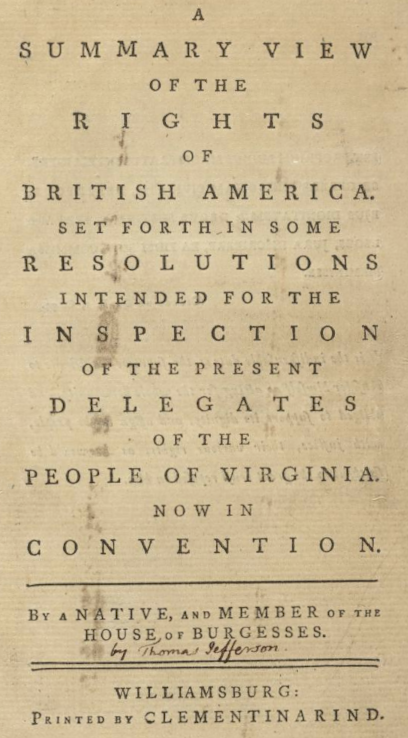

Thomas Jefferson claimed in 1774 that "the British Parliament has no right to exercise authority over us"

Source: Library of Congress, A summary view of the rights of British America...

Thomas Jefferson claimed in 1774 that "the British Parliament has no right to exercise authority over us"

Source: Library of Congress, A summary view of the rights of British America...

Many members of the House of Burgesses and the Governor's Council became radicalized between passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 and the First Virginia Convention in August, 1774. The elite clique of white men who controlled the economy and enjoyed high social status in the colony risked their power and position to rebel against the authority and military capacity of Great Britain.

American colonists were loyal supporters of the British empire at the end of the French and Indian War in 1763. Over the next dozen years, leaders developed a strong perception of unfair treatment by British officials. Many colonial leaders came to believe that London officials planned to drain the wealth of Virginia, Massachusetts, and the other colonies to enhance the standard of living across the Atlantic Ocean, as new taxes were added to the traditional mercantile policy. If Parliament or King George III would not respond to the concerns of the colonists, then separation from Great Britain would be necessary.

Parliament was deeply angered by the Boston Tea Party. Mob rule could not be tolerated; closure of the port of Boston and other Coercive/Intolerable Acts demonstrated that law and order had would be restored. In the House of Commons, the vote to revoke the Massachusetts charter (one of the Coercive/Intolerable Acts) in an attempt to force compliance passed by 239-64. Charles Fox opposed the bill, and framed the policy choice clearly during debate:1

London officials chose to use force to implement their policies rather than negotiate to accommodate the interests of the American colonies. The fundamental mistake 3,000 miles away from North America was the belief that a small number of radicals concentrated in Massachusetts could be supressed.

The presumption was that a strong demonstration of force against Boston would create the fear among the mass majority of loyal colonists that they could be next. That fear would trigger compliance with the tax on tea, and whatever other policies were issued by royal officials. Instead, the Coercive/Intolerable Acts radicalized leaders in all colonies. The fear of imperial power exposed that only a small minority were willing to support unconstrained power of the king and Parliament.

Approximately 20% of the white colonists were loyalists. Perhaps 45% of whites ended up supporting independence, and many men joined state forces and the Continental Army and risked their lives to fight against the British.

Those who tried to live their lives without choosing sides were pressured to comply with the orders of the Committee of Safety. The pressure to comply with the non-importation agreement adopted at the First Continental Congress was social and economic initially, but as the American Revolution continued physical violence became common between loyalists and "patriots." A month after open fighting at Lexington and Concord, General Thomas Gage in Boston advised London that the opposition to royal government was widespread, not limited to just Massachusetts:2

a Williamsburg merchant was threatened by tar and feathers hanging from a pole outside the Raleigh Tavern, forcing him to sign the non-importation agreement

Source: Museum of Modern Art, The Alternative of WIlliams-Burg (attributed to Philip Dawe, 1775)

Enslaved people given the opportunity to flee to British ships or armies demonstrated that they were advocates for freedom, but interpreted the British as the side which offered it. Native American groups did not choose sides based on philosophical questions such as "taxation without representation."

