the Little River Turnpike Company collected tolls for crossing the bridge between 1827-1896

Source: National Park Service, Little River Turnpike Bridge

US 11 uses Natural Bridge to cross Cedar Creek, so Natural Bridge is the oldest bridge in the United States used for an active highway. The oldest human-created bridge, the Frankford Avenue Bridge in Philadelphia, dates back to only 1697.1

All human-created bridges in Virginia are far younger than Natural Bridge. The first human-created bridges have disappeared. All the stream crossings created by the Native Americans, using logs or upgrading beaver dams, have washed away.

English colonists built their first bridge in 1611 to get from Jamestown Island to the mainland, but that wooden structure is long gone.2

Four stone bridges in the state built in the 1800's are still part of the highway network used by cars and trucks regularly.3

The oldest bridge still in use in Virginia is the Little River bridge at Aldie in Loudoun County, completed between 1826-27 by the Little River Turnpike Company. The company collected tolls until 1896. After the company dissolved, Loudoun County owned the bridge. It was transferred to the state after passage of the Byrd Road Act in 1932.

The bridge supports what is now modern US 50 past the historic Aldie Mill, despite floods and vehicles crashing into it. The downstream parapet was rebuilt after being hit by a construction trailer in 1998, and the masonry structure still retains its historic character.4

The Virginia Department of Transportation sought ways to minimize the average daily traffic load of 13,000 vehicles/day, as measured in 2001. It proposed building a new highway bypass around Aldie:5

the Little River Turnpike Company collected tolls for crossing the bridge between 1827-1896

Source: National Park Service, Little River Turnpike Bridge

Residents in the area opposed new roads through the rural countryside designed to speed up traffic at the expense of the setting. The Route 50 Corridor Coalition proposed retaining the bridge and using it as a traffic calming device. In the late 1990's, the coalition noted:6

Despite culture clashes, the state highway engineers and landscape protectors finally negotiated a joint plan for implementing innovative approaches to managing traffic through western Loudoun County without widening roads or building bypasses. Sen. John Warner, who lived near the area, got a Federal appropriation and the state implemented design changes to slow traffic to safe speeds, rather than facilitate faster driving. The models predicting traffic growth ended up being in error; in 2017, traffic across Little River bridge was less than 8,000 vehicles/day.7

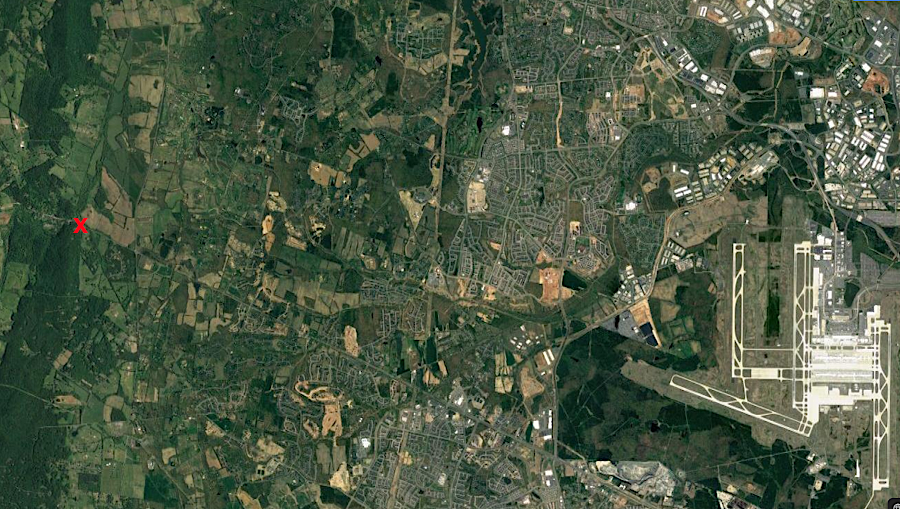

the rural character of the area around Little River bridge stands in clear contrast to the suburban sprawl five miles to the east

Source: GoogleMaps

The Little River bridge is younger than West Virginia's oldest. If the two sections of Virginia had not divided in 1863, the oldest functional highway bridge would be the Elm Grove Stone Arch (Monument Place) Bridge, constructed in 1817 to carry the National Road (US 40) over Little Wheeling Creek in Wheeling.8

