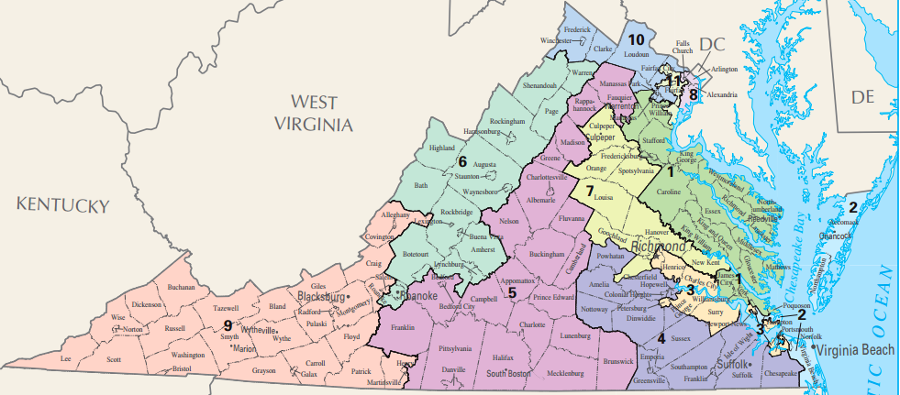

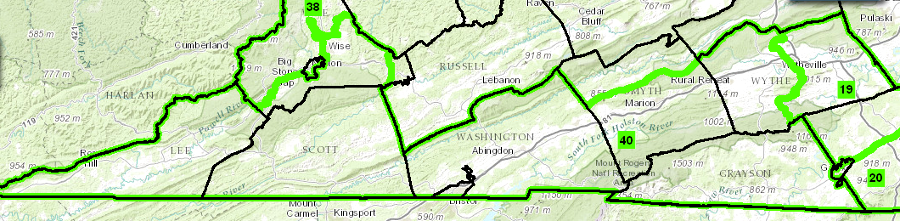

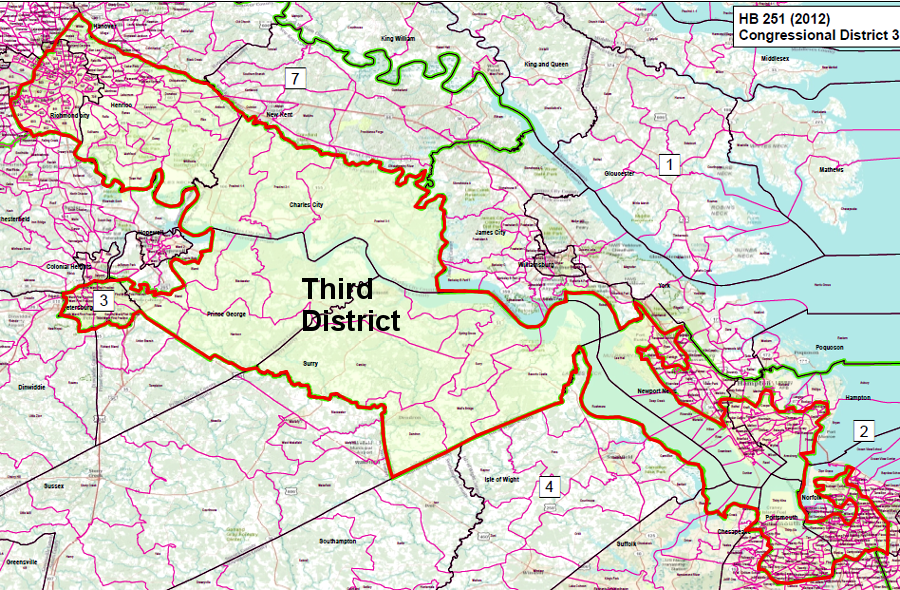

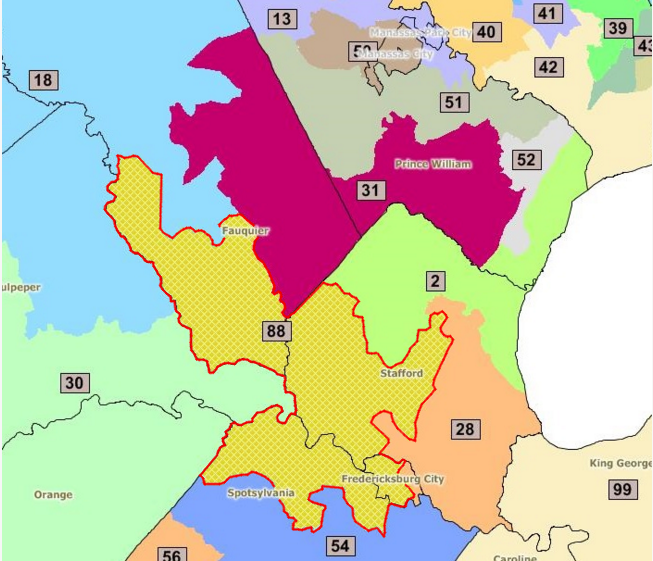

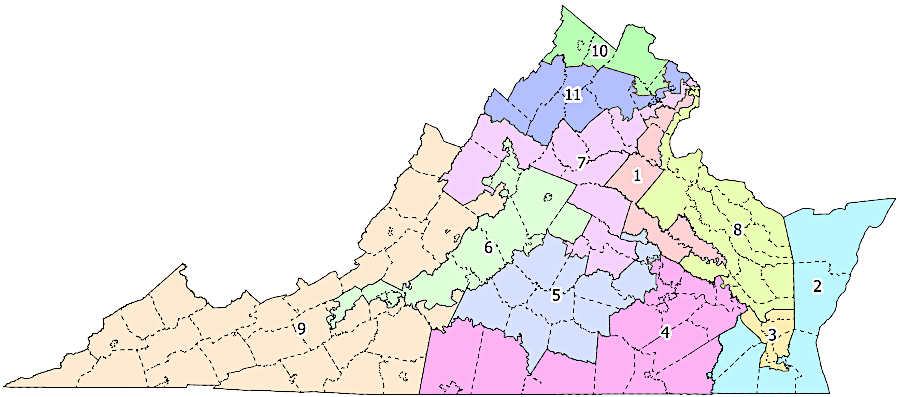

after the 2010 Census, the General Assembly drew new boundaries for the 11 districts for election to the US House of Representatives

Source: US Geological Survey, National Atlas, Congressional Districts - 113th Congress

after the 2010 Census, the General Assembly drew new boundaries for the 11 districts for election to the US House of Representatives

Source: US Geological Survey, National Atlas, Congressional Districts -

113th Congress

When Virginia voters elect their Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, and two US senators in statewide elections, the entire state constitutes one election district. District boundaries are irrelevant as well for the election of the US president and vice-president every four years; Virginia's 13 Electoral College members are determined by which candidates win the majority of votes within the entire state.

District boundaries are critical when voters elect 11 representatives to serve in the US Congress, 140 officials who serve in the General Assembly, and roughly 3,000 local government officials in various cities and counties. Every 10 years after the Census is completed, boundaries are drawn for the US House of Representatives districts, 100 districts for the House of Delegates, 40 districts for the State Senate, and many magisterial districts (or wards in cities) for electing local officials.

The Constitution of Virginia gives the General Assembly great flexibility to define the boundaries for election districts, requiring only that:1

The governor has the authority to veto the law creating new boundaries for state and Federal elections, and the state legislature has never marshaled enough votes to over-ride a veto. If one party does not control the governorship, House of Delegates and State Senate, then the 140 members of the General Assembly and the governor must compromise.

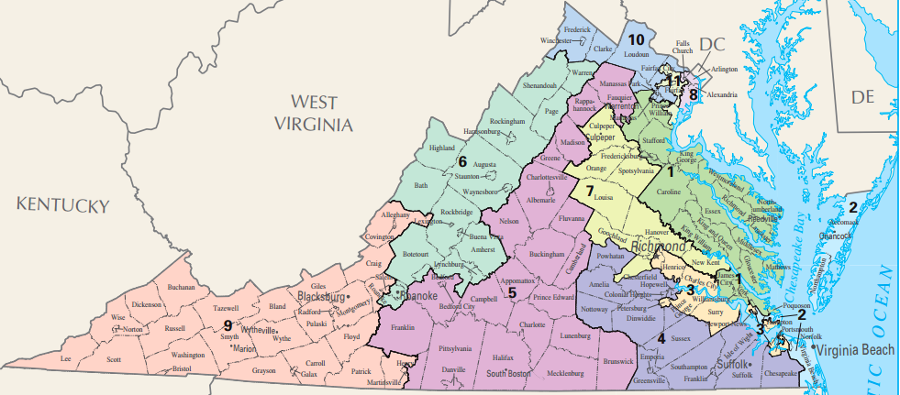

The "contiguous and compact territory" requirement in the state constitution does not require that state/Federal election districts must align with city or county boundaries. Where the election district boundaries are drawn can dramatically affect the number of Democrats or Republicans who win election.

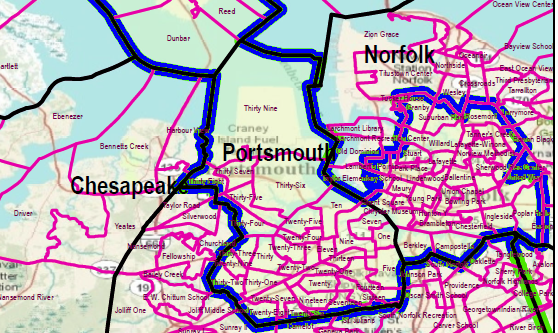

boundaries for House of Delegates districts 35, 27, and 67, drawn after the 2010 Census, meet the standard of "contiguous and compact territory" even though more-compact, more-contiguous polygons could have been defined

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting Plans - 2010

There has always been some "gerrymandering." That term honors Elbridge Gerry, who after the 1810 Census arranged for an election district boundary in Massachusetts with an unusual shape that resembled a salamander). Savvy politicians who understand geography, and particularly those able to apply Geographic Information System (GIS) technology effectively, can consciously include/exclude in a district the individual precincts with a traditional voting record.

Setting election district boundaries for state and Federal elections has always been controlled by the General Assembly. Each county, plus some special areas such as Norfolk and Williamsburg, elected members to the House of Burgesses in colonial times. County boundaries were used to define the election districts. Representation was not balanced by population; whether a county had a small or large population, it was entitled to elect two burgesses. Even the first meeting of the General Assembly in 1619, before county boundaries were created, consisted of two representatives from each populated area.

When Virginia passed its first constitution in 1776, the House of Burgesses was renamed the House of Delegates and each county continued to elect two delegates. A new State Senate was created, and for the first time the General Assembly created 24 electoral districts that included more than one county. Ratification of the US Constitution in 1788 required defining 10 districts to elect Virginia's first members of the US House of Representatives.

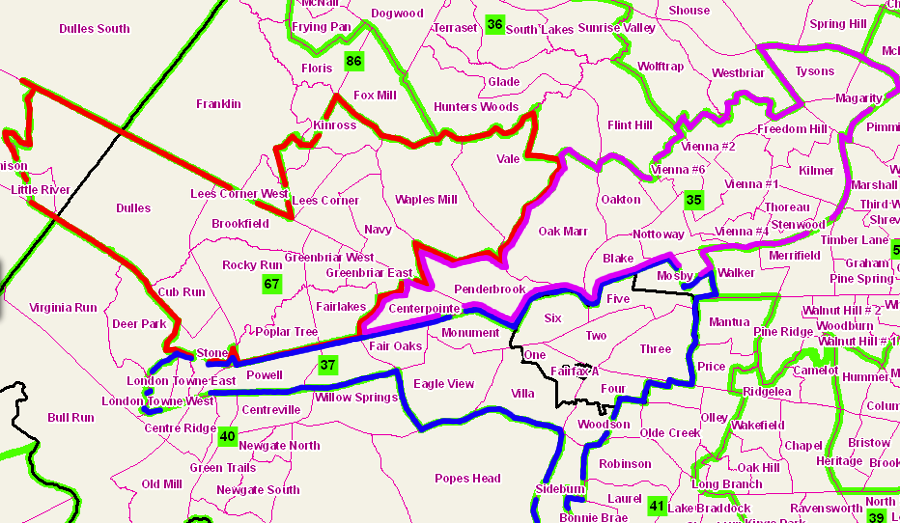

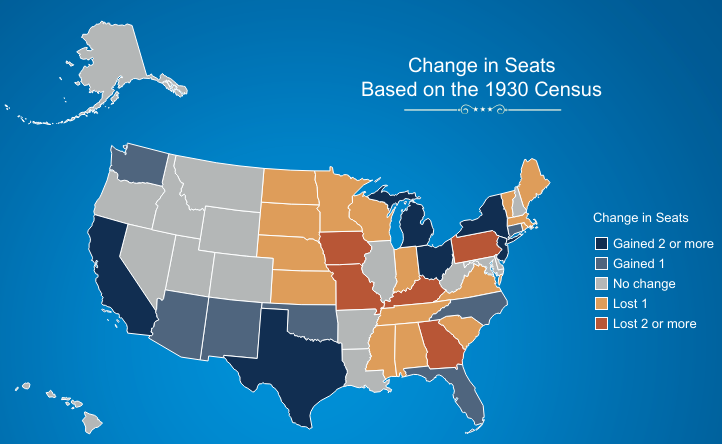

the most dramatic alteration in boundaries was the elimination of US House of Representatives districts for the 1932 election, so all nine members of the 73rd Congress were elected at-large

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Elections Database

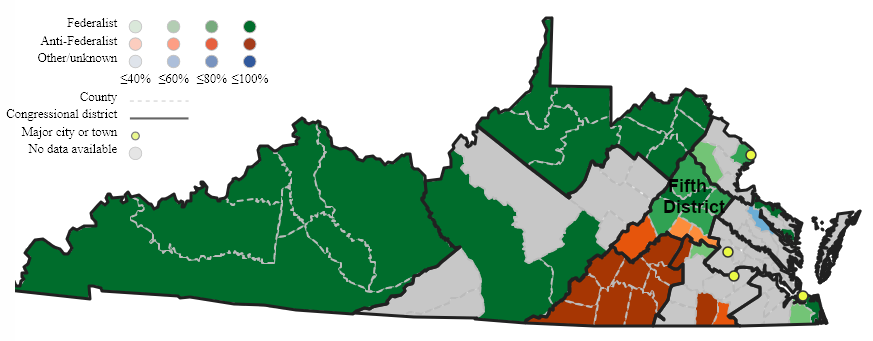

Establishing election district boundaries has always been a political process, not an analytical exercise based on just non-political criteria. The role of politics in defining districts was demonstrated during the October-November, 1788 General Assembly session, after ratification of the Constitution to create a new Federal government.

