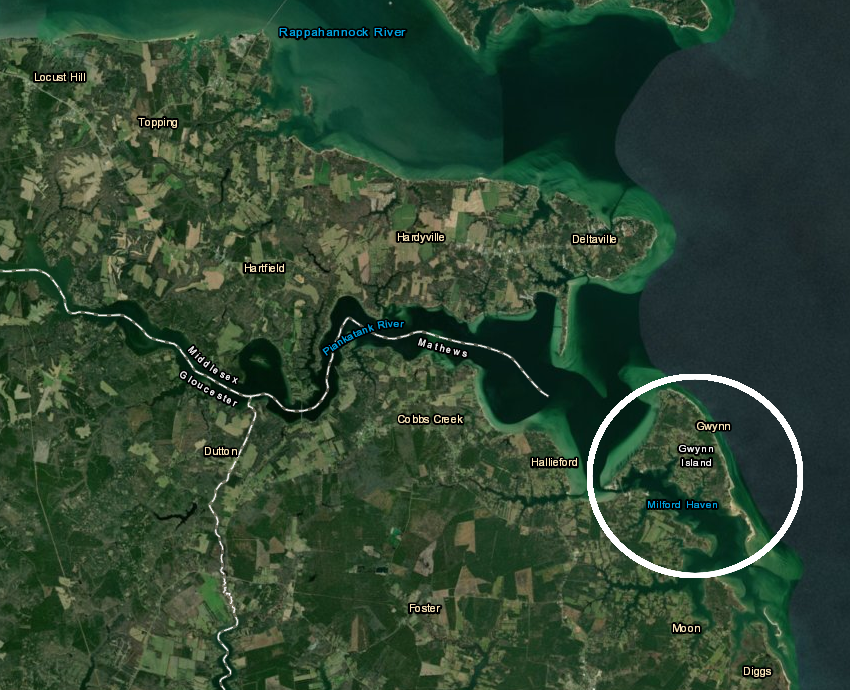

Lord Dunmore fled to Gwynn's Island in 1776, before finally abandoning Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Lord Dunmore fled to Gwynn's Island in 1776, before finally abandoning Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia's colonial governor fled Williamsburg on June 8, 1775. He stayed on British warships, which roamed through the Chesapeake Bay.1

On November 7, 1775, Dunmore declared martial law and issued an emancipation proclamation granting freedom to enslaved men who joined the British side. British troops occupied Norfolk, Virginia's largest city, where Dunmore recruited loyalists to fight the rebellious colonists. He organized them into the Queen's Own Loyal Virginia Regiment. He organized the former slaves into an Ethiopian Regiment commanded by white officers.2

After the Battle of Great Bridge, the British realized that they lacked enough soldiers to keep using Norfolk as a base of operations. They shelled the city and set fires to many buildings on January 1, 1776, abandoning their first land base in Virginia. Virginia rebels burned the rest of Norfolk in January, to retaliate against Scottish merchants in the town who had supported King George III and to prevent British forces from using the town as a future base.

After the destruction of Norfolk, the fleet stayed in the Elizabeth River around Tuckers Mill at Portsmouth. Foraging expeditions went onshore to obtain fresh water and food, using the local knowledge of former enslaved men who had fled to the British after Dunmore issued his Emancipation Proclamation. The ships provided an effective platform for raiding waterfront plantations. Dunmore's presence required Virginia to keep militia in the region rather than send reinforcements to George Washington's army near Boston and New York.

Rebels in Virginia planned to trap the British fleet by placing artillery along the riverbanks. The Virginians also planned to send fireships into the middle of the enemy fleet, so rigging would burn and the ships would be disabled. Operational security was poor, however, and Lord Dunmore learned of the plans.

fireships are a form of asymmetric warfare, where the better technology of one side can be destroyed by a low-tech solution of the other side

Source: New York Public Library, The Phoenix and the Rose engaged by the enemy's fire ships and galleys on the 16 Augst. 1776

On May 26, 1776, the British abandoned their last land base at Tucker's Point near Portsmouth and sailed their 100-ship fleet out of the Elizabeth River. They pretended initially to sail out of the Chesapeake Bay into the Atlantic Ocean, but turned north instead. The next day they arrived at Gwynn's Island, 35 miles from Norfolk at the mouth of the Piankatank River.

