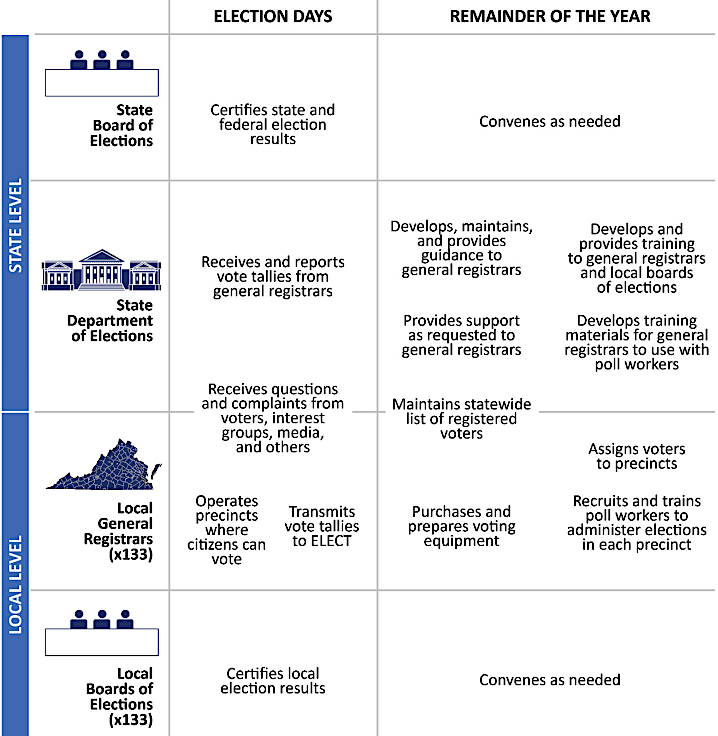

Virginia has a locally administered, state-supervised electoral system with four key entities

Source: Joint Legislative and Advisory Committee (JLARC), Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Figure 1-1)

Virginia has a locally administered, state-supervised electoral system with four key entities

Source: Joint Legislative and Advisory Committee (JLARC), Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Figure 1-1)

In Virginia, General Registrars and Electoral Boards administer elections in 133 jurisdictions. They organize the ballot, recruit officers of election (election officers), obtain suitable polling places, distribute ballots, and compile results. Election integrity procedures are well-defined for election officers.

Registrars recruit members from both the Republican and Democratic parties, plus non-aligned individuals, so each precinct has a bipartisan balance of officials. Registrars seek to have the top two officials at each precinct represent different political parties, so management is bipartisan and the voting process will be perceived as fair and transparent.

At least three people are required to staff a precinct. In the June 2024 primary, there were 2,535 voting precincts in Virginia. That required a minimum of 7,605 people to manage the places where people voted in person.

The Virginia Department of Elections (ELECT) issues requirements and guidance for local election officers. The state agency also manages the Virginia Election and Registration Information System (VERIS), which publicizes results on a website. Local officials manage the voting procedures and generate the results, which are delivered to the state for public release. Though local officials certify local results, the State Board of Elections certifies final official results. The one exception: recounts processed by Circuit Court judges are certified by the Recount Court.

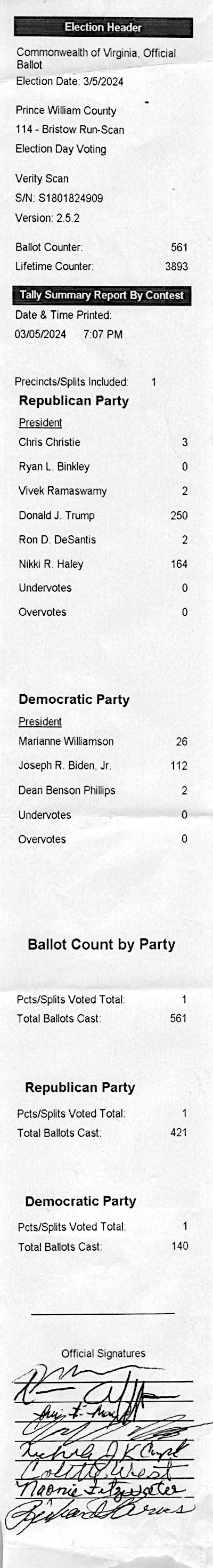

On election day, polls are open between 6:00am-7:00pm. Prior to the polls opening, a test decks of ballots with names of candidates for the upcoming election is processed through each voting machine to ensure it will report results correctly. After Logic and Accuracy testing, the test votes are deleted. In Prince William County, testing the machines for 103 precincts before each election requires days of work by the elections office staff.

Before the polls open at 6:00am, election officers at each precinct trigger each scanner to create a Zero Tape that documents there are no pre-recorded votes in the machine.

If there are problems with the voting machines or ballots have been misprinted, voters are directed to another machine. A machine from the reserve supply may be brought to the precinct. In some cases, a precinct may open late or even close for a portion of the day; voters must wait or come back later.

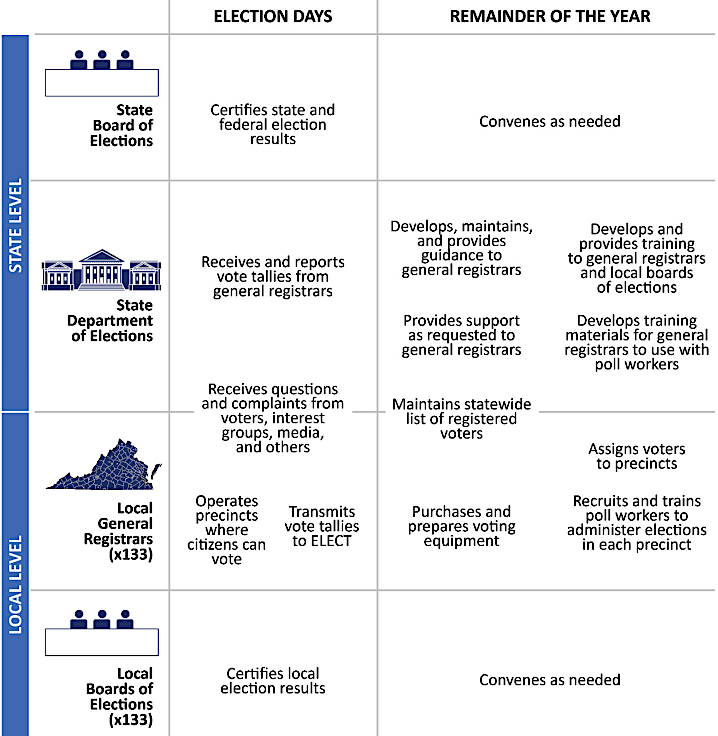

Voters who go to the polls on election day will show identification, be recorded in the pollbook, and given a paper ballot. People who registered to vote but went to the wrong precinct will not be in the pollbook. They will be directed to the correct precinct, where they can get a ballot for the candidates in their geographic district. The "wrong" precinct will not have ballots for all the other precincts; voters must go to their assigned precinct on election day.

voters are assigned to precincts with defined geographic boundaries, and ballots distributed at precincts reflect the candidates for specific offices

Source: Prince William County Office o4

f Elections, Election District Map

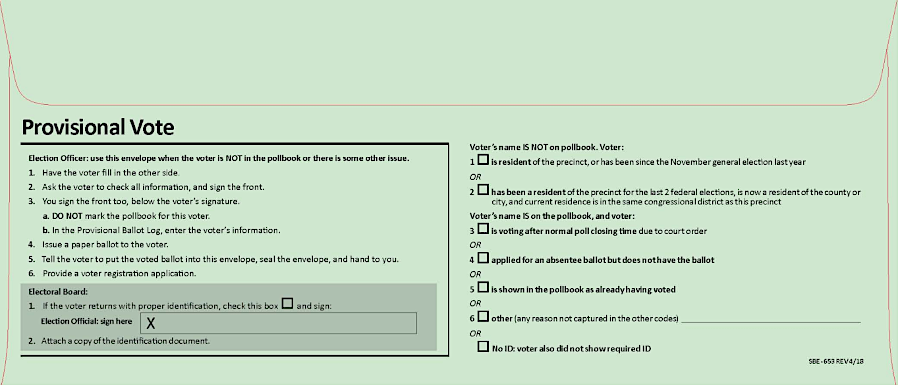

Potential voters whose names are not listed in the pollbook, but who are qualified to register in that precinct, were allowed to complete the registration process on voting day starting in 2022. After registering, they will be given a provisional ballot.

