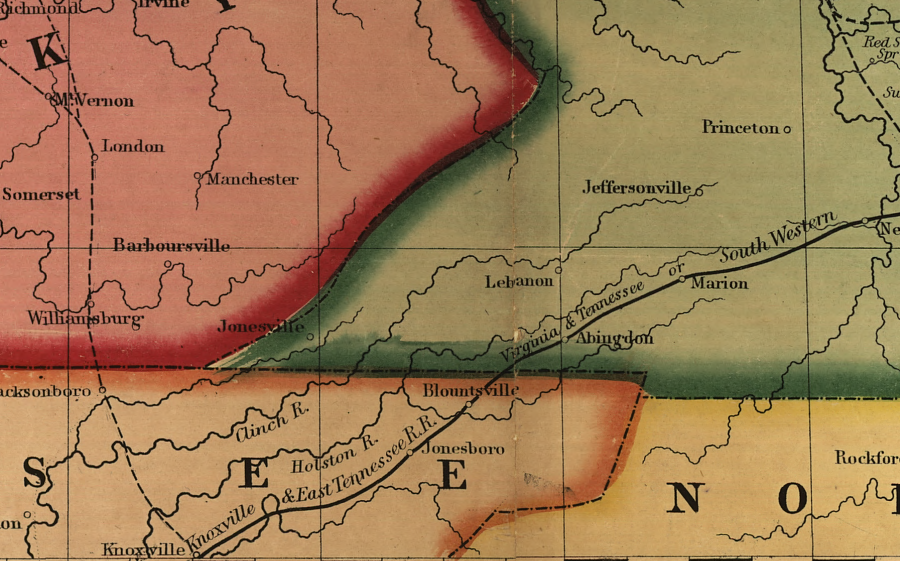

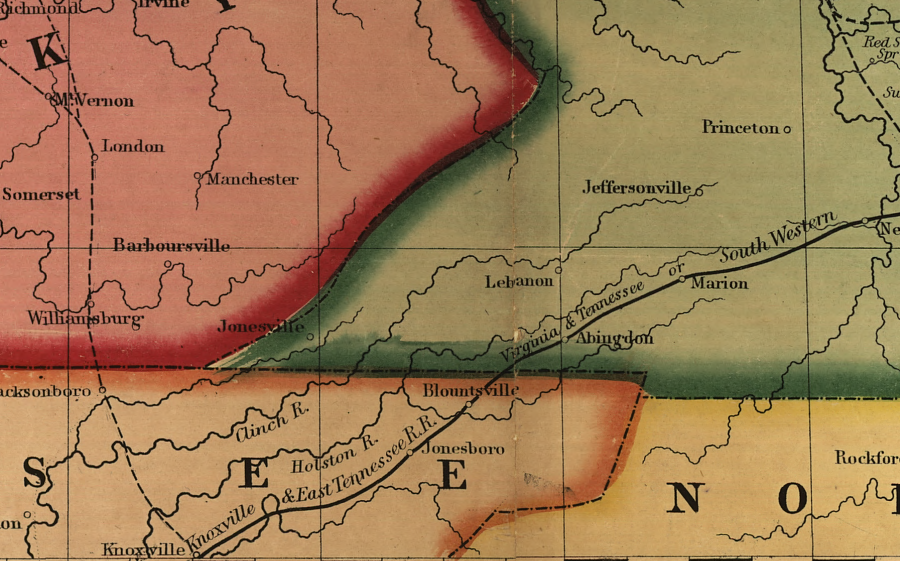

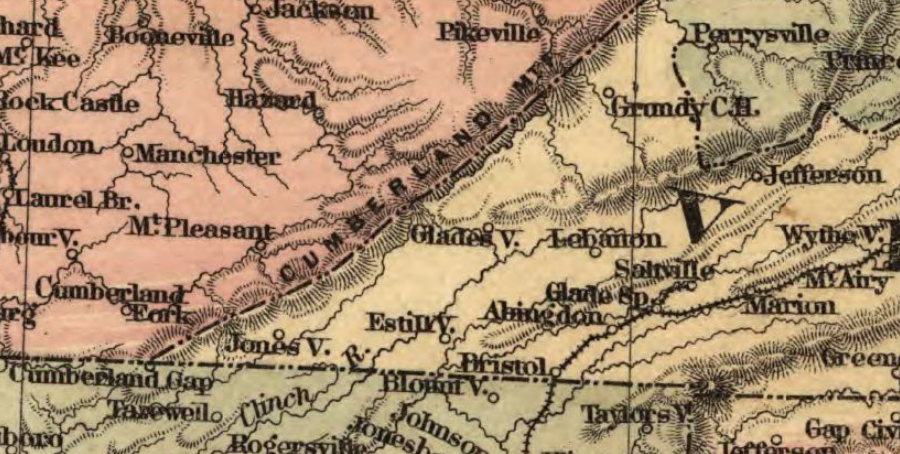

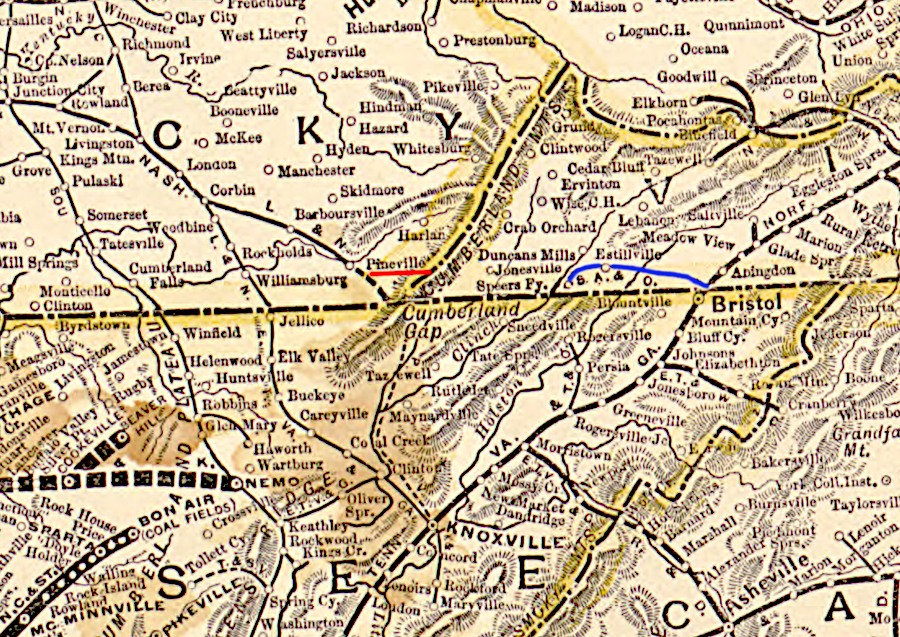

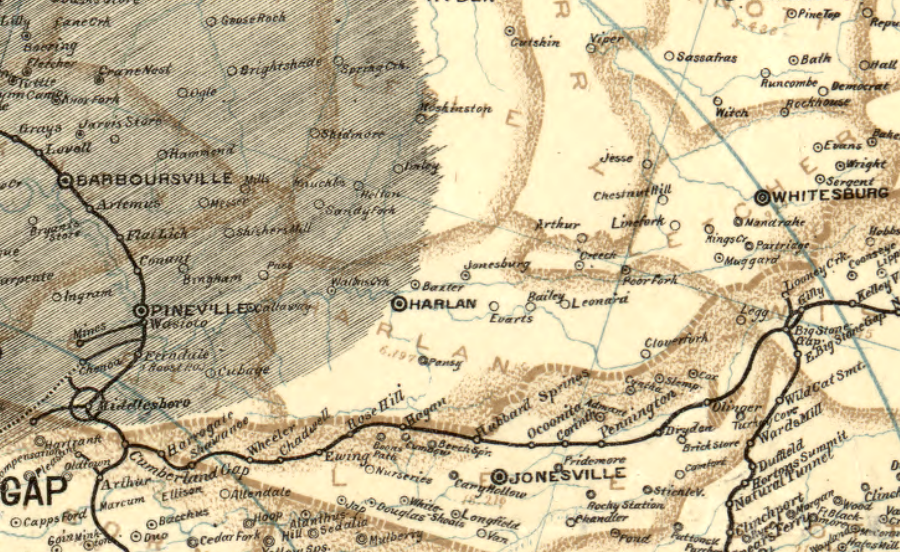

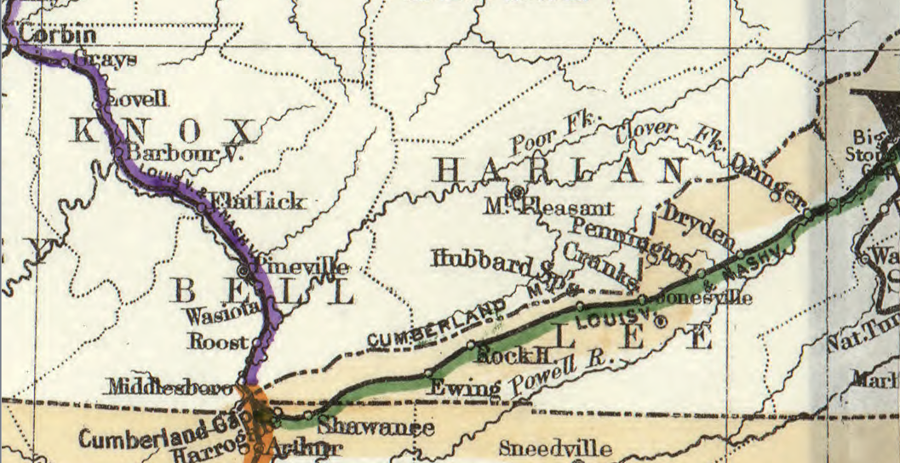

prior to the Civil War, the closest rail line near Cumberland Gap was 80 miles to the east

Source: Library of Congress, Railroad map of the eastern, western and northern states, and Canada (1859)

prior to the Civil War, the closest rail line near Cumberland Gap was 80 miles to the east

Source: Library of Congress, Railroad map of the eastern, western and northern states, and Canada (1859)

Coal was mined in Eastern Kentucky and transported by water to customers in the Ohio River Valley starting in the 1820's. Rivers were too shallow to deliver coal from the headwaters of the Cumberland River, so coal mined in the region near the Cumberland Gap was used just locally until the 1880's.1

