the John Andrew Twigg Bridge carries Route 3 across the Piankatank River, linking Mathews and Middlesex counties

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), John Andrew Twigg Bridge

the John Andrew Twigg Bridge carries Route 3 across the Piankatank River, linking Mathews and Middlesex counties

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), John Andrew Twigg Bridge

Native Americans presumably placed logs and aligned rocks to facilitate crossing streams without getting wet, but they constructed no bridges. Virginia's gentle topography did not require bridges, and canoes facilitated crossing rivers, lakes, and even the Chesapeake Bay. In contrast, Incas living in the Andes had to build rope bridges to cross deep and narrow canyons.

English colonists were reluctant to invest in building bridges as well. The technology was not a challenge for crossing small streams, but bridges required substantial investment of labor. In the 1600's, the trees needed for bridge-building materials were readily available but labor was scarce.

The first bridge-like structure built by the English colonists was a 200-foot wharf extending from the shoreline at Jamestown into the shipping channel of the James River. The first bridge was built in 1611. It crossed over Back River at Frigett (Frigate) Landing, permitting the colonists to get to the mainland from Jamestown Island.

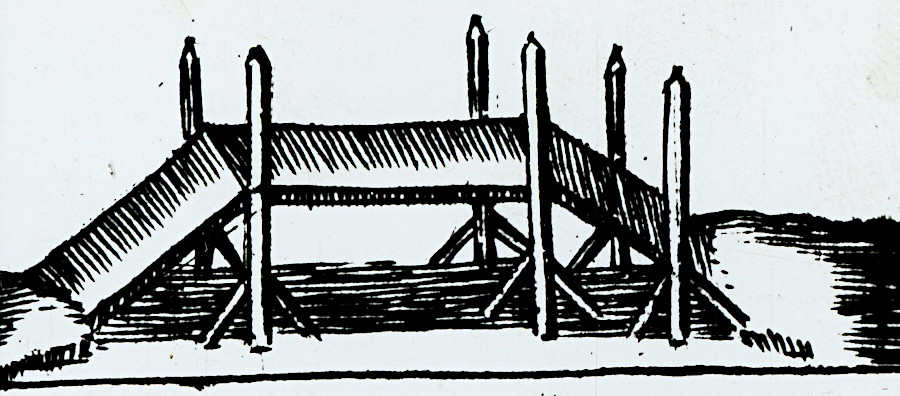

sketch of the first bridge constructed at Jamestown in 1611

Source: National Archives, The First Three Bridges Built in Virginia

It was a beam bridge comparable in design to most modern highway bridges, where the bridge's deck sits on top of heavy beams strong enough to support the weight. Starting in the 1800's, new designs would use a variety of trusses and cables to distribute compression and tension in order to support heavier, longer spans with fewer support piers between the abutments at either end of a bridge.

the first bridge was constructed at Jamestown in 1611, to get across Back River from the island to the mainland

Source: Federal Highway Administration, 1611 First Bridge (painting by Carl Rakeman)

Colonists were required to contribute their labor, unpaid, for maintaining roads and bridges. A 1705 law recognized that unskilled labor conscripted from local residents could not construct all the needed bridges. The law declared that if a bridge which required hiring skilled workers was located within two counties, then they would split the construction costs based on the percentage of residents being taxed ("tithables") in each county. The General Assembly also could authorize charging tolls on the most expensive bridges, so travelers would help fund the project.1

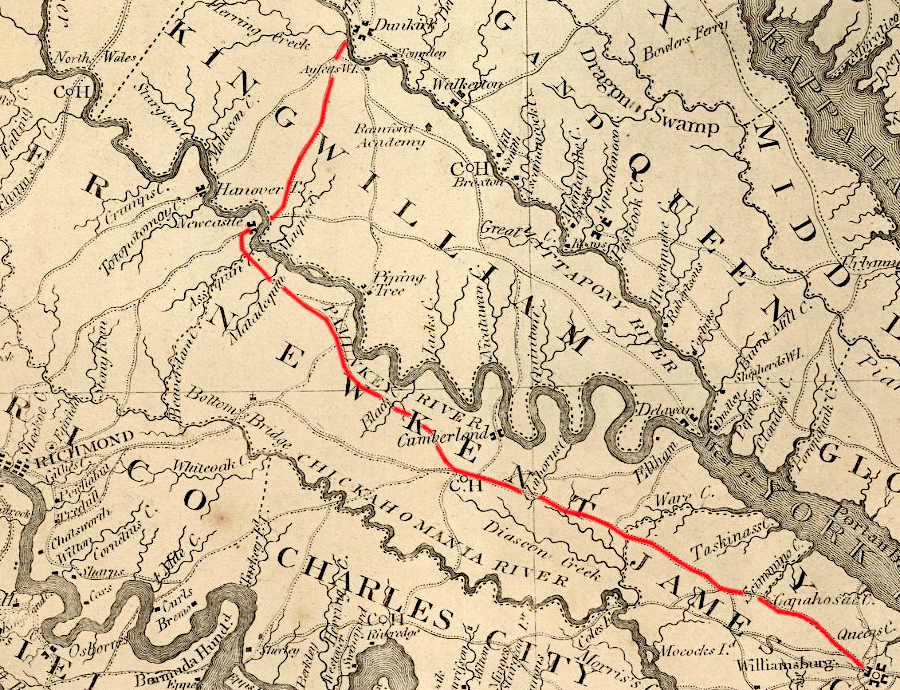

the road to the former capital of Williamsburg required crossing the Mattaponi and Pamunkey rivers by ferry

Source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Map of Virginia (by Rev. James Madison, 1807)

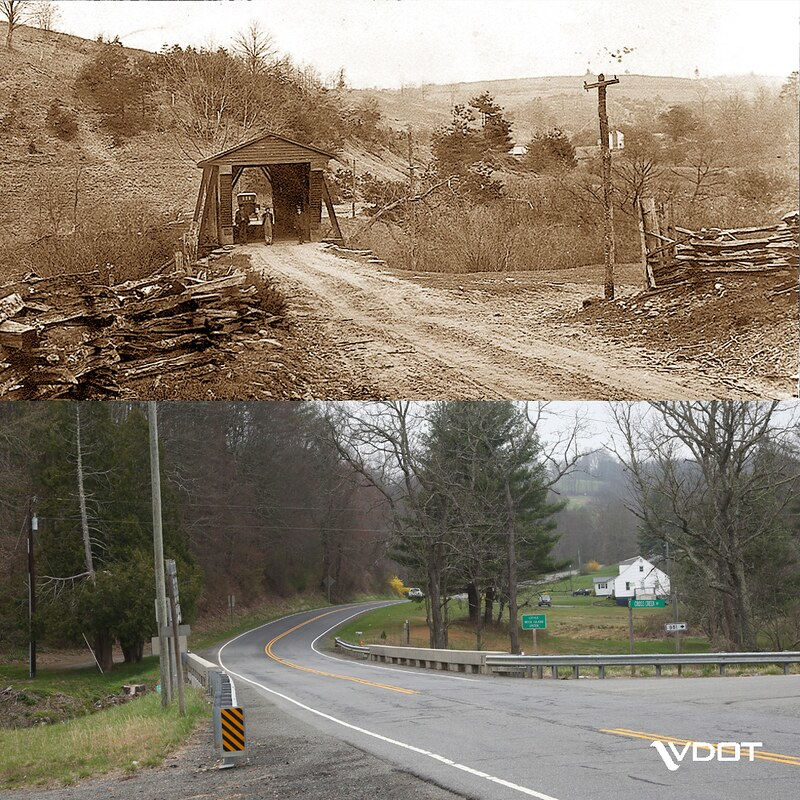

covered bridges have been replaced by structures which can handle more, and heavier, vehicles

