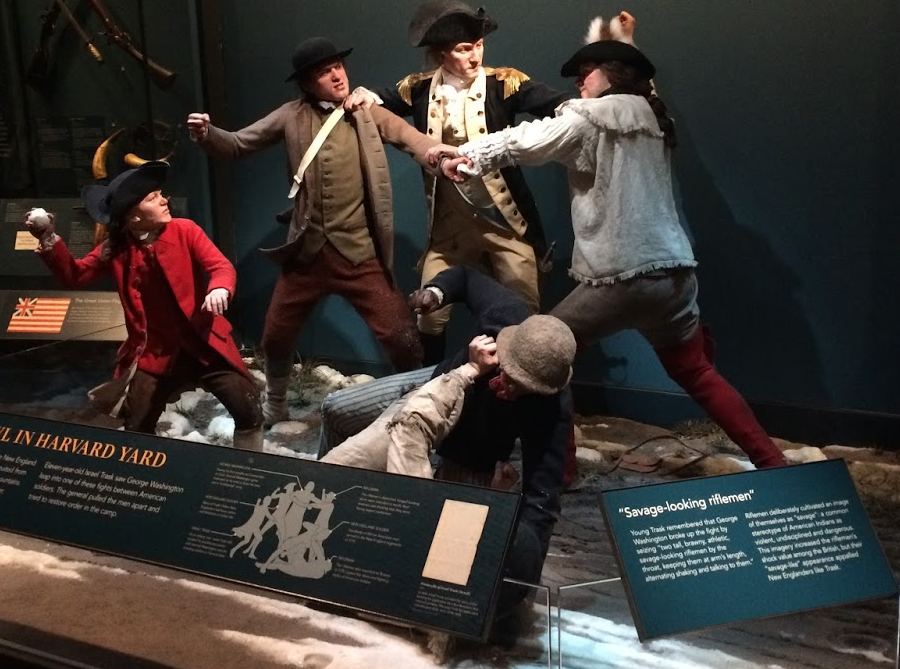

in creating a Continental Army from troops loyal to individual states, George Washington personally broke up at least one brawl

(as displayed at Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia)

in creating a Continental Army from troops loyal to individual states, George Washington personally broke up at least one brawl

(as displayed at Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia)

The Revolutionary War may have been another one of those "rich man's war, poor man's fight" - but many Virginians did fight. They were recruited to serve initially in the First Virginia Regiment. Additional regiments were raised, and then many were transferred to the emerging "national" Continental army - where they served outside of the new state, in the northern colonies and then in South Carolina.

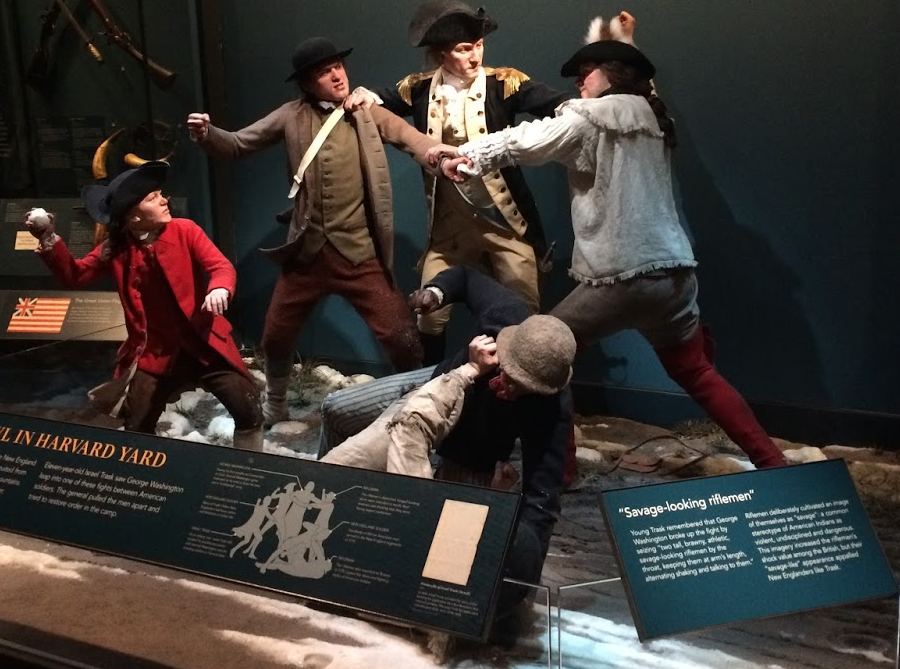

George Washington was given command of the first army composed of troops from multiple colonies rebelling against British control. At the Continental Congress, he had not-so-subtly dressed in his old French and Indian War uniform while members debated who was trustworthy enough to lead the military forces, but not likely to become a dictator in the process.