The solution to increasing the value of the coal was to get it to market via railroads rather than rivers. Prior to the Civil War, business leaders in Knoxville succeeded in constructing connections to the network of railroads that reached east to ports on the Atlantic Ocean and north to New York City.

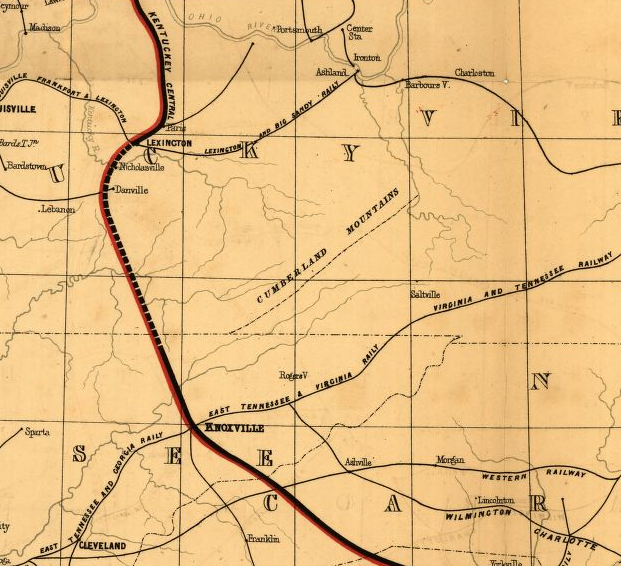

In 1836, railroad planners adopted a route to link Charleston, South Carolina with the Ohio River. That route went west of Cumberland Gap; it crossed the Tennessee-Kentucky border at modern-day Jellico, on the path now used by I-75.

the first rail line proposed in 1836 to connect Charleston to Cincinnati bypassed Cumberland Gap, and followed the route later used by I-75 across the Tennessee-Kentucky border

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Atlantic and Great Western Railway, with its connections (1866)

The South Carolina legislature chartered the Louisville, Cincinnati, and Charleston Railroad, but it failed in 1840 after the recession of 1837. The next attempt, the Blue Ridge Railroad, failed to get track constructed north of the South Carolina border.

