High-Speed Rail in Virginia

the Northeast Corridor between Washington DC and Boston has been the focus for high-speed rail operation in the United States, with service by TurboTrain, Metroliner, and since 2000 the Acela Express

Source: Amtrak, A Vision for High-Speed Rail in the Northeast Corridor

Most passenger trains in Virginia average less than 50mph, and none are authorized to travel at speeds greater than 79mph. "High-speed" rail would allow trains to go 90-110mph between stops.

Expanding the number of cities serviced by high-speed rail will require a massive amount of funding to upgrade track significantly. Existing locomotives and rail cars could go faster than 79mph. The constraint is track infrastructure. It must be modified to reduce the angle of curves, enhance ties and ballast, and replace existing signals.

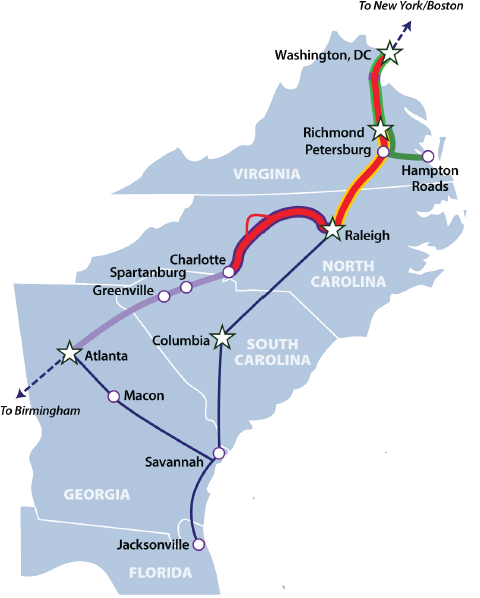

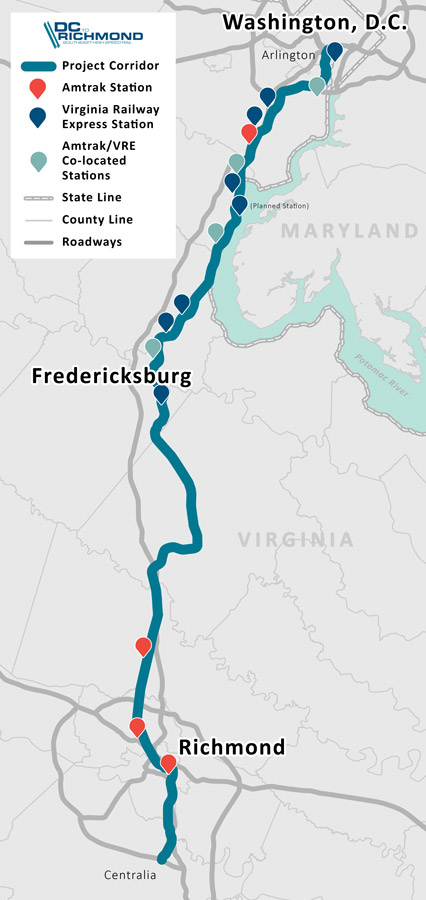

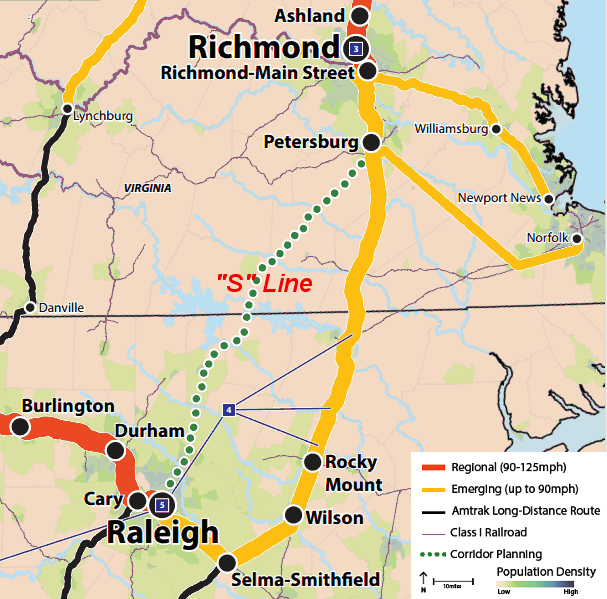

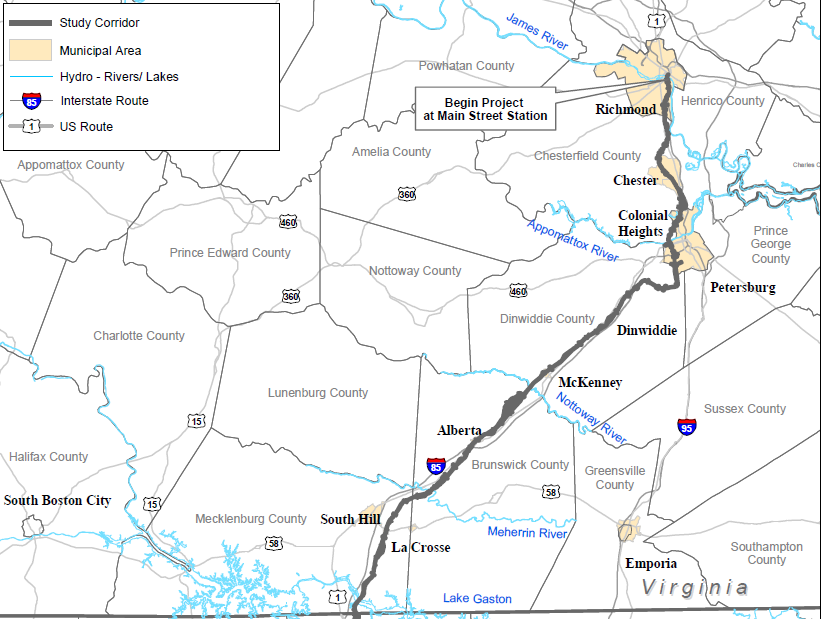

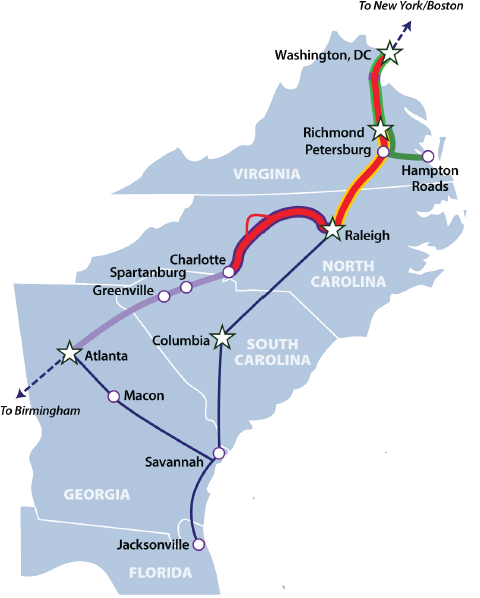

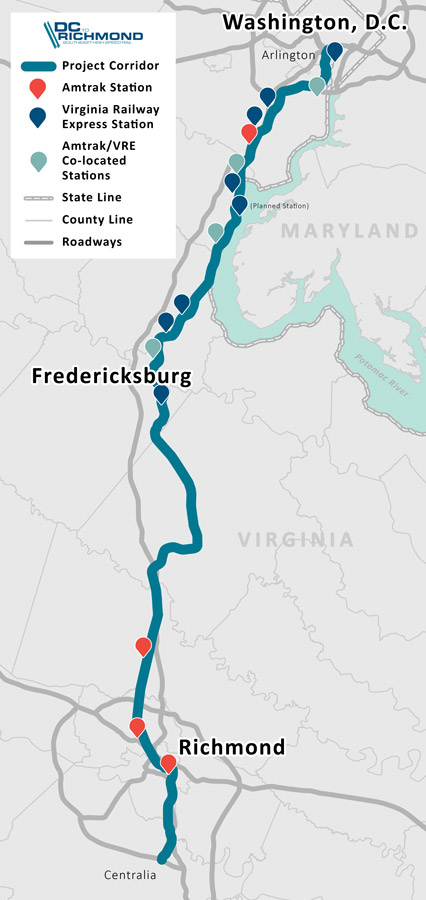

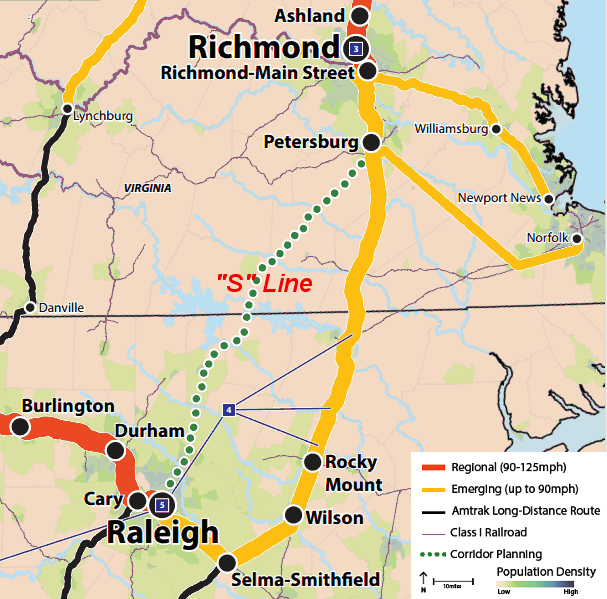

The Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), the Federal Railroad Administration, and Amtrak have coordinated to develop a plan to upgrade existing track and signaling systems, and to construct new track. The goal is to offer high-speed rail between Washington DC through Richmond to Raleigh, North Carolina, and to offer service from Richmond to Hampton Roads as well.

studies are scheduled at different times to examine the costs and environmental impacts of a high-speed rail corridor, with the initial focus to link Washington to Charlotte and Hampton Roads (and the potential to connect to Atlanta and even Jacksonville)

Source: Southeast High Speed Rail (Raleigh to Richmond) Tier II Study, Project Map

Streamliners pulled by diesel locomotives operated at over 100mph in the 1930's, but the Great Depression made it uneconomical for railroads to maintain most passenger routes. After a brief peak o business during World War II, railroads sought to abandon passenger service.1

In 1952, the Interstate Commerce Commission established the 79mph speed limit for passenger trains unless railroads upgraded communications and control systems. For passenger trains exceeding 79mph, the Federal agency required signals to be installed inside the cab of locomotives so engineers would see yellow/red warnings more easily, or installation of automatic train controls to trigger brakes based on signals.