Patrick Henry successfully blocked efforts to choose James Madison as one of Virginia's first two Senators. When the General Assembly shaped the boundaries for the 10 House of Representatives districts, Henry maneuvered to ensure the Fifth Congressional District limited Madison's potential for election in 1789. Henry also ensured Madison must run in that particular district by getting the legislature to require candidates to have lived in their district for twelve months previous to election, even though the new Constitution only required that candidates live within the state.

The Fifth District included Orange County with James Madison's home, Montpelier. Henry's Anti-Federalist allies drew the district's boundaries to exclude Fauquier County, and to include other counties that had many anti-Federalist voters. The votes in the June 1788 convention for/against ratification of the new Constitution had revealed those who, like Henry, "smelled a rat" in creating a new central government that would limit the powers of the 13 separate states and might constrain individual liberties as well. There were six counties in the Fifth District, and 11 of the 16 delegates had voted against ratification.

Madison had promised to reform the initial US Constitution by adding amendments to protect individual liberties. Henry sought to keep Madison out of the US Congress in hopes that the reform effort would fail and a second convention would be called to revamp the document. New York and Virginia had already called for a second convention. If Henry could get seven more to submit petitions for a convention, then he would cross the threshold in the new Constitution of two-thirds of the states triggering another meeting.

in 1789, Patrick Henry ensured the Fifth District included anti-Federalist Amherst, Fluvanna, and Goochland counties (orange shading)

Source: Mapping Early American Elections, 1st Congress: Virginia 1789

At the ratification convention, representatives from only two counties within the Fifth Congressional District (Orange and Albemarle) had voted to create the new Federal government with which Madison was closely associated. All representatives from Amherst, Fluvanna, Goochland, Culpeper, and Spotsylvania counties had voted against ratification, and Louisa County's representatives had split their vote. An 1880 biographer noted:2

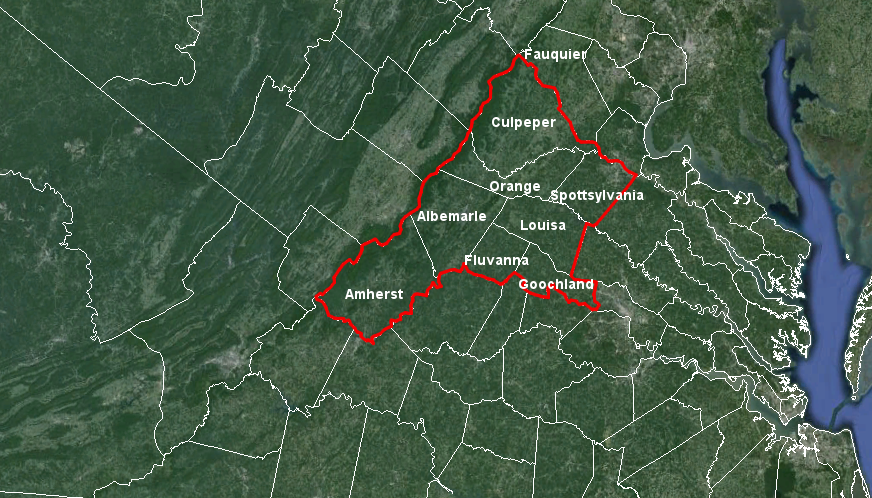

boundaries of the 5th Congressional District were designed by the Anti-Federalists in 1788 to exclude Fauquier County, in hopes of blocking the election of James Madison to the new US House of Representatives

Map Source: Google Earth

To further handicap Madison, Henry arranged for the General Assembly to elect Madison in November 1788 as a member of the last Confederation Congress. Friends warned James Madison that he was at risk of losing the February 2, 1789 election. Madison's participation as a member of the Continental Congress in New York City kept him from campaigning in person against his opponent James Monroe.

Madison replied that he would the decision to travel home after learning the boundaries of the Fifth Congressional District, even though he was suffering from painful hemorrhoids:3

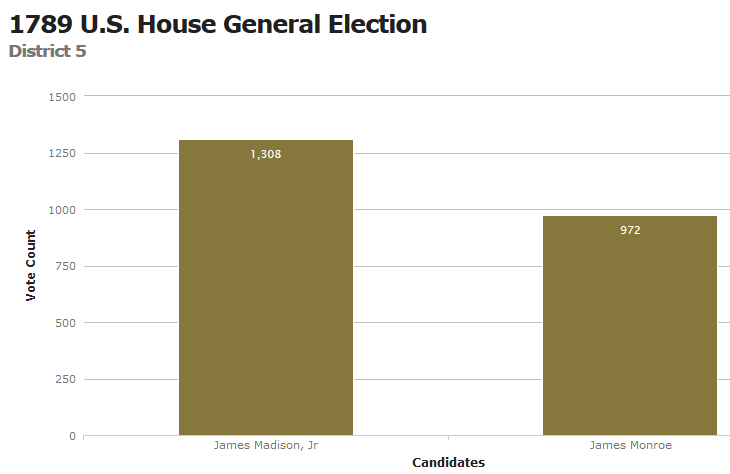

despite "henrymandering," James Madison defeated James Monroe for election to the first US House of Representatives

Data Source: Virginia State Board of Elections, Elections Database

Madison was effective in his campaign appearances, and his letters published by local newspapers reassured voters that he would seek amendments to the Constitution to ensure protection of individual rights. Patrick Henry's attempt to shape the decision by shaping the district failed. Madison was elected to serve the Fifth District, winning 1,308 votes vs. the 972 cast for James Monroe. Madison then fulfilled his election promises by ensuring passage of ten amendments that are known today as the Bill of Rights, and no second convention has ever been called to revise the US Constitution.4

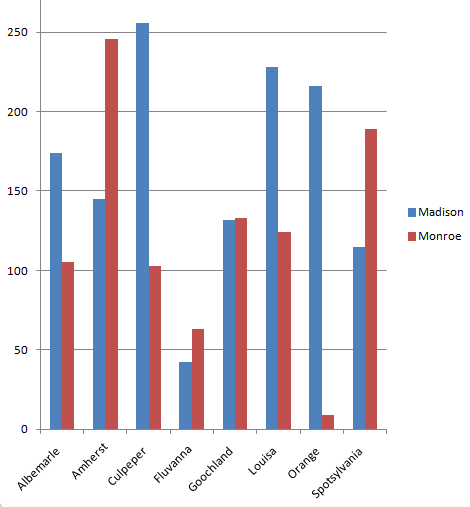

Amherst County voted heavily for James Monroe as expected in the 1789 election for the Fifth Congressional District, but James Madison won over enough voters in Culpeper and Louisa counties to win

Data Source: Thomas Rogers Hunter, The First Gerrymander?: Patrick Henry, James Madison, James Monroe, and Virginia's 1788 Congressional Districting (p.800)

Though the General Assembly declared independence from Great Britain and created a new form of government in 1776, the legislature did not alter the traditional pattern of domination by Tidewater representatives. Prior to 1776, Tidewater control was maintained by limiting the number of new counties that were created as population moved westward. Since each county elected two burgesses, having many counties in the east and fewer counties in the west ensured political power was retained.

Institutionalized discrimination against western voters continued as the boundaries of the first 24 State Senate districts were defined. A small number of western districts were created, and the imbalance in the population within eastern vs. western districts was ignored. As a result, a relatively small number of voters living east of the Fall Line retained political power.

In the first half of the 1800's, the legislature through the Bureau of Public Works directed most of the state's investment in transportation infrastructure (roads, canals, and railroads) to benefit eastern port cities. Western voters were unable to end the discrimination, even though they forced revisions in the state constitution in 1830 and 1850.

After the Civil War and the separation of the western counties to create the new state of Western Virginia, the sectional differences were less intense - but redistricting remained a key tool of concentrating/diffusing political power. After adoption of the 15th Amendment and a new state constitution in 1870 that allowed black men to vote for local officials, white officials established magisterial district boundaries in the counties to dilute the potential that black voters might elect a majority of black officials.

In Orange County, the white officials gerrymandered the boundaries of the four magisterial districts (known originally as "townships"). A 1907 history recorded the racial basis for the drawing the original district boundaries in Orange County:5

As population increased in urban areas and manufacturing became a larger part of the Virginia economy, the legislature remained controlled by rural legislators focused on low taxes.

Funding increases for education, transportation, and other services provided by state government were limited. After every Census, the desires of the increasing population in the cities to expand government services were constrained by drawing state legislative district boundaries so rural counties always elected an effective majority to the General Assembly. The Byrd Organization may not have controlled a majority of voters, but through rural county courthouse cliques it did control a majority of elected legislators.

The 1960 redistricting was the last to ignore significant population differences between electoral districts. The 1961 maps placed 539,618 people into the 10th Congressional District and only 312,890 in the 7th.

The 1964 decision of the US Supreme Court in Reynolds v. Sims, together with the 1965 Voting Rights Act, forced a dramatic break from traditional Virginia electoral procedures. The court forced states to draw new boundaries to apply the "one person-one vote" principle to state elections.

The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals ruled in 1965 that the General Assembly had to redistrict the Congressional boundaries to ensure each person had equal representation. For the first time, a county was divided between two Congressional districts. Moving eastern Fairfax County out of Rep. Howard Smith's 8th District altered the makeup of the voting population and led to his surprising defeat in the Democratic primary in 1966.

Since 1965, Virginia courts have also required using the "one person-one vote" criterion to draw boundaries for local elections for City/Town Councils and county Boards of Supervisors, plus the House of Delegates and State Senate.

The first redistrict map drawn in 1971 for House of Representatives districts retained too great a disparity in the number of voters in each district. The boundaries were skewed to protect two Democratic incumbents in Congress, but Federal courts forced a revision. The General Assembly's 1972 map split Chesterfield and Stafford counties plus the City of Virginia Beach, and led to the election of three new members of the House of Representatives.

The 1980 Congressional map partitioned Prince William County between separate districts for the first time, but re-united all of Virginia Beach into one district.

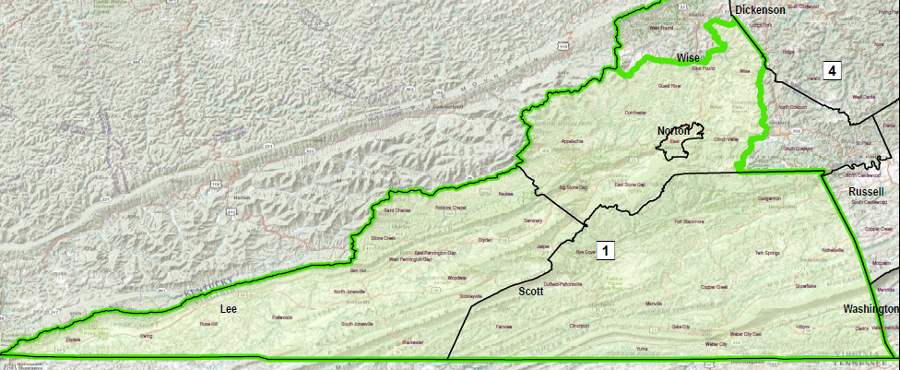

the State Senate has 40 members, and the 40th (Senate) District stretches from Cumberland Gap to Mount Rogers

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Current District Maps - State Senate District 40

the Virginia House of Delegates has 100 members and House District 1, like State Senate District 40, is located in southwestern Virginia

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Current District Maps - House of Delegates District 1

The state legislature that determines the boundaries of political districts includes a changing mix of Republicans, Democrats, and occasionally Independents, but the General Assembly is always composed of 100% political incumbents.

The once-every-10-year process for drawing electoral district boundaries, after each census, allows the elected politicians in the General Assembly (and the governor) to choose their voters, before the voters choose the officials in the next election. Computerized assessment of voting patterns, housing patterns, and various socio-economic factors (such as percentage of students qualifying for a subsidize school lunch) make it more feasible every redistricting cycle to choose which party will win a particular district.

The successful politicians, the ones who got elected to the General Assembly/governor's office or who run the two dominant parties, control the redistricting process every decade. Those same 140 General Assembly politicians (and the governor) also revise voting districts of friends/allies in local magisterial districts in the counties across Virginia, local wards in the cities which elect by geographic units rather than "at large," and the 11 districts for the US House of Representatives.

Gerrymandering is achieved by:

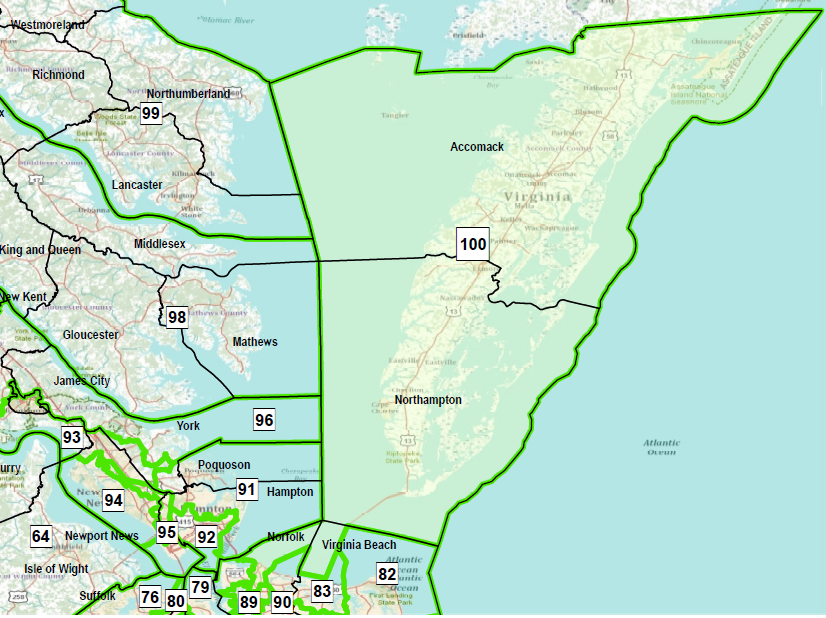

House of Delegates District 100 is located on the Eastern Shore

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Current District Maps - House of Delegates District 100

The House of Delegates and the State Senate, together with the governor, use the redistricting process to provide political advantage to the incumbents. District boundaries are carefully designed to exclude precincts with hostile voters and to include precincts with a high percentage of supporters. The redistricting process can create a "safe seat" for several election cycles before socio-economic trends, such as migration from urban areas into the suburbs, may alter the balance.

Drawing the boundaries involves assessing the strength of incumbents, and how much the entrenched incumbents can risk a loss of supporter-rich precincts. Candidates need only a plurality of the votes to win in each district. If you add up the votes from 100 House of Delegates districts statewide, the total could be close to 50-50. However, if 55 of your party's candidates win very close races, while the other party wins 45 seats in a landslide... your party would end up with clear control over the House of Delegates.

