Convention Army prisoners built shelters at Charlottesville in early 1779, similar to winter camps built by George Washington's army at Valley Forge

Source: National Park Service, What Happened at Valley Forge

Convention Army prisoners built shelters at Charlottesville in early 1779, similar to winter camps built by George Washington's army at Valley Forge

Source: National Park Service, What Happened at Valley Forge

Between the start of the shooting at Lexington and Concord in 1775 and the Peace of Paris in 1783, 13,000 British and German auxiliaries were captured by the rebelling colonists There was a conscious effort to care for them according to the rules of war as defined by European nations. That approach was intended to demonstrate the colonies were forming a legitimate government that should be recognized officially, and that it would be appropriate for France and Spain to provide support against their rival Great Britain.1

During the American Revolution, the rebelling colonists captured their first British soldiers on April 19, 1775 while they marched back to Boston from Lexington and Concord. Other captives were seized in New England when small British vessels came ashore and local residents caught Royal Navy sailors unprepared. They were kept in local jails and houses as prisoners of war, not as criminals.

General Thomas Gage in Boston took a different approach to the people his army captured. They were shackled and kept in the local jail or on ships converted into prisons. Gates considered the rebel colonists to be traitors, not prisoners of war. George Washington objected to the rough treatment, but Gage ignored his letters.1

A large batch of British Army soldiers were captured when Massachusetts militia commanded by Benedict Arnold and the Green Mountain Boys under Ethan Allen seized Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Saint-Jean in May 1775.

The prisoners from Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Saint-Jean were sent from Canada to Connecticut and New York, then later transferred to Pennsylvania. Farmers near Lancaster, York, Carlisle, and Reading had to adjust to having large numbers of captives in their area for the next eight years. Before the Peace of Paris was signed in 1783, 13,000 British and German auxiliaries would be captured.1

The first British prisoners captured in Virginia came from the Royal Navy. The support tender Liberty was pushed by a hurricane onto the shoreline at Hampton on September 2, 1775. Local residents seized six British crew members. Governor Dunmore, who was living on a British warship after fleeing Williamsburg in June, demanded their release. The Hampton residents returned the crew members, but sent two enslaved runaways who were also captured from the boat back to their Virginia plantations.2

"Anniversary of the 1775 Battle of Hampton," Mariners Museum, October 26, 2017, https://www.marinersmuseum.org/2017/10/anniversary-1775-battle-hampton/; Michael Cecere, "A Tale of Two Cities: The Destruction of Falmouth and the Defense of Hampton," Journal of the American Revolution, September 9, 2015, https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/09/a-tale-of-two-cities-the-destruction-of-falmouth-and-the-defense-of-hampton/ (last checked August 16, 2025)

In 1776, two Virginia Navy ships captured the HMS Oxford in the Chesapeake Bay. The British ship was bringing over 200 Scottish Highlander troops to reinforce Lord Dunmore. The Fifth Virginia Convention ordered the prisoners to be brought to Jamestown and offered an opportunity to join the Virginia army. Almost all rejected the proposal, and were dispersed to be held prisoner in 14 separate counties. Local Committees of Safety were directed to distribute the Scottish Highlanders among the inhabitants in those counties, so the costs of their care could be offset by their work on farms.3

Michael Romero, "Virginia's Unconquered Liberty," Naval History, Volume 32, Number 5 (October 2018), https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2018/october/virginias-unconquered-liberty; "Opinion of the Committee of Safety regarding Scotch prisoners, 1776 June 21 (laid before the Convention on 22 June 1776)," Library of Virginia, https://rosetta.virginiamemory.com:443/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE3849590 (last checked August 14, 2025)

Virginians seized Cahokia, Vincennes and Kaskaskia in the Illinois Country in 1778. The residents were supportive of the Americans and the British had withdrawn their forces, so the victories created no "prisoners." Instead, inhabitants chose to take an oath of allegiance provided by George Rogers Clark.

The British reoccupied Vincennes in 1778. Clark recruited French militia from Kaskaskia plus Virginia militia, and Fort Sackville at Vincennes was surrounded. Two French-Canadians and four Native Americans were captured outside the fort. The French were released, but the four Native Americas were executed with tomahawks in full view of the people inside the fort the night before the British surrendered.

When Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton surrendered the fort, the French-Canadians who were supporting him were paroled. Hamilton and the other British officers, plus 18 privates, were marched 1,200 miles to Williamsburg. Hamilton was incarcerated in the colony's jail (now recreated by Colonial Williamsburg) and later in Chesterfield County. He was treated as a common criminal rather than as a prisoner of war, accused of being a "hair buyer" who had encouraged Native Americans to scalp Americans on the frontier.2

Governor Thomas Jefferson resisted requests from George Washington to treat Hamilton and two other British officers as prisoners of war, rather than as common criminals. A special board convened to assess the situation:3

Hamilton was ultimately exchanged, in a deal pushed by George Washington but opposed by Governor Thomas Jefferson.

During the American Revolution, the Continental Army and Virginia militia captured British soldiers, German Auxiliary Troops, and Loyalists. Loyalists were treated more harshly than organized troops; not all were made prisoners. Virginians who fought in South Carolina at the 1780 Battle of Kings Mountain brought home no prisoners from the Tories who fought with Major Patrick Ferguson. They remembered the killing of those in the 3rd Virginia who had surrendered at the Battle of Waxhaws to Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton's militia earlier in 1780, and applied "Tarleton's quarter" to the Tories.

In contrast, General Nathanael Greene had the uniformed British troops captured at the Battle of Cowpens in January, 1781 marched to Winchester.4

British and German officers and enlisted men typically were marched from battlefields to prisoner of war camps, and kept there until exchanged. The most-southern American prisoner of war camps were located in Northern Virginia, which was the closest part of the state to the main theater of war until 1780.

Because the British had full control of the sea, prisoner of war camps were placed far from the head of navigation, the Fall Line. That reduced the risk of British ships bringing a raiding force upstream in order to recapture prisoners. As British troops moved into Virginia in 1780, prisoners were relocated to Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Prisoner of war camps were located in regions with many farms. That facilitated gathering supplies, particularly food. At the time of the American Revolution, warring nations were responsible for providing supplies for their prisoners. Where access was limited, British officials were supposed to pay for the support food, clothing, and other supplies provided to the prisoners by the Americans. Similarly, Americans were supposed to pay for support provided to their troops in British prisons.

Not all of the German troops were "Hessians." Six different principalities in what today is Germany provided troops to Great Britain. The German rulers who contracted with King George III to provide troops were:

Charles I, Duke of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel

Frederick Augustus, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

Frederick, Prince of Waldeck

Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel

William, Count of Hesse-Hanau

Charles Alexander, Margrave of Anspach-Bayreuth

During the American Revolution, 1,200 German auxiliaries died in battle and over 6,000 died from disease. At the end of the war, 17,000 returned to Germany, but 5,000 chose to stay in North America.5

The American victory at Trenton on December 26, 1776 resulted in 1,000 captive German auxiliaries. Most were taken to Lancaster, but roughly 26 officers and an equal number of their servants were taken to Virginia's first prisoner of war camp at Dumfries. The Continental Congress journal for January 14, 1777 includes:6

George Washington was unsuccessful in efforts to exchange five of the officers for Maj. Gen. Charles Lee. The British agreed only to informal exchange cartels, resisting recognition of the Continental Congress as a legitimate government, until 1782.

They were marched there in January, 1777.

General Howe sailed up the Chesapeake Bay and unloaded his army at Elkton, Maryland in August, 1777, increasing the risk that the British might launch a raid to recapture the German officers and soldiers at Dumfries. The prisoners were marched to Winchester, 60 miles further inland and on the other side of the Blue Ridge.7

