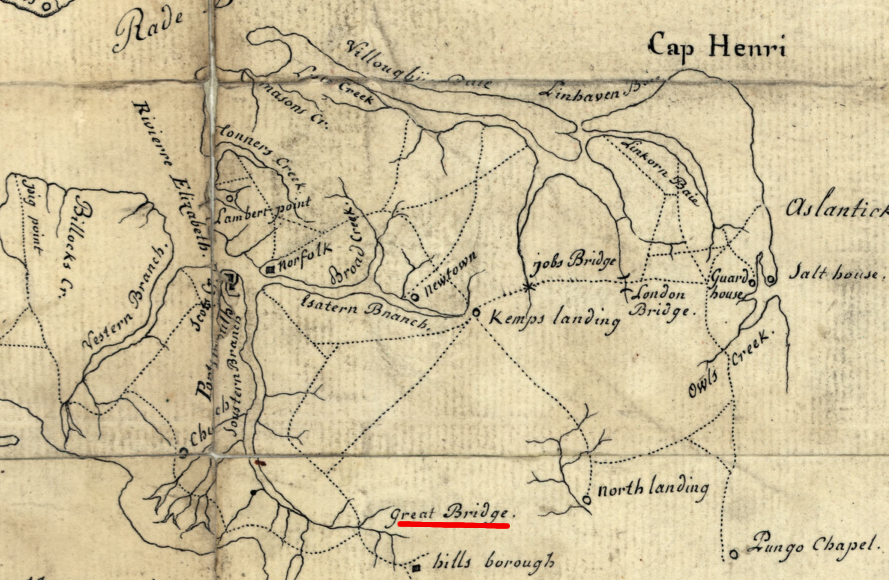

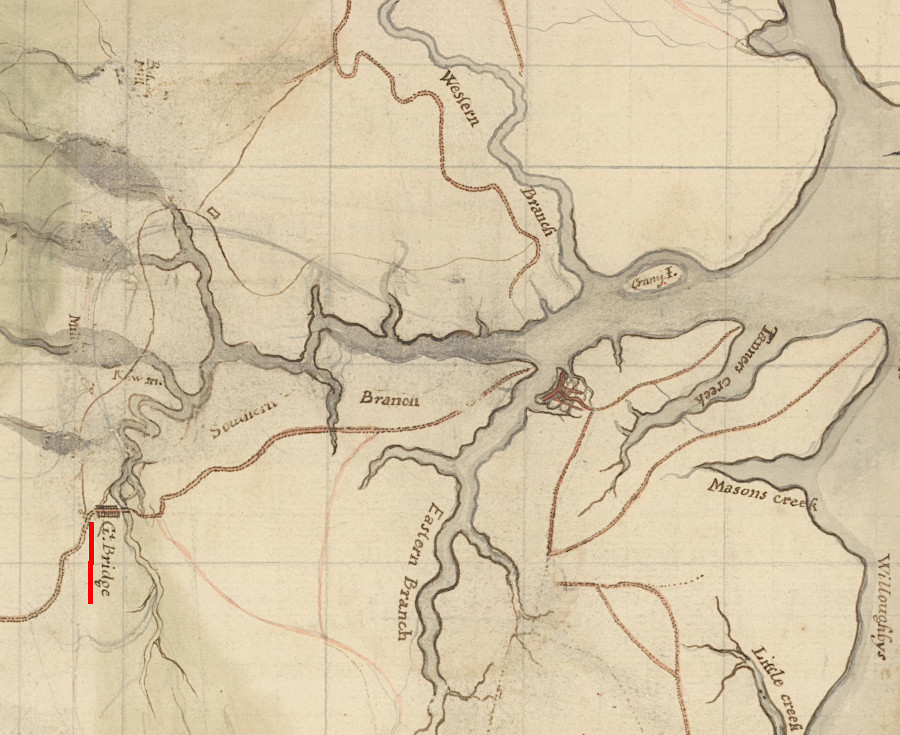

French engineers in 1781 mapped the location of Great Bridge, south of Norfolk

Source: Library of Congress, Plan des environs de Williamsburg, York, Hampton, et Portsmouth (1781)