The island was named after an early colonist, Hugh Gwynn. He acquired it using headright claims in 1635, though legend says Powhatan gifted the land to him earlier in 1611 after Gwynn saved Pocahontas from drowning. In 1776 the owner of an 1,160-acre plantation covering roughly half of the island, John Randolph Grymes, attracted Governor Dunmore by claiming there was strong loyalist support in the area.

Less than half of the Gwynn's Island population was white. When the British fleet arrived, most of those white residents fled to the mainland. The enslaved people knew of the promise of freedom if they supported the British, though it is unlikely the plantation owner had chosen to highlight that option for people he claimed as "property."

Dunmore's fleet landed marines from three warships, plus members of Queen's Own Loyal Virginia Regiment and the Ethiopian Regiment on May 27. Disease had reduced their forces. Out of his 500 men, there were only 200 that a British captain described as "effective."

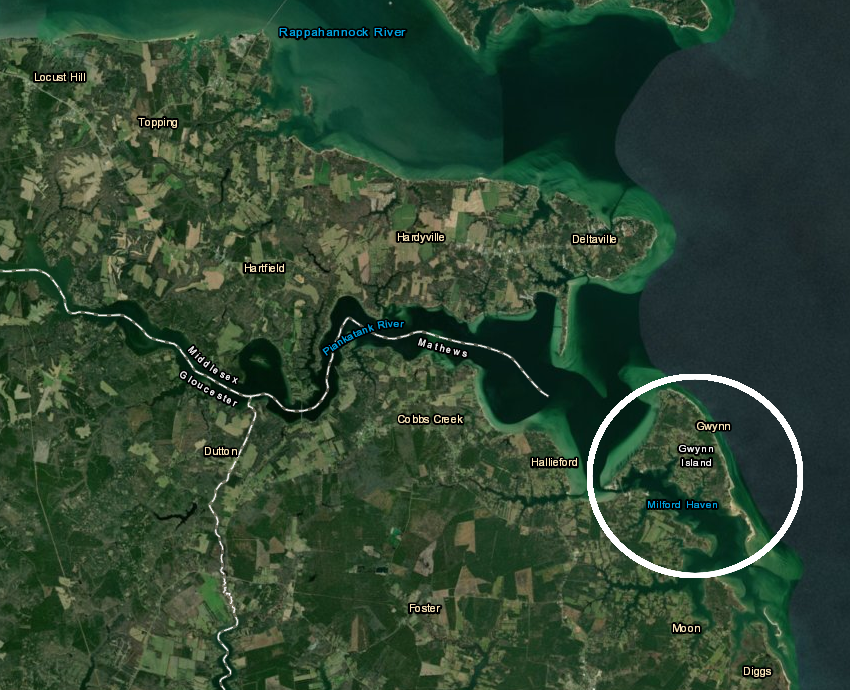

Local and state militia, Americans rebelling against their colonial governor, assembled on the mainland. They were separated from Dunmore's forces on the island by the Milford Haven channel; it was a narrow but effective barrier. The head of the Virginia Committee of Safety reported:3

Dunmore had hoped to recruit 2,000 people into the Ethiopian Regiment, but smallpox and fever killed many. The governor reported:4

Because the number of surviving Queen's Own Loyal Regiment and Ethiopian Regiment recruits was so low, the warship captains had to send Royal Marines onto the island to help build and defend the earthworks on the western edge of Gwynn's Island. Disease followed the fleet from Hampton Roads. Among those buried on Gwynn's Island after dying from smallpox was Andrew Sprowle, owner of Gosport Yard in Portsmouth.

The channel separating the island from the mainland was 200 yards wide. The obvious route for an American attack was to cross Milford Haven, but the ships of the British Navy had plenty of cannon and full control over the water. The officers concluded:5

after receiving reports of the battle, Thomas Jefferson sketched how Milford Haven separated Gwynn's Island from the mainland of Gloucester County

Source: Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson, June-July 1776, Map of Action at Gwyn's Island, Chesapeake Bay

The Virginia Navy captured small ships used by the British to transport people and military supplies, and for communication. The British warship HMS Fowey was able to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to Annapolis and evacuate Maryland's royal governor, Robert Eden on June 26, 1776.

Governor Eden had maintained a working relationship with the Council of Safety in Maryland until April, 1776. James Barron, captain in the Virginia Navy, intercepted a ship carrying correspondence betweeen Governor Eden and Lord Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London, suggesting Eden was providing intelligence about key leaders of the American insurrection.

