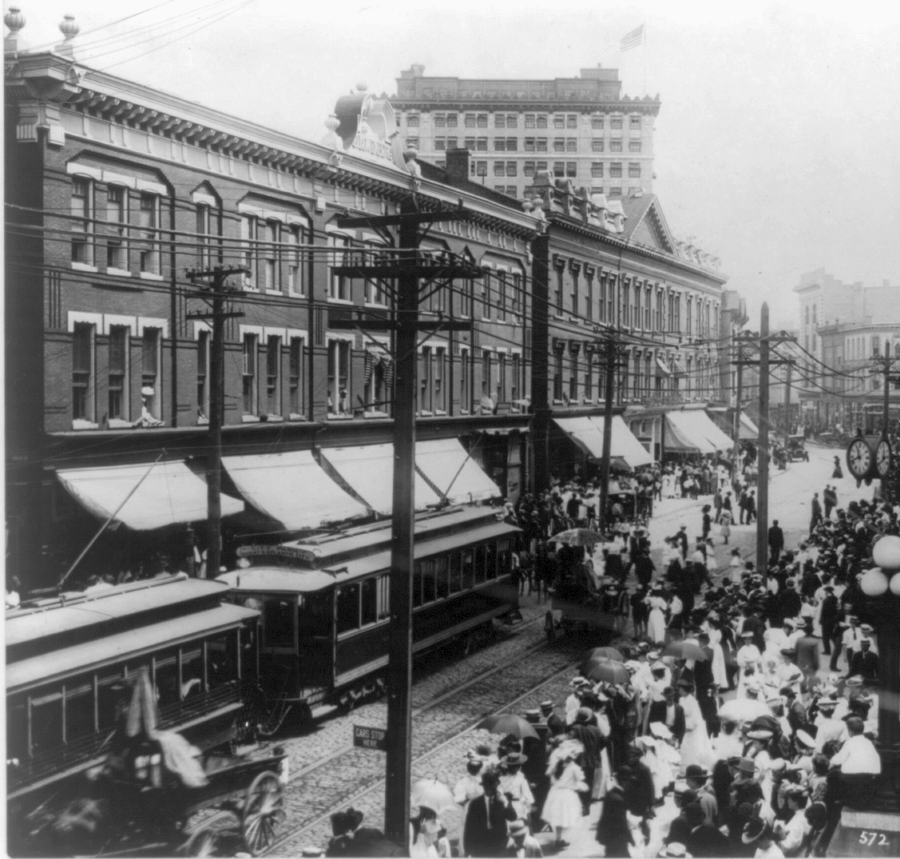

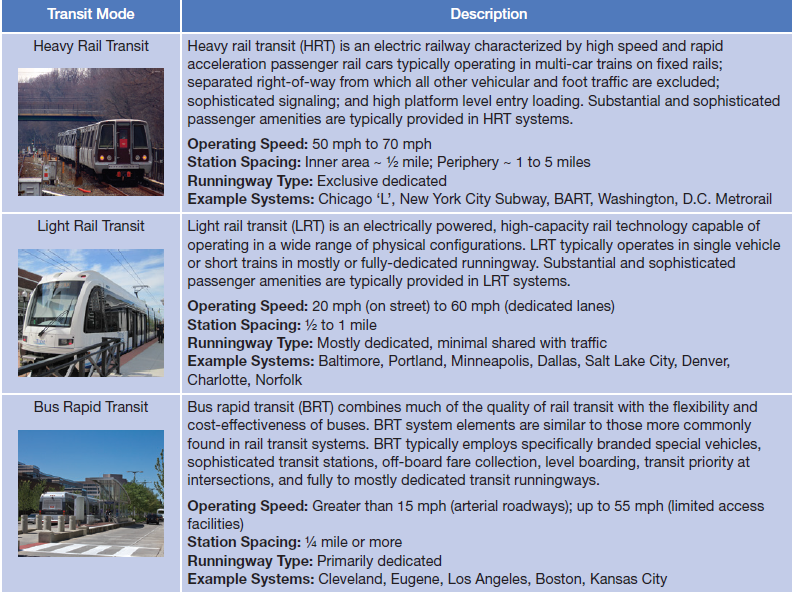

the first successful electrically-powered trolley was constructed in Richmond in 1888

Source: "Rarely Seen Richmond," Virginia Commonwealth University James Branch Cabell Library Special Collections and Archives, Broad Str. Looking West Richmond, Va

the first successful electrically-powered trolley was constructed in Richmond in 1888

Source: "Rarely Seen Richmond," Virginia Commonwealth University James Branch Cabell Library Special Collections and Archives, Broad Str. Looking West Richmond, Va

The original light rail systems in Virginia were streetcars (trolleys). Prior to Frank Julian Sprague's development of the electrical traction system in Richmond, other streetcar systems had failed in over 60 other communities. The Richmond Union Passenger Railway set the example for future electrical-powered streetcar systems when it started operations in 1888, gradually replacing the horse-drawn trolleys in use since 1860. (Not all were converted; Waynesboro's trolley was drawn by a mule for its entire time of operation between 1892-1902.)1

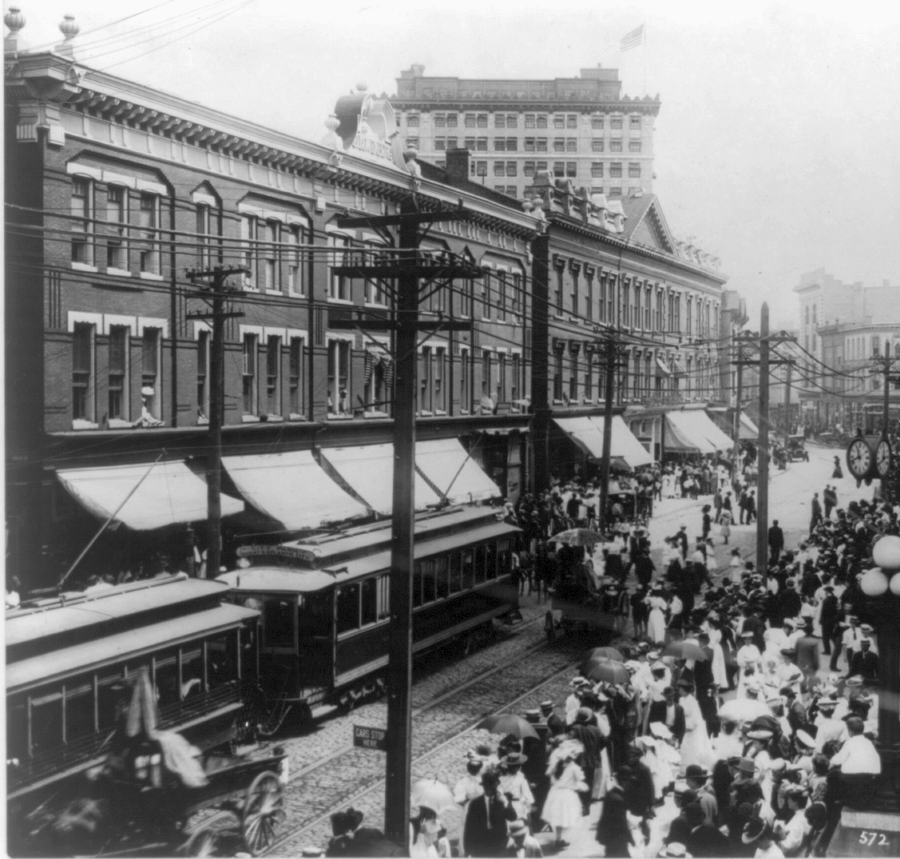

in 1906, the Norfolk Portsmouth Traction Company operated on Main Street in Norfolk; "The Tide" is not the first trolley or light rail system there

