demolition of the steel girders of the 1961 Woodrow Wilson Bridge in 2006

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project (July 17, 2007)

demolition of the steel girders of the 1961 Woodrow Wilson Bridge in 2006

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project (July 17, 2007)

At the start of the 20th Century, old bridges across the Potomac River were replaced and new bridges were constructed.

In 1904, the Pennsylvania Railroad built a new two-track railroad bridge. That eliminated the need to run trains over the Long Bridge, which had been constructed originally in 1835 and upgraded in 1872. The old Long Bridge continued to carry at least trolley traffic until 1906.

The historic Long Bridge was replaced in 1906, after 70 years of service and multiple repairs, with a new all-metal structure. The new bridge was named the Highway Bridge, since it carried no rail traffic. After that, the term "Long Bridge" was applied to just the 1904 railroad bridge.1

the 1906 Highway Bridge replaced the 1835 Long Bridge

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT), 14th Street Bridges 003

the 1906 Highway Bridge included trolley tracks

Source: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 14th Street bridge

The Key Bridge was built to replace the Aqueduct Bridge, a key part of the Alexandria Canal. The Aqueduct Bridge allowed boats on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal to reach the port at Alexandria, bypassing Georgetown. The Federal government purchased the bridge and, in 1886, it was converted to serve only wagon, horse and pedestrian traffic. An iron superstructure replaced the wooden trusses on top of the eight piers.

The stability of the bridge's pilings degraded, and after the usual extensive debate the US Congress authorized a replacement. The Francis Scott Key Bridge opened in 1923. The iron superstructure on the Aqueduct Bridge remained unto 1933, when it was removed as a public works project during the Great Depression.

Long Bridge is the oldest bridge currently crossing the Potomac River downstream of Great Falls. Ky Bridg is the oldest such bridge that carries cars.2

the Key Bridge replaced the Aqueduct Bridge in 1923

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial View Looking North Towards D. C. - Francis Scott Key Bridge

The Memorial Bridge opened on January 18, 1932. It was constructed after an incident in 1921 on the day of the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arlington National Cemetery. The large number of vehicles following the casket created a traffic jam on the Aqueduct Bridge. The delay almost caused President Warren G. Harding to miss the internment ceremony in Virginia.

The new Memorial Bridge physically and symbolically connected Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia to the Lincoln Memorial in the District of Columbia. Though the ends of Memorial Bridge were on opposite sides of the Potomac River, both were within the boundaries of the District. The southern edge of the Potomac River, the legal boundary between Virginia and the District of Columbia, was on the southern side of Boundary Channel.

The location of that boundary meant that the Federal Government was fully responsible for funding and building the bridge. The project did include a span within Virginia, constructed over Richmond Highway to provide access to Arlington Memorial Cemetery. Between 1932-38, the Arlington County road network was finally connected to the bridge when the George Washington Memorial Parkway was being developed.

both ends of the Arlington Memorial Bridge are within the boundaries of the District of Columbia

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

In 1932, the 2,100-foot long Arlington Memorial Bridge was the "longest, heaviest and fastest opening drawbridge in the world." After low bridges were constructed downstream, the drawspan was no longer opened after February 28, 1961.

The Memorial Bridge's 50-year lifespan was extended by multiple repair efforts, but in 2016, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) notified the National Park Service that the bridge would have to be closed in 2021 because more short-term repairs would not be acceptable. The rehabilitation included replacing the two wing spans of the draw bridge, with the fixed-in-place component covered by the original decorative metal arches on either side of the bridge.

Rehabilitation of the Memorial Bridge was completed in 2018-19, after the National Park Service and the District of Columbia were awarded a $90 million grant under the new Fostering Advancements in Shipping and Transportation for the Long-term Achievement of National Efficiencies (FASTLANE) program in 2016. Rehabilitation, like initial construction, was within the boundaries of the District of Columbia.3

Arlington Memorial Bridge Construction

Source: National Park Service

the Federal government funded rehabilitation of the Arlington Memorial Bridge within the District of Columbia

Source: National Park Service, Arlington Memorial Bridge Rehabilitation

The 1906 Highway Bridge stayed in service over 50 years. It was replaced with two separate bridges which were completed 12 years apart.

President Truman made the decision to build what became the 14th Street Bridge and the George Mason Memorial Bridge, the "twin bridges" with each carrying four lanes of traffic. There was an alternative proposal to build just one six-lane bridge at the site, which the National Capital Park and Planning Commission encouraged in order to preserve the scenic vista.