Washington was elected unanimously by the Continental Congress, but he acknowledged that there was a political motive in his selection as well as recognition of his personal capabilities. In August, 1774, prior to the start of the First Continental Congress, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania delegates agreed to let the Virginia delegates take the lead in decisions leading to independence. The Virginians were recognized as less willing to break free from British rule, so their support would have greater influence with other colonies. In addition, the Virginia delegates were seen as so proud of their heritage that having other colonies take the leadership role in advocating for independence would make the Virginians even more reluctant.

As a result, John Adams declined to support the desire of fellow Massachusetts residents John Hancock and Artemas Ward to be appointed Commander in Chief. Adams recognized appointing Washington would help unite southern and northern colonies in a common cause. In addition to selecting George Washington as the Commander in Chief, the other delegates granted Virginia delegates an excessive number of key roles in the Continental Congress. Peyton Randolph was elected as president of the First Continental Congress, Richard Henry Lee made the motion to declare independence, and Thomas Jefferson was chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence.

a Virginian was selected to command the Continental Army in an effort to unite the colonies

Source: Library of Congress, Continental Congress to George Washington, June 19, 1775, Commission as Commander in Chief

On June 23, 1775 George Washington left Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress was meeting, to take command of the Army of Observation around Boston. He did not get back to Virginia for six years. He stopped at Mount Vernon on the march to Yorktown in September, 1781. His wife Martha managed to join him for winter camps, providing some moral support to the troops as well as to her husband.1

George Washington met the troops of the new Continental Army on July 3, 1775

Source: Library of Congress, Washington taking command of the American army under the old elm at Cambridge

The path to independence may have started with colonial dissatisfaction with British policies after the French and Indian war, but the shooting war started on April 19, 1775. Militia at Lexington and Concord either opened or returned fire on the King's soldiers. At the end of the day, 273 British and 95 Americans were dead. Americans then entrenched on Breed's Hill outside Boston, and threatened to install artillery that would force British troops to abandon the city. The Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775 made clear that the British would need to send a large number of additional troops to North America in order to win a military victory.

The British had anticipated that it could suppress the rebellious colonists in Massachusetts without stimulating the other 12 colonies to join in a united effort. However, the 13 colonies that chose to rebel (about half of all British colonies at the time) managed to work together. They had been operating as rivals since each colony was established, competing with each other for trade, influence with Native American tribes, and control of western lands. The colonies failed to coordinate militarily with each other during the French and Indian War in 1754-1763.

On the political front, elected delegates at the Continental Congress managed to organize an army, select generals, borrow/print money to finance a war, and ultimately adopt Articles of Confederation that created a new national government.

The colonies already had policies and procedures for raising militia companies. Establishing a Continental Army required being innovative. Generals were chosen only after politicking among the separate interest groups within the Continental Congress. At times, Horatio Gates and others thought they should be appointed to replace George Washington.

On the national scale:2

After the Massachusetts militia fought with British regulars on April 19, 1775 at Lexington and Concord, on June 14 the Continental Congress authorized recruiting men to form 10 rifle companies and forming a national army. Six companies were to be formed in Pennsylvania, two in Maryland, and two in Virginia. Assembling a military force from other colonies to support Massachusetts started the formation of a Continental Army under the control of a new national government.

The two companies raised in Virginia came from the Shenandoah Valley. Captain Hugh Stephenson organized one company at Morgan Spring in Berkeley County (near Mecklenburg, now called Shepherdstown, in West Virginia). Captain Daniel Morgan (not related to the family for whom Morgan Spring was named) recruited the second company at Winchester in Frederick County.

