until after the Civil War, only white men had an opportunity to vote

Source: Humanities - Picturing America, George Caleb Bingham: The County Election, c.1852

until after the Civil War, only white men had an opportunity to vote

Source: Humanities - Picturing America, George Caleb Bingham: The County Election, c.1852

During the colonial period, only freemen (adult white men not working as an indentured servant) could vote. Initially, in order to vote a person had to own land. That led to fraud as people purchased or leased small slices of land in order to quality to vote in different jurisdictions. In 1736 the General Assembly clarified that a person had to own 100 acres of land, or 25 acres plus a house, and could only vote in one jurisdiction in which they owned land.

Since women were never allowed to vote in colonial Virginia, they were never "disfranchised" as a group because they were not "enfranchised" until the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution required Virginia to allow them to vote starting in 1920. Similarly, Native Americans were not disfranchised because they were "Indians not taxed" and not allowed to vote, even after ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870. Even after passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924 declared all the Native Americans who had been born within the United States to be citizens, voting barriers erected during the days of Jim Crow were applied to Native Americans.

Black men were not granted the right to vote until a new state constitution went into effect in 1870. That document theoretically gave black men (but not black women) the right to vote, but from the beginning that right was constrained by both official and unofficial actions by white men.

It is possible that one or more persons of color had managed to vote in the 1620's, but in the mid-1600's Virginia's colonial leaders made clear that blacks would be enslaved for their entire lifetime and slavery would be hereditary. They would not be granted the same freedoms as white indentured servants, who were allowed to vote after completing their terms of service (their "indenture") and acquiring property.

The prohibition against voting by women, slaves, mulattoes, Native Americans, indentured servants, and those under the age of 21 were formalized in different acts of the General Assembly passed in 1699, 1705, and 1723. Passage of those laws suggest that that there had been a problem recently when a member of the excluded class had tried to vote, triggering a response by the General Assembly.

The 1723 law, "An Act directing the trial of Slaves, committing capital crimes; and for the more effectual punishing conspiracies and insurrections of them; and for the better government of Negros, Mulattos, and Indians, bond or free," may have included specific language in response to concerns that a non-white man had tried to vote:1

The stimulus for passing those laws may have been someone trying to violate the customs of the day, causing one or more county sheriffs to ask for official authority to block a future attempt to vote.

The first group to have the right to vote and then be disfranchised were white males living in a household with an older male. In 1655, the right to vote for members of the House of Burgesses was limited to just the heads of households.

During the Interregnum after Charles I had been executed in England, the Puritans had sent an expedition to seize Virginia from royal supporter Governor William Berkeley. After they took control of Virginia in 1652, they held an election for a new House of Burgesses. Voters were required to swear a new oath in support of Parliament rather than the king. Some royalists may have felt disfranchised, but it appears voter turnout was still high.

The legislature elected after the Puritans took control did limit the suffrage for the first time. The General Assembly decided in 1655 that only one person per family could vote in future elections, and made clear that voters had to be at least 21 years old.

As a result of the 1655 law, sons who were living with their father lost the right to participate in elections for the House of Burgesses. Young men living in homes of their older brothers, and formerly-indentured servants still living in the home of their employer, also were disfranchised.

Since all males over sixteen years of age had to pay the poll tax, the class of young males 16-20 years old experienced taxation without direct representation. They could express their concerns to the head of the house, in hopes of shaping his vote and affecting an election indirectly.

The one-vote-per-household restriction on the electorate lasted only one year. In 1656, the burgesses concluded:2

between 1619-1920, white men (and later black men) controlled who would represent all Virginians in the General Assembly

Source: Internet Archive, A school history of the United States, from the discovery of America to the year 1878 (p.40)

The second group to be disfranchised were white males without enough property (land or a lease for land) to be taxed.

In 1660, William Berkeley was restored to his position as governor in Virginia and Charles II was restored as king in England. In 1670, Governor Berkeley restricted the right to vote to white males who owned enough property that they were required to pay local taxes.

The governor was concerned about the growing numbers of former indentured servants who had completed their term of service, but had not acquired land to start their own farm. The governor prioritized maintaining peace with Native Americans, with whom he was engaged in a profitable fur trade. He was not willing to go to war so colonists could establish new farms in the backcountry.

Driving those Native Americans far away would reduce raids on the outlying "quarters" staffed with indentured servants and enslaved people, and on the small farms created by the indentured servants after their terms of service were completed. However, the governor was not willing to pay the militia to complete that expensive task.

He was willing to approve construction of new forts, which also required new taxes but provided little or no military protection. The political advantage of building forts was that key members of the already-wealthy gentry got paid to build them. The gentry also were appointed to different colonial offices that required higher taxes as well. The elite who depended upon the governor supported him as he redistributed wealth collected from many taxpayers to just a few officeholders, but the poor farmers ultimately grew unruly. The new property requirement limited the ability of the unhappy farmers burdened with extra taxes to prevent the governor and General Assembly from "soaking the poor."

In England, the right to vote had long included a property requirement. For many locations, the minimum was 40 shillings. As inflation increased, more and more people qualified to vote. Different boroughs had separate requirements. In one, the judges allowed "potwallopers" to vote. A potwaller/potwalloper did not own or rent an entire house, but had enough control over one fireplace to boil the pot for themselves and their families.3

The property requirement was dropped briefly in 1676, when Governor Berkeley finally dissolved the "Long Assembly" and called an election for a new House of Burgesses. That was followed by Virginia's first civil war, Bacon's Rebellion.

After the rebellion was suppressed, royal instructions required reinstating the property requirement. The General Assembly passed such a mandate in 1684, and Virginians had to own a minimum amount of property in order to vote for the next 175 years.

A law passed in 1705 required that a man had to live in the county where he voted, but later laws simply defined a property rather than residence requirement. Relaxing the residence requirement allowed some wealthy property owners to vote in multiple jurisdictions, and to choose between them when running for the House of Burgesses.4

In 1736, the property minimums were defined as 100 acres of undeveloped land, 25 acres with a house and farmed land plantation, or a town house and lot. In 1762, the minimum ownership of undeveloped land was lowered to 50 acres and the minimum size of the town house was set at twelve feet by twelve feet (twelve feet square, or 144 square feet). Since normal town houses were at least twenty feet square, the 1762 law expanded the electorate.

The first state constitution adopted in 1776, after the colony of Virginia declared independence from Great Britain, did not alter voter qualifications. Voting was restricted to while males over 21 who owned land or a house. The 1723 law that said "no negroes, mullatto, or indian whatsoever shall hereafter have any vote at the election of burgesses, or at any election whatsoever" remained unchanged.

There was discussion of expanding the concept of "liberty" to include more than just white males. "Liberty" was popularized as the rationale for revolution, but the Fifth Virginia Convention revised George Mason's Declaration of Rights to include the alteration proposed by Edmund Pendleton that limited who would be affected. That modification (emphasis added) ensured that enslaved people who were presumed to be living "in a state of nature" would not be allowed to vote.5

The 1830 constitution relaxed the requirements and authorized more white males over 21 to vote. The new constitution added leaseholders who paid taxes on $20-25 of property, plus all tax-paying housekeepers who were heads of families. Those who owned less property were not disfranchised in 1830. They had never been allowed to vote, so their ability to vote had not been removed.

The 1851 state constitution finally dropped the property ownership barrier to voting. It stated:6

The third group to be excluded were Catholics.

The Church of England was the established church in Virginia. Parish boundaries were defined by the General Assembly, and new parishes were created in a parallel process with the creation of new counties. Anglican ministers were paid by local taxes collected by the county sheriff, and Anglican vestries were responsible for social welfare efforts such as finding homes for orphans. The Anglican form of worship was required. Governor William Berkeley in particular sought to purge the colony of Puritans, Quakers, and others who did not conform.

When colonists first arrived at Jamestown, Catholics were associated with Spain and France, which was beginning settlement in the St. Lawrence River valley and on islands near the Atlantic Ocean shoreline.

There were Catholics spies in the early colony and in England who managed to feed information about the early Virginia colony to the Spanish ambassador in London, Don Pedro de Zuniga. Catholics in Jamestown were viewed as military threat, and as potential saboteurs if a Spanish ship arrived to attack. George Kendall was deposed from his position on the Council and in 1608 became the first man executed in Virginia, after being accused of serving as a spy for Catholic Spain.

Creation of the Maryland colony in 1608 brought Catholics to the area and constrained Virginia's fur trade in the upper Chesapeake Bay. Economic and religious rivalries merged, and during the English Civil War Virginians provided assistance to rebels who seized control from the Calverts.

The disruptions in Maryland caused members of the Brent family to cross the Potomac River and settle in Virginia. Their wealth and social status made them welcome in Stafford County, even though they were Catholics.

Religious conflict in England triggered new restrictions on Catholics in Virginia. In 1672 King Charles II issued a Declaration of Indulgence, easing penalties imposed upon Catholics, Dissenters, and other nonconformists, but Parliament passed the Test Oath in 1673 to require all officials to commit to membership in the Anglican church. Charles' brother James, heir to the throne, had converted to Catholicism in 1668/69. He chose to resign his position as Lord High Admiral, and also married a Catholic woman.

King James II assumed the throne in 1685, the first openly-Catholic ruler since Queen Mary in 1553-1558. He ignored the Test Act and appointed Catholics to high positions in courts, universities, and the military. In 1687 James II reissued the Declaration of Indulgence.

In 1687, George Brent from Stafford County joined with three other partners in England and purchased a large parcel from Lord Culpeper. The potential for settlement had increased after the Iroquois agreed, in the 1684 Albany agreement (also known as Lord Howard's treaty), to limit their travel in the Piedmont and stay "at the foot of the mountains."

The four land speculators got James II to allow settlers at the 30,000-acre Brent Town settlement to practice their religion without restriction. The plan was to attract Huguenot refugees fleeing France, after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes which officially tolerated Protestants in 1685, but they later switched and sought to recruit Catholics. In 1688, while James II was placing Catholics in high positions in England and the Test Act was not enforced, Brent was elected to the General Assembly.

The moment of crisis occurred after Queen Mary gave birth to a male heir in 1688. That created the prospect of a new royal line of Catholic monarchs. In England, it triggered the Glorious Revolution in which James II was forced to flee to Europe and William and Mary became the new monarchs in London.

In Virginia, Rev. John Waugh was an Anglican minister and anti-Catholic agitator in Overwharton Parish, which included a church at Aquia. In 1689, he claimed that Catholics and Native Americans in Maryland planned to murder Anglicans north of the Rappahannock River. To protect his personal safety, George Brent was placed under house arrest until officials could restore calm. In Maryland, the agitation led to removal of the Catholics from government, a shift in the state capital from St. Mary's City to Annapolis, and official establishment of the Anglican Church in the once-Catholic colony.

George Brent did not return to the General Assembly, and he ended up being the only Catholic elected to office in colonial Virginia. In 1699, the General Assembly banned "recusant convicts" (those who refused to attend Anglican church services) from voting:7

Catholics did not regain the right to vote until 1776. The Fifth Virginia Convention adopted a Declaration of Rights stating "all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion," and Virginia's first constitution made no reference to how religious status affected suffrage.8

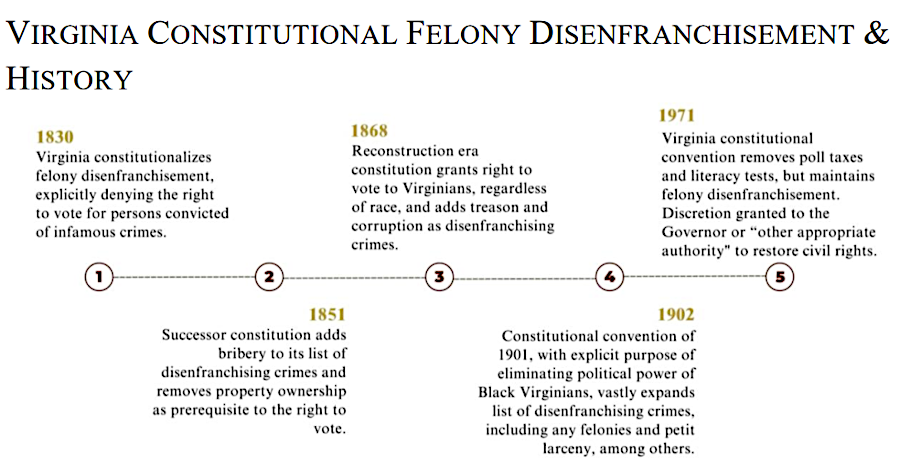

Criminals were the fourth group of Virginians to be disfranchised as a class. When the state adopted its second constitution in 1830, people convicted of an "infamous offence" lost the right to vote. The 1829-1830 constitutional convention retained the requirement for voters to be property owners, and also recognized that free black men were convicted of "infamous offences" at a percentage four time greater than white men. The ban of felons from voting after 1830 affected only whites, since even free black men at the time could not cast a vote.

The restriction on felons voting has been retained and expanded in all subsequent constitutions. In 1870, the General Assembly initiated a register (a paper database) documenting who was disqualified to vote, requiring that:9

members of the House of Burgesses who met in the Capitol Building in Williamsburg were elected by white, Protestant males who owned at least 50 acres or a townhouse

Source: Wikipedia, Old Capitol Building, Williamsburg

The power to disfranchise criminals was expanded in 1876 by an amendment to the state constitution that blocked from voting those convicted of petty theft ("petit larceny"). The 1876 law was designed to exclude blacks who, during Reconstruction, were actively engaged in the political process. Black men were voting and even being elected to office as Republicans.