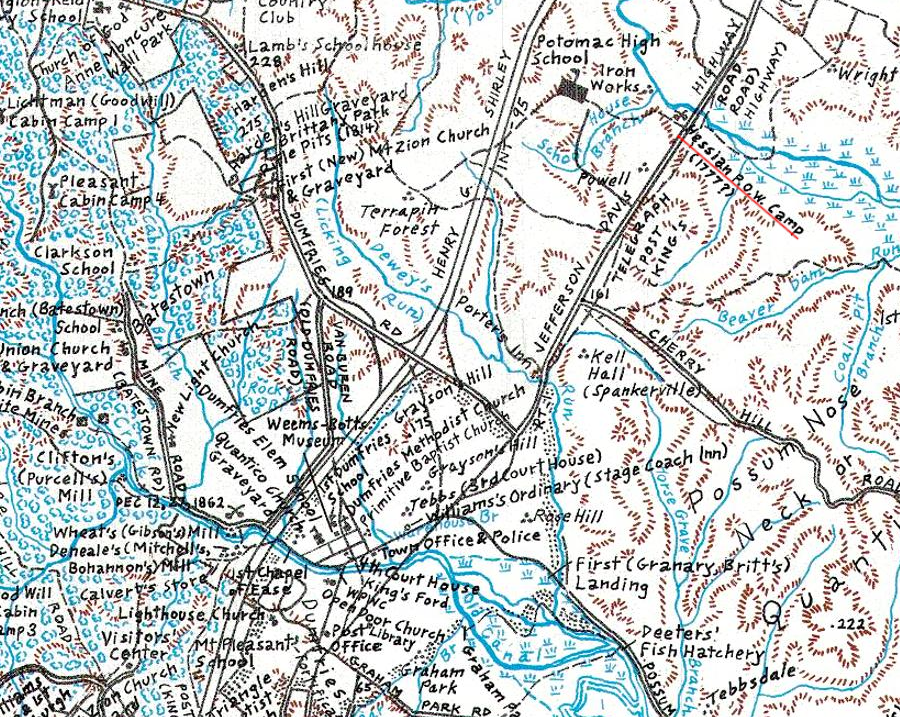

officers of German auxiliary regiments were brought to Dumfries in 1777, and were initially kept in a camp on Powell's Creek before finding housing in town

Source: Historic Prince William, Eugene M. Scheel Historical Map

The 2,139 British, 2,022 Germans, and 830 Canadians who General John Burgoyne surrendered at the Battle of Saratoga in October, 1777 were not supposed to end up imprisoned in Charlottesville. The terms of surrender for the "Convention Army" included shipment to Britain, but the Confederation Congress voided the deal. The Canadians were sent back north, but the rest of the soldiers were, over the next five and a half years, forced to march 1,100 miles. Roughly 85% of General John Burgoyne's army ended up dying from disease and starvation, or deserting and starting a new life in America.

Prisoners from Saratoga were marched initially to Boston. They were kept there for a year, but eventually wore out their welcome. American prisoners were kept in poor conditions on prison ships in New York harbor, and as the war dragged on there was less and less sympathy in Boston for the captives. There were also fears of a British raid that would liberate the prisoners.

After lobbying by John Harvie of Albemarle County, a delegate at the Continental Congress, the Continental Congress decided on October 16, 1778 to send the Convention Army to Charlottesville. Harvie anticipated that a prisoner of war camp would build roads, clear the forest, and make his land more valuable after the war ended.

Starting on November 9, 1778, the Convention Army captives were marched 700 miles south. They moved in six divisions, three British and three German, marching one day behind each other. When the prisoners were crossing the Hudson River in December 1778, General Sir Henry Clinton sought to intercept and rescue the Convention Army. His ships sailed up the Hudson River too late, however.

On the march, 299 British and 280 German troops escaped into the countryside. During the year spent in Massachusetts, 1,368 in the Convention Army had deserted. Some intentionally joined the American army in order to get close to British lines, so they could desert a second time and return to the Regulars.8

The Convention Army prisoners crossed the Potomac River and reached Loudon County at the end of 1778. Their route in Virginia between Loudoun County to Charlottesville between January 2-January 14 passed through Leesburg, Prince William County, Warrenton, Culpeper County, and Orange Court House.

Eventually 2,263 British and 1,882 German prisoners arrived at Albemarle County. The 4,000 men were forced to build their own shelters, at what today is the Ivy Farm subdivision on Barracks Road. Officers were allowed to live nearby, even as far away as Staunton. Several built their own small houses near the enlisted men's barracks. Baron Friedrich Adolf Riedesel lived next to Monticello.

Enlisted men were hired out to local farmers. Colonel William Preston came up from his plantation near Blacksburg to obtain one of the Hessian soldiers. Henry Linkous never returned to Hesse-Kassel. He eventually acquired 160 acres of Smithfield Plantation and fathered nine children before he died in 1822. The Linkous family is still prominent in Montgomery County.

In October, 1780, British forces led by Major General Alexander Leslie occupied Hampton Roads. To prevent a British raid that might free the British captives in the Albemarle Barracks near Charlottesville, they were marched to Fort Frederick, Maryland, starting on November 20, 1780. The German troops were kept over the winter at Albemarle Barracks, but sent to Winchester on February 20, 1781.

the Convention Army captured in 1777 ended up being imprisoned at Charlottesville

Source: University of Michigan, William L. Clements Library, Plan of part of the province of Virginia

The British prisoners were moved again in June, 1781 to Reading, Pennsylvania. Some were still in Frederick when General "Mad Anthony" Wayne marched from Pennsylvania to Virginia to resist the British forces under Lord Cornwallis who were marching through central Virginia.

