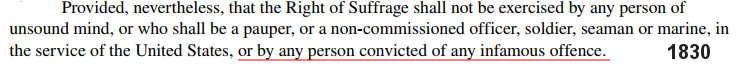

since 1830, the Constitution of Virginia has declared that people convicted of a felony lose the right to vote

Source: For Virginians: Government Matters, Virginia Constitution of 1830

Voting is a civil right. Each state must comply with Federal civil rights laws and the US Constitution, but each state has flexibility in determining if people convicted of a felony lose the right to vote in local, state, and Federal elections.

Virginia became the first state to ban felons from voting, in 1830. When Virginia adopted its second constitution that year, white males who met the minimum property requirements lost the right to vote once they were convicted of an "infamous offence." Prior to the Civil War, most other states followed the example of Virginia and banned felons from voting.1

since 1830, the Constitution of Virginia has declared that people convicted of a felony lose the right to vote

Source: For Virginians: Government Matters, Virginia Constitution of 1830

That restriction has been retained and expanded in all subsequent constitutions. In 1851, conviction for bribery was added as a disqualifying act. Specific reference to felony convictions was added starting in 1869. County officials were directed to create and maintain registers of all people convicted in local courts, which documented who had lost the right to vote.2

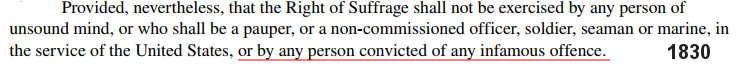

since 1830, the Constitution of Virginia has declared that people convicted of a felony lose the right to vote

Source: For Virginians: Government Matters, Virginia Constitution of 1830, 1851, 1869; 1902, Commonwealth of Virginia, Constitution of Virginia, 1971

Disfranchising felons was not a law passed by the General Assembly originally to suppress the African-American vote in 1830, since the opportunity for a free black man to vote in 1830 was tiny. However, the governor took note of how the percentage of free blacks in jail was four times greater than the percentage of whites, so the racial element was considered when the 1830 law was passed.

The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870, theoretically ensuring black men the right to vote. The Virginia legislature then took advantage of a provision in the 14th Amendment, which said:3

The key clause was "except for participation in rebellion, or other crime." In 1876, the General Assembly added petit larceny to the list of crimes which barred a person from voting. Arresting and convicting black men of petty theft was an easy process, when judges were exclusively conservative white men and juries were filled with white men who still viewed blacks through the lens of enslavement. Those convicted might serve a short sentence, but could be blocked from voting for the rest of their life.

The potential for Federal troops to ensure equal application of the law disappeared in 1877. The US Army was withdrawn from Virginia as part of the bargain to resolved the disputed 1876 presidential election and place Rutherford B. Hayes in office. Without Federal law enforcement, local officials were able to use the power of white sheriffs and white juries to selectively convict black men of crimes and disfranchise a bloc who voted consistently for Republican candidates (the "party of Lincoln"), or for the Readjuster Party until it collapsed in 1883.

Intimidation and manipulation of the voting process were used to disfranchise voters not expected to support conservative Democratic candidates, minimizing the impact of the Fifteenth Amendment. Election officials segregated voters into white and "colored" lines, then selectively sped the white voters through the process while delaying black voters.

Courts were required to send a list of those convicted to registrars. Electoral boards, registrars, and local police were almost always conservative white men. Democratic operatives, stationed at key precincts on election day, reviewed the list of those who had been convicted of petit larceny or felonies and challenged the right of black men to vote.

Disfranchising black Republicans and associating the Democratic Party with white power made Virginia one of the one-party states in the South. After the defeat of the Readjuster Party in 1883, the primary of just the Democratic Party determined who would be elected in the general election. That one-party dominance based on maintaining white supremacy lasted for nine decades.

A Republican was finally elected Governor in 1969, as a relative liberal who made promises to support racial equality. The realignment of the political parties in Virginia, in which the Republicans became the conservative option for local/state offices - as well as national offices - occurred in 1973.