With demand already declining, there was little incentive for railroads to invest the additional capital required to improve safety and operate passenger trains beyond the 79mph limit. Freight traffic provided 90% of the railroad profits, and the Santa Fe railroad was one of the few to install signals so it could operate its Chicago-Los Angeles streamliners at 100mph.

Rather than compete by offering faster connections between destinations, railroads competed with each other for passengers by offering more conveniences such as dome cars for tourism. Railroads stopped trying to compete with automobiles for convenience or with airplanes for speed, at the same time as the interstate highway system was completed and jet engines enabled faster airline flights. By 1959 Trains magazine summarized the decline in an article "Who Shot the Passenger Train?"2

Amtrak replaced private railroad operations and started offering passenger rail service in 1971. It inherited two TurboTrains from Penn Central, developed by the U.S. Department of Transportation and designed to offer high-speed passenger service in the Northeast Corridor. Those trains were used to provide service to New York City, and were also exhibited in Virginia and elsewhere as Amtrak showcased technology in a national tour.

the two TurboTrain trainsets inherited by Amtrak were used for only five years

Source: Amtrak, TurboTrain at Petersburg, Va., 1971 and TurboTrain in Amtrak livery, 1970s

The TurboTrains were taken out of service in 1976, but Metroliner cars capable of going 110mph stayed in service until 2006. Amtrak ordered almost 500 Amfleet cars based on the Metroliner design; those cars were capable of going 120mph. In four decades of service, most Amfleet cars traveled at 79mph or slower because there were few sections of track with the signals and infrastructure to support high-speed trips.

High-speed service has been concentrated on the DC-Boston track since Amtrak was formed. In 1976, after acquiring ownership of much of the track in the Northeast Corridor, Amtrack invested $2.5 billion to upgrade the rail system in the Northeast Corridor. In 2000, Amtrak started Acela Express service. It demonstrated the potential for high-speed passenger trains to compete with airplanes for trips up to 500 miles.3

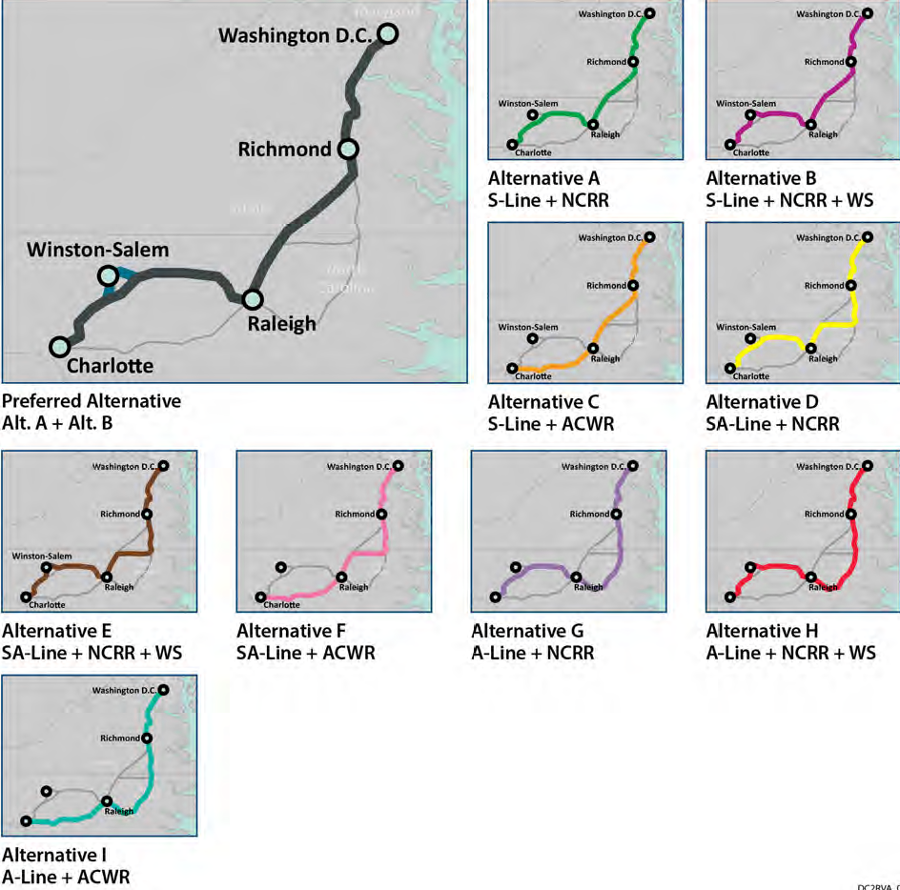

The US Department of Transportation defined the 450-mile long Southeast High Speed Rail (SEHSR) corridor between Washington, DC - Charlotte, NC in 1992, then added a Richmond-Hampton Roads extension in 1995. As proposed, the corridor would support four round-trip, high-speed trains running daily through Virginia between Raleigh, North Carolina and Washington DC.