Source: Library of Congress, View of Main Street, Norfolk, Va. (1906)

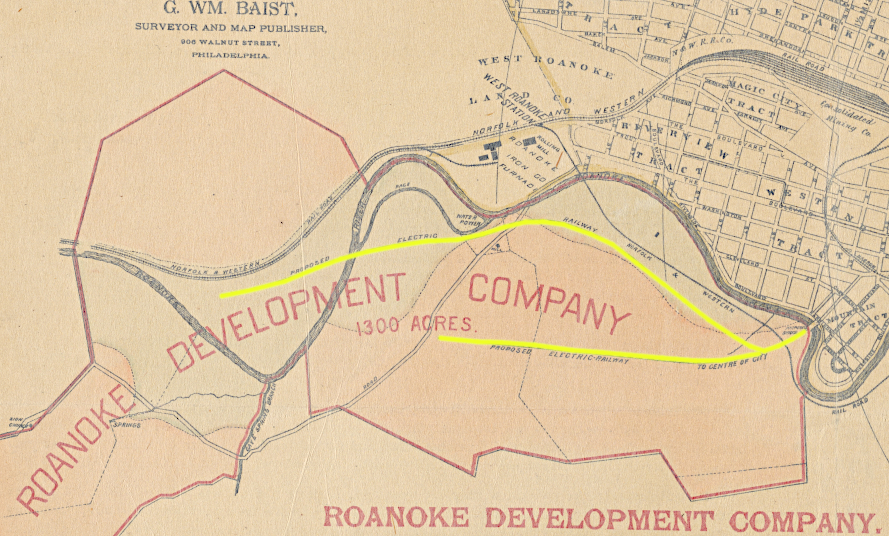

Streetcar systems were implemented nationwide in most urban areas with at least 10,000 people. The route of the lines was often based on where real estate developers sought to create new subdivisions; transit services have been designed from the beginning to facilitate the early form of suburban sprawl known as "streetcar suburbs."

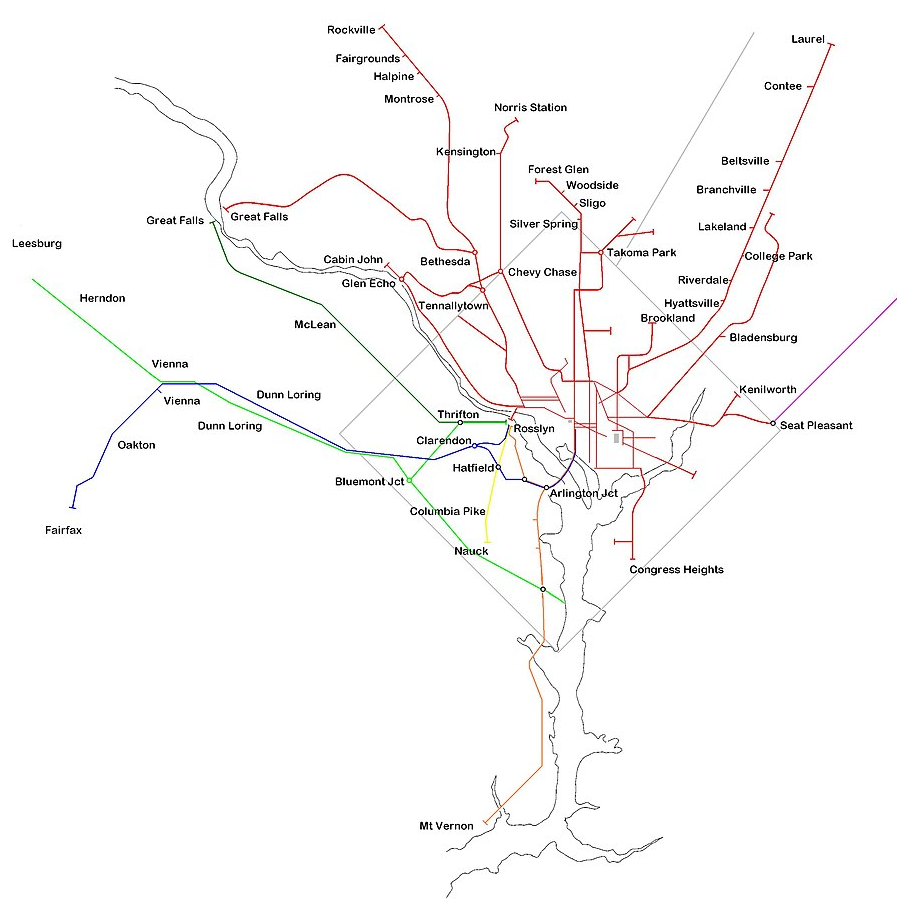

In Virginia, streetcars operated in Charlottesville, Danville, Fredericksburg, Lynchburg, Newport News, Norfolk, Northern Virginia (Alexandria to Fairfax), Portsmouth, Petersburg, Radford, Richmond, Roanoke/Vinton, Staunton, and Tazewell for six decades.

When Tazewell converted from mules/horses to electricity in 1904, it was "the smallest town in America with an electric street car." After the system closed in 1933, the town's streetcar ended up as a hotdog stand in Bland County. Richmond maintained an electrically-powered streetcar system for the longest period, starting the state's first in 1888 and being the last to close down in 1949. Its old streetcars were burned to facilitate salvage of the metal in them.2

Northern Virginia had an extensive network of streetcar lines

Orange = Washington, Arlington & Mount Vernon Electric Railway

Blue = Washington, Arlington & Falls Church Railway (WA&FC)

Yellow = Nauck (Fort Myer) line of WA&FC

Light green = W&OD Bluemont Division

Dark green = W&OD Great Falls Division

Source: Wikipedia, Northern Virginia trolleys

Source: NOVA History Remembered, Evans Autorailer and The Arlington & Fairfax Auto Railroad

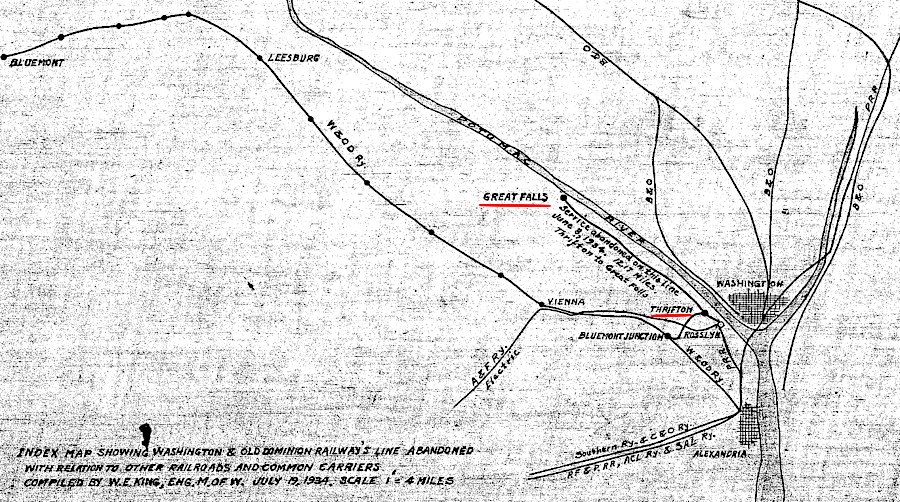

The Great Falls and Old Dominion Railroad was an electrified railway with passenger service from Georgetown to Great Falls starting in 1906. It became the Great Falls Division of the Washington & Old Dominion Railway (W&OD) in 1912. The connection to Great Falls closed in 1934, and Fairfax County used the old right-of-way to construct Old Dominion Drive.

the streetcar line from Thrifton Junction to Great Falls closed in 1935

Source: NOVA Parks, GF&OD Railroad 1916 ICC Valuation Map No. 3

Private streetcar companies in Virginia closed down as cars became affordable, and as operating costs of urban rail systems climbed faster than revenues. By 1950, the bus and the private car became the new ways to commute to work. As shopping centers were developed in the suburbs, retail stores moved away from the downtown core.