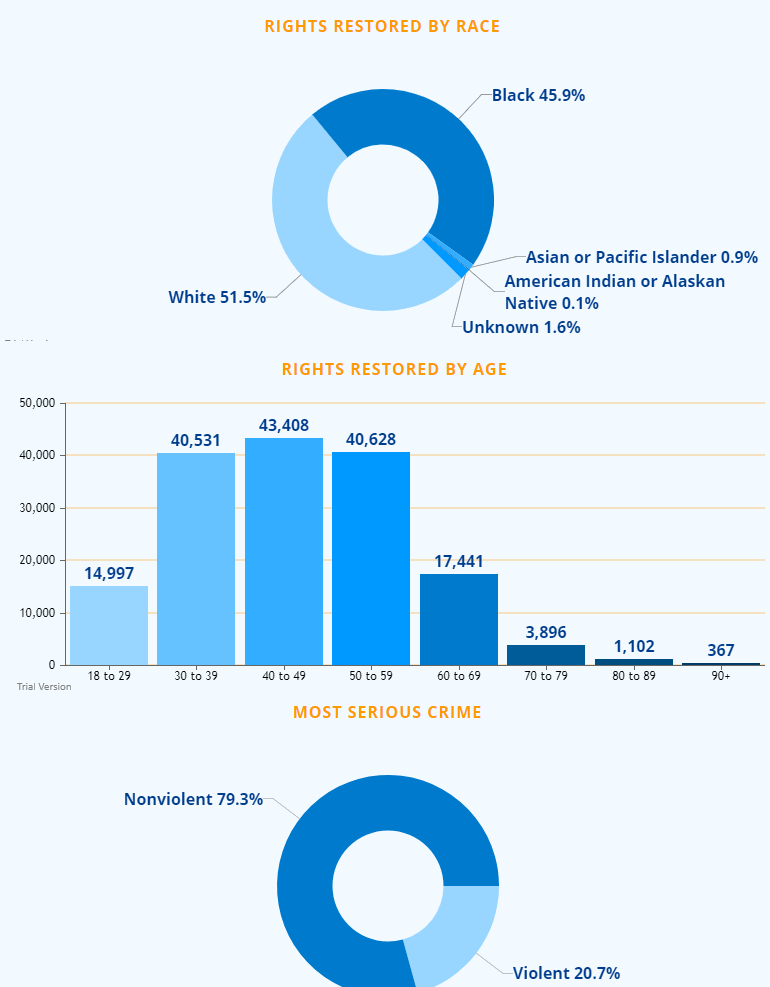

In 1982, 63% of the voters rejected a proposed constitutional amendment that would have allowed the General Assembly to modify Section 1, Article 2 of the state constitution and alter the automatic disfranchisement of felons. After the turbulent 1960's and passage of civil rights legislation at the Federal level, the automatic loss of voting rights for petit larceny was dropped from the Virginia constitution in 1971. That mitigated the impact of the disfranchisement provision, but did not eliminate racial imbalance. Felons were still automatically disfranchised after implementation of the constitutional amendments in 1971. Disfranchisement based on felony convictions still discriminated against blacks, since minorities were convicted at far higher rates than whites:4

Governors had a way to counter the racial imbalance. When a new state constitution went into effect in 1870, the governor gained the power to restore voting rights. A Virginia Supreme Court decision in 1883, Edwards v. The Commonwealth, ruled that pardons should not be used to restore citizenship rights, but governors could still take a separate action to re-enfranchise those who had been disqualified.

The provision in the state constitution that stripped away the right to vote from those convicted of petit larceny was retained in the 1902 constitution, but removed in the 1971 revision. As of 2021, the state constitution still said (emphasis added):5

Federal courts in 1996 (Perry v. Beamer and in 2000 (Howard v. Gilmore) upheld the legality of Virginia's process for disfranchising felons. Judges ruled that the state was not violating the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

In 2002, Democratic Governor Mark Warner revised the process for restoring voting rights. He reduced the traditional waiting period after sentencing for non-violent crimes from five-seven years down to three years. In 2013, Republican Governor Bob McDonnell made 350,000 felons eligible for restoration, if they had completed their sentences and paid all costs mandated by a court. Until that time, only 3% of felons had managed to complete the process to apply for restoration and get the governor to allow them to vote.

In 2016, Governor McAuliffe issued a blanket restoration of rights for all felons who had served their time and had completed any supervised release, parole or probation requirements. The governor used the powers granted to him in Article V, Section 12 of the Constitution of Virginia to restore civil rights, including the right to vote to 206,000 people in the state's database of felons eligible for restoration under McAuliffe's criteria.

The computer systems with data regarding convicted felons and voters were unable to process the large restoration smoothly. There were 132 sex offenders who had their rights restored because they had completed their criminal sentences, but were still in civil confinement in order to reduce danger to the public.

