after 1670, men had to control enough land to pay local properry taxes if they wanted to vote

Source: Fine Art America, Tobacco Plantation

after 1670, men had to control enough land to pay local properry taxes if they wanted to vote

Source: Fine Art America, Tobacco Plantation

When voting began in the colonial period with elections to the first General Assembly in 1619, adult white men who were not working as an indentured servant could vote. That was a limited pool of voters, but it included more than those who owned land. As servants conpleted their term of indenture, they received their "freedom dues" (some clothing and food) and gained the right to move to a new place, negotiate the price for their labor, and accumulted enough assets or credit to purchase land.

Former servants also acquired the right to vote for burgesses to serve in the General Assembly and for the initial members of the vestry when a Church of England parish was created by the General Assembly. Cultural pressure rather than defined property requirements may have limited who chose to vote until 1646, when the General Assembly passed a law making it clear that every free white adult male had the right to vote.1

Starting in the 1630's, a few families began to establish large landholdings and become the dominant political force in different counties. The large numbers of indentured servants who gained their freedom struggled to grow enough tobacco to acquire parcels of land. England shipped convicts to provide labor and empty the jails, and those who survived their term of service also became free men.

As Virginia became a colony with concentrated wealth and great income inequality, the emerging landowning gentry feared the potential in the mid-1600's that former indentured servants without land would become the majority of the colony's population. If every free white adult male had the right to vote, then the majority could elect people to the House of Burgesses who would impose high taxes on property and "soak the rich."

Wealth was tied to farming. Production of tobacco was tied to control of land, and tobacco farming was labor-intensive. To grow enough tobacco to make a significant profit required having control over enough indentured servants/slaves to plant, weed, harvest, pack, and transport the tobacco. The process started with having legal rights to plant land.

Grants of land were controlled by the governor, his Council, and favored members of the House of Burgesses. To preserve their wealth and status, the few families who gained control over land desired a system where a large number of poor, landless freemen in a county could *not* control the vote. Those who had control of land would control the political process, and control taxes on property.

During the English Civil War in 1655, when Governor Berkeley had been deposed and the General Assembly was electing governors, the colonial legislature passed a law restricting the right to vote to those who were "householders." As more women immigrated into the colony and the gender ratios became more balanced, families living in separate structures became a more significant percentage of the population. The law limited the franchise. Former indentured servants living in someone else's house lost the right to vote; only the householder himself could participate in elections.

That restriction of the electorate lasted only one year. In 1656, the General Assembly again authorized all freemen to vote.

In 1670, Governor William Berkeley got the colonial legislature to restrict the right to vote to white males who owned enough property to pay local taxes. Farmers with a lease for land that was extended out enough years to require paying property taxes also qualified.

Allowing leaseholders to vote was appproved because a significant number of tobacco growers east of the Fall Line were not landowners. That loosened the control of the gentry, who owned such a high percentage of land in Tidewater. Land stayed within the families, transferred to subsequent generations through entail and primogeniture. Once acquired by the gentry, Much of the land transferred to the oldest son without ever coming onto the market to be sold.

The 1670 requirement that a man must own enough property to pay local taxes was a mass disfranchisement; the right to vote was withdrawn from a major percentage of the male population. Governor Berkeley had not dissolved the General Assembly since the 1661 election. There were few elections in the 1660's, and the new restriction had limited impact initially. The new limits on voting were applied first in elections after an elected burgess died or resigned.

The governor's objective was to exclude from voting those freemen who had completed their term of indenture, but had not acquired land to start their own farm. Berkeley assumed that only those with property should have a voice in government. He claimed that those former indentured servants, excluded by his new restrictions on the electorate, had little investment to protect by good governance. Instead, they showed:2

Governor Berkeley was a royalist with a strong personal desire to increase his own wealth and status. He was conscious of being in the upper class and was not motivated by republican principles. His priorities were to maintain a stable society that steered wealth to an elite few, rather than the principles in the American Revolution to broaden the democratic process and provide more-equal opportunity. Gov. Berkeley's restrictions on the electorate in 1670 blocked the ability of poor farmers to elect burgesses who might oppose Berkeley's initiatives, and the only avenue left for the poor farmers to "change the system" was violence. It took only six year for that to occur.

