a convention of all-male, all-white Virginia gentry adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights in June 1776

Source: Library of Virginia, Adoption of the Virginia Declaration of Rights

a convention of all-male, all-white Virginia gentry adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights in June 1776

Source: Library of Virginia, Adoption of the Virginia Declaration of Rights

For the enslaved Virginians in Virginia, the American Revolution gave them a rare opportunity to seek the "liberty" that was discussed as the justification for war.

Seen through modern eyes, there is no moral basis for slavery. Enslaved people considered it wrong from the beginning, while some religious groups grew to oppose slavery. In the 1700's, the Quakers prohibited members from being slaveowners. In contrast, Protestant denominations in Virginia split from their Northern counterparts in the 1800's and declared the "peculiar institution" to be moral.

The Tidewater gentry depended upon free labor for increasing wealth of white households. Slavery was essential to the plantation economy, and fully accepted within the white colonial culture. Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop which wore out the soil in only a few years in the days before artificial fertilizers. Virginians had lots of available land, and the limiting factor was labor. Importing Africans, often after they had been "seasoned" or proven resistant to disease after a stay on Caribbean Islands, provided the missing labor until natural increase created a sufficient supply of black men, women, and children to meet demand.

Simply acquiring labor was not sufficient. Creating a legal framework for slavery, so no wages had to be paid for agricultural labor, increased the profits of the slaveowner. During the 1600's, Virginians passed laws to define slavery as a lifetime condition - and determined that children of female slaves would also be slaves for life.

The Spanish, who faced a similar challenge with a shortage of labor for their colonial estates, crafted the encomienda system to regulate the use of indigenous people for uncompensated labor. Under pressure from the Catholic Church, however, the Spanish did not establish hereditary slavery for Native Americans. Instead, a system of peonage evolved. Workers were kept so deep in debt they were obligated to work in perpetuity. In Mexico and other Spanish colonies, the people taking unfair advantage of indigenous labor were less involved in controlling the personal lives of the workers, in contrast to the owners of slaves in British North America. Children of Spanish-controlled workers were not the property of the employer that could be sold despite the family's objections.

In England, Lord Mansfield ruled in the Somerset Case in 1772 that a slave purchased in America, then transported to England, could not be shipped to Jamaica as a slave against his will. In Lord Mansfield's opinion, since Parliament had not expressly passed laws defining slavery as legal, slavery was not consistent with the protections of human freedom in English common law. The decision did not abolish slavery in the colonies, or limit the slave trade between Africa and the New World, but after the Somerset Case different moral standards in England vs. America were reflected in the laws regarding slavery.

By the start of the American Revolution, the Virginia House of Burgesses was totally committed to retaining slavery as a fundamental part of Virginia society. By the time of the American Revolution, Virginia politicians had been crafting slave codes for a century. They created new law governing slavery. Slavery was not part of the common law in England, so Virginia's codes were based in part on Caribbean island practices.

On the eve of the American Revolution, Virginia plantation owners were conscious of the threat that enslaved people would support the British and be a threat to the rebellious Americans. Roughly 40% - 200,000 of the 500,000 people living in the colony - were enslaved. James Madison wrote in 1774:1

When the Virginia gentry chose to split from England, they wrote a constitution that created a new, independent state. The Fifth Virginia Convention that approved the constitution in June, 1776 was an elected body that had replaced the House of Burgesses. The Fifth Virginia Convention chose to adopt the new fundamental law without submitting it to a vote of the people - and even if there had been a vote on popular ratification, the enslaved men would not have been permitted to participate in the decision.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was adopted by the Fifth Virginia Convention before the state constitution. The Virginia Declaration of Rights declared white residents of the colony should be politically free from England, while still preventing black slaves from gaining personal freedom.

