Long Bridge is used by CSX, Amtrak, and Virginia Railway Express trains

Source: Long Bridge Project, Combined Final Environmental Impact Statement/Record of Decision and Final Section 4(f) Evaluation (cover)

Long Bridge is used by CSX, Amtrak, and Virginia Railway Express trains

Source: Long Bridge Project, Combined Final Environmental Impact Statement/Record of Decision and Final Section 4(f) Evaluation (cover)

The first bridge across the Potomac River at Washington was a toll bridge for pedestrians and wagons. It was completed in 1797 at Pimmit Run near Little Falls. Georgetown merchants funded the Falls Bridge, which was later rebuilt and called the Chain Bridge, to intercept traffic coming from the Shenandoah Valley and compete with Alexandria.1

The second bridge was authorized by the US Congress in 1808. The creation of the new national capital in 1800 had increased traffic enough to justify private investors building another toll bridge downstream from the "Falls Bridge." In addition, a causeway from the Virginia shoreline to Analostan Island blocked traffic through the channel on the Virginia side after 1805.

Georgetown merchants opposed authorization of the new bridge, fearing it would encourage development of the rival "Washington City" within the District of Columbia. They also feared the new bridge would interfere with shipping traffic to the port at Georgetown, even though swing spans were included so the Potomac River shipping channel could be used.

The Alexandria and Washington Turnpike opened its bridge in 1809, with a drawbridge on one end to allow ships to reach Georgetown upstream. At the time, the structure was thought to be the longest bridge in the world. It allowed wagons to reach the new city of Washington, DC without having to use the causeway to Analostan Island and then the Mason family's ferry to Georgetown. That ferry was started by George Mason IV in 1748, and replaced one started in 1738 from Francis Awbrey's land a half mile downstream. The ferry operated until 1867, despite competition from the Long Bridge and the Aqueduct Bridge which opened in 1843.

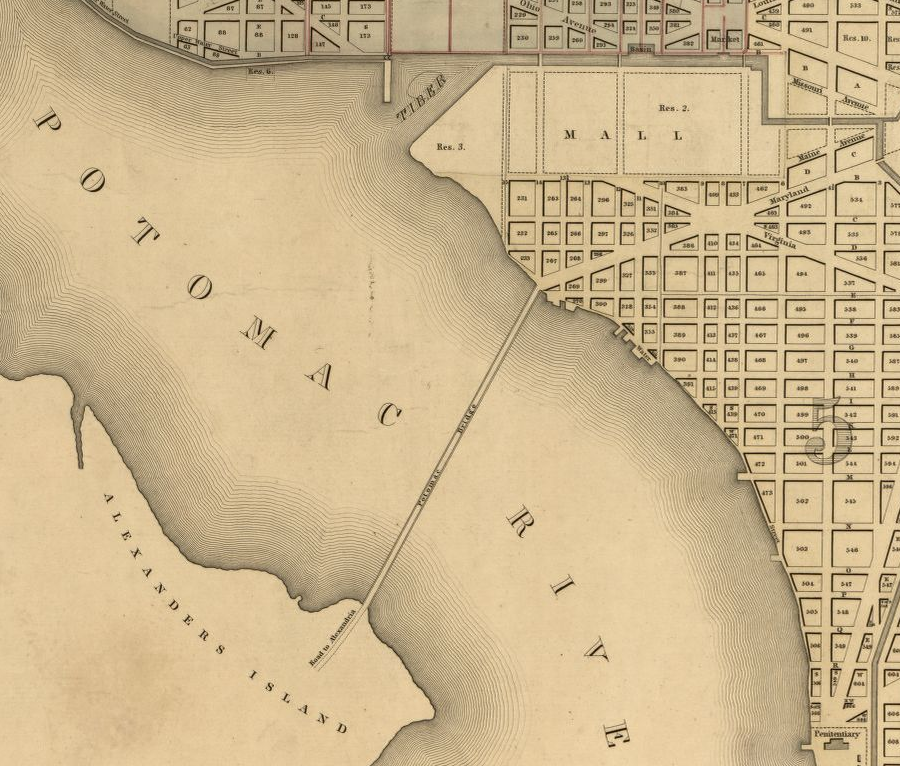

the Alexandria and Washington Turnpike completed a new 5,000-foot Long Bridge across the Potomac River in 1809

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Holmes Island and the adjoining upland: the property of R. B. Mason Esq

The 1809 bridge was burned when the British army captured Washington in 1814. The replacement bridge which opened in 1816 lasted 15 years before it was washed away by floodwaters and ice in February, 1829.

The private investors lacked the capital required to rebuild, and chose instead to sell their franchise to the Federal government in 1832. During President Andrew Jackson's second term, the US Congress approved a proposal for a bridge crossing the Potomac River, which would provide access between the two segments of the District of Columbia originally donated by Virginia and Maryland.

Alexandria County, with the new "Jackson City" development, was on the southern bank. The rest of the District of Columbia was on the northern bank, including Georgetown, Washington City, and Washington County.

What was called the "Potomac Bridge" opened in 1835. President Andrew Jackson led the ceremonies, walking across the bridge to Virginia and then riding back in a carriage.

