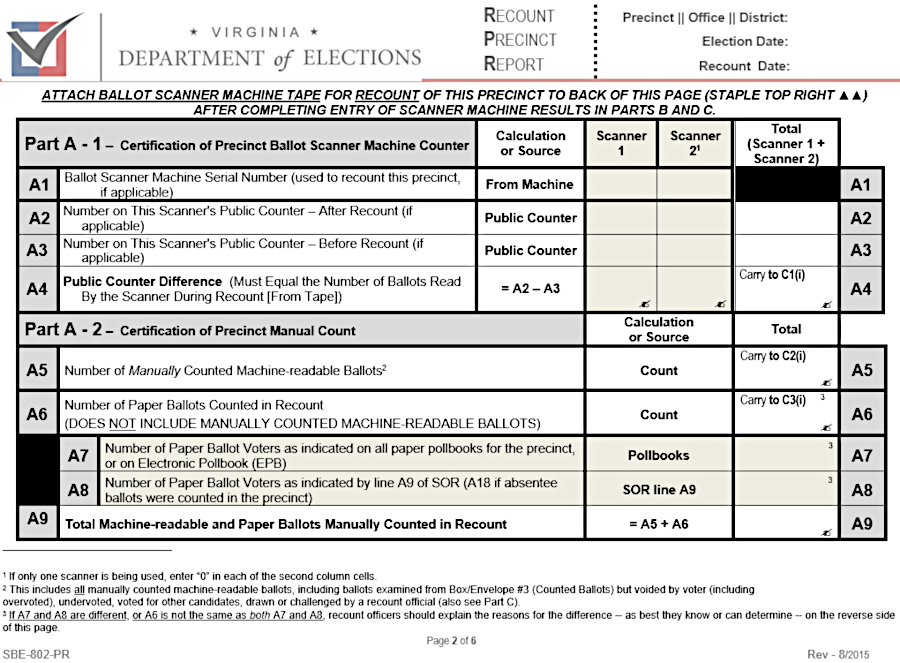

recounts require a precinct by precinct reassessment of vote totals

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Recount Precinct Results

recounts require a precinct by precinct reassessment of vote totals

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Recount Precinct Results

After all voters waiting in line at 7:00pm have cast a ballot, polls close. Once all voting is over, the counting begins.

Those who voted after 7:00pm must cast a provisional ballot, but it will be counted that evening. Voters who cast their ballots as absentees or in the early voting process typically mail them or deliver to "drop boxes." In-person early voting is provided in all jurisdictions at the central precinct, and in some at temporary satellite offices. Those votes are counted only after 7:00pm on election night.

Election officers at each precinct will read the results from each electronic voting scanner. The number of votes recorded by the scanner should match the number of paper ballots it collected. However, the number of votes for each office will not match the number of ballots processed. Voters can choose not to mark any preference for an office, or to vote for only one person when there are multiple seats to be filled.

"Undervotes" are common, but there should not be more votes tabulated than there were voters at the poll (plus absentee ballots, in precincts where those are counted). An excess number of votes indicates a mistake has occurred at the polling place. Excess votes may occur when an election officer gets distracted for a moment, and fails to record in the polling book that they just handed a ballot to a voter. Records will not show that voter participated in the election, but their vote will be mixed in with all the others and still be counted.

NOTE: The Virginia Department of Elections uses the term "overvote" to describe a different problem, when a voter marks a ballot for too many candidates in a race. For example, in a House of Delegates race, there will be just one winner. A voter who marked the ballot for two candidates has created a overvote. In that case, no vote will be recorded for either candidate. If there are three Soil and Water District board vacancies and a voter marks the ballot for four candidates, that too will be an overvote which is not counted for that race.

Not all ballots completed at the polling place go through the scanners on election night. Provisional ballots are counted by hand, rather than by the machines. Voters who came to the precinct but lacked sufficient identification will be allowed to mark up a provisional ballot. They are placed in a secure ballot box at the polling place, and after 7:00pm the number of the still-unopened provisional ballots is reported to election headquarters.

If voters submit a copy of the required identification by noon on Friday after the election, or apply for a Virginia Voter Photo ID Card and submit a a Temporary Identification Document by that deadline, then the provisional ballot will be opened and the vote will be added to the final totals.1

After the last voter has completed their process and the polls close, election officers collect a tape documenting the results from each scanner. The votes are tabulated from each tape, and unofficial results are announced publicly at the site and transmitted to election headquarters for the jurisdiction. If a candidate or political party has designated official observers for the count, they may leave the polling place only after the election officials have submitted the unofficial results, so the Electoral Board provides complete (unofficial) results without fragmented tallies emerging in stages from separate precincts.

Election workers document the tabulated vote on a Statement of Results sheet, and all officials sign the Printed Return Sheet. The precinct captain transmits the results to the Electoral Board at election headquarters. There, the registrar enters results into the Virginia Election and Registration Information System (VERIS), and the Virginia Department of Elections publishes those "unofficial" results on a website.