George Mason's original draft was revised before adoption, because his initial language was too broad. In his initial draft of a declaration of rights, Mason said:2

The convention restricted the "all men" statement, adding the qualifying phrase "when they enter into a state of society" so the first article read (underline added):3

As defined by the Virginia elite, slaves were more in a "state of nature" and not full members of society. That distinction allowed white Virginians fighting for liberty from British oppression to justify continuing racially-defined slavery, with independence triggering no alteration in chattel slavery.

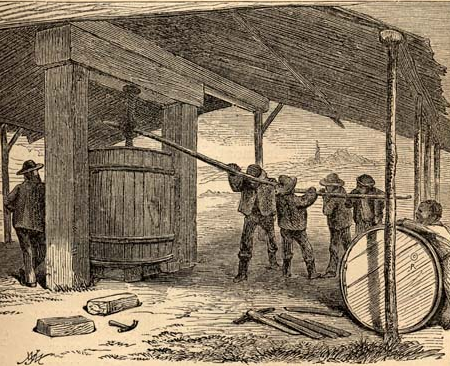

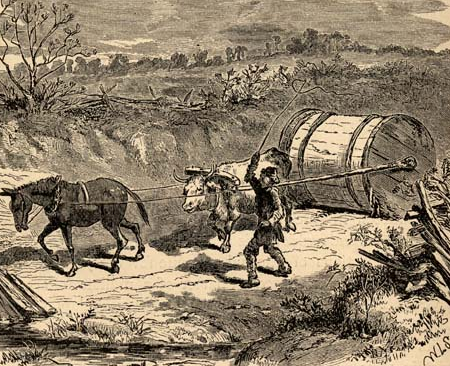

prizing tobacco into a hogshead, before rolling to a wharf for export overseas

Source: Edward King, The Great South (page 634-635)

West of the Blue Ridge, white Virginians were less inclined to follow the lead of Tidewater planters and become revolutionaries. Western Virginians were opposed to economic domination by the wealthy elite in Tidewater who controlled the House of Burgesses and the Council of State. Independence would grant even more power to the Tidewater gentry. Westerners saw some value in retaining the ability of British officials to veto General Assembly bills that imposed an unfair percentage of economic hardships on those in the west who paid high taxes on land to subsidize those in the east who paid low taxes on slave "property."

In April 1775, in response to orders from London which anticipated the potential or armed rebellion, Lord Dunmore had his British troops seize the gunpowder stored in the Williamsburg magazine. About 1,000 Virginia militia gathered in Fredericksburg and, led by Patrick Henry, started to march to the capital and demand the gunpowder be returned. For his personal protection, Lord Dunmore provided weapons to his household staff and even to the Shawnee hostages being held after Dunmore's War had ended in 1774.

Having to arm enslaved workers in the Governor's Palace to ensure the personal safety of the governor and his family indicates the level of fear felt by Lord Dunmore. There were limits; he did refuse to arm black men who volunteered to assist him but were not part of his household.

Recognizing that the Virginia militia leaders were threatening to lead rather than suppress an insurrection, and that British soldiers would not arrive quickly to maintain royal authority in the colony, Lord Dunmore planned to recruit an army from local enslaved workers. He notified British officials in Boston and London on May 1 that he was considering providing weapons to enslaved Virginians and granting them freedom in exchange for their support. He made clear that he was willing to dramatically disrupt the colony to protect himself and royal authority, saying:4

The royal governor finally fled Williamsburg on June 8 and took refuge on a British warship anchored in the York River at Yorktown. He never saw Williamsburg again.

Enslaved people near the British forces took advantage of the opportunity to escape to Lord Dunmore's protection even before he issued a formal offer. Some managed to get on board British warships, while others came to Gosport once Governor Dunmore established the shipyard as his base on July 17. When the British attacked Hampton in October 1775, at least one enslaved Virginian who had come within the British lines was part of that military force.