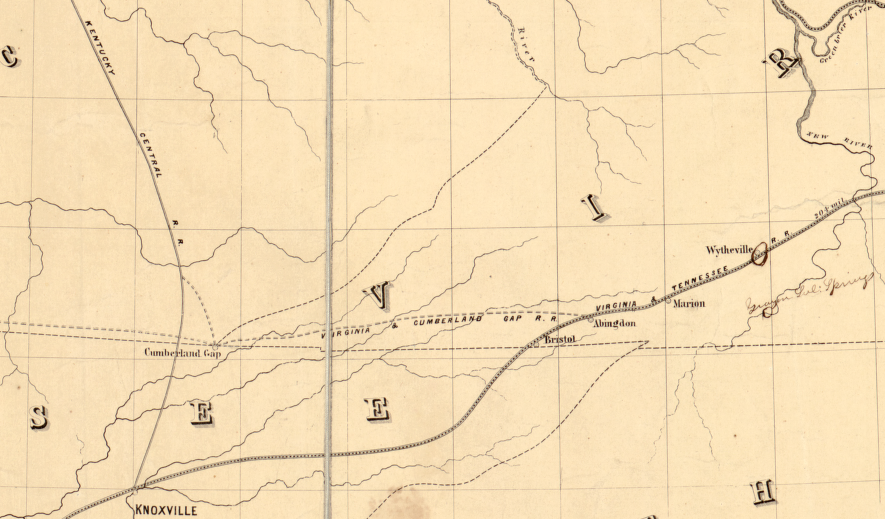

In the early 1850's, the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Lexington Railroad received a Tennessee charter. The Cincinnati, Cumberland Gap, and Charleston Railroad advanced beyond getting a charter and actually prepared a graded bed between Morristown and the French Broad River, but construction was interrupted by the Civil War.

Virginia chartered the separate Virginia and Kentucky Railroad to run from Bristol through Cumberland Gap into Kentucky. However, no railroad came near Cumberland Gap prior to the Civil War.2

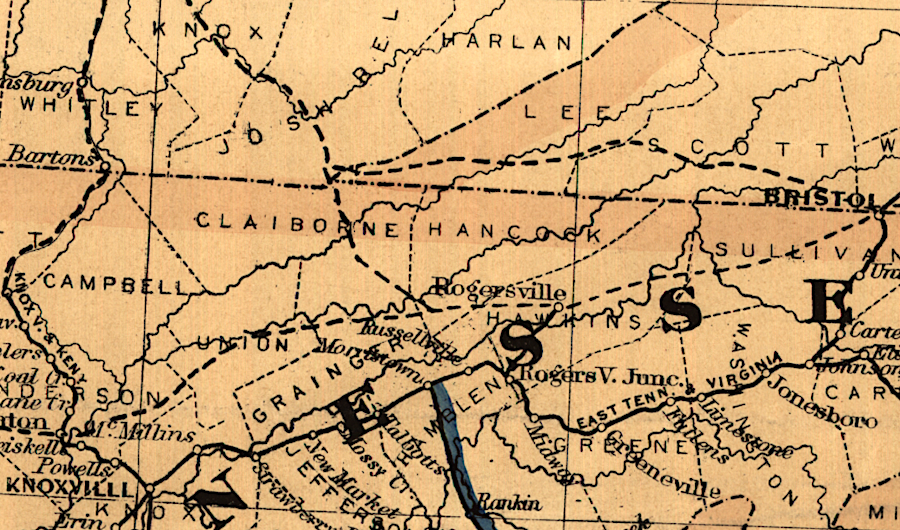

prior to the Civil War, multiple railroads were proposed to Cumberland Gap but none were built

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing route of Norfolk & Petersburg Rail Road and its connections with Ohio & Mississippi Rivers (1858)

After the Civil War, there were competing proposals for where to locate a railroad to transport coal from Southwest Virginia and Eastern Kentucky to markets in Atlanta, Norfolk, and on the Ohio River. A geologist proposed in 1872 to link the coal fields of Kentucky with the iron-ore region of Virginia, via a railroad built through the Guest River gorge in the Appalachian Plateau.

in 1873 the existence of coal on the Appalachian Plateau of Virginia was no secret, but no railroads permitted cost-effective transport to market

Source: Library of Congress, Maps showing the connections of the Northern and Southern West Virginia Railroad (1873)

in 1874, there were multiple proposals for railroads near Cumberland Gap

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Seaboard & Raleigh Railroad and its connections (1874)

In 1883, the Norfolk and Western (N&W) Railroad began to haul large quantities of coal from the Virginia coal fields in Tazewell County over 300 miles to Hampton Roads. To access the rich coal seams, the N&W built a rail line down the New River from Central Depot (Radford) to Pocahontas, requiring nearly 50 miles of track.

in 1882, the Norfolk and Western (N&W) railroad was building up the New River into the Pocahontas coal fields, not northwest from Bristol into Wise County

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia Air Line Railroad (1882)

At Bristol, the N&W was roughly 20 miles from the Wise County coal fields. A connection from Bristol would have to cross the watershed divides separating the Holson, Clinch, and Powell rivers, but a natural tunnel on Stock Creek already provided a way to get from the Clinch River to the Powell River. The N&W prioritized the coal at Pocahontas, because it was almost 100 miles closer to Norfolk than the Wise County coal fields.3

In the 1880's, American promoters and British investors led by the bank of Baring Brothers projected that iron-rich lands in Kentucky near Cumberland Gap could grow into an steel production center comparable to Pittsburgh. Speculation stimulated rapid development of Middlesboro, Kentucky, which was named after Middlesborough, England where many investors were located. Key to development of Middlesboro was a railroad to transport iron ore, coal/coke, limestone, and iron/steel products.