The claim that only six lanes were necessary was based on the assumption that another bridge would be constructed downstream to divert traffic around Washington. That ended up coming true. A bridge at Jones Point was authorized in 1954, and the initial six-lane Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge opened in 1961 as part of the Capital Beltway.4

The first of the twin bridges, the new 14th Street Bridge, was built to carry northbound traffic. It opened in 1950, after which the Highway Bridge carried just southbound traffic. With an optimistic perspective that the US Congress would fund construction of the second of the twin bridges, J. Willard Marriott built his first hotel on the Virginia side of the 14th Street Bridge. The Twin Bridges Marriott Motor Hotel opened in 1957, and at the time was the largest motor hotel in the United States.5

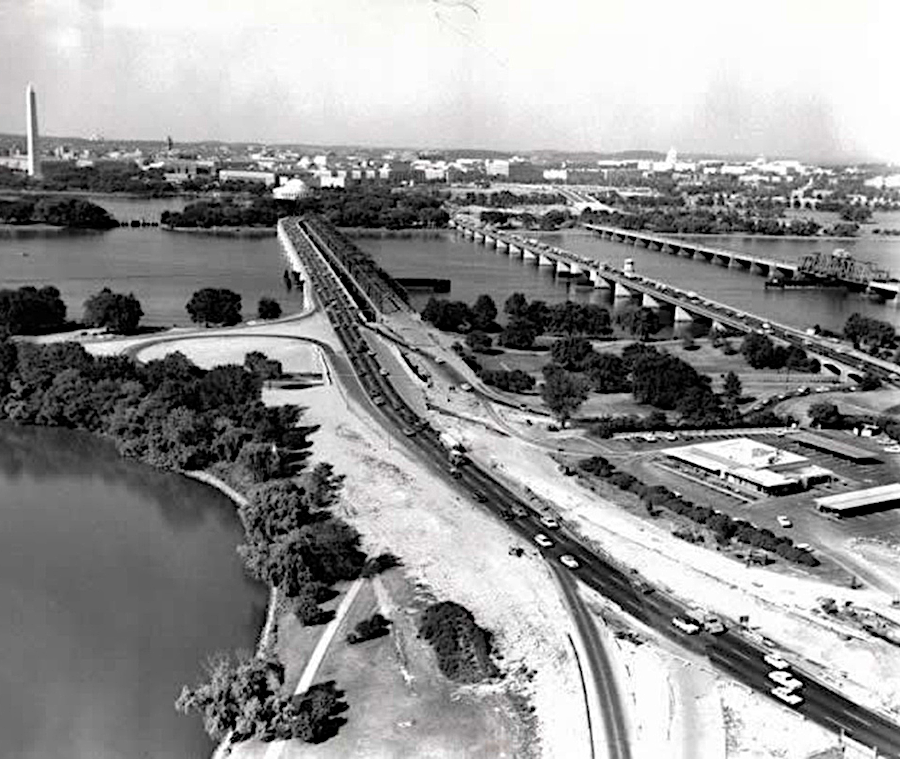

from left to right (going downstream): the 1906 Highway Bridge, 1950 14th Street Bridge, and 1904 Long Bridge

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT), 14th Street Bridges 016

To save money on the second of the twin bridges, the US Congress eliminated the proposal to include a drawbridge. It became the first bridge across tidal portion of the Potomac River that did not accommodate shipping.