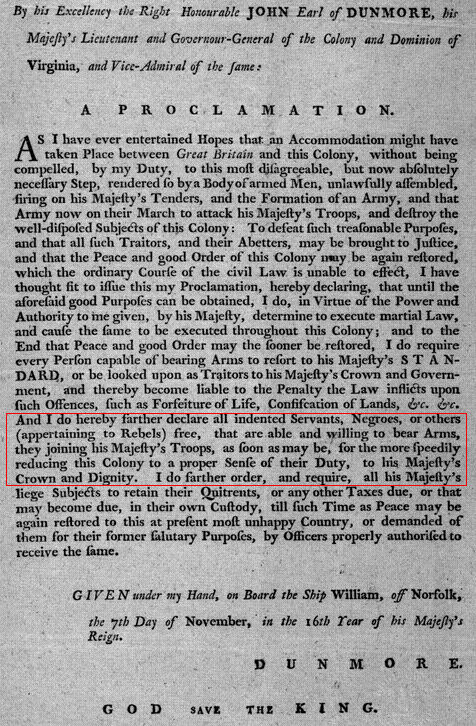

In November 1775, Lord Dunmore took the final step and offered enslaved men in Tidewater Virginia the most powerful incentive to support the British. Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation on November 7, 1775 that promised freedom in exchange for enlisting in the governor's army.

The offer was not extended to those enslaved by loyalists, or to women and children of the men. Lord Dunmore (like Lincoln in 1862) did not indiscriminately free the slaves. Only those able and willing to bear Arms were invited to join him, not women, children, or those too old or infirm to fight.

When the American rebels and the British fought at Kemp's Landing on November 15, 1775, two black loyalists captured Patriot leader Col. Joseph Hutchings. One of them had been owned by Hutchings.

When Lord Dunmore issued his proclamation after the British victory at Kemp's Landing, few of the enslaved workers could read or write. However, all could listen to the literate residents talk about the news they had read. Information about the emancipation offer was spread by word of mouth throughout the communities of the enslaved. The proclamation included:5

Dunmore's Proclamation

Source: Library of Congress, An American Time Capsule: Three Centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera

Dunmore's emancipation proclamation required that men escape from their owners and reach the British forces, then commit to fighting the American rebels. The offer of freedom was made just to men, but in many cases they brought their families. The British had to accept women and children in order to get the men to stay.

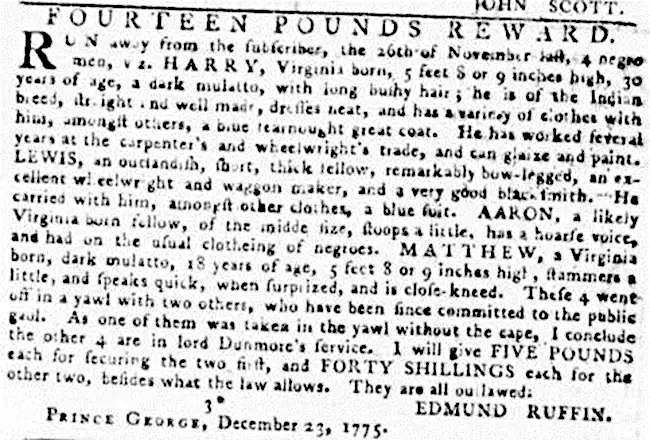

On November 26, six enslaved men fled from Edmund Ruffin's plantation and used a fishing boat to sail down the James River. They planned to join the British in Norfolk. Two were captured during the journey, but four appear to have escaped to the British and joined the Ethiopian Regiment created by Dunmore. The governor outfitted some of the men in the Ethiopian Regiment with available British uniforms. Embroidered specially on those uniforms were the words "Liberty to Slaves," mocking Patrick Henry's "Liberty or Death" phrase.

