looking towards Norfolk across the Berkley Bridge, from eastern portal of Downtown Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Downtown Tunnel and the Berkley Bridge east of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River

looking towards Norfolk across the Berkley Bridge, from eastern portal of Downtown Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Downtown Tunnel and the Berkley Bridge east of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River

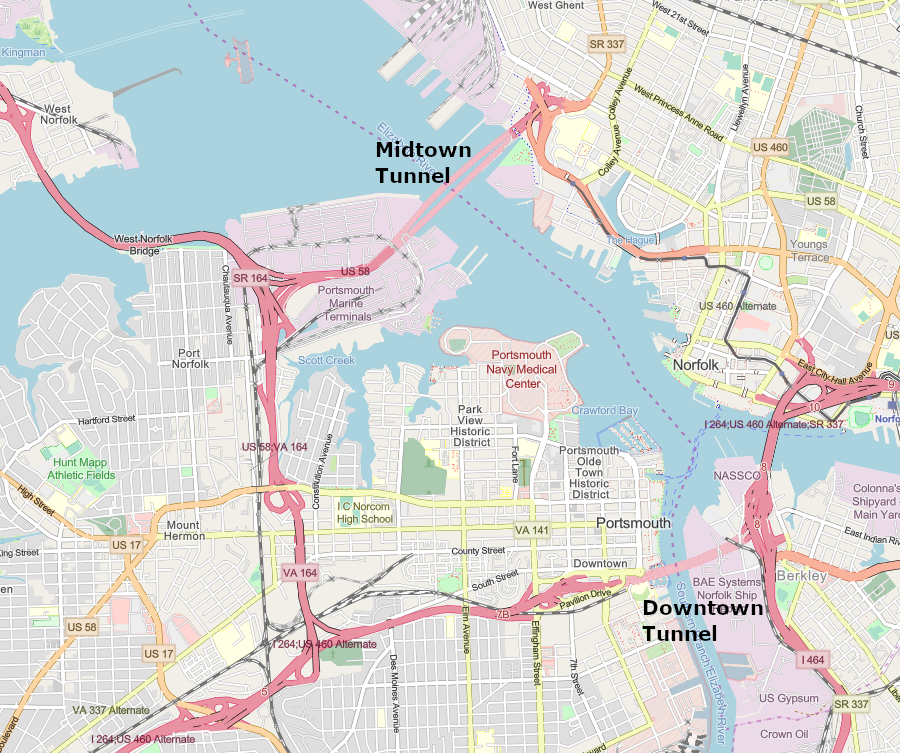

The first underwater tunnel constructed for vehicles in Virginia was the Downtown Tunnel underneath the Elizabeth River, connecting the cities of Portsmouth and Norfolk. A two-lane tunnel opened in 1952, and is now used for westbound traffic. Another two-lane parallel tunnel, now housing the eastbound lanes, was completed in 1987.

the oldest underwater tunnel in Virginia is the westbound half of the Downton Tunnel, built beneath the Elizabeth River in 1952

Source: National Archives, Tunnel under the Elizabeth River, between Berkley and Norfolk, Virginia

building the second tube of the Downtown Tunnel, now used for eastbound traffic, in 1983

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), RTS_0866a (by John Beilhart)

Downtown Tunnel, underneath the Elizabeth River

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), RTS_0866a (by Tom Saunders)

East-bound drivers going from Portsmouth to Norfolk first go underneath the South Branch of the Elizabeth River in the Downtown Tunnel, then use the Berkley Bridge to cross the East Branch of the Elizabeth River.

Vehicles on I-264 going from Portsmouth to downtown Norfolk travel first underneath the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River via the Downtown Tunnel, then take the Berkley Bridge across the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River. Berkley Bridge is a drawbridge. Without a tunnel that allows ship passage at all times, traffic must stop when the Berkley Bridge is opened up to four times each day on Monday-Friday.1

the first highway tunnel to Norfolk linked it to Portsmouth, and passed underneath the Elizabeth River

Source: Boston Public Library, Tichnor Brothers Postcard Collection, Portsmouth entrance to Norfolk - Portsmouth, Virginia Tunnel