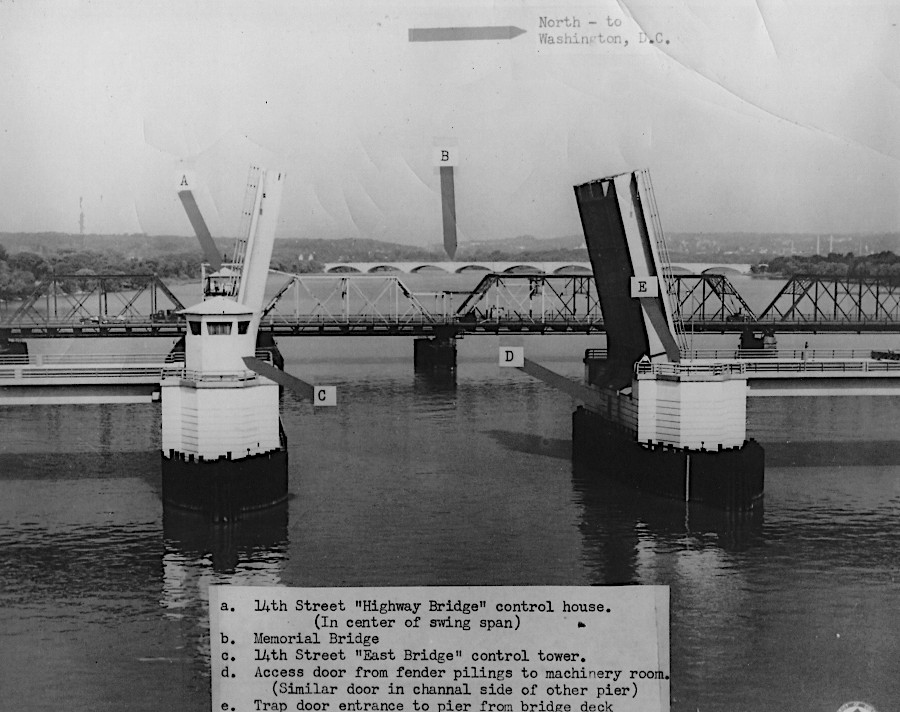

the 14th Street Bridge, completed in 1950, could open and allow ships to reach Georgetown

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT), 14th Street Bridges 007

After the George Mason Memorial Bridge opened in 1962, there were proposals to retain the 1906 Highway Bridge. Repair costs would have been too high, so it was dismantled starting in 1967. In 1969, one of the spans was floated downstream on a barge to the Naval Weapons Laboratory and used for target practice by US Navy pilots.

Floating the portion of the 1906 bridge downstream required opening the Long Bridge drawspan. That was its last opening. Since 1969, all ships going upstream of Long Bridge have been short enough to fit underneath it.6

the new George Mason Memorial Bridge, built upstream of the 1906 Highway Bridge, opened in 1962

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT), 14th Street Bridge (1960), New Southbound Span 14th Street Bridge, and

14th Street Bridge Complex (Various) (1961)

The 14th Street Bridge was officially renamed the Rochambeau Memorial Bridge in 1958 after the 175th anniversary of the Battle of Yorktown. Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, had led the French army south with George Washington's Continental army in 1781. Units of the French and American armies had crossed the Potomac River near the future site of the Rochambeau Memorial Bridge.

from left to right: George Mason Memorial Bridge (1962), the Highway Bridge (1906), the 14th Street Bridge (1950), and Long Bridge (1904)

Source: Federal Highway Administration, Moment in Time: How the Washington Monument Helped Solve a Bridge Impasse (1962)

looking towards Virginia as the Highway Bridge built in 1906 is dismantled and a new bridge contructed for northbound traffic

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT), 14th Street Bridges 016 and 14th Street Bridge Complex (Various)

In 1972, another new bridge was completed just south of the George Mason Memorial Bridge, where the 1906 Highway Bridge had been located. The new bridge was built for bus and carpool traffic, extending the highway lanes which were built in Virginia with the intent of reducing single occupancy vehicles so more people could be moved with fewer cars.7

In 1985, the label "Rochambeau Memorial Bridge" was shifted to the express lanes bridge built in 1972. The former 14th Street Bridge, built in 1950, was then named the Arland D. Williams Jr. Bridge.

That name honored a victim of the 1983 Air Florida airplane crash, which had taken off from National Airport but quickly plunged into the Potomac River. Williams had helped rescue others who survived before he finally drowned. The plane had clipped the 14th Street/Rochambeau Memorial Bridge before crashing into the river just upstream. Renaming that structure for Williams was most appropriate, but Rochambeau still has a bridge across the Potomac River honoring him.8

The last bridge constructed across the Potomac River in the 20th Century is part of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority's Metrorail system. The transit bridge was completed in 1983 and named for Charles R. Fenwick, a member of the Virginia General Assembly who had ben key to getting the rail transit system approved.9

the last bridge constructed across the Potomac River in the 20th Century was the Metrorail bridge named for Charles R. Fenwick

Source: Library of Congress, Aerial View Looking Southeast - Long Bridge, Spanning Potomac River near Jefferson Memorial, Washington, District of Columbia, DC (1992)

Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia have succeeded in negotiating boundary-crossing deals to replace bridges over the Potomac River, rather than disputing ownership rights. Virginia agreed to pay percentages of the construction costs based on more than just the percentage of the bridges located on the Virginia side of the boundary line.

Replacing the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, built in 1961, was necessary because traffic far exceeded its capacity. By 2004, 200,000 vehicles/day were crossing a bridge expected to carry 75,000 vehicles/day. There were eight lanes on either side of the bridge, but the bridge was a six-lane bottleneck. The project included new intersections and improvements on a 7.5 mile section of Interstate 95/495 (Capital Beltway).

