members of the James City County court were appointed by the General Assembly, not elected by voters, until 1851

members of the James City County court were appointed by the General Assembly, not elected by voters, until 1851

The first formal vote by Virginia colonists was after the Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery arrived at the Chesapeake Bay.

The London Company had appointed Christopher Newport as the commander of the three-ship expedition that left London in December 1606 and carried over 100 people planning to live permanently in Virginia, but Newport would return home and others would govern the colony after arrival. Once the ships reached Virginia, the sealed box with the names of the new leaders was opened.

The company's instructions appointed John Smith as one of the seven people on the council that would govern the colony, but the other appointees immediately decided to block him from participating. Smith had been locked up for most of the journey across the Atlantic Ocean. Evidently he was not very gentle when expressing his point of view, and others on the ships were not experienced at working together as members of a team. Captain Newport even proposed to hang Smith while the expedition sailed through the Caribbean before turning north to reach Virginia in April, 1607.

Because Smith was blocked from participating in the first vote to choose a President of the Council, voter suppression began at the very start of colonization in Virginia. Smith was added to the council with the right to vote before Captain Newport sailed home in June, 1607, but the Council remained a dysfunctional group of leaders.

There was voting in Virginia from the beginning of English settlement, but the number of voters was always tightly constrained. Only existing members of the Council (or company officials in London) could select new members of the Council; the other colonists had no ability to choose their leaders. Only members of the governing council, or the political/military leaders later appointed by the company, were authorized to vote on managing the colony until the company created a representative assembly in 1619.

Two months after Newport returned to England, half the colonists were dead or dying. The members of the Council accused their President, Edward Maria Wingfield, of hoarding food. By a vote of the council, Wingfield was deposed.

Council membership shrank further when Bartholomew Gosnold died and George Kendall was executed, after being condemned by the Council as a Spanish spy. The number of voting members on the council dropped to three, until they finally added new leaders.1

The creation of the 1619 assembly reflected a shift in strategy by the Virginia Company, which owned the colony. To manage operations in Jamestown after 1613, the company had imposed martial law. Directing the indentured servants was still possible, but colonists were completing their terms of indenture. The Virginia Company needed a new governing mechanism. Giving colonists a role in shaping local laws also was expected to spur more people in England to emigrate to Virginia, making the colony a more-profitable investment.

The very first assembly in 1619 rejected the two representatives elected from Martin's Brandon, because James II had made that plantation exempt from some company control. The other 20 members elected to serve in the first assembly concluded that if Captain John Martin's plantation, Martin's Brandon, was not obliged to comply with the decisions of the assembly, then its representatives would not be allowed to join the assembly and make policy for the entire colony.2

The number of Virginians with a vote has expanded since the first assembly was created in 1619. The dissolution of the Virginia Company in 1624 and conversion of Virginia into a royal colony created uncertainty regarding the authority of the General Assembly, but Virginians kept electing representatives and they kept passing laws until finally getting royal confirmation of their legitimacy.

Once local jurisdictions were created in 1634, representation was based on county boundaries. Voters in each county chose two men who served in the General Assembly. One representative was authorized for Jamestown in 1684, the College of William and Mary in 1718, Williamsburg in 1723, and Norfolk in 1738. Local voters chose their members of the House of Burgesses between 1643-1776, and elected members to the House of Delegates and also the State Senate between 1776-1851. Just the white male property owners ("freeholders") were allowed to vote.3

Throughout the colonial period, landowners could run for a seat in the House of Burgesses from any county in which they owned property. George Washington was first elected to the House of Burgesses from Frederick County in 1758. He chose to run for office in Fairfax County in 1761, and represented that jurisdiction until 1775.

Voters could choose their representatives to the House of Burgesses in the General Assembly. Local residents also voted for the initial members of the Anglican vestry which governed the local parish and provided social services.

After electing the initial vestry, voters had no role. All replacement members were elected by the vestry rather than by the voters. Taxes imposed by the vestry were mandatory and collected by the sheriff. They could exceed taxes imposed by the county court, especially if the vestry decided to build a new church or make major repairs to church buildings.4

Local residents in Virginia did not elect the members of the local county court, the equivalent to today's Board of Supervisors combined with today's District court judges. The members of the county court appointed other local officials, such as the sheriff and the clerk of the court.