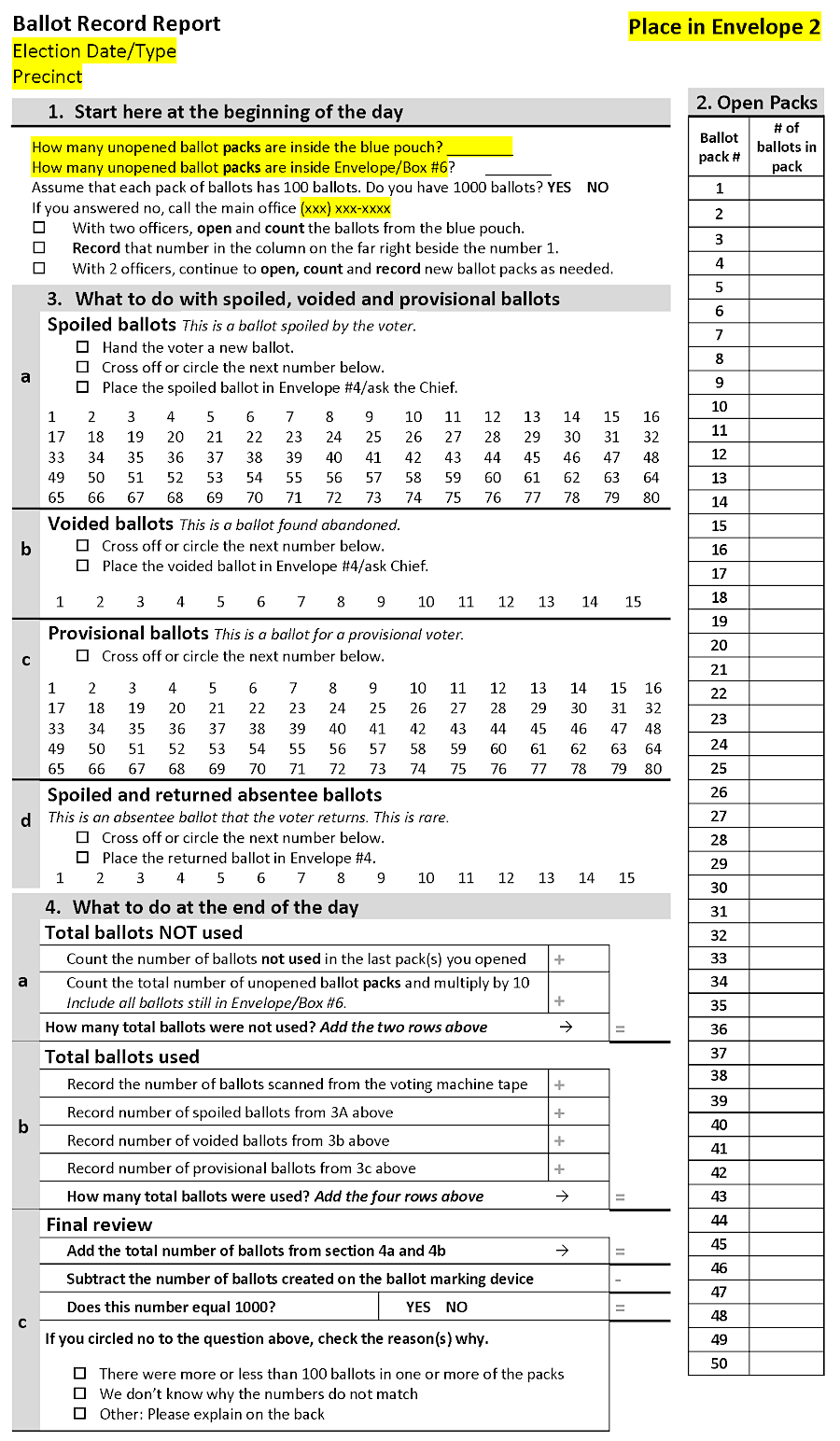

Vote counting procedures assume there may be a recount. Step-by-step procedures for closing up the poll include directions for placing unused ballots, scanner tapes, provisional ballots, and other items into a dozen separate envelopes. Electronic scanners that recorded ballots are sealed to ensure no tampering can occur in secret.

Ballot security is a Standard Operating Procedure for all elections, but especially significant for those in which there will be a recount. A ballot record report gets filled out at each polling place at the beginning, during, and end of an Election Day. Department of Elections guidance is clear:2

A losing candidate can request a recount only after the results have been certified. The Virginia Department of Elections certifies results for Federal offices and General Assembly races, plus the offices of Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General. The state also certifies results for races that include more than one jurisdiction, such as the Commonwealth Attorney serving Manassas, Manassas Park, and Prince William County. Local Electoral Boards certify results for local offices within just that jurisdiction, such as races for county supervisor or city council. Once races are certified, "unofficial" results become "official."

Recounts are permitted only if there is a difference of one percent (1%) or less of the total votes cast for the winner and a losing candidate listed on the ballot. If the losing candidate was a write-in candidate, a recount is allowed if the vote difference was 5% of less.

