Electoral Boards, General Registrars, and the Election Process

Electoral Boards and the General Registrar they hire are responsible for managing the voting process, both absentee and in-person at polling places

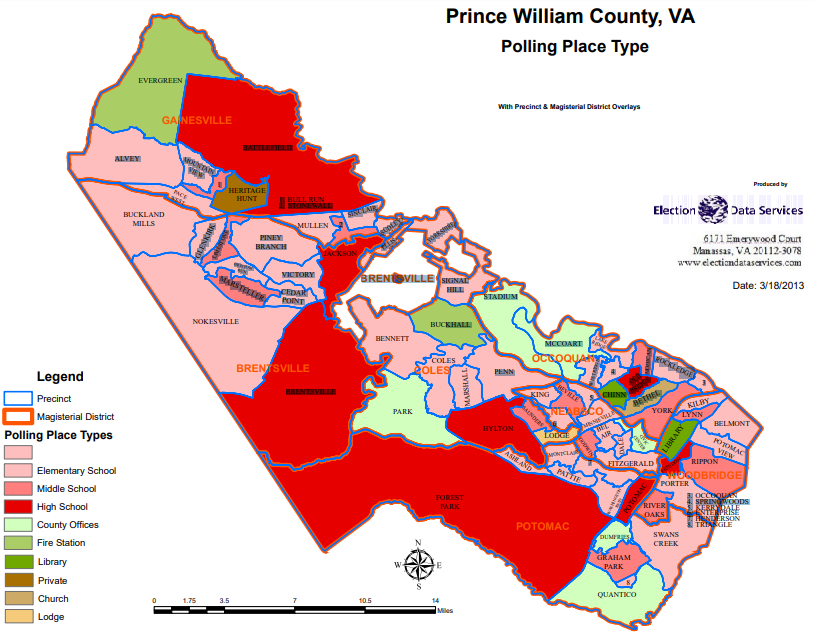

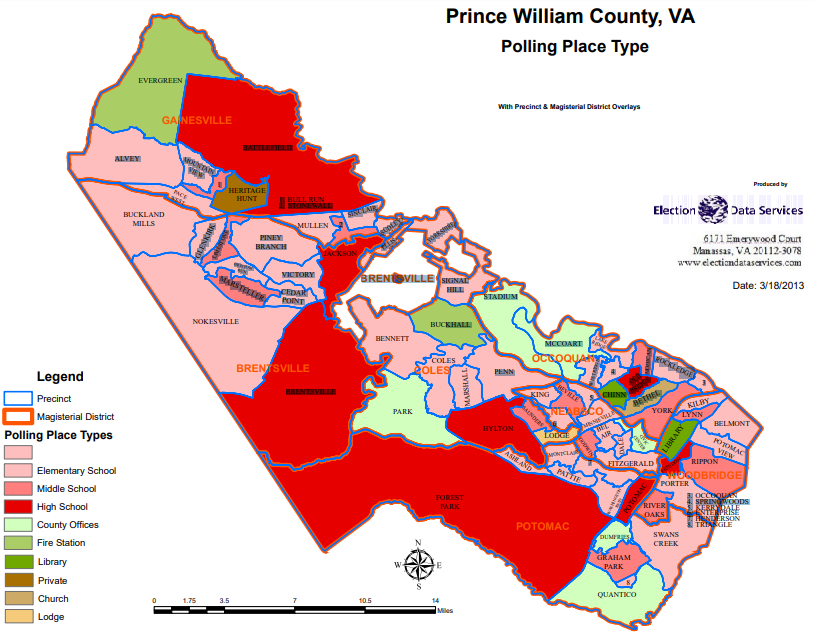

Source: Virginia Board of Elections, Prince William County, VA: Analysis of Voting Data from November, 2012

Justices of the Peace (county judges) managed elections until the 1902 state constitution was adopted. The constitution required the local circuit/corporation court to appoint a three-member Electoral Board to serve three year terms, with proportional partisan representation reflecting votes for the top two political parties in the most recent general election. No one in office, or working for the Federal government, could be appointed to the local Electoral Board.

Local Electoral Boards still oversee elections, but today there is also a state agency involved.

The five-member State Board of Elections oversees the Virginia Department of Elections (often written as ELECT). The two state organizations are responsible for supervising and coordinating local election administration, but each city and county has an three-member Electoral Board appointed by the chief judge of the local Circuit Court. The local boards have the power to design ballots and administer elections in each town, county and city. Local judges choose new Electoral Board members from a list of recommendations submitted by the local Republican and Democratic party committees.

There are 133 local Electoral Boards that oversees the voting process in 95 counties and 38 cities, so there is a total of 399 local Electoral Board members in Virginia. Each Electoral Board hires its own General Registrar, the person who is responsible for administering each election. Statewide, the 133 General Registrars hire roughly 10,000 election officers for Election Day.

Registrars and Electoral Boards notify the Town Council, City Council, or county Board of Supervisors when precinct boundaries need to be modified. Changes typically are needed when population growth results in a precinct exceeding 5,000 registered voters, when cities and towns adjust their boundaries, and after General Assembly and Congressional district boundaries are redistricted every decade.

In 2020, Virginia had 2,453 precincts. That had grown to 2,533 precincts in 2025. In that year, Chesterfield County's Magnolia Precinct had the most (7,414) registered voters. Craig County's Paint Bank precinct was the only one in the state with less than 100 registered voters; it had 83.

Election officers serve as a greeter at the election sites ("polls") to direct voters to the appropriate table in the building with a pollbook officer, pollbook officer to validate a voter is eligible and to mark that they received a ballot, ballot officer to account for every ballot (including those marked as "spoiled"), voting equipment and booth officer to provide assistance if requested in using the electronic voting technology and inserting the ballot into the optical scan tabulator, plus a chief officer and perhaps an assistant chief officer to ensure procedures are followed and provide guidance when needed.

Thousands more poll watchers (observers) are recruited by political parties to look for fraudulent or irregular behavior at the polls during voting and vote counting. Observers are authorized only to communicate with election officials; they have no decision-making authority at the poll. In theory, the extra eyes and ears of observers will increase election integrity and also increase public confidence that an election was conducted fairly.

Each political party is entitled to have three observers in the room on Election Day, from the opening of the electronic ballot boxes to the shipment of marked ballots and electronic voting machines to the local Electoral Board at the end of the day. In addition, observers may also stand guard next to outdoor ballot drop boxes prior to Election Day.

After President Trump proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen, there was a surge of interest in the electoral process and in behind-the-scenes procedures.

Educating political activists about the procedures, and allowing them to observe in person, does not prevent people from making claims about voter fraud. Though the Republican candidate for governor in 2021 did not endorse Trump's dishonest claims about the 2020 election, a Republican State Senator claimed before Election Day that the Democrats were planning to steal the race. She offered no evidence, but boldly stated:1

- ... they're stealing elections in Virginia... They're moving, in cyberland, they are switching inactive voters to active voters, all in the same week, it's undetectable.

President Trump's false claims that the 2020 election was fraudulent spurred public interest in the details of managing polling places and counting votes

Source: Tyler Merbler, Heads (January 6, 2021)

Terms of the registrar serving under a city/county Electoral Board are timed to end mid-way through the second year of a governor's term. That timing ensures the local Electoral Board has a majority of members from the governor's party.

Typically, registrars are considered to be non-partisan; most have been re-hired even if the political balance on the Electoral Boards across Virginia shifted after a new governor was elected.

However, the Electoral Board has the authority to fire the General Registrar before their term has expired. The Fairfax County Electoral Board fired its General Registrar in May, 2018, just two weeks before the primary election. The firing was triggered by the registrar's refusal to comply with board direction to process voter registration updates received from the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles.

The registrar was concerned that the printed version of the updates were not consistent with the information which voters had submitted electronically or at the Department of Motor Vehicles, and had added information beyond the address change request. He notified 5,000 voters who had moved to Fairfax County that that had to fill out paper registration forms before they would be registered to vote, in order to ensure the integrity of the information in the database. The Virginia Department of Elections contended that the data was accurate and the process used by registrars to print reports created the problem.

The Fairfax County Electoral Board vote was 3-0, so it was non-partisan. All Republican and Democratic members agreed to the termination.

In 2021, the Charlotte County registrar resigned abruptly after being accused of mismanagement by both Republican and Democratic leaders. The registrar apparently had failed to pay bills on time, and had not secured voting machines in the early voting period before the November election. The registrar had previously claimed the secretary of the county electoral board had threatened him, and even obtained a protective order from the local court. The abrupt resignation occurred during a court proceeding involving the protective order.

The Charlotte County Electoral Board certified the results of the 2021 General Election on November 2, but then questioned how the mail-in ballots had been managed by the registrar. In the end, the secretary of the Electoral Board notified the Virginia State Board of Elections that the certification of the results had been withdrawn, due to suspected fraudulent use of the mail-in ballots.

In 2024, the Inspector General of the City of Richmond reported that the registrar had violated procurement regulations and policies, and spent $500,000 in questionable ways. Officials in Richmond's city government had initially proposed that the State Board of Elections review allegations of waste, fraud and abuse. The state responded that the city had responsibility because state policies and state voting procedures had not been violated; it was the responsibility of the city to investigate the charges.

In 2019, the General Assembly had sought to make it harder for an Electoral Board to fire a registrar, but Governor Northam vetoed the bill. Registrars complained that they received pressure from Electoral Boards to support the political party in power, such as organizing registration drives at partisan rallies, and their jobs were threatened if they were too non-partisan.

The bill would have required a Circuit Court judge, rather than just two members of the three-person board, to fire a registrar. The Circuit Court judge appointed the Electoral Board members, but had no role in hiring or firing registrars.

Registrars felt at risk because they were not guaranteed the same protections as state employees. If fired for failure to be sufficiently partisan, the only appeal process was for registrars to hire their own lawyers at personal expense to contest the decision. The vetoed legislation would have provided publicly funded legal counsel.

In support of the bill, one registrar articulated the challenge of operating a non-partisan office overseen by three partisan Electoral Board members:2

- We're not a genie in a lamp. You don't rub the lamp and we do whatever the party in control wants us to do. We have to maintain the integrity of the registration system and our office.