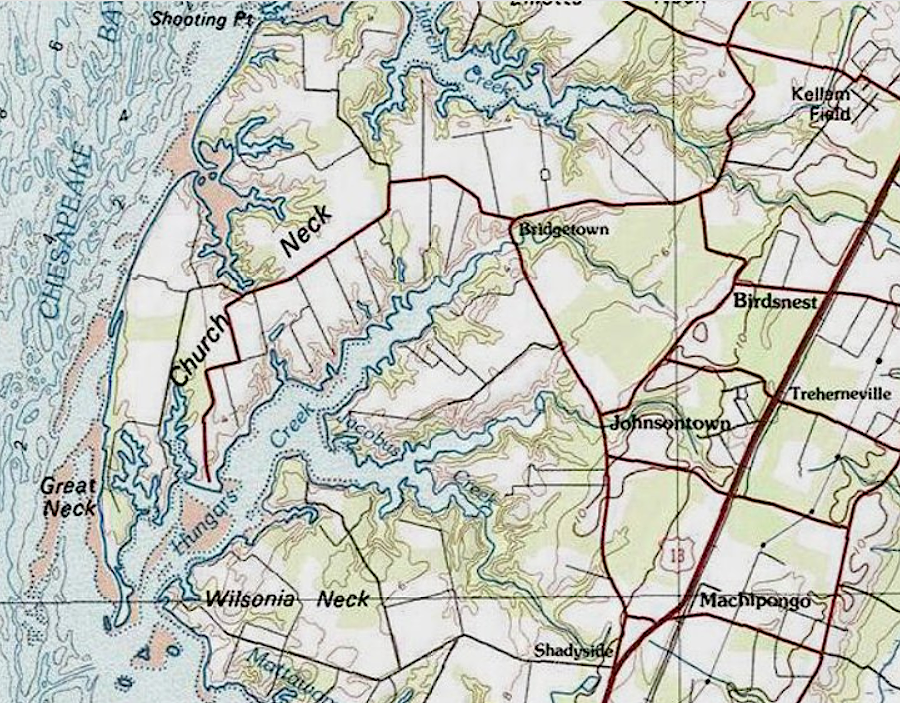

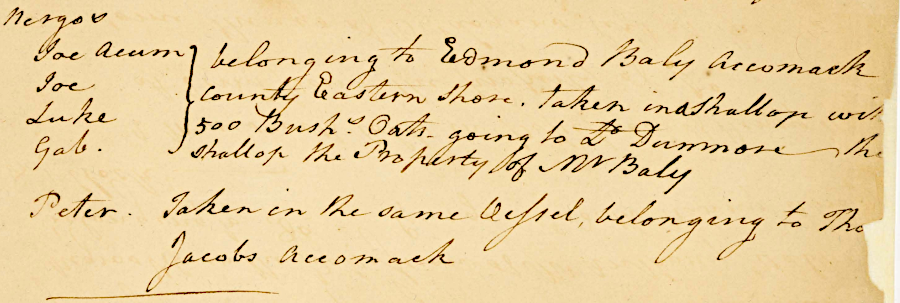

On the Eastern Shore, a self-emancipation effort in early 1776 by 13 enslaved men in Northampton County was foiled by Maryland militia. They seized a ship in Hungars Creek and sailed 20 miles across the Chesapeake Bay, nearly getting to the mouth of the York River before being recaptured. The captains of the Maryland force reported to that state's Committee of Safety:6

13 enslaved people seeking to escape to the British were captured in February 1776, after they had seized a schooner in "Hungers" Creek

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The 200-300 black men from Virginia organized into Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment served under an all-white officer corps of British men. White loyalists who joined the British to fight were organized in a separate Queen's Own Loyal Virginia Regiment, also with British officers. The white and black loyalists added significant numbers to Dunmore's army, which was otherwise limited to British marines and sailors on the warships.

Edmund Ruffin offered a reward to recapture men who fled from his plantation on November 26, 1775

Source: National Park Service, Virginia: Group Escape, November 26, 1775

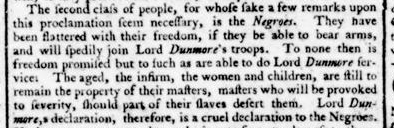

The Virginia planters tried to block slaves from joining Dunmore, and issued their response to his proclamation a month later. The Virginia Declaration issued on December 14, 1775 threatened execution of any slave who joined Dunmore, but offered amnesty to any who changed their mind and willingly returned to "their duty."