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Little Reed Island Creek

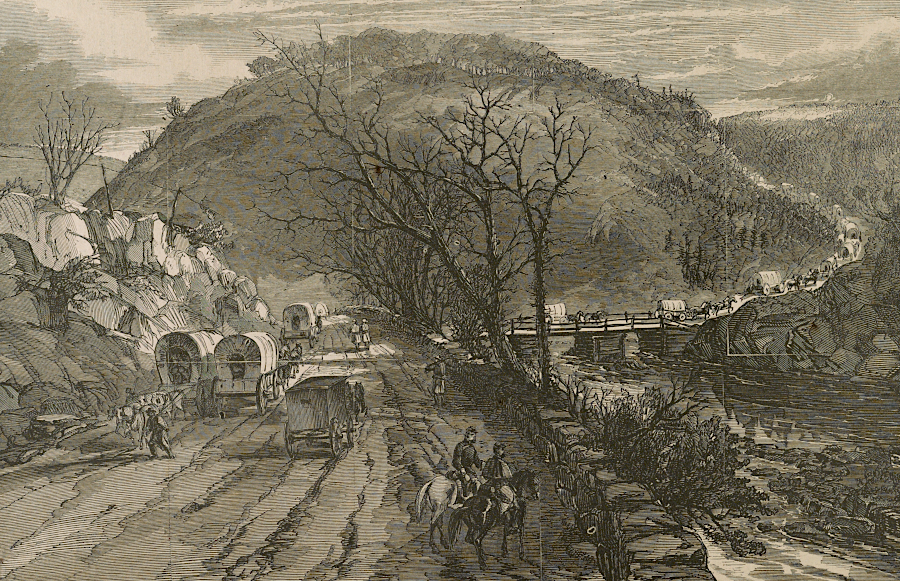

During the Civil War, bridges were key targets. Armies required wagons or train cars to carry their equipment. Destruction of a bridge could delay an enemy's march and allow an army time to fortify a defensive position.

upstream from Washington, DC, Union forces brought supplies across Chain Bridge throughout the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, New military road near the Chain Bridge, Virginia (1862)

the Orange and Alexandria Railroad bridge over Bull Run was destroyed early in the Civil War

Source: Library of Congress, View on Bull Run, crossing of Orange and Alexandria railroad

the Union side rebuilt the Orange and Alexandria Railroad bridge over Bull Run

Source: Library of Congress, Railroad bridge across Bull Run. O. & A. R.R., R. R. (i.e. Railroad) bridge across Bull Run. O. & A. R.R., and U.S. Military Railroad Bridge, Bull Run, Va. Orange and Alexandria R.R.

the original sandstone abutment on the Fairfax County side was still visible in 2025, when the Virginia Passenger Rail Authority owned the bridge over Bull Run

Similarly, construction of a bridge could allow an army to bypass fortifications and outflank the opponent, forcing them to withdraw. Rivers and streams separated components of the Union Army during the Peninsula Campaign, making them vulnerable to attack by superior numbers of Confederates. Union engineers skillfully used whatever resources were nearby to ensure the Union troops could reinforce each other.

Union soldiers quickly built temporary bridges during the Peninsula Campaign

Source: Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, Military Bridge Across the Chickahominy Virginia, June, 1862 (No.17)

Union armies were also able to build pontoon bridges to cross wide rivers. A pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock River enabled elements of the Union Army to march through Fredericksburg at the start of the Peninsula Campaign, and a year later in 1863. A similar bridge across the Potomac River facilitated the Union Army's return to Virginia after the Battle of Antietam.

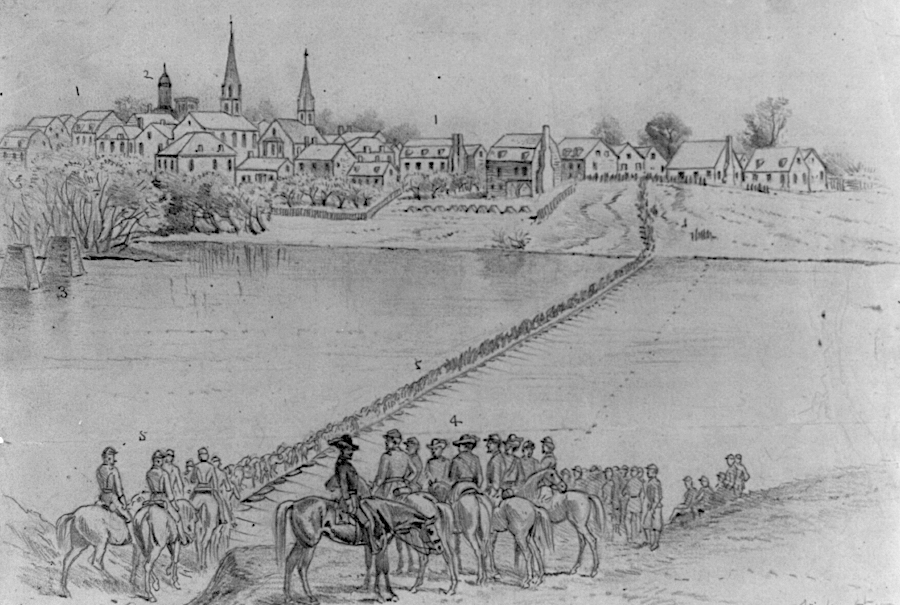

the Union Army crossed over the Rappahannock River, from Falmouth into Fredericksburg, at the start of the Peninsula Campaign

Source: Library of Congress, Occupation of Fredericksburg. General McDowell's corps crossing the Rappahannock River on pontoon bridge (May 5, 1862)

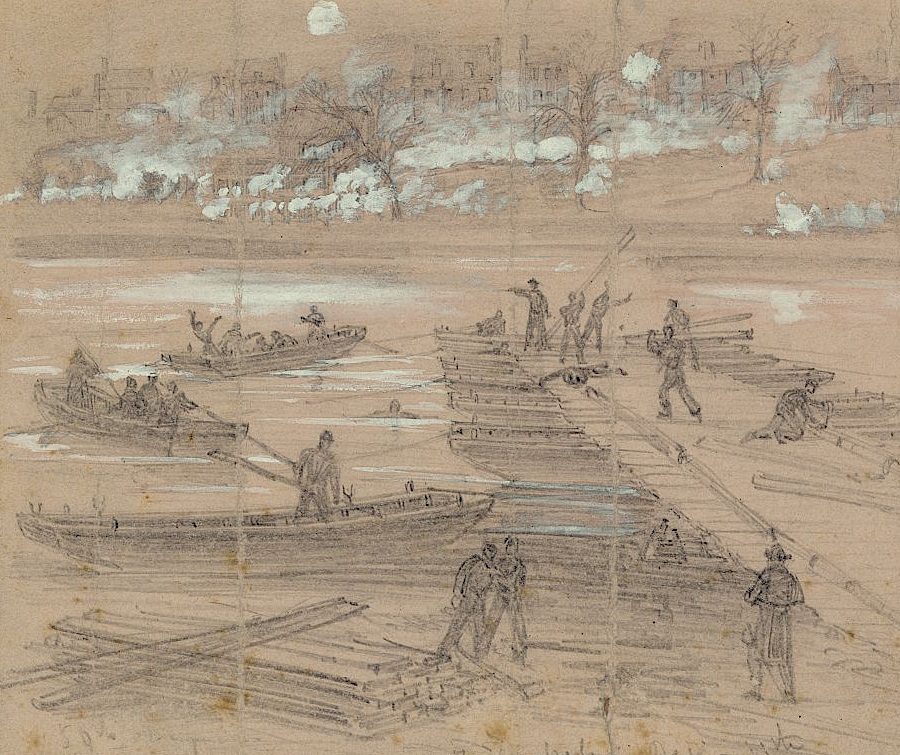

Union forces crossed the Rappahannock River again with pontoon bridges in 1863

Source: Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, Pontoon Bridge Across the Potomac at Berlin, November 1862 (No.32)