The governor and the General Assembly appointed all officers in the county militia as well. Voters elected no county officials during the colonial era. Officials who had been appointed by the colonial/state government, not elected by local voters, made public policy decisions on local issues such as county tax rates.

the General Assembly, meeting in Jamestown and Williamsburg, appointed the members of every county court in Virginia from 1634-1776

Source: Library of Congress, The capitol Williamsburg

The number of people in the House of Burgesses increased between 1634-1776 as new counties were created. As population increased, the boundaries of existing counties were revised to split large counties into smaller ones. Shaping county boundaries so the courthouse would be within a one-day journey of most residents did more than increase the number of members in the House of Burgesses. Creating new and smaller counties also increased the potential that the desires of local voters would be reflected in decisions made at Jamestown/Williamsburg, when the General Assembly appointed members of the county court.

The General Court, composed of the governor and Council, handled all appeals and most capital cases. Colonial officials in Jamestown/Williamsburg had great control over the governance of every local jurisdiction. The process for making policy decisions has always been centralized in the capital. Democracy was established in Virginia from the top down, not from the bottom up.

Voters gained the right to elect directly many local officials when the state constitution was revised in 1851. The General Assembly has always retained the power to appoint all judges in Virginia.

only men could vote or serve as an elected official during the colonial period

Source: Virginia Division of Capitol Police

Voting in colonial Virginia was not a common experience, or one that was regularly scheduled. Colonial governors determined when elections would be held for the House of Burgesses. Certain events, such as the arrival of a new appointed governor or even the death of the king/queen in England, could trigger the governor to dissolve the General Assembly and issue a call for a new election.

Governors also dissolved the General Assembly at times when the Burgesses refused to comply with royal instructions or demands by the governor, and the governor hoped new Burgesses would be more compliant. In many parliamentary systems, the Prime Minister still determines when new elections will be held and can pick a time considered advantageous for his/her political party. In Great Britain elections must be scheduled at least every five years now after passage of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act in 2011.

Prior to 1776, Virginia voters had no opportunity to elect representatives to any organization with responsibilities beyond Virginia. The inability to elect members to the British Parliament, or find some other way to ensure representation before taxation, was highlighted as one cause of the American Revolution.

Only white male property owners were allowed to vote in the colonial era. The logic for limiting voting rights in the colonial era was that children, wives/daughters, indentured servants, slaves, and poor tenant farmers without their own land were financially dependent upon white male property owners. If everyone was allowed to vote, then a few rich people would be able to tell everyone dependent upon them how to vote. Limiting the right to vote thus created a more equitable democracy, reducing the political power of the very rich.

Not everyone agreed with that logic, or with the limited ability to elect local officials in colonial Virginia.

Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 was triggered in part by the desire of land-hungry settlers to seize territory controlled by Native Americans. However, Nathaniel Bacon was able to recruit an army in part because so many people were unhappy over their inability to influence who would serve in local office, and alter the taxes imposed by those local officials. Colonists unhappy over decisions made by appointed officials in the counties (as well as by the members elected to the House of Burgesses) joined Nathaniel Bacon and rebelled in 1676, confronting Governor Berkeley at the statehouse in Jamestown and burning the colonial capital later that year.

As Brent Tartar, a historian at the Library of Virginia described it:5

Nathaniel Bacon confronted Governor Berkeley at the statehouse in Jamestown, and burned the colonial capital later in 1676

Source: National Park Service, Bacon's Rebellion (painting by Sidney E. King)

The House of Burgesses in the General Assembly represented the voters in Virginia counties. Between 1625-1776, the Council (the other house of the General Assembly, which divided into two sections in 1643) and the governor were appointed by the king. The governor's ability to prorogue (end) a session of the General Assembly was used to block the House of Burgesses from voting against the desires of the royal government. In 1765, Governor Francis Fauquier ended the meeting of the House of Burgesses before it could vote on sending representatives from the colony of Virginia to the Stamp Act Congress.