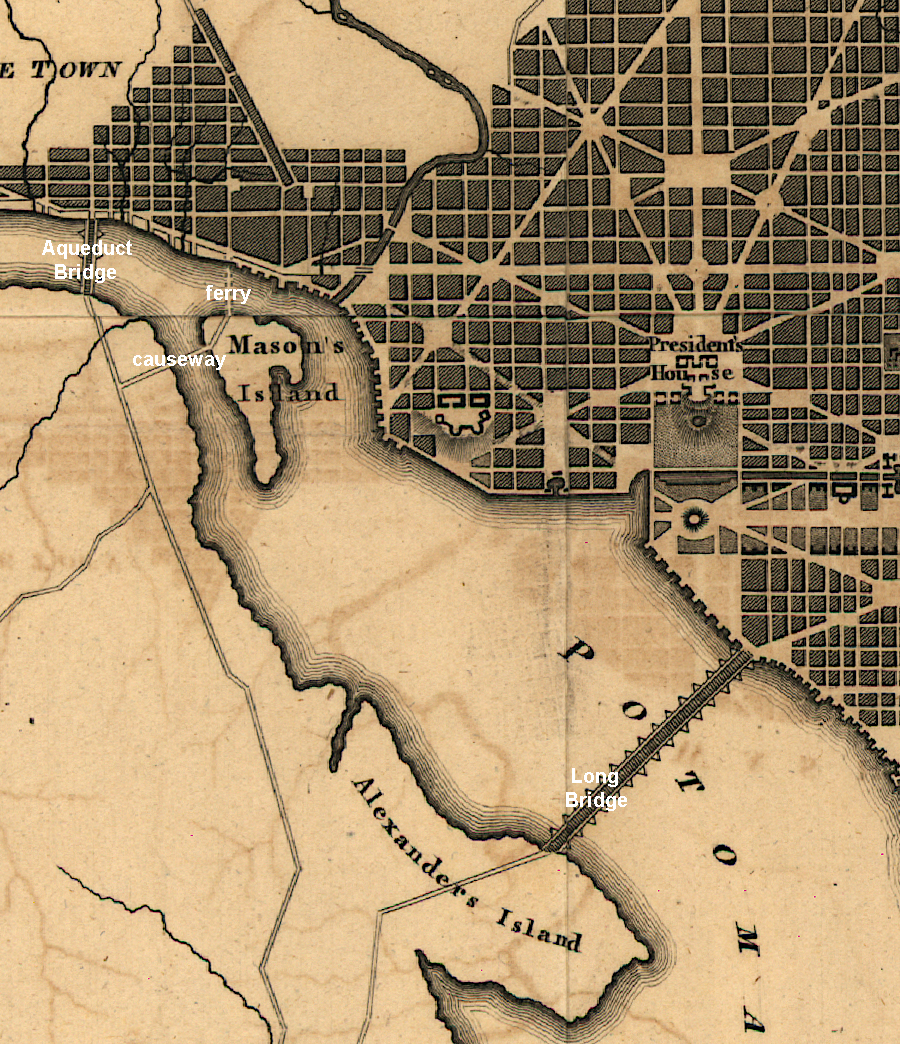

the Potomac Bridge was built by the Federal government and opened in 1835

Source: Library of Congress, Map of the city of Washington in the District of Columbia: established as the permanent seat of the government of the United States of America (1839)

The southern end at Jackson City became part of Virginia in 1847, when the land contributed by that state to create the District of Columbia in 1800 was retroceded back to Virginia. The Potomac Bridge became know as the "Long Bridge." It was longer than the Chain Bridge upstream near Little Falls.2

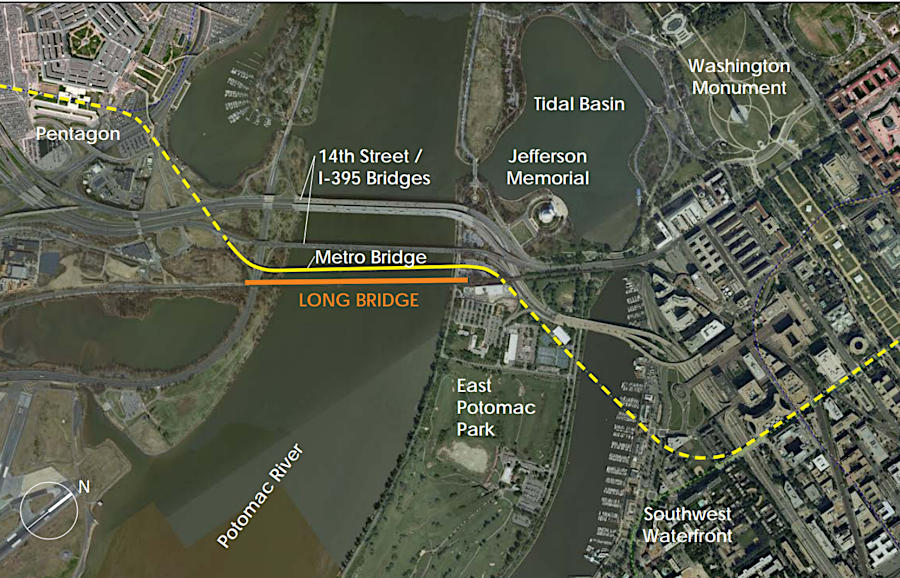

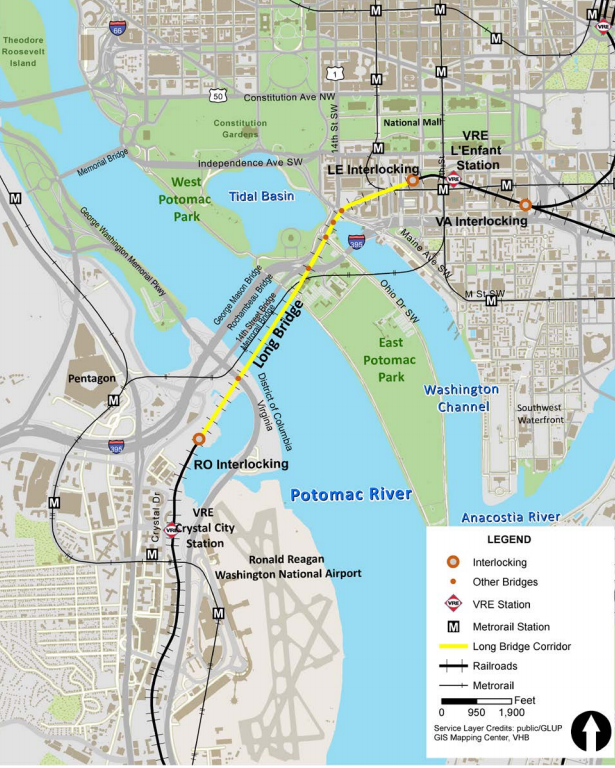

Long Bridge is the only railroad bridge that crosses the Potomac River downstream of Harper's Ferry

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Alexandria and Washington Railroad built track from Alexandria on the south bank of the Potomac River, going upstream to the south end of Long Bridge. At the north end within the District of Columbia, the Alexandria and Washington Railroad laid track from Long Bridge to a connection with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

No tracks were placed on Long Bridge itself; it was too narrow and not strong enough to support the heavy locomotives or loaded cars. The Alexandria and Washington Railroad had to unload cargo/passengers, haul them by wagon/stagecoach across the Potomac River, and reload on the other side. Requests by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad for authorization to build its own bridge were ignored by the US Congress, in part because the Pennsylvania Railroad lobbied against its rival.

at the start of the Civil War, Long Bridge, Aqueduct Bridge, and Chain Bridge crossed the Potomac River along with a causeway/ferry at Mason's Island

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of the city of Washington and territory of Columbia (by William Home Lizars)

Alexandria was occupied by the Union Army on May 24, 1861, and the Alexandria & Washington Railroad was seized. The owner, James French, was a Confederate sympathizer who fled south to avoid the Union occupation.

The Union army then pulled up the rails of the Alexandria & Washington Railroad and made its bed into a wagon road. In early 1862, however, the need for more-efficient delivery of supplies had increased. The US Military Railroad re-laid the tracks, and rails were finally placed on Long Bridge.