Union forces crossed the Potomac River using pontoon bridges after the Battle of Antietam

Source: Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War, Pontoon Bridge Across the Potomac at Berlin, November 1862 (No.25)

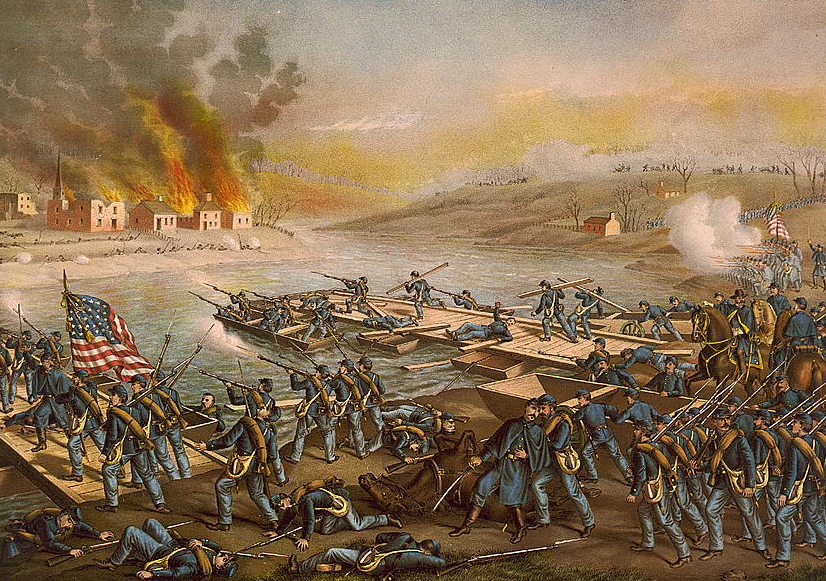

The Confederate success in the December, 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg was due in part to the delay in the arrival of pontoons to help General Hooker cross the Rappahannock River. General Lee was able to establish his Army of Northern Virginia on the southern bank of the river and prepare for the eventual crossing by the Union Army.

Confederate sharpshooters made it difficult for Union forces to build a pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock River at the Battle of Fredericksburg

Source: Library of Congress, Battle of Fredericksburg--the Army o.t. Potomac crossing the Rappahannock and Building pontoon bridges at Fredericksburg Dec. 11th.

Today, a wide range of highway, rail, and pedestrian bridges provide connections across valleys and rivers. Keeping bridges in a "state of good repair" is a major component of the operations and maintenance budget of the Virginia Department of Transportation, plus the cities and two counties (Arlington and Henrico) which retain ownership of their local roads.

Few bridges built in the 1800's have survived; most have been replaced because they became structurally unsafe or were too light/narrow to handle modern traffic. Even the "historic" covered bridges have been modified by restoration and repairs. The roof on Humpback Bridge was replaced by the Virginia Department of Transportation in 2013, but the "old" roof dated back only to the 1970's. The entire Meems Bottom Covered Bridge was rebuilt after being torched by vandals in 1976.2

the Humpback Bridge is the only Virginia bridge designated as a National Historic Landmark

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Humpback Bridge

A vast number of railroad bridges have been required because trains do not go up or down slopes easily. Tracks were laid out to minimize grades, with bridges built to cross low spots and occasionally tunnels to avoid high spots so locomotives could pull more cars with heavier loads.

Horses and wagons had the same problem until World War II, and historic roads closely followed topographic features to minimize the number of horses needed to haul a load. Ferries carried people and vehicles across rivers. Operating costs were higher, since a ferry operator needed to be paid, but ferries required far less initial investment than bridges. Since the advent of modern vehicles after 1910, nearly all ferries have been replaced with bridges to minimize delays.

The George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge connects Yorktown and Gloucester, carrying US 17 over the York River since 1952. It honors George P. Coleman, who led the Virginia Department of Highways between 1913-1922. It is the largest double-swing-span bridge in the United States, opening to provide unlimited vertical navigational clearance to US Navy and other ships. The spans are raised to different heights; otherwise, they would bump into each other when the bridge is opened for shipping traffic.

US Navy ships pass through the open spans of the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge to reach Naval Weapons Station Yorktown and Cheatham Annex

Source: Chesapeake Bay Commission, REPI Project Profile: Land Restoration, Shoreline Protection and Base Resilience at Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, Virginia

The two-lane George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge opened in 1957, carrying US17 across the York River. Construction was funded by selling 30-year bonds, and tolls were collected to pay off the bonds. Once they were repaid in 1976, tolls were removed from the bridge.

Traffic increased from 10,000 vehicles/day in 1976 to 21,000 vehicles per day in 1983, when local officials began asking the state for a new bridge of some sort.

The two-lane bridge was widened to four lanes in 1995. Six new spans were constructed in Norfolk, with the roadway already paved and guardrails/lightpoles installed. The spans were floated 40 miles to the mouth of the York River, the old two-lane spans were removed, and then the new four-lane spans were placed on the existing piers.

swing span of the 1952 two-lane bridge on the Yorktown end, after removal and on the way to Norfolk

Source: Historical Cassettes, The Coleman Bridge

the last piece of the new four-lane bridge to be installed in 1996 was the swing span on the Gloucester end

Source: Historical Cassettes, The Coleman Bridge

By using light high-strength steel, the weight of the wider 1995 bridge was limited to just 25% more than the 1952 bridge. The bridge piers in the York River were widened on the top to support four lanes, but did not need to be reinforced on the riverbed.

The contractor earned a $1.4 million bonus by completing the replacement of the six spans in just nine days, rather than using the full 24 days authorized in the contract. During the nine-day closure, vehicles were detoured to West Point to cross the Rork River.

Source: Historical Cassettes, The Coleman Bridge

Tolls were re-established in 1996. Once again, users of the Coleman Bridge funded repayment of $86 million in 30-year bonds sold to finance construction. Only northbound traffic was charged. Doubling the toll but collecting it in just one direction eliminated delays at one toll plaza while generating the same revenue, since the same amount of traffic went north and south each day.

The toll Virginia Department of Transportation continued to collect $6 million/year in tolls on Coleman Bridge even after paying off the second set of bonds, because $30 million was still owed to the state's Toll Facility Revolving Account. The standard toll fee, $2 per trip for a car, never changed in 30 years, but the E-Z Pass rate was $0.85/day in 2025.

The 2025 General Assembly approved a provision in the governor's budget to drop the fee, rather than continue collecting it until 2034 to repay all of the debt. Eliminating tolls avoided having to spend $5 million to upgrade the toll plaza, which was removed starting on August 1, 2025. Half of the $6 million/year in tolls was spent in toll collection operations.3

the only bridge to cross the York River, the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge, swings open to allow ships to pass between Yorktown and Gloucester Point

Source: Library of Congress, View to northwest from Yorktown side, showing swing spans in full open position. - George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge; Wikipedia, George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge

The Rappahannock River Bridge was built across the Rappahannock River in 1957 to carry Route 3 between Lancaster and Middlesex counties. Private ferries had connected the counties since the late 1600's, and the state assumed responsibility for that service in 1941. By the mid-1950's, state-operated ferries were carrying nearly 1,000 vehicles a day between Grey's Point and White Stone on a 25-minute trip across the Rappahannock River. The slow trip, and the lack of 24-hour service, limited economic development in the Northern Neck and frustrated residents.

Local leaders organized the Lower Rappahannock Bridge Association in 1938, the same year President Franklin D. Roosevelt presided over the groundbreaking ceremony for the Potomac River Bridge. That bridge, completed in 1940, was renamed for Maryland Governor Harry W. Nice in 1967. The Harry W. Nice Bridge was retitled again in 2018 as the Governor Harry W. Nice Memorial/Senator Thomas "Mac" Middleton Bridge, and the new replacement in 2022 still carries that title.