Governor Francis Fauquier blocked appointment of Virginia representatives to the Stamp Act Congress when he prorogued the House of Burgesses in 1765

Source: Library of Congress, Patrick Henry before the Virginia House of Burgesses May 30, 1765

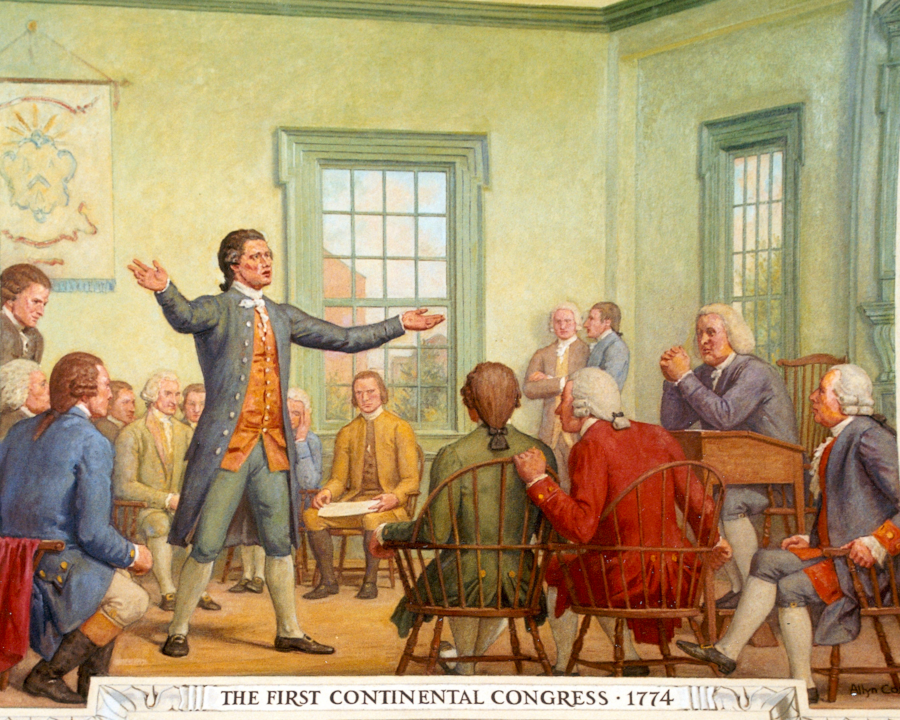

Lord Dunmore's efforts did not stop Virginia from being active in the Continental Congress meetings that started in 1774, and to the Congresses later organized under the Articles of Confederation. Virginia's representatives were not elected directly by the voters. The Virginia officials sent to Philadelphia were chosen by five Virginia Conventions, and then by the General Assembly after the Fifth Virginia Convention declared in 1776 that the colony was an independent state.

Virginia representatives sent to the Continental Congress meetings between 1774-1788 were not elected directly by Virginia voters

Source: Architect of the Capitol, The First Continental Congress, 1774

Sheriffs appointed by the county court ran each colonial election. They served as the equivalent of a modern electoral board, and ensured that voters were qualified before their vote was recorded.

The county sheriff scheduled elections after receiving official notice from the House of Burgesses. People owning land in a county could vote in that county, just as they could run for the House of Burgesses from it. It was possible for a person owning property in two counties to vote one day in one county for two Burgesses, and then travel to vote for a different pair of Burgesses in another county.

