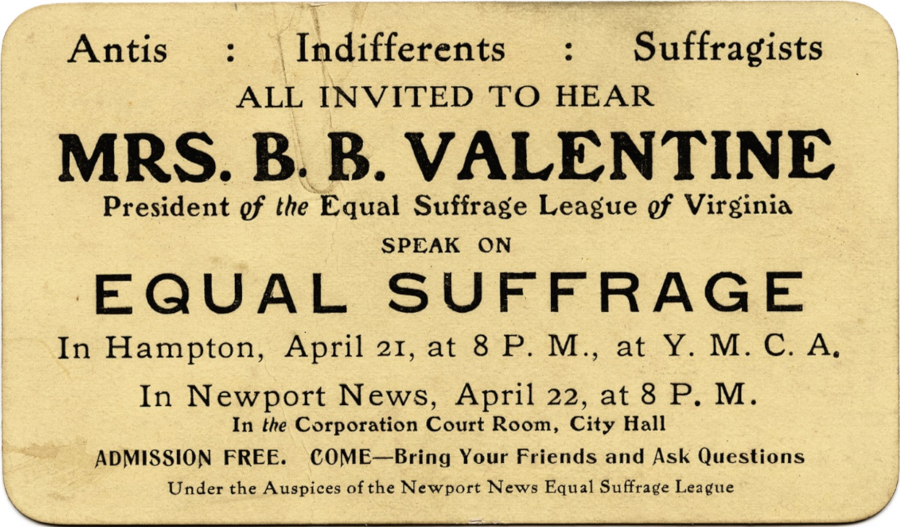

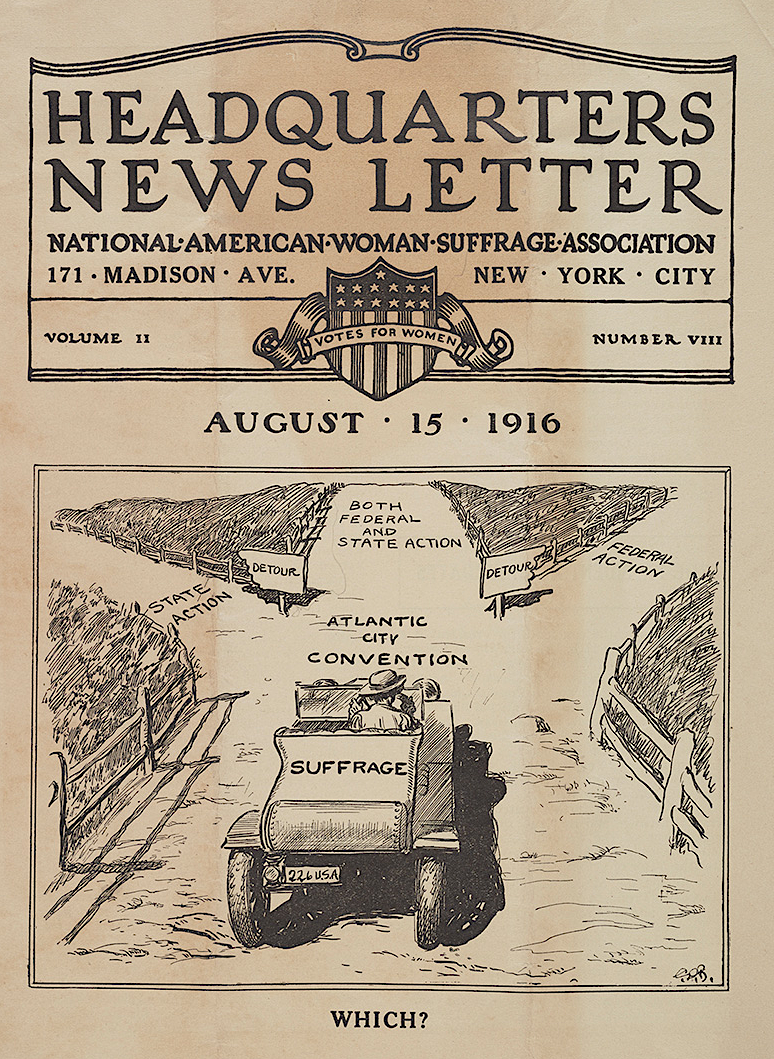

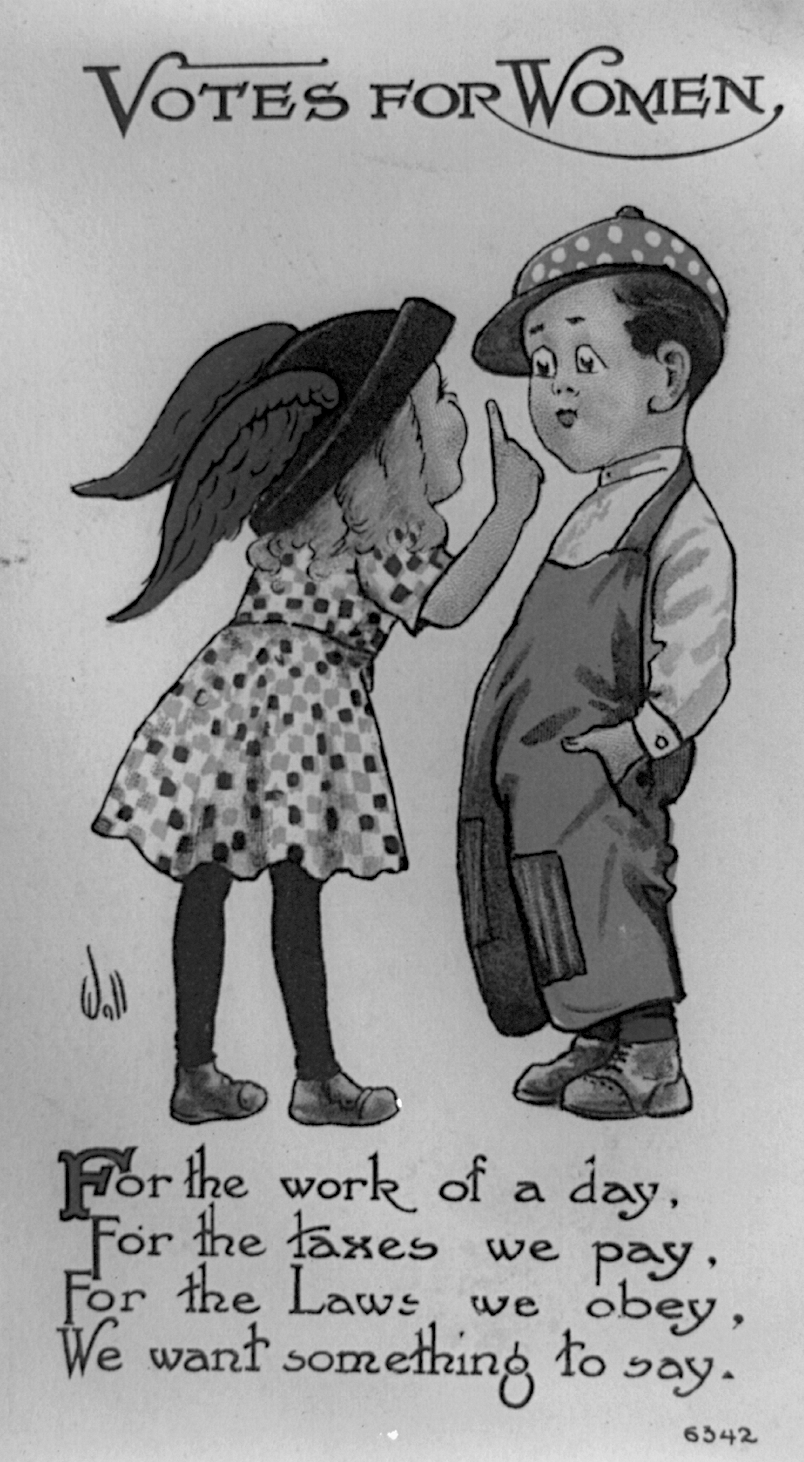

the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia championed the expansion of the electorate to allow women to vote

Source: Library of Virginia, Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records Are Coming to Making History: Transcribe

the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia championed the expansion of the electorate to allow women to vote

Source: Library of Virginia, Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records Are Coming to Making History: Transcribe

The women's movement, started in 1848, split over the 15th Amendment in 1869. The American Woman Suffrage Association led by Lucy Stone supported the amendment, even though it sacrificed the opportunity to get votes for women as well as black men.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony objected to the prospect of men less educated and qualified that white women getting the vote, without also including all women. They refused to support the 15th Amendment and organized the separate rival National Woman Suffrage Association. That organization tried to get Federal courts to require women be given equal voting rights under the 15th Amendment, since the 14th Amendment blocked states from denying to "any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

In the 1875 decision Minor v. Happersett, the US Supreme Court justices noted that Section 2 of the 14th Amendment referred to "male citizens" and "male inhabitants." The court determined that women were not citizens entitled to vote. That decision ended efforts through the courts to win women the vote. The only choice remaining was to work with state legislatures and the US Congress, getting men to choose voluntarily to grant women the right to vote.

The official split in the leadership of the suffragist effort lasted 20 years. The leaders of the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association finally reunited and formed the united National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890.

Virginia was a follower, not a leader, in the effort to grant women the right to vote. The Virginia Company had limited voting to just men since the first election for a General Assembly in 1619.

Source: Jamrestown Rediscovery Education, Beyond Brideships 1: "Company Women and King's Daughters"

Across the Potomac River in 1648, Margaret Brent famously demanded the right to vote as she managed the estate of Maryland's colonial governor Leonard Calvert. Maryland's laws and taxes affected the value of the estate, but she was blocked from voting. That led to her migrating to Virginia, where she bought property but did not repeat the demand for suffrage.

The first woman to hold an official office in Virginia was Clementina Rind in Williansburg. She was appointed as the public printer in May 1774, after her husband died. She had unusual energy, expertise, and political connections, and managed to publish the Virginia Gazette without skipping an issue. Clementina Rind did not request the right to vote, and operated her business without a voice in who would represent her in the House of Burgesses.

The first concerted effort to mobilize women to support the right to vote occurred after Virginia ratified the 15th Amendment and adopted a new state constitution after the Civil War. The convention which assembled in Richmond from December 3, 1867, to April 17, 1868 to write the new constitution considered broadening the franchise. The leader, Judge John C. Underwood, supported allowing white women to vote along with black men. In the end, only black men were empowered. In 1870, the 15th Amendment authorized voting by black men nationwide, but women were still excluded.

A woman in Missouri, Virginia Minor, sued her registrar and claimed that as a citizen of the United States she was entitled to vote. She claimed that the Fourteenth Amendment prevented a state from making or enforcing any law which abridged her privileges and immunities of a citizen of the United States, and she was entitled to equal protection of the laws.

In 1875, the US Supreme Court ruled in Minor v. Happersett that she was wrong, because:1

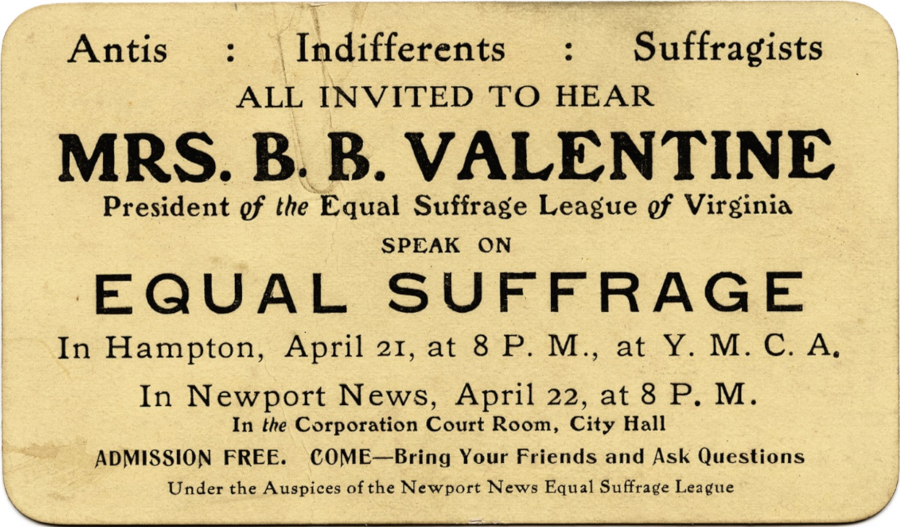

black men got the right to vote 50 years before women

Source: Library of Virginia, "The first vote" / AW ; drawn by A.R. Waud (published in Harper's Weekly, November 16, 1867)

Anna Whitehead Bodeker organized the Virginia State Woman Suffrage Association in 1870. She tried to vote a year later in Richmond, but the organization withered after that effort.

Orra Gray Langhorne in Lynchburg created the Virginia Suffrage Society (renamed Virginia Suffrage Association) in 1893, as a part of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She petitioned the General Assembly for the right to vote in 1894, but was ignored. A sustainable push for suffrage required more women in Virginia to get together and focus on the cause. Langhorne blamed the determined opposition of religious leaders for the failure to gain traction in Virginia.2

In 1919 Carrie Chapman Catt achieved what Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and others had advocated. The US Congress passed an amendment to the Constitution saying:3

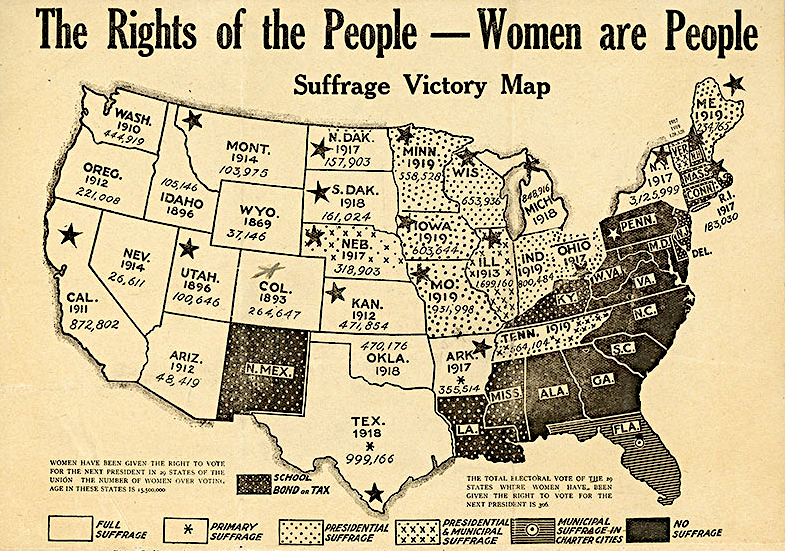

Western states were the first to allow women to vote. Other states granted women the right to vote in just some types of elections while Southern states maintained traditional gender roles.