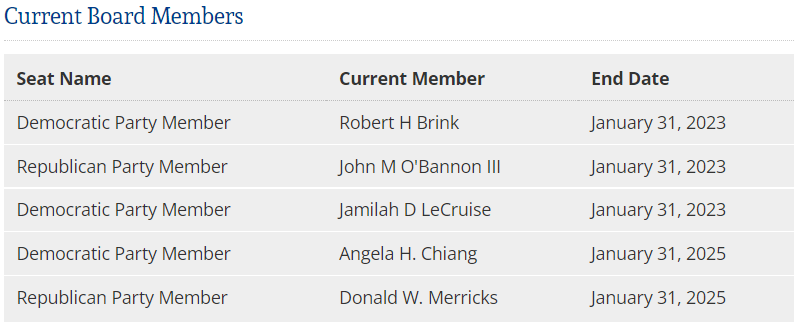

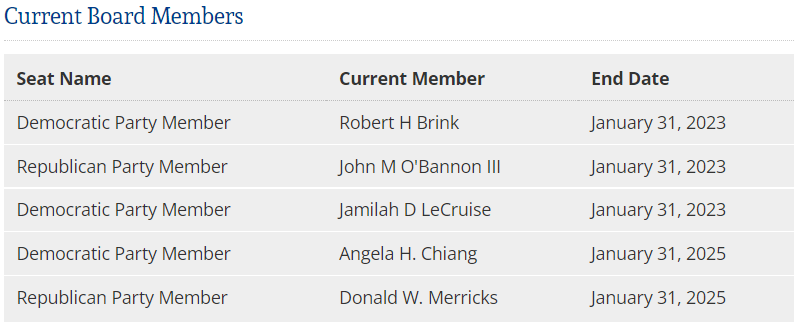

At the state level, the governor appoints the five members of the State Board of Elections, who serve four-year terms. The General Assembly must confirm the appointees. Three Board members must represent the political party of the Governor. However, when a Republican Governor replaced a Democratic Governor in 2022, no terms of the members of the State Board of Elections expired until 2023. For the first year of Governor Youngkin's term, the Democratic Party retained majority control of the State Board of Elections.

Youngkin did use his authority to appoint a new Commissioner of the Virginia Department of Elections. In the General Assembly, legislators debated a bill to eliminate the governor's authority to make that appointment and have the State Board of Elections choose the commissioner.

after being elected in 2021, Republican Governor Youngkin could not gain a majority of members of the State Board of Elections until 2023

Source: Secretary of the Commonwealth, State Board of Elections

The three members of each Electoral Board are appointed by local Circuit Court judges, using a list proposed by the local political parties. Each year, judges appoint one new member to serve a three-year term starting March 1. Electoral Board members are typically politically active, but may not be paid campaign workers, political party committee chairs, elected officials, or government employees. Even substitute teachers are disqualified from serving on an Electoral Board.

Electoral Board members can be replaced by the local Circuit Court judge before their term has expired. That process starts when someone requests the State Board of Elections to file a petition with the Circuit Court. If the State Board of Elections declines to act, then the removal process s blocked. If the State Board of Elections files a petition, then the Circuit Court judge must make a decision.

In 2024, the Registrar in Charles City County and two of the members of the Electoral Board requested that the State Board of Elections petition for removal of the third member. It was a bipartisan request from one Republican Party member and one Democratic Party member. They said the third member, a Republican, had threatened election integrity by allowing the chair of the local Republican Committee to write down the passwords being entered into voting machines during a Logic and Accuracy test.

The combative behavior of the Electoral Board member had disrupted operations of the local elections office, and the request was to appoint a different Republican to the Electoral Board. The behavior of the chair of the local Republican Committee caused the 4th Congressional District Republican Committee to disband the Charles City County Republican Committee, displacing the chair from her post. The bipartisan request by the Electoral Board to the State Board of Elections was a rare event, but reflected the inability of the local elections office to perform its duties.

A preliminary protective order issued by a judge prevented the combative Electoral Board member from participating in the canvass of votes after the June 20, 2024 primary. She was required to stay 100 feet away from another member, after an earlier shoving incident in the Charles City County elections office during pre-processing of absentee ballots led to an assault charge.3

In 2022, just before an election for City Council, the Republican and Independent candidates and the Roanoke City Republican Committee called for replacing a member of the city's Electoral Board. They sent an e-mail to the Registrar saying her membership "deeply harmed" the integrity of the election process, because she was married to the chair of the city's Democratic Party.

State law prohibited Electoral Board members from being elected officials, candidates for office or close family members of candidates, chairs of political parties, married to the Registrar, or part of the same family as another member of the Electoral Board. However, almost all Electoral Board members are active within their political party, which is how they get nominated. While the local chair of a political party can not serve on an Electoral Board, there is no prohibition on members of their family serving.

One clue to the political intent behind the call for replacing a Roanoke City Electoral Board member in 2022, and the intent to sow doubt about the election integrity process, was that the message was sent to the Registrar. It was not sent to the Circuit Court judges with responsibility for appointing and replacing the three Electoral Board members. The term of the board member married to the Democratic Party chair was expiring, and the governor's office had shifted from a Democrat to a Republican in the 2021 election, so the Circuit Court judges were obliged to replace her with a Republican appointee within two months anyway.

The Registrar's response was simple - he had no authority regarding who served on the Electoral Board. The Circuit Court judges were in charge, and:4

- You can speak with them about this.

Two members of the local Electoral Board must belong to the same political party as the governor, while one represents the other party. At the end of each governor's term, there will be two members on all Electoral Boards who represent his/her party, and one of those terms will be expiring.

For example, at the end of a Democratic governor's term, all Electoral Boards will have two Democratic members and one Republican member. When Republican Glenn Youngkin was elected in 2021 to replace Democrat Ralph Northam, the chief judge of the Circuit Court had to appoint a Republican in 2022 to replace a Democratic member whose term was expiring. Those appointments shifted the 2-1 political balance on all local Electoral Boards for the next four years.

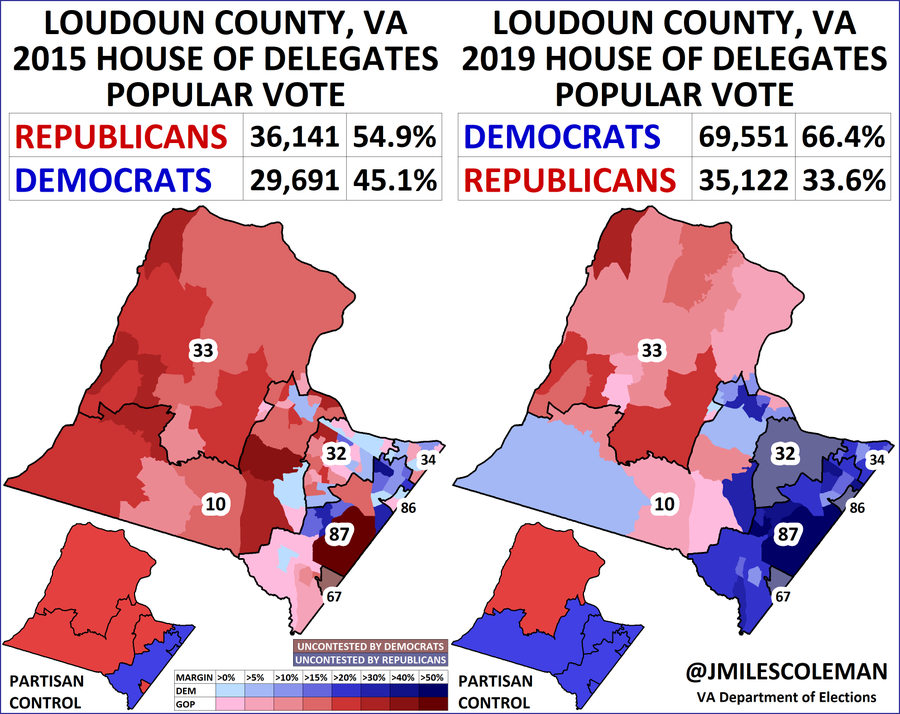

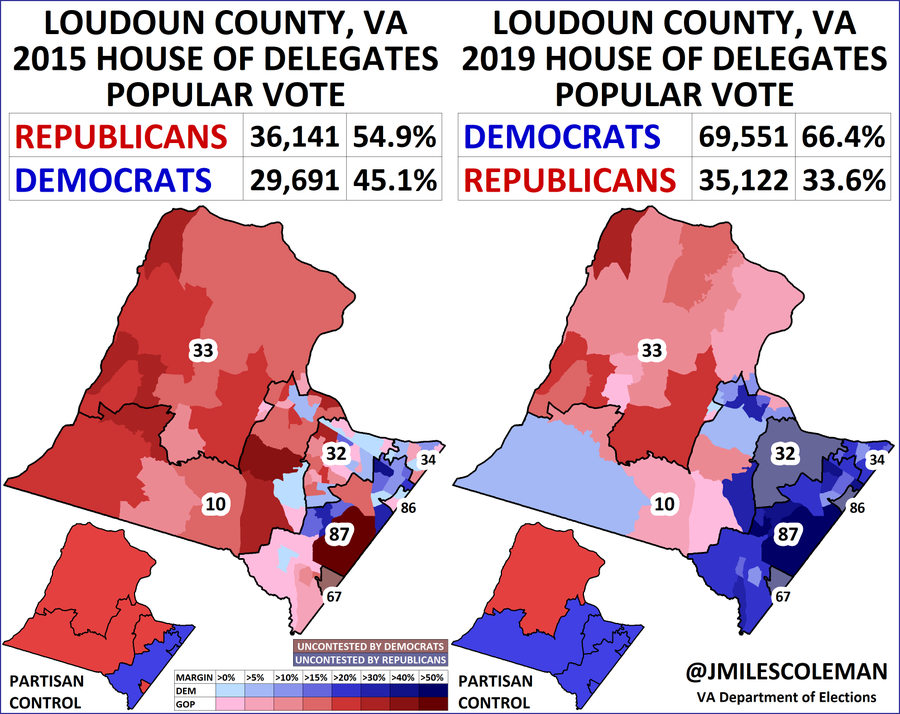

A shift in membership on an Electoral Board can be reflected in decisions that create partisan advantages in elections. In 2023, as soon as Republicans gained a majority on the Loudoun County Electoral Board, it ended Sunday voting. In a 2-1 vote later, it eliminated weekday in-person early voting in the Democratic-leaning eastern part of the county.

The Republican members noted that when Democrats had a majority previously on the Electoral Board, there was no weekday in-person early voting in western Loudoun - the Republican-leaning portion of Loudoun County.

Loudoun County Electoral Board decisions limited voting opportunities in the Democratic, then Republican regions of the county

Source: J. Miles Coleman, Twitter post (November 10, 2019)

The governor had no official authority to replace members of local Electoral Boards, but he has influence. In 2022, news reports revealed that the Republican in charge of the City of Hampton Electoral Board had posted racist comments on Facebook. The local Republican Party called for the Electoral Board member to resign, and after he declined the party asked the Circuit Court judge to replace him. After Governor Youngkin, a fellow Republican, echoed the call to resign, the chair submitted his resignation and the chief judge of the Hampton Circuit Court formally removed him from the Hampton Electoral Board.

In the 1990's the primary responsibility for each Electoral Board and General Registrar was record-keeping. Voting machine technology today has added much greater complexity.