The names of voters who appear in person at a precinct on election day are recorded in the pollbook, so they can only vote once. If they had requested an absentee ballot, they must turn it in for disposal at the precinct or must vote a provisional ballot on election day. That provisional ballot will be counted only if no absentee ballot has been submitted, a step that prevents voting twice.

After the pollbook check in, voters go to a booth where they mark their preferences on a paper ballot. The voter's last step is to walk over to a scanner and run the ballot through it. If the voter has marked too many squares on a ballot, such as voting for two candidates for Governor, the scanner will reject the "overvote" ballot. The voter can go to an election officer and get a replacement ballot and complete the process, while the old ballot will be officially "spoiled" so it is not counted.

If a voter forgets or chooses not to make a selection for a particular race, in what is called an "undervote," the ballot will be processed by the scanner. Once a ballot is processed, there is no opportunity for a voter to retrieve the ballot and fill in any missing blanks.

When a vote is recorded by the scanner, a flag appears on screen to notify the voter. The paper ballot drops into a box in a locked cabinet beneath the scanner in case a recount is required, and a poll worker gives the voter a sticker to advertise their participation in the process. Everyone standing in line at 7:00pm when the polls close is allowed to vote.

After all voting is completed, election officials close the polls. The program on the scanners is run at each precinct to tabulate the votes. At the end of voting, the Results Tape from each machine reveals the totals that reflect preferences of the voters using each machine. At the precincts, election officials complete a Statement of Results worksheet with vote totals and submit it to the Electoral Board at election headquarters.

The Electoral Board meets in private to determine the qualifications of those who cast provisional votes, such as voters who had requested a mail-in ballot but chose instead to vote in person. If the voter fails to provide their unused mailed ballot to the precinct official when they come to vote in person, the voter must fill out a provisional ballot. That step prevents people from voting twice.

Provisional ballots start to get counted starting the day after the election, so those votes are not included in the preliminary election night results. In some cases voters must deliver necessary documentation of their qualifications. The deadline for their provisional ballot to be counted is 5:00pm on the seventh day following the election.

Ballots postmarked on or before Election Day, and delivered by the post office by noon on the Friday after election day (or Monday, if Friday is a holiday when mail is not delivered), also are counted after election day.

The US Postal Service knows that it faces a "beat the clock" challenge. Creation of the Juneteenth holiday causes a backlog of mail that impacts delivery of mail-in ballots for June primaries. In 2024, Arlington election officials received 200 valid mail-in ballots at 3:00pm on Friday, June 21. None of those votes were counted, because they arrived after the noon deadline established by the General Assembly.

In the 2023 General Election, election officials processed 15,981 same-day registrants and 25,926 provisional ballots. In 2024, a presidential election year, there were 84,522 same-day registrants and 122,494 provisional ballots. Communities with universities had parrticularly high numbers of voters who registered on Election Day, adding to the workload of the elections staff with a deadline to finish counting all the votes by 10 days after Election Day.

In Radford, home of Radford University, 472 people registered to vote on November 5, 2024. That was more than all registrations in 2024 prior to Election Day. Montgomery County, home of Virginia Tech, had 3,844 Election Day registrants in 2024. The only two jurisdictions with more last-minute voters were Fairfax County (10,438 registrants) and Prince William County (5,101 registrants), both of which have far higher total populations that Montgomery County.

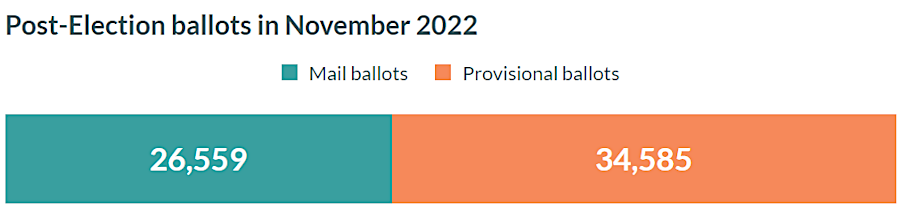

Mailed-in and provisional ballots may alter preliminary results. Preliminary results announced on election night in November 2022 had a George Mason University student six votes behind another candidate for Fairfax City Council. Of the remaining 172 additional ballots, the student won a clear majority and ended up as the winner. In the November 5, 2024 election for mayor of Roanoke, Republican candidate David Bowers was ahead by 19 votes on the night of the election. When provisional and late-arriving mail ballots were counted, however, Democratic candidate Joe Cobb was the winner by 59 votes in a 15,221-15,162 final total.

In the last stage of counting, the Electoral Board holds a public meeting known as the "canvass." In the canvass, election officials consolidate results from the individual precincts. Candidates may have observers with an unobstructed view of the officials tabulating the votes. The Electoral Board completes the process by "certifying" final vote totals.

The procedures for elections are defined in the Code of Virginia and guidance from the Virginia Board of Elections. There are provisions for different circumstances, designed to minimize the risk of voter fraud while facilitating a person's right to vote. For example, if a person is at least 65 years old or disabled but can get to their precinct's voting place, two election officials will carry a paper ballot out to a car.

The significance of a paper ballot was emphasized by Gov. Glenn Youngkin in advance of the November 2024 election. Even before early voting started on September 20, former President Donald Trump was already raising concerns about election integrity and the legitimacy of the ultimate decision. Gov. Youngkin sought to assuage concerns and he traveled across Virginia to energize Republicans to vote early.

After telling voters in Bedford County that "we've got to blow it out in our red counties" to offset Democratic voters in urban areas and Northern Virginia, Governor Youngkin said:1

Virginia elections are decided by the plurality of voters. In the "first past the post" process, the candidate receiving the most votes is declared the winner even if their total is less than a 50% majority.

For a brief period, Virginia required candidates to win a majority. After World War II, returning veterans were less likely to vote for candidates preferred by Senator Harry Byrd and his "organization." In the 1949 Democratic primary for Governor, the opposition to Byrd's candidate was far more than just token. Francis Pickens Miller came close to defeating Byrd's preference, John Battle. Battle ended up with 43% to Miller's 35%, but Senator Byrd had to get more engaged than usual to ensure the victory.

To ensure organization candidates would win future primaries, the General Assembly changed the rules to require a two-person runoff if no candidate earned 50% of the vote.

After the initial Democratic primaries in 1969, no candidate for Governor or Attorney General earned at least 50%. That result required that two runoff elections be held to select nominees. In both races the Byrd-supported candidate won the runoff, but it was clear that the Byrd Organization could no longer rely upon the Democratic Party nomination process to choose conservative candidates.

In 1970, Senator Harry Byrd Jr. (who had been appointed to his father's seat) chose to completely bypass the partisan primary and run as an independent. His Democratic opponent won that party's primary by just 700 votes, with only 46% of the total. The runner-up with 45% of the vote was entitled to ask for a runoff election, by declined the opportunity. In the three-way race in November 1970 between Republican, Democratic, and Independent candidates, Senator Harry Byrd Jr. won a solid majority with 53% of the total votes. His Democratic and Republican opponents split the remaining 47% between them.

The General Assembly then changed the rules again. The legislature eliminated the requirement for a candidate to win at least 50% of the vote, and thus eliminated the runoff process in Virginia.

In other states, candidates still must receive over 50% or the total vote (a "majority") to win. If those states, if there are three or more candidates and no one receives a majority, a runoff election is required to decide the winner.

In 2020, the General Assembly re-established the potential for a runoff election if there is a tie vote for a US House of Representatives or General Assembly seat, for the US Senate, or for a local office. The law recreating the need for a runoff election was passed after a tie vote for a House of Delegates seat in 2019 was broken by pulling the winner's name from a bowl.

In 2020, the General Assembly authorized Arlington County to experiment with ranked choice voting for County Board races. In that process, voters rank their preferences on the ballot. If no one receives 50% of the vote, then votes for the lowest-ranked candidate are eliminated and the second-ranked preference on those ballots is counted.

If there were only three candidates, then one of the remaining two will get over 50%. The winner might have received fewer "first place" votes, but scored a majority of the "second place" votes for the eliminated candidate. If there were more than three candidates on the ballot and redistribution of votes does not give anyone 50%, then the lowest-ranked remaining candidate is eliminated and his/her second-place votes are redistributed.

Ranked choice voting guarantees that the ultimate winner will have received a majority of votes. It provides an instant-runoff, without the delays and costs to hold a second election to pick a winner.