Due to the legislation that authorized the bridge originally in 1954, the Woodrow Wilson Bridge ended up as the only one in the interstate highway system owned by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). It crossed land and water owned by Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Only 700 feet of the new bridge crossed the Potomac River within the jurisdiction of the District of Columbia, though that included the structure in the middle of the bridge from which a draw span operator can raise/lower the spans for ship passage.

The three local jurisdictions assumed responsibility for bridge operations and maintenance, with a District of Columbia employee as draw span operator. Bridge ownership became significant when maintenance and repair costs began to climb in the 1970's. The Federal Highway Administration noted:10

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1981 provided funding to resurface and improve "any bridge on the Interstate System which is both owned by the United States Government and located in two States and the District of Columbia." The two states and the District of Columbia agreed with each other on how to maintain the improved bridge, but in 1989 they refused to accept title to the structure. Leaving it in Federal ownership avoided accepting the costs to build a replacement bridge.11

As the owner, the Federal Highway Administration took the lead role in negotiating the replacement of the bridge. The Federal agency completed a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in 1991, then a supplemental draft in 1996 and a second supplemental in 1996.

Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia agreed to create a National Capital Region Woodrow Wilson Bridge and Tunnel Authority to own the bridge. The US Congress authorized the interstate compact, and the jurisdictions ratified it in 1996. The Federal Highway Administration used a 29-member Interagency Coordination Group to synchronize planning and design, and to resolve conflicts with other Federal, state, and local governmental agencies.

Later, Maryland and Virginia agreed to joint ownership of the new bridge. Once Maryland and Virginia agreed to own the new bridge, the District limited its role in the project to just commenting on drafts.

Jones Point lighthouse marks the southern tip of the District of Columbia

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project (July 17, 2007)

The preferred alternative in the 1997 Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was for a 12-lane bridge, but there was significant pressure to expand the scope of the study to consider the alternatives of a tunnel and a 10-lane bridge. At one point, the District Court for the District of Columbia ruled the Final Environmental Impact Statement was in violation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act.12

The Federal Highway Administration succeeded in convincing the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia that the "purpose and need" for the new bridge required 12 lanes. When it became clear that construction would require dredging more material than anticipated, another supplemental study and Environmental Impact Statement evaluated alternatives for disposal of dredged material. Eventually 500,000 cubic yards were barged to Port Tobacco in Charles County, Virginia and used to fill an old sand and gravel mining pit on land once part of historic Shirley Plantation.

Construction of the new Woodrow Wilson Bridge started in 1999. Half of the new bridge opened in 2006 and the other half in 2008. It was fully completed in 2013. Life expectancy of the new structure was estimated to be 75 years.

new Woodrow Wilson Bridge under construction (1961 bridge on left)

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project (July 17, 2007)

The new Woodrow Wilson Bridge had 12 lanes, but four were blocked off from vehicle traffic and designated for later Metrorail use. In 2025 in its draft Visualize 2050 long range plan and the 495 Southside Express Lanes study, the Virginia Department of Transportation proposed converting those four reserved lanes into High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes (two lanes in each direction). To preserve the future option of rail-based mass transit, one of the two lanes in each direction would be legally committed to future conversion into a rail line.

The 495 Southside Express Lanes proposal would create 11 additional miles of High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes on I-495 from Springfield to Oxon Hill in Maryland. That would complete the nearly 110-mile Express Lanes network in Northern Virginia, since a separate project extended such lanes on I-495 from Tysons to the American Legion Bridge at the end of 2025.

Prince George's County in Maryland opposed the 495 Southside Express Lanes project, while Fairfax Coounty in Virginia supported it in order to reduce traffic congestion. The opponents in Maryland, like those in Virginia, opposed privatizing the lanes and adding tolls. Their preferred alternative was to expand rail transit, including the new Metrorail Purple Line. Maryland officials also did not want to make it easier for their residents to cross the Potomac River and spent money in Northern Virginia, reducing tax revenues and jobs in Maryland.13

the 495 Southside Express Lanes proposal would add four High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes in the middle of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Location Public Hearing To Present Recommended Preferred Alternative (June 2025)

Only one bridge crosses the Potomac River downstream of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge.