The state reimburses cities and counties for the salaries of the general registrar, using a pay scale based on the population of the jurisdiction. There are six population brackets, and registrars in areas with over 200,000 people get the highest salaries:5

- up to 25,000 people

- 25,001 - 50,000 people

- 50,001 - 100,000 people

- 100,001 - 150,000 people

- 150,001 - 200,000 people

- 200,001 or more people

Registrars hire some permanent staff, and may rely upon just part-time staff in areas with smaller populations. All registrars rely heavily upon temporary poll workers ("Officers of Election") who staff precincts on election days. Temporary poll workers set up machines before polls open at 6:00am. They check the names of everyone who appears to vote in the polling book, which lists all registered voters eligible to vote in that precinct.

County supervisors and city councils gave the final authority to define the boundaries of voting precincts, and rely upon input from local registrars. State law requires that the polling place for each precinct, the building where voters go to cast their votes, must be within the county or city and within a mile of the precinct boundaries. Precinct boundaries must be drawn so there are no more than 5,000 registered voters. The minimum number of voters in a city precinct is 500, while the minimum for a precinct in a county is 100 registered voters.6

"Split precincts" include more than one local/state/Federal voting district. In such precincts, election officials do not give the same ballot to every voter. Instead, election officials must check the poll book to determine the election districts in which each voter is authorized to vote based on the location of their official residence, then provide a ballot with the correct set of candidates.

Split districts add to the workload of the poll workers and create the potential that people will cast their votes in the wrong races. The Louisa County voter registrar commented before the 2019 general election:7

- We have a precinct that has 3,000 voters in it and five of those voters are in a different district and have a different ballot so we have to make sure that everyone gets the right ballot.

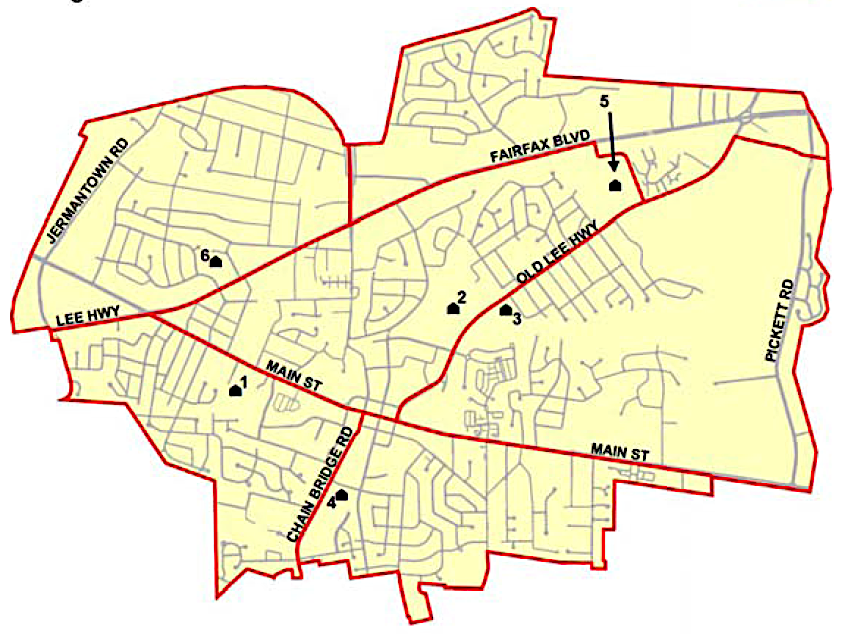

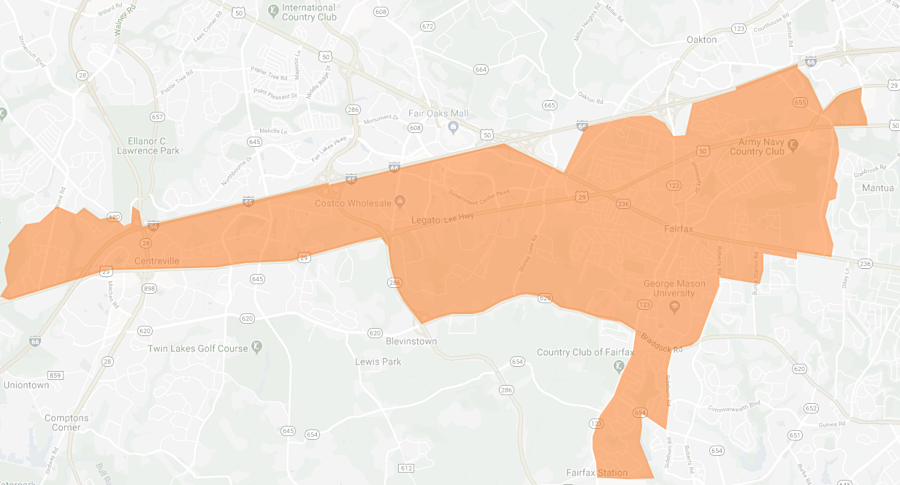

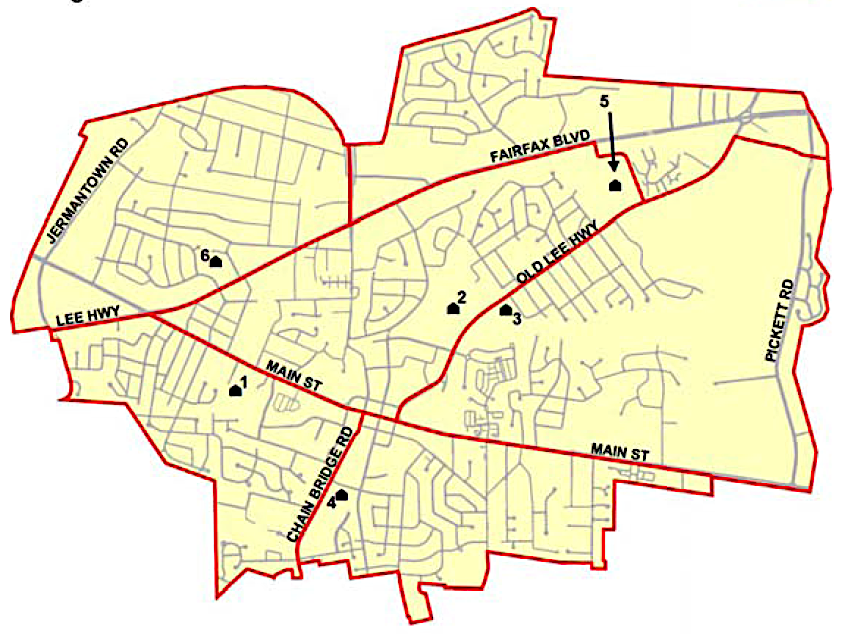

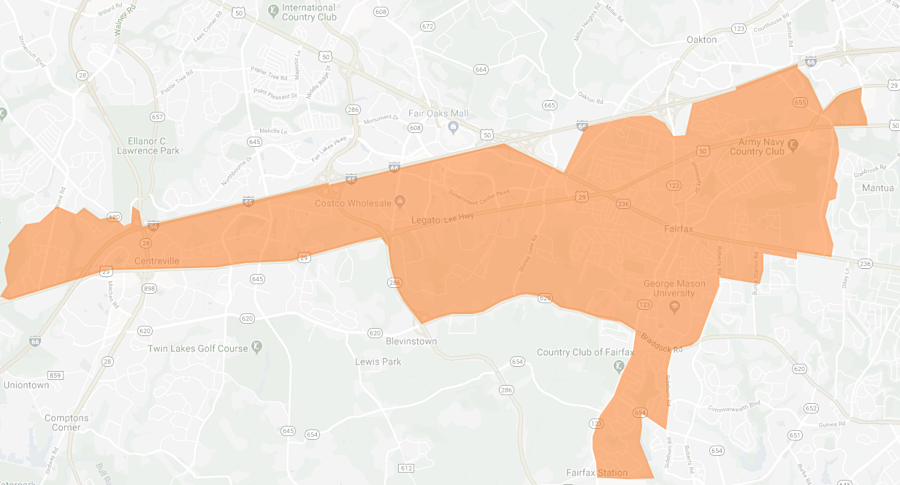

If the voter is in the correct precinct, poll workers hand them the ballot which corresponds to their local/state/Federal voting districts. For example, ballots distributed to voters in all six precincts within the City of Fairfax will include spaces to vote for members of City Council, but not for the Board of Supervisors in Fairfax County.

in 2019, the City of Fairfax registrar distributed ballots to six precincts

Source: City of Fairfax, Voting Precincts

After the 2010 redistricting, the state Delegate for the 37th District was elected by voters in both the City of Fairfax and in a part of Fairfax County. The registrar in Fairfax County ensured that voters in 10 of Fairfax County's precincts (including #134, "University Precinct" at Merten Hall on George Mason University's Fairfax campus) received ballots which included the race for the 37th House of Delegates seat. The registrar in the City of Fairfax distributed ballots within the city that also included the race for the 37th House of Delegates seat.

registrars distributed ballots so voters in all six City of Fairfax precincts, plus 10 precincts in Fairfax County, could vote in elections for the 37th District of the House of Delegates

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), House of Delegates District 37

The 2020 General Assembly anticipated how precincts would be affected when new voting district boundaries were drawn after the decennial census. The maximum size of a precinct was set at 5,000 registered voters.

A new law required that, after 2021 redistricting, precincts had to be wholly contained within a single congressional district, Senate district, House of Delegates district, and local election district (for city wards or county magisterial districts). Split precincts could be authorized via a waiver from the State Board of Elections, if the alternative would require establishing a precinct with less than the minimum number of voters. The law defined he minimum:8

- ...each precinct in a county shall have no fewer than 100 registered voters and each precinct in a city shall have no fewer than 500 registered voters.

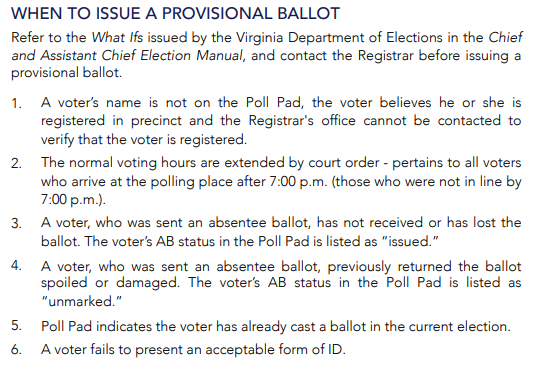

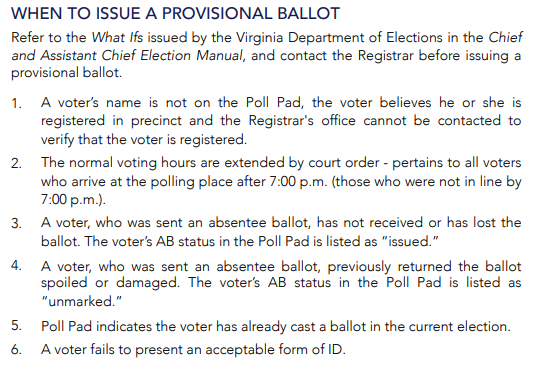

If a person appears in person to vote on election day but lacks adequate identification, poll workers require that voter to mark a provisional ballot. Other circumstances, including extension of voting times past 7:00pm, also trigger a need for provisional ballots. Provisional ballots are counted only after determining the day after the vote that the person was eligible.

poll workers issue provisional ballots, allowing people to submit a vote, in specific circumstances

Source: Fairfax County, Election Officer Manual (April 2016, p.66)

All voters mark their ballot in secret. In most cases, they now run the marked ballot through an electronic scanning machine. At the precincts, election officials should never see how an individual voted. If a disabled voter needs assistance, they may use their own assistant to mark their ballot.

