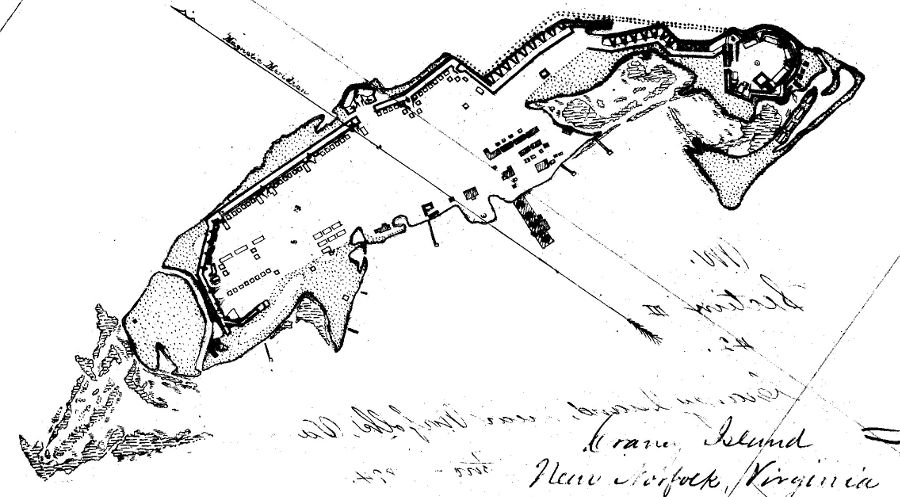

Craney Island

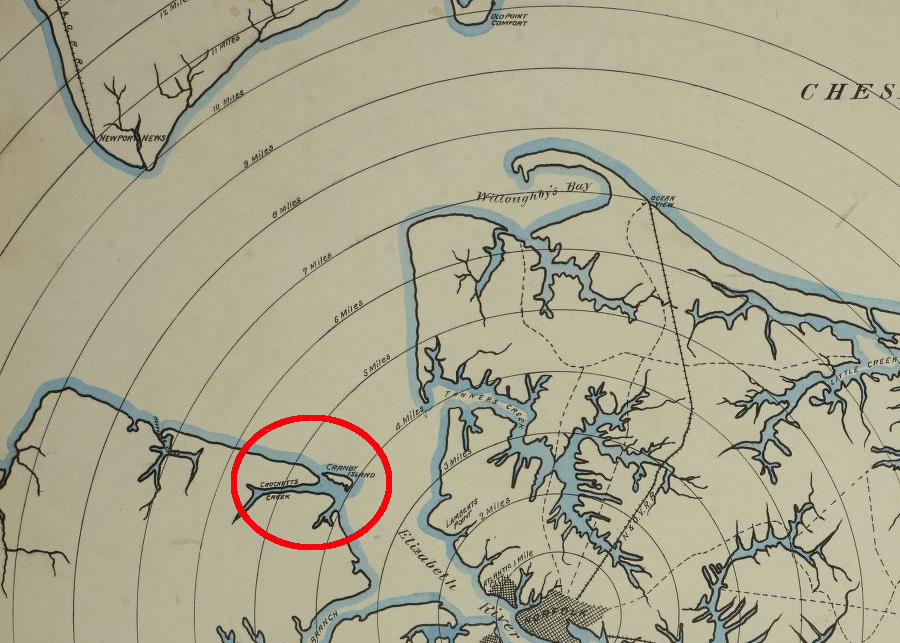

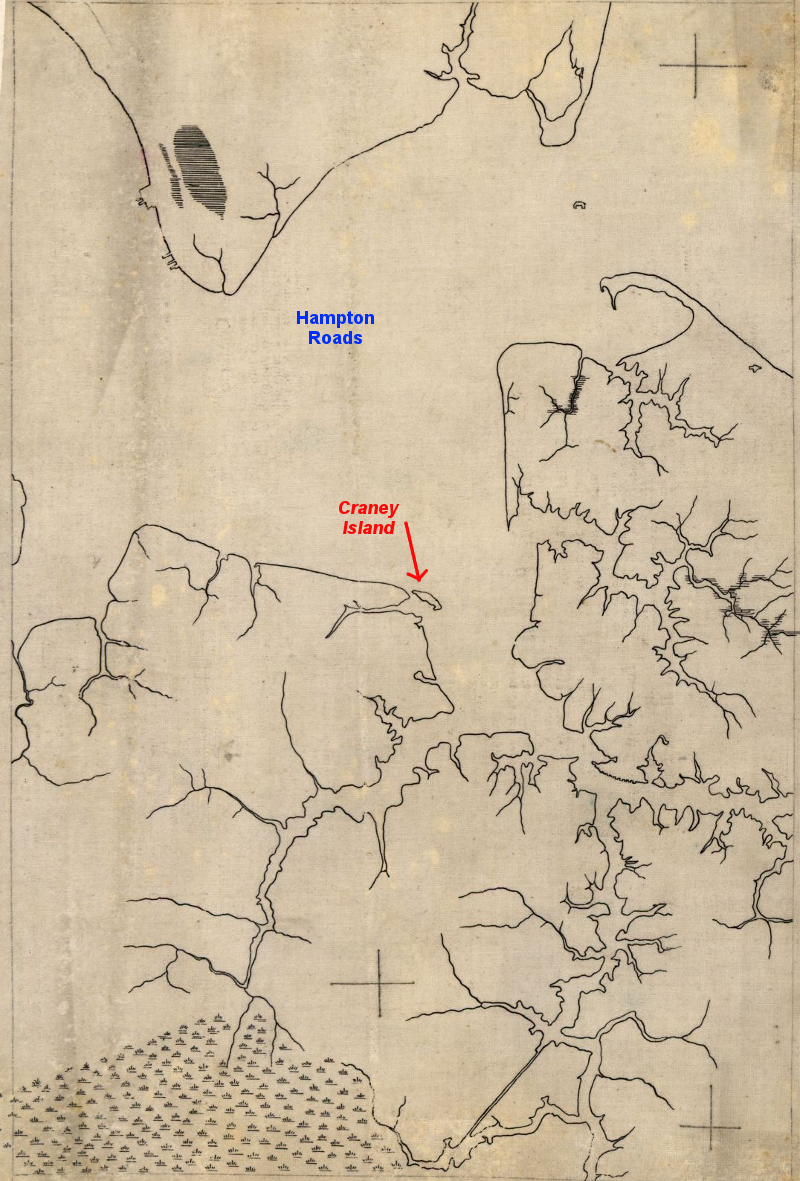

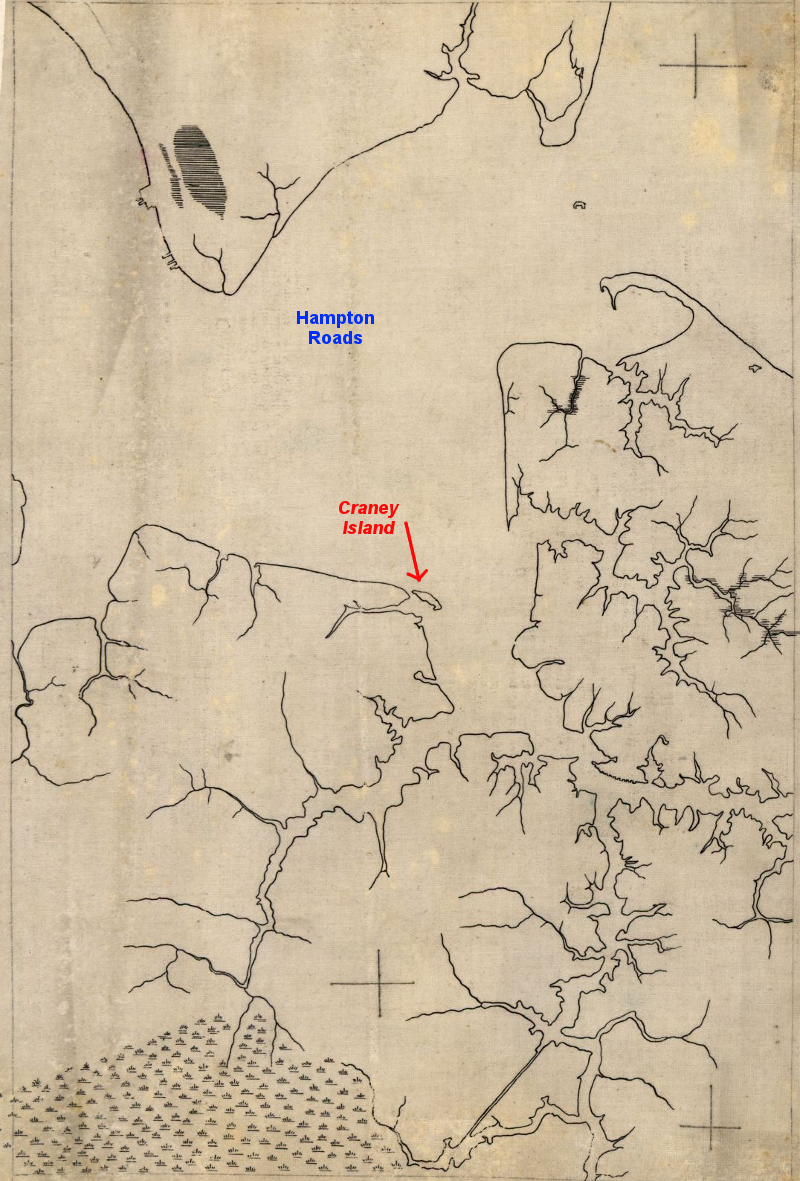

at the time of the Revolutionary War, the stretch of water called the "Thoroughfare" separated Craney Island from the mainland (north is to the right)

Source: Library of Congress, Chart showing the depth of the James and York rivers as they enter Chesapeake Bay, with towns adjacent

Until 1938, Craney Island was an island, with enough herons ("cranes") nesting on it in colonial times to suggest where the island got its name.

Craney Island in the 1780's (NOTE: oriented with north at bottom of image)

Source: Library of Congress, Plan of Princess Ann and Norfolk counties (178_?)

Between the mainland and the island ran the Thoroughfare, a shallow stream that could be crossed on horseback or waded at low tide.