Morgan's company started marching north on July 15; Stephenson's company left two days later on July 17. Captain Daniel Morgan reportedly ignored an agreement with Captain Hugh Stephenson to march together to Boston. Morgan left early and the two raced to become the first to arrive.

Both units made a "beeline march" on the 600 miles to Boston, walking up to 36 miles a day while carrying guns, lead bullets, powder, bedrolls, and other supplies. The two companies obtained food and shelter from local residents in almost half the colonies before reaching Boston on August 11.

Morgan's company reached the New England forces besieging Boston five days before Stephenson's company. George Washington was there to greet them as commander of the American forces. Morgan Spring (which is different from Morgan Grove Park in Shepherdstown) is now cited as the birthplace of the US Army.3

The Continental Army was organized by state; the Virginia troops were in the Virginia Line. Almost all Virginians serving in the Continental Army in 1780 were captured in the disastrous surrender by General Benjamin Lincoln of over 5,000 men in the Continental Army and militia at Charles Town (later Charleston), South Carolina.

Two major units on Virginians in the Continental Army had not reached Charles Town in time to join in the defense, and ultimately the surrender. Colonel Abraham Buford commanded the Third Virginia Detachment, and Lt. Col. Charles Porterfield commanded the State Detachment.

Though they were not with General Benjamin Lincoln's army at Charles Town, few of those Virginians managed to return to Virginia in 1780. Both units were destroyed in other American defeats soon after Charles Town. One commentator has noted:4

During the Revolutionary War, Virginia supplied 15 regiments to the Continental Army between 1775-1783. The state also raised troops for a "State Line" and a Virginia Navy. All white males between 16 to 50 years old were automatically included in the standard county militia. No enlistment or recruitment process was required to get them to become part of the militia, but promises of pay and land grants (and finally a draft) was used to recruit men to join the State Line and the Virginia Line in the Continental Army:5

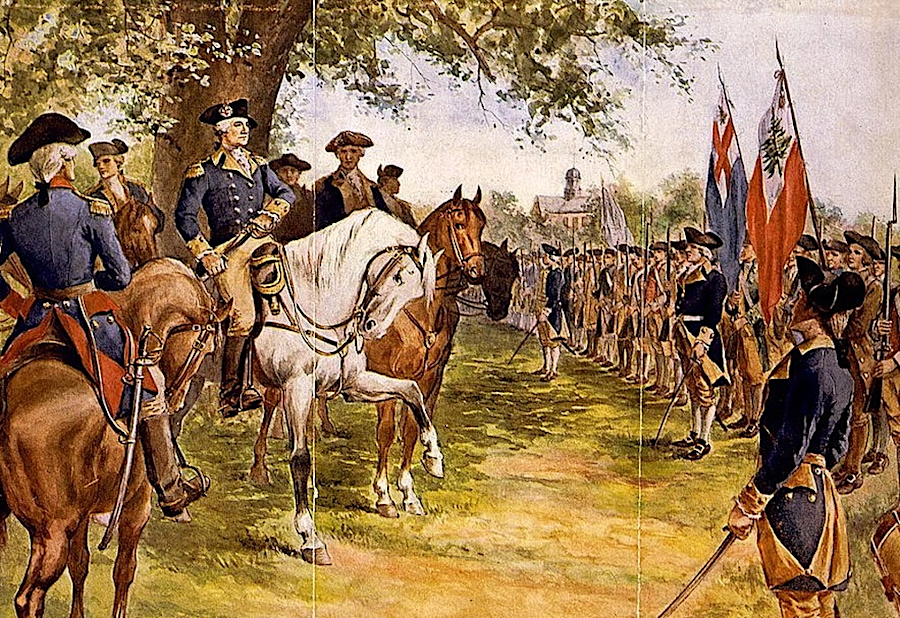

the Continental Army was created in the Revolutionary War when the county-based militia were not sufficient

Source: National Park Service, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, Virginia Militia in the Second Line

The General Assembly offered a bounty in 1779 in order to entice enlistment for the duration of the war in either the state troops or the Continental Army:6

Colonel Abraham Buford led the Third Virginia Detachment, with two companies of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and 40 Virginia Light Dragoons, towards Charleston in 1780. Those 380 Virginians were coming as reinforcements, but began to return to Virginia after learning of the General Lincoln's surrender.