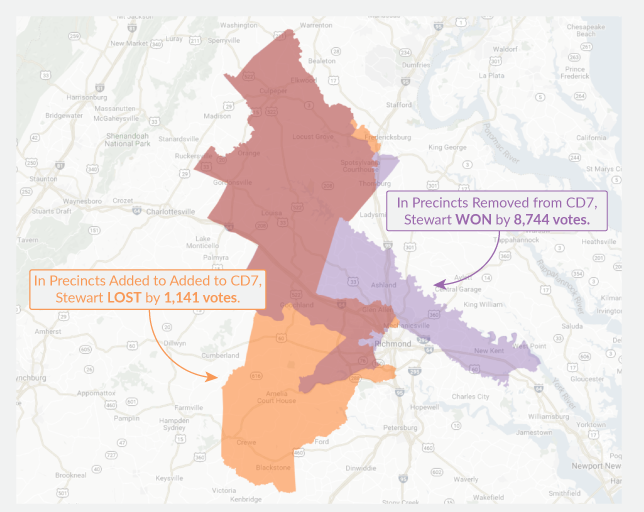

The 2014 primary election for the Seventh Congressional District showed that simple assessments of Republican vs. Democratic precincts is not sufficient. The Majority Leader of the Republican Party in the US House of Representatives, Rep. Eric Cantor, was defeated by a more-conservative Tea Party candidate despite raising $5 million for a campaign fund vs. his opponent's $200,000. It was the first time any Majority Leader was defeated in a primary.

As described by the Washington Post:6

The Seventh District was a safe Republican seat after the 2011 redistricting, but the new voters added on the eastern edge were anti-establishment Republicans who voted the incumbent out of office. Cantor's position of power as Majority Leader within the hierarchy of the House of Representatives was a disadvantage, and the realignment of district boundaries backfired.

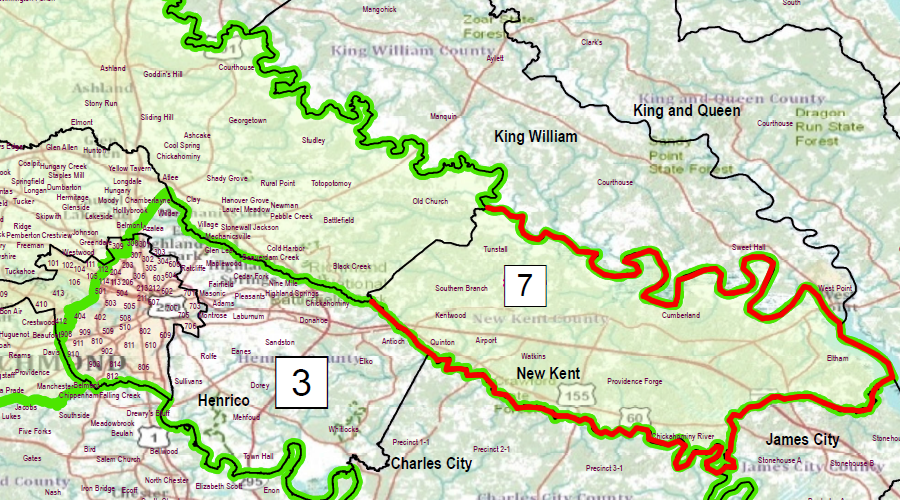

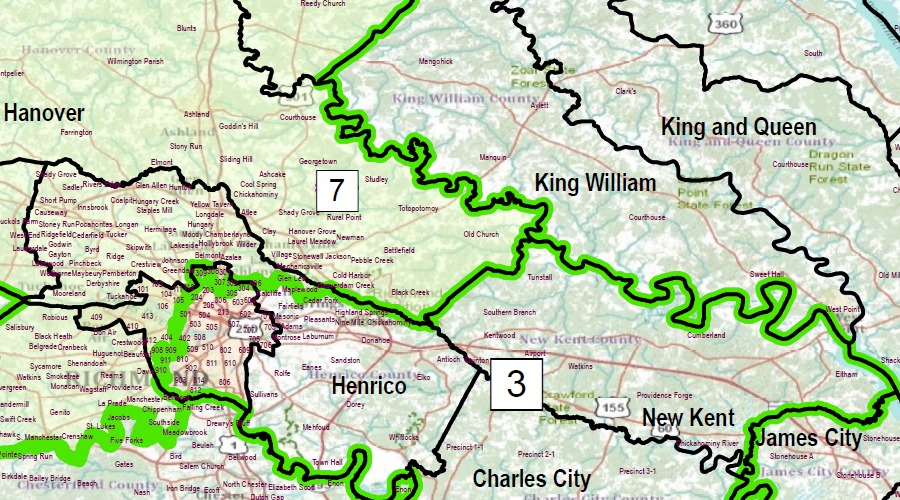

boundaries of the US House of Representatives Seventh Congressional District, represented by Rep. Eric Cantor, were redrawn in 2011 to add the conservative Republican voters in rural New Kent County

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Seventh Congressional District - Current

before the 2011 redistricting, New Kent County was in the Third Congressional District

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Seventh Congressional District - 2010

Various independent and non-partisan groups can suggest boundaries and argue that hyper-partisan districts are the fundamental cause of government gridlock, but their recommendations are simply advisory. In 2011, the proposals of the Independent Bipartisan Advisory Commission on Redistricting, appointed by the governor, were ignored just as quickly as proposals made by various outside interest groups.

Proposals to create an independent panel to draw new election district boundaries after the 2020 Census were killed by the chair of the House of Delegates House Privileges and Elections Committee in the 2015 session of the General Assembly without a public vote. Frustrated advocates for independent redistricting in 2021 complained:7

The OneVirginia2021 lobby group asserted that the boundaries of towns/cities/counties were ignored in the 2011 redistricting. Including an entire town/city/county in one legislative district would align a local jurisdiction's community of interest with the focus of legislators, but:8

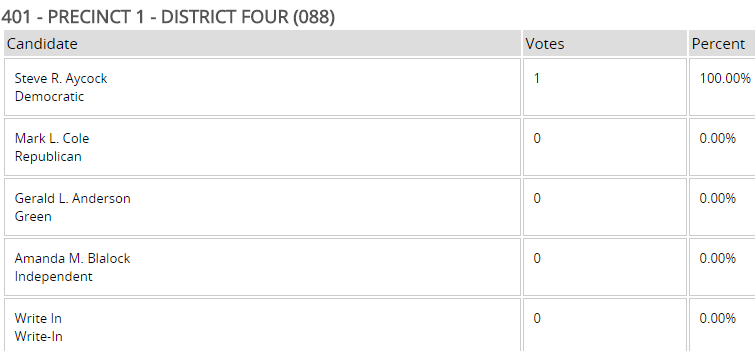

Splitting precincts isolates voters into small pools. Despite the secret ballot, the small number of voters can occasionally reveal how a single person voted.

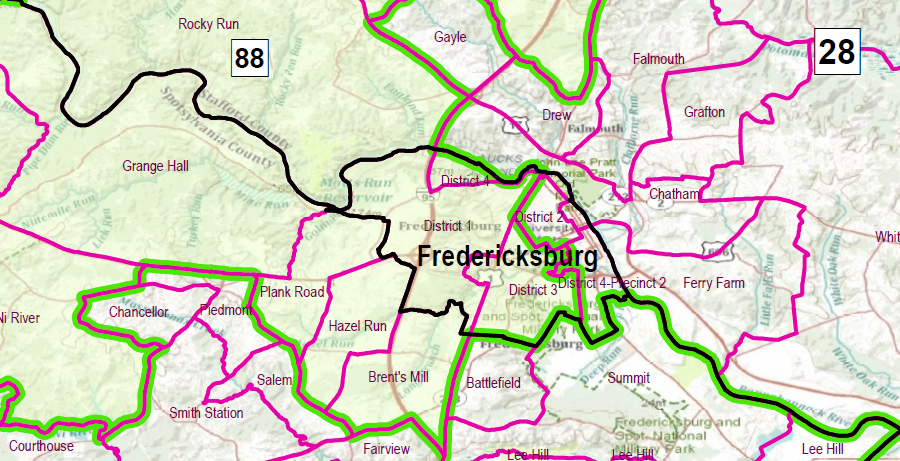

In the November, 2017, election, only one person voted in Fredericksburg's District 4, Precinct 1 for the 88th District seat in the House of Delegates. Virginia adopted the "Australian" ballot in 1894, so how an individual votes is supposed to be secret. However, the identity of every person who actually votes in an election is public information. A check of that public data would reveal who voted in 2017 for the Democratic candidate in Fredericksburg's District 4, Precinct 1, for the 88th District.

the 2017 election for the 88th District demonstrated that a person's vote can become public knowledge, if they are the only voter in a precinct

Source: Virginia State Board of Elections, 2017 November General Unofficial Results

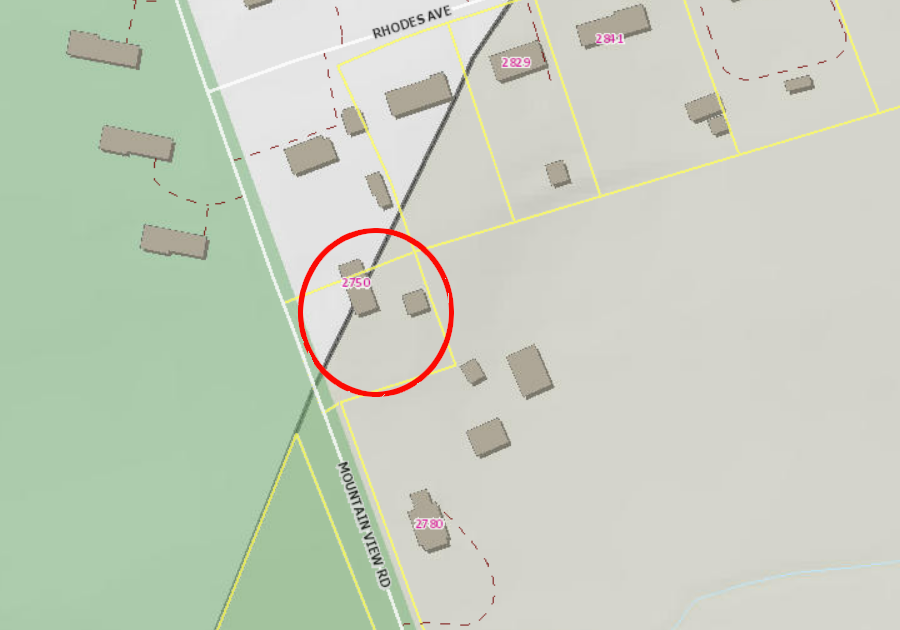

After the 2021 redistricting maps were determined by the Virginia Supreme Court, just one house in Bedford County ended up in the Sixth Congressional District. That occurred when the Census Bureau adjusted the boundaries of Census tract 312.01 in the 2020 Census to include a tiny portion of Bedford County, and redistricting was based on Census tract boundaries. Neither Bedford nor Roanoke County had notified the Federal agency regarding any change in county boundaries, and Census tracts are never supposed to cross jurisdictional boundaries, so the reason for the change was unclear.

The boundary change required Bedford County to maintain a split precinct, with extra costs because voters in that precinct were in the Ninth as well as the Sixth Congressional District. The two residents in that one house noted in 2022 that they were Libertarians and would not participate in that year's Republican primary. Had they chosen to vote, the official records would have revealed their choices.

after 2021 redistricting, only one house in Bedford County ended up in the Sixth Congressional District

Source: Bedford County, Public GIS

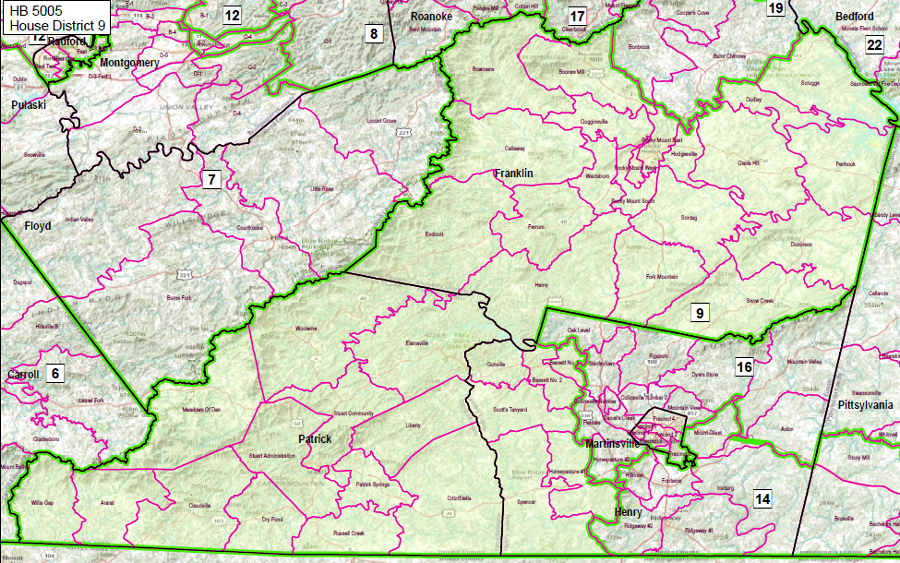

The redistricting after the 2010 Census had created a similar problem with a split district where the 38th District for the State Senate included Radford - and just three houses on Norwood Street in Montgomery County. Those houses were completely surrounded by the city after an annexation, but had arranged to remain part of Montgomery County. Since voting results are reported by jurisdiction, residents in those three houses had a less-than-fully-secret ballot until the State Sentate voting boundaries were revised after the 2020 Census.

three houses in an isolated part of Montgomery County (red lines) were in the 38th State Senate District between 2011-2021, so the voting results were less than secret

Source: Virginia Redistricting Commission, Current Senate (HB5005 Passed 4/28/11)

Confusion over who should receive which ballot in a split precinct, and what precincts should be assigned to which districts, may have affected the outcome of the 2017 elections. The Republican candidate in the 28th District, near Fredericksburg, won by just 82 votes. The Republican candidate's victory determined that the Republican Party would retain control of the 100-seat House of Delegates, with a 51-49 majority.