The first national efforts of the National American Woman Suffrage Association focused on individual states, getting more of them to authorize women's suffrage. Once there were 36 states in which women were already voting, then the representatives of those states in the US Congress could pass a constitutional amendment. After the same 36 states ratified the amendment, the 12 remaining states would be forced to enfranchise women and suffrage would be expanded nationwide.

women's suffrage was adopted initially in western states

Source: Cornell University Library, The Awakening (1915)

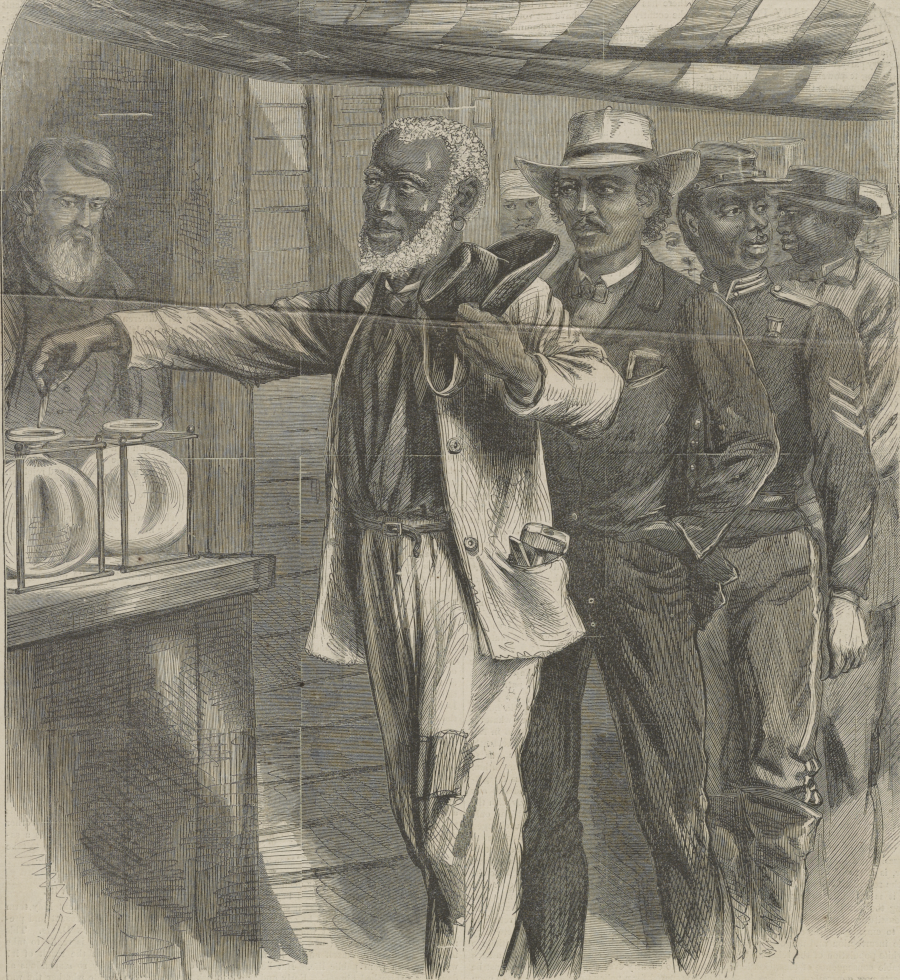

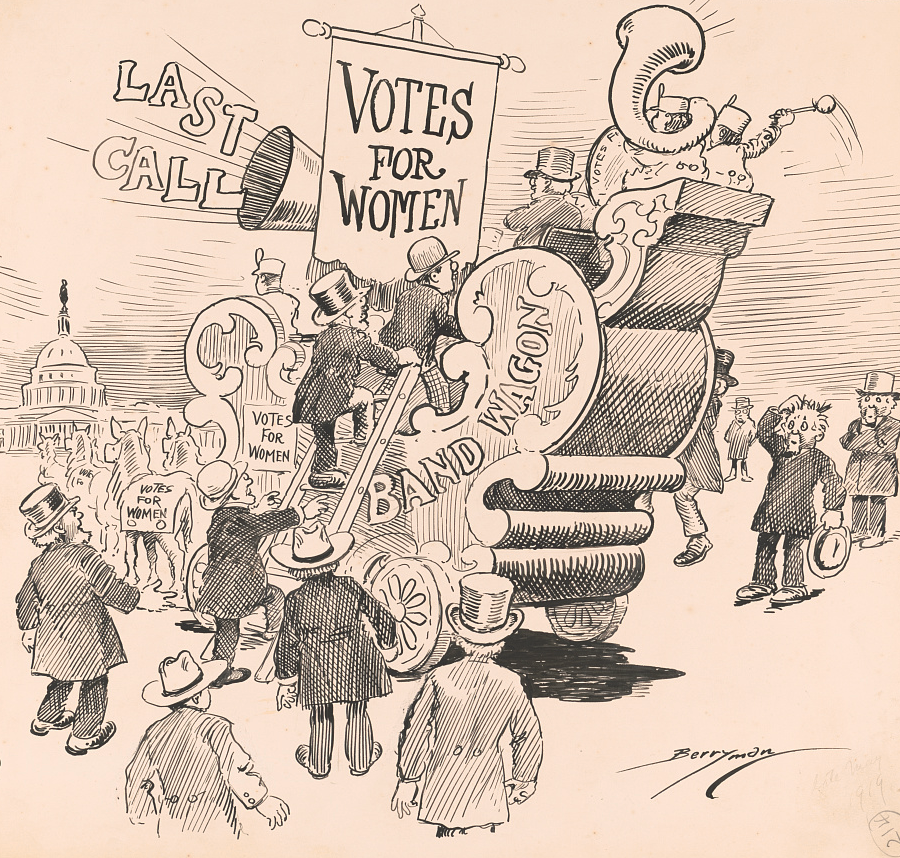

Catt's 1916 "winning plan" was pushed by the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Its priority was to have the US Congress pass an amendment to the Constitution and then get ratification by the states. Through that approach, women in all 48 states and the territories (including Hawaii and Alaska) would gain the right to vote.

The "winning plan" of 1916 reflected a shift in strategy. The state-by-state ratification process was slow, requiring fragmented efforts by individual chapters of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The 1916 "winning strategy" allowed Catt and her team to narrow their efforts to just the members of Congress, who were easier to contact in Washington, DC with effective advocates concentrated in one place.

the shift from state-based to Congress-based lobbying was a winning plan

Source: Library of Congress, Carrie Chapman Catt's "Winning Plan" (1916)

Catt presented the National American Woman Suffrage Association as moderate, not militant. A key member, Alice Paul, organized a parade of suffragists on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1913 that stole the spotlight from Woodrow Wilson's arrival in Washington, DC for his inauguration.

In 1914, Alice Paul sought to actively organize political campaigns against Democratic members of Congress. She wanted to challenge members who had the opportunity to use their power to advance suffrage, but had not done so. In contrast, Catt sought to sway the minds and then the votes of elected officials, rather than challenge them and potentially create enemies.

Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt split over their different approaches. Paul left the National American Woman Suffrage Association and organized the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in 1914. That organization evolved into the National Woman's Party in 1916.

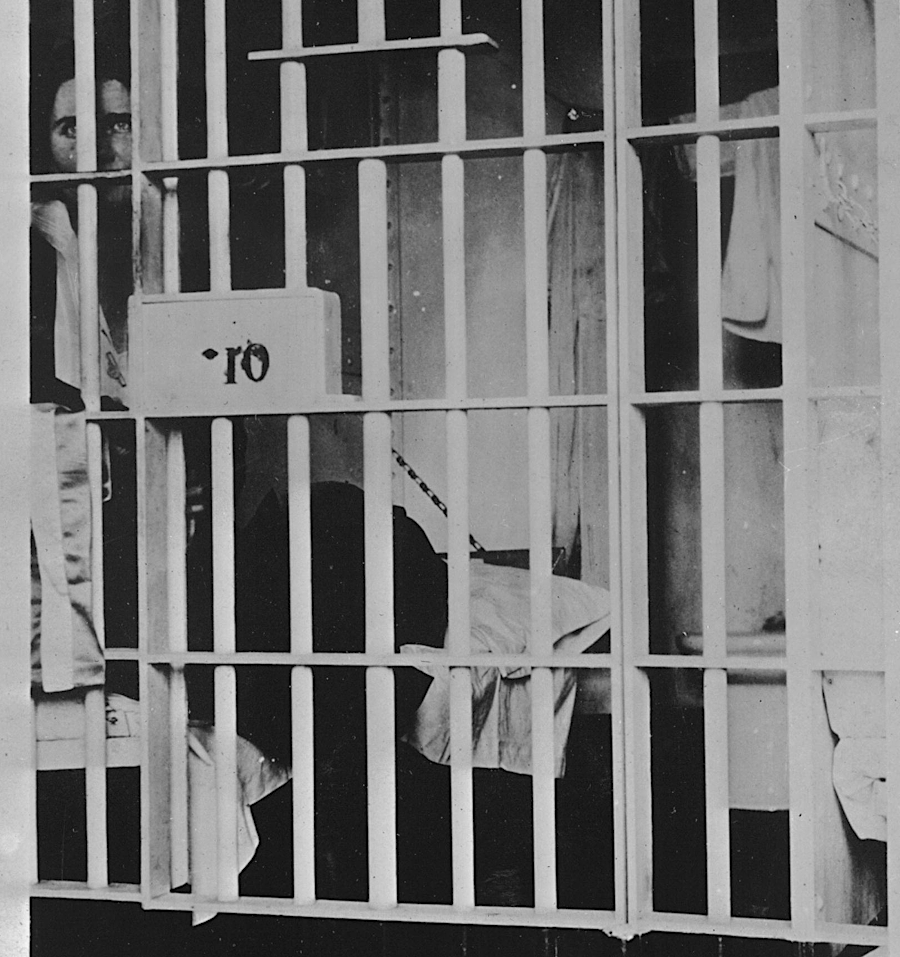

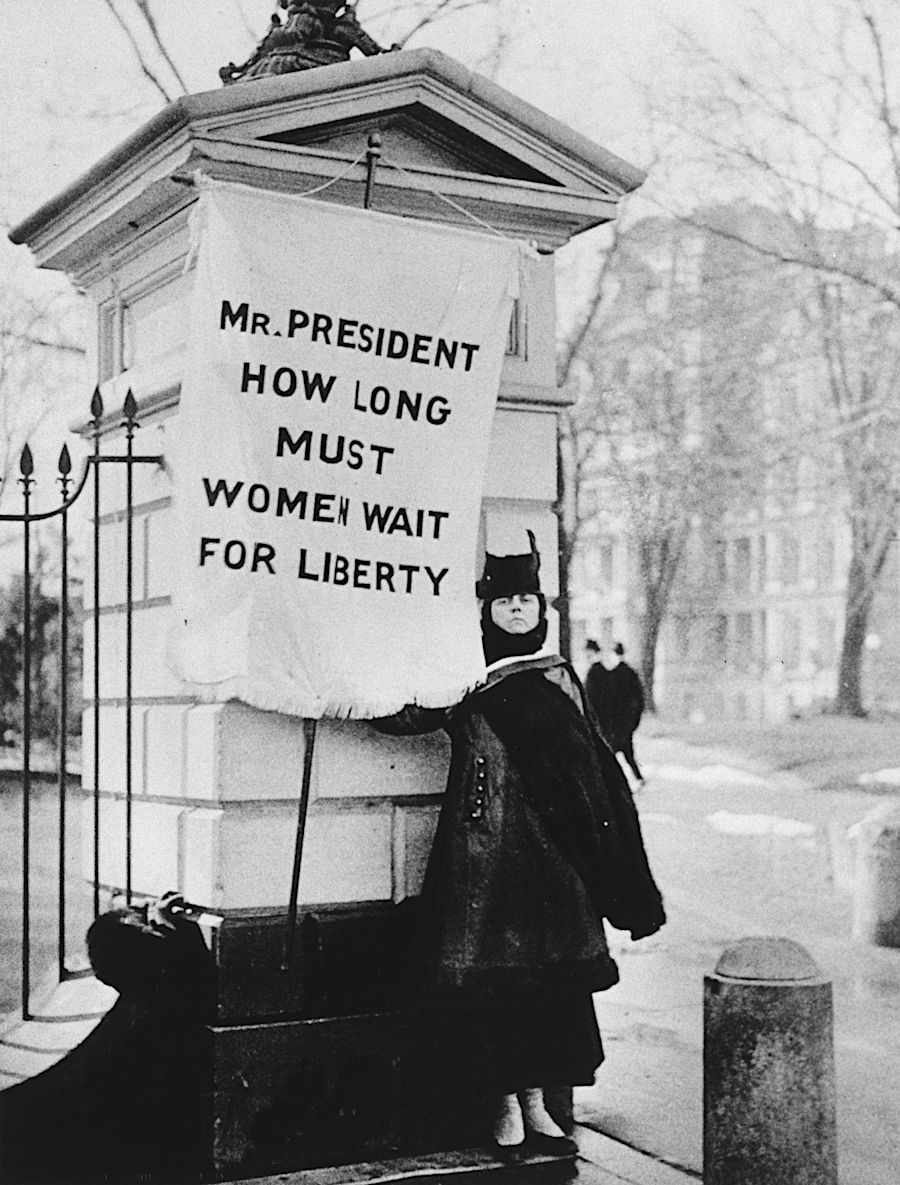

Paul's more-assertive National Woman's Party picketed the White House, seeking to shame Wilson into supporting suffrage. Women with signs stood at the gates as Silent Sentinels to embarrass President Wilson and try to force the US Congress to act. Paul and others were arrested and sent to the Occoquan Workhouse at Lorton, after District of Columbia police claimed the women were obstructing traffic with their picketing outside the fences at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

When Alice Paul went on a hunger strike, prison officials force-fed her through a tube pushed down her throat into her stomach. The suffragists received rough treatment at the Fairfax County prison, including a "night of terror" on November 14, 1917.

Ending the bad publicity may have been a factor in President Wilson choosing to openly support women's suffrage. He wanted public support for the war effort, not criticism that it was hypocritical to fight in Europe for freedoms not offered in America. As Alice Paul noted:4

Silent Sentinels were arrested and sent to the District of Columbia "Women's Workhouse," which was located at Lorton in Fairfax County

Source: Library of Congress, Vida Milholland [in jail cell]

Catt and the other leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association thought the confrontational approach was counter-productive. Instead, the National American Woman Suffrage Association generated support for American soldiers involved in World War I. That helped President Wilson. He had been re-elected in 1916 on the slogan "he kept our boys out of war," but switched in 1917 to get the United States into the Great War (known now as World War I).

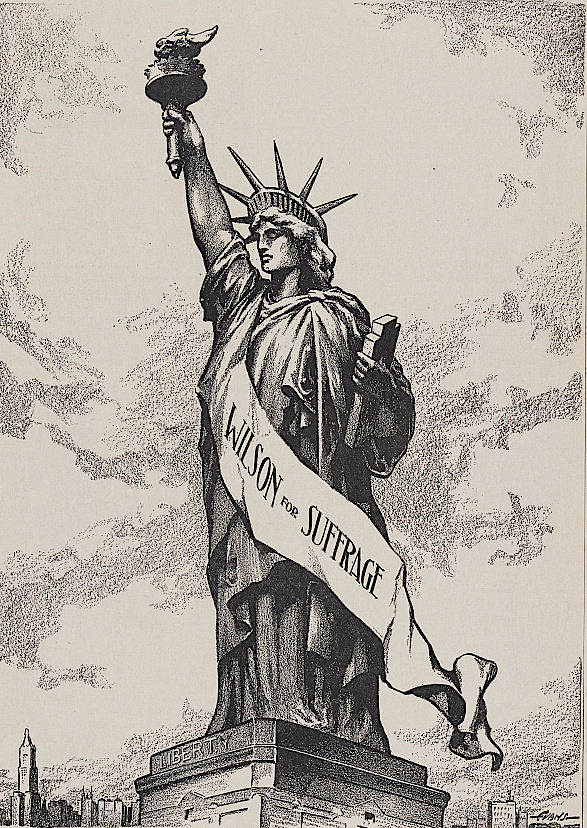

Carrie Chapman Catt convinced President Woodrow Wilson to support a woman's right to vote

Source: Library of Congress, The new freedom (in Puck magazine, 1915)

Through personal conversations and socially-respectable political pressure, Catt ultimately convinced President Wilson to endorse the 19th Amendment publicly. He moved from his original stance that suffrage was an issue to be decided state by state.

Catt also convinced Wilson to actively push for its adoption by a reluctant US Senate, using his political capital to advance women's suffrage. He spoke in front of the US Senate in September 1918, but the next day the suffrage amendment fell two votes short of passage. After the November 1918 elections, three new senators took their seats. Wilson successfully lobbied them, and in June 2019 the amendment finally passed.5

The Silent Sentinel pickets of the National Woman's Party received headlines in 1917. They are commemorated today; the National Park Service announced in 2020 that a portion of the White House fence where they held picket signs would be placed at the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial in Lorton, Virginia.