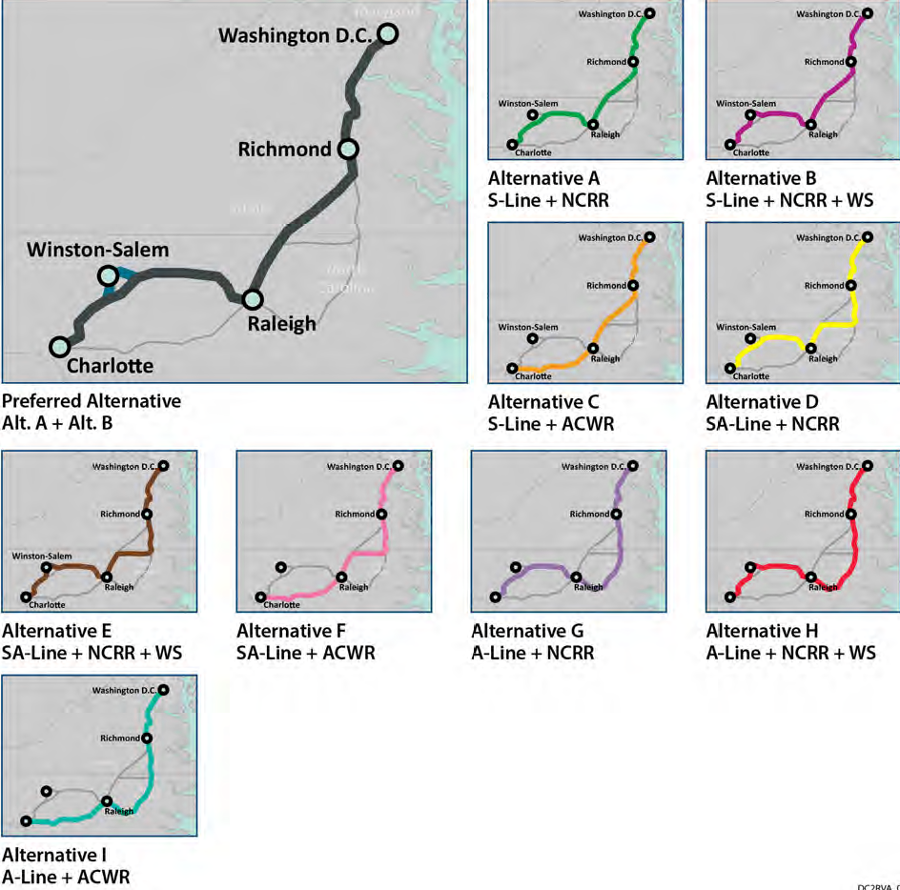

alternatives considered in 2002

Source: DC to Richmond High Speed Rail Draft Environmental Impact Statement, SEHSR Tier I EIS Build Alternatives (Figure 2.1-2)

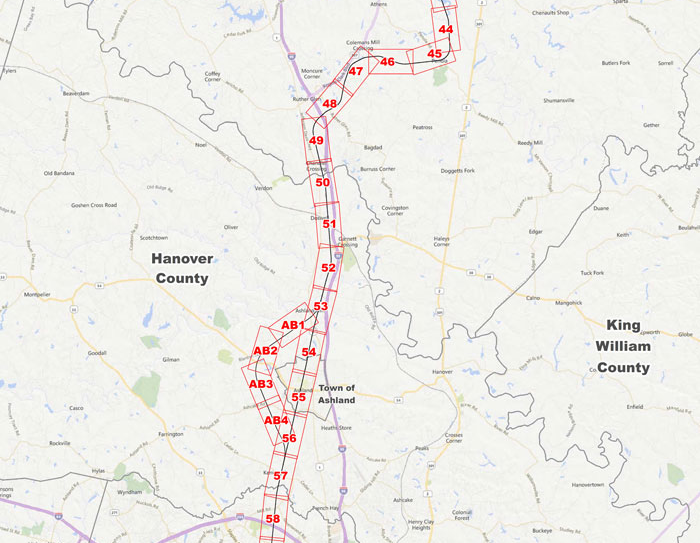

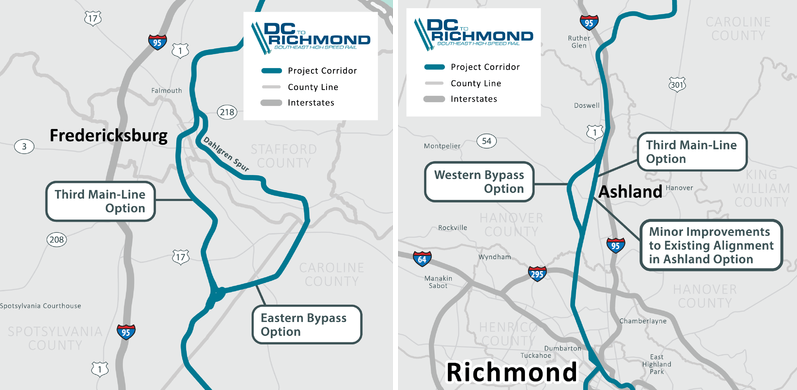

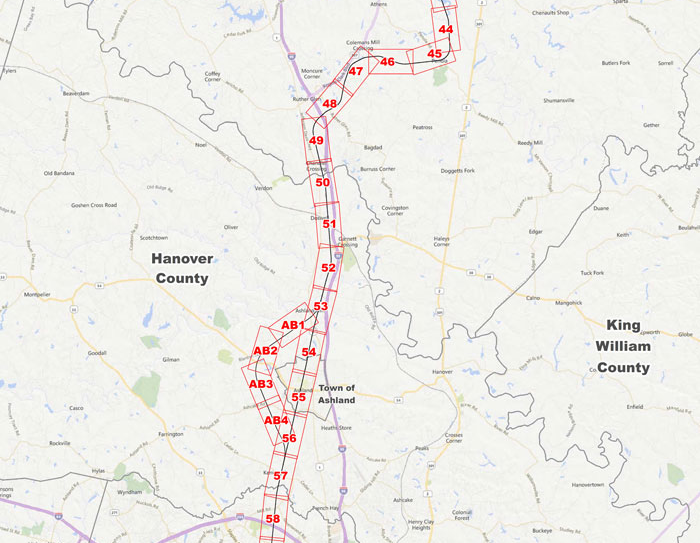

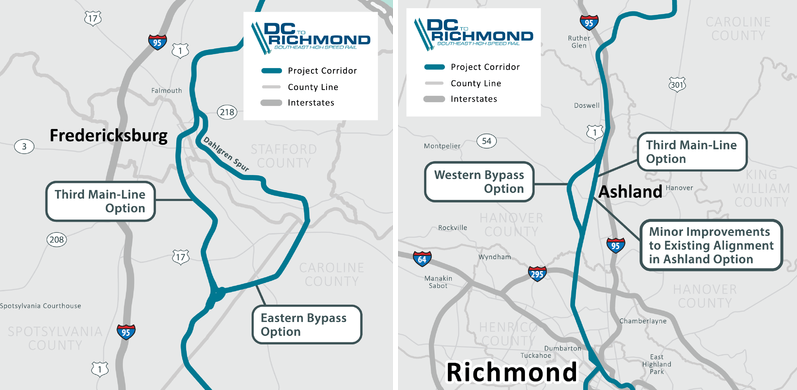

The impacts of widening the existing tracks, adding another set of tracks to support high-speed rail, generated some opposition. Residents in the Town of Ashland objected to adding a third track through the center of town, potentially eliminating a road serving businesses on one side of the existing two tracks. The existing two tracks bisect the campus of Randolph-Macon College, and college officials also opposed adding a third track.

