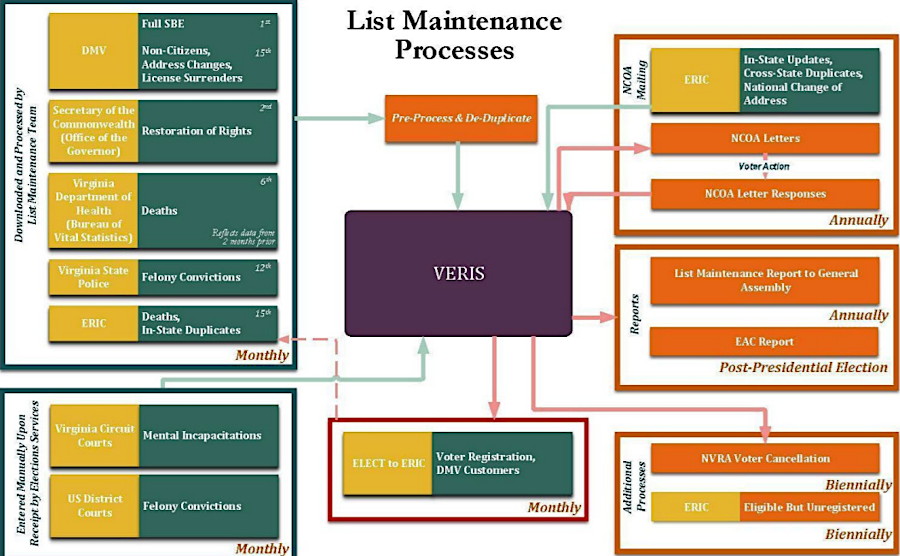

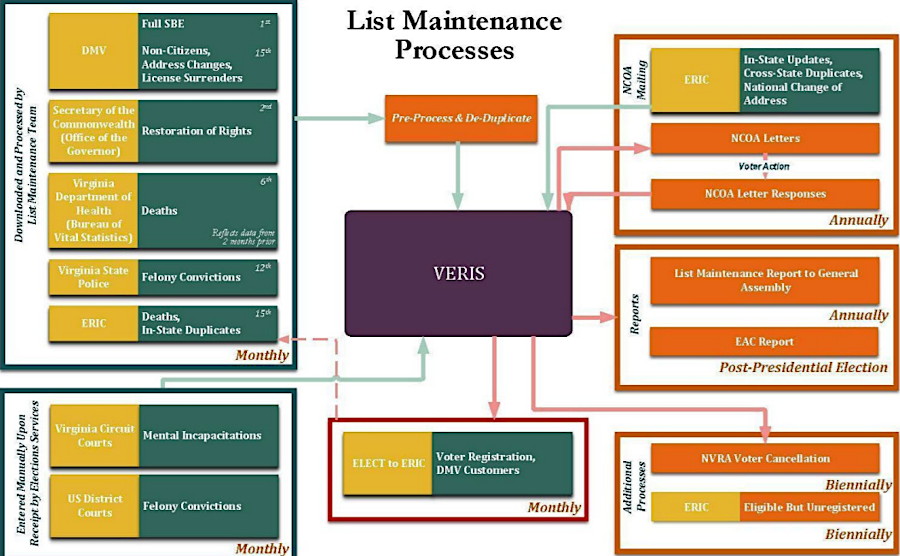

the Virginia Department of Elections updates its centralized VERIS database monthly

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Annual List Maintenance Report, September 1, 2020 - August 31, 2021 (Appendix A, p.10)

the Virginia Department of Elections updates its centralized VERIS database monthly

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Annual List Maintenance Report, September 1, 2020 - August 31, 2021 (Appendix A, p.10)

The enfranchisement of colonists started with white males who owned property. In colonial Virginia's very first legislature in 1619, two representatives were not seated because the "private plantation" which had elected them were judged to be unqualified to vote.

Those two delegates were sent from the plantation of Capt. John Martin. His patent stated that he was not subject to the colony's new general government, so the General Assembly determined that he was not entitled to send representatives to make laws for the general government.

During the colonial period, the sheriff documented who voted in a poll book. The list of voters was prepared as they appeared at the county courthouse and spoke out the name of their preferred candidate. The viva voce process enabled everyone to observe who voted, and for whom they voted. The poll books documented the results in case an election was contested, rather than identified the eligible voters in advance of an election.

After passage of the 1902 state constitution, local officials excluded black men from the polls primarily by preventing them from registering. In 1920, anticipating passage of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution, women were registered quickly so they could vote that year. Black women faced the same barriers to registration as black men.

