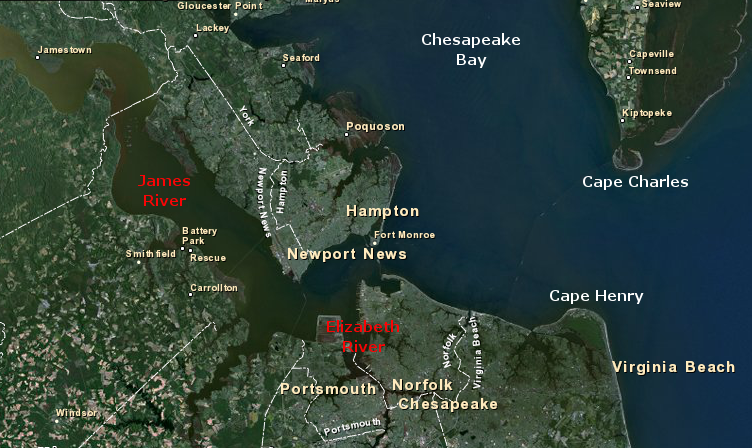

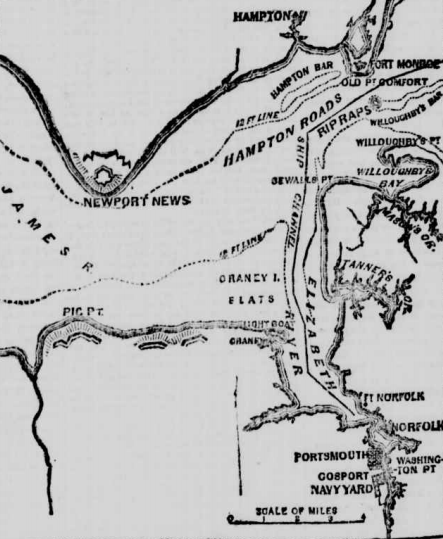

Union forces entered the Chesapeake Bay with impunity during the Civil War, once the CSS Virginia was destroyed

Source: Library of Congress, Panorama of the seat of war. Birds eye view of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia

Union forces entered the Chesapeake Bay with impunity during the Civil War, once the CSS Virginia was destroyed

Source: Library of Congress, Panorama of the seat of war. Birds eye view of Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia

The Chesapeake Bay has been a highway, more than a barrier, since Native Americans paddled to the Eastern Shore in canoes. Europeans used sailing ships as the 18-wheel trucks of the colonial era, penetrating up rivers to the Fall Line throughout Tidewater. Both pirates and warships have followed the same routes. Before invading Virginia in 1781, Lord Cornwallis wrote his superior in New York City that North Carolina was hard to conquer because it lacked "interior navigation," but:1

The threat of attack via the bay has shaped the location of colonial settlement, and even the location of modern industrial facilities. For 350 years after Jamestown, American ships and cargoes transiting through the Chesapeake Bay have been a target for attack.

In colonial times, the ships and their cargoes were far more valuable than the public buildings at the colony's capital. The Radford Arsenal and the first industrial plant in Blacksburg were placed far inland in Montgomery County at the start of World War II in order to avoid an enemy attack along the Atlantic Ocean coastline.

Destruction by an enemy of public buildings in Washington DC has great symbolic importance, as demonstrated in the War of 1812 and the September 11, 2011 terrorist attacks, but modern shipping and port facilities are still more valuable than buildings on shore. The Atlantic Fleet based at Norfolk, armed with nuclear weapons, is the most valuable military asset to protect on the East Coast.

In 1652 during the English Civil War, Governor Berkeley maintained his authority as royalist governor only until a fleet sent across the Atlantic Ocean by Parliament appeared in the Chesapeake Bay. When the ships arrived, the governor surrendered. A decade later, the Dutch demonstrated twice that enemy ships could wreak havoc after entering the bay.

The potential Spanish threat to the Virginia coastline determined the location of Jamestown in 1607, and it was not just theoretical. Combined Spanish and French fleets attacked Charles Town, South Carolina twice between 1702-1710.

During the American Revolution, the British were able to use their ships to travel swiftly to undefended locations and conduct raids onshore before the Virginia militia could assemble a defense. The Virginia Navy was no match for the heavily-gunned British warships, though at times it did manage to capture isolated ships.

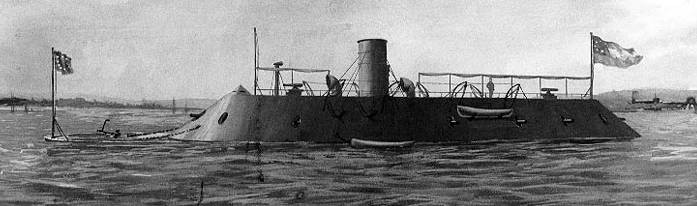

During the Civil War, Union forces were the "enemy" that threatened Virginia. The Confederate Navy was no match, though the CSS Virginia did deter the Union Navy from sailed upstream briefly in 1862. Cannon in a battery at Drewry's Bluff kept the Union Navy away from sailing up the James River to Richmond until April, 1865, but Unuin ships controlled the Chesapreake Bay throughout that conflict. during the Civil War. During the 1862 Peninsula Campaign and the siege of Petersburg in 1864-65, the Union Army relied upon water-based transport for supplies.

As recently as 2013, a contractor reported to the Pentagon that the two nuclear reactors at Surry were vulnerable to a terrorist attack from the sea.2

Throughout the colonial era, ships sailed from Caribbean islands or Europe to trade directly with Tidewater plantations. The bay provided equally good access for pirates and foreign navies to attack the plantations near the shoreline. Shore batteries were finally able to block the entrance to the Elizabeth and James rivers when Fort Calhoun was constructed on the Rip Raps shoal between Hampton and Norfolk by 1850.

The gap between Cape Charles and Cape Henry was too wide for land-based cannon until World War II. Until the creation of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM's) in the 1950's, the greatest foreign military threat to Virginia was a fleet arriving in the Chesapeake Bay.

forts were built to block foreign ships from sailing up the James and Elizabeth rivers, and when cannon were finally powerful enough forts were built at Cape Charles and Cape Henry to control passage into the Chesapeake Bay

Map Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Wetlands Mapper

Algonquian-speaking Native Americans had crossed the bay in boats ever since sea levels rose and the bay grew wider over the last 10,000 years. Native American canoes were far less maneuverable than European sailing ships and moving a canoe by muscle power was more exhausting than using wind power, but Powhatan's subordinates crossed the bay to establish control over Eastern Shore tribes decades before English colonists settled in Jamestown in 1607. If the Native Americans had documented their military history in writing, the annals of Powhatan might have included glorious stories of water-based maneuvering and amphibious attacks.

Powhatan's priests had warned him that a threat to his paramount chiefdom would come from the east, and long before 1607 he was aware of European ships that occasionally sailed into the Chesapeake Bay. His expansion of the paramount chiefdom he inherited may have been stimulated by the arrival in 1770 of Spanish colonists in sailing ships.

Powhatan and his predecessors had no military capacity to block the arrival of ocean-going European ships, though warriors in canoes could threaten a small ship in narrow river channels. When John Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay in a shallop during 1608, he took defensive precautions whenever canoes paddled out from shore to initiate discussions/trade, such as when he "incountred 7 or 8 Canowes full of Massawomeks."3

Powhatan lacked the technology required to sink ships of the invading "tassantassas" (strangers); he had no gunpowder or cannon. The Native Americans normally avoided a direct fight in open fields; they relied instead on asymmetric warfare and diplomacy to constrain the expansion of colonial settlement.

Opechancanough, Powhatan's successor, did attempt to use large-scale surprise attacks to expel the invaders. That technique failed in 1622 and 1644 to push the colonists out of Virginia, and even more arrived on new ships after each uprising. The invaders who arrived via the Chesapeake Bay in 1607 ended up occupying all of Virginia and displacing Native Americans of many tribes.

The waterways that facilitated colonial occupation of Virginia also served as an avenue for attack by other nations who might displace the English.