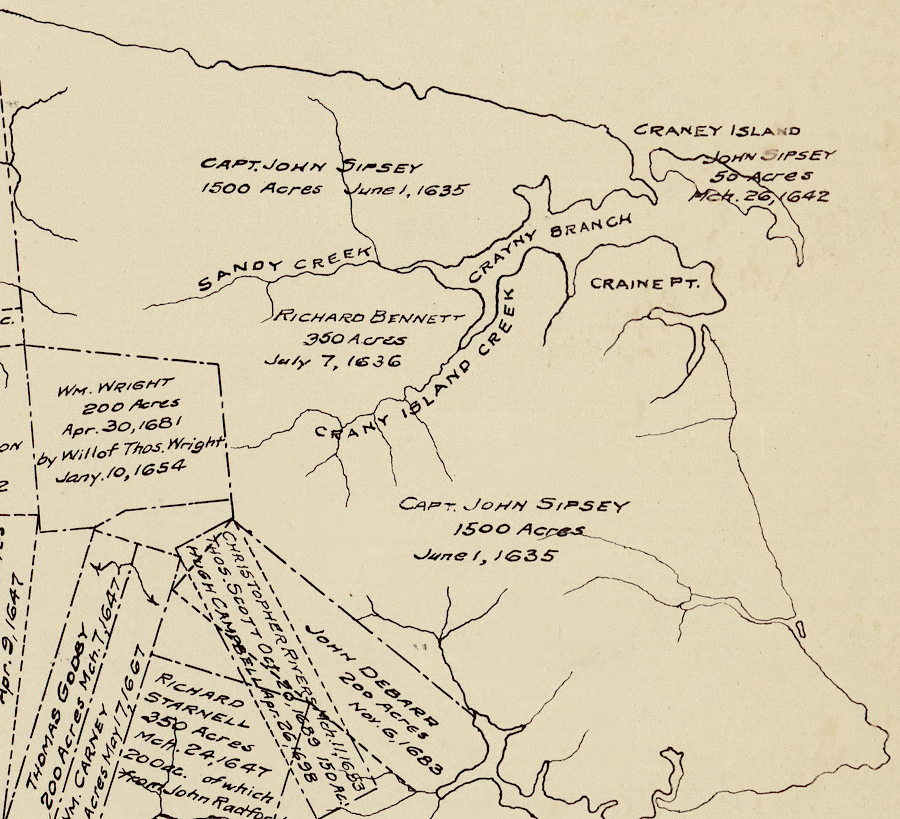

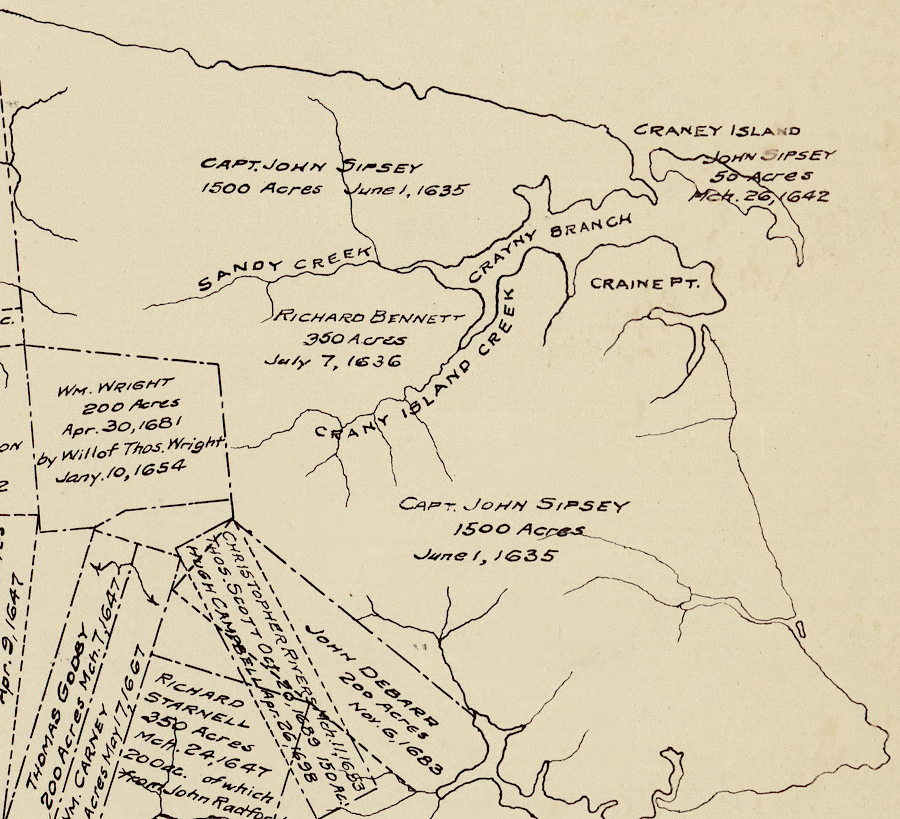

John Sipsey acquired Craney Island by land grant in 1642

Source: Library of Congress, The lower parish of Nansemond County, Va. with adjoining portions of Norfolk County : Elizabeth City Shire 1634, New Norfolk County 1636, Upper Norfolk County 1637, Nansemond County 1642

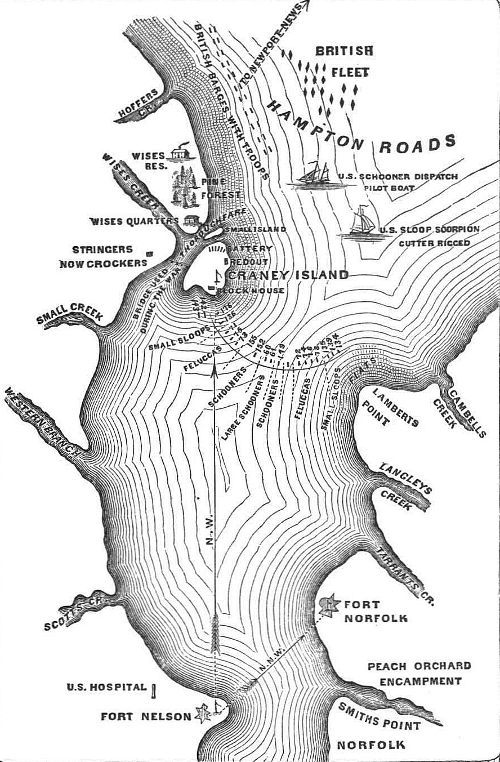

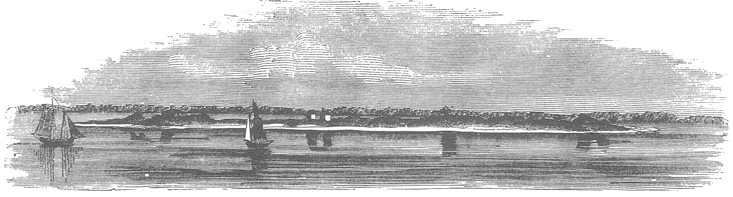

In 1813, Craney Island was:1

- fifty acres of scrub pines, sand, and underbrush tucked behind belts of mudflats and was separated from the shore by two small creeks.

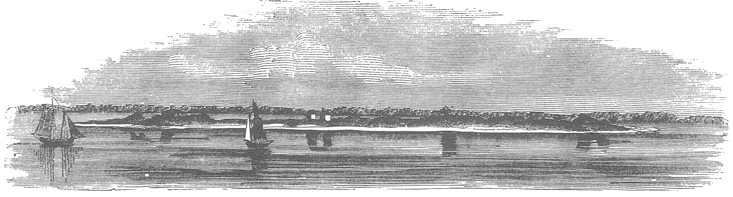

Craney Island was a mudflat and sandbar, stable enough for vegetation to support nesting herons

Source: Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book Of The War Of 1812

Prior to the arrival of English colonists in 1607, Craney Island was occupied by the independent Chesapeake tribe. Powhatan eliminated the leadership of that tribe around 1608 and incorporated it into his paramount chiefdom.

John Smith did not record Craney Island on his map

Source: Library of Congress, Virginia / discovered and discribed by Captayn John Smith, 1606

During the American Revolution, Craney Island was not fortified. In 1779, the British sailed past the island, captured Fort Nelson on the west bank of the Elizabeth River, then seized all the local ships and tobacco in Portsmouth and destroyed the Gosport Shipyard (today's Norfolk Naval Shipyard). In 1780 General Leslie re-occupied Portsmouth, and in 1781 General Benedict Arnold led British forces through the town again.

Craney Island was not connected to the mainland when French engineers mapped the Yorktown area after Cornwallis's surrender in 1781