Democrats objected because 384 voters had been given the wrong ballots. The Virginia Board of Elections delayed certifying the final result in the 28th District, because registered voters has been assigned incorrectly between the 28th, 88th, and 2nd districts. As reported by WTOP, a post-election analysis revealed the problem:9

In redistricting, the requirements of the 1965 Voting Rights Act must be considered. It is no longer legal to unfairly dilute the ability of voters belonging to a minority race. As described in one redistricting primer:10

In 1981, the redistricting process was unusually difficult. Virginia had been dominated by the Democratic Party since 1883, but Republicans were starting to gain ground in state elections. Mills Godwin had converted to the Republican Party and been elected again as governor in 1973, and fellow Republican John Dalton was elected to that office in 1977. Democrats still controlled the General Assembly, but after the 1980 Census had to eliminate multi-member districts to meet Federal court requirements that declared multi-member districts unconstitutionally diluted the power of minority voters.

Drawing new boundaries that would preserve the election potential for all incumbents was not possible in 1981. Drawing 100 single-member districts required placing fragments of different cities/counties in different districts; there was no way to retain many city/county boundaries as House of Delegate district boundaries without multi-member districts. At one point, the House of Delegates approved a "fair and balanced" plan, but the map defined 101 districts - one too many. It took 14 different meetings before the House of Delegates and the State Senate reached final agreement.

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia then rejected the redistricting plan on August 25, 1981. In Cosner v. Dalton, a three-judge panel in the Federal court objected to the disparity between the number of people in different House of Delegates districts ("one person, one vote"). The realignment of boundaries around Petersburg also prevented a district there from having a majority-black population, diluting minority voting strength in violation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The courts ordered that elections be held in November, 1981 based on an unconstitutional plan, followed by another redistricting in 1982 that met the requirements of Federal laws. Delegates elected in 1981 served only one year, and those elected in 1982 under a legally-approved plan also served just one year.

In later redistricting cycles, election district boundaries also were drawn to protect incumbents of the majority party and to limit re-election potential of incumbents in the minority party. One technique was to place two incumbents of the minority party into the same new district. They had to run against each other, or one had to retire, move, or run for a different office.

In 1991, both houses of the General Assembly were controlled by the Democrats. They created a redistricting map to extend that control by placing 18 House Republicans into nine districts. They also drew a new Congressional District map that placed two Republican incumbents in the same district.

In 1991, George Allen won a special election to the House of Representatives for the 7th District of the House of Representatives. However, the Democrats in the General Assembly revised the boundaries so his home would be within the 3rd District in the 1992 election. The incumbent in the 3rd District, Rep. Thomas J. Bliley Jr, was a fellow Republican. Allen chose not to compete with Bliley for the Republican nomination, and also chose not to move to the nearby 6th District where the Democratic incumbent was retiring.

Instead, Allen ran for governor. He won in 1993, becoming just the fourth Republican elected to that office. The Democrats in the General Assembly, who sought to limit his political career by redistricting in 1991, launched him into a campaign for higher office. After serving as governor, Allen was elected to two terms in the US Senate.

Paul Goldman, the chair of the Democratic Party in 1991, was a close ally of Governor Wilder. He followed Wilder's direction to force the General Assembly's Democrats to revise their initial redistricting plan, which prioritized protecting incumbents, and to create more majority-black districts. Democratic members of the House of Delegates found a way to move their black supporters in 100 districts without risking reelection prospects.

In the 40 State Senate districts, however, creating three new black-majority districts required shifting reliably-Democratic voters and exposed incumbents to defeat in districts with a higher percentage of white voters. Republicans won more seats in November, 2021, reducing the Democratic majority to 22-18.

Wilder recognized that the winners in black-majority districts would be reelected multiple times and gain seniority. Black leaders with key positions in the General Assembly would, over time, finally empower a demographic group that had traditionally been marginalized by Democratic as well as Republican officeholders. Goldman wrote in 2025:11

Louise Lucas was elected to the State Senate in 1991 after redistricting created three new black-majority districts, and in 2023 became chair of the Committee on Finance and Appropriations

Source: Wikipedia, Louise Lucas

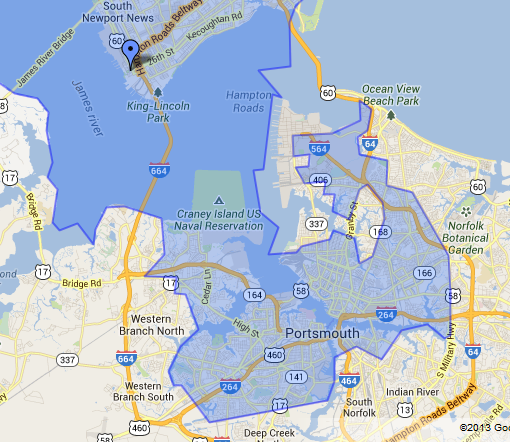

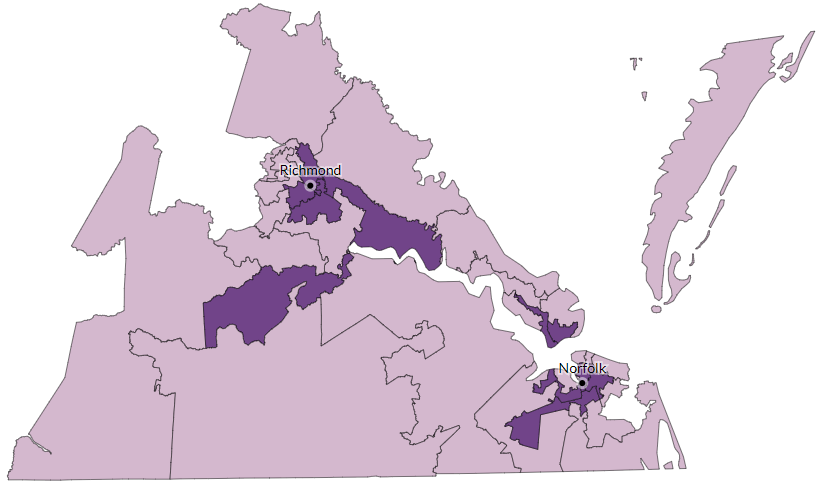

After the 1990 Census, Virginia was allocated an eleventh seat in the US House of Representatives. The 1991 map revised the boundaries of the Third Congressional District to establish Virginia's first "majority-minority" district, one where black voters were concentrated and likely to elect their preferred candidate.

In the subsequent election, the voters of the district elected Bobby Scott, Virginia's second black member of Congress and the first since John Mercer Langston in 1889. However, in 1997 a panel of Federal judges required the boundaries to be revised, because the shape of the district was determined too closely by the racial characteristics of its voters and the boundaries were not sufficiently compact.

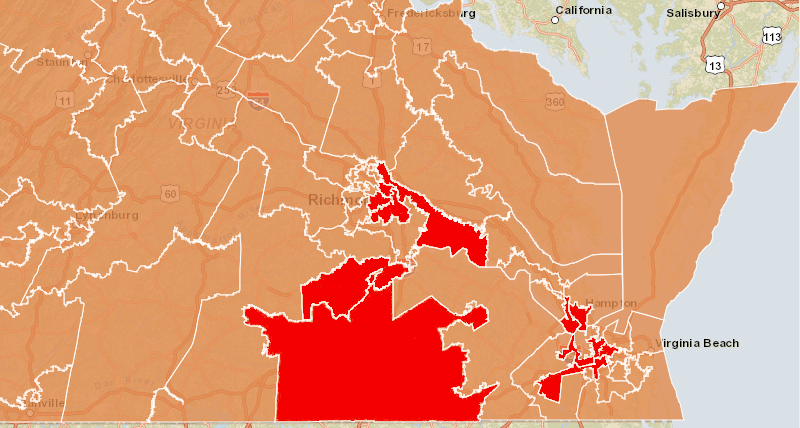

in the 1990's, the Third District boundaries were drawn to include precincts in Norfolk with a high percentage of minority voters

As described in a Washington Post news story, the judges described the district as a "grasping claw" or a "squashed salamander", one that did not reflect city/county boundaries or communities of interest:12

The 1998 revised map lowered the black voting age population in the Third District from 61.6% to 50.5%. Rep. Scott still won re-election, as did the incumbents in adjacent districts.

The General Assembly's redistricting after the 2000 Census packed more black voters into the Third District, and that was repeated after the 2010 Census. Concentrating black Democrats into one district streamlined re-election of Rep. Scott to the US House of Representatives, but also helped Republican candidates win in adjacent Congressional districts from which black Democrats had been removed.

In 2000 and 2010, the Third District boundaries were extended across Hampton Roads into urban precincts in Norfolk that had a high percentage of black residents. That split Norfolk's representation between the Second and Third Congressional districts. As Rep. Bobby Scott won elections easily in the Third District, a Republican candidate in adjacent districts benefitted from retaining the more-conservative precincts in other Norfolk neighborhoods.

after the 2001 redistricting, the boundaries of the Second District included the conservative military precincts at the Norfolk Naval Base and the minority residents of Norfolk were located in the Third District

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Legislative Services, Current District Maps

a decade later, the Third District still hooked into Norfolk to include precincts with a high percentage of minority voters

Source: Congressman Bobby Scott, District Map

In Richmond, the redistricting also moved Democratic voters out of the adjacent Seventh District represented by Republican Rep. Tom Bliley at the time, easing his re-election.

Bliley, a former mayor of Richmond, had been elected from the Third District in the 1980's when it was centered on the state capital and its suburbs. The Democrat-controlled General Assembly in 1991 redrew the district's boundaries after the 1990 Census and the eastern edge of Richmond, with a high percentage of black voters, was incorporated in the new majority-minority Third District. The predominantly-white precincts in the west end of the city, the suburbs of Chesterfield, and several counties stretching up the colonial-era "mountain road" (US 33) to the Blue Ridge, were included in the re-drawn Seventh District.

in 1999, the Seventh District for US House of Representatives stretched from the West End of Richmond to Culpeper

Boundaries of the Seventh District were designed to create a safely-Republican seat and the Third District was intended to be a safe seat for Democratic candidates. However, the Democrats in the 1991 General Assembly who drew the boundaries were not being generous or even-handed with their Republican opponents.

The new Seventh District boundaries did not include the home of the incumbent Republican member of Congress, Rep. George Allen. Most of the area represented by Rep. Allen was transferred into the Tenth District represented by Republican Rep. Frank Wolf. The 1991 redistricting of the Seventh District was a partisan exercise that forced incumbent Rep. Allen to run against a fellow Republican incumbent in 1992, if he wanted to stay in the US House of Representatives.

Rep. George Allen from Charlottesville left the U.S. Congress, while Rep. Tom Bliley from Richmond's suburbs won the new Seventh District seat. Just as the Democrats had expected, the redistricting succeeded in forcing one Republican out of office... but the maneuver backfired. George Allen ran for governor in 1993, served for four very popular years, then defeated Senator Charles Robb in the November, 2000 election. The Republican party took control of the House of Delegates and State Senate in 1999, and Allen's election gave them control of all five statewide offices in 2001.

After the 2010 Census, the boundaries of Virginia's 11 districts for the US House of Representatives had to be re-aligned again so there was an equal number of people in each district, adjusting for shifts in population over the last decade. State and local election district boundaries were also modified in a parallel redistricting process.

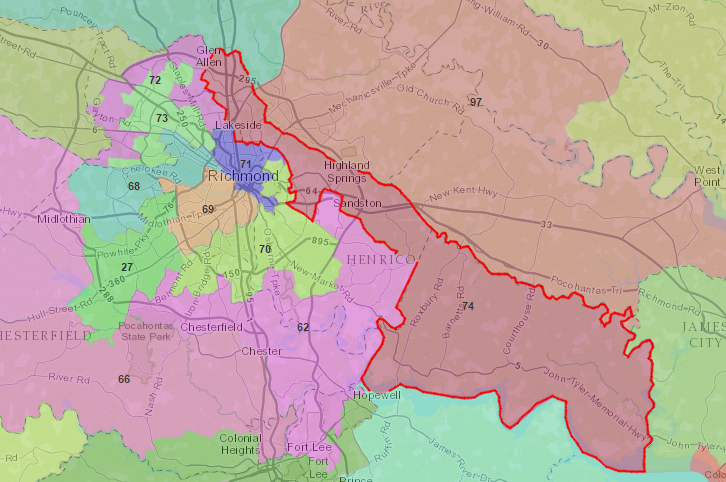

The 2011 General Assembly redrew electoral boundaries and retained the odd shape of the Third Congressional District to ensure that a majority of voters in that one district were black. The boundary change moved conservative voters in New Kent County out of the Third and into the Seventh district, increasing the potential for a Democrat to continue to win the Third District by even greater margins.

Virginia's only black member of Congress, Rep. Bobby Scott, was re-elected easily in 2012 and 2014. Just before the 2014 election a Federal court ruled that the boundaries were unconstitutional. Concentrating minorities in just one district diluted their voting power, and the judges ruled (in a split vote) that the boundaries were based on illegal racial gerrymandering rather than legal incumbent protection.13

a panel of Federal judges ruled in 2014 that the Third Congressional District boundaries (as drawn in 2011, shown above) were intended to dilute the votes of minorities and violated the Voting Rights Act

Source: Division of Legislative Services Current District Maps, Third Congressional District

The remedy, according to the Federal court, was to redraw the boundaries in 2015 in time for the 2016 election to the US House of Representatives. The decision was appealed, blocking changes to the Third Congressional District boundaries during the appeals process.

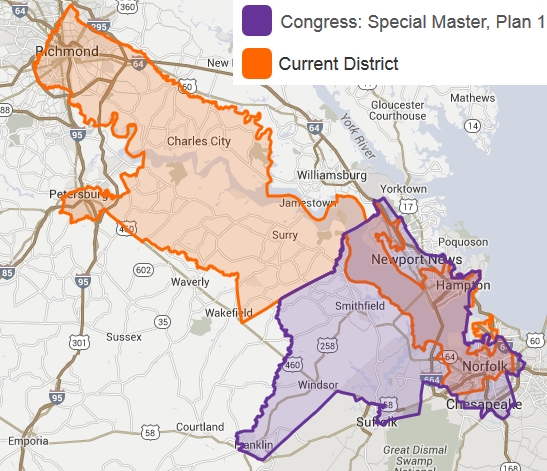

In late 2015, the special master appointed by the Federal court proposed two plans, both of which proposed more-compact district boundaries so voters in the Richmond-Jamestown portion would be removed from the Third District. The plans also proposed revisions to the boundaries of the First, Fourth, and Seventh District to reduce the racial imbalance in the Third District.14

A panel of three Federal judges adopted a plan that moved one million voters between districts. The shift of voters living in Petersburg and Richmond from the Third to the Fourth District altered the racial composition of the Fourth District, from 32% African-American to 42% African-American. The City of Chesapeake was split, moving the northern half from the Fourth into the Third District.

a special master, appointed by a Federal Court to revise boundaries of US House District 3, proposed in late 2015 to strip voters on the northwestern edge (between Jamestown-Richmond) and add voters on the southwestern edge from the adjacent Fourth District

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, US House of Representatives District 3 - Special Master, Plan 1

The home of the incumbent US Representative from the Fourth District, Rep. Randy Forbes, remained in the Fourth District. Rep. Forbes was a Republican who judged that re-election would be substantially harder in his revised Fourth District, which now included much of Richmond and Petersburg and less of Hampton Roads.