The 15th Amendment to the US Constitution blocked the state from simply declaring that only white men could vote. The 14th Amendment included a key exemption, allowing a state to block voting by anyone guilty of "participation in rebellion, or other crime." After the 1876 amendment white sheriffs, working with racially-biased white judges and juries who were also conservative Democrats, ensured that black men would be convicted of petit larceny crimes, and thus disfranchised at a far higher rate than white men.

Legislators took another step to ensure that conviction of felonies and petty theft led to removal of voting rights. After the state constitution was amended in 1876 to disqualify voters convicted of petit larceny as well as felonies from voting, the General Assembly required that the courts send a list of all convicted people to voting registrars. That process enabled white Democrats to challenge black men when they appeared at a precinct, and block anyone convicted of even a minor crime from voting. What was theoretically a race-neutral law was designed to create inequity, not equality:10

When the state constitution was revised in 1971, the automatic loss of voting rights for those convicted of petit larceny was dropped. The provision was retained for people convicted of felonies.

President Richard Nixon declared a "War on Drugs" on June 17, 1971, and created the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1973. John Ehrlichman, Nixon's key domestic policy advisor, revealed years later that the "war" was designed to punish Nixon's political opponents, especially Vietnam War protestors and blacks:11

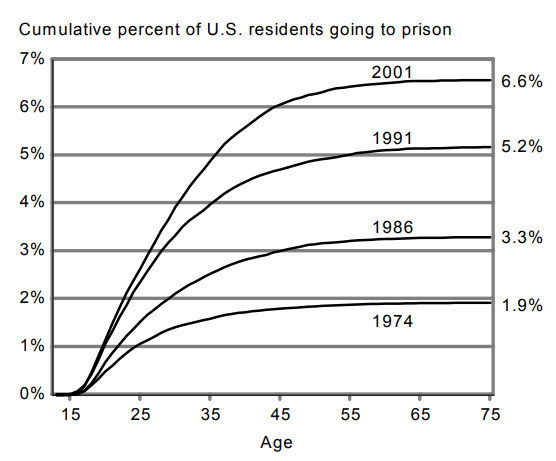

Nationwide, drug convictions swelled the 1.17 million felons disenfranchised in 1976 to over 5.85 million in 2010. The statistics for law enforcement demonstrated the racial bias during the War on Drugs. In 2010, almost 7.7% of blacks were disfranchised, compared to 1.8% of the rest of people in the United States.

In Virginia, 20% of adult blacks were disfranchised. Though only 19% of the state's population was black in 2010, but 58% of people in jails and prisons were black.12

imprisonment skyrocketed during the War on Drugs, and 20% of adult blacks were disfranchised in Virginia due to felony convictions

Source: US Department of Justice, Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974-2001 (Figure 3)

Unlike many other states, Virginia did not create a process for automatic restoration of voting rights after felons completed their sentences. Those seeking the rights to vote, serve on juries, and be elected to office had to petition the governor to take special action.

The 1870 state constitution gave the governor the power to grant pardons, including removal of political disabilities. That option was created at a time when former Confederates might require such action in order to vote. A Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals decision in 1883 drew a distinction between the governor's pardon authority and his authority to restore political rights. Since 1906, reports from the governor to the General Assembly have distinguished the number of pardons granted from the number of actions taken by the governor to restore political rights.13

starting in 1830, felons lost the right to vote

Source: Lucas Della Ventura The History of Felony Disenfranchisement & Restoration of Civil Rights in Virginia: 1830-2024 (Rights Restoration Summit, William and Mary Law School, 2024)

The distinctive legal steps for restoration of rights became a problem for the governor 110 years later.

In 2010, less than 3% of felons in Virginia had succeeded in getting their voting rights restored. Republican Governor Bob McDonnell, elected in 2011, started large-scale restoration of voting rights to felons in 2013. He processed the necessary paperwork for 8,000 people to regain their political rights after they had served their time in prison and completed parole successfully.

In 2016, Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe broke with precedent and issued a mass restoration for all convicted felons, if they had served their time and had completed all supervised release, parole or probation requirements. Republican leaders in the General Assembly filed a lawsuit challenging his authority to use one document to restore rights to 206,000 people. The conventional wisdom was that most of the convicted felons, many of whom were black males, were inclined to vote for Democratic candidates in the upcoming 2016 elections.

The lawsuit was quickly heard by the Virginia Supreme Court. The judges ruled that the governor had the authority to restore voting rights, but the paperwork had to be processed individually. The governor then completed the process in accord with the court decision, and restored voting rights to 168,000 convicted criminals in time for them to vote in the 2017 elections for the House of Delegates and State Senate. Governor McAuliffe restored rights to 5,000 more people before the end of his term, for a total of 173,166 people.

Source: Restoration of Rights | Terry McAuliffe for Virginia Governor 2021

The next Governor, Ralph Northam, continued the process. His predecessor had worked though most of the backlog, but Governor Northam restored voting rights for 11,000 felons in 2018.

In 2021, the governor announced that he was ending the requirement for felons to have completed probation before getting their voting rights restored. He processed the paperwork for 69,000 people who had been released from jail but were still on probation to regain their right to vote. However, he stopped short of restoring voting rights to the 33,000 people still incarcerated as felons.

The 2021 General Assembly passed legislation to eliminate the need for the governor to act. The legislators approved a constitutional amendment that would automatically restore voting rights. Until voters approved the amendment, however, the governor still had to act on individual cases. Governor Northam automatically restored voting rights as felons completed their sentences, but his successor Governor Youngkin ended that process. Starting in 2022, he began to require people to apply individually to get their rights restored.

Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi were the only states that automatically disfranchised felons. Democrats in the General Assembly prepared a constitutional amendment in 2025 for automatic restoration of voting rights. To become effective, it had to be passed again in 2026 and approved by the voters in the November 2026 election.

In 1982, voters had rejected by a 63-37% margin the proposed "Shall Section 1 of Article II of the Constitution of Virginia be amended to authorize restoration of civil rights to felons as may be provided by general law?" amendment; only eight of 136 counties/cities voted in favor. In 2025 public opinion polls indicated that 63% of the voters now supported eliminating the automatic prohibition.

A federal judge ruled in 2026 that the automatic disfranchisement of felons violated the Virginia Readmission Act and the Military Readmission Act. Those 1870 laws passed by the US Congress authorized Virginia to rejoin the Union after the Civil War and no longer be governed as Military District 1. The judge determined that the Federal laws trumped the state constitution. Because drug offenses were not a common law felony in 1870, it was not legal for the 1971 state constiution to disfranchise automatically those convicted of a drug-related felony.

The General Assembly gave Virginia voters an opportunity to change the state constitution in November, 2026. One of three constitutional amendments on the ballot was to automatically restore voting rights upon release from incarceration, ending the unique requirement for restoration of voting rights though action by the governor. No matter how Virginia voters acted on the proposed amendment or a later change, unless the Federal judge's decision was overturned the provision in the 1870 Readmission Act would remain in effect:14

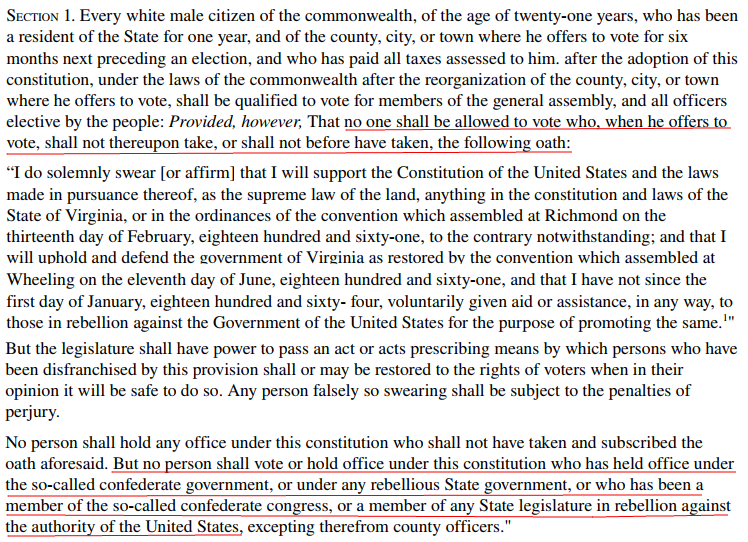

The fifth group of Virginians to experience mass disfranchisement were white male Confederates during the Civil War.

The Union Army occupied a portion of Virginia starting with the seizure of Alexandria on May 24, 1861, and the Federal government recognized the Restored Government of Virginia based in Wheeling as the official state government. When West Virginia was admitted as a state in 1863, the Restored Government of Virginia moved to Alexandria.

In 1864, the Restored Government of Virginia approved a new constitution for the state. It required voters to take an "iron clad" oath designed to disfranchise all who had supported the Confederacy after January 1, 1864. Anyone who had served in the Confederate government or state government was also banned. The 1864 constitution did not attempt to disfranchise local officials with the oath (emphasis added):15

the 1864 constitution attempted to block Confederates from voting

Source: For Virginians: Government Matters, Constitution of 1864

The 1867-68 convention, presided over by Federal Judge John C. Underwood, proposed a new state constitution with the requirement that voters take the "iron-clad oath" swearing they were always Union supporters.

The proposed constitution would allow black men to vote, but disfranchise those white men who had held public office prior to the Civil War and then supported the Confederacy. The moral argument was that those men had broken their oath to uphold the Constitution of the United States.

The practical effect, which may have been a prime motivator for those in the 1867-68 convention who wrote the new state constitution, was to block almost all of the conservative white leadership from participating in the political process. If the top white leaders were disfranchised, then the Republicans and the newly-enfranchised blacks would be able to control the governor's office, the General Assembly, and local offices.

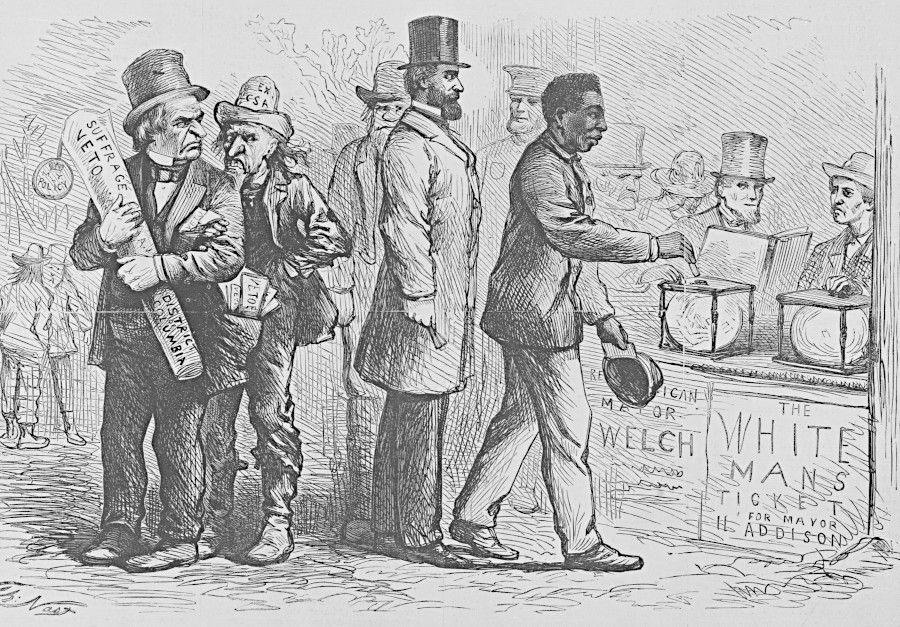

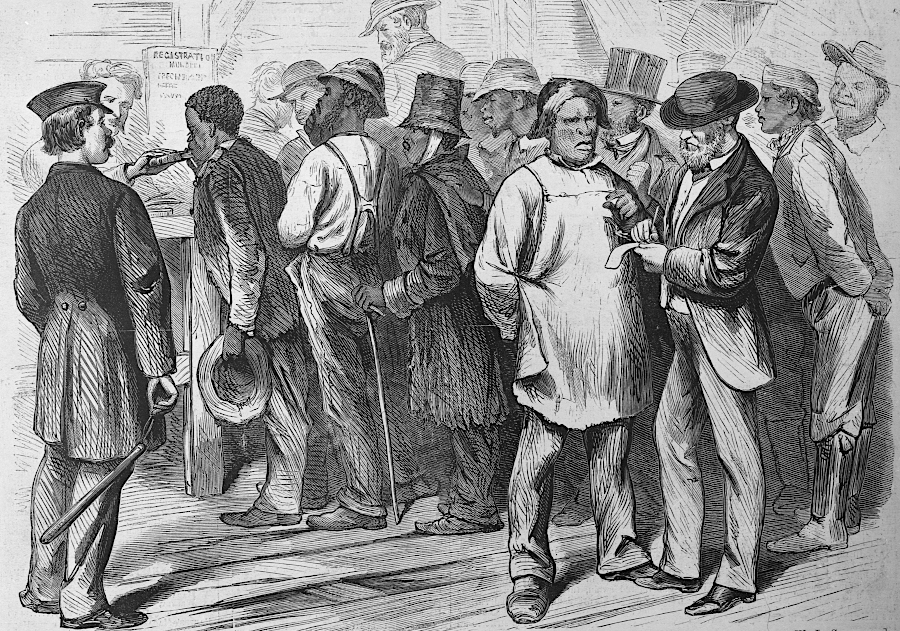

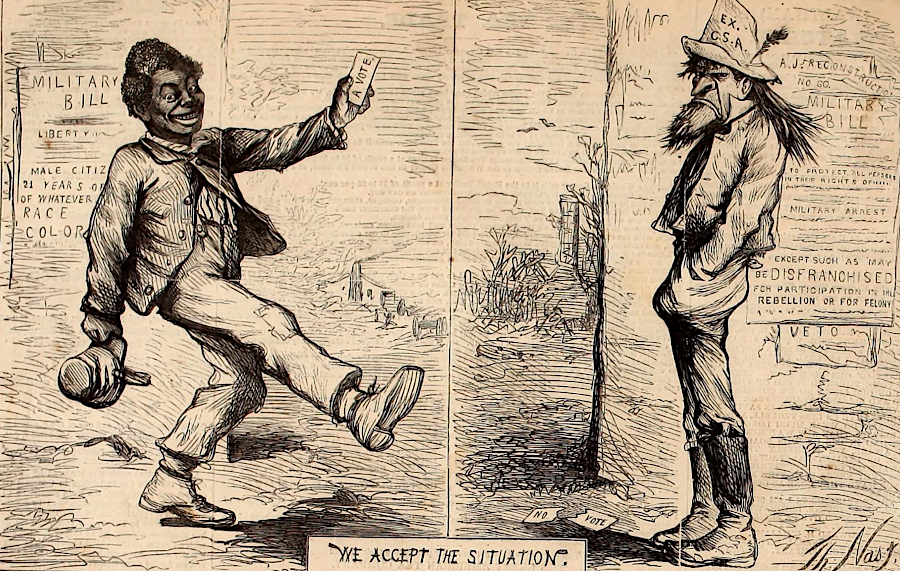

enfranchising recently-enslaved people, who had never been allowed to attend school, was controversial in all Southern states

