Why Was Virginia a Military Target in 1781?

without the French fleet, British reinforcements could have ended the siege of Yorktown in 1781

and the successful American Revolution might have ended up the failed American Rebellion

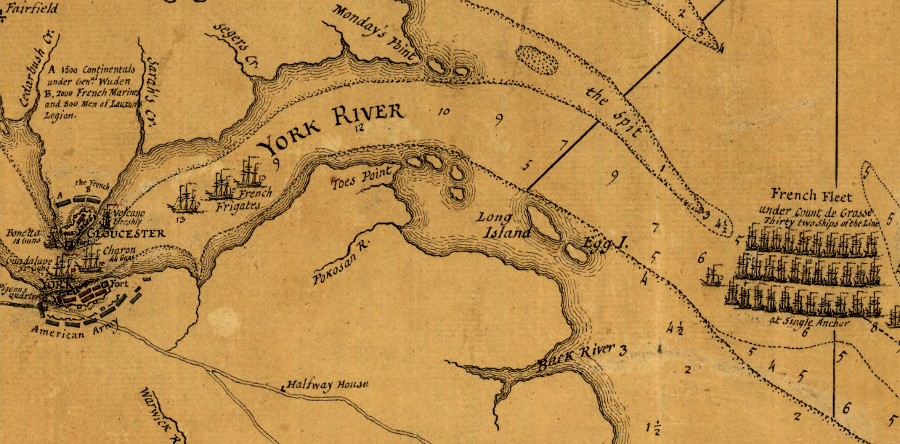

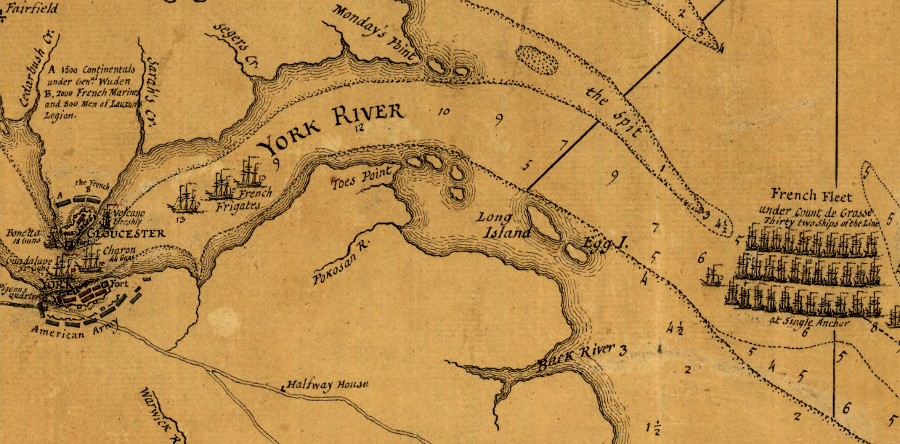

Source: Library of Congress, A Plan of the entrance of Chesapeak [sic] Bay, with James and York Rivers (1781)

The Revolutionary War shooting war started in Massachusetts. Virginians played a leading role in political agitation leading to the shooting war and ultimately independence, but little fighting occurred in Virginia for the first 5 years of the conflict.

Massachusetts caught the attention of the British years before gunshots at Lexington and Concord, with the "massacre" in Boston in 1770 and the "tea party" in 1773. The port of Boston was closed to trade, stimulating two Virginia communities still in existence today to name themselves Boston in solidarity. (To distinguish itself from the Culpeper County community, the one in Halifax switched its name to "South Boston.")

In 1775, Virginia politicians in the House of Burgesses forced the colonies top London-appointed official, Lord Dunmore, to prepare for a potential civil war. The appointed governor first seized the colony's gunpowder stored at the "magazine" in Williamsburg, to disarm any potential rebels. That seizure triggered a group of agitators and citizens to march on Williamsburg from as far away as Prince William County. Peace was restored briefly when Dunmore agreed to pay for the powder.