The cost and time to implement a new bus route to a new destination, such as Azalea Mall or Willow Lawn in Richmond, was far less than the cost and time to build a new rail line. General Motors and major tire/oil companies are often blamed for purchasing urban rail systems and closing them down, but Virginia's streetcar lines closed without getting involved in the supposed Great American Streetcar Scandal.3

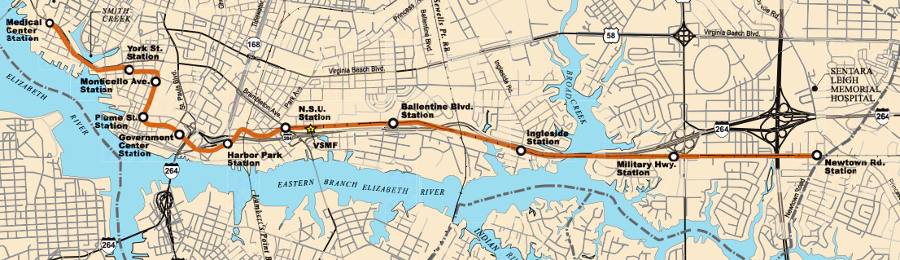

The gap in service before the modern revival of light rail in Virginia was six decades - the same length of time that electrically-powered streetcars operated, before Richmond shuttered its system in 1949. Light rail has been operational in Norfolk since 2011, when a 7.4-mile system called "The Tide" started operations. The construction costs were 150% of the estimates, making the project controversial. Initial operations attracted more customers than expected, but ridership declined as the newness faded.

To encourage more people to use the light rail system in Norfolk (and maintain popular support for extending the system), the Virginian-Pilot editorialized in 2014 that fares should be substantially reduced or eliminated. As the paper noted, a short light rail system limited to just downtown Norfolk would not eliminate commuter traffic or reduce congestion, and the system would be successful only if it triggered redevelopment along the route. More riders would equal more customers for businesses within 1/4 mile of the rail line; in theory, more riders on The Tide would spur new construction and remodeling of old buildings - so subsidizing transit customers would be in Norfolk's long-term economic interests.

A Cato Institute economist argued that the capacity of The Tide was inadequate to stimulate new growth in the area. As the Virginian-Pilot editorial writer noted, revenue from customers using The Tide was never expected to pay a high percentage of operating costs (and none of the capital costs to construct the light rail line). The economic benefits from the investment in transportation were projected to come from land use changes:4

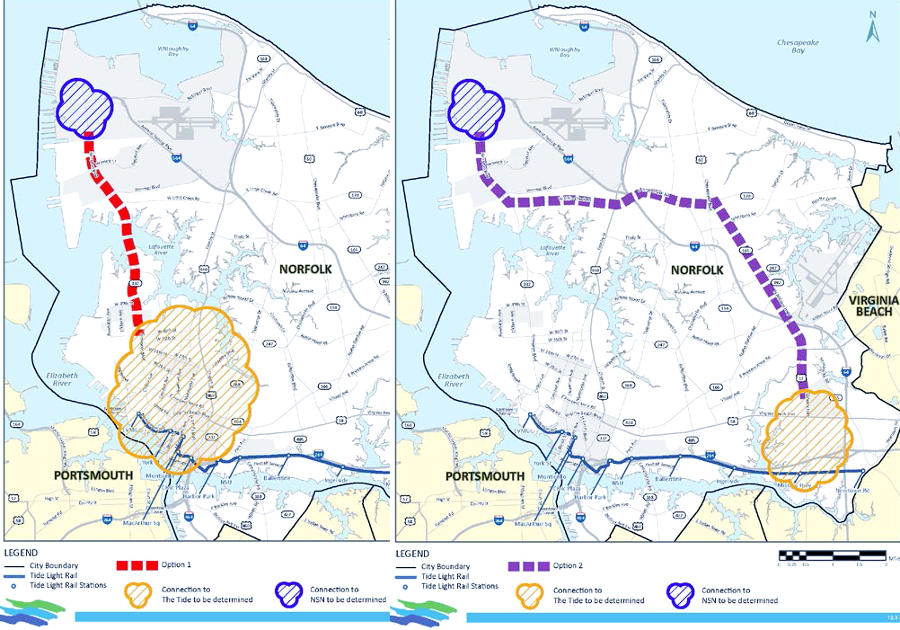

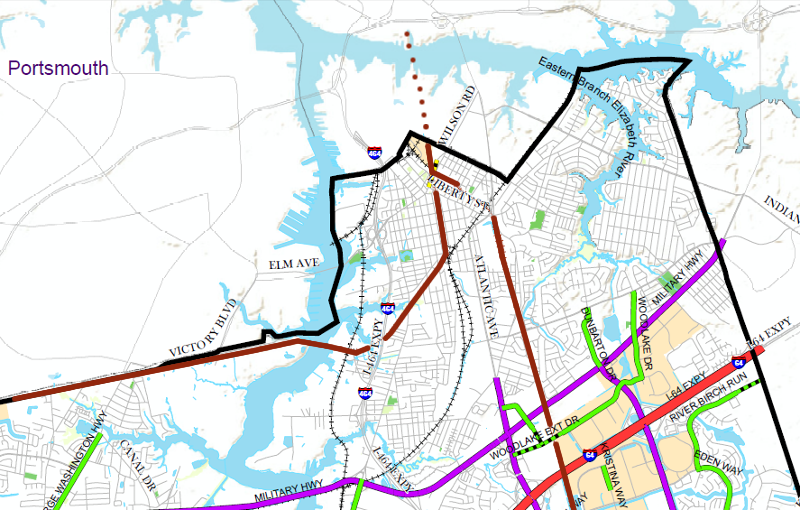

the initial 7.4 mile light rail system in Norfolk provides transit services downtown, with extensions proposed to the Norfolk Naval Station and to Town Center/Oceanfront in Virginia Beach

Source: Hampton Roads Transit, Norfolk Light Rail Transit Project - Final Environmental Impact Statement

Extensions northwest to the Norfolk Naval Station, and east into Virginia Beach, are under active consideration.