Source: Library of Congress, The Georgetown elections - the Negro at the ballot-box (by Thomas Nast, 1867)

In 1869, a compromise was created to allow a separate vote on the suffrage restriction. Voters rejected the disfranchisement of Confederates, as proposed in the fourth clause of Article 3, Section 1:16

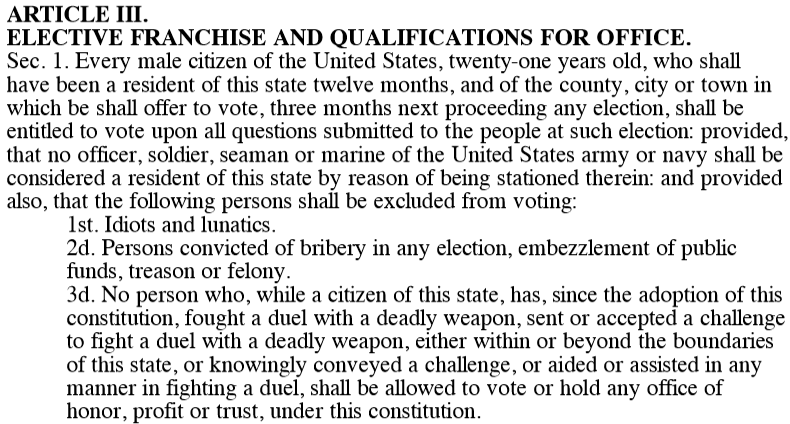

Article 3, Section 1 of the 1869 constitution included only three clauses, after voters rejected the proposed fourth clause to disfranchise former Confederates

Source: "Virginia Constitution, 1870," for Virginians: Government Matters, http://vagovernmentmatters.org/primary-sources/516 (last checked April 1, 2021)

The US Congress accepted the new state constitution, which allowed previous Confederate leaders to be eligible to serve in public office. Every male who had lived within Virginia was allowed to vote unless they were insane, felons, or had fought a duel. Former Confederates, like all other voters, had to register and take an oath:17

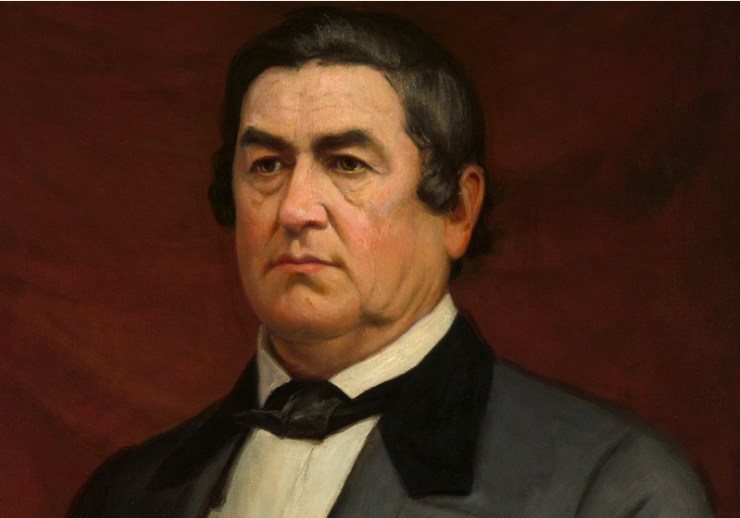

Robert M. T. Hunter resigned from the US Senate and became Confederate Secretary of State, so the Underwood Constitution of 1869 would have blocked him from voting if the disfranchisement clause had been approved

Source: U.S. House of Representatives, Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter

The sixth major group of people to be disfranchised in Virginia were black men. Because they lacked the right to vote and were not enfranchised until after the Civil War, black men were one of the last groups to be disfranchised.

On May 25, 1865, black men went to the polls in Norfolk to vote in the first election after the end of the Civil War, to send delegates and a state senator to Richmond.

At three wards, election officials refused to let the blacks vote. In the Second Ward, votes were recorded, though on a separate sheet which was not counted when determining results that day. Simply denying the right to vote in three wards extended the traditional barrier of disfranchisement by color, while the manipulation of the voting process by refusing to count the votes of black men in the Second Ward initiated a new mechanism of controlling the vote.

In March 1867, the US Congress declared Virginia to be Military District 1 and mandated the state adopt a new constitution that allowed black adult males to vote. The Federal government did ensure blacks could vote when Virginia elected a constitutional convention on October 22, 1867. Over 20 blacks were elected to serve in the convention.

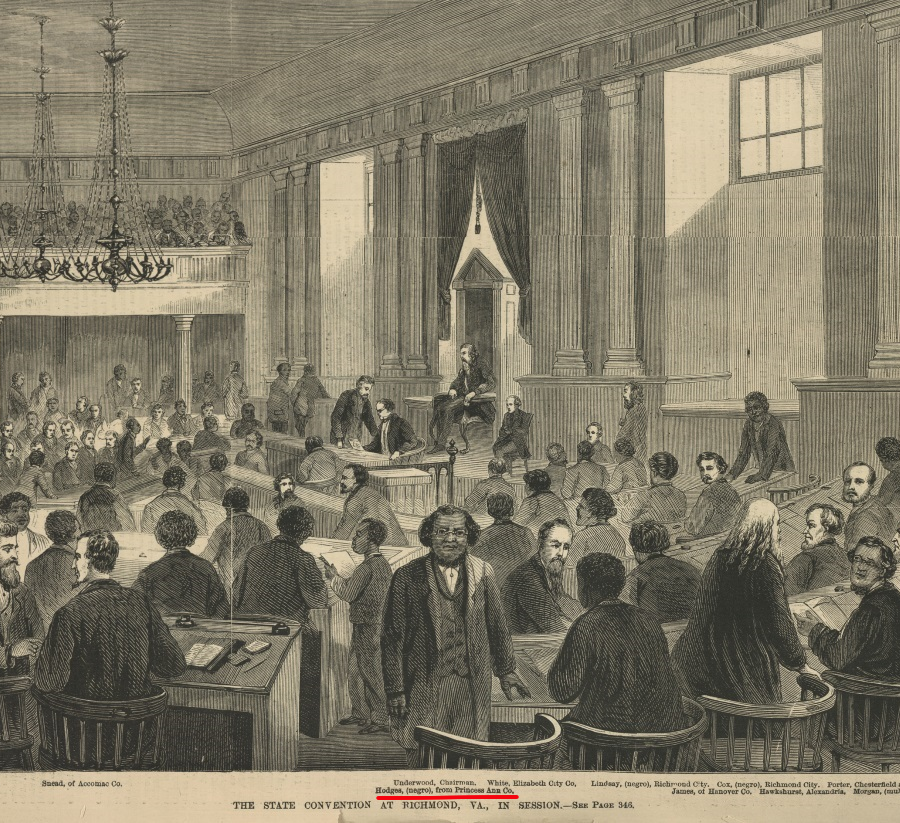

in 1867, the first black men were called to serve on a Virginia jury - which prepared to try Jefferson Davis in U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Virginia

Source: Virginia Humanities, Block the Vote

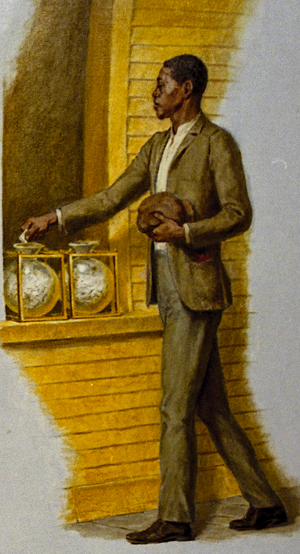

in 1870, black men registered to vote in Richmond while Federal troops were still located in the city

Source: Library of Congress, First municipal election in Richmond since the end of the war - registration of colored voters (Harper's Weekly, June 4, 1870)

One of those was Willis Augustus Hodges, elected from Princess Anne County. All of his 807 votes came from African American men voting for the first time. The candidate to serve in the constitutional convention with the second-highest number of votes was a white man. One of his 609 votes came from an African American man, and the 608 votes came from white men.

Known as "Old Specs Hodges" because he wore glasses, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper highlighted his presence in a February 15, 1868 illustration of the convention. In the 1869 election for the House of Delegates, his brother Charles E. Hodges was elected from Norfolk County/Portsmouth, and his nephew John Quincy Hodges was elected from Princess Anne County.18

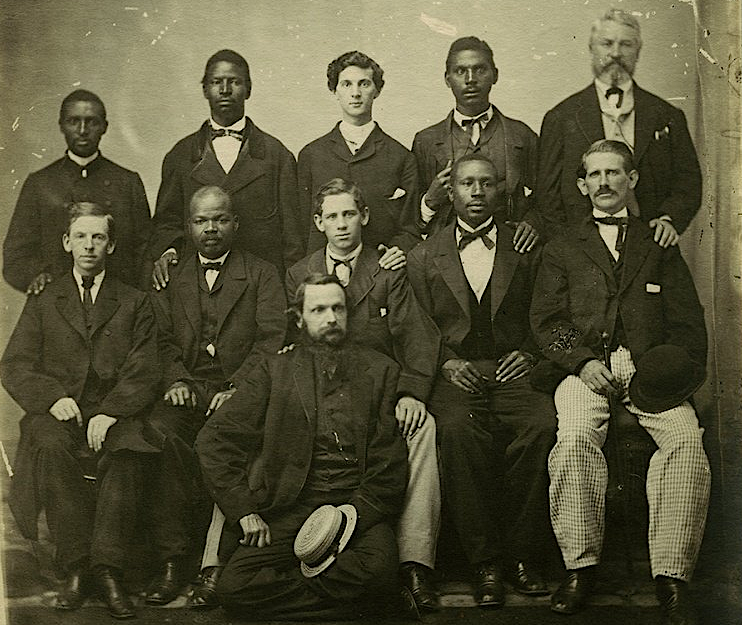

Willis Augustus Hodges, wearing glasses at the 1868 convention chaired by Judge John C. Underwood

Source: Library of Congress, First municipal election in Richmond since the end of the war - registration of colored voters (Harper's Weekly, June 4, 1870)

Disfranchisement of black men became possible only after the Fifteenth Amendment, was added to the US Constitution in 1870. In theory, after passage of the Fifteenth Amendment black men had the right to vote and be elected to office. Thee were 92 black men who served in the General Assembly between 1869 and 1890, and two-thirds of them had once been enslaved. Nineteen black members of the House of Delegates served at least two terms, and Ross Hamilton from Mecklenburg County was elected to seven terms.