one alternative for high-speed rail includes building a western bypass around the town of Ashland, rather than trying to squeeze another track into the existing right-of-way

Source: Families Under the Rail, Map of Central Section, DRPT Rail Project

One alternative was to build a new rail line through undeveloped land on either side of the town. However, residents in Hanover County sought to block any bypass proposals. Further north, supervisors in Spotsylvania, Stafford and Caroline counties expressed opposition to a bypass east of Fredericksburg. The Virginia Secretary of Transportation said at a 2016 public meeting in Ashland:4

- I wish I could stand up here and tell you that, as we move forward, that everyone in this room will be happy. I don't think that'll be the case.

new rail bypasses east of Fredericksburg and west of Ashland were proposed as alternatives to building new track and routing high speed passenger trains through the center of those communities

Source: D.C. to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail, Fredericksburg Alternatives and Ashland/Hanover County Alternatives

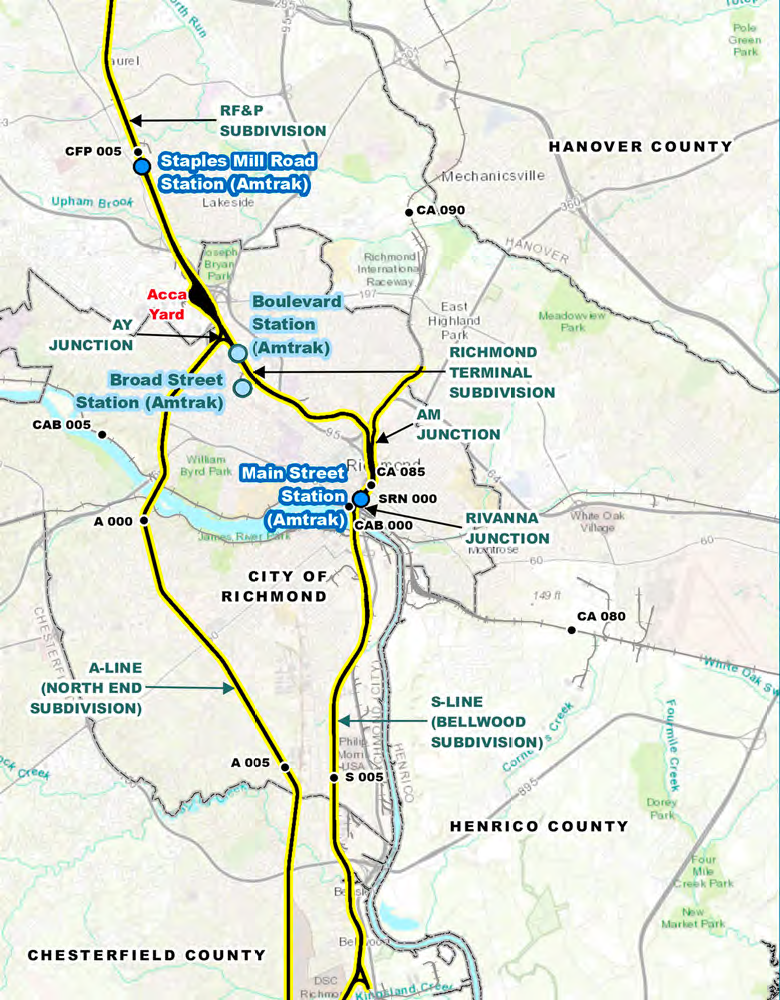

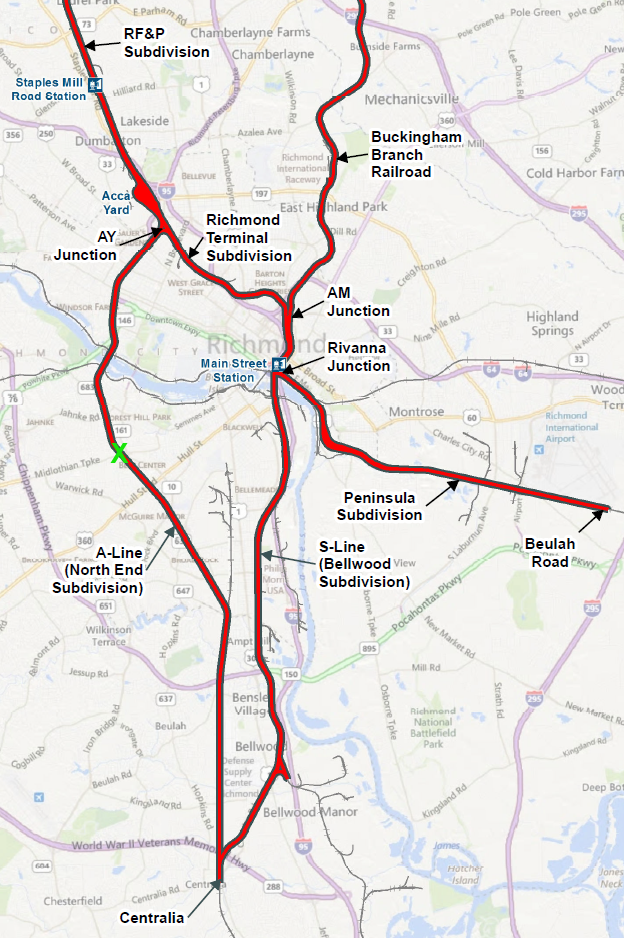

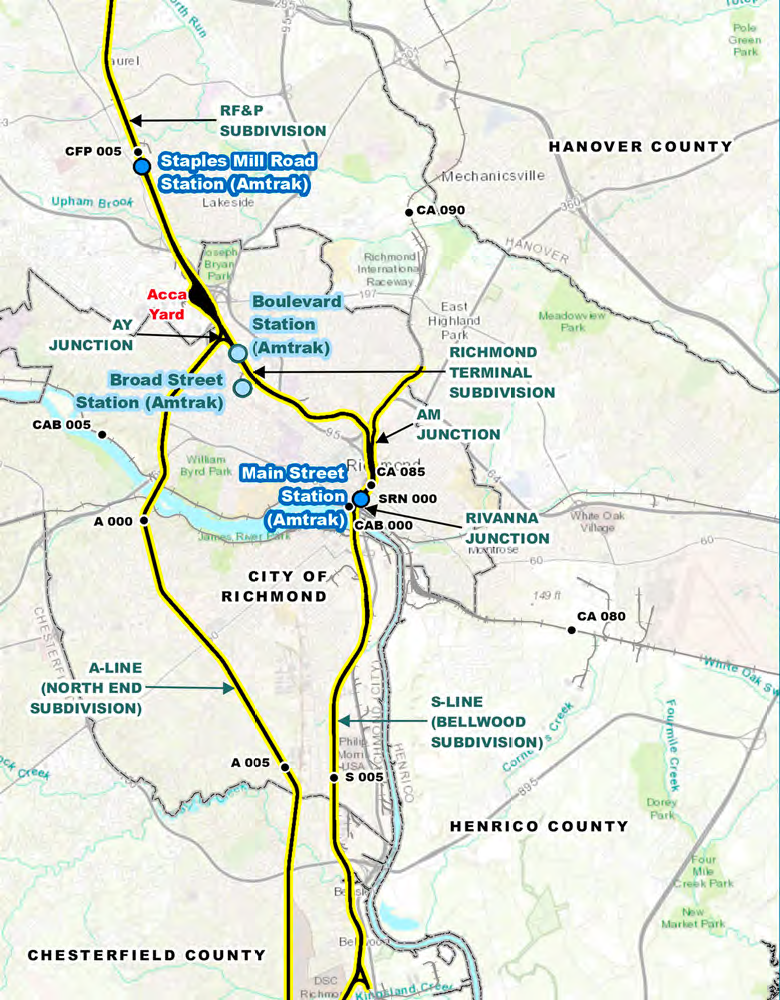

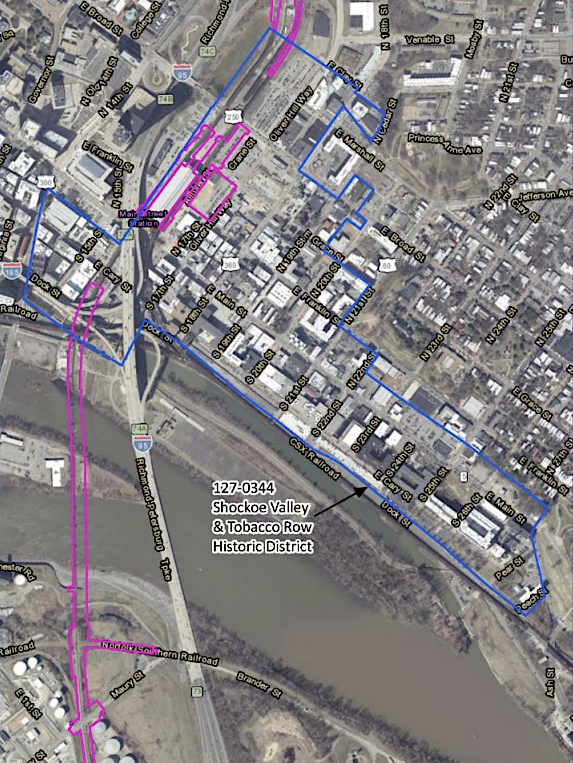

In Richmond, one alternative was to shift the passenger terminal from the suburban station at Staples Mill Road north of the city to the downtown Main Street Station.5

plans to implement high-speed rail between Washington, DC and Richmond are based on using the existing CSX rail right-of-way

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation - Washington DC to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail project, DC2RVA Project Map

The reduction in travel time is the key benefit of high-speed rail, and each stop slows down the train. Virginia could have just one high-speed rail stop, and it is likely to be in the Richmond area.

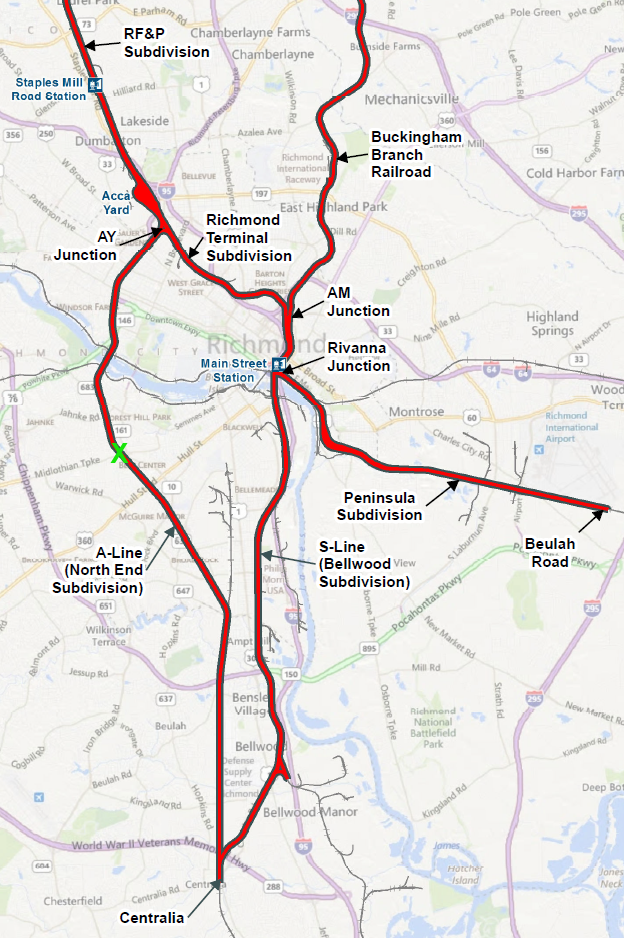

The complex track configuration from Acca Yard and connecting to the Peninsula Subdivision slows down trains that stop at Main Street Station. If the state government is dominated by the Democratic Party at the time funding must be provided for high-speed rail, the technical challenges could be overcome as proposed in the initial Southeast High Speed Rail planning. Revitalizing the urban core of Richmond by choosing the Main Street Station as the designated stop would provide benefits to urban districts that elect Democratic legislators.

determining the location of the passenger station in Richmond involves trade-offs between servicing downtown Richmond vs. speeding trains through the bottleneck of Acca Yard2

Source: DC to Richmond High Speed Rail Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Richmond Area Station Options (Figure 2.4-1)