Since the Norman conquest of England in 1044 CE (Common Era), rulers in London have always recognized that enemy fleets could project power across waterway. England was an island, so the Royal Navy was developed as the main line of defense. Naval power was key to preventing invasion via the English Channel by the Spanish in 1588, by the Dutch in 1677, the French in 1779, and the Germans in 1941.

The Atlantic Ocean was much wider than the English Channel, but the entire ocean was never considered to be an adequate barrier to protect English colonies growing in the New World after 1607.

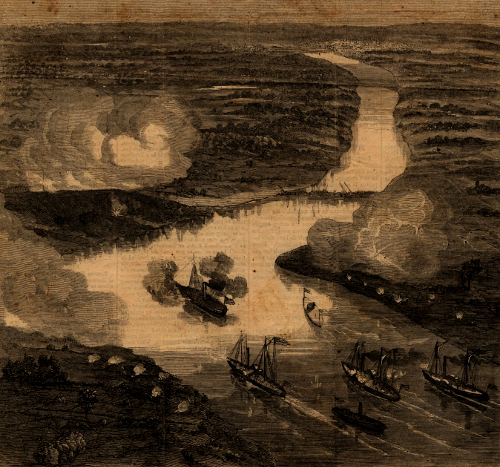

high cliffs at Drewry's Bluff allowed Confederates to block the Union navy from sailing upstream from Hampton Roads to Richmond in May, 1862 after the battle of the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia

Map Source: Library of Congress, [B]alloon view of the attack on Fort Darling in the James River, by Commander Rogers's [sic] [i.e., Rodger's] gun-boat flotilla, "Galena," "Monitor," etc.

The earliest English settlers to Virginia chose to sail past excellent harbors on the Lynnhaven and Elizabeth rivers, following specific instructions of the London Company. The Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery went upstream to Jamestown. That extra distance upstream lengthened the supply line, requiring an extra day or two of sailing to get to Jamestown, but it also reduced the potential of a surprise attack by the Spanish, French, or Dutch. The instructions prepared by the London Company in 1606 presumed that sailing inland would also force an attacker to sail up a narrow river channel, which could be lined with musket-firing colonists protecting their base:4

The colony at Jamestown was protected, but the more-valuable ships and cargoes at Hampton Roads were still exposed to fleets from other nations. Ships in Hampton Roads and the rest of the the Chesapeake Bay were also open to attack by individual ships that were authorized as privateers and by pirates, who on occasion organized small fleets that provided greater firepower.

building the Jamestown fort in May, 1607

Source: National Park Service - Sidney King collection of paintings created for the 350th Anniversary of Jamestown

Into the 1800's, a sail spotted in the Chesapeake Bay could mark the arrival of a commercial business opportunity - or a pirate masquerading as a merchant from England or the West Indies, coming to seize ships and even raid Virginia plantations along Tidewater shorelines. The English could sail from Europe to Virginia, and so could the enemies of England and water-based thieves.

In 1611, Sir Thomas Dale build Henricus upstream past the Appomattox River. The Virginia Company had directed him to create a new colonial capital that was less exposed to warships from rival European nations.

Observation posts located at Hampton and Cape Charles/Cape Henry have provided advance warning of ships entering the bay since 1609. Pirates or countries with a navy found the time required to cross the bay would provide the Virginians with time to assemble the militia.

The Jamestown settlers built Fort Algernourn/Algernourne in 1609, near the Native American town of Kecoughtan. The fort was located on the end of the Peninsula where Fort Monroe is now located. Fort Algernourne provided an early warning system of Spanish, Dutch, and pirate ships. Moving some starving settlers away from Jamestown in 1609 reduced the demand for food there, and may have reduced transmission of density-dependent disease.

The Algernourne Oak on the parade ground at Fort Monroe germinated around 1540. That live oak tree would have provided shade for the colonists who built Fort Algernourne in 1609, followed by Fort Henry and Fort Charles in 1611.

Sir Thomas Dale arrived in Virginia in May 1611 with new instructions from the Virginia Company to enhance discipline within the colony. He quickly issued the strict Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall and ordered construction of two new forts at the mouth of the Hampton River, Fort Henry and Fort Charles.

A Spanish ship captained by Don Diego de Molina arrived at Point Comfort in June, 1611. The English captured three of the Spanish sailors, including the captain, and prepared for a Spanish fleet to attack. That never happened; Phillip III of Spain never issued orders to eliminate the Jamestown colony.

Fort Algernourne was rebuilt after the Second Anglow-Powhata War in 1630-1632, and given the name Point Comfort.5

The first successful foreign attack on Virginia occurred in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. England sought to seize control of trade from the Netherlands, especially the slave trade from Africa to the Western Hemisphere. The First Anglo-Dutch War had been in 1652-54, after Oliver Cromwell had executed King Charles I and taken control in England. Even before an official declaration of the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War in 1665, an English fleet captured New Amsterdam in 1664 and renamed it New York.

Governor William Berkeley recognized the Dutch threat and wanted to create new forts to block enemy ships from sailing up the James, York, and Rappahannock rivers. He also proposed a fourth fort at Pungoteague on the Eastern Shore and abandoning the decayed fort on Old Point Comfort (today the site of Fort Monroe) that had not been upgraded since 1632. Providing effective cannon, and maintaining the fort's walls, had been considered as too expensive until the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. London officials over-ruled Governor Berkeley and commanded the fort be repaired. In the end, little work was done at any of the four locations.

Governor Berkeley correctly recognized that the greatest threat from the Dutch was not an invasion on land. Dutch privateers and warships were more likely to capture English ships in the Chesapeake Bay and off the Virginia coast. King Charles II struggled to fund Royal Navy operations and could afford to send only an old warship to the Chesapeake Bay for protection.

One outdated guardship provided inadequate defense. When a Dutch fleet arrived on June 5, 1667, the out-gunned HMS Elizabeth guardship surrendered after firing just one gun. The Dutch seized 19 ships loaded with tobacco that were assembling at Hampton Roads before sailing together to England. Three other tobacco ships managed to sail up the James River and escape. An additional nine merchant ships on the York River also stayed in English control.

In theory, the English tobacco fleet could have sailed near the fort at Point Comfort and received protection from the fort's guns. However, the English cannon on land were not powerful enough to hit enemy ships sailing in the channel. Militia on the Virginia shore were effective in blocking attempts to land and get fresh water for the Dutch fleet, but the Old Point Comfort fort ended up being nothing but a drain on the valuable resources of the Virginia colonists. A hurricane on August 27, 1667 finally destroyed the fort.

The Dutch captured so many ships in 1667 that they ran short of sailors to take them back across the Atlantic Ocean as prizes, so six of the 19 were burned. The Dutch all sailed away on June 11, 1667, leaving before Governor Berkeley could implement plans to arm the remaining English ships and attack the invaders.

Governor Berkeley then proposed to build forts at the mouths of the Nansemond, York, and Rappahannock rivers, plus one at Jamestown.

Despite the failure in 1667, and a repeat when the Dutch arrived again in 1673, Fort George was built on the tip of the Peninsula in 1727. Brick walls were built 16' apart and connected by more brick walls between them, and apparently the cells were then filled with sand to create sturdy fortifications.