Election officials do see the total votes recorded by each machine, after polls close at 7:00pm and the last person then standing in line has voted. Those totals are reported to the General Registrar, who then forwards the uncertified totals to the Virginia Department of Elections. "Official" totals are submitted as much as several weeks later, after ensuring all inconsistencies have been addressed and provisional votes counted.

The temporary staff typically works the entire election day, from setting up the machines in the precinct before opening the doors to reporting the final vote. If there are discrepancies between voting machine totals and the number of people recorded as voting, then the workers may stay several extra hours before reporting the vote tally for that precinct.

Recruiting election officials is a challenge for General Registrars. Fairfax County advises that a poll workers will be at the precinct from 5:00am-9:00pm, for which they were paid $175 in 2018. In that election, workers were allowed to sign up for just a half-day split shift. There was no extra "overtime" pay if the count required extra time to resolve discrepancies on election night.

For the 2020 election, the Fairfax County Electoral Board planned to hire 3,500 elections officers and to provide 13 in-person absentee voting locations for those who voted before election day. Because turnout was projected to be between 85-90% of registered voters, a member of that Electoral Board said:9

- ...we're ordering a lot of ballots.

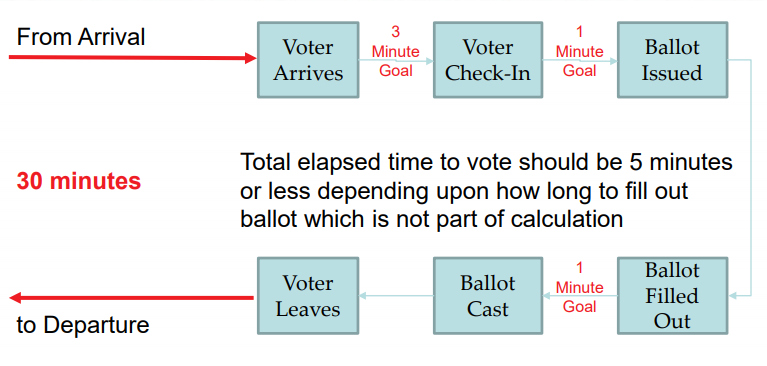

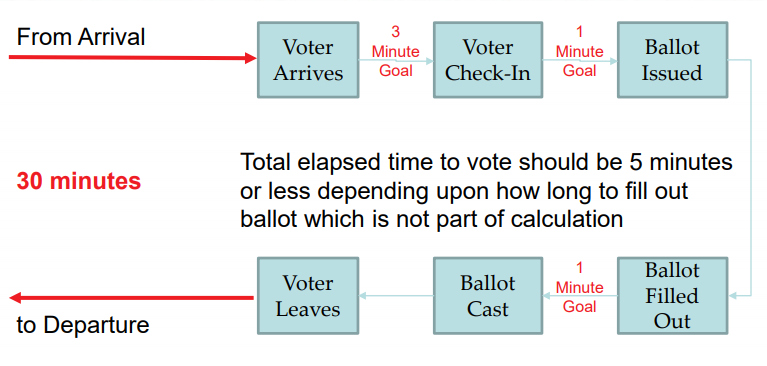

Election day planning by registrars is equivalent to how pizza stores plan for Superbowl Sunday. Pizza store owners project the number of customers for that day, order a surge of supplies (dough and toppings), hire temporary staff, and then wait for customers to appear. Registrars estimate how many voters will show up at the polls for each election. Based on the estimates, they order printed ballots, recruit and train temporary staff, and assign voting machines to each precinct. The goal is to have voters come and go within 30 minutes, with most of that time waiting in line. Ideally, actual voting should require just 5 minutes.

the ideal for General Registrars is that all voters complete the entire process, including waiting in line, within 30 minutes

Source: Prince William County, Election Service Levels (March 13, 2018)

For the November, 2012 election, Prince William County officials miscalculated how many people would register and vote. The Electoral Board and General Registrar did not allocate enough machines or staff to some precincts, creating long lines.

In the River Oaks precinct, the last voter finally cast a ballot at 10:46pm, nearly four hours after the polls officially closed. The delays triggered accusations of intentional voter suppression in precincts expected to vote for Democratic candidates.

In subsequent elections, the county added more precincts to accommodate more voters. The Electoral Board and General Registrar also used registration statistics examined closer to the date of the election, in order to allocate staff and equipment to match anticipated demand more closely.

A bi-partisan task force in Prince William County concluded, after reviewing the long lines in the 2012 election, that voter suppression was not intentional. Delays were caused by outdated voting machines, the need to match addresses to provide correct ballots after the 2011 Census triggered redistricting, and requests for assistance by voters with physical limitations as required under the Help America Vote Act.

In particular, Prince William County had drawn boundaries that put too many voters into a single precinct. The number of voters overloaded the ability of poll workers to provide ballots in large precincts, and made it difficult for voters to get into polling places:10

- Large precinct size causes many problems to cascade from the mere crush of voters at the polls. For example, it is quite apparent that a large precinct in a high-turnout election will cause parking problems at polling places, particularly if they are located in elementary schools or middle schools...

voters who do not cast ballots before election day may experience long lines at polling places

Source: Virginia Board of Elections, Prince William County, VA: Analysis of Voting Data from November, 2012

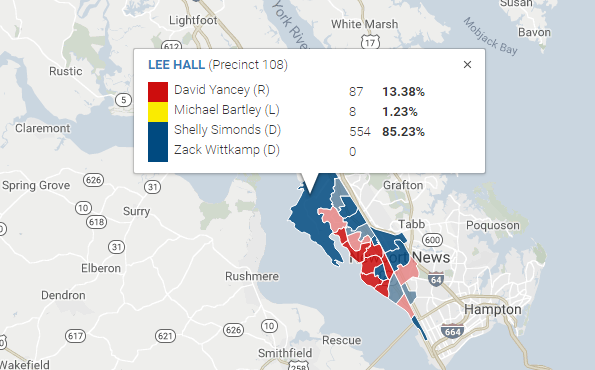

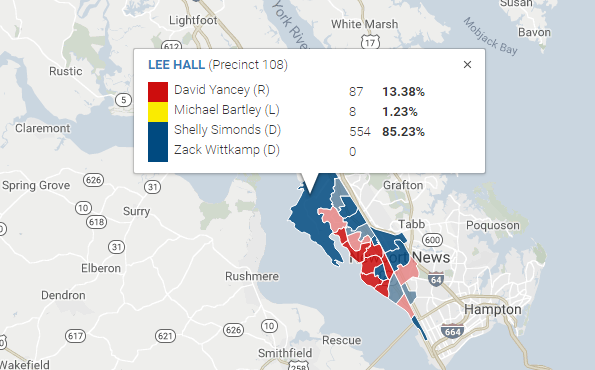

Local registrars are responsible for ensuring voters are assigned to the correct precinct. Errors in making such assignments may have affected the November 2017 race in the 94th District for the House of Delegates.

The initial vote total determined the Republican candidate won by 10 votes. In the recount, managed by a Recount Court with three Circuit Court judges, the ballots were examined again and the Democratic candidate won the race by one vote. However, before the Recount Court met to certify the election an election official changed his mind and decided to count a ballot that had initially been discarded. The Recount Court judges accepted that proposal. The final vote ended in a tie, with each candidate getting 11,608 votes after the recount was finished.

To resolve the tie vote, the Virginia Board of Elections then picked the winner "by lot," which was done through drawing names from a bowl. The random result gave the seat to the Republican candidate. The impact was felt statewide, because the decision gave the Republican Party a 51-49 partisan edge in the House of Delegates for the next two years. The Electoral Board was not involved in the recount process, but its assignment of voters to different precincts ended up being part of the controversy.

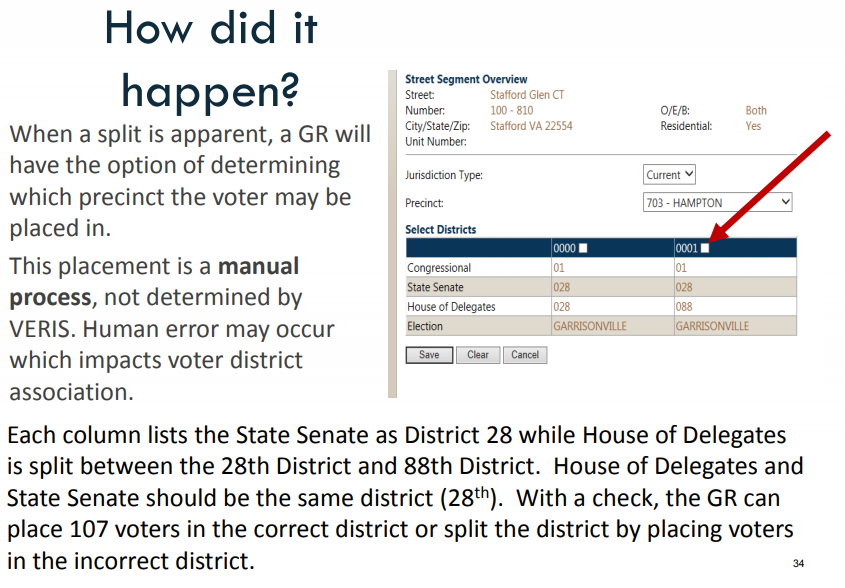

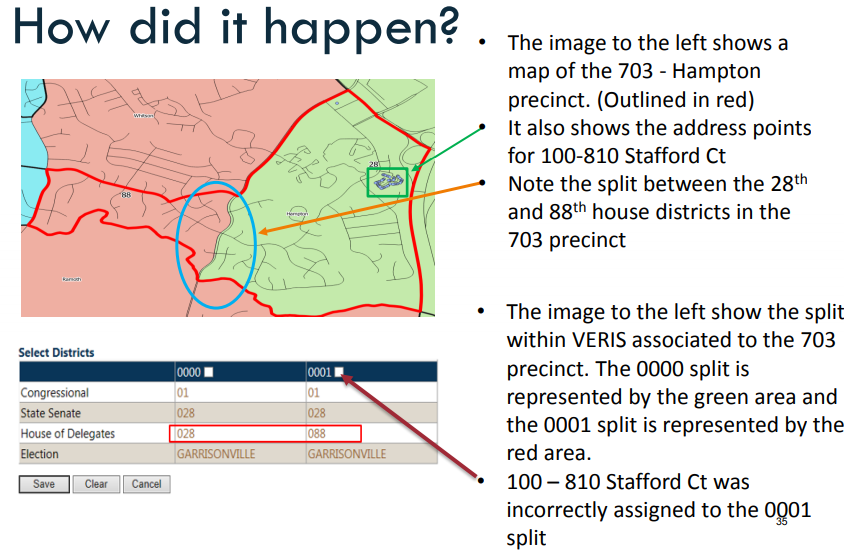

In 2018, the Virginia Department of Elections began a "misassigned voter" project using more-accurate data and Geographic Information Systems technology not normally available to local Electoral Boards. The objective was to ensure a more-accurate alignment between where people lived and the precincts where they voted.