Ranked choice voting also allows voters to initially choose a third-party candidate, with less concern that they are wasting their vote. If, for example, 10% of voters prefer a third-party candidate while the Republicans and Democrats split the remainder, then the first reports after the election will show a 45-45-10% split. Under a ranked choice process, the ballots for the third party candidate will be recalculated, counting the second-ranked preference. If 80% of those ballots listed the Republican candidate as the second preference and 20% preferred the Democratic candidate, then the final vote would have 53% for the Republican and 47% for the Democrat.

The Arlington Democratic Party started using the process to nominate candidates for County Board and School Board elections in 2020. None of the nominees for each race that year won 50% of the vote on the first round. In a plurality process, had come in second in the initial vote, but no one had won a majority exceeding 50%. When the second-ranked

Arlington had to upgrade its voting software in order to calculate votes for more than three candidates. The county had to prepare for the possibility that four or more candidates would appear on the ballot, so it did not use ranked choice voting in 2020. The following year the General Assembly authorized all local jurisdictions to adopt ranked choice voting for county supervisor and city council races for 10 years, starting in 2021.2

Voting procedures have a long, and not always honorable, history. Policies and standard operating procedures have been developed over time to address voter fraud (especially for absentee voting) and voter intimidation.

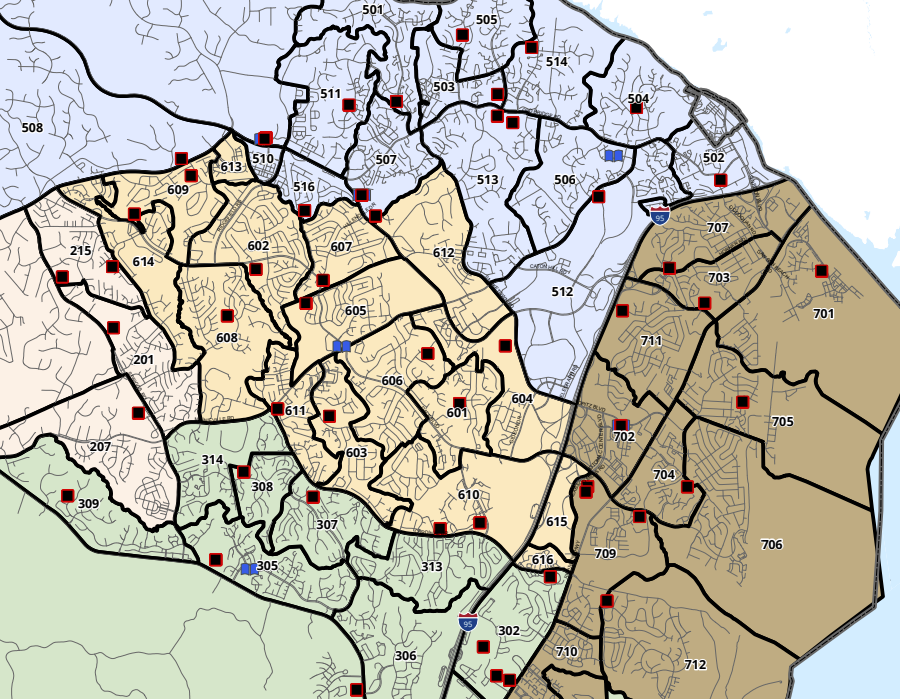

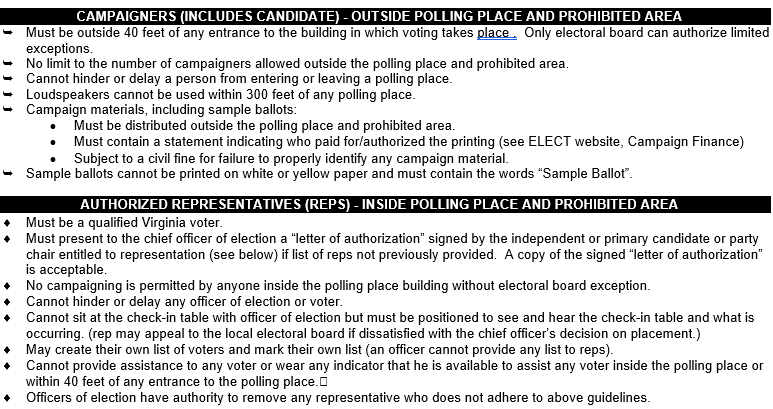

campaigning is restricted at polling places, including limits on loudspeakers

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Guidelines for Campaigners and Authorized Representatives

In 1883, a supposed "riot" in Danville was publicized by Democrats as a sign that African-Americans were demanding social and economic equality, beyond the right to vote. The Democrats won control of the General Assembly in that election. After losing the race for governor in 1885, the Readjuster Party dissolved.3

Democrats consolidated control of the state. After passing the Anderson-McCormick Act in 1884, the General Assembly changed the voting procedures and appointed three-member electoral boards for each local jurisdiction. Those election officials facilitated election tampering and voter suppression so Democratic candidates gained an unfair advantage.4

Virginia became part of the Solid South where the capacity of Republicans to be elected was low. White voters remembered that Republicans controlled the Federal government during the Civil War and Reconstruction, and were reportedly willing to vote even for a yellow dog so long as it was a Democrat.

Voting by blacks was constrained through official procedures and unofficial intimidation, minimizing their ability to participate in the political process. However, John Mercer Langston ran as a Republican and managed to win election to the US Congress in 1888. The election of Virginia's first black US representative was disputed in the US Congress, and the seat was left empty for over a year.

Mercer served only the last seven months of his two-year term. It was not until 1993 that Virginia elected its second African-American (Rep. Bobby Scott) to Congress. After 1891, no people of color served in the General Assembly until after passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In 1968, Dr. William Ferguson Reid was elected from Richmond to serve in the House of Delegates.

The first black man to be elected to the State Senate in modern times was L. Douglas Wilder, in 1970. He became the first person of color to be elected to statewide office as Lieutenant Governor in 1985, and then was elected Governor in 1989. In the 1985 election, Mary Sue Terry became the first and only woman to be elected to a statewide office when she won the race for Attorney General.5

After the 1902 state constitution disfranchised most African-American voters in Virginia, only the "Fighting Ninth" District for the US House of Representatives in southwestern Virginia remained competitive for Republicans. There were few black voters in that corner of Virginia, but throughout the 1800's the white residents had resented how the General Assembly and governor directed state revenues to benefit primarily the area east of the Blue Ridge. Southwestern Virginia and eastern Tennessee residents had little enthusiasm for secession and fighting for slavery during the Civil War, and because of the independent voters some Republicans continued to win elections there.

To enhance prospects in Virginia, Rep. C. Bascom Slemp from the 9th District led the "lily white" movement in Virginia's Republican Party. It excluded African-Americans from voting in the statewide convention in 1920, and in 1921 the Republican Party even banned African-Americans from the visitor's gallery. In response to the shunning by Republicans, a convention of 600 black delegates in 1921 nominated an independent ticket for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, superintendent of public instruction, treasurer, secretary of the commonwealth, State Corporation Council commissioner, and commissioner of agriculture. All the candidates were black.6

The Democratic Party maintained full control of state government until 1969. Key contests occurred in the Democratic primaries rather than in the general elections, and winning the Democratic Party primary ensured election. Between the 1920's-1960, Harry Byrd served first as governor and then as US Senator, and his Democratic Party "organization" controlled the General Assembly.

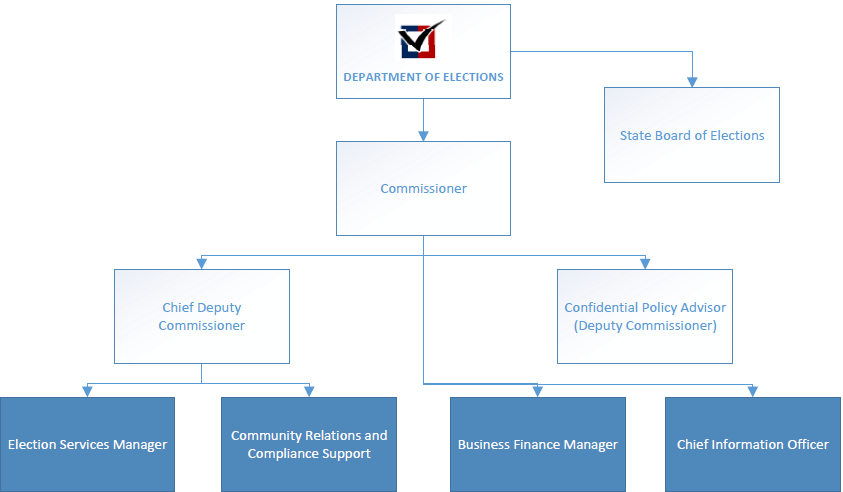

In 1946, the General Assembly created a State Board of Elections to oversee the work performed by city and county registrars and to ensure uniform application of the state's election laws and procedures. The new agency assumed responsibilities from the Secretary of the Commonwealth and the Board of State Canvassers. In 2014, the Department of Elections was created to manage the administrative work, including maintenance of a statewide automated voter registration system.