The first two lanes of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel opened in 1957. It carries I-64 between the cities of Hampton and Virginia Beach. It was doubled to a four-lane facility in 1976. In 2016, the Commonwealth Transportation Board approved expanding the tunnel. Twin two-lane tunnels will be bored through the sediments west of the existing eastbound tunnel. The additional four lanes will carry all eastbound traffic headed to Norfolk, while the four lanes of the existing two tunnels will carry all westbound traffic headed to Hampton.2

Between 1957-76, drivers using the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel paid a toll. The revenue was used to pay off the 20-year bonds that had financed initial construction.

the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, looking towards Norfolk and Willoughby Spit

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Expansion Project, DBE/SWaM Opportunity Event (September 11, 2019)

The new two lanes were funded primarily by the Federal government, as part of I-64 construction. When they opened, the bonds were being paid off. The state chose to eliminate tolls on the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel and simultaneously on the James River Bridge upstream, and on the Coleman Bridge over the York River.

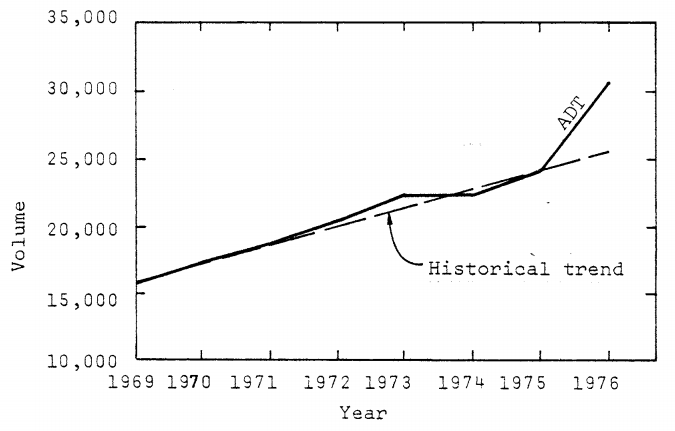

The number of vehicles using the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel quickly increased by 30% more than the historical trend. A Virginia Highway & Transportation Research Council report noted a year later:3

when tolls on the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel were eliminated in 1976, Average Daily Traffic (ADT) volumes increased far beyond the historical trendline

Source: Virginia Highway & Transportation Research Council, Impact Of Removal Of Tolls On Travel In Tidewater Virginia, Volume I- Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (Figure 2)

The fragmented political jurisdictions on the north and south sides of Hampton Roads finally agreed that their top transportation priority was to double the capacity of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. Once there was united support, the General Assembly authorized new regional sales and gas taxes for the $3.8 billion project.

In 2022, a Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) began digging twin two-lane tunnels parallel to the existing tunnels, but 50' deeper. The bridges were also widened, along with I-64 on the northern and southern ends, so eight lanes of traffic could cross the water. The Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel expansion was largest construction project in the history of the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT).4

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), HRBT Expansion Project Corridor Concept

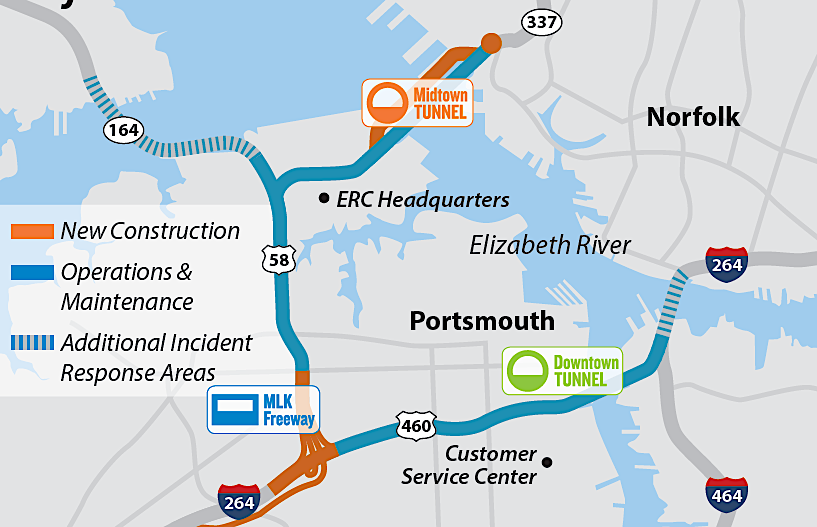

The first two lanes of the Midtown Tunnel opened in 1962. Capacity on Route 58 was doubled in 2016 when a second tunnel was completed, along with extension of the MLK Freeway in Portsmouth from London Boulevard to Interstate 264 and interchange improvements in Norfolk at Brambleton Avenue/Hampton Boulevard.