A new option opened up for him when Rep. Scott Rigell in the adjacent Second District decided to retire. In early February, 2016, before the Supreme Court ruled on an appeal of the decision made by the three-judge panel, Rep. Forbes announced that he would run for election in the Second District. He still lived in the Fourth District and did not move, but the law only required that a candidate live within the state of Virginia.15

Rep. Randy Forbes entered the race with a substantial advantage in name recognition and cash on hand after serving for 16 years in the US House of Representatives. He served on the House Armed Services Committee, a key position for the Hampton Roads region with so many active and retired military personnel.

Despite his status as an "incumbent" and despite spending 10 times more than his opponent ($2 million vs. $200,000), Rep. Forbes was defeated in the June, 2016 Republican primary by a member of the Virginia House of Delegates who physically resided within the Second District boundaries. The winner of the primary, a former SEAL and Iraq War veteran, successfully portrayed Rep. Forbes as a "coward" and "deserter" from his home Fourth District. Scott Taylor went on to win the seat in November, 2016, so the political party representing the Second District did not change as a result of the revised boundaries.

Rep. Forbes' decision to run in the Second District created an open seat in the Fourth District, greatly increasing the potential for a Democrat to win there. It also created a similar situation of candidates competing for election to the US Congress to serve a district in which they did not live.

Two Democratic and two Republicans sought their party's 2016 nominations to represent the Fourth District, and only one of the candidates already lived within the new boundaries. She did not win the primary, guaranteeing that Virginia would elect a new member of the US House of Representatives who did not live in the district he would represent.

In November 2016, Democratic candidate Donald McEachin won the race, so the redistricting resulted in a shift in the party representing the Fourth District. Rep. Bobby Scott was re-elected in the altered Third District, so the result of re-districting was to double the number of African-Americans representing the state in the US Congress. Rep. Scott closed his Richmond office after the election, because he no longer represented any part of Richmond, Petersburg, or Charles City, Henrico, Prince George and Surry counties.

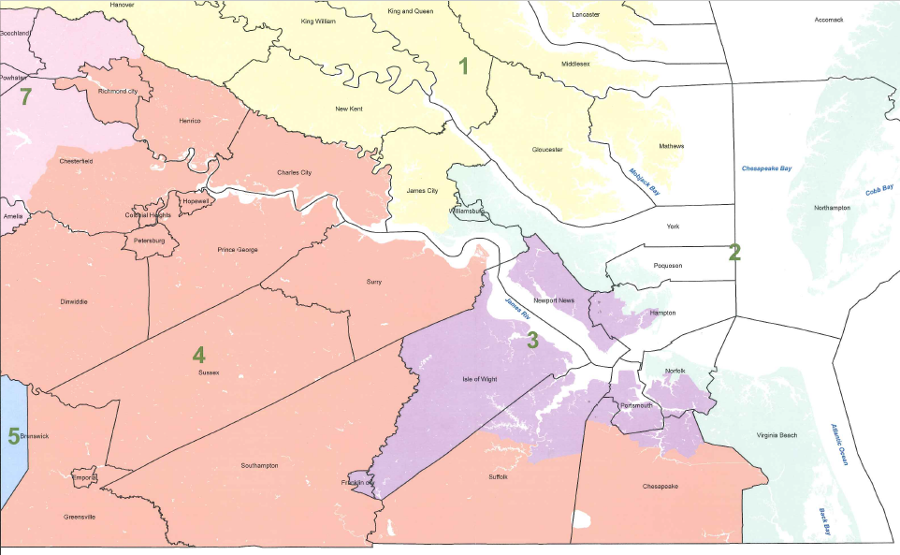

in January 2016, the panel of three Federal judges chose new boundaries (shown above) for US Congressional Districts

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Current Congressional Modification 16 Plan

As part of the 2016 court-ordered redistricting, New Kent County was shifted from the Seventh District to the First District. That county had been added to the Seventh District in 2011, and its more-conservative Republicans led to the unexpected defeat of House Majority Leader Rep. Eric Cantor in the 2014 Republican primary.

In the 2018 election, Democrats recognized that the boundary shifts made Rep. Dave Brat more vulnerable. The Democrats made the Seventh District a key target, and Rep. Brat was defeated by 6,587 votes.

An analysis by the Virginia Public Access Project examined votes for Corey Stewart, the Republican candidate for US Senate in the 2018 race. The analysis suggested that the precincts removed from the Seventh District would have generated 9,885 votes for Rep. Brat, if people in those precincts had been able to vote for the incumbent Republican representing the Seventh District. Court-ordered redistricting may have affected the results of the 2018 election.16

boundary changes to the Seventh District removed heavily-Republican precincts, helping the Democratic candidate defeat Rep. Dave Brat in 2018

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Dave Brat: A Casualty of Court Decision?

A separate lawsuit was filed at the end of 2014 to contest "racial gerrymandering" at the state level, seeking a revision in boundaries for 12 districts (out of 100) in the House of Delegates. The basic claim was the same as in the Federal lawsuit. The boundaries were unconstitutional because they discriminated based on race, and when the General Assembly created new boundaries for House of Delegates districts after the 2010 census, black voters had been illegally concentrated in a dozen districts.

The boundaries created districts with a voting age population that was at least 55% African-American, packing them into a few areas in order to enhance the election potential for Republican candidates in other districts. In October 2015, a panel of three Federal judges in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia ruled 2-1 that the boundaries were constitutional.

It determined that the racial characteristics of one district was validly considered. In the other 11 districts in Hampton Roads and near Richmond, the focus on racial balance within districts did not overwhelm the traditional considerations during redistricting. That meant no revisions were required for those 12 General Assembly districts, but the US Supreme Court agreed in June 2016 to hear an appeal.

That kept open the possibility that the boundaries of 11 state legislative districts could be redrawn before the 2017 elections for the House of Delegates. The process ended up stretching into 2018, in a case finally known as Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections.17

a 2014 lawsuit claimed that redistricting after the 2010 census created a dozen districts (shown in red) where minority-race voters who tended to vote for Democrats were packed into urban districts, to facilitate the potential election of Republican candidates in suburban districts

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the boundaries of 12 House of Delegates districts, including District 74 (outlined above) were ruled to be constitutional in a 2015 court decision

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

During the 2011 redistricting process, the House of Delegates was controlled by Republicans. The Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General were also Republicans, but the Democrats had a 22-18 majority in the State Senate. The split in control forced compromise when defining new boundaries for the 100 districts of the General Assembly's House of Delegates and the 40 districts for the State Senate.

The Democrats in the Democrat-controlled State Senate determined the boundaries of new State Senate districts and Republicans in the Republican-controlled House of Delegates determined the boundaries of new House districts. The party in control of each house ensured its incumbents would be protected, while making it harder for the other party to win future elections.

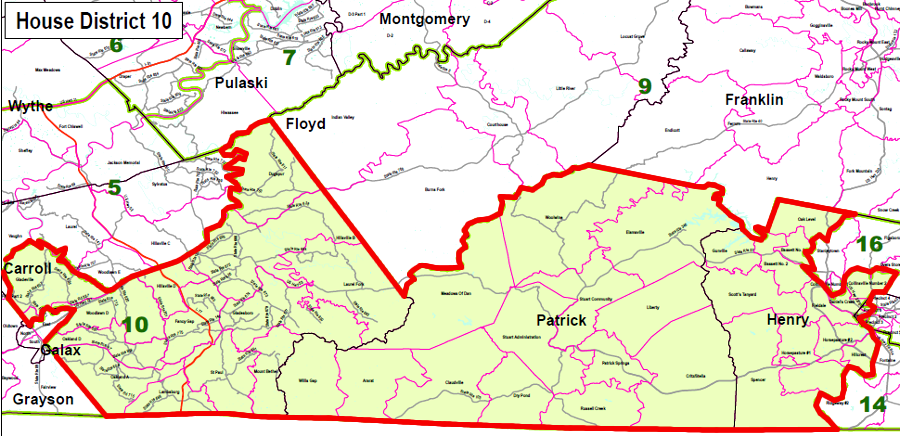

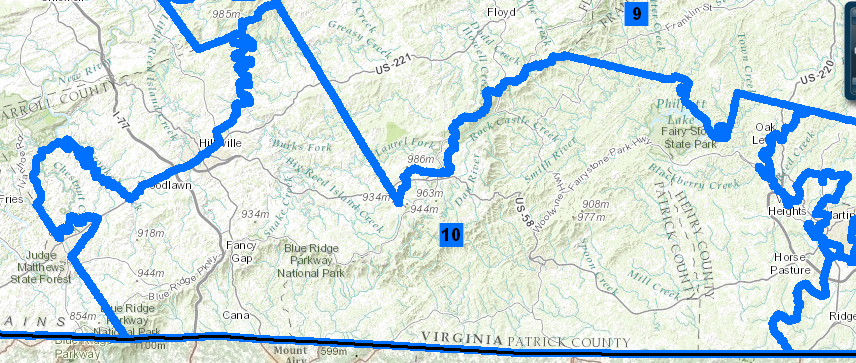

The final redistricting plan did not protect the top Democrat in the House of Delegates. Ward Armstrong represented the 10th District in the House of Delegates and served as Minority Leader for the Democrats. It was his fate that Democrats who controlled the State Senate focused on Senate district boundaries, while Republicans controlled the map for the House of Delegates in which Ward Armstrong served.

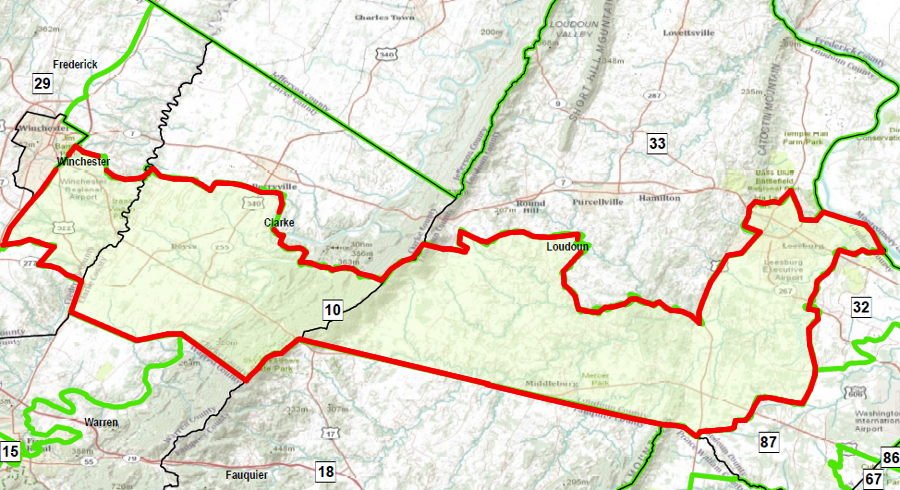

The Republicans redrew Ward Armstrong's 10th District boundaries dramatically. The territory within his district was split between adjacent House districts, and a new 10th District was created far away in Loudoun, Clarke, and Frederick counties to accommodate population growth in the Northern Virginia suburbs. The Richmond newspaper used a hunting analogy to describe the political process that abolished Armstrong's district:18

Armstrong's house was placed in the 16th District. Armstrong did not wish to oppose the incumbent representing that district, even though he was a Republican, so he moved to another house and ran for a seat in the State Senate. Despite raising over $1 million, he was defeated and his political career ended.

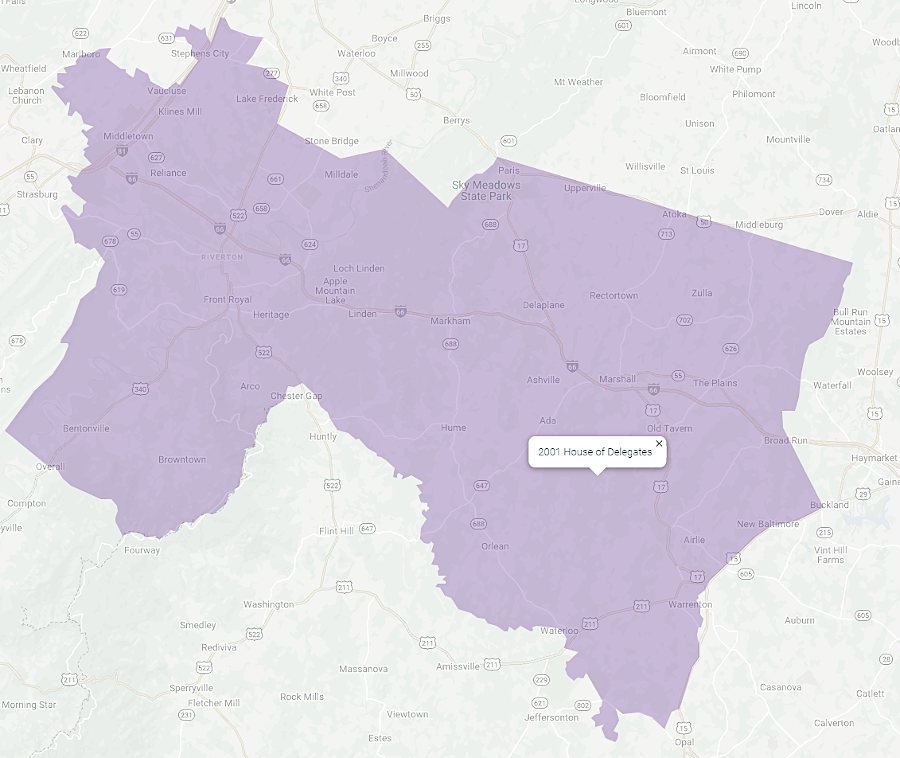

the top Democrat in the House of Delegates, Del. Ward Armstrong, represented the 10th District in Southside Virginia before the 2011 redistricting for the Virginia House of Delegates

Source: Division of Legislative Services - 2010 District Maps, 10th District

the 10th District in the House of Delegates, represented by the Minority Leader of the Democratic Party prior to the 2011 redistricting, was located in Southside Virginia

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Division of Legislative Services, 2001-2010 House Districts

there was no 10th District in Southside Virginia after the Republican-controlled 2011 redistricting for the Virginia House of Delegates

Source: Division of Legislative Services - Current District Maps, 9th District

in the 2011 redistricting, the 10th District in the House of Delegates was moved far away to Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley... eliminating the opportunity for the Minority Leader of the Democratic Party to run for re-election

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Current District Maps - House of Delegates District 10

In 2013, the Republican Party attempted to redistrict the State Senate boundaries without waiting for another census. The State Senate at the time was evenly divided, with 20 Democrats and 20 Republicans. The Republicans waited, successfully keeping their scheme a secret, until one Democratic State Senator left Richmond to attend President Obama's second inauguration. With a 20-19 majority that day, the redistricting bill was brought up and passed immediately in a surprise move.