Between 800-2,000 slaves managed to reach the British lines, almost all when they controlled Norfolk until the end of 1775. Many were left on Gwynn's Island, dead or diseased, when the British sailed away seven months later in July, 1776.

In the course of the American Revolution, around 20,000 free and enslaved black men in North America fled to the British lines and supported their military efforts against the American rebels. The opportunity to obtain liberty was enhanced during the war, but:7

Virginians quickly highlighted that Dunmore's Proclamation did not free enslaved people unable to serve in the British military

Source: Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), November 25, 1775 (page 3)

Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment was present at the battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775. That regiment was supposed to lead a diversionary attack before British troops raced across the bridge. The diversion did not occur, and British soldiers ended up being slaughtered in their failed frontal attack.

On the south end of the Great Bridge was a setinel named Billy Flora. He was a free black man who had managed to enlist in the Priness Anne County militia or the Second Virginia Regiment. Under the 1757 militia law a free black was entitled to serve in the militia as a laborer or a member of the band, but Flora carried a weapon.

On December 9, 1775 he bravely fired eight times at the British when they started replacing planks on the bridge and racing forward to attack the fort occupied by the Virginia forces. Flora then ran to safety in the fort, grabbing the last plank as he jumped inside. He continued to serve throughout the Revolutionary War and earned a 100-acre land grant. In 1782, he purchased his wife and two children to get them out of slavery.

As the American rebels closed in on Lord Dunmore's troops in Norfolk in late December, they captured members of Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment. The black prisoners were sent to the Public Gaol (jail) in Williamsburg. Those who did not die from disease were transported to the lead mines in western Virginia, once again having to serve as enslaved workers. The American rebels declined proposals from Lord Dunmore to exchange some of the black soldiers for captured patriots.

When Norfolk was burned on January 1, 1776, Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment was stationed a mile downstream on the opposite side of the Elizabeth River at Tucker's Mill Point. Many of those who had escaped slavery died there from disease. Dunmore eventually had them moved to a new location and inoculated against smallpox. When the British forces left the Elizabeth River in May, 1776, the black soldiers were taken to Gwynn's Island.

At one point, disease was so rampant there that the royal governor's command was reduced to around 40 white soldiers and 200 members of the Ethiopian Regiment. Many who survived the rampant typhus and malaria on the island were abandoned when Dunmore fled. The captured black soldiers were re-enslaved by the Virginians. In New York, both the Ethiopian Regiment and the Queen's Own Loyal Virginia Regiment were disbanded; members joined other loyalist units there.

Some of the black soldiers managed to flee with Dunmore when he abandoned his base on Gwynn's Island and sailed to New York in 1776. In 1779, when Sir George Collier raided Hampton Roads, 518 blacks managed to flee Virginia when he withdrew.8

When Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, the longest complaint against King George III in his initial draft was 680 words claiming the king was encouraging enslaved people in America to murder their white owners. That language was removed before the Continental Congress adopted the declaration, leaving only a complaint that George III had "excited domestic insurrection amongst us."

Though the British welcomed enslaved men into their lines, the blacks were not treated equivalent to the while soldiers. Many ex-slaves still hoping for freedom via the British were severely disappointed when General Leslie withdrew from Portsmouth in 1780. He left behind several hundred, because the British ships lacked room.9

Despite the risks, attaching themselves to the British army remained the best opportunity for enslaved Virginians to gain freedom. After General Benedict Arnold arrived in Hampton Roads again at the very end of 1780, more enslaved people attached themselves to the British Army again. In March 1781, the British hospital in Norfolk was threatened by Virginia militia. The Hessian captain in charge of the Jaeger Corps recruited wounded soldiers to help defend the site, but he also armed a dozen black men:10

Lord Cornwallis's army attracted numerous enslaved people as it marched through the Carolinas from Charlestown to Petersburg. Richard Henry Lee estimated there were 2,000-3,000 traveling with the 6,500 British and German troops. Incomplete documentation, based on complaints sent to the Virginia government by slaveowners, suggests perhaps 1,000-1,500 who escaped.