French engineers in 1781 mapped the location of Great Bridge, south of Norfolk

Source: Library of Congress, Plan des environs de Williamsburg, York, Hampton, et Portsmouth (1781)

At the time of the American Revolution, Great Bridge was the only place where people could cross the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River on foot.

the British controlled the waterways in 1775, so the only way for the Virginians to recapture Nortfolk was to march on foot past Great Bridge

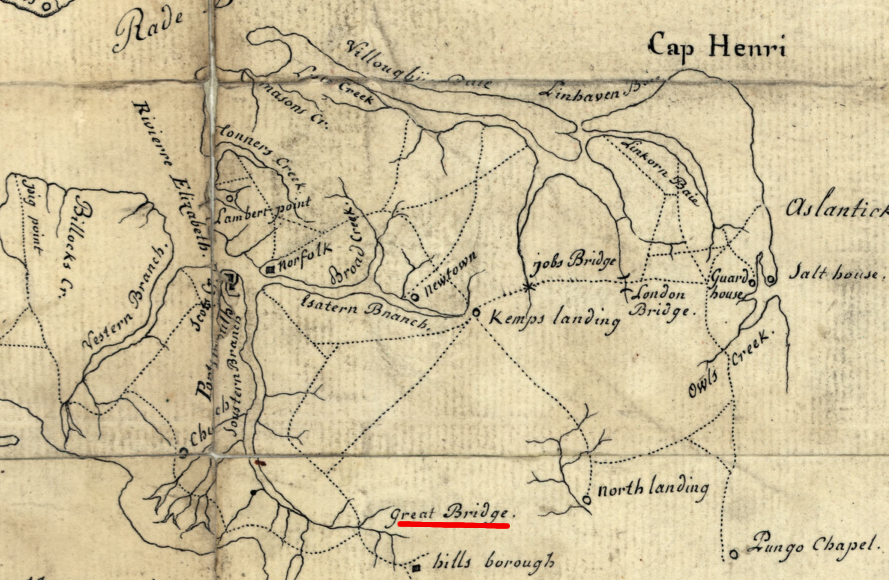

Source: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library, Plan of the peninsula of Chesopeak [sic] Bay (by John Hills, 1781)

Captain Johann Ewald, who commanded Hessian troops in the area in 1781, described its significance to control of the region:1

the roads connecting Norfolk with Suffolk and North Carolina passed through Great Bridge

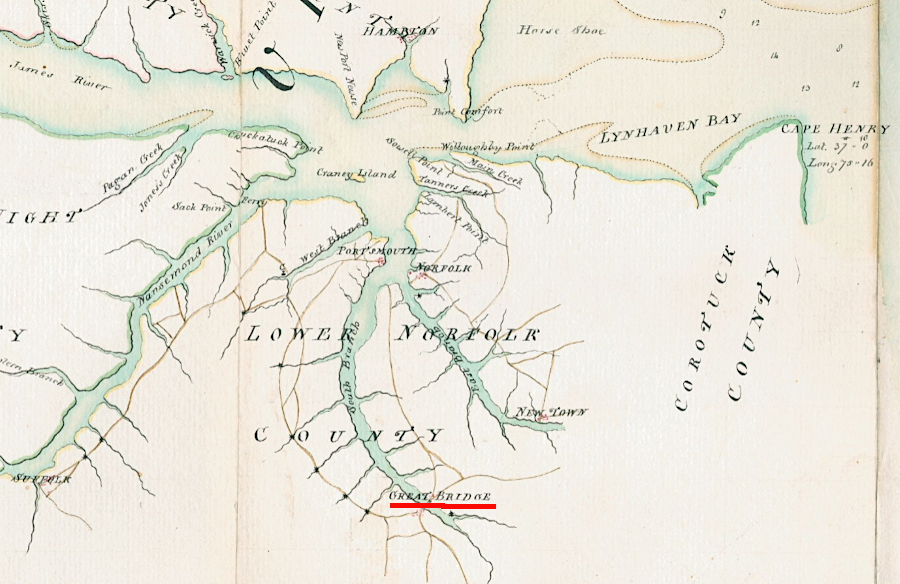

Source: Library of Congress, A Plan of the entrance of Chesapeak Bay, with James and York rivers (by William Faden, 1781)