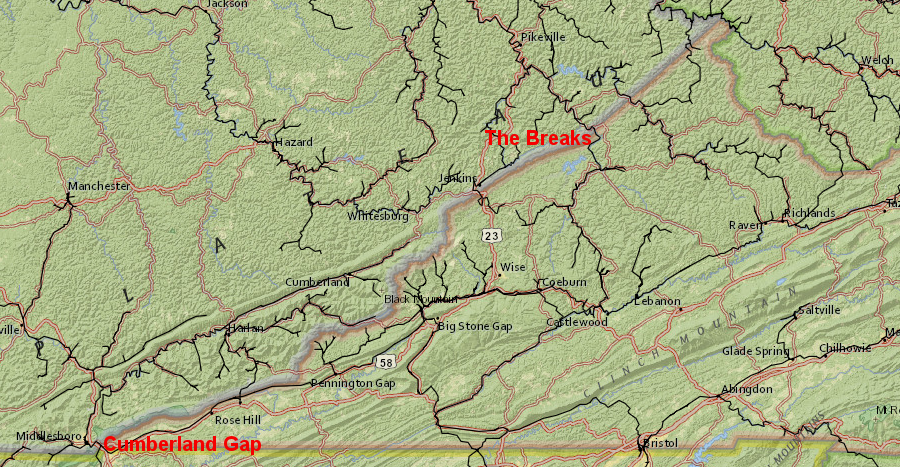

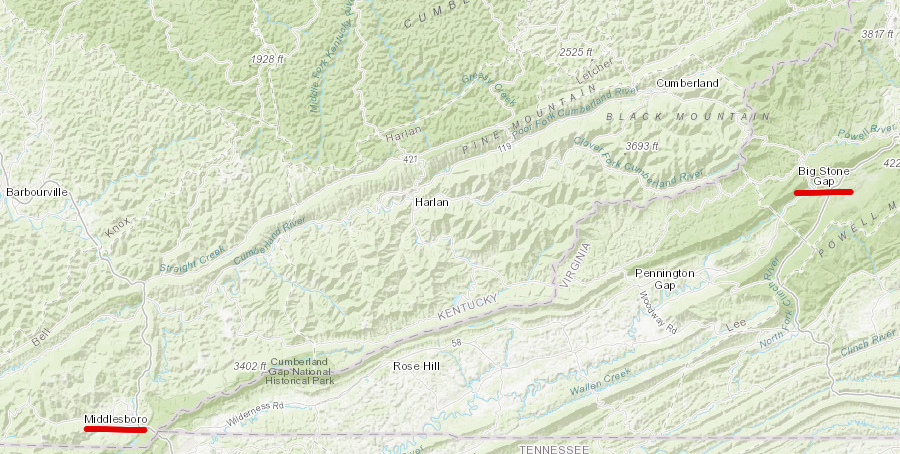

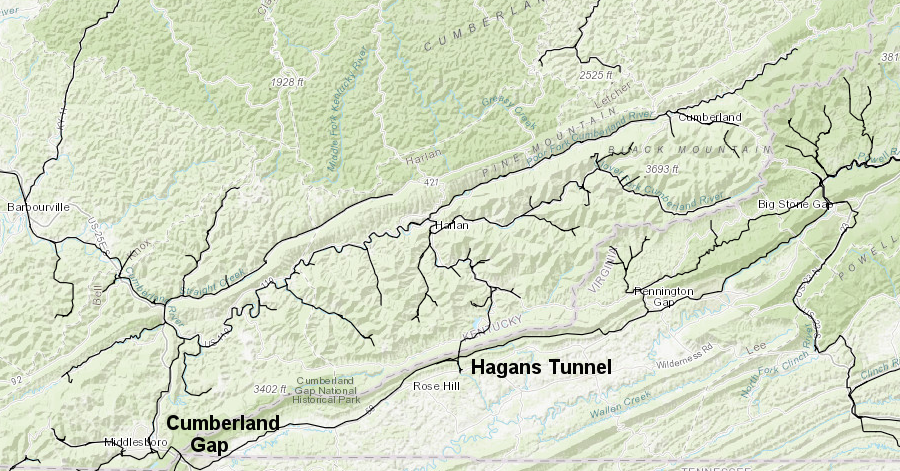

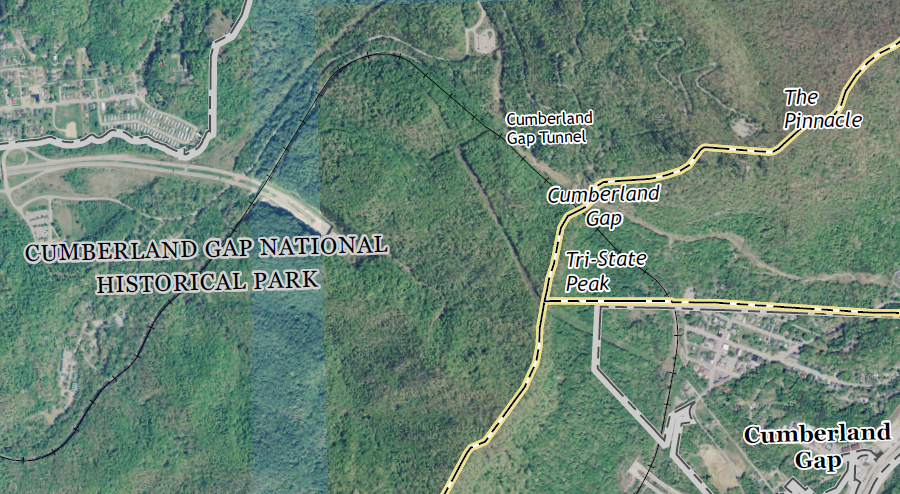

Cumberland Mountain was a barrier to railroads, from Cumberland Gap to the Russel Fork River at the Breaks

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1886, Tennessee investors organized the Powell's Valley Railway, with plans to build north from Knoxville to Cumberland Gap. In 1890, the renamed Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad excavated a tunnel underneath the gap to Middlesboro. Because the tunnel was at the intersection of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia, the railroad obtained charters from all three states authorizing construction.4

The tunnel's grade peaked slightly in the middle. Trains went uphill into the tunnel from either direction, then started downhill from the middle. The smoke from the locomotives lingered at the peak.

After five years of use, the tunnel collapsed on July 4, 1894. It was repaired, but there was a second collapse in 1896. For some time, passengers got off at the Middlesboro (Kentucky) or Cumberland Gap (Tennessee) tunnel entrances and rode a wagon or walked across the gap. Engineers moved their locomotives to the back end of the train and pushed the cars through the tunnel, far enough for another locomotive on the other end to attach and pull the train through.