The bridge carrying US 301 between King George County and Charles County was completed in 1940. At the time, the narrow two-lane structure, without shoulders and with no divider between its two lanes of traffic, was a welcome replacement for the ferries required to cross the Potomac River. It was rehabilitated in the 1980s, but 25 years later Maryland decided it was time to completely replace it.

all of the US 301 bridge across the Potomac River is in Maryland, except for the approach ramp in King George County

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

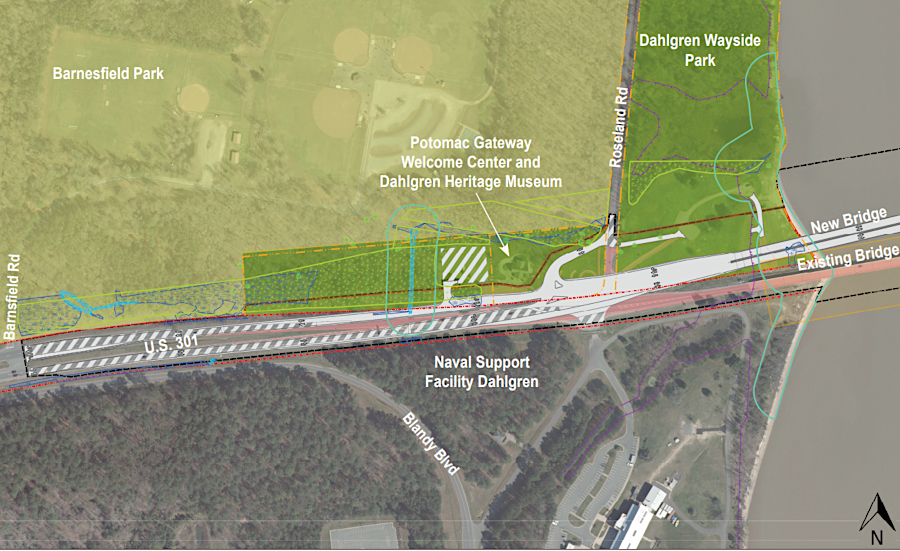

The replacement for the Gov. Harry W. Nice Memorial/Sen. Thomas "Mac" Middleton Bridge required building a new span through Wayside Park, the only public beach public beach in King George County. To replace the six acres impacted by the project, the Virginia Department of Transportation agreed to purchase 168 acres of replacement parkland for the county.

As part of the land purchase, King George County ended up with a waterfront home. It was worth almost $1 million as a residence, but required another $500,000 in upgrades before it could serve as a museum for local historical societies. That investment was a low priority for the county's parks and recreation program. To ensure the building was maintained, King George rented the house temporarily to newly-hired county staff that were searching for a local home to buy.

replacing the US 301 bridge impacted six acres of Wayside Park in King George County

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), Project Overview -

Conceptual Design: Virginia Approach, Harry W. Nice / Thomas "Mac" Middleton Bridge Replacement

The "practical design" for the $463 million replacement bridge, adopted by the Maryland Department of Transportation, proposed to eliminate the shared-use path for bicycles/pedestrians on the bridge in order to reduce costs. The Maryland Transportation Authority estimated that a barrier-protected pedestrian lane would add $64 million in costs. Initially it would service just 46 bike/pedestrian trips per day, and population growth in Charles or King George counties was not expected to increase the number substantially. Rather than make an investment of $1.3 million per daily user, Maryland officials chose to allocate the $64 million to I-95 improvements instead.

The George Washington Regional Commission and the Fredericksburg Area Metropolitan Planning Organization could only express their concerns about the change; the Virginia-based organizations had no authority to shape Maryland's design decisions. Maryland was providing $463 million in funding and Virginia was contributing only $13 million, dealing only with the project on its side of the state boundary. Charles County declined to accept the old bridge and fund the maintenance required to keep it as a separate pedestrian/bicycle crossing.

Bike and pedestrian advocates requested the Maryland Transportation Authority to preserve the old bridge rather than spend $15-23 million to demolish it. Both the Republican and Democratic candidates in the 2022 race for governor said they were concerned about the demolition, but the state agency raced to demolish it before the end of Gov. Larry Hogan's term. The authority claimed that maintaining the old bridge would cost $50 million over the next 30 years.14

the replacement bridge for US 301 had four lanes for vehicles, but no path for bikers/pedestrians

Source: Maryland Department of Transportation, Nice/Middleton Bridge Project – Home