Much of the news coverage suggested focused on how the newly-enfranchised voters might support Democratic candidates in the 2016 election, and Republicans filed suit to block the blanket restoration of rights. The Virginia Supreme Court quickly ruled in a 4-3 decision that the governor's blanket restoration order was not constitutional, and he had to individually re-enfranchise the felons:6

in 2016, Governor McAuliffe issued a blanket pardon for 200,000 felons who had served their time and had completed any supervised release, parole or probation requirements

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Restoration of Rights (April 22, 2016)

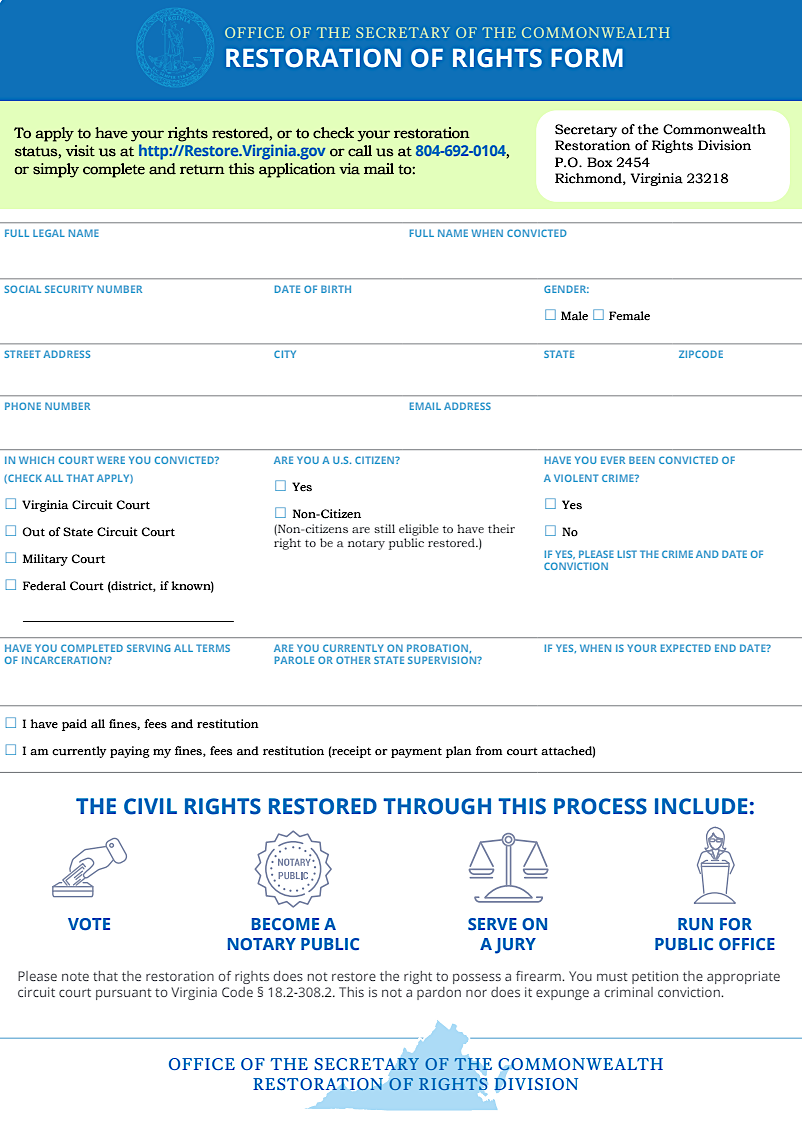

To overcome that Virginia Supreme Court ruling, the governor proceeded to process paperwork for the 206,000 individuals. He restored the right to vote, plus the right to hold public office, serve on a jury, and act as a notary public, but did not restore the right to purchase or possess a firearm. However, convicted felons who applied to a court for restoration of their gun rights could cite the restoration of voting rights in their plea.

restoration of voting rights did not automatically restore the right of a former felon to possess a firearm

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Restoration of Rights

In his final State of the Commonwealth address in 2018, Governor McAuliffe told the General Assembly and guests in the balconies:7

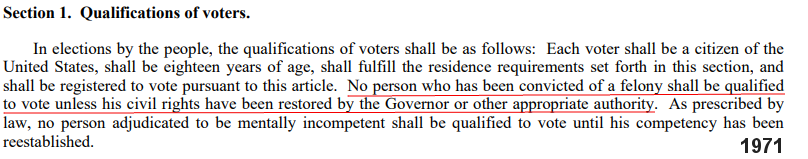

In his official portrait, Governor McAuliffe was painted in his workday office with an open notebook, working on rights restoration.8

in his official portrait, Gov. Terry McAuliffe showed himself working on his rights restoration initiative

Source: Richmond Times-Dispatch

Of the 168,000 whose rights were restored prior to the 2017 state elections, 46% were black and 42,000 people registered to vote. If they voted at the statewide average, then the governor's actions resulted in 19,000 additional votes in the 2017 elections.