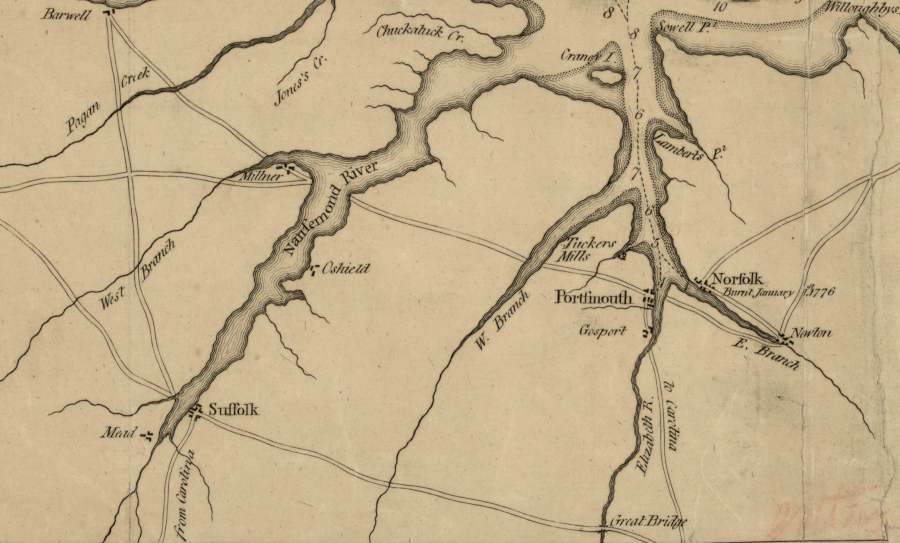

the road between Suffolk and Norfolk passed through Great Bridge in 1776

Source: Library of Congress, Part of the Province of Virginia (1791?)

On June 8, 1775, Lord Dunmore fled Williamsburg. He later occupied Norfolk and declared martial law on November 7, establishing a British base. Virginia Tories could rally to the king's standard and join the Queen's Own Loyal Regiment to fight against the rebellious "patriots." Dunmore also recruited enslaved men to join his Ethiopian Regiment.

The British built Fort Murray at the northern end of the bridge, with cannon. They removed the planks from the bridge to block a rebel advance into Norfolk 12 miles away.

After a skirmish at Kemp's Landing between the British and the Princess Anne County militia on November 15, the main body of British troops occupied Fort Murray. About 800-1,000 rebel soldiers, including the Second Virginia Regiment led by Gen. William Woodford, arrived at the south end of the causeway in early December 1775.

There were just 175 British regulars to oppose them, but the British grenadiers and the light infantry from the 14th Regiment were better trained and better equipped. In addition, the less-trained men in the Ethiopian Regiment and the Queen’s Own Loyal Regiment added firepower. The British force was formidable enough to block an American advance.

The British could have accepted a stalemate with troops behind barricades blocking either side from moving forward. The British supply line was more reliable, and the Americans might not be able to maintain their Second Virginia Regiment and other troops at the southern end for long. Instead, the British planned to overwhelm the Virginia troops by first launching a diversionary attack nearby, then charging across the bridge.

![. A stockade Fort thrown up before the action by the Regulars. B. Entrenchments of the Rebels. C. A [illegible word] Causeway by which the Regulars were forc'd to advance to the attack. D. The Church occupied by the Rebels](graphics/greatbridge1775.jpg)

A. A stockade Fort thrown up before the action by the Regulars. B. Entrenchments of the Rebels. C. A [illegible word] Causeway by which the Regulars were forc'd to advance to the attack. D. The Church occupied by the Rebels

Source: William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, A view of the Great Bridge near Norfolk in Virginia where the action happened between a detachment of the 14th Regt: & a body of the rebels. (by Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Marquess of Hastings)

Plans for the diversionary attack were dropped, and on the morning of December 9 the planks were replaced. Captain Charles Fordyce led a bold charge over the bridge and down the causeway to attack the rebels.

American sentries fired on the advancing British Grenadiers, marching six men abreast. One sentry was a free black man named William "Billy" Flora, credited with firing eight times and being the last sentry to retreat into the American fortifications. Supposedly he removed the last planks from the bridge, helping to disrupt the British attack - which included members of the Ethiopian Regiment.