If the General Assembly is dominated by the Republican Party at the time funding must be provided for high-speed rail, revitalizing a suburb represented by Republican legislators might affect the station location. Funding could be directed towards Staples Mill, even if the particular House of Delegates or State Senate district in Henrico was represented by a Democratic legislator. In 2013 a key Republican legislator, State Senator John Watkins (R-Powhatan), had proposed a site in Chesterfield County:6

- I think the main line comes right up Belt Boulevard, and it should near Belt Boulevard and Midlothian Turnpike. There's enough space there and that area needs to be revitalized anyway. You don't have to jag all around Main Street Station.

- Thirty years from now, they'll have it figured out. There's not going to be but one stop. Even with Henrico, Chesterfield, Prince George and Dinwiddie counties along with Richmond, Petersburg, Colonial Heights and Hopewell, you're still not at 2 million people.

Amtrak trains headed south of Richmond stop at the Staples Mills Road Station, then go via the A-line ("Belt Line") between Acca Yard and Centralia

(green X marks high-speed rail station location proposed by State Senator John Watkins in 2013)

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, D.C. to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail - Purpose and Need Statement (Figure 6, p.22)

If a series of high-speed rail projects are funded and implemented to cover territory south of Richmond, passenger trains would operate at up to 90mph between Richmond-Petersburg. The Petersburg-Norfolk extension would also operate at 90mph.

State funding comes from the Intercity Passenger Rail Operating and Capital Fund (IPROC), established by the General Assembly in 2011. After receiving interim funding during the next two years, the 2013 General Assembly:7

- ...made Virginia the first state to fund - in a sustainable and dedicated manner - advancement of intercity and highspeed passenger rail. It dedicates 0.05 percent of the state's sales and use tax to IPROC.

South of the Collier Yard at Petersburg, trains could reach 110mph on their journey to Raleigh, NC. Trains run at 125-135mph in Europe and even faster in Japan/China, but feasibility studies determined it would not be cost-effective to electrify the Southeast High Speed Rail corridor in order to support speeds greater than 110mph.8

The Record of Decision for the Tier II Environmental Impact Statement was signed on September 5, 2019. It determined that a fourth track would be added between the Long Bridge and Alexandria, and a third track would be added between Alexandria down to Ashland. That third track would pass through downtown Fredericksburg, but through Ashland there would only two tracks. The bypasses around Fredericksburg and Ashland that had been considered were, in the end, rejected.