The State Board of Elections retained its regulatory responsibilities, and makes final decisions regarding election disputes. The governor appoints the five-member board, subject to State Senate confirmation. Three members must represent the party that won the most recent race for Governor and two members represent the other party.

Terms of appointees to the State Board of Elections are staggered; all five do not expire at the start of a new Governor's term. A new governor's appointees to the State Board of Elections do not alter the partisan balance until two years after an election, but at the start of his/her term the Governor can appoint a new Commissioner to lead the Virginia Department of Elections.

In 2024, the House of Delegates approved a bill by a 99-0 vote to authorize the State Board of Elections to appoint the commissioner, rather than the governor. The intent was to make the position less subject to partisan influence. HB 742 died in an 8-7 vote in the Senate Privileges and Elections Committee.

All Democrats on the committee opposed the bill because it required a supermajority vote to hire/fire the commissioner. The Democrats argued that requiring four of the five members to make a decision, guaranteeing a bipartisan vote, could result in gridlock. Just two members could block action by the majority of three members. The partisan vote may have reflected an expectation that in the future, Democrats would elect most governors. Those governors would appoint three members to the State Board of Elections, and Republicans in the minority should not be empowered to block action of the majority.

The Department of Elections (ELECT) is intended to be a professional, non-partisan agency responsible for ensuring the election process is free and fair. It maintains the statewide registration system known as Virginia Election and Registration Information System (VERIS). The database has about 5.5 million voters, with changes made daily as new voters register or existing voters are removed for various reasons. The state agency delivers electronic absentee ballots to eligible military and overseas voters, helps local election officials follow established procedures and ensures election integrity.

By its very nature, the State Board of Elections is a partisan oversight body with a board and commissioner appointed by an elected official. Politics may tilt the actions of the executive agency, including decisions regarding the eligibility of candidates who must file state-required forms to qualify for the ballot.

A 2018 report by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) concluded that the voter rolls were mostly accurate, but under Governor Terry McAuliffe in the Virginia Department of Elections:7

the State Board of Elections is the regulatory body, while the Department of Elections administers elections

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Elections' Organizational Chart

In the middle of the 20th Century, Virginia's electorate appeared schizophrenic to outsiders. As the national Republican Party became more conservative and the national Democratic Party became more liberal, Virginia voted for Republican presidential candidates in Federal elections but for Democrats in state/local elections.

Federal legislation and court rulings in the 1960's expanded the electorate, allowing minorities an opportunity to vote and win elections. New legislative districts were drawn in 1965 to comply with "one person-one vote" decisions by state and Federal courts.

Rep. Howard W. Smith had been elected nine times in the 8th Congressional District and had risen to become chair of the House Rules Committee, but in 1966 the more-liberal George W. Rawlings defeated Rep. Smith in the Democratic primary. Many conservative Democrats did not support Rawlings in the general election, and the Republican candidate (William Scott) defeated Rawlings. That led to more Republican victories in Northern Virginia for the next three decades.

In 1969, Republican Linwood Holton won the governor's office as the more-liberal candidate in the race. In 1973, the Virginia parties finally aligned with their national counterparts. The state Democratic Party shifted to the left, and Virginia Republicans became the conservative alternative.

After 2000, demographic changes helped make Northern Virginia a stronghold for liberal Democrats. Former Rep. Tom Davis, the last Republican elected to the US House of Representatives in Northern Virginia, emphasized that the shift occurred because his political party had advocated for social issues that resonated in rural areas (such as gun rights) but not addressed concerns of suburban voters. Republicans lost support as those suburban voters, particularly women, became a greater percentage of the electorate.

Del. Tim Hugo was the last Republican from Fairfax County and one of the last in all of Northern Virginia serving in the House of Delegates, after a "blue wave" of Democratic victories in 2017. During Hugo's unsuccessful 2019 campaign to retain the 40th District seat, he minimized his status as a Republican and referred to himself as a "Delegate Pothole" focused on local issues and constituent services. His opponent was clear in defining himself as a Democrat, and that helped him flip the seat in 2019.

Across the state, Democrats increased their majorities in suburban districts as the electorate migrated away from the Republican Party's conservative agenda on social issues. Tom Davis commented before the election:8

in 2019, the Republican candidate for the 40th District minimized his association with the Republican Party - while his Democratic opponent did the opposite

Source: Tim Hugo - Delegate and Dan Helmer - Democrat for Delegate

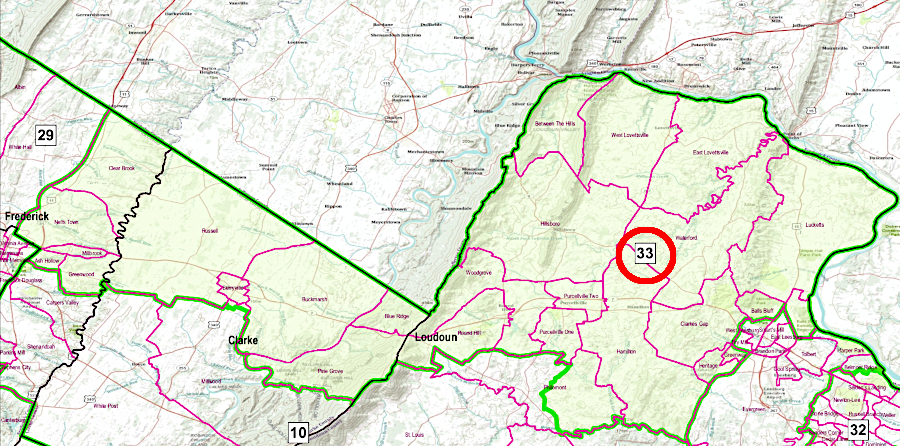

Hugo did lose the race, as did the Republican candidate in the 13th State Senate district. After 2019, there was only one Republican left in the General Assembly representing a district in Northern Virginia north of the Occoquan River. The day after Rep. Dave LaRock was re-elected to the House of Delegates from the 33rd District, he commented:9

after the 2019 election, the only Republican in the General Assembly from north of the Occoquan River represented the 33rd District"

Source: Virginia General Assembly, 33rd House District

Today in Northern Virginia and several cities, victory in the Democratic primary became tantamount to election. In 2003, the race for the District 49 seat in the Virginia House of Delegates attracted so little interest that Adam Ebbin won the primary with just 771 votes, then ran unopposed in the general election to become the first openly gay member of the General Assembly.

Political analyst and scholar Larry Sabato noted:10

in the 2003 primary, the candidate for the District 49 seat in the House of Delegates won with just 771 votes

Source: Virginia State Board of Elections, 2003 House of Delegates Democratic Primary - District 49

A single voter's decision occasionally determines who wins a race. In 1991, "Landslide Jim" Scott won the 53rd District seat in the House of Delegates by one vote. That same year, Peter T. Way won the race in the 58th District by the same narrow margin. Races can also end in a tie, after which the winner is chosen "by lot" rather than in a runoff election.11

suffragists who protested at the White House were jailed and force-fed at the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, before women gained the right to vote in 1920 after ratification of the 19th Amendment

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Women's Suffrage Parade, 1917

In Virginia, high school students as young as 16 can register. They must be 18 on the day of an election in order to vote. At the polling place, personal identification is required to verify a voter's identity. However, there is no need to bring the official voter registration card. Registrars mail those cards to registered voters just as a convenience.

Potential voters can register in advance on a state-run website, at their local registrar's office, or at any Department of Motor Vehicles office. Voters also can register at their polling place on the day of an election, but must go to their correct precinct. Elected officials represent defined district boundaries.

Assigning residents to the correct local, state, and Federal voting districts is the responsibility of local registrars in each county/city. Registrars assign voters to geographic areas called precincts. The voter's address determines which specific offices are appropriate for that voter to cast a ballot. Election officials at a precinct rely upon a pollbook produced by the local registrar to provide the correct ballot to a voter.