Virginians called for Eden's arrest, but the Marylanders simply required that he leave the colony. Governor Eden and his retinue joined Governor Dunmore on Gwynn's Island.

The Virginia Navy, led by Captain James Barron and based at Hampton, was able to intercept some British reinforcements sailing to Gwynn's Island. A major success came in June 1776, when the Virginia Navy captured a transport loaded with over 200 Highlanders sent to reinforce Lord Dunmore. It was the second time those unlucky soldiers were seized while crossing the Atlantic Ocean from Glasgow.

A ship of the American Continental Navy had captured their vessel earlier off the Grand Banks, but they had regained control and reached the Chesapeake Bay. Captain Barron's sailors were outnumbered, but his cannon destroyed the British ship's mast and it had to surrender. The Highlanders ended up as prisoners in Jamestown, not as reinforcements on Gwynn's Island.6

Half of the 7th Virginia Regiment was based in Gloucester County, providing a force that could confront raiders from the warships. Gwynn's Island was part of Gloucester County when the British occupied it. The island is in Mathews County today, but that county was not established until 1791.

The 7th Virginia Regiment moved to the shoreline closest to the island, where their muskets could reach the British. Guns on the warships supplemented the artillery which the British moved to the island; their shelling forced the American rebels to limit their fire for six weeks.

While the fleet was at Gwynn's Island, a British warship sailed up the Chesapeake Bay to evacuate the royal governor of Maryland. The Maryland convention allowed Robert Eden to leave peacefully. He was rescued by the HMS Fowey, the same ship to which Dunmore had fled when he left Williamsburg in the middle of the night.

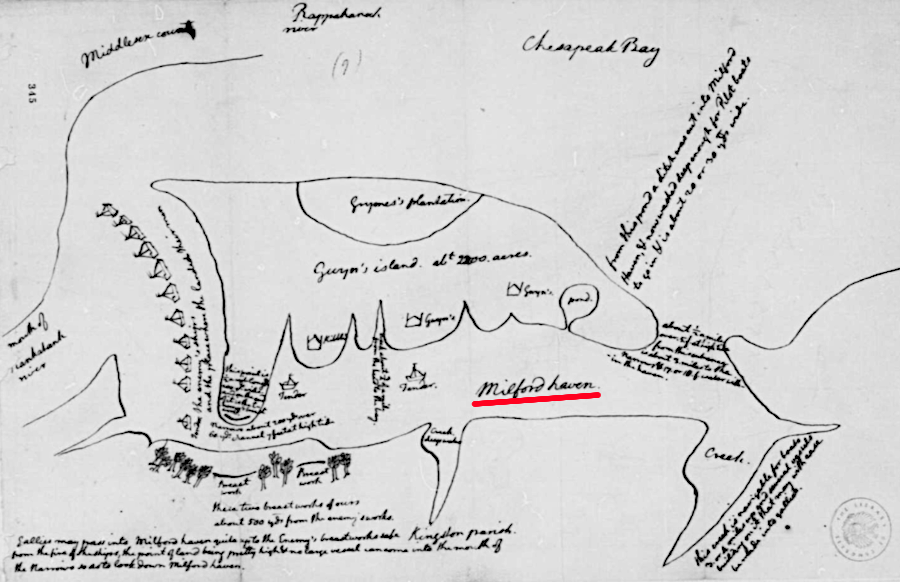

General Andrew Lewis brought more men as reinforcements to Gloucester County, but most importantly he brought artillery. A French volunteer, Captain Louis d'O'hickey Arundel (Dohickey Arundel in the English records) had been training the Virginia artillery battalion for a month.

The Virginia forces moved two eighteen-pound cannon into an upper battery (now site of the United States Coast Guard Station Milford Haven), and four nine-pound cannon into a lower battery (site of Morningstar Marinas). Their positions were on what became known as Cricket Hill, after Lord Dunmore derisively described the rebels as "crickets."

The Virginia artillery opened fire on July 9, 1776. Neither side was aware yet that the Continental Congress in Philadelphia had just declared independence. The British had not recognized the batteries were being constructed, and Lord Dunmore's flagship was anchored just 500 yards offshore.

The artillery fire from the Virginia troops was accurate enough to disable British artillery in the fort on the island, and shells killed sailors on the warships. The third shell sent a wooden splinter into Lord Dunmore's leg and broke the china that he had managed to bring with him when fleeing from the Governor's Palace.