That would equal an additional 1% of the total electorate. Even if all 19,000 new voters had supported the Democratic candidates for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General, the additional votes would not have affected he outcomes of those races. Republican concerns that restoration of rights might benefit Democratic candidates had more relevance in the 2017 races for some of the 100 House of Delegates seats. A few were very close, and the 94th District race ended in a tie vote.9

the demographics of the restoration of rights reflected the demographics of felony convictions in the court system

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia, Restoration of Rights Demographics

The right to vote was important enough for 42,000 felons to chose to register. As one recipient noted:10

Lifting the ban on voting by felons was presented by the McAuliffe administration as overcoming a Jim Crow-era law, designed to suppress the black vote. Some stories traced the ban back to new restrictions on voting that were included in the 1902 state constitution. That 1902 document did restrict the electorate, but the disfranchisement of felons had occurred 70 years earlier and was unrelated to later efforts to suppress the African-American vote.11

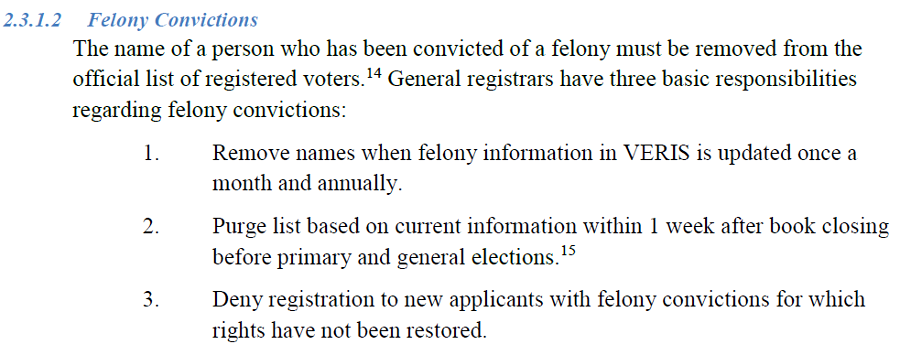

based on updates from the Virginia Election & Registration Information System (VERIS), local registrars remove newly-convicted felons from lists of registered voters

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, General Registrar and Electoral Board Handbook (p.75)

Governor McAuliffe's attempt at a mass restoration of rights in 2016, and then his individual actions for felons, did not change the laws of Virginia. Neither did the restoration of rights authorized by Governor Northam, who followed Governor McAuliffe's example and restored voting rights to 126,000 felons in his term. During Governor Northam's term, 1,000-2,000 felons were released each month.12

People convicted of a felony (but not misdemeanor) in Virginia still lose the right to vote in Virginia automatically. If those convicted of a felony had been registered, then local election officials in 133 Virginia jurisdictions remove their names from the rolls of eligible voters.

United States attorneys provide lists of people convicted of a felony in Federal District Courts to the Virginia Department of Elections, which updates the Virginia Election & Registration Information System and provides the names to local registrars. The Virginia State Police uses its Central Criminal Records Exchange to updates the Virginia Election & Registration Information System monthly, sharing details of people convicted of felonies in state courts.13

To regain the right to vote in Virginia, people convicted in state or Federal court in Virginia of a felony still needed a clemency action from the governor. The 2021 General Assembly approved a constitutional amendment to automatically authorize felons to vote, once they were released from incarceration and had completed the terms of their sentence.