Late in the war, there were engagements in which few prisoners were captured by Continental Army soldiers who were angry at the behavior of the British, especially the "massacre" of Virginia soldiers who were trying to surrender at the Battle of Waxhaws. Early in 1781 George Washington wrote to the Compte de Rochambeau:9

The British soldiers captured at Cowpens were sent initially to Winchester. and then to Pennsylvania over the objections of Pennsylvania officials. Privates and noncommissioned officers were kept at Camp Security in Pennsylvania. The Germans captured at Cowpens were left in Albemarle County, since they were considered less likely to escape in order to join a British raiding party.10

The American-French victory at Yorktown in October, 1781 required finding places to keep the British and German prisoners. They were marched to Fairfax Court House, where they were divided into two groups. One was sent to Winchester, and the other group to Fort Frederick in Maryland. The Winchester prisoner of war camp was closed in 1782. Those prisoners were set to Fort Frederick, and then to camps in Pennsylvania.11

The Articles of Capitulation accepted by General Cornwallis specified:12

The two locations chosen by George Washington were west of the Blue Ridge, safe from a British assault from the sea. Winchester was 240 miles away from Yorktown, and the march to Fort Frederick in Maryland was also a two-week march away.

Among the 3,029 prisoners sent to Winchester were 948 German auxiliaries. There were 696 German auxiliaries among the 2,924 sent to Fort Frederick in Maryland. An additional 1,300 sick and wounded stayed near Yorktown until they recovered enough to go to prison.

Both Winchester and Fort Frederick were in areas with a high percentage of German settlers. Throughout the American Revolution, the American strategy was to encourage the German auxiliaries to defect by having German-speaking prisoners work on farms with German-speaking settlers.13

Not all of those captured at Yorktown were sent to prisoner of war camps. The Articles of Capitulation specified that some German and British officers would accompany the prisoners, so there would be commanders with authority to maintain control over the regiments. There was a surplus of officers, so many were granted parole along with Cornwallis and provided with transportation by a truce ship to New York. The British officers maneuvered to gain parole and freedom rather than imprisonment, and the British prisoners left Yorktown with fewer than the authorized number of British officers.14

British officers were allowed to retain personal baggage. George Washington promised to provide wagons to carry that baggage for officers going to prisoner of war camps, if wagons were available. However, officers could not retain property that had been seized from Virginians. The owner of a stolen horse discovered Col. Banastre Tarleton was riding it. As recorded in an American officer's diary:15

Cornwallis was allowed to transport "such soldiers as he may think proper" to New York and Europe without examination by the Americans. This allowed the British to move all the American deserters out of Yorktown safely, while Washington avoided the political difficulties of punishing men who had relatives supporting the American cause in the civil war.16

Some of the men and women who had abandoned enslavement on plantations and joined the British, as Cornwallis marched through Virginia, may also have been shipped out of Virginia in this manner. Cornwallis had expelled about 2,000 of the formerly enslaved people from his camp at Yorktown, trying to conserve supplies. They had been trapped between the lines, or managed to get into nearby woods before the surrender. George Washington ordered them to be rounded up and returned to their masters.17

One American deserter found in the British camp received the severest form of military discipline. The General Orders issued by George Washington on October 28 included:18

The march from Yorktown started on October 21, 1781. Prisoners reached Winchester on November 5. They crossed the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg on November 1, and the Shenandoah River on November 4.19

After a winter in Winchester, the British troops were transferred to the Frederick, Maryland and then to camps in Pennsylvania. All the German auxiliaries were sent to the "Hessian Barracks" in Frederick, Maryland, at the beginning of 1782, after the British soldiers there were moved to Pennsylvania. The 1,500 Germans were then sent to Pennsylvania.20

The largest number of Virginians to be captured in the Revolutionary War occurred when General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered his Continental Army after the siege of Charleston, South Carolina. Nearly 900 men in the 1st Virginia Brigade and 600 men in the 2nd Virginia Brigade ended up imprisoned in ship within Charleston Harbor. The common soldiers died from poor food and sanitation on the prison ships, while officers were eventually exchanged.

Many of the Americans captured by the British during the American Revolution were transported to New York City and imprisoned in old ships. Conditions were horrible, and 50-70% of those prisoners died. In the Revolutionary War, more Americans died as prisoners of war than in battle.21