Source: Library of Congress, Carte de la partie de la Virginie ou l'armee combinee de France & des Etats-Unis de l'Amerique a fait prisonniere l'Armee anglaise commandee par Lord Cornwallis le 19 octobre. 1781

After the American Revolution, the now-independent Americans rebuilt Fort Nelson. They constructed Fort Norfolk opposite Fort Nelson on the east bank of the river, as part of the "First System" of coastal defense forts. During the War of 1812, Craney Island became a key part of the American's defense of the Gosport Navy Yard at Portsmouth.

After the American Revolution, the now-independent Americans rebuilt Fort Nelson. They constructed Fort Norfolk opposite Fort Nelson on the east bank of the river, as part of the "First System" of coastal defense forts. During the War of 1812, Craney Island became a key part of the American's defense of the Gosport Navy Yard at Portsmouth.

A British fleet under Admiral Sir John B. Warren and his subordinate, Admiral Sir George Cockburn, arrived in 1813 to blockade the Chesapeake Bay. They quickly realized there was an opportunity to capture the USS Constellation at the Gosport Navy Yard. The British could also destroy the American navy yard, as the British had done in 1779 during the American Revolution.

To block the British, the Americans anchored the USS Constellation in the Elizabeth River between the Fort Nelson and Fork Norfolk as a floating battery. After discovering the British planned to send fireships up the river to destroy the US frigate, the Americans moved the USS Constellation upstream to the safety of Gosport. A defensive line was planned further downstream on Craney Island to block any British advance up the Elizabeth River.

However, if the British attacked and overwhelmed the defenses on Craney Island, any retreat from the American position there would be very difficult. In a council of war, local militia leaders reconsidered their plan and voted to abandon the island.