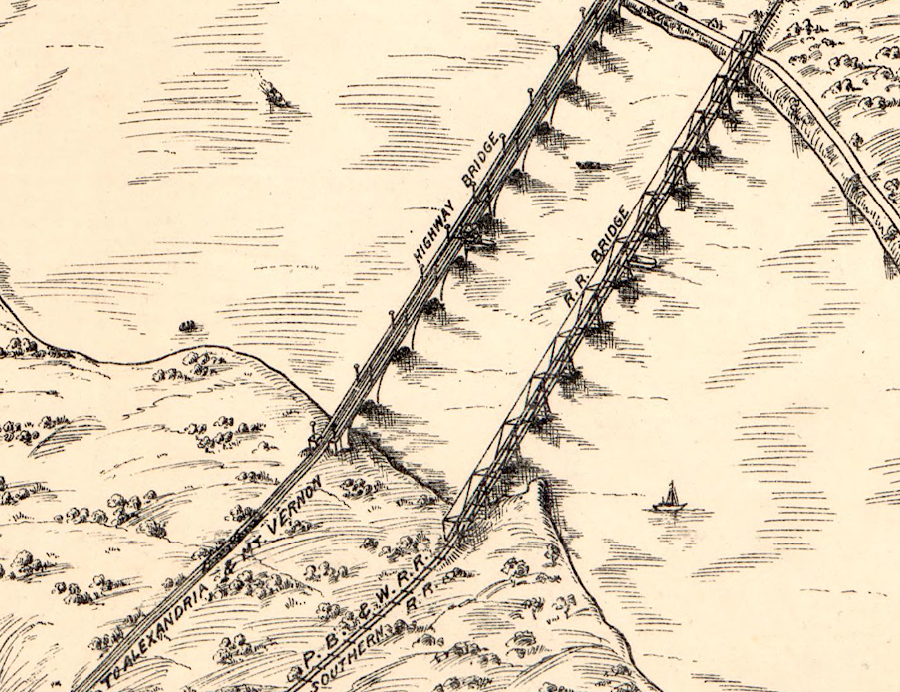

Because the wooden structure could not handle heavy loads, horses rather than locomotives were used to pull loaded rail cars across the bridge. In 1863, the Federal government quickly built a bridge parallel to the 1835 bridge. The 1863 bridge was strong enough to support US Military Railroad locomotives, and was dedicated to just rail traffic. Until then, the closest railroad bridge across the Potomac River was at Harper's Ferry.3

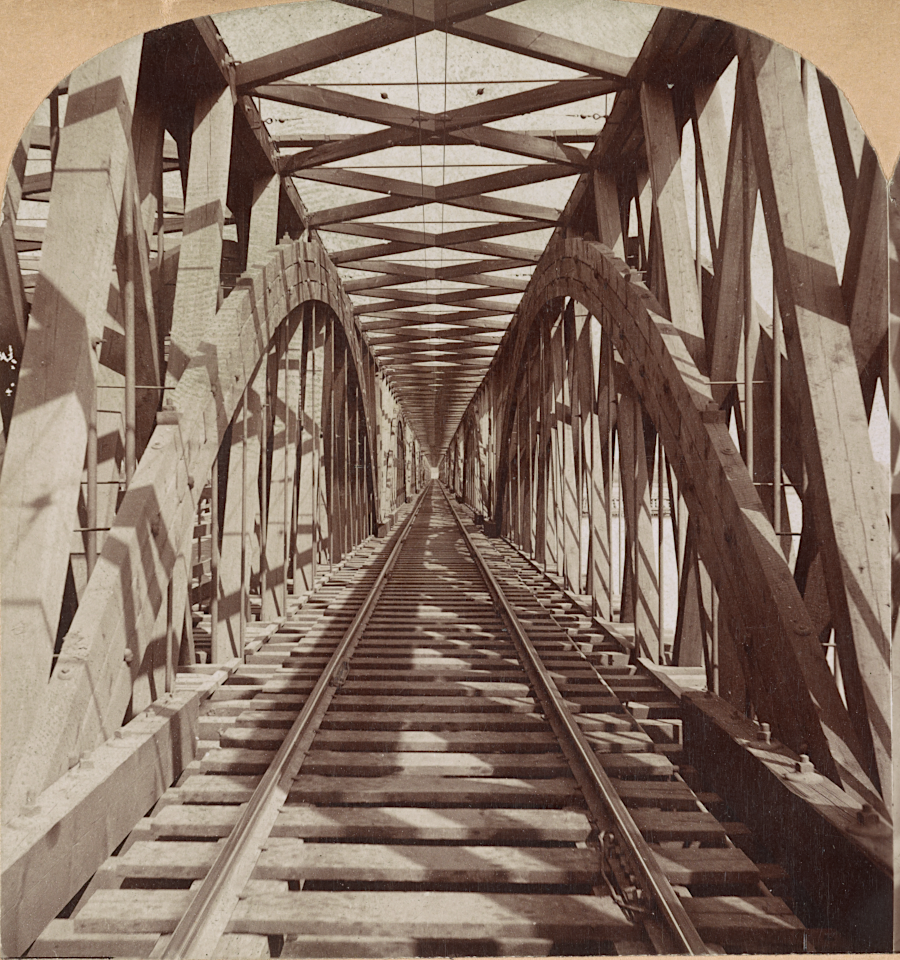

a railroad span was built in 1863, parallel to the Long Bridge which could not support heavy locomotives

Source: Library of Congress, Long Bridge, Washington, D.C.

the 1863 railroad bridge was guarded by Union soldiers

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Long Bridge Study (p.2)

In 1865, the Federal government leased the 1863 railroad bridge to the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad and the rail tracks were removed from Long Bridge. After the Civil War, with its control of the Alexandria & Washington Railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the only provider of railroad service going south of the national capital.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad could run trains through Washington, go south across the Potomac River via the Long Bridge, and then travel to Alexandria via the Alexandria & Washington Railroad. Further south, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad controlled the Orange & Alexandria, Manassas Gap, and the Lynchburg & Danville railroads. After the Civil War, the rail network of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad extended almost to the North Carolina border.

during the Civil War, Long Bridge could not support heavy locomotives

Source: Library of Congress, Long Bridge, Washington, D.C.

the 1863 railroad bridge paralleled the existing 1835 Long Bridge

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Washington D.C. and vicinity

The rival Pennsylvania Railroad managed to get its own track built from Baltimore into Washington, DC in 1870. It used the charter of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad to build a "branch line" into the District, finally breaking the monopoly of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The Baltimore and Potomac Railroad built its own depot in Washington, DC and extended track to Long Bridge. In 1870, with the help of influential politicians in the US Congress, the Pennsylvania Railroad also gained perpetual rights to use Long Bridge across the Potomac River so long as the structure completed in 1835 was keep in good repair.

In 1872, the Pennsylvania Railroad (technically the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad) shifted the tracks from the 1863 railroad bridge to a rebuilt Long Bridge. The 1863 railroad bridge was removed, and all traffic - trains, wagons, and pedestrians - shared the Long Bridge. Track was placed on the upstream side of Long Bridge, and all other traffic crossed the Potomac River using the downstream side of the bridge.

Long Bridge remained a drawbridge. All traffic across it stopped when spans were opened as much as 20 times a day to allow ships to reach Georgetown.

The 1835 version of the Long Bridge had not been able to support heavy locomotives, which is why the Federal government built a special railroad bridge in 1863. The reinforced 1872 version of Long Bridge could handle train traffic, after the railroad piled rip-rap around the sandstone pillars and wooden pilings supporting the wooden superstructure. The 1863 railroad bridge was removed because it limited the flow of water and ice in the winter, but the extra rip-rap on the reinforced Long Bridge offset those benefits.4

Acquiring control of Long Bridge was part of the Pennsylvania Railroad's strategy to expand into the southern states after the Civil War. Northern capitalists could acquire control over businesses in the southern states at low cost after the defeat of the Confederacy. The Pennsylvania Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad expanded their rivalry into efforts to control the railroad network in Virginia.