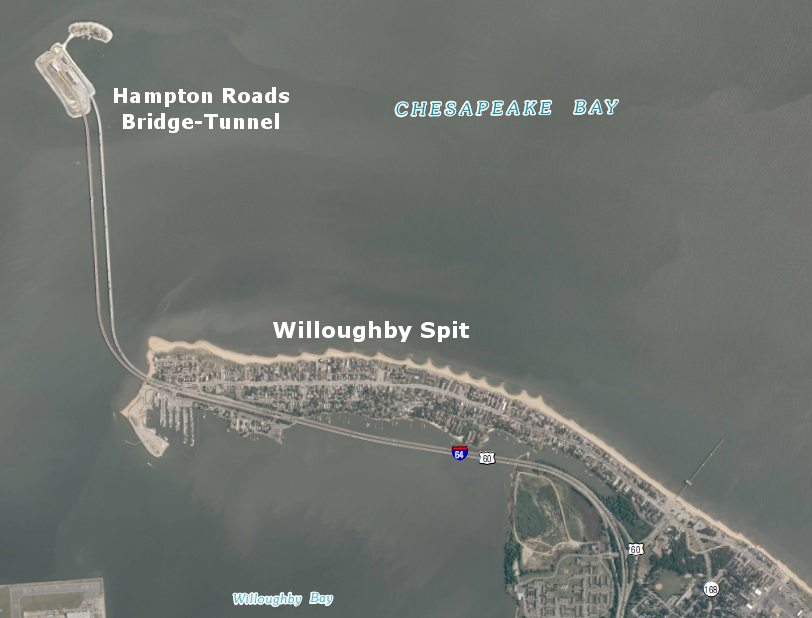

Fort George lasted a little over 20 years before it was destroyed by the 1749 hurricane that created Willoughby Spit. Hampton Roads offers several sheltered locations for a harbor, but a storm surge of 10-15 feet can rearrange channels/spits as well as sink ships and destroy buildings. The flaw in the design of Fort George was in its weak foundation:6

Old Point Comfort, at tip of the Peninsula, has been fortified since 1609... with a few gaps

Source: US Geological Survey, Hampton 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2011)

Willoughby Spit, formed in part by the 1749 hurricane

Source: US Geological Survey, Norfolk North 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (2011)

Fort George was not rebuilt after the hurricane. After the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended the War of Austrian Succession (also known as King George's War) between France and England, tensions had eased in Europe. Even during the Seven Years War (also known as the French and Indian War), Virginia did not rebuild a marginally-useful fort at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Instead, the colony focused on defending its western borders against French invasion and Native American raids.

In the Revolutionary War, when the American rebels had few warships in the Chesapeake Bay, the British were able to raid up the Elizabeth, Nansemond, Appomattox, James, and Potomac rivers with ease.

At the start of the war, Lord Dunmore abandoned Williamsburg and found safety on the HMS Fowey, a British warship in the York River. After raiding plantation homes for supplies and to damage property of prominent rebellious colonists, his flotilla sailed south to the Elizabeth River. He established his land base at Gosport, when loyalist Alexander Sprowle operated a shipyard.

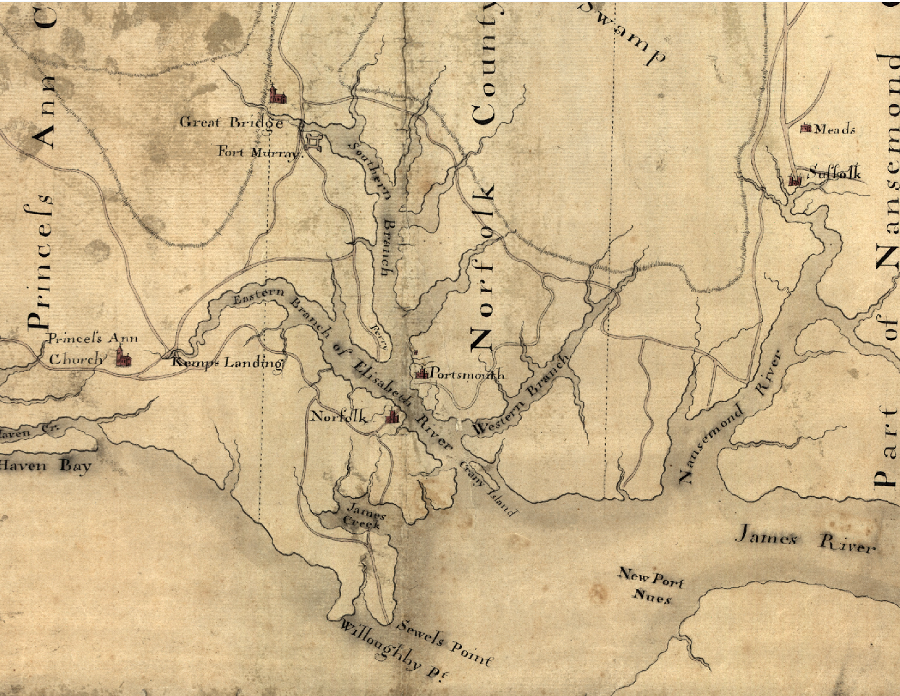

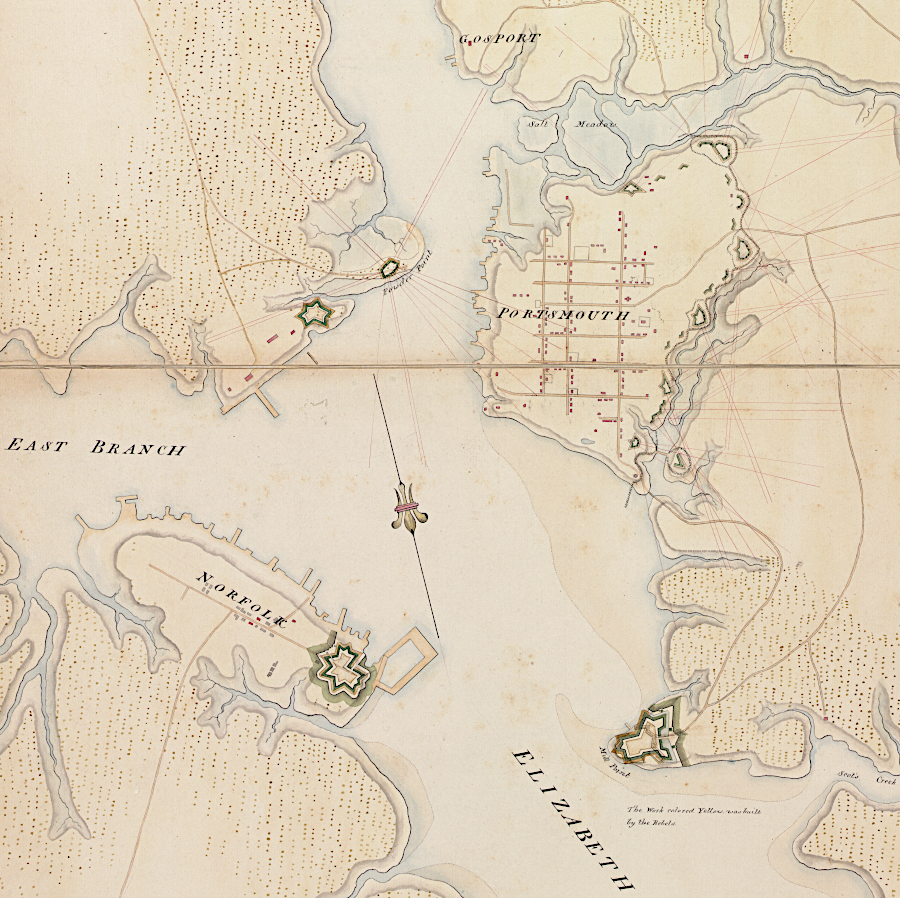

Loyalists controlled Norfolk when the Virginia militia marched towards it in October, 1775. Dunmore's ships were unable to move up the James River fast enough to block the Virginia militia from crossing from Jamestown to the southern side. Col. Woodford led five companies of the Second Regiment through Nansemond County to threaten Norfolk from the south. Patriots also assembled a force at Kemps Landing at the tip of the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River.

The British fortified the causeway at Great Bridge, building Fort Murray to block troops under Col. Woodford from advancing to Norfolk. To recruit new soldiers and to threaten the colonists, Dunmore issued a proclamation offering freedom to slaves who joined his forces and fought for the King. Though the British controlled the Chesapeake Bay with powerful warships, Dunmore recognized that the threat of slave uprisings and emancipation of laborers from Chesapeake Bay plantations was also an effective military measure.

After the British rashly attacked across the causeway and were defeated at Great Bridge, they retreated to Norfolk. The Americans gradually forced the loyalists and troops to abandon the city and stay on the warships in the harbor. American riflemen on the Norfolk shoreline then made it difficult for anyone to expose themselves on the ships.