Various Federal laws and court decisions in the 1960's lowered the barriers. Ratification of the 24th Amendment to the US Constitution blocked use of a poll tax to limit voting in Federal elections. Ratification in 1971 of the 26th Amendment enabled 18 year olds to vote.

The League of Women Voters led efforts to facilitate registration of new voters, especially 18 year olds, but potential voters still had to navigate a registration process that was not designed to be simple. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the General Assembly made major changes to the requirements for registering and voting. The legislature authorized same day registration, made it a default option for transactions at the Department of Motor Vehicles to trigger registration, and allowed people 16 years of age to pre-register for voting once they turn 18.

"No excuse" absentee voting was allowed, along with in-person absentee voting on Sundays and drop-off locations and satellite offices for delivering absentee ballots. People were allowed to vote absentee, in person, up to 45 days prior to a general election. The requirements for personal identification were relaxed. The requirement for a photo ID was eliminated, and people without an approved form of identification were still allowed to vote after signing a legally-enforceable statement that they were the registered voter.

Between 2019-2022, the percentage of the eligible population in Virginia registered to vote increased from 84% to 90%. In the 2022 election, nearly 1/3 of the voters cast absentee ballots or voted early before election day.1

Local registrars, not the Virginia Department of Elections, have the responsibility to maintain the list of registered voters for a particular jurisdiction. At the state level, the Virginia Department of Elections maintains a centralized database of voters, the Voter and Election Registration Information System (VERIS). The day before the November 2021 election, the state agency had 5,951,353 registered voters in the database.

The Virginia Department of Elections provides information to the local registrars so they can remove ineligible voters from the rolls, and submits an Annual List Maintenance Report to the Privileges and Elections committees in the House of Delegates and State Senate.

The updating process includes annual address match with the United States Postal Service's National Change of Address (NCOA) system to identify when a voter has moved. A forwardable letter with a postage prepaid envelope is sent to voters who have requested a change of address, requesting confirmation that they are still eligible to vote in Virginia or if they wish to cancel their voter registration.

Voters who did not respond to the notice within 30 days or whose confirmation mailing was returned as undeliverable were classified as "Inactive" on the voter registration file. Inactive voters could still cast a ballot, unless they did not vote over the time period of two federal general elections (2 to 4 years). Non-voters were then removed from the voter rolls and would have to re-register in order to vote.2

Virginia was a member of the Electronic Registration Information Center ("ERIC"), a multi-state partnership for voter file list maintenance, between 2012-2023. Virginia joined in 2012 as one of the original seven members. The nonpartisan organization grew to include 33 members.

When a new resident registered to vote in another member state and reported that they have moved from Virginia, the Virginia Department of Elections was notified so their name could be removed from the poll book in a Virginia jurisdiction. In 2022, the Electronic Registration Information Center identified 65,000 deceased voters, 2.4 million people who had moved between participating states, and 7.3 million people who moved within those states.

After Donald Trump lost the 2020 election, however, Republican election deniers falsely claimed the organization facilitated fraud and shared data with third parties for partisan purposes. In 2023, Virginia became the eighth state to withdraw from the Electronic Registration Information Center. The withdrawal notice from the Virginia Elections Commissioner, appointed by Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin, was sent less than a year after the Republican Attorney General had defended the Electronic Registration Information Center as a valuable tool for protecting election integrity.

Later in 2023, Virginia signed individual data-sharing agreements with five other states and Washington, D.C. That was obviously fewer states than had exchanged data previously using the Electronic Registration Information Center, and did not include North Carolina or Maryland.

A new Voter Election Registration Information System was scheduled for implementation in 2025. In 2024, Governor Youngkin issued Executive Order 31. It required the Department of Elections to update data sharing agreements and standardize data with the Department of Health, the Department of Motor Vehicles, and the Virginia State Police and to exchange registered voter lists with all states bordering Virgnia.3

Belonging to the Electronic Registration Information Center was only on way to maintain accurate voter rolls. Virginia verifies potentally ineligible voters and updates the voter list by mailing letters to voters who appear to have moved out of state or after repeated failure to vote in Virginia. Based on the response, or lack of response, voters can be removed from their local poll list:4

Another mailing effort to identify voters who had moved resulted in 260,653 voters being placed in "inactive" status in 2023. Those voters would be eligible to vote, but if they did not do so in the next four years they would be removed from the rolls. Those removed from the rolls would have to re-register.

Clerks of the Circuit Courts notify the Virginia Department of Elections of all individuals who were adjudicated mentally incapacitated. Between September 2020-August 2021, registrations for 589 voters were cancelled by general registrars who were notified of such determinations. The Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) sends a list to the Virginia Department of Elections of all individuals who obtained a drivers licenses and also responded "No" when asked if they were a citizen. Between September 2020-August 2021, voter registration was cancelled for 1,302 people who had registered to vote but who had also declared themselves to be non-citizens.