Around the same time the Pennsylvania Railroad gained control of Long Bridge, it also gained control of the Alexandria & Washington Railroad in the District of Columbia. "Boss" Shepherd, the head of the District of Columbia Board of Public Works, demanded that the Alexandria & Washington Railroad's at-grade crossings be eliminated. The Pennsylvania Railroad could have built expensive bridges over the roads, but it chose to completely remove the Alexandria & Washington Railroad tracks within the District of Columbia.

The Pennsylvania Railroad retained access to Long Bridge, using the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad tracks. However, the track removal eliminated the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's connection through Washington, DC to Long Bridge and Virginia.

The Pennsylvania Railroad intentionally created that gap in the network of its competitor. Without access to Long Bridge, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad lost the ability to run trains from Maryland to Alexandria and then further south on the railroads in which it had a financial interest.

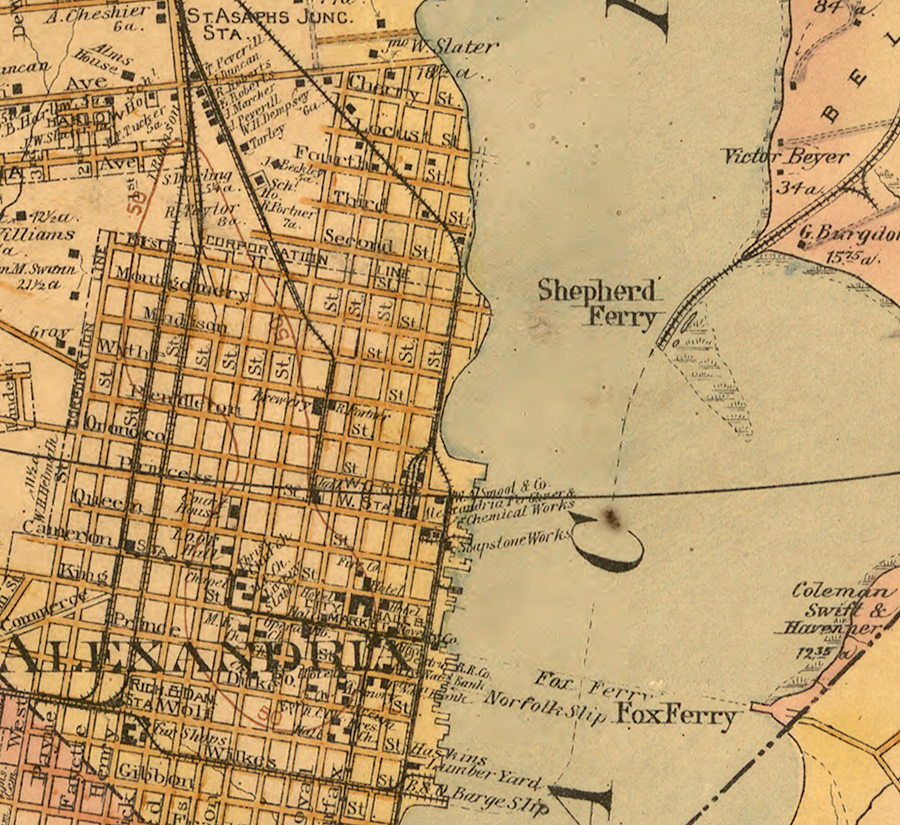

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad found a solution to get from Washington to Alexandria, but it was inefficient. The railroad regained access to Virginia in 1874 by building a branch line to Shepherd's Landing (now the site of the Blue Plains wastewater treatment plant) and floating rail cars from there across the Potomac River to Alexandria. The car float operation mimicked a technique used by the US Military Railroad during the Civil War to float barges with loaded rail cars down to Aquia Landing.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had to operate without a bridge crossing until 1904, when the competing railroads serving Alexandria made a truce and the Pennsylvania Railroad allowed competing lines to use Long Bridge. Between 1874-1906, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad trains to Alexandria went first to the station near the US Capitol, then looped back north to Bladensburg to reach a branch line that ran to Marbury Point. The 12-mile detour ended at a 1,400 foot pier on the north shore of the Potomac River which was just downstream of where the modern Blue Plains sewage treatment plant is located.

From that site, called Shepherd's Landing, railroad cars were floated across the Potomac River to the northern terminus of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. It was located at the foot of Wilkes Street, and is now Windmill Hill Park.5

the rebuilt Long Bridge which opened in 1872 was replaced in 1904, after the Pennsylvania Railroad gained control of the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad

Source: Library of Congress, Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. (1898)

In addition to interfering with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the Pennsylvania Railroad built its own railroad network south from Alexandria. It financed construction of the Alexandria & Fredericksburg Railway. That railroad built track north from Alexandria to the Long Bridge. The Pennsylvania Railroad also acquired control over the Alexandria & Washington Railroad segment in Virginia, so it had two sets of parallel tracks from the Long Bridge into Alexandria. The Alexandria & Fredericksburg Railway also built track from Alexandria south to Quantico.

Until 1872, trains that crossed the Potomac River could go further south only via the Orange Alexandria & Manassas Railroad, the successor to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. By constructing track from Alexandria to Quantico, the Pennsylvania Railroad created a link to the northern end of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac (RF&P) Railroad at Quantico.

In 1896, trolley tracks of the Washington, Alexandria, & Mt. Vernon Electric Railway were laid on Long Bridge. By the start of the Twentieth Century, 250 trains and trolleys were using the bridge each day. The draw span was opening 20 times daily, and the bridge was a rail transportation chokepoint.

In 1899, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central agreed to a Community of Interest Plan. Competition was so intense, with rates cut so low, that railroad operations were not profitable. The two major railroads, with support from New York bankers, agreed to acquire control of other railroads in order to control shipping rates. The Community of Interest Plan bypassed the power of the Federal government to block the railroads from making deals that limited competition and raised prices.

The Community of Interest Plan was a second attempt to manage competition. The first was creation of a Joint Traffic Association by 31 railroads operating east of Chicago in 1896. The US Supreme Court ruled in 1898 that the Joint Traffic Association violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

With shared ownership through the Community of Interest Plan, the major railroads were able to get funding from the bankers, buy competitors, and negotiate a truce. The Pennsylvania Railroad purchased control of the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad, its long-time rival. After the purchase, it was in the Pennsylvania Railroad's interest to make the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad more efficient and more profitable.

The Seaboard Air Line was not part of the Community of Interest Plan, and it threatened to disrupt the Northern Virginia railroad traffic pattern in 1900. The Virginia General Assembly sought to increase competition among the railroads. The legislature granted the Seaboard Air Line rights to build a new railroad line between Richmond and Washington, DC, parallel to the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac (RF&P) Railroad. The General Assembly also agreed to sell the state's shares in the RF&P to the Seaboard Air Line.

To eliminate that threat, the six competing railroads operating in Northern Virginia agreed to cooperate and built Potomac Yard in Alexandria in 1906. All railroads were granted equal access to that yard, where cars could be interchanged easily among the different railroads. As part of the negotiations to create a common site for classifying cars and assembling trains at Potomac Yard, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was allowed to use Long Bridge again and shut down its car float operation between Shepherd's Landing and Alexandria.