In response, on the first day of 1776 Dunmore shelled Norfolk and landed troops. They did not re-occupy Norfolk; instead, the British troops burned the structures on the shoreline that might used by Virginia sharpshooters. Rather than fight to save the town, the Virginia militia then set more fires and burned down the rest of Norfolk. Destroying the town ensured it could not become a support base for a British fleet, and also punished the loyalists who were such a high percentage of the town population.

On the east side of the Elizabeth River, Dunmore moved his forces stationed at Gosport. They crossed Crab Creek and consolidated within the fortifications at Portsmouth. The Virginia militia then burned the shipyard on January 4, 1776.

Two Royal Navy warships arrived in the Chesapeake Bay in February, 1776 to reinforce Governor Dunmore. John Page alerted the Virginia Committee of Safety regarding the new military capacity of the British, and highlighted the inability of the Virginia militia to interfere with their ability to come onshore anywhere they might choose:7

Dunmore finally abandoned efforts to establish a permanent base on the Elizabeth River. He sailed away from Portsmouth to establish another base on Gwynn's Island. Disease substantially reduced his forces there, especially among the escaped slaves. When the Americans placed cannon on the mainland that could reach his ships and attacked on July 9, Dunmore fled to St. George's Island near the mouth of the Potomac River. Maryland militia forced him away from there, and the British ships sailed out of the Chesapeake Bay in August, 1776.

The Virginia militia succeeded in pushing the British away from the Chesapeake Bay, using just land forces without use of naval forces - but the British had the military capacity to sail back to Hampton Roads or anywhere else in the Chesapeake Bay, at any time.

General Charles Lee arrived in Virginia in early 1776 to organize the defenses there, and to facilitate delivery of supplies and recruits to the Continental Army stationed in New England. After he learned that a fleet with 2,000 men led by Sir Henry Clinton had just sailed to Cape Fear to help Governor Josiah Martin reestablish royal control in North Carolina, he wrote to George Washington on May 10, 1776. Lee's letter decribed the difficulty of fortifying the Chesapeake Bay shoreline and stationing troops to defend against British attacks at different locations:8

the British controlled the water with their warships, but Fort Murray

failed to block the Virginia militia from crossing Great Bridge over the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River

(NOTE: on this map, south is at the top and north is at the bottom)

Source: Library of Congress, Part of the Province of Virginia (1791)

In August, 1777 General William Howe sailed his British army from New York up the Chesapeake Bay, then marched north to capture Philadelphia after defeating George Washington at the Battle of Brandywine. Howe had intended to land on the shore of the Delaware Bay, but was told that obstructions in the Delaware River would block his plans. There were no constraints to travel in the Chesapeake Bay. No forts with cannon blocked him from sailing between Cape Charles and Cape Henry, or up to a point near Head of Elk at the northern tip of the bay.

In May, 1779, Sir George Collier led 28 ships with 1,800 men under General Edward Mathew and surprised the Virginians in Hampton Roads. Fort Nelson, guarding the Gosport shipyard in Portsmouth, was quickly captured. The fort was very well constructed, and with the British attacking by land there was no problem with the range of the Virginia weapons. However, the British forces outnumbered the Virginians 20-1 and the Virginia commander with only 100 men chose to retreat rather than fight.

The British burned the Gosport Ship Yard, where the Continental Navy was trying to complete the frigate Virginia. Collier wanted to stay at Portsmouth, which he described as "an exceeding and safe asylum for ships against an enemy." Collier viewed Portsmouth as the best location for a base to support the British blockade, ultimately starving the American rebels of gunpowder, weapons, uniforms, and other military supplies being imported from Europe. However, Mathew decided that his orders for the mission were just to search and destroy, rather than to stay.9

By 1779, British strategy was shaped by the threat of the French fleet as well as of the American militia and Continental Army. Creating a permanent base in the Chesapeake would over-extend the American Squadron, so Collier was summoned back to New York. Before leaving, he burned Virginia and a massive stockpile of high-quality shipbuilding timber.

The Collier-Mathew hit-and-run attack made Virginia's legislators realize that the Revolutionary War would be fought in their state, as well as in the north between Philadelphia and Boston. The raid destroyed extensive supplies in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Suffolk, as well as warships under construction.

Merchant ships loaded with tobacco for France ended up as prize ships, and the profits went to British officers rather than helping the American side. Including the ships seized in the upper Chesapeake Bay, 137 vessels were captured by the British at the cost of just two men being wounded. By the time the Virginia militia had been assembled, the British had returned to their ships. Various British warships continued to patrol the Chesapeake Bay in 1779, with no resistance by the Americans.10

Another British invasion in 1780 showed Virginia was better prepared to defend itself. General Alexander Leslie brought only a half-dozen or so ships, but 2,200 men. He landed at Portsmouth on October 21 and attacked Newport News/Hampton on October 23, 1780. The intent was to intercept Virginia supplies and divert American troops away from the British campaign under Lord Cornwallis, as they marched north after capturing Charleston, South Carolina in May.

However, the Virginians mobilized while minimizing the impact on their support for the Southern armies. Most of the Virginia Line had been captured in the disastrous defeat at Charleston, but the rebellious American forces in South Carolina were still resisting Cornwallis' northern advance. As directed by George Washington, Virginia continued to send reinforcements and supplies south, rather than to the Continental army that kept the British trapped in New York City.

British forces captured the battlefield at Camden, Kings Mountain, Cowpens, and Guilford Courthouse, but those Pyrrhic skirmishes cost the British irreplaceable soldiers. To maintain the army fighting in North America, the British had to hire Hessian soldiers from Germany as mercenaries. Recruiting and shipping replacement troops across the Atlantic was as challenging as getting American soldiers to Vietnam 35 years ago.

General Leslie was deterred from sailing up the James River by reports of large groups of Virginia militia and strong fortifications on the riverbanks. The Virginians freed up the guards responsible for 2,800 prisoners in Charlottesville by marching those prisoners north to Frederick, Maryland. The Albemarle Barracks (west of the modern Barracks Road Shopping Center on Route 29) had been built by the prisoners, primarily Hessians who had been captured at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 and marched from Boston to Virginia in 1779 for safekeeping.11

The next assault via the Chesapeake Bay came soon after Leslie was redirected south to reinforce Cornwallis at Charleston. General Benedict Arnold sailed from New York to the James River and arrived on December 30, 1780 with almost 30 ships and 1,500 troops.

Virginia's military defenses were, once again, revealed to be inadequate. There were no American cannon or troops at Point Comfort to delay movement up the James River; Fort George had not been rebuilt after its destruction in a 1649 hurricane.

When Arnold was spotted in the Chesapeake Bay off Willoughby Spit, the Virginians could not determine if his target was Williamsburg, Petersburg, or Richmond until the fleet sailed upriver past Jamestown. Arnold put troops ashore on the south bank, and they forced the militia to evacuate the incomplete Virginian fort at Hoods Point. That fort, opposite Weyanoke Point at a sharp bend in the river, was the only opportunity to block the British fleet from going upriver all the way to Richmond.

after sailing past the incomplete Virginian fort at Hoods Point (1), Benedict Arnold landed at Westover Plantation (2) and marched on the north bank of the James River to Richmond

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The British chose to go onshore and move overland to seize the capital. About 900 soldiers and loyalists organized as the marched quickly from William Byrd's plantation wharf at Westover to Richmond. The Virginians did manage to move some supplies to the south side of the James River, but the British burned public records and destroyed the Westham foundry that produced cannon for the Americans.

Benedict Arnold's troops and loyalists also burned private warehouses loaded with tobacco. Since the American currency had depreciated to the point that it was "not worth a Continental" and money issued by the state had lost much of its value, importing military supplies from Europe usually involved trading with Virginia tobacco. Arnold's burning of tobacco in Richmond was equivalent to burning money in the state treasury.