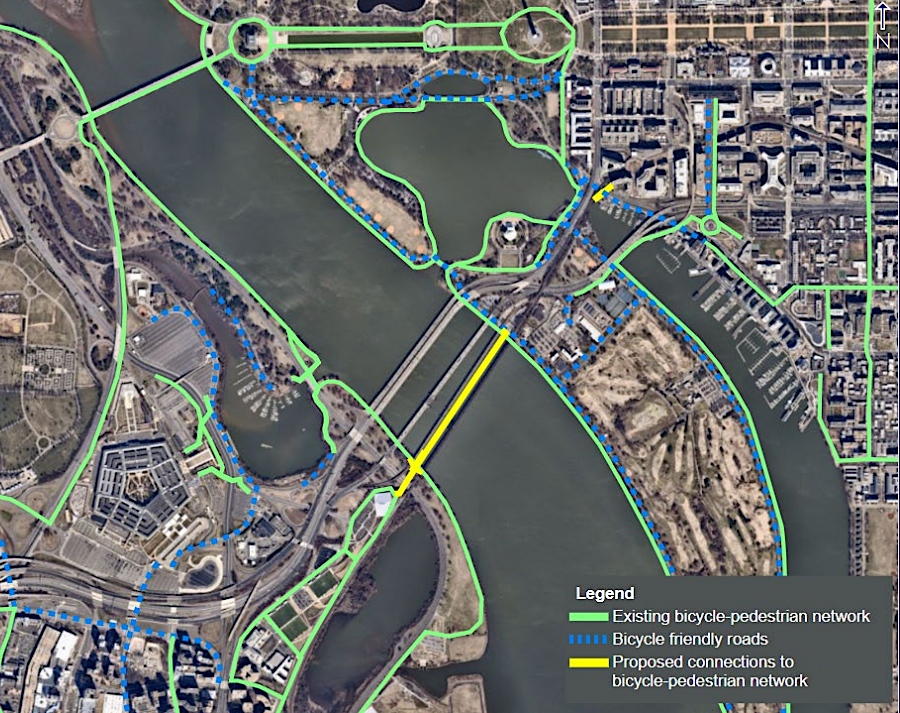

the new Long Bridge was designed to enhance the existing bicycle-pedestrian network, unlike the replacement for the Gov. Harry W. Nice Memorial/Sen. Thomas "Mac" Middleton Bridge

Source: Virginia Passenger Rail Authority, Long Bridge Project

Preliminary Engineering Phase

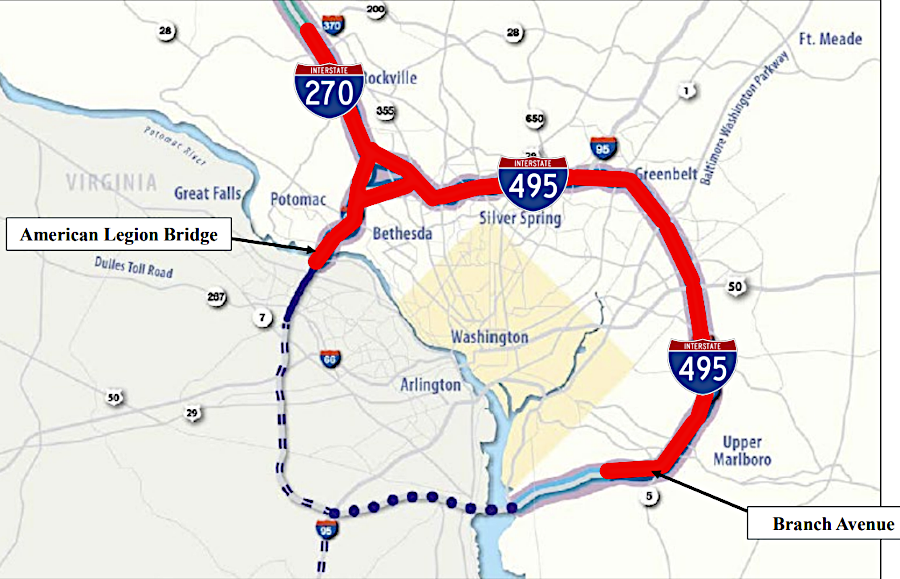

Upstream of Washington DC, the Cabin John Bridge was built in 1962 to carry the Capital Beltway (I-495) across the Potomac River. The bridge, renamed the American Legion Bridge in 1969, had eight lanes for traffic (four in each direction) plus two auxiliary lanes for merging traffic. It became a traffic chokepoint as Maryland residents commuted across it to jobs near Dulles and Tysons while Virginia residents drove to jobs in Bethesda and along I-270.

Any vehicle accident/breakdown created significant delays because the bridge had no shoulder lanes. Maryland officials calculated that each minute before a vehicle was removed created four additional minutes of excess congestion.

One option to reduce congestion was to build a new bridge across the Potomac River further upstream, as originally planned in the 1950's. The Cabin John Bridge was to be the inner beltway crossing, with an outer beltway bridge further upstream carrying much of the expected traffic.