If the margin of victory is 0.5% or less, the local jurisdiction will pay for the recount costs. If the margin is between 0.5%-1%, the candidate petitioning for the recount must pay the costs. If the recount changes the results and the petitioner is declared the winner, then in that circumstance the local jurisdiction must pay for the recount even if the initial margin was between 0.5%-1%.

Recounts are not automatic. The recount process is triggered only if a losing candidate files a petition with the local Circuit Court within 10 days of the vote being certified. For statewide races, recount petitions are filed with the Circuit Court for the City of Richmond. A three judge Recount Court is formed. The Chief Judge of the circuit is one member, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia appoints two others.

The Recount Court judges define the recount procedures, such as the location where the ballots will be recounted. The court chooses election officers, drawing from the pool of those who had worked the polls for the election. The political parties nominate which officials they want to serve in the recount process, anticipating that interpretation by those officials of some disputed ballots could determine the winner.

At the start of a recount, the clerk of the court has custody of the ballots that were collected on election night from all the precincts. The ballots are brought to the location of the recount. Those initially counted by hand are re-counted by hand, while all others are run through optical scanning machines again.

The machines are programmed so votes for only the race in question are counted. Ballots with write-ins, undervotes, and overvotes for the specific race are separated. Those separate ballots are then hand-counted, while ballots accepted by the machines are not handled again.

Voting machines were already in use back in 1989 when the race for Governor required a recount. In the initial tabulation after polls closed on November 7, Democrat L. Douglas Wilder defeated Republican J. Marshall Coleman by 0.4%.

In the 1989 recount, 1,700 Democrats and Republicans were recruited to rechecked ballots in every jurisdiction. The results were then delivered to Richmond, where six state officials, a pair of auditors, and then lawyers tabulated the totals again.

In many jurisdictions, the total number of election day voters that had been reported by local officials did not match the total number of ballots recorded by the machines. The differences may have reflected a failure to record when ballots had been taken outside to people that were physically unable to walk into the polling places.

To account for the difference, ballots were randomly eliminated to make the total match the number of voters recorded by precinct officials. Wilder ended up with 203 fewer votes and Colemain lost 90. In the end, the winning margin was 6,741 votes.

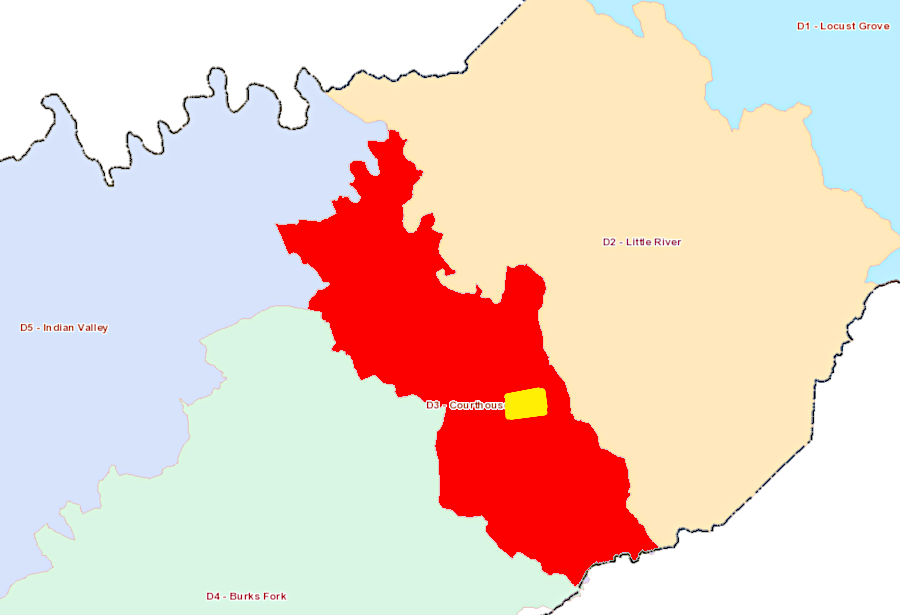

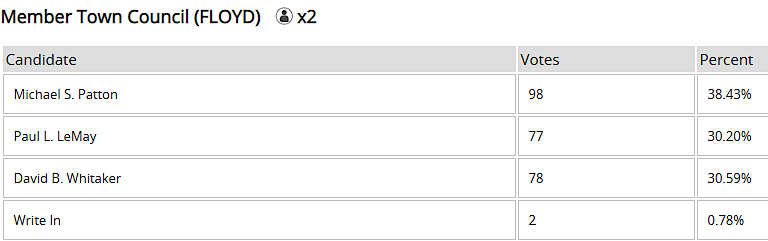

In 2019, there were two seats to be filled on the Town of Floyd Council. The top three candidates received 98, 78, and 77 votes, and the one with just 77 votes requested a recount.