The State Revenue Bond Act in 1940 had authorized construction of the York River Bridge, Rappahannock River Bridge, James River Bridge at Hopewell, James River Bridge at Jamestown, Nansemond River Bridge, and state acquisition of the Claremont Ferry, Old Point Ferry, and Newport News Ferry. The York River Bridge was a higher priority than the Rappahannock River Bridge, and construction of the York River Bridge was delayed until the US Navy was satisfied its ships could reach the Naval Mine Depot upstream of Yorktown.

Virginia State Senator R. O. Norris Jr., chair of the Finance Committee in the State Senate, ensured the bond package to fund the Coleman Bridge and the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel also included the 10,000' long bridge across the Rappahannock River. Without his efforts, the slow trip by ferry across the Rappahannock River would have continued into the 1960's.

At the dedication ceremony of the Rappahannock River Bridge, a military aircraft flew over the bridge. Later that year a Navy pilot from Kilmarnock flew an F-9 Grumman Cougar jet beneath it, staying just 50' above the Rappahannock River. The US Navy was not aware of his daredevil maneuver, so there was no retribution. To date, no one has repeated a similar fly-under.

The General Assembly named Virginia's first and only bridge to cross over the mouth of the Rappahannock River as the Robert O. Norris, Jr. Bridge in 1958. In the area, only Middlesex County officials desired to retain the Rappahannock River Bridge name; State Senator Norris' district had never included Middlesex County.

the Robert O. Norris Bridge, carrying Route 3 across the Rappahannock River, opened in 1957

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Robert O. Norris Bridge Replacement Project - Environmental Study Public Hearing Display Boards

The Norris Bridge was repaved in 1994-95. Dominion Energy removed the 115kV electricity transmission lines attached to the Norris Bridge in 2021, replacing them with buried cables downstream.

Before its 50th anniversary celebration in 2008, a campaign had already started to replace the Norris Bridge. In 2021 the Commonwealth Transportation Board approved funding for the Special Structures 50-Year Long-Term Plan. It authorized nearly $400 million to build a two-lane replacement bridge, with shoulders and a higher guardrail to reduce the potential for vehicles to crash through and fall into the Rappahannock River.

Construction was anticipated to start in 2036. However, in 2025 the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) proposed the General Assembly authorize issuing $1 billion in revenue bonds in order to accelerate work on 18 "mega-structures," bridges and tunnels that required special consideration due to size or complexity. Construction costs had risen nearly 25% over the previous three years, so the legislature approved the bonds to minimize the impact of future inflation.

The first $200 million of bonds was scheduled for 2028. With that funding, the Commonwealth Transportation Board advanced the start date of the Norris bridge replacement by eight years. As noted in Governor Youngkin's news release announcing the speeded-up schedule:4

construction to replace the Robert O. Norris Bridge was accelerated to start in 2028 instead of 2036

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Robert O. Norris Bridge and Robert O. Norris Bridge

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel was not included in the list of mega-structures, since it was not maintained by the Virginia Department of Transportation. Other mega-structures were:5

Big Walker Mountain Tunnel

East River Mountain Tunnel

Route 460 Connector

SMART Road

Benjamin Harrison Bridge

Varina Enon Bridge

Berkley Bridge

Chincoteague Bridge

Coleman Bridge

Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel

High Rise Bridge

I-564 Tunnel

James River Bridge

Monitor Merrimac Memorial Bridge Tunnel

Eltham Bridge

Gwynn's Island Bridge

Rosslyn Tunnel

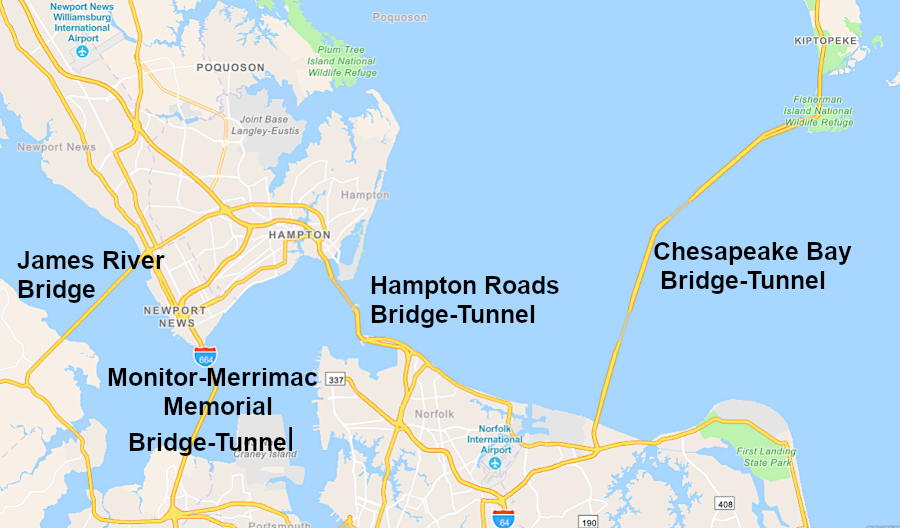

In Hampton Roads, tunnels have been constructed as a part of the major crossings rather than bridges, to minimize the risk of an enemy destroying a structure and creating a dam of debris that blocked US Navy ships from reaching key facilities.

a tanker hit the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge in 1977, demonstrating the risk of a damaged bridge blocking the shipping channel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge

Bridge components were built near each shoreline, since those structures are far less expensive, but tunnels go underneath the major shipping channels.

High Rise Bridge over the Elizabeth River (May 11, 2018)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, High Rise Bridge

construction of the new High Rise Bridge over the Elizabeth River (January 31, 2019)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, High Rise Bridge

Modern engineers consider environmental as well as construction costs before decisionmakers choose between constructing an embankment/causeway, tunnel, or bridge. However, politics remains a key a factor in allocating funding and prioritizing construction or replacement of bridges.

The tallest highway bridge in Virginia, 250 feet above Grassy Creek in Buchanan County, was constructed near Breaks Interstate Park on the Virginia-Kentucky border. Prior to completion of the US460/Coalfields Expressway bridge, the "Smart Road" bridge built in 2001 over Wilson Creek near at Blacksburg was the highest highway bridge in Virginia.

That was far less than the height of the tallest building within the state, the 508' high Westin Virginia Beach Town Center. In 2020, Dominion Energy completed the tallest structures in Virginia, two offshore wind towers. Each blade of the 6MW turbines was 253 feet long, on towers that rose 620 feet from sea level. In 2024, however, the City of Chesapeake approved construction of LS GreenLink USA's facility to manufacture submarine cables to transmit electricity from offshore wind farms. The factory design included a 660' high tower.5

the Smart Road bridge over Wilson Creek in Montgomery County is now the second-highest highway bridge in Virginia

Source: Ben Townsend, Ellett Valley Smart Road bridge

The two 1,700-feet long spans of the US 460 bridge are part of the Corridor Q 460 Connector in the Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS). The $100 million bridge was built in 2011-2015, but no funding was committed for the connecting roads. Kentucky built its portion of the connector road by 2020, but Virginia had only carved out the roadbed for its future connecting highway. After the state obtained $300 million in Federal funds, a downsized road was planned for completion in 2021. The planned four-lane connector was reduced to just two lanes, with climbing lanes on hills.