Homeless people can vote, but during registration must provide an address so they can be assigned to a specific election district. Some shelters agree to receive mail from registrars to facilitate homeless people maintaining a valid registration.

Non-government organizations such as the League of Women Voters and the NAACP conduct voter registration drives. Volunteers bring registration forms to schools, retirement homes, farmer's markets, res, and arerallies, and other events. Potential voters must fill out the form, but the volunteers can deliver the forms to the registrar's office.

State law allows "protected voters" to use a post office box rather than a physical address. Protected voters include law enforcement personnel, judges, and people who are being threatened or stalked. Starting in 2024, current or former state or local election officials are also allowed to use a PO Box as an alternate address. If the US postal Service will not deliver mail to an address, such as a homeless encampment, then those voters are also authorized to use a PO Box.12

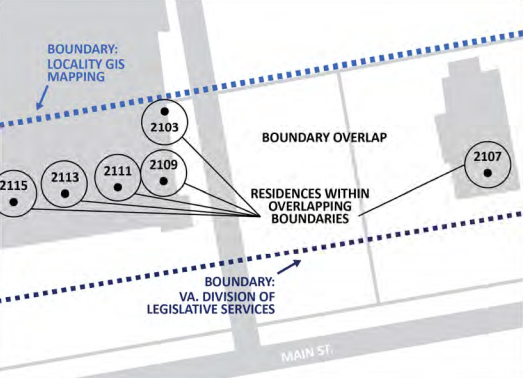

In 2017, an election in Newport News for the 94th District in the House of Delegates ended in a tie vote. The winner was decided by drawing names from a bowl.

Afterwards, it became clear that some voters had been assigned to the wrong precinct. The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission reported in 2018 that mis-assignment of voters was not unique to Newport News, in part because local registrars did not use address and boundary data consistently:13

local registrars assign voters to precincts, but state boundaries and address data may be inconsistent with local decisions

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Figure 2-13)

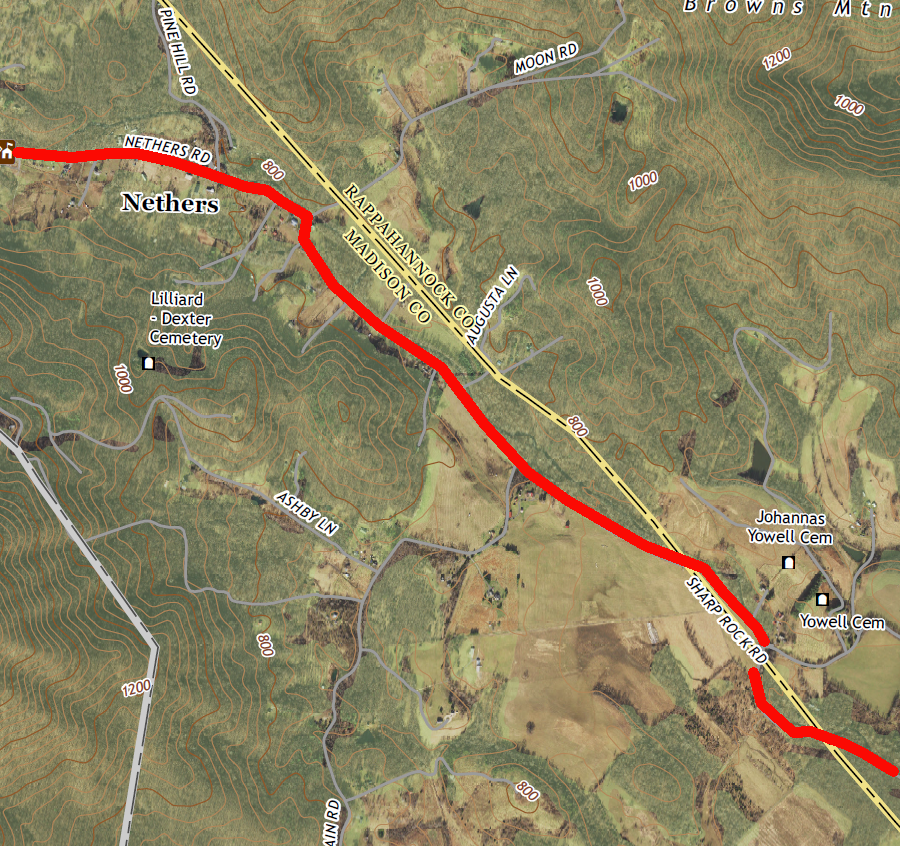

In 2022, a family living on Nethers Road, at the border of Rappahannock and Madison counties, went to vote in Sperryville as they had done for the last two decades. They were surprised to discover their names were not in the Madison County pollbook, and they should be voting in the Etlan precinct of Rappahannock County. The family had been paying real estate taxes to Madison County, but paying personal property taxes and sending children to school in Rappahannock County.

After the 2021 redistricting, the Virginia Department of Elections used its Geographic Information System (GIS) technology and identified three families that had been voting incorrectly in Madison County. They were all assigned to Rappahannock County, and the family which had appeared in Sperryville finally voted successfully in Rappahannock County.

It was later determined that they had not received notification in August of their new congressional district and voting location, because their voter registration data had used their Post Office Box in Sperryville for notifications rather than the E-911 address in Rappahannock County.14

Nethers Road snakes along the border of Rappahannock and Madison counties

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Old Rag Mountain VA 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle (2022)

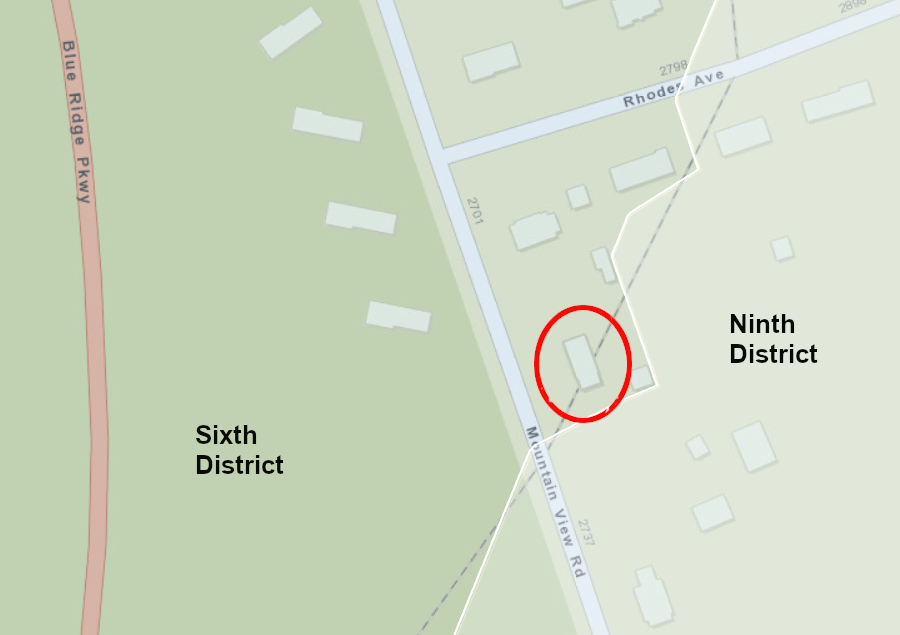

In Bedford County, one house on the Roanoke County/Bedford County boundary was placed in the Sixth Congressional District. The Census tract included the house in Roanoke County, but local officials had agreed that it should be considered to be within Bedford County and taxed by that jurisdiction.

The 2021 redistricting by the Supreme Court of Virginia used the Federal treatment and resulted in the house being the only one in the Sixth Congressional District and in Bedford County. Starting in the 2022 election cycle, Bedford County had to open a precinct for the two voters living in the one house. The unique status of that house also exposed how the two individuals living there voted, since it was possible to correlated votes reported by jurisdiction and the ownership for that house.

The Census Bureau later refined the boundaries of the census tract and placed the house back in Bedford County, but by then the Supreme Court of Virginia had formalized adoption of the 2021 redistricting map. The General Assembly had no authority to adjust the boundary of the Sixth Congressional District until the 2023 redistricting process in 2031. The Supreme Court of Virginia reacts only to lawsuits and does not revise legal decisions on its own initiative. The only way for the two residents in that house to maintain the secrecy of their future votes would be to file a lawsuit and ask the Supreme Court of Virginia to amend its redistricting decision made at the end of 2021.