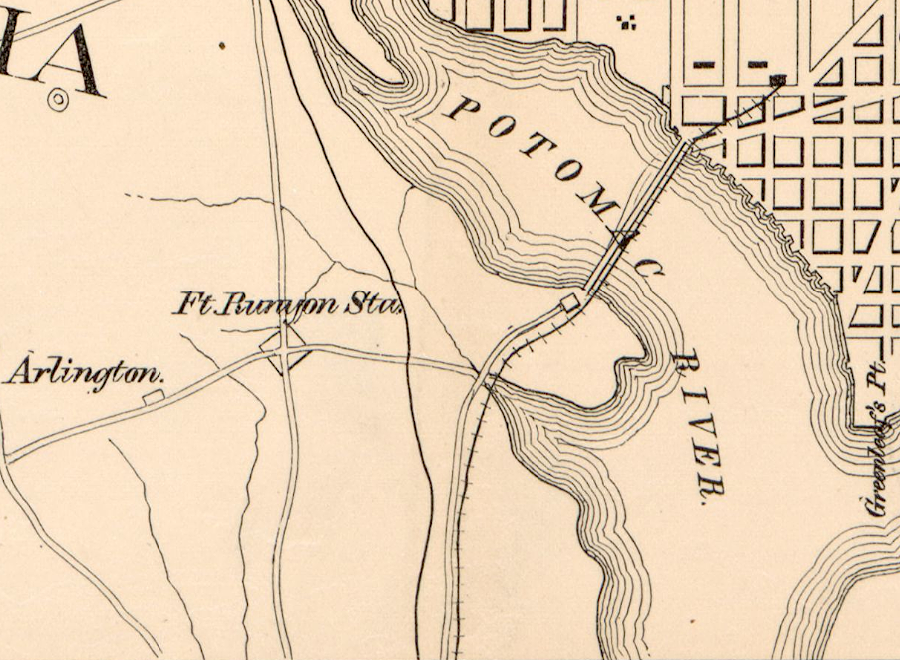

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad operated a car float from Shepherds Ferry to the Alexandria waterfront from 1874 until Potomac Yard was built

Source: Library of Congress, The vicinity of Washington, D.C. (by Griffith M. Hopkins, 1894)

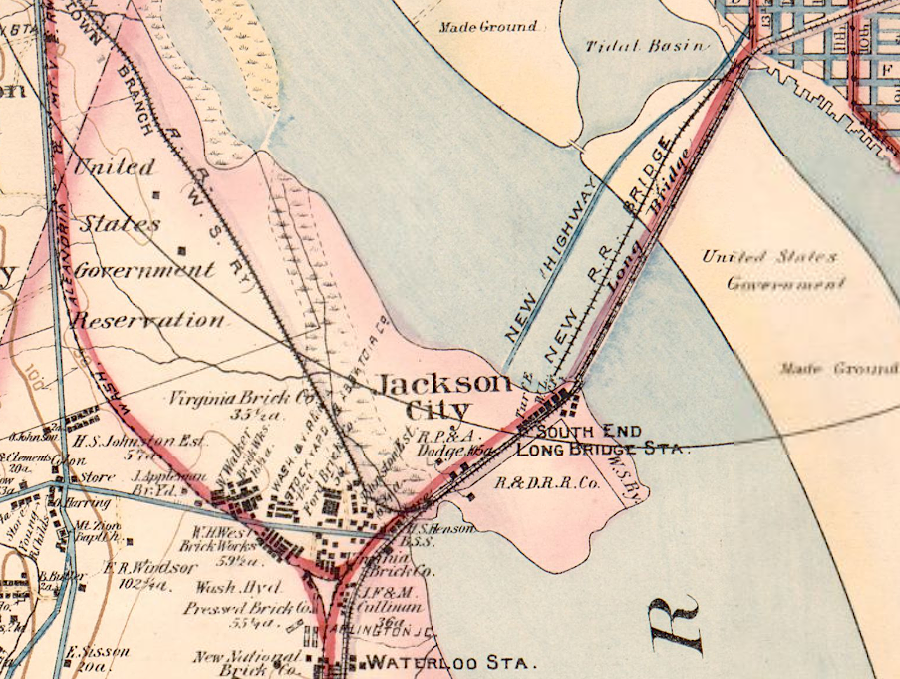

Establishing a truce among the railroads allowed the Pennsylvania Railroad to upgrade its infrastructure. A new railroad bridge across the Potomac River was completed in 1904. It was built about 150 feet upstream of the existing Long Bridge.

After creating the railroad-only Long Bridge, tracks were no longer needed on the old structure used also by wagons, horses, and pedestrians and the Pennsylvania Railroad removed its tracks. The old Long Bridge lasted just two more years. It was replaced in 1906 with a new structure known as the Highway Bridge. Since then, other highway bridges have been constructed with different names and "Long Bridge" has referred to just the 1904 railroad bridge.6

the new railroad bridge opened in 1904, and a new Highway Bridge opened upstream in 1906

Source: Library of Congress, Baist's map of the vicinity of Washington D.C. (1904)

The 1904 railroad bridge had 13 truss spans to support two tracks, with a swing span that allowed ships to move upriver and downriver. The steel and wrought iron trusses were recycled from a previous bridge across the Delaware River at Trenton, NJ.

The 1906 Highway Bridge was constructed with space for trolley tracks. That 1906 structure lasted until 1967. To provide more capacity for cars, new bridges were completed downstream in 1950 and 1962.7

Long Bridge was built in 1904 downstream from the highway bridge

Source: Library of Congress, Pictorial map of Washington D.C. (c.1915)

the swing spans of the Long Bridge in 2019 were the trusses built in 1904

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Long Bridge Study (January 2015)

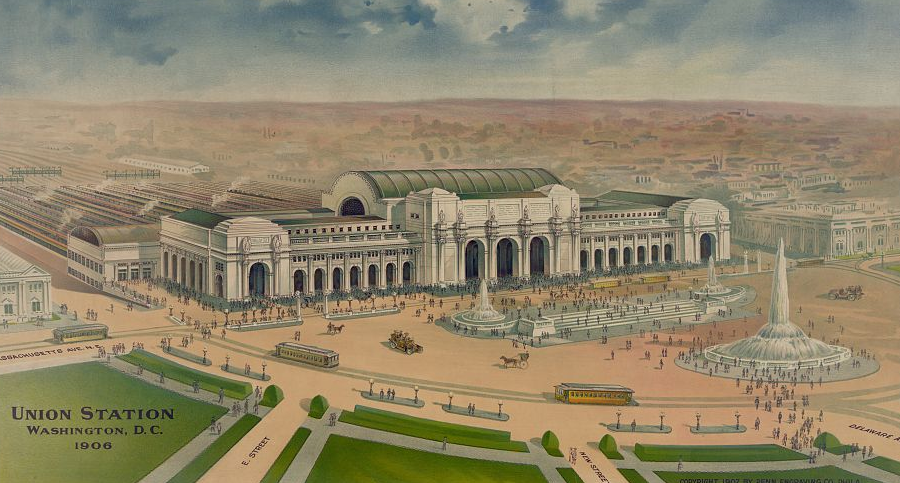

Another result of the truce between competing railroads was the construction of Union Station in Washington, DC, which opened in 1907. Construction of a "union" station serving all the railroads allowed for development of the National Mall as envisioned by the McMillan Commission.8

after railroads managed to reduce competition, they partnered to complete Potomac Yard and Union Station

Source: Library of Congress, Union Station Washington, D.C. 1906

Two of the Long Bridge spans on the Virginia shoreline were removed when the George Washington Memorial Parkway was built in 1931-1932. In 1935 the Pennsylvania Railroad electrified its track across the Long Bridge to Potomac Yard.