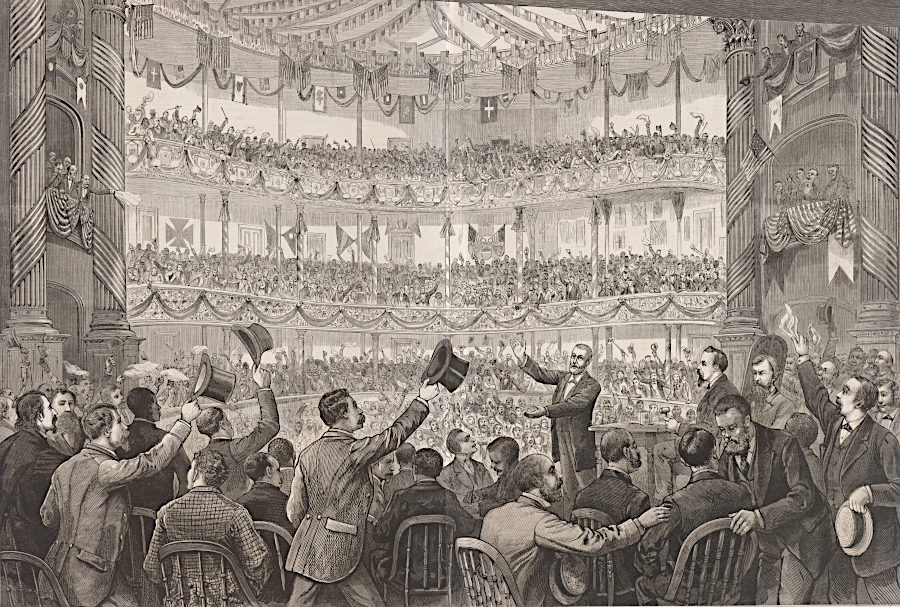

both black and white men served as delegates at the Readjuster Party's state convention in 1881

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia - The Readjuster State Convention at Richmond (by Walter Goater, 1881)

After the Readjuster Party was defeated in 1883, Virginia's Democrats ensured that few blacks participated in the political process. White Democrats in Virginia successfully kept many black men from voting through multiple techniques until Federal intervention in 1965.

After Virginia was readmitted to the Union in 1870, the General Assembly passed laws to evade compliance with the 15th Amendment. After Federal troops left Virginia in 1877, the law enforcement system was designed to discriminate against blacks in a series of laws named after a black character in minstrel shows, Jim Crow. White leaders in the southern states feared political equality might lead to economic and social equality between the races.

The scope of the 15th Amendment and legislation passed by the US Congress, including the Enforcement Act of 1870 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, were constrained by US Supreme Court decisions. In the 1876 United States v. Reese decision, states were empowered to define barriers to voting that appeared to be race-neutral, but when applied would discriminate against blacks:19

The US Supreme Court decision made possible the vision of former Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens to exclude the Federal government from protecting civil rights in southern states, and to allow businesses and governments to discriminate. Stephens had argued against passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, saying:20

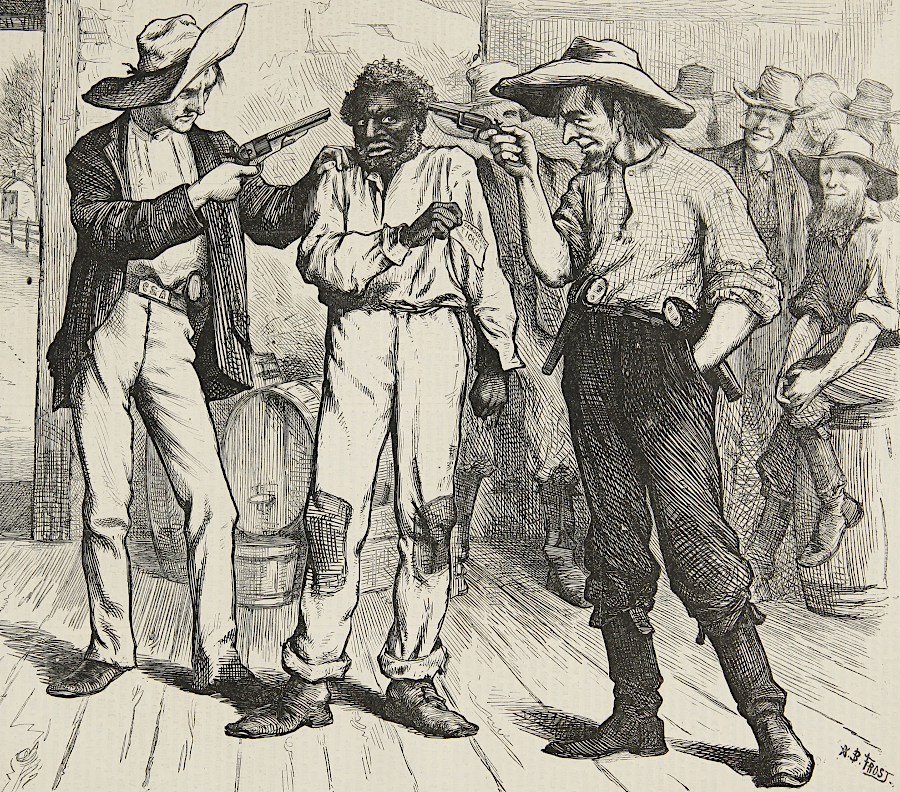

laws, voting procedures, and intimidation reduced the opportunity for black men to vote despite the 15th Amendment

Source: Harper's Weekly, Of Course He Wants to Vote the Democratic Ticket (by A. B. Frost, 1876)

Voters in Virginia passed two constitutional amendments in 1876 to shrink the number of eligible voters. The amendment to disfranchise men convicted of petit larceny led to large-scale convictions of blacks for small crimes. Because judges were all white, the amendment created a powerful tool for racial discrimination while meeting the Supreme Court's criteria for being race-neutral.

A second constitutional amendment also approved by the voters in 1876 created a poll tax, with similar intent to constrain primarily blacks from voting. Poll taxes had been imposed starting in 1623, when extra funding was required to recover from the 1622 uprising led by Opechancanough as head of the Native American paramount chiefdom. As Anglican vestries were created, they also depended upon a per capita tax to fund their operations.

The poll tax requirement ended in 1787, but was reimposed briefly in 1792. In 1813 the poll tax was reimposed, but only on "free negroes and mulattoes," and it ended in 1816. The poll tax was restarted in 1850, and applied initially to just free negroes with funding to be used for transporting free negroes to Liberia. A poll tax was imposed on white males starting in 1852. Until 1876 the poll tax was unrelated to someone's ability to vote.

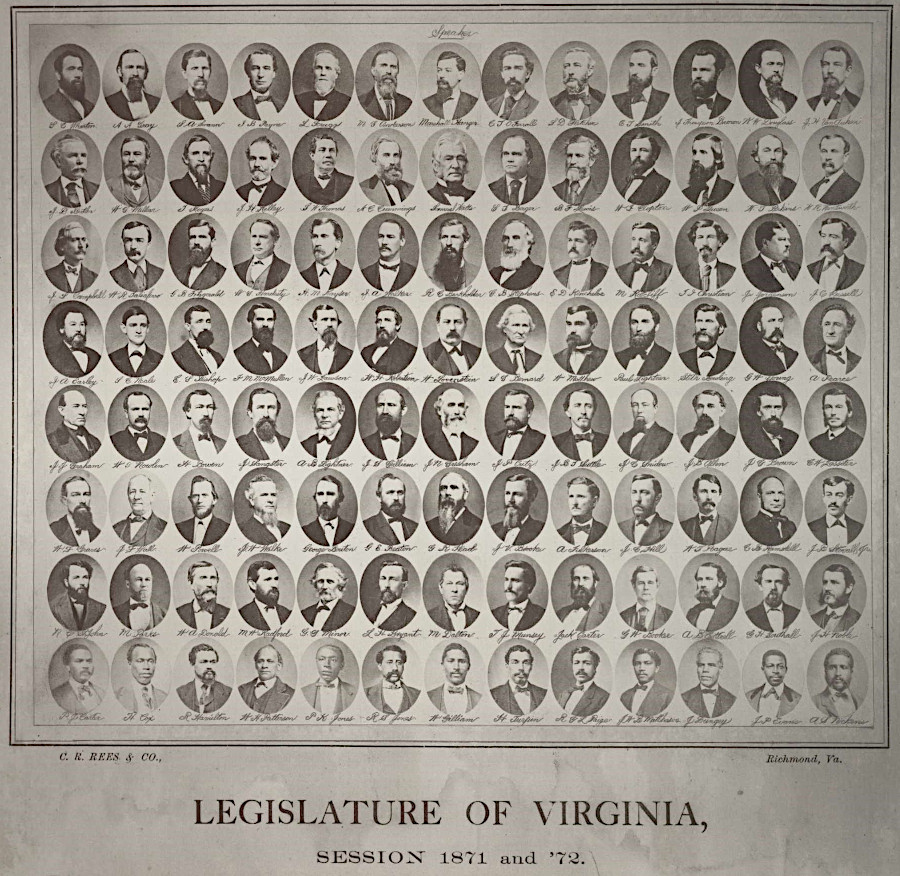

pictures of the members of the General Assembly in 1871-72 were segregated, with all black members on the bottom

Source: Library of Virginia, Legislature of Virginia, Session 1871 and '72

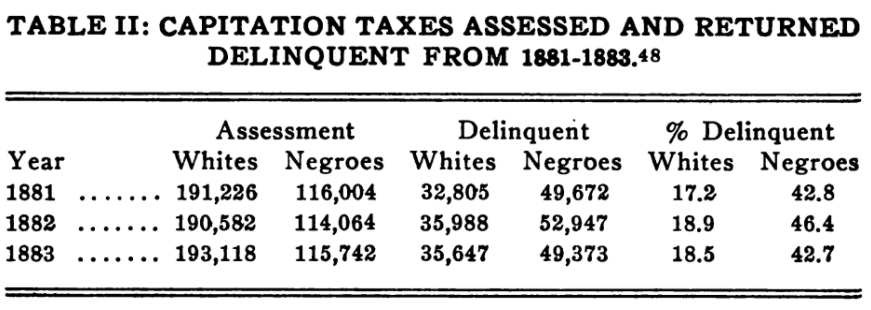

For the first time, the 1876 law made payment of the poll tax a prerequisite for voting. In theory, those desiring to vote would be incentivized to pay the tax, increasing compliance and revenue. Practically, those freed from slavery in 1865 were obviously less capable of paying the tax. The poll tax succeeded in reducing the total number of voters by 10%. Since blacks had less wealth than whites, the poll tax appeared to be race-neutral but in fact discriminated by race.

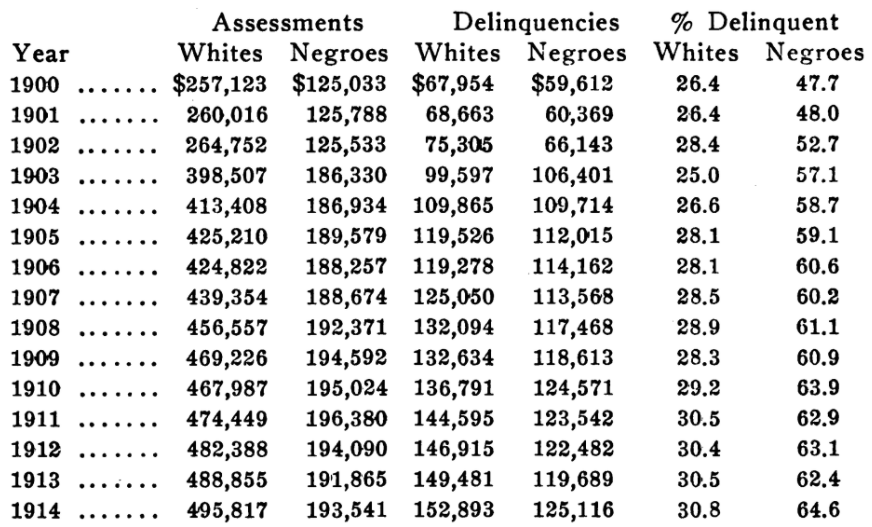

the requirement to pay the poll tax before voting had a racially-biased impact

Source: HathiTrust, The Taxation of Negroes in Virginia (by Tipton R. Snavely, p.21)

In 1882, the Readjusters controlled the General Assembly. They proposed a new constitutional amendment to allow voting without paying the poll tax.21

The Democrats gained control of both the House of Delegates and the State Senate from the Readjuster coalition, and then chose a new mechanism to control who would be able to vote. The General Assembly passed the Anderson-McCormick Act. in 1884. That law allowed the Democrats in the legislature to:22

1)

white former Confederates resented the ability of formerly enslaved black men to vote

Source: Harper's Weekly (April 13, 1867)

The result was blatant fraud in elections. At the time, voters provided their own ballots on which they wrote the name of the candidate which they supported. Voters committing fraud would secretly insert multiple copies into the ballot box.

At the end of election day, if an Electoral Board discovered more ballots than the number of voters who had participated in that day's election, the judges were required to randomly select and discard enough ballots to lower the total. The duplicate ballots stuffed into ballot boxes for Democratic candidates used paper with a distinctive feel. The judges could reach into the ballot box and "randomly" select for other ballots, then discard paper ballots which might include names of Republican and Readjuster candidates while ensuring ballots for Democratic candidates remained in the box.

The dishonest voting process became too obvious, so in 1894 the General Assembly passed the Walton Act. That law required electoral officials to provide a standardized ballot to voters. Voters were required to scratch a line through the names of candidates they did not support, while leaving the names of their preferred candidates unmarked.

The Walton Act eliminated the selective removal of ballots as a fraud technique and required that electoral boards include members of both political parties, but also provided new mechanisms to control the vote. When counting the ballots, electoral judges could choose to discard those on which the lines were not scratched through candidate names exactly as required by the Walton Act if the Republican candidate had been chosen, while accepting less-than perfect ballots cast for Democrats.

Electoral boards were required to appoint a special constable who would assist voters, especially those who were illiterate, to determine which lines to scratch through and which candidate names to leave unmarked. No one observed if the constable was honest in his guidance to voters as he performed his duties under the Walton Act:23

Electoral Boards controlled by Democrats ensured the constable was a Democrat. The appointment of constables was eliminated in a revision of the law in 1896, and electoral judges were given the responsibility to assist voters. They also retained the ability to manipulate the recorded "poll list" identifying who voted, so fraudulent ballots never cast by a voter could be included in the final total.