Hibbs Bridge takes Route 734 (Snickersville Turnpike) across Beaverdam Creek dates back to 1829. Hibbs Bridge replaced a wooden bridge that was destroyed in an 1822 flood, using two humped stone arches to cross the stream. The original road surface on top included a cover of dirt for the 21' 4" wide road surface inside the parapet walls, which got an asphalt coating in the 20th Century.9

In the 1820's, the Snickers Gap Turnpike extended 14 miles from the end of the Little River Turnpike at Aldie to Snickersville (now Bluemont) at Snickers Gap. It connected there with the Alexandria-Winchester road (now Route 7) crossed the Blue Ridge.

Hibbs Bridge was constructed to carry Snickers Gap Turnpike across Beaverdam Creek in 1829

Source: Library of Congress, Map of part of Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland

The stone bridge was built to be a permanent structure; it has proven to be capable of withstanding floods for nearly two centuries. The Snickers Gap Turnpike Company transferred ownership to Loudoun County in 1869. The bridge was incorporated into the state's secondary roads system after passage of the Byrd Road Act in 1932.

The greatest threat to Hibbs Bridge turned out to be a 1994 plan by the Virginia Department of Transportation's highway engineers. The state agency proposed to build a bypass near the historic structure. The bypass with a new bridge across Beaverdam Creek would allow the stone bridge to be preserved as an amenity, and also eliminate the 10mph curve in the road to speed traffic across Beaverdam Creek.

The 1829 structure was too narrow for modern vehicles to pass at full speed, and the mortar holding the stones together had weakened and threatened the stability of the bridge. However, Hibbs Bridge was not a safety hazard with a high number of accidents.

Rural residents in Loudoun County supported preservation rather than replacement of the bridge. The Snickersville Turnpike Association led a long effort to force the Virginia Department of Transportation to repair rather than replace Hibbs Bridge. When local resistance to the bypass became clear, the state agency proposed to rebuild and widen Hibbs Bridge. Some of the original stones would be used on the exterior of the new structure, an approach one resident described as "Disney recreating history."

In western Loudoun County, preserving the local culture in the shadow of the Washington metropolitan area steady growth was more important than speeding up traffic on a lightly used road. Replacing a unique setting with "Anyroad, VA" was seen as unacceptable change.

Local officials responded to the local concerns. A county supervisor commented on the conflict between the residents and the highway engineers who prioritized traffic movement:10

The Virginia Department of Transportation agreed to retain the bridge as part of the highway system, and Loudoun County agreed to assume costs for its maintenance In 2007, major rehabilitation improved its strength and durability. The bridge's capacity was not upgraded; the posted weight limit remained at 6 tons. In 2001, however, a highway report observed:11

In Nelson County, Route 606 crosses Owens Creek on a stone viaduct built in 1835 for the James River and Kanawha Canal. The old canal bed was filled and converted into a highway, and the viaduct/bridge has been functional for almost two centuries.

the Owens Creek bridge was constructed in 1835 originally as a viaduct for the James River and Kanawha Canal

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.100)

A masonry bridge built by the James River and Kanawha Canal is also in use in Lynchburg. That bridge, which crossed the canal and is now at the James River end of 9th Street downhill from the courthouse, was constructed in 1839. When the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad replaced the canal, its tracks ran beneath the bridge.

the 1839 bridge over the James River and Kanawha Canal in Lynchburg

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

All other stone masonry arch bridges remaining in Virginia were constructed for turnpikes prior to the Civil War, or by railroads after the war to carry highway traffic over or under railroad lines .