eastern portal of original Midtown Tunnel, looking west from Norfolk towards Portsmouth Marine Terminal

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Midtown Tunnel from the Norfolk side (2007)

until 2016, Midtown Tunnel traffic squeezed into just one lane in each direction

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Midtown Tunnel, Portsmouth side (2007)

Virginia partnered with Elizabeth River Crossings, a private company, to build a parallel Midtown Tunnel and expand/maintain nearby roads

Source: Elizabeth River Crossings, Elizabeth River Tunnels

To create the new tunnel, 11 concrete tubes were built at Sparrows Point, Maryland. Temporary bulkheads were installed on each side, then the tubes were floated to the Elizabeth River site.

the Elizabeth River tunnel tubes were manufactured at Sparrows Point, then towed to Hampton Roads

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Elizabeth River Tunnels Project (by Tom Saunders)

After placement over the trench excavated in the river bottom, water ballast tanks in each segment were flooded enough to sink the segment into place. Each of the 11 segments was carefully aligned in the trench so they could be sealed into a continuous tube. The ballast tanks were pumped dry, bulkheads were removed, and the tunnel finished.

Source: Elizabeth River Tunnels

The old tunnel is used to carry eastbound traffic from Portsmouth to Norfolk, and the new tunnel was dedicated to westbound traffic. The contractor responsible for the facility, Elizabeth River Crossings, says:5

the oldest two-lane tube of the Downtown Tunnel, built in 1952, is 10 years older than the oldest two-lane tube of the Midtown Tunnel across the Elizabeth River

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Under Gov. Bob McDonnell, the Virginia Department of Transportation used a public-private partnership to obtain private sector funding for expanding the Downtown and Midtown tunnels. The state signed a 58-year contract with Elizabeth River Crossings, a multinational conglomerate formed by Macquarie, an Australian investment banking group, and the Swedish construction firm Skanska. The private company rehabilitates the tunnels, adding cameras, better lighting, and ventilation fans.

The contract guaranteed an average annual profit of 13.5 percent, with annual increases up to 3.5%. The contract with Elizabeth River Crossings was for 58 years, but the tunnels are expected to be in service for another 100-120 years.

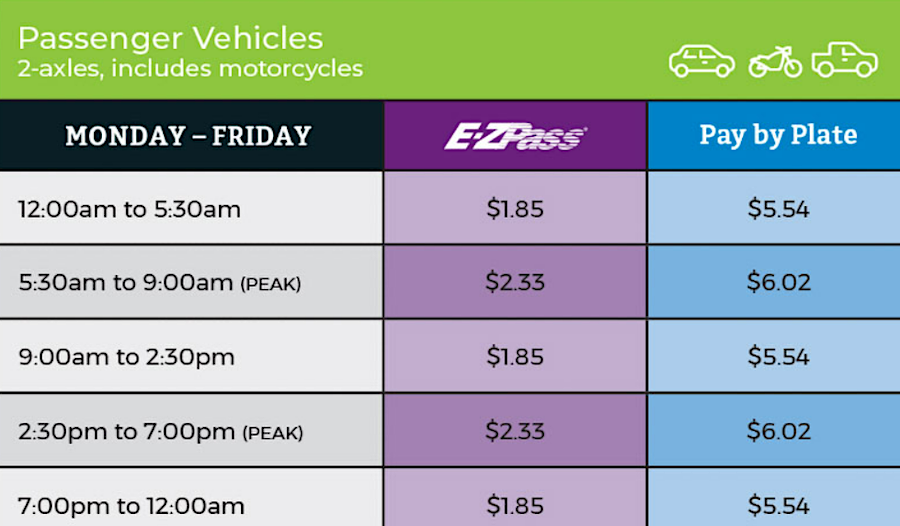

When the local media revealed that Elizabeth River Crossings was adding late fees to unpaid tolls and some commuters owed as much as $14,000, public hostility to the toll company increased. It hired a new Chief Executive Officer who altered how debts were collected and negotiated settlements. The complaints disappeared from news coverage, and the news stories about the 2019 toll increase generated little controversy.