Arnold's concern about the Virginia militia deterred the British from crossing the James River and capturing Manchester in January. Arnold returned to Portsmouth after his January, 1781 Richmond raid. He established a permanent British occupation post in Virginia, fulfilling the plan originally assigned to Leslie several months earlier.12

The Virginia militia were organized under General Thomas Nelson north of the James River, and under General Peter Muhlenberg south of the river. General Greene left Baron von Steuben in overall command, but there were not enough men or supplies for the militia to go on the offensive and attack Portsmouth.13

George Washington and his French allies tried to provide assistance to the Virginians. In February, the French sent ships from their fleet at Newport, Rhode Island to the Chesapeake Bay. They were able to sail into the Lynnhaven Bay, but those ships required deep water. Arnold simply moved up the Elizabeth River, where water depth was shallow. The French squadron did not carry the army troops required to attack Portsmouth on land, so the squadron returned to Newport and left Arnold unchallenged.

A second initiative of Washington and the French involved sending the Marquis de Lafayette and French troops to Virginia. American troops marched south from New York, while French troops were sent via ship from Rhode Island. Washington planned to relieve the pressure on Virginia so it could renew its shipment of supplies to the Continental Army challenging Cornwallis in South Carolina, and also hoped to capture and execute Benedict Arnold as a traitor.

The initiative required close cooperation between American/French troops on land and French ships. The Americans, with Lafayette, were able to march south and then sail down the Chesapeake Bay to Hampton Roads. However, the French fleet with 1,200 essential troops was unable to force its way past a British fleet blocking access to the Chesapeake Bay and had to return to Newport. (Six months later, Washington and Rochambeau would repeat the maneuver and, thanks to a more-successful French fleet, catch Cornwallis at Yorktown.)14

General Clinton sent 2,000 more troops from New York to Hampton Roads in March. They were led by General William Phillips, and Arnold remained in Hampton Roads as Phillip's subordinate. Lafayette ended up staying in Virginia with a small force of Continental Army troops, enough to harass but not to defeat the British.

The British based at Portsmouth could move throughout Tidewater with impunity. The majority of the Continental Army was far to the north, keeping the British trapped in New York City, and could not spare enough troops to protect Virginia.

On a raid up the Potomac River, a British squadron sailed past Mount Vernon before seizing merchant ships and tobacco from Alexandria. Lund Washington, cousin of George Washington and caretaker at Mount Vernon, provided supplies to the British in exchange for protecting the mansion - to George Washington's great embarrassment.

From their base at Portsmouth, Phillips and Arnold destroyed the Virginia State Navy shipyard on the Chickahominy River, which had been developed after Collier's destruction of the Gosport Ship Yard in 1779. They sailed to City Point and marched to Petersburg, easily defeating the Virginia militia under General Peter Muhlenberg that assembled at Blandford. (During that battle, American artillery based on bluffs north of the Appomattox River gave the name to Colonial Heights.)15

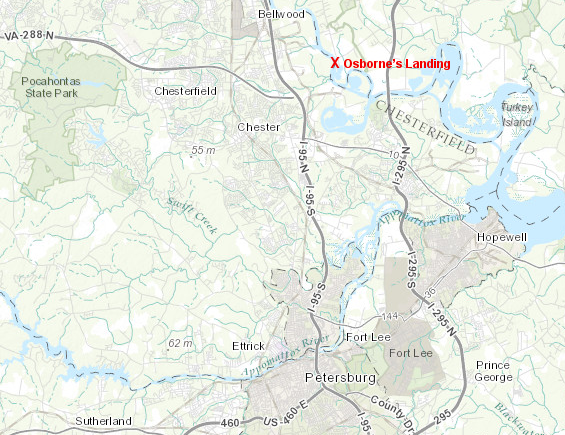

Phillips destroyed tobacco, flour, and other military supplies at Petersburg, then moved north to burn the military training camp (and former prisoner of war camp) at Chesterfield Courthouse. Arnold split off and marched his troops swiftly to Osbourne's Landing on the James River. He surprised the remnants of the Virginia Navy there.

The Virginia Navy had concentrated its ships there, with plans to attack Portsmouth if the French sent another fleet south from Rhode Island to capture Portsmouth. Instead, Arnold's land-based troops used cannons and rifle fire to capture or destroy the entire fleet. In 1985, marine archaeologists unsuccessfully sought to find the sunken wrecks. The James River may have migrated westward. If so, any remnants of the Virginia Navy ships destroyed by Arnold in April, 1781 may be underneath Farrar's Island today.16

on April 27, 1781, Benedict Arnold destroyed the Virginia Navy, which had gathered at Osbourne's in anticipation of a joint French-American attack on the British base at Portsmouth

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Phillips and Arnold then moved upstream to Manchester at the end of April, and destroyed tobacco and supplies there. A small force of Continental Army troops under Marquis de Lafayette watched from the Richmond side of the James River, in a mirror image of how Thomas Jefferson had observed British forces from the opposite side of the river in January 1781.

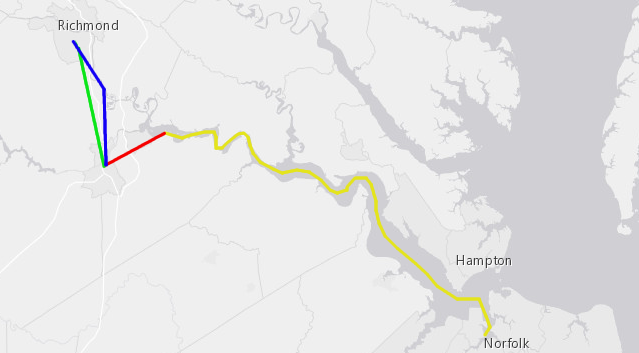

in April 1781, General William Phillips and Benjamin Arnold sailed from Portsmouth to City Point (yellow line), marched to Petersburg and destroyed supplies after the Battle of Blandford (red line), and then Phillips went to Manchester via Chesterfield Court House (green line) while Arnold detoured first to Osbourne's Landing to destroy the Virginia Navy

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The easy military successes of Phillips and Arnold in Virginia affected two key decisions, one political and one military.

The political decision was made by Virginia's leaders within the General Assembly and in Congress.

In 1781, Virginia was clearly unable to protect itself; it needed assistance from the other colonies. To encourage the other states in the Continental Congress to contribute more troops to protect Virginia, the state's political leadership decided to compromise on its boundary claims to western lands north of the Ohio. Virginia ceded what became the "Northwest Territory" to the national government.

Virginia also resolved an old boundary dispute with Pennsylvania. The General Assembly abandoned Virginia's claims to the Forks of the Ohio (Pittsburgh) area, which had triggered George Washington's 1753 trip and ultimately the French and Indian War.

Both Virginia and Pennsylvania agreed to extend the Mason-Dixon line to five degrees west of the Delaware River, then draw a line due north to define Pennsylvania's western boundary. Virginia was unwilling to extend the western boundary directly to the Ohio River, however. Pennsylvania ended up with some straight boundaries while Virginia (now West Virginia) created a "panhandle" between Pennsylvania's western border and the Ohio River.

The military decision was made by General Cornwallis.

He had left Charleston and fought American forces at various locations in South Carolina and North Carolina. The Americans maneuvered ahead of Cornwallis, reducing his military capability. After Guilford Courthouse, there was a "race" to the Dan River. General Greene and the Americans won that race, moving all the boats to the north bank near South Boston. That blocked Cornwallis from crossing, though in some cases the Americans were just barely across the Dan River when the British scouts first arrived on the other shore.

In April, 1781, the British general chose to abandon the pursuit of the American forces and march to the sea rather than proceed north into Virginia's Piedmont. Cornwallis moved first to Wilmington, North Carolina, for resupply. It was a safe place, but simply keeping his army idle at that port would do nothing to end the American rebellion.

Cornwallis chose to join Phillips, and marched overland to Petersburg in May, 1781. There he took command from Arnold of all British troops in Virginia, a week after Phillips had died from disease.

