underground coal mines created the largest number of transportation tunnels in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Entrance to a W. Va. coal mine: a "drift" mine (1908)

underground coal mines created the largest number of transportation tunnels in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, Entrance to a W. Va. coal mine: a "drift" mine (1908)

In the Appalachian Plateau physiographic province, all the underground coal mines constructed tunnels with rail lines to transport miners, equipment, and of course coal. Tourists can walk through the Pocahontas Exhibition Mine today, to get a sense of the experience of traveling underground to the mine face.

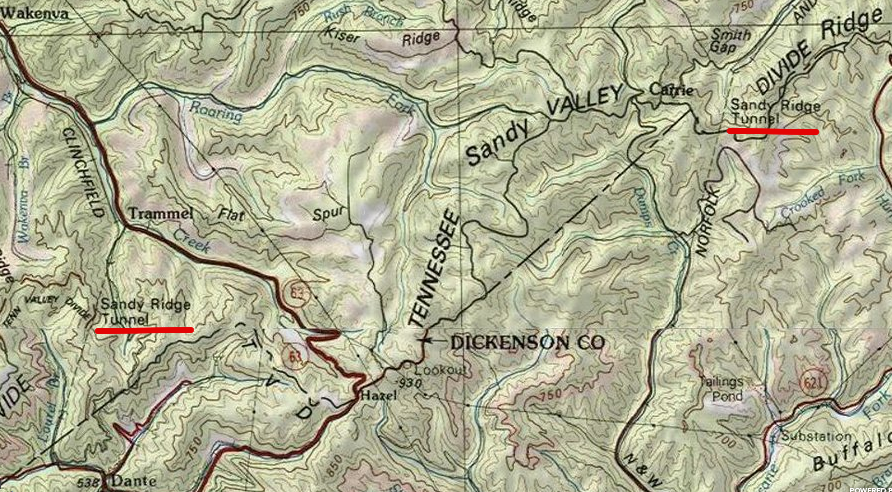

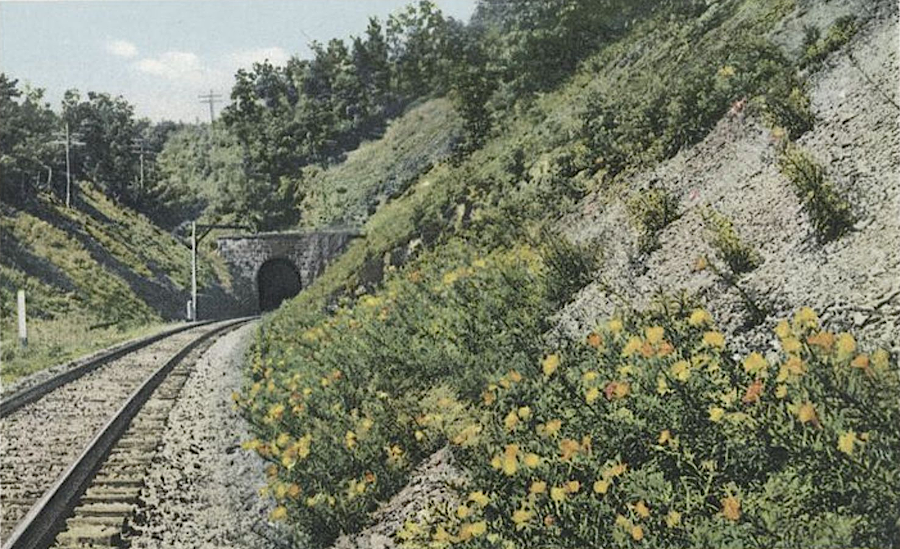

Railroads have carved a number of tunnels on the Appalachian Plateau for coal-hauling trains, in order to maintain a track grade that is as flat as possible. There are, for example, three railroad tunnels between St. Paul and Coeburn and three more on the line built by the Norfolk and Western between Bluefield and Norton. The Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway blasted multiple tunnels through Dickenson County when it extended its track from Dante to Elkhorn City in 1915.

By that time, steam-powered hammers and dynamite had replaced muscle power and black powder. John Henry was the "Steel Driving Man" who legend says worked at the Big Bend Tunnel along the Greenbrier River in West Virginia, carved out in 1870-73 on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railroad. By the time the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway cut 55 tunnels through the ridges between Elkhorn City, KY and Spartanburg, SC rather than build around the mountains, steel-driving men had been replaced by machines.1

the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway carved numerous tunnels in order to create a flat grade between Clinchco-Haysi along the McClure River

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Haysi 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (1963)

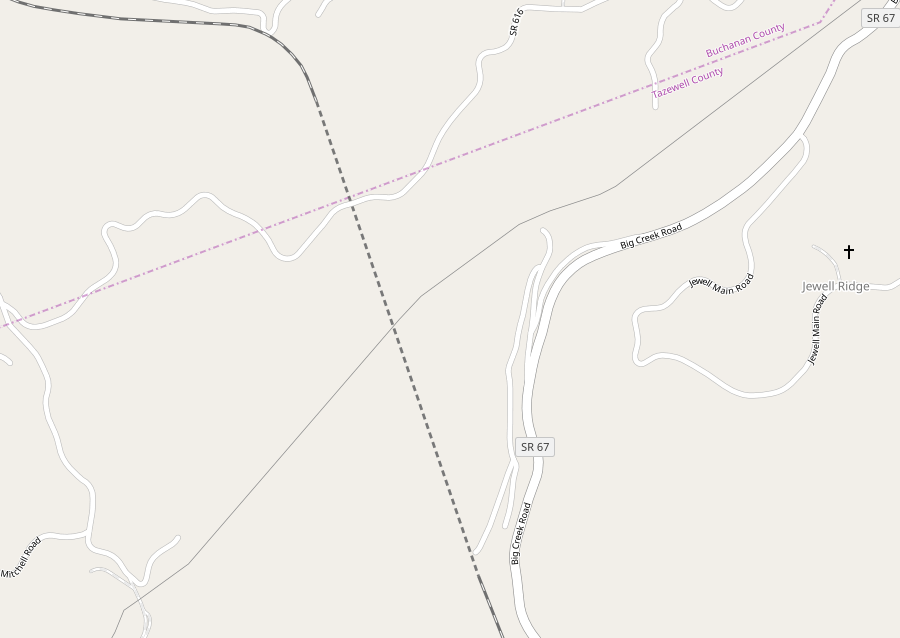

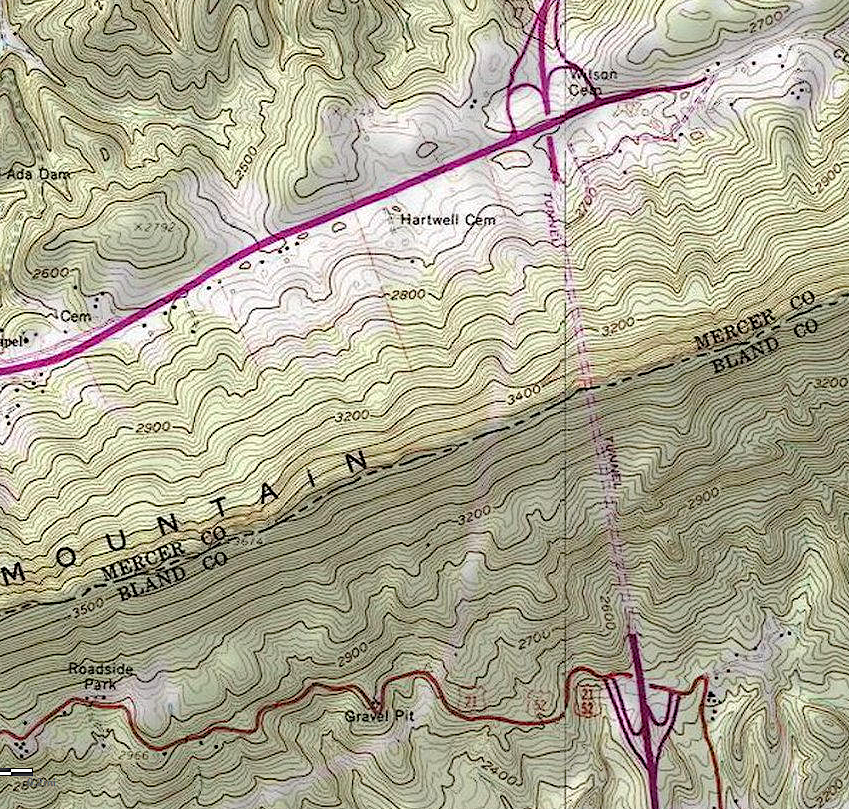

the Norfolk Southern tunnel passes beneath Smith Ridge, the Eastern Continental Divide, at boundary of Tazewell and Buchanan counties

Sources: ESRI, ArcGIS Online and Virginia Railroad Map

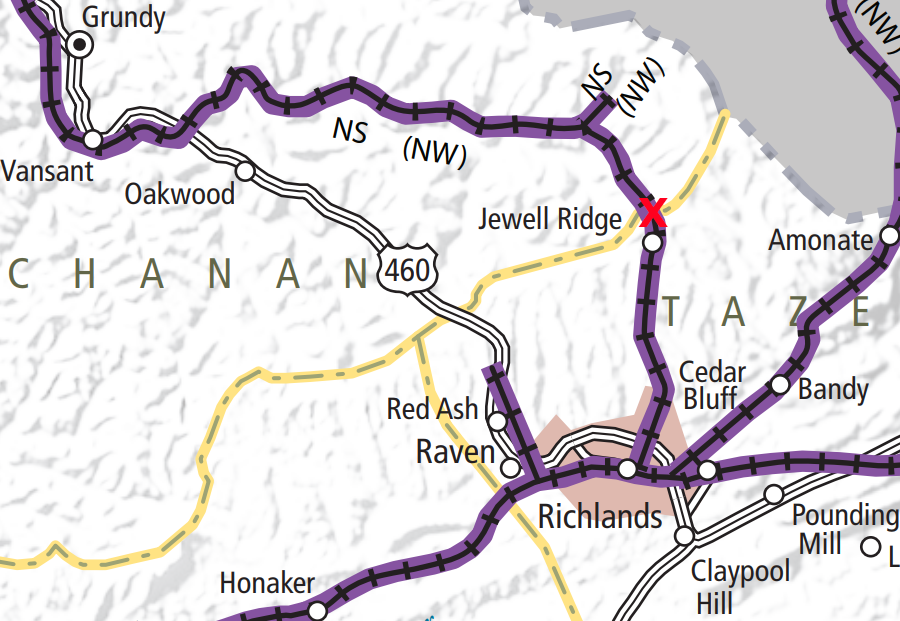

The shortest railroad tunnel in Virginia is the Bee Rock Tunnel on the Middle Fork of the Powell River in Wise County. The Louisville & Nashville Railroad cut it (and nearby Callahan's Nose tunnel) into the mountainside in 1891, when it built track between the towns of Big Stone Gap and Appalachia.

Ripley's Believe It Or Not briefly identified the 48-foot long Bee Rock Tunnel as the shortest railroad tunnel in the United States. However, in 1902 the Beaver Dam Railroad cut a 22-foot long tunnel through the Backbone Rock spur of Holston Mountain in Tennessee. The 20-foot Backbone Rock Tunnel was needed to connect to the Virginia-Carolina Railroad, which became known as the "Virginia Creeper."

Trains stopped using the track through Bee Rock Tunnel in the mid-1980's. It is now used by the Stone Mountain Trail, with the tunnel on a part known locally as the Roaring Branch Trail.2

in 2018, Virginia tourism officials still highlighted the short length of the Bee Rock Tunnel

Source: Virginia Tourism Corporation, Coal Heritage Trail

the Bee Rock Tunnel, south of Appalachia on the Powell River, was the shortest railroad tunnel in Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Three railroad tunnels in southwestern Virginia cross the boundary between the Appalachian Plateau and the Valley and Ridge physiographic provinces.