Control of the House of Delegates switched to the Republican Party in the 2021 elections. The constitutional amendment was dropped after 2022 General Assembly did not pass it for a second time as required before getting on the ballot. The 2021 proposal was:14

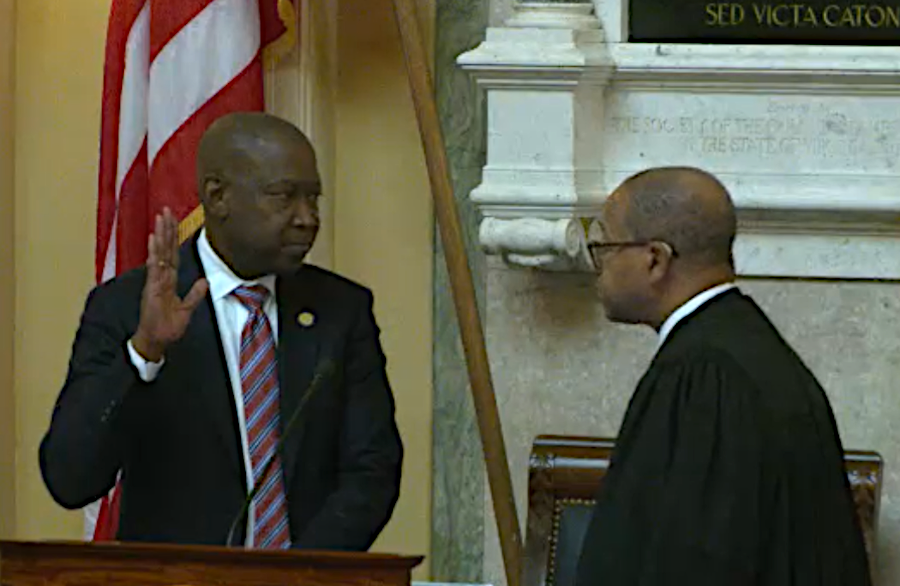

Restoration if voting rights by the governor after a felony conviction helped Don Scott become the leader of the Democratic Party in the House of Delegates in 2022. He had served previously a seven year term in Federal prison, for conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute crack cocaine. Scott pled no contest in 1994, claiming that he was guilty of transporting money but that he never sold or transported cocaine.

Republican Governor Robert McDonnell restored Scott's voting rights. In 2019, Don Scott was elected to the House of Delegates. When running for re-election two years later, he discovered that his neighbor needed a kidney transplant. He volunteered to be the donor, even though the hospital stay would limit his time to campaign. The former felon's comment later was:15

In 2022, Del. Don Scott forced a change in the party's leadership there. The Democrats voted to replace Del. Eileen Filler-Corn as the Minority Leader, and selected Del. Don Scott as the new Minority Leader. He became the first convicted felon to serve in that position, and cheerfully said:16

In 2024, Del. Scott became the Speaker of the House of Delegates after Democrats won a 51-49 majority in the 2023 elections. On the first day of the 2024 General Assembly session, Gov. Robert McDonnell made it a point to come o the Capitol and congratulate Del. Scott. Until that moment, the two had never met in person.

In a curious twist of fate, Governor McDonnell had also been convicted of a felony after he finishd his four-year term in 2015. The conviction on Federal corruption charges was overturned on appeal, so the former governor did not need to have his voting rights restored. Congratulating Majority Leader Scott in 2024 helped Gov. McDonnell raise his profile and restore his capacity to engage again in political decisionmaking.

Governor McDonnell told a reporter:17

Del. Scott (left) was sworn in as Speaker of the House of Delegates by Virginia Supreme Court Chief Justice Bernard Goodwyn

Source: Virginia House of Delegates Video Streaming, Regular Session (Janury 10, 2024)

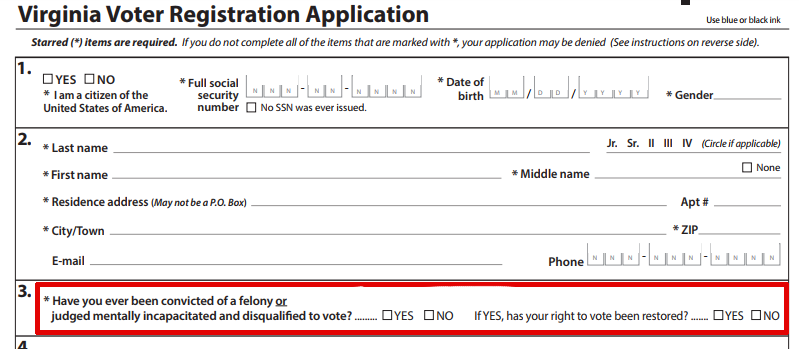

People convicted in other states, including those convicted in Federal courts there, may have their voting rights restored by whatever process is used in that state. Some never withdraw the right to vote, some automatically restore it after completion of the jail sentence, some restore the right automatically after completion of parole/probation (sometimes after an extra waiting period), and some require action such as a pardon by the governor.