In a second council of war, a 30-year old Army engineer named Walker K. Armistead voiced his objections. He had been planning how to fortify the island since 1809. The militia leaders, encouraged by naval leaders plus Armistead's report of how just 300 men could block the British from seizing the American fortifications, reversed their previous decision. Had Craney Island been abandoned, the British would probably been able to occupy Norfolk and Portsmouth, capture the USS Constellation, and destroy the Gosport Navy Yard.

After re-committing to a defense at Craney Island, guns and personnel from the USS Constellation were moved to the island. They could help repel a British assault there. If not moved, the guns and personnel would have been isolated in Gosport - far from where the ship's fate would be decided.2

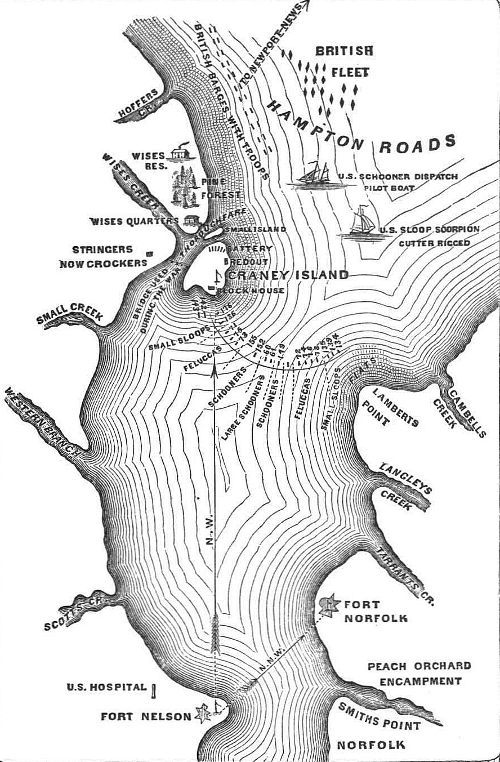

The British planned to sail up the Elizabeth River. They managed to get a local pilot to identify the shallow, twisting channel, and realized that their fleet would be exposed to American fire unless the British controlled the shoreline.

Because the Americans had fortified Craney Island with cannon and troops, seizure of the Gosport shipyard required capturing Craney Island first.3

Sir Thomas Sydney Beckwith was in charge of the British army troops carried by the navy vessels, including French soldiers who had been captured or deserted from Napoleon's army in Europe and were fighting as Independent Companies of Foreigners.

On June 22, 1813 Beckwith sent troops to land west of Craney Island near Hoffler's Creek. The soldiers marched to the Thoroughfare, the channel which separated Craney Island from the mainland, but arrived when tide was too high to wade across. The American artillery shelled the soldiers waiting on the other side of the Thoroughfare for the tide to change, forcing the British army to retreat.

At the same time, an amphibious assault via barges on the eastern side of Cranel Island was blocked by the Americans. The British attacked at ebb tide, and in the shallow water mudflats blocked the barges from reaching the shoreline. The American guns were effective in blasting the barges. The British were unable to return fire effectively, and withdrew from the eastern front as well.

The American defense at Craney Island saved the USS Constellation and the shipyard. The USS Constellation was forced to stay in the Elizabeth River, but was not captured or burned.4

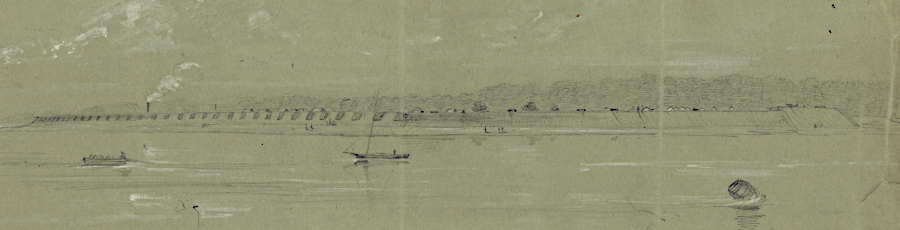

Craney Island in 1813, when the Thoroughfare separated the island from the mainland

Source: Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book Of The War Of 1812

American guns on Craney Island blocked an attempted amphibious landing by the British in 1813

Source: Library of Virginia, Plan of operations at Craney Island, 1813 June 22 (by George Francis de La Roche, 1813)

Though the British assault was blocked at Craney Island, three days later the town of Hampton on the other side of the James River was seized. The French who had been enlisted into the Independent Companies of Foreigners to fight for the British demonstrated what undisciplined troops can do to defenseless civilians.5

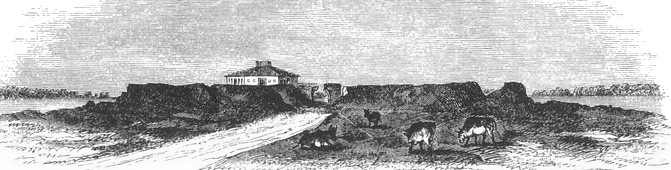

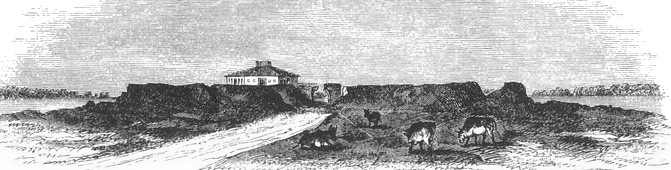

fortifications on Craney Island were allowed to erode after the War of 1812 ended

Source: Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book Of The War Of 1812

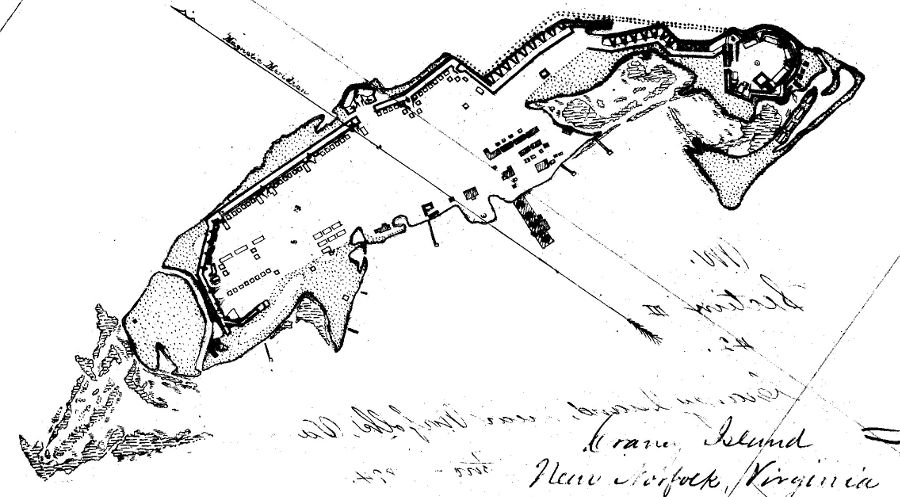

During the Civil War, Craney Island was fortified again by the Confederates.