The town is a small portion of the Courthouse magisterial district, one of five in the County of Floyd. In the recount, all ballots cast in the Courthouse magisterial district on election day, plus absentee ballots for that district, were run through a scanner programmed to count just votes for the Town Council seats. If a voter did not vote for two of the candidates in the Town Council race, or used the write-in line to vote for another person, that ballot was treated as an "undervote," spit out of the scanner, and counted by hand.

No votes were disputed in the recount. Election officials required 4.5 hours to assess the 1,155 ballots from the Courthouse District. No ballots were disputed, and the 78-77 vote total was upheld. The three judges who formed the Recount Court were not required to resolve how to county any challenged ballots.3

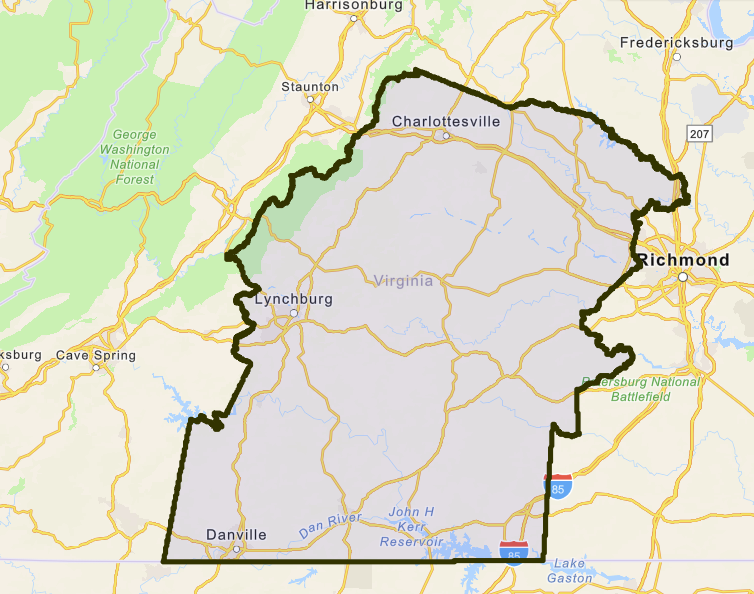

the Town of Floyd (yellow) is a small part of the Courthouse District (red), and in a 2019 recount only votes for the Town Council race were counted when Courthouse District ballots were run through the scanners

Source: Floyd County, iGIS

a recount in the 2019 Floyd Town Council race did not change any votes, leaving a one-vote victory intact

Source: Virginia State Department of Elections, 2019 November General - Official Results

The debates in a recount revolve around the hand-counted ballots. A pair of recount officials, one a Republican and one a Democrat, sit together at a table and assess each ballot rejected by the scanner. They determine if the ballot should be counted and, if so, the intent of the voter.

Guidance on determining a voter's intent is provided by the "Ballot Examples for Handcounting Paper or Paper-based Ballots for Virginia Elections or Recounts" from the Virginia Department of Elections, but human judgment is still a key factor. A member of the two-person recount team may challenge an interpretation by the other member at that table.

At the end of the process, the lawyers for the candidates present the challenged ballots to the Recount Court judges, with their interpretations of how the marks indicate support for their candidate, and the three judges make final decisions. If the lawyers decide the challenged ballots will not change the election results, they can shortcut the last stage.

In Orange County, once the Electoral Board counted the provisional ballots and announced the official results, the 2019 Commonwealth's Attorney race ended with a winning margin of just 28 votes. In the recount, all ballots were run through five reprogrammed scanning machines, all ballots spit out by the machines were assessed by the two-person recount team assigned to each machine - and only one ballot was challenged. The attorneys for the losing candidate then decided not to argue their interpretation of the voter's intent in front of the three recount judges, because even a favorable decision would not affect the results of the election.4

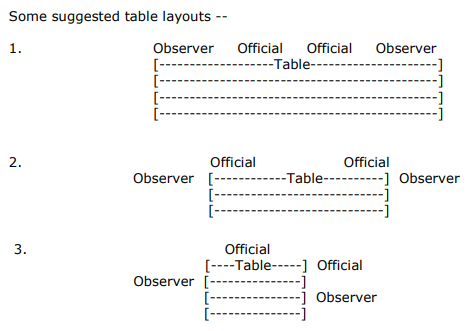

observers for candidates involved in a recount can sit at tables and watch election officials assess ballots

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Virginia Election Recounts - Step-by-Step Instructions

In 2019, the official results for the 83rd District showed just 27 votes separating the top two candidates. The losing candidate filed for a recount, and one of his representatives commented:5

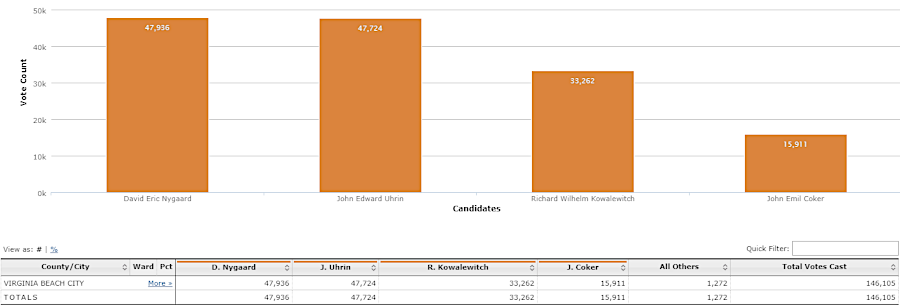

in 2019, there was a recount in the 83rd District for the House of Delegates after initial counting showed a gap of only 27 votes

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 2019 November General - Official Results

Almost all of the 83rd District was in the City of Virginia Beach. The registrar for the city had overseen recounts for three city council races in 2018. Losing candidates in the Beach District, Bayside District, and for an at-large seat petitioned for recounts.