In 2020, the two companies which owned Elizabeth River Crossings sold it to a Spanish firm called Abertis for $2.38 billion. The new owner already operated 5,000 miles of toll roads in 16 countries, but lacked any in the United States.

The private partners in the public-private partnership invested in a project where risk was low, because profits were guaranteed by the Commonwealth of Virginia. Based on the 2020 sale price, they got a compound annual rate of return of almost 20% in return. Governor Terry McAuliffe was clear in his opinion of the contract negotiated by Gov. Bob McDonnell and his Transportation Secretary, Sean Connaughton:6

entrance to the Downtown Tunnel, on the Portsmouth side

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Public pressure led to Elizabeth River Crossings and the Virginia Department of Transportation creating a "toll relief program" in 2016 for low-income Portsmouth and Norfolk residents (in 2021, those making $30,000 per year or less). Residents could apply for the program and receive a 50% toll discount on up to five round-trips a week through the Downtown or Midtown tunnels.

The toll relief program could save low-income residents as much as $650/year in toll payments. All other workers who had to use the tunnels to get to a job across the Elizabeth River had to pay full price for all their commuting trips.7

toll rates on the Midtown and Downtown tunnel added an economic burden on residents who had to commute regularly to jobs on the other side of the Elizabeth River

Source: Elizabeth River Tunnels, Toll Rates

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (technically, the "Lucius J. Kellam, Jr. Bridge-Tunnel" since 1987) is operated by the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission, an agency created by the General Assembly in 1959. The 11-member commission is responsible for planning, funding, constructing, and operating the bridge-tunnel that has carried US 13 between Northampton County and the City of Virginia Beach since 1964.

It eliminated the need for cars and trucks to use ferries to get back and forth from the southern tip of the Eastern Shore. Railroad cars are still transported across the Chesapeake Bay on a specialized ferry.

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission, not the Virginia Department of Transportation, sets tolls, sells bonds, and selects contractors for construction projects. The commissioners are appointed by the governor. The commission's independence reflects the concerns in the 1950's that travelers would not pay enough toll revenue to cover all costs, and the desire of the General Assembly to insulate the state from the financial risk.

The Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel carries I-664 across/under the mouth of the James River. It has connected the cities of Newport News and Suffolk since 1992, and like the James River Bridge offers an alternative route to the often-congested Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel was built as a four-lane structure and has never been expanded, nor has it ever charged a toll.8

the tunnel component of the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel is below the James River shipping channel, close to Newport News

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel

The James River Bridge has carried Route 17 between Newport News and Isle of Wight County since 1928. A bridge, without a tunnel, was acceptable at that location because it is upstream of the Newport News shipbuilding site and the Norfolk facilities used by the US Navy.

the James River Bridge in 1941, 13 years after it was built in 1928

Source: National Archives, Virginia - Newport News

Private entrepreneurs constructed the initial bridge, and tolls were collected between 1928-1975 to repay the initial construction and later maintenance costs. The Commonwealth of Virginia assumed responsibility for the structure during World War II.

looking upstream at the James River Bridge, from Newport News towards Isle of Wight County

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, James River Bridge

It includes a vertical lift span to allow ships up to 145 feet high to get upstream to Richmond and back to the Chesapeake Bay. Traffic must wait for about 15 minutes to raise and lower the lift. In Virginia, only the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel is longer.

The two-lane 1928 structure was replaced with a four-lane bridge in 1982. A section of the original bridge was left on the Newport News side to serve as a fishing pier.9

the James River Bridge can lift a section of the roadway vertically up to 145 feet high

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, The James River Bridge

All the railroad bridges across the Elizabeth River channels are drawbridges. Lifts are left in the "up" position except when a train is nearing the crossing. Highway bridges have constant traffic, so the drawbridges remain "down" except when a boat too high to pass underneath is moving through the channel. To smooth out traffic, some bridges schedule lifts at particular times and require boaters to use those moments to pass through.

Tunnels eliminate the need for interrupting traffic flow for a boat's passage, providing a 24-7 option for driving underneath a waterway. Tunnels also eliminate the operational costs of a drawbridge operator and regular maintenance of metal parts that get sprayed with saltwater on windy days, but the cost of a tunnel is far greater than the cost of a drawbridge.