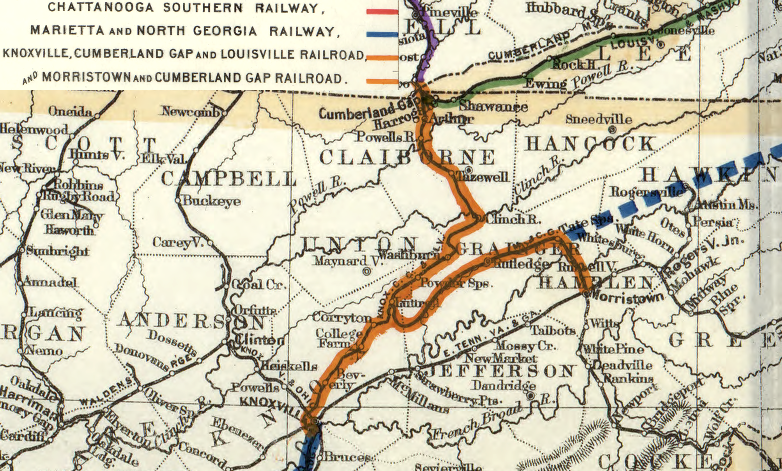

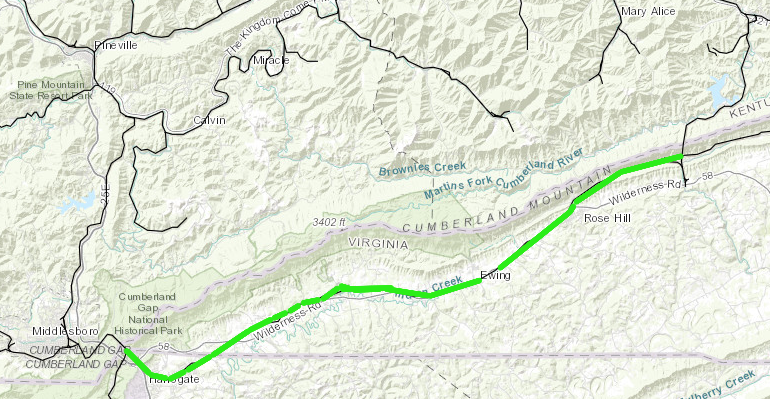

The Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad took cargo south from Middlesboro via Cumberland Gap to Knoxville.

the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap and Louisville Railroad linked Middlesboro to points south

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the proposed Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia Railroad (1892)

In 1888, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad built a 25-mile extension south from Corbin, Kentucky to Pineville, Kentucky in 1888. In 1889, that track was extended another 10 miles to reach Middlesboro. Initially the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad only took cargo north from Middlesboro; it did not have rights to use the Cumberland Gap tunnel.

the Louisville and Nashville Railroad reached Pineville in 1888, as the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad (blue) was crossing the Clinch River

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Ry.; and connections. (by W. L. Danley, 1889)

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad was hopeful that Middlesboro might grow into another major steel center generating profitable traffic like Birmingham, Alabama, but also desired to extend its tracks into Wise County, Virginia. The railroad calculated it could earn reliable profits from hauling coal and coke to customers on the Ohio River, even though Wise County was 50 miles to the northeast and on the other side of Cumberland Mountain from Middlesboro.

The Virginia coal had high value for making "coke," a fuel and carbon source for manufacturing steel. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad projected that steel mills in the Ohio River would pay for Virginia coke and iron ore. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad just needed a rail connection between Middlesboro and the Virginia coal fields.5

the Louisville and Nashville Railroad built track to Middlesboro in 1889, as part of a plan to reach coal fields near Big Stone Gap in Wise County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

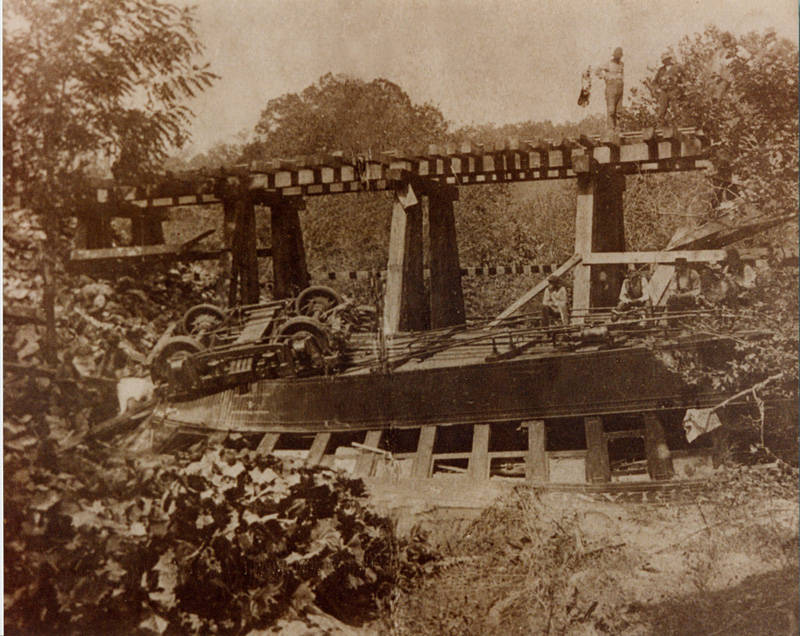

The solution was to acquire the Cumberland Gap tunnel from the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad. That railroad had financial struggles, including an inauspicious start when a train taking key investors from Knoxville to the tunnel wrecked and killed several people. Funding from the English bank was constrained due to a financial recession in 1890. The 1893 economic recession ("panic") in the United States was followed by the 1894 tunnel collapse. The Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad defaulted on its bonds and was broken up into two parts in 1895.

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad purchased both the Cumberland Gap tunnel and some track extending to a spot 1,074 feet south of the tunnel's entrance. The Southern Railroad acquired the rest of the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad track south to Knoxville, plus trackage rights to run trains through the tunnel into Middlesboro.6

a train wreck that killed prominent Knoxville residents going to see the new industrial city of Middlesboro led to the sale of the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap and Louisville Railroad

Source: Lincoln Memorial University, Train wreck of the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap and Louisville Railroad in 1889

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad reinforced the railroad tunnel beneath Cumberland Gap after the 1896 collapse. Much, but not all of the narrow tunnel is still lined with that brick and cement today.7

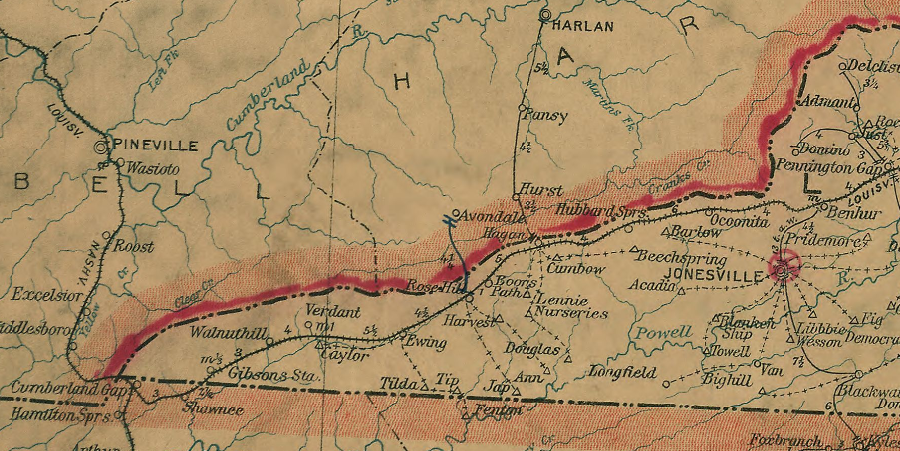

After acquiring the Cumberland Gap tunnel, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad built a new railroad line from its southern tip (south of the tunnel) through Lee and Wise counties. The railroad's engineers chose to follow the valley of the Powell River rather than the Clinch River further east. The route through Lee County bypassed the small town of Jonesville, reflecting the railroad's intent to make its profits by carry coke and coal rather than general freight or passengers.