Hampton Roads Transit examined two main options for extending The Tide to Norfolk Naval Station

Source: Hampton Roads Transit, Public Meeting, June 15, 2017

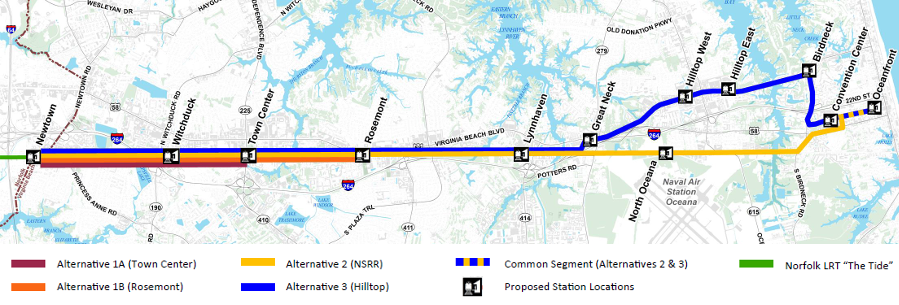

In 2010, anticipating future extension of "The Tide" as far as the Atlantic Ocean, Virginia Beach purchased the 10.6-mile right-of-way owned by Norfolk Southern railroad. The state provided 50% of the $40 million purchase price.

In 2012, city officials endorsed and 62% of the voters in Virginia Beach supported extending light rail from Norfolk into the city. That decision was in contrast to rejection of a light rail system in 1989 by city officials and by voters in a 1999 referendum. Those decisions killed plans for a joint Norfolk/Virginia Beach project and led to "The Tide" being built only to the Norfolk/Virginia Beach border, but the potential for extension was always clear.

In 2014, state officials committed to fund 50% of a proposed $290 million, three-mile transit extension to Town Center in Virginia Beach. City officials had consciously steered dense development to Town Center, creating a traffic nightmare in the short term but potentially growing into an urban downtown that would be less-dependent upon the automobile.

Like The Tide, the primary purpose of light rail in Virginia Beach was to stimulate transit-oriented development, not to improve the flow of traffic or streamline the commute to work. Virginia's Secretary of Transportation noted in 2015:5

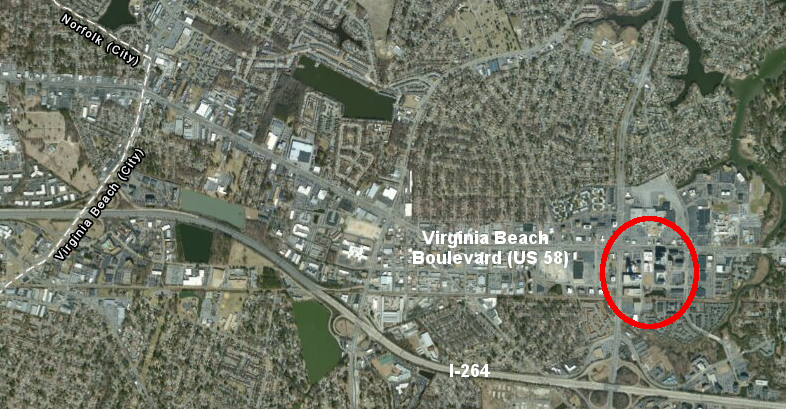

Virginia Beach is creating a downtown at the Town Center, and light rail is expected to spur additional dense development there

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

One commentator noted that a direct route to the Atlantic Ocean hotel/resort area could have avoided the jog north to Town Center, but "light rail bypassing Town Center would be urban planning malpractice." In addition, the state's commitment to support the extension required the city to postpone planning to build a line further eastward to the resort hotels at the oceanfront. A line east of Town Center would require building through streams and wetlands, while the stretch to Town Center involved fewer environmental complications.6

alternatives considered for the light rail extension from Norfolk into Virginia Beach included options beyond Town Center to the resort area at the Atlantic Ocean

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia Beach Transit Extension Study - Executive Summary (Figure ES.0-1)

Virginia Beach officials had considered using maglev technology rather than simply extending the light rail system, based on claims that a maglev system would be less expensive to build and operate compared to light rail. New maglev lines operating in Japan and China have demonstrated that the technology is feasible, and American Maglev Technology submitted a proposal to build a 12-mile transit system from the last station of "The Tide" in Newtown to the Atlantic Ocean.

The company offered to build a pilot line at company expense near the waterfront, to link the Virginia Beach Convention Center to the old site of the Dome. American Maglev Technology claimed its system, to be called "The Wave," would cost 2/3 less than building a 12-mile light rail system all the way to the resort area.7

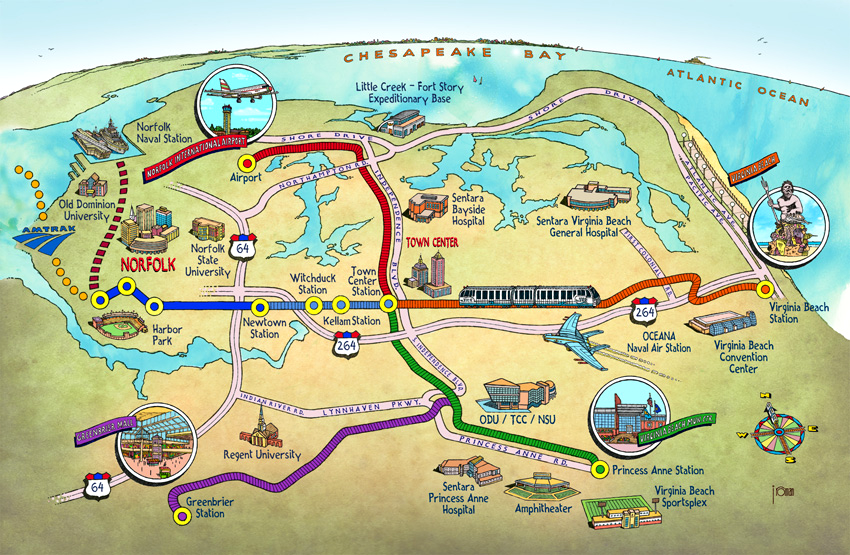

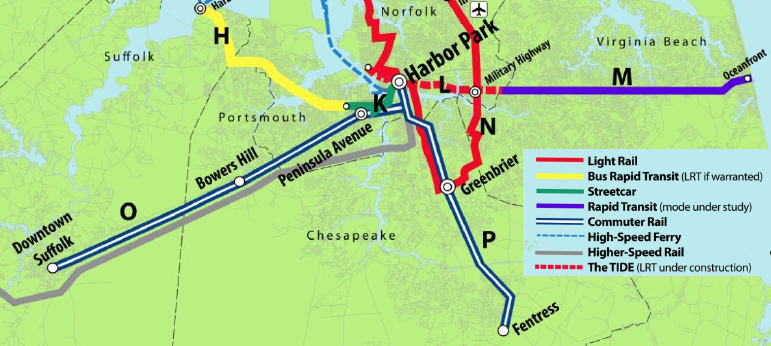

light rail extensions beyond "The Tide" are part of a long-range regional transit plan that could require customers to shift modes from light rail, ferry, high-speed rail, streetcars, and potentially even a maglev system

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation "Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan," Short-Term Implementation Recommendations (By 2025) (Figure ES-1)

American Maglev had built an elevated guideway in 2001 at Old Dominion University to demonstrate maglev technology.

However, the $16 million technology demonstration was a failure; the cars never moved at the planned 40 miles per hour speed. The Federal government stopped supporting the project, and the university chose to demolish the three stations and cannibalize the track as scrap in 2010 to fund continued research. The overhead monorail track lasted until 2023, becoming a campus landmark that sheltered students in rainstorms as a "million-dollar umbrella" before being removed to permit construction of a biology building.