Buford marched north too slowly. Mounted infantry ("dragoons") in Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton's British Legion dragoons caught up with the Virginians at Waxhaws, near the border of North Carolina and South Carolina. Col. Buford had a week's head start, but Tarleton was more aggressive.

Buford rejected Tarleton's demand to surrender without fighting. The Americans fired one volley and then tried to surrender, but Tarleton rejected the request. The British dragoons, using sabers and bayonets, won an overwhelming victory, killing/wounding 300 Americans at the cost of just 20 British killed/wounded.

Buford immediately claimed in his official report that many of his men who had surrendered were killed without mercy. His account is suspect, however, because Buford fled from Waxhaws after Tarleton refused his surrender request and the American forces were being slaughtered.

Tarleton reported after the battle that his horse was shot and he was pinned on the ground, and at that time some of his troops acted with "vindictive asperity." Tarleton sought medical care for all the wounded after the battle at Waxhaws, suggesting that Tarleton never issued orders to kill those who had surrendered. It is possible that some British soldiers had killed a few prisoners, when they thought their Lieutenant Colonel had been attacked after the Americans had surrendered.7

Whatever the facts, American propaganda about a Waxhaws Massacre and the threat of loyalists raiding into Virginia succeeded in rousing volunteers. The Overmountain Men, members of the militia, mobilized and marched across the Blue Ridge to defeat loyalists fighting under Major Patrick Ferguson at the Battle of Kings Mountain in October, 1780.

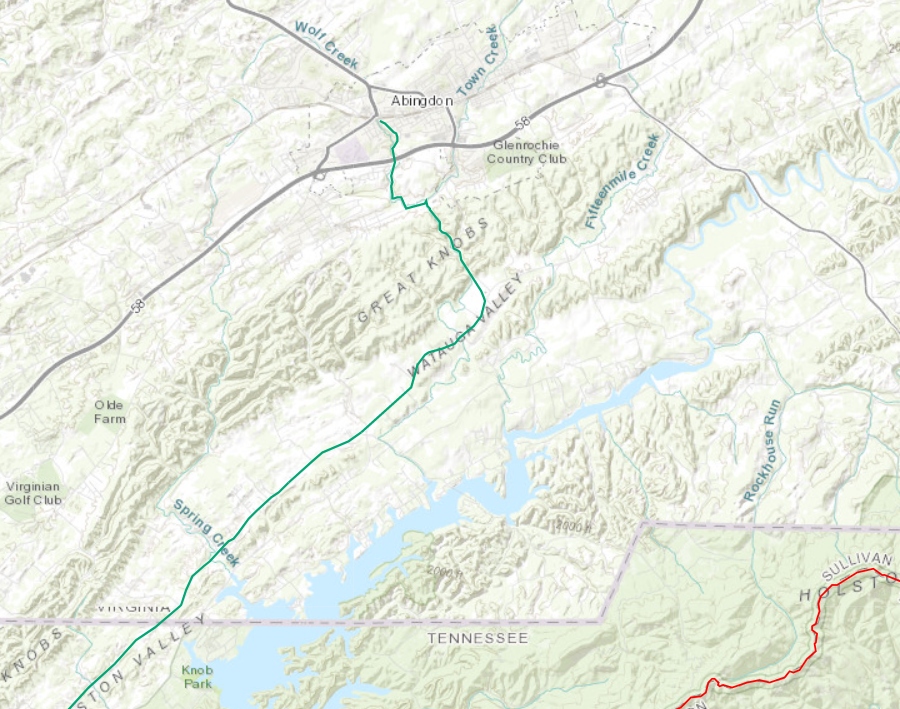

Overmountain Men in Virginia gathered at Abingdon, now a starting point on the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail (red line is Appalachian Trail)

Source: National Park Service, National Scenic and National Historic Trail Webmap

Attracting soldiers to serve in the state army and the Continental Army got harder as the war progressed. Militia duty allowed men to continue to work their farms, unless the militia was called into action in the summer. Serving in the state army involved a longer time commitment, but did not normally include the risk of being sent far away to fight in another colony.