As rail traffic increased during World War II, the US government bult an "Emergency Bridge" to connect Shepherds Landing in the District of Columbia with Alexandria. The second bridge, built between June 3-November 1, 1942, provided additional security in case Long Bridge was disabled by accident or sabotage. Both the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad used the Emergency Bridge, until it was taken out of service on November 14, 1945 and dismantled two years later.

In 1942, Long Bridge was permanently strengthened to allow heavier loads. The 11 truss spans that were not part of the swing span section were replaced with 22 girder spans, and 11 extra piers were added to support them. The swing span was last used on March 3, 1969. That allowed a barge transporting a segment of the 1906 highway bridge to be floated on a barge downstream to Dahlgren. US Navy pilots practiced dropping bombs on the bridge span before going to Vietnam.

except for the swing spans, girder spans carry the Long Bridge across the Potomac River

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Presentation Boards at Public Meeting 1 on November 13, 2012

The catenary for the electric locomotives was removed in 1981, after Conrail switched to locomotives powered by diesel fuel. The Pennsylvania Railroad had become part of the Penn Central Railroad in 1968, and then Conrail in 1976. In 1999, CSX Transportation, Inc. (CSXT) acquired ownership of the Long Bridge. Passenger service was provided by Amtrak after it was created in 1971, and by the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) starting in 1992.9

adding two more tracks to the capacity-filled Long Bridge will allow Amtrak and the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) to carry more passengers from Virginia to DC and points north

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Long Bridge Study (January 2015, Chapter 1, p.2)

In 2011 the Federal Railroad Administration funded the first of many studies for replacing the two-track bridge. To the north and the south there are three tracks, and bridge's condition requires train speeds to be constrained. A maximum of 96 trains can use it within 24 hours.

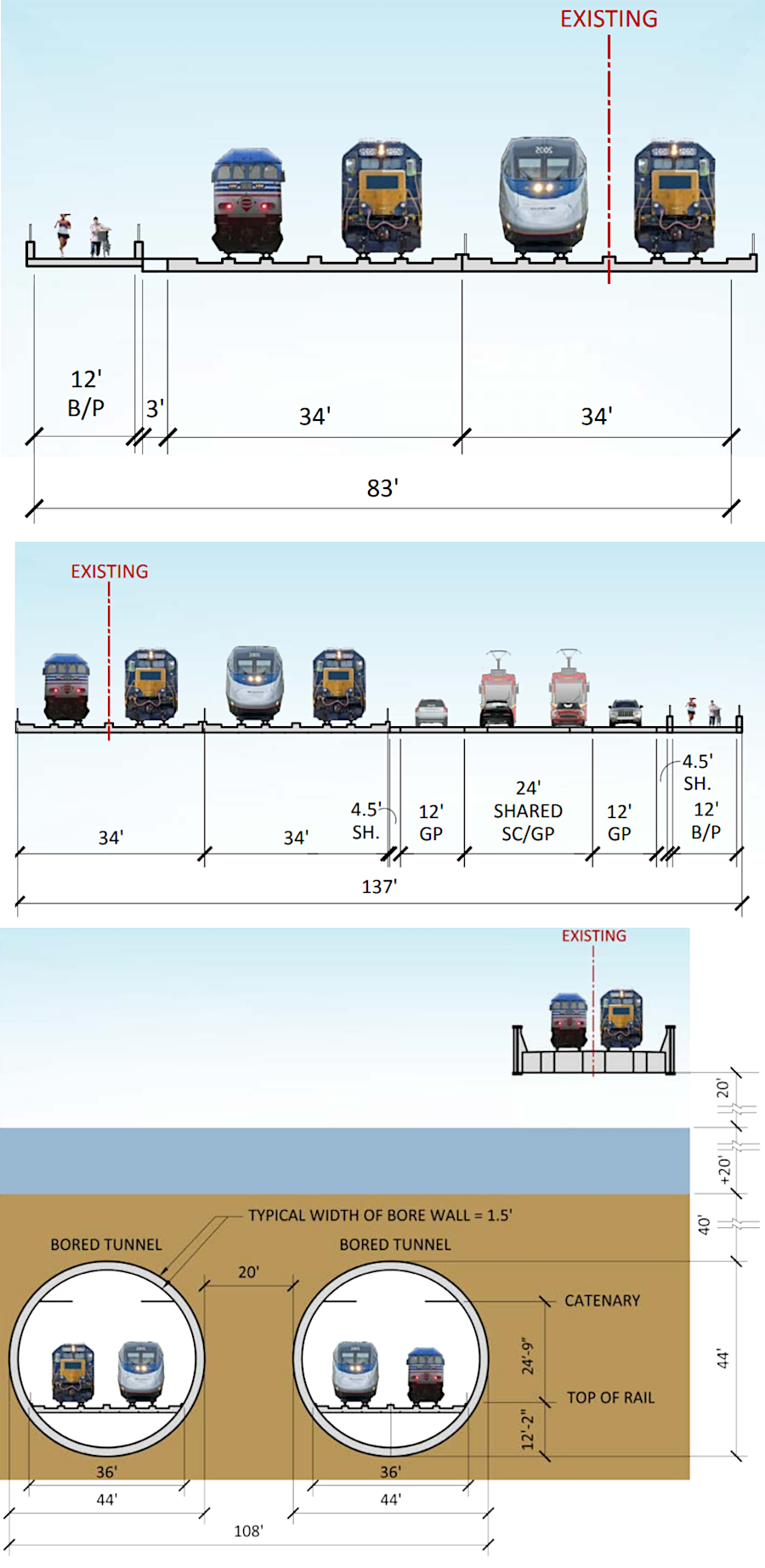

A 2015 Long Bridge Study concluded that adding two tracks could increase capacity to 166 trains per day. Various alternatives also examined the potential of adding lanes for trolleys, bikes/pedestrians, and even cars.10

Seven of the nine serious options were screened out before completion of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in September, 2019. That EIS examined two alternatives plus the "no action" option. The alternative of building two new, two-track bridges across the Potomac River was not recommended.