Illiterate voters who were unwilling to admit their ignorance and request assistance were not inclined to vote. Republicans found a way to overcome that reluctance. They arranged for someone to vote early in the day, then report which line had the Republican candidate's name so illiterate voters could be trained on how to vote "correctly" and without requesting aid. Democratic election officials countered that technique by having different versions of the ballots printed, so the Republican candidates would be listed on different lines.24

Virginia's white leaders took advantage of multiple opportunities to legally limit the number of black and white Republican voters. The discrimination occurred as Black Code or "Jim Crow" laws were established across the southern states; discrimination extended far beyond voting practices.

The US Supreme Court authorized "separate but equal" treatment of the races in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. That court also approved Mississippi's techniques to suppress the black vote in the 1898 Williams v. Mississippi decision. The court continued to rule that states could disfranchise black voters through racially-biased administration of laws that appeared to be race-neutral. Starting in 1904, Southern legislators in the US Congress even sought to create a case allowing the courts to rule that the 14th Amendment and 15th Amendment were not legally adopted.25

In 1902, a convention adopted a new Virginia constitution, written to exclude black men from the political process even more effectively. Legal discrimination would reduce the need for fraud, which became a problem when elections to the US House of Representatives were protested. Between 1874-1900, six elections in Virginia had been overturned by a Republican-controlled US House of Representatives because the election process had been so clearly tainted. New techniques, legal in the eyes of the US Supreme Court, could reduce the potential that Democrats would be denied a seat due to obvious cheating at the polls.26

The 1902 Virginia constitution was modelled on the 1890 Mississippi state constitution. Mississippi implemented a literacy requirement designed to minimize the number of black voters, successfully reducing the 76,742 black voters in 1890 to just 8,615 in 1892. At the Virginia constitutional convention, Carter Glass made crystal clear that the state would take advantage of the willingness of the US Supreme Court to allow discrimination, so long as the words were race-neutral. Virginia would use its new constitution to strip black men of the opportunity to participate in the political process:27

after passage of the 15th Amendment, Virginia officials managed to disfranchise black men by multiple techniques

Source: Architect of the Capitol, Lincoln's Second Inaugural, 1865

The 1902 constitution was successful in treating white and black voters unequally. The number of black voters fell from about 147,000 to fewer than 10,000, and Democrats gained control of a higher percentage of the vote:28

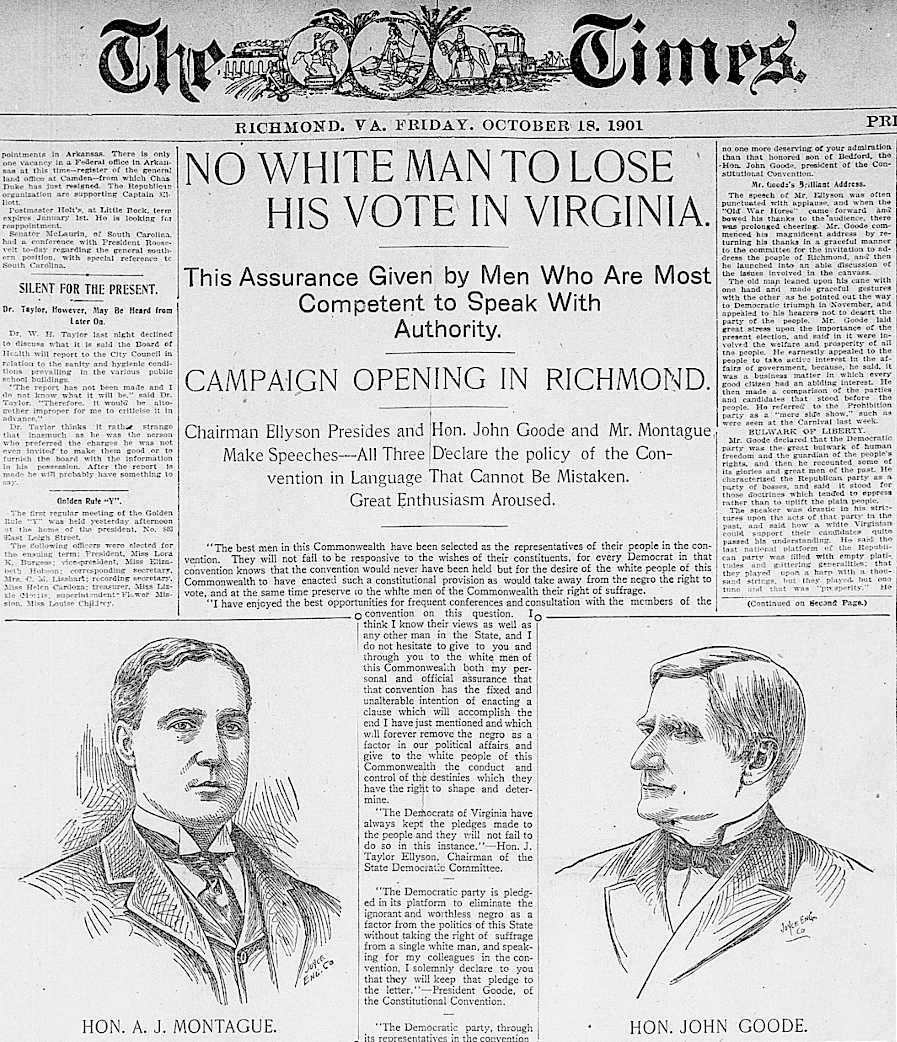

the 1902 Constitution was designed to limit the electorate by excluding people of color

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Times (18 October18, 1901)

One tool of the new constitution was to reinstate the requirement that voters must be taxpayers in order to be voters. The poll tax was already in effect before the 1902 constitution was adopted, but payment was not required before a man at least 21 years of age was allowed to vote. The new constitution required voters to pay a poll tax after 1904. It became the primary tool for ensuring a majority of the electorate supported white supremacy.

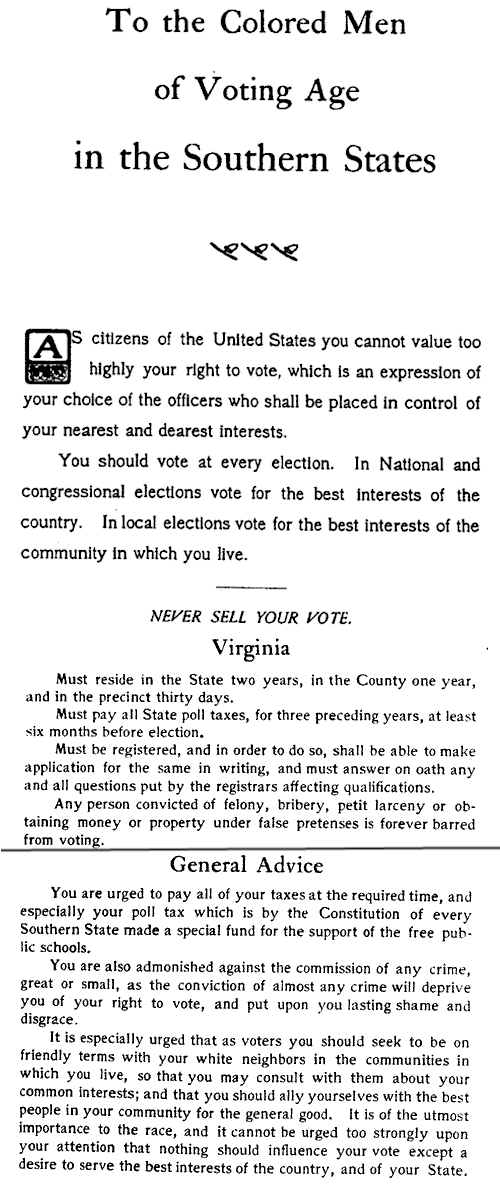

black men fought back against disfranchisement and sought to retain their voting rights

Source: Library of Congress, To the colored men of voting age in the southern states.

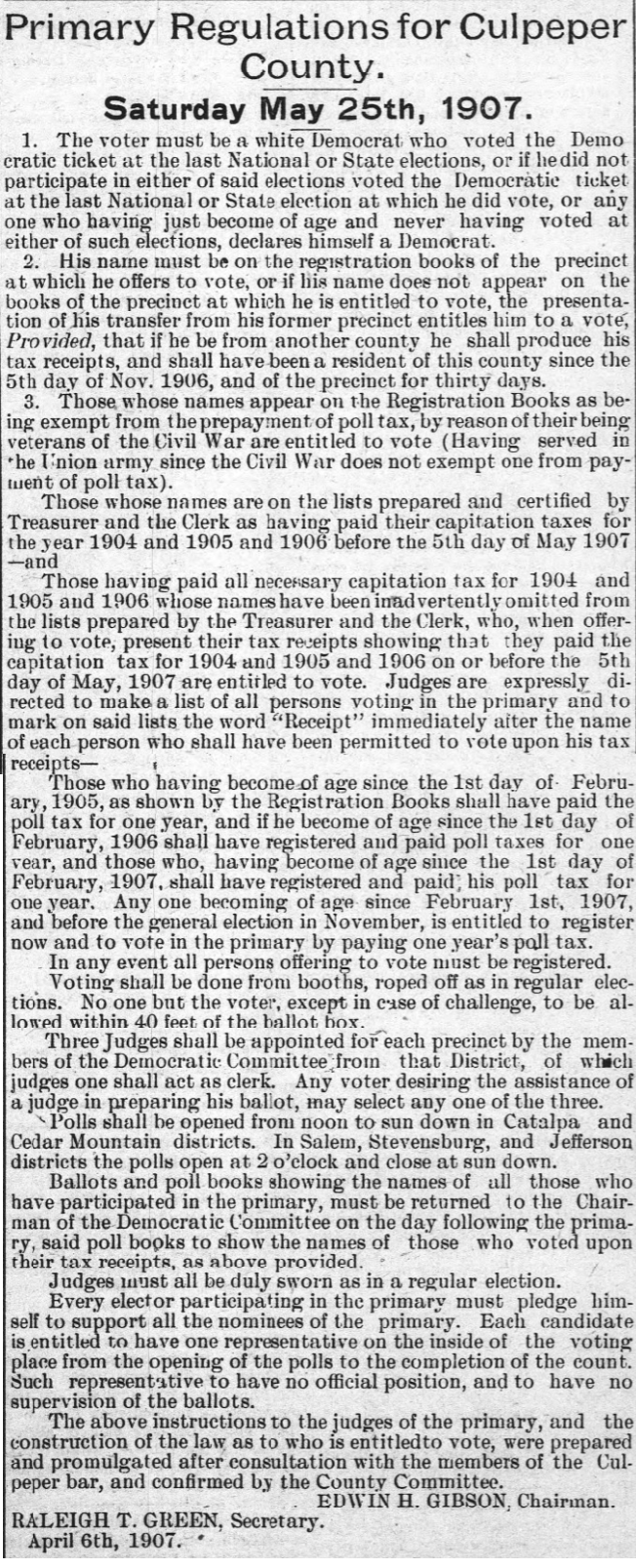

A "grandfather clause" in the 1902 constitution allowed all men to vote if they had served in the Civil War, as either a Union or Confederate soldier. This special provision "grandfathered in" older white voters without requiring them to pay the poll tax. Former Union soldiers who could take advantage of the grandfather clause, almost all black men, were far fewer than the whites who were allowed to vote without paying the poll tax.

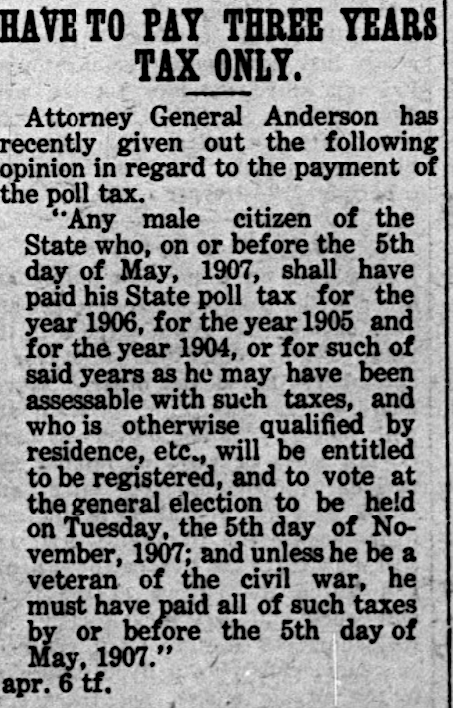

veterans of the Civil War were not required to pay the poll tax in order to vote after 1902

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Culpeper Exponent (May 10, 1907)

the 1902 Constitution "grandfathered" those who fought in the Civil War, or whose fathers fought, to vote without paying the poll tax

Source: Library of Virginia UnCommonwealth blog, We Demand Complete Realization: The Slow Legal Fight For Enfranchisement (September 11, 2020)

After the US Supreme Court ruled in 1915 that such clauses violated the 15th Amendment, the Virginia Attorney General commented that the grandfather clause was not needed to discriminate successfully,. He wrote in an Alexandria paper:29

the poll tax required after 1904 disfranchised far more blacks than whites, with even greater impact than between 1876-1883

Source: HathiTrust, The Taxation of Negroes in Virginia (by Tipton R. Snavely, p.35)

The Constitution of 1902 required all voters to register in advance. By that time, the white Democrats in the General Assembly had appointed all the judges in the circuit courts, and were confident that their perspective was "safe" on regarding race. The convention chose to professionalize administration of the voting process, creating the appearance of fairness in contrast to procedures used under the Walton Act.