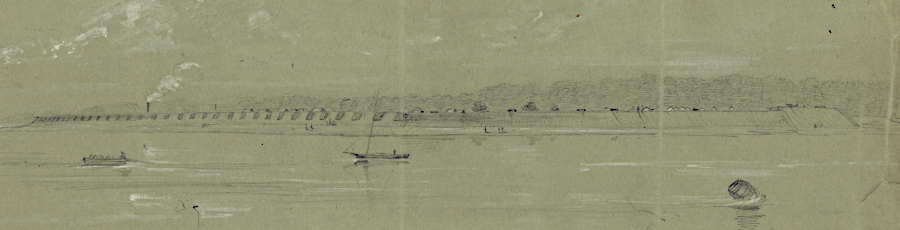

Confederate batteries fortified Craney Island in 1861

Source: Library of Congress, Cranes Island (by Alfred R. Waud, 1861-65)

After the US Navy evacuated the navy yard at Gosport, Confederates occupied it. They raised the burned hull of the USS Merrimack and converted it into the Confederacy's ironclad warship, the CSS Virginia.

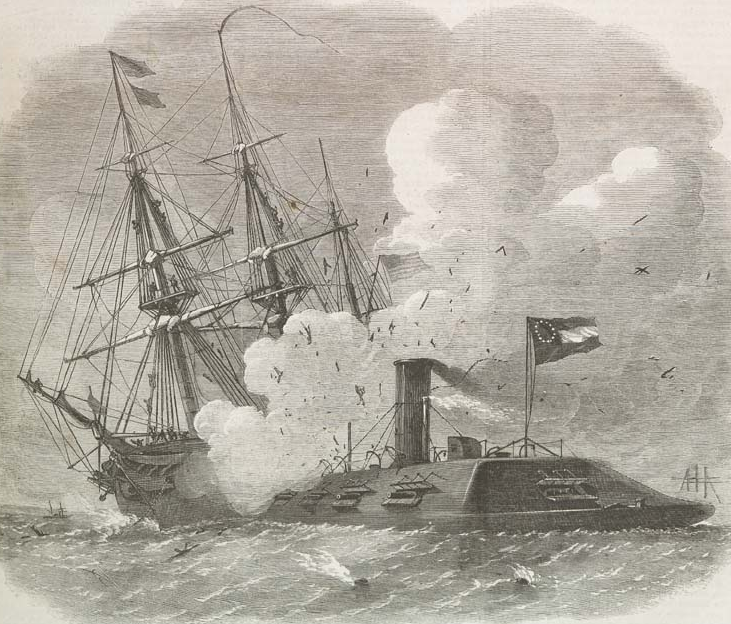

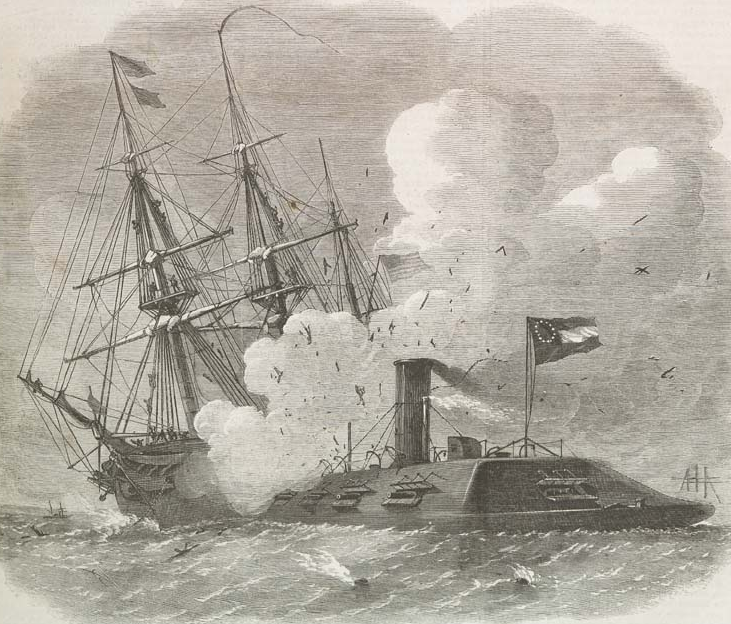

before the USS Monitor arrived, the CSS Virginia was able to destroy wooden warships that could not sail away fast enough

Source: Illustrated London News, The Civil War in America: Fight in Hampton Roads between the Federal floating-battery Monitor and the Confederate Iron-Plated Steamer Merrimac (or Virginia) Running into the Federal Sloop Cumberland (April 5, 1862)

On March 9, 1862, early in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign to capture Richmond, the CSS Virginia crew had "two jiggers of whiskey and a hearty breakfast" before fighting the USS Monitor. The CSS Virginia was not the first Confederate ironclad, but the "battle of the ironclads" made it the most-remembered in history.

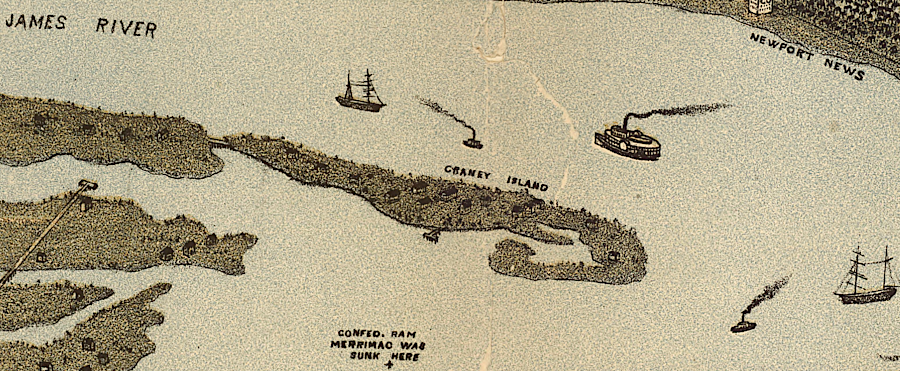

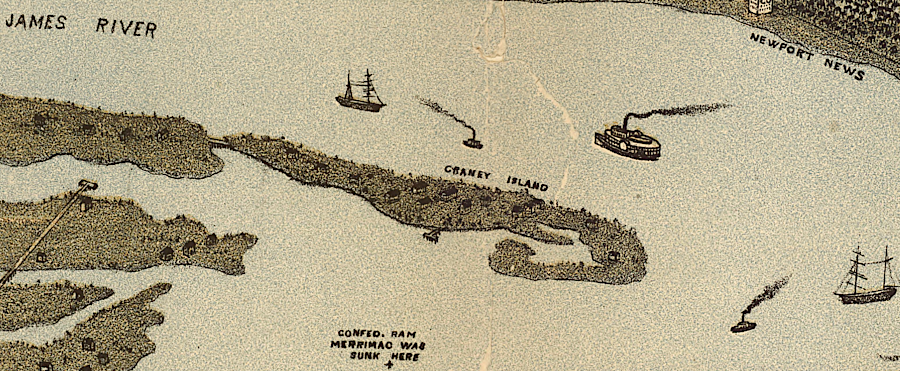

the Battle of the Ironclads occurred just north of Craney Island in 1862

Source: National Archives, Sheet No. 1 Military Reconnaissance (by Col. T. J. Cram)