Six months after the 2017 election, the state agency revealed that voters in the 94th District had been assigned to the wrong voting district by the Newport News registrar. 26 residents of seven new apartment buildings in the Lee Hall precinct of the 94th District were given ballots to cast votes for candidates in the 93rd District.

The local registrar had incorrectly assumed the Zip Codes of those buildings placed them in the 93rd district. Since 85% of the Lee Hall precinct voted for the Democratic candidate, there was a significant chance that the registrar's mistake in assigning the 26 people who voted to the wrong district prevented the Democratic candidate from winning in the 94th District. The tie vote and then "by lot" decision on the winner of that single seat flipped the partisan control of the House of Delegates from Democratic to Republican.

errors by the Newport News registrar in assigning voters in the Lee Hall precinct may have altered results in the 2017 election for the 94th District

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, House of Delegates District 94 (2017)

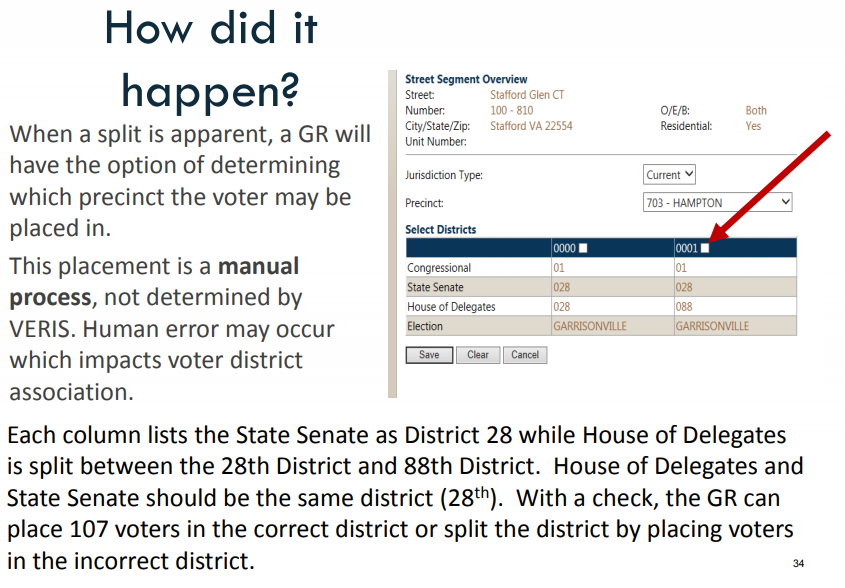

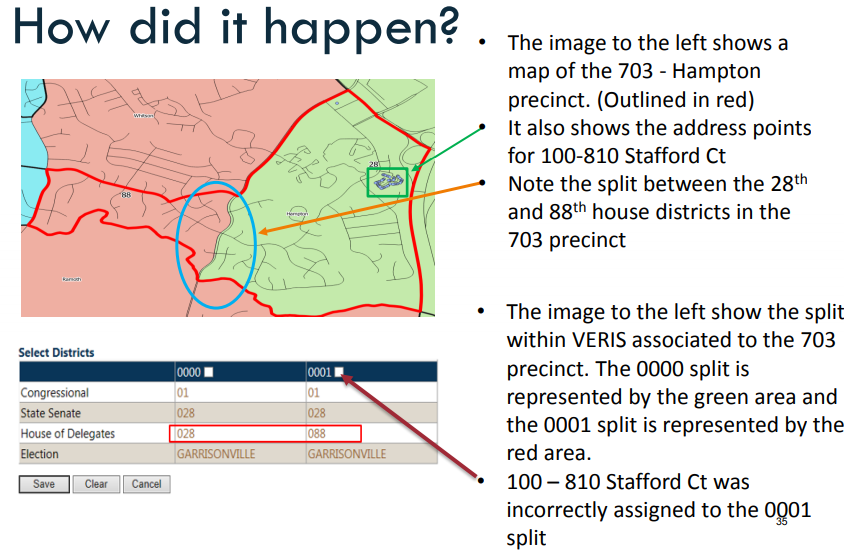

The Virginia Department of Elections discovered the mistake by using maps based on Geographic Information System (GIS) technology rather than mailing addresses. Similar errors were identified in other districts as well; by 2018, the state agency had:11

- ...identified 9,140 voters at 7,565 addresses (out of approximately 5.5 million registered voters) who appear to have been assigned to the wrong congressional or state legislative districts.

Errors are particularly likely where precincts are "split" between voting districts, and poll officials need to provide different ballots to voters within the same precinct.

Local registrars did not have access to the state agency's technology and the Virginia Election and Registration Information System ("VERIS"). In Newport News, the local Electoral Board had not provided the funds for the registrar to build a local mapping system, and the city had not provided access to its computerized mapping system.

The Virginia Department of Elections can advise local registrars of potential errors in voter assignments, but only the local registrars have the authority to assign voters to specific precincts. The state agency concluded that local registrars relied at times upon incorrect sources of data, and:12

- ...may incorrectly determine a voter belongs in an election district/precinct because the voter pays taxes or receives utility services from a specific locality.

- Taxes, utility services, etc. have no influence on election districts or where a person votes.

the Virginia Department of Elections documented how a local General Registrar (GR) could mistakenly assign voters in a split precinct to the wrong district

Source: Virginia Board of Elections, Agenda, June 19, 2018

According to the Code of Virginia, a registrar may need to know the location of a bedroom within a house in order to assign the resident to the correct voting precinct:13

- A person whose residence is divided by a jurisdictional boundary line or election district boundary line shall be deemed to reside in the location of his bedroom or usual sleeping area

Candidates for a seat in the General Assembly must live within the district that they intend to represent. The 2021 redistricting by the Virginia Supreme Court was unique, because the special masters appointed by the court to draw new maps ignored the residence of incumbent legislators; the redistricting maps were not gerrymandered to protect incumbents.

For a change, many incumbents in the House of Delegates and State Senate ended up in districts where they would have to run against another incumbent. A few members of the state legislature chose to compete in contested June primaries or the November general election. Others chose to retire or to run for a different office, and some moved their official residence to another district.

A candidate for House of Delegates District 53 leased a garage studio apartment and registered to vote at that address in order to establish residency. That space was not zoned for a residence and lacked a bathroom, and the property owner was cited for a zoning violation. Supporters of an opposing candidate asked the Electoral Board in Bedford County to disqualify the candidate because he was not a legitimate resident dwelling for living purposes.

The registrar chose to retain the candidate on the voting rolls. He occupied a non-traditional residence, one that was inconsistent with local zoning, but where he actually slept at night determined his official domicile for voting registration and eligibility for office.

In August, 2018, the Virginia Board of Elections provided the Pittsylvania County registrar a list of 300 addresses that could have been assigned to the wrong voting precinct. Several weeks before the November 6 election, 31 voters were sent letters telling them they lived in Halifax County and should vote there in the future, rather than at their traditional Pittsylvania County precinct.

On election day, three of those 31 people still showed up at their normal polling place. The registrar had updated the polling books, and the three were redirected to the appropriate polling place in Halifax.14

Another review by the Virginia Department of Elections in 2018 determined that residents of 23 properties split by the Essex County-Caroline County border were voting in the wrong county. They had been paying taxes to Essex County, going to schools in Essex County, and voting in Essex County, but the state agency determined that they lived in bedrooms located in Caroline County.

The solution was to ask the General Assembly to adjust the county boundary in 2019 and make the people official residents of Essex County. As the Caroline County Administrator described the situation:15

- All these people went to school in Essex, they've voted in Essex. They don't want to be Caroline citizens - they always thought they were Essex citizens.

The State Board of Elections has the authority to certify or decertify voting machines used to record votes in elections, and local Electoral Boards must comply. In 2017, in response to accusations that Russia had explored ways to affect results of elections, the state agency decertified the touch screen machines used in 23 jurisdictions within the state and required use of use paper ballots and electronic scanners. Recounts would be more reliable with a paper trail.16

Election results are not final until all ballots are counted. The initial results announced on election night and into the next morning will indicate how many precincts have been counted. Absentee ballots that are postmarked by the time the polls close on election day and delivered within three more days will be counted.

Sometimes, provisional ballots are the last to be tabulated. Such ballots are issued to voters who claim they are both registered and eligible to vote in the election, but may not have brought adequate identification to the polls.

Voters who come to the polls may also cast a provisional ballot if they had requested an absentee ballot, but did not bring it physically to the poll to surrender so election officials could be certain they did not vote twice. A pollbook may mistakenly - or correctly - indicate a person has already voted. Allowing the voter to fill out a provisional ballot ensures the right to vote in not blocked, but allows election officials to correct any mistakes with pollbook records.17

A post-Election Day canvass is performed by each local Electoral Board to ensure all the votes have been counted and reported correctly. That review is a key step before each board certifies results as "official." It is common for the numbers of the unofficial results to be revised on the night of the election and to change slightly before certification of an election, but uncommon for presumed results to change after all precincts have submitted unofficial results.

The canvass must be completed within 10 days of the election. The number of voters recorded in the poll book of each precinct is matched to the total number of votes in the precinct. If there is any discrepancy, the scanner tapes can be used to view images of each ballot and correct the totals. Provisional votes and late-arriving absentee ballots are also counted in the canvass. After all the ballots are counted and any errors are corrected, the Electoral Board certifies the results. Certification of non-local races, such as the 11 US House of Representatives races, are certified by the State Board of Elections in December after it ensure local reports are accurate.

In the 2021 General Election, the results announced on Tuesday night in Prince William County reflected a significant error by an election official. One candidate was credited with 16,000 extra votes after early, in-person votes cast at once polling place were counted twice, while 1,200 early, in-person votes cast at another polling place were not reported. The inaccurate numbers were submitted to the Virginia Department of Elections website, but corrected within hours. The mistake did not affect the results of two affected elections, but the winners had lower margins of victory.