For the most simultaneous recounts in one jurisdiction in Virginia history, the Virginia Beach registrar rented three high speed ballot counters that could process 200 ballots a minute. The machines were programmed to spit out ballots with undervotes and overvotes, and those were then hand-counted by the election officials.

Virginia Beach had a complicated process to elect its 11 members of the city council, stemming from the merger of the City of Virginia Beach and Princess Anne County in 1963. Three members and the mayor serve at large, but there are residency requirements for the other seven members. All voters within the city vote for all seats, but the candidates for the Bayside, Beach, Centerville, Kempsville, Lynnhaven, Princess Anne, and Rose Hall seats must live within the boundaries of those districts. The city has not chosen to mimic the process used in Richmond and other jurisdictions, by drawing ward boundaries and allowing residents to vote for a representative from just their ward plus at-large members.

In 2018, voters across the city could cast one vote for the Beach District representative and one for the Bayside District representative, and also vote for two candidates serving at-large. The counting machines spit out any ballot where voters did not choose the correct number of candidates for each of those offices, and undervotes were common on the 100,000 ballots cast by voters.

The judges who determined the procedures for the recount process decided that ballots would be rescanned just once. Any ballot spit out by the machines would be examined just once to tabulate the votes for the three races. At each of the 10 tables, two recount officials would count votes for the Beach District race, two for the Bayside District race, and two for the at-large race.

Whenever a pair of officials disagreed on how to count a ballot for one of the races, a challenge tab would be placed on that ballot and it would receive a second review. In theory, each of the three pairs of officials could disagree on how to count each race on a single ballot. In that case, three challenge tabs could be placed on a single ballot.

Candidates complained that conducting three simultaneous recounts over four days was too chaotic. Each candidate was allowed to have one observer in the recount room to oversee the process, but the use of three ballot counting machines meant that the observers could watch over only one-third of that step in the recount process.6

The recounts altered vote totals, but not the results, in the three city council elections. In the Beach district, each candidate received over 47,000 votes. After the recount, the winning margin changed from 212 to 163 votes. There were over 70,000 votes for each candidate seeking the Bayside District seat. The winning margin increased from 503 votes to 530 votes. The at-large candidates each got over 56,000 votes, and the difference between the winner and loser dropped from 347 votes to 325 votes after the recount.7

In a later twist, the winner of the Beach District seat was later disqualified and removed from City Council. A three-judge panel from the Circuit Court ruled that he had moved out of the district, and did not meet the residency requirement. The losing candidate who had asked for a recount initially sought to be appointed to serve until the next election, but then withdrew his name from consideration.8

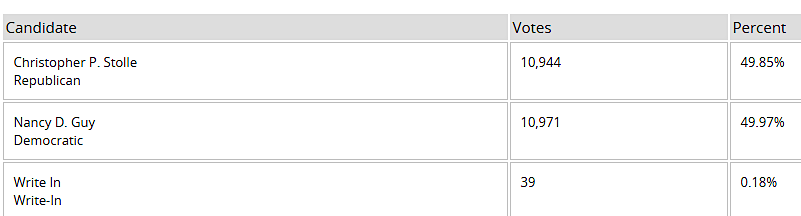

the 2018 election results for the Beach District, where the winning margin was less that 0.5%

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 2018 City Council General Election

The 2024 recount of the City of Roanoke mayor's race required 15 hours, spread over two days. Over 40 election officers and observers participated in a process that ended up affirming the initial results, in which Joe Cobb defeated David Bowers. The process started with stacking 20 boxes of paper ballots on the left side of a courtroom, and finished with the ballots repackaged into those same boxes on the right side of the courtroom:9