the Louisville and Nashville Railroad bypassed Jonesville, choosing a faster route for coal/coke hauling rather than more freight/passenger traffic

Source: Library of Congress, Post route map of the states of Virginia and West Virginia (Postmaster General, 1906)

When the Louisville and Nashville Railroad reached Intermont, it renamed the town "Appalachia." When it reached Prince's Flats, it renamed the town "Norton" after the railroad's former president, Eckstein Norton.8

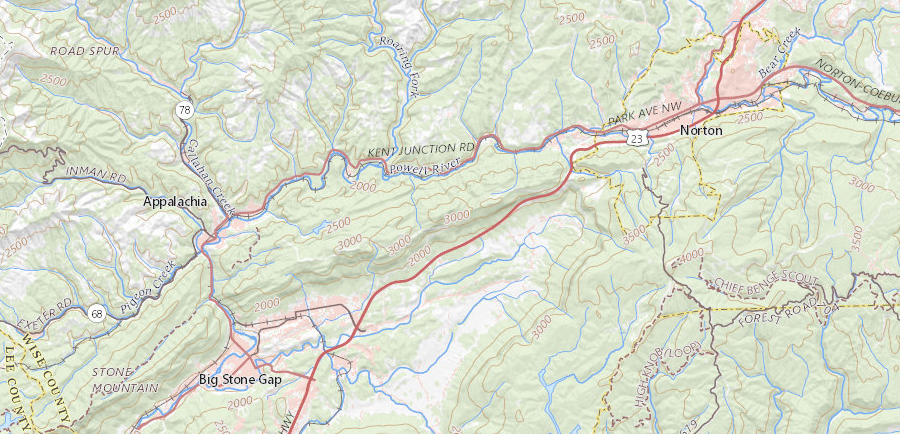

the Louisville and Nashville competed with the South Atlantic and Ohio plus the Norfolk and Western Railroad for access to Wise County coal

Source: Library of Congress, South western Virginia and environs (Big Stone Gap Improvement Co., 1892?)

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad had not planned to use Cumberland Gap and its unreliable tunnel. The railroad initially had planned to build track northeast from Pineville, Kentucky, going up the Cumberland River. The track would have crossed Black Mountain/Cumberland Mountain to Big Stone Gap.

The final decision was to build from Pineville southeast to Middleboro, acquire the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad, and refurbish the Cumberland Gap railroad tunnel. That route reflected the geography of the L&N's primary markets.

Unlike the Norfolk and Western Railroad, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad could transport coal south to Atlanta. The Cumberland Gap route provided a shorter trip to southern customers than the initial plan to build a new line from Pineville up the Cumberland River. The loop from Wise County south through Cumberland Gap added distance for shipping coke north to the Ohio River steel mills, but made it less expensive to ship coke to Atlanta and Birmingham.

The Norfolk and Western Railroad decided to compete with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, coming from the other direction to service mines expected to open in Dickenson and Wise counties. To access the region, in 1891 the Norfolk and Western Railroad built new track southwestward from Bluefield to Norton. It cut tunnels through the Appalachian ridges so heavy coal trains would not be slowed down by steep grades.

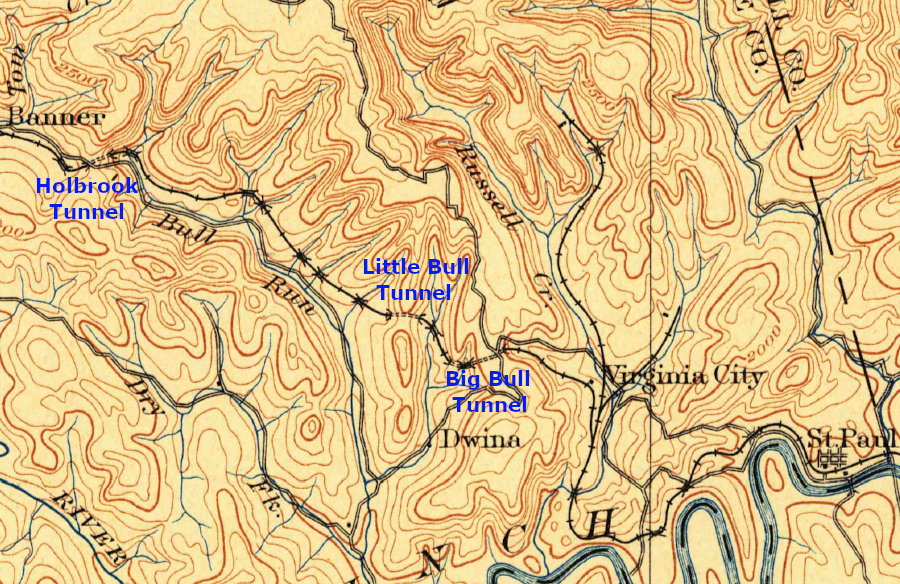

west of St. Paul, the Norfolk and Western Railway carved multiple tunnels in Wise County to cross the Clinch River/Guest River watershed divide

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Bristol VA 1:125,000 topographic quadrangle (1902)

The largest owner of coal in the area, which became known as the Virginia Coal and Iron Company, tried to get the Norfolk and Western Railroad to build the first line to Big Stone Gap. The Virginia Coal and Iron Company had acquired the rights of the Bristol Coal and Iron Narrow Gauge Railroad, which had been unable to complete construction from Bristol to Cumberland Gap despite the use of convict labor. The Virginia Coal and Iron Company changed the railroad's name to the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad.9

The Virginia Coal and Iron Company investors failed to convince the Norfolk and Western Railroad to invest in building a new railroad from Bristol to Big Stone Gap. Instead, the Norfolk and Western Railroad built new track along the New River to the Pocahontas coal fields, which were closer to Norfolk. That forced the Virginia Coal and Iron Company investors to use their own funds to build what they called the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad.