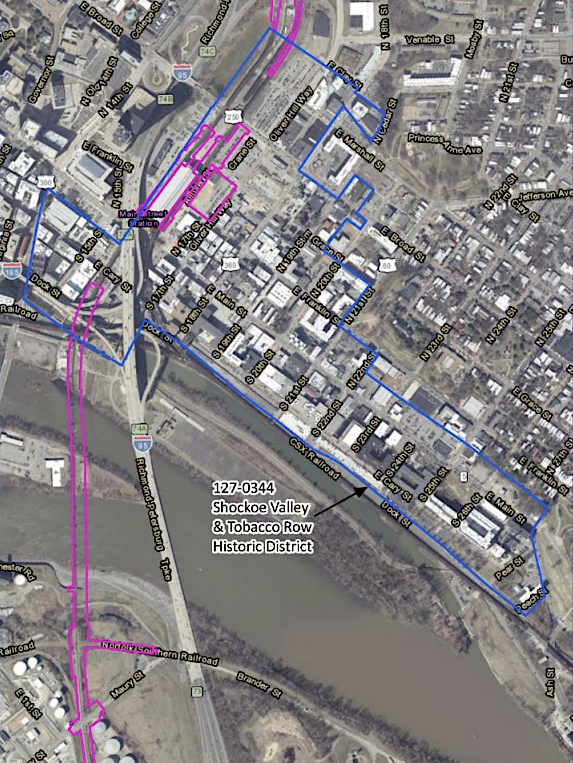

Both Staples Mill Road Station and Main Street Station in Richmond would retain full service; all passenger trains that stopped in Richmond would serve both stations. A new major railroad bridge would be built across the James River, just upstream of the I-95 bridge.9

providing high-speed rail through Richmond required building a new bridge across the James River

Source: Federal Railroad Administration and Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Record of Decision Attachment A: Final Section 106 Memorandum of Agreement (p.61)

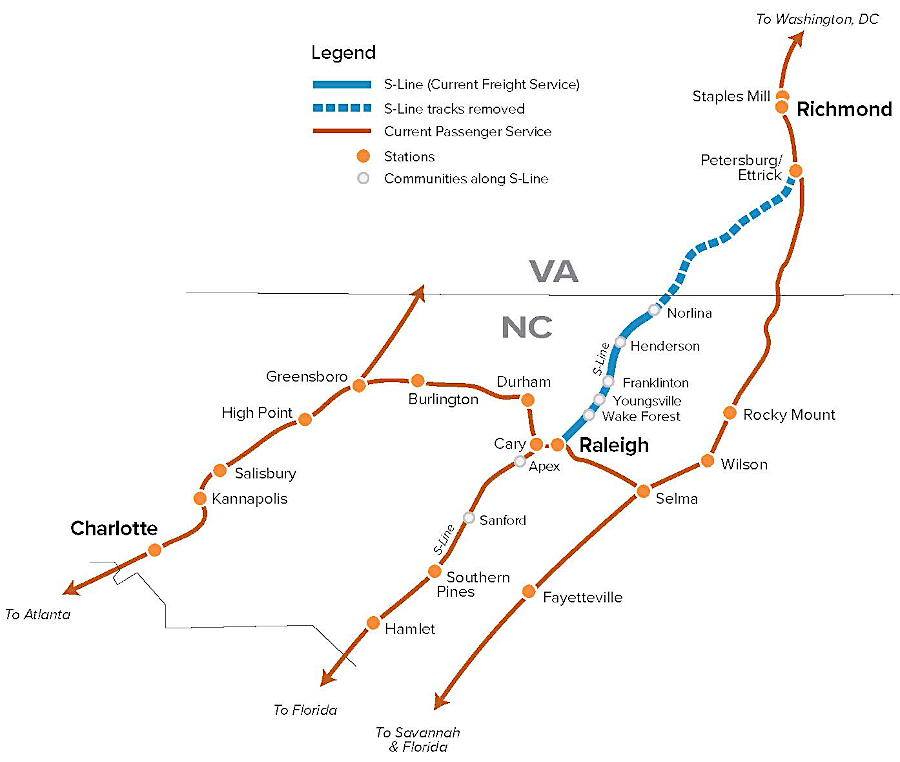

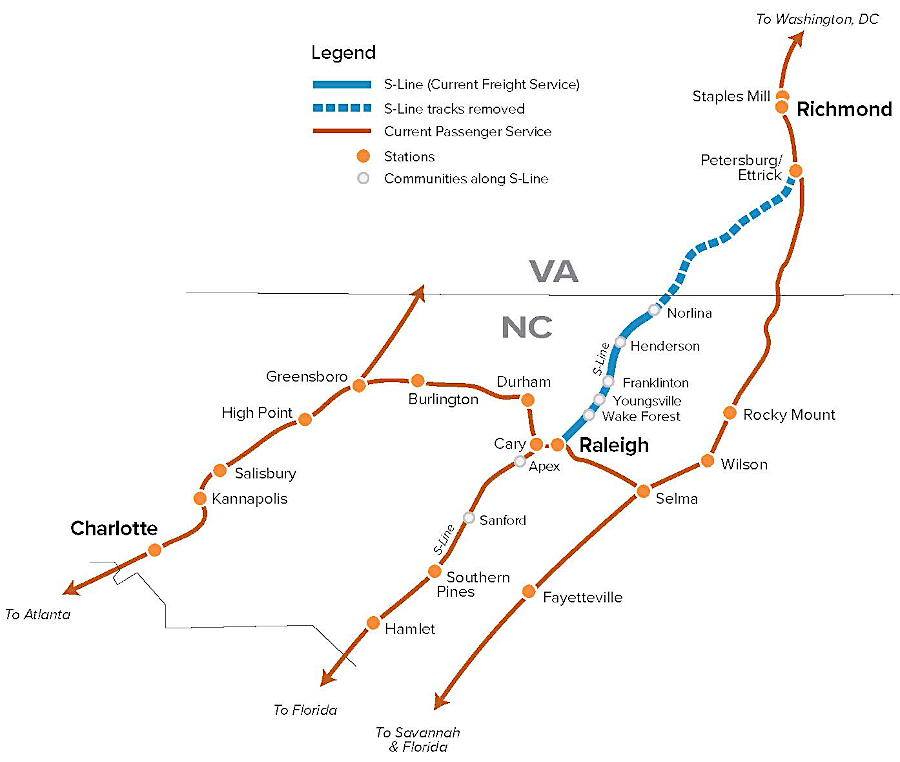

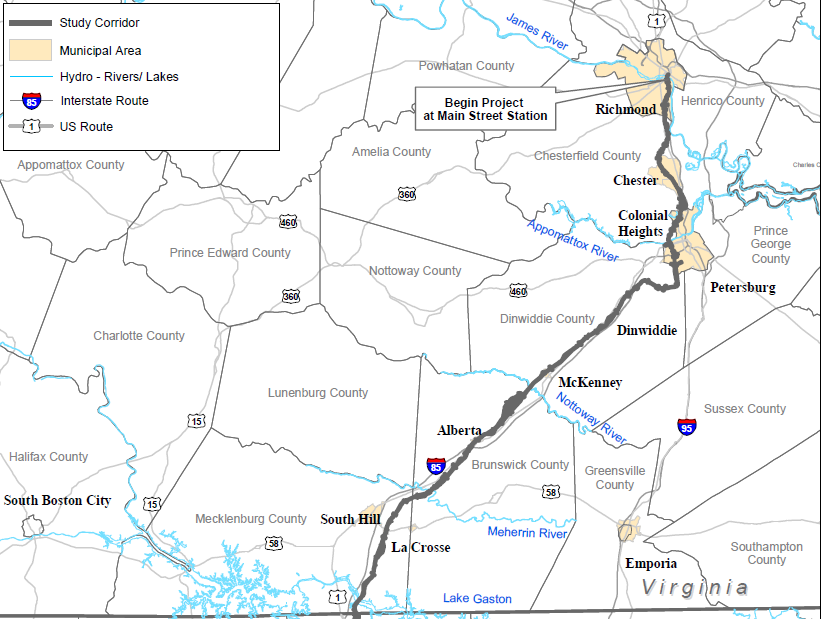

Plans to extend high-speed rail to Raleigh involve reopening the CSX "S" line south of Petersburg from Collier Yard to Norlina, NC, parallel to I-85 and crossing Lake Gaston just east of the interstate's bridge. Routing high-speed rail through Danville would provide even faster trips between Atlanta-Washington, but that would bypass the Raleigh-Durham population center in North Carolina.