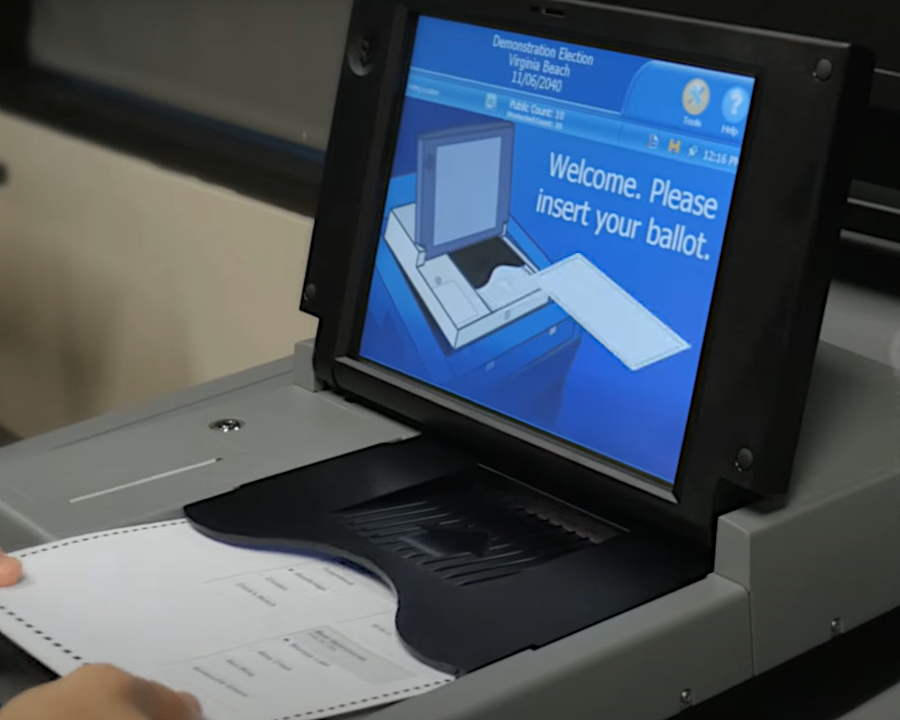

in a recount, ballots are scanned by the same machines used in the election

Source: Virginia Beach Voter Registration and Elections, DS200 Voting System

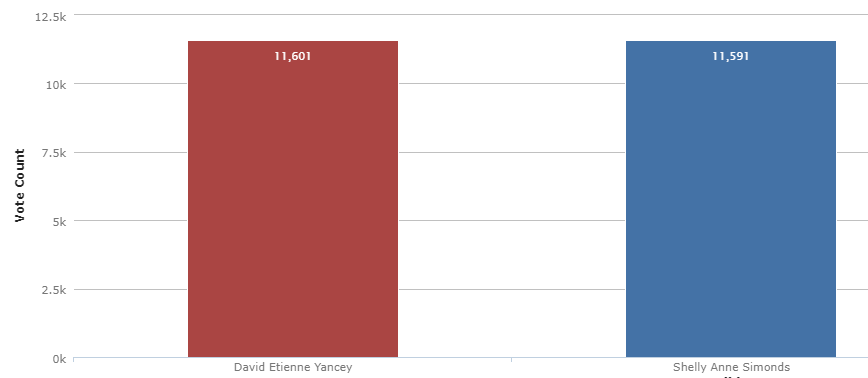

Virginia's most famous recount occurred in 2017, for the 94th District in the House of Delegates. The official certified vote total gave the incumbent, Del. David Yancey, a 10-vote victory. The recount altered the results, and the challenger Shelly Simonds was declared to be the winner by just one vote, 11,608-11,607. She was a Democrat, and her victory meant the House of Delegates would have 50 Democrats and 50 Republicans when the General Assembly next met in 2019.

An observer played a key role in that recount even though, during the process, they can't communicate directly with the election officials who are agreeing to validate/invalidate ballots - or disagreeing, and creating "challenged" ballots for the three Recount Court judges to decide. In the 2017 recount for the 94th District, an observer noted the discomfort of an election official who chose not to challenge a ballot. After the recount ended, the observer contacted the official.

That led to a message sent to the Recount Count the following morning, requesting the judges re-examine the ballot even though it had not been challenged during the recount. The three judges decided to count the ballot, and that decision created a tie 11,608-11,608 vote. The judges declared there was no winner based on the votes counted.

The ultimate winner in the 94th District was determined by the chair of the State Board of Elections. Names of the two candidates were placed inside film canisters, and the chair chose at random one of the canisters from a bowl. In that very public process, the incumbent's name was in the first film canister drawn from the bowl. As a result, the Republican Part retained control of the House of Delegates by a 51-49 majority.

The loser had the option of contesting the election after the Recount Court had concluding, triggering another court process which is separate from a recount. She chose instead to start campaigning for the next election. In 2019 she ended up winning a clear victory, and as a result of other races the Democrats took control of the House of Delegates with a 55-45 majority.10

in the 94th District in 2017, after votes were certified but before the recount, the incumbent David Yancey had won by 10 votes

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 2017 House of Delegates General Election - District 94

The 2005 Attorney General race is the closest statewide race in Virginia history, based on final vote totals. The certified results from the local Electoral Boards gave Republican Bob McDonnell 970,886 votes and Democrat Creigh Deeds 970,563 votes.

Not surprisingly, the losing candidate sought a recount. After the Recount Court completed its process, McDonnell gained 37 votes and ended with a 360 vote margin of victory.