There is a counter-argument that setting a threshold of property ownership, before allowing someone to vote, could have increased rather than decreased the quality of governmet and a focus on doing "public good" in the mid-1600's.

At the time, indentured servants who served their time often stayed with their former owner. They farmed for wages, or a percentage of the crop, until acquiring enough assets to move to the edge of settlement and finally purchase land there.

Those landless farmers, just like the indentured servants and the slaves, were dependent upon the landowner. The voting process was public; there was no secret ballot in colonial Virginia elections. If men without property could vote, then the dominant landowner might reward/punish them based on how they announced their decisions.

Freemen who owned land were more independent, financially, from the gentry. A minimum property threshold to vote limited the ability of a landowner to control a block of votes, by excluding primarily people forced to vote as directed by the dominant landowner. Establishing a property requirement before allowing a white male to vote certainly excluded the poor and thus limited who could participate in the decision process, but the property requirement also could have restrained oligarchy control.

Acccording to one school of thought, the minimum property requirement could have enhanced the democratic process. Restricting the electorate reduced the ability of a few powerful men in some counties to dominate elections for the House of Burgesses, by excluding dependent voters from the electorate.

Governor Berkeley chose to restrict the franchise when the frustrations of the poor white males were growing. High taxes approved by the General Assembly after 1660 were perceived as being wasted. Those taxes subsidized the already-wealthy gentry that the governor appointed to various offices. The appointees gained an additional salary for each office and the governor gained political support in the House of Burgesses and his Council from the emerging "First Families of Virginia," but the taxpayers saw no benefits.

Perhaps most significantly, the ability for the former servants to acquire land in 1670 was difficult. Settlers who moved into the backcountry along the Fall Line and north of the Rappahannock River felt threatened by the bands of Native American hunters.

Instead of forcing Native American groups to leave their land so new farmers could occupy it, the governor negotiated deals with Native Americans for trading furs. Settlers sensed that frontier security was secondary to keeping the peace despite raids by Native Americans, so the governor could get even richer from the fur trade.

In response, the General Assembly funded construction of forts for protection. The backcountry settlers saw fixed fortifications as useless for military purposes. There was resentment that the contracts to build the forts served primarily to give the genry another financial subsidy, at the expense of the small farmers paying the taxes.

Governor Berkeley attempted to generate popular support by calling an election in 1676 for a new House of Burgesses. It was the first time he had dissolved the General Assembly and allowed every county to elect new burgesses since 1661. The election was intended to re-establish the legitimacy of the colonial government, and the governor dropped the property requirement for voting that he had imposed in 1670 so all free white adult males could vote.

Holding an election with a broadened franchise was not a sufficient response to offset the built-up frustrations. A few opportunistic members of the gentry, including William Byrd II, organized disgruntled groups and Virginia experienced its first civil war in 1676. An "army" led by Nathaniel Bacon raided and looted homes of the wealthy, burned Jamestown, and forced the governor to flee to the Eastern Shore.

Bacon's Rebellion ended soon after Nathaniel Bacon died from disease. Troops from England arrived, Governor Berkeley was recalled, and commisioners sent by King Charles II restored order.

The king sent instructions to void many of the laws passed by the 1676 meeting of the General Assembly, which had been pressured by Bacon's rebels to rebalance opportunities to gain and retain wealth across class lines. One law passed by those burgesses had eliminated the minimum property requirement for voting. However, King Charles II specifically directed that a property requirement be adopted for future elections to the House of Burgesses.

It took eight years for the General Assembly to formally comply. In 1684, it finally passed a law to restrict the franchise as directed by the king.3

The threshold of minimum property required to vote was altered, but not eliminated, for another 175 years after Bacon's Rebellon. The discrimination against the poor continued even after the American Revolution.

The Fifth Virginia Convention that adopted the first state constitution in 1776 simply maintained the existing rights to vote. The leaders who declared independence from Great Britain did not expand the electorate when converting the colony into an independent state, and did not increase the ability of the poor to participate in the democratic process of voting. "Liberty and justice for all" was not their motto in 1776 - women, blacks, and the poor were excluded from participating in elections.4

Virginia's first constitution, adopted in 1776, ended British authority and reshaped the structure of government - but did not alter who had the right to vote

Source: Library of Virginia, First Virginia Constitution, June 29, 1776

The property requirement exacerbated sectional tensions in the 1800's. The population patterns in Virginia changed substantially, but the boundaries of the 24 electoral districts created for election of State Senators were not updated after 1792. As a result, the Tidewater retained political power that exceeded its percentage of the population.