The first railroad tunnel was built through Cumberland Gap by the Knoxville, Cumberland Gap & Louisville Railroad in 1890. The initial Cumberland Gap railroad tunnel collapsed in 1894. The Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad purchased it, repaired the tunnel again after another collapse in 1896, and used it to haul coke and coal from the Wise County fields to steel mills in the Ohio River valley.3

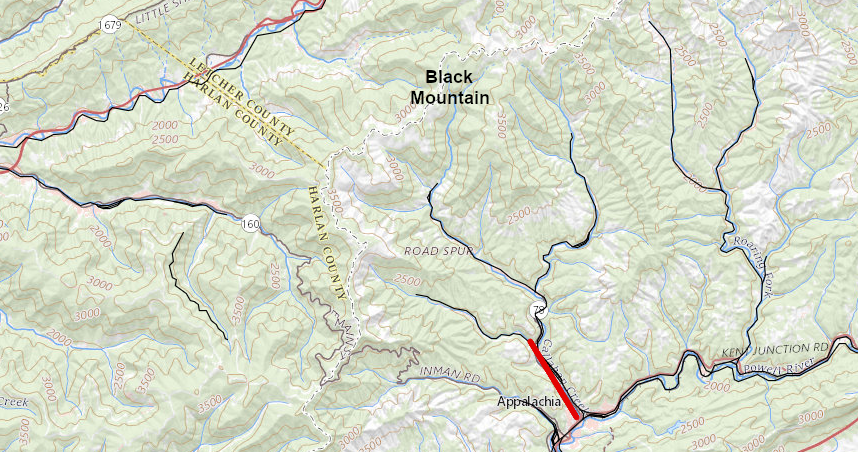

As part of the speculative expansion of the rail network in the region, another tunnel between Virginia and Kentucky was proposed in the 1890's. The Interstate Tunnel would have used the valley of Callahan Creek to go north from Appalachia through Black Mountain, to connect to rail lines in Letcher County. Most of the required funding was raised and a route with a tunnel was surveyed, but construction never started.4

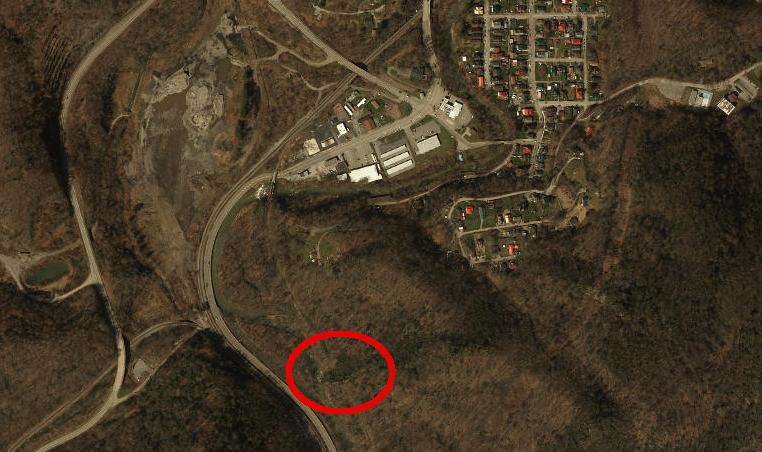

railroads were built up Callahan Creek north of Appalachia, but no tunnel was blasted through Black Mountain into Kentucky

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

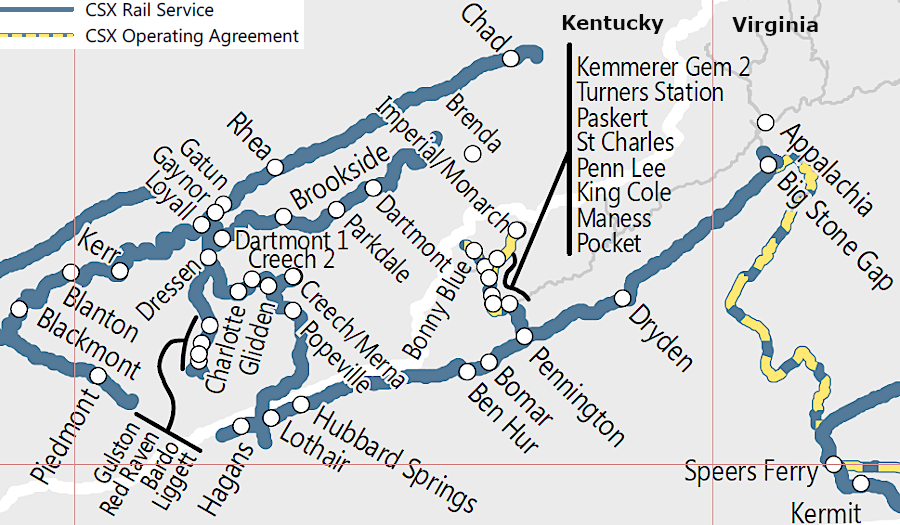

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad cut the Hagans Tunnel through Cumberland Mountain in 1930. That created a shorter route from the Wise County coal fields to the Ohio River and to ship Kentucky coal to eastern buyers. In 1958 the railroad abandoned the track between the Hagans Tunnel and Cumberland Gap, putting all traffic through the tunnel.

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad is now part of the CSX railroad. It still moves trains loaded with Kentucky coal through the tunnel to customers east of the Appalachian Plateau. In 1930 the Louisville and Nashville Railroad built a switchback to connect to the mainline on the Virginia side of the tunnel. Though trains had to spend an extra 30 minutes moving though the inefficient interchange, CSX has never found it economically justifiable to upgrade the interchange.

In 2003, during a legal dispute over railroad rates for hauling coal, Duke Power proposed replacing the Hagans Tunnel. The utility proposed a hypothetical Appalachia & Carolina Western Railroad, claiming a redesigned track layout could reduce costs by replacing the existing tunnel and eliminating the switchback. The Surface Transportation Board, a Federal agency, rejected Duke Power's claim and concluded:5

the Louisville and Nashville Railroad abandoned its track to Cumberland Gap in 1958, and CSX still relies upon the Hagans Tunnel to connect tracks serving Kentucky and Virginia coalfields

Source: CSX, CSX System Map

In 1947, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad cut a railroad tunnel through Pine Mountain on the Virginia-Kentucky border in order to get access to a new coal field near Pound. The line connecting Jenkins (Kentucky) and Pound (Virginia) was known as the Meade Subdivision. The railroad's main customer was the coal mine at Meade.

The mine expanded to where coal could be loaded on the Clinchfield Railroad, which had extended a connection and could hauul coal without passing through the tunnel into Kentucky. The coal loading facility on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad track closed in 1957. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad then closed the Pine Mountain tunnel in 1958, after just 11 years of use.

Pine Mountain was composed of sedimentary rock formation. The railroad regularly had to absorb high maintenance costs to clear rockfalls from the tunnel. After abandonment, local explorers would climb through the tunnel, and one reported in 2014:6

Local officials on either side of Pine Mountain are trying to get the Pine Mountain tunnel reopened as part of a trail that might attract tourists.7

the Clinchfield and the Norfolk and Western railroads both tunneled through Sandy Ridge separating the Clinch and McClure rivers, to cross the Eastern Continental Divide

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Cutting through mountains on the Appalachian Plateau allowed railroad route planners to minimize the challenge of going up and down when crossing ridges. The Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway crossed from Kentucky into Virginia at the State Line Tunnel through The Breaks.

However, steam engines burning coal filled those tunnels with steam, smoke and cinders.

In 1888, the Norfolk & Western Railroad and a local mining company built the 3,100-foot Coaldale (Elkhorn) Tunnel through Flat Top Mountain west of Bluefield in West Virginia, offsetting the cost in part by using the coal extracted from the tunnel bore. That tunnel allowed trains to cross its highest point. Even with the tunnel, trains loaded with coal had to climb over 1,000 feet in 22 miles.

Speed was reduced to 7.5 miles per hour in the tunnel, to reduce the smoke generated. The line was electrified in 1915 in order to eliminate the smoke and speed the transport of coal east to the piers at Norfolk. That electrification was used until diesel locomotives replaced coal-fired steam engines in 1959.

Men in the steam engines suffered as their trains passed through poorly-ventilated tunnels. An engineer described the difficulty of just breathing:8

the new Elkhorn Tunnel was ventilated between 1950-1959, until diesel locomotives eliminated the need

Source: The Last Churchill-Wentworth Tunnel Ventilator

In 1923, workers on the Virginian Railroad protested the unhealthy conditions of moving trains through tunnels on the line up through Clarks Gap, where the railroad crossed its highest elevation on the way to its wharves in Norfolk. The railroad then electrified the track from Mullens, West Virginia all the way to Roanoke.

That required building a power plant at Narrows on the New River, as well as a catenary line to carry the electricity for the electric "motors." Electrifying the line improved conditions for railway workers taking trains through the 5,176-foot Alleghany Tunnel near Blacksburg, where the Virginian crossed the watershed divide between the New and Roanoke rivers. It is one of two railroad tunnels called the Alleghany Tunnel, and neither one crosses the Allegheny Front.9

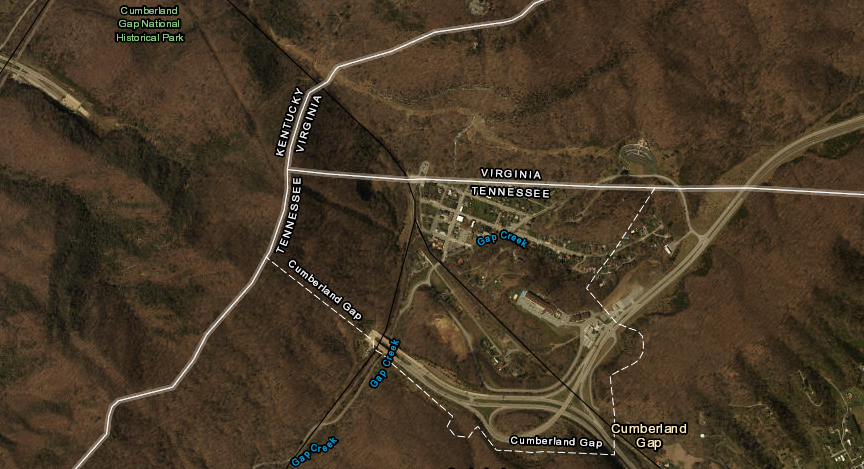

Cumberland Gap has a highway tunnel, in addition to a separate railroad tunnel. The railroad tunnel crosses beneath Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee, but the US 25 highway tunnel runs below just Kentucky and Tennessee. Cars driving through the Cumberland Gap Tunnel cross underneath just two states, since the tunnel was constructed west of the tip of Virginia.

In contrast to the railroad tunnels, there is no highway tunnel in Virginia with one portal in the Appalachian Plateau physiographic province and the other in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province.

The highway tunnel at Cumberland Gap opened in 1996. Moving US 25 underground allowed the National Park Service to remove the asphalt pavement and restore the appearance of the historic road trace on the surface through Cumberland Gap.10

the railroad tunnel under Cumberland Gap (black line) goes underneath three states, but the US 25 highway tunnel does not cross underneath Virginia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In the Valley and Ridge physiographic province of Virginia, there is one natural tunnel in Scott County, two natural bridges (too short to be called "tunnels") in Rockbridge County and Lee County, and multiple human-constructed tunnels for railroads.

Two highway tunnels carry I-77 through Bland County, the Big Walker Mountain Tunnel through Walker Mountain and the East River Mountain Tunnel through East River Mountain on the West Virginia border. Bland County has been described as "the only county in the United States that is entered and exited by Interstate Tunnels.

I-77 passes through Walker Mountain via Big Walker Mountain Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridges and Culverts

Bland County could add another claim, to be the "only county with an Interstate Highway tunnel cutting through a mountain on a state border." The qualifiers are essential to that claim.

The Holland Tunnel carries I-78 between New Jersey and New York, but goes below the Hudson River. The only other highway tunnel in the United States that cuts through a mountain to cross state lines is at Cumberland Gap. The highway passing through that tunnel is not part of the Interstate Highway system. That is also the case for the Lincoln Tunnel under the Hudson River, and for the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel that crosses the Michigan-Canada border.11

the East River Tunnel is the only interstate highway tunnel which cuts through a mountain while crossing a state line

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Material excavated from the mountain during construction of the East River Mountain Tunnel between 1969-1974 was used to build the embankment for the Laurel Creek bridge.

a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) reveals I-77 crossing Laurel Creek before entering the portal of the East River Tunnel on the Virginia side of the mountain

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map - DEM Viewer

Workers tunneling deep underground encountered springs in the limestone bedrock, and wore rubber coats and boots as if it was raining. Though most tunnel construction involves excavating rock, workers on the East River Mountain Tunnel ran into caves and had to bring in enough concrete to raise the bed of the tunnel by two feet in one spot.

two holes were bored through the mountain to create the four-lane East River Mountain Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, North entrance to the East River Mountain Tunnel on I-77

The East River Mountain Tunnel is over one mile in length, and exhaust fumes from vehicles could accumulate quickly. A dozen exhaust fans and another dozen fresh air fans can exchange all the air within the tunnel in two minutes.

The ventilation system was essential in 2016, when a tractor trailer burned in the tunnel and generated massive amounts of smoke. Tunnel managers anticipated a fire only every 20 years, but a second vehicle burned in the East River Mountain tunnel only six months later. A "lesson learned" during the earlier incident was applied, and the fans were used to direct smoke away from the firefighters.

when a tractor trailer burned inside the East River Mountain Tunnel in 2014, the traffic jam lasted for hours

Source: Firehouse, East River Mountain Tunnel Fire

The Big Walker Mountain Tunnel was constructed between 1967-1972. As in the East River Mountain Tunnel, a system of 24 fans with backup generators prevents a buildup of deadly carbon monoxide from exhaust. To date, not vehicles have caught fire in that tunnel.

inside Big Walker Mountain Tunnel (Bland County)

exiting Big Walker Mountain Tunnel on the way to Wytheville

Highway engineers who designed the route for I-77 chose to excavate a 300' deep roadcut through Little Walker Mountain, but built the to avoid a 500' deep roadcut through Big Walker Mountain. At its deepest point, the I-77 pavement is 800' below the top of the mountain.12

headed south on I-77 into Big Walker Mountain Tunnel (Bland County)

Multiple tunnels were cut through the ridges west of Staunton to maintain as level a grade as possible for railroads. The Richmond and Allegheny Railroad expanded the Mason Tunnel, which had been completed but not used by the James River and Kanawha Canal, and bypassed the Marshall Tunnel. It had been left incomplete when the canal stopped at Buchanan.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad completed carving tunnels through ridges in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province. Today the CSX Railroad operates through them.