During the 2005 recount process, both candidates were provided state funding and space for their transition teams. In the end, McDonnell described the process as "6 1/2 weeks of overtime."11

In the 2013 election for the Attorney General's office, certified election results from the local Electoral Boards showed that Democrat Mark Herring had defeated Republican Mark D. Obenshain by just 165 votes out of 2.2 million total. Obenshain's team suggested vote handing in Fairfax County had been irregular, and considered the option to ask the General Assembly to determine the winner after the recount.

The recount began on Monday, and Herring's majority grew to over 800 votes. The three-judge Recount Court was being asked to determine the intent of voters on less than 120 challenged ballots when Obenshain conceded the race on Wednesday, before the recount was completed. It was clear that if Obenshain won every challenged ballot presented to the judges, Herring still had a majority of the votes. The Recount Court judges did not have to make a final ruling, and the Virginia State Board of Elections ultimately declared Herring the winner by 907 votes after all jurisdictions reported their recounted numbers.

Recounts are authorized for close races that do not involve candidates. A recount of a voter-initiated referendum can be triggered by a petition from 50 voters qualified to vote on the issue, if the "yes" and "no" votes were within one percent or the difference was less than 50 votes. The petition is presented after votes are certified to the local Electoral Board or, for a recount of a statewide referendum, to the Virginia State Board of Elections.12

Candidates with a vote total within 0.5% of the winner may choose to concede without a recount. In the 2006 US Senate race, Republican George Allen finished with 1,166,277 votes. His opponent, Democrat Jim Webb, had 1,175,606 votes. There were an additional 28,562 votes for a third-party candidate and write-ins.

The incentive for a recount was high, because the race would determine which party would control the US Senate. After the 2006 election night there were 50 Democrats and 49 Republicans. If George Allen managed to win the Virginia seat through a recount, the US Senate would be evenly split - but because Vice President Dick Cheney was a Republican, that party could end up in control.

As local Electoral Boards certified their unofficial returns from election night, Webb's margin grew to a point where Allen decided a recount was not worth the cost. Though the state would fund the payments to election officials because the margin was closer than 0.5%, each candidate had to absorb the costs of their teams of lawyers and observers. Allen conceded, acknowledging that neither he nor Webb had over 50% of the vote:13

For some years before 2017, voters used direct-recording electronic machines (DREs) to cast their ballots. A recount involved re-running the machine, rather than processing paper ballots. Since 2017, all election recounts are done by running the ballots back through the voting machines. That process allows recount officials to debate the validity of individual ballots and potentially change the outcome of an election, as occurred in 2017 in the recount for the 94th District of the House of Delegates.

Recount Count judges order that election machines be programmed differently than for a primary or general election. The machines do not tabulate votes for candidates other than the winner and the challenger in the one specific race in question. Ballots that were filled out correctly are counted by the machines, but they reject all ballots with write-in votes. The machines also reject ballots in which voters did not make selections in the contested race (undervotes) or made too many selections (overvotes). The ballots rejected by the machines are then tabulated by the recount officials. If there are contested ballots, the three judge Recount Court determines how to count them.

There were three other recounts in 2017, one in 2019, two in 2021, and one in 2023 for House of Delegates seats. No other recount in a general election has altered the outcome since 2017.14