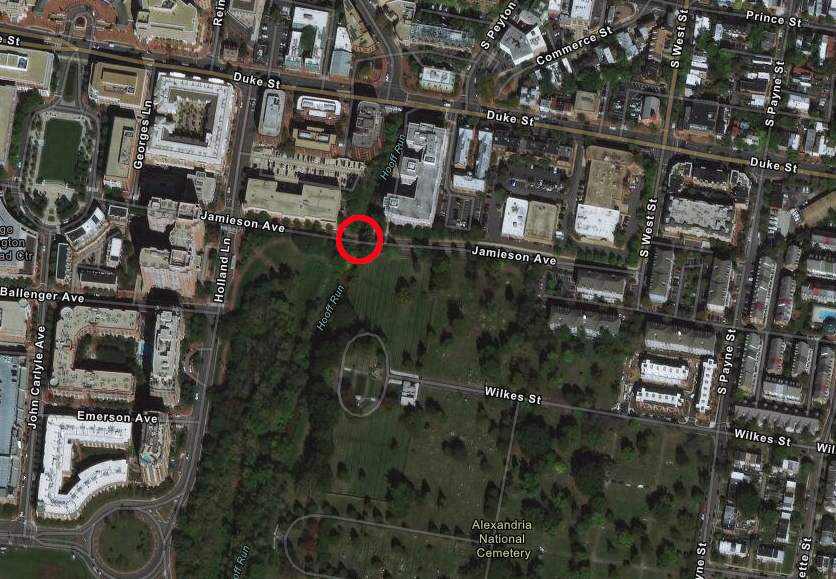

In Alexandria, a re-purposed 1856 Orange and Alexandria Railroad bridge carries Jamieson Avenue over Hooff's Run. The tracks and railroad ties were removed in 1990, and an asphalt roadbed now permits modern cars to cross the creek via the historic bridge. The equivalent bridge over Hooff's Run at Duke Street has not survived.12

the 1856 Orange and Alexandria Railroad bridge is still in use in Alexandria

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

The oldest stone bridge remaining in Virginia, but no longer carrying traffic, spans Goose Creek in Loudoun County. It is no longer carrying traffic; the bridge is maintained as a historic site rather than as transportation infrastructure. The bridge was constructed, perhaps as early as 1801-03, as part of the Ashby's Gap Turnpike to extend the Little River Turnpike across the Blue Ridge to the Shenandoah River. Route 50 was rerouted and modern traffic stopped using the bridge in 1957.13

The stone bridge over Falling Creek in Chesterfield County was completed in 1823. It provided the first permanent bridge over that stream, offering a road 20.5 feet wide on the Manchester-Petersburg Turnpike. Prior to its completion, travelers between Petersburg-Richmond would cross the James River on a ferry to get from Osbornes in Chesterfield County to the north shore in Henrico County.

The bridge stayed in use until 1931. The historic structure was incorporated into the Falling Creek Wayside, the first wayside established along Virginia's highways, and maintained as a pedestrian crossing. Today it is located in the median between the northbound and southbound lanes of Route 1.

Much of the Falling Creek bridge was washed away during Hurricane Gaston in 2004. Only the stone arches survived; the parapets and roadbed were washed downstream towards the site of the 1610 Falling Creek Ironworks and a 1750-1781 iron forge.

Chesterfield County plans for a museum and park at that site could lead to restoration of the stone bridge. That could require raising the elevation of the bridge, which was built without sufficient capacity to allow floodwaters to pass. One option is to put a new pedestrian bridge on top of the arches, rather than a full rehabilitation that would be at risk in the next major flood on Falling Creek.14

the Falling Creek bridge was damaged heavily by Hurricane Gaston in 2004

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.103)

The stone bridge over Broad Run in Loudoun County on Leesburg Turnpike (Route 7) was washed away by the floodwaters of Hurricane Agnes in 1972. Only the abutments remain today.

The Broad Run bridge stayed in use between 1820-1949, when it was "retired" after construction of a new concrete and steel structure. The adjacent toll house was used until the tolls were abandoned at the start of the Civil War, and it still survives as part of a private residence.15

the toll house on the Leesburg Turnpike at the site of the Broad Run bridge still remains (as private property)