Cornwallis went on the offensive. He crossed the James River to the wharf at Westover, then marched north to Hanover Court House and up to the Rapidan River. Lafayette fled to the north bank, crossing at Ely's Ford. There were no military resources or tobacco worth capturing or destroying at Fredericksburg, so that town was spared a visit by the British.

Charlottesville was not so lucky. The General Assembly had abandoned Richmond and fled inland, and the British considered the rebel leaders to be an attractive target. Col. Banastre Tarleton (the villain in the movie The Patriot) led a fast raid to Charlottesville.

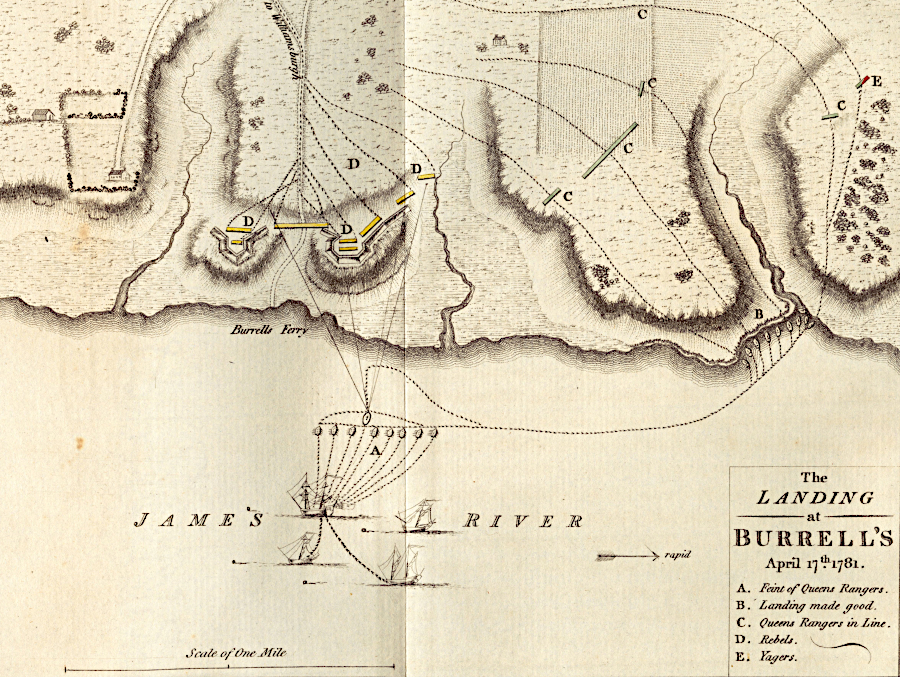

Col. John Simcoe landed at Burrell's Landing (modern Kingsmill Resort) in 1781

Source: Levanthal Map Center, Boston Public Library, The landing at Burrell's, April 17th. 1781

However, while Tarleton's Legion stopped briefly at a tavern in Louisa County, Jack Jouett started a dramatic night ride to warn the General Assembly. He had to avoid the main roads where the British were arresting everyone. Reportedly, Jouett's face was scarred for life from the branches that he hit in the dark, on the way to Charlottesville. He got there just in time. Governor Thomas Jefferson, at the end of his term in that office, fled across Carter's Mountain as the British reached Monticello. The General Assembly fled across the Blue Ridge to Staunton.

Colonel John Simcoe led a simultaneous British raid on the north bank of the James River to Point of Fork at the mouth of the Rivanna River. There he captured a large number of Virginia supplies. General Baron von Steuben managed to escape with most of the Continental Army supplies to the south bank of the river. He described his maneuvers as successful, since he had fulfilled his mission, but that claim ignored the overall impact of the military losses due to the American inability to defend any fixed location against the British forces in 1781.

By 1781, six years after open warfare started at Lexington and Concord, the British forces had captured all of the large American cities, marched through the various state capitals with ease (including Richmond), and were now disrupting the ability of the Americans to maintain an army in the field by destroying the supply bases throughout Virginia. Eighty years later, Union generals would do the same to the Confederates... and in the 1860's, France would not come to the rescue, as it did in 1781.

Chesapeake Bay - British attack routes in 1780-81

Cornwallis then concentrated his forces at Yorktown, with fortifications across the York River in Gloucester. He considered but rejected Old Point Comfort, and evacuated Portsmouth. Yorktown was a deepwater port, the existing town offered shelter, and his troops could forage and raid to provide supplies while Cornwallis awaited reinforcements promised by General Clinton in New York.

The amazing defeat of Cornwallis at Yorktown in October, 1781 can be explained best by the unwillingness of the British commanders to work as members of a team. The British army depended upon re-supply from the sea, but the navy did not synchronize its operations to support Cornwallis's army. In contrast, the French and the Americans coordinated their operations, to maximize their opportunities.

The French were partners, not subordinates who took orders from George Washington. The French rejected George Washington's proposals to attack on New York, because the British fleet and soldiers on the ground were too powerful. The Americans had minimal naval assets, and the British had defeated the French several times in previous naval engagements.

The French were not reluctant to fight, just careful to pick a fight they could win. They moved their fleet from the West Indies and created an extraordinarily large fleet, for a brief moment, to fight the British off the coast of Virginia.

In September, American and French troops stationed outside of New York marched south to the head of the Chesapeake Bay. French ships then provided transportation to move the troops by water to the Peninsula, while the artillery moved by land to Cornwallis's encampment at Yorktown. By consolidating their forces in Virginia rather that at New York, the French and Americans briefly outnumbered the British in troops and artillery.

That advantage would disappear if the British fleet brought reinforcements from New York to strengthen Cornwallis. However, on September 5, 1781, the French warships led by the Comte de Grasse fought the British led by Admiral Thomas Graves in the "Battle of the Capes."

The French fleet sailed out of Chesapeake Bay, surprising the British with the number of ships of the line that they had assembled. The Battle of the Capes was a draw, basically, with each navy punishing the other but not gaining domination over the other.

The key to the decision at Yorktown was that the French retained control of the Chesapeake Bay while the British fleet returned to New York for repairs. As a result, Cornwallis was trapped. Unable to get new supplies or troops, the British general was forced to surrender after a French-American siege.

The French gamble to risk taking their warships from the Caribbean to the Chesapeake came just in time. A year later, in the Battle of the Saintes, the French fleet was destroyed by the English.

the French admiral who trapped Lord Conwallis at Yorktown, the Comte de Grasse, is honored by a statue at Joint Expeditionary Base Fort Story

Source: City of Virginia Beach, Hints of History: "Admiral de Grasse Statue"

Cornwallis had played it safe and waited for help from his navy, while Washington and the French allies gambled and won at Yorktown. The English general waited too long. He assumed his commander in New York would deliver on his promises and prevent the British Army from being trapped. When Cornwallis finally tried a breakout, a storm prevented the British ships from evacuating Yorktown and on October 19, 1781, he surrendered.

Had Cornwallis showed more initiative, he could have broken through the French or American lines before they established siege trenches and trapped him in Yorktown. In particular, he could have crossed the York River and marched north past Gloucester as the Americans/French were marching south from New York.

the replica of the French tall ship Hermione, which brought Lafayette to America in 1780, met the guided-missile destroyer USS Mitscher on the way to Yorktown in 2015

Source: US Navy (150602-N-OA702-009)

Loyalists controlled many Chesapeake Bay islands during the American Revolution. Even after Yorktown, the loyalists were a threat to shipping and plantations along the shoreline. The Maryland State Navy tried to seize Tangier Island in May, 1782, but were defeated. In the battle, Maryland Commodore Thomas Gason was killed and one of the three sailing barges on the Maryland State Navy was lost.17

the British built forts on the Elizabeth River in 1780-81 to protect their base at Portsmouth (north is towards bottom of map)

Source: Library of Congress, A plan of Portsmouth Harbour in the province of Virginia: shewing the works erected by the British forces for its defence, 1781 (by James Stratton, 1782)

On March 20, 1794, the US Congress authorized fortifications to protect 19 harbors from a naval attack by a European fleet. Under the new Constitution, the national government had responsibility for funding the First System of fortifications established on the coastlines. French military engineers were hired to help design and build the forts.