Dur to the shells from the "crockets" on the mainland, the British ships quickly moved out of range. Some has to abandon their anchors in order to avoid further damage. Without time to hoist sails, sailors got into small boats and attached ropes to the larger ships. The men had to row hard, in order to tow the larger ships out of danger.

The troops stationed on the island near Cricket Hill left their earthworks and marched to the eastern side of the island, which the artillery shells could not reach. That evening, everyone boarded the ships and left the island, including the remaining able-bodied members of the Ethiopian Regiment and the loyalist plantation owner John Randolph Grymes.

once the artillery on Cricket Hill opened fire, the British abandoned Gwynn's Island

Source: US Geological Survey, Mathews VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1917)

The only American casualty occurred when Captain Louis d'O'hickey Arundel fired an experimental wooden mortar made from a pine log. It exploded, killing the artillery commander in his first and last military engagement.

Rather than resist or surrender, the British evacuated in the evening. On the morning of July 10, the rebels used small boats to cross Milford Haven. Three small British ships placed in Milford Haven to block access to Gwynn's Island were captured. There was no organized resistance on the island; all the remaining soldiers and loyalists there (including Andrew Sprowle, owner of the shipyard at Gosport) were debilitated and dying from disease.

John Page wrote to Thomas Jefferson, describing the event as "a most compleat drubbing."7

The Americans recognized that disease had caused the greatest mortality in the British camp. They did not choose to occupy the island after the British left, for fear of spreading smallpox and fever to the Virginia troops. A news report published in Williamsburg on July 20, 1776 included:8

The fleet stayed in the Chesapeake Bay for a month. An effort to land at St. George's Island, on the Potomac River in Maryland, was blocked twice. It became clear that Dunmore was unable to seize and control enough land to establish a safe base in Virginia. Cannon had finally been placed on the banks of the Elizabeth River, and later in 1776 Fort Nelson would be completed on Windmill Point (now occupied by the Portsmouth Naval Hospital). There was no possibility of Dunmore returning and rebuilding Norfolk, which had been a Loyalist stronghold and effective staging area for recapturing the rebellious colony.

General Clinton was unable to capture Charles Town in South Carolina, and Clinton chose to sail to New York City rather than the Chesapeake Bay. Dunmore accepted that he would not be reinforced and restored to rule the colony, and would have to return to England.9

The British fleet left the Chesapeake Bay on August 15, 1776. Some of the remaining ships went to St. Augustine, while Lord Dunmore sailed with 25 other ships to New York City. With no British threat of invasion after the Battle of Gwynn's Island, the Virginia regiments with men who had volunteered to serve for a year were sent north to support George Washington's siege of New York.

The main plantation owner on Gwynn's Island, John Randolph Grymes, fled with Lord Dunmore to New York. Unlike many other loyalists, he did not go directly to England after abandoning Virginia. He joined the Queens Rangers, a loyalist regiment, and was wounded while fighting for the British at Brandywine in 1777. He finally crossed the Atlantic Ocean and eventually found a wife in London.

Lord Dunmore hoped to stay in New York, then lead a larger force back to Virginia to recapture the colony. Gen. William Howe did not support that strategy; his focus was on New England initially, then on the Carolinas. British troops were not sent to attack Virginia until May 1779, when ships under Commodore George Collier and troops under Gen. Edward Mathew captured supplies at Suffolk and burned the shipyard (again) at Gosport.

Governor Dunmore eventually sailed back to England. He continued to be paid as the royal governor of the colony until the end of the American Revolution.

Dunmore joined an expedition with Loyalist refugees that sailed to America in 1781. However, Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown before Dunmore had crossed the ocean. Dunmore and his loyalists landed instead at Charleston, South Carolina.10

Gwynn's Island is the last place where a royal governor set foot on Virginia soil.

Today the Milford Haven ship channel is no longer a barrier to access from the mainland, now organized as Mathews County. The Route 223 bridge was constructed over the Narrows in 1939. It has a movable swing span for ships needing more than 11 feet vertical clearance. Traffic had reached 2,000 vehicles per day across the bridge when it was rehabilitated in 2014.11

Remains of the British earthworks on the island, named Fort Hamond after the senior British naval officer, survived for almost two centuries. They were mostly destroyed in two phases, during construction of the Coast Guard Station in the 1960's and an adjacent marina in the 1980's.12

the Route 223 bridge crosses the Narrows from Cricket Hill to Gwynn's Island

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online