After the two ironclads fought to a draw, the CSS Virginia steamed past Craney Island and returned back up the Elizabeth River. It remained trapped in Portsmouth by the Union fleet - just as the USS Constellation had been trapped by the British fleet in 1813-14.6

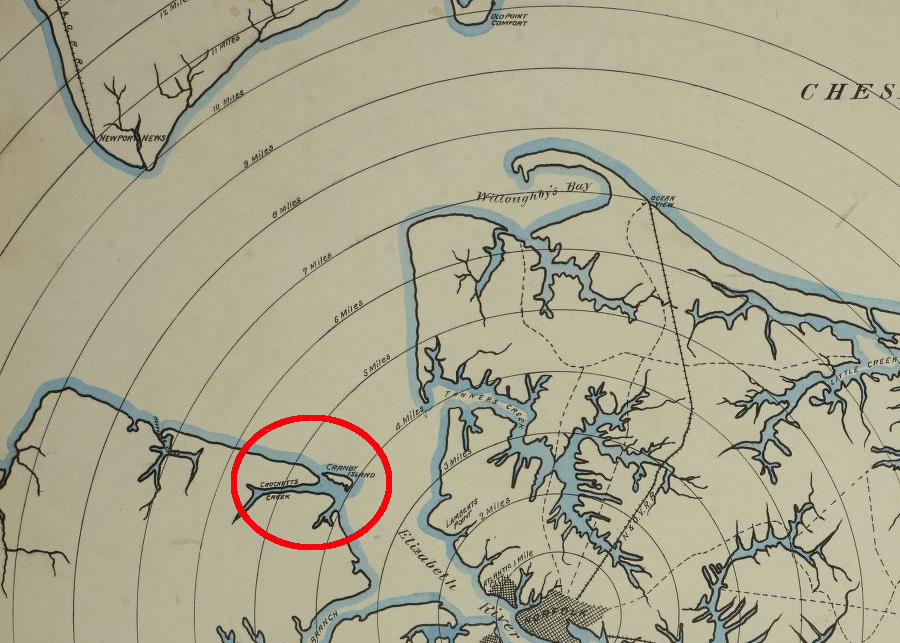

Craney Island (No. 8, in red circle) was fortified by Confederates while Fort Wool (No.5) remained occupied by Union forces

Source: Library of Congress, Fortress Monroe, Va. and its vicinity (by Jacob Wells, c.1862)

To capture Norfolk in 1862, Union troops landed 6,000 troops at Ocean View. In response, the Confederates abandoned Norfolk and Portsmouth, and burned the Gosport Navy Yard.

Craney Island was an island, separate from the mainland, in 1861

Source: Library of Congress, The key to East Virginia showing the exact relative positions of Fortress Monroe, Rip Raps, Newport News, Sewalls [sic] Point, Norfolk, Gosport Navy Yard and expressing the soundings of every part of Hampton Roads & Elizabeth River

The CSS Virginia planned to break through the Union fleet at Newport News and escape up the James River towards Richmond, but the water depth was too shallow for the ironclad. On May 11, 1862, Confederate captain Josiah Tattnall (who had been involved in the 1813 battle of Craney Island) ordered the CSS Virginia to be run aground near Craney Island. The crew rowed safely to the island while the warship was intentionally destroyed:7

- She had been burning fiercely for an hour and a half, when a terrific explosion tore her to pieces. The air was thick with large and small pieces of timber. Huge sections of red hot iron plate were torn off and whirled through the air so much like paper.

destruction of the CSS Virginia at Craney Island in 1862

Source: Library of Congress, Destruction of the rebel monster "Merrimac" off Craney Island May 11th 1862 (Currier & Ives print)

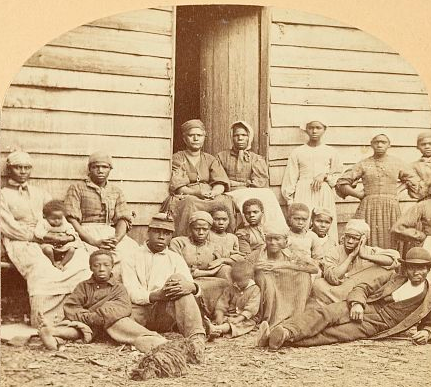

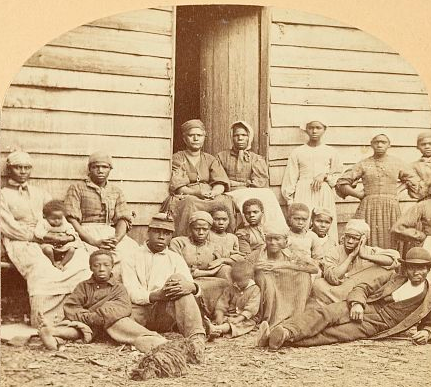

At the start of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln made clear that the primary war aim was to maintain the union, not to end slavery. When three escaped slaves arrived at Fort Monroe and sought protection, General Benjamin Butler refused to return them to a Virginia slave owner. Under Lincoln's policy, Butler could not declare the escaped slaves to be free, but he was unwilling to return them under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Instead, Butler categorized the men as "contraband of war," after which hundreds more then arrived at Fort Monroe. Hampton became a nucleus for contrabands, where they lived in small huts, were employed as military laborers, and survived off food from the military and donations from Northern sympathizers.

Butler's replacement, General John A. Dix, tried to move contrabands away from the fort and put them to work on plantations abandoned by Confederate owners. By the start of 1863, over 1,600 freed slaves were living in a refugee camp on Craney Island. The island was small (contemporary accounts describe it as having shrunk by half to 20 acres in size), and the camp was closed in September, 1863.8

between slavery and freedom - contrabands in Virginia

Source: Library of Congress, A group of "contrabands" (1862)

Craney Island was then occupied by the 10th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry. That regiment was raised in Hampton Roads after the Union decided to recruit and arm black soldiers. The 10th Regiment camped on Craney Island only briefly, until moving to the Eastern Shore in January, 1864.9

Craney Island was fortified by the Confederates in 1862

Source: NOAA Office of Coast Survey, Map of Craney Island, Near Norfolk, VA, from the Survey of 1862

Craney Island in 1887

Source: Library of Congress, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Norfolk, Independent Cities, Virginia (Sanborn Map Company, 1887)

Craney Island in 1891

Source: Library of Congress, Bird's eye view of Norfolk, Portsmouth and Berkley, Norfolk Co., Va (1891?)