To minimize cost, many First System structures were built primarily using dirt and wood. An exception was Fort McHenry, bult using bricks and masonry to defend Baltimore.

A Second System to enhance coastal defenses was authorized after the British warship HMS Leopard attacked the USS Chesapeake at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on June 22, 1807. The weakness of the US Navy and the threat of war with a European nation was exposed, justifying the cost of upgrading forts protecting American harbors.

A brick First System structure still remains at Fort Norfolk, which was built to block enemy ships from sailing up the Elizabeth River. The brick wall still surrounding Fort Norfolk was constructed in 1809 as part of the Second System of defense.18

Fort Norfolk was part of the First System of coastal defenses authorized in 1794, and the wall was added in 1809 after the Second System was authorized

Source: Library of Congress, Remnant of Fort Norfolk in downtown Norfolk, Virginia, the last remaining fortification of President George Washington's 18th-century harbor defenses; Virginia Landmarks Register, Fort Norfolk

During the War of 1812, the British were unable to capture the navy yard at Portsmouth as Sir George Collier had done in 1779. The Americans fortified Craney Island, and their cannon and accurate rifle fire stopped a British amphibious assault. In reaction, the British burned Hampton; there were no American fortifications at Point Comfort to protect the town.

tidal flats kept British warships away from Craney Island in 1813

Source: Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, New York Daily Tribune, May 12, 1862

The British blockaded the Chesapeake Bay, and the USS Constellation was trapped for the duration of the war at the navy yard on the Elizabeth River. British warships raided the Virginia coastline at will in 1813, seizing supplies and allowing slaves to escape. Some of those freed slaves then joined the Colonial Marines regiment and fought for the British.

Chesapeake Bay on New Year's Eve, 2003

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Earth Observatory

The British fleet established a base on Tangier Island and built Fort Albion. In August 1813, the majority of those warships sailed up the Patuxent River in Maryland, forced the destruction of the small flotilla of American barges intended for defense, and landed army troops so they could march westward across Maryland to Washington, DC. General Ross defeated the thin American forces at Bladensburg, then burned the public buildings in the US capital before returning to the ships in the Patuxent River.

At the same time, a squadron of British ships sailed up the Potomac River. The warships were delayed crossing the shallow Kettle Bottom, a series of shoals and oyster bars downstream of the modern Route 360 bridge across the Potomac River. The Potomac River flotilla arrived after British troops had burned Washington and withdrawn. Alexandria officials surrendered with great haste to the British, to avoid having the town bombarded and/or burned. The British seized 21 prize ships, emptied the local warehouses of tobacco, rum, and other goods, and sailed back down the Potomac River to rendezvous with the rest of the fleet.

The return trip was delayed by American cannon and troops who fortified a point downstream of Mount Vernon. The ruins of George William Fairfax's plantation home (Belvoir) were still visible there, but the site was better known for a white-painted house on the shoreline that was used to collect customs duties. The British ships were forced to wait five days for favorable winds before sailing past the American fortifications, and three ship captains were wounded.

The successful resistance at Craney Island and the "Battle of White House Landing" on the banks of the Potomac River were the only times that Virginia's military forces mounted an effective defense during the War of 1812.19

The inability to defend the nation's capital in the War of 1812 made clear that a new approach was required. Congress funded the Third System of coastal defense, with masonry forts that could resist a long siege.

Fort Monroe, built at Point Comfort between 1819-1834, is the prime example of that approach.20

However, it was obvious by the 1830's that the threat of a naval attack would not be followed by an army of occupation from a European power. Abraham Lincoln noted in his 1838 "Address Before the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois," that the greatest threat to American democracy was internal:21

Foreign invasion was never a factor in the Civil War. No fleets from Britain, France, or Spain sailed into the Chesapeake Bay.

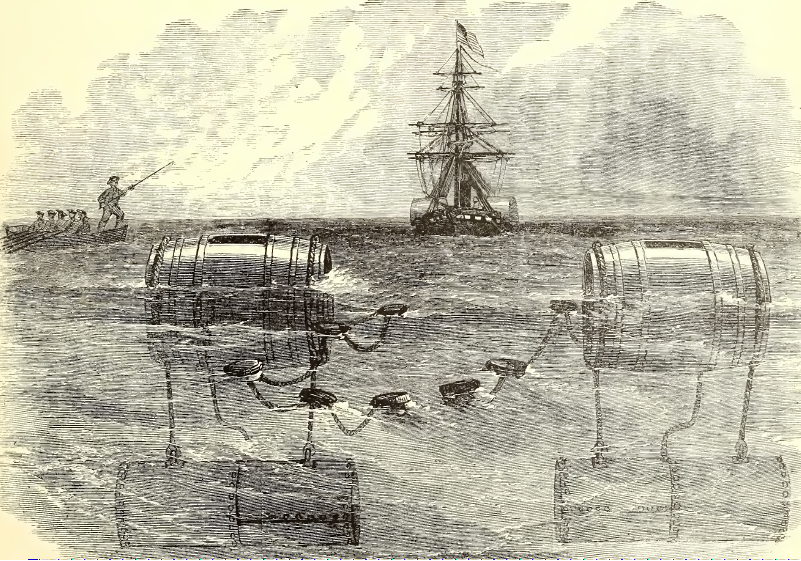

The Potomac River was the scene of the first minor conflicts between Union/Confederate forces during the Civil War. In June, 1861, Union ships shelled Confederates on the shore at Aquia Creek. Confederates retaliated by trying to float underwater mines that would destroy those ships.

After the First Battle of Manassas in July, 1861, Confederates build batteries on the Prince William County shoreline of the Potomac River. The cannon and troops stationed at those batteries created a partial blockade of the Union capital, limiting the ability of ships to bring supplies up the river to Washington DC through the winter of 1861-62. The batteries were abandoned when General McClellan sent forces to the Peninsula to advance on Richmond, and reinforcements were required to block his advance.

since the Confederates lacked a Navy on the Potomac River, they practiced asymmetric warfare and tried to use underwater mines to destroy Union ships

Source: Frank Leslie's Illustrated History of the Civil War, Infernal Machine Designed By the Confederates to Destroy the Federal Flotilla in the Potomac, Discovered by Captail Budd of the Steamer "Resolute" (p.163)

At Point Comfort, Fort Monroe had been completed in 1834 - almost 90 years after Fort George was destroyed in a hurricane. Rock was dumped on the Rip-Raps shoal and Fort Calhoun constructed at the same time, providing another platform for cannon to control the shipping lanes to Norfolk and Richmond.

During the Civil War, Fort Monroe served as a supply base and hospital for Union troops. (Fort Calhoun was renamed Fort Wool, and stayed in Union hands as well.)

the private company Adams Express routinely delivered packages to Fort Monroe during the Civil War

Source: Frank Leslie's Illustrated History of the Civil War, Scene In Adams Express Office, At Fortress Monroe, VA, in 1861 - Volunteers Receiving Letters And Packages From Home (p.180)

From the perspective of Virginians who supported the Confederacy, forts built at Point Comfort on land donated by the state, and intended to protect Virginia from invasion, became bases to facilitate invasion - especially during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

CSS Virginia, Confederate ironclad designed to keep Union navy out of Hampton Roads in 1862

Source: US Navy, CSS Virginia (1862-1862), ex-USS Merrimack

By capturing Portsmouth and Norfolk, the Yankees forced the Confederates to abandon their last efforts to use the CSS Virginia to control the sea lanes at Hampton Roads. Confederates were forced to abandon the Norfolk Navy Yard in Portsmouth and they destroyed the CSS Virginia ironclad. However, they fortified Drewry's Bluff upstream, and Fort Darling plus sunken ships in the James River blocked the Union navy from sailing up the James River. The US Navy was unable to support General McClellan's army during the Seven Days battle, so fortifications on the shoreline did help protect Richmond from being captured.

in 1862, Confederates were able to block the Union navy from reaching Richmond after the CSS Virginia was destroyed, by fortifying Drewry's Bluff far upstream from Hampton Roads

Map Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), The National Map

Drewry's Bluff

Source: US Geological Survey, Drewry's Bluff quadrangle

After the destruction of the CSS Virginia, the Confederate Navy offered minimal threat to the US Navy. Fort Monroe's guns were used only for practice until 2011, when the base was finally decommissioned as a part of the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process. From the perspective of Virginians who supported the Union, Fort Monroe had succeeded in its mission to protect the United States.