However, the most effective political pressure between 1913-1919 that led to action by the US President, approval by the US Congress, and ratification of the 19th Amendment by 36 states was organized by Carrie Chapman Catt's National American Woman Suffrage Association. That group was less-confrontational in public, and more willing to compromise with legislators.6

a Silent Sentinel of the National Women's Party, picketing the White House on January 30, 1917

Source: National Archives, Photograph of Flag Bearer for Women's Rights Standing Near White House

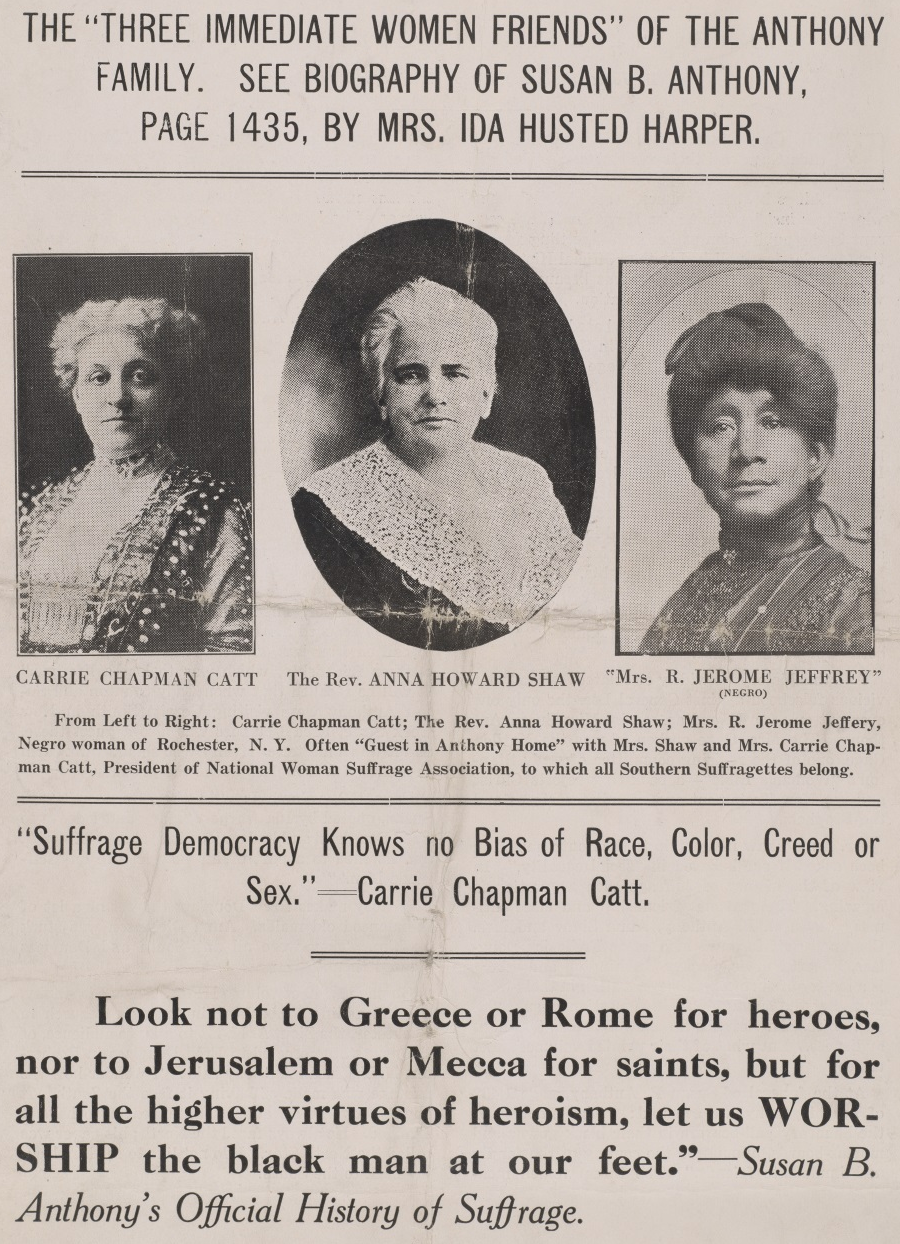

Both Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt were reluctant to ensure black as well as white women would be able to vote. Paul's National Woman's Party sought to exclude black women from a major suffrage parade. Catt's National American Woman Suffrage Association allowed chapters to exclude blacks.

Suffrage advocates reassured US Senators in southern states that voter suppression techniques used on black men would be equally effective in restricting voting opportunities of black women. The expansion of the voting pool to allow white women to vote, while constraining the votes of black women, would increase the power of the white majority in segregated states such as Virginia. In trying to get support for women's suffrage in Mississippi and South Carolina, Catt stated:7

When Congress passed the constitutional amendment, only 30 states had allowed women an opportunity to vote. Of those, nine allowed women to vote only in presidential elections. The ratification effort required an uphill battle to get six legislatures to authorize women to vote for the very first time, and to broaden those rights in other states.8

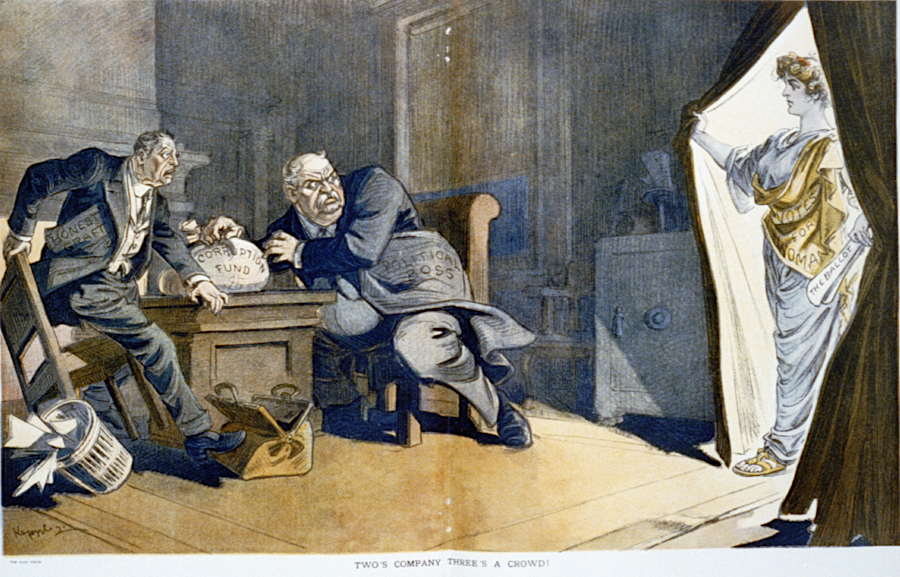

women claimed their votes would result in more-honest government

Source: Library of Congress, Two's company three's a crowd! (in Puck magazine, February 28, 1914)

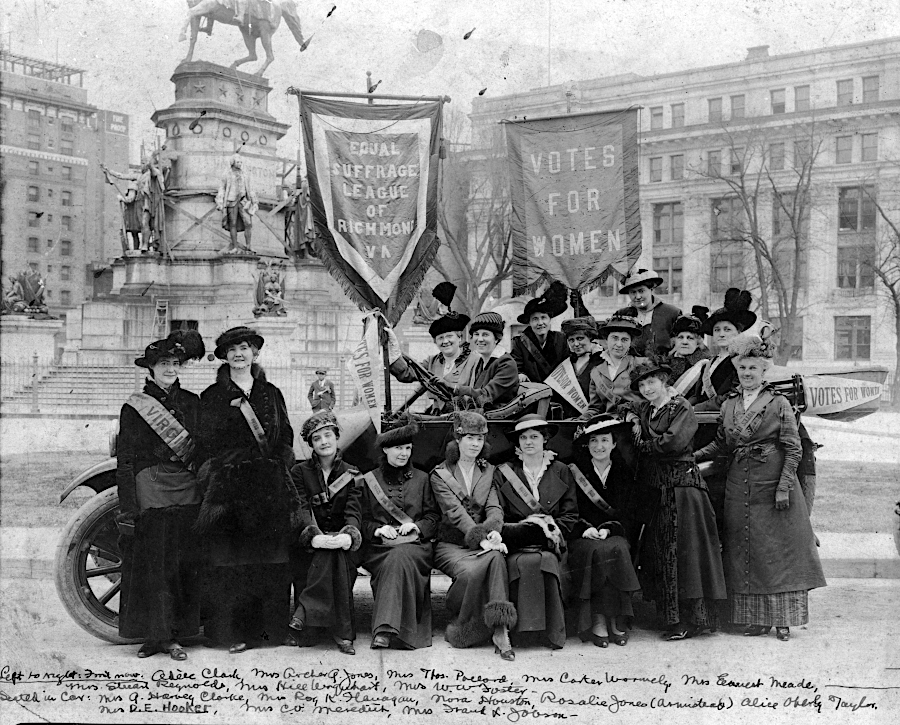

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was established in 1909. In Richmond, 18 socially-influential women organized it after two meetings at the home of Anne Clay Crenshaw on Franklin Street, and:9

in 1909, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia organized in the Crenshaw family home at 919 West Franklin Street in Richmond

Source: Wikipedia, Equal Suffrage League of Virginia (by Morgan Riley)

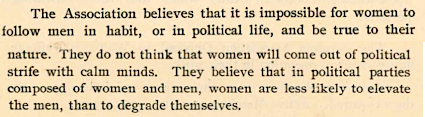

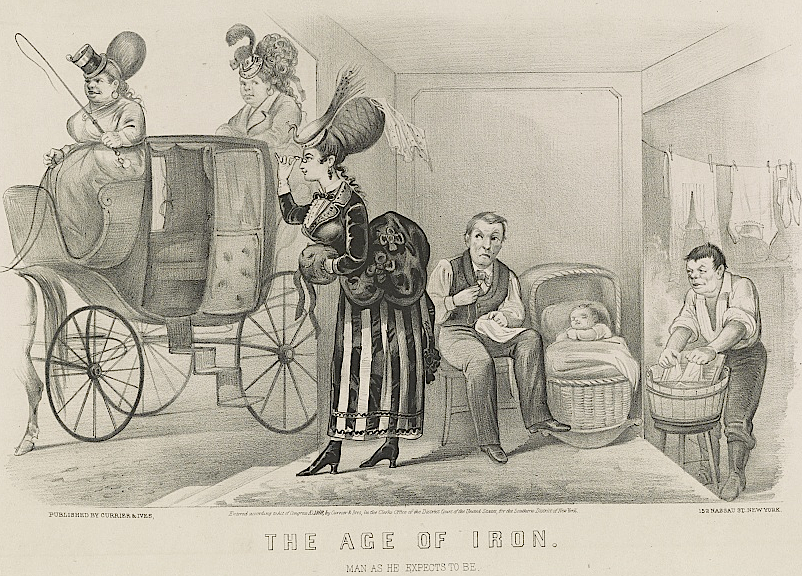

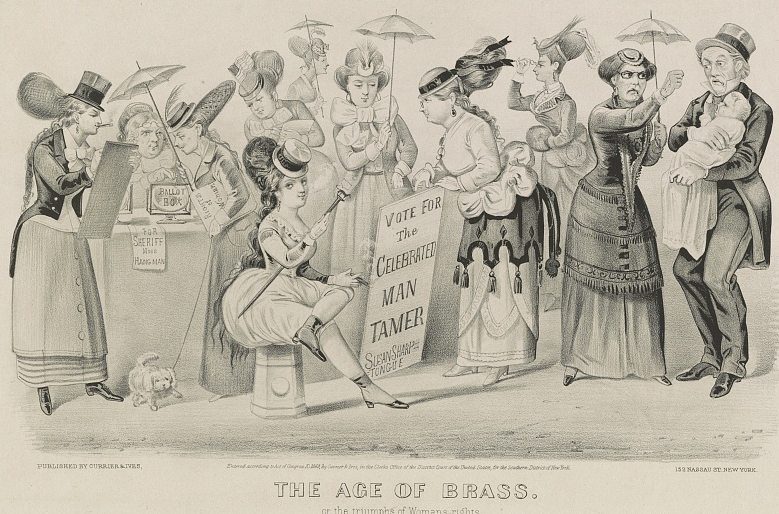

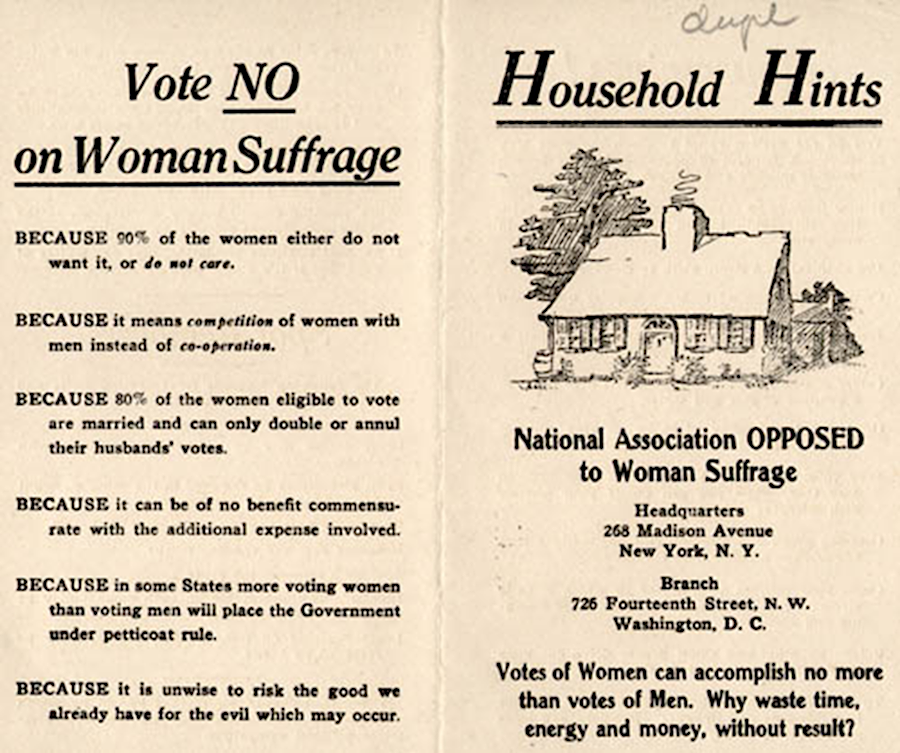

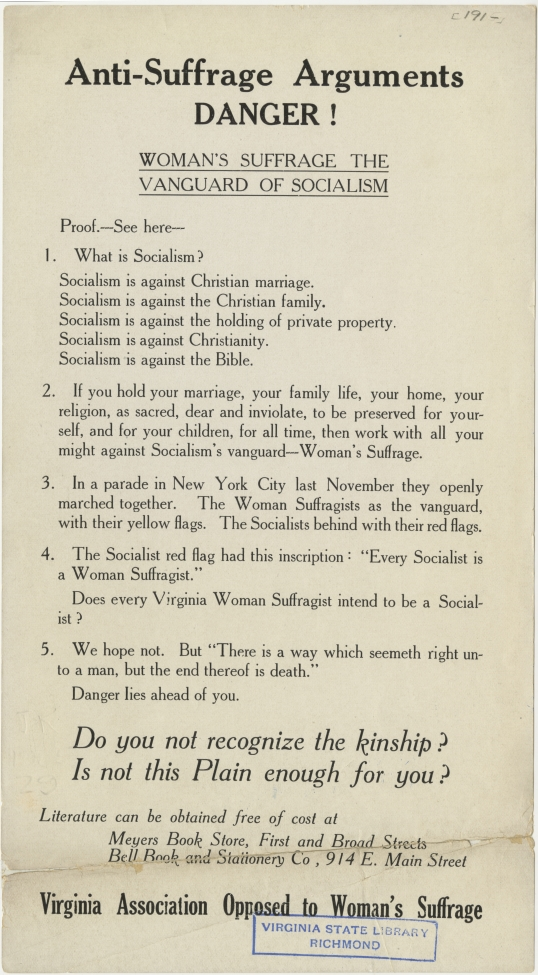

One of the two key arguments in opposition to women's suffrage was that expanding the right to vote would threaten traditional gender patterns. Virginia was culturally conservative, honoring its heritage and highlighting its historical sites. Men considered themselves more qualified than women to manage public affairs and resolve conflicts, and opponents of women's suffrage agreed. Empowering women could create "petticoat rule" and reduce the authority of men who had controlled Virginia's government since the first vote in 1619.