The challenge of shipping troops to France during World War I overwhelmed the Navy's existing shipyards. In 1918, the War Shipping Board built an oil tank farm on Craney Island, and twenty 50,000 gallon tanks were filled with oil brought by railroad. (The oil arrives now via Colonial Pipeline.)10

In 1919, the War Department traded Craney Island to the Public Health Service (then part of the Treasury Department) for use as a quarantine site. The US Naval Hospital in Portsmouth, first built in 1827 on the former site of Fort Nelson south of the island, already served the sailors and workers at the Norfolk Navy Shipyard.

In exchange for Craney Island, the Treasury Department gave Fisherman's Island to the War Department, which had already fortified that island to control access to the Chesapeake Bay.11

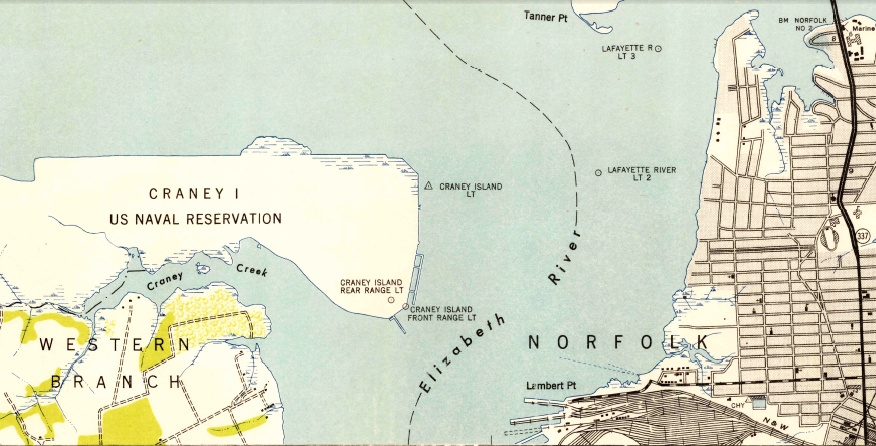

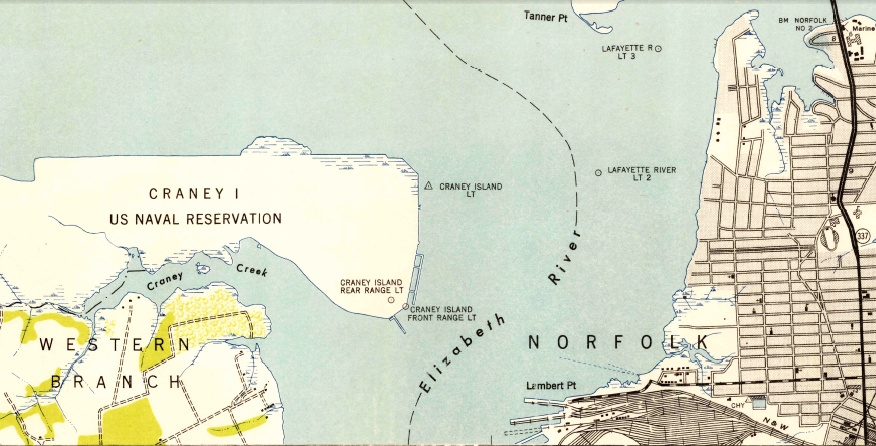

In 1938, the Thoroughfare was filled in and Craney Island lost its status as an island.

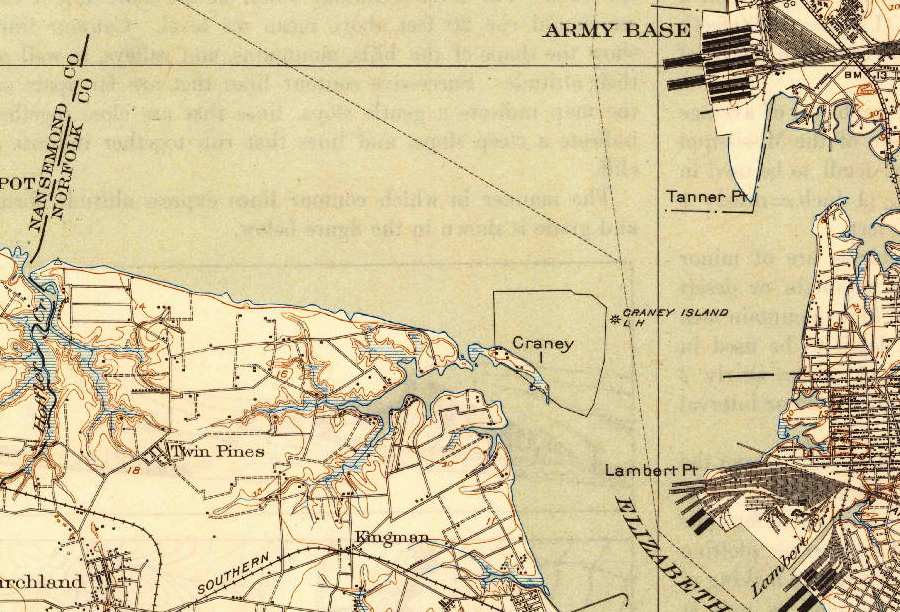

in 1948, the Thoroughfare had been filled in and Craney Island was no longer an island, but deposition of dredge spoils to the north was just starting

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk North 7.5x7.5 topographic quad (1948)

In 1942, the 18' deep channel in the Elizabeth River was dredged to 42' deep to improve access to the fuel depot built. That channel probably destroyed any substantial remains of the CSS Virginia that might have survived previous salvage efforts and souvenir collecting, but some small historic fragments may still lie underwater near the Craney Island Fuel Terminal piers.12

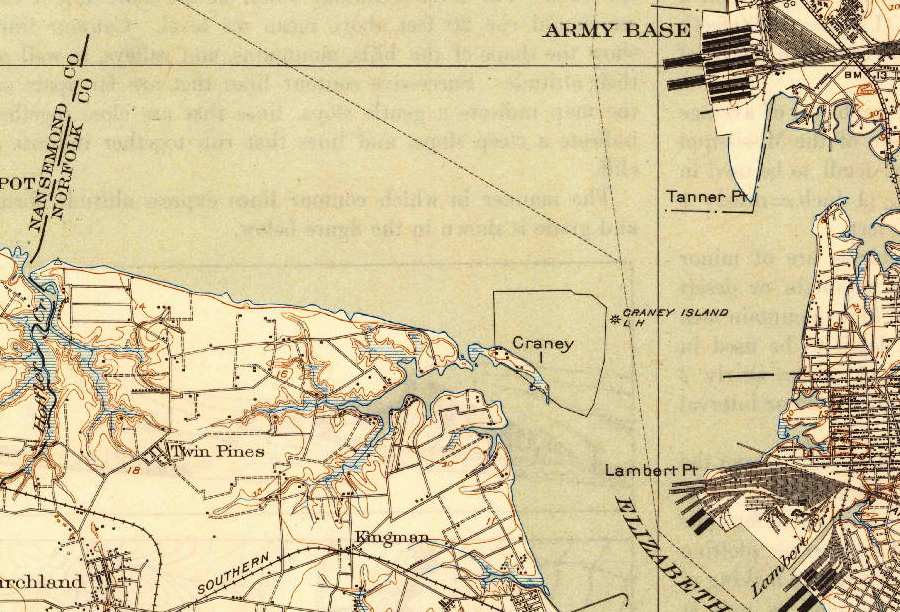

by 1941, Craney Island was identified as the dumping site for dredge spoils created by deepening the Elizabeth River channel