The two spans finally opened to traffic on November 16, 2020. That was five years after they were completed. Drivers coming into Virginia had to make a hard right turn to get to Route 80, since the rest of Corridor Q to Grundy had not been built. Drivers headed west into Kentucky could use the upgraded Route 460 from the state line to near Elkhorn City.

the tallest highway bridge in Virginia was completed between 2011-2015, using Federal funds for the Appalachian Development Highway System

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Route 460 Connector, Buchanan County, Virginia

The tallest bridge in Virginia was a visual monument of the political desire to improve transportation in the Appalachian region, and also to Virginia's over-optimistic approach to starting highway projects. The SmartScale prioritization process mandated by the General Assembly in 2014 eliminated the potential of another "bridge to nowhere," by requiring a commitment of full funding before construction began for all projects that were approved by the Commonwealth Transportation Board. Fewer projects could be started under the SmartScale approach, but no longer would one be left incomplete and unusable.

the highest bridge in Virginia was completed before the state built its part of the Corridor Q 460 Connector

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

the bridge over Grassy Creek sat unused (except by local trespassers) for over five years

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Route 460 over Grassy Creek (#13)

The Virginia Department of Transportation chose to schedule rehabilitation of the deck of the bridge over Grassy Creek 28 years after completion, reflecting a more-comprehensive planning approach for the life cycle of the state's bridges. The Virginia Secretary of Transportation who inherited the Grassy Creek debacle in 2013 was responsible for implementing the SmartScale approach, and made the planning/budgeting process more integrated and logical. He was puzzled by his predecessor's decision to build the bridge before getting funding for the connecting roads, asking at one point "why would they start there?"

The cantilevered bridge was logistically challenging to construct, in an isolated area with few local workers. It was unrealistic to haul prefabricated segments over the Appalachian roads, so a concrete plant was built at the site to supply the material needed for 84 cast-in-place segments on each bridge. When Roads & Bridges chose it as the #1 bridge project in 2013, the magazine noted:6

between 2015-2021, the connecting road to the bridge over Grassy Creek remained unfinished

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

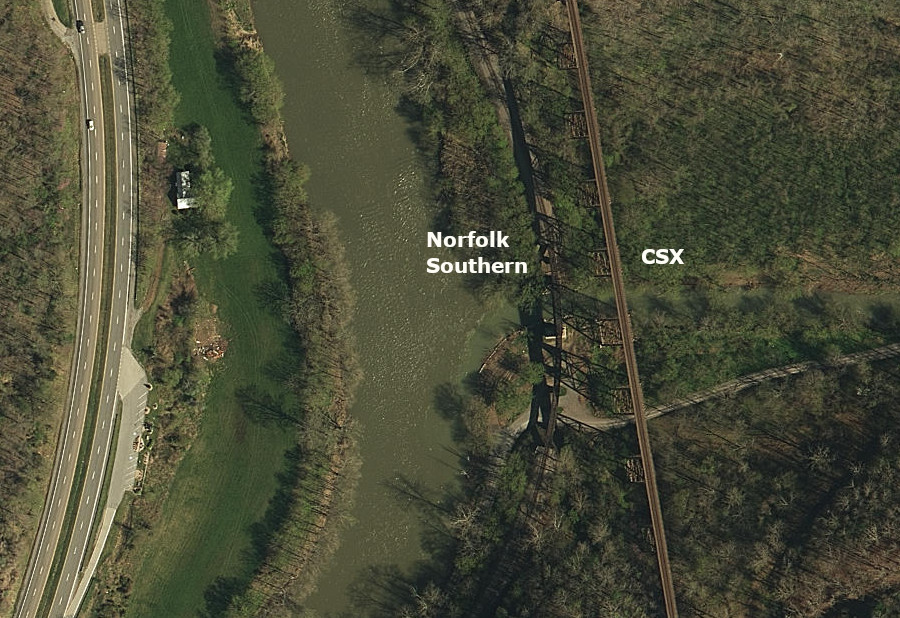

The tallest railroad bridge in Virginia crosses Copper Creek in Scott County. The Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) Railway built a structure 167 feet high, parallel to a much-lower bridge constructed by the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway in 1891. The height of the Clinchfield bridge reflected the priority of that railroad to build a high-quality line that minimized grade, including 55 tunnels in order for heavy trains to carry Kentucky/Virginia coal to Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Both bridges are still in use. CSX owns the former Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) Railway bridge and Norfolk Southern owns the lower structure built by the South Atlantic and Ohio (SA&O) Railway.7

the tallest railroad bridge in Virginia, 167 feet high, was built by the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio (CC&O) Railway in 1908 and is now part of the CSX railroad

Source: cmh2315fl, Copper Creek Viaduct (Scott County, Virginia)

the tallest railroad bridge in Virginia crosses Copper Creek in Scott County (note lower bridge in foreground)

Source: cmh2315fl, Copper Creek Viaduct (Scott County, Virginia)

the low bridge built in 1891 and the 167-feet high bridge built in 1908 are still in use

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Virginia has roughly 70 swinging bridges, with over 20 in Lee County. Of the 14 in Scott County, 11 are still accessible for public use. The swinging bridge over the Clinch River at Clinchport is 282 feet long.

Most swinging bridges are maintained by the Virginia Department of Transportation. Many were built to provide access across streams at low-water fords, allowing pedestrians to stay dry and allowing some connectivity during times of high water.

Only one swinging bridge crosses the James River. That structure at Buchanan uses some piers constructed in 1851 for the Buchanan Turnpike Company's Toll Bridge, which was built the same year that the James River & Kanawha Canal reached Buchanan. That covered bridge was burned during the Civil War. The replacement washed away in 1877, after which the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad rebuilt it as a toll-free structure. After a new highway bridge was built downstream in 1938, the 366-foot long swinging bridge was constructed.In 2020, the Virginia Department of Transportation proposed to eliminate the two state-maintained swinging bridges over the Robinson River at Criglersville in Madison County. Neither bridge connected to a public paths or hiking trail, so the opportunity for grant funding was limited and the priority for using maintenance funds for the swinging bridges was low. Complete restoration was required, and the state estimated each bridge would require $1.5-$2.5 million. Dismantlement and demolition would cost $100,000 for each bridge.

The bridge over the Robinson River, built in 1948 parallel to the Lindsay Lane low-water bridge, was closed in October, 2020. Local support for the "Pottery" bridge, built in 1987, helped keep that one open after deck boards were replaced. The Virginia Department of Transportation estimated the repairs would enable keeping the bridge open for another 1-2 years. The citizen-led initiative to save the swinging bridges assumed VDOT would donate the bridges, and the landowners who controlled the right-of-way to them would allow public access.

By 2024, the Lindsay Lane swinging bridge was still closed and the Madison County Board of Supervisors was still debating what actions to take. If a grant was obtained to provide funding, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) was willing to repair the structure but required some other organization then take ownership. The Robinson-Rose Community Alliance was willing to own and manage the bridge as a community asset, but wanted Madison County to enter a public-private partnership and assume liability.

The chair of the Madison County Board of Supervisors said at its February 13, 2024 meeting:8

Source: Virginia's Swinging Bridges

the Virginia Department of Transportation closed the swinging bridge over the Robinson River at Lindsay Lane in 2020

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Criglersville Swinging Pedestrian Bridges (October 27, 2020)

The longest pedestrian swinging bridge in North America, stretching 725 feet across the Russell Fork gorge, will be constructed over the Virginia-Kentucky border at Breaks Interstate Park. The bridge will link the park to the Pine Mountain Trail, which extends 120 miles south to Cumberland Gap. The Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority funded over half of the costs of the swinging bridge in order to enhance business activity stimulated by tourism.9

Efforts to preserve old bridges extend beyond just the covered bridges in Virginia. The Clarkton Bridge over the Staunton River, built in 1902, was documented by the Historic American Engineering Record as a representative example of a pin-connected steel Camelback truss. The bridge was closed to traffic in 1998, rather than upgraded to support modern vehicles.

the Clarkton bridge, a pin-connected steel Camelback truss, connected Halifax and Charlotte counties starting in 1902

Source: Library of Congress, Clarkton Bridge, Spanning Staunton River at State Route 620, Clarkton, Halifax County, VA

It was scheduled for demolition, but local advocates convinced the state to preserve it as a pedestrian-only bridge. Incorporating it into the Tobacco Heritage Trail was considered.

the 1902 Clarkton Bridge was converted for pedestrian use in 2005, and finally demolished in 2018

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Clarkton Bridge and Clarkton Bridge

In 2015, after a decade of recreational use, bridge inspectors declared the Clarkton Bridge was no longer safe for even pedestrians. Cost of repair was estimated at over $7 million, while demolition was estimated to cost only $1 million. The Clarkton Bridge was demolished in 2018.10

Clarkton Bridge was in rural Southside, crossing the Staunton (Roanoke) River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The Virginia Department of Transportation closed the Waterloo Bridge over the Rappahannock River in January, 2014 because of safety concerns. The wrought iron bridge, with wooden deck, was first erected in 1878 to connect Culpeper and Fauquier counties. The 680 vehicles/day could no longer use the bridge on Route 613.