The $16 million project had included a $7 million loan to the company from the state. In 2003 the long-term vision involved building the Baltimore-Washington Superconducting Magnetic Levitation (SCMAGLEV) line, and also building a $60 million project to haul cargo containers from the Port of Virginia. In 2014 the company was still hoping private funders would finance the Virginia Beach project, allowing repayment of the $7 million loan.

The state was willing to fund a light rail extension from Norfolk to Virginia Beach, but by 2014 was no longer willing to invest any money in the alternative technology of maglev because of the failed test at Old Dominion University. In order to obtain the state commitment for 50% of the $290 million required to link "The Tide" to Town Center, Virginia Beach officials agreed to stop negotiating public-private proposals (including the maglev proposal) and committed to competitive bidding.

That essentially killed the maglev option for extending "The Tide" from the Norfolk boundary to Town Center, and Virginia gave up on the possibility of getting a discount price for being the first demonstration site. American Maglev Technology refocused on building a system in Orlando, then a Washington-Baltimore line where trains would move at 311 miles per hour. The Federal government opposed the Baltimore-Washington Superconducting Magnetic Levitation (SCMAGLEV) project and killed it in 2025.

The demonstration project at Old Dominion University ended up demonstrating that maglev was not a cost-effective technology yet. In 2023, the university began planning removal of the remainder of the maglev line in order to construct a new biology building.

Nonetheless, in 2015 the city updated plans to build a light rail system to Town Center. Costs increased to $310 million, and the state committed providing $155 million (plus up to $30 million more in loans). Virginia Beach still kept open the possibility of building further east from Town Center to the resort area on the Oceanfront, and even the opinion of using a maglev line on that segment. The potential eastward extension to the transit system was projected to cost $1.3 billion.8

By 2016, a 3.5-mile extension from Norfolk to Town Center, with three new stations, was projected to cost $243 million. In a referendum that year, Virginia Beach voters rejected by 57-43% the proposal to fund that extension of The Tide to Town Center. In 1999, the vote had been 56% against funding, but public opinion shifted by 2012 when 62% had supported an extension.

The 2012 vote re-started serious planning, and in 2015 the City Council in Virginia Beach passed a 1.8-cent real estate tax increase with the funds dedicated to pay for light rail. An advocacy group in favor of a network of light rail lines made clear in the 2016 referendum vote that a regional transit system was anticipated:9

plans for an interconnected light rail system extended from the Oceanfront of Virginia Beach to Greenbriar in the City of Chesapeake - until Virginia Beach voters rejected funding in 2016

Source: Virginia Beach Connex

After the 2016 vote, the state made clear that the extension was dead and withdrew its commitment to provide $155 million. The state also indicated the city had to reimburse the $20 million provided earlier to purchase the railroad right-of-way.9

In 1996, the City of Chesapeake city council voted in favor of a light rail system. Voters supported it in a 2000 referendum, but no funding was available. The city council declined to provide even partial funding for a light rail study in 2010.

In 2014, after "The Tide" successfully attracted riders and the 2013 General Assembly had approved new taxes to fund transportation projects in Hampton Roads, the Chesapeake city council reconsidered and asked the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization to study how to bring light rail to Chesapeake.

the City of Chesapeake connection to "The Tide" light rail at Harbor Park in Norfolk (brown line) will require crossing the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River

Source: City of Chesapeake, 2050 Master Transportation Plan

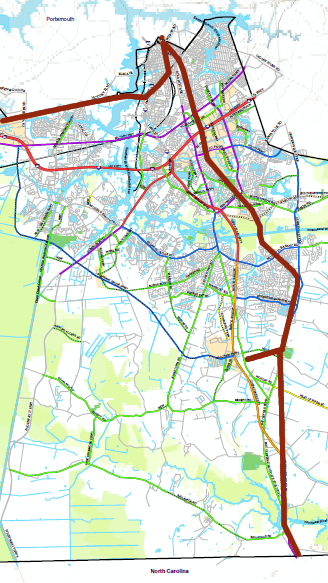

Chesapeake's long-range plan is to extend light rail from its northern border with the City of Norfolk south through its Urban, Suburban, and Rural areas to the North Carolina border. The city plans for light rail to move commuters from North Carolina to urban job centers, as well as to spur transit-oriented development in the 70 acres next to Dollar Tree headquarters that were planned for urban-level density.

The 2011 Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan proposed building a commuter rail system rather than light rail south of Greenbrier. That proposed commuter rail line would extend from Harbor Park south to Fentress, but the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation left open the possibility of future expansion into North Carolina.

Another alternative to light rail is Bus Rapid Transit (BRT). BRT systems are designed to mimic rail systems, using dedicated lanes for buses to bypass other vehicles trapped in congested traffic.

Though different types of transit were proposed in different long-range land use and transportation plans, the various documents made clear where the state/city proposed to invest in transportation infrastructure over the next 20-40 years, allowing developers to propose projects based on the potential of new transit services.10

in the 2011 Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan, the long-range vision for Chesapeake included extending light rail in Corridor N between Harbor Park-Greenbrier, then build commuter rail in Corridor P between Harbor Park-Fentress

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation "Hampton Roads Regional Transit Vision Plan," Overall Regional Transit Vision Plan (Figure ES-4)