Voters who die are deleted from the voter rolls. Families rarely notify local general registrars, but the Virginia Department of Elections uses multiple methods to identify deceased voters. The centralized database of voters is matched regularly against the list of deceased persons maintained by the Social Security Administration, a monthly report from the Bureau of Vital Statistics of the Virginia Department of Health, and (until 2023) reports from the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC).

Between September 1, 2020 - August 31, 2021, Virginia cancelled registrations for 55,340 deceased voters. Another special effort to research death records back to 1960 led to cancellation of the registrations of another 77,348 dead voters between September 1, 2022 - August 31, 2023.

If a person is convicted of a felony, they automatically lose the right to vote in Virginia. The Virginia State Police maintain a Central Criminal Record Exchange (CCRE), which provides monthly reports of new convictions in the state court system to the Virginia Department of Elections.

The U.S. Attorney's Offices provide updates of felony convictions in Federal courts. The Virginia Department of Elections then notifies general registrars. Between September 2020-August 2021, 5,569 voters were removed from the rolls after a felony conviction. In the same time period, 32,398 people who had completed their sentences were registered to vote after having their rights restored by the Governor.

In 2022, the Virginia Department of Elections revealed that some felons were voting illegally. Those who had committed a second felony, after having voting rights restored, automatically lost the right to vote again. However, the computer system used by the Department was 15 years old and could not be programmed to routinely remove a person from the voter rolls after having rights restored. The Department of Elections had to make an extra effort to notify local registrars until the software could be replaced.

The state agency notified registrars that in one year (September 1, 2022 - August 31, 2023) that 17,368 people had been convicted of a new felony after their rights had been restored. However, the notifications included named of people who had not been convicted of a felony, but instead had just violated parole. The Virginia Criminal Information Network, the state police's computer system used to update the Voter and Election Registration Information System (VERIS), did not distinguish between parole violations for a previous felony and a new crime.

One person in Arlington, blocked from voting in the June 2023 primaries, successfully sued to get added back into the pollbook in time for the November 2023 election.

Another lawsuit was filed after Governor Youngkin stopped the practice of the previous three governors of automatically restoring the right to vote after felons had completed their sentences and made full restitution. The Governor required felons to apply for restoration, and there was a significant reduction in the number of restorations.

The lawsuit by three disenfranchised felons contended that the automatic stripping of the right to vote violated Virginia's commitments made in 1870 in order to be readmitted back into the Union after the Civil War.5

Before the November 2021 election, the Virginia Department of Elections identified 14 jurisdictions with over 100,000 voters each:6

Ten jurisdictions had less than 5,000 voters each:7

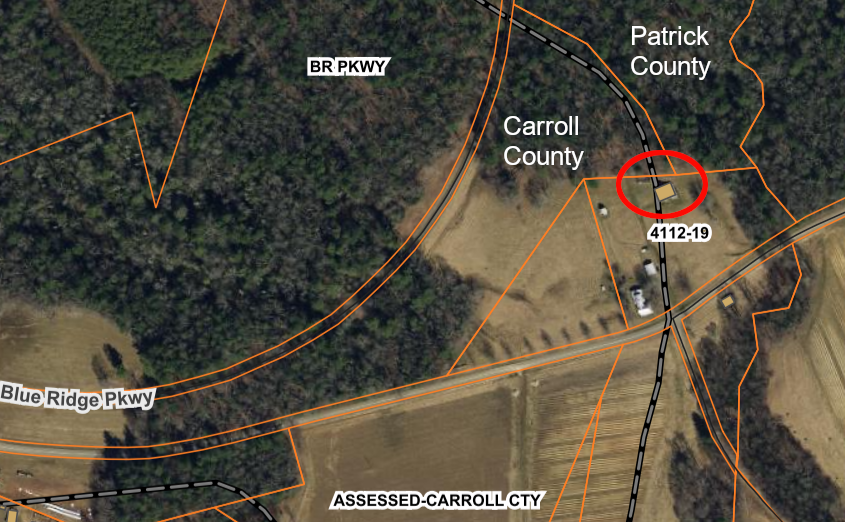

Geographic Information System (GIS) technology has enabled local jurisdictions to identify where houses thought to be within one jurisdiction are actually located across a boundary line. In 2023, Patrick County officials removed a voter from the rolls after determining his house was located in Carroll County. The voter had participated in Patrick County elections for the previous 35 years.8

a Patrick County voter was notified in 2023 that his house was in Carroll County and he should vote in that jurisdiction

Source: Patrick County