If a felon's rights have been restored by the process used in another state, then Virginia will allow that person to vote.18

felons convicted in other states whose rights were previously restored by that state's process may vote in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Virginia Voter Registration Application

In 2022, the Virginia Department of Elections explained to the House and Senate Privileges and Elections Committees that the 15-year old computer system used by the Virginia Department of Elections could accommodate a restoration of rights, but did not have the capacity to revoke those rights a second time.

Since 2011, 10,558 people had their voting rights restored by a pardon from the Governor - but then committed another felony, automatically losing the right to vote a second time. Of that total, 1,248 repeat felons were still able to cast a vote because the computerized records could not include a second revocation of voting rights.

A temporary reporting system was created in 2022 to notify registrars of disqualified repeat felons. Removing them from the voting rolls would prevent future inappropriate voting until a new computer system was scheduled to go in operation in early 2025.19

Governor Glenn Youngkin changed the process after he was elected in 2021. He followed the practice of the last three governors for the first four months of his term and restored the rights of about 3,500 felons, but then he began requiring felons to apply for restoration of their voting rights after release from jail rather than automatically restore the voting rights. In the next five months, Governor Youngkin restored the voting rights of just 800 people.

The criteria by which individual applications would be approved or rejected were not made public. However, the form required identifying if the applicant had been convicted of a violent crime or still owed fines, fees or restitution, so those evidently were two factors in the decision process.

The Speaker of the House of Delegates, a fellow Republican, commented in support that he was:20

In addition to reducing the number of felons who had their voting rights restored, the Virginia Department of Elections (ELECT) was assertive in removing people from the Voter and Election Registration Information System (VERIS) after a new felony conviction. It updated the data sharing process with the Virginia State Police and announced:21

Between September 1, 2022 - August 31, 2023, the state agency cancelled the voter registrations of 17,368 people convicted of a new felony after their rights had been restored.

However, the Virginia Criminal Information Network coded probation violations as a new felony conviction. The Virginia Department of Elections process to notify local registrars did not distinguish probation violations from new felony convictions.

One person who lost his opportunity to vote in the 2023 primaries successfully sued; the Arlington County Circuit Court ordered the local registrar to add his name back into the pollbook. Later in 2023, the Virginia State Police altered the Virginia Central Criminal Records Exchange report to the Virginia Department of Elections to stop indicating that parole violations were new felonies.

Before the November 7, 2023 election, a "pilot" effort by the Virginia Department of Elections identified at least 275 people who had lost their right to vote because the computerized data exchange was flawed. In the Richmond alone, however, news media identified almost 400 affected former felons in the city plus the counties of Henrico, Hanover, and Chesterfield. Five weeks after early voting started, just two weeks before election day, the Virginia Department of Elections announced that nearly 3,400 voters had been inappropriately removed and 100 had still not been added back to the rolls.

The state agency notified local registrars so they could add those names back into the polling books. Democratic officials called for a Federal investigation into the "election integrity" initiatives of the state under Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin, suggesting that a campaign of selective voter repression was underway.

Governor Youngkin ordered an investigation by Virginia' state inspector. He included in the scope of the investigation whether people who had committed a new felony, after getting rights restored, were being removed from the voting rolls again.22

In 2023, in response to Governor Youngkin's shift to case-by-case adjudication of voting rights restoration, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and others filed a lawsuit. It claimed that the provision in the state constitution, automatically stripping a convicted felon of the right to vote, was in violation of the 1870 law that readmitted Virginia into the Union after the Civil War. According to the lawsuit, the Virginia Readmission Act allowed disfranchisement only for felonies as defined in 1870.23

Two other court cases were resolved before the American Civil Liberties Union case based on the Virginia Readmission Act.

In 2023 the Richmond Circuit Court ruled in a case brought by the NAACP that official records associated with a rights restoration case were part of a governor's "working papers." That ruling made the documentation exempt from required public disclosure under the Virginia Freedom of Information Act.

In 2024, a judge in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia ruled in a case initiated by the Fair Elections Center that a Virginia governor had wide discretion to reinstate - or not reinstate - voting rights. The First Amendment did not apply, because restoration after a criminal conviction was different from protecting an existing right. No law required the governor to be transparent or fair in the decision process.

The ruling said:24

Governor Youngkin required individuals to apply for restoration of voting rights, ending the practice of automatic restoration used by the three previous governors

Source: Virginia Department of Elections, Restoration of Rights Form