That same election day, mistakes in Montgomery County did alter the winner of one of three seats for Christiansburg Town Council. Election officials correctly shut down the voting machines and printed tapes from each summarizing the results. Mistakes were made in the central absentee precinct when recording the numbers for the report submitted to the Virginia Department of Elections. The post-election canvass caught the mistakes on Thursday night. On Friday, one candidate who thought he had won election discovered he had come in fifth, while another candidate coming to terms with his defeat realized he was in fact a winner.

The incumbent in House of Delegates District 91 thought she had lost and conceded the race in 2021. On Friday night after the election, officials discovered that figures had been transposed when tabulating results and she withdrew the concession. The canvass revealed that the winner in the race had less than 0.5 percentage points more votes, so the incumbent requested a state-funded recount after announcing:18

- In light of this news and the significant shift we have seen in the count since Tuesday night, we think it wise to do our due diligence to make sure every vote is fairly and accurately counted. We will allow the process the full time and effort it takes to ensure accuracy.

In addition to the 91st District race, in 2021 the House of Delegates race in the 85th District had a winning margin of less than 0.5% - close enough to justify a state-funded recount. In both cases, the recount reaffirmed the initial outcome. In the 91st District, the recount reduced the winning margin out of 27,836 votes from 94 to 64, but the Republican candidate remained the winner. The winning margin in the 85th District, out of 28,442 total votes, dropped from 127 to 115 votes in the recount.

The canvass process after Election Day corrects almost all errors created during unofficial reporting on election night, when polling place officials may have tired from been working for 14-18 hours. Recounts do have the potential to overturn close votes, as demonstrated in 2017 when the 94th District result for the House of Delegates race was switched after the recount ended with a tie, but changing the winner is a very rare experience.

The primary value of the recount process overseen by a panel of three Circuit Court judges is to increase confidence on the counting done by local election officials. In 2021, the losing candidate in the 91st District included in her concession speech:19

- Recounts offer the opportunity to make sure each vote has been counted accurately and instill confidence when margins are razor-thin.

The State Board of Elections can not remove members of local Electoral Boards and Registrars if they fail to follow state laws and procedures. Only Circuit Court judges have that authority.

After the November, 2015 election, the chair of the Electoral Board in Prince William County brought four members of his political party into the county's Office of Elections and conducted an unauthorized investigation.

He administered the oath taken by election officials, claiming that deputized and authorized the four members of his team to examine records in the office. Their intent was to document that the online process allowing people to request absentee ballots had resulted in voter fraud. After comparing signatures on envelopes returning absentee ballots with signatures on file in the Office of Elections, the investigators claimed that 6% were questionable.

The elections office staff objected to the intrusion into voter privacy, which included review of records with birthdates and Social Security numbers. The chair had picked a time when he knew the Registrar would be on vacation.

A month earlier, the Electoral Board in a 2-1 vote had rejected the chair's request to conduct signature verification for ballots that had been requested online, after being told by the Virginia Department of Elections that such a process would violate state and Federal law.

The public uproar regarding the irregular review of official records spawned an investigation by the Commonwealth's Attorney, though ultimately no legal action was taken. In January, 2016, the State Board of Elections voted 2-1 to request that the local Circuit Court remove the chair from the Prince William County Electoral Board because of his inappropriate investigation. Claims of voter fraud were a partisan issue at the time, and the 2-1 vote to remove the Electoral Board member split along partisan lines.

The head of the state board described removal of a local Electoral Board member as the "nuclear option" for enforcement of state law, noting:20

- I take no joy in that... But this seems about as egregious as I've ever seen.

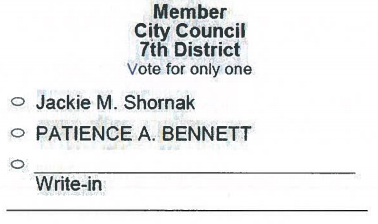

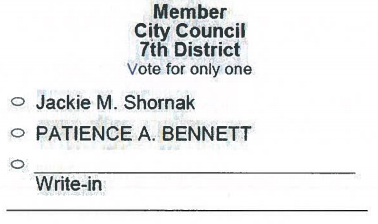

In 2018, the State Board of Elections voted 3-0 to request removal of two of the three members of the Electoral Board in the City of Hopewell, based on malfeasance in office. The two, both members of the Democratic Party, had authorized a ballot that printed the names of some candidates in upper-case block letters, highlighting them unfairly compared to other candidates on the ballot. The two also voted in a meeting closed to the public to hire a new General Registrar, which was a violation of the state Freedom of Information Act.

However, the State Board of Elections does not have the authority to remove members of local Electoral Boards. They are appointed by local Circuit Court judges, and can only be removed by those judges. To the Electoral Board members replaced, the State Board of Elections had to petition the local Circuit Court. The Virginia Attorney General's office represented the State Board of Elections in the process. The two Electoral Board officials had to make their own arrangements for legal services.

The judge suspended the two officials but did not remove them immediately. Instead, he agreed to their request for a jury trial. The judge also appointed temporary replacements to the Hopewell Electoral Board to oversee the upcoming election, which was less than three weeks away. At the end of February, 2019, a jury found the two members had been negligent in their duties and removed them.

At that point, the temporary appointees replaced the two people who were removed from the Hopewell Electoral Board. Soon thereafter, in a unanimous vote all three members fired the General Registrar. Firing the Registrar who had been hired by the previous Electoral Board members was possible, but had to be done before July 1, 2019. At that time, a new state law was supposed to go into effect that allowed only a Circuit Court judge to remove a Registrar, giving those officials the same job protection as given to the three members of the Electoral Board. Governor Northam later vetoed the bill, leaving Electoral Boards with the authority to fire as well as to hire their General Registrars. A Hopewell Circuit Court judge later upheld the legality of the Electoral Board's action.21

In fallout from the controversy, the mayor and three incumbents were defeated in the November, 2018 election. Four Hopewell City Council seats were on the ballot. Only one incumbent was re-elected, and she had no opponent.22

in 2018, Hopewell election officials proposed a ballot highlighting some candidates unfairly with capital letters

Source: Virginia State Board of Elections, Agenda (September 20, 2018)

Registrars have authority to register voters, but are not empowered to automatically delete a voter's registration if they move to another district within the state. The General Assembly has created a process for removing a person from the voting rolls.

In Richmond, three residents asked the local registrar to take even more assertive action. They requested that the registrar remove a member of City Council, after the Councilman for the 5th District moved to a new house located in the 1st District. The three petitioners included the former chair of the Virginia Board of Elections, the former 5th District Councilman, and a former assistant city attorney, but the registrar refused to claim any authority to remove a sitting member of City Council because he had moved.23

The authority of the local Registrar for Prince William County to appoint chiefs and assistant chiefs in precincts was altered by a judge less than a week before the November 8, 2022 election. The deadline for political parties to nominate individuals to serve as election officials was "at least 10 days before Feb. 1 each year." In 2022, the Republican Party filed no nominations by the deadline, and had not submitted names for the last 20 years.

The Registrar then appointed 1,800 election officials to serve at various precincts. When 600 declined the appointment, in September 2022 he made additional appointments to fill all the slots. The Registrar appointed Republican, Democratic, and non-partisan officials for each precinct in the county. For precinct chiefs and assistant chiefs, he recruited from both parties and appointed 399 Democrats and 402 Republicans.

On October 18, the Republican Party demanded that the registrar appoint more Republican officials in about 30 precincts, claiming too many of the "Republican" officials had previously voted in some Democratic primaries. A day later, the party filed a lawsuit. The Registrar, frustrated by the last-minute partisan maneuvering that challenged the integrity of the voting process and his professional decision making, announced he would resign after the election.

The judge ruled that the obligation to appoint people nominated by a political party was more significant than the experience level of appointees, and that the Republican nominees needed to be assigned to the 30 precincts. In response to the appointment of inexperienced officials, a Democratic member of the Prince William Electoral Board exclaimed:24

- It's outrageous that the Republican committee did next to nothing to recruit new officers... If there are problems on Election Day, it will be the result of this.

Registrars are hired for a four year term. The terms expire 18 months after a new governor starts their term. Because the three-member Electoral Boards are composed of two members of the governor's political party, a new Electoral Board may choose to replace a registrar even though managing elections is supposed to be done in a non-partisan manner.

After President Trump claimed voter fraud cost him the 2020 election, local registrars in Virginia faced accusations from Republican election conspiracy theorists that they were failing to run fair and honest elections. In 2023, after Republican Glenn Youngkin had won the election for governor in 2021, Electoral Boards switched from having a 2-1 Democratic majority to having a 2-1 Republican majority.

In Buckingham County, the new Electoral Board accused the registrar of treason and announced that she would not be re-appointed. She and all of her employees quit, declaring that the false accusations were too stressful. The Democratic member on the Board of Elections also resigned. Until the Electoral Board hired a new registrar, the two remaining Republicans were responsible for running the local elections.

A previous Democratic member of the Buckingham County Electoral Board predicted that half of the experienced poll workers serving at different precincts on Election Day would also quit, and commented:25

- The next [registrar] will have zero experience. The board won't have any experience. I would say at least half of the officers of elections are going to quit... Who's going to work the election?

The last member remaining on the Buckingham County Electoral Board, a Republican, hired an interim registrar. The new hire was an outspoken advocate of the claim that local elections had been fraudulent.

A month later in May, 2023, when a Democratic member was also serving on the board, the two members fired that interim registrar. That firing left the deputy registrar responsible for managing the general election in November. Fortunately for the registrar's office during the chaotic turnover, there were no state-run primaries to manage in Buckingham County on June 20 for State Senate District 10, House of Delegates District 56, or US Representative District 5 seats or for local offices.

The fired registrar had been combative with residents and local officials during his short time in the office. He tried to charge a Buckingham County supervisor an illegal $200 "convenience fee" for fulfilling a Freedom of Information Act request. In a rude response to the request from Supervisor Jordan Miles, the new registrar said:26

- So, Mr. Miles, what is the meaning of your games and what pray tell is your desired outcome? To see me fail? To bury me in paperwork that takes up my time? And you, sir, are trying to get out of paying my fee for my time?... I suggest that you get a part-time job at WalMart, then, Mr. Miles, so that you can pay my fees.

To fill out the third seat on the Electoral Board, the chair of the local committee of the Republican Party had to submit three nominees to the local Circuit Court. Two of the three nominees were the just-fired registrar and his wife. By that time, the former registrar was labeling Democrats as "the EIE network - Experts. In. Evil.

The letter with the three nominations included:27

- As the chair of the Republican party, I believe all three nominees will serve the citizens of Buckingham with dignity, fairness and respect...

In Lynchburg, the Electoral Board switched to a 2-1 Republican majority in 2023 as the result of the elction of a Republican Glenn Youngkin as Governor in 2021. One of the new members had circulated claims that the 2020 presidential election was stolen by Joe Biden. The Electoral Board then replaced the city's Registrar and deputy registrars.