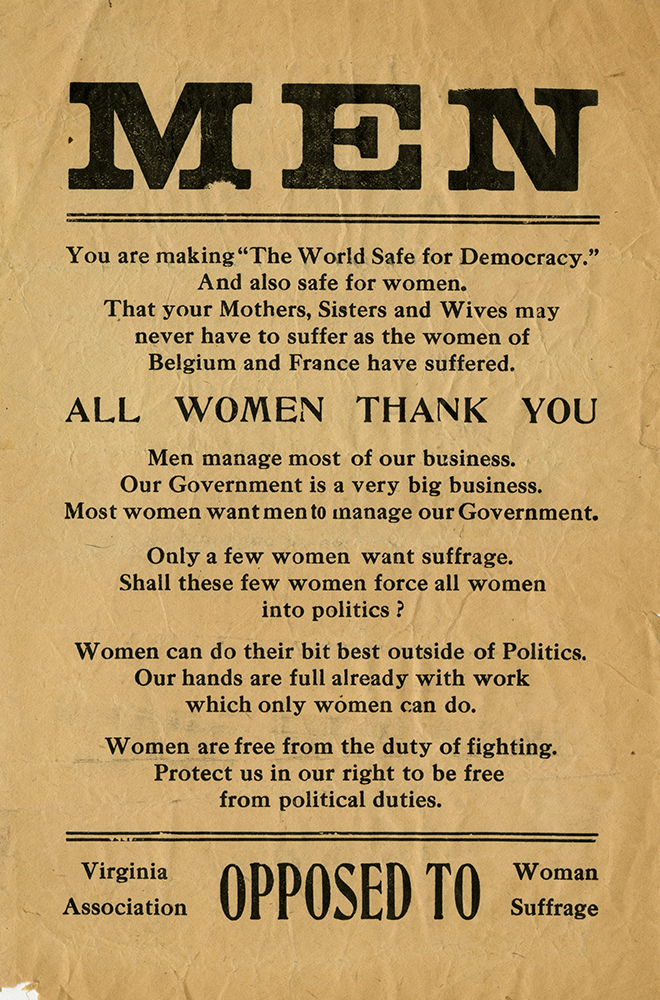

the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage argued that voting would degrade the conduct of women, rather than improve the conduct of men

Source: UnCommonwealth blog, Library of Virginia, Woman Suffrage - The Vanguard Of Socialism (June 17, 2020)

Allowing women to vote would, in theory, undermine the husband's role in the family. There was a wide perception that men and women should control separate spheres; God and nature had defined separate roles for separate sexes. Woman should raise the children and manage the household while men should earn the family's income.

anti-suffragists argued that if women could vote, then gender roles would reverse and men would become responsible for child care and laundry

Source: Library of Congress, The age of iron. Man as he expects to be (Currier & Ives, c.1869)

if women lined up at a ballot box, the men would have to hold a baby at the end of the line

Source: Library of Congress, The age of brass. Or the triumphs of woman's rights (Currier & Ives, c.1869)

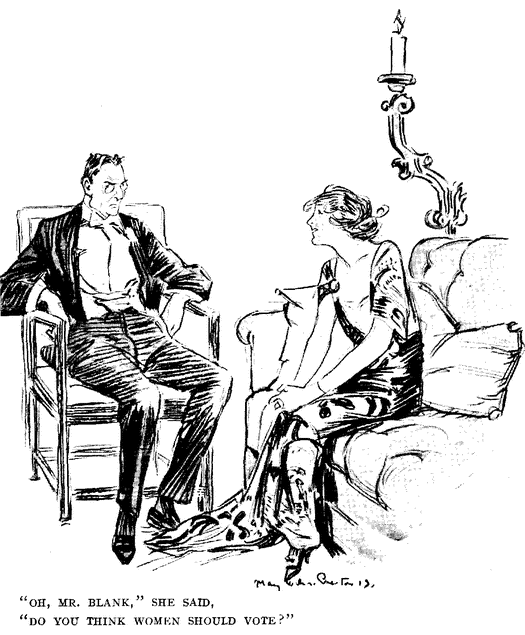

opponents used cartoons to belittle men who supported women's suffrage

Source: National Women's History Museum, National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage

Such a division of labor was more valid in the upper class households, while in working class families both adults might have to work. In the homes of white men with wealth and status, women of color worked daily as maids who cleaned, cooked, and cared for the children.

traditionalists feared that women's suffrage would disrupt the traditional family and threaten the authority of men

Source: Library of Congress, How it feels to be the husband of a suffragette (image 22)

opponents of women's suffrage emphasized that it would disrupt traditional gender roles without benefitting women

Source: Jewish Women's Archive, Pamphlet distributed by the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage

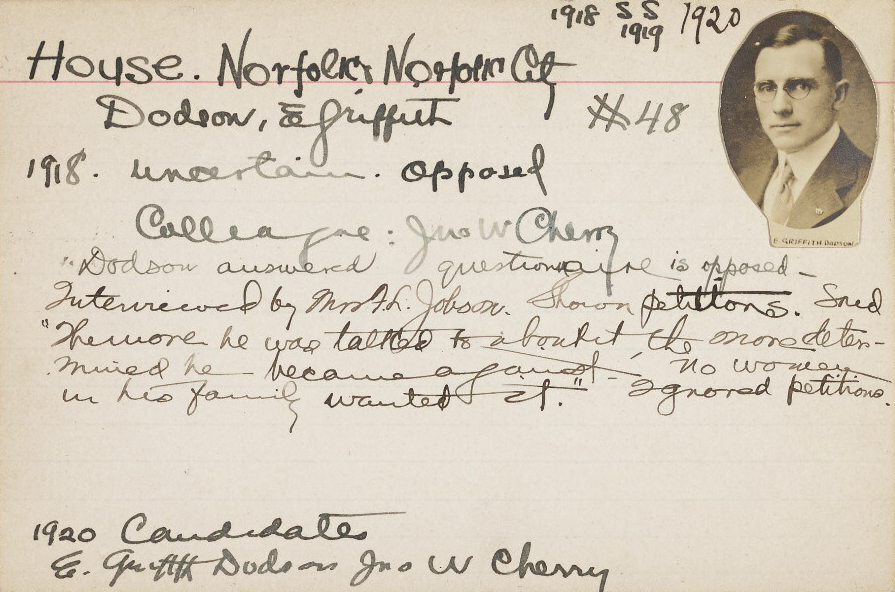

Under the leadership of Lila Meade Valentine, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia allied with Carrie Chapman Catt and the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Virginia's women became part of the organized national suffragist effort, but in the male-dominated Old Dominion the level of support was low. The Equal Suffrage League hired a paid organizer, Eudora Woolfolk Ramsay, to help create local chapters outside of Richmond. According to Valentine, Ramsay had a standard approach to start a group when she arrived in a new community. She:10

By 1916 there were 115 Equal Suffrage League chapters across the state. They were led by elite and educated white women, and had support among many of the elite and educated white men. They argued that a woman's voice and a woman's vote would be valuable on certain key issues traditionally associated with motherhood, including education, health, and child labor.

The initial focus of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was to amend the 1902 Virginia constitution, not the US Constitution. Pushing for a change in gender roles was a challenge in tradition-focused Virginia. Starting in 1912, the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage organized efforts to block any amendment to the state constitution allowing women to vote.

Alice Paul led a more-ambitious, more-outspoken National Women's Party. It became more active in Virginia as the US Congress was approving the 19th Amendment in 1919. The National Women's Party members were concentrated in just Norfolk, however, while the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia attracted members throughout the state.

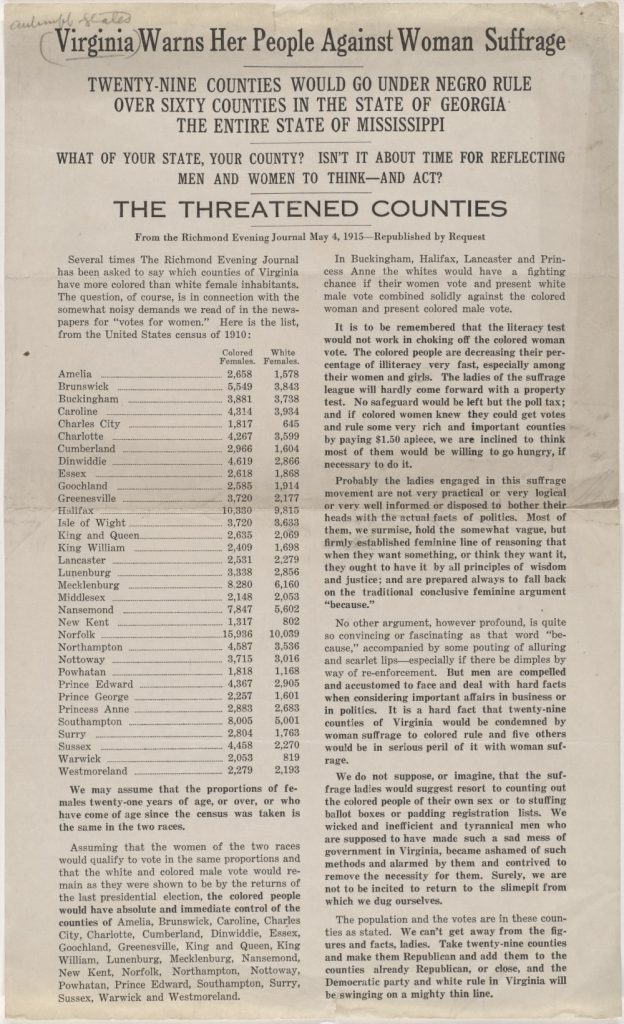

The other key argument used by opponents was to claim that women's suffrage was a step down the slippery slope to granting equal rights to people of color. Republicans who controlled the Federal government (until a split within that party led to the election of Woodrow Wilson in 1912) might require equal treatment of black and white women.

The Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage organized in 1912. Its name made the organization's purpose clear.

the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage argued after the United States entered the Great War in 1917 that woman's suffrage would force all women into politics

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University, MEN. You are making "The World Safe for Democracy"

One Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage pamphlet claimed that if black women gained the right to vote, they would control elections. Black women outnumbered white women in some jurisdictions, and "Twenty Nine Counties Would Go Under Negro Rule." The claim ignored the effective voter suppression efforts implemented after passage of the 1902 state constitution, constraining the ability of blacks to register or vote. Instead, the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage argued that expanding suffrage would cause great harm by adding black women to the voter rolls:11

opponents of women's suffrage emphasized claims that people of color would gain political power

Source: Library of Virginia, "Let Our Vote Be Cast:" African American Women And The Suffrage Movement In Virginia

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia chose not to argue that black women should have the same rights as white women. It appealed to traditional white men by claiming women voters would encourage "municipal housekeeping," and sought to minimize claims that sexual equality would lead to racial equality.

Black women organized the National Association of Colored Women and supported granting all women the right to vote, but the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was a whites-only organization. President Valentine wrote about the organization's conscious decision to avoid supporting black women:12

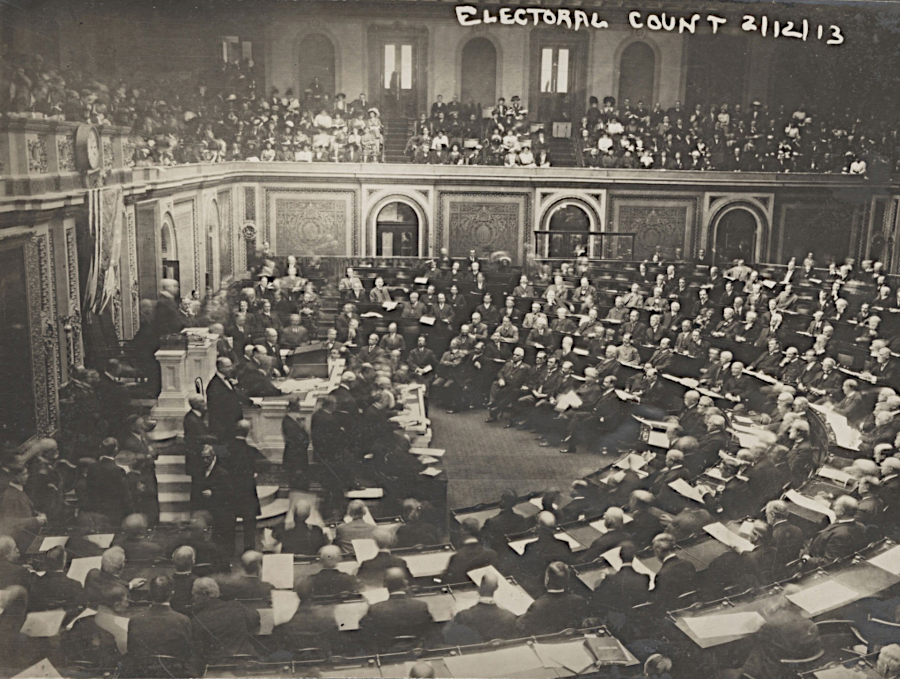

when the House and Senate counted electoral votes in 1913 formalizing Woodrow Wilson's election, the only women in the room were guests in the gallery

Source: US House of Representatives, Electoral College Fast Facts

After the General Assembly rejected an amendment to the state constitution in 1912, 1914, and 1916, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia shifted strategy. It pushed for just an amendment to the US Constitution, recognizing that change could be imposed on the state faster than it would be endorsed by Virginia's white men.

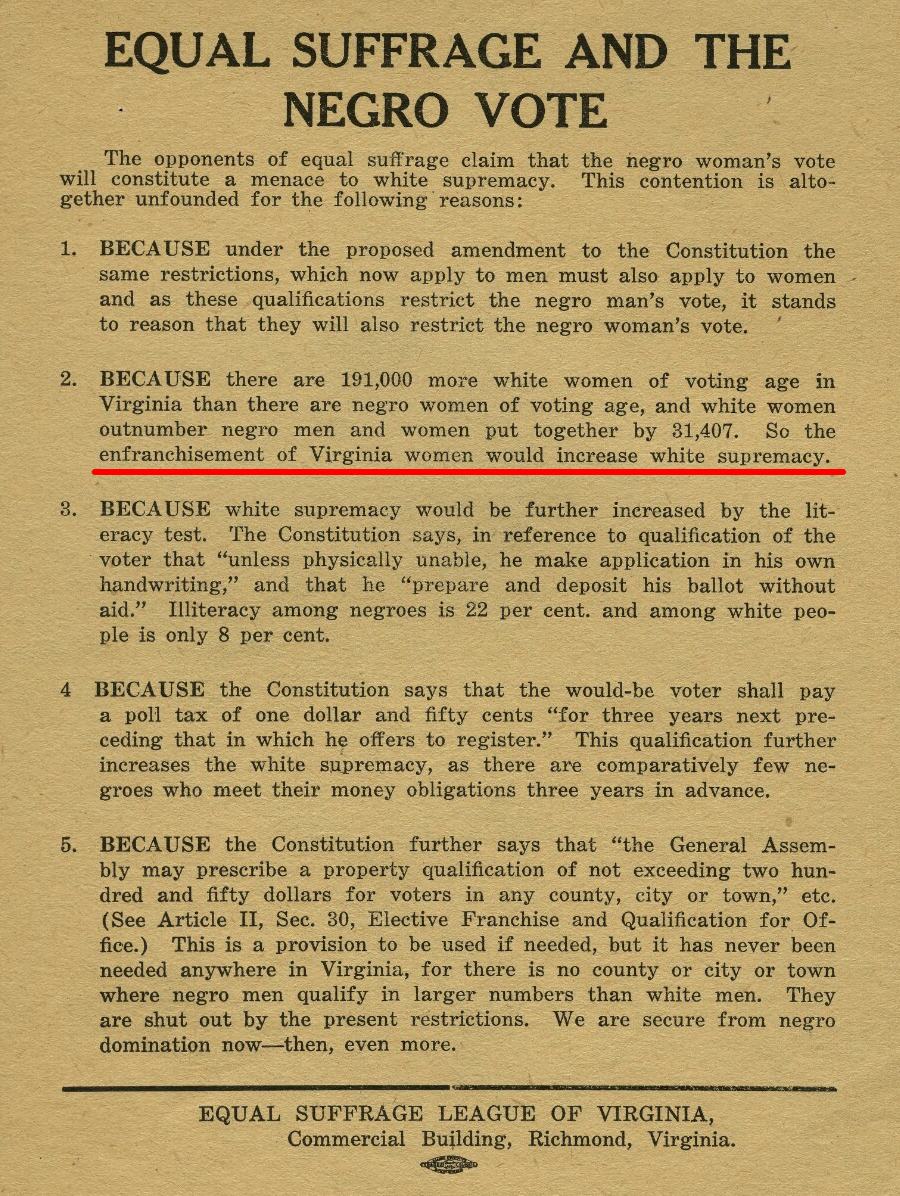

the Equal Suffrage League highlighted how women's suffrage would enhance white supremacy

Source: Virginia Tech Public History, Virginia Political History Podcast, Episode 1 - Suffrage in Virginia

When the US Senate finally approved the proposed 19th Amendment, support in Virginia for women's suffrage was still limited to a narrow group of elite white women. Nearly all blacks who might have supported the amendment had been cut out of the political process, and what became the Byrd Organization had full control over the Democratic Party that dominated politics.