Millboro and Lick Run tunnels were constructed just west of Millboro in Bath County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

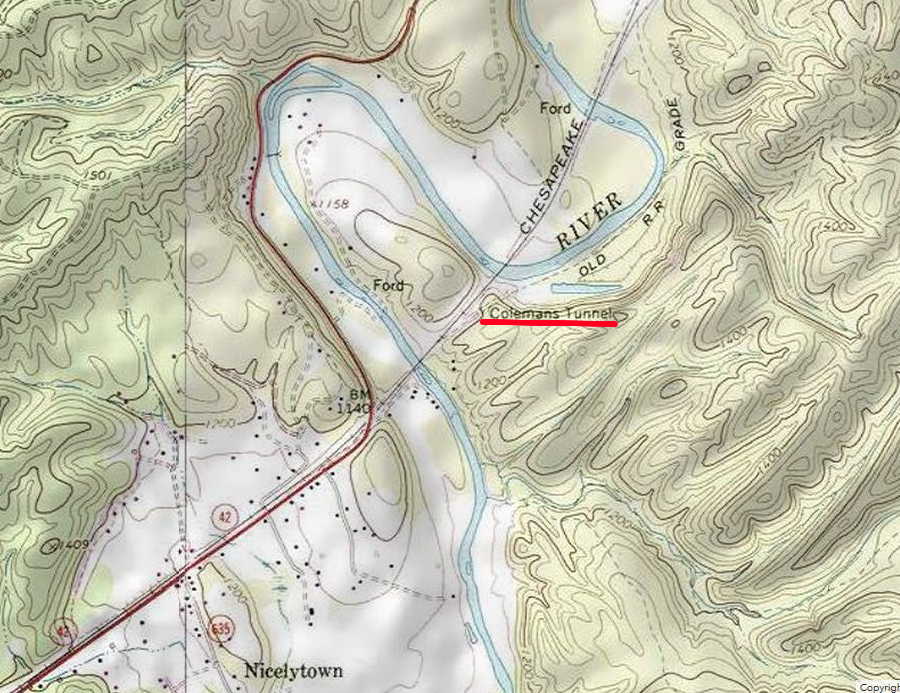

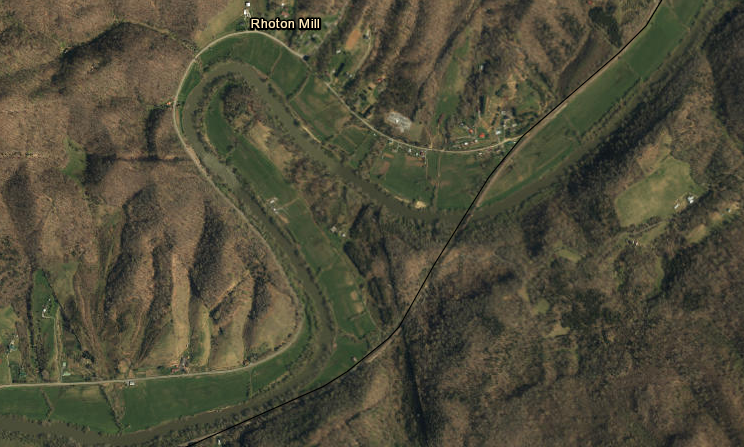

The Coleman Tunnel was cut through a ridge that formed a horseshoe in the Cowpasture River, east of Clifton Forge. That tunnel was eliminated later, when the railroad revised its route slightly.

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built Coleman Tunnel, east of Clifton Forge on the Cowpasture River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

re-routing the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad has eliminated the need for Coleman Tunnel

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Covington and Ohio Railroad was chartered to build across the Allegheny Front, from Covington to the Ohio River, but the Civil War intervened before any rails were laid. The Virginia Central Railroad and the Covington and Ohio Railroad merged into the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad after the war, and Collis P. Huntington was recruited to fund the extension west to the Ohio River. Within Virginia, that railroad built five and one-half tunnels.

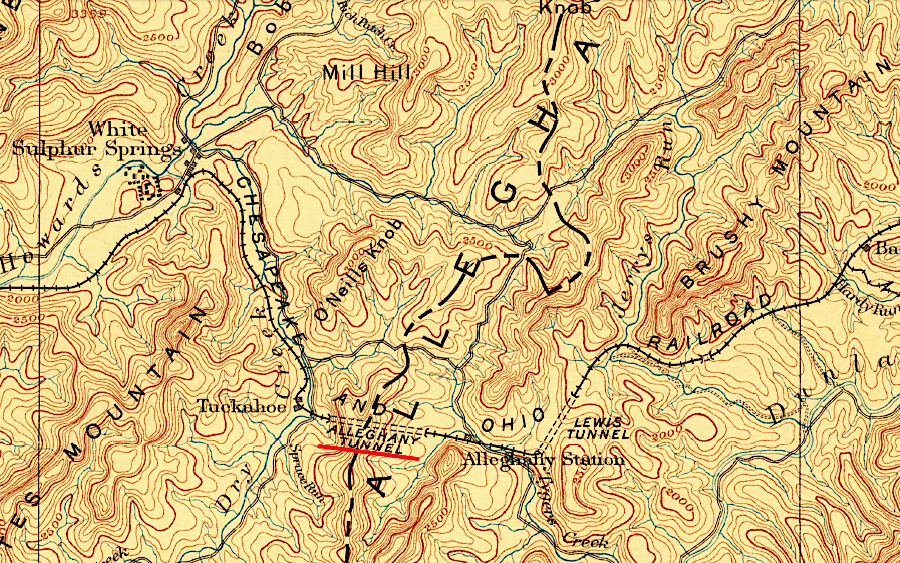

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad has its own Alleghany Tunnel, completed in 1870 at the Virginia-West Virginia border. A second tunnel was constructed parallel to it in 1932. The east portal of those tunnels is located within Virginia; the west portals are in West Virginia.13

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built its own Alleghany Tunnel on the Virginia-West Virginia border

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lewisburg, VA 1:25,000 topographic quadrangle (1887)

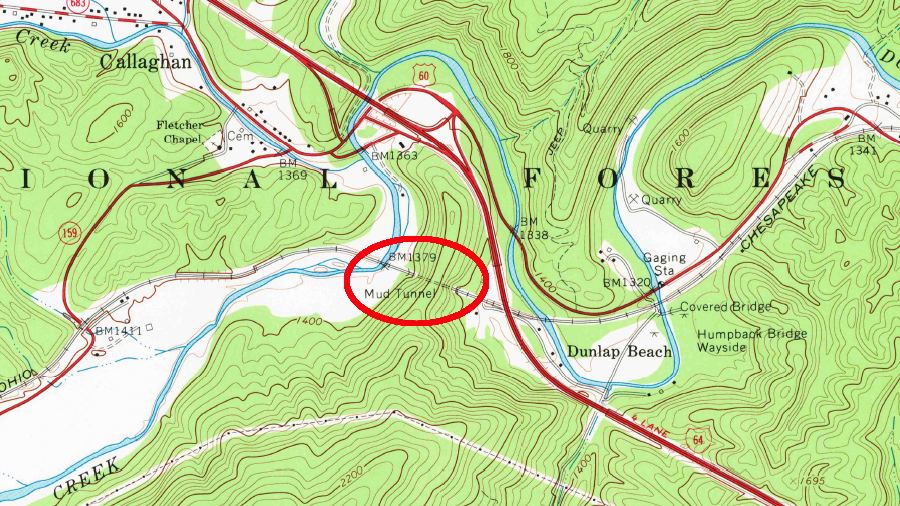

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built five other railroad tunnels between Covington and the Alleghany Tunnel. From east to west, they are the Mud, Moore, Lake, Kelly, and Lewis tunnels, then the eastern portal of the Alleghany Tunnel.

Mud Tunnel, the first railroad tunnel west of Covington, is at the northern tip of Peters Mountain

Source: US Geological Survey, Callaghan, VA 1:24,000 tpographic quadrangle (1966)

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built five tunnels west of Covington, plus the Alleghany Tunnel at the Virginia-West Virginia border

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Lewis Tunnel is the longest, at 3/4 mile in length. In 1989, steam locomotive 765 returned through Lewis tunnel, after hauling a chartered train from White Sulfur Springs resort to Covington. On the return trip, it pulled a string of boxcars to add weight and help control the speed going downhill west of Alleghany Tunnel.

So many cars were added that the train traveled through Lewis Tunnel far slower than planned. The exhaust from the steam cleaned the soot that had been deposited on the roof of the tunnel from over 30 years of diesel locomotives passing through. As hot exhaust swirled through the cab of the locomotive, temperatures rose to 130°F. Visibility dropped to zero, as black diesel soot and oil coated every gauge and covered the two men inside the cab. It was a reminder of what locomotive engineers, firemen, and brakemen experienced for over 80 years as coal-fired steam engines pulled trains through those tunnels.14

Lewis Tunnel was excavated between the Kelly and Alleghany tunnels

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Three Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad tunnels were cut on the railroad's path along the James River between Eagle Rock and the Blue Ridge. One tunnel, located four miles downstream from Eagle Rock, reduced the sharpness of the curve required to follow the river valley.

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built a tunnel four miles from Eagle Rock, to minimize the curve required to follow the James River valley

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

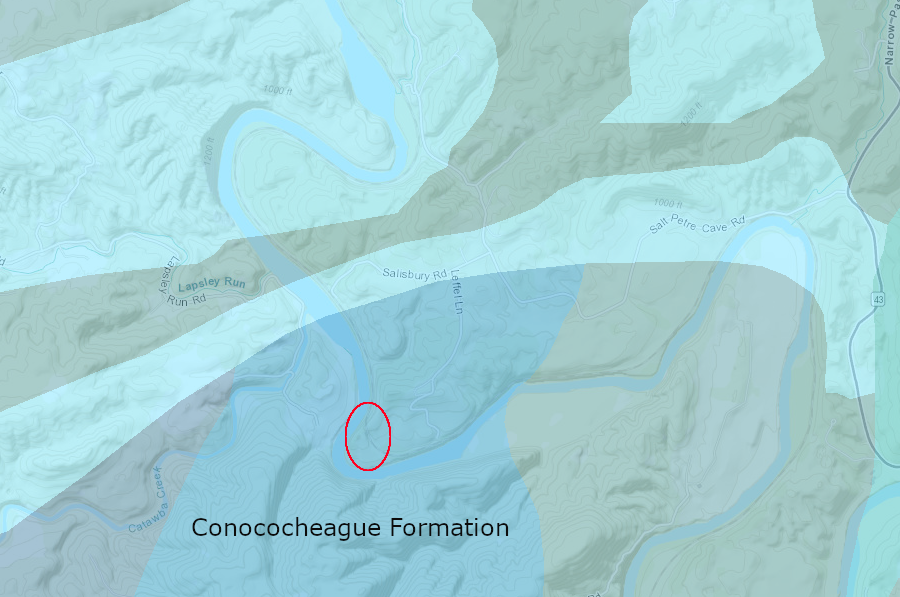

That tunnel was carved through the Conococheague Formation, a limestone deposited in the Cambrian Period over 500 million years ago. At the time, what is now Botetourt County was at the edge of the tectonic plate known as Laurentia. It was south of the equator and rotated about 90° to face south.

the tunnel near Eagle Rock was carved through the Conococheague Formation, limestone that formed over 500 million years ago

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Online Mapping Tool

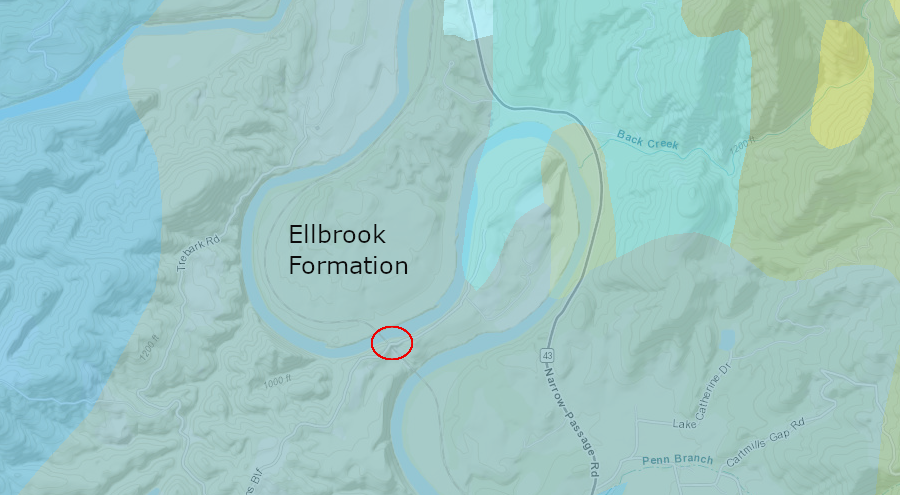

The tunnel at Horseshoe Bend was cut through the Elbrook Formation, another limestone in the Valley and Ridge physiographic province that was deposited in the Cambrian Period. That tunnel eliminated the need to build over three miles of track.