The new map would, according to Democrats, make it easier for Republicans to capture up to six seats held by Democrats and gain solid control over the State Senate by packing Democratic voters into already-Democratic districts and by adding precincts with more Republican voters to competitive districts. A Washington Post editorial labeled the proposal a "bald-faced power grab."19

In response, the Democrats angrily argued that redistricting outside the normal 10-year timeframe was unfair. Rather than hope a court would rule the mid-cycle redistricting to be illegal, the State Senate Democrats bounded together and used a political strategy: they threatened to block the Republican governor's signature bill to raise taxes to fund new transportation projects.

The Republican Speaker in the House of Delegates, Del. Bill Howell, and Republican Governor Bob McDonnell decided that the long-term benefits of "fixing transportation" were more important than the passing a surprise redistricting bill that might give Republicans control of the State Senate in 2015. The Republicans had a super-majority in the House of Delegates, but the Speaker resisted strong pressure to make a partisan decision and even considered running for governor as an independent that Fall.

The Speaker of the House of Delegates ruled the redistricting bill was out of order. Democrats in the General Assembly then helped pass Gov. McDonnell's bill to raise transportation taxes.

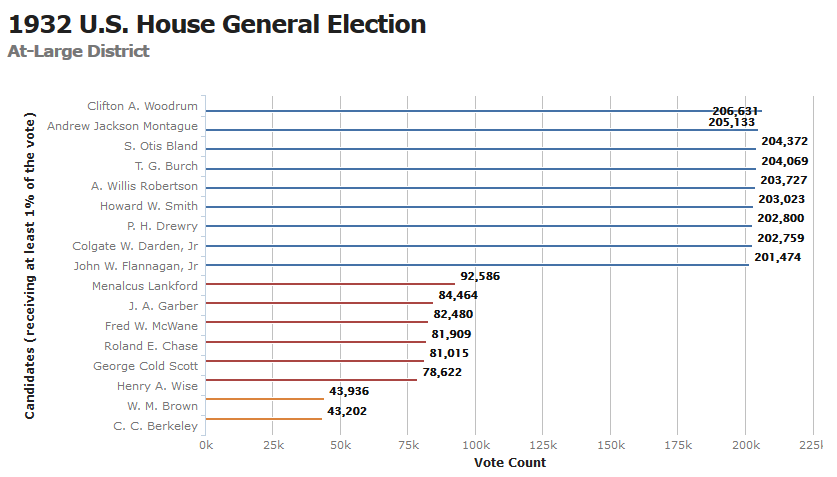

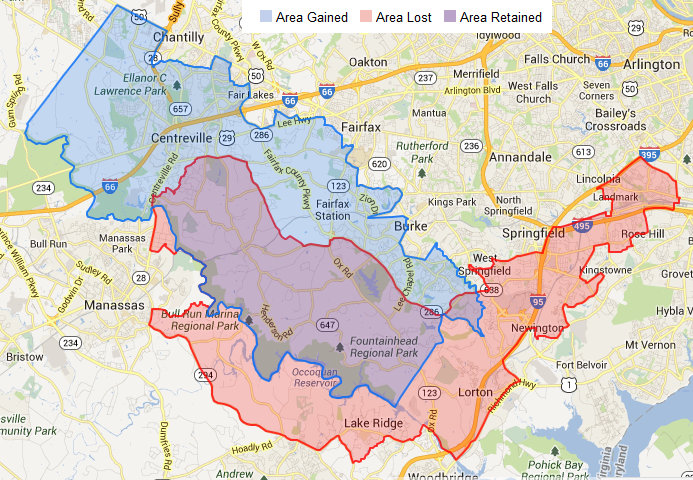

in the proposed 2013 redistricting, State Senate District 39 (represented by Democrat George Barker) would have been modified so Democratic precincts along Route 1 would have been replaced by Republican precincts near Centreville

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, State Senate District 39

In 2014, the Republicans used a different maneuver to gain control of the State Senate. State Senator Phil Puckett resigned in June, anticipating that leaving the legislature would clear the way for his daughter to be elected by the General Assembly as Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court judge. In addition, Puckett may have expected that he would be chosen very soon after his resignation for the high-paying job as executive director of the Tobacco Indemnification and Community Revitalization Commission.

Puckett's resignation left the State Senate with only 19 Democrats vs. 20 Republicans. The tie-breaking Lieutenant Governor, a Democrat, no longer had a tie to break when Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe proposed expanding Medicaid. That blocked McAuliffe's effort to implement the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare") and triggered investigations about whether the bargaining to get Puckett to resign/stay qualified as illegal political corruption.

The FBI declined to pursue inquiries, and a Republican was elected in the 38th District to replace Puckett. The Republicans gained clear control of the State Senate for the 2015 General Assembly without having to use a mid-cycle redistricting scheme. The 2015 General Assembly elected Puckett's daughter to serve as a judge, but the political backlash was intense enough that Puckett was not hired as executive director of the tobacco commission.20

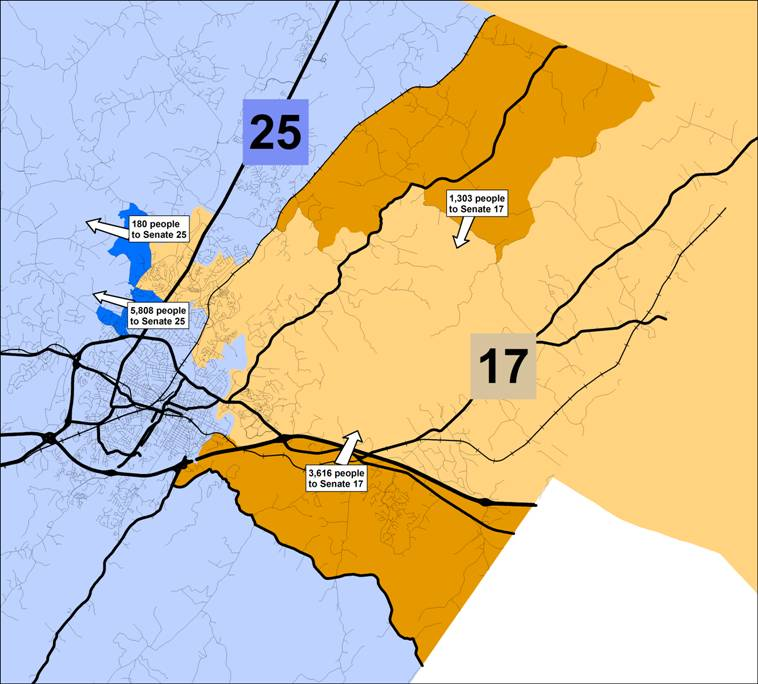

A different mid-cycle redistricting was proposed in 2015 by one Republican incumbent in the State Senate. The boundary change would eliminate some problems created in the 2011 redistricting, which had established boundaries for the 17th and 25th State Senate districts that ignored the boundaries of pre-existing voting precincts. In Albemarle County, the Jouett, Stony Point, and Woodbrook precincts were three of 224 "split precincts" created in the 2011 redistricting, which increased confusion among voters and burdened local jurisdictions with $10 million in costs to make adjustments.21

The proposed redistricting in 2015 would eliminate that confusion in two of the three precincts, but not consolidate the Woodbrook precinct. In addition, the proposed new boundary lines would move the entire Georgetown precinct from the 17th to the 25th District, and the entire Stone Robinson from the 25th to the 17th District.

The net effect would be to increase the number of Republican-leaning voters in the 17th District, while moving Democratic-leaning voters out of that district. The boundary shifts for 11,000 residents in four precincts was predicted to increase the re-election potential of the Republican incumbent in the 17th District, who had defeated a long-time Democratic incumbent in 2011 by only 226 votes. The changed boundaries would add a net of 600 Republican votes to the 17th District. (The 25th District, which would gain Democratic-leaning voters, was already represented by a Democratic incumbent.)22

The bill (SB 1237) was passed by both houses of the General Assembly on predictably party-line votes with just Democrats opposed, and sent to the governor. Governor McAuliffe vetoed the bill, along with five others passed in the 2015 General Assembly that would have altered district boundaries, stating:23

in 2015, the Republican incumbent in State Senate District 17 proposed realigning boundaries with District 25, moving Republican voters into the 17th District and moving Democratic-leaning voters out of it

Source: C'ville, Reeves' Senate district swap prompts claims of political maneuvering

The Republican-controlled General Assembly and the Democratic governor clashed in 2016 over another redistricting law, this time involving the city of Fredericksburg.

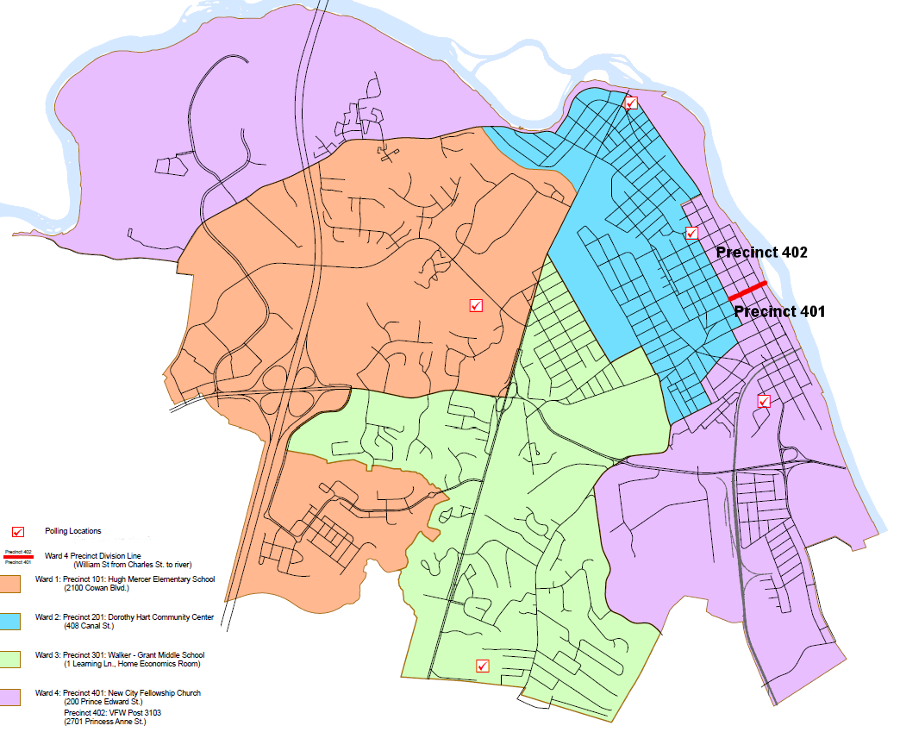

That city is divided into four wards for city council elections. The mayor and two members of the council are elected at-large, with the winners determined by who gets the greatest number of votes from the 16,000 registered voters within the entire city. Four members of the city council are elected based on votes within individual wards, ensuring that those geographic regions each have a representative.24

Three wards have one polling place, but Ward 4 has two. In the 2011 redistricting, a portion of Ward 4 was placed in the 88th District for the House of Delegates, and the rest was placed in the 28th House District. Every two years, when there are elections for the House of Delegates, the registrar has to staff an extra precinct in Ward 4 so voters will see the choices for their district.

the 2011 redistricting map placed Fredericksburg's Wards 1 and 3 in the 88th House District, Ward 2 in the 28th House District, and divided Ward 4 between the 88th and 28th districts

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services - Current District Maps, HB 5005 House District 88

In 2016, both districts were represented by conservative Republicans. The delegate from the 28th District was William Howell, the powerful Speaker of the House. To simplify the voting process, the two agreed to move all the voters in Precinct 401 into the 28th District. Roughly 500 voters would be transferred, based on the 2015 election for the House of Delegates.

William Street (red line) is the precinct boundary that divides the two portions of Ward 4 in Fredericksburg

Source: City of Fredericksburg, Map of Wards

As described by Speaker Howell, the bill was just a technical adjustment:25

Using the same justifications as in 2015, Gov. Terry McAuliffe vetoed this redistricting bill as well:26

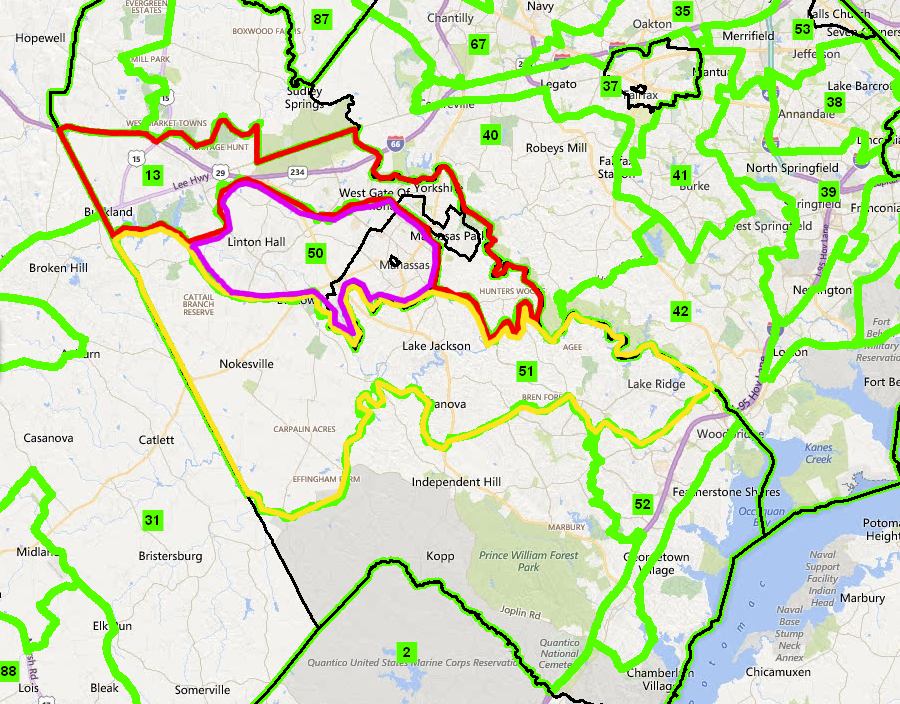

The governor's veto did not end the potential for the 88th House District boundaries to be altered through mid-cycle redistricting. The redistricting advocacy group OneVirginia2021 asked the Richmond Circuit Court to force creation of a new map for 11 districts prior to the 2017 state elections based on a separate objection - "compactness."