In response the former Registrar sued, claiming the dismissal was purely partisan and violated her First Amendment right to free political association. Her job evaluations for her five years in that job had all been positive. Lawyers anticipated the case could end up in the US Supreme Court as a test case on the ability of government agencies to hire/fire based on partisan bias.28

In 2025-2026, the Electoral Board in Fairfax County was especially busy. It had to manage a series of special elections in addition to the annual primary and general elections.

In 2025, the member of Congress representing most of Fairfax County died. Voters chose a sitting member of the Boad of Supervisors to replace that member in a special election, triggering a second special election in the Braddock District to fill the now-vacant seat on the Board of Supervisors.

The person who was elected to fill the Board of Supervisors seat had been on the School Board, so a special countywide election was required in 2026 to fill the School Board seat. In addition, the new Virginia governor chose three members of the General Assembly representing portions of Fairfax County to serve in her administration. Three special elections were held in January-February to replace them, in time for the new members to represent those districts in at least a portion of the 2026 General Assembly regular session.

Estimating turnout for special elections is challenging. The Electoral Board prints ballots in advance, trying to avoid wasting money by overprinting while ensuring there will be enough ballots at each precinct to match the number of voters who appear in person on election day. The Electoral Board relied upon a printer that could produce 10,000 ballots an hour, in case demand exceeded supply.

Reflecting on the unusually busy schedule for the Fairfax County Electoral Board, the registrar joked one day:29

- ...it's not a Tuesday, so we don't have an election today, but we will have many more.

Links

- Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC)

- National Conference of State Legislatures

- Prince William County

- Virginia State Board of Elections

References

1. 1902 Virginia Constitution," Article II, Section 31, Library f Virginia, http://rosetta.virginiamemory.com:1801/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2924540&_ga=2.24622652.703429008.1706122438-246460519.1629906728; "Officer of Election Basics," Virginia Department of Elections, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/officer-of-elections/; "Virginia AG presses GOP senator for proof of claims of fraud in statewide elections," Washington Post, October 28, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/virginia-election-chase-fraud-claims-herring/2021/10/28/2cad0a4a-381f-11ec-9bc4-86107e7b0ab1_story.html; "Virginia Department of Elections uses facts to dispel voting myths," Richmond Times-Dispatch, October 29, 2021, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/virginia-department-of-elections-uses-facts-to-dispel-voting-myths/article_2244a950-4041-57fd-9366-a884aff8c3d1.html; "An army of poll watchers - many driven by GOP's 'election integrity' push - turns out across Virginia," Washington Post, October 27, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2021/10/27/virginia-poll-watchers-election/; "Results: The Most Detailed Map of the Virginia Democratic Primary," New York Times, March 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/03/us/elections/precinct-map-virginia-primary.html; "The Handbook - Section 3.2.3.2, Minimum and Maximum Populations Served," Virginia Department of Elections, September 2020, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/media/grebhandbook/2020-individual-chapters/3_Precincts_and_Polling_Places_(2020).pdf; "Election Turnout," Virginia Department of Elections, November 4, 2025, https://enr.elections.virginia.gov/results/public/virginia/elections/2025-November-General/reports (last checked November 6, 2025)

2. "Fairfax Co. registrar fired days before midterm primary," WTOP, June 1, 2018, https://wtop.com/fairfax-county/2018/06/fairfax-co-registrar-fired-days-midterm-primary/; "Fired Fairfax Co. elections head sues after drug charges dropped," WTOP, June 12, 2019, https://wtop.com/fairfax-county/2019/06/fired-fairfax-co-elections-head-sues-after-drug-charges-dropped/; "Fairfax Co. registrar to deny voter registrations over concerns with Va. system," WTOP, January 3, 2018, https://wtop.com/fairfax-county/2018/01/fairfax-co-registrar-to-deny-voter-registrations-over-concerns-with-state-system/; "Charlotte registrar quits amid mismanagement claims," South Boston News and Record, December 9, 2021, https://www.sovanow.com/articles/charlotte-registrar-quits-amid-mismanagement-claims/;

"Virginia lawmakers consider creating new job protections for election officials to prevent political firings," Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 17, 2019, https://richmond.com/news/local/government-politics/virginia-lawmakers-consider-creating-new-job-protections-for-election-officials-to-prevent-political-firings/article_f017f701-26d4-577a-a782-2ada9d7b3662.html; "Two former election officials file federal lawsuits against Nottoway County," Virginia Mercury, September 26, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2022/09/26/two-former-election-officials-file-federal-lawsuits-against-nottoway-county/; "Investigation finds nearly $500,000 in waste, fraud, and abuse in Richmond Elections Office," Virginia Mercury, November 26, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/11/26/investigation-finds-nearly-500000-in-waste-fraud-and-abuse-in-richmond-elections-office/ (last checked November 27, 2024)

3. "Virginia board considers ousting GOP election official accused of sharing voting machine info," Virginia Mercury, May 28, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/05/28/virginia-board-considers-ousting-gop-election-official-accused-of-sharing-voting-machine-info/; "Former Va. Senate GOP leader clashes with election official over assault case," Virginia Mercury, June 27, 2024, https://virginiamercury.com/2024/06/27/former-va-senate-gop-leader-clashes-with-election-official-over-assault-case/ (last checked June 28, 2024)

4. "Electoral Board Job Description," Virginia Department of Elections, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/media/formswarehouse/local-administration/electoral-board/Electoral-Board-Job-Description.pdf; "State Board of Elections," Secretary of the Commonwealth, https://www.commonwealth.virginia.gov/va-government/boards-and-commissions/comprehensive-board-listing/detail/?id=7CD7C5ED-C4C1-DF11-8337-005056BC7B56; "Youngkin names local GOP official, former aide to Chase, as new state elections commissioner," Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 20, 2022, https://richmond.com/news/state-and-regional/youngkin-names-local-gop-official-former-aide-to-chase-as-new-state-elections-commissioner/article_2d9ee742-742f-5325-9692-562bd65c37fc.html; "SB 371 Elections, State Board of; expands membership, appointment of Commissioner of Elections," Legislative Information System, Virginia General Assembly, 2022, https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?ses=221&typ=bil&val=SB371; "Roanoke GOP targets electoral board chair's marriage to Democratic leader," The Roanoke Times, November 3, 2022, https://roanoke.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/roanoke-gop-targets-electoral-board-chairs-marriage-to-democratic-leader/article_14b4d510-5aee-11ed-a04e-17ebf3a3622a.html (last checked May 30, 2024)

5. "Compensation of General Registrars," Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Senate Document No.5, 1992, http://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt130.pdf; "General registrars will get higher salaries, but will have to wait on a new pay scale," Virginia Mercury, February 28, 2019, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2019/02/28/general-registrars-will-get-higher-salaries-but-will-have-to-wait-on-a-new-pay-scale/; "Chair of Hampton Electoral Board accused of racist post resigns," WAVY, April 8, 2022, https://www.wavy.com/news/investigative/chair-of-hampton-electoral-board-accused-of-racist-posts-called-upon-to-resign/; Facebook post by Republican Party of Hampton (VA), April 8, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/RepublicanPartyOfHamptonva/posts/348890067280400; "Hampton official formally removed after racist Facebook post surfaces," Daily Press, April 13, 2022, https://www.pressreader.com/usa/daily-press/20220413/281535114528096; "Electoral Board eliminates most in-person early voting in eastern Loudoun," Loudoun Times-Mirror, December 20, 2023, https://www.loudountimes.com/0local-or-not/1local/electoral-board-eliminates-most-in-person-early-voting-in-eastern-loudoun/article_cd6e6a5a-9ed4-11ee-8194-b73e8537a2a5.html (last checked December 20, 2023)

6. "Title 24.2. Elections - Chapter 3. Election Districts, Precincts, and Polling Places - Article 3. Requirements for Election Districts, Precincts, and Polling Places - - 24.2-310. Requirements for polling places," Code of Virginia, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title24.2/chapter3/section24.2-310/; "Title 24.2. Elections - Chapter 3. Election Districts, Precincts, and Polling Places - Article 3. Requirements for Election Districts, Precincts, and Polling Places - - 24.2-307. Requirements for county and city precincts," Code of Virginia, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title24.2/chapter3/section24.2-307/ (last checked January 4, 2018)

7. "Some state Senate races splitting precinct lines," Daily Progress, October 29, 2019, https://www.dailyprogress.com/election/some-state-senate-races-splitting-precinct-lines/article_c12619e9-80e3-50d7-8051-81f658ee2348.html (last checked October 31, 2019)

8. Senate Bill No. 740 (SB 740), Virginia General Assembly, 2020, http://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?201+ful+SB740H1 (last checked March 14, 2020)

9. "Working at the Polls," Fairfax County, https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/elections/election-officers/working; "Election Officer Manual," Fairfax County, April 2016, p.42, https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/elections/sites/elections/files/assets/election-officer-training/eotm_final_april2016.pdf; "Fairfax Co. projects up to 90% turnout for 2020 election," WTOP, December 6, 2019, https://wtop.com/fairfax-county/2019/12/fairfax-co-projects-up-to-90-turnout-for-2020-election/ (last checked December 8, 2019)

10. "Report: High turnout, large precincts drove long lines in 2012 in Pr. William," Washington Post, June 13, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/report-high-turnout-large-precincts-drove-long-lines-in-2012-in-pr-william/2013/06/13/85f0aa6e-d449-11e2-a73e-826d299ff459_story.html (last checked November 1, 2018)

11. "Operations and Performance of Virginia's Department of Elections," Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, September 10, 2018, p.22, http://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt508.pdf (last checked November 30, 2019)

12. "Voting irregularity found in controversial 94th District election," Daily Press, May 10, 2018, http://www.dailypress.com/news/politics/dp-nws-94th-ballots-20180510-story.html; "Va. election officials assigned 26 voters to the wrong district. It might've cost Democrats a pivotal race," Washington Post,

May 13, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/voters-assigned-to-wrong-districts-may-have-cost-democrats-in-pivotal-virginia-race/2018/05/13/09a9dd8a-5465-11e8-a551-5b648abe29ef_story.html (last checked May 14, 2018)

13. Code of Virginia, Title 1. Administration - Agency 20. State Board of Elections - Chapter 40. Voter Registration - 1VAC20-40-30. Presumptions, https://law.lis.virginia.gov/admincode/title1/agency20/chapter40/section30/ (last checked November 1, 2018)

14. "Map errors determines some Pittsylvania Co. voters were misassigned," WSET, November 29, 2018, https://wset.com/news/local/map-errors-determines-some-pittsylvania-co-voters-were-misassigned; "Registrar determines Republican candidate living in his friend's garage meets residency requirements; petition to disqualify him fails," Cardinal News, April 26, 2023, https://cardinalnews.org/2023/04/26/registrar-determines-republican-candidate-living-in-his-friends-garage-meets-residency-requirements-petition-to-disqualify-him-fails/ (last checked April 26, 2023)