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

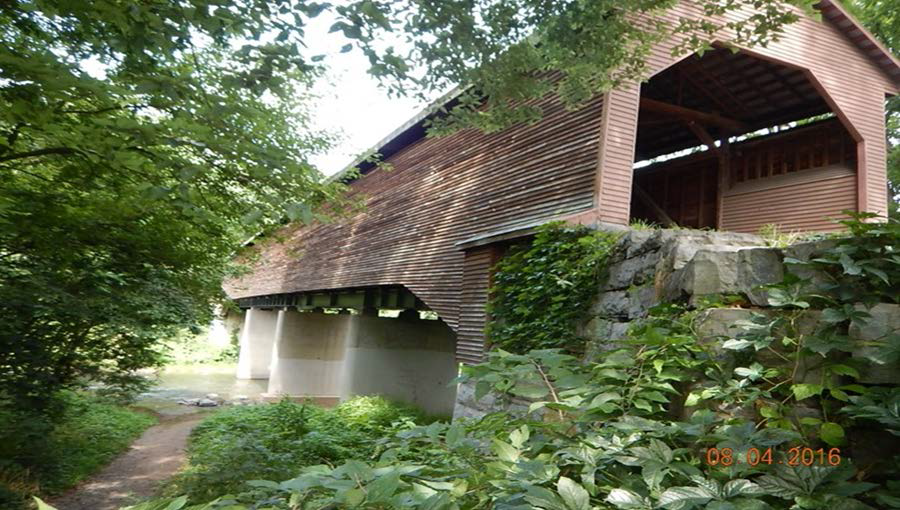

Only one covered bridge is Virginia is still part of the state highway system and used by vehicles. The Meems Bottom Covered Bridge over the North Fork of the Shenandoah River in Shenandoah County was completed in 1893. After arsonists burned it in 1976, the structure was rebuilt with some of the original wooden timbers. The concrete piers and steel beams which support the rebuilt bridge give it a hybrid historic-modern appearance.16

Meems Bottom Bridge was rebuilt after an arson fire in 1976

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.134)

The oldest surviving covered bridge in Virginia, the Humpback Bridge, was built by the James River and Kanawha Turnpike in 1857. It crosses Dunlap Creek, west of Covington in Alleghany County. Vehicles stopped using it when US 60 was realigned in 1929, and it was used as a hay barn. The bridge was restored for pedestrian use in 1953-4 and became the centerpiece of a local park. It is the only remaining trussed arch covered bridge in the United States; all others have been removed or destroyed.

Floods did not wash the Humpback Bridge away in part because it was constructed without a center pier in the middle of the creek; the "hump" in the middle shifts stress to the abutments successfully.17

the Humpback Bridge in Alleghany County is the oldest remaining covered bridge in Virginia

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Humpback Bridge

Humpback Bridge stopped carrying vehicles in 1929

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.131)

The first covered bridge built in Virginia was the Clearwater Park bridge. It was built across the Jackson River in Alleghany County in 1834, and washed away in 1887. .

The wooden roof and walls on covered bridges were added to delay the natural decay of the wooden structures due to rain, ice, and even sunlight. Covering provided no protection against floods, however. The Bob White Covered Bridge, crossing the Smith River in Patrick County, was destroyed in a 2015 flood. The cover over the 1919 C.K. Reynolds Covered Bridge blew down in a 2017 storm, leaving Virginia with just six remaining covered bridges.18