There were no interest groups which could effectively force the Democratic Party to expand the electorate within the state. After proclamation of the 1902 state constitution and implementation of both the poll tax and voter registration constraints, Virginia's political leaders were largely immune to the pressure-group politics that helped suffragists advance their agenda in other states. When the US Congress approved the 19th Amendment, the only vote in favor from the Virginia delegation came from C. Bascomb Slemp, a Republican representing the "Fighting Ninth" district in Southwest Virginia.13

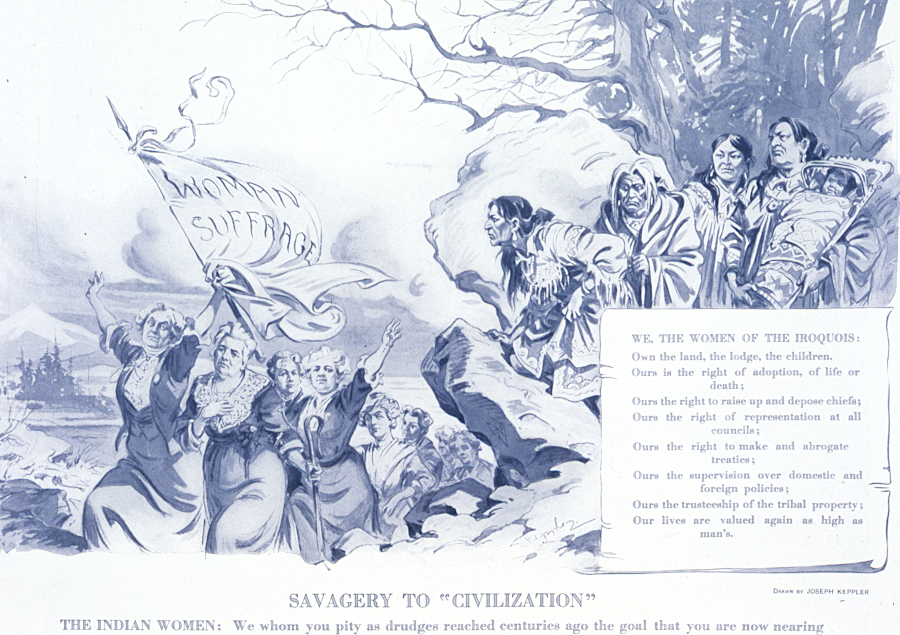

without political power in Virginia, women relied upon various arguments and comparisons to advocate for the right to vote

Source: Library of Congress, Savagery to "civilization" (in Puck magazine, May 16, 1914)

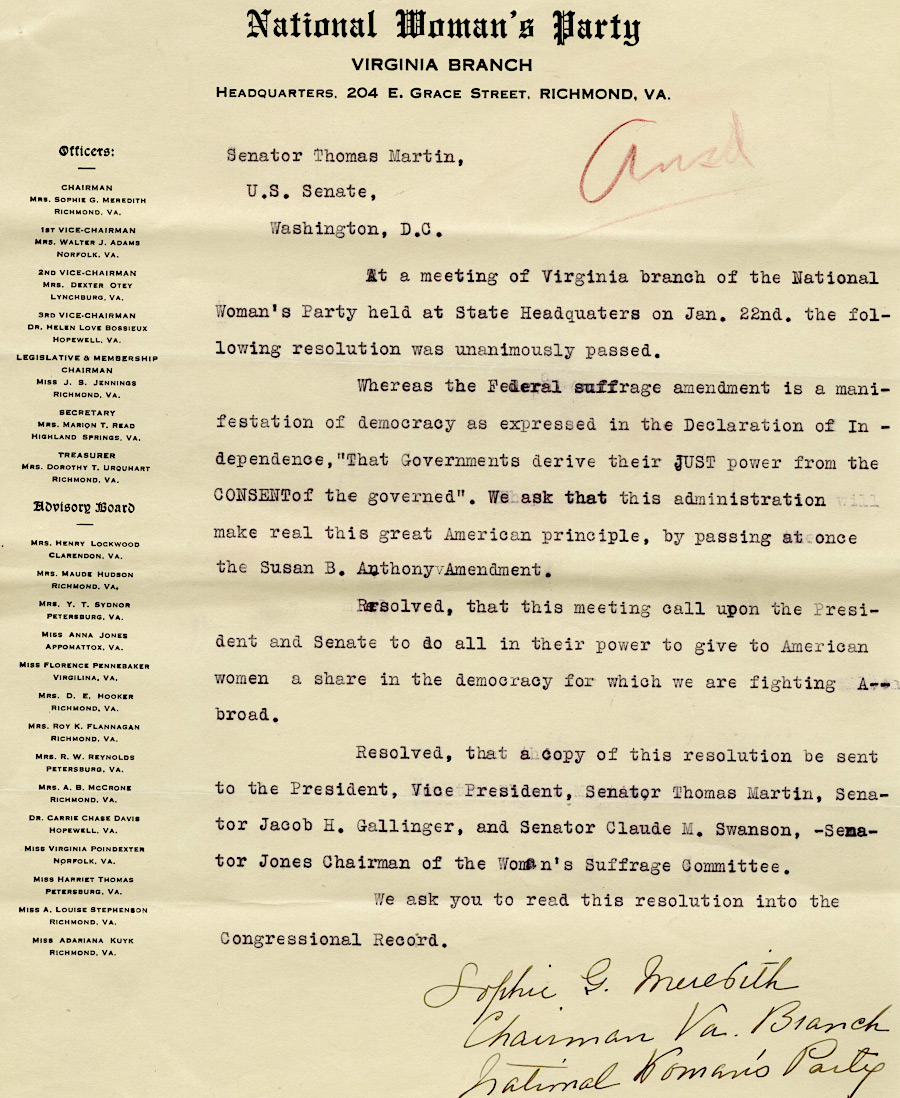

Before Congressional approval of the 19th Amendment on June 4, 1919, Governor Westmoreland Davis had called a special session of the General Assembly to consider a Federal grant for road construction. The National Woman's Party in Virginia pushed for the governor to include ratification in the agenda for the special session, while the Equal Suffrage League recommended waiting until the regular session began in January, 1920.

the June 5, 1919 Richmond Evening Journal reported on the response of the Equal Suffrage League to passage of the "Susan B. Anthony" amendment

Source: Library of Virginia, "Unwarranted, Unnecessary, Undemocratic:" The Virginia General Assembly Responds To The Proposed Nineteenth Amendment In 1919

the National Woman's Party advocated successfully for a vote on ratification in the special 1919 session of the General Assembly - but the legislators rejected the amendment

Source: National Archives, Resolution of the Virginia Branch of the National Woman's Party (1918)

Governor Davis submitted the proposed 19th Amendment to the special session that began in August, 1919 and encouraged the legislators to ratify it. President Woodrow Wilson, who had been born in Staunton, expressed his support as well. The State Senate voted 19-14 against ratification. The House of Delegates vote was more lopsided with 61-21 opposed, then passed a resolution describing the 19th Amendment as:14

The state legislators feared that a substantial expansion of the number of voters would alter the political control enjoyed by the incumbents. To counter the fear that allowing women to vote would lead to "negro rule," the Equal Suffrage League had crafted a standard response:15

white, socially elite women formed the Equal Suffrage League chapter in Richmond

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Libraries Gallery, Equal Suffrage League of Richmond, Va., February 1915

The Equal Suffrage League in Virginia failed in its efforts to get the General Assembly to amend the state constitution in 1912, 1914, and 1916. It also was unable to build a strong-enough coalition of supporters before the opening of the 1920 session of the General Assembly.

in this 1916 rally at the State Capitol, the Equal Suffrage League tried to convince men to allow women to vote

Source: The Valentine, #BallotBattle: Richmond's Social Struggle for Suffrage

Before the vote on ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, opponents circulated a leaflet which associated the national suffragist leaders with a woman of color. Linking voting rights advocates with racial equality was a successful strategy for the opponents of ratification. The 1902 Virginia constitution had restricted the electorate to ensure that white voters would determine who won elections, and all politicians understood that white supremacy was a primary concern of the white voters.

a racist leaflet, circulated before the 1920 General Assembly vote, associated women's rights with racial equality

Source: Library of Virginia, Virginia's General Assembly and the Nineteenth Amendment

despite lobbying of state legislators by the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, the General Assembly rejected a state constitutional amendment in 1912, 1914, and 1916 and ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920

Source: Library of Virginia, "On The List Of Those Who Will Vote For Woman Suffrage": Virginia Women Lobby The General Assembly

The 1920 General Assembly overwhelmingly rejected ratification of the 19th Amendment again in the State Senate, by a vote of 24-16. In the House of Delegates, the vote was still overwhelmingly negative at 62-22.

At the time the Virginia legislature was refusing to grant political rights to women, across the Atlantic Ocean Danville-born Nancy Langhorne was becoming the first woman to serve in Parliament. After women had served in essential jobs during World War I, Parliament passed the Representation of the People and the Parliament (Qualification of Women) acts in 1918. The first act allowed women who were 30 years old and owners of a certain amount of property to vote. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act allowed women to be elected.

Constance Markievicz, an Irish nationalist in prison after the Easter Rising, was elected in 1918. She was the first woman to be chosen by the voters to sit in Parliament. However, she was unwilling to say the required oath of allegiance to the king so she did not take her seat.

Nancy Langhorne's second marriage was to a Member of the House of Commons representing the borough of Plymouth. He became the second Viscount Astor after his father died and was elevated to the House of Lords. Nancy Langhorne Shaw Astor, "Lady Astor," chose to run to replace him. After winning the seat in 1919 she served for 26 years.16

Virginia-born Lady Astor was elected in 1919 and served in the Parliament of the United Kingdom before women in Virginia could vote

Source: The Box, Plymouth, Introduction of Lady Astor as the First Woman MP

In anticipation of ratification, the Virginia General Assembly did pass a "Machinery Bill" in March, 1920. The normal Virginia deadline for voter registration passed before the 19th Amendment became effective with Tennessee's vote. Though the Virginia legislature did not support women's suffrage, it did not create administrative hurdles to interfere with women exercising the new right to vote.

The Machinery Bill modified Virginia's voting procedures so women could pay the required poll taxes, register, and participate in the November, 1920 election. In contrast, Mississippi and Georgia blocked women from voting in 1920 by citing the failure of women to pay the poll taxes which were due in early 1920, months before the amendment was ratified in August 1920.

In the end, the southern state that made the difference in giving women the right to vote was Tennessee. In a dramatic vote on August 18, 1920, the youngest member of the Tennessee legislature chose at the last minute to vote in favor of ratification. Later reports said he changed his mind after receiving a letter from his mother encouraging him to:17

southern states consistently restricted suffrage for women and minorities

Source: Library of Congress, Working Out Her Destiny: Women's History in Virginia, 1600-2004

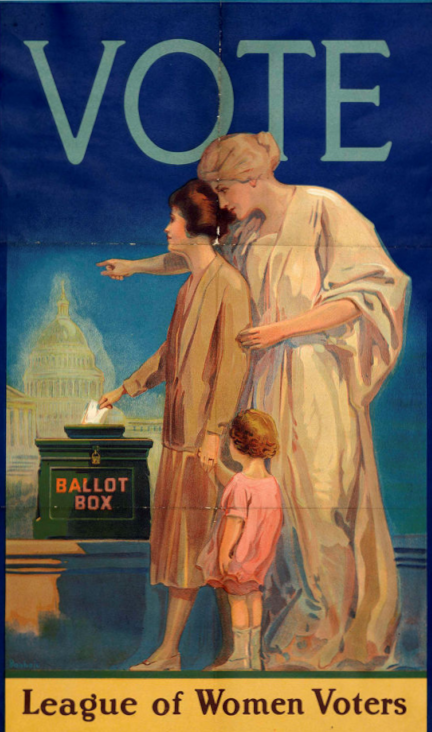

Equal Suffrage League president Lila Meade Valentine immediately began educating women so they could register. Six months before Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1920, Carrie Chapman Catt had formed the League of Women Voters to replace the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Her mission of getting the US Congress to propose the amendment to the states had been accomplished, and she saw ratification on the horizon. Catt took up the next challenge, to get women informed on how to utilize their right to vote.

support from President Wilson increased the potential for passage of the 19th Amendment by the US Congress

Source: Library of Congress, Votes for women bandwagon (by Clifford Kennedy Berryman, January 1918)

The first time Virginia women could vote in an election was in 1920. In the presidential race, the choices were Democratic candidate James M. Cox and Republican candidate Warren G. Harding. There were 10 races for Virginia's seats in the US House of Representatives.

There was also a special US Senate election in 1920, since Thomas S. Martin had died in 2019 before completing his term of office. It was the first time that Virginia voters chose a US senator. The 1918 race came after passage of the 17th Amendment, but Martin had run unopposed.

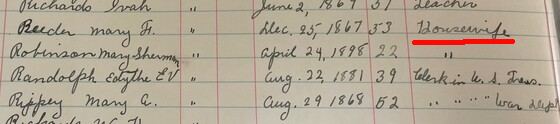

Women had a short time to register between ratification of the 19th Amendment and the 2020 elections. In Fairfax County, the first nine registered on September 11, 1920.

the first women who registered to vote in Fairfax County recorded their occupations, just like the men

Source: Fairfax County Circuit Court Clerk's Office Historic Records Center, Found in the Archives (No. 87, June 2023)

Statewide, perhaps 100,000 women managed to register to vote in the 1920 election.

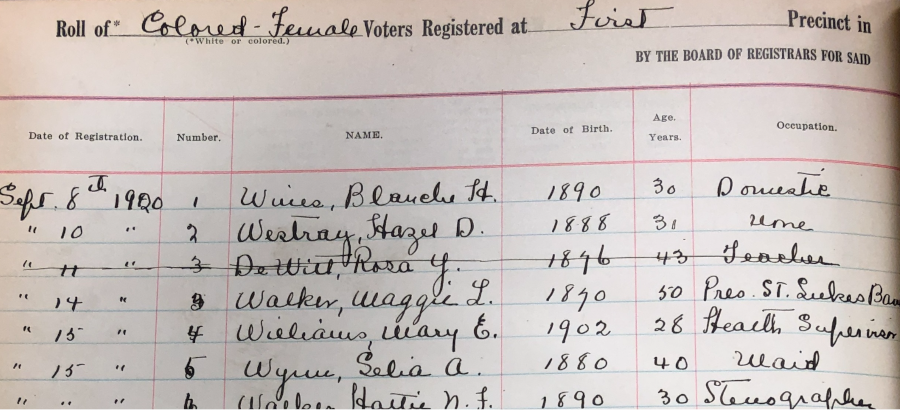

In Richmond alone 10,645 white women and 2,410 black women registered. Maggie Walker and Ora Brown Stokes led the effort in the black community. White officials sought to minimize their success, creating a separate office in the basement and forcing applicants to answer arcane questions in order to quality. White leaders who had previously opposed women's suffrage urged white women to register, to offset the increased number of black voters.

separate registers were created for "Colored-Female" voters before the 1920 election

Source: Library of Virginia, "Really And Truly A Citizen": Virginia Women Register To Vote In 1920

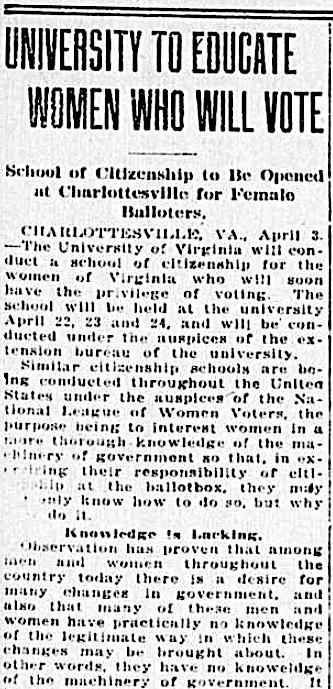

The University of Virginia created a training program to educate women on how to vote, and on the fundamentals of government.

before ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, the University of Virginia launched a program to educate women who might gain the right to vote

Source: Library of Congress - Chronicling America, Richmond Times-Dispatch (April 4, 1920)

As new voters, women had to pay only one year of the poll tax in 1920. The $1.50, which was a significant cost at the time, was paid at the treasurer's office for the city/county. The receipt was required documentation at the registrar's office. When registrars found a way to reject black women, their $1.50 was not refunded.