rebuilding the "S" line of the CSX railroad (corridor with green dots) would provide a direct route between Petersburg-Raleigh, eliminating the dogleg through Selma, NC

Source: Federal Railroad Administration, Corridor Map: Charlotte, NC to Washington, DC

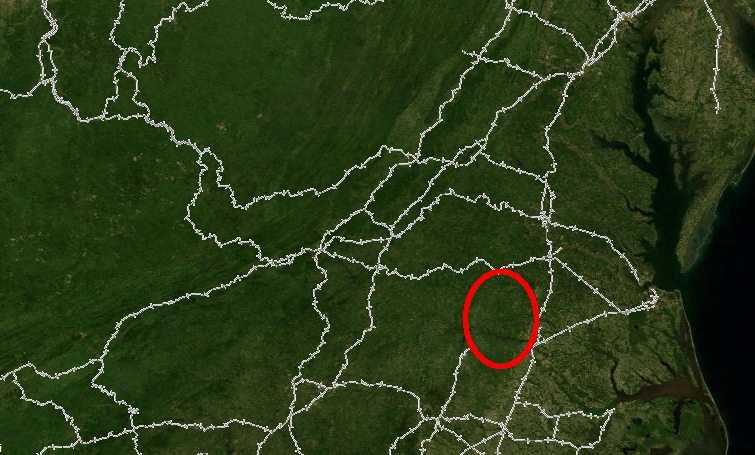

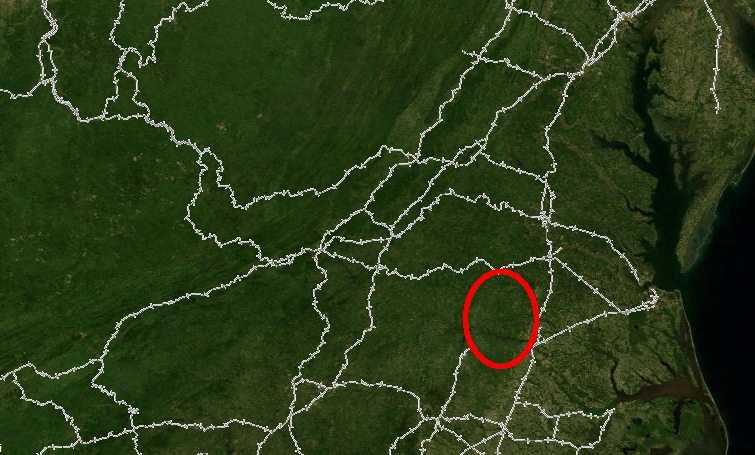

The "S" Line was once the mainline of the Seaboard Air Line. It became surplus after the Atlantic Coast Line was incorporated into CSX, and the ACL's "A" line offered a straighter path south towards Florida. The "S" line rails between Petersburg-Ridgeway were removed in 1987. The right-of-way was still owned by the railroad, but in 2019, CSX agreed to sell it. Virginia would acquire the 65 miles of right-of-way between Petersburg and the state line, and North Carolina would acquire approximately 10 miles between the state line and Ridgeway.

In 2020, the state of North Carolina got a Federal grant to buy the Raleigh-Ridgeway section. The tracks were still in place, but CSX considered them to be under-utilized.

much of the Seaboard Air Line's "S" line in Virginia was abandoned (inside red circle) because the Atlantic Coast Line's "A" line offered freight traffic a more-direct path between Florida and New York

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), National Map

Using the "S Line" route significantly reduced the time for high-speed passenger trains to travel between Petersburg and Raleigh. It would provide a straighter route to the capital of North Carolina, eliminating the extra distance used by traveling south to Selma, North Carolina and then west to Raleigh. The abandoned railbed could be rebuilt to meet the standards required to bypass the limits imposed by the geometry of existing track and nearby development, which would limit trains to 90-110mph.10

the Seaboard Air Line's "S Line" was abandoned by CSX and rails removed in 1987

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

North Carolina may have to commit much of the funding for building a new "S" Line because Virginia politicians consider that stretch to be low priority. The proposed high-speed corridor from Petersburg to the North Carolina border runs through an area with low population density. If high-speed rail service is ever implemented to Raleigh, the fast passenger trains will not stop in Virginia at Alberta (on the existing line) or LaCrosse (on a rebuilt "S" Line). Virginia will focus on upgrading the CSX corridor between Petersburg-DC, which will also benefit any North Carolina residents taking trains to the northeastern US.

The 2016 General Assembly set into law the Commonwealth Transportation Board's Six Year Improvement Plan funding priorities. The Virginia legislature mandated the start of passenger rail service to Roanoke, and the addition of two more trains to Petersburg and Norfolk, before expanding passenger rail to Raleigh.11

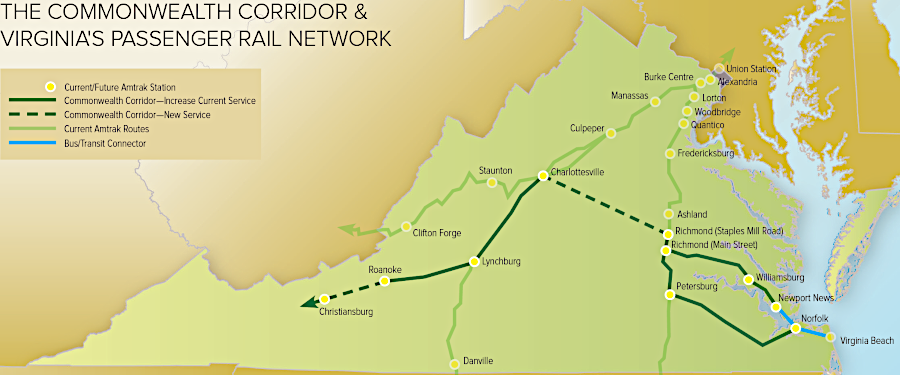

Developing high-speed rail on a route further to the west, using the Norfolk Southern tracks through Lynchburg and Danville, is an alternative to rebuilding the "S" line through a part of Virginia with few customers. A more-western route would also offer a more-direct line between Washington-Charlotte-Atlanta. However, a western route would bypass the capital of North Carolina (Raleigh) and the capital of Virginia (Richmond), providing benefits to the Piedmont but omitting the Tidewater.

In 2023, the US Department of Transportation awarded a $1 billion grant to restore passenger rail service between Richmond-Raleigh using the S-line route. That funding was limited to just North Carolina. The Virginia Passenger Rail Authority (VPRA) planning for the S-line in Virginia would not be completed until the end of 2024, and service on it was not anticipated until after 2030.12

a faster connection between Raleigh and Washington DC would benefit multiple passenger rail routes in North Carolina

Source: North Carolina Deprtment of Transportation, What is the S-Line?

Since English colonists first settled in Virginia and North Carolina, Tidewater politicians have ensured that their region would receive priority consideration for funding new transportation capacity. Like I-85, which bypasses Lynchburg, new high-speed rail improvements will be designed primarily to benefit Raleigh/Richmond more than the Piedmont or Hampton Roads.