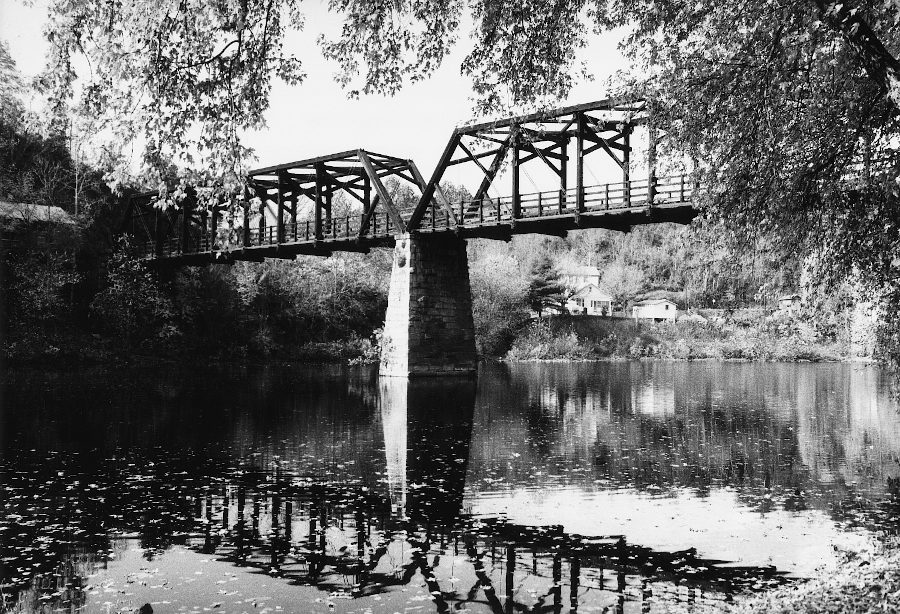

The Springwood Truss Bridge in Botetourt County was Virginia's last remaining major, all-wooden bridge. The three spans of wooden trusses were built by the Richmond and Alleghany Railroad in 1884, to allow wagons to cross the James River. The "Election Day Flood" of 1985, spawned by Hurricane Juan, damaged the bridge to the point where it had to be removed. The structure had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, so removal triggered delisting by the Keeper of the National Register in 2001.19

the last major bridge with all-wooden support timbers, the Springwood Truss Bridge built in 1884 over the James River in Botetourt County, was removed after a 1985 flood

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 011-0103 Springwood Truss Bridge *Delisted

Waterloo Bridge across the Rappahannock River is Virginia's oldest metal truss bridge still in the highway system and intended to carry vehicles. The structure, made of wrought iron, cast iron, and possibly an early form of steel, has linked Culpeper and Fauquier counties since 1878.

Waterloo Bridge, before rehabilitation in 2020-2021

Source: Virginia Transportation Research Council, A Management Plan for Historic Bridges in Virginia: The 2017 Update (p.142)

Due to deterioration of the metal components, in the 1990's the one-lane bridge was posted with a weight limit of just 3 tons. After a truck caused significant superstructure damage in 2008, the Virginia Department of Transportation added "no trucks" signs and a warning that only one vehicle at a time should be on the bridge. In 2014 the bridge was completely closed for safety reasons, forcing 680 vehicles/day to find an alternate route.20

at one point, Waterloo Bridge was limited to one vehicle at a time

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Waterloo Bridge: Conceptual Field Study

Waterloo Bridge was closed in 2014

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Waterloo Bridge

The Virginia Department of Transportation considered rehabilitating Waterloo Bridge, replacing it, or transforming it into a shared use path for pedestrians, bicyclists and other non-motorized users. Local community involvement was intense, and ultimately the decision was to repair the bridge and reopen it for vehicle use. The coating of paint made unclear the extent of the deterioration of the metal parts, and the original wrought iron varied in strength due to the manufacturing process in the 1870's.

Rather than repair the bridge in place, especially loop welded eyebars and laminated die forged eyebars that suffer from metal fatigue, the entire truss was lifted off of the foundations and moved to the Culpeper County shoreline. It took eight minutes for a crane to move the 30-ton truss. The Virginia Department of Transportation scheduled a year to disassemble and repair it on the ground before putting it back on the piers and opening it to cars.21

deterioration of pin connections and truss stringers was evident, though obscured by paint

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Waterloo Bridge: Conceptual Field Study (p.A3)

local area residents rejected the option of replacing Waterloo Bridge with just a shared use path, no cars allowed

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Waterloo Bridge: Conceptual Field Study (Figure F2)