On November 2, 1920, Virginia gave Democratic candidate James M. Cox 61% of the vote and Republican Warren G. Harding 38%. The remaining 1% was split between Prohibitionist Aaron S. Watkins and Socialist Eugene V. Debs. About 77,000 women in Virginia - less than 10% of eligible women - cast a ballot. Slightly over 30% of eligible men voted that year.

Women stood in line with men until each voter entered the polling booth alone. In Newport News, a white male voter objected to the equal status of all waiting in line. His recommendation was to require two lines, but they would be split by race rather than gender. He recommended white men and women be placed in one line, and black men and women stand together in another separate-but-equal line.18

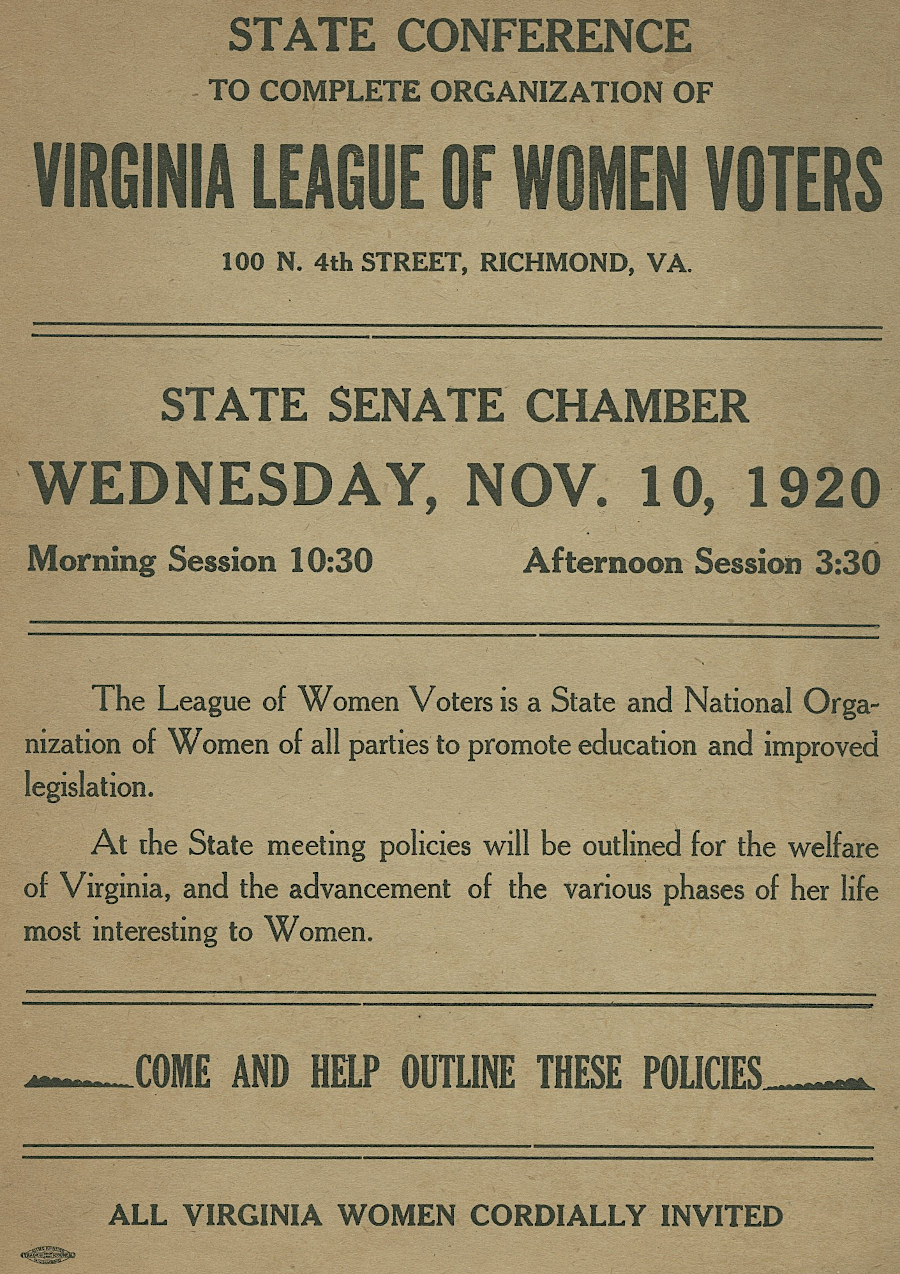

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia met for the last time on November 8, 1920. Two days later, the Virginia League of Women Voters was organized to replace it. The organizational meeting was held in the Senate chamber of the State Capitol. The new Virginia League of Women Voters made clear that it would not be a partisan group, and it was not planning to evolve into:19

the Virginia League of Women Voters replaced the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia in 1920

Source: Library of Virginia, "Banded Together For Civic Betterment": The Virginia League Of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters remains today as a national non-partisan organization focused on registering voters of any gender, providing voters with election information through voter guides, and hosting candidate forums and debates.

In 1920, the new organization was racially exclusive. No black women were allowed to join Virginia chapters until the 1960's. A few black women attended the 1922 convention of the National League of Women Voters. Black suffragists created the separate Negro Women Voters League of Virginia, but it lasted only briefly. The Virginia State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs had a more-lasting existence. As late as 1945, when a chapter of the League of Women Voters (LWV) was organized in Arlington and Alexandria:20

after passage of the 19th Amendment, potential options for women greatly increased

Source: Library of Congress, The sky is now her limit (1920)

the 50th anniversary of passage of the 19th Amendment was commemorated by a 1970 postage stamp

Source: Smithsonian National Postal Museum, Woman Suffrage Issue

In 1928, the state constitution was revised in response to proposals made by Gov. Harry F. Byrd to streamline government operations and make the governor more responsible for managing the Executive Branch agencies. At the same time, "male" was stripped from language regarding suffrage. To make clear Virginia was in compliance with the 19th Amendment, one sentence was added in Article II, Section 19:21

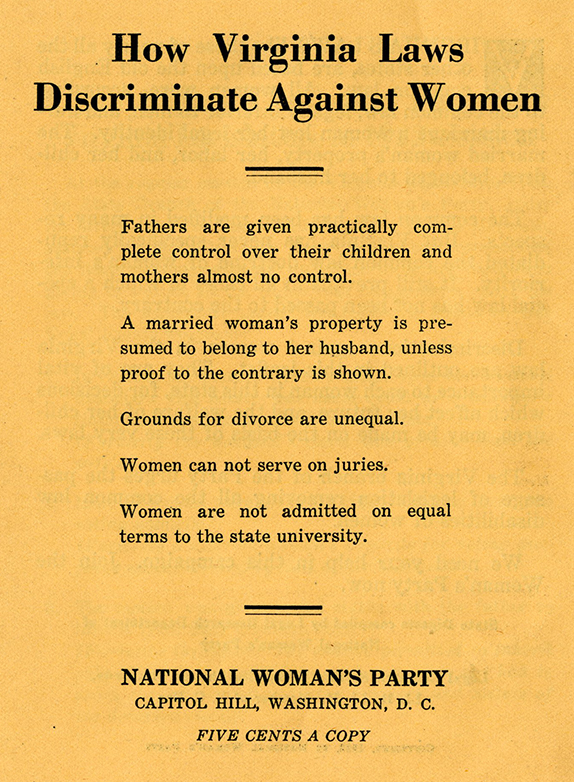

the National Woman's Party highlighted discrimination against women in 1922, after the 19th Amendment was ratified

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University, How Virginia Laws Discriminate Against Women (1922)

After passage of the 19th Amendment, women were finally allowed to practice as lawyers. In 1872, the US Supreme Court had ruled that the equal protection clause in the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution did not prevent states from discriminating and blocking women from being licensed as lawyers.

Until 1896, local judges in Virginia were responsible for licensing new lawyers. When Annie Smith sought a license in 1889 to practice with her husband in Danville, the local judge refused her. The General Assembly considered her appeals, but the State Senate declined to authorize female lawyers in the next two sessions.

In 1894, Belva Lockwood applied. She had become the first woman allowed to argue before the US Supreme Court in 1879, after getting the US Congress to pass legislation authorizing it. She had a practice in the District of Columbia, and sought to break the male monopoly in Virginia. The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals initially rejected her request on a 2-2 vote, then approved her when the missing judge returned and cast his vote in favor. All five judges had been appointed in 1882, when the multi-racial Readjuster Party had control of the General Assembly.

However, the 15-year terms of the judges expired in 1895. When Lockwood returned to the court in 1896, there were five new judges elected by a General Assembly dominated by the conservative Democratic Party. It refused to allow her to plead her case, and the General Assembly revised the laws to specify that lawyers had to be male.

Edward C. Burks, a former judge on the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals an head of the Virginia Bar Association in 1890-91, commented:22

17 years after Belva Lockwood became the first woman to argue cases before the US Supreme Court, the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals refused to admit her to the Virginia bar

Source: Smithsonian Institution, National Portrait Gallery, Belva Ann Lockwood

After the 19th Amendment was ratified, the General Assembly revised the Code of Virginia and authorized women to practice as lawyers. The University of Virginia decided to admit women to its law school and other graduate programs in 1920 (though it would be 50 more years before women were allowed to become "first year" undergraduate students). The first woman to graduate from the University of Virginia law school was Elizabeth Thompkins in 1923. She practiced law in Richmond for nearly five decades.

Rebecca Pearl Lovenstein and Carrie M. Gregory passed the bar exam in 1920, and were the first female lawyers admitted to the Virginia bar. In 1925 Lovenstein, who practiced with her husband, became the first female lawyer to plead a case before the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. By 1930, 28 Virginia women identified themselves in the Census as lawyers. Not until the Code of Virginia was updated in 1950 was the law officially revised to allow "any male person" to serve as a lawyer, and 96% of Virginia lawyers in 1960 were still white men.

The first full-time female law professor started teaching at the University of Virginia in 1968. Not until 1972 did Washington and Lee University admit women into its law school, after Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972 blocked Federal education aid to schools which continued to practice gender discrimination.

The first female Circuit Court judge was Barbara M. Keenan, elected by the General Assembly in 1982. Elizabeth B. Lacy was elected to serve as the first female on the State Corporation Commission in 1985, the same year Mary Sue Terry won election as Virginia's first female Attorney General. The governor chose Judge Lacy for an interim appointment to the Virginia Supreme Court in 1988, and the legislature then elected her to serve a full term.

In 1989, Rebecca Beach Smith was nominated by the president and confirmed by the US Senate to serve on the United States District Court for the Eastern District. She became the first female Federal judge in Virginia.23

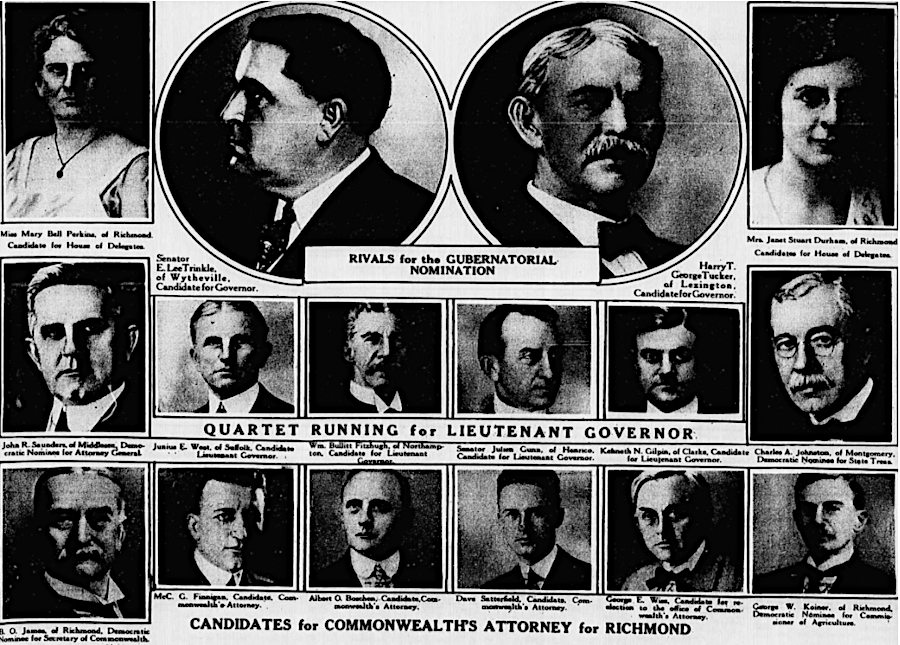

The 19th Amendment allowed women to serve as elected officials, as well as to vote. In 1921, four women ran in the Democratic primaries for nomination for House of Delegates seats. Steteria Olinda Dobyns Trader ran on the Northern Neck, and Eugenie Macon Yancey ran in Bedford County. In the city of Richmond, Mary Bell Perkins and Janet Stuart Oldershaw Durham sought nomination for the five seats from that district.

The Attorney General disqualified Janet Stuart Oldershaw Durham, because she had registered to vote under that name but campaigned as Mrs. James Ware Durham. He also ruled that Steteria Olinda Dobyns Trader could not run on the Northern Neck, because she had voted for a Republican in 1920.

The other two female candidates lost their Democratic primaries in 1921.

two Richmond women ran for the Democratic nomination to the House of Delegates in 1921

Source: Library of Virginia, UnCommonwealth blog, "Her Prospects Of Election": Virginia Women Run For Office

(March 3, 2021)

Women were more successful in getting nominated by the Republican Party. In 1921, Elizabeth Lewis Otey became the first woman in Virginia nominated by a major political party for a statewide office. The Republican Party chose her as its candidate for Superintendent of Public Instruction, an office which at the time was filled by a statewide election. Otey was the niece of Orra Langhorne, who had founded the Virginia Suffrage Movement. In 1921 Virginia was a one-party state, a "Museum of Democracy" in which nomination by the Democratic Party was tantamount to election. In the general election, Otey won less than 30% of the vote.

Five women were nominated by the Republicans for seats in the House of Delegates in 1921. In Arlington County the Republicans chose Mary Morris Lockwood for their House of Delegates candidate. She had picketed the White House while a member of the National Woman's Party. Four other women nominated by the Republicans for seats in the House of Delegates - Nannie Kate Reynolds in Pittsylvania County, Mary Josephine Dickenson Buck in Russell County, and Anne Atkinson Burmeister Chamberlayne in Charlotte County - also were defeated in 1921.

In 1921, the Republican Party excluded blacks from the state convention, endorsed white supremacy, and committed to a "lily white" ticket of candidates. In response, Maud E. Mundin ran on the "lily black" Republican ticket in Richmond. She earned 1,410 votes, more than the four black men on the "lily black" ticket. Her total was about 500 votes less than the white Republican men, and far short of the five Democrats who won with about 12,000 votes each.

For statewide office, the "lily black" Republican ticket included Maggie L. Walker as the candidate for Superintendent of Public Instruction. The "lily white" Republicans had nominated Elizabeth Otey for that same position, so two women competed against each other for Superintendent of Public Instruction. The Democratic Party was the party of white supremacy, so its candidate was destined to win in the general election... and he was a male.