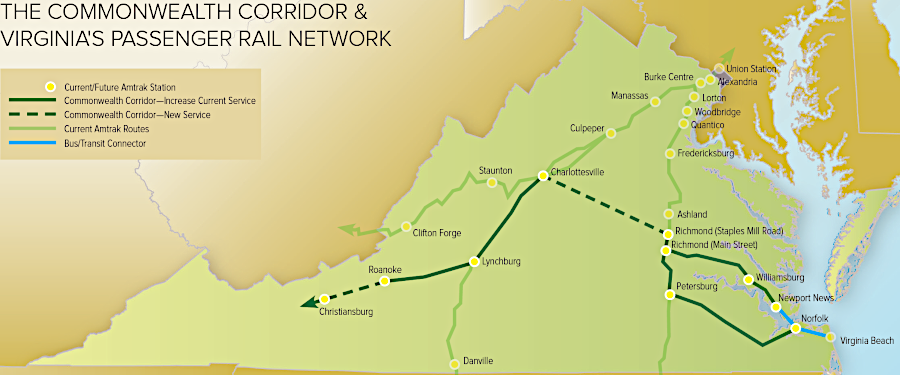

Expansion of passenger rail was proposed for east-west travel across the Piedmont, but upgrades for high-speed service were not part of the plan. Advocates pressed for new service from Norfolk to Christiansburg via Richmond, Charlottesville, and Lynchburg. As proposed by the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation in 2021, trains on the Commonwealth Corridor would run no faster than 79 miles per hour.13

as proposed in 2019, the Commonwealth Corridor would expand rail service from Virginia Beach to Christiansburg

Source: Virginians for High Speed Rail, Commonwealth Corridor

The DC to Richmond High Speed Rail Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was released in 2017. It examined multiple alternatives, including a bypass around Ashland, but recommended against it. Instead, the draft endorsed building three tracks through the center of town.

The final Environmental Impact Statement selected the alternative to "Maintain Two Tracks Through Town (No Station Improvements), Add a Third Main Track North and South of Town." The two existing tracks through town would be improved within the existing railroad right-of-way. A third track would be constructed on either side of Ashland, but within the town there would be only two tracks.14

Links

References

1. Robert E. Gallamore, John Robert Meyer, American Railroads, Harvard University Press, 2014, pp.103-104, https://books.google.com/books?id=Iov5AwAAQBAJ; Christian Wolmar, The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America, Public Affairs, 2013, p.334, https://books.google.com/books?id=O9QiBQAAQBAJ (last checked March 25, 2016)

2. "Frequently Asked Questions," Tier II Environmental Impact Statement, Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor, http://www.sehsr.org/faq.html; "The Feds Put the Brakes on High-Speed Trains," Streamliner Memories, October 21, 2012, http://streamlinermemories.info/?p=358 (last checked August 31, 2013)

3. "TurboTrain at Petersburg, Va., 1971," Amtrak, http://history.amtrak.com/archives/turbotrain-at-petersburg-va.-1971; "Metroliner Service train on the Northeast Corridor, 1970s," Amtrak, http://history.amtrak.com/archives/i-metroliner-service-i-train-on-the-northeast-corridor-1970s; "2000s--America's Railroad," Amtrak, http://history.amtrak.com/amtraks-history/2000s; "Digging into the Archives: Introducing Amfleet," Amtrak, October 9, 2012, http://history.amtrak.com/blogs/blog/digging-into-the-archives-introducing-amfleet (last checked March 24, 2016)

4. "Virginia transportation officials visit areas in Hanover that could be affected by high-speed rail," Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 1, 2016, http://www.richmond.com/news/local/ashland/article_86f7b4a0-e419-5167-8d40-24edb887ba4b.html; "Editorial: Project could bring rail improvements," Free Lance-Star, December 22, 2016, http://www.fredericksburg.com/opinion/editorials/editorial-project-could-bring-rail-improvements/article_c2c89dc9-321e-5a29-a89a-832b5a485e69.html (last checked December 22, 2016)

5. "Record Of Decision For The Tier I Southeast High Speed Rail Project," Federal Railroad Administration/Federal Highway Administration, November 20, 2002, pp.1-2, http://www.sehsr.org/reports/RODFinal.pdf; "Richmond to South Hampton Roads High-Speed Rail Feasibility Study: Task 1 Report - Engineering Feasibility Study," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, May 2002, p.4, pp.32-33, http://www.drpt.virginia.gov/studies/files/SHREngineering-Task1.pdf (last checked August 31, 2013)

6. "Elder Statesman," Henrico Monthly, April, 2013, http://www.henricomonthly.com/interview/elder-statesman (last checked December 21, 2016)

7. "The Case For Virginia's Regional Trains: The Foundation for the Future," Virginians for High Speed Rail, December 2013, p.3, http://www.vhsr.com/system/files/VARegionalReport.pdf (last checked December 19, 2013)

8. "Recommendation Report, Southeast High Speed Rail Richmond, VA, to Raleigh, NC Tier II Environmental Impact Statement," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) and the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) Rail Division, p.2, April 2012, http://www.sehsr.org/pdf/Report.pdf; "Frequently Asked Questions," Tier II Environmental Impact Statement, Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor, http://www.sehsr.org/faq.html (last checked August 31, 2013)

9. "Record of Decision," Federal Railroad Administration and Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, September 5, 2019, p.14,

http://dc2rvarail.com/files/3115/6803/2848/DC2RVA_ROD_05Sept2019.pdf (last checked September 11, 2019)

10. "Recommendation Report, Southeast High Speed Rail Richmond, VA, to Raleigh, NC Tier II Environmental Impact Statement," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) and the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) Rail Division, p.16, April 2012, http://www.sehsr.org/pdf/Report.pdf; "Seaboard Air Line - the 'S' Line," Rails in Virginia website, http://members.trainorders.com/varailfan/abandoned/seaboard.html; "NC gets federal grant to buy corridor for Raleigh-Richmond high-speed rail," The News & Observer, September 18, 2020, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/article245841010.html (last checked September 21, 2020)

11. "2016 General Assembly Update," Spring 2016 Newsletter, Virginians for High Speed Rail, http://www.vhsr.com/sites/default/files/2016-04/VHSR%20Spring%202016%20Newsletter%20Online.pdf (last checked December 21, 2016)

12. "U.S. grants $1 billion toward Richmond-Raleigh passenger train route," Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 7, 2023, https://richmond.com/news/state-regional/government-politics/u-s-grants-1-billion-toward-richmond-raleigh-passenger-train-route/article_b1a52170-9497-11ee-8af5-87d3a78f66dd.html; "Virginia's railways are getting an upgrade," Virginia Public Media, December 21, 2023, https://www.vpm.org/news/2023-12-21/virginia-passenger-rail-authority-amtrak-trains-dc-richmond-raleigh (last checked December 22, 2023)

13. "Virginia is planning an east-west rail route connecting the Blue Ridge Mountains to the beach," Greater Greater Washington blog, October 16, 2019, https://ggwash.org/view/74274/commonwealth-corridor-rail-route-may-run-from-the-blue-ridge-mountains-to-beach; "2021 Commonwealth Corridor Feasibility Study," Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, 2021, p.5, https://www.drpt.virginia.gov/media/3646/commonwealth-corridor-study-final.pdf (last checked May 25, 2022)

14. "Record of Decision, DC to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail," Federal Railroad Administration and Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation, September 5, 2019, p.19, https://dc2rvarail.com/files/3115/6803/2848/DC2RVA_ROD_05Sept2019.pdf (last checked May 25, 2022)

high-speed rail through Southside Virginia would parallel I-85, not I-95, since the priority for passenger rail is to link Richmond with Raleigh, Charlotte and Atlanta

Source: Southeast High Speed Rail (SEHSR) Tier II Draft Environmental Impact Statement, SEHSR Tier II Study Corridor Map

Railroads of Virginia

Virginia Places