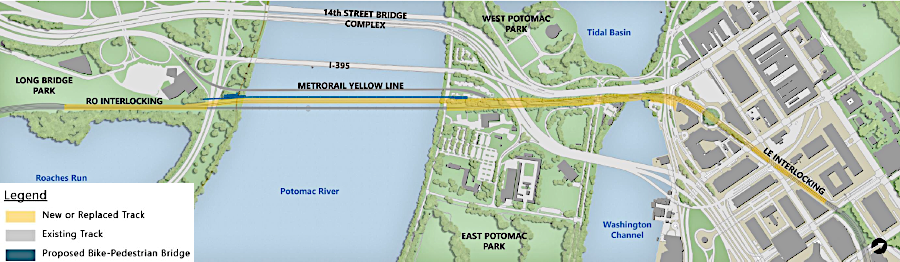

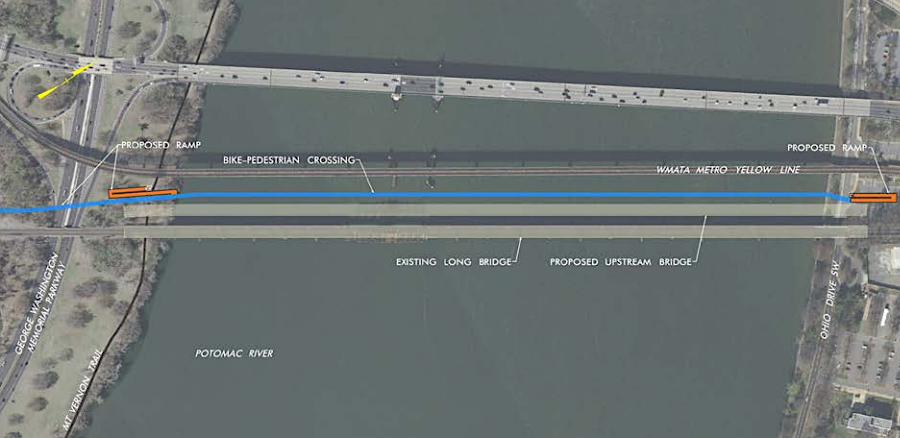

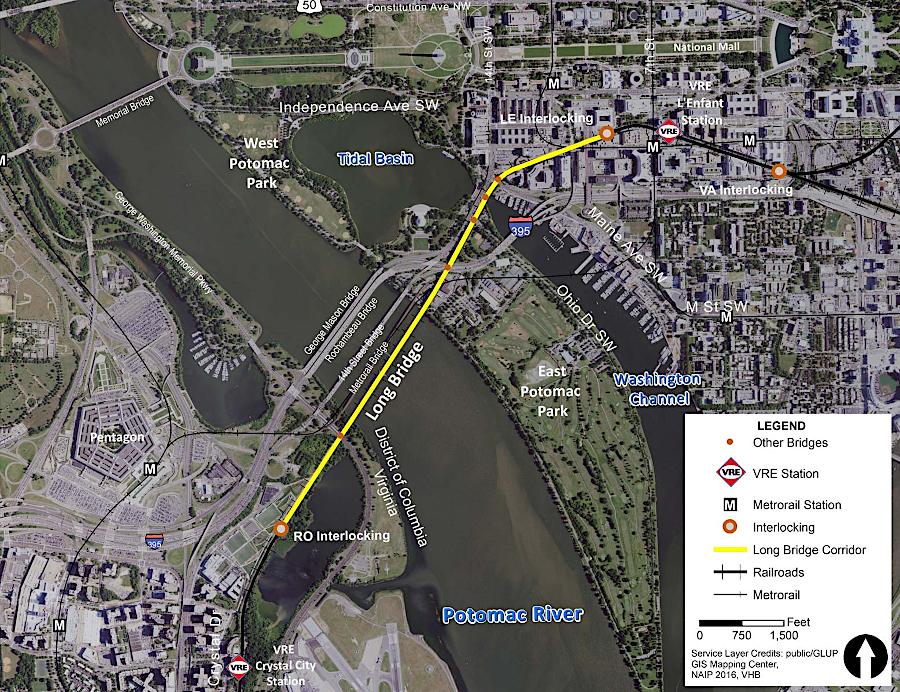

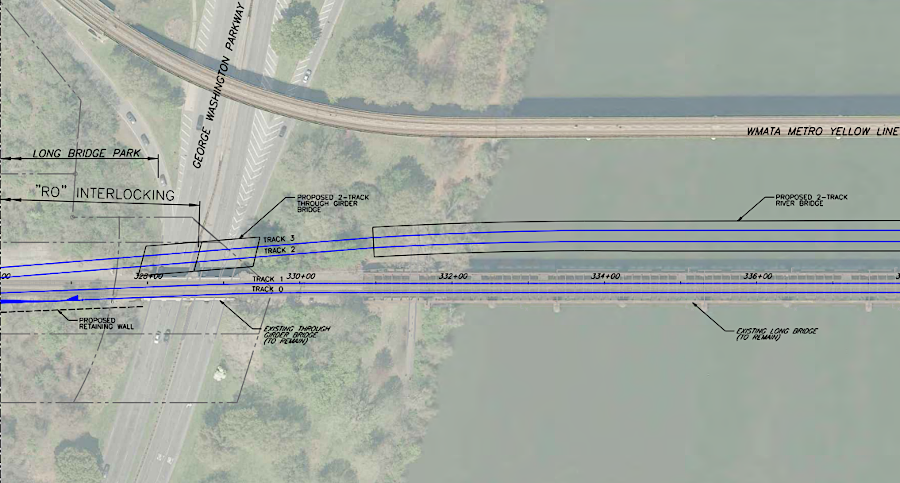

The preferred alternative was to build a new two-track bridge dedicated to passenger service, and retain the existing Long Bridge for just freight trains. The 1904/1942 bridge had been rehabilitated in 2016 and did not need to be replaced.

The 2019 Draft EIS concluded that an additional two-track bridge, plus extra tracks on either end, would allow CSX, Amtrak, VRE, and Norfolk Southern to operate up to 192 trains per day.11

alternatives considered in 2015 included adding two tracks plus bike/pedestrian lanes, adding an additional two lanes for streetcars and two lanes for cars, and building two tunnels

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Long Bridge Study (January 2015, p.9)

In addition, the Draft EIS recommended that a separate bike/pedestrian bridge should be constructed. It would be located between the new bridge for passenger trains and the existing Metrorail bridge.

the preferred alternative of the Long Bridge project includes a separate bike/pedestrian bridge, upstream of a new two-track rail bridge

Source: Long Bridge Project, Combined Final Environmental Impact Statement/Record of Decision and Final Section 4(f) Evaluation (Figure 2-1) and Appendix A: Final Section 4(f) Evaluation (Figure 6-1)