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built a tunnel at Horseshoe Bend on the James River, five miles upstream from Buchanan

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the tunnel at Horseshoe Bend cut through sediments deposited in the Cambrian Period

Source: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, Online Mapping Tool

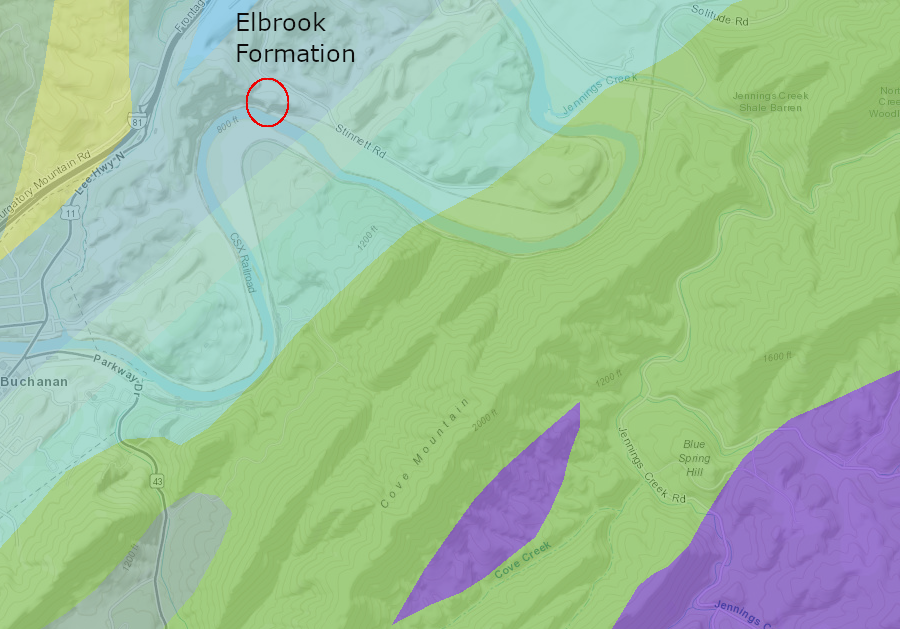

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad carved the Wasp Rock tunnel one mile downstream from Buchanan, and about a half-mile east of I-81. It also cut through a wedge of the Elbrook Formation.

the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built Wasp Rock Tunnel

Source: Google Maps

the tunnel at Wasp Rock was also cut through the Elbrook Formation, deposited in the Cambrian Period

Source: Virginia Department of Energy, Geology and Mineral Resources

CSX trains loaded with coal still pass through the Wasp Rock tunnel near Buchanan

Source: YouTube, CSX Coal EB at Wasp Rock Tunnel (by GcHawkins)

In the Blue Ridge province, four railroad tunnels were cut through the hard volcanic rock by Irish laborers and enslaved men hired from their owners. Claudius Crozet was the engineer who designed the tunnels and managed the project. He hired one contractor to construct the smaller Brooksville and Greenwood tunnels, plus the 100-foot Little Rock tunnel between them.

The other contractor that Crozet hired to build the Blue Ridge Tunnel at Afton Mountain was unable to complete the job which he started in 1850. The contractor working on the three shorter tunnels took over, and completed the project in 1858.

Irish immigrants and enslaved men carved the original Blue Ridge Tunnel in 1850-58, allowing trains to pass beneath Rockfish Gap

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, East Portal of the Blue Ridge Tunnel built between 1850 and 1858

The Blue Ridge Tunnel allowed Virginia Central Railroad trains to travel between Charlottesville to Staunton. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad "daylighted" two of the three small tunnels on the eastern side of Rockfish Gap by removing their rock roofs, but trains still pass through Little Rock Tunnel. The stone marker erected over the Greenwood Tunnel to honor Claudius Crozet, who engineered the tunneling project, was moved to his gravesite at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). Crozet had died in Midlothian in 1864 and been buried at Shockoe Hill Cemetery, but his remains were transferred from Richmond to VMI in 1942.

A replacement tunnel at Rockfish Gap was excavated in 1942-1944 to accommodate larger trains. An attempt to convert the original Blue Ridge Tunnel into an underground propane storage tank failed in the 1950's. The cracks in the greenstone that allowed water to leak into the tunnel also allowed pressurized gas to escape.

The original tunnel sat empty for forty years, and then was converted into a hiking trail for tourists after almost two decades of work and $4 million invested in the conversion. The public was allowed to start walking through the old tunnel in November, 2020.15

a replacement tunnel was constructed in 1942-44 underneath Rockfish Gap, and is still in active use

Source: Flickr, Blue Ridge Tunnel 1942-1944 (by "red, white, and black eyes forever")

The one tunnel built for cars on Skyline Drive was cut in 1932 through Mary's Rock, south of Thornton Gap. Careful blasting of nearly 700 feet through the rock avoided scarring the hillside and preserved the natural appearance of the portals, including an intrusion of greenstone (metamorphosed basalt) at the north end. The rock excavated to make the tunnel was used for construction of an overlook on the south end.

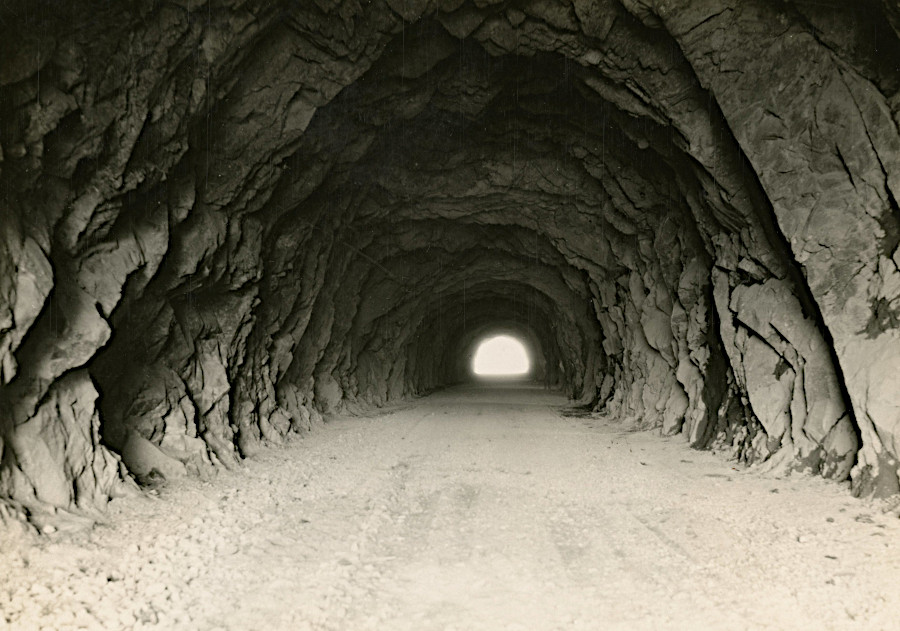

the tunnel on Skyline Drive was unlined in 1932

Source: National Archives, Interior of tunnel on Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park, Virginia

Fractures in the metamorphosed granite above the tunnel allowed water to drip inside during the summer, and produced icicles in the winter. The tunnel was lined with concrete in 1958 to reduce the hazard of icicles crashing onto vehicles. In 2016, the lining was repaired and cracks were sealed.16

tunnel at Mary's Rock on Skyline Drive, under construction

Source: National Park Service, Shenandoah National Park, Skyline Drive Construction

Mary's Rock tunnel

Source: Eric B. Walker, Flickr

There is just one tunnel on the Virginia portion of the Blue Ridge Parkway, built near the crest of the mountains south of Skyline Drive. The Bluff Mountain tunnel is at Milepost 53.1 in Amherst County, east of Natural Bridge.

Elsewhere in Virginia, the National Park Service's landscape architects and highway engineers managed to locate the road in places where cut-and-fill embankments would not create unacceptable visual scars. In North Carolina, scenic and engineering considerations led the Federal agency to build 25 tunnels plus the Linn Cove Viaduct.17

Bluff Mountain tunnel on Blue Ridge Parkway

Source: National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway, Tunnels

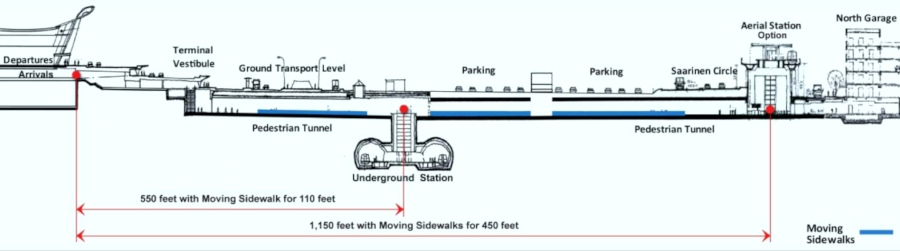

Within the Culpeper Basin of the Piedmont physiographic province, there is one transportation tunnel . The AeroTrain tunnel at Dulles International Airport carries passengers between the main terminal and satellite terminals.

Passengers walk and ride the AeroTrain underneath the runways, traveling between the main terminal and the buildings with jetways where airplanes load passengers. The track-based underground system replaced most of the mobile lounges known as People Movers, which used the same tarmac as the airplanes and caused delays. The airport tunnels were built using a combination of the New Austrian Tunneling Method, cut-and-cover, and tunnel boring machine techniques.

High cost was the reason for dropping plans for the planned tunnel and underground Metrorail Silver Line station at Dulles International Airport.

In 2007, the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (WMWAA) was given authority to build the Silver Line for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), also known as Metro. Constructing the underground track and station at Dulles International Airport using the New Austrian Tunneling Method and tunnel boring machines was considered. To minimize costs, in 2011 the agency decided to use the less-expensive, more-disruptive cut-and-cover technique. Later, it chose to make the entire station and track above the ground.18

the Silver Line station at Dulles was planned to be underground, but to minimize costs the tunneling was eliminated

Source: Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, Airports Authority Board Selects Dulles Airport Metro Station Location

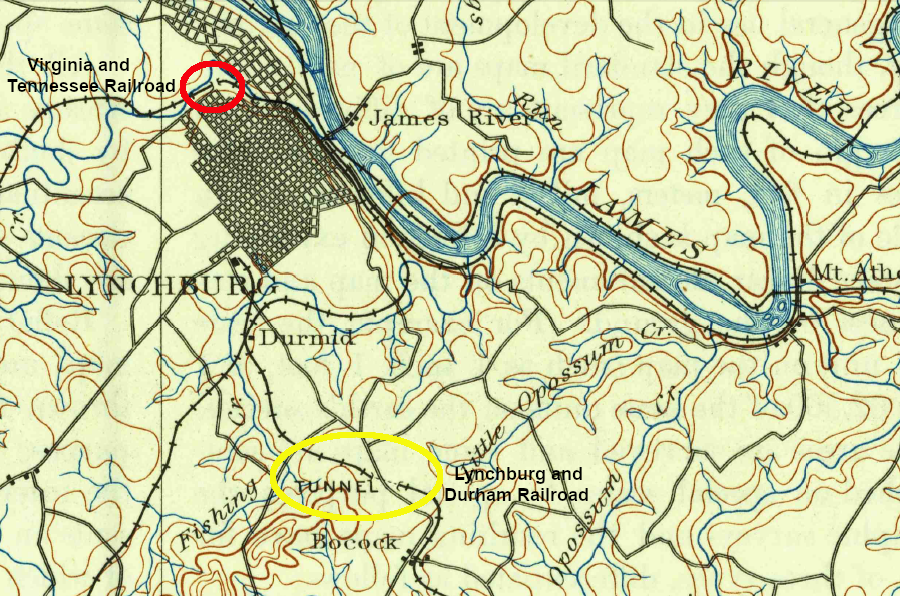

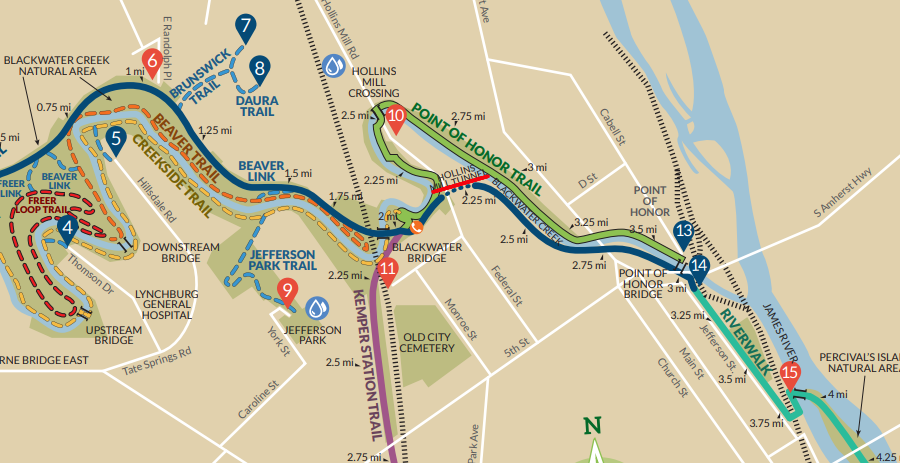

Further south in the Piedmont, the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad built the 508-foot Hollins Tunnel west of Lynchburg in 1851-52. Drilling through the ridge underneath what is now Hollins Mill Road allowed the engineers to avoid a sharp bend in Blackwater Creek. The tunnel was used for 130 years. In its last years, the only Norfolk Southern trains which passed through the tunnel were interchanging railcars with the CSX.