Some chose to support the British or the rebelling colonists based on previous relationships between leaders where trust had been established. Others supported one side because they saw an economic advantage, anticipating gifts or the protection of hunting grounds. Native American allegiances could shift during the war, particularly when troops of one side or the other posed an imminent threat.3

Members of the Virginia gentry were leaders in the philosophical debates. In the summer of 1774, after Lord Dunmore had dissolved the House of Burgesses and the extra-legal First Virginia Convention was preparing to appoint Virginia's representatives to a Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Thomas Jefferson sent his ideas to the convention in Williamsburg. He said boldly in A Summary View of the Rights of British America that it was time to renounce the authority of Parliament. Jeferson also blamed King George III for the conflict, at a time when other politicians were limiting the blame to Parliament and trying to gain the support of the king.

Jefferson was delayed in arriving at the First Virginia Convention due to a bout with dysentery. Without him there in person to argue for his ideas, a majority of the convention delegates meeting on August 1-6, 1774 remained unwilling to approve what he proposed. However, some of them raised the money among themselves and funded publication of A Summary View of the Rights of British America anonymously.

When the Second Continental Congress needed someone in June 1776 to draft a statement about why 13 colonies were renouncing the authority of Great Britain, Jefferson's pamphlet from two years earlier provided a clear guide for what needed to be said. He was chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence.

From a political perspective, the American Revolution was won with pamphlets before first shot was fired in 1775. The shooting finally drained Britain's willingness to fight against independence. Within 18 months after overt military conflict erupted at Lexington and Concord, individual colonies created legitimate forms of government, based on votes by residents, to replace the traditional colonial structures based on the authority of a monarch.

At the national level, there was inter-colonial government starting in 1774. Cooperation between the colonies focused initially on support of the Continental Army. Creating a civil government without a monarch turned out to be very difficult.

The American colonists who first tried to implement representative government, a democracy rather than a monarchy or dictatorship, struggled to find the right structure to balance the interests of different states. The national government was largely ineffective until the Articles of Confederation were replaced in 1789 with a new US Constitution.

Loyalty was not guaranteed even after 1789. Settlers west of the Allegheny Front might decide their economic interests were closer to whatever government controlled trade on the Mississippi River and choose to ally with Spain or France, rather than stay part of a United States that was dominated by the eastern states with Atlantic Ocean ports.

George Washington generated a major military response to the Whiskey Rebellion in 1795. That was designed to impress upon western settlers that they must comply with policies issued by the national government, a slightly ironic response from the leader of the Continental Army that blocked London from imposing its policies on 13 colonies.

Washington was personally acquainted with men in Virginia who chose to be loyalists in the American Revolution. He saw the threat of disloyalty early in the formation of the United States, and looked beyond the issue of slavery that ultimately led to the Civil War. He wrote in 1784 about the potential of the Spanish, who controlled trade that floated to New Orleans, to generate some form of alliance with people living in the Mississippi River watershed:4

At the start of the American Revolution, rebellious leaders such as John Adams knew that insurrection is dangerous. Those who lead a failed rebellion are typically executed as traitors, as demonstrated in Great Britain after the Jacobite Rebellion in 1745. In the 1776 Declaration of Independence, the revolutionaries pledged:5

Not everyone felt that revolution was an appropriate solution to the political disputes between officials in the colonies and in London. The wealthiest colonists saw their opportunity to acquire even more land and to increase commercial profits being constrained by British policy. However, most colonists were not directly threatened economically.

The outbreak of fighting in 1775 was followed by a civil war in 13 colonies. King George III made a fatal mistake when he assumed that the revolutionaries were a small percentage of the colonial population. The monarch assumed incorrectly that the insurrection reflected just temporary intimidation by rebels over the majority who continued to support royal and Parliamentary power over the colonies.

On October 27, 1775, the king rejected the Olive Branch petition submitted to him by the Second Continental Congress. He chose to pursue a hard line strategy to force the rebels to submit, expecting other colonists to regain control of the colonies after British troops arrived and comply with directions from royal governors and other appointed officials:6

Source: American Revolution Institute, American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World

As in all such wars, "average" people who just wanted to be left alone were forced to choose sides or flee.

Scottish storekeepers throughout the colony, but especially in Norfolk, recognized that they depended upon support from the Crown in order to stay in business. Rather than ally with rebels, the storekeepers chose to close down their businesses and migrate home.

In Virginia counties, local committees enforced the agreement with other colonies to stop importing and selling products from Great Britain. That approach was adopted after the British response to the Coercive Acts, Parliament's response to the Boston Tea Party. Banning trade in imported goods was an effective technique to ensure colonists would comply with the boycott, and not succumb to temptation to drink tea or purchase British-made clothing.