The families who fled to Cornwallis as he marched as far west as Charlottesville brought him horses, information about local roads, and details regarding supplies to seize in order to feed the army. The men provided labor, such as when Cornwallis decided to fortify Portsmouth.

One self-emancipated enslaved man served as a double agent for the British. He helped to lure Lafayette's forces into an ambush at Green Spring.

The same Hessian captain who had armed a dozen black men to protect the British hospital was stunned when he first saw Cornwallis's army:11

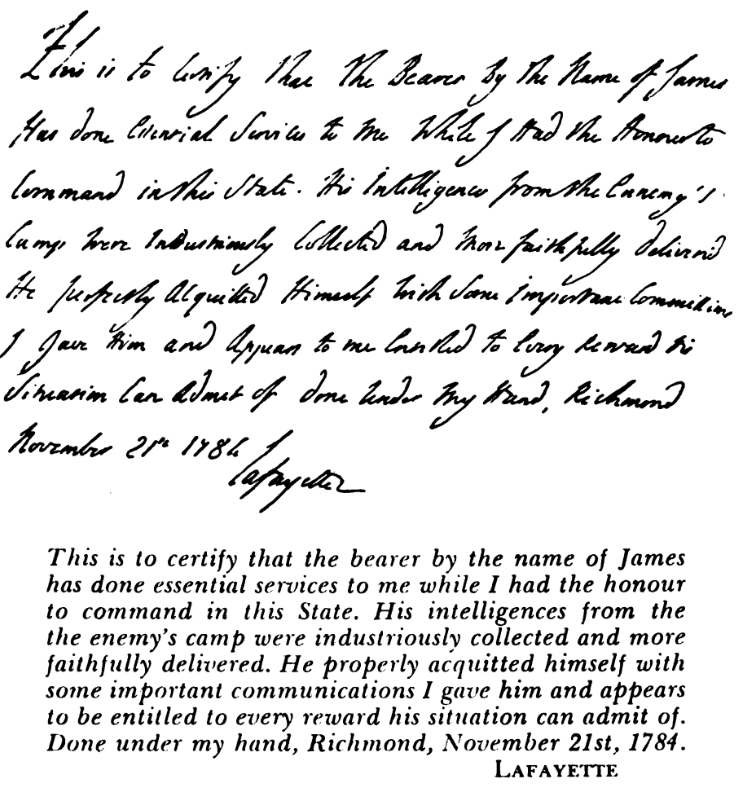

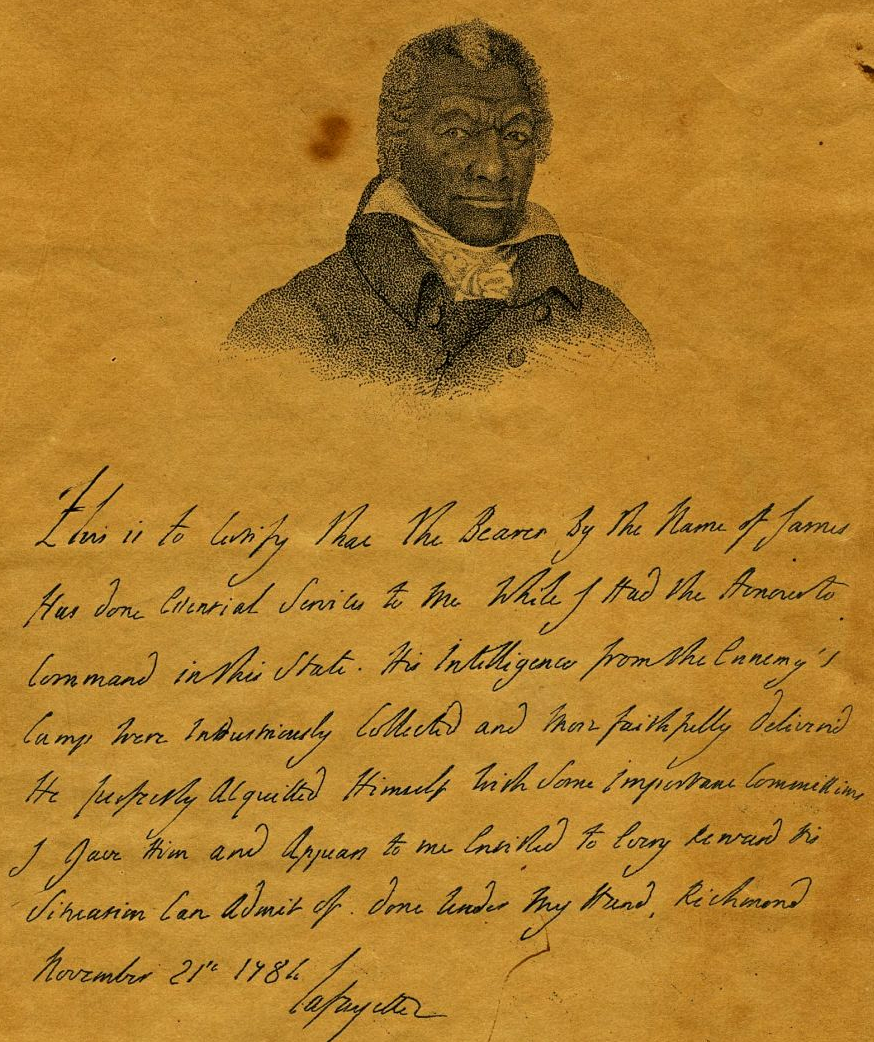

Lafayette had his own enslaved man working as a double agent, and he managed to earn his freedom by serving as a spy for the Revolutionary cause. James was granted permission by the New Kent County planter who "owned" him to leave the plantation. He worked in Yorktown at Cornwallis' headquarters in 1781, and both sides allowed him to pass through the lines as a laborer. James shared information with British officers about the French and American activities, but he was operating as a double agent. He reported more valuable intelligence, gathered from listening to dinner discussions by those officers, to the Marquis de Lafayette.

Lafayette provided support to James in 1784 when he petitioned the Virginia legislature for his freedom. The General Assembly rejected that petition, but approved another request when submitted in 1786. James chose to call himself James Lafayette and stayed in Virginia. He ended up owning land in New Kent County, and in 1818 the General Assembly awarded him an annual pension in recognition of his wartime service.12

in 1784, General Lafayette certified the service provided by "James" in 1781