The South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad linked Bristol to the new town of Appalachia between 1888-90. As a result, Wise County ended up with three rail lines - the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, the Norfolk and Western Railroad, and the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad - within a two year period.

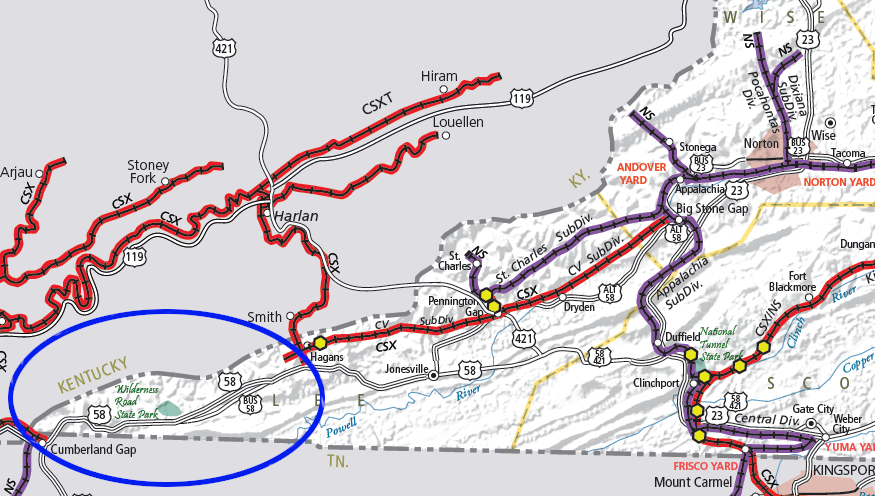

Wise County became coal country in 1890-91 after three railroads built lines to Big Stone Gap, Appalachia, and Norton

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Louisville and Nashville and the Norfolk and Western railroads shipped coal and coke to northern and eastern customers. The South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad connection to Bristol made it cost-effective to ship Virginia coal and coke south to South Carolina ports.

The southern outlet increased competition in the Wise County coal fields. The railroads shipping to northern and eastern markets had alternative supplies from other coal fields. They could afford to set rates high, generating good profits even if that limited the volume of coal produced near Big Stone Gap.

The South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad and its partner the Southern Railroad were "coal poor." They relied upon Wise County mines to supply southern customers, so they set rates low enough to incentivize mine owners to produce high volumes of coal and coke.

One coal executive commented regarding the value of coal resources in Wise County during the 1890's:10

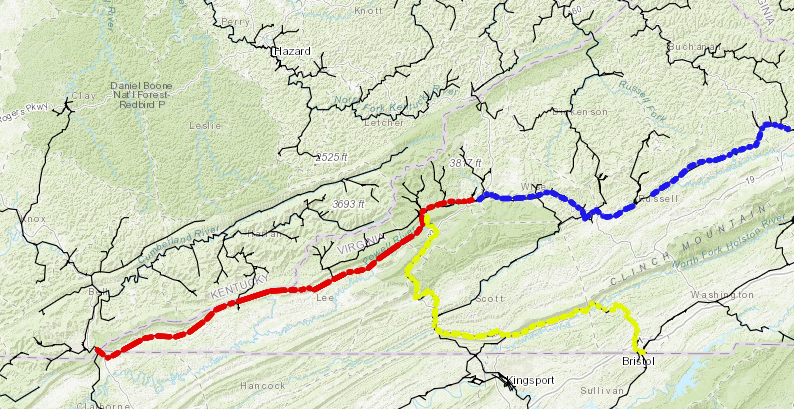

the Louisville and Nashville (red), South Atlantic and Ohio (yellow) and Norfolk and Western Railroad (blue) built the first rail lines into Wise County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad was underfunded and unable to extend its tracks past the town of Appalachia. The Louisville and Nashville ended up as the dominant railroad, so mine owners sought another way to create competition.

Starting in 1895, the Virginia Coal and Iron Company built a second line west of Big Stone Gap. That track, known as the Interstate Railroad, hauled coal from mines within the Appalachian Plateau. Trips were short, just to places such as Norton where loaded cars were transferred or "interchanged" with long-distance railroads that offered rates better than the Louisville and Nashville.

In 1899, the South Atlantic and Ohio Railroad was renamed the Virginia and Southwestern Railway after a corporate reorganization. It advertised itself as the "Natural Tunnel Route," since the track in Scott County passed through Natural Tunnel on Stock Creek.

The Southern Railroad acquired the Virginia and Southwestern Railway in 1906. Today the current owner of the track, the Norfolk Southern, still runs coal trains through Natural Tunnel to service customers in the southeast.11

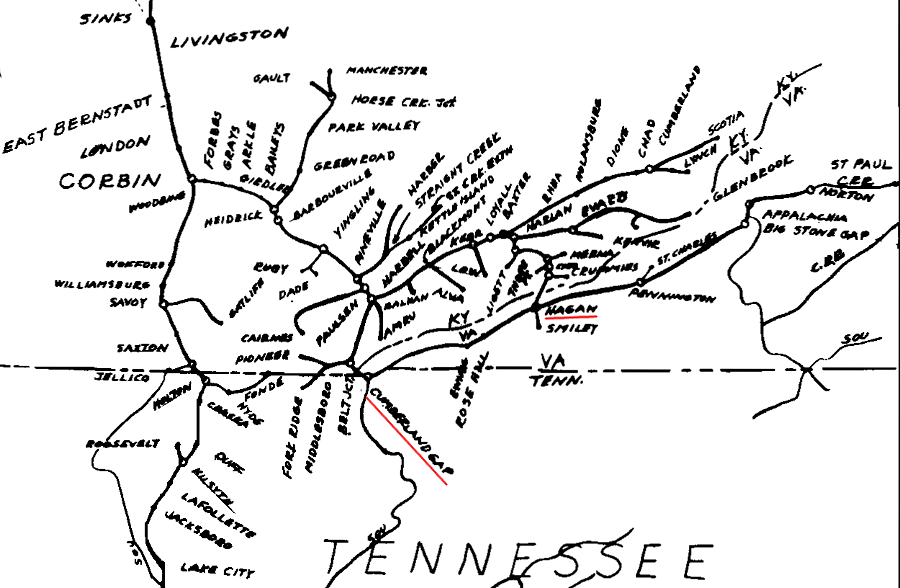

the Louisville and Nashville Railroad first built through Cumberland Gap to the Virginia coalfields, and reached Harlan 15 years later

Source: Library of Congress, Boones map of the Black Diamond System of Railways (1896)

A fourth railroad entered Wise County in 1909, when the Carolina, Clinchfield, and Ohio Railway connected Dante in Russell County to Spartanburg, South Carolina. It completed more track, going north through The Breaks to Elkhorn City, in 1915. The Clinchfield line added the last major railroad competition for hauling Wise County coal to market, and enhanced access to customers to the south.