The Lynchburg and Durham Railroad carved the Durham Line Street tunnel in 1889 southeast of Lynchburg, underneath Martin Street near Fairview Heights.

the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad cut its tunnel in 1851-52, while the Lynchburg & Durham Railroad built the Durham Line Tunnel in 1889

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lynchburg VA 1:25,000 quadrangle (1892)

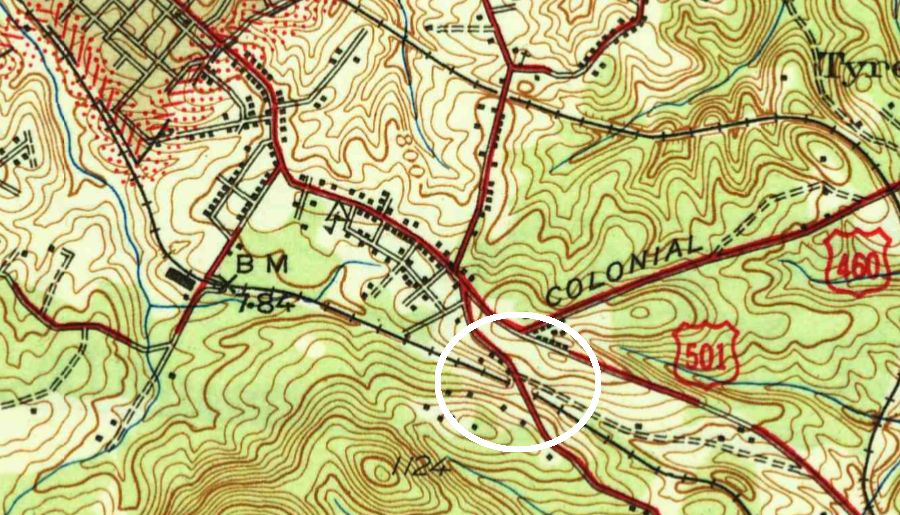

in 1944, the Norfolk and Western Railroad used the Durham Line Tunnel at the north end of Candler Mountain

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lynchburg VA 1:62,500 quadrangle (1944)

the Durham Line Tunnel underneath Martin Street is still in active use

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

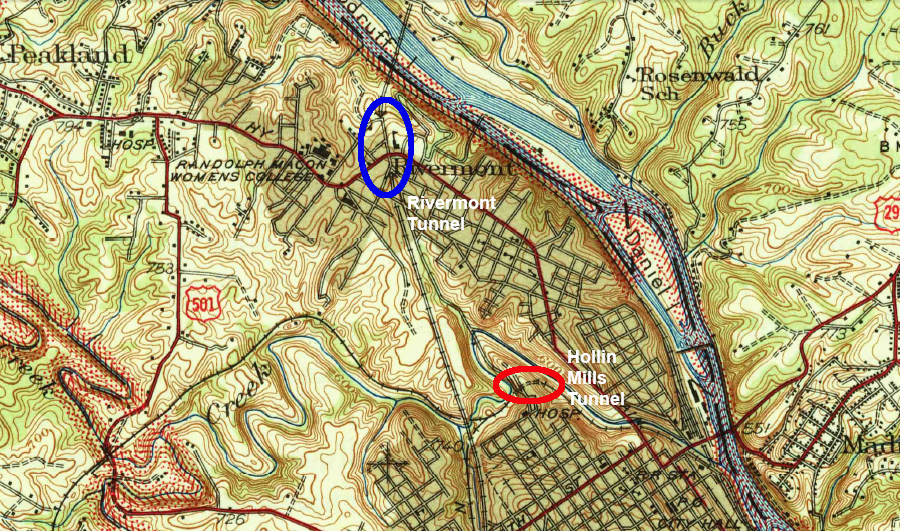

When the Southern Railway built a new mainline through Lynchburg in 1910, it cut the Rivermont Tunnel for trains to pass through the ridge on the south bank of the James River.

the Southern Railway's Rivermont Tunnel was located about one mile north of the Hollin Mills Tunnel

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Lynchburg VA 1:62,500 quadrangle (1944)

The Norfolk and Western Railroad abandoned the Hollins Mill Road in 1982. After a rails-to-trails conversion, it is now used by hikers and bikers.19

today, hikers/bikers rather than trains use the Hollins Mill Tunnel west of Lynchburg

Source: Lynchburg Parks and Rec, Hiking and Biking Trails

On the northeastern edge of the Piedmont physiographic province at Tysons, there is one Metrorail tunnel for the Silver Line (in addition to other Metro tunnels on the Coastal Plain). Plans for a longer Tysons tunnel and four underground stations there were dropped in order to minimize construction costs.

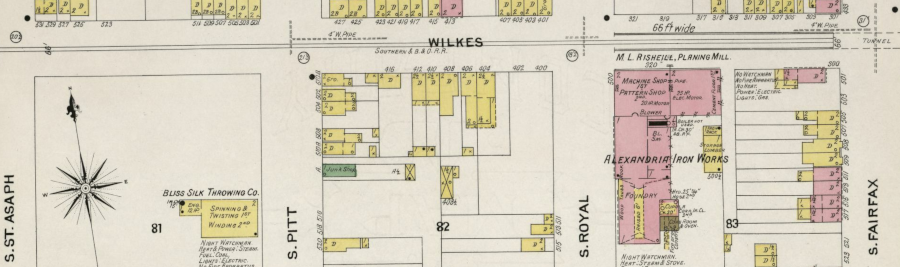

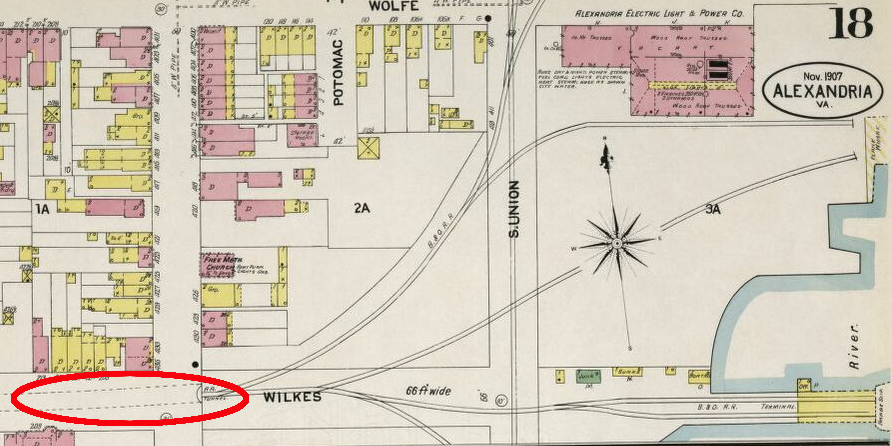

On the Coastal Plain, the first transportation tunnel was constructed by the Orange and Alexandria Railroad in Alexandria. The Wilkes Street tunnel opened in 1851, minimizing the grade for trains to reach the wharves along the Potomac River waterfront.

the Wilkes Street tunnel stretched from South Fairfax Street to South St. Asaph Street

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Alexandria, Independent Cities, Virginia (Sanborn Map Company, November 1907)

the Wilkes Street railroad tunnel in Alexandria connected the waterfront to the main Orange & Alexandria Railroad station

Tracks were removed in 1975, but the tunnel was kept and still serves as part of a city bike path. Alexandria refurbished the tunnel in 2007-2008, adding lights and steel reinforcement ribs to support the stone and brick roof and walls.20

the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad ferried railroad cars across the Potomac River, and the Southern Railway carried them south via the Wilkes Street tunnel (highlighted in red)

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Alexandria, Independent Cities, Virginia (Sanborn Map Company, November 1907)

Between 1871-73, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway constructed the 3,927-foot long Church Hill Tunnel in Richmond. The cost to build one of the longest tunnels in the United States at the time was justified by the ability to connect to new docks on the James River, at what became Intermediate Terminal. In 1901 the railroad closed the tunnel, after completing a three mile long, double track elevated viaduct along the James River to provide a better connection to tracks running all the way to Newport News.

Increased traffic caused the railroad to start reopening and widening the tunnel in 1925. However, the brick ceiling collapsed during the project and at least four workers were killed. The railroad concluded that it would be too expensive to complete the project through the soft sedimentary formations and sealed up the tunnel. The work train and at least some bodies are still buried underneath Jefferson Park on Church Hill.21

The eastern entrance to the Church Hill Tunnel is in a gulley filled with vegetation, but the western entrance is easily accessible at the corner of Cedar and East Marshall Streets. The sand which was placed in the tunnel in the closure process has settled, and the wooden cribbing has rotted. It is possible that the roof of the tunnel could settle further, potentially impacting the houses built on top of it.22

the east and west portals of the Church Hill Tunnel are sealed with concrete

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

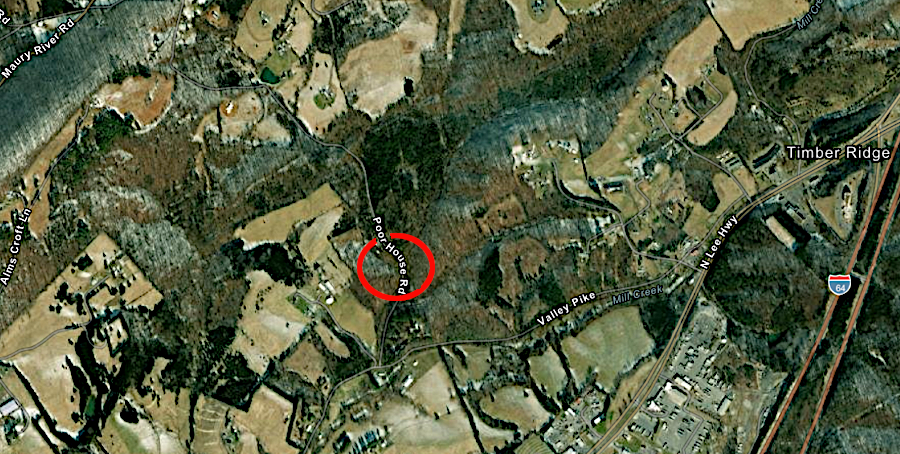

Some railroad tunnels are reported to be haunted. At the now-abandoned Poor House Tunnel, built for the Valley Railroad to pass under Poor House Road in Rockbridge County, ghosts of two little girls reportedly call to visitors and try to lure them into the tunnel.

ghosts at Poor House Tunnel in Rockbridge County supposedly try to lure people into the tunnel

Source: Kipp Teague, Poor House Road Tunnel near Lexington - dates to 1883; ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Big Bull Tunnel in Wise County was lined with brick in 1903 to reduce cave-ins and fallen rock. During an inspection in 1905:23

Big Bull Tunnel is supposedly haunted

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Tazewell Republican (January 25, 1906)

Big Bull Tunnel is west of the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), St. Paul VA 1:24,000 quadrangle (2019)

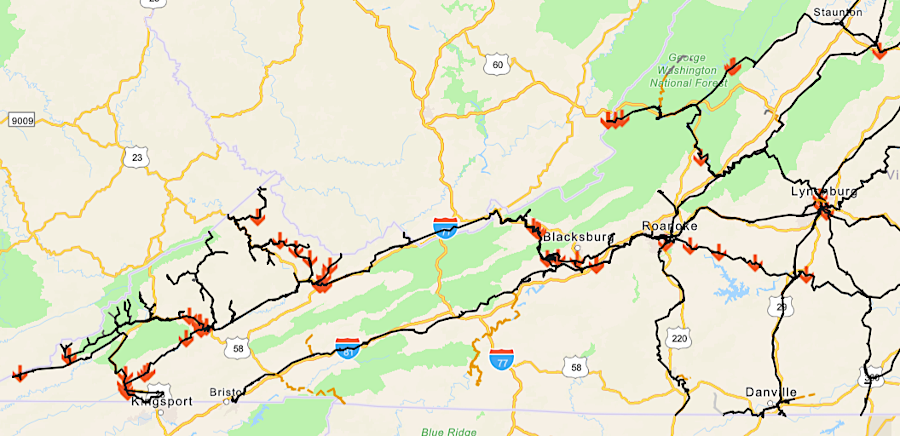

tunnels on active freight rail lines in 2022

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), DRPT Rail Database

There are four Metrorail tunnels in the Coastal Plain of Northern Virginia, in addition to the Metro tunnel at Tysons and the Wilkes Street railroad tunnel in Alexandria.

underground Metrorail stations in Virginia now have covers over the escalators that bring customers to the surface

Source: Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, Momentum, The Next Generation of Metro, Strategic Plan 2013-2025 (p.70)