Flora later received a 100-acre bounty land warrant for his service throughout the Revolutionary War. He remained a member of the Portsmouth militia, serving when he was 52 years old, and was still in the home guard in 1812 when the British attacked Craney Island.

Woodford's men had not expected an attack; they initially thought the firing was a routine skirmish. The Virginia "rebels" waited behind their fortifications until the British soldiers were within 50 yards, then began firing.

Within 30 minutes half of the unprotected attackers, including Captain Fordyce in the front, were killed. One American described the carnage:2

The Americans then advanced on the flank of the fort, which made the British cannon ineffective. After spiking their cannon, the British abandoned Fort Murray and retreated to Norfolk. Just one American was wounded, while 60-100 British were killed, wounded, or captured.

The first significant battle in Virginia between the rebels and the British army ended up as an American victory. The loss of Great Bridge made Dunmore consider Norfolk to be indefensible. He moved his troops and Loyalist friends to Portsmouth, and onto ships in the Elizabeth River.

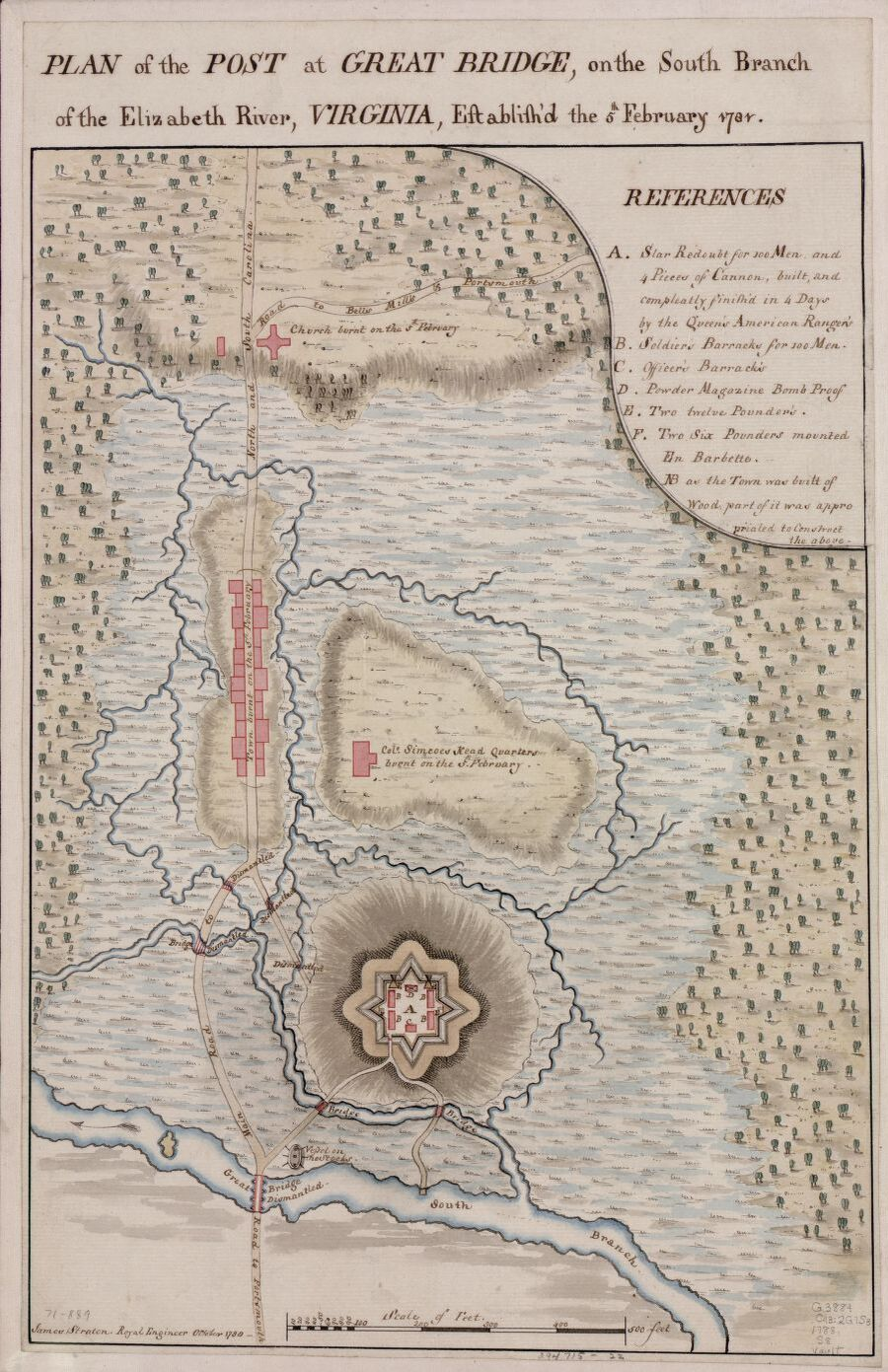

Lord Dunmore had Fort Murray constructed at Great Bridge in 1775, to control access to Norfolk

Source: Library of Congress, Part of the Province of Virginia (1791)

The force of Virginia militia and North Carolina Continentals, who arrived three days after the battle at Great Bridge, was inadequate to create a defensible Patriot base at Norfolk. Dunmore lacked the capacity to recapture the city.

On January 1, 1776 he directed that cannons on the British warships shell Norfolk. Their 100 cannons, firing from 3:00pm on January 1 to 2:00am on January 2, made the city useless for the Virginians to establish a military base there. The Virginians then completed the job of destroying the colony's largest trading and economic center, burning the remaining structures in Norfolk that had survived the cannonade. A later assessment calculated that the Patriot forces caused 96% of the damage, but for the next 200 years the British were traditionally blamed.

Norfolk was a community with a high percentage of free blacks, Scottish merchants, and loyalists among the 6,250 residents. Victory at Great Bridge was key to the patriots (or rebels, depending upon your point of view) making it hard for the British to base their fleet of warships at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay.