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad waited until 1911 before finally building track up the Cumberland River to Harlan. The railroad built that line to access the coal in Eastern Kentucky, but it provided an option for getting to the coal across Cumberland Mountain in Wise County.12

the Louisville & Nashville (L&N) Railroad chose to build south from Pineville to Middlesboro, and waited 15 more years before building northeast along the Cumberland River

Source: Library of Congress, Map showing the proposed Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia Railroad (1892)

In 1930, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad built the 6,244-foot Hagans Tunnel through Cumberland Mountain. The railroad finally shifted its link to the Virginia coal fields away from the Cumberland Gap tunnel. The Hagans Tunnel offered a more-direct connection to the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railroad in Virginia at Smiley, Virginia.

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad built a temporary switchback connection on the Virginia side of the Hagans tunnel, but the Great Depression prevented investing in a more-efficient link between the railroads. The CSX Railroad has absorbed both the Louisville and Nashville and the Clinchfield railroads, but never upgraded the interchange at Hagans Tunnel. Trains loaded with Kentucky coal that pass through the tunnel still spend an extra 30 minutes navigating a switchback to get onto the mainline.

starting in 1930, Hagans Tunnel provided a more-direct connection than the Cumberland Gap tunnel for the L&N to ship Virginia coal to the Ohio River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1987, the CSX railroad (which had absorbed the Louisville and Nashville) abandoned the track between the Cumberland Gap tunnel and Smiley, and relied completely upon the Hagans Tunnel.13

the track from Cumberland Gap to Hagans Tunnel was abandoned in 1987

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

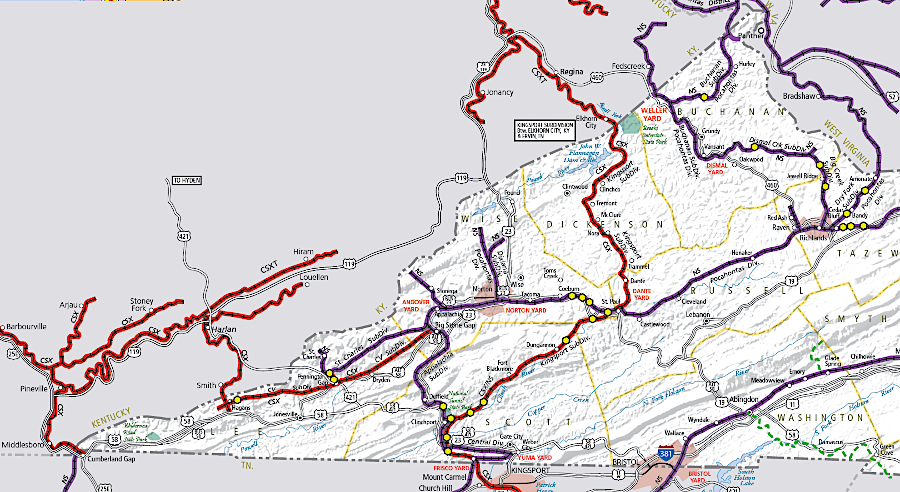

much of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad track from Cumberland Gap towards Norton was abandoned in 1987

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transit (DRPT), Virginia Rail Map (2019)

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad cut a tunnel through Pine Mountain in 1947, linking its line on the Big Sandy River in Kentucky to coal near Pound, Virginia. The tunnel was expensive to construct and maintain, since rock formations were not as stable as initially presumed. The Pine Mountain Tunnel was closed in 1958.

Since 2015, people in Pound (Virginia) and Jenkins (Kentucky) have been looking for funding and permissions from property owners to reopen the tunnel, build a trail, and attract tourists interested in walking across the Virginia-Kentucky state line underneath Pine Mountain. In 2014, Wise County Tourism Director Mike Wampler noted the draw of a railroad tunnel through a mountain connecting two states:14

the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad used the Pine Mountain Tunnel between 1947-1958, closing it when maintenance costs exceeded benefits

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

today, just CSX and Norfolk Southern serve the southwestern corner of Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transit (DRPT), Virginia Rail Map (2019)

the Louisville and Nashville Railroad carried coke and coal from Southwest Virginia coal fields through tunnels at Cumberland Gap and then Hagans to customers on the Ohio River

Source: Louisville & Nashville Railroad Historical Society, Corbin Division Timetable #1 (1976)

looking towards the south portal of the railroad through Cumberland Gap

Source: Lincoln Memorial University, View of Cumberland Gap and the railroad line

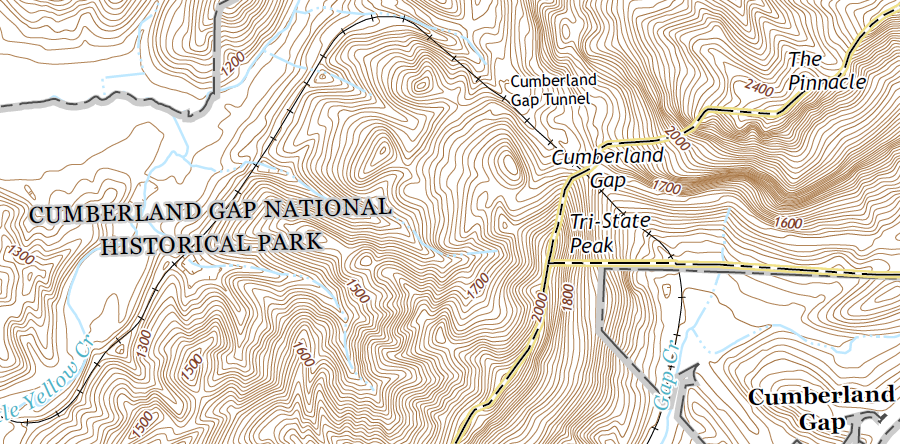

the rail tunnel beneath Cumberland Gap is now part of the Norfolk Southern railroad

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), 7.5-minute topographic map for Middlesboro South, KY-TN-VA (2016)