Section 31 in the 1902 constitution assigned the authority to appoint members of local Electoral Boards to Circuit Court judges, rather than to the politicians in the legislature. The constitution also required that Electoral Boards appoint a roughly equal number of election judges from both the Republican and Democratic primaries. (After a 1928 amendment to the state constitution, one of the three members of the Electoral Board had to represent the political party which had won the second-highest votes in the most recent general election.)

Adoption of the 1902 state constitution gave the Democratic majority in Virginia the ability to use legal constraints in the registration process, rather than illegal fraud at the polls, to minimize the ability of black men to affect election outcomes.

In addition to the special clause for initially registering Civil War veterans, all males 21 and over who had paid property taxes of at least $1 were also allowed to register. Also eligible were males over 21 who were:30

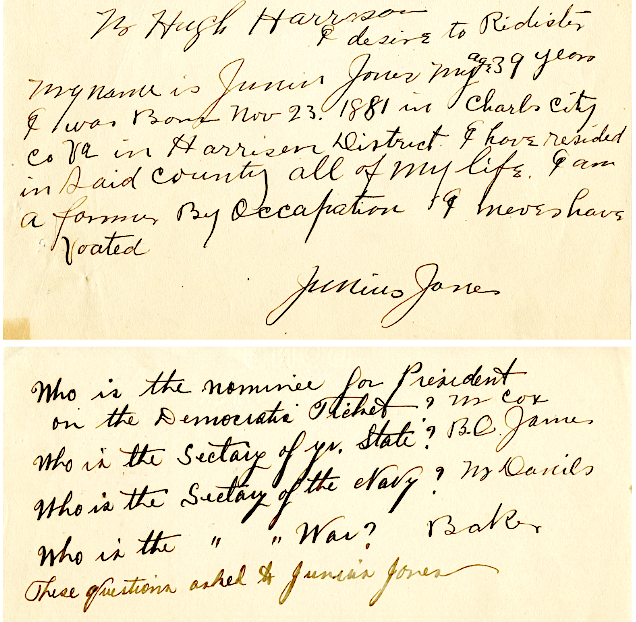

That provision allowed election officers to register illiterate white males, while refusing to acknowledge that black males qualified according to the "understanding clause." Starting in 1904, a literacy test was used to block people from voting. Starting in 1904, those seeking to register had to have paid poll taxes for the preceding three years (unless they were just turning 21), be able to answer "any and all questions affecting his qualifications as an elector.," and:31

understanding clause questions and answers for Junius Jones, a "colored voter" in Charles City County (1904)

Source: UnCommonwealth blog, Library of Virginia, Records Room Road Trip - Winter Circuit

The Democratic Party managed to block blacks from voting in party primaries, which were used after 1912 to nominate its candidates. By that time, Virginia was part of the Solid South where Democrats won almost every election in November. Nomination by the Democratic Party was tantamount to election, so candidates with conflicting priorities or personal agendas competed in the primary with confidence that the Democratic nominee would be elected in November.

Republicans in southern states recognized that they were doomed to defeat if they continued to support black voting rights. Disfranchisement based on racial lines was effective in preventing Republicans from winning elections with black votes. At the same time, even token Republican support of black voting rights pushed white voters towards the Democratic Party, as "Jim Crow" segregation expanded. After passage of the 1902 state constitution, the Republicans in Virginia decided to discriminate against blacks like the Democrats and recast themselves as a "lily white" party.

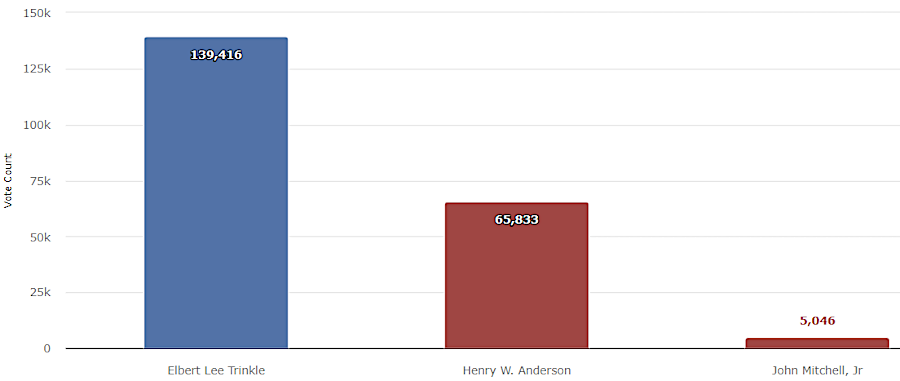

In 1908, all members in the Virginia delegation to the Republican National Convention were white. That convention refused to seat an alternative delegation from Virginia which included African-American men. In 1921, the Virginia Republican Convention in Norfolk openly banned any blacks from participating. In response, a convention of black Republicans met in Richmond. The 600 members nominated a "lily black" ticket, with just blacks selected to run for governor and other statewide offices.

John Mitchell, who published the Richmond Planet, was the first black man to be nominated by a major political party to run for governor. As the candidate on the Republican lily black ticket, Mitchell received 5,036 votes. The candidate on the Republican "lily white" ticket, Henry Anderson, received 65,833 votes. The Democratic candidate, Lee Trinkle, won with 139,416 votes.

running on the "lily black" ticket in the 1921 gubernatorial race, John Mitchell won just 7% of the Republican votes

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 1921 Governor General Election

The lily black protest drew attention, but did not change the policy of the white Republican leaders in Virginia. In 1922, the Republican Convention met in Luray to nominate candidates for US House of Representatives. The convention retained the lily white policy and excluded black delegates that had been elected by local party units.32

The Eastern District Court of the United States ruled in 1929 that a state-funded Democratic primary could not be restricted to just whites. A Federal appeals court upheld the decision in 1930.

Democrats could have claimed to be a private association and excluded blacks from a party-run primary or convention, but the party would have had to pay the costs for that nomination process. There was a slight increase in black participation in primaries in Virginia's larger cities, but the effectiveness of other discriminatory tools was adequate to protect the control of the Byrd Organization over the selection of candidates. When the US Supreme Court later invalidated white primaries in other southern states in the 1944 Smith v. Allwright decision, the Richmond Times-Dispatch calmly observed that blacks had been voting in Virginia and "the skies haven't fallen."33

In 1958, the General Assembly tried to block blacks from registering to vote by creating the "blank sheet" registration form. Activists such as Evelyn Thomas Butts responded to overcome the technique until is was ended in 1962:34

Democratic Party leaders and later the Byrd Organization mastered control of the electorate from the 1920's into the 1960's. Voter suppression was so effective that only 10-12% of the eligible voters actually participated in elections. Candidates endorsed by the "organization" led by Harry F. Byrd were assured victory with the support of no more than 7% of the potential voters.

The key to election was campaigning for support of Byrd allies who occupied local offices, the "courthouse clique," rather than campaigning for support from voters. In 1947 E. O. Key described the anti-competitive election process in Virginia as a "museum of democracy" rather than a vibrant process to determine priorities of the citizens.

After World War II, the Byrd Organization was threated from inside the Democratic Party by "Young Turks" who desired more funding for public education and services in urbanizing areas. The Republican Party gained supporters in reaction to Senator Harry Byrd's leadership of the massive resistance approach to Federal mandates for desegregation, culminating in the election of a Republican as Governor in 1969.

Federal court rulings, the 24th Amendment to the US Constitution eliminating poll taxes for Federal elections, and civil rights laws passed by the US Congress expanded the electorate in the 1960's. The poll tax was eliminated in state elections by the US Supreme Court's March 24, 1966 ruling in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections. The judges determined:35

Dr. William Ferguson Reid was the first person of color elected to the General Assembly in the 20th Century. He won a seat in the House of Delegates in 1967. Douglas Wilder became the first black man to serve in the State Senate after Reconstruction by winning a special election in 1969. Wilder became Lieutenant Governor in 1985 and Governor in 1989.

The first black woman elected to the House of Delegates was Yvonne B. Miller, elected in 1983. She became the first black woman to serve in the State Senate when she won election to that body in 1987.

The pace of increasing diversity in the state legislature was slow, but by the start of the 2024 General Session the change was clear. The Lieutenant Governor, the Speaker and the Majority Leader in the House of Delegates, and the powerful chairs of the "money committees" in each house were black.

Seven of the 40 members of the State Senate and 24 of the 100 members of the House of Delegates were black. That exceeded the previous peak of black legislators in 1869. Overall, there were 41 nonwhites elected to serve in the 2024 General Assembly.36

At the start of the 2024 General Assembly, Lt. Gov. Winsome Earle-Sears, House Majority Leader Don Scott and Senate president pro tempore Louis Lucas sat behind Governor Youngkin

Source: Virginia House of Delegates Video Streaming, Regular Session (January 10, 2024)

broadening the electorate after World War II led to greater diversity in the 2024 General Assembly

Source: Black Virginia News, How a Bold Black Firm Redefined Virginia's Political Future, Richmond Casino Vote Map Breakdown, Threat to Democracy: Trump Dominates Latest NH Poll

The processes used for disfranchising blacks also limited the potential for Native Americans to vote in Virginia.

Native Americans were not allowed to vote when Virginia was a colony, or after 1776. Federal laws regarding Native Americans were not relevant in Virginia, since there were no Federal treaties with Virginia tribes. Whites managed to buy the land in all but two areas once reserved for different tribes. The Pamunkey and Mattaponi managed to retain control of land, but lacked civil rights. White trustees were appointed to represent them in courts.

"Indians not taxed" were legally excluded from voting in states other than Virginia. The US Supreme Court, in an 1884 case, ruled that members of Federally-recognized tribes were not citizens as defined by the 14th Amendment.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 explicitly gave Native Americans the right to vote, but that same year the Virginia General Assembly passed the Racial Integrity Act. Discrimination against Native Americans in Virginia was based on a perception that they were so intermixed with blacks that the "Indian" identify had disappeared. Rather than acknowledge that the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 would be relevant in Virginia, the registrar of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics sought to classify all Virginians as either "white" or "colored." Walter Plecker claimed that anyone with one drop of African blood was black.

The disfranchisement on poor whites, blacks, and Native Americans reflected the ancient philosophy that an educated, wealthy alite should have more political power than the average citizen. In Rome, Cato the Younger was one of the "optimates," wealthy landowners who opposed the "populares" proposal to expand the number of citizens allowed to vote. Cato was celebrated by Southern leaders after the American Civil War in 1861-65 due to his Stoic acceptance of defeat without sacrificing his high values. Cato committed suicide rather than accept a pardon from Julius Ceasar; he was unwilling to be ruled by a victor who he thought had such a lower standard of morality.

William F. Buckley, conservative publisher of the National Review, supported the argument that white Americans were "the advanced race." In a 1965 debate at Cambridge University with James Baldwin, Buckley claimed that white privilege was appropriate because most black Americans were culturally deficient and not qualified to make public policy decisions. In his opinion, full civil rights did not extend to those who had not yet become as civilized as Buckley's peers.

When challenged by an audience member at Cambridge to allow blacks in Mississippi to register and vote in elections, Buckley revealed the elitist perspective when responding:37

after the American Civil War, Southern leaders celebrated Cato the Younger's choice of suicide in 46BCE rather than acceptance of being conquered by Julius Ceasar

Source: Departement de l'Isere, Mort de Caton d'Utique

The seventh and last major group to lose the right to vote were black women. The tools used to limit the ability of black men to vote were applied to black women, as soon as they gained the right to vote with ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Women organized in 1848 to obtain the right to vote. After the Civil War, the American Woman Suffrage Association advocated for the 15th Amendment to grant suffrage to all women, but to obtain passage by the US Congress and ratification by the states the amendment was drafted to include just black men. That compromise led Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to organize the rival National Woman Suffrage Association, and the women's movement remained divided until the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed in 1890.

At the national level, most suffragist leaders were elite, educated white women. In addition to their personal views, they recognized that racism increased the political difficulty of getting support in the southern states. White men who were not inclined to allow white women to vote were especially resistant to allow black women to vote.

When the National American Woman Suffrage Association held its convention in New Orleans in 1901, it excluded black women from the event. In 1913, Alice Paul organized a National American Woman's Suffrage Association parade in Washington DC just before Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated. Black suffragist leader Ida B. Wells was told at the last minute that the parade would be segregated. She and other women of color had to march at the back of the parade, not with their state delegations. Wells bypassed the order, slipping into the Illinois delegation in the middle of the parade.

Carrie Chapman Catt, the leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, adopted a "winning plan" in 1916. Her approach shifted from the state-by-state strategy, and she sought to get the US Congress to pass an amendment to the US Constitution that would mandate women's suffrage nationwide once ratified by 26 states.

Catt sought support from US Senators who represented southern states. That led to a decision to exclude black women from visible roles in the movement. At one point, she wrote:38

However, as she tried to match her social justice vision with efforts to convince white men from the South to support her, she also wrote that same year in an article for the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP):39

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was segregated from its beginning in 1909, limiting membership to just white women during the suffrage movement. Black women in Virginia had to organize a separate National Association of Colored Women to press for the right to vote.