The absence of British forces in Virginia after Governor Dunmore's retreat suppressed the ability of loyalists to gain control of local county courts at the start of the American Revolution. Patriot domination in Virginia, and the inability of the British to occupy a major city as the base for controlling a colony with a dispersed population, facilitated recuitment of Virginians to serve in the Continental Army:3

However, Portsmouth was not destroyed by either side.Portsmouth rather than Norfolk became the site for future British occupations in 1779-81. The shipping channel at Portsmouth, unlike Norfolk, was too shallow for the largest British warships. When Lord Cornwallis brought his army to Hampton Roads in September 1781, he briefly occupied Portsmouth. He ended up moving to Yorktown, judging it a better port than Portsmouth for receiving his expected reinforcements via ships sailing from from New York.

When Benedict Arnold occupied Portsmouth in 1781, he wanted to control access to the cattle, crops, and other resources in Princess Anne County. He sent Col. John Simcoe and the Queen's Rangers back to Great Bridge, after learning that some of his foragers had been attacked there. The British constructed another star fort to control the passage across the South Branch of the Elizabeth River. For labor, they used 300 formerly enslaved people who had fled from their Virginia masters to freedom within the British lines. About 100 men from the 80th Regiment occupied the fort after it was built.4

During construction, Virginia militia fired at the workers and the guards. The British made a dummy, dressed it in a uniform, and posted it as a "sentinel" guarding the approach to the incomplete fort. The rebels fired on the dummy, but the next day it was shown to a Virginia officer who came under a flag of truce. After a discussion about the waste of life from killing sentinels when no attack was planned, the militia stopped that harassment.

Col. Simcoe described the fort's strengths and weaknesses after the war:5

There is now a museum and historic signage in the city of Chesapeake at the site of the Great Bridge. The British attack is reenacted annually. As described in a 2022 news story:6

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia, EntryPoint Presents: The Battle of Great Bridge

in 1775, travelers coming from the west by land to Norfolk had to cross Great Bridge

Source: University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library, Part of the modern counties of Princess Anne, Norfolk, and Nansemond, Virginia

Col. John Simcoe returned to fortify Great Bridge in 1781 when Benedict Arnold occupied Portsmouth

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the post at Great Bridge, on the south branch of the Elizabeth River, Virginia, establish'd the 5th February 1781 (by James Stratton, 1788)