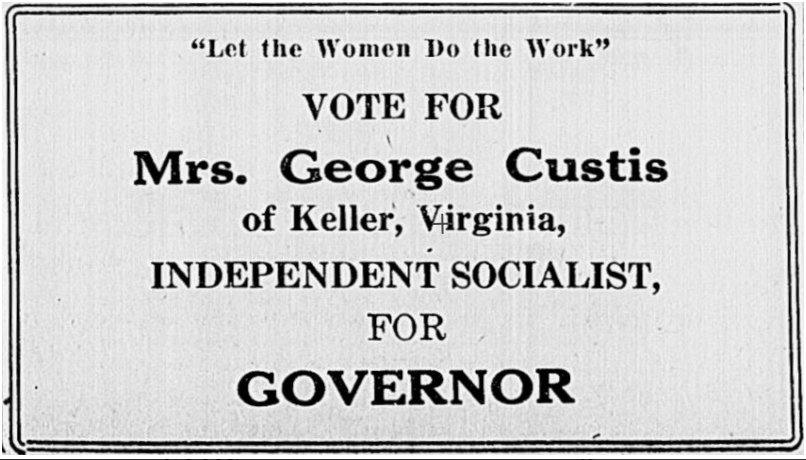

There was also a female candidate for governor in 1921, the first woman to receive votes for that office. Lillie Davis Custis, who called herself Mrs. George Custis, ran a write-in campaign for governor as an Independent Socialist. She campaigned by writing letters to the editor from her home in Keller, Accomack County, to different newspapers. Her first letter was published less than three weeks before the election.

Custis asked voters to "help us purify politics," and called for implementation of the referendum to pass legislation and recall of elected officials. She won 251 of the total 210,866 votes cast for that office. The Democratic Party candidate, Elbert Lee Trinkle, won the race in 2021 with two-thirds of the vote.

Since Lillie Davis Custis was a write-in candidate, Maggie L. Walker was the first "colored" female to get on the ballot for statewide office in Virginia. An entire century passed before the next woman of color qualified for the governor's race. Princess Blanding ran as the nominee of the Liberation Party in 2021.

It was not until 1941 that another woman was on the ballot for the position of governor. Alice Burke was the Communist Party candidate and she won 0.9% of the vote. A third woman, Mary Sue Terry, was the Democratic Party nominee in 1993 but lost that race. In 2025, both the Republicans and the Democrats nominated women. That guaranteed that 250 years after Virginia became an independent state, it would finally have a woman as the top executive.

Voters elected the first two women to the General Assembly in November, 1923. Sarah Odend'hal Fain was chosen in a district in Norfolk, while Helen Timmons Henderson was elected from a district composed of Buchanan and Russell counties. Del. Henderson was the first woman ever to preside over a legislative session in Virginia, when the Speaker stepped down briefly so she could have that honor.

Both women were Democrats. At their 1924 national convention in New York City, Democrats officially considered nominating the first woman for vice-president. Among the 30 candidates, Lena Jones Wade Springs received the fourth highest vote total on the second ballot when Charles Bryan was nominated to run with presidential candidate John Davis. She had a Virginia connection - she had studied at Sullins College in Bristol and the Virginia College for Ladies in Roanoke.

The first Republican woman elected to the General Assembly was Pinkie Giesen, chosen by Radford voters in 1957 and 1959 to serve in the House of Delegates. She lost her race in 1961, as did her son "Pete" Giesen running in Augusta County. Both were "mountain valley" Republicans opposed to the Massive Resistance policies of the Byrd organization. Pete Giesen later won and served as the Minority Leader in the House of Delegates. However, Virginia has never had a mother-son pair serving together in the state legislature - yet.

Del. Helen Henderson was the first female delegate to die in office, after getting ill in 1925. Her daughter, Helen Ruth Henderson, was elected in 1927. The two Hendersons were the first mother-daughter pair elected to any state legislature. (Fathers and then sons serving in the General Assembly were common throughout Virginia's colonial period, and the Slemp family in Southwest Virginia continued the tradition in the second half of the 19th Century.)

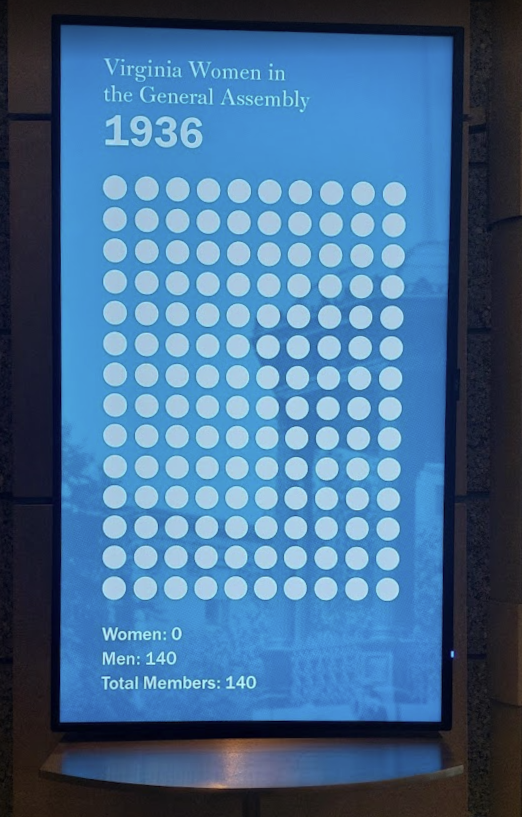

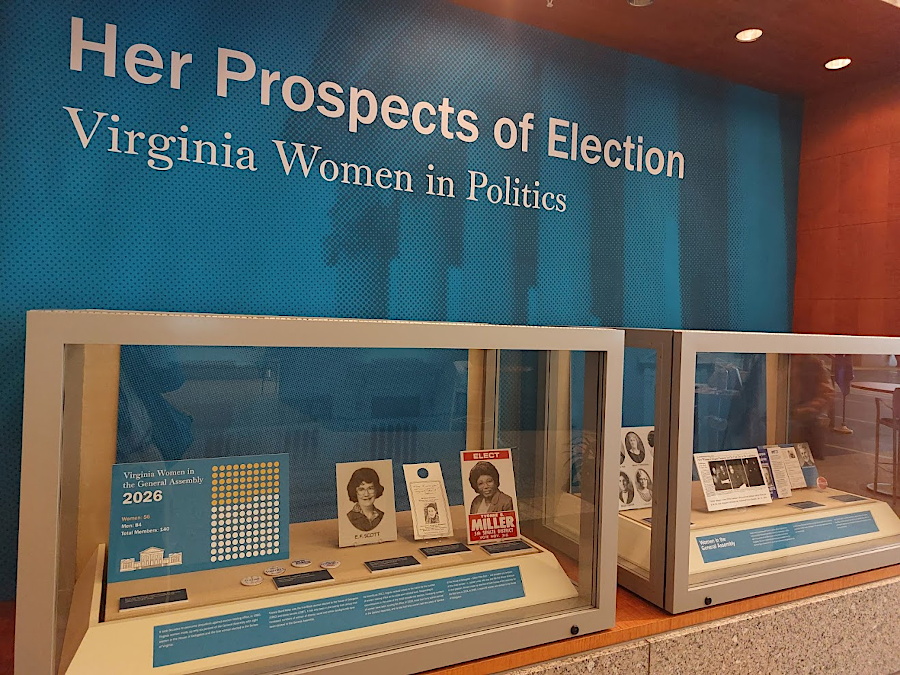

a 2026 Library of Virginia exhibit documented the pattern over the years of women serving as state legislators

In 2023, Virginia established another first when a mother-daughter pair ran simultaneously to represent Southwest Virginia in the General Assembly. The mother sought election in District 47 of the House of Delegates, while the daughter ran for the District 7 seat in the State Senate. The first mother-daughter pair to seek election together in state or Federal races won their Democratic nominations in heavily-Republican districts.

In 2023 a husband and wife team in southeastern Virginia, Karen Jenkins and Clint Jenkins, ran for seats in the Virginia House of Delegates and State Senate for the first time in the history of the Commonwealth of Virginia. In Prince William County that same year, Josh King ran for Sheriff of Prince William County and his wife, Candi King, ran for re-election to the House of Delegates.

Also making history on September 23, 2023 was Haley Van Voorhis. She played as safety in a Division III football game for Shenandoah University in Winchester. That contact role made her the first female, other than a kicker/punter, to play in an NCAA game.

Between 1933-1953, no women were elected to the General Assembly.

Elizabeth Otey was on the statewide ballot again in 1933. She ran for the US Senate as a Socialist. As expected, Democratic Party candidate Harry Byrd won that election.

For 40 years after 1921, no women sought nomination by the Democratic or Republican parties for any statewide office. In 1961, there was a chance that candidates supported by the Byrd Organization for lieutenant governor and attorney general would lose to more-liberal candidates in the Democratic primary. Republicans delayed their nominations, recognizing the potential to nominate pro-segregation conservatives. They might win support from Byrd Democrats more willing to vote for a conservative Republican than a liberal Democrat, and Republicans might win a statewide race for the first time in the 20th Century.

However, the Democrats nominated conservatives and the Republican leadership struggled to find any candidates to run for lieutenant governor and attorney general in 1961. Hazel Barger stepped up and ran for lieutenant governor, campaigning to keep public schools open and accept desegregation as required by the US Supreme Court. She won slightly more than one-third of the total votes, a traditional percentage for Republican Party candidates.

The first black woman elected to the House of Delegates was Yvonne B. Miller in 1983. In 1987, she became the first black woman to be elected to the State Senate. Ghazala Hashmi was the first Muslim woman elected to the General Assembly, when she won a seat in the State Senate in 2019.24

one woman ran for governor in 1921

Source: Library of Virginia, UnCommonwealth blog, "Her Prospects Of Election": Virginia Women Run For Office

(March 3, 2021)

Virginia's General Assembly did not ratify the 19th Amendment until 1952. By that time, women had been voting within the state for 32 years.25

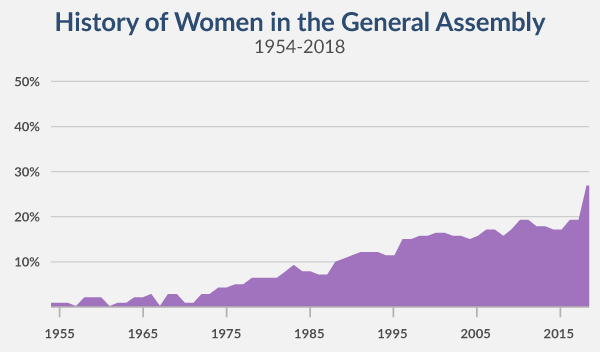

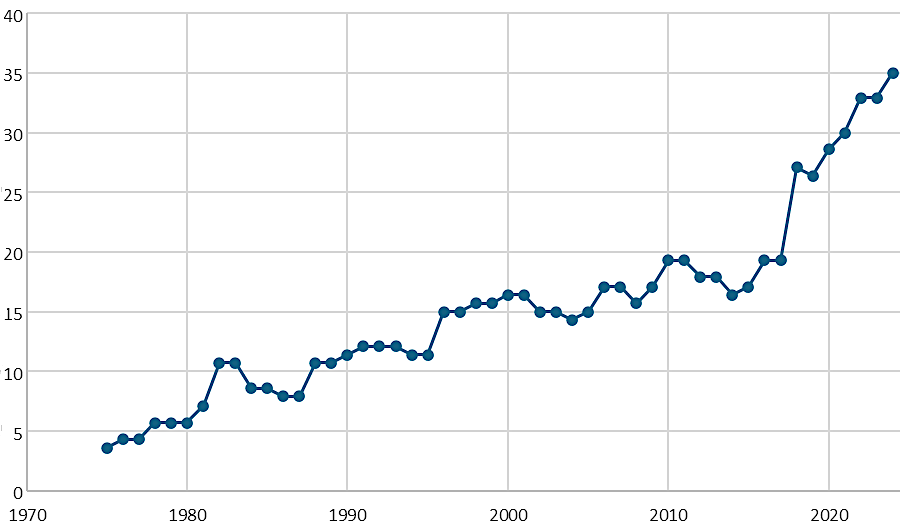

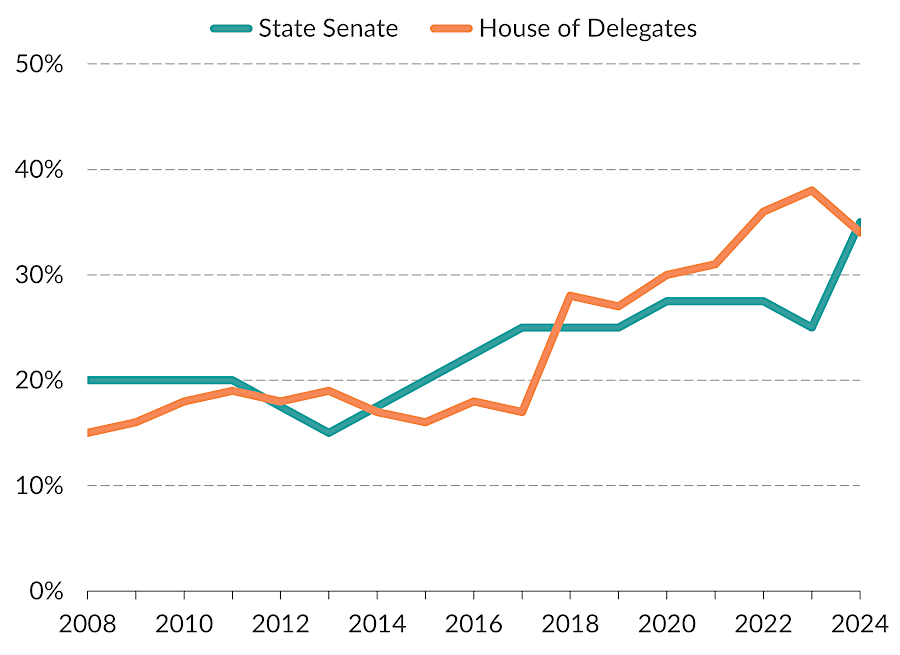

Six women served in the House of Delegates between 1924-1933, with just one serving between 1930-34. There was a gap of 20 years before another woman was elected in 1953. Only one woman was voting on state laws in the House of Delegates in the 1954-56, 1962-64, and 1970-72 sessions.

Not until 1979 was a woman elected to the State Senate. Eva Scott had been elected in 1971 from Amelia County to the House of Delegates. She ran as an independent, at a time when Virginia's political parties were going through a realignment. At the state level, Democrats adopted the more-liberal policies of the national party and moved away from the Byrd Organization's support of racial segregation. Conservatives migrated from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party, encouraged by President Nixon's Southern Strategy.

In 1979, Scott won election to the State Senate as a Republican by defeating the incumbent with 51% of the vote. She did not run for re-election in 1983, since the Democrats who controlled the General Assembly after the 1980 census had redrawn her district boundaries to add more Democratic voters. Her conservative political philosophy and her 1982 vote against ratifying the Equal Rights Amendment was summarized in a short biography by the Library of Virginia, when it honored her as a "Virginia Changemaker:"26

the first woman elected to the State Senate in Virginia voted against ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1982

Source: Library of Virginia, League of Women Voters Poster, 1920

Vivian Watts was elected to the House of Delegates in 1982, becoming the 22nd female to serve in that body. She was the first female member to have children still in school. By 2023, she was longest-serving female member in the legislature.

When she started in 1982, she could not enter the lounge off the House of Delegates floor. She used the cafeteria as a spot to mingle, meet, and conduct business with male legislators.

Legislative receptions were held at the private and exclusive Commonwealth Club. The gentleman's club, which in 2023 still allowed only males to join as full members, required the state legislator to go into its building through a side door.

Watts served in the first House of Delegates to have five female members. She recounted years later:27

Dr. Louise Wensel was the first woman candidate for statewide office with broad support. In 1958, she ran as an independent for the US Senate seat against incumbent Sen. Harry F. Byrd. Organized labor backed her campaign, while segregationists opposed to the US Supreme Court's decisions on school desegregation ensured Byrd's re-election. Wensel finished with just 26% of the vote.28

Hazel K. Barger was the Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor in 1961, and won 34% of the vote. Edythe C. Harrison won the Democratic nomination in 1984 to run in the US Senate race against popular incumbent John Warner; she got 30% of the vote.