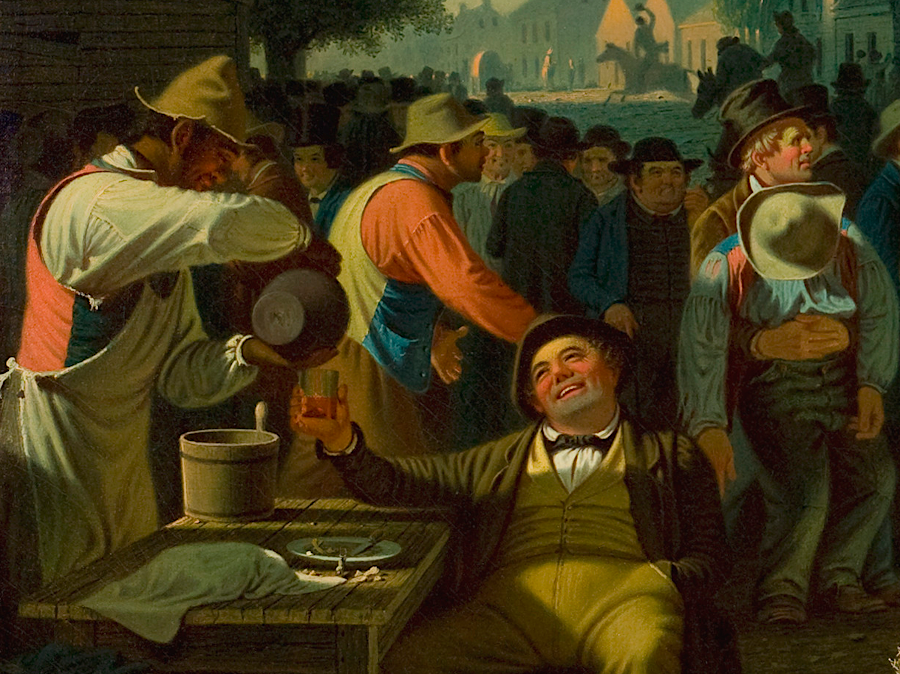

Throughout the colonial era and until the adoption of the written ballot after implementation of the Underwood Constitution in 1869, election day at the courthouse was a public spectacle. Elections triggered community gatherings and provided some of the major entertainment in the colonial era.

An audience would gather and observe how people voted. Voters came to the courthouse on election day and had to announce their vote by voice, speaking loud enough for the decision to be recorded by the sheriff. Everyone knew how a person had voted; the viva voce process involved no secret ballot.

The preferences for candidates, spoken publicly, were then entered into the poll book to create a written record of who had voted for whom, and to tally the winners. In the days before radio, television, and social media, crowds assembled to watch the decisions of each voter.6

Sheriffs could choose to hold the poll books open for two days to allow those living on the edge of a county to reach the courthouse. Sheriffs also could decide to close the poll when it appeared everyone eligible who was gathered around the courthouse had chosen to vote, or it appeared a decision was clear, or the sheriff's preferred candidate had a lead, or if the voters were getting too rowdy after enjoying alcohol provided by the candidates.

this painting of a county election in a small Midwestern town during the mid-nineteenth century shows how local voting traditions were retained beyond the colonial period

Source: Humanities- Picturing America, George Caleb Bingham: The County Election, c.1852

Initially, apparently all adult freemen could vote. The right to vote was limited briefly to just the heads of households (one person per family) in the 1650's. In 1670, Governor Berkeley required that white males had to own enough property to pay taxes before being allowed to vote.

The property restriction on who could vote was eliminated briefly when Governor Berkeley called for an election in 1676 at the start of Bacon's Rebellion. That election ended Virginia's "Long Assembly," which had lasted from March 1661 to May 1676. Governor Berkeley had refused to dissolve the General Assembly and allow a new round of elections for members of the House of Burgesses.

During the 15 years of the Long Assembly, elections had been held in counties only as needed to replace individual members who died or resigned. The colonial legislature, under the control of the wealthy landowners, continued to approve high taxes.

Those taxes were use to fund public offices given to just selected members of the gentry, and were not used for effective military practices that would prevent raids on the backcountry farms by Native Americans. The Virginia elite were viewed as expropriating the wealth of the freemen, the indentured servants who had served their time and were struggling to establish independent farms without adequate security and without a voice in the House of Burgesses.

In 1676, Governor Berkeley sought to re-establish the legitimacy of his colonial government by expanding the franchise and allowing white men without property to vote. His attempt failed, and Nathaniel Bacon led a rebellion that was Virginia's first civil war. In the process, houses of the Governor's wealthy supporters were looted and Jamestown was burned.

After Bacon's Rebellion ended, King Charles II ordered that the property requirements be reimposed. The General Assembly complied in 1684, and maintained that requirement for over 150 years. The 1850 Constitution finally abolished the requirement to own property in order to vote.

A substitute for the property owning requirement, the poll tax, was crafted after the Civil War. It was designed to suppress voting by the poor, especially by black men who had been enfranchised through the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution.7

The first constitution adopted by Virginia eliminated the potential of a governor manipulating the legislative branch by avoiding elections. The constitution included a schedule for elections on regular dates. Since 1776 Virginia's governor has never had the authority to change those dates, though the governor does have flexibility in choosing dates for special elections.8

There is now a significant election in Virginia every year, unlike the rare and intermittent voting process during the colonial period. In November of every odd-numbered year, Virginians who have registered to vote get the opportunity to select representatives to the General Assembly that meets in Richmond. Every four years, that election also includes statewide races for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General.