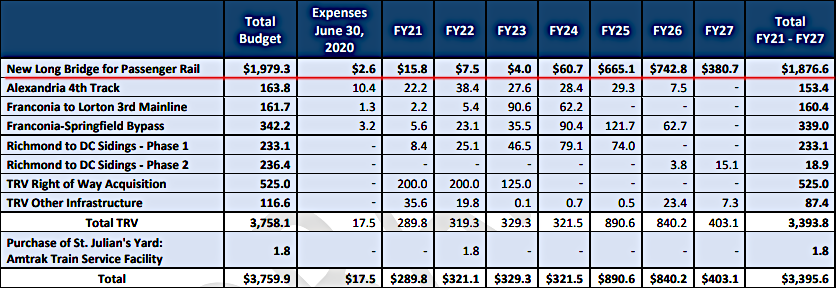

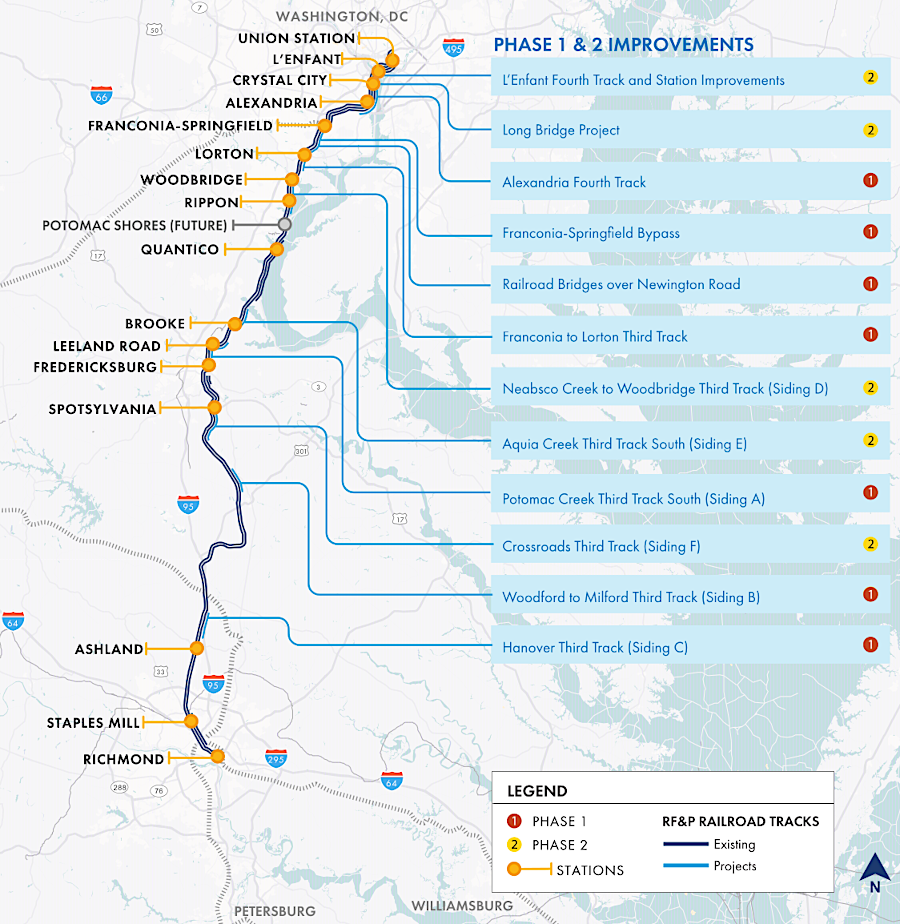

In December, 2019, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam announced a deal with CSX to acquire track and right-of-way to upgrade passenger rail capacity across the state. As part of the $3.7 billion package, the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) agreed to serve as the lead agency to build a new $1.9 billion Long Bridge.

The preferred alternative in the Final Environmental Impact Statement completed in August, 2020 was to build a new two-track rail bridge upstream from the existing CSX structure, plus a separate bike/pedestrian bridge over the Potomac River. The new bike/pedestrian bridge was incorporated as mitigation for the impacts to the Mount Vernon Trail and other property in the National Park Service system, including permanent conversion of 2.5 acres of parkland to railroad use. The alternative option was to replace the existing CSX bridge, in addition to adding two tracks on a new bridge. Both options included replacing the existing bridge over the George Washington Memorial Parkway in Virginia.

When the new railroad bridge parallel to the existing Long Bridge is completed in 2027, Virginia will own two tracks from L'Enfant Plaza in the District of Columbia south to Alexandria. That will allow passenger trains to be scheduled without interference from freight trains, which receive priority on the CSX tracks.

Funding for the new bridge would come from three sources. Virginia agreed to pay one-third. The Federal government and Amtrak would pay another one-third, in part via federal grants for the Atlantic Gateway project. The last one-third would be funded through a regional partnership which would include funding from the District of Columbia and Maryland, with details to be resolved later.12

The Northam Administration planned to divert revenues from tolls on I-66 inside the Beltway, which had been used by the Northern Virginia Transportation Commission to ease traffic congestion on roads near that stretch of I-66. The tolls would be used to finance bonds for bridge construction.13

the first budget for the Virginia Passenger Rail Authority, established in 2020, emphasized funding for Long Bridge

Source: Virginia Passenger Rail Authority, Virginia Passenger Rail Authority Operating Budget (2020 Powerpoint)

The deal with CSX was not finalized until March, 2021. Amtrak committed $944 million, and received a 30-year exclusive right to offer long-distance passenger rail service on the I-95 corridor - reminiscent of the original 30-year monopoly on railroad traffic between Richmond and Washington given to the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad in 1834. The $3.7 billion Transforming Rail in Virginia Initiative will allow Amtrak to double the number of trains it runs from Virginia north into Washington, and increase Virginia Railway Express (VRE) service by 60%.

building a new Long Bridge was part of the statewide $3.7 billion Transforming Rail in Virginia initiative announced in 2019

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Transforming Rail in Virginia

At the conclusion of negotiations, Northam made clear that the investment in rail transportation was a preferred alternative to further widening of I-95. The governor remarked that trains generated fewer greenhouse gas emissions compared to cars and truck. He highlighted that rail was more cost-effective for moving freight and people on the I-95 corridor, since adding one lane to the interstate for 50 miles in each direction would cost $12.5 billion:14

Observers can see Long Bridge today from Long Bridge Park, which opened in 2011. A Phase II expansion is planned for the 4 acres to the north, which was occupied by the Twin Bridges Marriott hotel from 1957-1990 and then became the site of the Long Bridge Aquatics & Fitness Center.15

In 2023, the Virginia Passenger Rail Authority reported that the projected cost of the new Long Bridge had climbed 10% in the last year, up to $2.3 billion. At that point, Virginia had commitments for 90% of the funding necessary for the $7.2 billion rail transformation program and was still seeking the remaining $712 million.

Later in 2023, the US Department of Transportation announced a $729 million award from the Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail Grant Program, created after the US Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) in 2021. That funding also was directed towards completion of a third track between Neabsco Creek to Woodbridge in Prince William County (Siding D), two miles of a third track in Stafford County (Siding E), and approximately four miles of a third track in Spotsylvania County (Siding F).

Completing the new Long Bridge by 2030 remained the priority. Other projects could be delayed until funding became available for them because, as a story in the Washington Post noted:16

on the Virginia side, the Long Bridge project ends at the RO interlocking with CSX tracks

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Long Bridge Corridor Map

tracks from the new and old railroad bridges were planned to meet at the RO interlocking

District of Columbia Department of Transportation, Alternatives Development Report: Appendix (Option A: 3 of 6)

adding two more tracks to the capacity-filled Long Bridge will allow Amtrak and the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) to carry more passengers from Virginia to DC and points north

Source: Long Bridge Project, Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Alternatives Development Report (Figure 1-1)

projected appearance of Long Bridge, with separate bike/pedestrian path

Source: Virginia Passenger Rail Authority, Long Bridge Progress 2022-06-02