Source: Luther P. Jackson, Virginia Negro Soldiers and Seamen in the Revolutionary War (p.9)

Peter Salem, released temporarily from slavery to fight in the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill, fired the shot that killed British Major John Pitcairn. However, at the start of the American Revolution white leaders such as George Washington were opposed to recruiting black men. Within two years, as the need for soldiers grew, that opposition faded.

John Trumbull included Peter Salem in his painting "The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill"

Source: National Museum of African American History and Culture, Peter Salem and the Battle of Bunker Hill

Rhode Island led the way in guaranteeing freedom, since the smallest state had so few white men from which to recruit. The 1st Rhode Island Regiment began accepting enslaved men in February 1778. Recruits were emancipated immediately, and slaveowners were compensated for the loss of their "property." That arrangement was cancelled after six months, but the regiment continued to recruit free blacks and is honored today as the first black battalion in the United States.

Throughout the 13 colonies, as many as 15,000 enslaved men may have joined the Continental Army or a state militia in order to fight against the British. Only Georgia and South Carolina refused to allow enslaved men to enlist.

The motivation for fighting on the American side was individual rather than political freedom. The enslaved soldiers anticipated that they would be emancipated when the Americans won independence. Virginia legislators ensured that former masters were unable to re-enslave 500 veterans after the American Revolution.