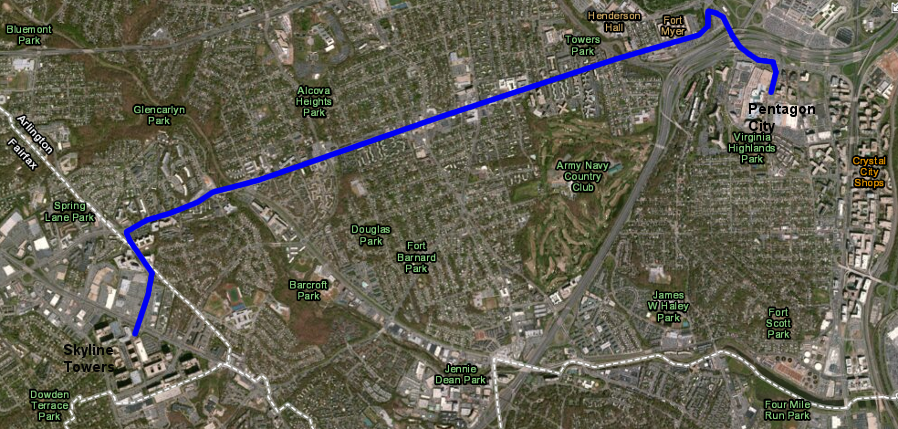

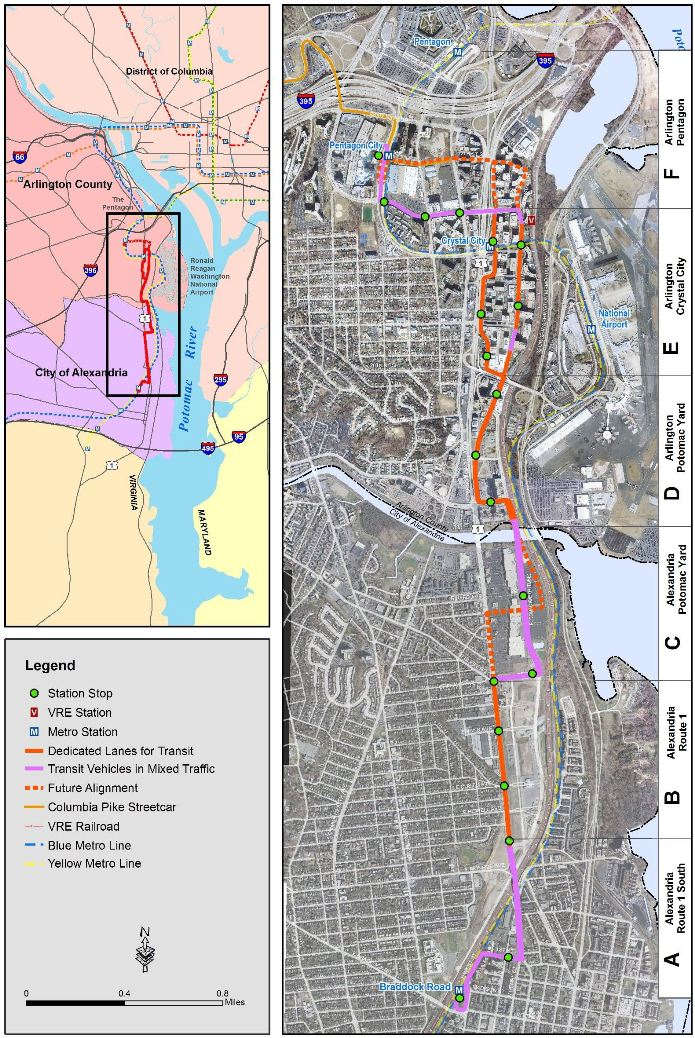

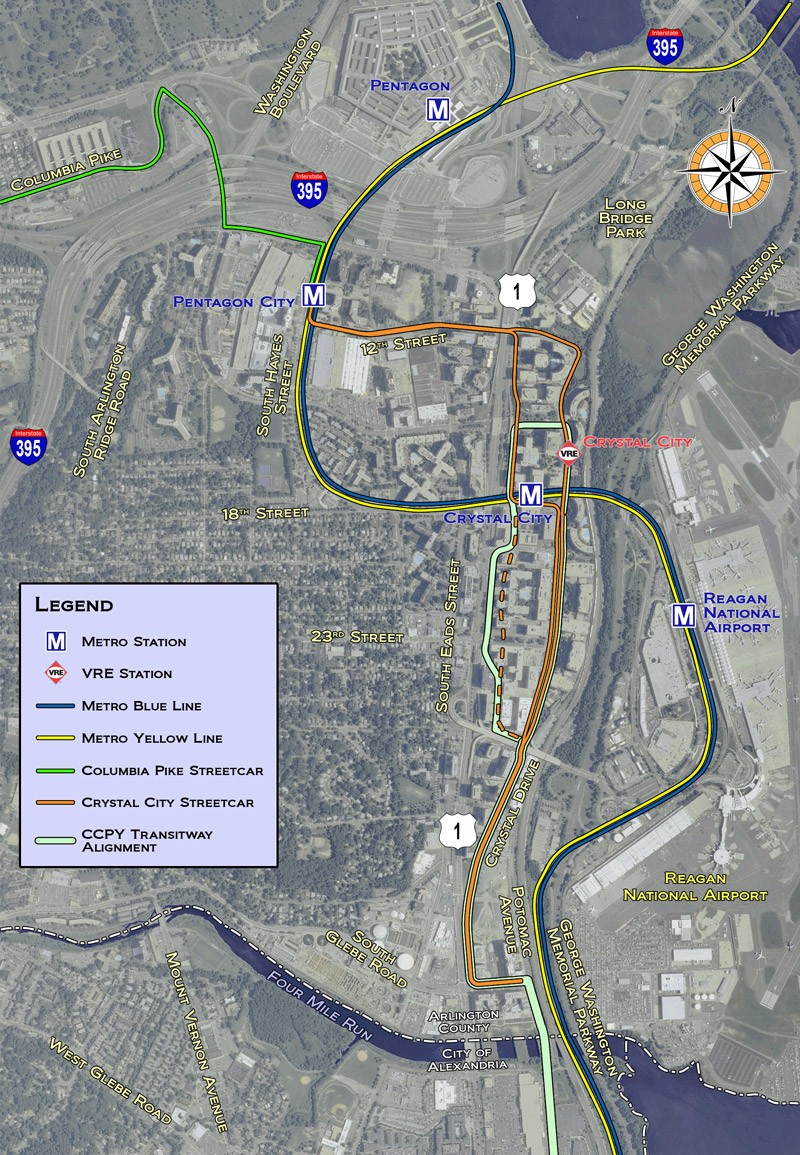

Arlington and Fairfax counties in Northern Virginia cooperated to propose a light rail project for five miles along Columbia Pike to link Skyline Towers at Bailey's Crossroads (in Fairfax County) to the Pentagon City Metro station (in Arlington County). The separate Crystal City project in just Arlington County would have built an extension through Crystal City, past Reagan National Airport to Potomac Yard/Glebe Road. Both "streetcar" projects required overhead power lines.

The routes of the Columbia Pike and Crystal City streetcar lines were chosen to maximize land use benefits, more than to reduce congestion - though with 17,000 passengers traveling in one direction or the other each day, Columbia Pike had the busiest bus route in Virginia.

Buses were consistently crowded and local population was projected to grow 20% in the next decade after the streetcar project was proposed, so it was clear that transportation demand would exceed the capacity of the existing bus-based transit system.11

Though a streetcar might improve transit, so could enhanced bus capacity. The primary goal of the Columbia Pike and Crystal City streetcar lines was to trigger redevelopment. After land use changed along the corridor, property and other taxes were projected to increase sufficiently to justify the public investment.12

An Arlington County consultant predicted that the Columbia Pike streetcar would spur private landowners to finance upgrades and construct new buildings, just as Metrorail triggered redevelopment for decades after the 1970's. In 30 years, estimated costs of $450 million for the Columbia Pike streetcar ($250 million for initial construction, $200 million more for operations) would be offset by a projected increase in tax revenues of $455 million-$1.5 billion.13

as proposed, light rail through Crystal City would have designated travel lanes and occasionally share the streets with cars/buses in mixed traffic lanes

Source: Crystal City Streetcar, October 2013 Newsletter

The first stage in construction of the Crystal City line required building dedicated lanes for buses. The 4.5 mile Crystal City Potomac Yard Transitway, marketed initially as the "Metroway" with lighter-tinted pavement and distinctive blue glass shelters, provided a bus rapid transit (BRT) link between the Braddock Road-Crystal City Metrorail stations. (The City of Alexandria planned to add an additional transit connection, agreeing to build dedicated bus lanes between the planned Glebe Road streetcar station in Arlington and the Braddock Road Metrorail station in Alexandria.)

The Crystal City Streetcar was proposed as another link, connecting the Crystal City-Pentagon City Metrorail stations on the surface. Passengers interested in traveling between the Glebe Road-Pentagon City Metrorail stations would have an alternative to Metro, but passengers would have to switch at Glebe Road from bus to streetcar.

Such "mode shifts" are inconvenient, and traffic engineers recognize that many passengers would rather drive a car between two points than wait at a transit station midway in a trip. Travelers in the Crystal City Potomac Yard Transitway will have an unusual set of transit choices, however - passengers going between the Braddock Road-Crystal City Metrorail stations could take the Metro train instead, offering a direct transit connection without a mode shift.