The Piedmont Environmental Council led the charge to get the Virginia Department of Transportation to repair, rather than replace, the oldest remaining Pratt through truss bridge in the state. A local resident agreed to donate $1 million, but Fauquier and Culpeper counties declined to match it.

Local, persistent efforts to preserve the 366-foot long, single-lane bridge finally paid off. In 2020 the state awarded a $3.7 million contract using state funds to remove, repair, and reinstall the components of the Waterloo Bridge, so it could once again carry cars and light trucks across the river. Traffic had averaged 630 vehicles per day before the bridge was closed.

In an eight-minute lift in April, 2020, a 550-ton crane hoisted the 30-ton bridge to a staging area on the shoreline. In November, after restoration, the Virginia Department of Transportation reinstalled it. However, the $1 million donor had died in September, so he never saw the project get completed.

The first cars crossed the bridge again in February, 2021. New six-inch-thick timbers for the bridge deck altered the experience of crossing the bridge, as noted by one driver in his pickup:11

Waterloo Bridge, crossing the Rappahannock River, dates back to 1878

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Waterloo Bridge

Waterloo Bridge has a wooden deck

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Waterloo Bridge

Various designs for bridges were used after the Civil War. Superstructure shapes align tension and compression with different techniques, and reflect the different strengths/weaknesses of woods, metals, and concretes. Trusses transfer stress from the superstructure to the abutments and piers which support the structure:12

the last remaining rainbow arch highway bridge in Virginia carries US 1 across Stoney Creek in Dinwiddie County

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.106)

Albert Fink patented a distinctive W-shaped truss design in 1854. One of only two Fink truss bridges still remaining was built by the Norfolk & Western Railroad west of Lynchburg. It was moved in 1985 to Riverside Park in Lynchburg, to serve as an overlook as well as an historic exhibit. That structure is recorded as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, though it has been moved from its original location.

Most truss bridges built with an iron or steel framework have been replaced by concrete structures. The US 301 bridge across the Rappahannock River, connecting Port Royal in Caroline County with Port Conway in King George County with a metal truss over the main navigation channel, was replaced in 1980.13

the truss on the US 301 bridge over the Rappahannock River was eliminated in the 1980 replacement

Source: Bridge over the Rappahannock River at Port Royal, Virginia

the last remaining Fink truss bridge in Virginia is now in Riverside Park in Lynchburg

Source: Kipp Teague, Fink Truss Bridge in Riverside Park, Lynchburg, Virginia

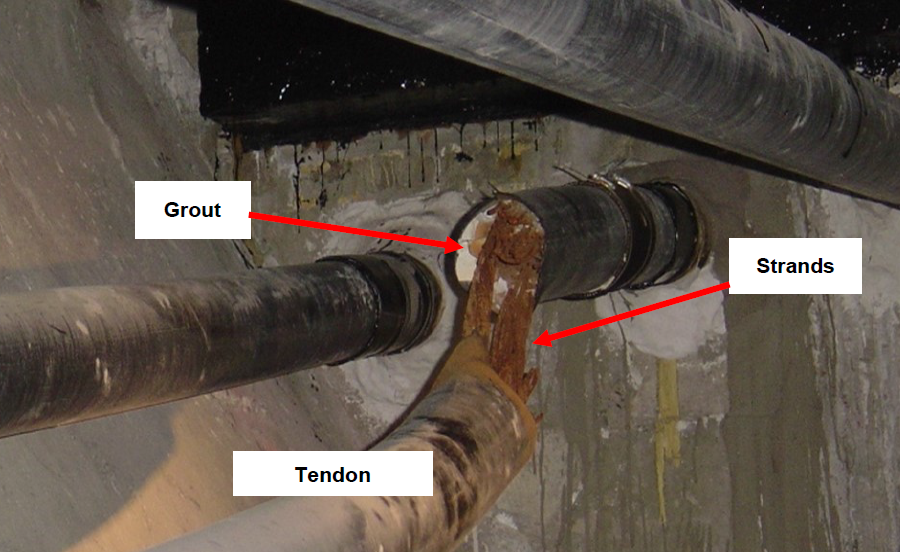

The Varina-Enon bridge over the James River uses cables stretching diagonally from the main towers to the bridge superstructure to hold up the bridge deck for I-295. The deck was constructed from prefabricated concrete panels with a post-tensioning system. Each panel had a "tendon" of high-strength steel strands inside a duct, and the strands were pulled tight before the duct was filled with grout. The "post-tensioning" makes the concrete stronger by putting it under compression.

high-strength steel strands are pulled tight, then grouted in place to create "tendons" that put tension on concrete panels

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Route 460 over Grassy Creek (#13)

The Varina-Enon bridge was only the second major highway bridge (after the replacement bridge for the Sunshine Skyway in Florida) to use a concrete cable-stayed bridge design.

the Varina-Enon Bridge, completed in 1990, was the second major concrete cable-stayed highway bridge built in the United States

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Varina Enon Bridge over the James River. 89-5312-5 (1989)

the cables on the Varina-Enon Bridge make it a distinctive, easy-to-remember structure

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, DSC00934

The innovative design of the high bridge eliminated any need for a drawbridge to allow ships to go back and forth to the Richmond Marine Terminal, upstream of the structure. The bridge was solid enough to withstand a tornado in 1993 that overturned trucks on the roadway. However, inspectors discovered in 2007 that a tendon had corroded and broken; multiple ducts with incomplete and/or low-quality grout had to be repaired. A 30-year maintenance plan developed in 2018 had an estimated cost of $150 million for the bridge, demonstrating that costs for maintenance over the life cycle of a bridge can exceed initial construction costs.14

tendons on the Varina-Enon Bridge required repair in 2007, 17 years after construction

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Varina Enon Bridge over the James River. 89-5312-5 (1989)