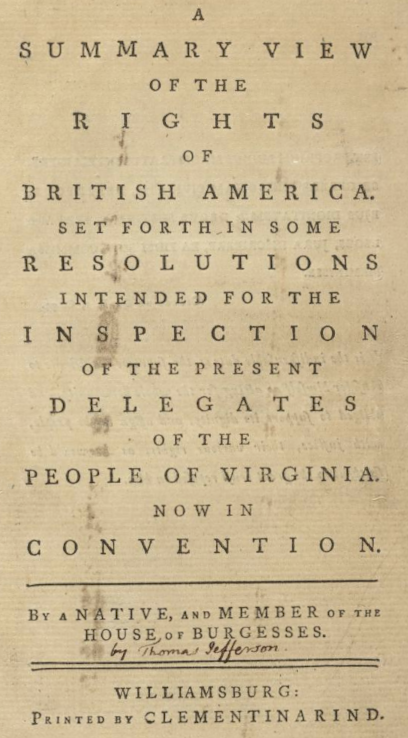

Violators of the non-importation agreement were socially ostracized and physically attacked. In Nansemond County, a Scottish merchant thought he could secretly continue to sell imported goods. He calculated that there were Virginia customers willing to break the boycott, if someone was willing to arrange for various products to be brought across the Atlantic Ocean. However, the Nansemond County Committee discovered the plans of Anthony Warwick. He was dragged 10 miles, tied to a public whipping post, and tarred and feathered in August, 1775. He later fled to the safety of Lord Dunmore's fleet in the Elizabeth River.7

a Scottish merchant violating the non-importation agreement was tarred and feathered in Nansemond County in August, 1775

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia Gazette (Number 485, August 24, 1775)

West of the Blue Ridge, settlers were frustrated by the political power of Tidewater planters. The individuals who settled on land grants were not the wealthy elite, and did not have large plantations with enslaved workers. When the American Revolution started, colonists living in the borderlands of Southwest Virginia understood that a war with Great Britain could result in more attacks by Native Americans on exposed frontier homesteads.

Source: MECCedu, SWVA In The American Revolution

Lord Fairfax in Northern Virginia did not express support for the American Revolution and never swore an oath of allegiance to Virginia. Though a loyalist, he also chose to stay on the sidelines and live quietly in what is now Clarke County. He was protected from physical harm by his close connection with George Washington, but the Virginia Act of 1779 confiscated all of the Fairfax Grant land which had not been sold.

Lawsuits over whether confiscation was legal continued until 1816. Virginia courts ruled that the land confiscation was legal. According to state law, Lord Fairfax's heirs could not inherit his unsold land after he died in 1781. Instead, that land was sized by Virginia.

The US Supreme Court ruled in the 1813 Fairfax’s Devisee v. Hunter’s Lessee decision that the 1783 Treaty of Paris (1783) and the 1785 Jay’s Treaty, ratified by the US Senate, were the supreme law of the land. According to the US Supreme Court, Federal treaties protected the rights of Fairfax's heirs and trumped state law. The case helped define the power of the central government established under the US Constitution.

In 1815, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled in Hunter v. Martin that the US Supreme Court had no authority to interfere with a state court decision. The reasoning assumed state courts were sovereign in interpreting state law, and Federal courts were sovereign in interpreting Federal law - but with equal authority, neither court could overrule decisions made by the other.

The US Supreme Court rejected that perspective, establishing a fundamental principle in constitutional law. The US Supreme Court decided in the 1816 Martin v. Hunter's Lessee case that Federal courts had the power to overrule decisions by state courts, but did grant title of the land to Virginia.8

A few key leaders in the Virginia gentry, with a strong support for traditional behavior and with economic advantages granted by the existing system of government, remained loyal to King George III. Some moved to London. Others managed to stay in Virginia without committing to support revolution, and some even joined the British military forces.

A significant part of the white farmers who did not belong to the gentry were unwilling to enlist in the Continental Army and evaded militia service, as they recognized another "rich man's war but a poor man's fight." Quakers chose to suffer economic punishment from Virginia county governments in order to avoid providing militia enlistees or supplies for war. Enslaved people scaped to British warships or armies when the opportunity presented itself, choosing actual liberty rather than support a change in regime leadership that claimed to fight for liberty - but only for whites.