Blue and Yellow line trains go through a tunnel north of the Braddock Road station. The tracks are also underground from a spot east of Crystal City to the edge of the Potomac River, which the Yellow Line crosses on a bridge.

the Yellow Line goes underneath North Henry Street (Route 1) near the Braddock Road station

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

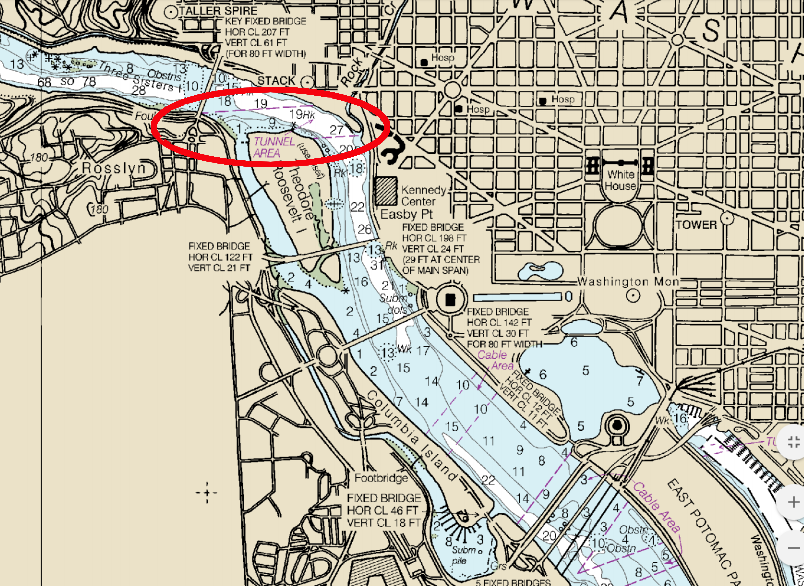

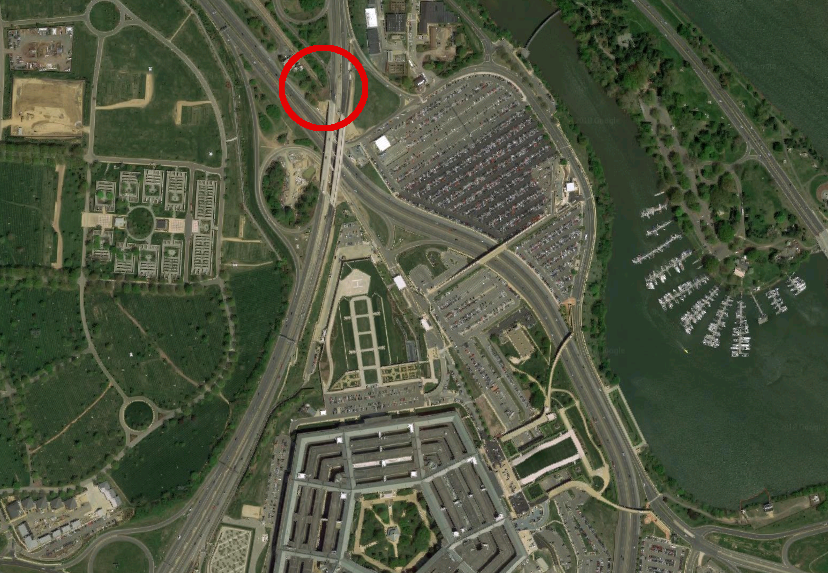

The Blue and Yellow lines diverge at the Pentagon. The Blue Line travels on the surface along the edge of Arlington Cemetery, but goes underground again to reach the Rosslyn station. The Blue, Orange, and Silver lines cross the Potomac River in a tube excavated through the bedrock.

the Metrorail tunnel for the Blue, Orange, and Silver lines between Rosslyn-Foggy Bottom stations is marked on navigation charts

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coast Survey Chart 12289

The Orange/Silver line is buried underground between Ballston and the Potomac River, just past the Rosslyn station.

the Orange/Silver lines go underground just west of Ballston

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Yellow line has two tunnels between the Potomac River and the Braddock Road station, built by the cut-and-cover method. The Blue Line is underground from the Potomac River through the Rosslyn Station. It surfaces for the Arlington Cemetery station, and then goes underground again for the Pentagon, Pentagon City, and Crystal City stations.

The Crystal City station provides underground connections to the Crystal Underground complex of retail outlets and offices. There was originally another underground station on the Blue Line, at the Pentagon. That station allowed employees with appropriate security clearances to get direct access from the shopping plaza. Tightened security after 9/11 led to the closure of the underground access point, forcing Metrorail customers to come and go via the surface.

In the underground tunnel just south of the Pentagon is the beginning of a tunnel for a line that was never built. The only evidence of the proposed line to Columbia Pike is in the paper trail of Metro planning and the stub of that tunnel near the Pentagon.

The Blue Line shares the tunnel between the Crystal City and Braddock Road stations with the Yellow Line, as well as the tunnel at the Pentagon City and Crystal City stations.

The Blue Line shares the Rosslyn station with the Orange/Silver lines. The underground platform was built at two different levels, allowing the lines to avoid an at-grade intersection.

The Rosslyn station is the deepest Metrorail tunnel in Virginia. A trip on the escalator takes passengers 200' to the surface.24

Metro blasted through Piedmont bedrock below Coastal Plain sediments to construct tunnels in northern Washington and in Arlington, Virginia

Source: George Mason University, Building the Washington Metro

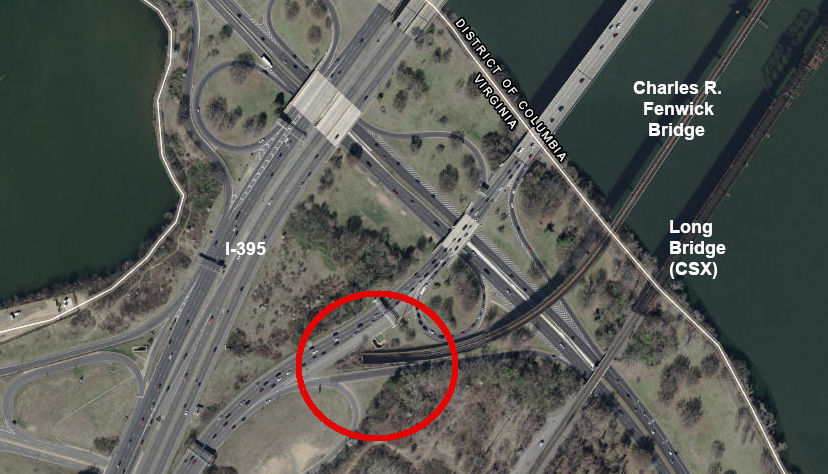

after crossing the Potomac River on the Charles R. Fenwick Bridge, the Yellow Line goes into a tunnel to the Pentagon City station

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the Blue Line goes into a tunnel to get beneath the Pentagon parking lots

Source: Google Maps

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (Metro) chose to use the New Austrian Tunneling Method to expand the Rosslyn station and open a new station entrance in 2013. The bus-only tunnel for passengers to switch to Metrorail, below the 31-story south tower in the Central Place development, is located at ground level between North Moore Street and North Lynn Street. A similar tunnel was included in the Pentagon building, but closed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.25

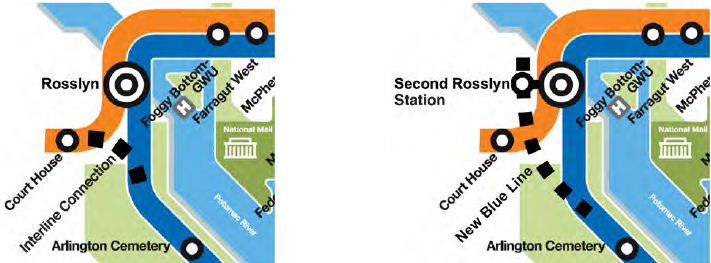

The agency's "Momentum, The Next Generation of Metro, Strategic Plan 2013-2025" proposes expanding the Blue Line's underground infrastructure further at Rosslyn.

Possibilities include building new underground track to connect the Blue Line to the Orange/Silver lines, and potentially excavating a completely new station dedicated for Blue Line trains. A new station would enhance the potential for building another tunnel underneath the Potomac River for a new east-west line.26

more tunneling will be required at Rosslyn if Blue Line infrastructure is expanded, as proposed by Metro

Source: Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, Momentum, The Next Generation of Metro, Strategic Plan 2013-2025 (p.62)

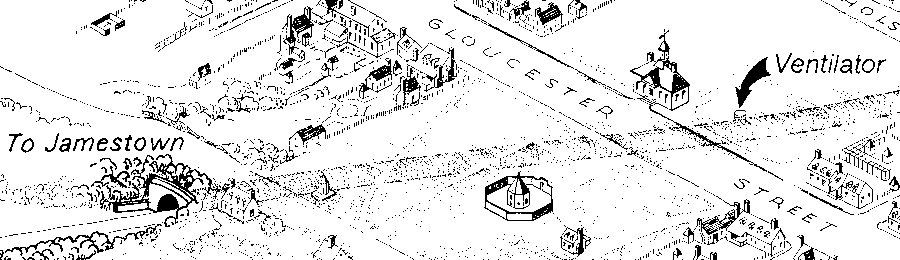

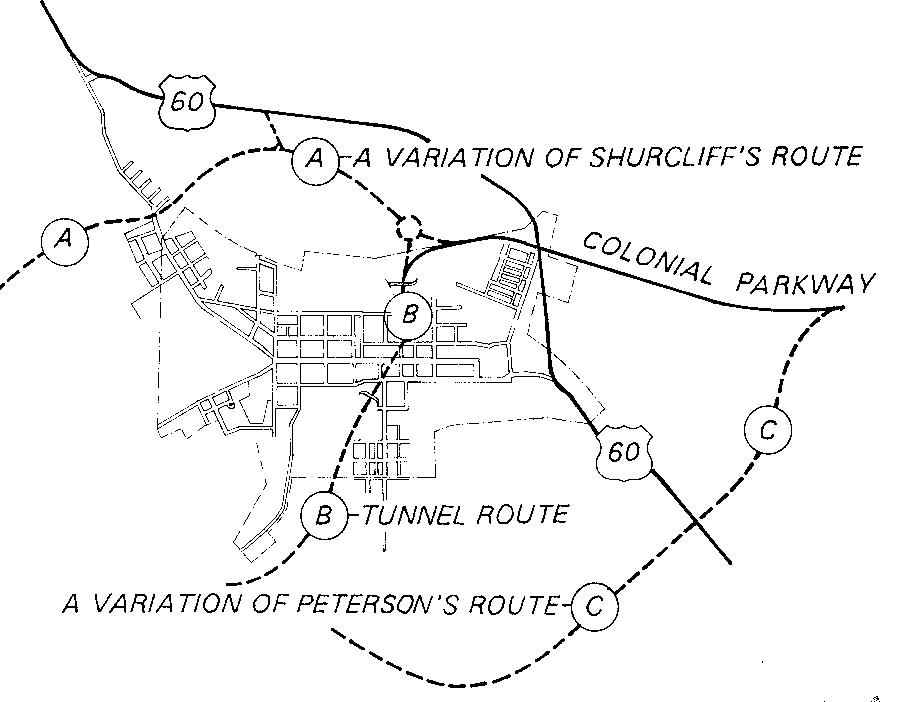

The Colonial Parkway goes through a tunnel stretching 1,190 feet underneath the historic area of Williamsburg. Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, the rector of Bruton Parish Church and sparkplug for the restoration of the town, is credited with proposing the idea.

Local, National Park Service, and Williamsburg Foundation (now Colonial Williamsburg) officials debated alternative routes for the parkway before deciding to build a tunnel. A top priority of the Williamsburg Foundation, advocated by Arthur Shurcliff, was to avoid impacting John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s home at Bassett Hall.

The tunnel was built in 1940-1942, using traditional cut-and-cover techniques. The Market Square was rebuilt on top of the tunnel. A ventilator shaft was planned midway, near the James City County courthouse. A metal grate near the stocks and pillory allows ventilation today, without a visible shaft on the surface.