When it became clear that this dispute would not be resolved by standard political compromises between the appointed royal governor and the elected House of Burgesses, Dunmore fled the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg and moved to a British warship, the HMS Fowey. From that safe refuge, he requested troops and ships to help him recapture Virginia in late 1775.

Dunmore moved to Portsmouth/Norfolk at the very start of 1776, but his requested reinforcements were sent to Boston instead. After the Virginia rebels set fire to loyalist homes in Norfolk, Dunmore finished the job of burning the town and withdrew. In August 1776, his base of operations at Gwynn's Island in Mathews County was attacked. The Virginians built a fort on the mainland of Mathews County, which Dunmore dismissed as a fortification of "crickets," but his troops were weakened severely by sickness. Almost as soon as the Virginians began shelling Gwynn's island and Dunmore's fleet, he abandoned the rebel-controlled "colony" and never returned.1

The British knew Virginia was exposed to attack from the Chesapeake Bay, and the colony had no navy capable of defeating a British warship. However, the primary focus of the war was in the northern colonies (Pennsylvania to Massachusetts) until 1780.

British forces were forced out of Boston in March 1776, after Henry Knox brought cannon from Fort Ticonderoga placed artillery on Dorchester Heights. After retiring to Nova Scotia, British forces captured New York in August 1776. They occupied the city, with its fine harbor for the Royal Navy, until the end of the Revolutionary War.

General William Howe then drove the Continental Army south through New Jersey and across the Delaware River, but at the end of 1776 George Washington restored patriot morale and enlistments by crossing the Delaware River and winning tactical victories at Trenton and Princeton.

General Washington surrounded New York with the Continental Army from 1776-1783, but was unable to gather enough men and supplies to attack the British fortifications.

The challenge faced by the British general in charge of New York in 1776 was similar to that of Powhatan in the summer of 1609. Powhatan had plenty of supplies, while the early English colonists were trapped in James Fort and a few outlying settlements. Powhatan did not need to attack the fort. He stopped trading food to the colonists and just waited for the inevitable.

Powhatan's strategy was successful. Many Englishmen literally starved to death during the winter of 1609-10, and the colonists decided to abandon Virginia. By May 1610, even after two ships arrived from Bermuda, the English viewed their situation as hopeless and completely abandoned Jamestown. Powhatan's success was thwarted only by the last-minute arrival of Governor De La Warre with new reinforcements.

170 years later, the British in New York were better positioned than Powhatan. They had easy access to supplies and military reinforcements via the Royal Navy. The British thought a stalemate would lead to increased loyalist influence as the rebellion gradually collapsed, followed by King George III regaining control of the 13 colonies.

The British commanders in New York did not successfully attack George Washington's army outside of New York. For most of the time after 1776, they expected the rebels to lose support as the revolution failed and for loyalists to regain control of the colonies. From inside New York, the British implemented Powhatan's strategy and sought to hold on until the Americans ran out of supplies and lost the will to fight.

There were British efforts to capture North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia starting in 1776. A Royal Navy fleet sailed from Great Britain to Cape Fear to reinforce loyalists who were expected to defeat the rebels. The fleet would sail to Wilmington and restore Governor Josiah Martin to office. After the North Carolina loyalists were defeated at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge on February 27, 1776, the fleet was diverted to capture Charlestown, South Carolina. However, the ships could not get past an American fortification on Sullivan's Island in June 1776 and had to abandon the siege.

Lord Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies based in London, approved the Campaign of 1777 plan proposed by General John Burgoyne. The primary British objective that year was to cut the rebellious colonies into two separate parts and isolate the colonies north of New York from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia.

In late 1776 General Guy Carleton had marched south from Quebec on the St. Lawrence River and captured Fort Crown Royal on Lake Champlain. A British army under General John Burgoyne was to renew the march from Canada south past Lake Champlain and capture Albany, New York.