Based on reports by observers, roughly 10% of the 150,000 American soldiers who served during the Revolutionary War were black. They created a racially integrated American army that was not seen again until the twentieth century. At one point, British forces considered selling into slavery those black American soldiers who were captured, in order to deter blacks from enlisting with the "rebels."

The numbers are questionable. There are few official records and only 500 applications for pensions from formerly enslaved men. By the time soldiers could apply for pensions, racism stimulated by slave revolts had increased. Many black soldiers did not return to their home communities, so finding witnesses to testify that a person deserved a pension was hard.

Luther P. Jackson, the first black historian to estimate the number of free and enslaved Virginians who fought against the British in the Revolutionary War, estimated that at least 150 and as meny as 500 such men enlisted in a Virginia military unit. Some chose to serve voluntarily, some were drafted, and others were "sustitutes" for white men. Constraints on enlisting men of color faded as the war continued and recruitment for Virginia militia and the Continental Army became more difficult. As demonstrated by the service of Billy Flora at Great Bridge, the restriction against allowing blacks to carry guns was not followed even in 1775.13

some of the enslaved Virginians seeking to join Lord Dunmore were captured before they reached British lines

Source: Library of Virginia, List of prisoners brought to Williamsburg, 1776 June 2

Lord Dunmore was the first British official to offer enslaved Virginians a chance to gain their freedom by fighting against the American rebels. Sir Henry Clinton issued an expanded version of Dunmore's Proclamation from his base in New York in 1779. The Philipsburg Proclamation granted freedom to anyone who could reach territory controlled by the British. Clinton sought to recruit black soldiers, but disrupting the economic capacity of the rebels was enough justification to offer freedom.

General Clinton stated in the Phillipsburg Proclamation:14

The British commitment to ensuring freedom was limited. When the British attempt to capture Charles Town, South Carolina failed in 1779, hundreds of black soldiers were abandoned because there was not sufficient room for the army's return to Savannah. Historian Woody Holton reports:15

In October, 1781, at the end of the American Revolution, Cornwallis forced many of the blacks still with his army to move outside of his protected perimeter. They had to hide from the bombardment of Yorktown in the small no-man's land between the British and American/French lines, or accept re-enslavement by surrendering to the Americans.16

Holton concluded:17

Cornwallis sought to protect the black refugees he still had within his lines when he surrendered and proposed Articles of Capitulation to Washington. Washington rejected the effort to protect them. Article X, the only item that Washington completely rejected, proposed:18

When the British evacuated New York, they carried away many formerly enslaved blacks who had fled to freedom. In that group were former members of Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment who had been incorporated into the Black Pioneers, which had been organized by General Henry Clinton.

Most of the New York loyalists were transported in ships to Nova Scotia in 1783. Officials there compiled the Book of Negroes to document the arrivals of the black refugees. American officials monitoring the evacuation in New York created an equivalent register that recorded the names of people who embarked. A sugnificant number of the black refugees in Nova Scotia were unhappy at their treatment there and later migrated to Sierra Leone in Africa.19

In South Carolina, the British created the Black Pioneers in 1776 and then the Black Dragoons, a cavalry company that scouted and raided around Charles Town. It seized supplies, captured deserters, and carried away enslaved workers from the plantations of Patriots. When the British evacuated Charles Town in 1782, they combined the Pioneers and Dragoons to create the Carolina Corps and stationed thenm on the island of St. Lucia in the Caribbean.20

In the War of 1812, the British once again recruited enslaved Virginians to flee to their ships and organized them to fight the Americans. Tangier Island was the base for training the Corps of Colonial Marines in that war.21

James served as a double agent in 1781, feeding information to British officers but actually serving as a spy for the Marquis de Lafayette

Source: Library of Virginia, the UnCommonwealth blog Two Revolutionary War Petitions (March 9, 2022)

enslaved men could earn their freedom by joining Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment, while only free blacks were enlisted directly into the Continental Army

Source: Library of Congress, Life of George Washington--The farmer