There were several landslides during construction, and the tunnel contractor was blamed for poor performance. Workers were injured, and nearby structures were damaged as the ground slumped.

excavating the tunnel created a big trench through the historic district, which was then covered

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, Colonial Parkway, Williamsburg Tunnel

World War II delayed completion of the tunnel's interior. After paving and installation of lights, it opened to traffic in 1949. Though bicycles are welcome on the Colonial Parkway, they are not allowed in the tunnel and must take a detour via streets in Williamsburg.27

two main alternatives were considered for routing Colonial Parkway through Williamsburg, as well as a tunnel

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, Colonial Parkway, Williamsburg Tunnel

vehicles pass underneath Historic Williamsburg through a tunnel on the Colonial Parkway

Source: Library of Congress, Historic American Engineering Record, View to Southwest of Williamsburg Tunnel (HAER No. VA-48-D)

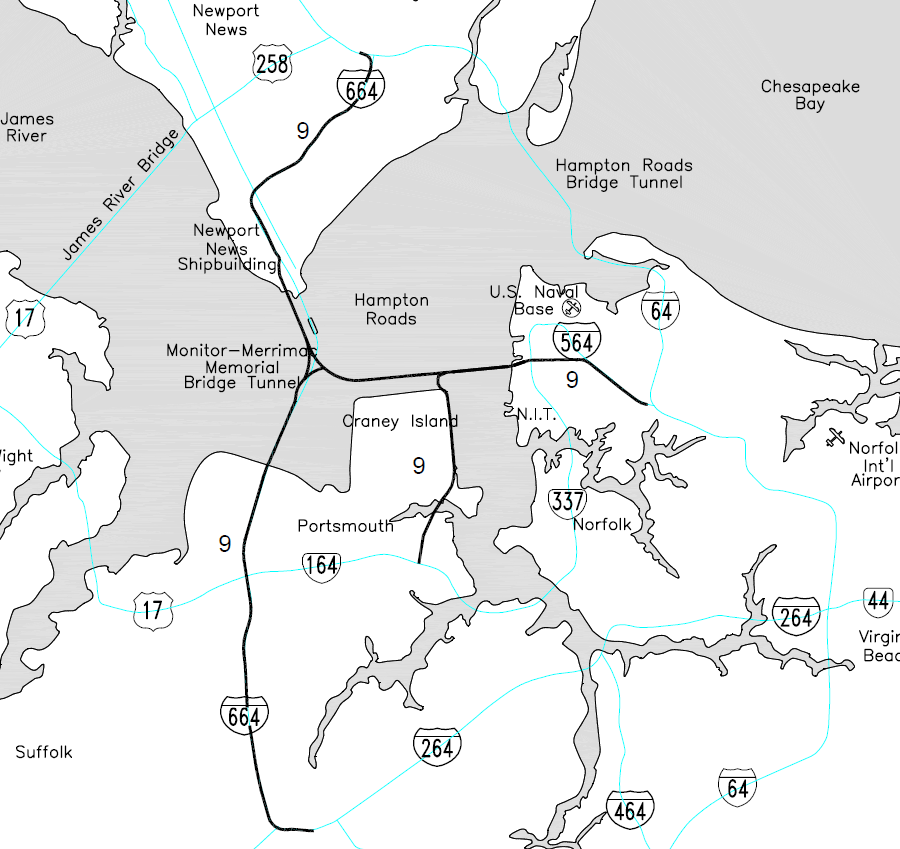

Also on the Coastal Plain, there are five highway tunnels in Hampton Roads: Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, Midtown Tunnel, Downtown Tunnel, and the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel. To minimize construction costs, bridges were constructed from the shoreline to artificial islands which anchored the ends of tunnel segments.

The US Navy required that the shipping channels not be crossed by a bridge and forced the use of tunnels. The military feared an enemy could destroy a bridge and cause the wreckage to block the channel, bottling up warships in the Elizabeth River, James River, or Chesapeake Bay.

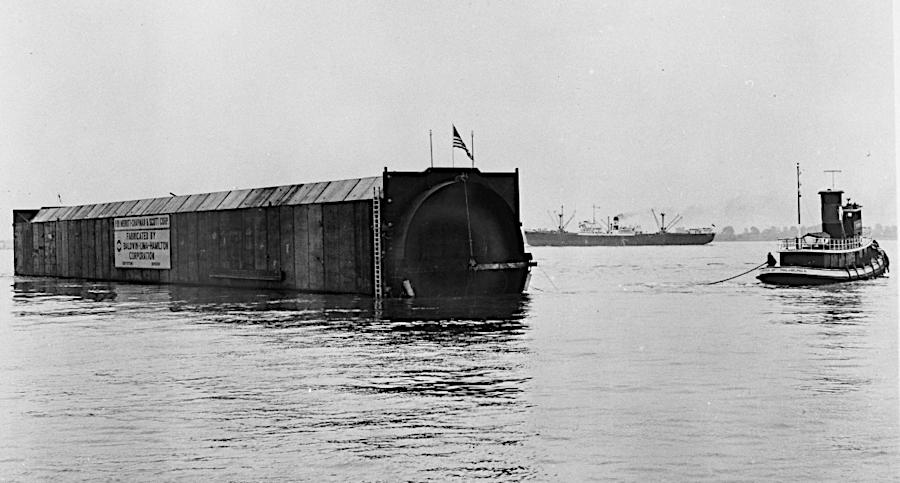

The first ten tunnels were constructed by building segments of steel tubes onshore and floating them to the site. Each end was sealed, making the segments airtight. Once placed in the correct location, weight was added to sink each segment. The segments were placed, one at a time, into a trench excavated in the river channel. Sediments were then added on top to completely bury the tunnel, limiting the risk that a ship's anchor might puncture the tubes.

The tube segments were aligned carefully so they could be connected tightly to create a waterproof seal. Then the ends of each segment, no longer needed to keep water out, were removed to allow for travel through the entire underwater tunnel. Once lights and ventilation ducts were installed, and the roadway completed, the tunnel was opened for traffic.

until the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was expanded with a boring machine, all tunnels in the region were built with steel tubes floated to an excavated trench

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, HRBT History

The Norfolk-Portsmouth Bridge-Tunnel, known today as the Downtown Tunnel, was the first to be completed in 1952. A parallel two-lane tunnel was completed in 1987.

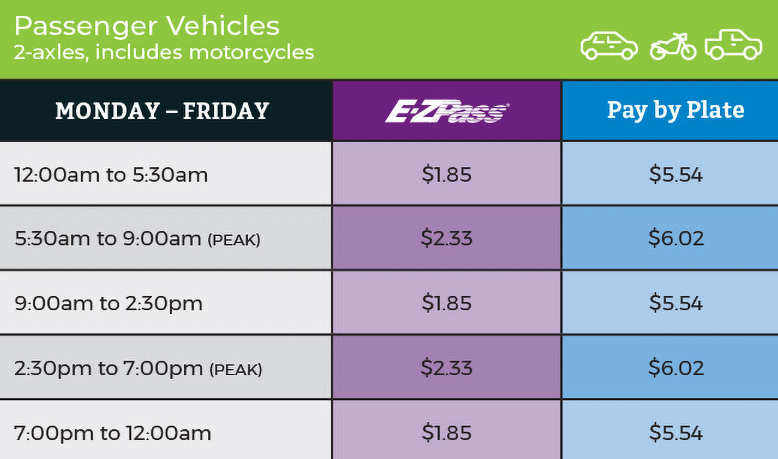

The first two-lane tube of the Midtown Tunnel opened in 1962. A parallel tube to double capacity was added in 2016, constructed in a public-private partnership that authorized a private company to collect tolls for 58 years. Elizabeth River Crossings (DriveERT) will collect tolls on the Midtown and Downtown tunnels until April 13, 2070.28

tolls for passenger cars using the Midtown and Downtown tunnels in 2020

Source: DriveERT, Toll Rates

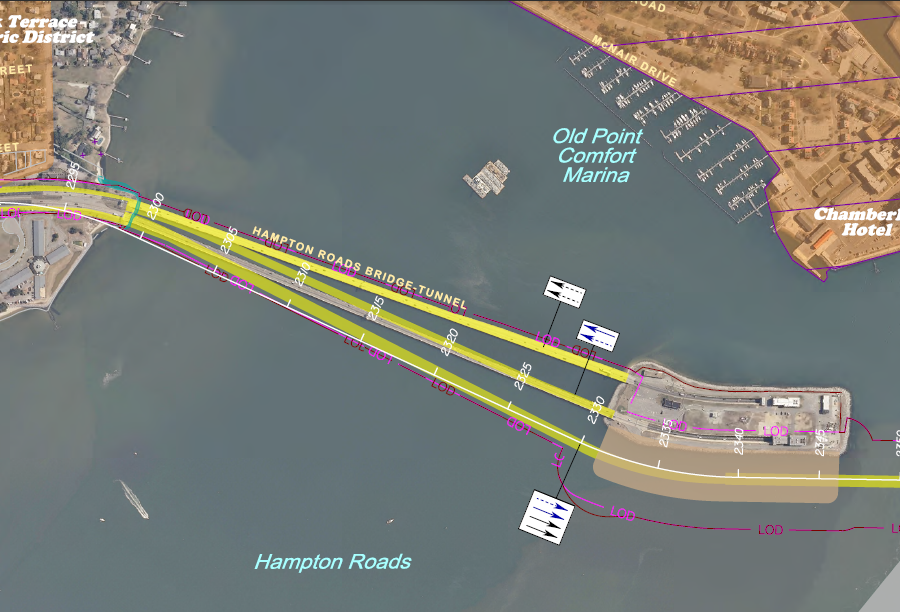

The first tunnel of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel was built in 1957. Its second tube was completed in 1976.

Two new two-lane tunnels are planned for completion in 2024. That project was chosen as the region's top priority, after decades of debate over transportation alternatives. It will double the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel to carry eight lanes of traffic.

The existing two tunnels will be configured to carry traffic west, from Norfolk to Hampton. The four new lanes will be located on the upstream (western) side of the existing facility, in part to avoid conflicts with the historic site of Fort Wool.

the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel capacity will be doubled from four lanes to eight

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel

Two lanes will be for general purpose traffic, one lane will be for High Occupancy Toll (HOT) traffic at all times, and one lane will be a shoulder for most of the day. That shoulder lane will normally be a refuge for cars that break down, but will be opened up as a second HOT lane when demand is sufficient.

On land, the I-64 approaches will be widened to just six lanes. Widening the highway on land to eight lanes would require condemning private property, and getting some of the Naval Base Norfolk property. Building an eight-lane Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel rather than expanding it to just six lanes will add expense, and each approach will still be a six-lane bottleneck. However, regional leaders anticipated this project would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Adding just two lanes now, and getting funding for another expansion of the bridge-tunnel to add two more lanes at a later date when approaches might also be expanded, was too great of a political risk. Overspending to create an eight-lane facility was seen as a smart investment, one that guaranteed the full eight-lane expansion would occur.29

the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel expansion was placed on the west side

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Hampton Roads Crossing Study, Environmental Assessment Re-evaluation of the Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (Appendix A)

The expansion required paving over the 20-acre southern artificial island to create a staging platform. That displaced Virginia's largest waterbird colony; after the island's construction 40 years earlier, as many as 25,000 terns, black skimmers and gulls began nesting on six acres on the island after migrating back to Virginia each April.

A 2017 re-interpretation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act by the US Fish and Wildlife Service allowed such "incidental bird takes" without any mitigation. After a public uproar, state agencies developed a plan to create an alternative nesting area by enhancing habitat on Rip Raps Island (site of Fort Wool) and potentially placing barges there to provide additional space.30

artificial islands anchor the ends of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel and nine other tunnels in the region

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, HRBT History

The Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1992. It too has twin two-lane tunnels, to serve four lanes of traffic.31

inside the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel

Two Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel tunnels were opened in 1964, one underneath the Thimble Shoals channel and one underneath the Chesapeake Channel. Construction of a second tube below the Thimble Shoals channel started in 2018. That project was the first to use a Tunnel Boring Machine, rather than placing prebuilt tubes inside an excavated trench.

The Tunnel Boring Machine, named Chessie, will excavate 50,000 truckloads of sediments. Chessie is designed to add solvents at the boring face to facilitate the removal of dirt, so excavated material is expected to exceed the acceptable level of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH). Dirt which exceeds the threshold must be buried in a landfill, not trucked to a borrow pit that is available on the Eastern Shore or deposited offshore in a designated disposal site.

When the second Midtown Tunnel tube was dug, 10% of the excavated Elizabeth River sediments were excessively contaminated with hydrocarbons from earlier industrial activities in the area. The trenching process, unlike the boring machine, added no solvents, and 90% of the excavated sediments were "clean enough." Those could be barged to the ocean disposal site, a far cheaper method of disposal than trucking to a landfill.32

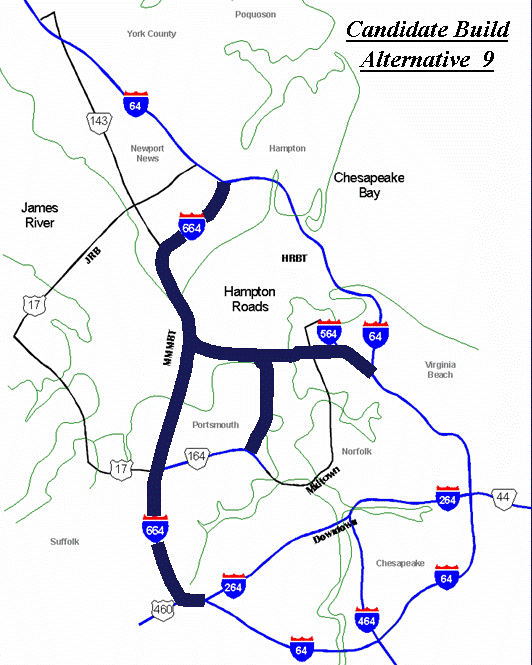

A new bridge-tunnel tunnel, the "Third Crossing" or "Patriot's Crossing," is in the planning stages. The decision to Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel limits funding for the Third Crossing, but the transportation planners have already selected a preferred route. Alternative 9 will connect I-64 in Norfolk to I-664 in Suffolk/Newport News, by adding a new bridge-tunnel north of Craney Island. It includes an over-water intersection with the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel.33

Alternative 9 of the Third Crossing is the preferred choice of the planners in Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Hampton Roads Crossing Study, Final Environmental Impact Statement (Figure 2-5)

the Third Crossing was delayed, in order to fund expansion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Hampton Roads Third Crossing - Aerial Map

Two public highways go beneath an active airport runway via a tunnel.