OneVirginia2021's Vesilind v. Virginia State Board of Elections lawsuit claimed that boundaries of five House of Delegates districts and six State Senate districts (House Districts 13, 22, 48, 72, and 88 plus Senate Districts 19, 21, 28, 29, 30, and 37) violate Article II, Section 6 of the Virginia Constitution:27

In March, 2017, the state judge declined to order a redistricting based on the "compactness" criterion. He ruled that the General Assembly had discretion to draw the boundaries, and the court needed stronger evidence before overruling the legislative branch. The Virginia Supreme Court upheld that ruling in May, 2018. It ruled that compactness was a factor in drawing district boundaries, but did not exclude consideration of partisan and incumbent-protection factors.

The court judged that the state constitution did not give compactness priority over other considerations:28

the lawsuit filed by OneVirginia2021 claimed the 88th House District is one of 11 General Assembly districts that are not compact enough to be valid under Virginia's constitution

Source: OneVirginia2021, Compact

OneVirginia2021 declared it would pursue an amendment to the state constitution to prohibit partisan gerrymandering, since the courts had failed to support its interpretation of existing law. Such an amendment would require approval by two sessions of the General Assembly, plus ratification by the voters in a general election.29

The Virginia Supreme Court decision was not the final decision. One more legal effort remained before the end of the 2014 lawsuit.

The US Supreme Court had directed the panel of Federal judges to reconsider its earlier finding in Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections. In June, 2018, the panel of Federal judges ruled in another 2-1 decision that the 11 House of Delegates districts had been defined based on an unconstitutional prioritization of race. The majority of judges rejected the claim that a minimum 55% black voting age population in a district was necessary for black voters to elect their preferred candidates under the mandate of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The General Assembly was ordered to redraw the district boundaries by October, 2018. That way, the new boundaries would be defined over a year before the 2019 election. Redrawing boundaries of 11 districts could affect the demographics of adjacent districts, affecting the 2019 elections in perhaps 30% of Virginia's 100 House of Delegates districts.

Black voters had been packed into those 11 districts, with boundaries drawn so a minority of the residents would be white. The demographics ranged from 59-63% black. All were represented by Democrats, elected in 2017 in landslides ranging from 67-88% of the vote. In the 22 adjoining districts, voters had elected 15 Republicans and seven Democrats in 2017. The 15 districts that elected Republicans ranged from 11-34% black, and the seven districts that elected Democrats ranged from 8-56% black.30

The Republican Majority Leader of the House of Delegates appealed to the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, requesting a delay in redistricting until the Supreme Court ruled on an appeal of the District Court's decision. That appeal, Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, added to the House of Delegates' legal costs, which already exceeded $4 million, to defend the General Assembly's initial boundaries as drawn in 2011. The Attorney General for Virginia dropped his support for the appeal, after spending $877,000 on the case.

Despite the Federal District Court ruling, there was no guarantee that the mandate to redraw boundaries would be implemented prior to the 2019 election. Redistricting could have been delayed past the 2019 election date by another appeal to the US Supreme Court. Legal proceedings stretched over a decade could end up triggering no redistricting.

The House of Delegates appeal caused the Minority Leader in the House of Delegates to complain:31

the Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections case involved 11 House of Delegates districts near Richmond and in Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, Ruling Could Impact 1 in 3 House Districts

The House of Delegates appeal to the Federal court was rejected, and the court ordered the General Assembly to produce a new map of boundaries. The legislature failed to do so.

Plans to call a special session of the General Assembly in October, 2018 to redraw 11 district boundaries were cancelled after Republicans and Democrats could not agree and proposed different maps. Republicans would not accept the Democratic map, and Governor Northam promised to veto the Republican proposal. The Federal District Court then appointed a California professor as Special Master to redraw the election district boundaries.

The Special Master had previously redrawn the Third Congressional District boundaries. Those new boundaries caused the incumbent Republican member of the US House of Representatives, Rep. Randy Forbes, to run for office in the Second District rather than in the Third District where he lived. He lost in the Republican primary, and was replaced in the Third District by a Democrat.

The new boundaries proposed by the Special Master to correct the boundaries of the 11 contested districts and redistribute the minority-race voters were released in January, 2019. The new map ended up affecting 26 districts.

Analysis by the Virginia Public Access Project indicated that six Republican incumbents ended up in redrawn districts with a majority of Democratic-leaning voters, based on how people voted in the 2012 presidential election.

Rep. David Yancey, who won re-election in the 94th District in 2017 only after the vote ended in a tie and his name was pulled from a bowl as the winner, was required to run in 2019 in a district that dropped from 48% to 41% Republican. However, the home of his 2017 opponent was shifted to the 95th District. She ended up moving to another home in order to stay as a resident in the 94th District, a requirement to qualify as a candidate to run again against Del. Yancey again in 2019.

The apartment complex where voters were mistakenly given ballots for a separate district in 2017, perhaps affecting the tie vote, was left within the redrawn boundaries of the 94th District. The changed boundaries did eliminate the "split precinct" and reduced the potential for voters to be given the wrong ballot.

Based on the new map proposed by the Special Master, 14 Democratic incumbents ended up with more Republicans in their districts but none would have to run for re-election in a district with a Republican majority. The Virginia Public Access Project concluded that only one Democratic-held seat (District 93 in Newport News) would become harder to defend.

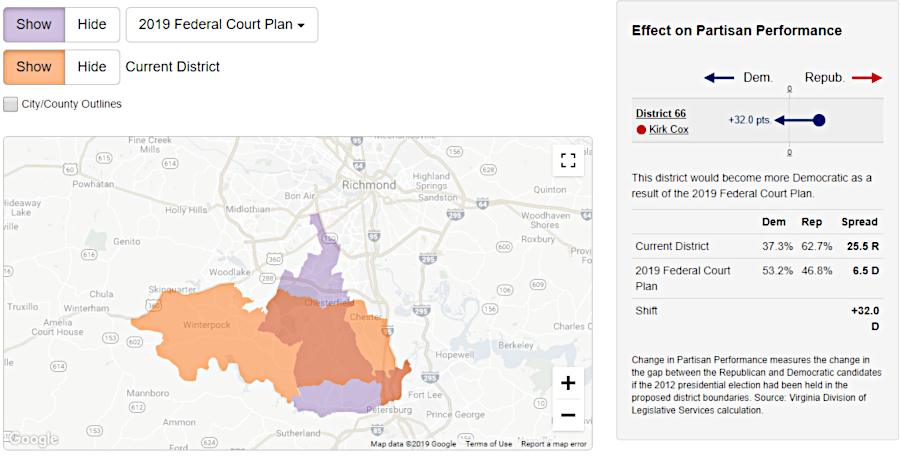

An estimated 425,000 registered voters were assigned to new districts. The districts of two top Republican leaders were affected significantly. Boundaries of the 66th District, represented by the Republican Speaker of the House of Delegates Kirk Cox, were revised to drop Republican-leaning voters from 63% to 47%. The 76th District, represented by the chair of the House Appropriations Committee, shifted from 56% to 42% Republican.32

the Special Master proposed redrawing boundaries in 2019, substantially altering the re-election chances of the Republican incumbent serving as Speaker of the House of Delegates

Source: Virginia Public Access Project, House of Delegates District 66

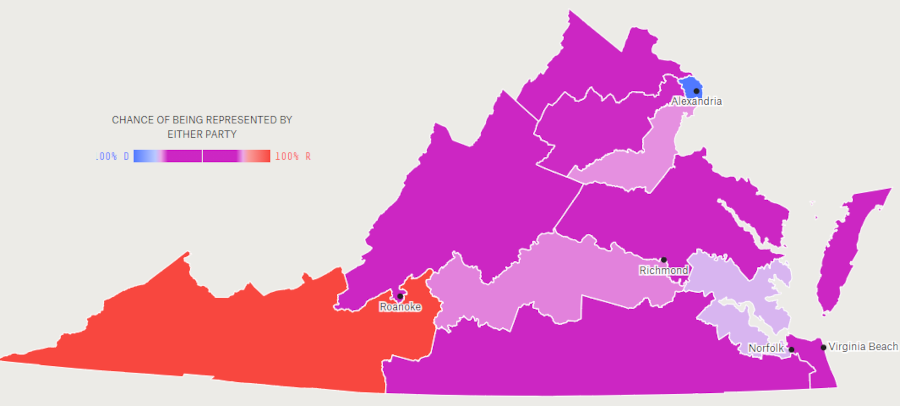

When the Special Master released his maps, Republican control of the House of Delegates was slim with only 51 of the 100 delegates. In the 2017 elections, Republicans had won only 44% of the total vote but 51% of the House of Delegates districts. How the Democratic voters were packed into a minority of districts was clearly significant.

One obvious effect of the redrawn lines, other than correcting for racial bias as required by the Federal court, was that the potential for the Democrats to gain a majority of the House of Delegates in the 2019 election had been enhanced. That conclusion was one factor in the decision of the Republican-controlled House of Delegates to request the Supreme Court block the redistricting map proposed by the Special Master.

The US Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal in November 2018, but it declined to issue a stay blocking the special master from proposing new boundaries. The court's final decision was not issued until after the June 11, 2019 primaries.

The delay created the potential that the Special Master's maps would be used for district boundaries for the primaries and conventions that nominated candidates, but boundaries could be changed after the votes were counted in June. In a worst-case scenario (if district boundaries were scrambled by a Supreme Court decision after candidates have been chosen in the June, 2019 primaries), a candidate nominated in June 2019 could end up running for a seat outside their district of residence in the November general election.

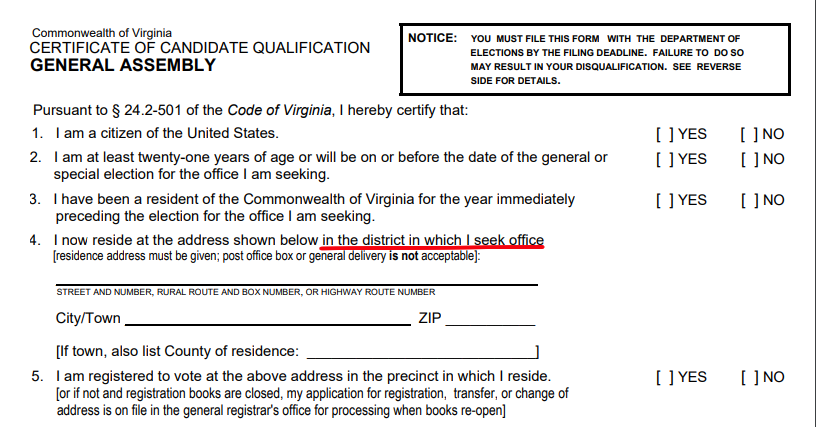

Virginia law required that candidates live within their district when they file their "Certificate of Candidate Qualification" for a General Assembly seat. It was less clear if a candidate/incumbent must remain a resident of that same district until the next election cycle required a new filing.

In the end, the US Supreme Court issued its ruling six days after the primary. In its 5-4 decision on Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill, the court declared that the Virginia House of Delegates lacked standing to sue. That left the Special Master's maps unchanged for the general election.33

In the November 2019 general election, voters chose Democrats to replace Republicans in four House of Delegates districts affected by the redistricting and Democrats gained control of that chamber of the General Assembly. The #2 Republican in the House of Delegates, Majority Leader Todd Gilbert, blamed "liberal judicial gerrymandering" for the switch in control. The chair of Virginia's legislative black caucus, Del. Lamont Bagby, agreed that the redistricting was a factor:34

candidates for the General Assembly must certify they live within the House of Delegates/State Senate district

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Certificate of Candidate Qualification

Political parties anticipated that Supreme Court decisions on different redistricting cases might redefine the legal criteria for drawing district boundaries before the 2020 Census results are announced. In the end, the court created no new criteria to shape new boundaries for the 2021 elections in all 140 General Assembly and the 11 US House of Representatives districts, or for districts for local offices.

In particular, the Supreme Court declined to create new limits on partisan bias when drawing election district boundaries. In the 5-4 Rucho v. Common Cause decision in June, 2019, the nine justices determined that Federal courts could not set any limits on partisan bias used during redistricting:35

if 11 House of Representatives districts were redrawn to maximize competitiveness, two districts would remain "easy wins" for Republicans and Democrats

Source: Five Thirty Eight, The Atlas Of Redistricting: Virginia

OneVirginia2021 recognized there was a separate path to limiting the traditional gerrymandering process, not relying upon the courts to force redistricting. The November, 2019 elections for 100 Delegates and 40 State Senators determine the partisan makeup of the legislature, and the people who will determine new district boundaries after the 2020 Census. Political action, not just legal action, could force a change in the traditional redistricting process that will affect elections in the 2021-2031 decade.

Pressure for redistricting reform comes from various directions. Some who feel the last redistricting process was "unfair" seek to alter the process of redrawing boundaries in order to prevent a repeat in 2021. Other partisan advocate anticipate their party will be in control during the 2021 General Assembly, and preserving the current process would provide a decade of extra legislators.

the 50th House District (outlined in purple) is clearly compact, and the OneVirginia2021 lawsuit based on compactness challenged the constitutionality of House District 13 (outlined in red) to the north but not House District 51 (outlined in yellow) to the south

Source: Virginia Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting Plans

One impact of the traditional process, allowing incumbents of the majority party in the House of Delegates and State Senate choose their voters, is that few elections are close contests. Voters are packed into districts to ensure the winner will be Republican or Democrat, no matter which political party is in charge during the process. If Democrats are in charge, as they were in the State Senate in 2011, then the redistricting process will increase the number of districts designed to elect Democrats. If Republicans are in charge, as they were in the House of Delegates in 2011, then the boundaries will be drawn to elect more Republicans.

As a result, prior to the 2015 election an assessment of the 2013 results for the House of Delegates noted:36

In 2019, the General Assembly approved a proposal to create a 16-member independent commission to draw new boundaries after the 2020 Census. The proposal would be effective only if approved again without modifications by the 2020 General Assembly, and then by the voters in a November 2020 referendum. A non-government organization, OneVirginia2021, was the driving force that organized citizens and a wide range of former elected officials from both parties to advocate for an independent commission.

The Executive Director of OneVirginia2021 identified why an independent commission was finally adopted in 2019, after rejection in previous legislative sessions:37

Under the proposal, the independent commission - rather than the 140 legislators and the governor - would draft boundaries for all state and Federal offices. The General Assembly could reject the first draft, but if it rejected the second draft then the Virginia Supreme Court will draw the districts. The governor would no longer have the ability to approve or reject the proposal.