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Newport News 1:62,500 topographic quadrangle (1941)

Since the 1950's, Craney Island has been expanded far to the north and west in order to serve as a dredge spoil site. The Craney Island Dredged Material Management Area is now being expanded to the east, and a new terminal to handle containerized cargo is planned for that location.

dredging the shipping channels - and disposing of the muck - is essential to maintaining the Port of Virginia and private terminals along the Elizabeth and James rivers

Source: Virginia Maritime Association, Full Potential

In the meantime, Craney Island serves as a graveyard for whales. In 2014 a 45-foot long sei whale died in the Elizabeth River, perhaps because it had swallowed a 3x5 inch piece of plastic that blocked digestion and perhaps because the whale had been struck by a ship. After towing the carcass to Craney Island and completing a necropsy on the beach, personnel from the Virginia Marine Resources Commission and Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center dug a hole for the remains close to where a fin whale had been buried in 2007.13

Craney Island, on the west side of the Elizabeth River in Hampton Roads, has been dramatically transformed since this 1902 map

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS), Norfolk 30x30 Grid topographic map (1902)

Craney Island in 1892, before conversion to dredge spoil site

Source: Library of Congress, Panorama of Norfolk and surroundings 1892

Links

- American Naval Records Society - The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History

- Hampton Roads Naval Museum

- National History Education Clearinghouse

French engineers who came to Yorktown in 1781 noted that Craney Island was separated from the mainland

Source: Library of Congress, Campagne en Virginie du Major General M'is de LaFayette : ou se trouvent les camps et marches, ainsy que ceux du Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis en 1781

References

1. Bruce Linder, Tidewater's Navy: An Illustrated History, Naval Institute Press, 2005, p.41, http://books.google.com/books?id=awYJ7aSWNWsC; Benson J. Lossing, "Predatory Warfare Of The British On The Coast," Pictorial Field-Book Of The War Of 1812, pp.675-678, https://archive.org/details/fieldbookswar181200lossrich (last checked March 22, 2014)

2. "The Decision at Craney Island," American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/decision-craney-island; "Craney Island Battle Led To Burning Of Hampton," The Virginian-Pilot, October 1, 1995, https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1995/vp951001/09290198.htm (last checked May 23, 2022)

3. William S. Dudley (ed.), "Rear Admiral George Cockburn, R.N., to Admiral Sir John B. Warren, R.N.." March 23, 1813, in The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, American Naval Records Society, pp.326-327, http://www.ibiblio.org/anrs/docs/E/E3/dh_1812_v02.pdf; William Maxwell, The Virginia Historical Register and Literary Advertiser, Vol. I, No. III (July 1848), p.132, https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=xkUUAAAAYAAJ (last checked March 25, 2014)

4. Bruce Linder, Tidewater's Navy: An Illustrated History, p.85; "Craney Island Battle Led To Burning Of Hampton," The Virginian-Pilot, October 1, 1995, https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/VA-news/VA-Pilot/issues/1995/vp951001/09290198.htm; "The Decision at Craney Island," American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/decision-craney-island (last checked May 23, 2022)

5. Parke Rouse, Jr., "The British Invasion of Hampton in 1813: The Reminiscences of James Jarvis," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 76, No. 3 (July, 1968),p.319, pp.330-331, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247407 (last checked March 26 2014)

6. "Roots," Norfolk Naval Shipyard, US Navy, http://www.navsea.navy.mil/shipyards/norfolk/History/Roots.aspx; "The Attack on the Federal Fleet," The National Republican (Washington, D.C.), October 22, 1861, Page 2, in "Chronicling America," Library of Congress, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014760/1861-10-22/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1861 (last checked March 15, 2015)

7. "Merrimack (U.S.S.)," National Underwater and Marine Agency, September 1982, http://www.numa.net/expeditions/merrimack-u-s-s/ (last checked March 22, 2014)

8. "The Contrabands at Craney Island--Their Labors, Their Hopes and Prospects--Deaths, &c.." The New York Times, February 16, 1863, http://www.nytimes.com/1863/02/16/news/fortress-monroe-contrabands-craney-island-their-labors-their-hopes-prospects.html; Gary W. Gallagher, The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula and the Seven Days, UNC Press Books, 2000, p.140, http://books.google.com/books?id=5neZUIQoDWEC; "Lucy Chase to Major General John A. Dix, Commanding Department of Virginia, Craney Island, VA," January 19, 1863, posted online in Through a Glass Darkly: Images of Race, Region, and Reform, An American Antiquarian Society Online Exhibition, http://faculty.assumption.edu/aas/Manuscripts/Chase/01-19-1863.html; (last checked March 26, 2014)

9. "10th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry," National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-regiments-detail.htm?regiment_id=UUS0010RI00C (last checked March 26, 2014)

10. "Finally, 1813 battle gets some respect," The Virginian-Pilot, June 24, 2008, http://hamptonroads.com/2008/06/finally-1813-battle-gets-some-respect (last checked March 24, 2014)

11. "An Act Transferring the tract of land known as Craney Island from the jurisdiction of the War Department to the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department and transferring the tract of land known as Fishermans Island from the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department to the jurisdiction of the War Department," US Congress, P.L. 66-87 (41 Stat. 358), November 19, 1919, https://maint.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/66th-congress/session-1/c66s1ch114.pdf (last checked February 10, 2025)

12. "Maintenance of Chesapeake Bay Entrance Channels and use of sand borrow areas for beach nourishment," National Marine Fisheries Service Endangered Species Act Biological Opinion, October 16, 2012, pp.8-9, http://www.nero.noaa.gov/prot_res/section7/ACOE-signedBOs/BioPChesapeake%20Bay101612.pdf (last checked March 22, 2014)

13. "Dead whale likely struck by ship, necropsy shows," The Virginian-Pilot, August 23, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/node/726413; "How do you haul a whale carcass? Make it a balloon," The Virginian-Pilot, August 22, 2014, http://hamptonroads.com/node/726278 (last checked August 23, 2014)

Craney Island soon after the American Revolution

Source: Library of Congress, Part of the Province of Virginia (1791?)

Craney Island in 1861, before dumping of dredge spoil converted the island into a rectangular peninsula attached to the west bank of the Elizabeth River

Source: Library of Congress, Outline map of Hampton Roads, and the vicinity of Norfolk, Va.

From Feet to Space: Transportation in Virginia

Virginia Places