Opponents of women's suffrage in Virginia claimed that empowering black women would threaten white supremacy. In 1915 opponents highlighted that in 29 Virginia counties, the black female population outnumbered the white female population. The control of state government by the white supremacists in the Democratic Party was threatened, if black women in the 29 "threatened counties" could vote:40

After ratification of the 19th Amendment, Maggie Walker and Ora Brown Stokes led the effort to get 2,410 black women registered in Richmond. Black women began to vote in Virginia on the same day as white women, but faced the same Jim Crow barriers as black men.

Despite claims that the 19th Amendment would lead to "negro rule" as black women went to the polls, the tools developed after the 15th Amendment to block voting by black men were used effectively to block voting by black women. In contrast, white women were not disfranchised as a group.

Racial discrimination affected suffrage advocates even after 1920. The white women reorganized the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia into the Virginia League of Women Voters, holding a meeting in the Senate chamber of the State Capitol on November 10, 1920. No black women were allowed to participate. Black women in Virginia formed the separate Negro Women Voters League of Virginia and then the Virginia State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs.41

The civil rights movement overturned the disfranchisement processes which had been established in the 1902 Constitution and implemented by subsequent state laws and registration/voting procedures. Even before new Federal laws were passed, in 1963 the voters in Dumfries elected the first black person to public office after the end of Reconstruction. John Porter was elected in 1963 to serve on the Town Council.

In 1964, enough states ratified the 24th Amendment to abolish the poll tax in Federal elections. The Virginia General Assembly, anticipating that the poll tax would be eliminated, had adopted another new restriction on non-white voters in 1963. In a special session, the legislators passed a law requiring voters for Federal offices to file a certificate of election demonstrating their residency at least six months to each Federal election.

The requirement to file a residency document six months before an election would have provided a tool to suppress non-white voters in Federal elections. However, the US Supreme Court ruled in 1965 that a residency mandate would make the electorate that was eligible to vote in Federal elections smaller than the electorate that was eligible to vote for the Virginia House of Delegates. That restriction violated Article I, Section 2 of the US Constitution regarding who was qualified to vote ("electors") in races for the US House of Representatives:42

The US Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and Virginia had to relax its racial barriers to voting. Until 1971, the Constitution of Virginia included a requirement to pass a literacy test in order to register to vote. That was a "device," as described in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, that local officials used to discriminate against non-white voters and suppress their vote.

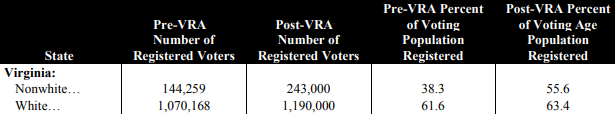

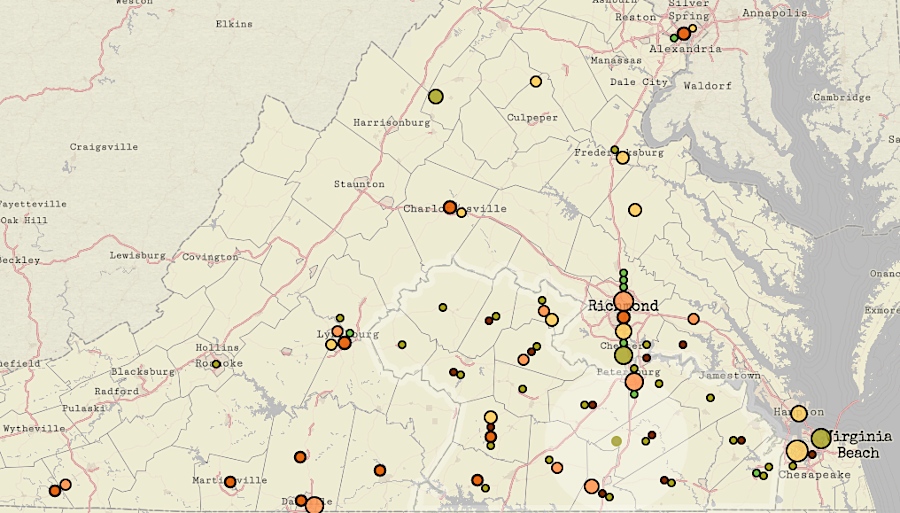

after the US Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the number of non-white registered voters increased dramatically

Source: US Commission on Civil Rights, An Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access in the United States (p.26)

State officials claimed that the 1964 constitutional amendment eliminating the poll tax applied only to Federal elections. Voters in state and local elections were still required to pay $1.50/year for the last three years before they could vote for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, members of the General Assembly, boards of supervisors, city/town councils. Accounting for inflation, in 2020 dollars that was about $130.

The remnants of the poll tax barrier lasted only two more years, however. In 1966, the US Supreme Court ruled in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections that the 14th Amendment blocked use of the poll tax to limit the electorate in state elections. Plaintiffs included Annie E. Harper and three others from Fairfax County, plus Evelyn Butts from Norfolk. She was a seamstress who had not completed high school, but demonstrated her talents as an effective activist for civil rights.

After winning the case abolishing the poll tax for state elections, she registered thousands of new voters. They helped elect the first black member of the Norfolk City Council in 1968, and the first black member of the House of Delegates from Hampton Roads in 1969.

Northern philanthropists and Federal officials combined to create a Voter Education Project, which supported activists who successfully increased back voter registrations. The percentage of eligible blacks who were registered climbed from 24% in 1962 to 62% in 1970.

In 1994, the US Supreme Court ruled that party conventions to nominate candidates could not require payment of a fee. The Republican Party of Virginia was requiring delegates to its statewide convention to pay at least $35, and using that fee to finance the convention. The court ruled that the fee was equivalent to a poll tax, and violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965.43

after the US Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the number of non-white registered voters increased dramatically

Source: Evan Faulkenbury, Mapping the Voter Education Project (VEP)

The 1965 Voting Rights Act initially applied to the entire state of Virginia because less than 50 percent of persons of voting age voted in the presidential election of November 1964. Section 5 of that law required Federal or court review of any change affecting voting within that "covered area."

Between 1965-2013, the US Department of Justice had legal authority to challenge actions by Virginia jurisdictions that might suppress the impact of non-whites on elections.

For example, in 1999 the polling center for the Darvills Precinct in Dinwiddie County burned down. The closest alternative site for a replacement was the Cut Bank Hunt Club, a private facility where most members were African-American. County officials proposed to move the precinct voting site to Bott Memorial Presbyterian Church, a predominantly-white organization at the extreme east end of the precinct.

That church was far from where most African-Americans lived, on the western end of the precinct. The US Department of Justice objected and blocked the shift, citing discriminatory impacts that violated the 1965 Voting Rights Act.44

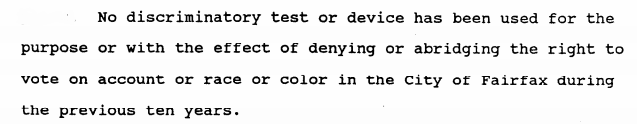

The law allowed counties/cities/towns within Virginia to terminate or "bail out" from coverage by appealing to a special a three-judge panel, if the jurisdiction could prove that it had not discriminated illegally to restrict access to the electoral process within the last 10 years. Ending oversight reduced legal costs for the jurisdictions for routine decisions related to elections, such as relocating polling places or changing boundaries of voter precincts after redistricting.

Virginia sought to have the entire state freed from Voting Rights Act oversight in 1974, but that effort failed. The first local jurisdiction in Virginia to get bailout approval was the City of Fairfax, in 1997. The last to bail out was the City of Falls Church, which received approval in 2013.

in 1997, the City of Fairfax was able to bail out of oversight requirements in the 1965 Voting Rights Act

Source: US Department of Justice, City of Fairfax, Virginia v. Janet Reno (p.7)

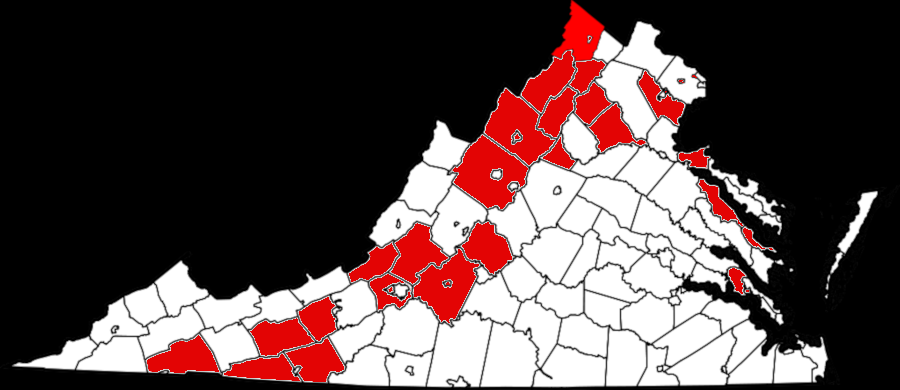

Of the 52 consent decrees authorizing bailout, 32 were for different Virginia cities and counties (including their towns). The Shelby County v. Holder decision by the Supreme Court in 2013 ended the requirement for bailout approval.45

32 Virginia jurisdictions bailed out of oversight requirements in the 1965 Voting Rights Act

Source: Wikipedia, Virginia county locator maps

Despite past discrimination, black candidates have won statewide elections. Counting from Douglas Wilder's run for Lieutenant Governor in 1985, a majority of voters in every city/county in Virginia have supported a black candidate for statewide office.

Dickinson County, with a 98% white population after the 2020 Census and the "whitest" county in Virginia, has voted four times for black candidates. It gave Democratic candidate Douglas Wilder 58% of the vote in 1985. In 2021, reflecting the political shift in partisan support, voters in Dickinson County gave Republican candidate Winsome Earl Sears 80% support in her race for Lieutenant Governor. The other 20% in 2021 voted for Haya Ayala, who described herself as an "Afro-Latina" candidate. Since in the 2021 Lieutenant Governor contest both political parties nominated black candidates and they were the only names on the ballot, people unwilling to vote for a person of color had to write in another name or skip the opportunity to vote for Lieutenant Governor.

After 2022 Dumfries had an all-black Town Council, the first in Virgina history. In the 2024 General Assembly, the chairs of the two "money" committees, the House of Delegates Appropriations Committee and the State Senate Finance and Appropriations Committee, were both black.46

Dumfries voters elected an all-black Town Council in 2022

Source: Facebook, Councilwoman Selonia Miles (April 25, 2023)

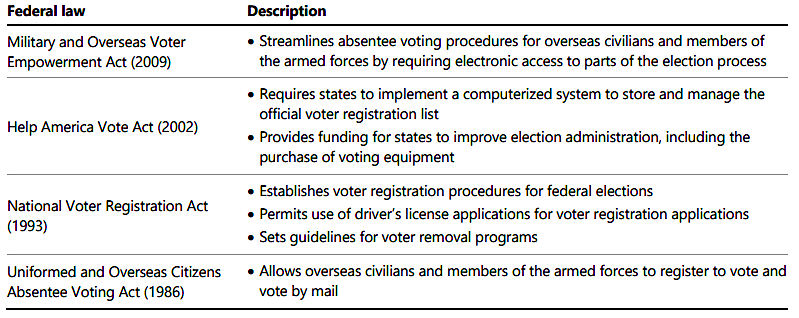

Not all constraints on voting qualify as "disfranchisement." Federal laws allow state and local governments to define who is a "qualified" voter entitled to participate in an election. Voter rolls may be purged to limit the names in a poll book to just those who are qualified, enabling election officials to more-quickly process voters, and states may require specific forms of identification when a voter appears in person at a precinct.

four Federal laws affect voter eligibility, and limit voter suppression techniques

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Table 1-1)

At the end of October, 2019, there were 5,628,989 registered voters in Virginia. As people move out of their voting district, where they are eligible to vote changes. Most people who move fail to notify the registrar for their old residence. The Virginia Department of Elections gets data from various sources and exchanges data with other states to identify if someone has registered in another location, and thus should be removed ("purged") from the poll books for their old residence.47

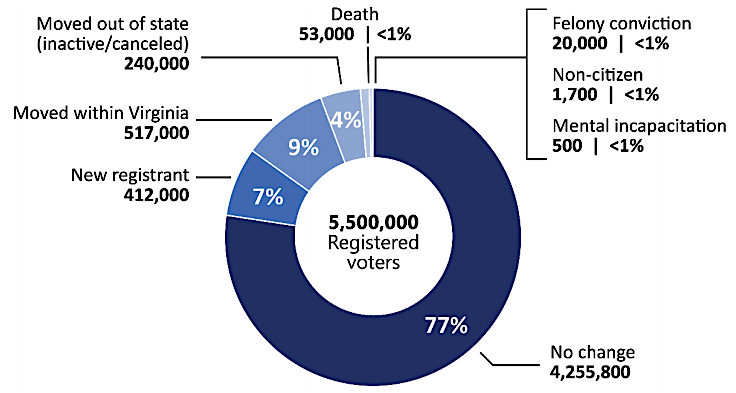

over 20% of Virginia's voter registration list may be outdated each year (voter registration and removal data, FY2017)

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Figure 2-1)

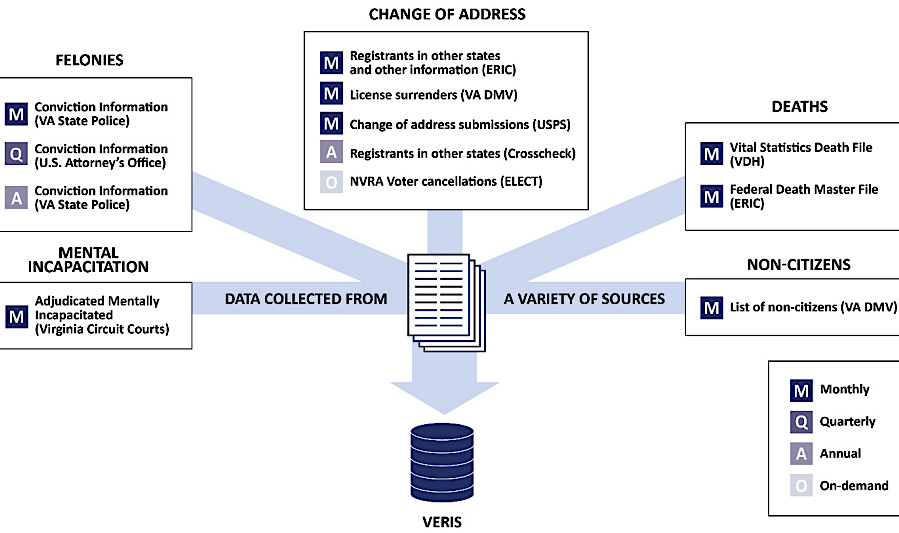

the Virginia Department of Elections uses multiple sources to identify if General Registrars should be alerted about a voter's eligibility

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Figure 2-2)

The Virginia Department of Elections oversees local registrars and Electoral Boards because:48

Even legitimate efforts to ensure voters are qualified can become controversial. In 2019 the Fairfax County registrar rejected 171 registration applications from George Mason University (GMU) who registered using campus mailbox numbers and a general university address, rather than identify a specific dormitory name or private home address.