Loudoun County officials have supported a new bridge connecting to I-270 in Maryland. The "techway" bridge would facilitate expansion of high-tech businesses in Northern Virginia by enabling more Maryland workers to commute into Virginia. Loudoun County would get the tax revenue from increased business activity, while Maryland would have to absorb the costs of public schools for the families of those commuters.

Montgomery County, Maryland strongly opposed the concept of a new highway cutting through the county's western agricultural preserve, where wealthy and influential residents lived in multi-million mansions. Equally influential Virginia residents in the Great Falls area opposed a new Potomac River bridge that might be located near them.

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan proposed a total replacement, comparable to the way the 1961 Woodrow Wilson Bridge was replaced in 2008. The new 14-lane bridge would cost $1 billion, funded in part through a public-private partnership with the right to collect tolls for 50 years incentivizing the private investment. A new bridge would expand capacity and, if build in time, avoid the cost of a major redecking between 2030-2040.

In 2019, the governors of Virginia and Maryland signed a "Capital Beltway Accord" to replace the American Legion Bridge. Gov. Hogan championed a design to add shoulders, four new toll lanes for vehicles, and a bike/pedestrian path. In the High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes, no toll would be charged for buses or cars with at least three people.

Smart growth advocates pushed for a design that included bus rapid transit and future light rail transit (as did the new Woodrow Wilson Bridge). They claimed the new car-centric bridge would just shift the chokepoint to where the Beltway narrows at Old Georgetown Road in Bethesda, rather than address the fundamental imbalance between transportation capacity vs. demand.

Just 21% of the American Legion Bridge is on the Virginia side of the state border, and Virginia agreed to pay 21% of the costs to replace the eight existing lanes which will remain open for general purpose traffic. However, Virginia committed to pay 100% of the cost for two new northbound toll lanes from the George Washington Parkway to River Road in Maryland, and Maryland agreed to pay 100% of the cost of equivalent southbound toll lanes.

In essence, Virginia committed to cover 50% of the costs for adding new toll lanes to a bridge which was 79% in Maryland. Virginia also arranged to extend its toll lanes on the Capital Beltway the last three miles from Tysons to the Potomac River by 2025, whether or not the new bridge was approved and funded.

the American Legion Bridge in 2019

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), I-495 Washington DC

Both states anticipated that taxpayers could finance none of the new construction. Instead, the states would sign public-private partnerships with private corporations which would build the replacement lanes for the American Legion Bridge, and Virginia would share more than 21% of the toll revenues to facilitate completion of the project. Separately, Virginia also extended its public-private partnership with Transurban to extend the I-495 Express Lanes an additional 2.5 miles to connect with the American Legion project.

Virginia started its expansion of I-495 toll lanes in 2022; construction was near completion by the end of 2025. The Maryland Department of Transportation awarded a contract to Fluor/Transurban in 2021. In 2022 the Federal Highway Administration approved the Record of Decision for the Environmental Impact Statement, with a new bridge adding two new High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes in either direction on I-495.

After continued opposition from Montgomery County officials, the Biden Administration and a new Maryland governor, Wes Moore, delayed the project. Fluor/Transurban withdrew from the project in 2023. As a result, Virginia completed a 14-lane I-495 to the edge of the Potomac River but the American Region Bridge remained an eight-lane chokepoint there.15

the American Legion Bridge replacement was proposed as part of an expansion of I-495 and I-270