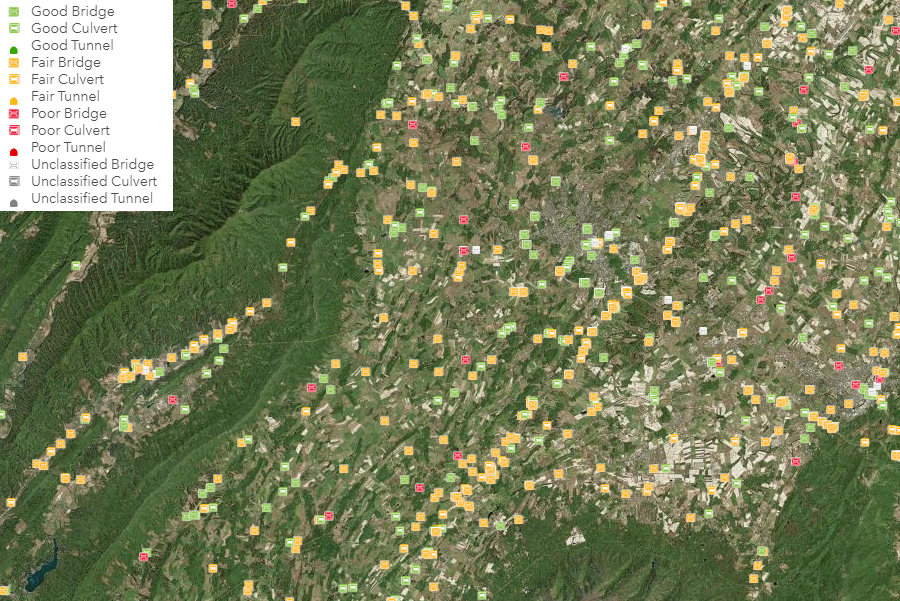

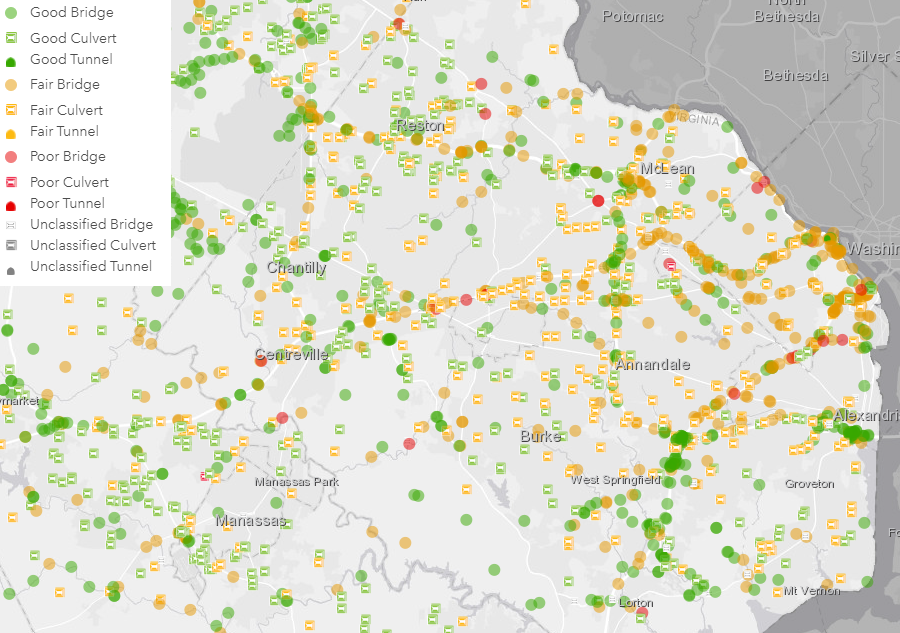

the Virginia Department of Transportation monitors the condition of bridges and culverts, to plan maintenance/replacement

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Bridges and Culverts

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) plans to replace rather than continue to repair the Benjamin Harrison Bridge before 2040. The state may get two additional decades of use beyond the anticipated 50-year service life span of the 1966 bridge by spending $78 million between 2018-2039. It will cost another $182 million (in 2018 dollars) to build a replacement structure. Funding might be obtained in a public-private partnership.

The Benjamin Harrison Bridge was repaired after a collision with the SS Marine Floridian tanker in 1977, but the trusses are still connected with rivets. The design provides almost no redundancy in case of a fracture of a critical structural component; the bridge could collapse without warning. The Virginia Department of Transportation publicized in 2018 that the replacement will not include a tower-driven vertical lift, or any drawbridge. A much-taller structure will be required to eliminate the maintenance and operational costs of bridge openings:15

the tanker ship Marine Floridian struck the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge on February 24, 1977

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge

the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge required 20 months of repairs

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge

The oldest Bowstring Truss Bridge in Virginia, and perhaps the oldest metal bridge in the state, is currently at the Ironto Rest Stop on I-81 between Roanoke and Blacksburg.

Bedford County ordered six bridges using the tubular arch truss design after a flood in 1877. The 55' long bridge was made from wrought iron, with rivets used to connect the tubular and trussed suspenders rather than the bolts and nuts/treaded connections for the rest of the structure. The Bowstring Truss Bridge was moved from Stony Creek to Roaring Fork, also in Bedford County, in the 1930's. It was disassembled again and reinstalled at the Ironto Rest Stop in 1977.

The bridge was added to the Virginia Landmarks Register in 2008, and to the National Register of Historic Places five years later. Moving the bridge did not disqualify it from listing on the historical registers:16

the Bowstring Truss Bridge retains its historical significance, even though it has been moved from Bedford County to the Ironto Rest Area in Montgomery County

Source: cmh2315fl on Flickr, Bowstring Truss Bridge

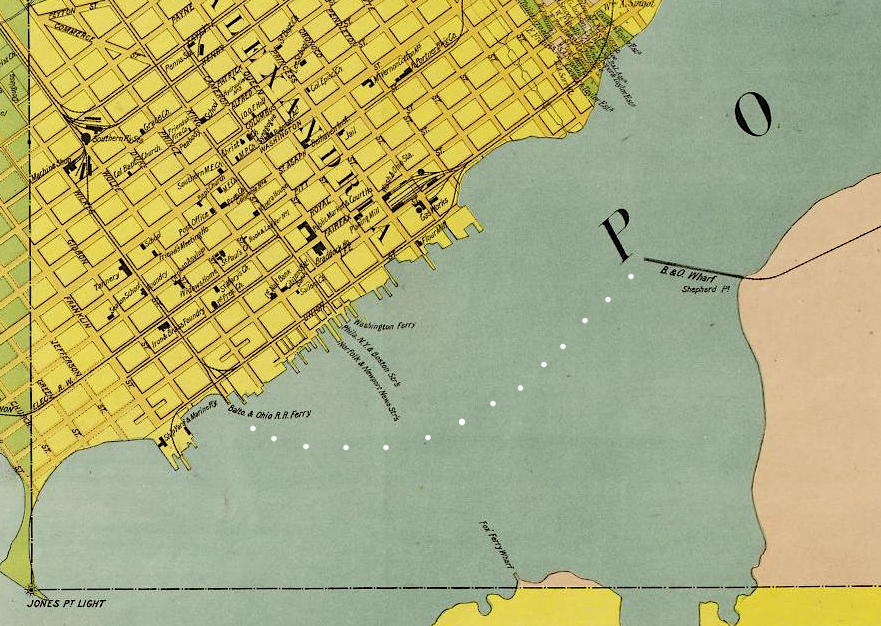

One of the most unusual bridges in Virginia was the Aqueduct Bridge constructed for the Alexandria Canal. Alexandria was a port city, and a rival of Georgetown. Both were located within the District of Columbia when the US Congress chartered the Alexandra Canal Company on May 26, 1830. Eight stone piers supported a wooden trough filled with water. That bridge, plus a seven-mile canal dug parallel to the Potomac River to Alexandria, allowed boats on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal to float to Alexandria with coal, grain, timber, and other freight.

the Aqueduct Bridge allowed boats to float, over the Potomac River, from the C&O Canal in Georgetown to Alexandria

Source: Architect of the Capitol, This Georgetown Bridge Was For Boats

The far western edge of the Aqueduct Bridge became part of Virginia in 1847, when the Federal government returned ("retroceded") Virginia's portion of the District of Columbia. During the Civil War the trough was covered with wooden planks so troops and wagons could use the bridge to cross the Potomac River. The trough was re-filled with water in 1866, but a second level was added in 1868 to provide a toll highway and footpath.

The Federal government purchased the structure in 1886. It replaced the original wooden "boat bridge" with an iron truss bridge for traditional pedestrian and wheeled vehicle traffic. In 1904, the Great Falls and Old Dominion Railroad widened the superstructure to support a trolley line across the bridge. After construction of the Key Bridge in 1923, the Aqueduct Bridge was closed.

