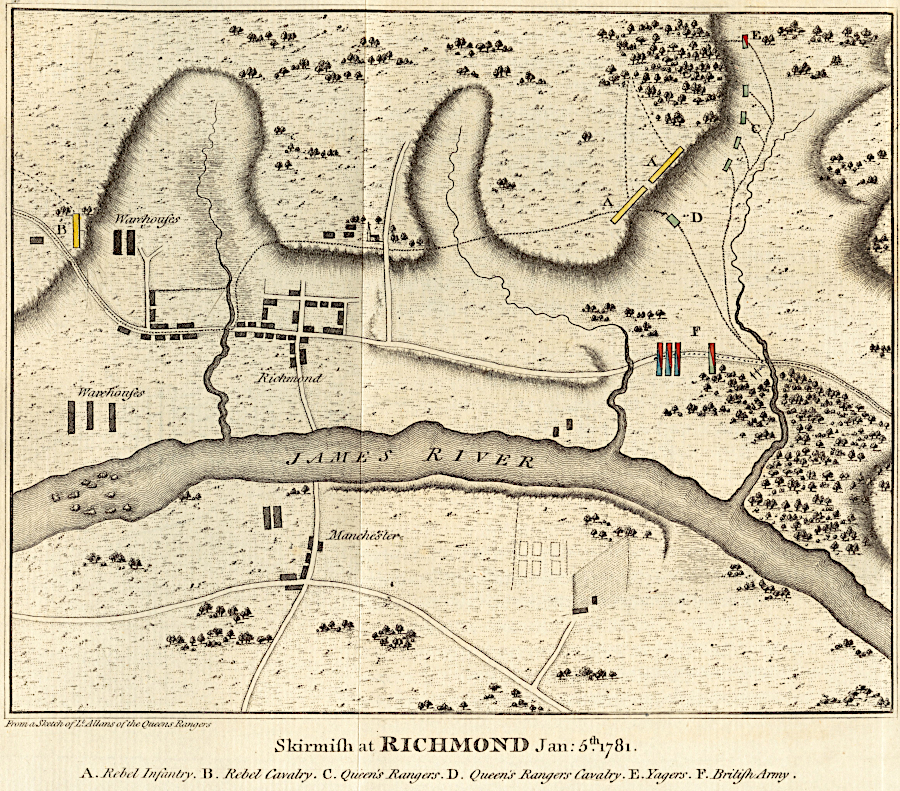

British forces under Benedict Arnold reached Richmond in January, 1781

Source: Leventhal Map Collection, Boston Public Library, Skirmish at Richmond Jan. 5th. 1781