15. "Caroline to adjust its boundary with neighboring Essex county," Free Lance-Star, November 23, 2018, https://www.fredericksburg.com/news/local/caroline/caroline-to-adjust-its-boundary-with-neighboring-essex-county/article_903dbb86-c838-5e66-a358-afcbc2e1ec2c.html (last checked November 27, 2018)

16. "Paper ballots make a comeback in Virginia this fall," Washington Post, October 7, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/paper-ballots-make-a-comeback-in-virginia-this-fall/2017/10/07/724106ec-a92b-11e7-850e-2bdd1236be5d_story.html (last checked November 21, 2018)

17. "Chapter 13 Provisional Ballots," the Handbook, Virginia State Board of Elections, August 2020, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/media/grebhandbook/2020-individual-chapters/13_Provisional_Ballots_(2020).pdf; "Chapter 14

Canvass," the Handbook, Virginia State Board of Elections, October 2019, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/media/grebhandbook/archives/2019-chapters/individual-chapters/14_Canvass_10-19.pdf(last checked November 8, 2021)

18. "Election night mistake changes vote margins - but not outcomes - in Prince William-area House of Delegates' races," Prince William Times, November 4, 2021, https://www.princewilliamtimes.com/news/election-night-mistake-changes-vote-margins-but-not-outcomes-in-prince-william-area-house-of/article_0bc2a07e-3d74-11ec-9ed8-4f6c4133189d.html; "Election official: Vote count correction changes result of Christiansburg council race," The Roanoke Times, November 6, 2021, https://roanoke.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/election-official-vote-count-correction-changes-result-of-christiansburg-council-race/article_c8d72c26-3edb-11ec-b0e9-830e9575ba56.html; "Vote count error prompts Del. Martha Mugler to withdraw concession," The Virginian-Pilot, November 8, 2021, https://www.pilotonline.com/government/elections/dp-nw-mugler-county-20211108-hcr5errchnhvvknqyafomwtqgi-story.html; "What happens after vote counting ends in Virginia?," WVTF, October 23, 2024, https://www.wvtf.org/news/2024-10-23/what-happens-after-vote-counting-ends-in-virginia (last checked October 25, 2024)

19. "With judges' ruling in recount, GOP cements two-seat majority in Virginia House of Delegates," Washington Post, December 8, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2021/12/08/virginia-house-recount-mugler-cordoza-gop/; "Virginia Beach House of Delegates race called for Republican after recount, giving GOP the majority," Washington Post, December 3, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2021/12/03/virginia-house-recount-majority/; "2021 November General - General Assembly," Virginia Department of Elections, https://results.elections.virginia.gov/vaelections/2021%20November%20General/Site/GeneralAssembly.html (last checked December 16, 2021)

20. "Minutes," State Board of Elections, January 8, 2016, p.19, https://www.elections.virginia.gov/Files/Media/Agendas/2016/20160108Minutes.pdf; "Prince William Electoral Board chair under investigation, may lose job," InsideNOVA, January 8, 2016, https://www.insidenova.com/headlines/prince-william-electoral-board-chair-under-investigation-may-lose-job/article_d00ff976-b6e4-11e5-a24e-63715e17f125.html

; "Misconduct at the PWC Electoral Board - Part 1," Prince William Muckraker blog, March 31, 2016, http://princewilliammuckraker.com/2016/03/guiffre-lawson-electoral-board/; "Big changes coming for Prince William County voters," InsideNOVA, July 26, 2013, https://www.insidenova.com/news/politics/big-changes-coming-for-prince-william-county-voters/article_d7fddad6-f4b8-11e2-8591-0019bb2963f4.html; "Report of the Bi-Partisan Election Task Force to the Prince William County Board of County Supervisors," May 22, 2013, http://www.pwcgov.org/government/bocs/Documents/Signed%20Final%20Recommendation%20Report.pdf (last checked September 21, 2018)

21. "Capital letters removed but questions linger," Progress-Index, August 23 2018,

http://www.progress-index.com/news/20180823/capital-letters-removed-but-questions-linger; "State Board of Elections will ask for ouster of two Hopewell Electoral Board members," Progress-Index, September 20, 2018, http://www.progress-index.com/news/20180920/state-board-of-elections-will-ask-for-ouster-of-two-hopewell-electoral-board-members; "Petitions Filed Tuesday To Remove Hopewell Electoral Board Members," Progress-Index, October 11, 2018, http://www.progress-index.com/news/20181010/petitions-filed-tuesday-to-remove-hopewell-electoral-board-members; "Court action on Hopewell Electoral Board delayed," Progress-Index, October 22, 2018, http://www.progress-index.com/news/20181022/court-action-on-hopewell-electoral-board-delayed; "Jury finds Hopewell Electoral Board members negligent; removes them," The Progress-Index, March 1, 2019, https://www.progress-index.com/news/20190301/jury-finds-hopewell-electoral-board-members-negligent-removes-them; "Hopewell coming to grips with registrar's ouster," Progress-Index, March 7, 2019, https://www.progress-index.com/news/20190307/hopewell-coming-to-grips-with-registrars-ouster; "Electoral boards likely to retain authority to fire registrars," InsideNOVA, March 29, 2019, https://www.insidenova.com/news/arlington/electoral-boards-likely-to-retain-authority-to-fire-registrars/article_4caafc4c-5179-11e9-a5bf-779a51685bfb.html; "Judge Dismisses Former Hopewell Registrar's Lawsuit Against Electoral Board," Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 31, 2020, https://www.richmond.com/news/plus/judge-dismisses-former-hopewell-registrar-s-lawsuit-against-electoral-board/article_002b1992-e236-51ad-8f55-b0dbbca77804.html (last checked January 31, 2020)

22. "Three Hopewell City Councilors, including mayor, lose," Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 7, 2018, https://www.richmond.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/three-hopewell-city-councilors-including-mayor-lose/article_52514fc3-ab0b-51ef-8d4a-a5e2d4a75f5a.html (last checked November 7, 2019)

23. "Richmond registrar: No hearing on Agelasto voter registration status," Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 10, 2018, https://www.richmond.com/news/local/city-of-richmond/richmond-registrar-no-hearing-on-agelasto-voter-registration-status/article_ee029a2a-7f8c-5893-aa74-4b66f920dc57.html (last checked December 12, 2018)

24. "In win for GOP, Virginia county ordered to assign new poll workers," Courthouse News Service, November 2, 2022, https://www.courthousenews.com/in-win-for-gop-virginia-county-ordered-to-assign-new-poll-workers/; "Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Temporary Injunction and Demurrer and Motion to Dismiss Complaint," Republican Party of Virginia et al. vs. Prince William County Electoral Board, Circuit Court for Prince William County, October 31, 2022, https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/gop-prince-william-brief.pdf; "Top Prince William election official says he's quitting amid dispute with local GOP," Virginia Mercury, October 7, 2022, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2022/10/07/top-prince-william-election-official-says-hes-quitting-amid-dispute-with-local-gop/ (last checked November 3, 2022)

25. "Hounded by baseless voter fraud allegations, an entire county's election staff quits in Virginia," NBC News, April 10, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/elections/buckingham-county-virginia-election-staff-quits-baseless-voter-fraud-rcna76435 (last checked April 10, 2023)

26. "Buckingham Electoral Board fires Republican registrar after less than a month in the job," Virginia Mercury, May 9, 2023, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2023/05/09/buckingham-electoral-board-fires-republican-registrar-after-less-than-a-month-in-the-job/; "Buckingham registrar charges $200 'convenience fee' in FOIA feud with county official," Virginia Mercury, May 5, 2023, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2023/05/05/buckingham-registrar-charges-200-convenience-fee-in-foia-feud-with-county-official/; "Buckingham County," Virginia Public Access Project, https://www.vpap.org/localities/buckingham-county-va/; "The local toll of election denialism: Virginia county loses second registrar in 2 months," NBC News, May 10, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna83319 (last checked May 11, 2023)

27. "Buckingham GOP nominates recently fired registrar for seat on elections board," Virginia Mercury, May 19, 2023, https://www.virginiamercury.com/2023/05/19/buckingham-gop-nominates-recently-fired-registrar-for-seat-on-elections-board/ (last checked May 20,2023)

28. "An election chief says the 'big lie' ended her career. She's fighting back," Washington Post, November 2, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/11/02/lynchburg-elections-registrar-lawsuit/ (last checked November 2, 2023)

29. "Fairfax elections staff trying to keep up as another wave of special elections hits," FFX Now, January 13, 2026, https://www.ffxnow.com/2026/01/13/fairfax-elections-staff-trying-to-keep-up-as-another-wave-of-special-elections-hits/ (last checked January 14, 2026)

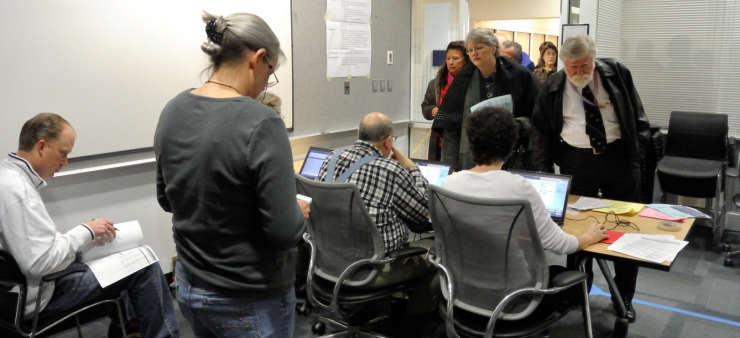

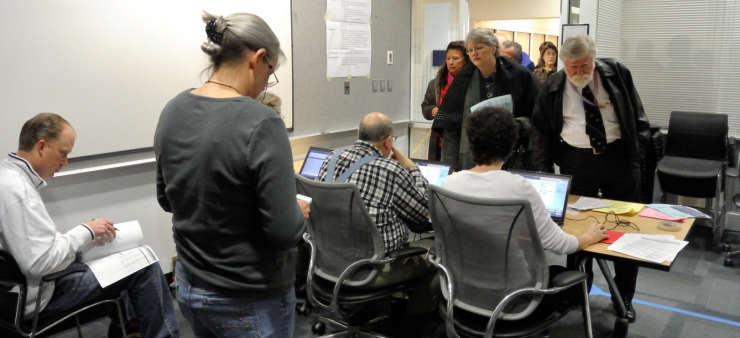

General Registrars are responsible for preparation of pollbooks used by poll workers (Officers of Election) to process voters

Source: Fairfax County, Election Officer Manual (April 2016, p.105)

Virginia Government and Virginia Politics

Virginia Places