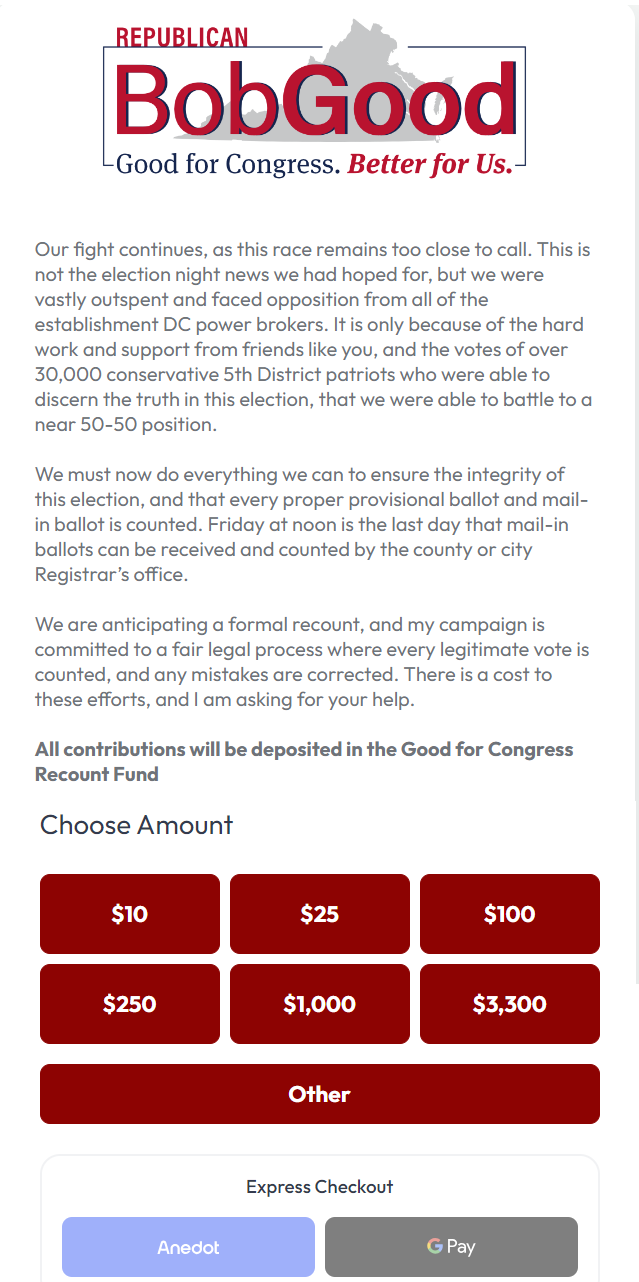

In 2024, the losing candidate in the Republican primary for nomination for the Fifth District US House of Representatives seat chose to pay for a recount. Incumbent Rep. Bob Good lost to State Senator John McGuire by 374 votes out of nearly 63,000 total votes. That was a 0.6% margin, so he had to provide nearly $100,000 to get the ballots rescanned.

The Federal Election Commission authorized him to use funds in his general election account to pay for the recount, but he had to ask donors for their approval. General election funds are legally separate from the funds in primary election accounts. That separation allows supporters to double their individual contributions, which are limited to $3,300 per election.

Rep. Good's campaign would be reimbursed if the recount changed the results of the election, but only for the costs of the public election officials. Candidates requesting a recount are not reimbursed for the private costs they incur to recruit volunteers and pay for observers and lawyers.

On August 1, 2024, the 24 jurisdictions in the Fifth District processed ballots again. The optical scanners were set to zero at the start before recount workers unsealed bags, precinct by precinct, and put them through. Bins collected the scanned ballots, and they were emptied back into the precinct-specific bags before the next set of ballots were scanned.

In Lynchburg, one scanner recorded only 868 ballots when the election night results had reported 869 ballots. The problem was solved when the missing Republican primary ballot was found in the bag holding Democratic primary ballots.

The scanners during the recount registered a few votes differently than on election night. The sensitivity of the machines is not 100% consistent. On occasion an oval on the ballot that was not completely filled in by a voter, perhaps because they used an "X" or a checkmark, will be recorded differently by a different scanner. Under Virginia law, the ballots are scanned only once in a recount. The recount vote total becomes official even if different from election night results; ballots are not rescanned a second time in a recount.

The scanners are considered authoritative. However, a hand recount of a precinct must be done if the total number of ballots recorded in the recount differs from election night. Local officials can also order a recount of a precinct if the vote totals have changed, even though the machines recorded the same number of ballots.

That process reduced State Senator John McGuire's margin, but only by four votes. A fellow conservative member of the US Congress, one of many who supported the challenger in the primary rather than the incumbent, noted that Rep. Good would not be reimbursed:15

after paying $88,918 for a recount in the primary election for the 5th Congressional District in 2024, Rep. Bob Good ended changing his defeat total from 374 down to 366 votes

Source: Representative Bob Good, Virginia, District 5

After the final decision by the Recount Court, the Good campaign objected to some of the costs it was asked to pay by different jurisdictions. The local jurisdictions were authorized to charge for election officials to transport poll books and ballots, but the Good campaign claimed it was being assessed for normal commuting costs of those officials and also for costs of sheriff's deputies to accompany them. The three judges on the Recount Court required five of the 24 jurisdictions in the Fifth Congressional District to attend another hearing, in order to finalize the bills.

Mecklenburg County also discovered after the court's final decision that its original recount certification sheets for two precincts had incorrect numbers in some fields, though the overall total was not affected. The county's General Registrar was required to bring all the hand counted ballots back to the court for the additional hearing.

The General Registrar for the City of Danville also was required to provide a ballot which was reported correctly to the Recount Court as a vote for Good, after initially being recorded as an undervote. The court's total numbers had treated the ballot still as an undervote. The court's efforts to address every questionable detail required the registrar to drive 130 miles for the hearing.

In a revised decision on August 28, 2024, the Recount Court identified transcribing errors and adjusted the results. State Senator John McGuire ended up defeating US Representative Bob Good by a margin that was four votes smaller, 366 instead of 370 votes. The two stages of the recount added a total of eight votes for Good.

That change did not reduce the winning margin to 0.5% or lower, so the Good campaign still was required to pay for the recount. The three judge court did reduced the bill for the recount process from $104,000 to $88,918, by disqualifying some charges. The $2,800 billed for advice from Lunenburg County's county attorney was judged to be a normal county expense and eliminated from the bill. However, Good's request to pay for just snacks rather than full meals during the extra counting of the ballots was rejected.

Even before the final tally, Good announced he was running for the 5th Congressional District seat again in 2026.16

Rep. Bob Good had to provide nearly $100,000 to fund the recount that he requested in 2024

Source: Bob Good for Congress

each polling place completes a Ballot Record Report at the beginning, during, and end of Election Day, to track ballot use and facilitate audits

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Ballot Record Report (August 2018)