In late 1775, Lord Dunmore raised the Queen's Own Loyal Virginia Regiment. Loyalist Virginia whites fought in it for a year, until Dunmore sailed out of the Chesapeake Bay in 1776 and the regiment was incorporated into the Queen's American Rangers. Loyalists in Norfolk and Portsmouth who chose to ally with Governor Dunmore ended up with their houses and businesses burned. The British started the destruction by burning structures along the Norfolk waterfront on January 1, 1776. The Virginia militia then burned the rest of the town, along with Alexander Sprowle's buildings and ships under construction at the Gosport Yard on January 4.

Over a century ago, historian Carl Becker highlighted that the American Revolution involved more than a war to end the role of Parliament and the King of England in control of the colonies. The American Revolution was a fight for home rule, but also a fight to determine who would rule at home once the colonies gained their independence. Eliminating the authority of the British government created a vacuum that might be filled by mobs, such as the supposed "Indians" in Boston who destroyed private property by dumping tea in the harbor.

Henry Lee III, known as "Lighthorse Harry Lee," witnessed brutal atrocities by between loyalists and rebels in the Carolinas in 1781. The experience shaped his political philosophy and made him as Federalist in support of a strong national government which could control mob violence and enforce the rule of law.

In 1781 while in the Carolinas, "Lighthorse Harry" Lee struggled to prevent his militia from executing loyalists who had surrendered. Despite his efforts, he wrote a fellow general that:9

an English cartoon showed rebellious colonists (as Native Americans) murdering six loyalists

Source: Library of Congress, The savages let loose, or The cruel fate of the Loyalists (by William Humphrey, 1783)

Enslaved people in Virginia viewed the revolution though their own unique lens. The white gentry claimed that a war was necessary to ensure no taxation without representation, but the rebel leaders had no intention to grant political or social freedoms to their "property." The best path for the enslaved to get freedom and the opportunity for a better standard of living was for the British to win the war; "freedom wore a red coat."

At the beginning of military conflict, Lord Dunmore sought to recruit the men among the 400,000 enslaved Virginians to join his new Ethiopian Regiment. The colonial governor created racially-separate military forces because he assumed few white Loyalists would be willing to serve alongside men who had just escaped from slavery.

When Lord Cornwallis marched through Virginia in 1781 before ending up at Yorktown, enslaved men and women provided intelligence about available supplies and served as guides through the unmapped areas. Cornwallis's troops took advantage of the information provided to decide where to camp, and how to move swiftly along country roads.

The British troops encouraged the enslaved people on plantations to run away and follow the army. The soldiers put some of the former enslaved people to work, using them as personal servants as well as laborers. Black Virginians provided support to the army that was most likely to provide them freedom.

The thousands who fled Virginia plantations joined with British and German troops who seized supplies while on the march. The pillaging at small farms and large plantations caused economic damage to the rebel leaders, and weakened the ability of the Marquis de Lafayette and General "Mad Anthony" Wayne to obtain food, horses, and other supplies for the American forces. The British fortifications at Yorktown were dug largely by Virginians who had fled their white masters.10

formerly enslaved Virginians who desired a British victory dug many of Lord Cornwallis' fortifications at Yorktown

Source: National Park Service, British Artillery Position (painting by Sidney E. King)

Attitudes were divided when fighting began, and even at the end. The military and political victory was complete after the Treaty of Paris. There was no significant effort by Americans after 1783 to rejoin the British Empire, though there were proposals in areas west of the Appalachians to unite with Spain.

Loyalists who strongly supported remaining a part of the British empire after 1783 had to move to colonies of Canada, Bermuda and Caribbean islands or cross the Atlantic Ocean to Great Britain. Some loyalists chose to stay in Virginia, and others eventually returned.

After the American Revolution, some Loyalists who had fled Virginia sought to return. In a debate at the General Assembly Patrick Henry strongly encouraged increasing the state's population through immigration and allowing the Loyalists to move back to Virginia. New residents would spur economic growth by bringing money to invest, and by purchasing goods and services in the state. As portrayed in an 1881 biography by William Wirt, Henry pontificated:11

However, Patrick Henry opposed proposals to return assets confiscated from the Loyalists.

Source: National Archives, Our First Civil War: Patriots and Loyalists in the American Revolution

Source: Esoteric History, America's Loyalists: Where Did They Go After The War?

Loyalists who fled Virginia had their property confiscated

Source: Howard Pyle blog, Tory Refugees on their way to Canada (by Howard Pyle, 1901)