The preferences of every voter in the Blackey and Oakwood districts were revealed in the 2024 presidential primaries. All 118 voters in the Republican primary cast ballots fo Donald Trump, and all six voters in the Democratic primary endorsed Joe Biden. There were just two Democratic voters in seven other precincts in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Scott counties, and just one Democratic voter at Clark's precinct in Scott County. Biden received all those votes, so anyone checking to see who voted could determined the choices made in the "secret" 2024 presidential primary ballots.15

one house in Bedford County was placed in the Sixth Congressional District, requiring a split precinct to record votes for just that house

Source: Bedford County, Congressional Boundary

A similar problem in Louisa County could be fixed by local and state officials. The county adopted new precinct boundaries after the 2021 redistricting. In error, a precinct based on the boundaries of the 56th House of Delegates District included one house that was actually in the 59th District. Local supervisors requested that the Virginia State Board of Elections adjust precinct boundaries so the recorded vote by precinct would not expose the choice made by voter in that one house.16

Simply getting people to choose to vote is a challenge for both major political parties. Elections are held every year in Virginia, with state offices on the ballot in odd-numbered years and Federal offices in even-numbered years. The presidential election every four years generates the greatest interest and the highest number of voters. The next year, in an "off year" election, Virginia elects a governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general in a statewide election.

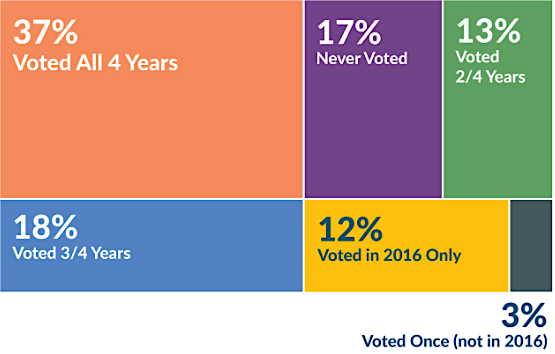

17% of voters registered in 2016 never chose to vote in an election before November 3, 2020

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), A Profile of Virginia's Registered Voters

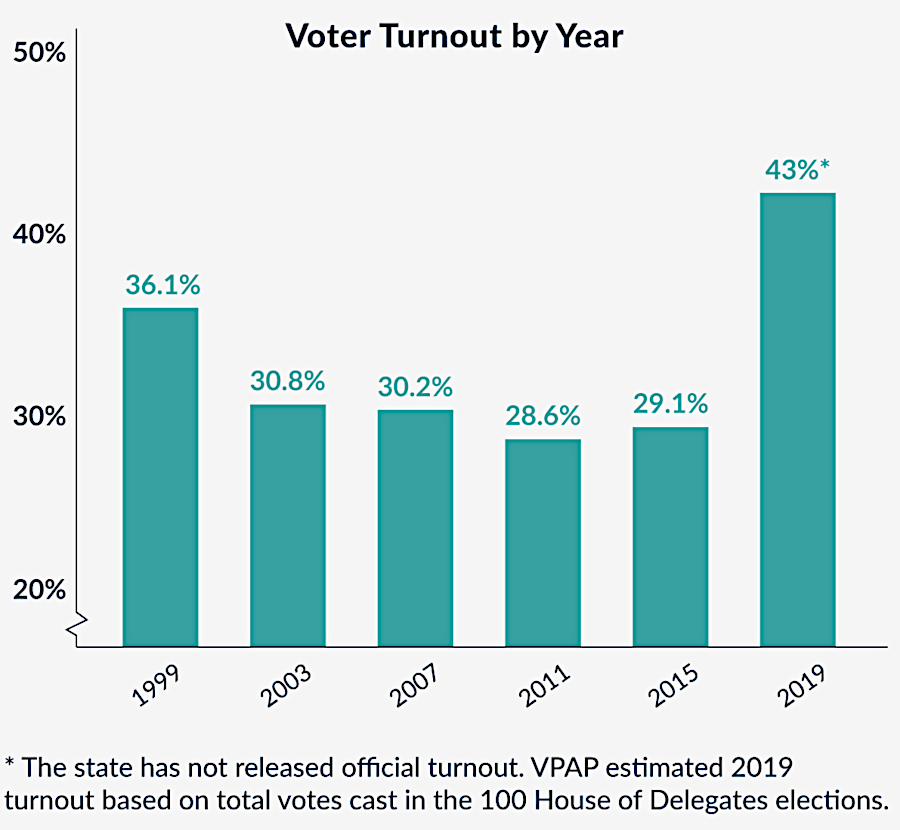

Voter participation two years later, in an "off-off year," typically has the lowest participation. Political parties always emphasize Get Out The Vote campaigns, but they have the greatest impact in off-off year elections, when there are no Federal or statewide elections. In 2015, an off-off year with races for just the House of Delegates and State Senate seats (plus some local offices), only 29% of the registered voters went to the polls.

voter turnout changes dramatically between off-off year elections and the next year when presidents are elected (in bold print)

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Registration/Turnout Reports

In 2019, as formal impeachment proceedings against President Trump were getting started, over 40% of the voters cast a ballot. That was a record turnout for an off-off year election in Virginia. In the general 2019 election, voters elected enough Democrats to replace Republicans that the majority switched in both the State Senate and the House of Delegates. Democrats gained control of the General Assembly for the first time since 1995.

In the presidential election year 2016, 72% of registered voters chose to participate in the election through absentee or in-person voting.17

2019 had record-high voter participation in an off-off year election

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Record Turnout for Off-Off Year

The 2021 General Assembly forced all municipal elections to be held in November, starting in 2022. Previously, nearly 100 cities and towns with 900,000 residents held elections in May/June for local offices, including school boards.

Choosing to hold elections separate from state/Federal races enabled candidates to get media attention, and for voters to hear about local issues. The Democratic-controlled General Assembly changed the date, assuming that turnout would be higher in the November elections and that more Democrats would vote then. Consolidating with November elections would also save some of the costs for local Electoral Boards, though state-run primaries might still be scheduled for June.

In response, several local jurisdictions considered moving their election dates to odd-numbered years. Though the General Assembly races would still be on the ballot in November, there would be less "noise" from campaigns for the US Congress and for President. The Chesapeake City Council decided in a 5-4 vote to stick with its schedule, but the Fredericksburg City Council moved its elections to odd-numbered years starting in 2022.18

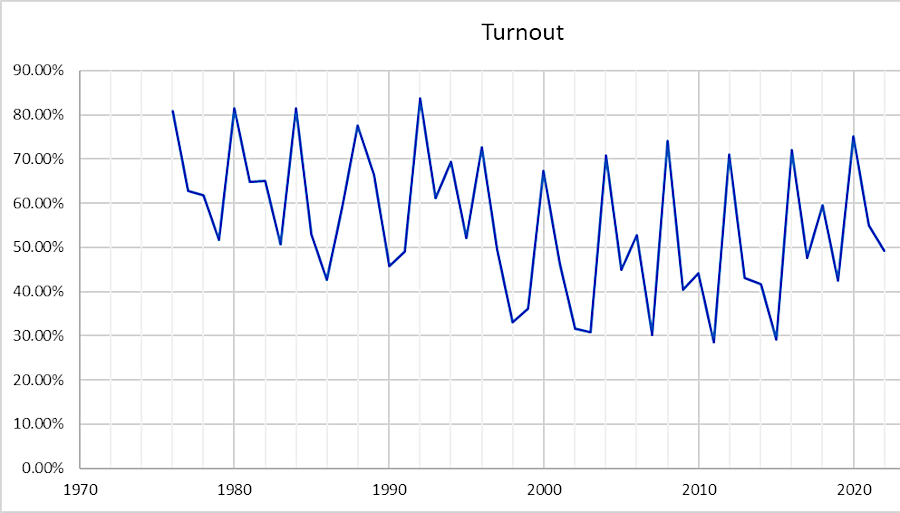

In 1976, there were 2,123,849 registered voters in Virginia. In 2022, 6,132,331 people were registered, a 189% increase. Population within that same time period increased only 70%.

Between 1976-2022, the percentage of registered voters actually casting a ballot (voter "turnout") in November elections ranged from 29% in 2011 to 84% in 1992.

turnout spikes in Federal elections during even-numbered years, especially for presidential elections

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Registration/Turnout Reports

Part of the increase in the percentage of registered voters can be attributed to the 1996 National Voter Registration Act, making it possible to register to vote when dealing with the Department of Motor Vehicles. In 1996, Virginia also stopped automatically purging registered voters if they had not cast a ballot in the last four years.