The iron superstructure was removed in 1933. Seven of the eight stone piers were blasted away in 1962 so boaters would have fewer obstructions. The end of the bridge in Georgetown and the base of one pier near the Virginia shoreline have been left standing as historic remnants.17

the Aqueduct Bridge was completely within the District of Columbia until retrocession in 1847

Source: Library of Congress, Chart of the head of navigation of the Potomac River shewing the route of the Alexandria Canal (1841)

The constraints of railroads limited where bridges could be constructed. Train wheels do not grip rails the way car tires grip asphalt, so railroad engineers alter topography to minimize any grade. No railroad bridge was ever constructed across the James River downstream of Richmond. Such a bridge could have been constructed with a drawbridge rather than a high center so ships could always navigate past the structure, but Norfolk and then Newport News developed as independent shipping terminals at the end of competing railroad lines. There was no business incentive to build a railroad bridge across the river.

In contrast, cars and trucks can cross the James River downstream from Richmond at multiple locations. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (US 13), the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (I-64), the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel (I-664), and the James River Bridge (US 17) provide highway links between southern Hampton Roads with the Eastern Shore and the Peninsula. On occasion, vehicles crash through or over guardrails and end up in the water. Only rarely do occupants survive the experience.

there are multiple road crossings at Hampton Roads, but no railroad bridges

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The construction of the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad from Delaware to the southern tip of the Eastern Shore in 1884 left a 26-mile gap between the new town of Cape Charles and the railroads that terminated in Norfolk. There was never enough traffic to justify even planning a railroad bridge across the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Instead, the railroad created a "car float," and used barges to transport freight between wharves at Cape Charles and Little Creek.

The car float ended permanently in 2018 when the Bay Coast Railroad ceased operating and the 49 miles of track between Cape Charles and Hallwood were abandoned. The barge that transported freight cars across the Chesapeake Bay was sold, but a remnant of an earlier barge was retained. The Captain Edward Richardson/Nandua had carried the rail cars from 1949-1981, when it sank in the Cape Charles harbor. The pilot house was retrieved and repurposed as the railroad office at the yard in Cape Charles.18

Getting a railroad bridge over the Potomac River at Washington, DC was more of a political than a technical challenge. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad negotiated a special arrangement with the Federal government at the start of the Civil War, and gained exclusive rights to haul rail cars across the Long Bridge. However, the Pennsylvania Railroad obtained the monopoly in 1870.

Rather than lose access to the traffic between Virginia and the northern states, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad started a car ferry across the Potomac River. It barged railroad cars from Shepherd's Landing at Marbury Point in the District of Columbia to Alexandria from 1874-1906,. When the various railroads serving Alexandria reached an agreement for sharing use of the new Long Bridge and interchanging cars at Potomac Yard, the inefficient car float ended.

However, during World War II an "Emergency Bridge" was constructed between Shepherd's Landing at Marbury Point and Montgomery Street in Alexandria. The bridge allowed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad trains to use a second crossing over the Potomac River, in addition to Long Bridge. The Emergency Bridge was removed in 1945, as the war in Europe ended and traffic declined.19

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had to operate a "car float" to barge freight cars across the Potomac River between 1874-1906

Source: Library of Congress, Map of Alexandria County, Virginia for the Virginia Title Cos

railroad drawbridges stay in the "up" position except when trains cross, in contrast to highway bridges

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Gilmerton Bridge

According to the 2019 statistics in the National Bridge Inventory, there were 13,933 highway bridges in Virginia in 2019. The bridges carrying the most traffic in Virginia each day were at the end of on I-64 near Bowers Hill in the City of Chesapeake. The braided ramp carrying two lanes of I-64 westbound towards I-464 carries 300,000 vehicles/day, on average.

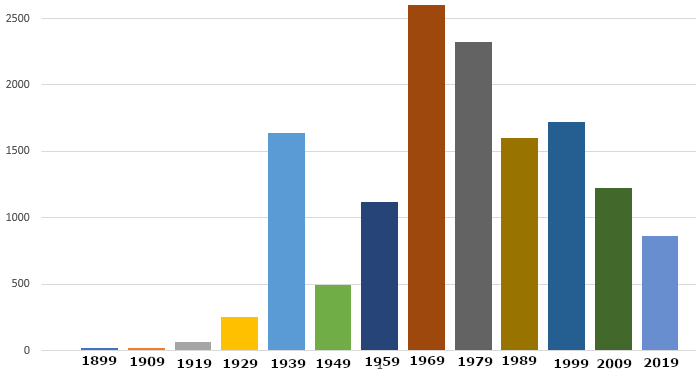

The National Bridge Inventory also documents the number of highway bridges still in use, based on the time period of construction:20

built between 1800-1899: 17

built between 1900-1909: 21

built between 1910-1919: 61

built between 1920-1929: 253

built between 1930-1939: 1,639

built between 1940-1949: 495

built between 1950-1959: 1,118

built between 1960-1969: 2,604

built between 1970-1979: 2,320

built between 1980-1989: 1,600

built between 1990-1999: 1,721

built between 2000-2009: 1,224

built between 2010-2019: 860

number of still-remaining bridges that were built in a particular decade, after 1800's

Source: Federal Highway Administration, National Bridge Inventory

By 2020, so many metal truss bridges had been removed/replaced that Preservation Virginia included then in its list of "2020 Virginia's Most Endangered Historic Places." There were approximately 620 metal truss bridges in 1975, but by 2020 only 5% of them remained. The historic preservation organization stated that metal truss bridges were:21

the 1882 Aden Road bridge was rehabilitated and reinstalled in Prince William County

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, One-lane bridge on Aden Road in Nokesville and second image (by Trevor Wrayton)

By 2021, the state had 14,042 bridges. Just 3.6% (501 bridges) were "structurally deficient;" nationwide, nearly 7% were rated that way. Most of Virginia's highway bridges were constructed using standards that anticipated repairs would be required after 30 years. Bridges were designed with joints to allow expansion/contraction as the temperature changed, and corrosion from water and road salts was concentrated in those gaps.

New design standards eliminated the joints. New bridges are expected to last 75 years. However, well-constructed bridges in good condition can still be damaged and destroyed. In March 2024, a ship leaving Baltimore harbor struck the I-695 (Francis Scott Key) bridge. It collapsed and blocked shipping traffic into the Baltimore harbor.22

the entrance to the Baltimore harbor was blocked by the collapse of the I-695 (Francis Scott Key) bridge in March, 2024

Source: National Transportation Safety Board, NTSB B-Roll - Aerial Imagery of Francis Scott Key Bridge and Cargo Ship Dali

A 2023 US Department of Transportation report assessed the condition of the 14,068 bridges identified that year in Virginia. According to one news story:23

during the Civil War, the Union Army built temporary pontoon bridges to cross major rivers such as the Rappahannock River

Source: National Archives, Pontoon across Rappahannock River, Va.

cars crossed streams at shallow fords until bridges were constructed

Source: National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library, Motorists in Mitchell automobile fording a stream, Richmond, Virginia, 1911 Touring Club of America Good Roads Tour

the new Woodrow Wilson Bridge

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Woodrow Wilson Bridge

Maryland owns most of the American Legion Bridge over the Potomac River

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), I-495 Washington DC

all of the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) bridges and other infrastructure must be maintained and ultimately replaced

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Bridges and Culverts Map

bridges have been essential for transportation since wheeled vehicles were invented (University Boulevard under construction in Prince William County)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Ninth Street Bridge, crossing the James River in Richmond

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Richmond City Skyline

drawbridge at Great Bridge, completed in 2004

Source: US Army Corps of Engineers, Great Bridge, Bridge (080115-A-5177B-025)

bridge across the New River at Radford in 1949

Source: National Archives, New River Bridge, Radford, Virginia

1912 bridge over Gales Run on Chancellorsville Road (replaced with concrete bridge)

Source: National Archives, Washed Out Wooden Bridge, Virginia