The Crystal City Potomac Yard Transitway required nearly $40 million to create new lanes for buses, but for some stretches the buses are mixed in with regular traffic and in other stretches cars will be banned from regular lanes so buses get priority. Drivers in cars may object to losing some access, but transportation planners viewed the busway as a quick solution, and in the case of Arlington a fast start towards the ultimate light rail:14

The proposed Columbia Pike line would have cost over $300 million, but improved bus service was projected to cost just 25% of that amount. That dramatic cost difference triggered extensive public debate over whether a lower-cost bus system would be perceived as persistent enough to trigger the "BRT effect" among landowners. All transit projects large enough to affect land use patterns over the next 10-30 years involve substantial expense. Advocates for the Columbia Pike streetcar noted that Phase 1 of the Silver Line Metrorail expansion cost 800% more than the proposed Columbia Pike project, but will move only 230% more people.15

The Columbia Pike line was also controversial because the first bus stop that was planned to serve until the streetcar became operational cost $900,000 to build. There were 24 stations planned, with heated concrete floors but with a shelter design that did not provide protection from the rain or sun. The "million dollar bus stops" were redesigned a year later, to reduce costs by 40% and to provide more shelter from rain/sun.16

In an April 2014 special election, an Independent/Republican opponent of light rail became the first non-Democrat elected to the Arlington Board since 1999. The winner campaigned primarily on the cost of rail vs. bus service, and clearly struck a chord among voters.

The defeated Democrat ran again in the November 24 regular election, and limited his support for the Columbia Pike streetcar. He called for a public referendum on the issue and agreed to follow public opinion, though his personal advocacy of the new transit system was still clear:17

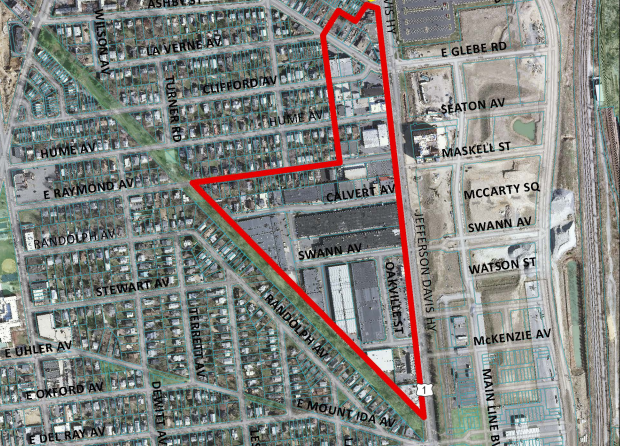

after the Crystal City Potomac Yard Transitway along Jefferson Davis Highway was funded, owners of the 13-acre Oakville Triangle initiated planning to convert the industrial area into a mixed-use project with retail shops on the ground floor, topped by residential units and a hotel

Source: City of Alexandria, Aerial showing the Oakville Triangle and Route 1 Corridor Study proposed boundary

the light-rail Columbia Pike transit project was projected to result in lower development densities than what the heavy rail Orange Line triggered in Rosslyn-Ballston corridor

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In May 2014, after the special election won by the opponent of the Columbia Pike streetcar, Arlington County announced that the projected cost of the streetcar line had increased to $358 million. That was $100 million above the initial estimate, made two years earlier. In between the two estimates, the Federal government cited projected cost as a major reason for rejecting Arlington's request for funding from the Small Starts grant program. The Federal government had estimated the project would cost $310 million, exceeding the limit of the grant program ($250 million).18

In July, 2014, the price was fixed at $333 million. It dropped because the state of Virginia agreed to provide $65 million more in financial support, which eliminated the need for Federal funding. Avoiding the delays in the Federal grant process would speed up construction by a year, thus eliminating $25 million of costs due to reduced time for inflation. It also facilitated an irrevocable commitment of funds to build the streetcar, before the slim majority on the County Board supporting light rail could be altered in the November 2015 election.

A preliminary engineering contract worth $26 million was approved by a 3-2 vote in September 2014. However, the anti-streetcar Independent/Republican candidate was re-elected in November, 2014, in an election where the majority of voters split their tickets to vote for Democratic candidates running for other offices. The extent of local opposition to light-rail on Columbia Pike was clear.

Less than two weeks after the election, the Arlington Board decided to abandon plans for both the Columbia Pike and Crystal City streetcar line. Fairfax County officials were frustrated at the unilateral decision, leaving the Skyline Towers complex without rail transit services again. (Plans to build Metrorail to Skyline Towers had been abandoned in the 1970's.)19

One commentator very familiar with the link between transportation and land use, James Bacon, suggested a way to resolve the dispute over whether the public investment in the Columbia Pike streetcar would repay its cost through increased economic activity and higher tax revenues. His proposal: transfer the risk. Instead of having Arlington County taxpayers finance the light rail project, create a special tax district, sell revenue bonds to fund construction, and have the property owners pay an extra tax for the length of time (20-30 years) required to repay the bonds.

Under that scenario, property owners near the light rail stations, who were expected to benefit from the increased transit services, would pay more than property owners nearby - but Arlington landowners outside the tax district would pay no extra taxes to fund the streetcar project. Purchasers of the bonds, not residents of Arlington County, would make a profit if the extra tax revenues triggered by redevelopment matched projections Otherwise, if extra tax revenues were not high enough to repay costs plus interest for building the Columbia Pike streetcar, the bondholders rather than Arlington County taxpayers would suffer financially.20

the Crystal City Potomac Yard Transitway was designed to parallel the Metrorail route, so the additional transit services would spur additional development in Alexandria/Arlington

Source: Crystal City/Potomac Yard Transit Improvements, Crystal City-Potomac Yard Transitway Sections

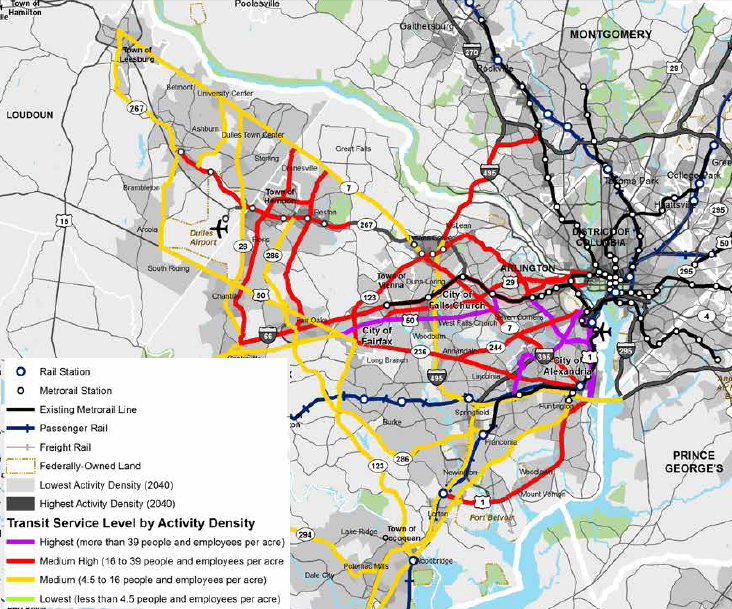

Additional light rail projects may be constructed in Northern Virginia.