One woman has appeared on the Virginia ballot for statewide offices four times. Alice Burke ran for the US Senate in 1940, 1942, and 1946, and for governor in 1941. She was the nominee of the Communist Party, as was her husband when he ran for the US Senate in 1936. Her campaign issues were to improve transportation, abolish the poll tax, raise the minimum wage, and to allow localities to elect school boards. Her support for mine safety legislation gained her and her husband over 5% of the vote from unionized miners in the coal counties in Southwest Virginia.

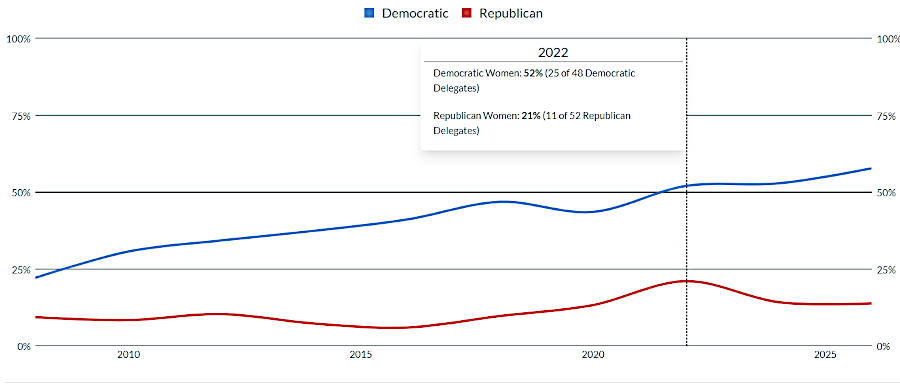

the percentage of women elected to the General Assembly has never matched the percentage in the general population

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Woman in the Virginia General Assembly, Center for American Women and Politics, State Legislature - Numbers and Percentage of Officeholders by Year

Mary Sue Terry was elected as Attorney General in 1985. She was re-elected in 1989, another year in which the Democratic candidates won all three statewide offices. She lead the ticket in 1989, getting 22% more votes than the Democratic candidate for governor. However, she lost her 1993 campaign for governor.

In 1992 Virginia elected its first woman to the US Congress, Rep. Leslie Byrne from the 11th District in Northern Virginia. In 2023, Jennifer McClellan won a special election in the 4th District and became the first black woman elected in Virginia to the US House of Representatives.

In 2005-2006, Judith Jagdmann served as Attorney General, but she had not been elected by the voters. Attorney General Jerry Kilgore had resigned in order to run for governor, and the General Assembly chose Jagdmann as his successor.

Until 2021, Mary Sue Terry was the only woman who had been elected to statewide office in Virginia.

A century after Maggie L. Walker ran on the "lily black" Republican ticket in 1921, both the Republicans and the Democrats nominated a woman of color for the office of Lieutenant Governor. Those nominations guaranteed that a second woman would win a statewide election, and that the first woman of color would be chosen by Virginia voters. Since Princess Blanding was also running for governor in 2021 as nominee of the Liberation Party, there were three women of color on the ballot competing for two of the three statewide offices.

In 2021 the Democratic Party nominated Haya Ayala, a member of the General Assembly who had been endorsed by Governor Northam and the National Organization for Women. The Republican Party selected Winsome Earle-Sears as the candidate for Lieutenant Governor.

Winsome Earle-Sears had been elected to the House of Delegates in 2001, and then chose to make an unsuccessful bid for a seat in the US House of Representatives rather than seek re-election. Sears won the race, defeating Ayala and becoming the second woman and the second person of color to win a statewide election. No woman has ever been elected as a US Senator from Virginia. No woman served in a statewide office between the two Lieutenant Governors, Mary Sue Terry (1990-1994) and Winsome Earle-Sears (2022-2026).

After her 2021 nomination, Winsome Sears commented:29

Mary Sue Terry was elected Attorney General in 1985, when Doug Wilder was elected governor and Don Beyer (far left) as Lieutenant Governor

Source: Library of Virginia, UnCommonwealth blog, Governor L. Douglas Wilder Records Available For Research (April 14, 2021)

After the 2019 elections, 41 of the 140 seats in the General Assembly were occupied by women. That was a record, but still only 29% of the total even though 53% of the registered voters were female.

Sen. Janet Howell became the first woman to serve on the Senate Finance Committee in 1997. She was appointed when the chair, a Republican, and the next Democrat in line both agreed that it was time for a woman to serve on the most influential committee in the State Senate. She became the first woman to chair that committee in 2020.30

Delegate Eileen Filler-Corn became the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House of Delegates in 2020. The House also selected Suzette Denslow as its first female clerk that year, as well as Charniele Herring the first female Majority Leader. The Virginia Mercury began its story on Del. Filler-Corn's historical role with:31

Filler-Corn had been elected to the House of Delegates from the 41st District in 2009. She had sought a leadership position before, but failed in her effort to be chosen as Democratic caucus chair. In January 2019, after the incumbent relinquished his role as Minority Leader, she defeated four other candidates for the job. After Democrats won control of the House of Delegates in November 2019, she was chosen as the Majority Leader. Democrats also won control of the State Senate, and chose Louise Lucas to be the first female Senate President Pro Tempore.

State Senator Adam Ebbin echoed the significance of the election of Del. Eileen Filler-Corn as Speaker of the House:32

the 56th Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates was the first woman, Del. Eileen Filler-Corn

Source: Eileen Filler-Corn for Delegate

After the November 2019 election changed control of the Virginia legislature, it quickly ratified the Equal Rights Amendment. A new milestone was reached after the 2021 primaries - 50 of the Democratic Party's 97 candidates for the House of Delegates were women.33

Republican victories in the 2021 election added five more women to the Republican caucus. The 11 women increased the percentage of Republican members of the House of Delegates to 21%. The Democrats lost seven seats, six of them occupied by men. In 2022, there were 23 men and 25 women in the Democratic caucus. For the first time in history, over 50% of a political party's caucus in the House of Delegates was female.34

in 2022, for the first time women constituted over 50% of a political party's caucus in the House of Delegates

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Women in the House of Delegates

In 2022, control of the Lynchburg City Council switched to the Republican Party for the first time in decades. However, the Republican-controlled city council repeated something that the Democratic-controlled city council had done in the last three elections and chose a woman to be mayor.

Two of the Republicans joined with the two Democrats to elect the new mayor in a 4-3 vote. Her selection reflected dissention among the 5-2 Republican majority, and gender was not a relevant factor in the decision.35

After the 2020 Census, the Supreme Court of Virginia adopted a new map redistricting the boundaries of 100 House of Delegates districts and 40 State Senate districts. The court chose to ignore the residences of the incumbent legislators. The new map created open seats and placed multiple incumbents within the same district, triggering a higher-than-average number of resignations and primary losses by incumbents in 2023.

The opportunities resulting from the redistricting incentivized new candidates to run in 2023 for the General Assembly. In the end, 34 women were elected to the 100-member House of Delegates and 14 women were elected to the 40-member State Senate. A male member of the State Senate resigned after the election, and a 15th woman was then elected to that body in January 2024. For the first time in history, women composed at least 1/3 of both chambers.

Prior to the 2023 General Election Jeff Schapiro, columnist for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, noted:36

women composed at least 1/3 of both chambers in the 2024 General Assembly

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), Percent of Women in the General Assembly

Del. Danica Roem became the first transgender person to serve in the Virginia House of Delegates, after being elected in 2017. She describes herself as the first "out-and-seated" trans member of a state legislature. Back in 2012, Stacie Laughton became the first transgendered person elected to a state legislature when she won a race in New Hampshire. Laughton resigned before taking office after it was revealed that a previous felony conviction made her ineligible to be seated.

Roem emphasized throughout her 2017 and subsequent campaigns that she was the best candidate based on her experience and policy positions; her presentation as a female should not be the basis for voting for or against her. After being elected to the State Senate in 2023, Roem became the first transgender person to serve in both houses of a state legislature.

Danica Roem was easily recognized by her rainbow headband when campaigning in 2017

Source: Wikipedia, Danica Roem (photo by Ted Eytan)

Sen. Louise Lucas, who became chair of the powerful Finance Committee, noted that when she had first arrived in 1992 there was no women's restroom for female senators. At that time, the dress code banned pantsuits.

In the 2024 General Assembly, the majority of the Democrats in the Senate Democratic Caucus (11 of 21) were female. Sen. Lucas said in 2024:37

next to the State Capitol, seven bronze statues of women now stand at the Virginia Women's Monument, Voices from the Garden

On August 25, 2023, the only woman ever awarded the Medal of Honor had a Virginia military base renamed in her honor. Fort A.P. Hill was renamed to honor Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, a surgeon in the Civil War. The US Congress had mandated that Department of Defense eliminate the commemoration of Confederates at military bases.

Fort Walker in Caroline County became the first US military base named solely for a woman. Earlier in 2023, Fort Lee had been renamed Fort Gregg-Adams. That honored Lt. Col. Charity Adams, the first black woman commissioned into the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps.38

In 2025, women filled 49 out of 140 seats in the General Assembly. By then, 123 women had been elected to the House of Delegates or State Senate, compared to 9,500 men since 1619. Delegate Adele McClure was attending sessions after having given birth in October, and pumped breast milk in the Capitol during the day for her daughter. Delegate Destiny LeVere Bolling went to a hospital during the session to deliver her daughter. House Speaker Don Scott granted her permission to vote by proxy while recovering, the first time that childbirth had ever been used to justify a remote vote.

Delegate Scott said:39

Also in 2025, the Democratic and Republican parties both nominated women for governor. Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears won the Republican nomination, while former US Representative Abigail Spanberger was chosen by the Democratic Party.

in 2025, the two major party candidates debating their qualifications for governor were women

Source: WFXR, Virginia Gubernatorial Debate (October 9, 2025)

The Republican ticket was the most diverse in the party's history. The candidate for governor was a black woman. John Reid, candidate for Lieutenant Governor, was the first openly gay candidate nominated by a major party for statewide office. The Republican candidate for Attorney General was a Latino man seeking re-election. Of the six candidates for statewide office in 2025, for the first time in history there were three women - and no straight white male on the ticket.

Two of the candidates were first generation immigrants born outside the United States. Winsome Earle-Sears was born in Jamaica. The Democratic nominee for Lieutenant Governor, State Senator Ghazala Hashmi, was born in India. She also became the first Muslim nominated by a major party for statewide office.40

Democrate Abigail Spanberger won the race for governor, as did her two running mates for statewide office. Ghazala Hashmi became the first woman elected to serve as Lieutenant Governor. Jay Jones won the Attorney General race and his opponent was also a male, so it had been guaranteed after the nominations that one female and one male would win statewide office on November 4, 2025.

Virginia voters made history by electing the first female governor in 2025

Source: Richmond Times-Dispatch (Movember 5, 2025)

Voters elected 42 women to the 100-member House of Delegates, the highest percentage ever. Of the total, 37 were Democrats and five were Republicans. After the 2025 elections, there were more Democratic women that all of the Republicans (36) in the House of Delegates. In the State Senate, 11% of the elected officials were female. One of those 40 seats would be vacated because State Senator Ghazala Hashmi had been elected to serve as Lieutenant Governor.

Spanberger noted in her victory speech that her husband had told their their daughters something that had never been said before:41

When the new governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general were inaugurated on January 17, 2026, for the very first time none of the three was a white male. It was the first time an incoming governor wore a pantsuit (suffragette white) to the inauguration. The same was true when the governor gave her first speech to the General Assembly, flanked by the Speaker of the House and the president pro tem of the Senate.42

Alice Paul and the National American Woman Suffrage Association organized a major parade on Pennsylvania Avenue a day before Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated in 1913

Source: National Archives, Woman Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC (March 3, 1913)

Governor Abigail Spanberger speaking at her 2026 inauguration

Source: Virginia Public Media, 2026 Virginia Inauguration (January 17 2026)

poster advocating for women's suffrage

Source: Library of Congress, Votes for women (c.1913)

harsh treatment of suffragists at the Occoquan Workhouse increased public attention and support for their cause

Source: Library of Congress, Miss [Lucy] Burns in Occoquan Workhouse, Washington (November 1917)

the Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage sought to conflate socialism with suffrage

Source: Library of Virginia, Anti-Suffrage Arguments (c.1910)

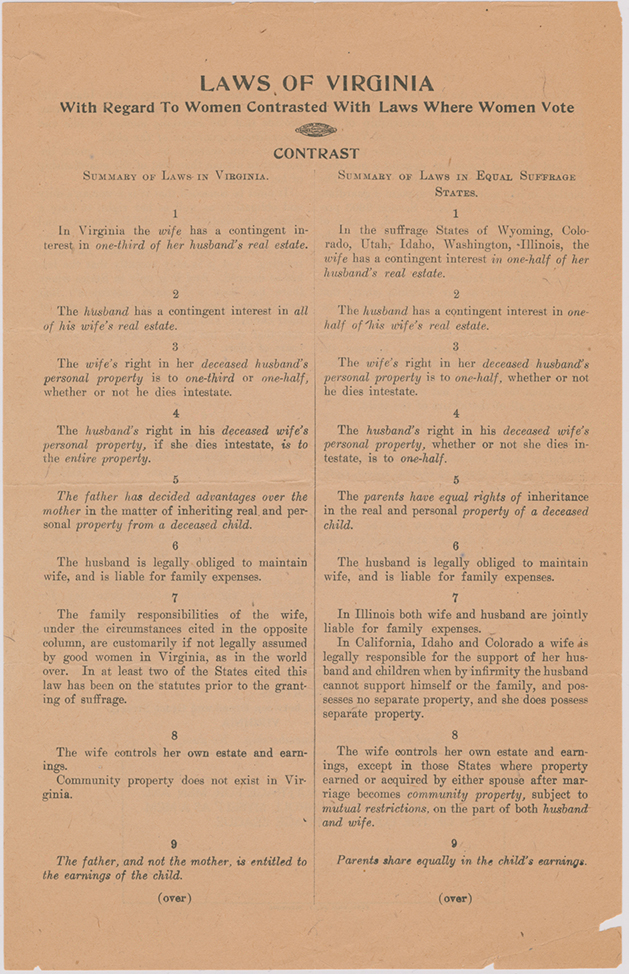

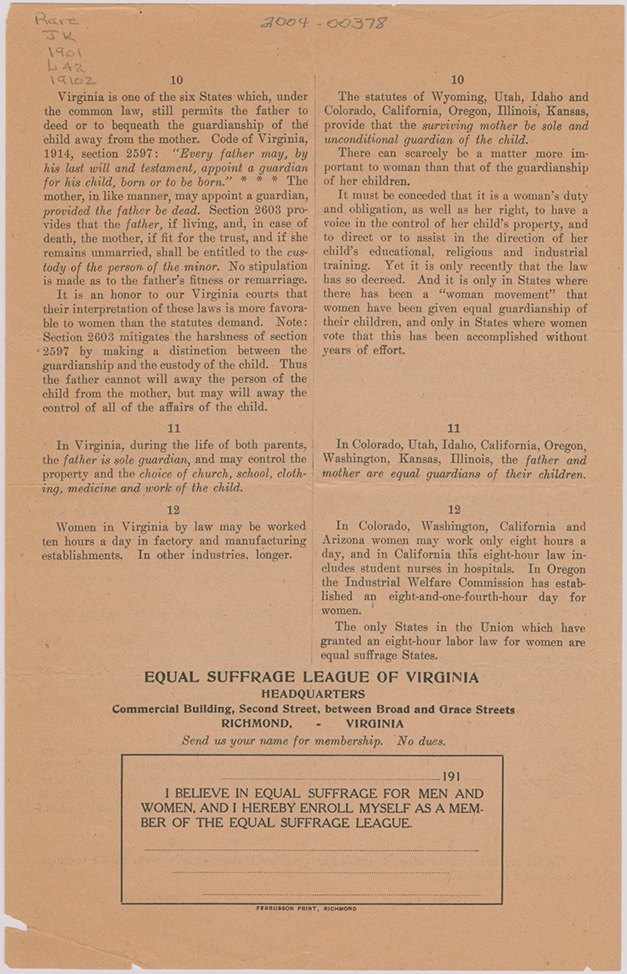

the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia detailed the advantages of women's suffrage in Virginia

Source: Virginia Commonwealth University, Laws of Virginia with Regard to Women Contrasted with Laws Where Women Vote