A second army under General William Howe would march north up the Hudson River from New York to meet Burgoyne at Albany. A third force of British troops, Hessians, loyalists, Canadians and Native Americans, led by General Barry St. Leger, was supposed to travel from Quebec to Lake Ontario and then march east along the Mohawk River to Albany. A base at Albany, with British control of the Hudson River and the Lake Champlain-Lake George water route north to Quebec, would split off the New England colonies.

However, St. Leger was blocked by a successful American defense at Fort Stanwix. Howe ignored the plan and took his army by ship from New York to the head of Chesapeake Bay, then marched north and captured Philadelphia, the home of the rebellious Congress. Burgoyne's isolated army was defeated and he surrendered it after the Battle of Saratoga.

Failure in the northern colonies led the British to shift their focus. Clinton was trapped in New York, so he expanded the war into the southern colonies. The new front there was expected to stimulate loyalists and convince local colonists to end the rebellion - or at least to reduce the flow of resources to the American rebels. British forces occupying the southern colonies would demonstrate the futility of continuing the rebellion. rom a military perspective, it would disrupt supplies and reinforcements for Washington's army.

The British withdrew from Philadelphia in 1778, marching across New Jersey back to New York again. The Royal Navy carried troops to Savannah, Georgia. It was captured in December, 1778, and repelled an attempt by American troops and the French Navy to seize it in 1779. As in New York, Georgia's main city was occupied for the rest of the Revolutionary War but loyalists were unable to gain control of the backcountry.

Norfolk had been destroyed at the start of 1776. After the capture of Savannah, the largest remaining center in the southern colonies was Charleston, South Carolina.

The British captured 5,000 American soldiers at Charleston, including the Virginia Line (most of the Virginians serving in the Continental Army). Clinton then sailed back to New York, and left General Cornwallis to continue the campaign. Additional victories at Waxhaws and Camden eliminated the last remnants of the Continental Army in the south.

Cornwallis marched through South Carolina and North Carolina in an attempt to to kill American soldiers, to destroy more rebel supplies, and to stimulate loyalists to seize control of southern colonies. To counter Cornwallis, George Washington dispatched Nathaniel Greene with orders to assemble a new army.

The British and Americans fought several engagements in the Piedmont of the Carolinas. After British troops won a fight and controlled the battlefield at the end of the day, Cornwallis had fewer soldiers and fewer supplies. He turned to the coast and resupplied at Wilmington, North Carolina, then aimed for Virginia in order to disrupt colonial supplies further and to punish the Virginia supporters of the rebel cause.

Virginia ended up being a target in 1781 because Cornwallis had nowhere else to go. The Southern Strategy of the British presumed that offensive operations in the southern colonies would be more productive that trying to break the stalemate around New York. Cornwallis had discovered that the patriots were winning the civil war against loyalists in the Carolinas. Marching around Virginia might stimulate loyalists there to hold onto territory after it was liberated by British troops.

Cornwallis commanded an army that had freedom of movement, in contrast to General Clinton in New York. If Cornwallis invaded Virginia, he could win military victories against the weak Virginia militia, then potentially march to New York and relive the siege there.

His alternatives were to return to Charleston or to sail to New York. If Cornwallis ended offensive operations in North America, the revolutionary patriots would increase their control outside of the four cities occupied by British troops (Savannah, Charleston, Wilmington, and New York).

British victory required restoration of loyalist colonial governments. After four years of war, the effective suppression of the loyalists in the Carolina backcountry in 1780 demonstrated there was still strong support for American independence; loyalists lacked the capacity to dominate the colonies. A military solution was required before royal governors could be reinstalled, so Cornwallis had to resupply his army at Wilmington and find places to win enough victories to break the spirit of the rebels.

Cornwallis was not the first to attack Virginia since Dunmore sailed away from Gwynn's Island. Several naval raids had seized tobacco and tobacco ships, destroyed warehouses, and frightened the politicians in the General Assembly, and Benedict Arnold succeeded in capturing Richmond in 1780. However, the 7,000 troops under Cornwallis were the largest army ever to invade Virginia - and, except for 1861-65, the last army to do so.