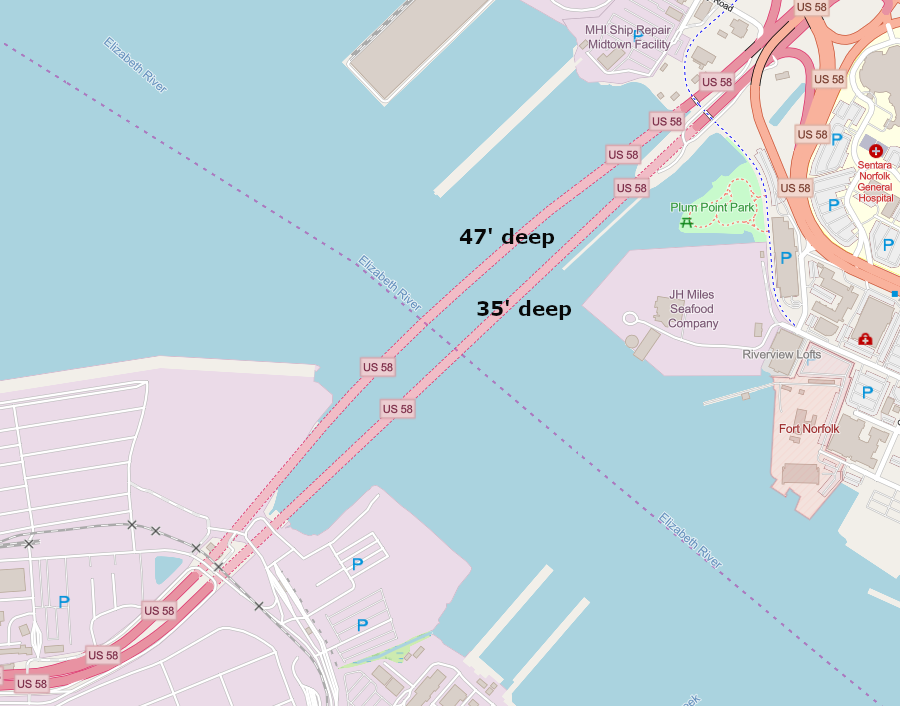

The tunnels of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel allow ships drawing 55' of water to cross, offering the greatest depth for a navigable channel. The Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel tubes provide for a 50' deep navigational channel. The Monitor Merrimac Memorial Bridge Tunnel provides for a 47' deep channel. The Westbound Midtown Tunnel, built in 2016, is deep enough for a 47' channel. The Eastbound Midtown Tunnel, built in 1962, is only deep enough for ships that draw 35' of water. The two Downtown Tunnel tubes, further south on the Elizabeth River, also provide just a 35' deep channel and constrain the size of ships that could reach Norfolk Naval Shipyard.10

the older (1962) section of the Downtown Tunnel permits just a 35' deep navigational channel, while the younger (2016) section would allow dredging a 47' deep channel

Source: ESRI, ArcGIS Online

Replacing drawbridges with taller spans is a solution to minimizing traffic delays on both land and water. The Gilmerton Bridge was replaced with another drawbridge, but with a 35' high span which minimized the need for openings. Much of the traffic on the South Branch of the Elizabeth River going underneath the structure consisted of small boats following the Intracoastal Waterway using the Dismal Swamp Canal or the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal. Larger barges stop at industrial sites on the shorelines south of the bridge.

The bascule bridge, built during the Great Depression, was replaced in 2013 with a vertical lift design. To enable construction of the lift towers straddling the existing bridge, vehicle traffic was stopped each night for months.11

the old bascule Gilmerton Bridge, with construction of the higher vertical lift bridge underway in 2011

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Gilmerton Bridge 2011

the modern Gilmerton Bridge, with vertical lift structure

Source: Kevin Johns, Design and Construction of the Gilmerton Vertical Lift Bridge

Berkley Bridge is a double-leaf bascule bridge across the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, The Berkley Bridge

Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel under construction in 2022

Source: Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel, 65th Anniversary of the HRBT

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, HRBT Expansion Virtual Tour Video

the tunnel component of the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel

a second tunnel was added at Midtown Tunnel in 2016, so bi-directional traffic now occurs only during repairs

Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Midtown Tunnel, Norfolk side (2007)