Source: National Capital Planning Commission, I-270 & I-495 Managed Lanes Study

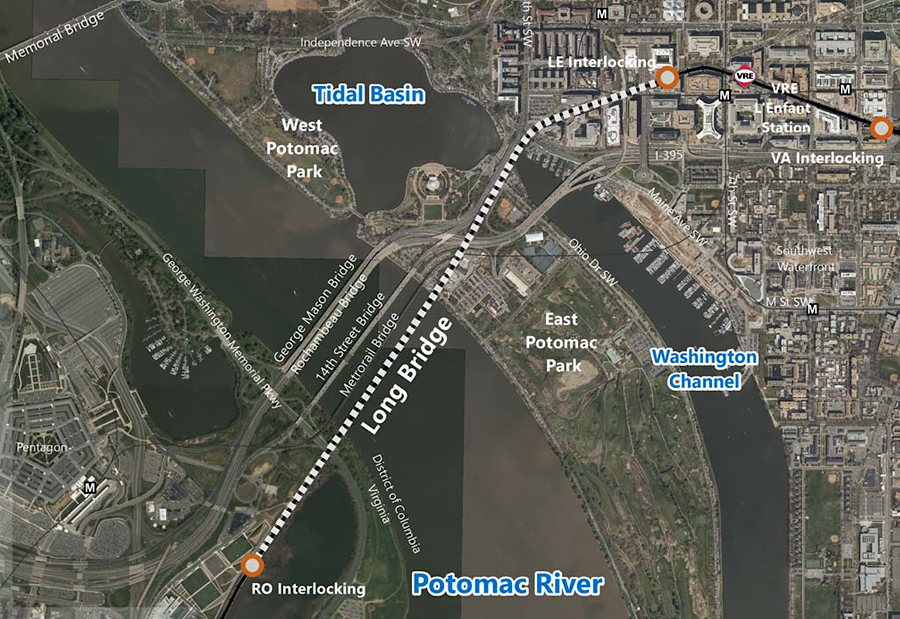

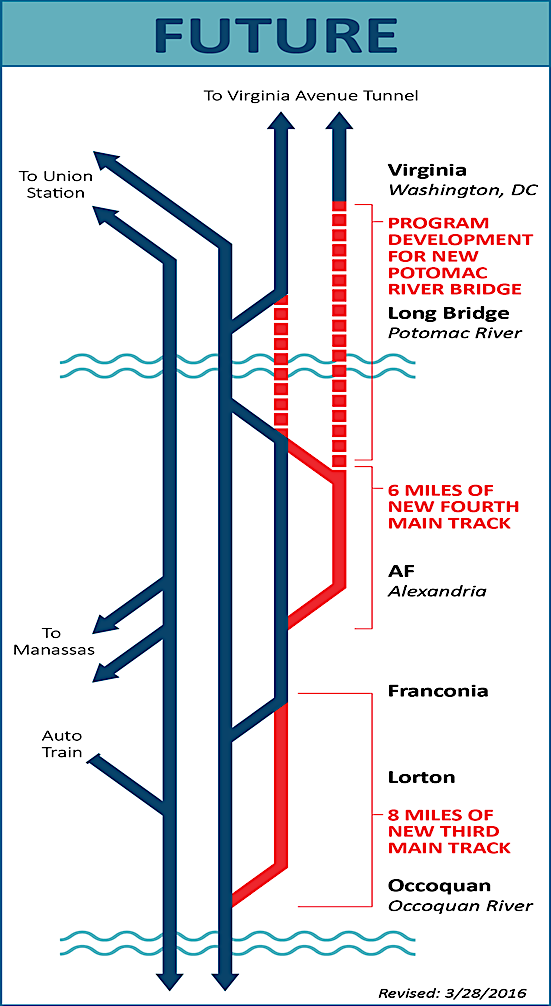

Replacing the Long Bridge over the Potomac River, expanding from two to four railroad tracks, required negotiating a deal between Virginia, the District of Columbia, and the Federal Railroad Administration. The District Department of Transportation completed the initial environmental reviews and chose the preferred alternative. The decision was to repair the existing two-track bridge, construct a new two-track bridge to double train capacity, and to build a separate bike and pedestrian bridge to increase non-motorized mobility.16

In December 2019, Governor Northam announced a plan to spend $3.7 billion to acquire right-of-way owned by CSXT and build two new tracks from L'Enfant to Alexandria. Virginia agreed to build a new, $1.9 billion two-track railroad bridge parallel to the existing Long Bridge plus a separate bike/pedestrian bridge across the Potomac River.

To construct the new two-track railroad bridge over the Potomac River, the District Department of Transportation agreed to transfer sponsorship of the Long Bridge project to Virginia following completion of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The state expected to pay 1/3 of the cost, and get another 1/3 from the Federal government and Amtrak. Maryland, the District of Columbia, the Virginia Railway Express (VRE), and regional transportation commissions were expected to provide the last 1/3.17

modern 14th Street Bridge Complex includes 1962 George Mason Memorial Bridge at upstream end (to left) and 1904 Long Bridge at downstream end (to right)

Source: Wikipedia, 14th Street bridges

Teddy Roosevelt Bridge under construction, 1962

Source: District of Columbia Department of Transportation (DDOT), Theodore Roosevelt Bridge

Virginia decided to purchase CSXT right-of-way so it could build two new tracks from L'Enfant in the District of Columbia to Alexandria

Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), DRPT Overview (April 23, 2018)

two additional tracks (red) will be added parallel to Long Bridge and its approaches

Source: Virginia Department Transportation, Woodrow Wilson Bridge Project (July 17, 2007)