Governor McDonnell, elected in 2023, also started restoring the right to vote after convicted felons completed their prison terms. His decision, which was expanded upon by the next two governors, enabled a new class of voter to register.19

After the 2019 elections, Democrats controlled the General Assembly and the Governor was also a Democrat. They shared a common agenda to increase access to voting. They legalized no-excuse absentee ballots and 45 days of early voting, and simplified the ability to mail in ballots so people did not need to go to the polls in person. Voter identification requirements were eased.

In 2021, the General Assembly required that voters living overseas be able to cast a ballot in primary elections. That change was endorsed by both parties in order to allow Virginians serving in the military to participate in the nomination process, but had the greatest impact on the Republican Party.

Democrats already had chosen to use state-run primaries for nominating their candidates. Republicans were still using party-led conventions, canvasses and firehouse primaries. Those nomination processes allowed Republicans to exclude independents and Democrats from helping to choose Republican nominees. There was no realistic mechanism for a party-run primary to process votes from overseas, so Republicans were forced to use state-run elections for primaries. Since voters in Virginia do not register by party, there is no longer an opportunity to restrict the primary voters to just valid members of one party.

The 2020 General Assembly also approved same-day registration and voting, beginning with the 2022 General Election. The old deadline had required voters to register to vote in the correct precinct 21 days before an election.

Voters can now appear at their precinct on Election Day, show identification to prove where they live, then register and vote a special green provisional ballot. The provisional ballot is required because the name of the unregistered voter will not have been listed in the electronic pollbook at the precinct. The five jurisdictions with the highest percentage of provisional ballots in 2023, ranging from 7.3% to 0.9%, were all university communities - Williamsburg, Charlottsville, Montgomery County, Harrisonburg, and Fredericksburg.

Poll workers will place the provisional ballot in a separate ballot box and secure it until the box with provisional votes is opened the next day. After review of the ballot by the local electoral board during the post-election canvass, the three-member Electoral Board will count the vote unless there is evidence to indicate the registration is not valid.20

since 2022 voters can register on Election Day and cast a provisional ballot

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Introduction to Provisional Ballots

On election night, or soon thereafter, the Virginia Department of Elections announces unofficial voting results. Official results are not provided until after Electoral Boards complete the canvass. That includes ensuring results from precincts are correct, and counting both late-arriving mail-in ballots and provisional ballots. Some Electoral Boards may also wait to count those ballots placed in a drop box on Election Day by voters who chose not to go inside to vote in person, perhaps to avoid the wait in line.

Main-in ballots are valid if they are postmarked on or before the day of election, and arrive by noon on the third day following the election. That is typically noon on Friday after the election on Tuesday, but in some years is Monday noon because Veterans Day holiday occurred before the deadline.

The provisional ballots in green envelopes come from people who registered on Election Day, requested an absentee ballot but did not bring it to the polls to ensure there would be no double-voting, or failed to provide an acceptable form of ID.

Expanding access to the ballot required increasing staffing levels for local election officials. The state provides funding to cover the costs for just one type of primary, the presidential nominations every four years. The General Assembly provided $7 million to cover the costs of the March 2024 Republican and Democratic primaries, but local officials reported actual costs exceeded $11 million. Local jurisdictions had to absorb the unreimbursed costs.

Election costs include supplies, such as printing enough ballots in advance and obtaining needed spaces for election day. Staffing costs The registrar for the City of Norfolk outlined the impact of approving 45 days of early voting for various elections:21

mail-in and provisional ballots were 2% of the statewide total in 2022, and changed two unofficial election results announced after the polls closed on Tuesday

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), How the Post-Election Tally Works

Candidates thought to be winners of close elections on Tuesday night must wait until the canvass is completed and votes are certified before being confident they will be serving in office.

In 2022, results of elections for Fairfax City Council and mayor of the Town of Elkton flipped between Election Night and certification of the vote. In 2023, preliminary results announced on election night for a Montgomery County Board of Supervisors seat had one candidate in the lead by 43 votes. The final count, including 900 provisional ballots, switched the results. A different candidate ended up winning by 1,347-1,316, a 31-vote margin.

The canvass for the 2023 Blacksburg town council race revealed there were 662 uncounted votes, requiring a complete redo of the counting eight days after the election. The initial count had somehow missed many same-day registration provisional ballots, presumably cast by students attending Virginia Tech who had not registered prior to election day.

The canvass determined the problem and enabled the votes to be counted:22

Political parties can provide official observers to watch the canvass of all ballots. If observers disagree with judgement calls made by election officials, especially on disqualifying a provisional ballot, the political parties can ask the Circuit Court to intervene and overrule the decision.

In state-run elections, by Virgina law the candidate with the most votes ("first past the post") wins the election. Even when the winning candidate's vote total is less than 50%, which can occur in races with three or more candidates, there is no runoff election. However, a close election in Virginia may trigger a recount.

A losing candidate may petition for a court-ordered recount of votes if the winning margin was less than 1% of the total votes cast for the top two candidates. No recount is authorized for elections decided by a greater margin.

Circuit Court judges authorize recounts for local elections, including races for the 140 seats in the General Assembly. The Richmond Circuit Court has the power to order a recount in close races for the five statewide offices - two US Senators, Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General.

A recount is a judicial process overseen by three judges that form a Recount Court. The Chief Judge in the Circuit Cout which ordered the recount is joined by two other judges, who are appointed by the Chief Justice of the Viginia Supreme Court. The Recount Court appoints two members from the local electoral board as Recount Coordinators. They must be members of separate political parties. The Recount Coordinators select Recount Officials, typically local election officers, to reprocess the ballots.

The Recount Officials are organized into two-person teams, with one representing Republicans and the other representing Democrats. They run the paper ballots through scanners again. Scanners are programmed to reject ballots with write-ins, undervotes, and overvotes. Those ballots are hand-counted, according to Virginia's Guide to Hand-Counting Ballots. A representative appointed by each political party is allowed to observe the recount process, but is not allowed to physically touch ballots or election equipment.

The Recount Court may require that separate two-person teams process votes in each of a district's voting precincts, plus another team for absentee ballots. For most ballots, the two Recount Officials will agree on how to count it. Where there are disagreements, a Recount Official can challenge a ballot. The three-judge Recount Court decides how to count (and whether to reject) challenged ballots. Decisions of a Recount Court are final; no appeals are allowed.

Virginia voters mark a paper ballot which is scanned to tabulate totals, then retained in case a recount is required

Source: Arlington County, IMG_0012

The candidate requesting a recount must pay the cost of the process if the vote difference is between 0.5-1%. That is a significant deterrent for local races which did not attract outside funding, and for Congressional and statewide races. Recounts in races involving more precincts are more expensive, due to the number of officials who must be hired for a recount. A recount of the Republican primary for the 5th Congressional District in 2024, in which the vote difference was 0.6%, cost nearly $100,000.

Recounts are subsidized for very close races in which the margin of difference does not exceed 0.5%. In addition, candidates will be reimbursed for funding a recount if the initial decision certified by the local Electoral Board or State Board of Elections (SBE) is overturned. As described by the Virginia Department of Elections:23

Another option was taken by a losing candidate in a Lynchburg City Council race - seek to invalidate the results of an election via a lawsuit. In the June 20, 2024 primary, Peter Alexander lost the Republican nomination to Chris Faraldi. There was a 33-vote difference, which was a 1.6% margin and therefore not eligible for a recount. The losing candidate claimed that 125 absentee ballots had not been counted correctly.

The lawsuit was filed by the losing candidate against the winner, rather than against the electoral Board. That follows the Code of Virginia requirements, which also mandate that recount petitions be filed as private lawsuits.

It asked for the formation of a Recount Court, and for it to void the results of the primary election. If the court made such a ruling, the local Republican Party could then choose how to select its nominee for the November election. Peter Alexander, the candidate who filed the lawsuit, anticipated that the Lynchburg Republican Committee would select him.

Within a month, Alexander acknowledged that all but one of the ballots he questioned had been counted and dropped the lawsuit. The winner of the primary race, Chris Faraldi, still had to raise funds for his lawyers. He did that in part by selling merchandize emblazoned with "Live. Laugh. Lawsuit."24

in 2024, the winner of a primary for Lynchburg City Council had to pay lawyers to deal with a lawsuit contesting the election

Source: Re-elect Chris Faraldi, Store

In 1945, a judge's ruling in a lawsuit forced a change in the Democratic Party nominee for Lieutenant Governor. Sen. Harry Byrd did not give his "nod" to indicate a preference in the primary, the process by which Democratic nominees were chosen at the time, so the decision was made by voters. Charles Fenwick won 51,922 votes and Preston "Pat" Collins won 51,350 votes.