The Airport Road Tunnel has carried Route 118 beneath the runway at Roanoke-Blacksburg Regional Airport (ROA) since the runway was extended 900' in 1985. Like seven other highway tunnels in Virginia, that portion of Airport Road is restricted for transportation of hazardous materials.34

Route 118 passes through a tunnel below the runway at Roanoke-Blacksburg Regional Airport (ROA)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

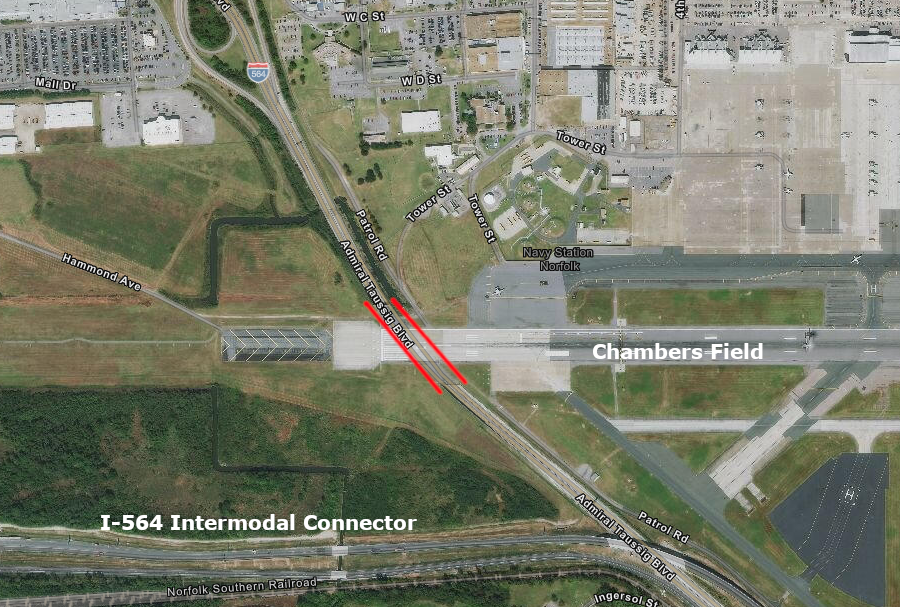

In Hampton Roads, the I-564 connection to Naval Station Norfolk goes beneath the runway of the military airport. Chambers Field was first constructed in 1918, and the 680-foot tunnel was completed in 1977 when Admiral Taussig Boulevard was upgraded to become an interstate highway spur. The US Department of Transportation has not restricted transportation of hazardous materials through the I-564 tunnel. Traffic to the military base goes below the runway, but containers and other freight shipped via the North Gate of Norfolk International Terminal (NIT) uses the I-564 Intermodal Connector and does not go through the tunnel.35

Admiral Taussig Boulevard (I-564) goes underneath the runway of Chambers Field at Naval Station Norfolk

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Two tunnels were started for construction of the James River and Kanawha Canal upstream of the town of Buchanan, on a 15-mile extension which was never opened. The 192-foot long Mason Tunnel was completed, though the canal itself never reached that point. The Richmond and Allegheny Railroad expanded that tunnel in 1881; it is still in use by the CSX Railroad.

Construction of the James River and Kanawha Canal ended in 1856 with the Marshall Tunnel still unfinished. Of the planned 1900 feet, 450 feet were excavated on the eastern end. On the western end, 200 feet of tunnel was blasted out. On both ends, tunnels planned for ventilation were dug from the surface.36

Source: FPANNortheast, Marshall Tunnel Fly Through Tour

the Mason Tunnel constructed by the James River and Kanawha Canal was expanded by the Richmond and Allegheny Railroad

Source: New York Public Library, Mason Tunnel on the C. & O. R. R., Virginia

the western end of the unfinished Marshall Tunnel is flooded now

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Facebook post (March 26, 2024)

topographic maps still show the starting points of both ends of the unfinished Marshall Tunnel through Timber Ridge in Botetourt County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

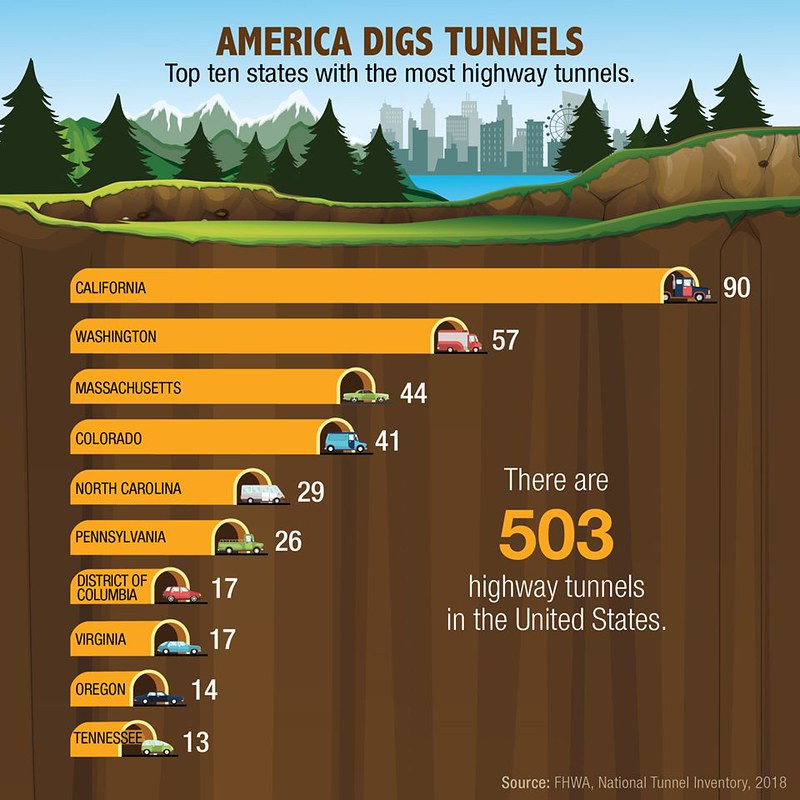

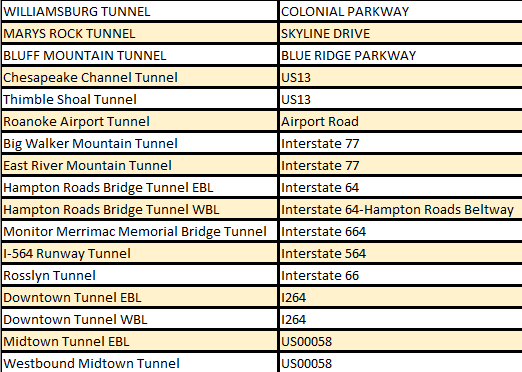

In 2023 there were 503 highway tunnels in the United States, according to the Federal Highway Administration. Other highway tunnel factoids include:37

the Federal Highway Administration calculates there are 17 highway tunnels in Virginia

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Tunnels and Download NTI [National Tunnel Inventory] Data

though two holes were bored through the mountain, Federal Highway Administration statistics treat Big Walker Mountain Tunnel as a single tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Big Walker Mountain Tunnel entrance, I-77

Across Virginia, many more additional tunnels have been constructed for purposes other than vehicle transportation. Numerous buildings have tunnels for utility pipes, or to permit people to walk between structures without having to go outside. Richmond has a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) system, where stormwater and wastewater infrastructure includes tunnels for both transport and storage. Alexandria was forced to do the same, to reduce discharge of untreated sewage after heavy rains.

The City of Staunton blasted a tunnel over one mile long (5,680 feet, to be exact) through Lookout Mountain in 1924-26. Inside the 6-fot by 4-foot tunnel, a 20-inch pipe carried water from the city's new reservoir to Staunton.38

Several tunnels are now open to hikers and bikers, and the Crozet Tunnel through the Blue Ridge is being developed for public use:

- Austinville Tunnel (New River State Park in Wythe County)

- Bee Rock Tunnel (Roaring Branch Trail in Wise County)

- Gambetta Tunnel (New River State Park in Carroll County)

- Hollins Mill Tunnel (City of Lynchburg)

- Natural Tunnel (state park in Scott County)

- Swede Tunnel, also known as Beverly Tunnel (Scott County)

- Wilkes Street Tunnel (City of Alexandria)

Gambetta Tunnel on the New River Trail, repurposed for recreational use

Source: Virginia State Parks, Gambetta Tunnel - New River Trail

tunnels on the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway cost more money to construct initially, but cutting through ridges reduced grades and curves and lowered operating costs

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

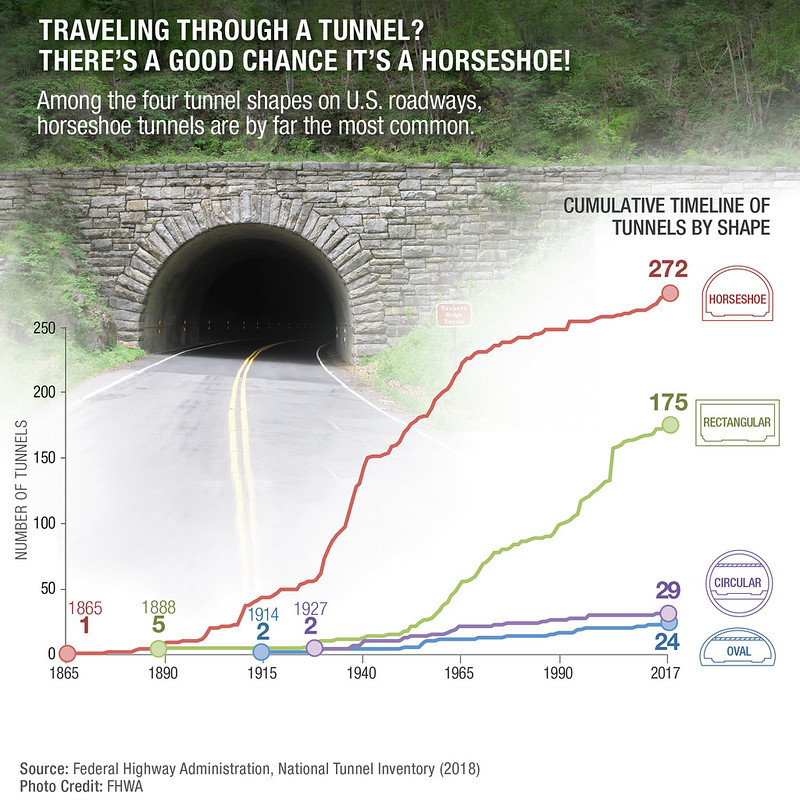

highway tunnel engineers prefer two geometrical designs

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Factoid

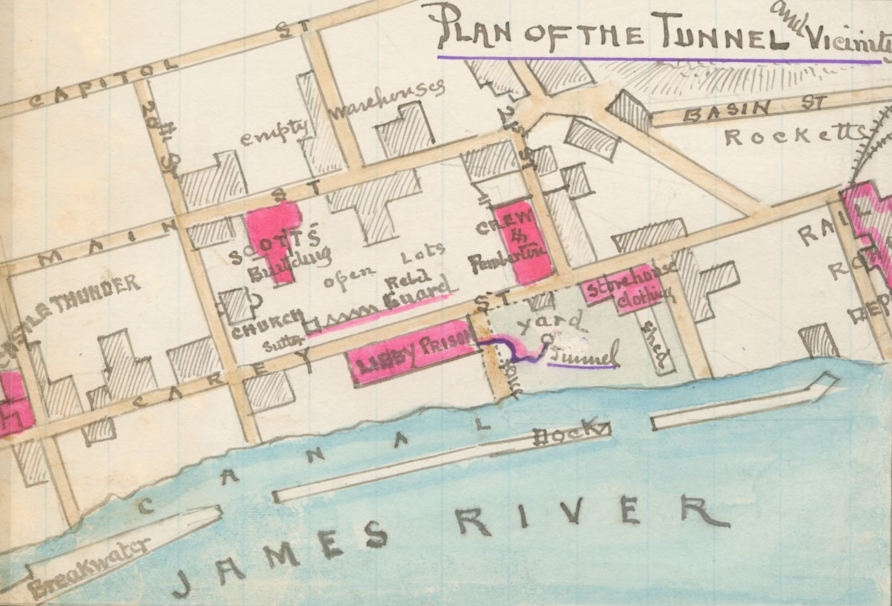

during the Civil War, Union officers dug a tunnel to escape Libby Prison in Richmond

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the tunnel and vicinity [of Libby Prison, Richmond, Va. (Robert Knox Sneden)

the Geographic Names Information System lists 67 tunnels in Virginia, or on the border

Source: US Geological Survey, Geographic Names Information System