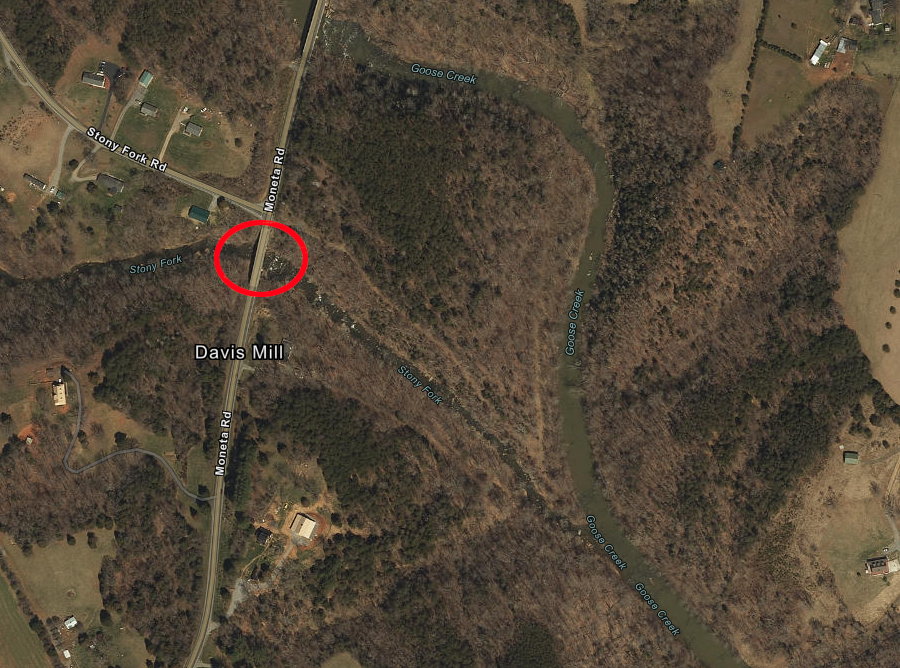

The oldest remaining metal highway bridge in Virginia is one that is no longer in service for vehicles, but has been preserved as a historic artifact. The 12' wide structure was built in 1878, using the Bowstring Truss design. Its original location is believed to have been across Stony Fork of Goose Creek in Bedford County, on the New London and Rocky Mount Turnpike (now Route 122 - Moneta Road).

the oldest remaining metal bridge in Virginia is thought to have crossed Stony Fork of Goose Creek in Bedford County in 1878

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

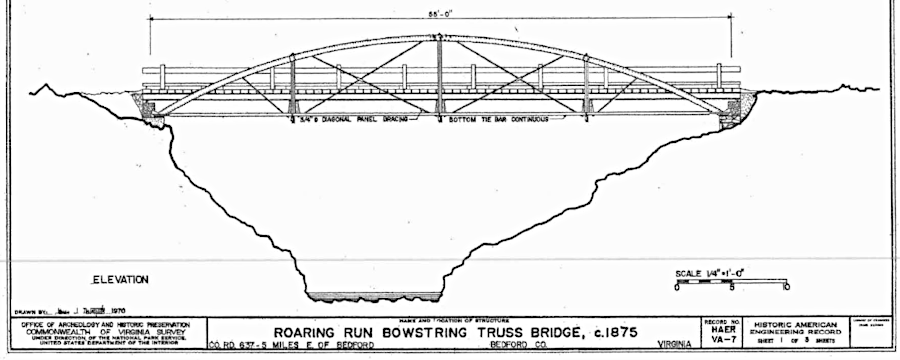

The bridge was moved about 20 miles for Route 637 to cross Roaring Run, a tributary of Big Otter River north of Goode. In 1977, after a new bridge replaced it, the metal framework was reinstalled at the Ironto Rest Area on I-81 in Montgomery County. It is now restricted to pedestrian use only.22

the Bowstring Truss Bridge carried cars across Roaring Run in Bedford County until 1977

Source: Library of Congress, Roaring Run Bowstring Truss Bridge, Spanning Roaring Run, State Route 657, Bedford, Bedford City, VA

the oldest metal bridge in Virginia may be the Bowstring Truss Bridge, originally installed in Bedford County in 1878

Source: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Bowstring Truss Bridge

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) identified 55 historically significant bridges in 2001. It concluded that metal truss bridges built before 1890 were constructed of wrought iron, while later bridges were made with steel components.

However, efforts to preserve one bridge revealed that wrought iron was used as late as 1925. Virginia Department of Transportation attempted to preserve the 1889 Featherbed Lane bridge over Catoctin Creek in 2003. It stripped off the paint and galvanized ("metallized") the exposed metal parks, adding a coating of zinc/aluminum alloys.

Soon, cracks revealed that a chemical interaction was occurring; some of the underlaying parts were wrought iron. The cracks weakened the structure, and a 3-ton weight limit was imposed. However, drivers still ignore such limits. The bridge over Big Walker Creek in Giles County was labeled with an 8-ton limit, but it collapsed as a concrete truck weighing over 26 tons tried to cross.23

The oldest bridge built completely from reinforced concrete still remaining is a 1904 railroad underpass, as determined in a survey by the Virginia Transportation Research Council. The double arch structure carries Naomi Road beneath the CSX railroad in Stafford County. A 1901 Norfolk and Western Railroad masonry arch bridge outside of Abingdon in Washington County has a concrete coating over the original masonry arch.24

Sinking Creek Bridge in Giles County

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Clover Hollow