However, in two counties the vote totals appeared to be dishonest. Collins won 97% of the votes in Appomattox County, and Fenwick won 92% in Wise County. Collins sued to disqualify all of the Wise County votes, but Fenwick took no action to disqualify the equally-suspicious Appomattox County totals.

There was no three-judge Recount Court process in 1945; a judge in Richmond made the ruling. Investigation revealed that all but two of the 26 or 27 pollbooks recording Wise Cunty votes had disappeared. Those pollbooks may have been burned by corrupt local officials who had been paid to manufacture votes for Fenwick.

The judge determined that Wise County was "impregnated with political crooks and ballot thieves." He voided the Wise County results as requested by Collins. The judge's decision changed the statewide vote totals; Fenwick lost the nomination and Collins was declared the winner. He was re-elected as Lieutenant Governor four years later without any vote counting controversy.

In the rare cases when a nominee drops out of a race or dies before election day, the local or district party committee will typically choose a replacement candidate. A quick decision gives replacement candidates more time to campaign, and focuses campaign resources on the general election rather than on an internal-to-the-party contest.

However, replacements have been chosen in a firehouse primary that gave voters a second chance. In 1991, the Speaker of the House of Delegates, A.L. Philpott, died on September 28. The local Democratic committee in his Southside district chose to have a firehouse primary, though the deadline to choose a replacement that would be listed on the ballot was October 5.

Campaign signs were quickly printed and placed on roadsides across the district, though one candidate made sure to cover his signs on the funeral route with black plastic bags on the day A.L. Philpott was buried. Over 5,000 people voted in the firehouse primary, and the margin of victory was just 200 votes.25

The most significant decision made by a Recount Court involved the 94th District of the House of Delegates race in 2017. The three-judge panel chose to count a ballot that local election officials had disqualified. The decision of the judges ended up changing who won the race; the Democrat who had been initially certified was replaced by a Republican.

The decision to award the race to the Republican candidate determined that the Republican Party, rather than the Democratic Party, would control the House of Delegates with a 51-49 majority for the next two years.26

On April 7, 2024, in advance of another presidential election after four years of claims by President Trump that the 2020 election was a "steal," Republican Governor Youngkin issued Executive Order Number 35. It required the Virginia Department of Elections to remove people from the voting rolls every day, rather than weekly or monthly, if they had checked the box indicating that they were not a citizen during a process at the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). People who were removed from the voting rolls were mailed a form letting them attest to their citizenship, but had to return it within two weeks in order to be reinstated.

The Governor defended the removal of 6,000 names as part of his voter integrity initiative. He claimed the removals were based on information that was specific to the disqualification of an individual voter:27

News media quickly found individuals who were qualified to vote, but dropped from the voter rolls because they had simply failed to put a checkmark in the correct box on a DMV form. Any such voters who had failed to get restored to the rolls in time had the opportunity to re-register and vote on Election Day.

Cardinal News found a voter who had responded within 14 days, but been purged anyway. That voter suspected the mail delivery of his response had been too slow. He re-registered before the election in order to vote, saying proudly that he was a 100% Republican.

The publisher of Cardinal News commented28

Governor Youngkin made clear that he was confident in the overal legitimacy of the election process in Virginia for which he was responsible, a statement from the state's top Republican official that was inconsistent with claims being made by presidential candidate Donald Trump. He announced:29

candidate signs lined the road to an early voting location in Washington County (September 30, 2023)

The League of Women Voters, the Virginia Coalition of Immigrant Rights, and the US Department of Justice sued. They claimed that the purge of voters violated the National Voter Registration Act, which required a "quiet period" without systematic voter list maintenance within 90 days of a Federal election to prevent states from disenfranchising eligible voters. Under the law, as highlighted by Governor Youngkin in his defense, individualized information may be used to make removals.

On October 25, 11 days before the presidential election, a Federal judge in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia issued an injunction against removing registered voters. The judge ordered Virginia to restore 1,600 names back to the voting rolls. The state chose to appeal that decision to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Two days later, just nine days before the election, a thtree-judge panel in that Federal court unanimously rejected the appeal. The next day, Virginia appealed the case to the US Supreme Court and won.

In a 6-3 decision issued one week before the November 6 election, that court authorized Virginia to continue to remove voters who had not checked the correct box on the Departmewnt of Motor Vehicles form. Non-government organizations and the media tracked down people who had been removed, and in multiple jurisdictions found people who were qualified voters but had checked the wrong box. The Virginia Department of Elections revealed on Election Day that purges of the voter rolls had stopped on October 15.

After the District Court ruling, the Republican Attorney General Jason Miyares had articulated the core of the state's case:30

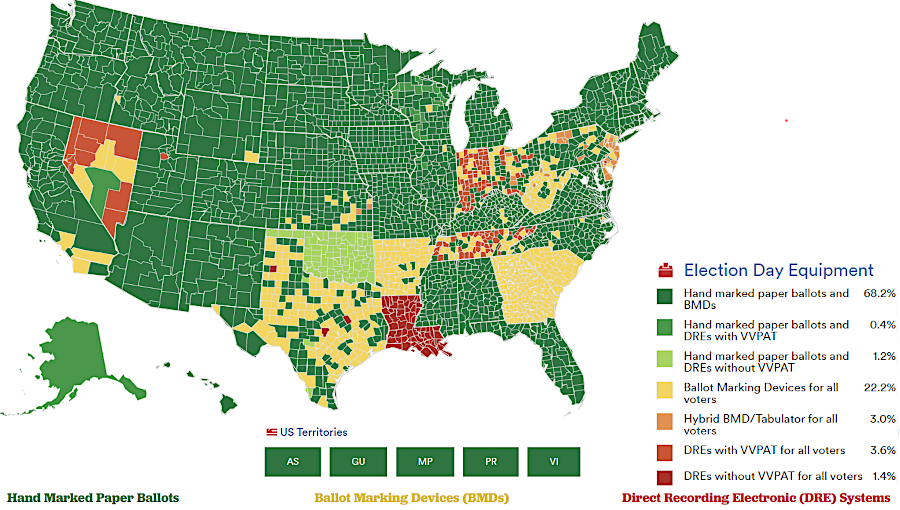

The efforts of Governor Youngkin to reassure people that the election process in Virginia was fair did not satisfy the two Republican members of the City of on the Waynesboro Board of Elections. They filed a lawsuit in October, 2024 claiming that the voting machines used in Virginia for scanning and counting the ballots were unverifiable. The lawsuit demanded that the state require all ballots be counted by hand. The Republican Attorney General planned to defend the state and defeat the lawsuit.

As election officials, they said the processes used to validate the machines were not adequate and they could not certify that machine-counted votes were accurate. They would also have known that before each election, a random sample of ballots are scanned and then hand counted to validate the accuracy of each machine. In contrast to the effort to create doubt about the election, a nonpartisan and non-government organization called Verified Voting had already determined that Virginia's use of hand marked paper ballots (which left a trail of paper votes that could be recounted and audited) provided the most reliable and verifiable voting process.

Virginia uses the most reliable and verifiable voting process, with hand marked paper ballots

Source: Verified Voting, The Verifier - Election Day Equipment - November 2024

Those two local election officials must have been aware of the potential cost and delay associated with getting people to count by hand over seven million ballots that would be cast in the 2024 presidential election. All the staff working for the registrar in Waynesboro were part-time employees. The lawsuit required them to spend extra time responding to e-mails and phone calls about voting procedures and election integrity.

A law professor at the University of Richmond described the justification for the lawsuit:31

President Trump's nationwide victory in 2024 muted much of the talk from his supporters about dishonest vote counting and stolen elections. There were several recounts in different local races after voting finished on November 5, but the results were not disputed. As described in the Richmond Times-Dispatch:32

The chair of the Republican Party said:33

computerization, especially Geographic Information System (GIS) technology, has provided new techniques for Get Out The Vote (GOTO) and voter suppression campaigns

Source: Virginia State Board of Elections, Evolution of Virginia Elections

seven minutes after voting ended in the 2024 presidential primary, the scanner tape was run at Bristown Run precinct and recorded 561 votes

Source: Prince William County Office of Elections, March 2024 Dual Presidential Primary Election Results