In every even-numbered year, modern Virginians can vote for candidates seeking to serve in the US House of Representatives that meets in Washington, DC. In some of those even-numbered years, there are also races for one of the state's two seats in the US Senate and for the US president.

The alternate-year pattern, resulting in an election every year, was created after adoption of the 1851 state constitution. That reduced General Assembly meetings by half, replacing annual sessions with biennial sessions. The first election for the state legislature after adoption of the new state constitution occurred in 1851, and state elections have been in odd-numbered years ever since.

Bacon's Rebellion in 1676 demonstrated the threat of mob rule. Until 1850, the Virginia elite ensured that the right to vote was linked to ownership of property. That requirement was designed in large part to protect the upper class Virginia families from excessive taxes. Residents of a county did not vote for members of the county court until 1851, after Virginia adopted its third constitution.

Because the franchise was restricted by race, gender, and wealth, voters often had interacted personally with candidates. A person's reputation, rather than political affiliation, was the most important factor in winning elections in colonial Virginia. There were no political advertisements in newspapers, and no process for "marketing" candidates.

However, candidates were expected to entertain the voters on election day with free drink. In 1757, George Washington ran for a seat in the House of Burgesses in Frederick County, after commanding troops there during the French and Indian War. The tavern keepers had been frustrate by his efforts to keep soldiers from consuming their alcohol, and organized behind an opponent. Washington was defeated, 270-40.

In the next election, he ran again and defeated the same candidate by 310-45. A key difference was his willingness to supply alcohol on election day, essentially sponsoring an all-day party at the courthouse. Historians have calculated that he bought a half a gallon of strong drink for every vote he received.9

candidates provided free alcohol on election day as a routine gesture to voters

Source: Saint Louis Art Museum, The County Election (painted by George Caleb Bingham, 1852)

In 1774-76, Virginia's leaders assembled in five conventions separate from the General Assembly. In the last convention, they declared independence and adopted the state's first constitution. It created a new form of government that removed all authority of King George III and Parliament, but did not alter who had the right to vote:10

George Washington was elected by the voters to serve in the House of Burgesses, but was never governor of Virginia

Source: National Gallery of Art, George Washington (painted by Gilbert Stuart, 1821) and George Washington (Vaughan portrait) (painted by Gilbert Stuart, 1795)

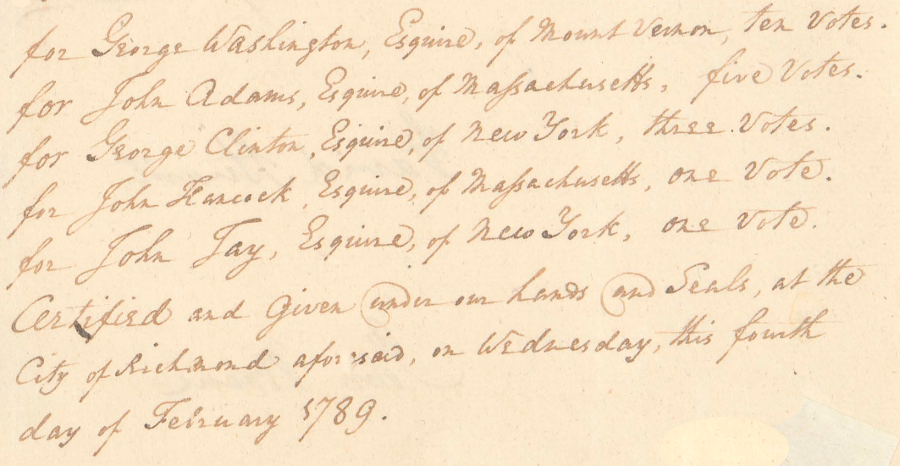

in 1789, the Virginia electors choosing the first president of the United States cast votes for five candidates

Source: Library of Virginia, A return of the State Electoral College and election certificates from the first Presidential election, 1789 February