Registrars are required to determine the residence of voters, in order to determine in which precinct (and for which elected offices) they should vote. The university allowed off-campus students to have a campus mailbox, so the registrar was unable to accurately determine the correct voting precinct for those 171 students. The polling place at GMU's Merten Hall was not appropriate for at least the three students who registered using their campus mailbox, but were known to live in Prince William County.

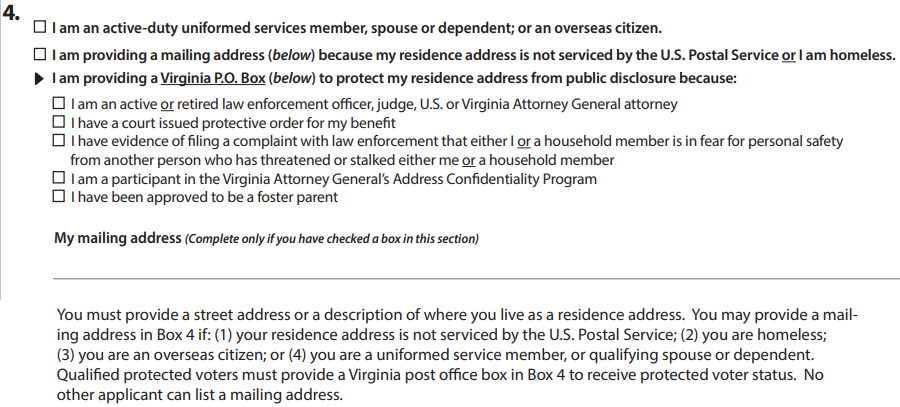

Virginia allows homeless people and others to register to vote, without citing a specific physical address of their residence

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Virginia Voter Registration Application

The Fairfax registrar agreed to allow the 171 student voters to provide a correct address by the Saturday prior to the election. A US District Court judge then ordered that any of them who failed to provide a more-specific address by that deadline could still vote on Tuesday, using a provisional ballot. Their votes would be counted if they provided the specific address by noon on the Friday after the election.49

Requirements for voting in person were loosened by most states during the 2020 election, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. After President Trump claimed the election was stolen and cited false claims regarding voter fraud, many Republican-controlled state legislatures sought to limit early and absentee voting, impose stricter identification requirements, reduce hours of voting, and roll back other mechanisms that had increased turnout. The Georgia legislature even made it illegal to provide water or food within 25 feet of any voter standing in line, claiming the changes were needed to protect election integrity.

The conventional wisdom was that residents with a low commitment to voting were predominantly Democrats. Making it harder for everyone to vote would be a "neutral" constraint on the surface that would be approved by the US Supreme Court using the same logic as in the late 1800's, but the constraints would have a predominantly anti-Democratic impact.

In Virginia, all four candidates for the Republican nomination for governor in 2021 supported reinstating voter ID requirements and eliminating drop-off ballot boxes. One continued to repeat Donald Trump's false claim that voter fraud caused his loss in the 2020 presidential election. Democrats labelled the efforts as voter suppression, and claimed that supposedly race-neutral restrictions were designed to impact primarily minority voters.50

None of the Republicans in the General Assembly supported the Virginia Voting Rights Act. It established in state law many of the Voting Rights Act provisions passed by the US Congress in 1965 but invalidated by the Supreme Court in its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, including requiring pre-clearance by state officials before localities could change district boundaries and affect minority voters.

The Democratic Majority Leader in the House of Delegates, the first black person to hold that job, noted that her ancestors had fought hard to gain voting rights. The Washington Post described how Virginia General Assembly took action to maintain voter access to the polls:51

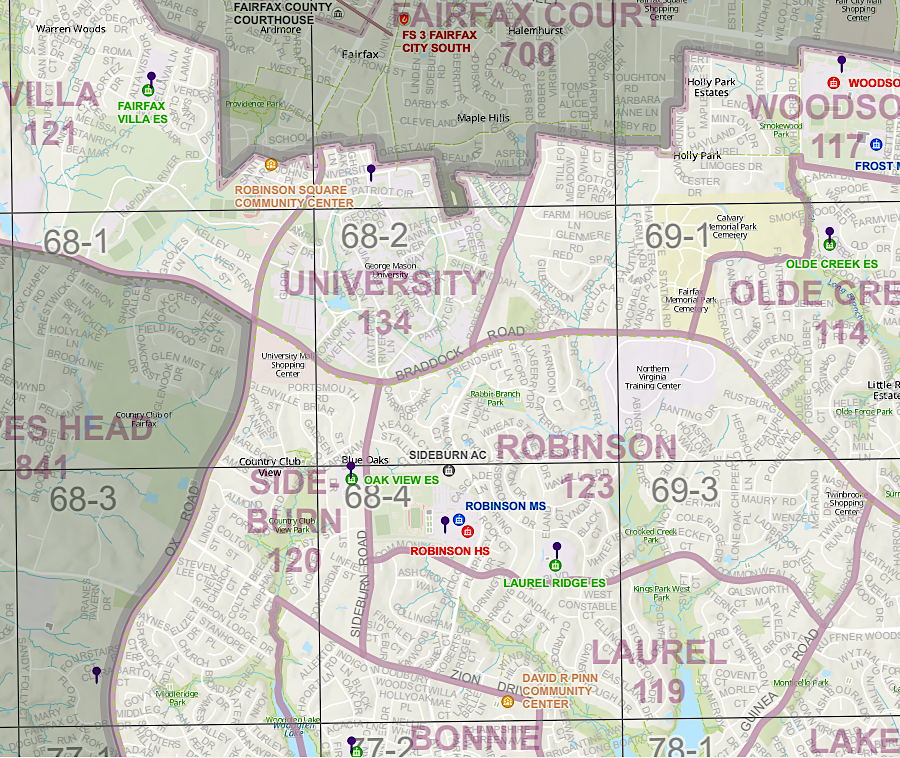

students who physically live on the Fairfax campus of George Mason University are assigned to Precinct #134

Source: Fairfax County, Braddock Supervisor District

At James Madison University, the campus is divided into two precincts. Students must include the name of their dorm when they register in Harrisonburg, in order to be assigned to the correct precinct.

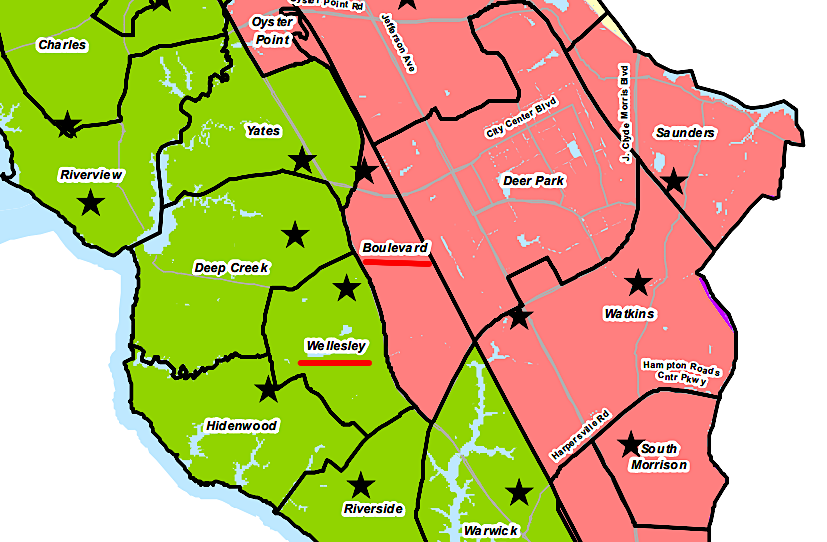

Redistricting in 2019 split the Christopher Newport University campus in Newport News. Campus housing on the west side of Warwick Boulevard ended up in the 94th District for House of Delegates, while units on the east side of the highway ended up in the 95th District. The roughly 600 students registered to vote all used the same address, where mail is sent to students. The Newport News registrar, with assistance from university officials, tried to contact all those registered voters via mailings, emails, phone calls, and text messages in order to determine whether they vote in the Wellesley precinct in the 94th District or the Boulevard precinct in the 95th District.

The "every vote counts" mantra was especially relevant in the 94th District. In the 2017 election, the race ended in a tie vote. The race was decided by placing the names of the two tied candidates into a bowl, and then drawing out one name to pick the winner.52

redistricting in 2019 split Christopher Newport University housing between the 94th District (Wellesley precinct) and the 95th District (Boulevard precinct)

Source: City of Newport News, House Of Delegates Districts - Voter Precincts, Polling Places

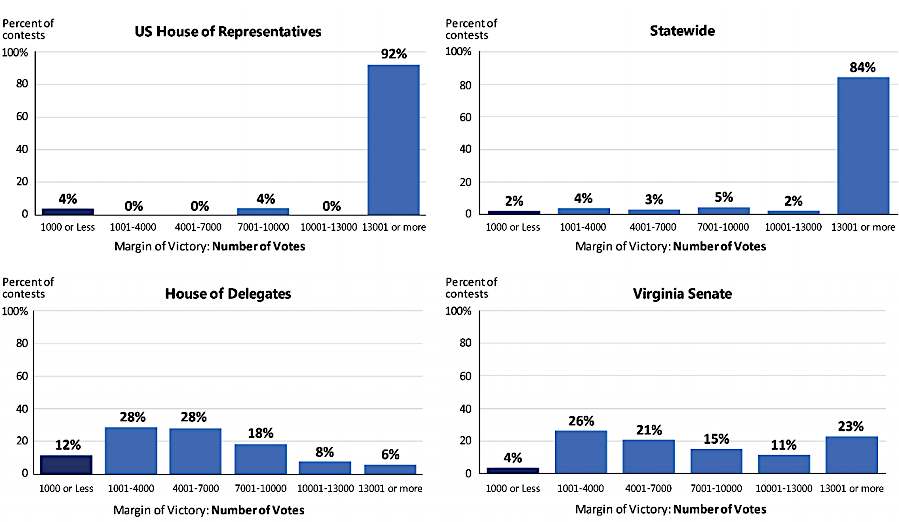

However, large-scale disfranchisement would be necessary to make a difference in most races. Between 2008-2017, the vast majority of contests for state and Federal offices were decided by margins of more than 1,000 votes.53

most contests for state and Federal offices between 2008-17 were decided by more than 1,000 votes

Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections (Appendix C)

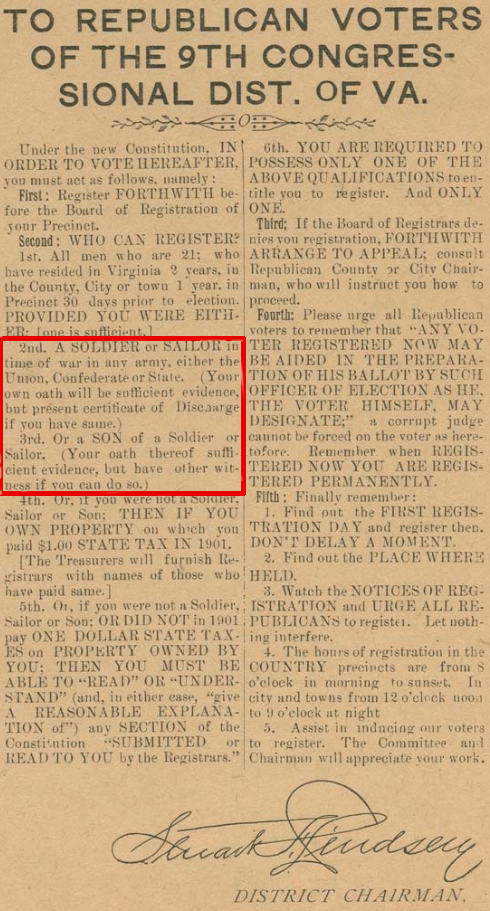

in 1907, only white males could vote in the Democratic primary

Source: Virginia Chronicle, Culpeper Exponent (May 10, 1907)