Cornwallis marched to Petersburg first, then ranged throughout central Virginia. Colonel Tarleton led a cavalry raid on Charlottesville, in hopes of capturing the leaders of the General Assembly. Thanks to Jack Jouett, who raced from Louisa County to Charlottesville in time to warn the politicians that "the British are coming" in the Virginia version of Paul Revere's ride, only a few members of the rebel legislature were captured. Cornwallis destroyed military supplies stockpiled along the James River, then planned to go into winter quarters.

He chose a location on the Coastal Plain with a deep harbor, where the British Navy in New York could easily provide new supplies and troops if necessary. After marching to Yorktown, Cornwallis received assurances that he would receive new troops and supplies. However, the French Fleet sailed up from the West Indies to block those reinforcements in the "Battle of the Capes," while George Washington and Count Rochambeau marched the American and French armies from New York to Virginia.

Even after discovering that the British fleet would not perform as promised, Cornwallis did not view Yorktown as a hopeless trap. He had plenty of boats, and control of the river. His escape plan was to transfer the British army across the York River from the Yorktown fortifications to Gloucester County, where Tarleton maintained a fortified base at the tip of the peninsula. Cornwallis could not control the weather, however. After moving 15% of his troops to Gloucester one night, a storm heavily damaged the British boats. Cornwallis chose to abandon the campaign and surrender, rather than to fight a futile battle and create greater casualties.

- 85 years later, Robert E. Lee would be hopelessly trapped in Petersburg. Unlike Cornwallis, Lee would leave his fortifications and march his army through the Virginia countryside for another week, seeking supplies and suffering more casualties (even after the rebel government had fled the state) before finally surrendering at Appomattox.

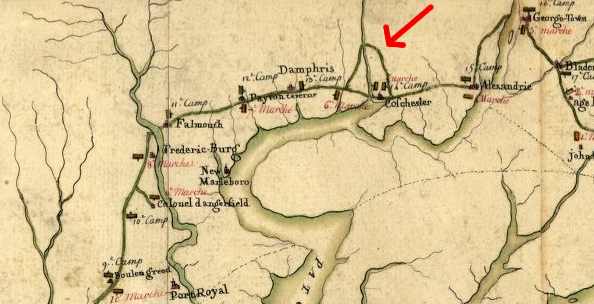

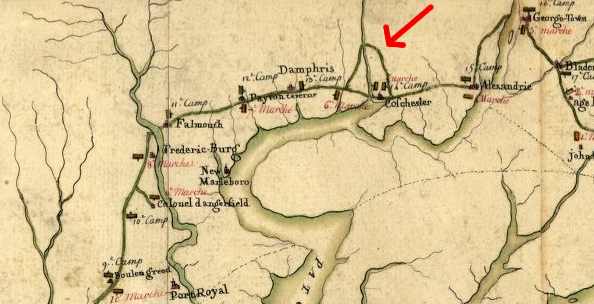

when marching from New York to Yorktown, French and American troops ferried across the Occoquan River at Woodbridge, while the wagon train went upstream to cross at Wolf Run Shoals

Source: Library of Congress, Côte de York-town à Boston: Marches de l'armée (1782)

as French/American forces built "parallels" of trench lines to locate artillery closer to Yorktown, British forces failed to escape north via Gloucester

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of siege of Yorktown, Virginia

Links

Moore House - scene of surrender negotiations at Yorktown, 1781

References

1. "Sir Hugh's Beautiful Island," Chesapeake Bay Magazine, August 2013, http://www.chesapeakeboating.net/Publications/Chesapeake-Bay-Magazine/1999/From-the-Chesapeake-Bay-Magazine-Archives/Destination-Gwynns-Island.aspx (last checked August 20, 2013)

The Revolutionary War in Virginia

Virginia Places