The property requirement discriminated against the small farmers, many of who lived west of the Blue Ridge. One third of the white men living in Virginia could not vote.5

If they gained control of the General Assembly, they could raise property taxes on slaves. Since slaves were concentrated east of the Blue Ridge, such a tax increase would impact the Tidewater and Piedmont disproportionally.

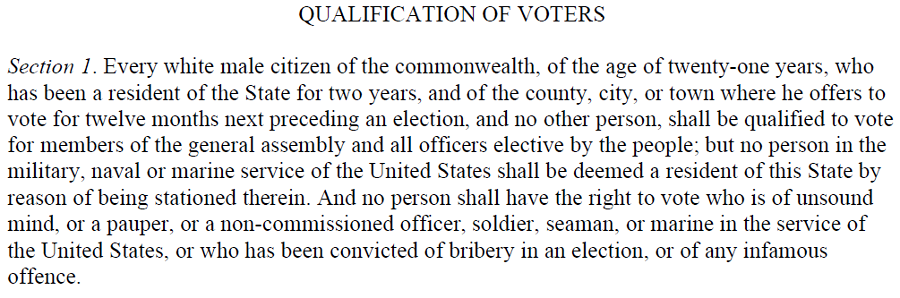

During the 1829 constitutional convention, representatives elected from east of the Blue Ridge retained political control. They blocked reapportionment of the electoral districts, and maintained a property requirement for voters. A detailed description was added to clarify what was considered suffcient control of property worth $25, to determine if a "white male citizen of the Commonwealth, resident therein, aged twentyone years and upwards" also met the minimum established for voting.6

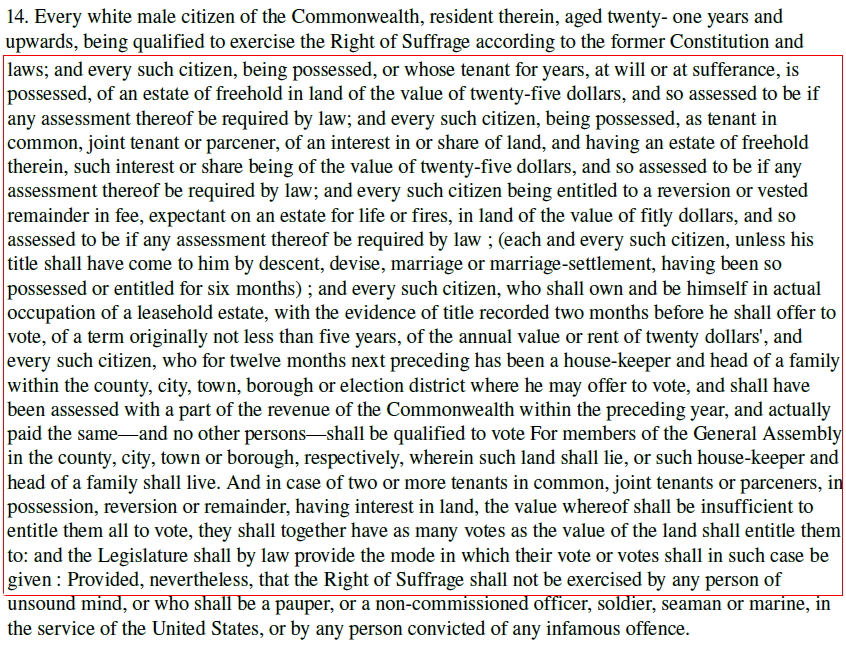

By 1849, continued population growth in the west again forced the eastern leaders to authorize a convention to prepare Virginia's third constitution. The property requirement first established in 1670 was finally dropped completely in the constitution which was approved by voters in 1850 and went in effect starting in 1851.

Virginia's 1850 constitution dropped the requirement that voters had to own $25 worth of property

Source: For Virginians - Government Matters, Virginia Constitution, 1851

Virginia's 1830 constitution defined how to calculate if a voter owned $25 worth of property

Source: For Virginians - Government Matters, Virginia Constitution, 1830