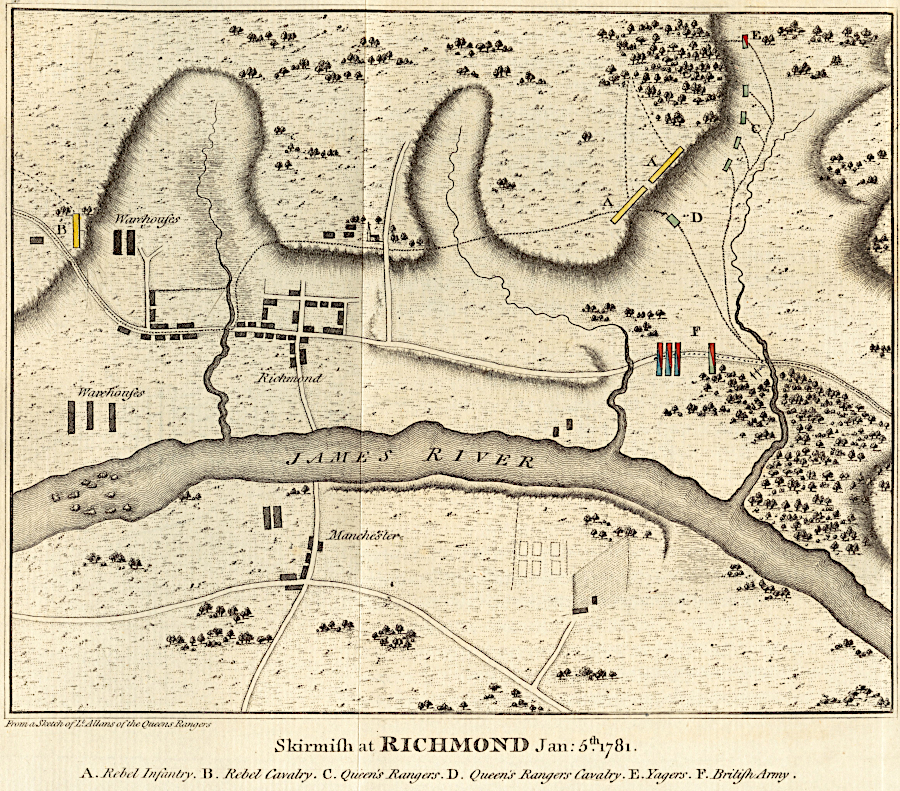

British forces under Benedict Arnold reached Richmond in January, 1781

Source: Leventhal Map Collection, Boston Public Library, Skirmish at Richmond Jan. 5th. 1781

Between 1775-1783, 13 colonies rebelled against Great Britain and successully fought a war that enabled the creation of the United States of America. Virginians played a leading role in both the political and military components of the American Revolution.

At the first Continental Congress in 1774 the delegates from Massachusetts, the most agressive colony challenging royal authority, intentionally pushed for Virginia delegates to have a prominent role. In 1774 Peyton Randolph was elected to preside over the first meeting in Philadelphia. In 1775 George Washington was chosen to be the commander of the Continental Army. In 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced the resolution in the Continental Congress calling for the colonies to declare independence from Great Britain.

Washington, the "indispensible man," managed to keep a military force in the field despite political rivalries among the colonies/states, poorly trained and poroly-equipped troops, inadequate funding by the Continental Congress to pay soldiers and acquire supplies, and numerous defeats by more-profressional troops from Great Britain and what today is Germany. He personally faced down at least one attempted mutiny.

While in camp at Valley Forge in December 1777, Washington wrote that because of the inadequate amount of food and clothing:1

Throughout the war he respected the authority of civiliian leaders in the Continental Congress. After the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783 he resigned his commission rather than sought to establish control over the new nation. George III, who remained as king even though he was physically unable to serve in y supposedly said that resignation would make Washington "the greatest man in the world."2

The number and significance of battles fought in Virginia during the American Revolution were relatively few, but the defeat of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781 is justifiably famous because it was critical to convincing King George III and Parliament to stop fighting.

The most important impact on Virginia families was the number of men who were killed or wounded, or who died from disease while in a military unit. The war led to independence for the citizens of Virginia, but some of the non-citizens also found freedom. Wherever British troops marched, enslaved people took the opportunity to escape. Many ended up succumbing to smallpox, typhus, and other diseases, but some ended up leaving Virginia with British forces between 1776-1783.

Thousands of troops marching across Virginia, accompanied by fleeing slaves and other camp followers, left a trail of destruction. At the very start of the conflict Norfolk, the largest town in the colony, was burned to the ground. The shipyard at Gosport on the Elizabeth River and a new Virginia Navy shipyard built on the Chickahominy River were also burned. Plantations from the Chesapeake Bay to the Blue Ridge were raided, with the destruction of livestock and crops, fences, farm equipment, and houses. Public buildings in the capital of Richmond were destroyed, as were military facilities such as the barracks at Chesterfield Court House and the Westham Armory upstream of Richmond.

Source: American Battlefield Trust, The Revolutionary War in the North: Animated Battle Map

Source: American Battlefield Trust, The Revolutionary War in the South: Animated Battle Map