The Virginia General Assembly passed a new recruitment law on January 1, 1781, at a time when the British Army was marching along the James River. A unique provision in the law had been discussed before Gen. Alexander Leslie had seized Portsmouth, and before Gen. Benedict Arnold arrived with a new set of British troops. The recruitment act promised to give each recruit:8

The bill assumed that men who owned 20 or more enslaved workers would have to provide the bounty, because there were few loyalist estates from which enslaved workers could be confiscated. The General Assembly members were struggling to identify a valuable inducement to attract enough soldiers so a forced draft would not be required to fulfill the manpower requirements. A cash bounty was not a strong enticement because inflation rapidly reduced the value of money. Land bounties were of questionable value. If the British won the war, no land would be granted. If the Americans won, the logistics of claiming the land could take years.

The initial proposal was to provide an enslaved worker at the time of enlistment; that would have allowed the family of a recruit to obtain a replacement worker. The reward was weakened when the bill was amended so the enslaved worker would be provided only at the end of the war.

The new recruitment bill with an offer of an enslaved person for every soldier was never implemented, for reasons not recorded in the journals of the General Assembly. Baron von Steuben notified George Washington of the proposal, but his letter in response dealt only with other matters. By the start of 1781, recruits from wealthy families who already owned enslaved people were thin. Most likely, soldiers who joined in 1781 were relatively poor. Had each been given an enslaved person as a bounty, slavery would have been extended across a higher percentage of Virginia households.

In contrast to Washington, James Madison addressed the proposed bounty when he responded to the person who alerted him about the proposal. His reply was consistent with the ideals of fighting for liberty:9

The Marquis de Lafayette struggled to acquire a large enough force to fight General Cornwallis as the British marched through Virginia in 1781, before ultimately ending up at Yorktown. Lafayette asked Governor Nelson to help offset the high rate of desertion from Lafayette's army by creating a unit of black soldiers who could clear roads and do engineering work as "pioneers." He asked for Virginia to create:10

Unlike Governor Dunmore, who created an Ethiopian Regiment in 1775, the General Assembly declined to arm black men. The legislators - who had to flee Richmond for Charlottesville, and then Charlottesville for Staunton as General Cornwallis approached the cities - feared setting the stage for a slave revolt more than they feared the British.

When George Washington arrived in Boston in July 1775, he expelled the black men who were serving in the Army of Observation. As a Virginia slaveowner, he had a bias against arming black men. However, the enlistment time of Washington's troops was limited. He constantly needed to recruit more men. Rhode Island was willing to enlist black slaves and grant them freedom, in exchange for serving in the Continental Army.

After Lord Dunmore recruited his Ethiopian Regiment, George Washington allowed free blacks to enlist in his army. Rhode Island provided the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, the "Black Regiment."11

Using black men as soldiers within predominantly-white units and as spies was acceptable. The owner of James Armistead authorized him to enlist in the Lafayette's army in 1781. Armistead was initially Lafayette's personal servant, but then pretended to desert to the British. He ended up as a double agent, pretending to spy for the British. James Lafayette provided key information about Cornwallis's plans to move his base from Portsmouth to Yorktown, enabling George Washington to quickly respond and march south in time to trap the British army.12

Over the course of the war, 231,000 men served in the Continental Army. George Washington never had more than 48,000 soldiers to command at any one time, indicating how much he had to replace soldiers by recruitment. The most men organized for a single battle by the Continental Army was 13,000.

An additional 12,000 French soldiers provided assistance to the Americans.

On the British side, the army peaked with 22,000 Regulars at one time. Scattered among the 13 colonies were another 25,000 or so loyalists. About 30,000 hired German troops also came to North America.13

Daniel Morgan (in white uniform near front of cannon) led Virginia riflemen that targeted British officers successfully and led to the surrender of British General John Burgoyne's army at Saratoga, New York on October 17, 1777

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Surrender of General Burgoyne (painted by John Trumbull)

George Washington returned to private life at Mount Vernon after leading the Continental Army from 1775-1783 during the American Revolution

Source: Architect of the Capitol, General George Washington Resigning His Commission