The fundamental objective of the proposed commission was to minimize the partisan slant on redrawing boundaries. Eliminating partisan preferences was unrealistic, but the redistricting process was designed so just Democrats or Republicans could not control the decision and impose maps not acceptable to the other party.

The 2019 General Assembly was almost evenly balanced. Republicans had a 51-49 majority in the House of Delegates and a 21-19 majority in the State Senate. All 140 seats were up for election in November, 2019. The Democrats had gained 15 seats in the House of Delegates in the 2017 "blue wave" election, but during the 2019 General Assembly session they were stunned by accusations of racial insensitivity and sexual assault against the Democratic governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general. Neither party felt confident that they would be able to win a strong majority in 2019 and dominate the redistricting process in 2021.

OneVirginia2021 had proposed a selection process for members of a 10-member commission that started with citizens volunteering to serve. As proposed in SJ 274, five retired circuit court judges would winnow the list to 22 candidates. Five would be Democrats, five would be Republicans, and 12 would not be affiliated with any political party. Partisan leaders in the General Assembly would then strike 12 names from the list. Of the final 10 Commission members, three would be Democrats, three Republicans, and four would be unaffiliated.

Party leaders in the General Assembly chose instead to give themselves a greater role in selecting members of a 16-member commission. Eight of the members would be members of the House and Senate, four Democrats and four Republicans. Selection of the other eight members would start with the Speaker of the House, the president pro tempore in the Senate, and the top two leaders of the minority party in the House and Senate creating lists of 16 candidates. Five retired circuit court judges would pick two people from each list, establishing the eight citizen members of the redistricting commission.

Selection of the retired judges could shape the decision process, of course. The final legislation required that four of those judges would be appointed by party leaders in the General Assembly. The other judges would pick the fifth judge.

The political leaders in the House and Senate would then strike names until there were eight remaining. There would be two Democrats, two Republicans, and four unaffiliated members.

To adopt proposed legislative boundaries for the House, the commission would need votes by at least three of the four legislative members of that chamber. The same requirement applied to the Senate redistricting. That requirement was designed so one party could block a redistricting plan perceived as too partisan.

The State Senate approved the redistricting commission unanimously, but in the House of Delegates the vote was 83-15.

Opposition to the proposal came primarily from the Legislative Black Caucus. The redistricting commission would alter the district boundaries drawn in 2011 to enhance the potential of minority candidates, and there was no requirement to create new districts that would offer the equivalent potential.

Minority-majority districts, drawn in the past to pack African-American voters into a few areas and assist in election of African-American candidates, may not be maintained in the proposed 2021 redistricting process. The chair of the caucus noted that there was no requirement for minority representation on the independent commission:38

After the 2019 General Assembly session, Governor Northam vetoed SB 1579, which would have established redistricting criteria for use after the 2020 Census. The standards required creation of contiguous and compact districts, and stated "Consideration may be given to communities of interest..." However, Gov. Northam reaffirmed his alliance with the Legislative Black Caucus in his veto message:39

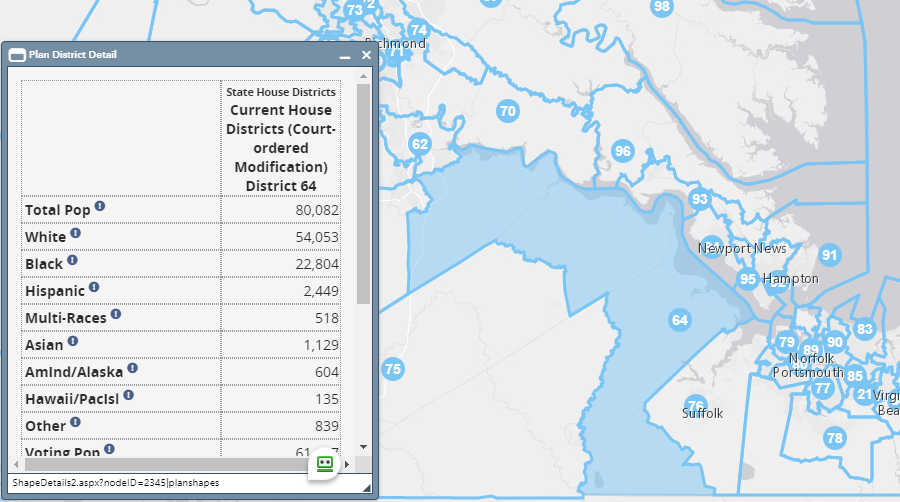

House of Delegates District 64 was 67% white while adjacent District 76 was 50% white, and the Black Caucus worried that 2021 redistricting would alter the population ratios and reduce the potential for electing African-American candidates

Source: Virginia General Assembly, Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting Maps

Political power shifted in the November, 2019 election. Democrats flipped control of both the House of Delegates and the State Senate. With a Democratic governor, they had the power to control the redistricting maps after the 2020 Census.

In the 2020 General Assembly, the State Senate passed the proposed constitutional amendment again by a 38-2 vote. Debate in the House of Delegates continued until he next-to-last day of the session, and Governor Ralph Northam threatened to call a special session if necessary to break the legislative deadlock. Opponents argued that the process would allow two Republicans on the commission to block approval, giving final authority for redistricting to the Supreme Court of Virginia. All those judges had been appointed by a Republican-controlled General Assembly, so approval of the amendment could lead to gerrymandering by conservative judges and threaten the Democratic majorities in the next election..

The final House of Delegates vote in 2020 was 54-46, in contrast to the 85-13 vote in 2019. All 45 Republicans and 9 of the 54 Democrats in the House of Delegates voted to allow the proposed constitutional amendment to appear on the ballot in November, 2020.40

House Speaker Eileen Filler-Corn (D-Fairfax) delayed the vote on the constitutional amendment until the last opportunity. She opposed passage of the amendment, because it did not ensure inclusion of communities of color in the redistricting process to her satisfaction.

The two houses of the General Assembly had planned to pass enabling legislation along with the constitutional amendment. That legislation could establish criteria for the redistricting which would prioritize protection of the hard-earned political power of communities of color. However, the Democrats in the two houses could not get to closure, and the amendment was passed without any enabling legislation.

Senate Majority Leader Dick Saslaw, D-Fairfax, provided a rejoinder to the argument that Republicans on the commission could sabotage its efforts in order for a final decision to be made by Republican-appointed judges on the Supreme Court of Virginia:41

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Census Bureau suspended many field operations and requested the US Congress to allow a delay in delivering the final numbers to July 31, 2021. Virginia officials had expected the population details by early March, which would allow time for drawing new district boundaries and then holding primaries in August. Redistricting delays would affect the elections for the 100 House of Delegates seats, as ell as local elections in counties with magisterial districts and cities with wards.

The 2021 elections for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General would not be affected, since those are statewide offices. The members of the State Senate also would be unaffected by a delay; the state senators had been elected to four-year terms in 2019.

One option for coping with a delayed delivery by the Census Bureau was to hold 2021 House of Delegates elections using the existing district boundaries, which were drawn initially in 2011 and revised by Federal court order in 2019. As in 1981, House of Delegate members could be elected to just one-year terms, followed by redistricting in 2022. Those elected using the 2022 boundaries also would serve just one year, until the 2023 elections.42

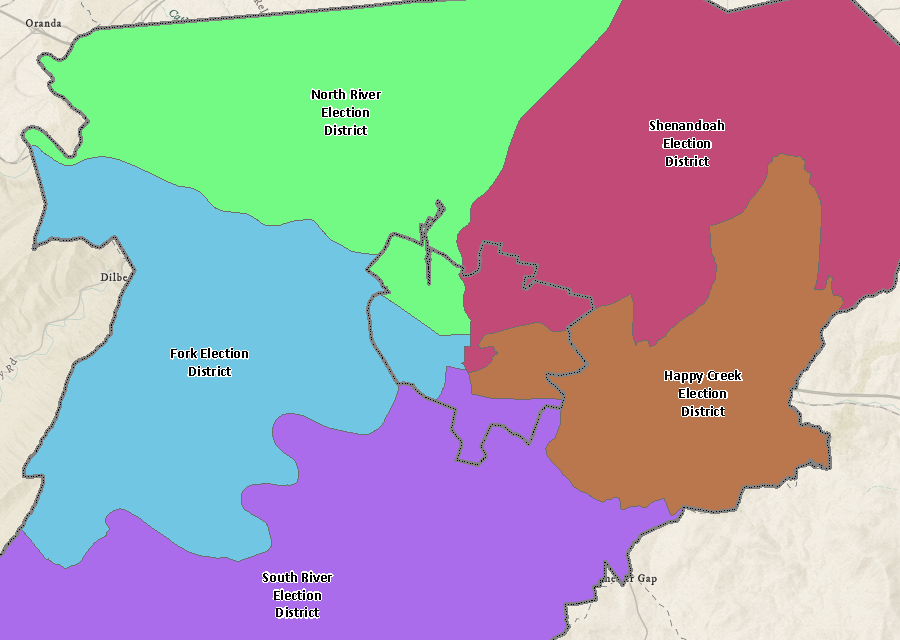

In anticipation of the 2021 redistricting, the mayor of Front Royal proposed that new boundaries should include all of the town in just one House of Delegates district. The 2011 redistricting had divided the town, with portions represented by three different delegates in the 15th, 18th and 29th districts rather than keeping it all within the 18th District. The town was also split into five sections for election to the five-member Warren County Board of Supervisors.

The mayor's interpretation of "compact and contiguous" districts would prioritize municipal boundaries, but the Town Council disagreed and unanimously rejected the proposal. Some councilmembers thought the timing of the request was premature, and others preferred having three delegates looking out for the town's interests in the state legislature. In 2020, all three delegates were Republicans with few disagreements, but one councilmember expressed concern that the town could end up within a district where most voters were in more-liberal, more-Democratic Northern Virginia:43

between 2011-2020, Front Royal was divided between three House of Delegates districts

Source: Virginia General Assembly, Division of Legislative Services, Redistricting Maps

between 2001-2010, all of Front Royal was within the House of Delegates 18th District

Source: Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), House of Delegates District 18

each member of the Warren County Board of Supervisors represented voters in a portion of the Town of Front Royal

Source: Warren County, GIS

The Democratic Party of Virginia (DPVA) decided at its 2020 state convention to openly oppose the redistricting amendment. However, two senior leaders, members of the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus, continued to support efforts by Virginia2021 to get voter approval in November 2020. They commented after the vote:44

Supporters of the amendment advocated under the name FairMapsVA, while opponents adopted a FairDistrictsVA name. Opponents claimed that a "no" vote would stop gerrymandering. If the amendment was rejected, then the Democratic-controlled General Assembly could create a commission to draw "fair" boundaries. The proposed process would prevent judges on the Virginia Supreme Court, who had been appointed by previous Republican-controlled General Assemblies, from choosing the final map.

opponents of the redistricting referendum claimed supporters of racial equity and gun control should vote "no"

Source: FairDistrictsVA, Why Vote No

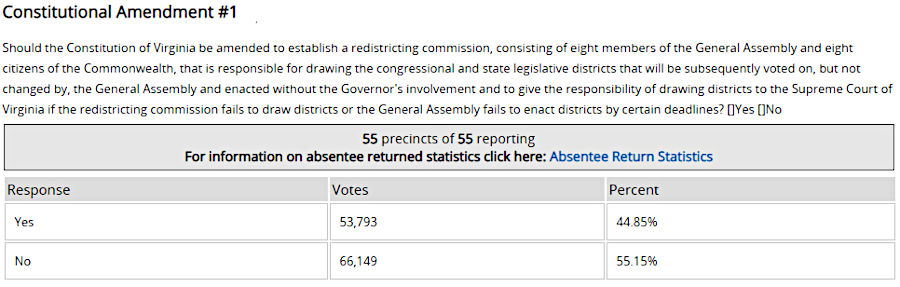

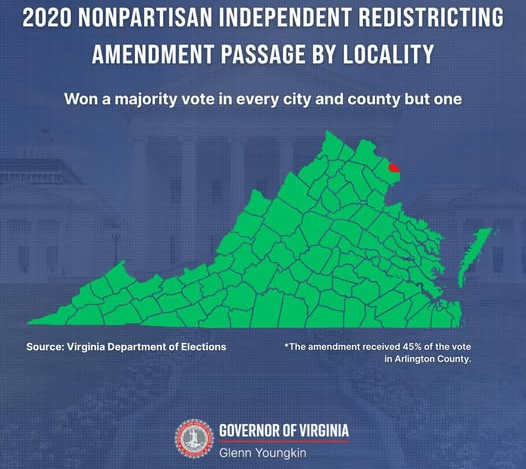

Voters rejected the argument. They supported reducing the influence of the politicians in the redistricting process and 66% voted in favor of the referendum.

Only 45% of the vote in heavily-liberal Arlington County, where in the 2020 presidential race Joe Biden won 80% of the vote, supported the redistricting referendum. The city of Richmond gave Biden the same percentage, but voted 70% in favor of creating the 16-member, bipartisan redistricting commission.

Support and opposition to the amendment did not break along racial lines. The concerns of black Democrats in the House of Delegates were shared by voters in Arlington with a 75% white population, but not in Richmond which was only 45% white.45

the liberal and heavily-Democratic voters in Arlington County rejected the redistricting amendment in 2020, with 55% opposed

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, 2020 November General - Arlington County

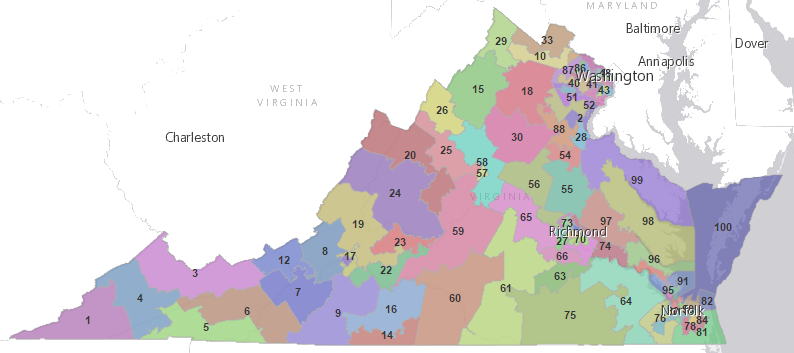

The Virginia Redistricting Commission created after passage of the referendum failed to create a set of maps in 2021. The commission deadlocked in partisan votes. Eventually the Virginia Supreme Court had to establish the new boundaries for US House of Representatives and General Assembly districts.