Rip Rap Shoal was converted into Fort Calhoun/Fort Wool, to control Hampton Roads

Source: Library of Congress, Copy of a map military reconnaissance Dep't Va. (1862)

The Civil War demonstrated that rifled cannon on warships could destroy masonry forts. Fort Monroe and Fort Wool were not upgraded with new technology until after the Spanish American War, when disappearing guns and new batteries were constructed under the Endicott Plan.

During World War II, German U-boats were able to penetrate into the main British naval base at Scapa Flow and sink a battleship, but the US Fleet was never attacked at Norfolk. Between 1942-45, German U-boats stayed in the Atlantic Ocean, sinking tankers and other ships within sight of Virginia Beach.

Once the Atlantic Fleet was based at Norfolk Naval Base, however, enemy access to the Chesapeake Bay has been limited. Creation of an intercontinental ballistic missile defense system in the 1950's completely replaced the concept of blocking warships between Cape Charles-Cape Henry, or at Point Comfort.

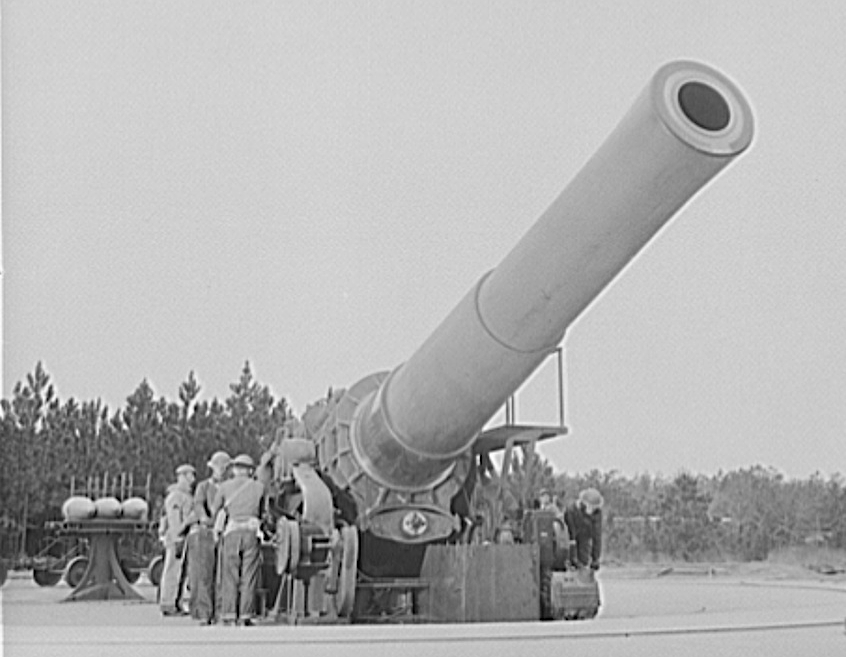

long-range guns defended the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay during World War II

Source: Library of Congress, Fort Story coast defense. A sixteen-inch howitzer at Fort Story, Virginia and fighting men who operate it (1942)

at the start of the Cold War, Nike missiles in Fairfax County were used to defend Washington, DC

Source: Library of Congress, Nike missile installation, Lorton, Virginia (May 1955)

Virginia has always needed some sort of a navy to defend itself from sea-borne attack. Weapons capable of actually blocking entrance into the Chesapeake Bay were not available until World War II. Ships were needed to engage other ships on the water - and the failure to have a defensive naval force until the Spanish-American War left Virginia open to invasion more than once.

Virginia and the United States declined to invest in building and maintaining a standing navy to guard the bay for the first 300 years of European settlement. In the colonial era and during the Confederacy, Virginia assembled the best sailing fleet it could on short notice only after a threat was clearly recognized - and always too late to provide much protection. Just as Powhatan was unable to block the English from sailing up the James River in 1607, Virginians were unable to block the British in the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812, and were unable to block invasion by the Yankees in 1862-65.

Union Navy gunboats moved from the Chesapeake Bay into the James River and threatened Richmond between 1862-65

Source: National Archives, Gunboats on James River, Va. 1864-5

Chesapeake Bay on March 24, 2000

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

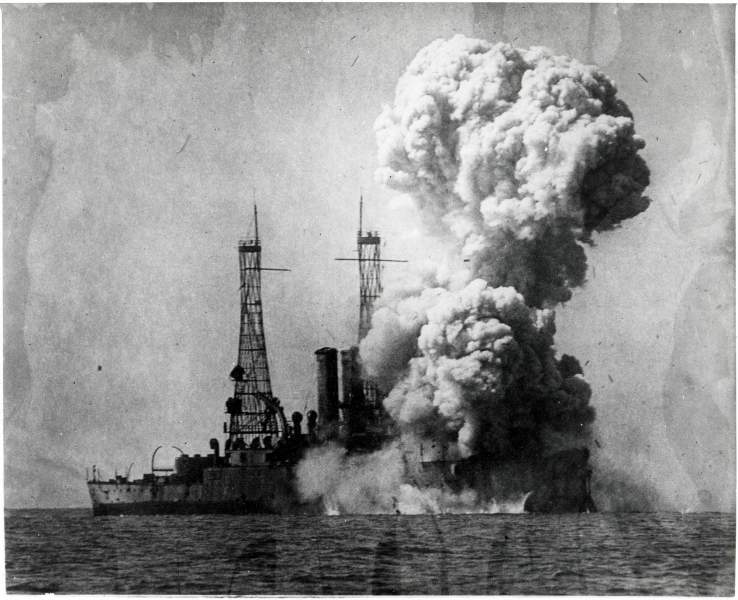

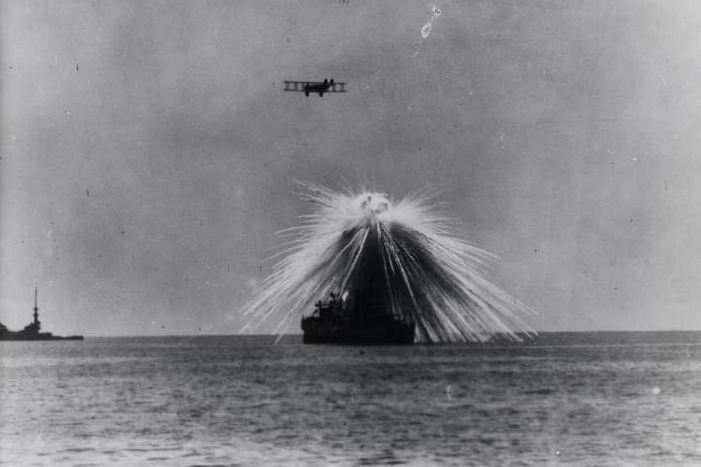

once Gen. Billy Mitchell demonstrated that bombers could sink battleships, the defense of the Chesapeake Bay shifted from artillery at forts to aircraft that could patrol far into the Atlantic Ocean

Source: Smithsonian Institution, Events, 1921, USA, Virginia (VA), US Army Air Service Ship Bombing Trials

German and obsolete US warships were sunk in the Chesapeake Bay after World War I, as aerial bombing was proven to provide effective defense

Source: Smithsonian Institution, The German battleship 'Ostfriesland' after a direct hit by one of the Army MB-2 bombers

the ability of aircraft to sink ships altered the strategy for protecting the coastline from naval attack

Source: Smithsonian Institution, The Ostfreisland being bombed in the Chesapeake Bay by a Martin MB-2 during ship bombing trials run by William L. "Billy" Mitchell