The Northern Virginia Transportation Authority's Transaction 2014 long-range plan proposed $1.5 billion to construct a light rail line on Route 28 from Manassas to Dulles Airport - as much as the proposed extension of the Blue Line to Potomac Mills. That was more than the $1.2 billion proposed to extend the Orange Line to Gainesville, or the $1.2 billion proposed to build a new Blue Line Metrorail tunnel into Georgetown with 9 new stations.

by the year 2040, the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation predicted "Medium High" population density (16-39 people/employees per acre) would justify light rail or Bus Rapid Transit service between Alexandria-Woodbridge - but not heavy rail such as Metrorail

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation - Super NoVa Transit/TDM Vision Plan, Subregional Corridor Demographic Analysis (Figure 5.5)

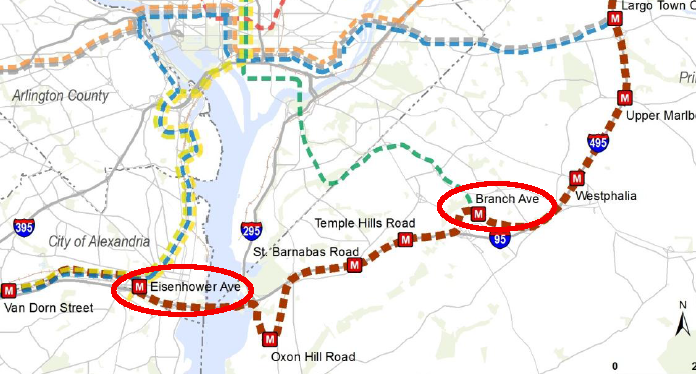

Transaction 2014 also proposed $500 million to build rail transit on Route 7 from Tysons Corner to Baileys Crossroads (extending the Columbia Pike streetcar), another $500 million to build a light rail connection over the Woodrow Wilson Bridge to connect the Eisenhower Avenue station in Alexandria with the Branch Avenue Metrorail station in Prince Georges County, and $1.1 billion to link Bethesda to Fairfax Hospital via Dunn Loring.21

a light rail link between Alexandria and southern Maryland could also be developed as a heavy rail route, part of the proposed Brown Line for Metrorail

Source: Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (Metro) - Regional Transit System Plan (RTSP)Summary of Projects, Plans, and Strategies Analyzed As Part of the RTSP

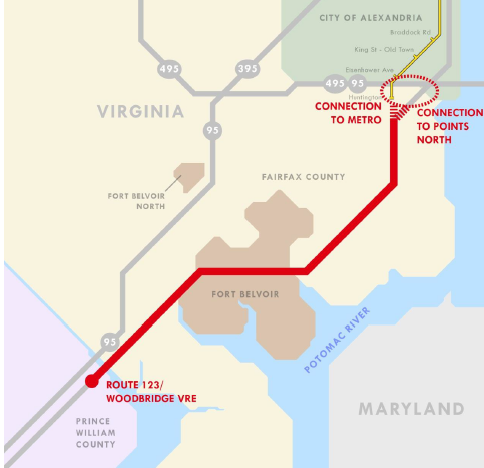

A Multimodal Alternatives Analysis on Route 1 in Northern Virginia, from the Capital Beltway (I-495/I-95) for 15 miles south to Woodbridge in Prince William County, considered light rail in the highway median strip as one transit option. In a public meeting in 2014, the local representative to the House of Delegates and the local county supervisor expressed different technology preferences.

The member of the Board of County Supervisors noted that light rail in the Route 1 corridor was feasible, but dreams of extending the Yellow Line of Metrorail south to Fort Belvoir were not cost-effective because the population density was not sufficient to generate enough ridership to justify the investment. In contrast, the local delegate advocated the "heavy rail" option:22

A Letter to the Editor of the Mount Vernon Gazette from an architect made clear that the heavy rail option was desired by some advocates because Metrorail would be more effective that light rail or buses at stimulating dense urban growth in the area. Heavy rail could also transport more passengers than a light rail or bus system, but that was a secondary factor:23

new transit options on Route 1 in southeastern Fairfax County include light rail

Source: Route 1 Multimodal Alternatives Analysis, Powerpoint slides from Public Meeting #1 (October 9, 2013)

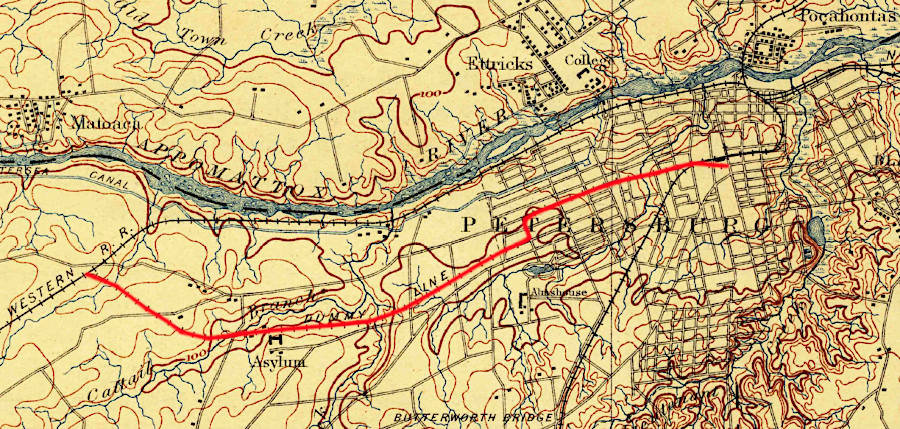

the Dummy Line in Petersburg was named after the electric "dummy" locomotives that pulled primarily passenger cars to/from Central State Hospital

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Petersburg VA 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1894)

the City of Chesapeake has proposed extending light rail (brown line) beyond its planned Urban area, through its Suburban and Rural areas all the way to the North Carolina border

Source: City of Chesapeake, 2050 Master Transportation Plan

the Columbia Pike light rail system was designed to be extended through Crystal City, linking mixed-use developments between the Pentagon City Metrorail station and Glebe Road

Source: Crystal City Streetcar Project, Streetcar Route Map

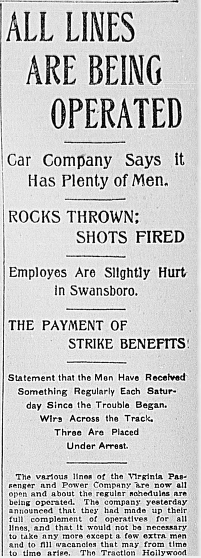

the Virginia Passenger and Power Company in Richmond broke a strike by streetcar employees in 1903

Source: Library of Congress - "Chronicling America - Historic American Newspapers," The Richmond Times Dispatch (July 28, 1903)

on light rail systems such as The Tide in Norfolk, trains run at slower speeds than on heavy rail systems such as Metrorail in Northern Virginia

Source: Super NoVa Transit & TDM Vision Plan Study, Transit Mode Characteristics (Table 5.1)

in 1906, the Norfolk Portsmouth Traction Company operated on Main Street in Norfolk; "The Tide" is not the first trolley or light rail system there

Source: Library of Congress, View of Main Street, Norfolk, Va. (1906)

in 1890, Roanoke developers proposed electric street railways to connect new subdivisions to the city center

Source: New York Public Library, Map of Roanoke, Virginia (by George William Baist, 1890)